Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

HTS Theological Studies

On-line version ISSN 2072-8050

Print version ISSN 0259-9422

Herv. teol. stud. vol.67 n.3 Pretoria Jan. 2011

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Pentecostalism and schisms in the Reformed Church in Zambia (1996-2001): Listening to the people

Lukas SokoI; H. Jurgens HendriksII

IReformed Church in Zambia, RCZ Kalulushi Congregation, Kalulushi, Zambia

IIFaculty of Theology, University of Stellenbosch, South Africa

ABSTRACT

This article is descriptive in nature and a practical theological assessment of the schisms that took place in the Reformed Church in Zambia (RCZ) between 1996 and 2001. It analyses empirical evidence to find an answer to the question why it happened. Pentecostal or charismatic tendencies have challenged the long inherited tradition of mainline churches. Subsequently, Pentecostal or charismatic movements have caused intense conflict in the church between the pro-conservatives and pro-Pentecostals. In the RCZ this led to the formation of the Christian Reformed Church (CRC) in 1999 and the Bible Gospel Church in Africa (BIGOCA) in 2001.

Introduction

This article provides a descriptive and practical-theological assessment of the Reformed Church in Zambia (RCZ) schisms, relevant to the understanding of one of the most salient contemporary issues in the church in Africa, the growth of Pentecostalism (Cox 1995:243-262; Martin 2002; Kalu 2008). This kind of schism either takes place within congregations or between large bodies of Christians that all impact on the church's mission. The institutional model of being a church is facing immense pressure to change. The larger research project (Soko 2010) aims at alerting church leaderships to realise the importance of change and transition and to eventually ask the question of how to prevent schisms. This article is, however, specifically aimed at listening to the people. The eventual question of how these schisms can be prevented can only be truthfully answered if there is clarity of what happened on the ground and how the people involved experienced it. The validity and reliability of the research finding thus compelled us to explain in some detail the methodology that we followed.

The research problem

The RCZ experienced two schisms that followed each other within a period of five years. The first started in 1996 and continued to 1999, when a minister was expelled and a number of members followed him. They formed their own church called the Christian Reformed Church (CRC). The first split started as a small constitutional matter. The presbytery leadership accused the Mtendere congregation of insubordination when they rejected the minister whom the Synod had sent to them. The presbytery insisted that the Synod's authority was final and nonreversible (Soko 2010:105-120).

In 2001, nine ministers in nine RCZ congregations were expelled, together with those members who supported their new worship practices. They formed the Bible Gospel Church in Africa (BIGOCA). The second schism started as a violation of the Church's tradition on worship. In urban areas, many congregations started new ways of worship. Individual ministers in various congregations started (what was perceived as) a violation of the established liturgical order that was gradually being abandoned. It was replaced with altar calls, singing of choruses and the clapping of hands, dancing, skipping of the Lord's Prayer, repeated shouting of 'hallelujah' and 'amen', mass prayers, and speaking in tongues. Thus, the constitution of the Church was refuted (Soko 2010:81-104).

Up to the end of the research project (2010), the Church has not yet attended to the root causes of the problem. What caused the schisms and how can it be prevented?

Sociological dimension

The RCZ is one of the oldest pioneer churches in Zambia. In 1899, the Dutch Reformed Church (DRC) missionaries founded it in the Eastern part of Zambia (Verstraelen-Gilhuis 1982). From a small missionary endeavour, the RCZ has grown with its membership cutting across cultural barriers. The RCZ has its administrative headquarters in Lusaka, the capital city of Zambia. The motivation to do this research emerged from the researchers' direct involvement, one as a serving minister at the time of the split, the other through NetACT1.

Research methodology

This article describes the practical theological part of the research (Soko 2010) that endeavoured to develop instruments to discover how the faith community felt about what was happening in the Church. Secondly, it is also concerned about data-gathering methods. It aims to establish the link between the primary documental sources (Soko 2010:80-120) and the affected parties' real narratives and stories (described at a later stage). It focuses on specific questions in order to understand how particular members and groups in congregations feel about the RCZ's entire situation of infighting. What, in their opinion, were the causes of the conflict and groups involved? This we saw as a first essential step in the eventual answering of the question of how to handle and prevent such schisms.

