Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

HTS Theological Studies

versión On-line ISSN 2072-8050

versión impresa ISSN 0259-9422

Herv. teol. stud. vol.69 no.1 Pretoria ene. 2013

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Unravelling the structure of First John: Exegetical analysis, Part 1

Ron J. Bigalke

Department of New Testament Studies, University of Pretoria, South Africa

ABSTRACT

Surveying commentaries and introductions to the Johannine epistles reveals a multiplicity of methodology with regard to the structure of the epistles. Proposals have generally emphasised characteristics of content (doctrine and paraenesis), style (antithesis and repetition) or outline divisions. If the intent of the author is connected to the structure of the text, commentaries and introductions may not adequately discern the authorial intent. The lack of agreement amongst commentators as to the division of the First Epistle of John has resulted in numerous interpretative conclusions. As a consequence of difficulty in ascertaining the structure of the text, interpretations are frequently formulated upon theological persuasions and historical reconstruction. The purpose of the article is to overcome such persuasions and reconstructions.

Exegetical analysis explained

The most characteristic distinctive of exegetical analysis is to consider the biblical text beyond sentence boundaries (Hock 2009:2). Petöfi (1979) argued as follows:

The definition of the textual unit (or unities), [in other words] that unit which extends beyond the boundaries of the sentence and is larger than the sentence, is one of the most attractive problems of text-linguistics. (p. 283)

Exegetical analysis presupposes the text as the fundamental aspect of language because communication is inherent in the text as opposed to the sentence. Whilst it may be challenging for expositors not to begin their research with an emphasis upon the individual words of the text and the phraseology containing its usage and then progress to emphasis upon the clause to the larger units and ultimately to the Johannine text itself, the recognition that the text is the fundamental linguistic unit necessitates first identifying the unit boundaries within the Johannine discourse (Guthrie 1994:49-55). However, a cursory examination with regard to commentaries on the Johannine epistles will quickly demonstrate that structural analyses are often in variance with one another. The lack of agreement amongst commentators as to the division of the First Epistle of John has resulted in numerous interpretative conclusions. For instance, Brooke (1912) remarked:

While some agreement is found with regard to the possible division of the First Epistle into paragraphs, no analysis of the Epistle has been generally accepted. The aphoristic character of the writer's meditations is the real cause of this diversity of arrangement, and perhaps the attempt to analyse the Epistle should be abandoned as useless. (p. 32)

Moreover, as demonstrated by Anderson (1992:10) in his exegetical summary, even the first word of the text of the First Epistle of John demonstrates the need for a new methodology in hermeneutics:1

Most commentators think that instead of ö 'what' referring to any specific noun, it has a more complex reference. It does not refer to Jesus directly, but to that which the writer declares about Jesus [Brd]. It refers to the person, words, and acts of Jesus [AB, Brd, ICC], to both the gospel message and the person of Jesus [Herm, NIC, NTC], to both the gospel message about Jesus [Ws, WBC], to the account of r| áyyeJúa 'the message' (1:5) which is identical with the person of Jesus [Herm], to Jesus and all that he is and does for us [Ln], to Jesus as the Word and the life he manifested [EGT], the content of the Christian doctrine [HNTC]. Another thinks that it refers specifically to the Word, but the neuter form suggests that the Word cannot be adequately described in human language [TH]. (Anderson 1992:10)

As one continues to examine the discourse units of the First Epistle of John, it is evident that a more exhaustive analysis is necessary, which is not only apparent in the summary by Anderson but also becomes apparent as one peruses various commentaries. Anderson's (1992:9) exegetical summaries of the discourse units prove the necessity 'for hermeneutical methodologies that can be integrated into the exegetical analysis for the purpose of achieving a more consistent and valid structure of the text' (Bigalke 2013:39). Longacre (1996:198-201) demonstrated how important it is to discern 'the relationship between the thematic structure of the text and the exegetical units' because it would certainly be counterproductive to 'interpret a biblical text in a partitive manner without regard for the holistic structure' (Bigalke 2013:39). Porter observed the extent to which the macrostructures of a text 'convey the large thematic ideas which help to govern the interpretation of the microstructures':

Macro-structures serve two vital functions. On the one hand, they are the highest level of interpretation of a given text. On the other hand, they are the points at which larger extra-textual issues such as time, place, audience, authorship and purpose (more traditional questions of biblical backgrounds) must be considered. (Porter 1999:300)

If one is 'to adopt an holistic approach to the text of Scripture', the macrostructure must be identified, as argued previously:

Macrostructures help to identify exegetical units, whereas traditional hermeneutical methods tend to emphasize a clause or sentence of a biblical book. By identifying the macrostructure, one more discern the relationship between each section and subsection to the complete text. Therefore, the endeavor to identify the microstructure assists in answering specific noun or verbal usage within a clause or sentence. (Bigalke 2013:40)

Porter (1999:300) noted the following: 'The micro-structures are the smaller units (such as words, phrases, clauses, sentences, and even pericopes and paragraphs) which makeup macro-structures.' As semantic-structural analysis is applied to the First Epistle of John, one may readily discern the author's specific reason for employing the precise grammar of the text.

Exegetical analysis methodology

The tendency to structure the First Epistle of John partitively (microstructurally) as opposed to holistically (macrostructurally) certainly contributes to interpretative confusion, as argued previously:

Since macrostructural analysis seeks to approach the text holistically, it will seek to identify unit boundaries as opposed to focusing merely upon the sentence. The attempt to identify a relationship between each section constituent and subsection constituent that contributes to the intent of the entire text necessitates a concentrated effort to explain word grammar and sentence grammar at the microstructural level. In other words, discerning why a certain verb tense was used is more relative to the author's theme for writing, as opposed to being merely syntactical, especially considering that other options in verb usage were possible (yet only one would communicate the particular message that the author wished to convey). (Bigalke 2013:25)

Commentators have provided numerous proposals with regard to the structure of First John. However, the only agreement is regarding the prologue (1:1-4) and the conclusion (5:13-21), 'which can be frustrating for the majority of believers who seek to understand the First Epistle of John macrostructurally' (Köstenberger 2009:171). Consequently, some commentators conclude that such challenges deem it 'impossible to identify an evident structure in First John' (Bigalke 2013:25). Strecker (1996) is an example of such pessimism:

But for the most part 1 John is seen as a relatively loose series of various trains of thought hung together on the basis of association. Many exegetes therefore regard their suggested outlines more as- aids to the reader's understanding than as genuine attempts to discover a clear-cut form within the letter.2 (p. 43)

The purpose of this article is to demonstrate that such cynicism is 'unnecessary since there does appear to be a definite structure, which semantic-structural analysis can discern and will demonstrate' (Bigalke 2013:26).3 Discerning the development of the thought process - by means of the textual structure - is fundamental for understanding the meaning of First John. Bruce (1970) summarised the difficulty that has endured as one strives to identify both the purpose and structure of First John:

Attempts to trace a consecutive argument throughout I John have never succeeded. For the convenience of a commentator and his readers, it is possible to present such an analysis of the epistle ..., but this does not imply that the author himself worked to an organized plan. At best we can distinguish three main courses of thought: the first (I. 5 - 2. 27), which has two main themes, ethical (walking in light) and Christological (confessing Jesus as the Christ); the second (2. 28 - 4. 6), which repeats the ethical and Christological themes with variations; the third (4. 7 - 5. 12), where the same two essential themes are presented as love and faith and shown to be inseparable and indispensable products of life in Christ. (p. 29)

Identifying the structure of First John is a challenge that has not only impacted earlier scholarship but is also experienced by contemporary scholars. Bruce made his summary statement of the problem in 1970, and indeed, there have been improvements since that time. Dressler (1978:55-79) noted that one reason for such development is the priority given to the text as the foundational linguistic unit. Du Rand (1991) also argued as follows:

The historical information on the possible socio-cultural setting of the Johannine community (although hypothetical) should be linked up with the text-immanent analyses. To bind the text together, its cohesion and coherence on the surface level should be analysed to respond methodologically to the syntactic dimension. The logical and temporal relations underlying the text from the conceptual patterns of the semantic organisation of the text, and the pragmatic dimension, then, makes the use of the syntactic and semantic analysis and describes the meaning to be materialised in the relation between narrator and audience. (p. 96)

The analysis of such cohesion and coherence for the entirety of the First Epistle of John and the syntactic and semantic components will be the emphasis for the remainder of this article. The reason for examining the First Epistle of John by means of exegetical analysis is to discern those elements that traditional hermeneutical methods do not typically provide.

Exegetical analysis of First John 1:1-2:27

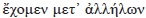

The prologue of First John uses several relative clauses, which is not only a precise usage of grammar by the apostle, but most commentators also note that such usage is uncommon. The consistency of 1:1-4 is evident in the repetition of four terms:  [we have heard] (2x),

[we have heard] (2x),  [we have seen] (3x),

[we have seen] (3x),  [was manifested] (2x) and

[was manifested] (2x) and  [we proclaim] (2x). The unit is also designated by prominence as evident in the repetition of ö [what] (5x). Furthermore, there is the plurality of witnesses (12x).4 The semantic relationship is evident in 1:1-4, yet there are also chiastic elements that indicate the cohesion of this unit. The repetition and variation in word usage demonstrates a consistent exegetical unit.

