Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

HTS Theological Studies

On-line version ISSN 2072-8050

Print version ISSN 0259-9422

Herv. teol. stud. vol.68 n.1 Pretoria Jan. 2012

DEDICATION

Abraham (Abe) Johannes Malherbe (1930-2012) teoloog en mens / theologian and human

Jan G. van der WattI, II

IDepartment of New Testament Exegesis and Source Texts of Christianity, Radboud Universiteit Nijmegen, the Netherlands

IIResearch Unit for Theology and Religion, University of South Africa, South Africa

Abraham Johannes Malherbe, of Abe soos hy alombekend was, is op 15 Mei 1930 in Capitol Park, Pretoria, gebore. Hy kon altyd met opgewondenheid vertel hoe hy en sy maats in die Magaliesbergkoppies, waar die Pretoriase dieretuin vandag is,1 gespeel het. So tussen die klippe en bossies van Pretoria het sy liefde vir Suid-Afrika gegroei - iets wat hy tot aan die einde van sy lewe met hom saamgedra het. Dit was 'n liefde wat, na my mening, sterker geword het soos die jare aangestap het.

Sy kinderjare in Suid-Afrika was vormende jare in sy lewe. Hy het graag vertel hoe hy in die oorlogsjare (die Tweede Wêreldoorlog) as twaalfjarige seun by sy familie op hulle plaas in die destydse 'Oos-Transvaal' gaan kuier het. Toe hy eenmaal moes teruggaan Pretoria toe, word hy gevra om drie gevangenes (Italiaanse soldate wat op die plaas gewerk het) terug te vat konsentrasiekamp toe. As twaalfjarige is hy toe saam met die krygsgevangenes op die trein terug en het hy hulle veilig by die kamp gaan besorg - natuurlik tot die verbasing van die bevelvoerder. Hierdie verhaal verbeeld in 'n sekere sin hoe hy homself gesien het. Iemand wat nie terugdeins vir uitdagings nie. Iemand wat met getrouheid en vasberadenheid dinge enduit kan voer en wat die vertroue werd is wat mense bereid is om in hulle te stel. Iemand wat graag ander wil help. So was hy ook. Mense wat hom geken het, sou hierdie kwaliteite in hom kon vind - nie net in sy akademiese werk nie, maar ook in sy persoonlike verhoudings.

Nadat hy sy skoolloopbaan by Afrikaans Hoër Seunskool in Pretoria voltooi het, het hy by landmeters gaan werk en daarna by die Elektrisiteitsvoorsieningskommissie van Suid-Afrika. In hierdie tyd het sy pad met 'n sendeling, Eldred Echols, gekruis en het hy homself aan die Here toevertrou - die Here wat hy getrou sou bly dien tot aan die einde van sy lewe. Hy het gevolglik besluit dat hy teologie wil gaan studeer en Echols het hom aangeraai om VSA toe te gaan. Die rede waarom hy nie sommer in Suid-Afrika studeer het nie, was eenvoudig: Churches of Christ, die kerkgenootskap waaraan hy behoort het, het nie 'n opleidingsplek in Suid-Afrika gehad nie - daarvoor moes hy na Abilene Christian University in Texas gaan.2 Die rede waarom hy nie teruggekom het nie, was nog eenvoudiger: hy het Phyllis Melton daar ontmoet. Hy is in 1953 met haar getroud en hulle sou sielsgenote bly tot sy dood.3

As 21-jarige is hy VSA toe en het hy daar sy eerste graad in Grieks (en Handelinge, soos hy spottenderwys sou sê) voltooi aan die Abilene Christian University, opleidingsentrum van die Churches of Christ. Daarna het hy sy studies aan Harvard in Boston gaan voortsit. Hy ontvang in 1957 die STB-graad. Sy talent is raakgesien en hy kon vir sy doktorsgraad (ThD) by die destyds bekende prof. Arthur Darby Nock inskryf. Hy het dit in 1963 onder prof. Helmut Koester voltooi, aangesien prof. Nock intussen oorlede is. Nock was die groot akademiese invloed in sy lewe. As hy oor sy akademiese lewe gepraat het, is die naam van Nock met reëlmaat genoem. Nock het daarin geslaag om in Abe 'n liefde vir die teks, asook 'n deeglikheid en strewe na uitnemendheid aan te wakker - dit sou later van sy groot akademiese kenmerke word.

Abe het in hierdie tyd ook nie net by sy boeke gesit nie. Sy belangstelling was wyer, veral met betrekking tot die uitbou van sy vak. Dit sou in die latere jare een van sy belangrikste eienskappe blyk te wees - sy betrokkenheid by die uitbou van sy vak. Dit het vir hom 'n belegging in studente en boeke beteken. In 1957, tydens sy studie by Harvard, was Abe byvoorbeeld die medestigter (saam met Pat Harrell) van die Restoration Quarterly wat binne die Churches of Christ, en selfs wyer, 'n invloedryke akademiese rol sou speel. In hierdie tyd is hy ook aangewys as die Harvard Divinity School Commencement Greek Orator.

Gedurende die periode waarin hy aan sy doktorsgraad gewerk het, het iets anders ook gebeur wat sy verhouding met wat hy noem 'the NT fraternity in South Africa'4 radikaal beïnvloed het. Hy is in 1960-1961 na Utrecht (Nederland) om daar onder leiding van die bekende prof. W.C. van Unnik te gaan werk - meestal aan die projek Corpus Hellenisticum. In hierdie tydperk het hy ook verder as Nederland gereis - hy het vir twee weke lank navorsing gaan doen in die Universiteitsbiblioteek van Uppsala (Swede). Daar was 'n databasis van die bekende antieke skrywer Dio Chrisostomus waarin hy besondere belangstelling gehad het.

Aan die begin van hul verblyf in Utrecht in 1960 het Abe en Phyllis se paaie met Jannie5 en Rina Louw gekruis wat op daardie stadium ook in Nederland vir verdere studie was. Abe vertel dat die Louws nie lekker verblyf gehad het nie en natuurlik het Abe en Phyllis dinge laat gebeur. In sy eie woorde: 'The poor Afrikaners were starving with no meat. Naturally, my Texas Boerevrou stepped into the breach, had them over for some beef, and arranged for them to rent rooms in the same house that we were renting. We became good friends.'6 Hulle het mekaar nie voor die tyd geken nie, alhoewel Abe en Rina drie blokke van mekaar af in Capitol Park grootgeword het en in dieselfde laerskool, Jacques Pienaar Laerskool, was. Dit het Nederland gekos om hul paaie te laat kruis. Hierdie openheid en hulpvaardigheid was tipies van die Malherbes oor al die jare. As hulle 'n Suid-Afrikaner raakloop en hulle kan help, dan doen hulle dit. Dit was die eerstehandse ervaring van menige Suid-Afrikaner wat by Yale gaan navorsing doen het, of wat vir hom vir kommentaar op hul werk gevra het, of wat hom sommer net vir raad gevra het. Waarskynlik een van die kenmerkendste eienskappe van Abe (en Phyllis) was hierdie openheid, hulpvaardigheid en gasvryheid.

