Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

HTS Theological Studies

versión On-line ISSN 2072-8050

versión impresa ISSN 0259-9422

Herv. teol. stud. vol.69 no.1 Pretoria ene. 2013

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Constructing ancient slavery as socio-historic context of the New Testament

Hendrik Goede

Unit for Reformed Theology, Potchefstroom Campus, North-West University, South Africa

ABSTRACT

Considering the vast scope of material on slavery in antiquity, this article aimed to design a search filter that delimits the scope of socio-historical aspects specifically relevant to the New Testament passages dealing with slavery. The term 'search filter' was borrowed from Information Technology, denoting defined search terms aimed at more efficient and effective searches of vast amounts of data. The search filter designed in this article made use of the following search terms: the period under investigation; the geographical region under investigation; various definitions of slavery; ancient terminology for slavery; and aspects arising from the New Testament passages themselves. Each of these criteria were considered in turn, and the results were used to define the search filter. Finally, the search filter was represented schematically.

Introduction

When constructing the socio-historic context of the New Testament passages referring to slavery1, the researcher is faced with an avalanche of both primary and secondary source material. Secondary works on Greco-Roman slavery2 can be categorised as seen in Table 1.

This categorisation illustrates the vast scope of available material. Yet not all of this material is necessarily relevant to the interpretation of the New Testament passages referring to slavery. The same applies to an even greater extent to the Greek, Latin, Hebrew and Aramaic primary sources available to the researcher interested in ancient slavery. This article aims to define a search filter to delimit the available material on Greco-Roman slavery to those aspects of slavery that may constitute the socio-historical context of the New Testament passages referring to slavery.

The concept of a search filter is well known in Information Technology as a method to provide more efficient and effective searches of vast amounts of data. The main crux of developing a successful search filter is identifying potentially useful search terms (Jenkins 2004:155). Such terms may be defined with regard to time (e.g. dates), language (e.g. grammatical forms or key words), geography (e.g. place), or any other relevant aspect. For purposes of the search filter defined in this article, the following search terms will be considered, namely, the period under investigation; the geographical region under investigation; various definitions of slavery; ancient terminology for slavery; and aspects arising from the New Testament passages themselves. The article concludes with a schematic representation of the findings.

Period under investigation

One might assume that the relevant period to be studied would be limited to the events narrated by the New Testament in so far as they relate to the topic of slavery, namely approximately 29 BCE (the start of Jesus' public ministry) to approximately 180 CE (to allow for earlier or later dating of the New Testament writings) (cf. Van der Watt 2003:584-585). Considering the pitfalls in the dating of the available evidence,3 the following grounds substantiate a broader period of investigation:

- The confluence of Greek and Roman traditions and customs in the time of the New Testament merits the inclusion of Greek slavery in the search filter. This would extend the beginning of the period of investigation to the classical Athenian period (c. 480-330 BCE) (Hornblower 2003:651-652).

- The influence of Jewish tradition in New Testament times merits the extension of the period of investigation to the rabbinic period (c. 70-200 BCE) (Goodman 2003:1292).

- The codification of the most important sources of Roman law took place during the reign of Justinian in approximately 535 CE (Johnston 1999:14ff.).

Thus the first search term of the search filter is defined as the period from approximately 480 BCE to approximately 535 CE.

Geographical region under investigation

The New Testament texts concerning slavery point to various geographical areas of interest for example Palestine, Asia Minor, Greece, Italy, North Africa and Spain (Du Plessis 1998:34). The specific passages under investigation provide geographical references according to where the events described took place and the addresses of the addressees (see Table 2).

The geographical focus of the New Testament passages under investigation is thus Palestine, Asia Minor, Achaia, and Crete. The second search term of the search filter is defined accordingly.

Definitions of slavery

The socio-historical approach described by Harrill (1998:4-6) and Janse van Rensburg (2000) are followed in determining the socio-historic contexts of the passages to be researched.