[we proclaim] (2x). The unit is also designated by prominence as evident in the repetition of ö [what] (5x). Furthermore, there is the plurality of witnesses (12x).4 The semantic relationship is evident in 1:1-4, yet there are also chiastic elements that indicate the cohesion of this unit. The repetition and variation in word usage demonstrates a consistent exegetical unit.

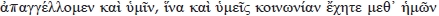

First John 1:2 is parenthetical with the emphasis upon  [the Word of life], which or who5 was mentioned at the end of verse one. Longacre (1996:13) referred to this type of phenomenon as 'tail-head linkage (in which the last sentence of one paragraph cross-references to the first sentence of the following paragraph)'. The parenthetical clause restates the assertion with regard to what the apostle saw with his own eyes, in addition to the testimony of others (

[the Word of life], which or who5 was mentioned at the end of verse one. Longacre (1996:13) referred to this type of phenomenon as 'tail-head linkage (in which the last sentence of one paragraph cross-references to the first sentence of the following paragraph)'. The parenthetical clause restates the assertion with regard to what the apostle saw with his own eyes, in addition to the testimony of others ( [what we have seen]). Verse one and verse three are chiastic, which is evident in the reverse order of the two perfects,

[what we have seen]). Verse one and verse three are chiastic, which is evident in the reverse order of the two perfects,  [we have heard] and

[we have heard] and  [we have seen], which are then followed immediately by two aorists,

[we have seen], which are then followed immediately by two aorists,  [we have looked] and

[we have looked] and  [touched]. The usage of the two perfects emphasises consistency of thought and informs the readers of the epistle that the same topic is the basis for the continued revelation.

[touched]. The usage of the two perfects emphasises consistency of thought and informs the readers of the epistle that the same topic is the basis for the continued revelation.

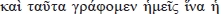

The primary verb in 1:1-4 is  [we proclaim] even though it was consigned to verse two and then again to verse three. The verb

[we proclaim] even though it was consigned to verse two and then again to verse three. The verb  emphasises the entity of examination, that is,

emphasises the entity of examination, that is,  [of life]. Whereas the construction is unique stylistically, it nevertheless conveys local prominence syntactically because the customary structure was altered. In other words, the syntax effectively emphasises that the subject of the epistle is the reason for 'the message'. Moreover,

[of life]. Whereas the construction is unique stylistically, it nevertheless conveys local prominence syntactically because the customary structure was altered. In other words, the syntax effectively emphasises that the subject of the epistle is the reason for 'the message'. Moreover,  [testify] is connected with the proclamation of

[testify] is connected with the proclamation of  [the message] as a consequence of its appositional placement in the clause and as evident in the denotation of the adverbial Kaí [and]. The normal conjunction emphasises the subsequent pronoun. Even though the unity of 1:1-4 is not generally disputed, the analysis of this section conveys the notion that semantic-structural analysis is helpful to determine interpretation. Furthermore, the identification of the coherence of 1:1-4 may indicate how the next exegetical unit is related to the previous section.

[the message] as a consequence of its appositional placement in the clause and as evident in the denotation of the adverbial Kaí [and]. The normal conjunction emphasises the subsequent pronoun. Even though the unity of 1:1-4 is not generally disputed, the analysis of this section conveys the notion that semantic-structural analysis is helpful to determine interpretation. Furthermore, the identification of the coherence of 1:1-4 may indicate how the next exegetical unit is related to the previous section.

Generally, most commentators agree that 1:5 begins a new unit. Subsequent to 1:1-4, unfortunately, there is much disagreement regarding structure. Lexically common characteristics indeed indicate a relationship between 1:5 and 1:1-4. For instance, (to use the terminology of Longacre [1992:231]) the 'tail-head- linkage' is evident in how  [these things we write] in 1:4 corresponds with

[these things we write] in 1:4 corresponds with  [this is the message] in 1:5. Moreover, prominence is evident in the transition from the apostle's authority in 1:1-4 to the content and implications of

[this is the message] in 1:5. Moreover, prominence is evident in the transition from the apostle's authority in 1:1-4 to the content and implications of  [the message], beginning with 1:5 and continuing to the end of the epistle. Furthermore, there is a change in verb usage from either the aorist or perfect tense to the present tense, and the literary genre changes from proclamation to hortatory, which is evident in the repetitive use of the phrase

[the message], beginning with 1:5 and continuing to the end of the epistle. Furthermore, there is a change in verb usage from either the aorist or perfect tense to the present tense, and the literary genre changes from proclamation to hortatory, which is evident in the repetitive use of the phrase  [if we say] that commences in 1:6. To apply these principles to other exegetical units will assist in the elimination of conflicting analyses with regard to the holistic structure of the epistle.

[if we say] that commences in 1:6. To apply these principles to other exegetical units will assist in the elimination of conflicting analyses with regard to the holistic structure of the epistle.

The methodology of traditional hermeneutical approaches to texts of Scripture is not normally focused upon the exegetical unit. Consequently, semantic-structural analysis indicates that conjunctions are not only important to discern within clauses and sentences but also within the exegetical unit itself. Determining the function of conjunctions is helpful for delineating 'boundary markers' (Erickson 2005:66; Larsen 1991b:51), which is then beneficial for identifying the primary emphasis of a text. Moreover, exegetical units or new paragraphs are often introduced by conjunctions (Larsen 1991a:48-54).

Larsen (1991b:43) noted that the primary conjunction in the Greek New Testament is Kaí [and], which would be somewhat equivalent to the waw consecutive in the Hebrew Old Testament. Titrud (1991:1-28) noted that the importance of Kaí is often minimised ('overlooked'); yet 'it is used in practically every verse of the New Testament' (Titrud 1993:240). 'When Kaí is used, it implies that what follows is closely related to what precedes; this is not so when other particles such as  [yet],

[yet],  [but], and

[but], and  [then] are used' (Titrud 1993:250). Titrud (1993:240-241) noted that even primary Greek lexicons 'seek to describe the meaning of Kaí by relating it to the meaning of various English or German constructions.' However, the usage of Kaí should be based upon its usage in the Greek New Testament as opposed to either an English or German perspective. Disagreeing with the assertion that Kaí is used commonly 'as a connective where more discriminating usage would call for other particles' (Bauer 2001:392), Titrud (1993:242; see also Allen 2010:136-137) asserted 'that Kaí was not just written arbitrarily;' rather, 'it has a particular function in the discourse structure of New Testament Greek'. By delineating what is prominent, Kaí functions as a conjunction 'both on the intraclausal and interclausal level' and indicates when one proposition is logically subordinate to another. 'When Kaí does coordinate what is semantically a subordinate clause, it is encoding more prominence upon the subordinate clause than' if introduced by other particles (Titrud 1993:255). 'The conjunctive Kaí is a coordinating conjunction; it coordinates grammatical units of equal rank' (Titrud 1991:9).

[then] are used' (Titrud 1993:250). Titrud (1993:240-241) noted that even primary Greek lexicons 'seek to describe the meaning of Kaí by relating it to the meaning of various English or German constructions.' However, the usage of Kaí should be based upon its usage in the Greek New Testament as opposed to either an English or German perspective. Disagreeing with the assertion that Kaí is used commonly 'as a connective where more discriminating usage would call for other particles' (Bauer 2001:392), Titrud (1993:242; see also Allen 2010:136-137) asserted 'that Kaí was not just written arbitrarily;' rather, 'it has a particular function in the discourse structure of New Testament Greek'. By delineating what is prominent, Kaí functions as a conjunction 'both on the intraclausal and interclausal level' and indicates when one proposition is logically subordinate to another. 'When Kaí does coordinate what is semantically a subordinate clause, it is encoding more prominence upon the subordinate clause than' if introduced by other particles (Titrud 1993:255). 'The conjunctive Kaí is a coordinating conjunction; it coordinates grammatical units of equal rank' (Titrud 1991:9).

The function of Kaí [and] is not always that of a coordinative even though there may be instances in which one proposition is logically subordinate to another. Nevertheless, when such contrast occurs between an exegetical and a logical construction, the intent of the author is 'deliberate and significant'. The syntactic emphasis upon what is 'logically subordinate' means that the author is indicating 'more prominence' upon the clause than if it were 'introduced by a subordinating conjunction' (Titrud 1991:16; Titrud 1993:250; cf. Levinsohn 2000:99-102; Runge 2010:23-26, 48-49). The relevance of Titrud's helpful research for better understanding the usage of Kai in exegetical contexts is apparent in the beginning of the First Epistle of John. For instance, in 1:5 and 2:3, Kai is located in the 'clause-initial position', which would normally indicate new information and simultaneously indicate a new exegetical unit (Butler 2003:86). Moreover, 'when Kai does introduce a new paragraph, the paragraphs are more closely linked semantically' (Titrud 1993:251). The thematic continuity and development of thought that is reflected by the Kai in the clause-initial position indicates that the subsequent clause is 'closely linked semantically' to the preceding one (ibid). Since there is not an alternative textual reading in 1:5 and 2:3, there must be a deliberate and significant reason for the use of Kai.

