Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

HTS Theological Studies

versión On-line ISSN 2072-8050

versión impresa ISSN 0259-9422

Herv. teol. stud. vol.70 no.1 Pretoria ene. 2014

ORIGINAL RESEARCH: FOUNDATION SUBJECTS - OLD AND NEW TESTAMENT STUDIES

Is rewritten Bible/Scripture the solution to the Synoptic Problem?

Gert J. Malan

Reformed Theological College, University of Pretoria, South Africa

ABSTRACT

New Testament scholars have for centuries posited different solutions to the Synoptic Problem. Recently a new solution was proposed. Mogens Muller applies Geza Vermes's term rewritten Bible to the canonical gospels. Accepting Markan priority, he views Matthew as rewritten Mark, Luke as rewritten Matthew, and John as additional source. This article examines Muller's hypothesis by first investigating the history of the controversial term rewritten Bible/ Scripture and its recent application to the New Testament Gospels. Muller's hypothesis is then compared to other solutions to the Synoptic Problem, such as the Augustine, Griesbach, and Farrer-Goulder Hypotheses. The Two Document Hypothesis is discussed and Muller's 2nd century Luke theory is compared to Burton Mack's almost similar stance and tested with the argument of synoptic intertextuality in view of the possible but improbable early second century date for Matthew. Lastly, the relationship between the synoptic Gospels is viewed in terms of literary intertextuality. Muller suggests proclamation as motivation for the Gospels' deliberate intertextual character. This notion is combined with the concept of intertextuality to suggest a more suitable explanation for the relationship between die Gospels, namely intertextual kerugma. This broad concept includes any form of intertextuality in terms of text and context regarding the author and readers. It suitably replaces rewritten Bible, both in reference to genre and textual (exegetical) strategy.

Rewritten Bible

The meaning of the concept rewritten Bible has evolved substantially since its inception. Let us first consider the origins of the concept and for which purpose it was created. Vermes (1961:95) coined the term rewritten Bible without actually formulating an analytical definition of the term (Petersen 2007:289-290). The closest Vermes (1961:95) comes to defining the term is by describing rewritten Bible as an 'exegetical process' by which a midrashist, 'in order to anticipate questions, and to solve problems in advance' inserted 'haggadic development into the biblical narrative'.

The context for this formulation was Vermes's conclusion that Sefer ha-Yashar, a late medieval text, preserved and developed traditions that emanated in the pre-Tannaitic period. Vermes cited literary antecedents for this exegetical technique as for instance the Palestinian Targumim and Josephus's Antiquitates. He compares it to biblical midrash in that frequent reading of and meditation on Scripture with the intention of interpreting, expounding and supplementing its stories and resolving its textual, contextual and doctrinal difficulties, results in a rewritten Bible, namely a fuller, smoother and doctrinally more advanced form of the narrative (Vermes 1986:308). In this sense, Vermes initially coined the term as a textual strategy.

Later he somewhat ambiguously used the term not only as textual strategy (a type of exegesis), but also as denoting a definite genre to which writings such as Antiquitates, Jubilees and Genesis Apocryphon belong (Vermes 1989:185-188). One can deduce that Vermes intended to categorise texts using rewritten Bible as textual strategy to form a genre with this exegetical strategy as the main characteristic.

The lack of definition and subsequent ambiguity led Alexander (1988) to identify the principle characteristics of the genre rewritten Bible:

• Rewritten Bible texts are narratives. They follow a sequential, chronological order. They are not treatises.

• They are, on the face of it, free-standing compositions which replicate the form of the biblical books on which they are based. Their constant use of Scripture is seamlessly integrated in the retelling of the biblical story, unlike rabbinical midrashim, which highlights words of Scripture in the body of texts.

• Rewritten Bible texts were not intended to replace or supersede the original texts.

• A substantial portion of the Bible is covered by rewritten Bible texts.

• They follow the biblical texts serially, in proper order, but are highly selective of what they represent. Some parts are reproduced literally, whilst others are omitted, abbreviated or expanded.

• The intention of the rewritten texts is to produce interpretative reading of Scripture.

• The narrative form restricts them to impose only a single interpretation of the original. The original can only be treated as monovalent.

• Another restriction of the narrative form is that clear exegetical reasoning is precluded.

• Rewritten Bible texts make use of non-biblical tradition and draw on non-biblical sources, whether oral or written. Though concerned with biblical figures, they often use legendary material with little relationship to the biblical text (pp. 99-121).

Alexander (1988:99-100) based his deductions on the study of only four documents normally included in the genre, namely Jubilees, Genesis Apocryphon, the Liber Antiquitatem Biblicarum and Josephus's Antiquitates. This may be viewed as somewhat of a restriction, making his selection of documents the standard for the term he tries to define. This brings circularity to his argument (Petersen 2007:290, n. 12). His reasoning seems to be based on Vermes's point of view in the hope of moving in the direction of a definition of the genre (Alexander 1988:117). In literary terms, both as genre and as textual strategy, rewritten Bible can be described as a form of intertextuality (Grivel 1978:69).

One finds Bernstein's (2005:169-196) reasoning similar to Vermes's, but with additional focus. He also uses rewritten Bible as a narrow understanding of a distinct genre. Bernstein further distinguishes rewritten Bible texts from writings that represent alternate versions of biblical texts, or revised editions on the one hand, and from writings that use a particular biblical motif, a specific biblical passage, or a certain narrative character as a springboard for developing an entirely new composition. Bernstein calls these texts with a more tenuous and much freer relationship to the Bible parabiblical rather than rewritten Bible (Bernstein 2005:193). Thus Bernstein confines the concept rewritten Bible only to the non-targumic writings of Vermes's initial classification. Like Vermes, Bernstein understands rewritten Bible to denote texts with a comprehensive or broad scope in the process of the rewriting of narrative and legal material with commentary woven into the fabric implicitly. It is not merely a biblical text with some superimposed exegesis (Bernstein 2005:195-196). Like Vermes, Alexander and Bernstein does not apply the term to biblical texts.