Na die Utrecht-tydperk is Abe terug Harvard toe en het sy akademiese kontak met Suid-Afrika in 'n periode van 'tien jaar stilte' ingegaan. In dié 10 jaar het dinge egter wonderbaarlik vir Abe in die VSA begin ontwikkel. Nadat hy sy doktorsgraad aan Harvard voltooi het, word hy in dieselfde jaar (1963) as mede-professor in Nuwe Testament en vroeë Christendom by Abilene Christian University aangestel om die Nuwe Testament, asook die Griekse filosofiese en religieuse agtergrond van die Nuwe Testament te doseer. Dit het presies in die kraal van Abe gepas en hy was een van die eerstes van sy geslag om die sosiale dinamiek van die Grieks-Romeinse antieke tekste vir die Nuwe-Testamentiese navorsing te ontsluit. Belangstelling in die sosiale raamwerk van die Nuwe Testament, wat in die laaste deel van die vorige eeu sterk na vore begin tree het en nog steeds prominent in die vakgebied figureer, het in 'n groot mate sy oorsprong in die studeerkamer van Abe in Abilene gevind. Hy het aan my vertel hoe hy gedissiplineerd elke aand verskeie bladsye uit die antieke Griekse dokumente gelees het. So het hy 'n kennis van die antieke sosiale wêreld en die gepaardgaande bronne ontwikkel wat in sy tyd ongeëwenaard onder Nuwe-Testamentici was. Daarom kon hy so 'n leidende rol in die ontwikkeling van die sosiale verstaan van Nuwe-Testamentiese tekste speel.

By Abilene het hy veral hard gewerk aan die vestiging van 'n etos van hoë akademiese standaarde, wat later heelwat vrugte vir die instelling opgelewer het. Daar het uiteindelik 10 uitstaande akademici uit die geledere van die Churches of Christ (onder wie John Fitzgerald, Carl Holladay en Michael White) onder hom by Yale gepromoveer en toe Yale onlangs 'n posisie moes vul, was drie uit die ses gekortlyste kandidate van Abe se studente. Hy het altyd na hulle met trots verwys as sy 'seuns'. Dit is sprekend van die invloed wat Abe (en mense soos Everett Ferguson) op die akademiese standaarde binne dié kringe gehad het.

Abe het tot 1969 aan die Abilene Christian University gedoseer en hy het dit goed gedoen. In 1967 word hy by Abilene vereer met die Trustee's Outstanding Teacher of the Year toekenning. Hy het egter ook sy vleuels wyer gespan. In hierdie tyd was hy 'n besoekende dosent aan Harvard Universiteit (1967-1968) en begin hy die reeks Living Word Commentary Series as eerste redakteur. In 1969 verlaat hy Abilene en skuif Dartmouth toe waar hy die aandag van die invloedryke Nils Dahl van Yale trek. Sy boek The structure of Athenagoras (North Holland Publishing Co.) verskyn ook in daardie jaar. Die gevolg is dat hy in 1970 by Yale as dosent aangestel word. Sedert 1981 beklee hy die gesogte Buckingham professoraat aan die Yale School of Divinity, 'n posisie wat hy beklee het tot en met sy aftrede in 1994.7

Om terug te keer tot sy Suid-Afrikaanse bande. In hierdie periode (vanaf Utrecht tot hy by Yale aangestel is) het hulle kontak met die Louws, en so ook in 'n sekere sin direkte akademiese kontak met Suid-Afrika, verloor. Dit was eers toe Jannie Louw in die vroeë 1970's 'n artikel oor Abe gelees het wat die kontak weer hervat is. Jannie Louw het 'n konsultant by die United Bible Society geword en dus gereeld na die VSA gereis vir vergaderings. Hulle het mekaar toe weer gereeld begin sien. Phyllis en Rina 'were like sisters, both gentle and quiet women with similar values', terwyl Abe en Jannie akademise belange gedeel het. Abe het in hierdie tyd net indirekte professionele kontak met Suid-Afrikaners gehad wat meestal deur Jannie gefasiliteer is. Hy het wel Suid-Afrikaners sosiaal ontmoet by vakkongresse soos die Society of Biblical Literature (SBL) en die Society New Testament Studies (SNTS), maar verder as dit het dit nie gegaan nie. Uit gesprekke het ek baie goeie rede om te vermoed dat Abe tog gevoel het dat hy op daardie stadium nie as Suid-Afrikaner gesien of waardeer is nie. Abe beskryf die situasie in hierdie tyd so: 'Some South Africans did find their way to Yale, because I was here, and we entertained them ... A stream of people from RSA came to New Haven. Apparently it was thought okay for them to be received at Yale, but I was not invited to speak at a South African university. I assumed that it was because of my "sectarian" affiliation.'

Dit was apartheidsjare en dinge was nie altyd maklik nie - nie vir die Suid-Afrikaners nie, en om 'n baie spesifieke rede ook nie vir Abe nie. Hy het byvoorbeeld besluit om sy Suid-Afrikaanse paspoort in daardie tyd te hou, alhoewel hy 'n Amerikaanse paspoort kon kry. Die vlaktes van die 'Oos-Transvaal' en die Magaliesbergkoppies was te diep in sy bloed. Dit het hom baie moeite met visums en sulke dinge gekos, maar uit lojaliteit teenoor sy land wou hy 'n Suid-Afrikaner bly en dit so wys.8

In die laat 1980's het die situasie rondom Abe se betrokkenheid in Suid-Afrika 'n positiewe wending geneem: Jannie Louw, toe professor in Grieks aan die Universiteit van Pretoria, nooi Abe Suid-Afrika toe as gasdosent. Nou moet hier net eers genoem word dat in die tyd wat verloop het sedert Jannie Louw die artikel van Abe in die 1970's gelees het tot hy Abe in 1989 na Suid-Afrika genooi het, het Abe se loopbaan van krag tot krag gegaan en het hy met sy boeke en publikasies een van die internasionale Nuwe-Testamentici geword wat wêreldleiding op die gebied van die sosiale lees van antieke tekste geneem het. As pionier van hierdie benadering het hy sy eie siening en benadering gehad. In sy jare by Yale het hy saam met Leander Keck en Wayne Meeks die Nuwe-Testamentiese wetenskap by Yale wêreldbekend gemaak en het hy uitstekende PhD kandidate getrek wat vandag op verskillende gebiede in hul eie reg internasionaal bekend geword het.