Titrud (1993:242-244) noted that, when Kai [and] is followed by a pronoun, the function is adverbial and thus provides emphasis,6 which may be a possible classification of Kai in 1:5 and 2:3. According to Nestle-Aland (Aland et al. 1979), Kai introduces a paragraph only in the following:

- 1 Corinthians 2:1; 3:1; 12:31

- 2 Corinthians 1:15; 7:5

- Ephesians 2:1; 6:4

- Colossians 1:21

- 1 Thessalonians 2:13

- Hebrews 7:20; 9:15; 10:11; 11:32

- 1 Peter 3:13

- 1 John 1:5; 2:3; 3:13, 19; 3:23.

Alternative textual readings can be identified in 1 Thessalonians 2:13 and 1 John 3:13, 19. The conjunction yáp [for] is a 'postposition particle' in 2 Corinthians 2:5, and the particle occurs subsequent to Kai [and], which functions adverbially in that verse. In the other uses of Kai (e.g. 1 Cor 2:1, 3:1; Eph 2:1; Col 1:21; Heb 11:32; 1 Pt 3:13; 1 Jn 1:5), there is a demonstrative, personal or relative pronoun that is immediately subsequent to Kai, which would be adverbial and would thereby likely denote emphasis upon the pronoun. With regard to determining the structure of the epistles, Titrud (1993; see also Larsen 1991b:35-47) argued as follows:

a new paragraph should not be made where a conjunctive Kai begins a sentence in the Greek text. A paragraph-initial Kai followed by a pronoun or a post-positive particle (e.g. ydp) should be classified as an adverb. (pp. 251-252)

Therefore, in both 1:5 and 2:3, a pronoun is subsequent to the clause-initial conjunction Kai [and], which indicates prominence (a 'highlighting device' [Anderson & Anderson 1993:43]), and is therefore helpful for determining the structure of the beginning chapters since Kai not only delineates thematic continuity but also a new section of the epistle.

The use of the vocative

Longacre (1992:272-276) is most notable for his emphasis upon identifying structural paragraphs based upon the distribution of vocatives. Of course, the vocative is not the only exegetical feature that delineates the structural units. In addition to the vocative, Longacre (1992:272-83) noted the distribution of the verb  [I am writing], the counting and weighing of the various kinds of verbs (i.e. either expository type or hortatory type), peaks of the book that are especially vital to the message and the macrostructure as a limitation upon the content.

[I am writing], the counting and weighing of the various kinds of verbs (i.e. either expository type or hortatory type), peaks of the book that are especially vital to the message and the macrostructure as a limitation upon the content.

Based upon the distribution of vocatives, Longacre (1992:276) asserted that one 'can posit a string of natural paragraphs', and most 'boundaries' are delineated 'with a vocative, either in the initial sentence or in a sentence or two into the body of the paragraph'. However, it is not entirely certain that one can indeed identify the structural paragraphs on the basis of whether a vocative is located at the beginning of a sentence or even within the paragraph unit. Longacre's analysis of First John indicated that there are no vocatives in the beginning of two units that he delineated: 1:5-10 and 5:1-12. The vocatives in his structural paragraphs of 3:1-6 and 3:19-24 are not 'paragraph-initial' (which, of course, Longacre admitted could occur). The vocative in 3:1-6 is found in verse 2, and, within 3:19-24, it is located in the middle of the unit (v. 21). Consequently, it seems arbitrary to begin the structural paragraphs in chapter 3, with verse 1 and verse 19, when the vocative is found later in the section. Furthermore, he stated that the thesis of First John is located in the paragraph unit of 3:19-24, and one of the doctrinal 'peaks' is located in the paragraph unit of 4:1-6. The vocative in 4:1-6 is paragraphinitial, yet there is another to be found in verse 4, which again seems arbitrary in not beginning a new structural paragraph where the second vocative is located. Therefore, one may conclude that Longacre's assertion that the vocatives constitute new units is not as resolute as initially thought.

Rogers's (1984) article addressing vocatives and boundaries demonstrated that the former is not as decisive as other factors in determining the latter. She noted:

In many places where vocatives seem to signal boundaries, other forms or factors are decisive. In itself, the vocative form cannot be said to signal change of theme. Although some writers may use vocatives only at boundaries, it should not be assumed that all do.7 (p. 26)

Larsen (1991a:51) asserted that a vocative is 'a rhetorical device, not a structural device, and it functions to establish a closer relationship with the hearers'. Callow (1999:401) noted that, within 1:6-2:2, 'the use of the vocative

[my little children], and the performative

[my little children], and the performative  [I am writing to you], focuses attention on the purpose statement, and so serves to give it added performance'. As opposed to understanding the vocative and the performative as indicating a new paragraph division, it could have a prominence function as opposed to an initiating role (particularly within the context of 1:6-2:2) (Callow 1999:401). Therefore, it would be best to understand the use of the vocative as able to introduce a new subject, whether primary or subordinate. The use of the vocative could also introduce a conclusion, which seems evident in 2:28, 3:21 and 5:21.

[I am writing to you], focuses attention on the purpose statement, and so serves to give it added performance'. As opposed to understanding the vocative and the performative as indicating a new paragraph division, it could have a prominence function as opposed to an initiating role (particularly within the context of 1:6-2:2) (Callow 1999:401). Therefore, it would be best to understand the use of the vocative as able to introduce a new subject, whether primary or subordinate. The use of the vocative could also introduce a conclusion, which seems evident in 2:28, 3:21 and 5:21.

The vocative 'children' or 'sons' was a customary rabbinical practice, which is evident throughout all varieties of Jewish literature. Griffith (2002:63-65) noted the significance of 'this particularly Jewish filial authority device', which appears to have been rejected by the gentile church. The use of the vocative functioned to emphasise both authority and equality. Van der Watt (1999:491) concluded that the ethical thought of First John was developed 'by using a coherent network of metaphors related to first-century family life'.8 He further argued as follows:

The vocative plural is found 20 times in 1 John, distributed among six nouns, and this frequency helps to generate a sense of urgent pastoral concern. agapetoi ('beloved': 2.7; 3.2, 21; 4.1, 7, 11) always occur at the head of a sentence and in contexts where love (whether for one another, or of God's love for us, or both) is stressed. paidia ('children': 2.14, 18) can convey affection, and occurs in parallel to teknia (2.12), but its association with slavery and service may account for John's preference for teknia. However, it is perhaps significant that paidia is the preferred vocative when the serious topics of the antichrist and the schism are introduced (2.18). adelphoi ('brothers': 3.13) is used once in the context of a reference to Cain's murder of his brother (3.12). (Van der Watt 1999:65)9

Callow (1999:401) noted that a better understanding of  [my little children] in 2:1, with the immediately subsequent

[my little children] in 2:1, with the immediately subsequent  [I am writing to you], was to give additional prominence to the purpose statement,

[I am writing to you], was to give additional prominence to the purpose statement,

[that you may not sin]. Assuming that Callow is correct, the vocative in 2:1 would provide reassurance immediately subsequent to the resolute denunciation in 1:10. Consequently, it would be awkward and unnatural to regard the vocative as indicating a new paragraph. The usages of the vocatives throughout the First Epistle of John serve to provide encouragement to the believers (cf. 2:12-13; 4:4).

[that you may not sin]. Assuming that Callow is correct, the vocative in 2:1 would provide reassurance immediately subsequent to the resolute denunciation in 1:10. Consequently, it would be awkward and unnatural to regard the vocative as indicating a new paragraph. The usages of the vocatives throughout the First Epistle of John serve to provide encouragement to the believers (cf. 2:12-13; 4:4).

The majority of the vocatives within First John introduces a conclusion or has a tail-head linkage where a motif or word from the 'tail' of the last clause or sentence of one paragraph is located in the first clause or sentence of the subsequent paragraph. For example, the vocatives in 2:1, 7; 3:18, 21; 4:4 and 5:1 all seem to provide a conclusion to the aforementioned propositions. The vocatives in 2:18, 28 and 3:2 seem to have a tail-head linkage. The vocatives in 4:1, 11 are difficult to identify as either conclusions or as of the- tail-head variety. First John 2:12-14 is unique with its usage of six vocatives; it would seem best to regard that section as providing encouragement. Of course, verses that are typically regarded as beginning new sections, such as 1:1 and 5:1, do not contain any vocatives. Consequently, the vocatives do not always indicate new structural paragraphs (i.e. this is not their primary purpose, even though they can be used for this reason) and were often used to give prominence (when used in this manner, the vocatives may correspond to other structural paragraphs to delineate exegetical units).