In summary, the concept rewritten Bible evolved from a type of exegesis to a genre (Jewish Second Temple commentaries on narrative First Testament texts) without the authority of canonical texts.

Rewritten Scripture

Various objections and criticisms followed the initial understanding and application of the term rewritten Bible. Some scholars studying literature from the same period have found the term rewritten Bible problematic, and reformulated the term as rewritten Scripture. Some, like Campbell (2003:4850), Chiesa (1998:131-151) and Crawford (2000:173-195) view the term rewritten Bible anachronistic and too narrow. Petersen (2007:287) substitutes Bible with Scripture. He defines Scripture as any writing or book that is attributed a particular authoritative status, especially in the context of writings of a sacred or religious nature. Scripture, as Petersen applies the term, does not refer to a canonically homogeneous collection of writings that have been completely demarcated or formally closed, nor of which the wording has ultimately been laid down. He intends to capture the essence of Vermes's concept whilst making it more fluid, so that the plurality of different text forms and the dynamic processes that eventually led to the formation of various canons are taken into account.

Rewritten Scripture seems to result in a noteworthy broadening of the scope of meaning that Vermes initially intended, with specific gains and losses. The way is paved for the reciprocal relationship that exists between authoritative texts and the writings they occasion, to be acknowledged. Importantly, it specifically highlights the way authoritative writings are used as matrices for the creation of authoritatively derivative texts that by virtue of being rewritings contribute to the authoritative elevation of their antecedents (Petersen 2007:287), whilst on the other hand the rewritings sun themselves in the authoritative light of their predecessors (Brooke 2005:85-104). This does not imply that the literary relationship as such accounts for the creation of new writings, because they were composed with other aims in mind (Petersen 2007:299).

When this broadened version of the concept is used, the term rewritten Scripture is also applied to biblical documents. Deuteronomy is an example of rewritten law texts in Exodus, Leviticus and Numbers. It became Scripture and functioned as a second collection of laws causing new instances of rewritten Scripture. This shows that the relationship between written and rewritten Scripture is fuzzy, since the transitions between them are fluid by nature (Petersen 2007:300). This example also shows that rewritten Scripture texts could gain authority from their written antecedents to such an extent that rewritten Scripture could become authoritative Scripture itself.

It is doubtful that replacing rewritten Bible with rewritten Scripture is at all helpful. Rewritten Scripture (with a capital S), implies Bible, even though Petersen has defined its scope much broader. Without the capital S, scripture could signify any (religious) written document, as Petersen (2007:287) suggests, but then Vermes's (1989) idea of using the term to denote texts which have rewritten biblical documents is lost. The problem is not solved, but complicated by substituting Bible with Scripture.

Furthermore, both terms fail to take account of the fact that scribes could produce material in their own name or pseudepigraphically, and readers could interpret books as either recent literature or antique scripture. Campbell (2005:49) correctly underlines the fact that, from a late Second Temple perspective, there was no genre incorporating all the works generally denoted rewritten Bible or rewritten Scripture. He refrains from replacing rewritten Bible or Scripture with a more suitable term. Although he considers parabiblical and parascriptural, he rejects both, as they imply the withholding of canonical status from the compositions concerned (Campbell 2005:51). He opts for individualised terminology instead of generic terms, and suggests using the names given to Qumran texts as a basis for a new name for each composition (Campbell 2005:55-59). However, the need for a generic term denoting the reciprocal relationship between the initial compositions and the rewritten ones remains. This questions the usefulness of Campbell's individualised solutions, even though his critique of the terms rewritten Bible and rewritten Scripture is justified.

A possible solution could be to utilise the concept not as a specific genre, but as textual strategy, as Vermes initially intended. Rewritten Bible/Scripture then signifies a kind of activity, a process rather than a genre (Harrington 1986:239). The weakness in this strategy is that the question of how to denote texts rewriting biblical texts is left unanswered.

Another possible solution could be to acknowledge that the meaning of rewritten Bible/Scripture is not situated at the emic, but at the etic level. In this way, rewritten Bible/Scripture could be retained as denoting a genre, thus attending to the legitimate concern of the taxonomic focus on the intertextuality between scriptural works and rewritten scriptural literature (Petersen 2007:305). Whether this is the most suitable solution remains to be seen, as the problems surrounding the term rewritten Bible/Scripture is compounded by its application to the Second Testament documents.

Rewritten Bible/Scripture applied to Second Testament documents

Mogens Muller (2013:231-242) introduced the concept of rewritten Bible to the documents of the Second Testament, thus explaining the relation between the Gospels and arguing that Luke was the latest gospel. He uses the term loosely, both as genre and as interpretative strategy, thus not entering the rewritten Bible/Scripture debate on genre versus literary strategy. Muller advances a theory of Markan priority, and views the other canonical Gospels as rewritten Bible, with Luke the latest, dating between the first and fourth decade of the 2nd century CE. According to this theory, Luke used the other Gospels as sources and this intertextuality, as well as the gospel genre, is described as rewritten Bible. According to Muller (2013:234), proponents of the Two Document Hypothesis deliberately dated Luke as Matthew's contemporary so that it could not be assumed that Matthew was amongst Luke's sources (Muller 2013:234). According to Muller, the need for Q and the Two Source Hypothesis loses probability as the interval between Luke and Matthew becomes 5-10 years, or even more so when it is 30-40 years (2013:236). These arguments will be tested in the following discussions.

The Synoptic Poblem and proposed solutions

The discussion about the possible relationships (intertextuality) between the (canonical) Gospels must be viewed within the context of the Synoptic Problem: how is it that Matthew, Mark and Luke tell much the same story in much the same order, whereas John has a completely different procedure (Robinson, Hoffmann & Kloppenborg 2003:11)?

Several solutions (hypotheses) have been proposed. Whilst they vary in complexity, it is important to note that these solutions are simplifications of a process within which there are many uncertainties. To name but a few: We do not have the original versions, or the exact wording of any of the canonical Gospels. In the more than six thousand New Testament manuscriptural variants one cannot find two documents with identical wording. It is therefore highly unlikely that we can accurately reconstruct the actual compositional processes of the Gospels. Harmonisation of manuscripts by the earliest copyists may have obscured the patterns that would allow a clearer solution. However, simple explanations are more desirable than complex solutions (Kloppenborg Verbin 2000:51-53).