Binne die sosiale paradigma het daar verskillende benaderings begin ontwikkel. Meeks, wat nie skroom om die invloed van Abe op sy wetenskaplike ontwikkeling te erken nie, het byvoorbeeld sosiaal-histories begin werk. Dan was daar weer die Context Group waarmee Abe probleme gehad het, omdat hulle aanvanklik meer met modelle gewerk het as met die antieke tekstuele gegewens self. Hy het van sosiale modelle of strukture waarmee die teks ontsluit word, weggedeins. Hy het die teks voorop gestel en sy siening van eksegese eendag so vir my opgesom: eksegese is om alle verstaansmoontlikhede vir 'n betrokke teksgedeelte te ondersoek en die motivering vir die besondere manier van verstaan te evalueer en dan gemotiveerd jou eie siening te formuleer. Vir hom was die tekste van die Nuwe Testament sosiaal van aard en daarom het hy beklemtoon dat vergelykbare sosiale inligting uit daardie spesifieke tyd nodig is vir die verstaan van die tekste. Daarom het hy die massa antieke sosiale materiaal ontsluit - nie met die idee om iets in die Griekse materiaal te kry en dit dan op die Nuwe Testament toe te pas asof die Nuwe Testamentiese skrywers dit van daar oorgeneem het nie. Met ander woorde, hy het nie die materiaal hanteer asof daar direkte lineêre beïnvloeding vanaf die Griekse materiaal na die Nuwe-Testamentiese teks was nie. Hiermee het hy teen 'n sterk stroom van daardie tyd ingegaan - geleerdes soos Dodd, Kittel en selfs Bultmann het wel 'n meer direkte verband tussen die sogenaamde agtergrondsmateriaal en die teks van die Nuwe Testament getrek. Abe het geargumenteer dat die leser deur 'n diep kennis van die sosiale dinamiek van die Griekse wêreld gesensiteer word om 'n soortgelyke sosiale dinamiek in die Nuwe-Testamentiese teks te kan raaksien. Sonder om direkte onwikkelingslyne te poneer, help die Griekse sosiale inligting die Nuwe-Testamentikus om dus sosiale uitsprake te maak wat geldigheid het binne die antieke sosiale konteks en dus nie vanuit moderne sienings aangebied word nie. So word daar tot 'n meer outentieke verstaan gekom.

Sy benadering het wel tot diskussie, en selfs teenstand, gelei. In 1983 het Bruce Malina ('The received view and what it cannot do: 3 John and hospitality', Semeia, 1986, pp. 171-194) van die Context Group op 'n artikel van Abe oor 3 Johannes ('The inhospitality of Diotrephes' in God's Christ and his people, University Press, Oslo, 1977, pp. 222-232) gereageer. Abe het daarin die sosiale dinamiek van die konflik binne die Johannes-groep beskryf. Malina argumenteer dat Abe net beskryf en dat hy nie interpreteer nie, met ander woorde dat hy nie verklaar waarom dinge in 3 Johannes was soos wat dit was nie. Dit het Abe nie oortuig nie. Die interessante deel is dat hierdie artikel van Abe 'n sentrale invloed in die verstaan van 3 Johannes gespeel het. Selfs die invloedryke Raymond Brown het Abe se teorie, natuurlik met klein aanpassings, in sy kommentaar oor die Johannes-briewe oorgeneem.

Gesien die belangstelling van Abe en sy besondere breë kennis van die Hellenistiese sosiale wêreld (wat uit sy lees van sy Loeb-tekste gegroei het) was dit dus te wagte dat daar heelwat publikasies op hierdie terrein uit sy pen sou verskyn. Miskien moet by sy artikel in ANRW 'Hellenistic moralists and the New Testament' begin word, wat baie wyd gesiteer is en eintlik die agenda gestel het vir die hantering van die verhouding tussen die Hellenistiese materiaal en die Nuwe-Testamentiese navorsing. In 1977 verskyn The Cynic epistles: A study edition (University of Michigan, Michigan - later deur Scholars Press, Atlanta) en Social aspects of early Christianity (Louisiana State University Press, Louisiana - met die tweede uitgebreide uitgawe deur Wipf and Stock in 2003). In 1984 publiseer hy The world of the New Testament (Abilene Christian University) en in 1986 Moral exhortation: A Graeco-Roman sourcebook (The Westminster Press, Philadelphia). Sy belangstelling in die korrespondensie van Paulus aan die Tessalonisense lei tot die 1987-publikasie van Paul and the Thessalonians: The philosophical tradition of pastoral care (laaste herdruk in 2011 deur Mosaic Press). Ancient epistolary theorists (Scholars Press, Atlanta) verskyn in 1988 en in 1989, die jaar waarin hy Suid-Afrika vir die eerste maal as 'n internasionaal bekende akademikus besoek het, verskyn Paul and the popular philosophers (Fortress, Minneapolis) wat ook daarna herdruk is. Daarmee saam het daar 'n groot aantal artikels die lig gesien wat nie hier genoem kan word nie. Binnekort verskyn 'n versamelband van sy artikels deur Brill - dit beslaan twee volumes (sy oud-studente werk al vir twee jaar aan die publikasie9).

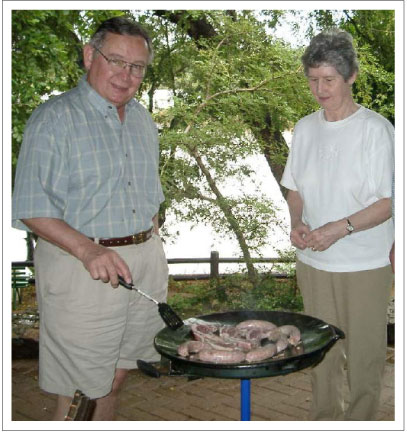

So arriveer die seun van Pretoria in 1989 in Suid-Afrika met 'n akademiese rekord wat vir 'n Suid-Afrikaner ongeëwenaard op internasionale akademiese gebied was. In Augustus 1989 swaai die Suid-Afrikaaanse deure vir hom oop en lewer hy in 28 dae lesings by 14 verskillende akademiese instellings. Skielik kon hy eerstehands die akademiese wêreld van sy geboorteland betree en ook sien wat hier gebeur het. In daardie tyd was die Nuwe-Testamentiese wetenskap in Suid-Afrika op sy eie manier toonaangewend op die vlak van die literêre benadering van die Nuwe Testament. Dit was natuurlik nie 'n terrein waarin Abe soveel belang gestel het as in die sosiale en historiese raamwerk van die Nuwe Testament nie. Hoewel van die jonger akademici tog hul weg na Yale gevind het, het Abe se benadering in hierdie tyd nie so 'n groot impak in Suid-Afrika gemaak as wat 'n mens sou verwag nie. Verskillende redes kan daarvoor gegee word - onder andere die dominante belangstelling in die literêre benaderings wat in daardie tyd in Suid-Afrika hoogty gevier het. Hierna sou hy meer gereeld na Suid-Afrika reis om sy kennis te kom deel, veral as gas van die Departement Nuwe Testament van die Universiteit van Pretoria. My PhD-studente en selfs meer junior studente het met sy besoeke gereeld in gemaklike omstandighede vir die akademiese gesprekke bymekaar gekom, soos byvoorbeeld by Dikhololo ('n vakansieoord in die Bosveld waar Abe op sy beste was). Daar het hy deur die dag akademiese kennis deurgegee en in die aande, om die braaivleisvuur onder die sterre, het hy ons almal met sy wysheid en breë ervaring van die lewe getrakteer. Dit het vir hom groot plesier verskaf, want hy kon jongmense sien groei en bloei. 'n Jaar voor sy dood het hy die buitengewone ding gedoen om 'n uitnodiging na Suid-Afrika toe aan te neem sonder dat Phyllis saamgekom het. Wie Abe goed geken het, sou geweet het dat dit totaal buitengewoon was. Hy en Phyllis het oral saam gereis, maar die lang reise het vir haar te vermoeiend begin word en sy het besluit om tuis te bly. Hy het net voor die reis vir my gesê dat hy dit eintlik nie moet doen nie, maar dat hy dit alleenlik vir een rede doen: hy doen dit vir die jonger akademici in Suid-Afrika.10 As hy iets kan bydra, sal hy dit doen - al is dit vir hom ongerieflik. Ek het toe onwillekeuring teruggedink aan die twaalfjarige seuntjie wat uit eie erkenning maar skrikkerig was om die krygsgevangenes met die trein na die konsentrasiekamp toe terug te neem, maar verby homself gekyk het om ander te help. Dit was wie Abe was en gebly het.