According to this approach, the events described in the text are perceived as interwoven with the social and political realities of the time (Janse van Rensburg 2000:567). It presupposes an emic approach, namely that data and phenomena are described in terms of its functions in ancient society, rather than in terms of modern theories and models (an etic approach) (Janse van Rensburg 2000:569-570). The aim is thus to construct the typical situations in which early Christians lived by allowing the text to present the categories, et cetera, rather than to use modern abstractions on ancient texts (Harrill 1998:5). Such an approach does not, however, completely ignore the contributions of modern historians, sociologists, and ethicists building history 'from the ground up' (Harrill 1998:6).

There is currently no general theory of slavery that allows a single definition of slavery for all cultures and times (Garlan 1988:24; Harrill 1998:14). Slavery is colloquially understood to refer to the buying, selling and owning of human beings as mere objects. Yet the matter is far more complex. No legal and coherent definition of slavery can be found in Greek sources, probably because of the absence of jurisprudence (Zelnick-Abramovitz 2005:35). A survey of the evidence suggests that any attempt to detect such a definition is futile. Freedom and slavery (or 'unfreedom') should rather be seen as concepts relative to one another based on dependence or independence (Zelnick-Abramovitz 2005:38).

Definitions found in Aristotle and Roman private law declare a slave to be property that is essentially no different from a farm implement or domesticated animal (Harrill 1998:14).

Such legal definitions must, however, be approached with circumspection since the law only provides inexact knowledge about social practice. Rabbinic sources share the fundamental ambiguity of Roman law with regard to the legal definition of slavery: slaves are perceived as mere objects, yet as human beings responsible for their actions (Hezser 2005:63). The classification of slaves as property is implied in rabbinic sources but rarely stated explicitly. According to the Mishnah, slaves are defined as persons subject to a householder's (owner's) full control (Flesher 1988:102-103). The slave's inherent features, namely being male and having the full power of reason, have no bearing on his classification as slave.

In the narrow sense, 'slave' can refer to chattel slaves of the classical Athenian type (De Sainte Croix 1981:133; Garlan 1988:201). In the broad sense it includes 'all types of legally defined personal dependency to which the Greeks sometimes referred as δουλεία' (Garlan 1988:201). De Sainte Croix (1981:134-136) refers to this broad sense as 'unfree labour' being 'the extraction of the largest possible surplus from the primary producers.' One must, however, recognise that these categories were not used by the Greeks and Romans since they divided humankind into two groups, namely free and slave, among other distinctions. There is no doubt that in the Greek and Roman world, chattel slavery was the dominant form of unfree labour (De Sainte Croix 1981:173).

Whilst the abovementioned definitions of chattel slavery focus on its legal foundation,4 alternative definitions emphasise other aspects common to most forms of chattel slavery. Patterson (1982) defines slavery in terms of power relations. The following aspects are inherent in every power relation (Patterson 1982:1-2):

- The social aspect, namely the use or threat of violence in the control of one person by another.

- The psychological aspect of influence, namely the capacity to persuade another person to change the way he perceives his interests and circumstances.

- The cultural aspect of authority, namely the means of transforming force into right and obedience into duty.

Applying these principles to slavery, it may be defined as 'the permanent, violent domination of natally alienated and generally dishonoured persons' (Patterson 1982:13). Slavery is (except in the case of manumission) a life-long state of being violently dominated and dishonoured with no birthrights and no sense of belonging (Fisher 1993:5-6). Ultimately, slavery could mean social death (Patterson 1982:5).

Read together, these two definitions of chattel slavery, the one legal and the other social, emphasise the completeness of the power exercised by slave-owners and the dishonour and disorientation inflicted on slaves (Fisher 1993:6). Wiedemann (1987) attempts to combine these elements into one definition:

The slave was someone who had lost, or never had, any rights to share in society, and therefore to have access to food, clothing, and the other necessities of physical survival. (p. 22)

Chattel slavery thus was (and is) a multifaceted social phenomenon that must be defined and studied in terms of its legal and social foundations and consequences. The third search term defining the search filter is thus chattel slavery.