More simple and plausible solutions to the Synoptic Problem include the Augustine, Griesbach and Farrer-Goulder Hypotheses. They have two features in common: Firstly, each has Mark in a medial position: (1) as a conflation of Matthew and Luke (Griesbach or Two Gospel Hypothesis); (2) as the common source of Matthew and Luke (Farrer-Goulder, in Foster 2003:314-318); or (3) as the link between Matthew as the 'oldest' gospel and Luke as the 'latest' (Augustine Hypothesis). Secondly, each posits a direct dependence of. Luke upon Matthew (Kloppenborg Verbin 2000:38-39). It is this aspect which is shared by Muller's (2013) hypothesis, although Muller accepts Markan priority. These hypotheses can be illustrated as in Figure 1 - Figure 4.

Ironically and most importantly, even with Markan priority, Muller's hypothesis shares several shortcomings with the hypotheses which place Mark in a median position, namely that they cannot sufficiently answer the following questions:

1. Why, in pericopae where both Matthew and Mark were present, did Luke always choose the Markan and never the Matthean order?

2. Why did Luke overwhelmingly prefer Markan wording even though Matthew offered something different, often in better Greek?

3. Why did Luke rather aggressively dislocate sayings from the context in which he found them in Matthew, often transporting them to contexts in which their function and significance is far less clear than it was in Matthew? (Kloppenborg Verbin 2000:39).

The terminus a quo [point of origin] for the articulation of the Two Document Hypothesis is C.H. Weisse (1838) who first formulated a Synoptic theory with Markan priority and a sayings source utilised by Matthew and Luke (Derrenbacker & Kloppenborg Verbin 2001:59). He follows Lachmann, the first scholar (1835) to postulate Markan priority (Kloppenborg Verbin 2000:295-297). H.J. Holtzmann later used the Two Documents Theory in a descriptive and definitive way in reply to D.F. Strauss's picture of Jesus as speculative personification of humankind's divinity. Holtzmann in this way tried to show that a historical question can be answered by historical criticism. Other exponents, such as Harnack, Wellhausen, Bultmann, Dibelius, Schmithals, Todt, Bornkamm, J.M. Robinson and H. Koester followed, each with their own nuances (Foster 2003:313; Luhrmann 1989:51-58). These nuances are not discussed, as they are not pertinent to this study.

The Two Document Hypothesis proposes that the Gospels of Matthew and Luke independently used Mark as a source, and since they share about 235 verses that they did not get from Mark, the Two Document Hypothesis also maintains that they had independent access to a second source consisting mainly of sayings of Jesus, namely the Sayings Gospel or 'Q' (Kloppenborg 2000:11-31). Q comprises all the material Matthew and Luke have in common, independently, of their second source, Mark (Luhrmann 1989:58). Q can be reconstructed from Matthew and Luke, since it is therefore within both.

Yet when viewed on its own, it exhibits architectural features and theological emphases that are not at all prominent in the two successor documents. Q shows itself to be non-Matthean in important respects and organised along lines that are not developed (or even grasped) by Matthew or Luke. This situation is no different from that of Mark: although Matthew and Luke used Mark, their respective recasting of Mark (the addition of infancy accounts, speech materials and appearance stories) altered and obscured some of the basic dynamics of their source. Mark and Q each have their own stylistic and theological integrity as one should expect of two documents existing prior to their incorporation by Matthew and Luke (Derrenbacker & Kloppenborg Verbin 2001:76).

Three sets of data are pertinent: agreements in wording and sequence, patterns of agreements in the triple tradition (Matthew, Mark and Luke agree, meaning Mark was the source for both Matthew and Luke), and patterns of agreement in the double tradition (Matthew and Luke agree, meaning Q was the source for both Matthew and Luke). The double tradition (Q as source for both) exhibits two important and seemingly contradictory features. Firstly, whilst there is often a high degree of verbal agreement between Matthew and Luke within these conforming (double tradition) sections, there is practically no agreement in the placement of these sayings relative to Mark. There is thus little to suggest that Luke was influenced by Matthew's placement of the double tradition (Q) and vice versa (contra Muller's hypothesis). Secondly, if one does not measure the sequential agreement of these concurring Matthew-Luke (double tradition) materials relative to Mark, but relative to each other, they account for almost one-half of the word count and are in the same relative order. That is, in spite of the fact that Matthew and Luke place the double tradition materials differently relative to Mark, they nonetheless agree in using many of the sayings and stories in the same order relative to each other. This implies that, even if Matthew and Luke were not in direct contact with one another, Q has influenced them in the overall order of the double tradition. The level of agreement between Matthew and Luke in the double tradition indicates some sort of relationship, directly or indirectly, but without involving Mark or Markan material. The Two Document Hypothesis accounts both for Matthew and Luke's basic agreement in the relative sequence in the double tradition (independently of Mark) and for the nearly complete disagreement in the way in which these materials are combined with the Markan framework and with Markan stories and sayings (Kloppenborg Verbin 2000:11-31).

Schematically, the Two Document Hypothesis, can be represented as follows, showing that Matthew and Luke are independently connected to Mark and Q, but not to each other (see Figure 5).

This furthermore accounts for the fact that Matthew and Luke tend not to agree sequentially against Mark, because both have used Mark independently. Hence, they sometimes take over from Mark the same wording and sequence (resulting in the triple agreements); sometimes Matthew reproduces Mark whilst Luke chooses another order or wording; sometimes the reverse. But when Matthew and Luke both alter Mark, they rarely alter Mark's wording in the same way and never agree in sequence against Mark. Even though both Matthew and Luke rearranged Mark, they transpose different Markan pericopae and the only pericope which both transpose (Mk 3:13-19) is not transposed in the same way. This illustrates that Matthew and Luke used Mark independently, and it is sufficiently accounted for by the Two Document Hypothesis. Likewise, this accounts for Matthew and Luke independently using a non-Markan source of Jesus' sayings (Q). Sometimes they copied Q precisely, resulting in verbatim agreement between Matthew and Luke. Since none of them had seen the other's work, they could not have been expected to agree in placing the non-Markan material relative to the Markan material. Nevertheless, since the Q material had a fixed order, both Matthew and Luke were influenced by that order and hence agree in many instances in relative sequence, even if they have fused it differently with Mark (Kloppenborg Verbin 2000:29-36).