Hierdie openheid waarmee hy in die Suid-Afrikaanse akademiese wêreld ontvang is, het Abe so laat reageer: 'I had been accepted....' Op voorstel van my en gesteun deur die Fakulteit Teologie, het die Universiteit van Pretoria op 08 September 2000 aan Abe 'n eredoktorsgraad toegeken. By hierdie geleentheid het die Universiteit ook aan hom die eer gegee om namens al die eredoktorande 'n dankwoord te spreek. In sy brief noem hy dat hierdie toekenning vir hom 'n hoogtepunt van die erkenning en bewys van sy aanvaarding was. 'I have felt that I was personally accepted, and marvel at the warmth of the Boeremense who were once standoffish, but like Apollos, had learned the way of the Lord more perfectly' (die laaste frase natuurlik met 'n bietjie tong-in-die-kies-humor waarvoor Abe so goed bekend was).

Om terug te keer na Abe se werk in die VSA. Hy het in 1994 by Yale geëmeriteer, waar hy ook 'n besondere rol gespeel het. Hy het leidende posisies ingeneem wat hy terdeë geniet het, byvoorbeeld as adjunk-dekaan vir die studente. Waar ek hom die mees entoesiasties gesien het, was wanneer hy vertel het van sy interaksie met die studente en veral as hy hulle kon help. Dit het hom baie vervulling gegee. Hy was ook nou betrokke by die ontwikkeling van biblioteke11 (een van sy liefdes) - by Yale, asook by Abilene.12

Na sy aftrede het hy doodluiters aanhou werk. Hy het immers juis vroeër afgetree om meer tyd aan sy navorsing te kan spandeer. Hy het op die eerste verdieping van sy huis in Hamden 'n groot vertrek gehad wat hy as sy studeerkamer ingerig het. As 'n mens in die gang afstap, het jy eerste in sy groot versameling Loeb-bundels van die antieke skrywers vasgekyk. Links het sy lessenaar gestaan. Tussen die lessenaar en die muur was sy swaaistoel. Sy rekenaar het hy teen die muur op 'n tafel gehad en as hy omdraai, kon hy op sy lessenaar, wat altyd vol boeke was, werk. Die mure van die hele vertrek was toe met boekrakke vol boeke en teen die teenoorgestelde kant van die kamer het sy gemakstoel gestaan waar hy gesit en lees het. Dit was in hierdie studeerkamer waar Phyllis hom op 28 September 2012 gekry het. Toe sy gaan inkopies doen het, was alles nog normaal, maar toe sy terugkom het sy hom leweloos daar in sy stoel gekry.

Abe het 'n goeie roetine gehad. Hy het min geslaap en tot laat in die nagte gewerk - en sommer soms op sy lekker stoel geslaap. Deel van sy roetine was om koerante te lees. Koerante is elke oggend by sy huis afgelewer en as hy klaar was, is dit na sy buurman toe. Internasionale koerante het hy op die rekenaar gelees. Daarom was dit altyd lekker om by hulle te kuier. Hy het iets van alles geweet, veral ook wat in Suid-Afrika aangegaan het. Die res van die tyd het hy aan sy 'groot projekte' gewerk. Sy standaardwerk op Tessalonisense, The Letters to the Thessalonians (Yale University Press, New Haven), het in 2004 verskyn en met sy dood was hy besig met kommentaar oor die Pastorale briewe in die Hermeneia-reeks. Die kommentaar is natuurlik nie voltooi nie, maar alles is darem nie verlore nie. Abe het aan my gesê dat hy die kommentaar anders aangepak het. Hy wou eers artikels skryf oor die groot en belangrike temas in die Pastorale briewe en van daar af na die volle kommentaar beweeg. Van die artikels het al verskyn en gee ons dus 'n kykie in die manier waarop hierdie merkwaardige teoloog die Pastorale briewe verstaan het.

Ook buite sy studeerkamer het hy aktief gebly. Hy was in aanvraag en het onder andere herhaalde akademiese besoeke as gasdosent by verskillende instansies in die Ooste, Suid-Afrika, Europa en natuurlik die VSA gebring. So het hy byvoorbeeld in 1994 die Abilene Christians Distinguished Alumni citation ontvang en is hy in 2005 uitgenooi om die Carmichael-Walling Lectures by sy alma mater te lewer. Hy is tydens sy eie leeftyd, selfs na sy aftrede, ook op verskeie maniere vereer. Daar is byvoorbeeld verskeie beursskemas wat in sy naam begin is - hy het selfs 'n deel van sy pensioen aan so 'n skema geskenk. Daar is ook twee feesbundels aan hom opgedra: in 1990 (Greeks, Romans, and Christians) en 2003 (Early Christianity and Classical Literature).

Geen beskrywing van Abe is volledig sonder om terug te keer na die begin nie - na sy ontmoeting met Eldred Echols. Vir Abe het sy geloof tot aan die einde sentraal gestaan. Hy het die besondere vermoë gehad om die moontlike spanning tussen sy geloof en sy akademiese aktiwiteite in balans te hou. Hy was sy hele lewe lank intens by kerklike bedrywighede betrokke deur te preek, volwasse onderrig te gee, te help met verversings en om mense tuis te laat voel. Daar waar hy nodig was en iets kon doen, daar was hy. Hy het dit ook nie altyd net maklik gehad nie. In die Churches of Christ was daar maar ook woelinge, soos in elke ander kerkgenootskap, en op 'n stadium is akademici soos Abe en Everett Ferguson as sogenaamde 'moderniste' deur sommiges in die kerk beskryf. Die geskiedenis het uitgewys dat dit maar net die geval was dat Abe voor sy tyd was en beter kon sien waarheen die rivier vloei. Die afgelope tyd het Abe en Phyllis gereeld die dienste van die First Baptist Church (Whitney Avenue in New Haven) bygewoon. Nie een keer wat ons op 'n Sondag by Abe-hulle op besoek was, het ons kerk oorgeslaan nie.