Questionnaires, focus groups, sampling and a pilot study played an important role in the empirical part of the research.

The questionnaire

In research methodology, a questionnaire is a document containing questions and other items designed to solicit information from the target group (sample) for appropriate analysis (Cooper & Schindler 2008:710; De Vos 1998:152; Rubin & Babbie 2007:111; Sapsford 2007:109; Sapsford & Jupp 1996:94). In this study as an instrument of data collection, it aims at soliciting information from people represented in the sample, in terms of opinions, beliefs or judgements which will be useful for analysis. For purposes of this research, the use of open-ended questions will be more appropriate in order to allow respondents the freedom to narrate their own experiences of the schisms that took place in the RCZ.

A focus group

The focus group is a method for data collection in the practice of research that is focused upon, and uses, group discussions to generate data (Barbour & Kritzinger 1999:4; Blanche & Durrheim 2002:388; Cooper & Schindler 2008:149, 179; De Vos 1998:315; Hesse-Biber & Leavy 2006:197; Morgan 1998:29). It can also be defined as a captive group, or number of individuals between whom a distinguishable pattern of interaction exists. As a method of data collection, the focus group varies, based on the sampling and the research question being studied.

Sampling

As a research method, sampling can be described as a process of selecting elements from the target population with representativeness being the means to assist a researcher to explain some of the population's experiences (De Vos 1998:191; Mouton 1996:132). Representativeness in sampling is primarily important for the selection of elements that are considered to have an equal chance of being selected with most of the population's characteristics relevant to the research in question. How representative the sample can be is a question that hinges on two kinds of sampling, namely probability and nonprobability sampling (De Vos 1998:193; Mouton 1996:139). Probability sampling is a methodology of selecting the sample aimed at giving each member of the target group an equal chance of being selected. Babbie (2007:184), Davies (2007:56) and Mouton (1996:132) argue that probability sampling is a type of sampling in which the units to be observed are selected on the basis of the researcher's judgement about which will be most useful or representative. This was the method used in this research.

A pilot study

A pilot study can be described as a process that aims at improving the validity of the study. It is a feasibility study that, firstly, is aimed at specific pretesting of a particular research instrument for data collection on a justified small scale of the sample. In other words, it is a trial run in preparation for the full-scale study (De Vos 1998:179; Sapsford & Jupp 1996:103; Social Research Update 35). In a number of ways, a pilot study assesses the feasibility of a study before the major study is actually carried out. On the part of respondents, a pilot study sets an entry phase to make them aware of the intended study. This entry is crucial in helping the researcher to understand the local culture or problems that may affect the research process. In this research, the pilot study was deemed important because the nature of the study continues to create tension within the RCZ. It indeed led us to adapt our research strategy.

The context of the research

A description of the context, the presbyteries and congregations in Lusaka follows. The sample frame of congregations was drawn from the RCZ, BIGOCA and CRC.

The Reformed Church in Zambia

In total, the Reformed Church in Zambia (RCZ) has 16 presbyteries. Three of these presbyteries are in Lusaka, namely Chelstone, Kamwala and Matero. Congregations from these presbyteries were selected for pretesting the questionnaire and focus group interviews used to solicit members' opinions, beliefs, or judgements on what they perceived and experienced as the causes of the splits.

In these three presbyteries, all the congregations were affected, but six of them were at the centre of the conflict. These six congregations, that is, Mtendere, Chawama Central, Garden, Chaisa, Chelstone and Matero, were selected as a representative sample for pretesting the questionnaire and focus group interviews.

A brief background of events in the six congregations

In the Mtendere congregation (Chelstone Presbytery), conflicts amongst the members started when Synod allotted a new pastor to them in 1996. The elders wanted to exercise l.See http://academic.sun.ac.za/theology/netact.html their constitutional right of calling a pastor of their own choice. This demand resulted in a standoff between the Chelstone Presbytery's leadership and the Mtendere congregation's Church council. These misunderstandings between the elders and the Presbytery spilt over into a conflict between the Synod leaders and the new minister and, consequently, led to the first break-away group, the CRC.