The use of coherence

Coherence has previously been defined as indicating the relationship between parts of one unit and another (i.e. 'the constituents of a unit will be semantically compatible with one another') (Beekman 1981:21). Semantic and structural cohesion in First John 1:5-2:2 will prove the assertion that the vocative in 2:1 does not initiate a new structural paragraph. The contention here is that  [my little children] in 2:1 was used to initiate a concluding exhortation to the constituents of a unit that began in 1:5. Moreover, the occurrence of Kai sáv [and if] in 2:1 'introduces the last of a series of six conditional clauses, supporting the idea of a unit' (Sherman & Tuggy 1994:29). 'Although Kaí [and] is a conjoining and not a contrastive particle', it should be translated as 'but' in 2:1 because 'two conjoined clauses or sentences have contrastive content' (cf. 1:6) (Titrud 1991:24; Larsen 1991b:43). Akin (2001) asserted that Kaí in 2:1 should be translated as 'and':

[my little children] in 2:1 was used to initiate a concluding exhortation to the constituents of a unit that began in 1:5. Moreover, the occurrence of Kai sáv [and if] in 2:1 'introduces the last of a series of six conditional clauses, supporting the idea of a unit' (Sherman & Tuggy 1994:29). 'Although Kaí [and] is a conjoining and not a contrastive particle', it should be translated as 'but' in 2:1 because 'two conjoined clauses or sentences have contrastive content' (cf. 1:6) (Titrud 1991:24; Larsen 1991b:43). Akin (2001) asserted that Kaí in 2:1 should be translated as 'and':

John never uses Kaí to connect opposing thoughts in 1 John. He uses either

or

See

as 'but' in 1:7; 2:5, 11, 17; 3:17; 4:18 (the

in 5:5 and 5:20 are probably just 'and'). See

as 'but' in 2:2, 7, 16, 19 (twice), 21, 27; 3:18; 4:1, 10, 18; 5:6, 18. Cf. the literal translation of the NASB on these verses. (The NASB does inexplicably translate

in 2:20 as 'but'; it also translates

'except,' as 'but' in 2:22 and 5:5.) (p. 77, fn. 142)

However, as Larsen and Titrud noted, there are contrasting notions in 2:1. Therefore, the use of Kaí [and], as opposed to other conjunctions such as  [yet] or

[yet] or  [but], can be explained by the semantic compatibility of 2:1 with 1:10, which does not occur when other conjunctions are used (Titrud 1991:17). Certainly, the syntactical argument by Akin is persuasive. However, the semantic analysis of First John reveals a contrastive content that is best represented by translating Kaí as 'but'.

[but], can be explained by the semantic compatibility of 2:1 with 1:10, which does not occur when other conjunctions are used (Titrud 1991:17). Certainly, the syntactical argument by Akin is persuasive. However, the semantic analysis of First John reveals a contrastive content that is best represented by translating Kaí as 'but'.

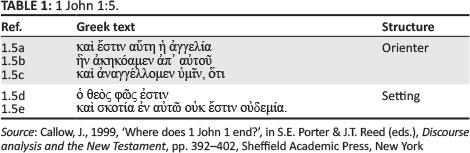

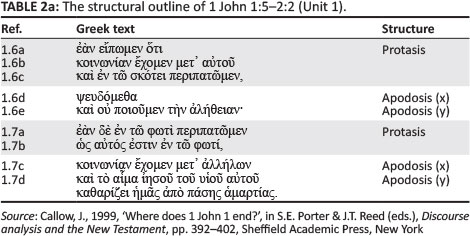

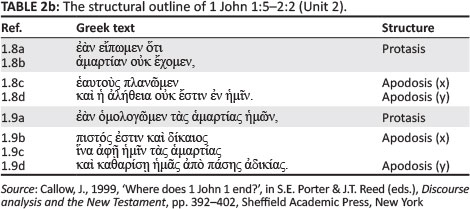

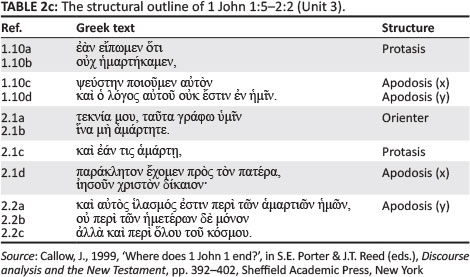

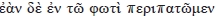

Callow (1999:396-397) demonstrated that there is a definite threefold arrangement in the Greek text of 1:5-2:2, which is reproduced ensuing tables (see Table 1 and Table 2a-c).10 The threefold arrangement is labelled as units 1, 2 and 3. Each of the three subunits (1:6-7; 1:8-9; 1:10-2:2) were structured with two protases, in addition to an apodosis construction. There are a total of six protases (1:6a; 1:7a; 1:8a; 1:9a; 1:10a; 2:1c), each introduced by sáv [if]. Each apodosis has a dual structure with the second half of each case introduced by Kaí (1:6e; 1:7d; 1:8d; 1:9d; 1:10d; 2:2a).

Brown (1995:237) also noted the use of protases and apodoses. His structural analysis is somewhat different than that of Callow, as seen in the ensuing representation:

(a) PROSTASES

7ab: But if we walk in the light as He Himself is in light

9a: But if we confess our sins

2:1b: But if anyone does sin

(b) COMPOUND APODOSES

7c: we are joined in communion with one another

7de: and the blood of Jesus, His Son, cleanses us from all sin

9bc: He who is reliable and just will forgive us our sins

9d: and cleanse us from all wrongdoing

2:1cd: we have a Paraclete in the Father's presence, Jesus Christ, the one who is just,

2:2abc: and he himself is an atonement for our sins, and not only for our sins but also for the whole world.

Brown (1995:237-238) noted the contrasting structure of the three protases. The first protasis exhorts the believer to 'walk in the light', whereas the other two protases assume that some walking in the darkness will occur and inform the believer how to respond. The apodoses are theological and are structured in a compound manner. Each conditional sentence (sav [if]) of disapproval corresponds to a conditional sentence of approval.

First John 1:5 contains the first orienter, and therefore, this verse can be understood as the introduction for the three subunits. The orienter in '2:1a and 1b break[s] the pattern, which, if strictly regular, would have started at 1c' (Callow 1999:396).11 The clause-initial Kai [and] was used in both 1:5 and 2:1 and was followed by a pronoun, thereby indicating an adverbial function and prominence (Titrud 1993:242-244). For this reason, Brown (1995:248) noted that the clause initial Kai in 2:3 'is not a simple connective, as THLJ rightly observes.' Haas, De Johne and Swellengrebel (1972:38) noted that Kai 'does not have connective or transitional force here but serves to emphasize the subsequent  [in this]'. A similar clause initial Kai, in addition to a slightly different form of the demonstrative (

[in this]'. A similar clause initial Kai, in addition to a slightly different form of the demonstrative ( [this]), was located in 1:5 (

[this]), was located in 1:5 ( in 2:3) wherein John stated

in 2:3) wherein John stated  [we announce], and subsequent to 'three pairs of conditional sentences', that he would 'now' inform his readers with regard to knowing 'the God who is light' (Brown 1995:248).

[we announce], and subsequent to 'three pairs of conditional sentences', that he would 'now' inform his readers with regard to knowing 'the God who is light' (Brown 1995:248).

First John 1:5 certainly corresponds to Callow's unit 1 (1999:398), which then corresponds to unit 2, and finally, unit 2 corresponds to unit 3. Therefore, 1:5-2:2 is characterised by semantic cohesion, resulting in 'a recognisable unit of thought'. The semantic structure of 1:5-2:2 emphasises the apodosis as more important than the protasis to which it corresponds. The apodosis is the primary clauses whereas the protasis is subordinate. Consequently, Callow (1999) argued that in 1:6-2:2:

... the only concept that meets the ... criteria for a topic is the concept 'sin', formally introduction in 7d with the noun

(in the phrase

). This noun is repeated in 8b, 9a, 9c and 2a; the corresponding verb is used in 10b, 1b and 1c; and the synonym áSiria is used in 9d. And although in 2.2 the noun is used only once, the

phrases that are used in 2b and 2c clearly presuppose the

of 2a. (p. 400)

God's provision for overcoming sin is stated in 2:2, which is the most important revelation for concluding the discussion with regard to sin (Callow 1999:401; Sherman & Tuggy 1994:29).

