Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

HTS Theological Studies

versão On-line ISSN 2072-8050

versão impressa ISSN 0259-9422

Herv. teol. stud. vol.70 no.1 Pretoria Jan. 2014

ORIGINAL RESEARCH: FOUNDATION SUBJECTS - OLD AND NEW TESTAMENT STUDIES

Early Christian spiritualties of sin and forgiveness according to 1 John

Dirk G. van der Merwe

Department of Christian Spirituality, Church History Missiology, University of South Africa, South Africa

ABSTRACT

The article attempts to investigate the possible lived experiences created by this text. The text revolves around the experience of fellowship with God (1:6, 7) who is characterised as 'light'. For the author of 1 John, sin disrupts this fellowship. He creates an awareness and a 'spirituality of sin and guilt' in the lives of his readers through the use of the experiential metaphor of darkness in a dialectic combination with light and the two false negations 'do not have sin' (sin as a noun) and 'do not sin' (sin as a verb). This fellowship is re-established through living in the light: the confession, forgiveness and expiation of sin. The author creates a spirituality of confession, forgiveness and expiation of sin through descriptive cultic (blood of Jesus and expiation), forensic (paraclete), atypical (cleans, expiation, paraclete) and all-inclusive (all [twice], whole, anyone) language. Thus, in his rhetoric, the author uses metaphor, dialectic, sacrificial, forensic, atypical and all-inclusive language to facilitate a variety of 'lived experiences' within his readers. Firstly, he wants them to feel guilty about their sins and consequently, after they have confessed their sins, to strengthen their faith. Secondly, he wants to encourage them to believe that they can experience the forgiveness of their sins and, by doing so, know that they have eternal life (5:13) and can experience fellowship with God and, mutually, with one another.

Introduction

In the article, 'The importance of language in emancipatory theology' (Spirituality and Christianity n.d.), the author refers to the work of Ludwig Wittgenstein (1889-1951) and is convinced that Wittgenstein still continues to be relevant to challenge contemporary theology. The strongest weapon used by Wittgenstein is his sense of language. Probably influenced by his personal 'evangelical conversion experience', he struggled to comprehend and 'explain the Christianity that is lived more than talked'. This unknown author also points out that, in their response to this passion of Wittgenstein, many scholars are positively convinced that 'there is a reality-constructing nature in language' that should be applied to contemporary life practices and experiences. In his praxis, Wittgenstein finds particular ways in which to use language as a resource through which theological meaning can be powerfully conveyed to humans to influence behaviour and culture.1

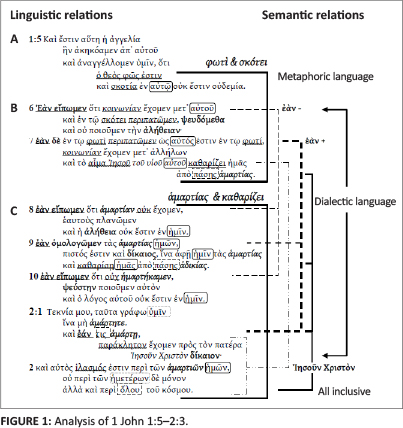

When I read the Greek text of 1 John 1:5-2:2, it is evident that this text conforms to the 'reality-constructing nature in language'. The author of 1 John (hereafter referred to as 'the Elder') tries to construct, through his well-planned writing, specific realities to bring into existence certain 'human behaviour'. He tries to create realities and 'lived experiences' with his wordplay and rhetoric in verses 1:5-2:2.2 He uses words and phrases (repetition, metaphors, dialectic language and words indicating specific events in the life of Jesus) to recall old realities and to constitute new lived realities.

The purpose of this article is to investigate how the Elder uses repetition, metaphoric language, dialectic language, forensic and cultic language, atypical language and all-inclusive language3 to generate lived experiences amongst his readers in order to convince them that sin distorts fellowship with God and that continuous forgiveness is required to restore or to experience any form of fellowship between God and his children.4

A 'lived experience' of having fellowship with God

Any investigation concerning the spiritualities of sin and forgiveness necessitates, firstly, to contextualise these activities and consequent lived experiences. Such a context is created by the Elder in his reference to the being and nature of God in verses 1:5-7.

Metaphoric and dialectic language

For the Elder, God is a mysterium tremendum (cf. Otto [1923] 1975:12), an object beyond the conception and comprehension of humans.5 This is because human knowledge has certain limits and because, in this mysterious object, God, he comes upon something 'wholly other'. His being and nature are incommensurable with that of human beings (cf. Otto [1923] 1975:28). Therefore, in 1 John 1:5b-7, the Elder identifies God in terms of metaphor and his relationship with human beings. He uses two complimentary antithetical parallelisms to create a specific radical contrast that is known to his readers.6 With the first use in 1:5b, he identifies God's being7 and nature8: 'God is light and in him there is no darkness at all' (ό θεός φως έστιν και σκοτία έν αύτω ούκ εστίν ουδεµία). In the second use, he explains that fellowship with this God can only be obtained when living in the light (έν τω φωτι περιπατωµεν) and not when you are in darkness (έν τω σκότει περιπατωµεν). These antithetical metaphors help the readers to position themselves with regard to their relationship and fellowship with God.

According to Cupitt (1998:71), we must bear in mind that '[ t]he mind transcends language, religious experience goes beyond language ... in order to try, at least, to make it say what cannot be said'. He (Cupitt 1998:74) is also of opinion that '[l]anguage determines experience as such. Language "forms" certain events, and thereby makes them into conscious experiences.'

An identification of the divine (1:5)

The Elder starts to introduce his theological discussion with reference to the being and nature of God: 'God is light and in him there is no darkness at all.'9 In order to get to the meaning and to understand this double metaphoric expression about God in verse 1:5, cognisance has to be taken of what Grabe says about metaphors. She (Grabe 1992:288) points out that, normally, uniform explanations are given to lexicalised expressions. However, first impressions are important, and generally known associations should be given preference. Also the context is of major importance in this regard.10

When considering these aspects (first impressions, generally known associations and linguistic context), the following three things11 become evident from the linguistic context with regard to God's being and nature. Firstly, the positive declaration, 'God is light'12 in the protasis of the second part of the verse, is a metaphorical statement of God's being and nature which has serious implications for God's relationship with 'his children' (cf. Johnson 1993:28; also Bultmann 1973:16; Strecker 1996:25).13 It can be deduced that this metaphor reflects God's enlightenment (the physical connotation of light) (Hiebert 1988:331; cf. also Krimmer 1989:26), his truth (αλήθεια, 1:6, 8)14 and his holiness (the moral, περιπατεΐν in 1:6, 7).15

The Elder reinforces the concept of the preceding, positively stated clause, 'God is light', by adding a negative statement, 'in him there is no darkness at all' (σκοτία έν αύτφ ούκ εστιν ουδεµία.) in the apodosis part of 1:5b, opposite the preceding clause. This clause serves to emphasise that the statement, God is light,16 is absolute, without any exception. In the Greek text, a double negative (ούκ ... ουδεµία) is used, which reinforces the negation. Its function is to express an emphatic negation (Haas et al. 1994:32). The noun 'darkness', when it is heard or read, immediately creates a negative image in the mind.17 For the Elder then, darkness (σκοτία) is not merely the absence of physical light. Metaphorically it has a moral quality reflecting the absence of salvation and of God, standing in direct antithesis to all that characterises God as light (φως). For him, light and darkness represent two separate and distinct realms in opposition and contrast to each other (cf. Hiebert 1988:331f.; Painter 2002:139).

The statement 'God is light' (1:5) thus carries with it an inevitable moral challenge as spelled out in 1:6-2:17 (Bruce 1970:41; Haas et al. 1994:32): his children must walk (περιπατεΐν) in the light due to his nature, and they 'ought to walk (περιπατεΐν) just as he [Jesus] walked (περιπατεΐν)', 2:6 (see Thomas 2004:75). Thus, to live in the light keeps the children of God in the familia Dei, in fellowship with the Father, his Son, the Spirit and fellow brothers (4:13-21).18 In contrast, this characterisation of God prepares the reader for the discussion about sin and forgiveness that will follow. Those who live in darkness, in sin, cannot have fellowship with God, for 'in him there is no darkness at all'.

Sin hampers fellowship with the divine

This fellowship (κοινωνίαν) is referred to in verses 1:6-719 and comprises to live (περιπατωµεν) in the divine life and experience it.20 In this new pericope, the Elder tries to explain how this fellowship can be hampered or established, and how it can be sustained.21

In his message (αγγελία) that 'God is light',22 the Elder provides a basis for an ethical application.23 If 'God is light', those who truly know God will 'walk in the light' (1:7; cf. also 2:6). Having said that 'God is light' and using a strong double negative (ούκ ... ούδεµία), the Elder prepares the reader for what is coming and for what it entails to live in the light.

