Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

HTS Theological Studies

On-line version ISSN 2072-8050

Print version ISSN 0259-9422

Herv. teol. stud. vol.69 n.1 Pretoria Jan. 2013

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Why Old Testament prophecy is philosophically interesting

Jacobus W. Gericke

Faculty of Humanities, North-West University, Vaal Triangle Campus, South Africa

ABSTRACT

Comparative philosophical perspectives on Old Testament predictive prophecy are rare. Yet whilst the Old Testament is not explicit in its views on the relation between God and time, its narratives do contain implicit metaphysical assumptions regarding the nature of divine foreknowledge. In this article the author listed a standard variety of possible perspectives on how one might construe the way in which YHWH as depicted in Genesis 15:12-16 was thought of with regard to his knowledge of the future, if any. Not opting for any particular view on the matter, especially given that most are anachronistic, the implications and problems of each are noted to show why Old Testament prophecy can also be philosophically interesting.

The desire for 'freedom of will' in the superlative, metaphysical sense, such as still holds sway, unfortunately, in the minds of the half-educated, the desire to bear the entire and ultimate responsibility for one's actions oneself, and to absolve God, the world, ancestors, chance, and society therefrom, involves nothing less than to be precisely this causa sui, and, with more than Munchausen daring, to pull oneself up into existence by the hair, out of the slough of nothingness. (Nietzsche 2002:42)

Introduction

Philosophical perspectives on prophecy are rare. According to Davison (2010) under the entry on 'Prophecy' the following is noted:

In the usual sense, prophecy involves disclosing some important information that could not have been known to the prophet in any ordinary way. Prophecy is interesting from a philosophical point of view because it introduces interesting questions about divine knowledge, time, and human freedom. Unlike historians or theologians, philosophers rarely argue about what kinds of things have actually been prophesied, or whether or not a given prophecy came true. Instead, they prefer to argue about ideal cases, where the theoretical issues become much more sharp. (n.p.)

When philosophers of religion discuss the subject of prophecy they are typically interested in predictions that concern the contingent future (Geach 2001; Davison 2010:n.p.) A future event is assumed to be contingent if and only if it was assumed to be possible for it to either happen or not happen. Special philosophical issues are raised by this kind of prophecy since Christian philosophy of religion imagines a prophet predicting that some future contingent event will occur based upon the revelation of God. And since it is assumed that God is infallible, the question is whether it follows that the future contingent event must inevitably occur? And if it must occur, how can it be a contingent event? According to Davison (2010), the following biblical instance suffices to illustrate the philosophical problematic surrounding predictive prophecy:

An especially vivid example of this kind of situation comes from the Christian scriptures. Jesus prophecies that Peter will deny him three times before the cock crows (see Matthew 26:34). Typically, we would think of Peter's denial as a free act, and hence as a contingent event. But since Jesus cannot be mistaken (according to Christian theology), how are Peter's later denials free? Once Jesus' words become part of the unalterable past, don't they guarantee a particular future, whether or not Peter is willing to cooperate? (n.p.)

This kind of problem is part of a more general philosophical riddle regarding the compatibility of God's complete foreknowledge with the existence of future contingent events. However:

[w]hereas the more general question about God's foreknowledge typically involves just God's knowledge and the future contingent event, the problem of prophecy involves a third element, namely, the prophecy itself, which becomes a part of the past history of the world as soon as it is [uttered]. This additional element adds an interesting twist to the general problem, making it more difficult to solve. (Davison 2010:n.p.)

Old Testament prophecy

It may be difficult for many Old Testament scholars in particular, to see a place for this type of philosophical topic in the practise of biblical criticism (see Barr 1999:146). But why should there be a problem? Let us imagine a text in the Old Testament in which it is prophesied that some future contingent event will occur. Since the theology of the narrator likely assumed that YHWH could not be wrong, a perfectly legitimate question arises: did it follow that the future contingent event was believed to be inevitable from the perspective of characters inside the world in the text? And if so, did they assume that the contingent event was co-created by human free will? Is it somehow exegetically out of line to ask such questions?