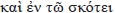

One can demonstrate that  [light] and

[light] and  [fellowship] are intimately related in thought by comparing the protases in 6b

[fellowship] are intimately related in thought by comparing the protases in 6b  [we have fellowship with Him]) and 7a

[we have fellowship with Him]) and 7a  [but if we walk in the Light]) with the apodases in 6c

[but if we walk in the Light]) with the apodases in 6c

[and in the darkness we walk]) and 7c

[and in the darkness we walk]) and 7c

[we have fellowship with one another]). Therefore, the development of thought continues from 1:5 to the end of the unit, which is 2:2. Moreover, the

[we have fellowship with one another]). Therefore, the development of thought continues from 1:5 to the end of the unit, which is 2:2. Moreover, the  [light] and

[light] and  [darkness] motif, which began in 1:5, is evidently cohesive to the end of 2:2. The emphasis of 1:5-2:2 is upon sin. Therefore, verse 5 states, 'God is Light, and in Him there is no darkness at all.' The thought progression is then evident in verse 6, which reveals that

[darkness] motif, which began in 1:5, is evidently cohesive to the end of 2:2. The emphasis of 1:5-2:2 is upon sin. Therefore, verse 5 states, 'God is Light, and in Him there is no darkness at all.' The thought progression is then evident in verse 6, which reveals that  with God is evident when one does not 'walk'

with God is evident when one does not 'walk'  [in the darkness]. To have

[in the darkness]. To have  with God is also evident in that 'the blood of Jesus ... cleanses us from all sin' (2:7), which is contrasted to those who say that they have no sin (2:8-10). First John 2:1-2 continues to address the notion of sin by revealing that the believer has 'an Advocate with the Father' who is the

with God is also evident in that 'the blood of Jesus ... cleanses us from all sin' (2:7), which is contrasted to those who say that they have no sin (2:8-10). First John 2:1-2 continues to address the notion of sin by revealing that the believer has 'an Advocate with the Father' who is the  [propitiation] for sin.

[propitiation] for sin.

As already stated, the only concept that could be regarded as a topic from 1:5-2:2 is the issue of sin, which was introduced formally in 1:7. The noun  [sin] is repeated throughout 1:8-9. The issue of sin is continued from 1:10 and then stated again in 2:2, with three parallel prepositional phrases (

[sin] is repeated throughout 1:8-9. The issue of sin is continued from 1:10 and then stated again in 2:2, with three parallel prepositional phrases ( [for]) indicating that

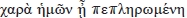

[for]) indicating that  is the primary issue in the cohesive unit of 1:5-2:2. Moreover, the apostle indicated that his reason for writing is that believers would not sin (2:1). Callow (1999:397-401) concluded that this reason 'refers to the purpose of this unit, not to the epistle as a whole', which is evident when one contrasts the purpose statements in 1:3 (

is the primary issue in the cohesive unit of 1:5-2:2. Moreover, the apostle indicated that his reason for writing is that believers would not sin (2:1). Callow (1999:397-401) concluded that this reason 'refers to the purpose of this unit, not to the epistle as a whole', which is evident when one contrasts the purpose statements in 1:3 (  [we proclaim to you also, in order that you too may have fellowship with us]) and 1:4 (

[we proclaim to you also, in order that you too may have fellowship with us]) and 1:4 (

[and these things we write to you, in order that our joy may be made complete]) that are located in the introduction of John's Epistle, and therefore, indicate the purpose for the entire letter and not just a portion of it. The vocative

[and these things we write to you, in order that our joy may be made complete]) that are located in the introduction of John's Epistle, and therefore, indicate the purpose for the entire letter and not just a portion of it. The vocative  [my little children] would then give prominence to the purpose statement.

[my little children] would then give prominence to the purpose statement.

First John 2:3-11 is the second subunit of 1:5-2:11, which is evident from the resumption of the  [light] and

[light] and  [darkness] motif in 2:8-11. The motif began in 1:5; therefore, this verse provides the theological proposition which is preliminary for the entire unit. With the repetition of the

[darkness] motif in 2:8-11. The motif began in 1:5; therefore, this verse provides the theological proposition which is preliminary for the entire unit. With the repetition of the  and

and  motif in 2:8-11, the primary unit of 1:5-2:11 may be then understood as an inclusio.12 The nature of summarising expressions is to unify the information to which they allude or state, thereby implying that the preceding facts are to be understood as a crucial component for what is subsequent. With regard to non-narrative texts, summarising expressions thus indicate structural paragraphs, that is, a conclusion will often repeat information from an introduction in some manner (Larsen 1991b:51). To understand 1:5-2:11 as a primary unit, with 2:12 commencing the next unit, is based upon the linguistic data.13

motif in 2:8-11, the primary unit of 1:5-2:11 may be then understood as an inclusio.12 The nature of summarising expressions is to unify the information to which they allude or state, thereby implying that the preceding facts are to be understood as a crucial component for what is subsequent. With regard to non-narrative texts, summarising expressions thus indicate structural paragraphs, that is, a conclusion will often repeat information from an introduction in some manner (Larsen 1991b:51). To understand 1:5-2:11 as a primary unit, with 2:12 commencing the next unit, is based upon the linguistic data.13

The vocative  [beloved] appears in 2:7, which Longacre (1992:273) understood to introduce a new structural paragraph. The reference to 'a new commandment' and

[beloved] appears in 2:7, which Longacre (1992:273) understood to introduce a new structural paragraph. The reference to 'a new commandment' and  [I am writing to you] in the same verse is the- reason why many commentators have made a structural division subsequent to 2:6. However, as noted throughout the examination of 1:5-2:2, the vocative indicates prominence with regard to the subsequent propositions. First John 2:6 progresses from emphasis on general statements with regard to all commandments, such as walking in the light and having fellowship, to the more specific commandment that those in the

[I am writing to you] in the same verse is the- reason why many commentators have made a structural division subsequent to 2:6. However, as noted throughout the examination of 1:5-2:2, the vocative indicates prominence with regard to the subsequent propositions. First John 2:6 progresses from emphasis on general statements with regard to all commandments, such as walking in the light and having fellowship, to the more specific commandment that those in the  [light] and in

[light] and in  [fellowship] are to love one another (Callow 1999:403, fn. 431).

[fellowship] are to love one another (Callow 1999:403, fn. 431).

The concepts of  [light] and

[light] and  [darkness] occur at least once in 2:8-11. The use of

[darkness] occur at least once in 2:8-11. The use of  is the most frequent, with one occurrence in verses 8 and 9 and three occurrences in verse 11. Verses 8-11 employ

is the most frequent, with one occurrence in verses 8 and 9 and three occurrences in verse 11. Verses 8-11 employ  for a total of three times: once in each of the verses, with the exception of verse 11. Subsequent to 2:8-11, the concepts of

for a total of three times: once in each of the verses, with the exception of verse 11. Subsequent to 2:8-11, the concepts of  and

and  are not referenced any longer, which means that these verses form an inclusio with 1:5-7. Furthermore, 2:12 is the first verse of a quite distinctive section as evident in the repeated phrases

are not referenced any longer, which means that these verses form an inclusio with 1:5-7. Furthermore, 2:12 is the first verse of a quite distinctive section as evident in the repeated phrases  [I am writing to you] with

[I am writing to you] with  [that] (once in 2:12 and twice in 2:13) and

[that] (once in 2:12 and twice in 2:13) and  [I have written to you] with on (thrice in verse 14). The division between 2:11 and 2:12 is evident by the senary phraseology and the fact that only 1:5-2:11 contain the

[I have written to you] with on (thrice in verse 14). The division between 2:11 and 2:12 is evident by the senary phraseology and the fact that only 1:5-2:11 contain the  motif.

motif.

Other apparent lexical and structural parallels between 1:5-2:2 and 2:3-11 demonstrate that First John 1:5-2:2 is a cohesive unit and 2:3-11 is the second subunit of 1:5-2:11. For example, the usage of  in 1:8 and 1:10, in addition to

in 1:8 and 1:10, in addition to  in 1:9, corresponds to the threefold usage of

in 1:9, corresponds to the threefold usage of  in 2:4, 2:6 and 2:9. The assertions in 1:6 (

in 2:4, 2:6 and 2:9. The assertions in 1:6 ( ) and 2:4 (

) and 2:4 ( ) are quite similar in addition to those in 1:8 (

) are quite similar in addition to those in 1:8 ( and 2:4 (

and 2:4 (

). The subjunctive use of

). The subjunctive use of  occurs repeatedly in both 1:5-2:2 and 2:3-11, yet the verb does not occur again throughout First John. The vocatives,

occurs repeatedly in both 1:5-2:2 and 2:3-11, yet the verb does not occur again throughout First John. The vocatives,  (2:1) and

(2:1) and  (2:7), were used medially for prominence. The repetition of

(2:7), were used medially for prominence. The repetition of  in 1:10 and then again in 2:5 and 2:7 is also a notable correspondence. In addition to these parallels, there is the inclusio of 1:5-2:11 that has already been mentioned, which indicates that 1:5-2:11 is a primary semantic unit, consisting of two subunits: 1:5-2:2 and 2:3-11 (with 1:5 providing the theological proposition, which is preliminary for the entire unit; thus the first subunit could be regarded as 1:6-2:2) (Callow 1999:402-404).

in 1:10 and then again in 2:5 and 2:7 is also a notable correspondence. In addition to these parallels, there is the inclusio of 1:5-2:11 that has already been mentioned, which indicates that 1:5-2:11 is a primary semantic unit, consisting of two subunits: 1:5-2:2 and 2:3-11 (with 1:5 providing the theological proposition, which is preliminary for the entire unit; thus the first subunit could be regarded as 1:6-2:2) (Callow 1999:402-404).