Ancient terminology for slavery

A comparison of Greek, Latin, Hebrew and Aramaic terminology with regard to slavery may provide guidelines with regard to shared socio-historic contexts, since words are generally used and borrowed within their contemporary socio-cultural environment (Wright 1998:84, 107). This becomes especially apparent in the Jewish-Greek biblical translations.

Greek terminology

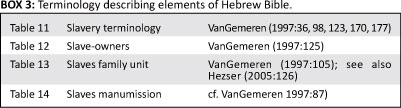

The basic terminology describing slavery (Tables 3-6) in ancient Greece was extremely complex and generally ambiguous (Garlan 1988:20; Fisher 1993:6-7). This complexity and ambiguity came about because of the borrowing of terms from traditional systems of dependency such as the household and the family, and continued into the Hellenistic period despite the fixed juridical definitions that existed at that time. Terminology describing slavery in Greek literature must thus be considered strictly contextually (Box 1).

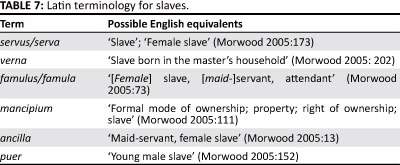

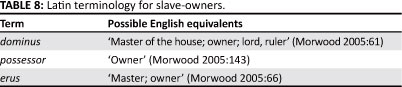

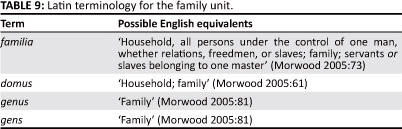

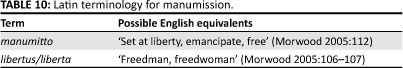

Latin terminology

In Tables 7-10 the Latin literature describes slavery terminology (Box 2).

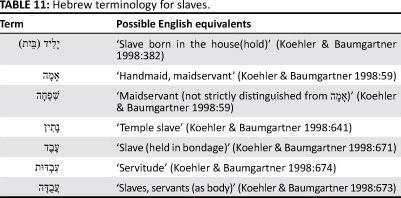

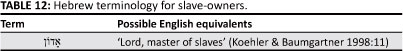

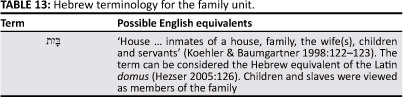

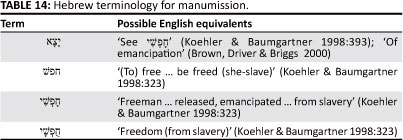

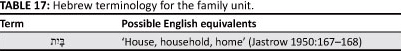

Hebrew terminology

Jewish involvement in the Hellenistic-Roman world meant an assimilation of Graeco-Roman practices and Greek and Latin terms for slaves and slavery (Wright 1998:84). This process involved a transformation of the Hebrew Bible's notion of servanthood.

Words signifying slaves (Box 3) occur in patriarchal stories, law codes, historical narratives, prophetic revelations and wisdom literature in the Hebrew Bible (Flesher 1988:12) and presented in Tables 11-14.

refers to any subservient relationship and does not necessarily imply ownership (Wright 1998:85; Bartchy 1992:62). It is used for both Hebrew and foreign slaves although the latter were treated to some extent as property. In the vast majority of cases

refers to any subservient relationship and does not necessarily imply ownership (Wright 1998:85; Bartchy 1992:62). It is used for both Hebrew and foreign slaves although the latter were treated to some extent as property. In the vast majority of cases  is rendered δοΰλος or παις in the Septuagint with a distinct preference for the latter in the

is rendered δοΰλος or παις in the Septuagint with a distinct preference for the latter in the

Pentateuch (Wright 1998:90-92). Οΐκέτης and θεράπων are also used and all these terms are used as synonyms or at least seem interchangeable.

