Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

HTS Theological Studies

On-line version ISSN 2072-8050

Print version ISSN 0259-9422

Herv. teol. stud. vol.68 n.2 Pretoria Jan. 2012

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

PRACTICAL THEOLOGY

From periphery to the centre: towards repositioning churches for a meaningful contribution to public health care

Vhumani Magezi

Department of Ecclesiastical Sciences, North-West University, Potchefstroom Campus, South Africa

ABSTRACT

The role of communities in health care has gained prominence in the last few years. Churches as community structures have been identified as instrumental in health-care delivery. Whilst it is widely acknowledged that churches provide important health services, particularly in countries where there are poorly-developed health sectors, the role of churches in health care is poorly understood and often overlooked. This article discusses some causes of this lacuna and makes suggestions for repositioning churches for a meaningful contribution to health care. Firstly, the article provides a context by reviewing literature on the church and health care. Secondly, it clarifies the nature of interventions and the competencies of churches. Thirdly, it discusses the operational meaning of church and churches for assessing health-care contributions. Fourthly, it explores the health-care models that are discerned in church and health-care literature. Fifthly, it discusses the contribution of churches within a multidisciplinary health team. Sixthly, it proposes an appropriate motivation that should drive churches to be involved in health care and the ecclesiological design that underpins such health care interventions.

Introduction and background

The role of community involvement in health care, particularly churches, has gained prominence in recent years. A significant number of community-health organisations are driven by churches, and yet the contribution of churches to public health has been downplayed (Dejong 1991; Fossett 2004). Churches seem to be increasingly marginalised in shaping health policy despite church-care ministries forming the foundations of present day care as it is practiced (Stark 1997). This situation prompts the question of how churches could be repositioned for a practical contribution towards health-care ministries in a manner that effectively integrates the spiritual and practical dimensions.

The role of communities in strengthening the delivery of health care has gained prominence in the last few years. The recently concluded 19th International Aids Conference (22-27 July 2012) in the USA (Washington DC) brought the issue of the delivery of health care into sharp focus. The theme of one of the pre-conference workshops, 'Ending vertical transmission through community action', makes clear what the issue is perceived to be. Whilst there is debate concerning the efficacy of community interventions, there is consensus that community interventions are effective. However, the challenge is to design the interventions in a rigorous way to demonstrate its effect. Thus the role of churches as community groups are widely recognised, but the challenge equally stands that social intervention by churches should be executed rigorously.

The increased interest in community interventions arise from the realisation that biomedical interventions in health will not be effective without being complemented by modification in behaviour. It is clear that a drug will not be effective if the right dosage is not taken and if there is no adherence to dosage guidelines. Certainly, the latter supportive interventions are behavioural rather than biomedical. To cite one example, the realisation that behaviour has to change has given an impetus to combination prevention discourse in HIV prevention.

The role of communities as represented by community based organisations (CBOs) and nongovernmental organisations (NGOs) in health is widely acknowledged. Dejong (1991) observes that NGOs are major contributors to health-care delivery in sub-Saharan Africa, yet until recently, there has been a notable absence of knowledge about the nature of their activities. Dejong (1991) further explains that this lacuna has critical implications given the current trend among donors to channel funds to NGOs and encourage their role in social development. Furthermore, in an era of shrinking overall resources, governments' fragmentary knowledge of the activities of NGOs in the health sector is likely to impede their optimising the use of national resources for health whether they are public, private or non-governmental within the framework of government policies. Within Africa, churches form one category of NGOs or CBOs that have been providing health care.

Since Dejong's observation in 1991, much has changed. There has been intense interest in a number of developing countries to change the structure and internal relations of the health sector. Green, Shaw, Dimmock and Conn (2002) report that health-sector reform policies promulgated initially by the World Bank in 1993 and picked up enthusiastically by a number of other donors and governments have often included the promotion of a public or private mix. Though the precise meaning of this policy element is not always clear, it generally endorses recognition of the actual and potential contribution of the non-state sector and the need to develop clear roles for and relationships between the different healthcare actors.

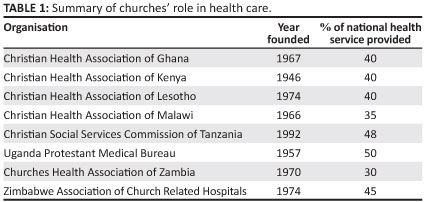

The above reforms were driven by two policy developments that can rightly be weaved into churches' role in providing health care. Firstly, although there was widespread church-based health care in many African countries prior to the 1980s, it was largely provided without dependence on the state sector. For instance, the first rural hospital and successive ones in similar rural locations in Zimbabwe were started by churches, for example Mt Selinda (1893) followed by Morgenster Mission (1894), Chikore (1900) and several others (Zvongo 1986). Secondly, the Alma Ata Declaration of 1978 (World Health Organization [WHO] 1978), which was itself partly the product of church experiences with community outreach programmes and follow-up policies, stressed a broader concept of health leading to both multi-sectoralism and a recognition of the multi-agency nature of the health care sector (WHO 1978; Richter & Foster 2006, Green et al. 2002). Green et al. (2002) clearly illustrate the leading role of churches in health care in Africa (see Table 1).

The Alma Ata Declaration defined primary health care as essential health care made accessible to families in the community through their full participation. It noted that 'people have the right and duty to participate individually and collectively in the planning and implementation of their health care' (WHO 1978). The benefits that result from linking community and health-sector responses include increased numbers of people from underserved areas accessing clinical services, better follow-up and adherence to treatment of patients with chronic illnesses, better understanding by health workers of the socio-economic determinants of health and improved quality as well as increased coverage of community-level health activities.

The article by Foster (2010) further illustrates the leading role of churches in health care. He demonstrates that, out of 671 churches surveyed in Namibia, Uganda and Sierra Leone, 53% have church-based HIV initiatives, but only 25% of these churches receive external funding (see Table 2).

The above discussion revealed that the shifts in the 1980s led to greater policy interest in NGOs and churches, in part related to their greater institutional flexibility and their ability to cross sectoral boundaries. However, it was the advent of health-sector reform policies that led to the widest opening of the window of opportunity for a reconfiguration of relations between the church and the public sector. Though not explicitly referring to churches, many governments have embraced community contributions to health care. Two examples suffice to illustrate this point. The HIV and AIDS and STI National Strategic Plan, 2007-2011, (NSP) for South Africa states that addressing HIV is far from being the responsibility of a single player (i.e. government). Rather, it is the responsibility of all sectors. Interventions should be multifaceted, collaborative and multisectoral. One of the six guiding principles for the NSP is to develop partnerships between government departments and civil society for effective responses. Central to the implementation of the NSP are civil-society organisations, which are responsible for taking the lead in implementing more than 75% of intervention objectives, whilst in other priority areas such as prevention and treatment, care and support, the civil-society organisations lead in more than 90% of cases (Magezi 2008b; Magezi 2010; South African Government Information n.d.).

Similarly, the Zimbabwean strategy for the prevention of mother to child transmission (PMTCT), drawing from the WHO (2010) four prongs (i.e. WHO PMTCT Strategic Vision 2010-2015) emphasises the role of communities. The strategy focuses on the following four areas: the primary prevention of HIV, the prevention of unintended pregnancies in women living with HIV, the prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV and the provision of care and support for women living with HIV, their children and their families. Furthermore, goal 32 of the Zimbabwe National Health Strategy (2009-2013) reflects the need to enhance community participation and involvement in improving health and quality of life. Its aim is, amongst others, to make individuals, families and communities aware of their rights and responsibilities, to re-vitalise and strengthen the role of the village health worker and other community-health workers, to provide an enabling implementation framework for community participation and to empower communities and ensure their involvement in the governance of health services (The United Nations Population Fund [UNFPA] n.d.).

The foregoing discussion demonstrated that, from a policy perspective, there is an emphasis on community involvement in health care with churches playing a leading role. Secondly, the significant majority of community organisations are driven by churches. However, despite this central role in health, the contribution of churches in public health has been downplayed (Dejong 1991; Fossett 2004). There is very little reference to churches' practical contribution apart from spiritual counselling and direction under the guise of an holistic health-care concept as espoused by the WHO (National Centre for Cultural Competence 2001). This observation has been noted widely and has been pointed out in numerous publications. A study by Laris, Baum, Schaay, Sanders and Kahssay (2001) confirmed that women, youth, religious and traditional groups, termed 'local civil society organisations' (LCSO), undertook considerable health-development activities. However, despite LCSO's contribution to health development, their activities were poorly recognised and under-supported by health sectors (Laris et al. 2001). LCSOs that are engaged in health activities frequently complain about the growing distance between them and the formal health sector. Green et al. (2002) added that, for well over a century, missionary organisations have played a significant role in the development and provision of health care in many African countries. These church health services are nevertheless overlooked by the policy makers in health care. Churches' health services seem to fit uncomfortably within broader NGO systems and structures, and yet they are probably the type of NGO most widely involved in health care and especially hospital care in Africa today.

With increased secularisation, churches are increasingly being marginalised by being allowed little contribution in shaping policy, this while churches' care ministries form the foundations of present day care as it is practiced (Stark 1997). This situation prompts the following question: How can churches be repositioned for a practical contribution to health care ministries in a manner that effectively integrates both the spiritual and practical dimensions. In an earlier article (Magezi 2008a), I argued that churches have a 'dual function', which I termed 'duality of function' regarding its role in health and well-being. The duality of function draws from churches' 'substantive message' and 'praxis'. Alongside Parry (2003), UNICEF & UNAIDS (2003) and others, I argue that the churches' comparative advantage in praxis draws from infrastructure, location, ability to influence, respect and cohesion while the paradigm of service in Christian Scriptures informs the substantive aspect.

A response to the above question suggests that churches should be shifted from the periphery to the centre of healthcare services. The metaphor of 'shifting from periphery to the centre' attempts to capture a change from token recognition and participation by churches to allowing them to make a meaningful contribution to health care. This entails making churches equal partners in roundtable discussions on health care. The notion of roundtable dispels the idea of top-down and prescriptive approaches where communities play a minimal role and are at the mercy of health-care staff. It makes health care the shared responsibility of health-care staff and communities. However, to carve out this path, several factors should be considered:

• clarity concerning the nature of interventions and the competencies of churches

• meaning of church and churches for operationalisation in health care

• health-care models that could be discerned from literature

• the contribution of churches within multidisciplinary health teams

• the motivation of churches

• practical interventions that churches can perform.

Nature of interventions and competencies of churches

To gain further insight into the role of churches in health care, Foster (2010), citing studies by the African Religious Health Assets Programme (ARHAP) (2006), Uganda Christian AIDS Network (UCAN) (2003), Weekes (2007) and Yates (2003), noted that many community-level HIV and AIDS responses in sub-Saharan Africa are implemented by faith-based organisations. For instance, some 5000 faith-based groups support children, people living with HIV and AIDS and the chronically ill through home-care initiatives in Lesotho. From an extensive mapping study in Zambia, congregations and religious support groups constitute the majority (63%) of community-level organisations involved in health-care activities while faith-based groups represent 71% of all organisations responding to HIV. Of 96 congregations and religious support groups surveyed, 88 (92%) offered one or more HIV-related service.

Dejong (1991) maintains that interaction between churches and formal health care varies. The heterogeneous nature of church interventions makes it impossible to generalise about the nature of their activities. The formal health sectors interact with communities through outreach services, community-health committees and the involvement of health workers from the clinic together with traditional birth attendants, community-health workers and other volunteers. At the same time, community-level groups, organisations and committees frequently initiate and implement their own health-related activities. These groups vary considerably in their make-up, functioning and degree of engagement with health structures. Thus, the heterogeneity of community health activities makes community-owned health initiatives difficult to characterise. However, one characteristic is undisputed - their pervasiveness. A nine-country study sponsored by the World Health Organization found over 500 community groups implementing health activities in two districts in Nigeria and Senegal (WHO 1994).

The National Association of Non-Governmental Organisations (NANGO) (2011) of Zimbabwe advised that the church is an important aspect of any society and that people find full expression and personal development in the church and church practices. The Zimbabwe Association of Church-related Hospitals (ZACH) (Christian Connections for International Health [CCIH] 1992) added that the concern for the human kind, especially for the poor, is an integral part of the gospel and the church's mission in promoting health and wholeness.

As already pointed out earlier, these observations have been noted in numerous publications. The problem, however, is that these observations remain impressionistic, superficial and lacking a detailed delineation to make meaningful policy contribution. The role of churches remains somewhat hanging in the air, lacking practical evidence to ground and legitimise it. The questions that should be posed are: Why is the contribution of churches to health care not spoken about and often misunderstood? Can churches' contribution be clearly understood and demonstrated to make meaningful policy contributions? Indeed, the role of churches can be demonstrated, but certain clarifications have to be made for meaningful dialogue and discourse at an interdisciplinary roundtable. Clarifications on the following areas should be sought:

1. the usage of the word church and churches

2. health models being employed

3. clarity of roles within a multidisciplinary discussion

4. the motivation of churches for engaging in health work.

Confusing usage of the word church and churches in health-care discourse

The word 'church' comes from the Greek noun, to kuriakon, used first of the house of the Lord, and then of his people (Clowney 1988). It is always used in the Bible to translate the Greek word ekklesia. However, it is important to underline that ekklesia does not refer to a building but to an assembly of people (Hill 1988). Ekklesia (noun) is a word derived from the verb ekkaleo meaning to summon or to call out. The closest English equivalent of the word is convocation - a calling together, an assembly. It was the official term for the Athenian democracy, and it is in this secular sense that it is used in Acts 19:32, 39, 41 (Hill 1988). However, the New Testament's use of ekklesia is controlled by its employment in the Septuagint

(LXX) to translate the Hebrew word qahal, which has the same meaning of a convened assembly (Grudem 1994). In the strongest sense, the qahal is the assembly of Israel convened by God (e.g. Dt 23:2-9; 1 Chr 28:8; Nm 16:3, 20:4). Thus in the New Testament, ekklesia is used for a public assemblage summoned by a herald, and in the Old Testament (LXX), it refers to the assembly of the Israelites especially gathered before the Lord (Best 1988; Clouse 2001; Clowney 1988; Gehman 1990; Grudem 1994; Hill 1988).

Grudem (1994) usefully summaries the usage of the word church as follows:

A 'house church' is called a 'church' in Romans 16:5 ('greet also the church in their house'), 1 Corinthians 16:19 ('Aquila and Prisca, together with the church in their house, send you hearty greetings in the Lord'). The church in an entire city is also called 'a church' (1 Cor. 1:2; 2 Cor. 1:1; and 1 Thess. 1:1). The church in a region is referred to as a 'church' in Acts 9:31: 'So the church throughout all Judea and Galilee and Samaria had peace and was built up.' Finally, the church throughout the entire world can be referred to as 'the church.' Paul says, 'Christ loved the church and gave himself up for her' (Eph. 5:25) and says, 'God has appointed in the church first apostles, second prophets, third teachers' (1 Cor. 12:28) ... We may conclude that the group of God's people considered at any level from local to universal may rightly be called 'a church.' (p. 857)

Whilst technically the meaning of church refers to the group of God's people considered at any level from local to universal, in its daily use, the word is used interchangeably in three ways, namely local assembly or congregation, denomination and universal church. These usages pose operational challenges in health-care assessment. Theologically and spiritually, one can speak of universal church, but operationally, it is impractical. Churches hold different views ranging from active participation to non-participation in health care. Similarly, different denominations hold different views regarding their involvement in practical ministry. Local congregations also differ in their theological positions and affiliations, which influence their various responses. Therefore, in referring to church or churches, it is often unclear what is meant by church. This confusion has not been seriously reflected upon.

However, with all the reference to the role of churches in health care, it is worthwhile to ask what is usually meant by church involvement in health care.

Towards a typology of church involvement in health care

Many scholars in the church-related health and development sector submit that churches are playing a critical role in health care (Fossett 2004; Foster 2010; Green et al. 2002; Zvobgo 1986). Notwithstanding the merits of this statement, the claim is arguably simplistic and impressionistic. It lacks a detailed analysis based on a proper definitional framework of what is meant by church.

In reviewing the literature on church and development, four models or typologies can be discerned. I have named the models as follows, (1) government clad in church health care, (2) church diakonia department, (3) congregational ecology and (4) refusal - not here!

To illustrate the typologies, I will use the Zimbabwean health-care system. The government clad in church healthcare model refers to clinics and hospitals that were started by missionaries at denominational level. These institutions function like government hospitals in every respect. Amongst others, the staff is employed by the Ministry of Health, and the hospitals receive a drug allocation from the Ministry of Health even though they sometimes have to supplement it. The hospitals provide the same medical-care services provided at government health-care centres. The church (denomination) leadership in turn influences government on institutional staffing, particularly the calibre of staff to be employed. Through their network with mission agencies, the churches sometimes complement the Ministry of Health by sourcing additional staff to reduce the staff-patient ratio. The reference by Green et al. (2002) to the church's healthcare interventions applies to this model (Table 1). I have termed it 'government clad in church health care' because, in essence, it is run by government with the Ministry of Health controlling the work. Examples of such hospitals are Mt Selinda Hospital, Mutambara Mission Hospital, Kwenda Mission Hospital and Morgenster Mission Hospital.

The 'church diakonia department' refers to denominations with established health and development departments. These departments sometimes implement activities complementary to the mission hospital, or they act independently. For instance, the Reformed Church in Zimbabwe established the Community Based AIDS Programme (CBAP) which is an outreach arm of the Morgenster Mission Hospital. These interventions could also be independent of the church hospitals (i.e. under 'government clad in health care') model. An example is the United Methodist Church. This church (denomination) has a development desk, but each congregation implements independent health activities with financial or some other form of support from the development desk. The 'church diakonia department' model differs from the 'government clad in health care' model in that the former is controlled by church (denomination) leadership who often appoints the workers and decide on resource allocation. Most of the health interventions implemented under this model are HIV-related and other care ministries.

The 'congregational ecology' model refers to individual congregations responding to health care needs that organically arise in their context. The interventions arise out of community need. In many cases, the congregation and the community join hands in addressing a common problem. The Umoja model of the community and the church working together, which have been implemented successfully in East Africa, is a good example (Njoroge, Raistrick & Mouradian 2010). The interventions largely focus on HIV and AIDS and other community problems. The interventions are, however, made on an ad hoc basis and they are unsystematic and without support from the outside. The interventions are driven out of compassion by sacrificial champions. The majority of these congregations are marginalised, and the leaders are not linked to external support systems (Foster 2004, 2005).

The 'refusal - not here!' model largely refers to African Independent Churches (AICs) that refuse to take up health services both at denomination or local assembly levels (see Table 3 below for a summary of the models).

From the typologies discussed above, it is clear that 'government clad church health care' is the most commonly found intervention of churches in health care. In Zimbabwe, 115 (7.5%) of the 1533 hospitals and clinics are church hospitals and clinics (i.e. government clad church health care) (Ministry of Health and Child Welfare [MoHCW] 2010). These health-care sites are mostly located in rural areas. This model of health care is similar to government health-care sites. The role of the 'church diakonia department' and 'congregational ecology' models is largely in HIV and other development-related activities. Despite the possible flexibility of the 'church diakonia department' model due to an independent leadership, the interventions are weakened by the weak focus on pure health, the lack recognition by the Ministry of Health and Child Welfare and top-level influence that sometimes limit congregations' organic responses. The 'congregational ecology' model is weakened by the following factors, amongst others: lack of credibility and expertise to meaningfully participate in health care, unknown role of and effect by the outside stakeholders and looked down upon by health institutions.

The paradox in the above models is that most of the community and church work occurs at 'congregational ecology' level. The notion of congregational ecology is emphasised by Moltmann (1993). He rightly maintains the notion of the church as base communities, which he calls 'grass-roots' communities. He argues that these grassroots communities are a prophetic leaven for the renewal of church and society. The people live in a simple communion of the saints or fellowship of believers in a convincing way through open friendships. Accordingly, it can be argued that, to realise the results of health improvement through community participation, the interventions should be implemented at congregational ecology level (Magezi 2007). By implication, therefore, to truly have church health-care interventions, it is imperative to support the 'congregational ecology' model rather than other models. It is arguably at this level that churches can effectively link and form multidisciplinary teams to deliver health services. Considering the weakness of this model, however, the question that should be posed is the following: How should the 'congregational ecology' model be strengthened? To answer this question, one should begin by cataloguing health services that can be implemented at congregational level - to which we now turn.

Towards the church's (congregational ecology) contribution in health

Role clarity within a multidisciplinary team

The starting point in making a congregational contribution to health care is to outline the services provided in a community based health system. The National Center for Cultural Competence (2001) developed a practical Integrated Primary Care Community-Based Health System (IPCCBHS) model that can be borrowed to illustrate what churches can do. The model identified three categories. Category one interventions include outreach and health education, category two includes interventions like preventive and primary care, and category three includes case-management and an integrated referral system. The model is illustrated in Figure 1.

Apart from the interventions that are highlighted by the IPCCBHS model above, the church can effectively be involved in health information dissemination such as immunisation, disease surveillance, leading in the establishment of facilities and community-based support groups, coordinating community structures, participating in multidisciplinary health-delivery teams, as well as participating in outreach services and community-health committees. The churches can also be involved in training traditional birth attendants, community-health workers and other volunteers. Churches can furthermore advocate for greater access to health care and provide resources such as nutritious food and income-generating assistance to the needy, especially those in rural areas.

Thus the three areas in which churches can meaningfully participate are the following: increasing access to primary and preventive care, improving delivery and quality of health care and improving patients' self-management of their disease. Churches have a comparative advantage over government health-care systems in performing these tasks.

To effectively perform these functions, individual church members should have proper motivation.

Towards an appropriate church motivation and ministry for churches' health care

Historically, church-based medical care developed as part of the Christian mission 'to proclaim the Kingdom of God and to heal' (Lk 9:2). The traditional mission station included a church, a school and a hospital (Green et al. 2002). Green et al. (2002), citing Schulpen, observed that there were other motivations for establishing church-based medical care. These included compassion for the people in need out of pure Christian charity, contact with people especially where verbal communication was difficult, looking after the health of their own missionaries, being a prestige object for the church, helping to build the 'Kingdom of God' and to establish 'visible signs of God's presence' and being a source of income to finance other missionary activities.

However, the motivation of churches' involvement in health delivery has been a matter of considerable debate. Three views are maintained. Firstly, the motivation is the provision of medical services as merely a practical expression of Christian faith. Secondly, medical care is used as a method of evangelism to bring individuals and communities to believe in Christ. This way of health care is viewed as a means of promoting the Christian faith (Fossett 2004). Thirdly, medical care is seen as a social duty to meet medical or social needs, that is viewing health as a human right.

Considering these views, the church's motivation should be resolved to ensure service provision that is impartial and without strings attached. The appropriate motivation is suggested by Grudem (1994). He says that ministries of mercy, such as health care to communities, should be underpinned by Christians' nature of sacrificial care and love (agape). He adds that ministries of mercy should include participation in civic activities or attempting to influence governmental policies to make them more consistent with biblical moral principles. Churches should also be involved in areas where there is systematic injustice manifested in the treatment of the poor and/or ethnic or religious minorities. The church should also pray and - where the opportunity arises - speak against injustice. All of these, Grudem says, are ways in which the church can supplement its evangelistic ministry to the world. Grudem rightly argues that churches should be motivated by the desire for mercy and not by any other selfish reasons.

Considering that churches have many other competing ministries, the following question could be posed: Is the expectation that churches should participate in health care an imposition to have churches participate or be involved in every challenge that arises in a community? This is a legitimate question indeed. However, doing ministry in real life is fluid. Human beings are integrated. The Christian worker (e.g. pastor, lay leader, youth leader and other kinds of workers) is challenged to constantly assume various roles to embody a holistic gospel ministry. Hence, to fulfil this role, church responses to health should organically arise rather than be imposed. In this way, churches will contribute to people's health in their communities. Health refers to 'a complete state of physical, mental, spiritual and social wellbeing and not merely an absence of disease' (WHO 1948). This definition has not been amended since its inception in 1946.

Smit (2003) argues that the church should not be 'docetic'. The church should see and respond to suffering people in personal and creative ways. Smit's concern and argument, as shared by Louw (1998), is that Christianity should not be a sterile objectivism, a transcendent dimension that excludes the realities of being human. It should interpret and understand the Christian truth in terms of human experience in the world. Thus the challenge for the Church is to interpret God and salvation in terms of contextual life issues. Churches should, therefore, be designed in a manner that is sensitive to their context and intervene in concrete ways. Churches are subsystems of communities; hence they cannot be aloof when they can do something about the situation. And this something could be health-care delivery.

Conclusion

This article has argued that the role of communities in health care has gained prominence in the last few years. Churches as community structures have been identified as instrumental in health-care delivery. Whilst it is widely acknowledged that churches provide important health services, particularly in countries where there are poorly-developed health sectors, the role of churches in health care is poorly understood and often overlooked. This problem partly arises from a lack of clarity on the meaning and usage of the word church and churches in health care, church health models, unrealistic expectations and a lack of clarity on the contributions expected of churches within multidisciplinary health teams and conflicting motivations for becoming involved. This article has reviewed literature on and responded to the lack of recognition of churches in health care. It has clarified the nature of interventions and competencies of churches, discussed the operational meaning of church and churches for assessing health-care contributions, explored the healthcare models that are discerned in church and health-care literature, discussed the contribution of churches within a multidisciplinary health team and proposed an appropriate motivation that should drive churches to be involved in health care and the ecclesiological design that should underpin such health-care interventions.

Acknowledgements

Competing interests

The author declares that he has no financial or personal relationship(s) which may have inappropriately influenced him in writing this article.

References

African Religious Health Assets Programme (ARHAP), 2006, Appreciating Assets: The Contribution of Religion to Universal Access in Africa, Report for the World Health Organization, viewed n.d., from http://www.arhap.uct.ac.za/publications.php#reports [ Links ]

Best, E., 1988, 'Church', in P.J. Achtemeier et al. (eds.) Harper's Bible Dictionary, pp. 383-384, Harper and Row, San Francisco. [ Links ]

Christian Connections for International Health (CCIH) 1992, Zimbabwe Association of Church-Related Hospitals (ZACH): An evaluation report on the work of ZACH: Achievements and problems encountered, August 1992, viewed 25 July 2012, from http://www.ccih.org/ZACH-profile-Oct2010.pdf [ Links ]

Clouse, R.G., 2001, 'Church' in W.A. Elwell (ed.), Evangelical dictionary of theory, 2nd edn., pp. 395-396, Baker Academic, Grand Rapids. [ Links ]

Clowney, E.P., 1988, 'Church', in J.I. Packer (ed.), New Dictionary of Theology, pp. 141-146, Intervarsity Press, Leicester. [ Links ]

Dejong, J., 1991, 'The role of non-governmental organizations in health delivery in Sub-Saharan Africa', Working Paper no. 708, June 1991, Department of Population and Human Resources, The World Bank. [ Links ]

Fossett, J.W., 2004, 'Medicaid and faith organizations participation and potential: The roundtable on religion and social welfare policy', an independent research project of the Rockefeller Institute of Government Supported by The Pew Charitable Trusts. [ Links ]

Foster, G., 2004, 'Study of the response by faith-based organisations to orphans and vulnerable children, New York and Nairobi, World Conference of Religions for Peace and UNICEF', in Eldis, viewed 30 July 2012, from http://www.eldis.org/ go/topics/dossiers/meeting-the-health-related-needs-of-the-very-poor/other-strategies-for-reaching-the-poor/role-of-civil-society&id=14774&type=Document [ Links ]

Foster, G., 2005, 'Under the radar: Community safety nets for children affected by HIV/AIDS in extremely poor households in Sub-Saharan Africa', United Nations Research Institute for Social Development, in Southern African Regional Poverty Network, viewed 26 July 2012, from www.sarpn.org.za/documents/d0001830/ Unrisd_children-hiv_Jan2005.pdf [ Links ]

Foster, G., 2010, 'Faith untapped: Linking community-level and sectoral health and HIV/AIDS responses', in The United States President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief, viewed 28 July 2012, from http://www.pepfar.gov/documents/ organization/195614.pdf [ Links ]

Gehman, H.S., 1990, 'Church', in H.S. Gehman (ed.), The New Westminster dictionary of the Bible, pp. 175-176, The Westminster Press, Philadelphia. [ Links ]

Green, A., Shaw, J., Dimmock, F. & Conn, C., 2002, A shared mission? Changing relationships between government and church health services in Africa, International Journal of Health Planning and Management 17, 333-353. [ Links ]

Grudem, W., 1994, Systematic theology: An introduction to Biblical doctrine, Intervarsity Press, Leicester. [ Links ]

Hill, E., 1988, 'Church', in J.A. Komonchak, M. Collins & D.A. Lane (eds.), The New Dictionary of Theology, pp. 196-198, Liturgical Press, Collegeville. [ Links ]

Laris, P., Baum, F., Schaay, N., Sanders, D. & Kahssay, H., 2001, 'Tapping in to civil society: Guidelines for linking health systems with civil society', The National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry: BN0 73089 2883, viewed 30 July 2012, from http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2001/0730892883_eng.pdf [ Links ]

Louw, D.J., 1998, A pastoral hermeneutics of care and encounter, Lux Verbi, Cape Town. [ Links ]

Magezi, V., 2007, HIV and AIDS, poverty and pastoral care and counselling: A home-based and congregational systems ministerial approach in Africa, Sun Media, Stellenbosch. [ Links ]

Magezi, V., 2008a, 'Possibilities and opportunities: Exploring the Church's contribution to fostering national health and well-being in South Africa', Practical Theology in South Africa 23(3), 261-278. [ Links ]

Magezi, V., 2008b, 'Implementing the NSP-NGOs' role: Government, NGOs and CBOs collaboration in HIV and AIDS: AFSA's experience', in AIDS Foundation South Africa, viewed 30 July 2012, from http://www.aids.org.za/research_internal.htm [ Links ]

Magezi, V., 2010, 'Overcoming structural church barriers: Towards a systems assessment model for effective HIV and AIDS ministry', Journal of Theology for Southern Africa, 137(July), 28-45. [ Links ]

Ministry of Health and Child Welfare (MoHCW), 2010, Provincial and district health centres in Zimbabwe, viewed 30 June 2012, from http://www.mohcw.gov.zw/ index.php/provincial-hospitals [ Links ]

Moltmann, J., 1993, The Church in the power of the Spirit: A contribution to Messianic ecclesiology, Fortress Press, Minneapolis. [ Links ]

Njoroge, F., Raistrick, T. Crooks, B. & Mouradian, J. 2010, 'UMOJA, Transforming communities: Information guide: Online: HIV/AIDS', in Tearfund, viewed 30 July 2012 from http://tilz.tearfund.org/webdocs/Tilz/Churches/Umoja/Umoja%20 Coordinators%20Guide%20-%20Jan2012.pdf [ Links ]

National Association of Non-Governmental Organisations (NANGO), 2011, National healing consultative forum, Kariba, 13-14 May 2009, viewed on 31 July 2012, from http://Bishopkadenge.Blogspot.Com/2009/05/National-Healing-Consultative-Forum.html. [ Links ]

National Center for Cultural Competence, 2001, Sharing a legacy of caring partnerships between health care and faith-based organizations, viewed n.d., from http://www11.georgetown.edu/research/gucchd/nccc/documents/faith.pdf [ Links ]

Parry, S., 2003, 'Responses of the faith-based organisations to HIV/AIDS in Sub Saharan Africa', in World Council of Churches, viewed 25 July 2012, from http://www.wcc-coe.org/wcc/what/mission/fba-hiv-aids.pdf [ Links ]

Richter, L. & Foster, G., 2006, The role of the health sector in strengthening systems to support children's healthy development in communities affected by HIV/AIDS: A review, WHO, Geneva. [ Links ]

Smit, D.J., 2003, 'On learning to see? A reformed perspective on the church and the poor', in P.D. Couture & B. Miller-McLemore (eds.), Poverty, suffering and HIV-AIDS: International practical theological perspectives, pp. 271-284, Cardiff Academic Press, Fairwater. [ Links ]

South African Government Information, n.d., HIV & AIDS and STI strategic plan for South Africa 2007-2011, viewed 28 July 2012, from http://www.info.gov.za/otherdocs/2007/aidsplan2007/index.html [ Links ]

Stark, R., 1997, The rise of Christianity: How the obscure, marginal, Jesus movement became the dominant religious force, Princeton University Press, Washington. [ Links ]

The United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), n.d., The National Health Strategy for Zimbabwe (2009-2013), viewed 20 July 2012, from http://www.unfpa.org/ sowmy/resources/docs/libra ry/R174_MOHZimba bwe_NatHealthStrategy2009-2013-FINAL.pdf [ Links ]

Uganda Christian AIDS Network (UCAN), 2003, Situation analysis of church response to HIV/AIDS in Uganda, viewed n.d., from http://pacanet.net/newsite/wp-content/ uploads/2012/10/Uganda_Report.pdf [ Links ]

UNICEF & UNAIDS, 2003, What Religious Leaders Can Do About HIV/AIDS. Action for children and young people, viewed 30 July 2012, from http://www.ngogateway.org/ngo/handle/1/700 [ Links ]

Weekes, S.B., 2007, Situation Analysis Report of the church response to HIV and AIDS in Sierra Leone, viewed n.d., from http://pacanet.net/newsite/countries-where-we-work/sierra-leone-2/ [ Links ]

World Health Organization (WHO), 1948, WHO definition of health, viewed 06 July 2012, from http://www.who.int/about/definition/en/print.html. [ Links ]

World Health Organization (WHO), 1978, Declaration of Alma-Ata, WHO, Geneva. [ Links ]

World Health Organization (WHO), 1994, Health development structures in district health systems: The hidden resources, WHO Division of Strengthening of Health Services, Geneva. [ Links ]

World Health Organisation (WHO), 2010, PMTCTstrategic vision 2010-2015: Preventing mother-to-child transmission of HIV to reach the UNGASS and Millenium Development Goals: Moving towards the elimination of paediatric HIV, viewed 05 December 2011, from http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/mtct/strategic_vision.pdf [ Links ]

Yates, D., 2003, 'Situational analysis of the church response to HIV/AIDS in Namibia: Final report', in Pan African Christian AIDS Network, viewed n.d., from http://pacanet.net/newsite/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/Namibia_Report1.pdf. [ Links ]

Zvobgo, C.J., 1986, 'Medical missions: A neglected theme in Zimbabwe History, 1893-1897', Zambezia Xiii(ii), 109-118. [ Links ]

Correspondence to:

Correspondence to:

Vhumani Magezi

63 Aalwyn Street, Stand 2050,

Extension 3, Riverlea 2093,

South Africa

vhumani@hotmail.com

Received: 01 Aug. 2012

Accepted: 22 Oct. 2012

Published: 03 Dec. 2012

© 2012. The Authors. Licensee: AOSIS OpenJournals. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution License.

Note: This article is published in the section Practical Theology of the Society for Practical Theology in South Africa.