At the Chawama Central congregation (Kamwala Presbytery), police closed the Church for at least eight months from September 2000 to April 2001, caused by conflicts about Pentecostal tendencies. All Church activities were prohibited. Thus, members of this congregation had to find an alternative venue for worship.

The 'Pentecostals' took over the Chaisa (Matero Presbytery) congregation's church building when differences about worship intensified. The noncharismatic members felt uncomfortable, could not withstand the pressure, and thus chose to find an alternative venue for worship.

At the Garden congregation (Chelstone Presbytery), members attacked each other during Sunday worship services. Many elders were suspended. The RCZ's logo on the church building was scraped off and it was declared a Pentecostal Church.

The Matero congregation (Matero Presbytery) was affected in several ways. The incumbent moderator was at the centre of the controversy about Pentecostal practices. He was also the resident minister of this congregation. His direct support of Pentecostal and charismatic practices caused this congregation to experience deep divisions.

At the Chelstone congregation (Chelstone Presbytery), the elders' council forced the minister to resign shortly after the 2001 Extraordinary Synod Meeting. Two factors necessitated this development: on one hand, those who were expelled perceived the minister to be a sell-out whilst, on the other hand, members of his congregation labelled him as more Pentecostal, and wondered why he was not also expelled. Worse still was his presence at the launch of the BIGOCA on 06 March 2001.

The Bible Gospel Church in Africa

The final 2001 split led to the formation of the Bible Gospel Church in Africa (BIGOCA). They organised their congregations in terms of what today are called 'assemblies'. The choice of selecting the three assemblies, Matero, Chawama and Garden, for the pilot study was based on the understanding that, in their initial stages of establishment, these assemblies had attracted a good number of members from the RCZ.

The Christian Reformed Church

In 1999, the Christian Reformed Church (CRC) was the first to break away from the RCZ, but little is known about them in terms of their number of congregations or assemblies in Zambia. No other minister, apart from Reverend Amos Ngoma, was heard to have joined it. As such, only the congregation, where he is the resident minister and bishop was chosen.

Along with the selected focus groups in the congregations and assemblies, the sample was also extended to the ministers in all three Churches (RCZ, BIGOCA and CRC) in Lusaka.

Pilot study and adjustment

The pilot study was carried out in order to detect weaknesses in the design and application of the research instruments. This was a phase of testing and adaptation in order to minimise problems during the final investigations. The pilot study was carried out in the six representative sample congregations of the RCZ in Lusaka; two in the BIGOCA (Chawama and Garden) and in the CRC congregation.

A questionnaire with thirteen questions was distributed as follows: all the congregations or assemblies in the representative sample received three open-ended, self-administered questionnaires. It was intended for the nine ministers (six ministers in the RCZ, three BIGOCA and one CRC). Almost all the respondents understood the questions. It was also clear that the clergy had no problems with the questions and in filling in the questionnaires.

However, many respondents found it difficult to write answers in the space available on the questionnaires. They viewed the research topic with reservations. The events that caused the schisms were still traumatising most members. They did not want to discuss the questionnaires again in a focus group. The pilot study revealed the need for adjustment of the empirical research method. We discussed the situation with their pastors in order to find alternatives.

Adjustments

Arising from this reaction experienced during the pilot study, an adjusted empirical research plan became necessary. The question was how to adjust it. In the end it was remarkable how easy consensus was reached. The three fellowships (discussed at a later stage), typical in all the congregations, were more than willing to come together as a fellowship, take the questionnaire, and in focus group style answer each of the questions. In most cases the clergy's argument in favour of this method was that it is part of the local African culture to work in the setup of a group towards reaching consensus.

The RCZ sample was adjusted to 26 out of 34 Lusaka-based RCZ congregations. Eight were omitted because two congregations were established after the schism and the other are in the peri-urban part of Lusaka, not in Lusaka itself. The approach was adjusted to the distribution of four questionnaires per congregation. One was for the minister. The remaining three were for the focus groups of men, women and the youth. Individual questionnaires were also distributed to retired ministers in Lusaka who were knowledgeable of the events during the period, 1996 to 2001. The same procedure was followed in the BIGOCA and CRC.