Geskiedenis leef in mense se gedagtes, in hul verhale en in hul herinneringe. Wat was, kan nooit weer wees nie. Al wat is, is wat ons daarvan onthou en wat ons daaroor kan vertel met opregtheid en outentisiteit. Hierdie was my stukkie geskiedenis van een van die merkwaardigste mense wat ek in my lewe leer ken het. 'n Uitsonderlike teoloog, 'n buitengewone mens, 'n lojale vriend en 'n gelowige tot aan die einde. In die geskiedenis van Abe sal hy nooit sy geliefde Suid-Afrika verlaat nie, want hy sal daar bly leef - op die rakke van ons biblioteke en in sy invloed op so baie, maar nog te meer in ons herinneringe.

1. Die dieretuin is eers in 1946 geopen.

2. Sy suster en twee broers woon steeds in Suid-Afrika. Hy het met sy akademiese besoeke in Suid-Afrika altyd 'n punt daarvan gemaak om sy familie te gaan opsoek, al het dit beteken dat hy na die Natalse Suidkus toe moes gaan om by Lettie te gaan kuier.

3. Drie kinders is uit die huwelik gebore: Cornelia, Selina en Jan (sy eerste naam is ook Abraham). Abe en Phyllis het ook drie kleinkinders.

4. Alle aanhalings in Engels kom uit privaat korrespondensie van prof. Malherbe aan my. Hy het na elke besoek aan Suid-Afrika met my gekorrespondeer oor sy belewenisse. Met die dood van prof. Jannie Louw het hy op 02 Januarie 2012 aan my 'n lang brief geskryf oor hoe hy sy verhouding met Suid-Afrika gesien ontwikkel het. Prof. Louw het natuurlik 'n sentrale rol daarin gespeel. Die aanhalings hier kom hoofsaaklik uit hierdie brief.

5. Prof. J.P. Louw was later jare professor in Grieks aan die Universiteite van Bloemfontein en Pretoria. Hy het veral bekend geword vir sy betrokkenheid by die Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament (UBS, New York) waarvan hy een van die opstellers saam met E.A. Nida was. In die genoemde brief aan my skryf Abe so oor Jannie Louw: 'I think it important to remember that there was a time when he and David Bosch were the major South African scholars in our field with international standing... I am grateful for what he accomplished...'

6. Jare later toe Abe en Phyllis in 2010 by ons in Nederland op besoek was, het ons hulle Utrecht toe geneem. Daar moes ons op en af ry tot ons die huis waarin hulle gebly het, gekry het - natuurlik gepaardgaande met veel kommentaar en herinneringe van hulle kant af. Dit het net weer die belang van hierdie periode in sy lewe onderstreep.

7. Hy het enkele jare vroeër afgetree as wat hy moes, maar het dit gedoen om minder administrasie en rompslomp te hê en meer tyd beskikbaar te kry vir die voltooiing van sy Tessalonisense kommentaar.

8. My indruk was dat sy motivering nie polities was nie; daarvoor was hy te lank uit Suid-Afrika weg. Dit was meer 'n kwessie van landsliefde en solidariteit met dit wat deel van jou is. Hy was 'n Suid-Afrikaner, het hy gesê, en hy gaan nie nou skielik nie meer 'n Suid-Afrikaner wees omdat dit vir hom moeiliker raak nie. So het ek Abe ook op ander vlakke leer ken - lojaal en solidêr, kom wat wil.

9. Interessant genoeg wou Abe nooit self by so 'n projek betrokke raak nie omdat hy homself of sy idees nooit aan mense wou opdring nie. Hy het sterk opinies gehad en het dit met oortuiging gestel, maar as jy dit nie wou aanvaar nie, het dit hom nie van koers gebring nie. As jy so wou dink, kon jy maar wat hom betref so dink. Hy was wel ingenome toe sy studente die inisiatief geneem het om sy artikels in 'n bundel te publiseer.

10. Hierdie besoek het gelei tot sy referaat by die Prestige FOCUS Conference on Mission and Ethics van 14 tot 16 September 2011 te Universiteit van Pretoria, Suid-Afrika (georganiseer deur prof. Kobus Kok). Dit is gepubliseer as 'Ethics in Context: The Thessalonians and their neighbours', HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies 68(1), Art. #1214, 10 pages. http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/hts.v68i1.1214

11.'n Insiggewende video in hierdie verband is op YouTube te vinde ('On being a lover of libraries'). Daar verduidelik Abe waarom biblioteke vir hom so belangrik was. Die toespraak is ook om 'n ander rede insiggewend. Dit is 'n tipiese 'Abe Malherbe' toespraak - hy het altyd iewers in sy toespraak op 'n mooi manier na Suid-Afrika verwys.

12. Hy het ook vir my in privaatgesprekke genoem dat hy onder andere genader is om president van die SNTS te word, of dekaan van die School of Divinity by Yale, maar dat hy sulke posisies konstant van die hand gewys het. Hy het gesê dat dit nie was waarvan hy gehou het nie. Dit het iets van sy eerlikheid en integriteit gesê.

Abraham Johannes Malherbe, or Abe as everyone knew him, was born on 15 May 1930 in Capitol Park, Pretoria. He always related with enthusiasm how he and his friends used to play in the Magaliesberg hills where the Pretoria Zoo stands today1. There, amongst the rocks and bushes of Pretoria, he developed his love for South Africa - a love he carried with him to the end of his days. It was a love, which if anything in my view, became stronger over the years.

His childhood years spent in South Africa were formative years in his life. He would readily tell the story of how he as a 12-year-old boy visited relatives on their farm in the then Eastern Transvaal during the war years (World War II). Once, on his way back to Pretoria, he was asked to accompany three Italian prisoners of war, who had been working on the farm, back to the concentration camp. He thus found himself as a 12-year-old boy on a train back to Pretoria with prisoners of war and he made sure they got back to camp safely - obviously to the commander's astonishment. In a way this story depicts how he saw himself - as someone who does not shy away from challenges, someone who will see things through faithfully and with perseverance, someone worthy of the trust people are prepared to put in him and someone keen to help others. This is how he was too. People who got to know him found these qualities in him - not only in his academic work, but also in his personal relations.