There is a set of so-called 'minor agreements' between Matthew and Luke against Mark that seem to violate the principle that Matthew and Luke do not agree in wording against Mark (Foster 2003:324-326; Kloppenborg Verbin 2000:32-36). Some of these agreements are common omissions of Markan pericopae, phrases or words; some are common additions to or elaborations of Mark (but normally not the same addition or elaboration); some are agreements against Mark in word order or inflectional form; and some are more substantial verbal agreements over against Mark. In most cases, common omissions do not require the supposition of collaboration between Matthew and Luke but arise instead from similar responses to the text in Mark. The omission by both of two Markan pericopae can likewise be explained from the theology of each Gospel. Both omit Mark 3:20-21 (where Jesus' kin thought him insane) and Mark 8:22-26 (two healing gestures required for complete restoration). The first casts Jesus' family in a bad light and contrasts with the glowingly positive portrayals in the widely divergent infancy accounts. Mark 8:22-26 is part of a long block of Markan material omitted by Luke, whereas Matthew only omitted Mark 8:22-26. Seemingly identical editing of Mark by Matthew and Luke does not necessarily imply literary dependence. It arises naturally from the evangelists' respective theologies of Jesus' family and his capacity for wondrous deeds. Other agreements arise from both writers editing flawed Markan Greek or Markan double expressions identically or differently. Other minor agreements can be explained by coincidental redaction, influence of oral tradition, textual corruption, or the use of an earlier or second recension of Mark (see Ennulat 1994:123-12; Koester 1983:48; Neirynck 1991:26-27; Streeter 1924:313).

The Two Document Hypothesis offers the most economical and plausible accounting of the form and content of the synoptic Gospels. It continues to be by far the most widely accepted solution to the Synoptic Problem (Kloppenborg Verbin 2000:11). It solves more problems than do other hypotheses and leaves fewer questions unanswered (Luhrmann 1989:61).

Second century Matthew?

Accepting the possibility of Luke being the youngest canonical Gospel using the other three as sources, Muller's idea that Q and the Two Source Hypothesis would be obsolete in such a scenario, should be tested. Muller's (2013:234-236) main argument is that an interval of several decades between Matthew and Luke would make the need for Q and the Two Documents Hypothesis improbable.

Müller (2013) states that most scholars subscribing to the Two Sources theory and the existence of Q argues for a short interval between Luke and Matthew. A contradiction to this standpoint can be found in the work of Mack (1995:43-183), who, like Muller, views Luke as the latest canonical Gospel dating around 120 CE. His theory is that Luke, whilst not knowing Matthew, merged Mark and Q and added some material of his own.

Mack (1995:169) argues that Luke is thus evidence that a copy of Q was still in circulation in the 2nd century. He dates the Gospel of Matthew close to 90 CE, resulting in an interval of about 30 years between Matthew and Luke. Matthew is also described as interweaving teachings of Jesus from Q with Mark's story, editing Mark's story a few times and discarding three or four stories he could not use (Mack 1995:161-162). Mack's reasoning shows that Q and the Two Source Hypothesis need not be abandoned in view of a possible interval of several decades between Matthew and Luke.

Both Mack and Muller therefore argue in favour of Luke as the latest canonical Gospel. Mack however argues from the perspective of the Two Source Hypothesis, with Mark and Q as Luke's main sources, whilst Muller (2013:235) views Luke as rewritten Matthew utilising Matthew (which he views as a rewritten Mark) as main source, alongside John's Gospel. Both Muller and Mack focus on Luke's sources, but Muller suggests a chronological rewriting taking place: firstly Matthew rewriting Mark and then Luke rewriting Matthew with John only as source.

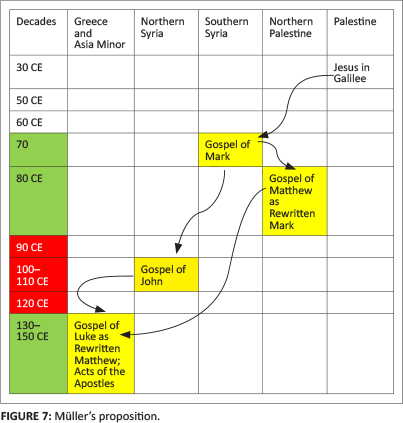

Mack (1995:311) illustrates his idea by means of a scheme showing the geographic area of origin as well as the historical time of origin of the Second Testament books and the oral and written traditions from which they evolved. Both can be viewed in a simplified and abbreviated form of Mack's scheme as illustrated in Figures 6 and Figure 7.

Although Muller does not use geographical locations when arguing the dates of origin, his suggestions can be superimposed on Mack's scheme in order to better compare them with each other.

The following observations can be made:

1. Mark and Matthew are both dated a decade younger by Mack than Muller did. The interval between them is the same as Muller's position has it.

2. In Muller's view, John's Gospel is not rewritten, but serves as a source for Luke.

3. Mack does not view John as a source for Luke, but accepts that John used Mark as a source.

4. Mack dates Luke a decade earlier than Muller. With Mack's earlier dating for Matthew, the interval between Luke and Matthew (marked red in the decades column) is 30 years, twenty less than with Muller, but still substantial.

5. Muller denies the existence of Q, viewing Matthew as rewritten Mark and Luke as rewritten Matthew and John a source for Luke.

Conclusion:

• Both scenarios suggest a long interval (3-5 decades) between Luke and Matthew.

• The term rewritten Bible/Scripture can be viewed as merely an alternative for using a previous or existing (gospel) text as a source for a new one.

• Viewed in this way, rewritten Bible has as only 'advantage' the denying of the existence of Q, (although Mack's almost similar dating within the Two Document Hypothesis rejects this).