To be sure, from a historical-critical perspective, these philosophical concerns can seem out if place. First of all, Old Testament prophecies were often ex-eventu post-dictions, so technically there was no actual prediction about a future state of affairs. Secondly, since the Old Testament itself does not seem to show any concern for explicating philosophical problems related to biblical prophecy, putting such questions to the text will simply seem exegetically misplaced. However this is not the case from a literary-historical perspective. For whilst the Old Testament is not philosophical in nature, the prophecies in the world in the text contain nascent metaphysical assumptions about the nature of divine foreknowledge, the deity's relation to time and human freedom, whether the authors were aware of holding these or not. These 'folk'-philosophical presuppositions are bracketed in existing methods in biblical criticism and are in need of descriptive philosophical clarification. This can even be seen as part of a historical approach since only so can we begin to understand the metaphysical building blocks of the world views behind ancient Israelite prophecy.

A philosophical approach to Old Testament prophecy can be seen as part of a literary-historical approach as long as it limits itself to the clarification of meaning of the unwritten metaphysical beliefs operative in the world in the text itself. Unlike is the case in philosophy of religion proper, such philosophical exegesis is not aimed at discovering what is really real in the world behind or in front of the text. It involves descriptive philosophy of religion and is concerned with the character of YHWH and the building blocks of his world as literary constructions only.

An example of predictive prophecy in Genesis 15

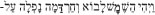

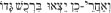

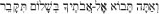

Our philosophical analysis of a predictive prophecy in the Old Testament will concern itself with the text of Genesis 15:12-16. We pick up the scene with this pericope's version of YHWH revealing to the character Abraham what the latter can expect with regard to the future of his life and those of his descendants:

And it came to pass, that, when the sun was going down, a deep

And it came to pass, that, when the sun was going down, a deep

sleep fell upon Abram; and behold, a dread, a great darkness, fell

sleep fell upon Abram; and behold, a dread, a great darkness, fell

upon him.

upon him.

And He said to Abram: 'Know for sure that your seed shall be

And He said to Abram: 'Know for sure that your seed shall be

a stranger in a land that is not theirs, and shall serve them; and they

a stranger in a land that is not theirs, and shall serve them; and they

shall afflict them four hundred years;

shall afflict them four hundred years;

and also that nation, whom they shall serve, will I judge; and

and also that nation, whom they shall serve, will I judge; and

afterward shall they come out with great substance.

afterward shall they come out with great substance.

But you shall go to your fathers in peace; you shall be buried in a

But you shall go to your fathers in peace; you shall be buried in a

good old age.

good old age.

And in the fourth generation they shall come back hither; for the

And in the fourth generation they shall come back hither; for the

iniquity of the Amorite is not yet full.'

iniquity of the Amorite is not yet full.'

What is somewhat atypical in this text is that it is YHWH rather than a prophet who makes the overt prediction. Hence we are dealing with the philosophical problem of divine revelation as much as with that of prophecy. A closer look at the various propositions included in the prediction reveals the following:

1. Abraham will have descendants.

2. Abraham will live to a ripe old age and die in peace.

3. Abraham's descendants will go to and stay in Egypt.

4. Abraham's descendants will be oppressed.

5. The descendants will leave Egypt in the fourth generation.

6. The Amorites will have filled their iniquity only then.

And so YHWH revealed to Abraham both his own future fate and some general details concerning the events surrounding the Israelites' sojourn into Egypt, the Exodus and the conquest of the land. The folk-metaphysical assumptions regarding the relation between divine foreknowledge and human free will in this prophecy seem obscure and difficult to reconstruct. For example, it is hard to tell whether the outcomes were assumed to be wholly dependent on YHWH or also partly on fate in relation to which YHWH was portrayed as acting merely in the role of a catalyst (see vv. 14, 16). Indeed, it would seem that, according to this text at least, YHWH had to wait for the scales of justice to tip before he could act (v. 16). If this is the case the text presupposes the existence of a moral order beyond the deity on which his providence is dependent. This idea is familiar in the ancient Near East where the gods themselves are subject to even more transcendental realities that determine even their actions. It is hardly the stuff of orthodox Judaeo-Christian belief today, yet we must remember that also with regard to prophecy the Old Testament might not always agree with what is considered proper or credible in modern philosophical theology.