Josephus prefers the term δοΰλος referring to chattel slaves (Wright 1998:98). He also uses other Greek words not used in the Septuagint, namely άνδράποδον and αιχµάλωτος. Again, all these words seem to be used as synonyms. A striking feature of Josephus's writing is however his decreasing use of παις as meaning 'slave' even in contexts generally referring to slavery (Wright 1998:100). Philo follows roughly the same pattern with δοΰλος dominating, and other terms used as synonyms for it (Wright 1998:102). Philo employs παις as a play on its meanings of 'slave' and 'child' (Wright 1998:104105). Also in the Apocrypha and Pseudepigrapha, slave terms are used interchangeably without any clear distinctions even in religious contexts (Wright 1998:107). One may conclude that the Jews in the Second Temple Period used Greek slave terms as they were used in their socio-cultural environment (Wright 1998:108).

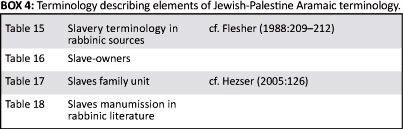

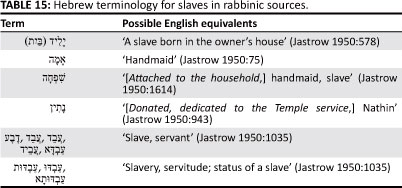

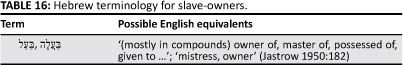

Jewish-Palestine Aramaic terminology

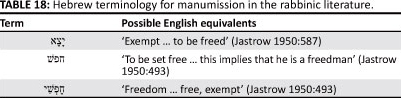

Tannaitic and Amoraic rabbinic documents are especially relevant to Jews and slavery in antiquity (Hezser 2005:14).5

Thus an examination of Jewish-Palestine Aramaic terminology (Box 4) relating to slavery is necessary and is presented in Table 15-18.

Summary

The Greek and Latin terminology clearly refer to chattel slavery as defined above. The Jewish terminology also conforms to this during the time of the New Testament despite legacies from the Old Testament laws on slavery. This is also reflected in the rabbinic literature. Thus the fourth search filter is defined as the Greek, Latin, Hebrew, and Aramaic terminology listed above.

Aspects arising from the New Testament passages

A perfunctory reading of the relevant New Testament passages6 suggests that the following socio-historic delimitations can be utilised:

- Slavery in the New Testament is delimited to urban or domestic slavery based on the inclusion of the exhortations directed at slave-owners in the household codes (Eph 6:9; Col 4:1). One might also assume a primarily urban audience in the urban Christian congregations of the New Testament.

- The use of the following terms for slavery, παις, δούλος, οίκέτης and their Latin, Hebrew and Aramaic equivalents.

- The use of the following terms for slave-owners: κύριος, δεσπότης and their Latin, Hebrew, and Aramaic equivalents.

- The relationship between slave-owner and slave indicated by the owner's treatment of his slave(s) (Mt 8:5-13; 10:2425; Ac 12:13-16; Eph 6:5-8, 9; Col 3:22-25, 4:1; 1 Tm 6:1-2b; Tt 2:9-10; Phlm 1-25; 1 Pt 2:18-25).

- The slave's economic usefulness and loyalty towards his owner (Mt 24:45-51; 25:14-30; Lk 16:1-8).

- The slave as a member of the owner's household (Jn 8:35).

- The slave's participation in their master's or their own religious activities (Phlm 1-25).

- Manumission of slaves by their owners (1 Cor 7:21-23).