This he does when he refers to the three claims made by the schismatics (1:6, 8, 10) and his own counterhypotheses to these claims in 1:6-2:2 (Kruse 2000:62). For the Elder, sin is the main constraint to fellowship. In this pericope, the Elder focuses on this problem. In the following pericope24 and the rest of the epistle, he spells out more positively what 'living in the light' comprises. This light and darkness create opposite 'lived experiences'. A lived experience of the divine 'as Light'25 is important for the Elder - this will urge his adherents not to lose faith (cf. Filson 1969:276) but to strengthen their faith (5:13).

Before he comes to the point where he discusses what it means to live in the light and how this can be realised, he emphasises how the main obstacle, which is sin,26 should be dealt with, although this will also bring about its own negative lived experiences. The Elder's emphasis on sin was probably caused by the schismatics who claimed a special illumination by the Spirit (2:20, 27) that imparted to them the true knowledge of God. This caused them to regard themselves to be the children of God (cf. Hurtado 2003:424).

Through this spiritual illumination, these schismatics claimed to have attained a state beyond ordinary Christian morality in which they had no more sin and attained moral perfection (1:8-10) (Hurtado 2003:416; Painter 2002:227; Van der Merwe 2005:441f.). This group thought that all believers had been delivered from sin and had already crossed from death into life (1 Jn 1:8, 10; 3:14). This strong emphasis on realised eschatology led to a disregard for the need to continue to resist sin. Their chief ethical error appears to be a spiritual pride that led them to despise ordinary Christians who did not claim to have attained the same level of spiritual illumination. The Elder warns his readers against claiming to be without sin (1 Jn 1:8-22) (Van der Merwe 2012:692; cf.Hurtado 2003:424).

A 'lived experience' of sin (1:8-10) and forgiveness (1:7, 2:1-2)

A lived experience of sin (1:6, 8, 10)27

The high frequency of references to sin in this pericope signals that fellowship (κοινωνία) with God stands or falls with the presence or absence of sin. In three conditional sentences (1:6, 8, 10), the Elder does not define sin28 but organises it around three assertions, each beginning with the conditional phrase έάν εϊπωµεν [if we say]. It is reasonable to assume that some members in the community were making these assertions (Culpepper 1998:257; Hiebert 1988:332; Hurtado 2003:414; Van der Merwe 2007:238). Table 1 is a synopsis of the false claims of the schismatics29 regarding sin.

In the protasis of these verses (1:6, 8, 10), the Elder starts with three assertions:30 'If we say that ...' The first claim (1:6) marks a clear contradiction between the claim (κοινωνίαν εχοµεν µετ' αύτοΰ) and the conduct maintained (έν τω σκότει περιπατώµεν).31 Verses 1:8 and 10 relate closely to verse 1:6 in the sense that it is as wrong to deny, as a way of conduct, both human sinfulness32 (1:8) and the practice of sin (1:10) in one's life.33

In the apodosis of these verses (1:6, 8), the Elder pronounces a condemnation on this conduct by stating that 'we lie' (ψευδόµεθα/έαυτούς πλανώµεν). In his condemnation of these claims, the Elder announces a verdict. Where he describes it as falsehood in verses 1:6, 8, he defines it even stronger in 1:10 with reference to God. The claim of being without sin suggests falsehood on God's part; it 'makes him a liar' (ψεύστην ποιοΰµεν αύτόν).

The consequences of these claims are that they hamper fellowship with both God and other believers in the family (cf. 1:6, 7). Such a person walks in darkness: 'we do not do the truth' (1:6) and 'the truth is not in us' (1:8). This all proves that the truth is not in these people; they do not do the truth and do not have God's word abiding in them (1:10) (Van der Merwe 2007:238).

In these three conditional assertions, the reader can feel (experience) how tension builds up when reading the text. It builds up within two parallel negative sets of statements. In the first set, the dichotomy of lie and truth in verses 1:6, 8 creates a tension which culminates in the statement about the absence of the word of God in such a person's life (1:10). In the second set, the tension is strengthened when the person who denies having sin is involved in the Elder's use of the reflexive first person pronoun, εαυτούς [ourselves]. The condemnation builds up from being accused of being a liar (ψεύδος), to being accused of being a deceiver (πλάνη) and culminates in making God a liar (Thomas 2004:74, 85).34

The Elder creates a negative spirituality when he nullifies the claims of do not live in sin, to have no sin or do not sin with references to that they were not doing the truth, the truth is not in them and also that the word of God is not in them. This creates a lived experience of emptiness (ούκ εστιν εν ήµΐν), worthlessness (ού ποιοΰµεν την αλήθειαν) and guilt (εαυτούς πλανώµεν and ψεύστην ποιοΰµεν αύτόν). With all the references to sin the Elder creates a lived awareness that these readers are not without sin. If they do not confess it, then they will continue to live in darkness. According to Sen (2011) the term 'darkness' immediately creates 'the image of "negative" in the mind, and thus there is a judgment towards it, which closes down any receptivity to want to understand it at a deeper level'.

A lived experience of forgiveness

Confession and forgiveness of sin

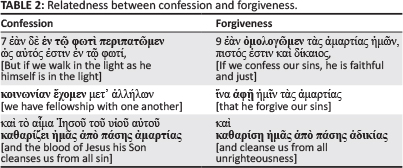

When people then confess their sins, they will be cleansed, receive forgiveness and enjoy fellowship. When reading verses 7 and 9 the reader immediately becomes aware of the semantic relatedness between these two verses with regard to these things. This relatedness is evident in Table 2.

The first semantic relatedness occurs between εν τω φωτί περιπατώµεν [live in the light] and όµολογώµεν τάς αµαρτίας [confess sins] (also ώς αύτός εστιν εν τω φωτί [as he is in the light] and πιστός εστιν καί δίκαιος [is faithful and just]), the second between κοινωνίαν εχοµεν [have fellowship] and αφή ήµΐν τάς αµαρτίας [forgive sins] and the third between καθαρίζει ήµας από πάσης αµαρτίας [cleanse from all sin] and καθαρίση ήµας από πάσης αδικίας [cleanse from all unrighteousness]. The function of this relatedness is a matter of both emphasis and explanation.35

The conditional particle εάν, in combination with both the verbs περιπατώµεν and όµολογώµεν (both present subjunctive), sets the tone for the experience (εχοµεν ... καί and ίνα) of forgiveness and cleansing which will consequently result in fellowship. The adversative δέ [but] in 1:7 underscores the contrast (Smalley 1989:23) with the statement in 1:6. According to Smalley (1989:30), the conditional particle εάν in 1:9 is also 'an adversative force' which can be translated as but if.36 Marshall (1978:112) adds another related perspective to verse 1:7. According to him, 1:7 creates a consciousness of sin in the mind of the readers when they read the text. This then implies that it urges and moves the readers to confess their sins and to live in the light.37

With the repetition of the three personal pronouns in verse 1:9, ήµών [of us], ήµΐν [to us] and ήµας [us], and the personal pronoun, ήµας, and reciprocal pronoun, αλλήλων, in 1:7, the Elder tries to let the readers experience personally what has been written. God's forgiveness is essentially personal and concerned with the individual (see Smalley 1989:32). This emphatic repetition of the pronouns draws the reader into the event to become involved in this experience of fellowship (µετ' αλλήλων) through confession and the forgiveness of sins.

The first relatedness that occurs is between εν τω φωτί περιπατώµεν and όµολογώµεν τάς αµαρτίας ήµών. The words τάς αµαρτίας refer to those who walk in the light as God is in the light.38 The Elder is, at this point, less concerned about defining what 'walking in the light' or 'the darkness' means.39 Here he is actually more concerned about explaining the consequences of walking in the light, and also how walking in the light can be accomplished. For him, 'walking in the light' (fellowship) can be accomplished only through the confession of sins (cf. Akin 2001:74) and has, in this context, three consequences: (1) 'fellowship with one another' (1:7), (2) 'the forgiveness of sins (1:7, 9) and 'the cleansing from all unrighteousness' (1:7, 9).

However, in these two verses, the Elder focuses the attention on God: ώς αύτός εστιν εν τω φωτί (1:7) ... πιστός εστιν καί δίκαιος (1:9). In verse 7, God is used by the Elder in a comparative way (ώς)40 with regard to 'walk in the light', and in verse 9, the focus is on God's attributes, that is, he is 'faithful' and 'just' in the act of forgiveness.41 Although his name is not mentioned in both these verses, he is prominent in both because he 'exists in the light', and he is 'faithful' and 'righteous'.42 Brown (1983:210) explains that πιστός εστιν καί δίκαιος reflects 'a covenant attitude43 toward God'. The reference that he is faithful was meant to be interpreted by those readers that he is 'reliable', which qualifies God as one whom the believers can trust and depend upon.44 That he is just (or righteous, see 2:1) expresses 'that God is always doing what is in accordance with his own will, which is to be good and merciful towards men' (Haas et al. 1994:31). Thus, it is God who makes possible forgiveness and fellowship.