• The decades long interval between Matthew and Luke seems improbable within the Two Document Hypothesis and should be addressed.

We now return to Muller's objection (2013) that it is improbable that Luke did not know Matthew when there is an interval of a few decades between their dates of origin. It must be reiterated that Mack does not find this problematic or sees that it renders the Two Source Hypothesis obsolete.

It must further be noted that the Two Source Hypothesis was formulated on the ground of the obvious intertextuality between the synoptic Gospels and not primarily on their dates of origin. Nevertheless, let us consider the possibility of a later date for Matthew. Lastly it is important to accept that it is very difficult to determine the possible dates of origin of the Gospels. It is a very complex theoretical exercise in which several arguments are weighed before conclusions can be drawn, which cannot be considered as definite proof.

Helmut Koester's (1957) remarks on the possible date of origin for Matthew's Gospel underscore this. The terminus ante quem [latest possible date] for Matthew's Gospel is generally viewed as circa 100 CE, partly for having been quoted by or deemed as source for the Ignatian letters (Gundry 1982:599; Strecker 1962:35). Some scholars have cited numerous difficulties with this assumption (Bauer 1972:211; Trevett 1984:60-64). Koester (1957:24) has challenged the prevailing tendency to refer to supposed quotations and to then conclude that Ignatius 'knew' the Gospels of Matthew, Luke, John and the Gospel of the Hebrews. Koester's contention is that Ignatius knew none of the written Gospels. The parallels so often adduced were perhaps to be traced to sources other than our present Gospels, which were neither the only nor the earliest sources available (Koester 1957:60). Furthermore, the traditional early date for the Ignatian correspondence (107-108 CE) has been challenged by several scholars (see Trevett 1984:65). If these strong objections lodged against the citing of Matthew in the Ignatian letters are to be concurred with, it also raises doubts about other documents' previously inferred knowledge of Matthew, like the Didache. Their so-called citing of Matthew may also have originated from other sources than Matthew.

This is confirmed by Koester (1994:293-297) in his critical notes on 'Gospel or oral tradition?' Koester maintains that the new Christian communities were initially organised by the continuation of inherited oral Jewish teachings and sayings of Jesus. These materials were composed at an early time in the form of small catechisms, which may occasionally have been committed to writing, and served as instructional materials before initiation through baptism. Sayings of Jesus were considered life-giving and saving words, and thus authoritative. Their transmission and interpretation were therefore constitutive. But even here, the oral transmission of such sayings seemed to have been sufficient. There was no need for the production of authoritative written documents. Founding apostles used personal visits in order to nurture the newly created communities. Written communications (letters), as is evident in the Pauline mission, were needed only when their personal presence was made impossible by external circumstances. The only written authority to which one would appeal was the scriptures of Israel, the Law and the Prophets. Catechisms were written down early in order to standardise the instruction and could be based on traditional Jewish materials with sayings of Jesus inserted:

The most extensive document of this type, which functioned also as a church order, is the 'Sermon on the Mount.' The Gospel of Matthew continues this tradition, and this Gospel is essentially a church order. This may explain why so many references to sayings of Jesus, which appear very early in Christian literature (see Romans 12; James), look like quotations from the Sermon on the Mount and the Gospel of Matthew; it also accounts for the later popularity of this particular Gospel. (Koester 1994:294)

On this ground it can be argued that early Christian writings such as 1 Clement, Barnabas and the Letters of Ignatius of Antioch used such catechisms and oral material rather than the written Gospels, especially the Gospel of Matthew. When pieces of tradition are quoted and used in early Christian authors, their function in the life of the community is usually maintained. Indeed, it may not even be necessary to refer to them as traditions related to Jesus. This is most clearly the case in Paul's allusions to sayings of Jesus in Romans 12-14, in 1 Peter, and in James. As far as writings such as 1 Clement, Barnabas, and the letters of Ignatius are concerned, the use of sayings of Jesus and allusions to them would seem to be natural continuations of this practice, whether or not Jesus is explicitly mentioned as an authority. Sayings of Jesus were known because they had been established as parts of a Christian catechism, and the passion narrative was known because it was embedded in the Christian liturgy (Koester 1994:295-297).

The above argument is in direct opposition to the argument underpinning the early dates of the composition of Matthew's Gospel. When it is presumed that the tradition of sayings began with the written Gospels, and especially the canonical Gospels, an early date of their composition is usually assumed. This early date is then 'confirmed' by the discovery of 'quotations', primarily from the Sermon on the Mount and other chapters of Matthew. Thus Matthew seemingly emerges as the most frequently used gospel writing (Koester 1994:295-297). In this way Koester's argument is a serious challenge to the idea of an early date of composition for Matthew's Gospel. To this should be added that the history of the written gospels is more complex; their texts were not stable during the first 100 years of their transmission (Koester 1994:297).

In addition to this argument we should note the difference in opinion about the relationship between the Judean religion and Matthew's readers. The engagement of Matthew with Judaism and Old Israel can be viewed as taking place either intra muros [as dialogue within Judaism] or extra muros [apologeticly directed at the synagogue from a church that was already outside it] (see Van Aarde 1994:252). In this regard, the promulgation of the Birkat ha-Minim [blessing against heretics] late in the 1st century (85-95 CE), plays a significant role. Some scholars, such as Katz (1984) and Finkel (1981) suggest that the break between Judaism and Christianity, however, may not have been instantly. There is strong evidence that the term notzrim was not originally part of the Birkat ha-Minim and was added much later (c. 175-325 CE; see Katz 1984:66). Katz (1984:76) argues that even the Birkat ha-Minim did not signal any decisive break between Jews and Jewish Christians and shows that the total separation eventually occurred during the Bar Kochba revolt (135 CE). Finkel's (1981:241-242) research shows that only in the time of Bar Kochba (132-135 CE) the Jewish Christians were persecuted by the Jews for not joining the Jewish forces in the revolt. The objects of the rebel leader's wrath were however his own countrymen who refused to join the rebellion, not non-Jewish Christians:

Following the death of Bar Kochba, the destruction of Judea, and the Hadrianic religious persecutions, faith in the Messiah became a burning issue. The parting of the ways can be attributed to the above catastrophe, as reflected in Justin's works (Apology I, 31, and Dialogue 1, 16) and the Epistle of Barnabas (16:4). Jews rejected all who professed faith in a dead Messiah, whereas Christians upheld their faith in Jesus, pointing to the fulfilment of his prophecy regarding the destruction of Judea and the appearance of the false Messiah. At this time the Jewish Christian church of Jerusalem ceased to exist. (Eusebius, Church History 4-6; in Finkel 1981:242-243).