Conclusion

The aim of this article was to define a search filter to delimit the available material on Greco-Roman slavery to those aspects of slavery that constitute the socio-historical context to the New Testament passages referring to slavery. Five search terms were defined, namely, the period under investigation; the geographical region under investigation; various definitions of slavery; ancient terminology for slavery; and aspects arising from the New Testament passages themselves. Applying these search terms, a useful search filter will consist of the following elements:

- Domestic chattel slavery as defined in paragraph 4:

■ during the period 480 BCE - 535 CE

■ in Palestine, Asia Minor, Achaia, and Crete

■ indicated by commonly used vocabulary, δούλος, οίκέτης, παις, κύριος, δεσπότης, οίκος, servus, verna, dominus, familia,

,

,  and

and  (including related forms in Hebrew and Aramaic)

(including related forms in Hebrew and Aramaic)■ delimited by the aspects highlighted by the New Testament passages to be studied, namely the legal, economic, social-familial, and religious relationship between slave-owner and slave with the emphasis on the rights and duties of the slave-owner in such relationship.

This search filter is schematically represented (see Figure 1).

Practically speaking, one would survey the available material through the lens of the search filter. A book or journal paper on slavery must therefore deal with slavery during the period 480 BCE - 535 CE in the regions of Palestine, Asia Minor, Achaia and Crete with reference to legal, economic, social-familial and religious relationship between slave-owner and slave. In ancient sources the vocabulary identified as relevant search terms must be present (made easier by computerised versions of these sources for example the Thesaurus Linguae Graecae [TLG]). Thus, by way of illustration, material on American and colonial slavery would be excluded by the application of the search filter but material dealing with the social-familial relations of slaves in Ephesus in the 1st century would be included.

Acknowledgements

Competing interests

The author declares that he has no financial or personal relationship(s) which may have inappropriately influenced him in writing this article.

References

Barrow, R.H., 1928, Slavery in the Roman Empire, Barnes & Noble, New York. PMid:18740856, PMCid:1656088 [ Links ]

Bartchy, S.S., 1973, First-century slavery and the interpretation of 1 Corinthians 7, 21, Scholars Press, Atlanta. (Society of Biblical Literature Dissertation Series, 11). [ Links ]

Bartchy, S.S., 1992, 'Slavery (New Testament)', in D.N. Freedman (ed.), Anchor Bible Dictionary, vol. 6, pp. 58-73, Doubleday, New York. [ Links ]

Beavis, M., 1992, 'Ancient slavery as an interpretative context for the New Testament servant parables with special reference to the unjust steward (Luke 16:1-8)', Journal of Biblical Literature 111(1), 37-54, viewed 03 July 2012, from http://ehis.ebscohost.com.nwulib.nwu.ac.za/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer? sid=9fb59180-c078-4fb8-aca2-226e807f1f80%40sessionmgr113&vid=2&hid=110 [ Links ]

Bietenhard, H., 1976, s.v. 'Lord, Master', in C. Brown (ed.), New International Dictionary of New Testament Theology, Paternoster Press, Exeter, vol. 2, p. 520. [ Links ]

Bradley, K.R., 1987, Slaves and masters in the Roman Empire: A study in social control, Oxford University Press, Oxford. [ Links ]

Bradley, K.R., 1989, Slavery and rebellion in the Roman world, 140 B.C.-70 B.C., Indiana University Press, Bloomington. [ Links ]

Bradley, K.R., 1994, Slavery and society at Rome: Key themes in Ancient history, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. [ Links ]

Brown, C. (ed.), 1976-1978, New International Dictionary of New Testament Theology, Paternoster Press, Exeter, vol. 3, pp. 589-599. [ Links ]

Brown, F., Driver, S.R. & Briggs, C., 2000, Enhanced Brown-Driver-Briggs Hebrew and English Lexicon, CD-ROM, Logos Research Systems, Oak Harbor. [ Links ]

Callahan, A.D., Horsley, R.A. & Smith, A., 1998, 'Introduction: The slavery of New Testament Studies', in A.D. Callahan, R.A. Horsley & A. Smith (eds.), Slavery in text and interpretation, pp. 1-15, Society of Biblical Literature, Atlanta. (Semeia 83/84). PMid:9631950 [ Links ]