The second relatedness refers to the relation between 'we have fellowship with one another' (1:7a, κοινωνίαν εχοµεν µετ' αλλήλων) and 'the forgiveness of sins' (1:9, άφη ήµΐν τάς άµαρτίας). This is to say that those who do have fellowship with God as they walk in the light will also have fellowship with one another (cf. Lieu 1991:43). Thus, there is no real experience of fellowship with God if there is no experience of fellowship with other believers45 (Smalley 1989:24). For the Elder, 'salvation is not some individualistic, pietistic experience, but must be rooted and grounded in community' (Thomas 2004:77).

However, this 'fellowship' is only possible when sins are forgiven. God's forgiveness means that he no longer holds the sins of people against them; he cancels their 'debt' (cf. Mt 6:9-15; 18:21-35) (Kistemaker & Hendriksen 2001:246).46 For Haas et al. (1994:31), the forgiveness of sin implies that sin disappears completely.47 The Elder projects an ongoing familial situation (if we walk in the light as he himself is in the light) in which people acknowledge their transgressions continuously (Smalley 1989:31; cf. also Haas et al. 1994:27f.).48 Therefore, the forgiveness that the Elder discusses in verses 1:7 and 1:9 can be understood as parental or familial forgiveness, not judicial forgiveness. Christian believers receive judicial forgiveness once and for all when they receive Jesus as their personal Saviour (Eph 1:7; Rm 5:6-11). Believers need judicial forgiveness49 only once. They need parental or familial forgiveness whenever they sin (Walls & Anders 1999:159). Thus, fellowship implies the forgiveness of sins, which makes the cleansing from sins effective (Yarbrough 2008:63).

The third relatedness refers to the two references with regard to the cleansing from sin which forms a parallelism: καθαρίζει ήµας άπό πάσης άµαρτίας and καθαρίση ήµας άπό πάσης άδικίας. The only two differences, though complementary, in this parallelism are: (1) the different tenses of the verb καθαρίζω and (2) the different words used for transgressions. In verse 1:7, the verb καθαρίζω is used in the present tense to express duration; God's continuous deed of purification of sin due to the crucifixion of Jesus (blood of Jesus) (cf. Haas et al. 1994:28; Painter 2002:156). The Elder imagines a situation in which his adherents acknowledge their sins in a continuous way. For him, living in the light involves sincere, continuous acknowledgement of one's sins (cf. Kruse 2000:68). The same verb is used in 1:9 in the aorist subjunctive form to indicate that God has dealt (cleansed) completely with sin that has been confessed. It is something of the past.50

Thomas (2004:83) argues that the Elder's use of the noun, άδικίας [unrighteousness], is an intentional play on the reference to God, who is δίκαιος [righteous]. Therefore, the phrases that constitute the parallelism are used synonymously.51 The plural, sins (τάς άµαρτίας), probably indicates the confession of particular acts of sin,52 rather than the acknowledgment of 'sin' in general (Smalley 1989:31; Thomas 2004:82).53 He also says that the singular phrase, ' every54 kind of unrighteousness' (πάσης άδικίας), refers to the confession of sin in detail (cf. Smalley 1989:32).

The achievement of fellowship with God produces an awareness of God's holiness and man's unholiness or sin (Smalley 1989:24). They 'walk in the light' with him, and the result of such conduct is that the blood of his Son, Jesus, purifies them from their sins. If the parallel of 'walking in the light' is 'being purified from every sin', then the walking in the darkness might best be interpreted here as walking in sin (Kruse 2000:65). The 'awareness' of forgiveness creates an awareness of purification by the Christian believer.

Finally, the Elder focuses on how forgiveness can be obtained to make the 'lived experiences' of fellowship a reality. The accomplishment to 'live in the light' occurs according to the Elder only through 'the confession' and 'the forgiveness of sin'. Therefore, it can be deduced that the experience of forgiveness and purification from sin is generated in the interplay of linguistics: semantics, rhetoric, words and concepts.55 The conditional particle (έάν) in both verses 7 and 9 prepares the reader for what is to follow.56 Here the experience is bound up with thinking.57 The call, 'to live in the light' and for 'the confession of sins', creates an expectation as well as a motivation within the reader. The consequence of forgiveness, only used here in this passage,58 creates an experience of satisfaction and thankfulness. The reference in verse 1:9 to the need for 'sins' to be acknowledged makes the 'lived experience' even more personal. This verse is one of the most quoted verses in the Bible.

The forgiveness of sin experienced

'No authentic Christian spirituality exists without defining reference to Jesus Christ' (Saunders 2002:4). Nowhere in 1 John do we find a text that captures the reader's imagination, relating to Jesus' involvement in the forgiveness of sin, so much as the Elder did it in this passage (1:5-2:2). Although the verb άφίηµι [forgiveness] does not occur in any of the three listed texts in the table below, it is intensely suggested by the Elders' use of the verb άφίηµι in verse 1:9 and the multiple appearances of the noun αµαρτίας [sin]. He describes Jesus' involvement in God's act of the forgiveness of and purification from sin three times in this passage, giving different perspectives. This technique of providing three different perspectives has only been used by the Elder. Nowhere else in the New Testament (NT) will you find the application of this format. The Elder succeeds in creating images of events in the minds of the readers. He wants them to recall these events so that, when he shares with them the involvement of Christ in God's act of forgiveness, it would make sense and become real to them.

Table 3 is an analysis and synopsis of the texts about Jesus' contribution to the forgiveness of sins. These texts substantiate the references to and the reality of the forgiveness of sins and purification from all unrighteousness.

The first reference, τό αίµα Ίησοΰ του υίοΰ αύτοΰ καθαρίζει ήµας άπό πάσης αµαρτίας (1:7), focuses on the act of forgiveness (purification). For the Elder, the forgiveness of sin(s) revolves around the soteriological events connected to Christ. In this pericope, he refers to one such act metaphorically as 'the blood of Jesus' (τό αίµα Ίησοΰ), the son of God (του υίοΰ αύτοΰ). The noun 'blood' is in this context a metaphor59 for the crucifixion of Christ. The background of it is located in Jewish sacrifice. In the Old Testament (OT), blood (דם) was regarded as the seat of life (Lv 17:11). Thus, in terms of a sacrifice, as means of atonement between God and man, the blood of the victim was its life yielded up in death. When the 'blood' of the victim was shed, it guaranteed the effectiveness of the sacrifice for the worshipper (cf. Ex 30:10; Lv 16:15, 19) (Kruse 2000:64; Smalley 1989:25). Thus, the blood is not a magic potion or does not have a magical quality, but the shedding of blood refers to the cultic event in which the redemption has been constituted (Yarbrough 2008:57). By virtue of the cleansing effect of Jesus' atoning death, believers' sins are forgiven. In effect, they are sinless in God's sight (though not in themselves) and fit for fellowship with him (Akin 2001:75; Thomas 2004:78).

The Elder's reference to 'blood' (of Christ, 1:7) brings to mind the sacrificial and forensic event for the forgiveness (cf. Smalley 1989:32) of sins. Here the Elder links the cross events (τό αίµα Ίησοΰ) with the customs of Israel: daily sacrifices and the Day of Atonement. This recall of sacrificial events would add meaning and lead to the re-experience of Jesus' sacrificial act for the forgiveness of sins. The reference to the blood of Christ has nothing to do with the initial salvation, which is fully guaranteed to believers the moment they come to faith. Rather it has to do with the righteousness of God in permitting his, far from perfect, children to live in his presence, the light (Hodges 1972:55).

The second reference to Jesus' soteriological activities in this pericope is that believers παράκλητον εχοµεν πρός τόν πατέρα [{we} have a paraclete with the Father, 2:1]. Turning his attention away from claims of the schismatics, the Elder now (2:1a) addresses his readers directly: 'I write this [these things] to you so that you will not sin' (ταΰτα γράφω ύµΐν ίνα µή άµάρτητε). This reference infers that walking in the light does not mean that those who conform to live in the light never sin. The difference between them and the schismatics is that they do not seek to hide that fact from God (Smalley 1989:24).

In the last part of the verse (2:1c), the Elder develops his theology of atonement, set out in 1:6-10 (Smalley 1989:36), and therefore continues with the words, 'but if anybody does sin (έάν τις άµάρτη, ...) to address this problem. With the personal pronoun, 'you' (ύµΐν), and the indefinite adjective, 'anyone' (τις), the Elder involves the reader in these statements about sin and acknowledges the reality that the children of God continue to sin (cf. Schnackenburg 1992:79). The Elder projects a situation in which believers yield to temptation and commit sin (Kruse 2000:72). The parallel to this projected situation is both surprising and encouraging for believers, for the Elder deals with the problem of sin positively: If anyone should sin, God has made provision for this (Smalley 1989:35). He notes that, if anyone sins, 'we have an advocate with the Father, Jesus Christ the righteous' (έάν τις άµάρτη, παράκλητον εχοµεν πρός τόν πατέρα Ίησοΰν Χριστόν δίκαιον). The Greek noun παράκλητος is translated in English as advocate.60 This noun is used to refer to Jesus Christ himself, and it is used in connection with his function in heaven.61

In the Fourth Gospel, the Holy Spirit is referred to as the paraclete. There his function was to testify in favour of Jesus over against a hostile world. The παράκλητος acts as an advocate for Jesus (Jn 16:7-11). In a similar fashion, in 1 John, Jesus functions as the παράκλητος of those who are members of the familia Dei. He speaks on their behalf in the presence of his Father when they sin. He is their advocate with the Father.62

This function and role of Jesus as paraclete have to be understood within the framework of the 'family court' (family concilium).63 Such a court served as an organ of discipline that was constituted by the core unit of the family. Normally the male head of the family conferred with other members before deciding how to act against a member of the family who has trespassed. The noun paraclete may suggest such a forensic situation. Thus, the advocacy of Jesus is needed when a family member has sinned; he must then approach the Father on behalf of the sinner (cf. Van der Watt 1999:500). Plutarch also points out that when conflicts arise between brothers, it is preferable that it be resolved internally, between those involved, and with justice as judge (Plutarch 483D, 488B-489B). If necessary, others can be present as arbitrators or witnesses, but these should be friends whom they have in common (Plutarch 483D, 490F-491A).