Another philosophical question generated by the passage concerns the way in which YHWH was assumed to know the future. In this regard, there seem to be two possible perspectives in Genesis 15:12-16, although it makes a huge difference to our understanding which one we choose:

1. YHWH knew the future not because he controlled it but because he could foresee how it would unfold by itself.

2. YHWH knew the future because he was in control and knew what he wanted to do in the time to follow.

These two distinctions in the way the future could be known by the deity may be something the text had no explicit notion of, yet at least one of these must be implicit in or follow logically from the discourse. If we choose the former, YHWH himself seems to have neither free will nor omnipotence. If we choose the second, a strange form of providence is required: YHWH had to keep Abraham's descendants alive, get them to Egypt, get Pharaoh to oppress them, prevent them from leaving before the fourth generation, and had to get the Amorites to stay evil and for the evil to fill some sort of scale in an assumed moral order at exactly that time (cf. Clines 1995:195). Abraham and company may have been assumed to be free agents, yet their future also seems fixed. Curiously, the narrative implies that Abraham had free will yet was not free to commit suicide there and then, for otherwise he would then not have had children or grow old and everything YHWH had just predicted would prove to have been false. Can we reconcile these anomies of ancient Israelite metaphysics?

The question of this article is not which of the above alternatives was assumed in the text. Rather, if the character of YHWH was believed to be infallible (according to the theology of Gn 15), then the philosophical puzzle to be dealt with concerns the way in which Abraham and the other agents' actions were believed to be free. Prima facie we are dealing with some form of compatibilism that affirms both divine determinism and human free will. But how does the nature of divine foreknowledge in this text look when viewed from perspectives in philosophy of religion? Though at times anachronistic and wayward in terms of their philosophical-theological assumptions, several views on divine foreknowledge are available from which we could try to make sense of what for the biblical authors went without saying.

Possible philosophical perspectives

The following section is based on the outline provided by Davison (2010:n.p.). The contents of that discussion have been adopted and adapted so as to test their applicability with reference to the particular demands of the folk-philosophical assumptions behind the Old Testament text of Genesis 15 itself. In each case I shall state the basic gist of the particular theory, show what it would imply when utilised to understand Genesis 15 and lastly discern the pros and cons of such application from a more literary-historical exegetical perspective.

Denying contingency

The first possible way of clarifying the folk-philosophical assumptions of Genesis 15:12-16, is simply to play with the idea that there was not assumed to be any future contingent events. Different philosophers of religion today have taken this approach with reference to the discussion on prophecy in the Christian context for different reasons, one of which is the idea that everything that occur does so via sufficient conditions. Also:

Others believe that the idea of free choice does not require anything like real contingency or the possibility of doing or intending otherwise. Still others believe that God's providential control over the world is so thorough and detailed that nothing is left to chance, not even the apparently free choices of human beings ... (Davison 2010:n.p.)

One stereotypical theory denying all contingency is fatalism. As Zagzebski (2011:n.p.) notes, theological fatalism is the thesis that infallible divine foreknowledge of a human act makes the act necessary and hence unfree. On this view, if YHWH knows the entire future infallibly then no human act is free. The rationale behind this is the idea that, for any future act an agent could perform, if YHWH infallibly believed that the act would occur, there is nothing the agent can do about the fact that YHWH believed in its occurrence since nobody has any control over past events; nor can another character make YHWH mistaken in his belief, given that he was assumed to be infallible. But if so, the agent cannot do otherwise than what YHWH believed it would do. And if the agent cannot do otherwise, he or she will not perform the act freely (see Zagzebski 2011:n.p.)

If we assume that the text of Genesis 15:12-16 presupposes fatalism, one possible perspective would be to give up half of the problem by denying that in this text there was assumed to be any future contingent events. This in turn would suggest that when YHWH prophecies that Abraham's descendants will be oppressed and freed from Egypt, and exterminate the Canaanites, there was no philosophical puzzle since the Israelites' actions were not assumed to be free. Whilst this is certainly one way in which the text could be read, many philosophers and biblical theologians will not find this idea to be acceptable because they strongly believe in future contingent events, especially human free choices to, inter alia, account for the problem of evil. Personally I do not wish to endorse or reject this (or any other view) but offer it simply as one possible interpretation of the folk-metaphysics behind the prediction in Genesis 15:12-16.