Longacre (1992:273, 277-279) included 2:12-14 with 2:15-17 based upon the  [I am writing] and

[I am writing] and  [I have written] formulae in verses 12 and 13, which can be regarded as a 'somewhat elaborate introduction to the paragraph'. Moreover, the imperatives in 2:15-17 indicate overt, negative commands as opposed to commands that are being mitigated.14 Longacre's unit is noteworthy because 2:12-14 contain six of the nineteen vocatives (cf. 2:1, 7, 18, 28; 3:2, 7, 13, 18, 21; 4:1, 4, 7, 11) and six of the twelve orienters (2:1, 7, 8, 26; 3:19; 5:13) that are located throughout the epistle. The first imperative in First John is located in 2:15, with the majority of the ten imperatives occurring in the middle of the epistle and only one located in chapter 5 (Fantin 2010:195). For this reason, Longacre (1983:9, 11) regarded 2:12-17 as indicating 'a peak of the discourse which embeds within the Introduction to the book' (1:1-2:29). Callow (1999:404) regarded 2:12-14 as possibly constituting a transitory unit, thereby providing a relationship between 1:5-2:11 and the subsequent revelation. Grayston (1984:4) also understood 2:12-14 as 'a transition from the statement to the writer's development of it'.15 Indeed, it would be best to understand 2:12-14 as a transitory unit as opposed to a component of Longacre's structural division from 2:12 to 2:17.

[I have written] formulae in verses 12 and 13, which can be regarded as a 'somewhat elaborate introduction to the paragraph'. Moreover, the imperatives in 2:15-17 indicate overt, negative commands as opposed to commands that are being mitigated.14 Longacre's unit is noteworthy because 2:12-14 contain six of the nineteen vocatives (cf. 2:1, 7, 18, 28; 3:2, 7, 13, 18, 21; 4:1, 4, 7, 11) and six of the twelve orienters (2:1, 7, 8, 26; 3:19; 5:13) that are located throughout the epistle. The first imperative in First John is located in 2:15, with the majority of the ten imperatives occurring in the middle of the epistle and only one located in chapter 5 (Fantin 2010:195). For this reason, Longacre (1983:9, 11) regarded 2:12-17 as indicating 'a peak of the discourse which embeds within the Introduction to the book' (1:1-2:29). Callow (1999:404) regarded 2:12-14 as possibly constituting a transitory unit, thereby providing a relationship between 1:5-2:11 and the subsequent revelation. Grayston (1984:4) also understood 2:12-14 as 'a transition from the statement to the writer's development of it'.15 Indeed, it would be best to understand 2:12-14 as a transitory unit as opposed to a component of Longacre's structural division from 2:12 to 2:17.

Most commentators note the unique characteristics of 2:12-14 as a consequence of the senary vocatives and senary orienters. The primary reason why Longacre (1983:13) structured 2:12-17 as one unit (as opposed to two) was the fact that another vocative appeared only in 2:18.16 The repetitive usage of the vocatives 'is a way of reinforcing the message by repeating the verb "write" six times' (Miehle 1981:270-271).17 Another unique characteristic of 2:12-14 is the variation of tense from the present (ypápc [I am writing]) in 2:13 to the aorist (sypai|/a [I have written]) in 2:14, and this change continues throughout the epistle and to the very conclusion of First John (cf. 2:21, 26; 5:13). Longacre (1992:266-277; 1983:11-14) identified the subsequent units as 2:18-27 and 2:28-29, which he understood to be the concluding sections of the introduction, thus 'the body of the work' does not begin until 3:1 and continues to 5:12. The evidence of this assertion is that the verb ypápc occurs only in the introduction (1:1-2:29) and the conclusion (5:13-21).

John already explained what it means to have fellowship with God and thus to walk in the Light. The message is somewhat similar to that of the epistle of James wherein one reads that 'faith, if it has no works, is dead' (2:17). John's 'work' involves not walking in the darkness. Regardless of one's profession to abide in God, if someone does not 'walk in the Light,' such an individual remains in the darkness and has been blinded (1:5-2:11):

The author now turns directly to his readers, having refuted the errors of his opponents. He seeks to assure his readers of their salvation (vv. 12-14), and he urges them to reject all evil love of the world (vv. 15-17). (Schnackenburg 1992:115)

First John 2:12-14 is addressed to those who do walk in the Light and further explains what such fellowship entails.

The next unit (2:15-17) contains the overt command to 'not love the world' for it 'is passing away'. Consequently, the lack of coherence in 2:15-17 indicates that it should be regarded as a new unit. The unit is demarcated 'by its lack of explicit vocatives and by the negative commands',

[do not love the world nor the things in the world]. Moreover, 'two other prevalent themes' that unify 2:15-17 include the references to

[do not love the world nor the things in the world]. Moreover, 'two other prevalent themes' that unify 2:15-17 include the references to  [world] and

[world] and  [God] (Miehle 1981:272). The overt prohibition of 2:15 contains obvious prominence. The prohibition is the first overt command in First John; nevertheless, the entire epistle is characteristically hortative. Longacre (1983:13) explained that the commands are initially mitigated, yet become more overt as the epistle reaches its conclusion. Therefore, as Longacre (ibid) indicates:

[God] (Miehle 1981:272). The overt prohibition of 2:15 contains obvious prominence. The prohibition is the first overt command in First John; nevertheless, the entire epistle is characteristically hortative. Longacre (1983:13) explained that the commands are initially mitigated, yet become more overt as the epistle reaches its conclusion. Therefore, as Longacre (ibid) indicates:

... in 15b, we have the by now familiar use of a conditional clause to express a covert command; here 'if any man love the world' equal 'don't love the world' and echoes in mitigated form the overt imperative of the preceding clause. (p. 13)

Smith (1991:65) noted the lack of 'a more explicit connection' between 2:12-14 and 2:15-17, yet affirmed that an 'intrinsic relationship is real enough'. His argument is based upon the assertion that 'the warnings against the world' must be elaborated, thus the 'elaborate words of address lead to a strong warning against worldliness' (ibid). According to Smith (1991:65), if one were to divide 2:12-17 into two units, this would result in the 'elaborate words of address' (2:12-14), lacking the warning of 2:15-17. Brown (1995:294-302) noted a threefold problem for determining the intent of 2:12-14. The first issue is the 'alteration of tenses' between ypápc [I am writing] and sypa|a [I have written] (Brown 1995:294). The second issue is the 'different groups of people' who are addressed as  [little children],

[little children],  [fathers],

[fathers],  [youths] and

[youths] and  [children] (Brown 1995:297). The third issue is with regard to the interpretation of öxi [that] (Brown 1995:300). The alteration of tenses could be either stylistic or epistolary. If the latter, John was referring to the truths that they already knew (including 'past writings or John's letters in general') (Miehle 1981:271), and it could also be the apostle's means for preparing his readers for the overt prohibition of 2:15 (i.e. the relationship of trust between John and his readers was reinforced by his assertion that he already trusted them) (Sherman & Tuggy 1994:42). John addressed three groups of readers - children, fathers and young men - who may have been divided chronologically by age, or the division may denote spiritual maturity. 'Fathers' is not sequential, however, which would indicate that the chronological or maturity interpretation is inconsistent. Furthermore, the epistle addresses all readers as 'children' (2:1, 28; 3:7, 18; 4:4; 5:21), which would indicate that all the addresses could be regarded as 'children', 'fathers' and 'young men'.18

[children] (Brown 1995:297). The third issue is with regard to the interpretation of öxi [that] (Brown 1995:300). The alteration of tenses could be either stylistic or epistolary. If the latter, John was referring to the truths that they already knew (including 'past writings or John's letters in general') (Miehle 1981:271), and it could also be the apostle's means for preparing his readers for the overt prohibition of 2:15 (i.e. the relationship of trust between John and his readers was reinforced by his assertion that he already trusted them) (Sherman & Tuggy 1994:42). John addressed three groups of readers - children, fathers and young men - who may have been divided chronologically by age, or the division may denote spiritual maturity. 'Fathers' is not sequential, however, which would indicate that the chronological or maturity interpretation is inconsistent. Furthermore, the epistle addresses all readers as 'children' (2:1, 28; 3:7, 18; 4:4; 5:21), which would indicate that all the addresses could be regarded as 'children', 'fathers' and 'young men'.18

The best interpretation of oil seems to be declaratively as 'that' (rather than 'because' or 'since'). The reason is that the context indicates that John was referring to truths that they already knew (2:21), that is, he referred to their current experience and declared his message to them on that basis. Brown (1995:349-350) noted that the causative 'because, since' is affirmed by many scholars, yet recent commentators affirm the particle as declarative. Schnackenburg (1992:115-116, 118), for example, rejected the notion that John's readers needed reassurance with regard to those truths that they already knew; rather, the Christians who are addressed already enjoy 'the salvation they desire'.