Jesus is the advocate who speaks to the Father to defend his followers when they have sinned. It, surely, should encourage readers. It suggests that he is pleading for mercy towards sinners. This, in turn, suggests that his role in the expiation or propitiation is to secure that mercy.64 The expiation or propitiation must obviously be balanced by the fact that, in verse 4:10, the Elder declares that God himself sent his Son to be that atoning sacrifice (Kruse 2000:74).

Again, this would have been a familiar concept to the readers because nowhere does the Elder explain the meaning or background of his usage of the paraclete. They would surely have recalled the familiar events of such court cases within their own families. Their understanding of this metaphor would have encouraged the readers. They would have re-experienced such a court event, but in the context of their own unique experience of it, they would have redefined and reconnected it to what Jesus was doing.

The third and last reference, αύτός ίλασµός έστιν περί τών αµαρτιών ήµών [he is the atonement for our sins], comes from verse 2:2. Here the Elder states that Jesus Christ is also the 'atoning sacrifice' (ίλασµός)65 for sins (see Smalley 1989:38-40 for a thorough discussion). Clues as to what the Elder means when he says that Jesus Christ is 'the atoning sacrifice for our sins' in verse 2:2 must be sought within the immediate context.66 The idea of the atoning sacrifice here is in juxtaposition with the idea of advocacy.67

However when the next verse is read, it becomes apparent that Jesus Christ is much more than an advocate who intercedes for those who have sinned. In the first case, he appears as an advocate in court, in the second as a sacrificing priest in the temple. According to Buchsel (1979:317) and Yarbrough (2008:78-79), the noun ίλασµός68 refers to a double action where God is 'propitiated' and sin 'expiated' (cf. also Bigalke 2013:8, 317). It is actually the cultic expiation by which sin is made ineffective. In the entire NT, ίλασµός occurs only in 1 John 2:2 and 4:10 and relates to the use of ίλάσκεσθαι in the LXX.69 This confirms how the Elder follows the OT. It refers to the purpose which God has fulfilled in the mission of his Son. Hence, it proves the graciousness of God (4:10). It means, therefore, the setting aside of sin as guilt against God. This is evident from the use of ίλασµός (2:2) in conjunction with παράκλητον (2:1) and with the act of confession in verses 1:8 and 1:10. Yet, if Christians do sin again, it forces them to approach him again who is the ίλασµός. For the Elder, the ίλασµός is much more than a concept of Christian doctrine; it is the reality by which he lives (Buchsel 1979:318).

In conclusion, all three of these references ' the blood of Christ,' 'advocacy' and 'atoning sacrifice' create historical images, situations, events and experiences in the mind of the reader in terms of time and space when they recall them. These familiar images created specific lived experiences of the forgiveness and remittance of sin amongst the readers. The reader, who is acquainted with these events and the OT teaching of it could redefine and re-experience those events in a new way. This was such an intense experience for those 1st-century people that it gave them hope (Yarbrough 2008:76), strength and encouragement to continue to believe. The remembrances prompted re-experiences and experiences of Jesus existentially. The Elder used these events to draw the reader into the events, which he described using the terms: blood of Christ, paraclete, atoning sacrifice.

The forgiveness of 'all' sin and reconciliation for the 'whole' world

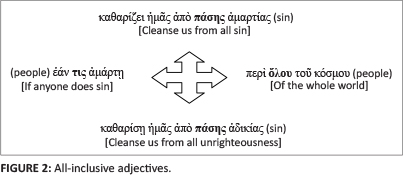

Throughout the ages, quantity always had some influence on people. In this pericope (1:5-2:2), the Elder also focuses the attention on quantity to influence the reader. The adjective 'all' (πάσης) is used in both verse 1:7 and 1:9 and refers to the quantity of sin. In verse 2:1, the Elder also uses the indefinite adjective 'anyone' (τις)70 and in verse 2:2 the adjective 'whole' (δλου) to refer to the number of people. Hence, he uses these adjectives four times in this short pericope. Therefore, it must have a particular function.

It seems to me that the rationale behind using 'all-inclusive language'71 is, firstly, to focus the attention on the phenomenal salvific and forgiveness events executed by God through Jesus Christ. Secondly, with these all-inclusive adjectives, the Elder creates a lived experience of the greatness of God's love, forgiveness and grace. Figure 2 helps to analyse and understand it.

In this pericope, there is one reference to the 'forgiveness of sins' and two references to the 'cleansing from sin', which forms the following parallelism:

καθαρίζει ήµας άπό πάσης αµαρτίας

καθαρίσΐήµας άπό πάσης αδικίας

The references to the 'cleansing' (καθαρίζω) of 'all sin' (singular), in both 1:7 and1:9, deals with the individual acts of unrighteousness.72 It deals with the cleansing from every sin (Kruse 2000:65; Walls & Anders 1999:157). This statement regarding the cleansing of sins (plural) views sin as a collective whole (Painter 2002:156) or a magnitude of transgressions (Kistemaker & Hendriksen 2001:246). In verse 1:7, the cleansing is attributed to 'the blood of Jesus' whilst in verse 1:9 it is attributed to 'God' (Thomas 2004:83). Here Jesus' blood (referring to the crucifixion) is the medium used for the cleansing from sin whilst God is the one who performs the act.

The Elder has already discouraged sinful behaviour of any kind. Now, in typical balanced style, he deals with the problem of sin positively: If anyone should sin, God has made provision for this. The fact that, once again, the aorist tense is used (έάν τις άµάρττ| [if any should sin]) indicates that acts of sin are in mind, not the state of sin (Smalley 1989:35f.). In both cases, he uses the singular adjectives to point out a limitless number of people. On the one hand, he uses the indefinite singular adjective τις which can have the meaning of 'anyone, someone, something' (Danker 2000:1007) and, on the other hand, the singular adjective δλου, meaning 'whole, entire, complete' (Danker 2000:704).73

The phrase τοΰ κόσµου [the world] compliment the adjective δλου [whole] in order to stress the universality of the scope of expiation (Painter 2002:159). The Elder wants to emphasise that the kind of sin or kind of person does not matter when it concerns God's forgiveness of sin. In this relatively young and new religion, such a view would have created a sense of awe in the readers' mind. With these words, the Elder gave his readers hope, a spirituality of hope. All the sins of the whole world can be forgiven. The death of Christ 'provides the basis throughout all human history for God to extend patience to those who merit his repetition' (Yarbrough 2008:79).

Conclusion

Humans cannot conceptualise themselves without language. Language can change an event into an experience: to look at something plus a word equals 'to see' something, to listen to something plus a word equals 'to hear' something. Thus, language gives meaning and experience (cf. Cupitt 1998:61). The 20th-century poet Kathleen Raine (1992:39) reflects on the power of language by suggesting that language is not just an aid to understanding, but it also contains the potential to broaden and deepen experiences.74

Through the high frequency of the personal pronoun (ήµας), the Elder endeavours to involve the readers to become part of the events referred to in the text. He wants them to become intensely aware of and experience these matters. To achieve this, the Elder creates spiritual experiences in the minds of the readers through various language devices such as metaphoric language (God is light and in him there is no darkness), dialectic language (light versus darkness; truth versus lie; righteousness versus unrighteousness; sin versus cleansing; do not have sin versus confess sin; εάν εϊπωµεν... ούχ versus εάν plus a positive act), cultic language (blood of Jesus, atoning sacrifice), forensic language (paraclete), atypical language (τό αίµα Ίησοΰ, ίλασµός, παράκλητος) and all-inclusive language (all, whole, anyone).

This language is embedded in his pronouncement that 'God is light and in Him there is no darkness'. The awareness of sin and the experience of forgiveness are embedded in the experiences of the metaphorical and dialectical use of the nouns, light and darkness. The awareness of sin is further supported by the high frequency of the references to sin and the shocking consequences to which the denial of sin leads. All this should lead those guilty of sin to confess their sins in order to receive forgiveness.