Denying YHWH's foreknowledge

A second possible reading involves our interpretation of the text as though the narrator did not assume that YHWH had any knowledge of the contingent future in the above sense of precognition. If this is what we are up against, the metaphysical assumptions behind the prediction approximate the so-called 'Open Future' view (see Hasker 1989, 2004; Basinger & Basinger 1986; Pinnock 1986, Pinnock et al. 1994; & Rice 1985). On this reading, the narrator of Genesis 15:12-16 assumed that there may be future contingent events, but YHWH was not assumed to actually know about them. But if this was the case, how could the narrator have the character YHWH make the kind of predictions found in Genesis 15:12-16 at all?

The matter is complex. On the 'Open Future' view YHWH did not actually foretell the future. Instead, he merely revealed his personal agenda, or 'plan' (Hasker 1989:194). YHWH knew what would happen, not because he knew the future as though it was already present to his mind but because he knew his own will with reference to his own actions in the times ahead. Similar notions seem to be present in some other Old Testament prophecies, especially those that have a conditional character: 'If a nation does not do such and such, then it will be destroyed' (e.g. see Jr 18:7-10). Such prophetic predictions were assumed to be based upon existing trends and tendencies, which were believed to provide YHWH with enough evidence to know his own actions relative to the expected future (Hasker 1989:195). Thus YHWH's revelation in Genesis 15:12-16 might have been understood by the narrator to reveal not the already extant future but what YHWH had decided he wanted to bring about in the future (Hasker 1989:195). Since his own actions in the future are up to him, it is possible for YHWH to know about them even though they are contingent, and hence it is possible for the prophecy to reveal them (see Davison 2010:n.p.)

Flint (1998) has argued that responses such as the above are inadequate. He implies that if people within the world in the text were assumed to contingently free, YHWH was still assumed to know very much about his own future actions in the given present realities. The problem with this view is that if YHWH's predictions are based on what he knows he will do, there is no risk for YHWH involved. Open future views will find this problematic since they believe that YHWH does take risks and that this is the biblical perspective (see Fretheim 1982; Brueggemann 1997).

The upside of opting for this philosophical perspective is that it does not require us to read into the text of Genesis 15:12-16 the kind of perfect-being theology that is likely to be alien to the pre-philosophical theological assumptions of the narrative. Also, the distinction between YHWH knowing the future because it is fixed or because he is timeless, and knowing it because he knows what he wants to do even though he is within time (applicable here), avoids anachronistic understandings concerning the relation between YHWH and time. However, the major problem with this view in the context of Genesis 15 is that the character YHWH does not seem to be only declaring his will. Rather, the narrator seems to assume that YHWH was revealing a future state of affairs as though it was an irrevocable fate. Hence, though interesting and related to the folk-metaphysics behind some other Old Testament prophecies, the 'Open Future' perspective probably fails with reference to Genesis 15 in that it is unable to deal with the more deterministic elements in the pericope. After all, Old Testament folk-metaphysics is often not at all concerned with honouring human free will and has no problem with YHWH hardening human hearts to achieve divine ends (see the motif of the hardening of hearts e.g. in Ex 7-12).

Ockhamism and the past

William Ockham (c. 1285-1347) suggested what might be adopted by some biblical scholars as another interesting way of accounting for YHWH's knowledge of the contingent future in Genesis 15:12-16. Ockham wanted to account for divine knowledge of the contingent future by claiming:

that what a prophet has truly revealed about the contingent future 'could have been and can be false', even though the existence of the prophecy in the past is ever 'afterwards necessary'. After God has revealed a future contingency, it is necessary that the things he used to reveal it have existed, but what is revealed is not necessary. (Davison 2010:n.p., cf. Normore 1982:372)

In terms of our example involving YHWH's prophecy concerning Israel's oppression, Ockham's idea would be that were Abraham to choose freely not to have children, then YHWH would never have prophesied that his descendants would be oppressed in Egypt:

Some philosophers like to call this kind of proposition a 'backtracking counterfactual' because it is a subjunctive conditional statement whose consequent refers to an earlier time than its antecedent. (Davison 2010:n.p.)

If Abraham were about to choose freely, then YHWH would have known about it, and hence would have spoken accordingly.