The focus groups

The organisation of focus groups is critical to determine the reliability of the data gathered. These groups have been distinct even before the splits. These groups function and are organised in the BIGOCA and CRC in more or less the same way as with the RCZ: they too meet regularly on days agreed upon and function with a leadership that is answerable to the board or executive council of their respective denominations.

The Men's Fellowship

A committee organises the Men's Fellowship, whose supervision falls under the Church Council. From time to time, the programme of the activities of the Fellowship is formulated in consultation with, and agreed to by, the Church Council. Membership is drawn from all males who are not under discipline. However, the meetings of the Fellowship are open to all who are interested.

The Women's Fellowship

Unlike the Men's Fellowship, the Women's Fellowship's objective is to bring together the RCZ's women to do God's work amongst the women of the whole world. The pastor's wife is the chairperson of the Fellowship. Membership is open to all women of the RCZ. As with the Men's Fellowship, the Women's Fellowship also falls under the supervision of the Church Council. This fellowship plays a crucial role in all congregations.

The Youth Fellowship

The Youth Fellowship draws its membership from all communicants' youth and catechumen. The Fellowship is under the supervision of the Church Council. The popular saying is 'Ali pansi pa ulamuliro wa Akulu ampingo' [The congregation's elders must approve the Youth's programmes and activities]. However, the elders' authority has allegedly frequently been abused. They meet regularly on Sunday afternoons.

In summary, the three fellowship groups are constitutionally established. They are organised and are accountable to the Church Council of their respective congregations. They organise their meetings more or less independently. Through their various executives, and within their fellowships, they have the constitutional mandate to suspend a member and submit his or her name to the Church Council for a final decision.

Data and analysis

In this study, data analysis can be defined as a research tool used in the process of gathering, editing and reducing accumulated data (information collected from the participants) to a manageable size. The accumulated data should serve the research goals and help with decision making (Cooper & Schindler 2008:702; Qualitative Data Analysis n.d.). With this in mind, the data was gathered in the four categories2 mentioned earlier.

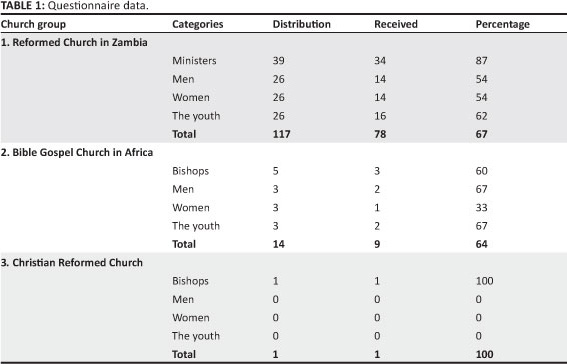

Although the overall response rate was high (Table 1), some problems were encountered, particularly with the CRC, whose focus groups (men, women and the youth) categorically refused to participate in this study. They viewed the research as a way of bringing long-forgotten differences to memory with bitterness. This section focuses on content analysis, discussion and descriptive summaries of the responses of various focus groups in the RCZ, BIGOCA and CRC.

A simple format of content analysis and coding was done (Soko 2010:139-160). The article now summarises the results using the questions as subheadings.

Question 1a

Between 1996 and 1999, the RCZ Mtendere congregation experienced severe conflict. What, in your view, caused this conflict?

One should keep in mind that the BIGOCA and CRC bishops were former RCZ members. The RCZ's men's, women's and youth focus groups, who answered the questions in this section, are those who did not join the break-away Churches. They may be from the 'Dutch/Missionary' or conservative group, or they may still have strong sympathies with those who seceded. Most in the BIGOCA groups were members of the RCZ before they broke away from the RCZ. This will be realised from their answers.

The content analysis of Q1a from the ministers and bishops and focus groups confirm the key issues that led to the schism of the CRC:

- inadequate leadership to handle the conflict

- worship issues related to Pentecostalism cults (typical of Pentecostal or charismatic personalities seen on television and evangelism campaigns at large)

- Reverend Amos Ngoma's personality.

Question 1b

Who in your view were the main groups in this conflict?