The radical negative 'awareness' of sin was also created by the artistically, well-planned conditional particles which created a rhythm in the text and the rhetoric created in the text by the Elder. The six conditional particles, εάν, set the stage to create different lived experiences. In conjunction with the first-person plural, εϊπωµεν ([if we say], 1:6, 8, 10), it involves the reader in the applicable events. The harsh references create a very negative and shocking experience. People who sin surely live in darkness. They do not have any fellowship with the children of God. They are guilty of lying and are deceivers. They do not do the truth; even worse, the word of God is not for them. They consequently turn God into a liar (cf. 1 Jn 1:6, 9, 10).

According to the context of the letter, some people thought they were without sin and are God's children. Now they hear the opposite; they may not be without sin. This is shocking and disturbing.

The awareness of forgiveness, again, is generated through descriptive cultic (blood of Jesus and expiation), forensic (paraclete), atypical (cleans, expiation, paraclete) and all-inclusive (all [twice], whole, anyone) language. The Elder uses experiential, cultic and forensic terminology to allow the reader to recall and re-experience those events. Jesus Christ became a new hermeneutical principle and tool for the understanding and redefining of sin and forgiveness. This gives new meaning to those events.

Here we see how the Elder's powerful experiences of the historical Jesus (1:1-4) and his own spirituality of living in the light led to the creative formulation of his doctrinal framework. With these allusions, the Elder gives his experiences a typically deeper meaning, hidden below the surface of the text. The Elder gives the reader a key for the understanding of how fellowship with God is to be experienced - only through the confession and forgiveness of sin through Jesus Christ.

This research has pointed out that 'lived experiences' evolves not only from the senses (hear, see, feel, smell and taste), but it evolves also from language.

Acknowledgements

Competing interests

The author declares that he has no financial or personal relationship(s) that may have inappropriately influenced him in writing this article.

References

Akin, D.L., 2001, 1, 2, 3 John, Broadman & Holman Publishers, Nashville. (The New American Commentary, vol. 51). [ Links ]

Azari, N.P. & Birnbacher, D., 2004, 'The role of cognition and feeling in religious experience', Zygon 39(4), 901-917. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9744.2004.00627.x [ Links ]

Balz, H.R. & Schneider, G., 1990, Exegetical dictionary of the New Testament, vol. 2, Eerdmans, Grand Rapids. [ Links ]

Baylis, C.P., 1992, 'The meaning of walking "in the darkness" (1 John 1:6)', Bibliotheca Sacra 149, 214-22. [ Links ]

Bigalke, R.J., 2013, 'The meaning of hilasmos in the first epistle of 1 John 2:2 (Cf. 4:10)', PhD dissertation, Department of New Testament, University of Pretoria. [ Links ]

Brown, D., 2008, God & mystery in words: Experience though metaphor and drama, Oxford University Press, Oxford. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/acprof:o so/9780199231836.001.0001 [ Links ]

Brown, R.E., 1983, The epistles of John, Doubleday, Garden City. [ Links ]

Brooke, A.E., [1912] 1976, A critical and exegetical commentary on the Johannine epistles, T. & T. Clark, Edinburgh. [ Links ]

Bruce, F.F., 1970, The epistles of John, Pickering & Inglis Ltd, London. [ Links ]

Büchsel, H., 1979, s.v. 'ίλασµός' [atonement], in G. Kittel (ed.), Theological dictionary of the New Testament, Eerdmans, Grand Rapids, pp. 317-318. [ Links ]

Bultmann, R., 1973, The Johannine epistles, Fortress, Philadelphia. (Herder). [ Links ]

Conzelmann, H., 1974, s.v. 'φώς κτλ' [light], in G. Kittel (ed.), Theological dictionary of the New Testament, Eerdmans, Grand Rapids, pp. 311-358. [ Links ]

Culpepper, R.A., 1998, The gospel and letters of John, Abingdon Press, Nashville. [ Links ]

Cupitt, D., 1998, Mysticism after modernity, Blackwell Publishers, Oxford. [ Links ]

Danker, F.W. (ed.), 2000, Greek-English lexicon of the New Testament and other early Christian literature, 3rd edn., University of Chicago Press, Chicago. (W. Bauer, F.W. Danker, W.F. Arndt and F.W. Gingrich, BDAG). [ Links ]

Deissmann, A., 1965, Light from the ancient East: The New Testament illustrated by recently discovered texts of the Graeco-Roman world, Baker Book House, Grand Rapids. [ Links ]

Derickson, G.W., 1993, 'What is the message of 1 John?', Bibliotheca Sacra 150, 89-105. [ Links ]

De Vaux, R., [1961] 1973, Ancient Israel: Its life and institutions, Darton, Longman & Todd, London. [ Links ]

Dodd, C.H., 1946, The Johannine epistles, Hodder and Stoughton, London. [ Links ]

Dodd, C.H., 1953, The Johannine epistles, Hodder and Stoughton, London. [ Links ]

Filson, F.V., 1969, 'First John: Purpose and message', Interpretation 23(3), 259-276. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/002096436902300301 [ Links ]

Friberg T., Friberg B. & Miller N.F., 2000, 'Τις' [someone], in Analytical lexicon of the Greek New Testament, Baker books, Grand Rapids, p. 381. (Baker's Greek New Testament library, vol. 4). [ Links ]

Gräbe, I., 1992, 'Metafoor', in T.T. Cloete (ed.), Literêre terme en teorieë, bl. 288, HAUM-Literêr, Pretoria. [ Links ]

Grayston, K., 1981, 'The meaning of παράκλητος [paraclete]', Journal for the Study of the New Testament 13, 67-82. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0142064X8100401305 [ Links ]

Haas, C., Jonge, M.D. & Swellengrebel, J.L., 1994, A handbook on the letters of John, United Bible Societies, New York. [ Links ] (United Bible Societies handbook series).

Hahn, H-C., 1976, s.v. 'Light', in C. Brown (ed.), Dictionary of New Testament Theology, Paternoster Press, Exeter, vol. 2, pp. 490-495. [ Links ]

Hiebert, D.E., 1988, 'An exposition of 1 John 1:1:5-2:6', Bibliotheca Sacra 145, 329-342. [ Links ]

Hodges, Z.C., 1972, 'Fellowship and confession in 1 John 1:5-10', Bibliotheca Sacra 129, 48-60. [ Links ]

Hurtado, L.W., 2003, Lord Jesus Christ: Devotion to Jesus in early Christianity, Eerdmans, Grand Rapids. [ Links ]

Johnson, T.F., 1993, 1, 2, and 3 John, Hendrickson Publishers, Peabody. [ Links ]

Kistemaker, S.J. & Hendriksen, W., 2001, Exposition of James and the epistles of John, Baker Book House, Grand Rapids. (New Testament Commentary). [ Links ]

Krimmer, H., 1989, Johannesbriefe, Neuhausen-Stuttgart, Hänssler. [ Links ]

Kruse, C.G., 2000, The letters of John, Eerdmans, Grand Rapids. (The Pillar New Testament commentary). [ Links ]

Lieu, J.M., 1991, The theology of the Johannine epistles, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511621376 [ Links ]

Louw, J.P. & Nida, E.A., 1996, Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament based on semantic domains, vol. 1, 2nd edn., United Bible Societies, New York. [ Links ]

Malatesta, E., 1978, Interiority and covenant, Biblical Institute Press, Rome. [ Links ]

Marshall, I.H., 1978, Epistles of John, Eerdmans, Grand Rapids. [ Links ]

Otto, R., [1923] 1975, The idea of the holy: An inquiry into the non-rational factor in the idea of the divine and its relation to the rational, 2nd edn., Oxford University Press, Oxford. [ Links ]

Painter, J., 2002, 1, 2, and 3 John, Liturgical Press, Collegeville. [ Links ]

Petersen, N.R., 1993, The gospel of John and the sociology of light: Language and characterization in the Fourth Gospel, Trinity Press International, Valley Forge. [ Links ]

Plutarch, 1949, Moralia, transl. W.C. Helmbold, Cambridge, Harvard University Press. [ Links ]

Raine, K., 1992, Living with mystery: Poems, Golgonooza Press, Ipswich. [ Links ]

Spirituality and Christianity, n.d., The importance of language in emancipatory theology, viewed 03 July 2012, from http://spiritualityandchristianity.com/theological-topics/the-impor tance-of-language-in-emancipatory-theology [ Links ]

Saunders, S.P., 2002, '"Learning Christ": Eschatology and spiritual formation in New Testament Christianity', Interpretation 56(2), 131-167. [ Links ]

Schnackenburg, R., 1992, The Johannine epistles: Introduction and commentary, Crossroad, New York. [ Links ]

Sen, 2011, 'Dark nature and light nature in humans', in Clam down mind, viewed 17 February 2013, from http://www.calmdownmind.com/dark-nature-and-light-nature-in-humans [ Links ]

Shelfer, L., 2009, 'The legal precision of the term παράκλητος [paraclete]', Journal for the Study of the New Testament 32(2), 131-150. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0142064X09350961 [ Links ]