The reason why philosophers of religion have expressed doubts about whether or not Ockham's approach is ultimately successful is because Ockhamism commits one to having to choose between the Scylla of claiming that YHWH 'can undo the causal history of the world and the Charybdis of claiming that divine prophecies might be deceptive or mistaken' (Freddoso 1988:61). Our concern, fortunately, does not lie with what is philosophically credible; only with what the text of Genesis 15 might have assumed or not. The Ockhamist perspective, if present in Genesis 15, would suggest that for the text Abraham was implied to have a rather odd power over the past (Wierenga 1991). Once YHWH had said certain words with a certain intention it does not seem coherent to say that Abraham was assumed to still have any choice about whether or not to procreate. Philosophically problematic as this may seem, if this view is present in Genesis 15:12-16 it would be in need of further clarification. I leave it open for discussion, however, for it seems to me unclear whether Genesis 15:12-16 presupposed Ockhamism at all.

Atemporal eternity

A fourth possible approach to explaining what was assumed about YHWH's knowledge of the contingent future in Genesis 15:12-16 suggests that the text can be read as though the narrator assumed that YHWH existed outside of time altogether. Though seemingly odd, given how YHWH interacts with Abraham in time, if this folk-metaphysical idea was present it would mean that, strictly speaking, YHWH did not foreknow what can be called the future. Instead, the assumption of Genesis 15:12-16 would be that YHWH was assumed to know all events from the perspective of timeless eternity (cf. Stump & Kretzmann 1987; Helm 1988; Leftow 1991).

Indeed, the prophecy of Genesis 15:12-16 is very specific and determinist so that it may be thought that YHWH spoke from a viewpoint he held outside of time altogether (even though it was revealed in time). If this were the case, however, YHWH's rendering the human actions inevitable is not the same as making them unfree. Philosophers sometimes distinguish:

freedom of action from freedom of will, and argue that it is possible for an action to be inevitable and yet a free action [...] when the agent himself has a powerful desire to do the action, his will is not causally determined by anything external to him or by pathological factors within him, and the inaccessible alternatives to his inevitable action are alternatives the agent has no desire to do or even some desire not to do. (see Davison 2010:n.p)

The pro of this view is that it offers an interesting ad hoc proposal with regard to the metaphysical assumptions of Genesis 15:12-16. In terms of this text, the defender of YHWH's atemporal eternity would say that YHWH was assumed by the author of Genesis 15:12-16 to have known from the perspective of eternity that the Israelites will be oppressed and freed at a certain time, and on this basis, YHWH prophesied in time that the event in question will occur. The con of this reading, whatever its philosophical efficiency, is the fact that the narrative of Genesis 15 shows us only YHWH acting in time so that whether his heavenly vantage point was assumed to be outside of time will always be an unverifiable speculation. Positing divine atemporality to account for YHWH's foreknowledge is therefore exegetically suspect because it presupposes a philosophical theology derived largely from Platonic philosophical influences (see e.g. Wolterstorff 1982). Even an appeal to analogical religious language and supposed 'divine accommodation' (as in Calvinist apologetics) seems to be anachronistic and apologetic rather than historical and descriptively philosophical in agenda.

Middle knowledge

The fifth and last perspective that might be used to explain how YHWH was assumed to know the contingent future starts with an observation concerning foreknowledge and providence known from the ideas of the 'Open Future' advocates discussed earlier (Davison 2010:n.p.). The question is this: why was knowledge of the future assumed to be useful to YHWH? Well, presumably knowledge of the future was assumed to enable YHWH to:

... make decisions about how to exercise divine power in order to accomplish the purposes behind creation. But there is a problem here: knowledge of the future is just knowledge of what will happen. By the time God knows something will happen, it is too late either to bring about its happening or to prevent it from happening. So what God needs, for the purposes of providence, is not just knowledge about what will happen. (Davison 2010:n.p.)

There is also the requirement of knowledge about what could happen and what would happen in certain circumstances.

This brings us to the theory of Luis de Molina (1535-1600) who saw clearly the relationship between divine providence and the knowledge of what could happen and would happen in various circumstances. Molina drew a useful distinction between three kinds of knowledge which YHWH would have possessed, a distinction that has seemed to many philosophers of religion to offer a promising response to the stereotypical philosophical problem of prophecies about the contingent future (see Davison 2010:n.p.)

According to Molina, the first kind of knowledge that YHWH was assumed to possess is called natural knowledge. A true proposition was assumed to be part of YHWH's natural knowledge if and only if it was believed to be a necessary truth which was thought to be beyond YHWH's control. A relevant biblical instance of such a true proposition would include the text's assumption that 'Abraham is not YHWH.' Such a truth was presupposed to be necessary and beyond even YHWH's control (i.e. nobody, including YHWH, could make them false) (Davison 2010:n.p.)