Van Aarde (2008:163-182) agrees that, 'although Matthew warns against the teachings of the Pharisees (Mt 16:5), he does not advocate a total break with the Second Temple customs'. Katz's (1984) argument is supported by Cohen (1984:27-53), who concluded that the aim of the rabbi's at Yavneh was the cessation of sectarianism by creating a tolerant society which encouraged even vigorous debate amongst members of its fold. The aim was not the excommunication of various sects. Runesson (2008:102-104, 109-111, 126-128), from a social- scientific viewpoint, argues that the religion represented in Matthew's Gospel is that of an (initially Pharisaic) Jewish group located within the Jewish religious system. The pattern of religion in Matthew's Gospel, analysed by focusing on one of the fundamental structures of patterns of religion - the theme of divine judgement - indicates a Jewish understanding of divine retribution, punishment, and reward, as opposed to Greco-Roman ideas about judgement. Furthermore, the text accepts most of the practices central to Jewish identity. The existence of a dominant formative Jewish group (like the Pharisees) soon after the destruction of the Temple is questionable and the origins of rabbinic Judaism seem to be more complex than previously thought. The assumption of an immediate rise to power of formative Judaism post 70 CE is problematic. An early 2nd century date for the interaction between Matthew and such a group seems more plausible than postulating a local group dominating in the Matthean region, as Saldarini (1992:663-664) suggests.

Van Aarde (1994:255) concurs with Schmithals (1987:375-378) that the break between Jews and Christians was not yet accomplished when Matthew's Gospel was written (see also Foster 2003:315). He also quotes Schmithals (1985:337), who maintains that the Matthean community lived in circumstances of persecution and distress cast upon them by the synagogue. He concludes that Matthew experienced the process of separation with disappointment, but nonetheless views Jewish Christians as still within the Jewish fold (Van Aarde 1994:255-256). This evidence seems to suggest that Matthew could have written his Gospel closer to the Bar Kochba revolt and the final break than shortly after the Birkat ha-Minim was promulgated.

These arguments should however be weighed against Paul's references to Christians persecuted by die Judean religious community. Even in Paul's earliest letter (1 Th 2:14-16), written around 51 CE, he refers to the Thessalonians' suffering under their countrymen just as the Judean Christians suffered under their countrymen and includes himself as being persecuted by them (1 Th 2:15). This suggests that the Judeans already regarded the Christian Judeans as outside the fold (extra muros). This argument is confirmed by Paul's reference to his earlier service as prominent member of the Judean religious community, as mercilessly persecuting the church and trying to destroy it (Gl 1:13). Three years after his conversion, Paul promised Peter and the other apostles to help take care for the needy Judean Christians. This suggests that the Judean religious community regarded the Judean Christians as outsiders whom they need not take care of (see also 1 Cor 16:1-3; 2 Cor 8 and 9). It also seems that Paul was not regarded as intra muros when he was five times given the thirty nine lashes (2 Cor. 11:24). Lastly, Paul's wish that the Judean religious community would convert to faith in Christ (Rm 9-11) can be interpreted as that he already regarded them and the Christians as two different folds, thus an extra muros situation. Our conclusion in this regard must be that Paul argued and experienced that Judean Christians were at a very early stage already pushed out of the Judean religious community, especially in the Judean heartland. Weighed against this evidence, it seems unlikely that the parting of ways between the Judean religion and Judean Christians only happened with the Bar Kochba revolt.

An early 2nd century date for Matthew (perhaps 100-135 CE) is not impossible, but highly improbable. Such a scenario would suggest Matthew and Luke wrote their Gospels at much the same time, thus being unable to utilise each other's documents. However, even in this unlikely event, the Two Document Hypothesis is not dependent on such a scenario, but is motivated by the specific intertextuality between the synoptic Gospels as outlined above. The probable long period between Matthew and Luke (decades) should not deter us from accepting the explanatory value of the Two Document Hypothesis, as it argues from the intertextuality between the Synoptics and not the date of origin, accepting only Markan and Q priority for Matthew and Luke. The focus should be on their intertextuality.

Intertextual kerugma

We have already shown the complex intertextual relationship between the Synoptics. Let us consider for a moment whether this literary term could help us describe the Synoptics' relationship in a more sufficient way than rewritten Bible/ Scripture.

We can use this literary term, because the synoptic Gospels are literary works and the Synoptic Problem suggests a high degree of intertextuality. Intertextuality refers to the footprints (traces) of other texts in a text (Malan 1985:20), the possible relationships with other literary texts or with a culture in general (Van Luxemburg, Bal & Westeijn 1983:276) or a certain literary context or tradition as large intertext (Malan 1985:20). Viewed in this way, a text does not tell its story in isolation, but in dialogue with other texts (Malan 1985:49; Ohlhoff 1985:49). Intertextuality becomes a measure of the degree in which a text is integrated in a society and of the variety of socially determined language forms that can be identified. As such, the text becomes a specific way in which the history of a society at some point in time is told. Intertextuality is thus a concept of literary and social space, as it moves between the literary and the social realm (Hoek 1978:69). It becomes a designation of its participation in the discursive space of culture (Culler [1981] 2001:103), the textual form in which culture, history and society engrave themselves in texts (Van Aarde 2008:163-182, referring to the dictums of Julia Kristeva [1969] and Roland Barthes [1985]).

Müller (2013) understands the gospels as literary works (fiction) and views the tertium comparationis [third part of comparison] between original text and the rewritten one as the faith or conviction aimed at their readers or listeners.