All responses in all the categories mentioned earlier reveal that, in this conflict, the main groups were the leadership of the RCZ at various levels. The frequency and repeated mentioning of pastors, elders, the presbytery, the synodical committee, women's, men's and youth fellowships are all recognised groups in the RCZ.

Question 2

What, in your opinion, caused the RCZ's failure to bring about reconciliation at the Mtendere congregation?

This question was asked primarily to balance questions Q1a-b and to test the evidence of the conclusion of Q1a-b. The summary of the content of the responses by the ministers can be coded as follows: (1) Leadership 22, (2) Personalities 8, and (3) Pentecostalism 7.

In terms of the focus groups, the summary of the content of these responses can thus be coded as follows: (1) Leadership 26, (2) Personalities 10, and (3) Pentecostalism 12.

Question 3a

From 1996 to 2001, certain congregations experienced serious conflicts that were labelled, 'charismatic tendencies in worship'. What were the elements of these charismatic worship tendencies?

Interestingly enough, almost all the individual ministers and bishops and focus groups mentioned mass prayer as the major indication of elements of Pentecostalism in the RCZ. Of 82 responses, 56 mentioned mass prayer.

What will enhance an understanding of the worship service context is that, in the process of mass praying, all the other elements manifested: speaking in tongues and crying, clapping of hands whilst praying, walking whilst praying, the hitting of walls, shouting of halleluiah, whistle blowing, and worshipping choruses - all of which were described as noise-making and a disorderly worship style that contradicts the traditional liturgy. These responses of the ministers and bishops and all the focus groups, reveal the tension that the Pentecostal and charismatic-oriented Christianity caused.

Question 3b

From 1996 to 2001, certain congregations experienced serious conflicts that were labelled, 'charismatic tendencies in worship'. What, in your view, were the arguments of those against the charismatic tendencies, and in favour of the RCZ's standard liturgies?

This question is a direct response to Q3a. If these charismatic elements (3a) had found their way into the Church, what arguments were used against them? In analysing the answers to Q3b, typical issues in the conflict that ensued in the RCZ become clear. The content analysis of all the responses, both from the ministers and bishops and all the focus groups who answered this question reveal one basic argument against the charismatic tendencies: that the standard liturgy was good and must be kept intact.

Question 4a

From 1996 to 2001 certain congregations experienced serious conflicts that were labelled 'charismatic tendencies in worship'. There were a number of groups with very strong views for, and against, the new tendencies in the congregations. How will you describe the groups?

Having established the arguments for, and against, the charismatic worship tendencies in Q3b, continued analysis was necessary on how groups started to differ in their interpretation of these tendencies.

Despite a wild profusion of descriptions and statements of the RCZ and the BIGOCA ministers and bishops, as well as the men's, women's and youth focus groups, a constant trend is clear. There are two groups: pro-conservatism and pro-Pentecostalism. The one group wanted to maintain the status quo with fear of losing its 'Reformed identity'. The other group was tired from, or bored by the continued 'Dutch/missionary liturgy' that vowed to bring about change. The distinction between 'Dutch or Pente' started to divide the Church.

Question 4b

From 1996 to 2001 certain congregations experienced serious conflicts that were labelled 'charismatic tendencies in worship'. There were a number of groups with very strong views for, and against, the new tendencies in the congregations. What were the views of each of these groups?

As said in Q4a, the views of the opposing groups clearly emerged from the data. In reading through the answers to Q4b, it is evident that the trend that was picked up in Q4a was repeated here. Coding the views of each group found that the key words frequently mentioned were: traditional, nontraditional, liberalism, pagans, change, reformers, nonreformers, radicals, dialogue and liturgy. There is no sense in quantifying these codes because, once a view has been manifested, subsequent references to it simply prove the point that such a view existed.

However, the perceptions and language used to describe the views of each of the groups generated extremely different positions: the pro-conservative group, embedded in the RCZ's traditions, reflected with extreme rigidity to change and was not ready to hear and analyse the voice of the so-called 'charismatic tendencies'. Simultaneously, the pro-Pentecostal group was extremely aggressive and disrespectful towards the traditional liturgy. This group took an 'evangelist' approach by means of open-air crusades and revival meetings to reach out to members, considered all the RCZ liturgy outdated, and stated that the RCZ liturgy needed a complete change. They were prepared to 'die' for their convictions!