After his school career at Afrikaans Boys High in Pretoria, he started to work with land surveyors and then joined the Electricity Supply Commission of South Africa. During that time he crossed paths with a missionary, Eldred Echols, and he dedicated himself to the Lord, whom he would faithfully serve until the end of his life. He decided that he wanted to study theology and Echols advised him to go to the USA. In reply to my question on why he did not study in South Africa, his answer was simply that the denomination he belonged to, the Churches of Christ, did not have a training facility in South Africa - and to receive his training he had to go to the Abilene Christian University in Texas.2 When I asked why he never returned, his answer was even simpler: in the USA he met Phyllis Melton whom he married in 1953. They would remain soul mates until his death.3

As a 21-year-old he was off to the USA, where he obtained his first degree in Greek (and Acts as he would say tongue in the cheek) from the Abilene Christian University, the training centre of the Churches of Christ. He continued his studies at Harvard in Boston where he received the STB degree in 1957. His talent was recognised and he could enroll for his doctorate (ThD) under Prof. Arthur Darby Nock, a well-known professor at the time. He completed his doctorate in 1963 under the supervision of Prof. Helmut Koester as Prof. Nock had passed away. Nock was the great academic influence in Abe's life. Whenever he spoke of his academic life, Nock's name regularly featured. Nock instilled in Abe a love for text, thoroughness and a pursuit of excellence - traits that were to become his great academic characteristics.

Abe did not only spend time in front of his books. He had a wider interest, especially as far as expanding his subject was concerned. In later years it would also emerge as one of his main traits - his involvement in expanding his subject. To him this meant investing in students and in books. In 1957, during his studies at Harvard, Abe was the co-founder (together with Pat Harrell) of the Restoration Quarterly, which would fulfill an influential academic role within the Churches of Christ and beyond. During this time he was also the Harvard Divinity School Commencement Greek Orator.

Whilst working on his doctorate, something else happened which also radically influenced his relationship with what he called the 'the NT fraternity in South Africa'4. He was in Utrecth (the Netherlands) in 1960-1961 to work under the guidance of the famous Prof. W.C. van Unnik, particularly within the Corpus Hellenisticum project. During this time his travels took him further than the Netherlands - he undertook research at the University Library of Uppsala (Sweden) for two weeks. It had a database of the famous ancient author Dio Chrisostomu - a particular interest of Abe's.

At the beginning of their stay in Utrecht in 1960 the paths of Abe and Phyllis crossed those of Jannie5 and Rina Louw who were also in the Netherlands for further studies. Abe mentioned that the Louws' accommodation was not too comfortable and, true to their nature, Abe and Phyllis made things happen. In his own words: 'The poor Afrikaners were starving with no meat. Naturally, my Texas Boerevrou stepped into the breach, had them over for some beef, and arranged for them to rent rooms in the same house that we were renting. We became good friends.'6 They did not know one another before then, although Abe and Rina grew up within three blocks of each other in Capitol Park and they attended the same primary school, Jacques Pienaar Primary School. For their paths to cross, they had to go all the way to the Netherlands. This openness and helpfulness characterised the Malherbes over the years. If they came across a South African and they could be of any help, they would offer it. Many a South African who went to Yale for research, or who asked him to comment on their work, or who simply asked for advice, experienced this kindness first-hand. This openness, helpfulness and hospitality were probably Abe's most typical characteristics (this is also true of Phyllis).

After the Utrecht period Abe returned to Harvard and his academic contact with South Africa entered a 'ten year period of silence'. However, things in the USA developed in a remarkable way for Abe during these 10 years. In the same year as completing his doctorate at Harvard, he was appointed as associate professor in New Testament and early Christianity at the Abilene Christian University to lecture on the New Testament, as well as the Greek philosophical and religious background of the New Testament. This suited Abe down to the ground and he was one of the first of his generation to unlock the social dynamics of the Greco Roman ancient texts for New Testament research. Interest in the New Testament's social framework, which began to emerge strongly during the latter part of the previous century and which still features prominently in this field of study, largely had its origins in Abe's study in Abilene. He told me that he diligently read a few passages from ancient Greek documents every night. In this way he acquired knowledge about the ancient social world and the accompanying resources - a knowledge that was unequalled among New Testament scholars of his time. It was for this very reason that he could play such a leading role in the development of a social understanding of New Testament texts.

Whilst at Abilene he also applied himself to establishing an ethos of high academic standards, which yielded many results for the institution in years to come. Eventually 10 outstanding academics from the ranks of the Churches of Christ (including John Fitzgerald, Carl Holladay and Michael White) undertook their doctor's degrees at Yale under his supervision, and when Yale recently had to fill a position, three out of the six short-listed candidates were students of Abe's. He referred to his students as his 'sons'. This is proof of the influence Abe (and others like Everett Ferguson) had on academic standards within these circles.

Abe lectured at the Abilene Christian University until 1969 and he excelled at it. In 1967 Abilene honored him with the Trustees' Outstanding Teacher of the Year award. However, he spread his wings further. During this time, he was also a visiting lecturer at Harvard University (1967-1968) and he started the Living Word Commentary Series as its first editor. In 1969 he left Abilene and relocated to Dartmouth where he caught the attention of the influential Nils Dahl of Yale. The following year his book, The structure of Athenagoras (North Holland Publishing Co.), was published. As a result, he was appointed as lecturer at Yale in 1970. Since 1981 he held the prestigious Buckingham professorship at the Yale School of Divinity - a position he held until his retirement in 1994.7

Back to his South African ties. Since the time in Utrecht until his appointment at Yale, he lost contact with the Louws and thus in a certain sense also lost direct academic contact with South Africa. It was only when Jannie Louw read an article by Abe sometime during the early seventies that contact was reestablished. Jannie Louw became a consultant for the United Bible Society and often travelled to the USA for meetings. The Louws and Malherbes saw each other regularly again. Phyllis and Rina 'were like sisters, both gentle and quiet women with similar values', whilst Abe and Jannie shared academic interests. Apart from his contact with Jannie, Abe had only indirect professional contact with South Africans during this time - Jannie mostly facilitated such contact. He did meet South Africans socially at conferences such as the Society of Biblical Literature (SBL) and the Society New Testament Studies (SNTS), but the contact did not go beyond social interaction. Based on conversations I had with him, I have good reason to believe that Abe must have felt that he was not regarded nor appreciated as a South African at the time. Abe described the situation at the time as follows: 'Some South Africans did find their way to Yale, because I was here, and we entertained them ... A stream of people from RSA came to New Haven. Apparently it was thought okay for them to be received at Yale, but I was not invited to speak at a South African university. I assumed that it was because of my "sectarian" affiliation.'

Those were the apartheid years and things were not all that easy then - not for South Africans, and for a very specific reason not for Abe. He had, for instance, decided to keep his South African passport during those times, although he was entitled to an American passport. The plains of the 'Eastern Transvaal' and the hills of the Magaliesberg were too ingrained in his being. It meant a great deal of trouble when he had to obtain visas and the like, but because of his loyalty towards his country, he wanted to remain a South African and he wanted to show it.8

During the late eighties the situation around Abe's involvement in South Africa took a positive turn. Jannie Louw, then Professor in Greek at the University of Pretoria, invited Abe to South Africa as guest lecturer. At this juncture it needs to be mentioned that between the time that Jannie Louw read Abe's article in the seventies and his invitation to Abe to visit South Africa in 1989, Abe's career had gone from strength to strength - and thanks to his books and publications, he had become one of the international New Testament scholars who had taken the lead globally as far as the social reading of ancient texts is concerned. As pioneer of this approach he held his own opinion and he had his own approach. During his years at Yale, together with Leander Keck and Wayne Meeks, he made the New Testamentical Science at Yale world-renowned and it attracted brilliant PhD candidates, who are today internationally renowned in their own right.