To achieve that goal, it seemingly was legitimate to invent persons and events and to construct speeches and teachings (for instance parables). In short - these writings are primarily fiction. This sets us free from always looking for hypothetical sources behind the material special to Lucan writings. (p. 231)

It seems that Muller (2013) tries to escape intertextuality in the sense of sources behind the Lukan writings, whilst proposing the hypothesis of rewritten Scripture as substitute for the inescapable fact of intertextuality between the synoptic Gospels. Although this is impossible, his observation about the aim of the Gospel writers should not be overlooked or denied. The gospel authors aimed their faith or conviction to their readers, thus denoting the gospels' nature as kerugmatic texts proclaiming faith in Jesus Christ, each from a certain context and point of view.

In view of the problematic nature of the terms rewritten Bible/Scripture, it seems much more preferable to explain the relationship between the synoptic Gospels and between the Synoptics and the other (related) documents with the undisputable literary phenomenon of intertextuality. Importantly, the broader sense of the term, as referring to historical and cultural discourse, should not be forgotten, since it forms the hermeneutical context for understanding a text. For example, one may need to highlight the religious nature of the gospel texts by adding the descriptive term intertextual kerugma, emphasising the proclaiming nature of the gospel texts (or any other biblical or religious texts) as proclaiming texts. As such it denotes the motive for making use of other texts. Kerugma in its literal sense is plenipotentiary proclamation by authorised messengers (heralds). In the New Testament it is by nature a personal address questioning an individual's self-understanding, rendering it problematic and demanding a decision (Bultmann 1983:307). The term intertextual opens the full range of intertextual possibilities to denote different kinds of interrelationships between the gospels and other text, as well as the relevant socio-historical and cultural context. Intertextual indicates the flexibility of the relationship between the gospels and other texts and the historical context, whilst leaving the literary freedom of the authors intact. This intertextuality includes both First and Second Testament texts, as well as non-canonical Jewish and Christian texts, and other religious and non-religious texts. Intertextual kerugma allows the authors the freedom to utilise the different kerugmatic convictions whilst keeping own convictions in new social settings intact. Intertextual kerugma escapes the anachronism associated with rewritten Bible/Scripture and frees the exegete to explore the totality of intertextual possibilities in the Gospels.

Acknowledgements

Competing interests

The author declares that he has no financial or personal relationship(s) that may have inappropriately influenced him in writing this article.

References

Alexander, P., 1988, 'Retelling the Old Testament', in D.A. Carson & H.G.M. Williamson (eds.), It is written: Scripture citing Scripture: Essays in honour of Barnabas Linders, pp. 99-121, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511555152.009 [ Links ]

Bauer, W., 1972, Orthodoxy and heresy in earliest Christianity, SCM, London. [ Links ]

Bernstein, M., 2005, 'Rewritten Bible: A generic category which has outlived its usefulness?', Textus 22, 169-196. [ Links ]

Brooke, G.J., 2005, 'Between authority and canon: The significance of reworking the Bible for understanding the canonical process', in E.G. Chazon (ed.), Reworking the Bible: Apocryphal and related texts at Qumran, pp. 85-104, Brill, Leiden. (Studies on the Texts of the Desert of Judah 58). [ Links ]

Bultmann, R., 1983, Theology of the New Testament, vol. 1, 10th impression, SCM, London. [ Links ]

Campbell, J.G., 2003, '''Rewritten Bible" and "Parabiblical texts": A terminological and ideological critique', in New Directions in Qumranic Studies: Proceedings of the Bristol Colloquim on the Dead Sea Scrolls, 8-10 September 2003, pp. 43-68, Clark, London. [ Links ]

Chiesa, B., 1998, 'Biblical and parabibilcal texts from Qumran', Henoch 20, 131-51. [ Links ]

Cohen, S.J.D., 1984, 'The significance of Yavneh: Pharisees, rabbi's and the end of sectarianism', Hebrew Union College Annual 55, 27-53. [ Links ]

Crawford, S.W., 2000, 'The rewritten Bible at Qumran', in J.H. Charlesworth & N.R. Hills (eds.), The Bible and the Dead Sea Scrolls Volume One: The Hebrew Bible and Qumran, pp. 173-195 (pp. 176-177), Bibal Press, North Richland Hills, TX. [ Links ]

Culler, J., [1981] 2001, 'Presupposition and Intertextuality', in J. Culler, The persuit of signs: Semiotics, literatured deconstruction, augmented edn. with preface, pp. 100-118, Cornell University Press, Ithaka, NY. [ Links ]

Derrenbacker, R.A. (Jr) & Kloppenborg Verbin, J.S., 2001, 'Self-contradiction in the IQP? A reply to Michael Goulder', Journal for Biblical Literature 120(1), 57-76. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/3268593 [ Links ]

Ennulat, A., 1994, Die 'Minor agreements': Untersuchung zu einer offenen Frage des synoptische Problems, Mohr, Tubingen. (WUNT 2/62). [ Links ]

Finkel, A., 1981, 'Javneh's liturgy and early Christianity', Journal of Ecumenical Studies 18(2), 231-250. [ Links ]

Florentino, F. (ed.), 2007, Dead Sea Scrolls and other early Jewish studies in honour of Florentino Garcia Martinez, Brill, Leiden. [ Links ]

Foster, P., 2003, 'Is it possible to dispense with Q?', Novum Testamentum XLV, 313-337. http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/156853603322538730 [ Links ]

Grivel, C. (ed.), 1978, Methoden in de literatuurwetenschap, Coutinho, Muiderberg. [ Links ]

Gundry, R.H., 1982, Matthew: A commentary on his literary and theological art, Eerdmans, Grand Rapids, MI. [ Links ]

Harrington, D.J., 1986, 'The Bible rewritten (narratives)', in A. Kraft & G.W.E. Nickelsburg (eds.), Early Judaism and its modern interpreters, pp. 239-247, Scholars, Atlanta, GA. [ Links ]