Question 4c

From 1996 to 2001 certain congregations experienced serious conflicts that were labelled 'charismatic tendencies in worship'. There were a number of groups with very strong views for, and against, the new tendencies in the congregations.

What is your view of the role that serving RCZ ministers played during the period of conflict that was positive towards transforming the liturgy?

This question wanted to get more information about the role that those serving ministers played who were positive towards transforming the traditional liturgy.

The main arguments against those who were positive towards transforming the liturgy are:

- they were not conducive to accommodation, were unbalanced, uncompromising, instigating, created chaos and incited members to revolt

- they did not follow the correct procedures

- they were 'too fast' (i.e. too much zeal)

- and showed too little respect for the Synod or the RCZ

- they did not deal theologically with the challenge

- there was no thorough study of the issues

- they did not teach or inform members about these issues

- they had other motives, such as material wealth, and simply wanted to 'do their own thing'.

Answers from the three BIGOCA bishops as regards the ministers, who were positive towards transforming the liturgy, were overwhelmingly positive - as can be expected. They all were pro-Pente before and after the schism. Their arguments were:

- they did so under the guidance of the Holy Spirit, in obedience to the Scriptures

- they were open to much needed transformation in a new time and context.

The CRC bishop's verdict of the serving RCZ ministers' role during the time of the conflict was very negative.

Question 4d

What is your view on the role of serving RCZ ministers that were positive towards the traditional liturgy during the period of conflict?

Question 4d requires views about the role of serving RCZ ministers who were positive towards the traditional liturgy during the period of the conflict. One should keep in mind that most of the ministers or bishops and focus groups who answered these questions were directly, or indirectly, involved in the conflict.

Reading between the lines, a sense of regret is evident that the RCZ's actions were the result of its failure to manage change and transition.

A summary of the answers to this question reveals that most RCZ ministers were not open to transformation and influenced the expulsion of their fellow ministers. In the eyes of 9 of the 14 RCZ men's focus groups, this stance was viewed as the best way to protect the RCZ's identity. Answers from the BIGOCA bishops, the CRC bishop, and the BIGOCA focus groups reveal that the ministers, who were positive towards the traditional liturgy, failed to read the realities of the time and tried to protect the traditions. They became hostile to those who were not in favour of the traditional liturgy and treated their fellow ministers with no love and no respect.

Question 4e

Looking back on the conflict, was it good that RCZ ministers were expelled? Motivate your view.

This question forced the responders to take a stance and motivate it. It testifies to the worst conflict ever experienced in the RCZ. Naturally, the expulsion of nine ministers was a very emotional event that affected everyone in the Church.

The majority believed that it was a mistake. As an examination of the motivation provides for both points of view, one realises how difficult the situation was. In retrospect, one feels that the March 2001 Synod had no option but stop the conflict, as it was ripping the Church apart and also was humiliating. On the other hand, one feels that it could have been prevented if leadership dealt with the conflict earlier.

Their motivation included the following arguments:

- there was too much emotion

- the Synod should have waited for feelings to calm down.

The 2008 Synod did allow mass prayers, which indicates that the 2001 decision was reactionary. Apart from emotion, personal vendettas played a role, and conflicting groups or parties were formed. Dialogue, listening to one another, and trying to embrace each other should have played a role. Reformers should reform!

Question 4f

In your view, how did the presbyteries concerned deal with the conflict?

Question 4g

How, in your view, did the Synod deal with the conflict?

From the answers, each of the claims and statements made against presbytery and Synod leadership point to one fact, that is, the RCZ leadership's failure to provide an environment conducive to dialogue. Phrases and words, such as 'did not show flexibility', 'lamentably or utterly failed', 'compromised and biased', 'mishandling', 'no', 'without critical analysis', 'less theological or pastorally but powerfully', 'emotionally', 'hate', 'interested in expelling', 'more vindictive', 'more judgemental', 'myopically', 'irrationally', et cetera, all describe how people experienced the way in which both the presbytery and Synod leadership dealt with the conflict. The answers said that the RCZ leadership failed to handle the conflict constructively.