The second kind of knowledge that YHWH was assumed to possess Molina called free knowledge in as much as it was subject to YHWH's free decision. According to Molina, a true proposition would have been assumed to be part of YHWH's free knowledge if and only if it was assumed to be a contingent truth which was believed to be within YHWH's control. A biblical instance of such a true proposition would be the text's supposition that 'Abraham was called by YHWH to leave his homeland.' It was certainly assumed that YHWH had the sovereign power and freedom to have brought things about so that this true proposition could have been false instead (Davison 2010:n.p.).

A third kind of knowledge that YHWH possessed, Molina calls middle knowledge (because it is 'in between' YHWH's natural knowledge and free knowledge). A true proposition was assumed to be part of YHWH's middle knowledge if and only if it was believed to be a contingent truth (like items of YHWH's free knowledge) that was also supposed to be beyond YHWH's power. In this regard:

The most frequently discussed items of middle knowledge are often called 'counterfactuals of freedom' by philosophers, since they describe what people would freely do if placed in various possible situations. (Davison 2010:n.p.)

According to Davison (2010:n.p.), Molina implied that YHWH's providential control over the world was assumed to involve middle knowledge in a crucial way. Very briefly, here is how it is supposed to work: through natural knowledge, YHWH was assumed to know what was necessary and what was possible. Through middle knowledge, YHWH was assumed to know what every possible person would do freely in every possible situation. So YHWH decided which kind of world to create, including those situations in which free human persons should be placed, knowing how they would respond, and this results in YHWH's free knowledge (contingent truths which were assumed to be up to YHWH, which included foreknowledge of the actual future, including all human actions). Molina's theory of middle knowledge thus combines a strong, traditional notion of YHWH's control with a robust account of the contingency involved in human freedom (Davison 2010:n.p)

Like the 'Open Future' perspective, the middle knowledge view also appears to have some biblical support. There are verses which seem to attribute middle knowledge to YHWH, for example, 1 Samuel 23:6-13. If the text of Genesis 15:12-16 assumed Molina's account of YHWH's knowledge (Molinism) the narrative presupposed that YHWH knew (through middle knowledge) that if Abraham was placed in certain circumstances, then he would have descendants which would do as predicted. And for reasons not known to us, YHWH decided to create those circumstances, placed Abraham and Israel in them, and also to prophesy what Israel would do (see Flint 1998).

Whether, however, this view really helps us to understand the pre-philosophical folk-metaphysical assumptions of Genesis 15:12-16 on its own terms must remain open to question. It does not seem to be the case that YHWH was assumed to know what Abraham would freely do in all circumstances (hence the need to test his faith, see Gn 22). The middle-knowledge view arose out of the need to account for a philosophical problem that the author of Genesis 15:1216 did not presuppose in his compatibilist metaphysical assumptions. So whilst this theory is interesting as a possible lens through which to make sense of some of the philosophical puzzles of Genesis 15:12-16, the metaphysics underlying it cannot be inferred from the textual evidence itself.

Conclusion

None of the above philosophical perspectives first arose from a close reading of the Old Testament texts in general and Genesis 15:12-16 in particular. As such they represent potential philosophical clarifications of some elements in the folk-metaphysics of the text, at best. At worst, they themselves are based on philosophical-theological assumption about the nature of YHWH and the metaphysics behind the text that are mostly anachronistic. In my view it is safe to say that some sort of compatibilism is presupposed in Genesis 15:1216 since both free will and determinism seem to be affirmed without reserve. Whether this is due to divine foreknowledge or to divine power and plans for the contingent future is hard to say.

That the author of Genesis 15 was not interested in asking the kinds of questions and putting forward the sort of theories presented here is therefore not so much an argument against the philosophical elucidation of Old Testament prophecy. On the contrary, the non-philosophical nature of the textual discourse actually makes philosophical clarification all the more urgent. If we do not, we shall not understand what the biblical texts themselves took for granted. So unless Old Testament scholars comparatively test theories in philosophy of religion regarding prophecy with reference to the world in the text, there is an even greater danger of interpreting the text with anachronistic philosophical assumptions. As such we have not yet really made a beginning in coming to terms with the folk-metaphysics implicit in Old Testament prophecies.