Smalley, S.S., 1989, 1, 2, 3 John, Word, Incorporated, Dallas. (Word Biblical Commentary, vol. 51). [ Links ]

Stott, J.R.W., 1964, The epistles of John: An introduction and commentary, Inter-Varsity Press, Leicester. (Tyndale New Testament Commentaries). [ Links ]

Strecker, G., 1996, The Johannine letters, Fortress Press, Minneapolis. [ Links ]

Thomas, J.C., 2004, A pentecostal commentary on 1 John, 2 John, 3 John, The Pilgrim Press, Cleveland. [ Links ]

Tollefson, K.D., 1999, 'Certainty within the fellowship: Dialectic discourse in 1 John', Biblical Theology Bulletin: A Journal of Bible and Theology 29, 79-89. [ Links ]

Van der Merwe, D.G., 2005, 'Understanding "sin" in the Johannine epistles', Verbum et Ecclesia 26(2), 543-570. http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/ve.v26i2.240 [ Links ]

Van der Merwe, D.G., 2007, '"Having fellowship with God" according to 1 John: Dealing with the change in social behavior', Acta Patristica et Byzantina 18, 231-267. [ Links ]

Van der Merwe, D.G., 2009, 'Animosity in the Johannine epistles: A difference in the interpretation of a shared tradition', in J.T. Fitzgerald, F.J van Rensburg & H.F. van Rooy (eds.), Animosity, the Bible, and us: Some European, North American, and South African perspectives, pp. 231-262, Society of Biblical Society, Atlanta. [ Links ]

Van der Merwe, D.G., 2012, 'Those who have been born of God do not sin, because God's seed abides in them: Soteriology in 1 John,' HTS Teologiese Studies/ Theological Studies 68(1), 691-700. http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/hts.v68i1.1099 [ Links ]

Van der Watt, J.G., 1999, 'Ethics in First John: A literary and socioscientific perspective', Critical Biblical Quarterly 61, 491-511. [ Links ]

Van der Watt, J.G., 2000, Family of the King: Dynamics of metaphor in the Gospel according to John, Brill, Leiden, Boston. [ Links ]

Walls, D. & Anders, M., 1999, I & II Peter, I, II & III John, Jude, Broadman & Holman Publishers, Nashville. (Holman New Testament Commentary, vol. 11). [ Links ]

Wengst, K., 1976, Háresie und Orthodoxie im Spiegel des ersten Johannesbriefes, Gütersloher Verlagshaus, Gütersloh. [ Links ]

Whitacre, R.A., 1982, Johannine polemic: The role of tradition and theology, Scholars Press, Chico. (Society of Biblical Literature dissertation series, 67). [ Links ]

Yarbrough, R.W., 2008, 1-3 John, Baker Academic, Grand Rapids. (Baker exegetical commentary on the New Testament). [ Links ]

Zodhiates, S., 2000, The complete word study dictionary: New Testament, AMG Publishers, Chattanooga. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Dirk van der Merwe

189 Kotie Avenue

Murrayfield 0184

South Africa

Email:vdmerdg@unisa.ac.za

Received: 30 May 2013

Accepted: 08 Sept. 2013

Published: 14 May 2014

1. See http://spiritualityandchristianity.com/theological-topics/the-importance-of-language-in-emancipatory-theology

2. Most scholars regard 1:5-2:2 as a pericope: Akin (2001:62), Brown (1983:191), Haas, Jonge and Swellengrebel (1994:21), Johnson (1993:28), Kistemaker and Hendriksen (2001:241), Kruse (2000:61), Schnackenburg (1992:70), Stott (1964:70), Thomas (2004:61). Scholars with slightly different views are: Brooke ([1912] 1976:10), Painter (2002:142), Smalley (1989:17), Strecker (1996:25).

3. The Elder uses the following exceptional language features: • repetition: εάν [εϊπωµεν] [if we say], κοινωνίαν [fellowshipj, περιπατώµεν [walk/live], αλήθεια [truth], ψευδόµεθα/ ψεύστην [lie/liar] • metaphoric language: φωτί [light], σκότει [darkness], τό αίµα Ίησοΰ του υίοΰ αύτοΰ [the blood of Jesus], παράκλητον [paraclete]• dialectic language: φωτί X σκότει [light X darkness], αλήθεια X ψεύστην [truth X lie], constituted by the negative particle ουκ (1:5, 8, 10, 2:2); cf. the excellent article of Tollefson (1999:79-89) on dialectic discourse in 1 John• atypical language: παράκλητον [paraclete] (forensic), καθαρίζει [forgive], αφή [cleanse] and ΐλασµός [atonement] (cultic)• all-inclusive language: πάσης [all] (1:7, 9), όλου [whole] (2:2), τις [anyone] (2:1). From these language features, it is evident that the Elder is a writer, a wordsmith. He is a writer highly conscious of language, a person who conveys his message in order to involve his readers in the events which he discusses. He plays a game with language, creating semantic networks which support the rhetorical development of the text (cf. Cupitt 1998:61).

4. See Figure 1 for an analysis of 1 John 1:5-2:3.

5. In I John 4:12 (cf. also Jn 1:18 and 1 Jn 3:6; 4:20), the Elder refers to the fact that '[n]o one has ever seen God'. In 1 John 1:5, he also uses metaphors to speak about God.

6. Petersen (1993:9) points out that, although we can understand individual words which are drawn from everyday language, the words do not mean or denote in our usage what they are used for in everyday language and experiences. They are sometimes used to refer to things that are not part of everyday experiences.

7. Haas et al. (1994:23), Smalley (1989:20). For Strecker (1996:25), it intends no definition of the essence, the being of God in and for God self'.

8. See Akin (2001:63), Kistemaker and Hendriksen (2001:242) and Smalley (1989:20).

9. Smalley (1989:19-20; see also Hodges 1972:50) briefly discusses both the Hellenistic and Jewish background of the metaphoric image as follows. The Elder describes the character of God in his epistle as 'to be Light' (ό θεός φως έστιν). Being light was also a feature of Zoroastrianism. Gnosticism used to be a 'religion of light' ('developed in the dualist systems of Manichaeism and Mandaism') in which this dualism of light and darkness oppose one another as hostile and independent powers. See also the works of Hahn (1976:490-495) and Conzelmann (1974:IX, 310-358). However, the context most probably familiar to the Elder was Judaism. The dualism of light-darkness strongly featured in the Qumran community (cf. 1QS 1:5, 9-10; 5:19-21; 1QH 4:5-6; 1QM 13:15 and note the description of God as 'perfect light' in 1QH 18:29) as well as the Old Testament (Ps 119:130; Is 5:20; Mi 7:8i; see also Ps 27:1). Therefore the ex-Jewish members of the Johannine community would have appreciated this image (Smalley 1989:20; Thomas 2004:73).

10. Brown (2008:47) makes a useful remark about metaphors: 'Language thus need not always be seen as a purely human instrument that can never stretch beyond our world except in the sense of providing pointers to the possibility of such experience in other contexts. Sometimes, it can in and of itself function as such a medium, most obviously in appropriate metaphors helping to bridge that gap.' He rounds this off with a reference to the work of Raine (1992), who argued that 'the metaphors help generate the image of an interconnected world and thus of a God from whom that intelligibility ultimately derives'.

11. Although these three things can be distinguished, with regard to God's character, they are closely interwoven to one another.

12. 'Due to the qualitative differences between the earthly and the divine, the divine can only be described in earthly knowledgeable terms with reference to earthly associations and categories. Hence, if the Elder wants to speak about God he does it by means of metaphors. Thus, when the Elder refers to God as light, this surface metaphor does not create the reality of light, but aims to describe that reality' (Van der Watt 2000:23). 'A surface metaphor is a basic metaphor in which both the tenor and vehicle are given' (Van der Watt 2000:20).

13. Nuanced differences occur amongst scholars on the interpretation and understanding of the Elder's statement: ό θεός φως έστιν [to be light]. According to Smalley (1989:20), it is 'a penetrating description of the being and nature of God: it means that he is absolute in His glory (the physical connotation of light), in His truth (the intellectual) and in His holiness (the moral)'. Krimmer (1989:26; cf. also Schnackenburg 1992:77) sees this metaphoric reference as 'eine Seinsaussage und eine Handlungsbeschreibung Gottes'. For Bultmann (1973:16) and Thomas (2004:77), the Elder's statement designates God's nature and the sphere of the divine. Malatesta (1978:96ff.) tries to relate the meaning to what the Bible says about the relation between God and light. Haas et al. (1994:32) suggest a shift from metaphor to simile, 'God's being is like light'. From a linguistic perspective, ό θεός [God], with the definite nominative article, is the subject. φως [light], without the article, is also nominative and subjective. Therefore the two terms and subjects cannot be interchanged. The qualitative predicate noun, φως, is used in a qualitative sense (Haas et al. 1994:31) to describe God as possessing the qualities of light. This is a reflection of God's nature. Therefore, the noun φως should not be interpreted literally (Hiebert 1988:331). The best way then to do justice to what is meant by the Elder using this metaphor is to turn around the entire process of interpretation. One has to consider the context (1:6-2:28) following this statement in 1:5. The text discusses three acts of moral conduct (do not sin, obey God's commandment, and do not love the world, but do the will of God). This becomes possible only through mutual abidance (living in the sphere of God). Thus, we can conclude that the light metaphor refers to God's nature (Bultmann 1973:16; Johnson 1993:28; Strecker 1996:25) and the sphere of the divine (according to Bultmann 1973:16) with ethical implications for the 'children of God' (according to the majority of scholars: Bruce 1970:41; Haas et al. 1994:32; Hiebert 1988:331; Painter 2002:128; Whitacre 1982:161). Thus, God's nature demands a specific way of conduct within the sphere of the familia Dei. Thomas (2004:72) points out that the readers would have known that, when similar statements were made in the Gospel of John (4:24), ethical or/and moral obligations would follow.