Question 4h

In your view, has the issue of 'charismatic tendencies in worship' been solved in the RCZ?

Almost eight years after the RCZ took the landmark decision to expel nine ministers because of charismatic tendencies in the worship; this question seeks to determine whether the RCZ has solved this problem.

Of the 86 answers received to this question, 60 responses contended that the issue of charismatic tendencies in the RCZ's worship was not yet solved. These answers provide a true picture of the differences in the RCZ's worship. It continues to pose a threat for yet another schism, unless the Church leadership addresses the issue. The RCZ acknowledges the problem and wants to find ways to find a workable solution

Conclusion

The research question that guided the research was: what caused the schisms and how can it be prevented? The goal of this article was to present the views of the ministers in Lusaka as well as those of the major groups in the congregations that were involved in the conflict and schisms. Responses to all the questions confirm that the conflict was mainly caused by leadership inadequacies. Ministers and/or bishops and focus groups acknowledged the infighting and failure of the Church leadership to address the conflict successfully. This led to the expulsion of ministers, which resulted in the two break-away Churches.

By using self-administered questionnaires and focus groups, the researchers wished to ensure that the answers obtained from the documentary sources (Soko 2010:81-120) were reliable. Triangulation3 was obtained.

The analysis revealed how the RCZ was embroiled in the conflict concerning Pentecostal or charismatic tendencies. The responses confirmed the correlation that there was indeed a problem of infighting that a number of factors had caused: inadequate leadership to handle the conflict; worship issues related to Pentecostalism and personalities involved personal interest, corruption, selfishness, arrogance and lack of vigour to work towards finding compromises.

The respondents' answers revealed that the RCZ had sided with the more conservative stance. Despite the varying descriptive statements of the ministers or bishops, men, women and the youth, the RCZ was highly divided on the understanding of Pentecostal or charismatic tendencies. Two groups with different interpretations emerged: conservatives and pro-Pentecostals, or, in the local terminology, 'Dutch' and 'Pente'.

Without any bias, the respondents showed that both the presbytery and Synod leadership failed the Church by not providing an environment conducive to dialogue. The responses have shown that even the excommunication of ministers was done in bad faith.

The source of the conflict was the charismatic tendencies that impacted on the traditions and practices of worship in the RCZ. From nearly all responses, mass praying ranked top of the list. During mass praying, the other elements caused conflict to take place: speaking in tongues and crying, clapping of hands whilst praying, rolling on the floor, whistling, worshipping choruses described as noise making, and a disorderly worship style in contradiction to the traditional liturgy.

The article's aim was to get clarity on the base line facts. What happened? How did the people experience it? What was their assessment of the schisms? This information provides the most basic factual data necessary for the eventual practical theological assessment that needs to be undertaken. In retrospect, the schism's bigger picture is clear. The answer to the question 'What led to the schisms and how did it happen?' can only be fully answered when the RCZ's history and identity is understood, as well as the global contextual changes that have taken place and literally transformed Zambian society and culture. Pentecostalism was born at the beginning of the 20th century in circumstances not much different from what is experienced in Zambia and in many countries around the world. Its style, music and ethos address the realities of our times (Cox 1995; Kalu 2008). The RCZ leadership is modelled on the missionaries' and local political leadership and ethos of the independence and post-independence periods. It was divided according to the lines of conflict that ran through the Church, that is, Dutch and Pente. In a sense, the schisms were unavoidable; they played out like a tragic drama (Soko 2010:81-120). How to prevent such schisms and how to handle the tension of transition is a big challenge that needs to be addressed.

A few general remarks:

- There is still substantial support for the ministers who were excommunicated, as well as for their viewpoints, amongst their fellow RCZ ministers and in the congregational groups, notably amongst the youth. The 2008 Synod allowed the bone of contention, mass praying, to have a place in the liturgy (Soko 2010:160).

- There is no way to escape the conclusion that it was the inability and divisiveness of the leadership, at presbytery and Synod level, that could not prevent the schisms from happening.