Crook, J.A., 1984, Law and life of Rome, 90 B.C.-A.D. 212, Cornell University Press, New York. [ Links ]

Davies, M., 1995, 'Work and slavery in the New Testament: Impoverishments of traditions', in J.W. Rogerson, M. Davies & M.D.R. Carroll (eds.), The Bible in ethics: The Second Sheffield Qolloquium, pp. 315-347, Sheffield Academic Press, Sheffield. PMCid:1001465 [ Links ]

De Sainte Croix, G.E.M., 1981, The class struggle in the ancient Greek world from the Archaic Age to the Arab conquests, Cornell University Press, Ithaca. [ Links ]

De Wet, C.L., 2010, 'Sin as slavery and/or slavery as sin? On the relationship between slavery and Christian hamartiology in late Ancient Christianity', Religion & Theology 17(1/2), 26-39, viewed 03 July 2012, from http://ehis.ebscohost.com.nwulib.nwu.ac.za/ehost/pdfviewer/ pdfviewer?sid=6496dc87-d146-4e53-93a0-16ec627bfdf2%40sessionmgr15&vid=2&hid=8 [ Links ]

Drescher, S. & Engerman, S.L. (eds.), 1998, A historical guide to world slavery, Oxford University Press, Oxford. [ Links ]

Du Plessis, I.J., 1998, 'Getting to know the geography, topography and archaeology of the Bible Lands in New Testament times', in A.B. du Toit (ed.), Guide to the New Testament, vol. II: The New Testament milieu, pp. 32-85, Orion Publishers, Halfway House. [ Links ]

Finley, M.I., 1980, Ancient slavery and modern ideology, Penguin Books, London. [ Links ]

Fisher, N.R.E., 1993, Slavery in classical Greece, Bristol Classical Press, Bristol. (Classical World Series). [ Links ]

Flesher, P.V.M., 1988, Oxen, women, or citizens? Slaves in the system of the Mishnah, Scholars Press, Atlanta. (Brown Judaic Studies, 143). PMCid:202606 [ Links ]

Garlan, Y., 1988, Slavery in Ancient Greece, transl. J. Lloyd, Cornell University Press, London. [ Links ]

Garnsey, P., 1996, Ideas of slavery from Aristotle to Augustine, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. [ Links ]

Glancy, J.A., 2006, Slavery in early Christianity, Fortress Press, Minneapolis. [ Links ]

Goetzmann, J., 1976, 'House, build, manage, steward', in C. Brown (ed.), New International Dictionary of New Testament Theology, Paternoster Press, Exeter, vol. 2, pp. 247-256. [ Links ]

Goodman, M.D., 2003, s.v. 'Rabbis', in S. Hornblower & A. Spawforth (eds.), The Oxford Classical Dictionary, 3rd edn. rev., Oxford University Press, Oxford, p. 1292. [ Links ]

Harrill, J.A., 1998, The manumission of slaves in early Christianity, 2nd edn., Mohr Siebeck, Chicago. [ Links ]

Harrill, J.A., 2006, Slaves in the New Testament: Literary, social and moral dimensions, Fortress, Minneapolis. [ Links ]

Harvey, M., 2001, 'Deliberation and Natural Slavery', Social Theory & Practice 27(1), 41-64, viewed 03 July 2012, from http://ehis.ebscohost.com.nwulib.nwu.ac.za/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?sid=d0ed4372-a6d6-42e7-b82c-3e183cef0976%40s essionmgr10&vid=2&hid=8 [ Links ]

Hezser, C., 2005, Jewish slavery in antiquity, Oxford University Press, Oxford. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199280865.001.0001 [ Links ]