Hoek, L.H., 1978, Verhaalstrategieeën: Aanzet tot een semiotisch georiënteerde narratologie, in C. Grivel (ed.), Methoden in de literatuurwetenschap, pp. 44-69, Coutinho, Muiderberg. [ Links ]

Katz, S.T., 1984, 'Issues in the separation of Judaism and Christianity after 70 CE: A reconsideration', Journal for Biblical Literature 103, 43-76. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/3260313 [ Links ]

Koester, H., 1957, Synoptische uberlieferung beiden apostolischen vátern, Akademie-Verlag, Berlin. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/3266517 [ Links ]

Koester, H., 1983, 'History and development of Mark's Gospel (From Mark to secret Mark and "Canonical Mark")', in B. Corley (ed.) Colloquy on New Testament studies: A time for reappraisal andfresh approaches, pp. 35-57, Mercer University Press, Macon, GA. [ Links ]

Koester, H, 1994, 'Written Gospels or oral tradition?', Journal for Biblical Literature 113(2), 293-297. [ Links ]

Kloppenborg Verbin, J.S., 2000, Excavating Q: The history and setting of the Sayings Gospel, Fortress, Minneapolis, MN. [ Links ]

Lührmann, D., 1989, 'The Gospel of Mark and the Sayings Collection Q', Journal for Biblical Literature 108(1), 51-71. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/3267470 [ Links ]

Mack, B.L., 1995, Who wrote the New Testament?, Harper, New York, NY. [ Links ]

Malan, C., 1985, 'Die literatuurwetenskap: Aard, terreine en metodes', in T.T. Cloete, E. Botha & C. Malan (reds.), Gids by die literatuurstudie, bl. 31-67, HAUM, Pretoria. (HAUM Literêr Gidsreeks 1). [ Links ]

Müller, M., 2013, 'Luke - The fourth Gospel? The "rewritten Bible" concept as a way to understand the nature of the later gospels', in S-Ol Back & M Kankaannieni (eds.), Voces clamantium in deserto. Essays in honor of Kari Syreeni pp. 231-242, Ábo Akademi, Ábo. (Studier I exegetik och judaistik utgivna af Teologiska fakulteten vid Ábo Akademi 11 [Ábo 2012]). [ Links ]

Neirynck, F., 1991, 'The minor agreements and the Two-Source Theory', in F. Van Segbroeck (ed.), Evangelica II: 1982-1991 collected essays, pp. 3-42, Louvain University Press, Louvain. (BETL 99). [ Links ]

Ohlhoff, H., 1985, 'Hoofbenaderings in die literatuurstudie', in T.T. Cloete, E. Botha & C. Malan (reds.), Gids by die literatuurstudie, bl. 31-67, HAUM, Pretoria. (HAUM Literêr Gidsreeks 1). [ Links ]

Petersen, A. K., 2007, 'Rewritten Bible as a borderline phenomenon: Genre, textual strategy or canonical anachronism?', in F. Florentino (ed.), Dead Sea Scrolls and other early Jewish studies in honour of Florentino Garcia Martinez, pp. 285-306, Brill, Leiden. http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/ej.9789004162921.i-836.98 [ Links ]

Robinson, J.M., Hoffmann P., & Kloppenborg, J.S. (eds.) 2003, The Sayings Gospel Q in Greek and English with parallels from the Gospels of Mark and Thomas, Fortress, Minneapolis, MN. [ Links ]

Runesson, A., 2008, Rethinking early Jewish-Christian relations: Matthean community history as Pharisaic intergroup conflict', Journal of Biblical Literature 127(1), 95-132. [ Links ]

Saldarini, A. J., 1992, 'Delegitimation of leaders in Matthew 23', Catholic Biblical Quarterly 54(4), 663-664. [ Links ]

Schmithals, W., 1985, Einleitung in die drei ersten Evangelien, De Gruyter, Berlin. [ Links ]

Schmithals, W., 1987, 'Der Konflikt zwischen Kirche und Synagogue', in M. Oeming & A. Graupner (Hrsg), Altes Testaments und Christliche Verkundigung: Festschrift fur Antonius H J Gunneweg zum 65. Geburtstag, pp. 330-375, Kohlhammer, Stuttgart. [ Links ]

Strecker, G., 1962, Der Weg der Gerechtigkeit. Untersuchung zur Theologie des Mattháus, 2. durchges. Ausgabe, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen. [ Links ]

Streeter, B. H., 1924, The four Gospels: A study of origins, treating of the manuscript tradition, sources, authorship, and dates, Macmillan, London. [ Links ]

Trevett, C., 1984, 'Approaching Matthew from the second century: The under-used Ignatian correspondence', Journal for the Study of the New Testament 20, 5967. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0142064X8400602003 [ Links ]

Van Aarde, A. G., 1994, God-with-us: The dominant perspective in Matthew's story and other essays, HTS Supplementum 5, Gutenberg, Pretoria. [ Links ]

Van Aarde, A. G., 2008, 'Matthew's intertext and the presentation of Jesus as healer-Messiah', in T.R. Hatina (ed.), Biblical interpretation in early Christian Gospels: The gospel of Matthew, vol. 2, pp. 163-182, T&T Clark, London. [ Links ]

Van Luxemburg, J., Bal, M. & Westeijn, W.G., 1983, Inleiding in de literatuurwetenschap, 3e herziene druk, Coutinho, Muiderberg. [ Links ]

Vermes, G., 1961, Scripture and tradition in Judaism: Haggadic studies, Brill, Leiden. (Studia Post Biblica series 4). [ Links ]

Vermes, G., 1986, 'Biblical Midrash', in E. Shurer (ed.), The history of the Jewish people in the age of Jesus Christ, rev. edn., vol. 3, pp. 308-341, Clark, Edinburgh. [ Links ]

Vermes, G., 1989, 'Bible interpretation at Qumran', Erets Israel 20, 185-188. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Gert Malan

PO Box 1775

Mossel Bay 6500

South Africa

Email:gertmalan@telkomsa.net

Received: 02 Nov. 2013

Accepted: 23 Feb. 2014

Published: 28 May 2014

Dr Gert Malan is a research associate of the Reformed Theological College, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa.