Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

HTS Theological Studies

On-line version ISSN 2072-8050

Print version ISSN 0259-9422

Herv. teol. stud. vol.68 n.2 Pretoria Jan. 2012

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

PRACTICAL THEOLOGY

Listening to Africa's children in the process of practical theological interpretation: a South African application

Ignatius SwartI; Hannelie YatesII

IResearch Institute for Theology and Religion, University of South Africa, South Africa

IICentre for Child, Youth and Family Studies, North-West University, South Africa

ABSTRACT

As part of the theological task of developing a publicly oriented ministry that will do justice to the social plight of children in Africa, this article adopted as its point of departure an appreciation of the new 'hermeneutics of listening' that is advanced today by an interdisciplinary movement of scholars from the disciplines of practical theology, theological ethics and religion studies. Emphasising the fact that this new hermeneutics is by and large the result of this scholarly movement's newly-found engagement with, and exposure to, the social science field of childhood studies, the article moved from a more general appreciation of the new hermeneutical line of thinking to a more pertinent evaluation of the unfolding of this line of thinking in the scholarly context of Africa. In a further development that narrows the African focus to South Africa, the results from a recent empirical investigation amongst members of the South African practical theological academy were discussed in particular to determine the extent of this group's shift to the new line of thinking. This led the article to make a concluding statement, in the light of its overt practical theological interest, about the way in which the new 'hermeneutics of listening' to children could still be seen as an important ongoing challenge, not only for practical theological scholarship in South Africa but also within the larger context of Africa.

The voices, views and visions of young people themselves still wait to be heard and considered. We know remarkably little about them. Children and youth, in Africa as elsewhere, have often remained our 'silent others', our voiceless enfants terribles. (De Boeck & Honwana 2005:2)

Introduction

As part of the theological task of developing a publicly oriented ministry that will do justice to the social plight of children in Africa, this article proceeds from an appreciation of the new 'hermeneutics of listening' that is advanced today by an interdisciplinary movement of scholars from the disciplines of practical theology, theological ethics and religion studies. In a way similar to the new hermeneutical position adopted by this movement, the article advances the thesis that listening to children in the process of practical theological interpretation will offer newly found opportunities for Christian theology and the church to contribute to the well-being of children as a local, national, continental and global public concern. Listening to children's voices does not only address questions about social justice, the participation rights of children and children's position as active agents in society; the act of listening to children is also about the survival and development of children, caring for them and protecting them from living conditions that dehumanise them - a way of promoting the human dignity of children as the image of God in each human being. And last but not least, it is also about communicating and being in relationships with children in order to realise supportive and companionable interactions in adult-child spaces.

Although constructions of childhood change over time, there are also clear differences between societies on how children are viewed and treated. Even within societies there are considerable differences that impact on how children experience childhood (Ansell 2005:8-9). Whilst children in many of these diverse contexts have positive experiences of belonging and of having their human dignity respected, there are even more who are practically invisible and excluded, whose voices are ignored, and whose needs are not attended to (De Boeck & Honwana 2005:1-2; cf. UNICEF 2005). In particular, it is this reality of children's lives in diverse contexts, together with the appearance of new paradigms of social thought about childhood, which challenges theological and religious scholarship to become aware of what it can contribute to the academic and public debate.

Since the beginning of the 2000s a scholarship that focused anew on children and childhood has emerged within the fields of Christian theology and religion studies (cf. Bunge 2006:549-57). From the recent developments in this scholarly reflection and particularly its new openness towards the social sciences, it has become evident that there is a dynamic interplay between the rich resources within what has become to be known as the interdisciplinary social science field of childhood studies, on the one hand, and theological and religious scholarship, on the other. This has been a development that has not only stimulated practical theologians, theological ethicists and scholars of religion to revisit simplistic views of children and allow their disciplines to be transformed by childhood studies, but also to reflect anew on the contribution that their disciplines could make towards alternative views of children and their citizenship rights and agency role in society (see Wall 2006, 2010; Wyller & Nayar 2007).

One of the positive outcomes of this new interdisciplinary engagement with childhood studies is the conceptualisation of the new 'hermeneutics of listening' with regard to children in theological and religious scholarship. Accordingly, this article similarly wants to contribute to the ongoing advancement of this hermeneutical position and, by implication, the conceptualisation of a mode of ministerial formation that will do justice to the social plight of children, yet specifically with the context of Africa in mind where, in the words of Filip de Boeck and Alcinda Honwana (2005:1), children and youths are 'often placed at the margins of the public sphere and major political, socio-economic, and cultural processes', in spite of their central place in societal interactions and transformations.

In line with the above-mentioned goal, the following discussion will more specifically engage with the new 'hermeneutics of listening' that is today being conceptualised in the new interaction between theological and religious scholarship, on the one hand, and childhood studies, on the other. This will be done from the supportive position of a particular practical theological understanding - one that embraces the idea of a publicly oriented practical theology and that entails a multitude of interpretative tasks. From the vantage point of the conceptual position presented by this scholarly movement, the article will move to a more pertinent evaluation of the unfolding of this line of thinking in the scholarly context of Africa. In a further development that narrows the African focus to South Africa, the results from a recent empirical investigation amongst members of the Society for Practical Theology in South Africa (SPTSA) will be discussed in particular to determine the extent of this group's shift to the new line of thinking. This will lead to a concluding statement in the article about the way in which the new 'hermeneutics of listening' to children could still be seen as an important ongoing challenge, in the light of its overt practical theological interest, not only for practical theological scholarship in South Africa but also within the larger context of Africa.

The new 'hermeneutics of listening'

Practical theology concerns itself with interconnections, relationships and systems in which ministry, in the form of religious communicative actions, takes place (Osmer 2008:17; Pieterse 1999:411-126). The process of seeking to understand systems within systems is an important part of being engaged in practical theological interpretation. Practical theological interpretation can therefore be seen as deeply contextual. This interpretive and contextual nature of practical theology has certain implications, one of which is to reflect on the well-being of children in church and society (cf. Osmer 2008:17). Firstly, to focus exclusively on children as individuals is too limited. Children are grounded within culture, history, communities, families, relationships and systems. If this reality is ignored, the wider circumstances which contribute to the adversity that some children experience will not be effectively addressed (cf. Ansell 2005:28). Secondly, it is also necessary to devote attention to the interconnection of various forms of ministry, with and through children. The question can be asked how the position of children in liturgy and teaching in congregations is connected to the spirituality of adults, which in turn impacts on the way children are treated in adult-child spaces. Thirdly, Osmer (2008:17) explains that 'congregations are embedded in a web of natural and social systems beyond the church'. When children are abused, neglected and discriminated against in society, the academy and the church therefore have to co-construct ministries of advocacy, care, teaching, preaching and service to be acting in the best interests of those children and their right to social justice.

One very important way towards ministerial formation in the best interest of the child, as the notion of a 'hermeneutics of listening' in fact clearly suggests, is to listen to the voices of children (cf. Diouf 2005:232; De Boeck & Honwana 2005:1-2; Reynolds 2005) in the process of practical theological interpretation. In his book Osmer (2008:31-78) presents the 'descriptive-empirical task' as a form of 'priestly listening', grounded in a 'spirituality of presence'. This task is concerned with the question 'What is going on?' (Osmer 2008:33) and information is accordingly gathered to help practical theologians discern patterns in particular episodes, circumstances and contexts. The focus in this task is to attend to others in their particularity within the presence of God. As Osmer (2008:33) states: 'It has to do with the quality of attentiveness congregational leaders give to people and events in their everyday lives.' Priestly listening, therefore, is an activity of the entire Christian community. When adults listen to children, they therefore do not only make it their responsibility to remain in touch with the well-being of children as this is experienced by children themselves, but they also take responsibility for the responsibility of children to listen to and treat others respectfully (cf. Dillen 2006:245).

A second task of practical theology that Osmer (2008:79-128) explains is the 'interpretive task' whereby practical theology draws on theories of the social sciences to better understand and explain why certain patterns and dynamics occur. In line with this premise - when it comes to understanding what is happening in the lives of children and what the implications of listening to children are - drawing upon the field of childhood studies therefore becomes very important because of the way this field has newly stimulated a shift in social thought about childhood and the way children should be appreciated in society (cf. Van Oudenhoven & Wazir 2006:123; O'Neill 2000:7; ed. Wyse 2004). In the early children's rights instruments and academic theories of childhood, childhood has been primarily conceptualised as a life phase in which children are vulnerable, victims and at risk, and therefore in need of care and protection from others (cf. Ansell 2005:8-37; Dillen 2006:237-250; Montgomery 2003:187-219). In contrast to this position, however, the idea of children as active agents who have their own contribution to make within the spheres in which they find themselves is today advanced by scholars in the childhood studies movement (cf. Ansell 2005:21; Wall 2006:523-548; Montgomery 2003:215). This emphasis on agency and participation confirms anew children's cultural and social position as citizens at all levels of society (Wyller & Nayar 2007:7; De Winter 1997; Mokwena 2001; Roche 2004:475-493; Yates 2010:165-166).

To enhance children's participation and citizenship in society does not only entail capacitating children with resources to voice their opinion, but it also implies that adults need to listen to the voices of children in such a way that they are committed to doing more than just to hear what children are saying (Bray 2011:33). The challenge is to use that knowledge in the process of decision-making and to ensure dignity and equality in the relationship with children (Bray 2011:33). It is thus clear that one of the key principles of child participation, as expressed in Article 12 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, is to listen to children (Kirby & Woodhead 2003:245). A 14-year-old girl, Nonjabulo, indicated one of the central challenges of child participation when she introduced a live radio broadcast one Saturday morning in March 2009:

You may give a voice to the children, even give them a very big platform, but if adults don't stop to listen to what the children are saying it is as good as no voice. (Meintjes 2011:65)

To illustrate more pertinently the influence that the above line of thinking has had on theological and religious scholarship, two initiatives that were launched in recent years in response to the question about the rights, agency and citizenship of children can be highlighted as good examples. In 2005 the University of Oslo in Norway acted as host for an important international and interdisciplinary conference. This conference, announced as 'Childhoods 2005', attracted academics from roughly 95 countries (Bunge 2006:559; Wyller & Nayar 2007:13). One of the sessions at the conference focused on spirituality and religions within the context of children's rights. The central question discussed was how a religious language can be developed where the otherness of children is respected and their human dignity recognised (Wyller & Nayar 2007:13). As a direct result of this conference, the volume The Given Child: The Religions' Contribution to Children's Citizenship, edited by Trygve Wyller and Usha S. Nayar, was published in 2007.

This book strikingly makes an appeal to all religious traditions regarding their responsibility in dealing with conditions worldwide where many children are excluded from full cultural and social citizenship and deprived of basic universal human rights (Wyller & Nayar 2007:7-8; see e.g. Bunge 2007:27-50; Teipen 2007:51-70; Nayar 2007:71-81). These conditions are described by the authors as morally and politically scandalous, whereas the title The Given Child reflects an emphasis on talking about children as gifts of God. The authors make recommendations on how this 'gift discourse' can be developed further in the context of children's rights and citizenship. It is argued that this discourse is not critical enough to address the challenge of children not being fully recognised as citizens (Wyller & Nayar 2007:8).

All contributors to this publication agree that the different religions can make a meaningful contribution towards promoting children's rights and citizenship, by adhering to a few conditions. Firstly, the religions need to develop a more sophisticated and critical discourse regarding their own notion of 'the child as a gift' (Wyller & Nayar 2007:8). In this regard John Hull (2007:185-192) argues in his chapter that referring to 'the child as gift' has to be connected to the idea and concept of creation. Creation itself is given. Therefore, not only the child, but everything, the whole world is a gift (Hull 2007:188). For Hull, however, it is important to understand the idea and act of creation not only in the past tense, but to acknowledge that creation also involves the present and future tense - creation is a continually given gift (Hull 2007:189-190). For him then, the implication of these insights for an understanding of the child is grounded in the belief that the child is, like any other person, a co-creator of a more humane society, in the present but also symbolising the future. He argues:

God creates through creating creativity. We also are creators, and the child is a creator. Genuine creativity is a mirror of the divine creativity. Human creativity, of course, is narrowed by the human finitude, and constrained by the inheritance of the previous creation. Nevertheless the creativity of the child possesses originality, freedom and delight. It is the same creativity as appropriate to a created creativity as the supreme and unsurpassable creativity possessed by God. ... This means that any attempt to suppress the creativity of the child is blasphemous. I am not referring to attempts to nurture, or to guide, or to teach the child how to be creative, but I am speaking of the forces that would translate the child into a consumer, a commodity, a creature of desire rather than a creature of creative love. ... Finally we should consider the concept of creation as gift not only in the past tense and the present but in the future. . In the light of this, we may regard the child as a symbol of the future. The child, the young child, in its playfulness, its complete reliance on its family, in its freedom from the money culture, is indeed something of an ideal in which we seek to guide our whole society. So when we nurture the child in its creativity, we also nurture ourselves, as we move all humanity on tiny steps forward. (Hull 2007:190-191)

For the authors of The Given Child the second condition for religions to meet in order to contribute meaningfully to the citizenship of children is to focus on situated, social practices, whilst taking note of the intersubjective relations in their own practices (Wyller & Nayar 2007:8). One conclusion in this publication is that, as long as the religions continue to be committed merely to abstract principles regarding children and their welfare, they will not be able to contribute to children's rights in a positive way. The challenge for religions and human rights movements, according to the editors, 'is to develop both an awareness and a practice for the otherness of children' (Wyller & Nayar 2007:8).

Thirdly, and closely related to the second condition, it is also argued in the book that whilst the religions ought to decrease particular traditions and practices, they also need to develop the potentialities within their own tradition, that is, to create life worlds, situations and practices 'where the experience of participation, belonging and relationality is substantially present' (Wyller & Nayar 2007:10). Indeed, to move at this point beyond the direct argumentation found in The Given Child, one could well observe how this condition links with the 'normative task' in the process of practical theological interpretation that Osmer (2008:129-173) identifies. In the normative task ethical principles, guidelines and rules are formed and assessed according to which individual and collective choices and actions can be directed towards transformation. Translated in terms of the challenge to listen to children and in so doing promote their participation, this demands that truth claims and values are developed that will, from a Christian point of view, lead theology, church and society to move beyond the oppressive legacy of 'adultism'. Adultism is explained by Bonnie Miller-McLemore (2003:158) and Annemie Dillen (2007:42) to be analogous to the terms racism and sexism, as an arbitrary distinction that is made on the basis of an age category. The concept refers to everything that leads to the humiliation of children and not appreciating (the otherness of) children as children.

This brings us to the second of the two initiatives mentioned above, which took place in 2007, when the Catholic University of Leuven in Belgium hosted an international research seminar entitled 'Children's Voices: Children's Perspectives in Ethics, Theology and Religious Education.' This theme reflects the focus on listening to children's voices and perspectives, and integrating them into ethics, theology and religious education - thereby emphasising the appreciation of children's agency and contributions - as well as on practising theology in partnership with children. Experts in the social sciences, ethics, Christian theology and religious education were brought together to enter into dialogue and reflect on the three core questions of the seminar, namely why it is important that the voices of children are heard; what the voices of children would express; and what the voices of children mean for theology, ethics and religious education (Dillen & Pollefeyt 2010:4-5).

The seminar also led to a publication, namely Children's Voices: Children's Perspectives in Ethics, Theology and Religious Education, edited by Annemie Dillen and Didier Pollefeyt (2010). The editors of this book reflect critically on the dualistic idea of some people that society is bad for children and that Christianity can offer a positive counter-narrative. Dillen and Pollefeyt (2010:3) argue that this dualistic view does not hold for several reasons. When confronting such views, it is important to take the ambiguous and multi-layered character of both Christianity and culture into account. There is, for example, ample evidence that suggests that the Christian tradition is not always so appreciative of children. However, there are also good examples of how children are treated respectfully in secular society and how spaces are created for children to participate in. Therefore, it can be suggested that society and culture, stimulated by the secular children's rights movement and the social theories of childhood studies, have a great deal to teach Christians in the field of children's participation and agency. It is this suggestion that laid the basis for this book's theme on children's voices (Dillen & Pollefeyt 2010:3). The publication dealt with the question of whether Christianity does in fact take children's voices seriously. Furthermore, attention was also given to the question: 'What does Christianity have to say in this domain, and what would be the result of an interdisciplinary dialogue on the question: are "children's voices" really heard?' (Dillen & Pollefeyt 2010:3).

It is made clear in this book that classical Christian theology can only profit by taking seriously the current reflection on children and their own voices. The discussions clearly demonstrate the relevance of well-balanced and interdisciplinary reflection on children for Christian and social practices of adults with children, and how these practices can positively influence theology (Dillen & Pollefeyt 2010:4). A further benefit of the book is that it contains a practical theological perspective on children, whilst the responsibility of churches towards children is also dealt with.

From the above two initiatives and in the broader discourse of childhood and religion it becomes evident that, when listening to children, it is possible to identify and embrace what children have to offer and contribute in the spaces in which they find themselves. This act of giving and the sharing of resources and strengths are often overlooked in understanding children's processes of coping with adversity. And it also happens that theologians mostly undervalue the resiliency and agency of children in their effort to address the problems that children encounter according to a normative understanding of what childhood should be.

From the perspective of listening to children, Christian theologians are confronted with the issue of what images and messages they project of children in society. The message that theologians communicate about childhood can either strengthen existing destructive stereotypes and prejudices about children, or it can provide more positive views about them. The question of the representation of children is specifically relevant to the way African childhood is often presented to the outside world, sometimes without listening to the insider's perceptions.

The new 'hermeneutics of listening' in the African context

In his recent publication, Saved by the Lion? Stories of African Children encountering Outsiders (2011), Johannes Malherbe - a pioneer in the development of an African theology of childhood - mentions his excitement about the increasing awareness of, and involvement in, matters of direct relevance to children. Yet, in the same breath he also notes that he remains seriously concerned about the limited involvement and influence of Africans in the global agenda dealing with child issues. Even on a national and local level, it were often outsiders who took the lead in initiatives aimed at ways of assisting Africa's children (Malherbe 2011:8). To his amazement he found the African voice mostly absent in the majority of cases where resources for Africa's children and childhood in Africa were discussed.

Apart from this absence of African voices as far as the well-being of children in Africa is concerned, for Malherbe (but also other scholars - cf. Ansell 2005) another reality to be faced is the negative way in which Africa and its children are often portrayed by the media to the outside world (Malherbe 2011:3-4; see also Ansell 2005:28-29). These negative perceptions about Africa have had such an impact that they have become entrenched in African culture, religion, science, philosophy and history (Malherbe 2011:4). In contrast, Western culture has mostly been portrayed in a favourable light and associated with freedom, justice, equality and emancipation. It is precisely against this backdrop that Malherbe's book 'aims at contributing to the liberation of African children from the accumulated weight of negative perceptions, attitudes and actions' (Malherbe 2011:9).

Indeed, it can be contended that the problematisation by Malherbe not only raises the question of the extent to which the new 'hermeneutics of listening' explained above can serve as a vehicle to recognise and value children in Africa as active participants in constructing their own life worlds. In a very important way it also calls for a consideration of the extent to which existing religious and theological initiatives on the African continent have themselves made a contribution to this end. We therefore pay particular attention to the articles in two special journal issues from the African continent in the last decade devoted to the issue of children.

In a special issue published in November 2002 the JTSA focused on the theme 'Overcoming Violence against Women and Children'. A number of issues were subjected to theological and ethical interpretation, such as the effect of HIV and AIDS on children in Botswana, the sexual abuse of children in South Africa, holistic ways to empower Africa's children and youths, and the silence of the churches with regard to gender-related violence and HIV and AIDS. Against this background the proposition by Musa Dube to utilise a theology based on children's rights in the struggle against HIV and AIDS in Botswana could be mentioned first. She stresses the importance of establishing a biblical basis for making children feel welcome in church and society. For her this essentially implies that wherever children feel uncomfortable and wherever their rights and needs are not met, including in the church, it means that 'not only [are] they unwelcome, but also God and Christ' (Dube 2002:32).

Besides her biblical interpretation, Dube's contribution stands out for making a direct connection between the welcoming of children and acknowledging not only their needs but also their rights. It is strange, therefore, that in this article she continues by only discussing children's needs, the critical factors in caring for them and the supporting services provided by non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and faith-based organisations (FBOs) (Dube 2002:34-41). Thus, although mentioning the importance of children's rights and a rights-based theology (Dube 2002:32-33, 41), a more pertinent discussion of children's participation as social agents in the struggle against HIV and AIDS is sorely missing from Dube's contribution.

Yet Tinyiko Maluleke and Sarojni Nadar (2002:4) pointed out that the real strength of the Journal of Theology for Southern Africa (JTSA) special issue was the fact that the authors were advancing beyond a merely theoretical study. They were also arguing about the need for concrete strategies to overcome the precarious situation of violence against women and children. However, it is unfortunate that one needs to comment at this point that the strategies identified in the various articles are rather exclusively based on the way adults could deal with such violence, without acknowledging the ways in which children as social agents could themselves contribute.

To be more specific, although Musimbi Kanyoro (2002:69-77) focuses in her article on 'Holistic ways to empower Africa's children', the kind of empowerment envisaged by her has mostly to do with the instruction children need to receive in order to protect themselves (Kanyoro 2002:72-77). Similarly, in the article by Mpine Qakisa (2002:79-92) about 'Reaching young people through the media in the age of aids [sic]', the emphasis on educating children and young people is certainly important in protecting and safeguarding them. Once again, however, only casual reference is made to young people themselves as sources of information when Qakisa (2002:90) states: 'Using ordinary young people who go out and ring doorbells as medical missionaries may be more effective than using an official figure.' Finally, in her article on 'Gender, Violence and HIV/Aids' Beverly Haddad (2002:93-106) stresses that the voices of women in communities and the academy should be taken seriously. In this way she strongly advocates for a hermeneutics that listens to women's voices, but omits any similar approach to children. Whilst stating the need of children to be protected and the moral obligation of churches for advocacy and lobbying within communities in order to counteract the rape of children (Haddad 2002:104), the additional perspective on children's strengths, assets and voices in the discourse on their own participation and agency is sadly lacking in this article - as in this issue of the journal as a whole.

In the case of the second special issue, the African Ecclesial Review of 2004, the discussions focus particularly on the issue of child labour. The challenges that child labour poses to society and church - inter alia the violation of children's human dignity - are the specific point of focus. In this regard Constance Bansikiza (2004:139-160), in his article on 'Child labour challenges to society and church in Africa', presents the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC) (1989) as the normative instrument promoting the indivisibility of children's rights. To this end he stresses the fact that the UNCRC established the right of the child 'to be an actor in his/her development, to express opinions and to have them considered in the making of decisions related to his/her life.' However, he also clarifies this by contextualising the occurrence of child labour, stressing the positive value of child labour within the context of the family, but also its exploitative forms as they occur in Africa (Bansikiza 2004:142-145, 146-148).

Bansikiza's article stimulates thinking about the way in which traditional values in Africa are supportive of child participation and agency. One limitation, however, is that he does not respond to the argument made at the beginning of his article that children are valued as actors in their own development, as social agents with a voice that needs to be considered in deciding what is in the best interest of the child, as indicated by the UNCRC. Therefore, it would be interesting indeed to see how Bansikiza describes the nexus between agency and the phenomenon of child labour.

The article by Deusdedit Nkurunziza (2004:121-136) on an 'African theology of childhood in relation to child labour' also deserves a positive appraisal. In this article the author provides a detailed description of a normative theological basis for acknowledging children as important stakeholders and subjects in God's kingdom and in society. On the basis of an African theology of childhood he advocates the appreciation of the dynamic value of childhood and for the treatment of children with love and respect. Respect for the human dignity of children is linked to the human rights of children and the importance of supporting this secular movement (Nkurunziza 2004:131). He strongly urges churches in Africa to care, and take full responsibility for their children. He states that functional pastoral programmes targeting the child should include interventions on behalf of children, and by children for children. Hereby he acknowledges the agency role children can play in promoting the well-being of children (Nkurunziza 2004:136).

Although Nkurunziza's contribution to an African theology of childhood can be highly valued, it is, however, open to criticism in one respect. On the one hand, he emphasises the human dignity and dynamic value of childhood. On the other, he argues that the future of society is dependent on the quality of life accorded to its children through the social system of education. In the same vein, he states that a church without children is a church without a future. It is therefore in the future interest of society and the church to invest heavily in the well-being of children (Nkurunziza 2004:131, 133). Whilst this is undoubtedly true, one should be on the guard against a one-sided approach - in this case an emphasis on the beneficial future of society and the church (the 'well-becoming approach') without simultaneously stressing the benefits of investing in children for children's own sake in the present (the 'well-being approach'). In terms of this distinction, it therefore remains crucial to keep these two approaches in balance in order to best serve both Africa's children and African society (cf. Bray & Dawes 2007:15; Yates 2010:158). Furthermore, by also focusing on the present well-being of Africa's children, their own voices in determining what is in their best interests, as well as their contribution to society, can be newly appreciated.

It can be concluded that, apart from the few publications discussed above, very little has been done so far in the field of academic theology in Africa on the issue of children and childhood. In this regard, it is heartening to mention that, as the first of its kind, an international academic conference on the theme, 'African Christian Scholars and the Plight of the African Child' was held from 09 to 11 November 2011 at the Daystar University in Kenya, organised by its School of Human and Social Sciences. The symposium focused on the role and potential of academic institutions, child-focused organisations and churches in dealing with emerging risks and the challenges children in Africa face. At the same time, a striking feature of the symposium was that it focused directly on the question of promoting children's rights. To this end the African 'child-at-risk' was placed at the centre of the policy agenda and research, whilst the emphasis also fell on the holistic development of children. As stated in the overview of the symposium's brochure, although the past number of years showed an increasing awareness and acknowledgement of children as a strategic group in transforming their own world and creating their future, the actual promotion of their rights was critically important in supporting social justice and building a sound society. In spite of programmes aimed at empowering children and promoting their rights, the overview concluded that there was still a lack of sufficient knowledge and empirical evidence to mobilise innovative policies and programmes for effectively addressing the needs of African children-at-risk (Child Rights International Network n.d.; Daystar University n.d.).

In concluding our own overview of this section, we want to point to one last theological publication amongst the few that have been published in recent years on children in the social context of Africa: an article by Amanda Richter and Julian Müller (2005) entitled 'The forgotten children of Africa: Voicing HIV and Aids orphans' stories of bereavement: A narrative approach'. This article certainly offers an example of research reflecting the new 'hermeneutics of listening' to the voices of children. As mentioned by the authors, their research formed part of a journey to trace frightened children who were mourning the loss of their parents through AIDS and to assist them in telling their stories of bereavement. The methods used were to ask three Zulu children orphaned by AIDS to tell their stories individually (Richter & Müller 2005:11). And in doing so, the article makes an important contribution to communicate respect and hospitality towards children, letting their own voices be heard, and thereby deepening understanding of the world children live in, as experienced by them.

At the same time, however, an appreciation of the article by Richter and Müller also leads us to point to a predominant feature in the current examples of theological research on children in Africa, namely that the topic of children is most often brought up when society is challenged by traumatic experiences such as violence against women and children, child poverty and destitution, child labour, or HIV and AIDS. In view of the normative theological perspective on children as created in the image of God and therefore worthy of human dignity and being acknowledged as co-creators in an ongoing creation story, these discussions about the crises and problems children have to cope with should be complemented by positive stories about children's ability to endure hardship, withstand severe socio-economic challenges and act in their own right as agents of social transformation.

Perspectives from a South African project

In this section the discussion now attends more pertinently to the results from the empirical investigation mentioned in the introductory part of this article. This investigation formed part of the doctoral research project of one of the authors of the article (H. Yates) and was conducted at the end of 2011 under the theme: 'The Promotion of Children's Rights: A Practical-Theological Enquiry.' More specifically, the investigation was conducted amongst registered members of the SPTSA, aiming to determine whether and in what way practical theology as representative of the first theological public, namely the academy, can make a contribution to the promotion of a discourse and practice on children's rights in South Africa. An appropriate selection of the results of this investigation is subsequently utilised to indicate the extent to which it reflects a shift in thinking similar to that of the new hermeneutical movement discussed above.

The research project was structured according to the mixed-method research design, combining quantitative and qualitative research methods (Creswell 2009:204). A sequential transformative strategy was followed in accordance with the different research methods to structure the project in two phases, with the theoretical lens of Richard Osmer's theory of practical theological interpretation overlaying the sequential procedures (Osmer 2008; cf. Creswell 2009:212). The motivation for using this design and strategy was to serve the positioning of children's well-being and rights within the process of practical theological interpretation. At the same time, through following this design and structure, the research project could apply a mode of practical theological interpretation that, in terms of the subject matter, would strive to stimulate a call for action on behalf of those children who are victims of inequality, discrimination and injustice. The project was approved by the Ethics Committee of Stellenbosch University.

Quantitative phase

The research began with a broad quantitative survey through questionnaires that were sent electronically to registered members of the SPTSA. Out of the 102 members who received an invitation to participate, 51 eventually participated in the study. The purpose of the quantitative survey was to ascertain to what extent participants agreed that children and their overall well-being and rights should be a focus in practical theological interpretation and in what way practical theology could contribute to the promotion of children's well-being and rights. This quantitative phase thus served as a process to raise the awareness of children, their well-being and rights, and to explore the areas on which the participants had consensus. The questionnaire was structured according to the four tasks of practical theological interpretation as explained by Osmer (2008). Section A focused on the contribution of practical theology to the empirical description of the realities of children (Task 1: The 'descriptive-empirical task' - 'What is going on?' [Osmer 2008:4]). Section B aimed at exploring the opinions of the participants on the utilisation of children's rights as a perspective in approaching children in practical theology (Task 2: The 'interpretive task' - 'Why is this going on?' [Osmer 2008:4]). Section C dealt with the development of a normative theological perspective which can guide Christians' views on and treatment of children and at the same time engage in dialogue with other disciplines (Task 3: The 'normative task' - 'What ought to be going on?' [Osmer 2008:4]). And Section D explored opinions regarding the contribution of practical theology to the promotion of children's rights in South Africa (Task 4: The 'pragmatic task' - 'How might we respond?' [Osmer 2008:4]).

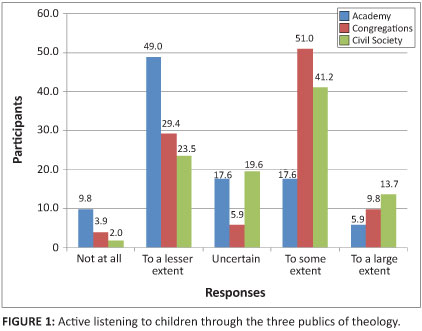

The results from the questions in Section A indicated that the participants to a large extent agreed that practical theology had a contribution to make to the empirical description of the social realities of children. In response to Question 1, which tested their perception on whether practical theology had a contribution to make to the improvement of the welfare of children in South Africa, a 100% positive answer was received. In response to Question 2, which tested their perception on whether practical theology had a role to play in describing the contextual factors affecting the welfare of children, a similarly affirmative response was given. However, in response to Question 3, which inquired whether they were aware of recent (2005-2011) practical theological research on the living conditions of children in South Africa, only 47% answered positively. The response to Question 3 can be interpreted that either the participants were not aware of recent research about children, or as a possible lack of focus on children in practical theological research. The response to this question was in a sense also contradictory to the 100% positive response to the first two questions on practical theology having a contribution to make to the welfare of children and the description of contextual realities. Importantly in the context of this article, this same contradictory result also appeared in the responses to Question 7, which tested the participants' perceptions on the degree to which the different theological publics actively listen to children's perceptions of the events in their everyday lives. The response to this question is summarised in Figure 1.

A striking feature in the percentages shown above is that the academy was evaluated as hardly (9.8%) or only to a lesser extent (49%) listening to children. As opposed to this, congregations as well as civil society were evaluated far more positively in this regard. A total of 43 participants responded as being uncertain on the scale. This high number may indicate that the participants did not understand the question, or could not relate the application of the three theological publics to listening. Yet the conclusion can be drawn that there are discrepancies between what participants perceive practical theology as academic discipline can actually contribute to the well-being of children and how the active listening to children is realised in practice.

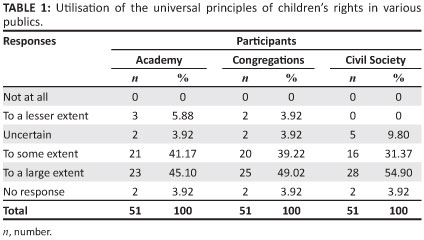

Section B explored participant's opinions on the utilisation of a children's rights perspective in dealing with the issue of children in the broader subject of theology. Here Questions 9 and 14 are relevant. Concerning Question 9, 94% of the participants responded positively to the question of whether the broader subject of theology should make use of the perspectives of other disciplines in interpreting the context of children. In Question 14 participants were asked about the utilisation of the universal principles of children's rights - namely non-discrimination, the best interest of the child and the right of children to be heard - as a perspective to test current practices and norms in the various theological publics. The responses are listed in Table 1.

Although some of the participants responded that the principles of children's rights could be utilised only to a lesser extent in the academy and congregations, the majority indicated that these principles were useful to some extent or to a large extent in the academy, congregations and civil society. It may well be concluded, therefore, that this question on the utilisation of children's rights' principles would perhaps have been more easily understood if participants had been asked to judge concrete case studies with the help of the children's rights principles. Still, in those instances where participants responded positively to the utilisation of children's rights, they in fact acknowledged the value of not discriminating against children on the basis of their age or any other form of 'otherness' and listening to their voices in matters pertinent to their daily lives. To recognise these principles as useful in testing current practices and norms, participants indirectly associated themselves with universal values that inform the new 'hermeneutics of listening' to children. Therefore it is interesting to see that 96% of participants agreed that children's rights could provide guidelines in the way in which adults could enter into partnership-based relationships with children, in which children are respected, valued and listened to.

Section C, aimed at exploring participants' opinions on the development of a normative theological perspective on children and their well-being, is the part of the questionnaire in which the highest level of consensus was reached. The large majority of participants agreed that theological perspectives on children, ethical norms and best practices in the Christian faith can normatively guide Christians' views and treatment of children. In this section participants were given the opportunity, through the use of open-ended questions, to elaborate on the different theological perspectives on children listed in the questions. It is interesting to observe how one of the participants listed 'children as active participants in church and society' and 'children as agents of change in their families, churches and society' as normative perspectives in the consideration of children. One of the other participants again identified the perspective that 'children will someday become active participants in church and society' as a simplistic view of children.

In Section D, which aimed to explore the opinion of participants on the contribution of practical theology to the promotion of children's rights in South Africa, a very large majority of the participants agreed to the various statements that practical theology could contribute to the promotion of children's rights in the context of the academy, church and society. This contribution of practical theology refers to the tasks of describing the living conditions of children; interpreting the experiences of children in their context with the help of perspectives from other disciplines; developing a normative theological perspective on what should happen in the world of children; contemplating the practical treatment of children in church and society; and integrating academic training with grass roots level involvement in the promotion of children's quality of life.

It can be concluded that the above quantitative survey had its limitations in that the sample consisted mostly of White Afrikaans-speaking men in their forties and early fifties. As a result of the current membership profile of the SPTSA, women and people from diverse cultural and age groupings were underrepresented in the sample, whilst the composition of the sample also reflected a shortage of persons representing the designated groups of South Africans in the society's membership. Another limitation could also be the fact that some questions in the questionnaire only gave a 'yes' and a 'no' option for the participant to indicate a response.

Yet the findings of the quantitative section of the research as a whole nevertheless suggest that the majority of participants did envisage a contribution from practical theology in enhancing the well-being of children, on the basis of a normative theological understanding of children and how children should be treated. However, as the discussion above of the response to Question 7 also suggests (see Figure 1), it cannot be assumed that, if people can identify with certain theological perspectives on children, this necessarily means that children's voices will be heard. Although the theological perspectives on children given in the questionnaire were all evaluated in the same positive manner, the question can be raised whether some perspectives were not more influential than others in forming an understanding of children. One could therefore ask whether the question should not rather have been how the polarities inherent in the overall theological framework (as represented by the totality of perspectives) should be held in tension with one another. For example, the acknowledgement of polarities should involve that children are recognised as part of the broken (sinful) reality, but also created in the image of God; that children as developing human beings require directive education, but in other instances also deserve to be upheld as models of faith; that children are gifts to their parents, but in other instances are also the orphans and excluded from society (see Bunge 2006:563-568). Indeed, this acknowledgement of polarities should raise the further question of which perspectives on children in the South African context weigh heavier and what their influence is on the way or extent to which children are listened to.

Qualitative phase

In the second phase the quantitative data were further explored through the conducting of semi-structured interviews by H. Yates, with selected academics, registered as members of the SPTSA and lecturing in practical theology at South African universities, during September-October 2011 in Stellenbosch, Pretoria, Pietermaritzburg, Bloemfontein and Potchefstroom. Interviews were conducted up to the point of data saturation. All interviews were verbatim quotes in Afrikaans that we translated into English - except interviewees A and D that were originally in English. Most respondents were Afrikaans speakers. The main question that the participants were asked was to explain the current and potential contribution of practical theology to a discourse and practice that promotes children's well-being and rights.

The data gathered with regard to the above question were subsequently unpacked in order to give a more informed description of the extent to which a shift might be evident from a position that views and treats children primarily as victims to one that views children as social agents with voices that need to be heard. This was done through a synthesis of the most frequent and significant themes that came to the fore in the analysis of the data.

Theme 1: Children and their well-being constitute a marginal theme in practical theological interpretation in the context of the academy

It became fairly clear from the discussions that participants were of the opinion that children and their well-being were not receiving much attention in practical theological interpretation. Children and their well-being were described by participants as 'not a very strong area of focus'; as 'not prioritised in research work'; and as 'a neglected conversation'. The following two responses illustrate the marginal position of children in practical theological reflection:

'Very little research exists in practical theology that focuses exclusively on children at academic and tertiary level. A complete poverty exists in this regard. This relates to the lack of interest in youth ministry as a whole.' (Interviewee K)

'I think that local congregations are directly confronted with the reality of children. However, because we find ourselves in a kind of protected space in the academy we make our own decisions on what we want to conduct research. And I do not believe that children, children's rights or child welfare represents a prominent question for us.' (Interviewee F)

In practical theology it is important to critically explore the factors underlying a certain practice. The underlying factors that participants identified for children being a marginal theme in practical theology included the lack of expertise in this field, time and curriculum constraints, the prominent role that independent organisations play in providing training in children's ministry, and the lack of appreciation of research on children's issues as a proper academic contribution.

Participants problematised the fact that the issue of children constituted a marginal theme by highlighting some of the consequences:

'Thus only one module in three years. The module on youth ministry touches on children but it is not as specific. At the end of that year you have one children's ministry block; that is a week during which you get exposure. We experience that the students do not find it relevant. The majority of the classes do not take the classes seriously.' (Interviewee A)

'Church training that is academic training, it seems to me, does not help students to adequately recognise the realities of children.' (Interviewee K)

'When the realities and interests of children do not find a place in the curriculum, then little post-graduate research is done.' (Interviewee K)

'The value of the child, the humaneness, the identity of the child have surpassed us and therefore we are also not worried whether as adults we should be educated about the whole issue of children. I think that in the theological discipline as a whole we have received very little about this. Many ethical questions do not focus on the child at all. And if you take a closer look at dissertations you also find very little information' (Interviewee H)

Theme 2: Significant attention to a normative basis for viewing and treating children is lacking

The responses from participants suggest fairly strongly that the normative basis that should guide practical theologians' views of children is lacking and that this lacuna has an impact on the perspectives formed in practical theological research and training. This deficiency was, for instance, expressed by some participants as follows:

'Currently I should say that this is one of the shortcomings for me, that not enough attention is given to what God's revelation is about the child . where the child comes from, the identity of the child, the acts of the child, those things are actually all interrelated with how that child has been created by God and how God also sees that child. How does the child look through the eyes of God?' (Interviewee H)

'We have a church theology, which is the alpha and the omega in how we understand theology and also God's role, and we diminish the role of children in our theology . we hold fast to a church theology which, for me, is actually about power and how we can sustain it. And the role of humans and children therein does not find any expression.' (Interviewee F)

'How we have been formed theologically, even in terms of our thoughts, therein the child and the role of the child do not exist.' (Interviewee G)

The responses presented above suggest that a sound theological perspective on children and childhood is not only lacking within the context of the church and theology, but that there are also deficiencies in the theological formation of practical theologians that need to be addressed to fully include children in practical theological interpretation. The emphasis on a church theology can lead, for example, to children being viewed one-sidedly as members of the church and not in the first place as human beings in their own right. This furthermore suggests that there is a lacuna in terms of a practical theological anthropology of childhood that emphasises the humanity of the child.

Theme 3: When the theme of children and their well-being is dealt with, it is mostly still in a fragmented manner

In close relation to the above perspective on theological deficiency, the responses from participants also suggest that the limited theological understanding of children and childhood is reflected in the fragmented and sporadic way in which the issue of children is included in the practical theological curriculum:

'We have fragmented the discipline of theology to either focus on children or young people or adults and married people, etc. We break up our whole church system in this manner.' (Interviewee F)

'There has been a bit of a one-sidedness in our practical theology around the whole issue of catechesis. You thought that you could form a young person by merely working with his [sic] head and letting him [sic] memorise the faith truths ... that it becomes part of his [ sic] life in this way.' (Interviewee H)

'Besides your focus on catechesis, the interactive interest in the involvement with children and what happens in that part of society is very low. Let us say, it should be rather obvious that one ought to support youth ministry as a holistic, integrated ministry. Yet, when we take a look at congregational ministry this does not occur.' (Interviewee E)

'It has always been my fear that one becomes stuck in compartmentalised ways of thinking - that you follow a module on child and youth ministry and then you are finished with it and become a minister who only works with adults.' (Interviewee G)

The responses given suggest that the issue of children and their well-being is included in a fragmented way in practical theological research and training, which can easily result in the compartmentalisation of children in theological reflection and in the practice of church ministry. The one-sided focus on catechesis, for instance, raises the question of whether the theological perspective of children as developing human beings who require directive education does not weigh heavier than the more positive perspectives of children as models of faith and agents of change in their own right. The fragmented approach to children in practical theological interpretation could be related to the causal factors that were given to describe why children are a marginal theme in practical theology. When the basis of reflection on children and childhood is grounded in a fragmented approach, it makes sense that experts, additional time and curriculum opportunities and even independent organisations are needed to include children in practical theological training. However, this raises the important question of whether it should not be the task and responsibility of every theologian, on the basis of the Christian faith, to include children in particular moments of practical theological interpretation. The following responses argued in support of this point:

'I think that what adults can contribute to the welfare of the child weighs much heavier in theological training that the other way round. I don't think that the contributions of children find its rightful place in our curriculum.' (Interviewee J)

'My experience is that adults view the Bible and theology through adult eyes. It requires from someone to help you to understand to take notice of children and young people. Otherwise you only think about adults. And that poverty lies deep.' (Interviewee K)

'When we talk about human rights for some reason it is about adults' rights. So this would be actually important not only to bring religion on board on the issues of children's rights but also to help to criticise religion on its own failures.' (Interviewee B)

Theme 4: Listening is a new challenge for practical theology

In the light of the first three themes identified above, the act of listening to children as active agents and participants could indeed be identified as a new challenge for practical theological interpretation in the South African context. The following responses provide an idea of the complexities that need to be dealt with in setting an action agenda for listening to children:

'I think that it is something we count on, that children are an important aspect of research. To give the children a voice is going to take a while - the knowledge that they have a voice and the ability to have a close relationship with God.' (Interviewee A)

'I literally think that children are neglected. People talk about them and not to them. It is seriously important to talk directly to children.' (Interviewee D)

'This is the image that people have of children; that they cannot think for themselves on their level and in their peer group. This is an interesting question that you ask and compels us to reorientate ourselves.' (Interviewee D)

'I think this is quite sad about practical theology ... that students who undertake research often talk to the ministers or adults. I think there are also not so many people doing research together with children.' (Interviewee J)

It can be concluded that the results of the qualitative phase of the research as a whole reflect a strong perception amongst members of the SPTSA that a deficient understanding of children and childhood prevails within this academic circle and its related church constituencies. The results strongly suggest that the current practical theological focus on children is not adequately supported and motivated by a theological framework that integrates the various domains and publics of practical theology. This deficiency, the results further highlighted, could be attributed in an important way to two factors: a limited focus on children in practical theological research and a fragmented and periodical inclusion of the issue of children in the practical theological curriculum. The contribution of practical theology to the enhancement of the well-being of children is consequently seriously compromised by this deficiency.

Furthermore, the value of the mixed-method research design utilised in this research could well be noted at this point of the discussion. In the quantitative phase, based on Osmer's description of the four tasks of practical theological interpretation, it was found that the participants to a large degree agreed that practical theology does have a contribution to make to the promotion of children's well-being and rights. In addition to this, their responses also suggest a strong commitment to, and appreciation of a normative theological basis that should guide the academy of practical theology in addressing the issue of children's welfare. However, the results from the qualitative phase revealed the opposite perspective, namely that the actual practice of practical theological interpretation in South Africa does not reflect the same commitment to and appreciation of such a normative basis as expressed in theory. As a direct consequence, this finding therefore suggests that the promotion of a 'hermeneutics of listening' should be regarded as an urgent agenda item for practical theology in South Africa.

Conclusion

This article started by identifying a definite and visible movement towards a 'hermeneutics of listening' to children in the international fields of theology and religious studies, in which the contribution of practical theologians is increasingly recognisable. From the vantage point of this conceptual position the discussion indicated how this movement is also embryonically evident in the scholarly context of Africa, albeit with distinctive shortcomings. It was pointed out how in the African scholarly debate the focus still primarily falls on the 'well-becoming of children' vis-a-vis their 'well-being', as well as on the adversity that children experience in everyday life instead of on their abilities and agency roles.

Yet, in furthering its African focus, this article also included a specific South African application by discussing the results from a recent empirical investigation amongst members of the Society for Practical Theology in South Africa, which consisted of a quantitative and qualitative research phase. On the basis of the comparative perspective that emerged from the results of the respective quantitative and qualitative phases of the research, the discussion could ultimately point out that there is a distinctive gap between the normative commitment to children amongst members of the academy and what is realised in this regard in the actual practice of practical theological interpretation.

As a result, it can be concluded that one deeper implication of the identified gap is that the 'hermeneutics of listening' is substantially underdeveloped in the SPTSA at this point. Another is that the public of the church and the related focus on faith development within this public is prioritised at the cost of the public of the broader society. This narrow-minded focus, it can be further concluded, indeed limits the influence of the Christian faith to a minority of children of the South African population - id est only to those who are part of the life of the church (cf. Heitink 1999:87). By implication this, in an important way, prevents practical theology from engaging in a larger social involvement with children and from mediating a Christian presence within the larger living context of children in modern society (cf. Swart & Yates 2006:336; Heitink 1999:294). This effectively leads practical theologians to abandon the public cause of children to be dealt with by others (cf. Heitink 1999:298).

Having addressed a specific South African but also African concern, it can be argued that this article provides important evidence of the extent to which the actual practising of a 'hermeneutics of listening' with regard to children still remains an important challenge for practical theological scholarship in this context. Whilst the task of conceptualising this challenge should not mean that the larger international context and what is academically produced in this context is taken uncritically as the norm, the conceptual progress that has been made in this context on the new hermeneutics - of which this article has given some evidence - nevertheless presents an important starting point for undertaking this task.

Acknowledgements

This article was initially prepared for presentation at the Second Joint Conference of Academic Societies in the Field of Religion and Theology, Pietermaritzburg, South Africa, 18-22 June 2012. The material is based upon work that was supported by the National Research Foundation of South Africa under Grant Number TTK2006042500020.

Any opinions, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and therefore the NRF does not accept any liability in regard thereto.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no financial or personal relationship(s) which may have inappropriately influenced them in writing this article.

Authors' contributions

I.S. and H.Y. were both responsible for planning and conceptualising the structure, title and thematic focus of the article. H.Y. conducted the original empirical work reflected in the article. I.S. and H.Y. contributed equally to the actual writing of the article. I.S. was responsible for the preparation for submission and revision of the article.

References

Ansell, N., 2005, Children, youth and development, Routledge, New York. [ Links ]

Bansikiza, C., 2004, 'Child labour challenges to society and church in Africa', African Ecclesial Review 46(2), 139-160. [ Links ]

Bray, R., 2011, 'Effective child participation in social dialogue', in L. Jamieson, R. Bray, A. Viviers, L. Lake, S. Pendlebury & C. Smith (eds.), South African Child Gauge 2010/2011, pp. 30-35, Children's Institute, University of Cape Town, Cape Town. [ Links ]

Bray, R. & Dawes, A., 2007, 'Monitoring the well-being of children: Historical and conceptual foundations', in A. Dawes, R. Bray & A. Van der Merwe (eds.), Monitoring child well-being: A South African rights-based approach, pp. 5-28, Human Science Research Council, Cape Town. [ Links ]

Bunge, M.J., 2006, 'The child, religion, and the academy: Developing robust theological and religious understandings of children and childhood', Journal of Religion 86(4), 549-579. [ Links ]

Bunge, M.J., 2007, 'Beyond children as agents and victims', in T. Wyller & U.S. Nayar (eds.), The given child: The religions' contribution to children's citizenship, pp. 27-50, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen. [ Links ]

Child Rights International Network, n.d., 'Africa: African Christian scholars and the plight of the African child', viewed 05 June 2012, from http://www.crin.org/ resources/infoDetail.asp?ID=26158 [ Links ]

Creswell, J.W., 2009, Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches, Sage, London. [ Links ]

Daystar University, School of Humanities & Social Sciences, n.d., 'Second call for papers. Academic Forum for African Christian Scholars and Researchers: African Christian scholars and the plight of the African child', 09-11 November 2011, Nairobi, Kenya, viewed 05 June 2012, from http://www.daystar-cdi.com/downloads/Child%20Development%20Symposium.pdf [ Links ]

De Boeck, P. & Honwana, A., 2005, 'Introduction: Children & youth in Africa: Agency, identity & place', in A. Honwana & P. De Boeck (eds.), Makers & breakers: Children & youth inpostcolonialAfrica, pp. 1-18, James Currey/Africa World Press, Oxford/ Dakar. [ Links ]

De Winter, M., 1997, Children as fellow citizens: Participation and commitment, Radcliff Medical Press, Oxford. [ Links ]

Dillen, A., 2006, 'Children between liberation and care: Ethical perspectives on the rights of children and parent-child relationships', International Journal of Children's Spirituality 11(2), 237-250. [ Links ]

Dillen, A., 2007, 'Religious participation of children as active subjects: Toward a hermeneutical-communicative model of religious education in families with young children', International Journal of Children's Spirituality 12(1), 37-49. [ Links ]

Dillen, A. & Pollefeyt, D., 2010, 'Introduction: Children's studies and theology: An hermeneutics of complexity', in A. Dillen & D. Pollefeyt (eds.), Children's voices: Children's perspectives in ethics, theology and religious education, pp. 1-16, Peeters, Leuven. [ Links ]

Diouf, M., 2005, 'Afterword', in A. Honwana & P. De Boeck (eds.), Makers & breakers: Children & youth in postcolonial Africa, pp. 229-234, James Currey/Africa World Press, Oxford/Dakar. [ Links ]

Dube, M.W., 2002, 'Fighting with God: Children and HIV/Aids in Botswana', Journal of Theology for Southern Africa 114(November), 31-42. [ Links ]

Haddad, B., 2002, 'Gender violence and HIV/Aids: A deadly silence in the church', Journal of Theology for Southern Africa 114(November), 93-106. [ Links ]

Heitink, G., 1999, Practical theology: History, theory, action domains, Eerdmans, Grand Rapids, MI. [ Links ]

Hull, J. M., 2007, 'The child as gift', in T. Wyller & U.S. Nayar (eds.), The given child: The religions' contribution to children's citizenship, pp. 185-192, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen. [ Links ]

Kanyoro, M., 2002, 'Holistic ways to empower Africa's children and young people', Journal of Theology for Southern Africa 114(November), 69-78. [ Links ]

Kirby, P. & Woodhead, M., 2003, 'Children's participation in society', in H. Montgomery, R. Burr & M. Woodhead (eds.), Changing childhoods: Local and global, pp. 233284, The Open University/Wiley, Chichester. [ Links ]

Malherbe, J., 2011, Saved by the lion? Stories of African children encountering outsiders, Childnet, Mogale City. [ Links ]

Maluleke, T.S. & Nadar, S., 2002, 'Guest editorial', Journal of Theology for Southern Africa 114(November), 3-4. [ Links ]

Meintjes, H., 2011, 'Children's challenges to adult perceptions and practices', in L. Jamieson, R. Bray, A. Viviers, L. Lake, S. Pendlebury & C. Smith (eds.), South African child gauge 2010/2011, pp. 65-69, Children's Institute, University of Cape Town, Cape Town. [ Links ]

Miller-McLemore, B.J., 2003, Let the children come: Reimagining childhood from a Christian perspective, Jossey-Bass, San Francisco, CA. [ Links ]

Mokwena, S., 2001, 'Deepening democracy: Meeting the challenge of youth citizenship,' in J. Foster & K. Naidoo (eds.), Young people at the centre, pp. 15-30, Commonwealth Secretariat, London. [ Links ]

Montgomery, H., 2003, 'Intervening in children's lives', in H. Montgomery, R. Burr & M. Woodhead (eds.), Changing childhoods: Local and global, pp. 187-232, The Open University/Wiley, Chichester. [ Links ]

Nayar, U.S., 2007, 'Construction of childhood, interactions and inclusions: Growing up in a family with Hindu values orientation', in T. Wyller & U.S. Nayar (eds.), The given child: The religions' contribution to children's citizenship, pp. 71-81, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen. [ Links ]

Nkurunziza, D.R.K., 2004, 'African theology of childhood in relation to child labour', African Ecclesial Review 46(2), 121-138. [ Links ]

O'Neill, T., 2000, 'What is childhood?' in T. O'Neill & T. Willoughby (eds.), Introduction to child and youth studies, pp. 3-9, Kendall/Hunt, Dubuque. [ Links ]

Osmer, R.R., 2008, Practical theology: An introduction, Eerdmans, Grand Rapids, MI. [ Links ]

Pieterse, H.J.C., 1999, 'A theological theory of communicative actions', in F. Schweitzer & J.A. Van der Ven (eds.), Practical theology - international perspectives, pp. 411426, Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main. [ Links ]

Qakisa, M., 2002, 'Let's talk about sex: Reaching young people through the media in the age of aids', Journal of Theology for Southern Africa 114(November), 79-92. [ Links ]

Reynolds, P., 2005, 'Conceptions of pain & children's expressions of it in Southern Africa', in A. Honwana & P. De Boeck (eds.), Makers & breakers: Children & youth in postcolonial Africa, pp. 81-101, James Currey/Africa World Press, Oxford/Dakar. [ Links ]

Richter, A. & Muller, J., 2005, 'The forgotten children of Africa: Voicing HIV and Aids orphans' stories of bereavement: A narrative approach', HTS Theological Studies 61(3), 999-1015. [ Links ]

Roche, J., 2004, 'Children's rights, participation and citizenship', in M.D.A. Freeman (ed.), Children's rights, vol. 1, pp. 475-493, Ashgate, Aldershot. [ Links ]

Swart, I. & Yates, H., 2006, 'The rights of children: A new agenda for practical theology in South Africa', Religion & Theology 13(3/4), 314-340. [ Links ]

Teipen, A.H., 2007, 'Submission and dissent: Some observations on children's rights within the Islamic edifice', in T. Wyller & U.S. Nayar (eds.), The given child: The religions' contribution to children's citizenship, pp. 51-70, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen. [ Links ]

United Nations Children's (Emergency) Fund (UNICEF), 2005, The state of the world's children 2006, viewed 21 May 2012, from http://www.unicef.org/sowc06/pdfs/sowc06_fullreport.pdf [ Links ]

Van Oudenhoven, N. & Wazir, R., 2006, Newly emerging needs of children: An exploration, Garant, Antwerp. [ Links ]

Wall, J., 2006, 'Childhood studies, hermeneutics and theologcial ethics', Journal of Religion 86(4), 523-548. [ Links ]

Wall, J., 2010, 'Childism and the ethics of responsibility', in A. Dillen & D. Pollefeyt (eds.), Children's voices: Children's perspectives in ethics, theology and religious education, pp. 237-266, Peeters, Leuven. [ Links ]

Wyller, T. & Nayar, U.S., 2007, 'The other child as gift? A historical challenge for religions in late modernity', in T. Wyller & U.S. Nayar (eds.), The given child: The religions' contribution to children's citizenship, pp. 7-14, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen. [ Links ]

Wyse, D. (ed.), 2004, Childhood studies: An introduction, Blackwell, Victoria. [ Links ]

Yates, H., 2010, 'Childhood and child welfare in a social development context: An exploratory perspective on the contribution of the religious sector', in I. Swart, H. Rocher, S. Green, J. Erasmus (eds.), Religion and social development in postapartheid South Africa: Perspectives for critical engagement, pp. 153-174, SUN Press, Stellenbosch. [ Links ]

Correspondence to:

Correspondence to:

Ignatius Swart

PO Box 329, Unisa 0003,

South Africa

swarti1@unisa.ac.za

Received: 27 July 2012

Accepted: 29 Aug. 2012

Published: 08 Nov. 2012

© 2012. The Authors. Licensee: AOSIS OpenJournals. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution License.

Note: This article is published in the section Practical Theology of the Society for Practical Theology in South Africa.