Hornblower, S., 2003, 'Greece (prehistory and history, Archaic, Classical, Hellenistic)', in S. Hornblower & A. Spawforth (eds.), The Oxford Classical Dictionary, 3rd ed. rev., Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp. 649-652. [ Links ]

Janse van Rensburg, J.J., 2000, 'Dékor of konteks? Die verdiskontering van sosio-historiese gegewens in interpretasie van 'n Nuwe Testament-teks vir die prediking en pastoraat, geïllustreer aan die hand van die 1 Petrus-brief', Skrif en Kerk 21, 564-582. [ Links ]

Jastrow, M., 1950, A dictionary of the Targumin, the Talmud Babliand Yerushalmi, and the Midrashic literature, 2 vol., Pardes Publishing House, New York. [ Links ]

Jenkins, M., 2004, 'Evaluation of methodological search filters - A review', Health Information & Libraries Journal 21(3), 148-163, viewed 03 July 2012, from http://ehis.ebscohost.com.nwulib.nwu.ac.za/ehost/pdfviewer /pdfviewer?sid=4141949d-8308-4622-af0c-b7f6d04aadb6%40sessionmgr11&vid =2&hid=8 [ Links ]

Johnston, D., 1999, Roman law in context, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511612138 [ Links ]

Joshel, S.R. & Murnaghan, S. (eds.), 2001, Women and slaves in Greco-Roman culture: Differential equations, Routledge, London. [ Links ]

Koehler, L. & Baumgartner, W. (eds.), 1998, A bilingual dictionary of the Hebrew and Aramaic Old Testament: English and German, Brill, Leiden. [ Links ]

League of Nations, 1926, Slavery convention signed at Geneva on 25 September 1926, League of Nations, Geneva. [ Links ]

Liddell, H., Scott, R., Jones, H.S. & McKenzie, R. (eds.), 1996, A Greek-English lexicon, with a rev. suppl., CD-ROM, Clarendon Press, Oxford. [ Links ]

Marchal, J.A., 2011, 'The usefulness of an onesimus: The sexual use of slaves and Paul's Letter to Philemon', Journal of Biblical Literature 130(4), 749-770, viewed 03 July 2012, from http://ehis.ebscohost.com.nwulib.nwu.ac.za/ehost/pdfviewer/ pdfviewer?sid=19b975f2-6b04-4d3f-a6f9-8381c7290118%40session mgr115&vid=2&hid=105 [ Links ]

Massey, M. & Moreland, P., 1992, Slavery in Ancient Rome, Thomas Nelson & Sons, Surrey. [ Links ]

Morwood, J., 2005, Pocket Oxford Latin Dictionary, Oxford University Press, Oxford. [ Links ]

Patterson, O., 1982, Slavery and social death: A comparative study, Harvard University Press, Cambridge. [ Links ]

Phillips, W.D., 1996, 'Continuity and change in Western slavery: Ancient to modern times', in M.L. Bush (ed.), Serfdom and slavery: Studies in legal bondage, pp. 7188, Addison Wesley Longmann, London. [ Links ]

Robinson, O.F., 1997, The sources of Roman law: Problems and methods for ancient historians, Routledge, London. [ Links ]

Saller, R., 1996, 'The hierarchical household in Roman society: A study of domestic slavery', in M.L. Bush (ed.), Serfdom and slavery: Studies in legal bondage, pp. 112-129, Addison Wesley Longmann, London. [ Links ]

Sherwin-White, A.N., 1963, Roman society and Roman law in the New Testament, Clarendon Press, Oxford. [ Links ]

Sherwin-White, A.N., 1967, Racial prejudice in imperial Rome, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. [ Links ]

Turley, D., 2000, Slavery, Blackwell Publishers, Oxford. [ Links ]

VanGemeren, W.A. (ed.), 1997, New International Dictionary of Old Testament Theology and Exegesis, vol. 5, Zondervan Publishing House, Grand Rapids. [ Links ]