14. Hiebert (1988:331) adds an intellectual perceptive. Cf. also 1:10, ό λόγος αύτοΰ ούκ εστιν έν ήµΐν [his word is not in us].

15. See also Smalley (1989:20) for a combination of all three.

16. See Dodd (1953:201-205), Malatesta (1978:99ff.) and Stott (1964:70) for a discussion on the image of God as 'light'. See Stott (1964:70-74) on 'The symbolism of light in Scripture'.

17. According to Sen (2011:1), there is a judgment towards it, which closes down any receptivity to want to understand it at a deeper level'. In the Gospel of John, darkness is linked with the doing of evil deeds (Jn 3:19-20).

18. The references µένετε έν αύτφ (God), κοινωνίαν εχοµεν, έγνώκαµεν αύτόν (God) and είναι έν are related (cf.' Derickson 1993:97;Malatesta 1978:27), though understood as describing aspects of 'walking in the light' and the believer's relationship to the Father within the familia Dei. According to Derickson (1993:97) who studied the message of 1 John, 'abiding in him' (µένετε έν αύτφ) should be understood in the Pauline sense of 'walking in the Spirit'. This is supported in part by the Johannine use of abiding in John 15. 'Fellowship' (κοινωνίαν εχοµεν) should be understood naturally as expressing relationship or communion. 'Knowing God' is the result of walking with him in fellowship.

19. It differs from the fellowship referred to in 1:3 (to partake in the divine life through Jesus Christ) (cf. Thomas 2004:75).

20. Both the noun, κοινωνίαν, and the verb, περιπατωµεν, are words that evolve experience. See Lieu (1991:31) who also links 'fellowship' to 'religious experience' with the heading of a subsection: 'Fellowship with him': the language of religious experience.

21. Thomas (2004:75) refers to the emphasis of fellowship in verse 6 due to its position in the verse. I am of the opinion that 'fellowship' is one of the main themes (familia Dei, to have eternal life [5:13]) in 1 John. Painter (2002:149-153) argues against 'fellowship' as an important theme in 1 John.

22. Elsewhere the Elder also refers to God as 'he is faithful and just' (1:9), 'he is 'righteous' (2:29; cf. also 3:7, 10) and 'he is love' (4:8, 16). According to Smalley (1989:20), the declaration 'God is light' is a penetrating description of the being and nature of God: This means that God is 'absolute in his glory (the physical connotation of light), in his truth (the intellectual) and in his holiness (the moral)'.

23. In both the Old and New Testament, the character of God is usually expressed in terms of his actions, not his essence. In this respect, the Elder's view differs from the pagan Greek view, which focuses more on the essence of God's being than on his activities. Cf. Dodd (1946:107-110).

24. See 'obedience to his commandments' (2:3-5) and 'live as Jesus lived' (2:6).

25. According to Akin (2001:64) 'light' here represents the source of life. For Painter (2002:153), it expresses the idea of revelation.

26. See Van der Merwe (2005:543-570) for a thorough discussion of 'sin' in the Johan-nine epistles.

27. Two more pericopes occur where the Elder addresses sin (αµαρτίας), namely 1 John 3:4-10 and 5:16-19. Other forms of sin are also addressed by the Elder. See Van der Merwe (2005:543-570).

28. The character of sin is explained in terms of a dichotomy: walking in darkness versus walking in the light.

29. For a thorough discussion on the schismatics, see Wengst (1976) and Whitacre (1982). Cf. also Van der Merwe (2009:231-262).

30. Hiebert (1988:332) interprets all three claims in 1:6, 8, 10 as hypothetical. For me, to interpret it as expectational claims seem to be closer to the truth (cf. Van der Merwe 2007:238).

31. The first conditional sentence states that the schismatics are guilty of two offences. Firstly, they lie about their relationship with God. Jesus' message that God is light implies that fellowship between light and darkness is impossible. Therefore, their claim to have fellowship with God (whilst they walk in darkness) is false. Secondly, they are guilty of 'not doing the truth' (Smalley 1989:23). To claim fellowship with God whilst walking in darkness makes a person a liar (1:6); to claim to be sinless involves lying to oneself (1:8) and makes God out to be a liar as well (1:10). This prohibits any kind of fellowship in the familia Dei (Kruse 2000:66; also Akin 2001:74).

32. Scholars differ in their understanding of this reference to sin (αµαρτίαν ούκ εχοµεν). For Schnackenburg (1992:80), it means that they are free from the sin principle which operates in other human beings. Brown (1983:205) is of opinion that these schismatics were claiming not that they were by nature free from the sin principle but that they were not guilty of committing sin. Kruse (2000:66) argues that they probably meant that they had not sinned since they came to know God and experienced the anointing.

33. 'The verb refers to inner possession, and shows a person to be in a certain condition, or to have a certain emotion, which influences him continually. Thus "to have sin" means that one has the source and principle of sin in oneself, and is continually dominated by it. The expression does not refer here to sinful deeds (as it did in v. 7), but to a sinful attitude that is the source of sinful deeds, and implies personal guilt' (Haas et al. 1994:29). For Smalley (1989:32-33), the distinction between the references to sin in verses 1:8 (αµαρτίαν ούκ εχοµεν, noun) and in 1:10 (ούχ ήµαρτήκαµεν, verb) is that 1:8 refers to the principle of sin, (literally, 'we do not have sin', using the present tense of the verb), and 1:10 refers to its expression in sinful acts ('we have not sinned', using the perfect).

34. Thomas (2004:80, 81) points out that the Elder increases the intensity of the guilt in his reference that it is self-inflicted. Emphasis is attached to the reflexive first person pronoun εαυτούς [ourselves] which stands first in the Elder's condemnation of the assertion in 1:8.

35. Emphasis due to the repetition of the main message of the forgiveness of all sins and the semantic relatedness between these two verses, explanation due to the variance of words and phrases in communicating basically the same message.

36. The adversative force in 1:9 is caused by the contrast between verses 8 and 9 according to Painter (2002:145).

37. Marshall (1978:114) quotes Micah 7:18-20 and cites Deuteronomy 32:4, Romans 3:25 and Hebrews 10:23.

38. The verb περιπατέω also occurs in 2:6. There it relates 'to live as Jesus lived'. This metaphor of living in the light can then be understood as relating to how the Elder describes the Christian life in dialectic language throughout the epistle in relation to the other attributes of God and his Son: God is righteous and God is love. See also Van der Merwe (2007:231-267).

39. Baylis (1992:214-222) understands that 'walking "in the light" means receiving God's revelation of Himself through His Son, and receiving eternal life and forgiveness of sins' whilst 'walking "in the darkness" is walking in death, rejecting that revelation'.

40. The believer must walk in the light as (ώς) God is in the light.

41. The Elder introduces the pericope with reference to God. The first person, personal pronoun, referring to God, occurs 4 times in 1:5-7, referring 'to have fellowship with God'. Verses 1:8-2:2 consequently describe how it can be accomplished.

42. See Painter (2002:155) for a thorough discussion that God, and not Jesus, is the subject of the phrase πιστός εστιν καί δίκαιος in 1:9.

43. See also Thomas (2004:60) for a covenant connection.

44. Haas et al. (1994:31) render this adjective also to mean: 'unchangeable,' 'firm of inner being,' 'keeping his promise,' 'causing to be done (or not passing over) what he has said'.

45. See also 1 John 4:20-21: 'We love because he first loved us. Those who say, "I love God," and hate their brothers or sisters, are liars; for those who do not love a brother or sister whom they have seen, cannot love God whom they have not seen. The commandment we have from him is this: those who love God must love their brothers and sisters also.'

46. Painter (2002:156) correctly points out that such a situation can be understood in terms of being free from sin, though not as a state of being. This can be gleaned from verses 1:9 and 2:1. Also in verse 1:10, 'the possibility of sin is acknowledged' (Painter 2002:158).