The senary vocatives in 2:12-14 are not insignificant, yet neither is it conclusive that 2:15-17 should be regarded as a structural paragraph. First John 2:12-14 is certainly unique, which seems to indicate that it should be distinguished from 2:15-17. However, 2:12-14 is also not unrelated to 2:15-17 and could even be distinguished as a 'peak' (according to Longacre's usage). For instance, Malatesta (1978:167) noted: 'Although no connecting particles relate 12-14 to what precedes (9-11) or to what follows (15-17), the passage is related to both.' First John 2:12-14 is 'prepared by 7-11' and 'is directed principally to what follows, since believers (12-14) will be contrasted with the world (15-17) and antichrists (18-28)'. First John 2:12-14 could be regarded as a parenthesis, which contrasts the selfless love that characterises one who is in the Light (2:7-11) with the selfish love that characterises the unbelieving world (2:15-17); therefore, 2:12-14 is indeed related to both units (Sherman & Tuggy 1994:43).

Disagreement as to whether 2:18 begins a new structural paragraph generally relates to the statement regarding the world 'passing away', that is, whether verse 18 continues the theme or begins a new section. Marshall (1978:147-148) noted the 'slight' relationship with the preceding section. John 'told his readers that the world is passing away; he now bids them note that it is in fact approaching the end. It is the last hour, as various signs make clear' (Marshall 1978:147). The thought progression with regard to 'the last hour' is somewhat related to the statement 'that the world is passing away' (Marshall 1978:147-148). The primary concern is an increasing number of individuals who are opposed to the truth. Schnackenburg (1992:129) regarded the transition as 'didactic and parenetic', with a new emphasis upon the 'last hour', as a consequence of 'heretical teachers who deny the central point of the Christological message, the saving significance of Jesus Christ'.

As in 2:12, the readers of the epistle are addressed as  [children], which would seem to indicate that 2:18 begins a new structural paragraph. The distinct features of this section, with the preceding and subsequent paragraphs, is the emphasis upon the

[children], which would seem to indicate that 2:18 begins a new structural paragraph. The distinct features of this section, with the preceding and subsequent paragraphs, is the emphasis upon the  [last hour] (2:18) and the

[last hour] (2:18) and the  [antichrist] (2:18, 22). The unit also emphasises the following motifs:

[antichrist] (2:18, 22). The unit also emphasises the following motifs:  [abide] (2:24),

[abide] (2:24),  [promise] (2:25) and [eternal life] (2:25). Another distinguishing characteristic of this section that emphasises coherence is the contrast between 'the one who denies that Jesus is the Christ' (2:23) and those who 'abide in the Son and in the Father' (2:24). Prominence in 2:18-27 is evident by the adjoined phrases in 2:20-23 and 2:24-25. The anaphoric

[promise] (2:25) and [eternal life] (2:25). Another distinguishing characteristic of this section that emphasises coherence is the contrast between 'the one who denies that Jesus is the Christ' (2:23) and those who 'abide in the Son and in the Father' (2:24). Prominence in 2:18-27 is evident by the adjoined phrases in 2:20-23 and 2:24-25. The anaphoric  [these] in 2:26 is, of course, a reference to previous constituents, which could be the entirety of First John to this point, or, as Painter (2002:208) asserted, it could refer to 2:18-25. Painter's suggestion considered the first specific mention of the antichrists, and therefore,

[these] in 2:26 is, of course, a reference to previous constituents, which could be the entirety of First John to this point, or, as Painter (2002:208) asserted, it could refer to 2:18-25. Painter's suggestion considered the first specific mention of the antichrists, and therefore,  [these] is best understood as a conclusion to the section. The phrase

[these] is best understood as a conclusion to the section. The phrase  [one confesses the Son] is asserted in the imperative because there is emphasis upon positively acknowledging Jesus as the Christ and the negative statement that the one who denies this truth 'is the antichrist'. The second adjoined phrase is stated as a command:

[one confesses the Son] is asserted in the imperative because there is emphasis upon positively acknowledging Jesus as the Christ and the negative statement that the one who denies this truth 'is the antichrist'. The second adjoined phrase is stated as a command:  [let abide]. First John 2:18-19 provides additional justification for acknowledging the Son and for abiding in the truth. Moreover, the fact that it is the

[let abide]. First John 2:18-19 provides additional justification for acknowledging the Son and for abiding in the truth. Moreover, the fact that it is the  [last hour] makes the commands all the more important to heed (Miehle 1981:273-274).

[last hour] makes the commands all the more important to heed (Miehle 1981:273-274).

First John 2:18-27 emphasises the distinction between the  [anointing] received 'from the Holy One' who19 allows believers to know all things and those who cannot discern between lies and truth. First John 2:22 inquires, '[w]ho is the liar but the one who denies that Jesus is the Christ?' The antichrist 'denies the Father and the Son;' therefore, 'whoever denies the Son does not have the Father' (1 Jn 2:22-23). Confessing the Son indicates that one 'has the Father also' (1 Jn 2:23) and abides in that which was 'heard from the beginning' (1 Jn 2:24). Abiding in the Son and in the Father culminates in 'the promise', that is, 'eternal life' (1 Jn 2:25). For this reason, John's readers received warning regarding the antichrists and were reminded that if they abide in the

[anointing] received 'from the Holy One' who19 allows believers to know all things and those who cannot discern between lies and truth. First John 2:22 inquires, '[w]ho is the liar but the one who denies that Jesus is the Christ?' The antichrist 'denies the Father and the Son;' therefore, 'whoever denies the Son does not have the Father' (1 Jn 2:22-23). Confessing the Son indicates that one 'has the Father also' (1 Jn 2:23) and abides in that which was 'heard from the beginning' (1 Jn 2:24). Abiding in the Son and in the Father culminates in 'the promise', that is, 'eternal life' (1 Jn 2:25). For this reason, John's readers received warning regarding the antichrists and were reminded that if they abide in the  [anointing], who was received 'from Him' and who abides in them (1 Jn 2:27), they will 'have no need for anyone to teach' them because the

[anointing], who was received 'from Him' and who abides in them (1 Jn 2:27), they will 'have no need for anyone to teach' them because the  will teach them the truth (1 Jn 2:27). Consequently, they are to 'abide in Him' (1 Jn 2:27).

will teach them the truth (1 Jn 2:27). Consequently, they are to 'abide in Him' (1 Jn 2:27).

The intent of 2:18-27 is both expository and hortatory (Longacre 1983:14). John's readers are to abide in the truth, which they have 'heard from the beginning' (1 Jn 2:24). The subunits of 2:18-27 are identified by the threefold usage of the emphatic pronoun  [you] in verses 20, 24 and 27. The first subunit (2:18-23) is expository, as evident from the predominance of

[you] in verses 20, 24 and 27. The first subunit (2:18-23) is expository, as evident from the predominance of  [it is] and

[it is] and  [have]. The second subunit (2:24-27) is hortatory, as evident from the predominance of

[have]. The second subunit (2:24-27) is hortatory, as evident from the predominance of  [let abide] and

[let abide] and  [will abide]. First John 2:18-27 provides much emphasis upon the concept of abiding with the verb |évc [abide, live, remain] occurring seven times (2:19, 24, 27, 28). The believer has an anointing from God and should abide in it. First John 2:26-27, therefore, concludes the section with an overt command to abide in God 'as His anointing teaches you' (1 Jn 2:27).

[will abide]. First John 2:18-27 provides much emphasis upon the concept of abiding with the verb |évc [abide, live, remain] occurring seven times (2:19, 24, 27, 28). The believer has an anointing from God and should abide in it. First John 2:26-27, therefore, concludes the section with an overt command to abide in God 'as His anointing teaches you' (1 Jn 2:27).

Conclusions for interpretation

The exegetical analysis of First John 1:1-2:27 indicates the important aspects of the epistle. The authentic and authoritative proclamation of the gospel message is the emphasis in the prologue (1:1-4). John hoped that his readers would appropriate this revelation for the purpose of fellowship (1:3) and experience the completeness of their joy (1:4). The foundation for comprehending the first structural unit of First John is identifiable in the summary statement of 1:5 ('God is Light, and in Him there is no darkness at all'). The perspective herein was previously summarised as follows:

Subsequent to the foundational statement of 1:5, the claims and false propositions between John and his opponents comprise the first primary structural unit (1:5-2:2). The negative apodoses were introduced by a protasis with the

clause (1:6, 8, 10), whereas the positive apodoses were introduced with protases containing only sáv (1:7, 9; 2:1). The somberness of the assertion in 1:10 (

) necessitates the assurance provided to the believer in 2:1-2. The sins of believers are forgiven based upon the advocacy and propitiation of Jesus Christ. ... The notion of

[fellowship] in 1:1-4 and 1:5-2:2 does not appear in 2:3-11; rather, the emphasis is upon knowing God and loving God, in addition to the new commandment (2:3-5, 10). The next unit (2:12-14) is transitory, and is addressed to those who do not walk in the Light and further explains what characterizes such fellowship. The next unit (2:15-17) contains the overt command to 'not love the world' for it 'is passing away.' First John 2:12-14 parenthetically contrasts the selfless love that characterizes one who is in the Light (2:7-11) with the selfish love that characterizes the unbelieving world (2:15-17). The intent of 2:18-27 is both expository and hortatory, with much emphasis upon abiding, and concluding with the overt command to abide in God. John's injunctions exhort his readers to abide and mature in the Father and the Son. (Bigalke 2013:40-41)

Acknowledgements

Competing interests

The author declares that he has no financial or personal relationship(s) that may have inappropriately influenced him in writing this article.