Various different approaches began to develop within the social paradigm. Meeks, who does not hesitate to recognise Abe's influence on his scientific development, has begun to work in a social historical way. Then there was the Context Group with whom Abe experienced problems because they initially worked with models rather than with the ancient textual information itself. He tended to avoid social models or structures in terms of which the text was unlocked. For him, the text took precedence and he once summarised his view on exegesis to me as follows: exegesis is to investigate all possibilities to understand a particular text, to evaluate the motivation for this particular way of understanding and to then, with motivation, formulate your own view. To him the texts of the New Testament are social in nature and for this reason he emphasised that comparable social information from that specific era was necessary to understand the texts. It is for this reason that he unlocked the mass of ancient social material - not with the idea of finding something in the Greek material to be applied to the New Testament as if the New Testament authors had taken it over from the Greek material. In other words, he did not deal with the material as if there was a direct linear influence from the Greek material on the New Testament text. In maintaining such a view he went against a strong stream at the time - scholars like Dodd, Kittel and even Bultmann established a more direct link between the so-called background material and the text of the New Testament. Abe argued that the reader is sensitised by in-depth knowledge of the social dynamics of the Greek world to be able to recognise a similar social dynamic in the New Testament text. Without positing direct development lines, the Greek social information therefore assists the New Testament scholar to make social statements which have validity within the ancient social context, and which are thus not presented in modern views. In this way, a more authentic understanding can be arrived at.

His approach did indeed lead to discussion - and even opposition. In 1983 Bruce Malina of the Context Group reacted to an article by Abe on 3 John (the article is entitled 'The inhospitality of Diotrephes' in God's Christ and his people, University Press, Oslo, 1977, pp. 222-232; Malina's article is entitled 'The received view and what it cannot do: 3 John and hospitality', Semeia, 1986, pp. 171-194). In his article Abe described the social dynamics of the conflict within the

Johannine group. Malina argued that Abe merely describes and does not interpret - in other words he does not explain why things in 3 John were as they were. However, it did not convince Abe. Interestingly, this article of Abe's had a central influence on the understanding of 3 John. Even the influential Raymond Brown has included Abe's theory, with minor adjustments, in his commentary on the Johannine letters.

Given Abe's interest in and his exceptionally wide knowledge of the Hellenist social world (as a result of him studying the Loeb texts) it could be expected that many publications would appear on this topic by his pen. Perhaps one should start with his article in ANRW 'Hellenistic moralists and the New Testament', which was widely cited and did indeed set the agenda for the handling of the relationship between the Hellenist material and New Testament research. In 1977, The Cynic epistles: A study edition (University of Michigan, Michigan - later by Scholars Press, Atlanta) appeared, and Social aspects of early Christianity (Louisiana State University Press with the second expanded version at Wipf and Stock) appeared in 2003. In 1984, he published The world of the New Testament (Abilene Christian University), followed by Moral exhortation: A Graeco-Roman sourcebook (The Westminster Press, Philadelphia) in 1986. His interest in Paul's correspondence with the Thessalonians led to the 1987 publication of Paul and the Thessalonians: The philosophical tradition of pastoral care (last reprint in 2011 by Mosaic Press). Ancient epistolary theorists (Scholars Press, Atlanta) appeared in 1988, and in 1989, the year in which he visited South Africa as an internationally renowned scholar, Paul and the popular philosophers (Fortress, Minneapolis) appeared. This work was reprinted at a later stage. Apart from these, many other articles, which cannot be listed here, saw the light. A collection of his articles will soon be published by Brill (Leiden). It comprises two volumes (his former students have been working on this publication for the past two years9).

So it happened that the boy from Pretoria arrived back in South Africa in 1989 with an academic record that, for a South African, was unequalled at international academic level. In August 1989 doors throughout South Africa opened for him and he gave lectures at 14 different academic institutions in 28 days. Suddenly he could experience the academic world in the country of his birth first-hand and he could see what was happening here. At that stage New Testament Science in South Africa was, in its own way, taking the lead as far as the literary approach to the New Testament was concerned. Of course it was not a field that held the same interest for Abe as his interest in the social and historical framework of the New Testament. Although some of the younger academics made their way to Yale, Abe's approach at the time did not make such a big impact as one would have expected. There are several reasons for this, amongst others the interest in literary approaches which dominated in South Africa at the time. After this visit, he was to travel more regularly to

South Africa to share his knowledge, especially as a guest of the Department of New Testament Studies at the University of Pretoria. During his visits, my PhD students and even more junior students often got together for an academic discussion in a relaxed atmosphere, for example at Dikhololo (a holiday resort in the Bushveld where Abe was in his element). There he shared his academic knowledge during the day, whilst in the evenings, under the stars around the fire, we could share in his wisdom and rich experience of life. This gave him so much joy for he could see young people grow and flourish. A year before his death he did the exceptional thing of accepting an invitation to visit South Africa without Phyllis accompanying him. Those who knew Abe well would know that this was completely exceptional. Phyllis had accompanied him on all his travels, but the long journeys became too exhausting for her and she decided to stay at home. Before his journey he told me that he should not be doing it, but that he was attempting it for one reason only: he was doing it for the younger academics in South Africa.10 If he could make a contribution he would, even if it was at his own inconvenience. I could not help but think back to the 12-year-old boy who, by his own admission, was rather nervous to accompany the prisoners of war on the train journey back to camp, but who disregarded himself in order to help others. This is the man Abe was and the man he would always be.

The openness with which Abe was received in the South African academic world, elicited the following reaction from him: 'I had been accepted...' Upon my suggestion and supported by the Faculty of Theology, the University of Pretoria awarded him an honorary doctorate on 08 September 2000. The university also bestowed the honour to ask him to reply on behalf of all the honorary doctorandi by delivering a message of gratitude. In his letter he mentioned that the award was a personal highlight and proof of his acceptance. 'I have felt that I was personally accepted, and marvel at the warmth of the Boeremense who were once standoffish, but like Apollos, had learned the way of the Lord more perfectly' (the last phrase was meant with the tongue firmly in the cheek, the type of humour Abe was renowned for).

Let's return to Abe's work in the USA. He retired in 1994 after a rewarding career at Yale where he had left his mark. He took up leadership positions, for example that of Deputy Dean of Student Affairs - a position he thoroughly enjoyed. The most enthusiastic I saw him was whenever he spoke about his interaction with students, especially when he could be of assistance to them. He found this so fulfilling. He was also involved in the development of libraries11 at Yale, as well as at Abilene12 - one of his passions.

After his retirement he simply continued working. Being able to spend more time on his research was precisely why he had retired. On the first floor of his home in Hamden was a spacious room that he turned into his study. Walking down the passage, the first thing you would notice is the large collection of Loeb volumes containing the works of the ancient authors. His desk was on the left. His swivel chair was between the wall and the desk. His computer was on a table next to the wall and when he turned around, he could work at his desk, which was always laden with books. The walls were lined with bookshelves filled with books, and his easy chair stood on the other side of the room. There he spent time reading. It was here in the study that Phyllis found him on 28 September 2012. When she went shopping, everything was still as usual, but upon her return she found him lifeless in his chair.

Abe maintained a good routine. He did not sleep much and worked until late at night, sometimes falling asleep in his easy chair. Reading newspapers was part of his routine. The papers were delivered to his door every morning and once he finished reading them, they were passed on to the neighbour. He read international papers on the internet. The fact that he was so knowledgeable, especially about all the happenings in South Africa, made it so pleasant to visit him. The rest of his time was dedicated to his 'big projects'. His standard work on Thessalonians, The Letters to the Thessalonians (Yale University Press, New Haven) was published in 2004 and at the time of his death he was working on a commentary on the Pastoral letters in the Hermeneia series. The commentary has not been completed, but all is not lost. Abe told me that he had approached this commentary in a different manner. He first wanted to write articles on the major and important themes in the Pastoral letters, and from there he wanted to move on to the full commentary. Some of these articles have already been published and they give us a glance of how this remarkable theologian understood the Pastoral letters.

His work and involvement stretched beyond the four walls of his study, as he still remained active in academic life. He was very much in demand and he repeatedly paid numerous academic visits as guest lecturer to various institutions in the East, South Africa, Europe and obviously also in the USA. He was honored in many ways during his lifetime, even after retirement. For example, he received the Abilene Christian Distinguished Alumni citation in 1994 and in 2005 he was invited to give the Carmichael-Walling Lectures at his alma mater. Numerous bursary schemes have been founded in his name - he even donated part of his pension to such a scheme. Two Festschrifts have been dedicated to him: Greeks, Romans, and Christians in 1990 and Early Christianity and Classical Literature in 2003.

No description of Abe is complete without returning to where it all started - his encounter with Eldred Echols. For Abe his faith remained central in his life, right to the end. He had the ability to balance the possible tension between his faith and his academic activity. His whole life he was intensely involved in church activities - whether it was in the form of preaching, adult training, by helping out with catering or by making people feel at home. There where he was needed and where he could make a contribution is where he could be found. He did not always have it easy either. The Churches of Christ, as is the case with any other denomination, also had their fair share of turbulence and at one stage some members of the church described academics like Abe and Everett Ferguson as so-called 'modernists'. Needless to say, history proved that it was merely a matter of Abe being ahead of his time and that he could clearly see in which direction the river was flowing. Of late, Abe and Phyllis regularly attended the services of the First Baptist Church (Whitney Avenue in New Haven). Not once did we miss going to church on a Sunday when we were staying over at Abe and Phyllis's.

History lives in people's thoughts, in their stories and in their memories. What has been can never be again. All that remains is what we can recall of it and can relate in sincerity and authenticity. This is my bit of history of one of the most remarkable persons I have met and got to know during my lifetime. He was an exceptional theologian, an exceptional human being, a loyal friend and a believer right to the end. In Abe's history he would never leave his beloved South Africa, because there he would live on - on the shelves in our libraries and in his influence on so many, but even more so in our memory.

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Jan van der Watt

Email: janvanderwatt@kpnmail.nl

Postal address: Paterserf 7, 6584GA Molenhoek, the Netherlands

© 2012. The Authors. Licensee: AOSIS OpenJournals. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution License.

Note: Jan van der Watt is Professor in Source Texts of Christianity at the Radboud Universiteit Nijmegen and Professor Extraordinary at the Research Institute for Theology and Religion, University of South Africa.

1.The Zoo was only established in 1946.

2.His sister and two brothers still live in South Africa and whenever he came to South Africa on academic business, he always made a point of seeing his family - even if it meant travelling to the KwaZulu-Natal South Coast to visit Lettie.

3.Three children were born of the marriage: Cornelia, Selina and Jan (his first name is also Abraham). Abe and Phyllis have three grandchildren.

4.All English citations are from private correspondence which Prof. Malherbe addressed to me. After every visit to South Africa, he used to write to me about his experiences. Following the death of Prof. Jannie Louw on 02 January 2012, he wrote me a long letter on how he saw his relationship with South Africa, in which Prof. Louw played a central role, develop. The citations used here are mainly taken from this letter.

5.Later on Prof. J.P. Louw was to become Professor in Greek at the Universities of Bloemfontein and Pretoria. He became known in particular for his involvement in the Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament (UBS, New York) of which he was one of the compilors (together with E.A. Nida). In the said letter to me, Abe writes about Jannie Louw as follows: 'I think it important to remember that there was a time when he and David Bosch were the major South African scholars in our field with international standing ... I am grateful for what he accomplished.'

6.Years later when Abe and Phyllis visited us in the Netherlands in 2010, we took them to Utrecht. There we had to drive up and down until we managed to find the place where they had lived, and naturally with finding the place came many memories and remarks. It yet again emphasised the importance of this period in his life.

7.He retired a few years earlier than required, but he did so to be rid of administrative duties and red tape in order to have more time for the completion of his Thessalonians commentary.

8.My impression was that his motivation was not political - he had been out of the country for too long for that to be the case. It was rather a matter of a deep love for one's country and a sense of solidarity with that which is part of one. He was a South African, he said, and he was not going to cease being a South African simply because things were becoming more difficult for him. This is how I came to know Abe at other levels too - loyal and in camaraderie above all, come what may.

9.Interestingly, Abe was not keen to become involved in such a project because he never wanted to impose himself or his ideas on people. He had strong opinions, which he shared with conviction, but if you did not want go along with it, it did not distract him. As far as he was concerned, you could think what you wanted to think. He was pleased though when his students took the initiative to publish his articles in a collection.

10.This resulted in a paper presented at the Prestige FOCUS Conference on Mission and Ethics from 14 to 16 September 2011 at the University of Pretoria in South Africa (organised by Prof. Kobus Kok), published as 'Ethics in Context: The Thessalonians and their neighbours', HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies 68(1), Art. #1214, 10 pages. http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/hts.v68i1.1214

11.An insightful video in this regard can be found on YouTube (it is entitled On being a lover of libraries). In it Abe explains why libraries were so important to him. The speech is quite revealing for another reason too. It is a typical Abe Malherbe speech - whenever the opportunity arose, he referred to South Africa in his speeches.

12.He also mentioned in private conversations with me that he had been approached to become the president of the SNTS or dean of the School of Divinity at Yale, but he constantly declined such positions. He said that such positions were not to his liking - an indication of his honesty and integrity.