Van der Watt, J. (ed.), 2003, Die BybelA-Z, CUM, Vereeniging. [ Links ]

Vlassopoulos, K., 2011, 'Greek Slavery: from Domination to Property and back again', Journal of Hellenic Studies 131, 115-130, viewed 03 July 2012, from http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S0075426911000085 [ Links ]

Vogt, J., 1974, Ancient slavery and the ideal of man, transl. T. Wiedemann, Basil Blackwell, Oxford. [ Links ]

Watson, A., 1998, Ancient law and modern understanding: At the edges, University of Georgia Press, Athens. [ Links ]

Westermann, W.L., 1955, The slave systems of Greek and Roman antiquity, The American Philosophical Society, Philadelphia. [ Links ]

Wiedemann, T.E.J., 1981, Greek and Roman slavery, Routledge, London. http://dx.doi.org/10.4324/9780203358993, PMCid:181439 [ Links ]

Wiedemann, T.E.J., 1987, Slavery, Clarendon Press, Oxford. (New Surveys in the Classics, 19). [ Links ]

Wright, B.G., 1998, 'Ebed/doulos: Terms and social status in the meeting of Hebrew Biblical and Hellenistic Roman Culture', in A.D. Callahan, R.A. Horsley & A. Smith (eds.), Slavery in text and interpretation, pp. 83-111, Society of Biblical Literature, Atlanta. (Semeia 83/84). [ Links ]

Zelnick-Abramovitz, R., 2005, Not wholly free: The concept of manumission and the status of manumitted slaves in the ancient Greek world, Brill, Leiden. (Mnemosyne Supplementa, 266). [ Links ]

Correspondence to:

Correspondence to:

Hendrik Goede

PO Box 264311

Three Rivers 1935, South Africa

Email: hennie.goede@nwu.ac.za

Received: 04 July 2012

Accepted: 24 Feb. 2013

Published: 25 Apr. 2013

Note: This article represents a version of a chapter from the author's PhD thesis with the title 'The exhortations to slave-owners in the New Testament: A philological study'.

1. The passages under investigation are limited to those referring to actual slavery to the exclusion of those using slavery as a metaphor. Although the final search filter may also be useful in the interpretation of the latter passages, the metaphoric use may in itself delimit the relevant socio-historic context even further. The passages referring to actual slavery are: Matthew 8:5-13; 10:24-25; 24:45-51; 25:14-30; Luke 16:1-8; John 8:35; Acts 12:13-16; 1 Corinthians 7:21-23; Ephesians 6:5-8, 9; Colossians 3:22-25, 4:1; 1 Timothy 6:1-2b; Titus 2:9-10; Philemon 1-25; 1 Peter 2:18-25.

2. For purposes of this article, I limited computer-based database searches to sources referring to the period starting with the origin of the New Testament, that is, approximately 49 BCE until approximately 95 CE (cf. Van der Watt 2003:592-593).

3. See, for example, Crook (1984:9-13), Wiedemann (1987:11-21), Robinson (1997:102-103), Harrill (1998:30), Watson (1998:1-4) and Johnston (1999:24-29).

4. Modern definitions of slavery also focus on its legal aspect. The United Nations, for example, defines chattel slavery as 'the status or condition of a person over whom any or all of the powers attaching to the right of ownership are exercised' (League of Nations 1926).

5. Tannaitic writings contain traditions dating from the 1st and 2nd centuries CE whilst Amoraic writings contain traditions dating from the 3rd to 5th centuries CE (Hezser 2005:14 fn. 57).

6. Matthew 8:5-13; 10:24-25; 24:45-51; 25:14-30; Luke 16:1-8; John 8:35; Acts 12:13-16; 1 Corinthians 7:21-23; Ephesians 6:5-8, 9; Colossians 3:22-25, 4:1; 1 Timothy 6:1-2b; Titus 2:9-10; Philemon 1-25; 1 Peter 2:18-25.