47. Purification from sin is virtually equivalent to forgiveness of sins as the use of these two concepts in parallel in 1:9 indicates. The two concepts are also found in parallel in Jeremiah 33:8: 'I will cleanse them from all the sin they have committed against me and will forgive all their sins of rebellion against me.' Both verbs (άφη, καθαρίση), being aorist subjunctive in form, portray forgiveness and purification as complete, rather than ongoing actions (Kruse 2000:69). This forgiveness is taken further by the Elder, and in the next section (1:10-2:2), he again incorporates a mediator (Smalley 1989:26).

48. This duration is indicated by the use of the present (subjunctive) tense of both verbs περιπατωµεν and όµολογωµεν.

49. Walls and Anderson (1999:159) distinguish between familial and judicial forgiveness (see also Van der Merwe 2005:543-570). The forgiveness the Elder talks about in 1:9 can be understood as parental or familial forgiveness, not judicial forgiveness. The readers of 1 John received forensic forgiveness only once when they repented (Eph 1:7; Rm 5:6-11). They were, at that time, saved from the penalty of their sins. It is called judicial forgiveness because it is granted by God acting as a judge. After their salvation, they still continue to sin (Phlp 3:12; Ja 3:2, 8; 4:17; also cf. Smalley 1989:24). This sin does not cause them to lose their salvation (1 Jn 5:13-20; cf. Rm 8:37-39), but it does break the fellowship between them and God, just as the sin of a child or a spouse breaks the fellowship with parents or a mate.

50. άφιήµι reflects a legal background, literally meaning 'to let go, release' something. Here the guilt and liability to punishment for sin is released, that is, forgiven (cf. Brown 1983:211). For Haas et al. (1994:31), the verb άφίηµι 'implies that sin disappears as completely as dirt disappears from a person that is bathed.' The verb καθαρίζω 'expresses that sin, and the resulting guilt, are no longer taken into account ., just as in the case with debts that have been cancelled (cf. Luke 7:42f., 47f.).'

51. See Thomas (2004:83) and Yarbrough (2008:65) for variant understandings. Yarbrough (2008:65) argues 'that αµαρτία in 1:7 is a more generic term for failure to comply with God's will, whilst άδικία in 1:9 connotes specific acts of wickedness or wrongdoing.'

52. The use of the aorist subjunctive, ίνα µή άµάρτητε [in order that you may not sin], in 2:1 supports an interpretation of specific acts of wrongdoing since it refers to 'definite acts of sin rather than the habitual state' (Brooke [1912] 1976:23).

53. Kistemaker and Hendriksen (2001:246) differ from Smalley and Thomas. For them, it 'indicates the magnitude of our transgressions'.

54. Danker (2000:782) agrees with Smalley in the sense that the feminine adjective πασα refers 'to totality with focus on its individual components, each, every, any'. The adjective πάσης, used with a noun without the article and in the singular, emphasises the individual members of the class denoted by the noun every, each, any, scarcely different in meaning (Danker 2000:782).

55. Here the experience is linked to thinking.

56. For Thomas (2004:79), the initial mention of sin in 1:7 prepares the readers for the theme (sin) which dominates the rest of this pericope (1:8-2:2).

57. This author is aware of the complexity of and diverse opinions about religious experience. See the article of Azari and Birnbacher (2004:901-917).

58. The only other occurrence of the word in the Johannine letters is in 5:17 where άδικία is identified with αµαρτία (Smalley 1989:32).

59. The author of this article wants to distinguish between the reference to 'blood' as symbol (as used in the cult in the OT) and the reference to 'blood' used as metaphor in the NT, referring to the crucifixion of Jesus. Marshall (1978:112) also refers to the 'blood' as 'a symbolic way of speaking of the death of Jesus'. He links it with the OT meaning attached to blood.

60. This noun παράκλητος is found only here in 1 John and 4 times in the Gospel of John (14:16, 26; 15:26; 16:7). It is found nowhere else in the NT and not at all in the LXX. In the Gospel of John, the word consistently denotes the Holy Spirit. He was to be sent to be with the disciples on earth when Jesus returned to the Father. In seeking to understand the meaning of παράκλητος in this verse, it is helpful to begin with the meaning of the word in the ancient Hellenistic texts. Deissmann (1965: 336-37) provides references to these texts in which the παράκλητος is consistently portrayed as an advocate, one who speaks on behalf of the accused (see Kruse 2000:72).

61. The Elder expresses here the encouragement, 'we have an advocate with the Father' (πρός τόν πατέρα). This phrase recalls both John 1:1 where the Word is said to be in the presence of the Father (πρός τόν θεόν) and 1 John 1:2 where eternal life is said to have been in the presence of the Father (πρός τόν πατέρα). He has now been revealed to us.

62. Grayston (1981:67-82) has surveyed the usage of the word παράκλητος in early Greek writings in order to answer two outstanding questions about its use and meaning. According to him, his investigation confirms that παράκλητος did not derive its meaning from legal activity. It was a more general term which were sometimes used in legal contexts, meaning supporter or sponsor which fits its usage in 1 John. Shelfer (2009:131-150) argues that this noun is a precise calque for the Latin legal term advocates, 'meaning a person of high social standing on behalf of a defendant in a court of law before a judge'.

63. De Vaux ([1961] 1973:21-22) also makes a useful contribution to the understanding of the meaning of παράκλητος in his description of family solidarity in the Old Testament, referred to as the go'el. According to him, family members have, in a wider sense, an obligation to help and protect one another. In Israel, an institution existed which defined occasions when this obligation called for action. It was called the go'el, which originally meant 'to buy back or to redeem' or 'to lay claim to', but fundamentally, its meaning is 'to protect'. Although this institution has analogies amongst other peoples (i.e. the Arabs), in Israel, it took a special form with its own terminology. 'The go'el was a redeemer, a protector, a defender of the interests of the individual and of the group' (De Vaux [1961] 1973:21). At a later stage in the history of Israel, the term go'el attained a religious usage. Yahweh, an avenger of the oppressed and redeemer of his people, is called a go'el (see De Vaux [1961] 1973:22 for OT references). See also Brooke (1976:23-27) and Smalley (1989:36) for more background usage in the Old Testament. See Strecker (1996:37) and also Schnackenburg (1992:86) for the use of 'helper' in Mandean Texts.

64. Strecker (1996:39, n. 17) argues that the idea of propitiation cannot be excluded in this context because 'it accords with the preceding argumentation', in particular the reference to the blood of Jesus (1:7) and purification (1:9).

65. Haas et al. (1994:35) translate ίλασµός as expiation. The New Revised Standard Version, Smalley (1989:252) and Kruse (2000:73) translate it as 'atoning sacrifice'.

66. In the context of 1 John, the association of the title 'Christ' with Jesus' death and forgiveness probably determines the nature of the role of 'Christ'. No other Christ other than this Jesus, who is incarnate God (1:1), the One who reveals eternal life to a spiritually dead world of human beings (1:1-3), Son of God (1:3), whose death cleanses from every sin (1:7), is the very One who is the Helper of Christians (Akin 2001:80).

67. See Bigalke (2013) in his doctoral thesis 'The meaning of hilasmos in the First Epistle of 1 John 2:2 (cf. 4:10)' for a thorough discussion on the meaning of ίλασµός.

68. The sacrifice of Jesus Christ in shedding his blood, both as the victim and the high priest, is indicated by the use of the basic verb ίλάσκοµαι in Hebrews 2:17: 'To make reconciliation for the sins of the people', which means to pay the necessary price for the expiation and removal of the sins of the people. This was parallel to that which the high priest did, but it was perfect and a far better sacrifice in that it was permanent and unrestricted. Τό ίλαστήριον, the mercy seat (Heb 9:5), was the lid or cover of the Ark of the Covenant on which the high priest sprinkled the blood of an expiatory victim (Ex 25:17-22; Lv 16:11, 13-15). The use of all these words must, therefore, be connected with the blood of Christ shed on the cross. The cross was the place of expiation (the mercy seat), and Christ was the sacrifice whose blood (his sacrificial death) was sprinkled on it (Zodhiates 2000:I, 2434).

69. See also Romans 3:25 (ίλαστήριον) and Hebrews 2:17 (ίλάσκεσθαι) for earlier statements of Jesus' death.

70. For Danker (2000:1007), the indefinite adjective is 'a reference to someone or something indefinite, anyone, anything; someone, something; many a one/thing, a certain one'. For Louw and Nida (1996:813, 92.12), it is 'a reference to someone or something indefinite, spoken or written about - "someone, something, anyone, a, anything".' Friberg, Friberg and Miller (2000:381) understands it as an 'enclitic indefinite pronoun; (1) as a substantive; (a) used indefinitely someone, something; any(one), anything; somebody, anybody'.

71. See also the verb πεπληρωµένη, 1:4.

72. For Smalley (1989:32) it 'refers the confession of sin in detail'.

73. Balz and Schneider (1990:508) interprets it as 'whole, complete - functions as an indication of totality'. For Danker (2000:704) it refers to (1) 'pertaining to being complete in extent, whole, entire, complete', (2) 'pertaining to a degree of completeness, wholly, completely' or (3) 'everything that exists, everything'.

74. Quoted by Brown (2008:46).