Acknowledgements

Competing interests

The author declares that he has no financial or personal relationship(s) which may have inappropriately influenced him in writing this article.

References

Barr, J., 1999, The concept of biblical theology: An Old Testament perspective, Fortress Press, Philadelphia, PA. [ Links ]

Basinger, D. & Basinger, R., 1986, Predestination and free will: Four views of divine sovereignty and human freedom, InterVarsity Press, Downers Grove, IL. [ Links ]

Brueggeman, W., 1997, Old Testament theology: Testimony, dispute, advocacy, Fortress Press, Minneapolis, MN. [ Links ]

Clines, D., 1995, Interested parties: The ideology of readers and writers of the Hebrew Bible, JSOT Press, Sheffield. [ Links ]

Davison, S.A., 2010, 'Prophecy', The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2010 Edition), in E. Zalta (ed.), no pages, viewed 04 August 2011, from http:// plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2010/entries/prophecy/ [ Links ]

Flint, T.P., 1998, Divine providence: The Molinist account, Cornell University Press, Ithaca. [ Links ]

Freddoso, A.J., 1988, 'Introduction' to Luis de Molina, On Divine Foreknowledge (Liberi arbitri cum gratiae donis, divina praescientia, providentia, praedestinatione et reprobatione concordia, Disputations, pp. 47-53, Cornell University Press, Ithaca. [ Links ]

Fretheim, T.E., 1982, The suffering of God, Fortress Press, Philadelphia. (Overtures to Biblical Theology 12). [ Links ]

Geach, P.T., 2001, 'Prophecy,' in Truth and hope, pp. 79-90, Notre Dame Press, South Bend. [ Links ]

Hasker, W., 1989, God, time, and knowledge, Cornell University Press, Ithaca. [ Links ]

Hasker, W., 2004, Providence, evil, and the openness of God, Routledge, London. [ Links ]

Helm, P., 1988, Eternal God: A study of God without time, Oxford University Press, New York, NY. [ Links ]

Leftow, B., 1991, Time and eternity, Cornell University Press, Ithaca. [ Links ]

Nietzsche, F., 2002, Beyond good and evil, transl. J. Norman & ed. R-P. Horstmann, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. [ Links ]

Normore, C., 1982, 'Future contingents,' in N. Kretzmann, A. Kenny & J. Pinborg (eds.), The Cambridge history of later medieval philosophy, pp. 358-381, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. [ Links ]

Pinnock, C., 1986, 'God limits his knowledge,' in D. Basinger & R. Basinger (eds.), Predestination and free will: Four views of divine sovereignty and human freedom, pp. 143-162, InterVarsity Press, Downers Grove, IL. PMCid:1910345 [ Links ]

Pinnock, C., Rice, R., Sanders, J., Hasker, W. & Basinder, D., 1994, The openness of God: A biblical challenge to the traditional understanding of God, InterVarsity Press, Downers Grove, IL. [ Links ]

Rice, R., 1985, God's foreknowledge & man's free will, Bethany House Publishers, Minneapolis, MN. [ Links ]

Stump, E. & Kretzmann, N., 1987, 'Eternity,' in T.V. Morris (ed.), The concept of God, pp. 219-252, Oxford University Press, New York, NY. [ Links ]

Wierenga, E., 1991, 'Prophecy, freedom, and the necessity of the past,' in J. Tomberlin (ed.), Philosophical perspectives 5: Philosophy of religion, pp. 425-445, Ridgeview Press, Atascadeo, CA. [ Links ]

Wolterstorff, N., 1982, 'God everlasting,' in S.M. Cahn & D. Shatz (ed.), Contemporary philosophy of religion, pp. 77-98, Oxford University Press, New York, NY. [ Links ]

Zagzebski, L., 2011, 'Foreknowledge and free will', in E.N. Zalta (ed.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2011 Edition), no pages, viewed 16 November 2011, from http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2011/entries/free-will-foreknowledge/ [ Links ]

Correspondence to:

Correspondence to:

Jaco Gericke

PO Box 1174, Vanderbijlpark 1900, South Africa

Email: 21609268@nwu.ac.za

Received: 21 Nov. 2011

Accepted: 09 July 2012

Published: 04 Mar. 2013