References

Akin, D.L., 2001, 1, 2, 3 John, Broadman & Holman, Nashville. [ Links ]

Aland, B., Karavidopoulos, K.J., Martini, C.M. & Metzger, B.M., 1979, Nestle Aland: Novum Testamentum Graece, 26th edn., Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft, Stuttgart. [ Links ]

Allen, D.L., 2010, Hebrews, B & H Publishing, Nashville. [ Links ]

Anderson, J.L., 1992, An exegetical summary of 1, 2 & 3 John, SIL International, Dallas. [ Links ]

Anderson, J.L. & Anderson, J., 1993, 'Cataphora in 1 John', Notes on Translation 7, 43. [ Links ]

Bauer, W., 2001, Greek-English lexicon, University of Chicago Press, Chicago. [ Links ]

Beekman, J., 1981, Semantic structure, SIL International, Dallas. [ Links ]

Bigalke, R.J., 2013, 'Identity of the first epistle of John: Context, style, and structure', Journal of Dispensational Theology 17, 7-44. [ Links ]

Brooke, A.E., 1912, A critical and exegetical commentary on the Johannine epistles, Charles Scribner's Sons, New York. PMid:18735627, PMCid:PMC1894200 [ Links ]

Brown, R.E., 1995, Epistles of John, Yale University Press, New Haven. [ Links ]

Bruce, F.F., 1970, The epistles of John, Eerdmans, Grand Rapids. [ Links ]

Butler, C.S., 2003, Structure and function: A guide to three major structural-functional theories, John Benjamins, Philadelphia. [ Links ]

Callow, J., 1999, 'Where does 1 John 1 end?', in S.E. Porter & J.T. Reed (eds.), Discourse analysis and the New Testament, p. 392-402, Sheffield Academic Press, New York. [ Links ]

Dressler, W.U. (ed.), 1978, Current trends in text linguistics, de Gruyter, Berlin. [ Links ]

Du Rand, J.A., 1991, 'A synchronic and narratological reading of John 10 in coherence with chapter 9', in J. Beutler & R.T. Fortna (eds.), The shepherd discourse of John 10 and its context, pp. 94-112 Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511554865.007 [ Links ]

Erickson, R.J., 2005, A beginner's guide to New Testament exegesis: Taking the fear out of critical method, InterVarsity, Downers Grove. [ Links ]

Fantin, J.D., 2010, The Greek imperative mood in the New Testament, Peter Lang, New York. [ Links ]

Grayston, K., 1984, The Johannine epistles, Eerdmans, Grand Rapids. [ Links ]

Griffith, T., 2002, Keep yourselves from idols: A new look at 1 John, Sheffield Academic Press, New York. [ Links ]

Guthrie, G.H., 1994, The structure of Hebrews: A text-linguistic analysis, Brill, Leiden. [ Links ]

Haas, C., De Jonge, M. & Swellengrebel, J.L., 1972, A translators handbook on the letters of John, United Bible Societies, London. [ Links ]

Hansford, K.L., 1992, 'The underlying poetic structure of 1 John', Journal of Translation and Textlinguistics 5, 126-174. [ Links ]

Hock, A., 2009, 'The Book of Revelation and discourse analysis', paper presented at the inaugural conference of the Monsignor Jerome D. Quinn Institute for Biblical Studies, Saint Paul Seminary School of Divinity, St. Paul, MN, 13 June. [ Links ]

Hoopert, D.A., 2007, 'Verb ranking in Koine imperativals', Journal of Translation 3, 4-5. [ Links ]

Köstenberger, A., 2009, Theology of John's gospel and letters, Zondervan, Grand Rapids. [ Links ]

Kruse, C.G., 2000, The letters of John, Eerdmans, Grand Rapids. [ Links ]

Larsen, I., 1991a, 'Boundary features in the Greek New Testament', Notes on Translation 5, 48-54. [ Links ]

Larsen, I., 1991b, 'Notes on the Function of yáp, oüv, Liév, Sé, eaí, and ié in the Greek New Testament', Notes on Translation 5, 35-47. [ Links ]

Lenski, R.C.H., 1961, The interpretation of I and II epistles of Peter, the three epistles of John, and the epistle of Jude, Augsburg, Minneapolis. [ Links ]

Levinsohn, S.H., 2000, Discourse features of New Testament Greek, 2nd edn., SIL International, Dallas. PMid:10709216, PMCid:PMC2565364 [ Links ]

Longacre, R.E., 1983, 'Exhortation and mitigation in First John', Selected Technical Articles Related to Translation 9, 11. [ Links ]

Longacre, R.E., 1992, 'Exegesis of 1 John', in D.A. Black (ed.), Linguistics and New Testament interpretation, pp. 271-273, B & H Academic, Nashville. [ Links ]

Longacre, R.E., 1996, The grammar of discourse, 2nd edn., Springer, New York. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4899-0162-0 [ Links ]

Malatesta, E., 1973, Epistles of St. John, Pontifical Gregorian University, Rome. Malatesta, E., 1978, Interiority and covenant, Biblical Institute Press, Rome. [ Links ]

Marshall, I.H., 1978, Epistles of John, Eerdmans, Grand Rapids. [ Links ]

Miehle, H., 1981, Theme in Greek hortatory discourse, University Microfilms International, Ann Arbor. [ Links ]

Painter, J., 2002, 1, 2, and 3 John, Liturgical Press, Collegeville. [ Links ]

Petöfi, J.S. (ed.), 1979, Text vs sentence: Basic questions of text linguistics, Helmut Buske, Hamburg. [ Links ]

Porter, S.E., 1999, Idioms of the Greek New Testament, 2nd edn., Continuum, London. [ Links ]

Rogers, E.M., 1984, 'Vocatives and boundaries', Selected Technical Articles Related to Translations 11, 26. [ Links ]

Runge, S.E., 2010, Discourse grammar of the Greek New Testament, Hendrickson, Peabody, MA. [ Links ]

Schnackenburg, R., 1992, The Johannine epistles, transl. R. Fuller & I. Fuller, Crossroad, New York. [ Links ]

Sherman, G.E. & Tuggy, J.C., 1994, A semantic and structural analysis of the Johannine epistles, SIL International, Dallas. [ Links ]

Smith, D.M., 1991, First, second, and third John, Westminster John Knox Press, Louisville. [ Links ]

Strecker, G., 1996, Johannine letters, Augsburg Fortress, Minneapolis. [ Links ]

Titrud, K., 1991, 'The overlooked KAI in the Greek New Testament', Notes on Translation 5, 1-28. [ Links ]

Titrud, K., 1993, 'The function of Kaí in the Greek New Testament and an application to 2 Peter', in D.A. Black (ed.), Linguistics and New Testament interpretation, pp. 240-270, B & H Academic, Nashville. [ Links ]

Van der Merwe, D.G., 2006, 'A matter of having fellowship: Ethics in the Johannine Epistles', in J. van der Watt (ed.), Identity, ethics, and ethos in the New Testament, pp. 537-39, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin. http://dx.doi.org/10.1515/9783110893939.535 [ Links ]

Van der Watt, J., 1999, 'Ethics in First John: A literary and socioscientific perspective', Catholic Biblical Quarterly 61, July, 491. [ Links ]

Van Staden, P.J., 1991, 'The debate on the structure of 1 John', HTS TeologieseStudies/ Theological Studies 47, 487-502. [ Links ]

Watson, D.F., 1989, '1 John 2.12-14 as distributio, conduplicatio, and expolitio: A rhetorical understanding', Journal for the Study of the New Testament 35, January, 97-110. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0142064X8901103507 [ Links ]

Westcott, B.F., 1892, Epistles of St. John, MacMillan, London. PMCid:PMC2420916 [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Ron Bigalke

PO Box 244, Rincon, GA 31326-0244, United States of America

Email: r.j.bigalke@alumni.moody.edu

Received: 18 June 2013

Accepted: 14 August 2013

Published: 04 Nov. 2013

Note: Dr Ron J. Bigalke is a research associate and was a doctoral student of Prof. Dr Jacobus (Kobus) Kok in the Department of New Testament Studies, University of Pretoria. His article represents a reworked version of aspects from the approved PhD dissertation (University of Pretoria, April 2013), with Prof. Kok as supervisor.

1. Semantic-structural analysis is not superior to other hermeneutical methodologies, especially historical-grammatical interpretation; rather, it is necessary to demonstrate fundamental language functions and text structures.

2. Kruse (2002:32) wrote similarly: 'The analysis of 1 John ... does not seek to trace any developing argument throughout the letter because there isn't one.'