- In interpreting the data, a saturation point was usually experienced when approximately 50% of a category had been completed. This indicates that the primary information needed to answer the research question(s) was available in the data and was well substantiated.

Acknowledgements

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no financial or personal relationship(s) which may have inappropriately influenced them in writing this article.

Authors' contributions

This article is based on chapters 5 and 6 of the doctoral dissertation of L.S. (2010:121-160) and H.J.H. was the study leader.

References

Babbie, E., 2007, The practice of social research, 11th edn., Thomson Wadsworth, Belmont, CA. [ Links ]

Barbour, R. & Kritzinger, J., 1999, Developing focus group research: Politics, theory and practice, SAGE, London/Thousand Oaks, CA/New Delhi. [ Links ]

Blanche, M.T. & Durrheim, K. (eds.), 2002, Research in practice: Applied methods for the social sciences, University of Cape Town Press, Cape Town. [ Links ]

Cooper, D.R. & Schindler P.S., 2008, Business research methods, 10th edn., McGraw Hill, New York, NY. [ Links ]

Cox, H., 1995, Fire from heaven: The rise of Pentecostal spirituality and reshaping of religion in the twenty-first century, Addison-Wesley Publishing Company, Reading, MA. [ Links ]

Davies, M.B., 2007, Doing a successful research project: Using qualitative or quantitative methods, Palgrave Macmillan, New York, NY. [ Links ]

De Vos, A.S., 1998, Research at grass roots, J.L. van Schaik Publishers, Pretoria. [ Links ]

Furlong, N.E., Lovelace, E.A. & Lovelace, K.L., 2000, Research methods: An integrated approach, Harcourt College Publishers, Orlando, FL. [ Links ]

Hardy, M.A. & Bryman, A., 2004, Handbook of data analysis, Sage Publications, London. [ Links ]

Hesse-Biber, S.N. & Leavy, P., 2006, The practice of qualitative research, Sage Publications Inc., Thousand Oaks, CA. [ Links ]

Kalu, O., 2008, African Pentecostalism: An introduction, Oxford, New York, NY. [ Links ]

Mason, J., 2006, Qualitative research, 2nd edn., Sage Publications, London. [ Links ]

Martin, D., 2002, Pentecostalism: The world their parish, Blackwell, Oxford, MA. [ Links ]

Morgan, D.L., 1998, The focus group guidebook, Focus Group Kit 1, Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA. [ Links ]

Mouton, J., 1996, Understanding social research, J.L. van Schaik Publishers, Pretoria. [ Links ]

Qualitative Data Analysis, n.d., viewed 09 December 2010, from http://onlineqda. hud.ac.uk/Intro_QDA/what_is_qda.php [ Links ]

Rubin, A. & Babbie, E. 2007, Essential research methods for social work, Thomson Brooks/Cole, Belmont, MA. [ Links ]

Sapsford, R., 2007, Survey research, Sage Publications, London. [ Links ]

Sapsford, R. & Jupp, V. (eds.), 1996, Data collection and analysis, Sage Publications, London/Thousand Oaks, CA/New Delhi. [ Links ]

Social Research Update 35: The importance of pilot studies, viewed 18 July 2009, from http://sru.soc.survey.ac.uk/SRU35.html [ Links ]

Soko, L., 2010, 'A practical theological assessment of the schisms in the Reformed Church in Zambia (1996-2001)', unpublished DTh dissertation, Stellenbosch University, viewed 15 December 2010, from http://hdl.handle.net/10019.1/5454 [ Links ]

Verstraelen-Gilhuis, G., 1982, From Dutch mission to RCZ, Franeker, Wever. [ Links ]

Correspondence to:

Correspondence to:

Jurgens Hendriks

171 Dorp Street, Stellenbosch 7600, South Africa

Email: hjh@sun.ac.za

Received: 11 Jan. 2011

Accepted: 11 June 2011

Published: 04 Nov. 2011

© 2011. The Authors. Licensee: AOSIS OpenJournals. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution License.

1.See http://academic.sun.ac.za/theology/netact.html.

2.In data analysis, categorisation is the process of using rules to partition the body of data (Cooper & Schindler 2008:700; Hardy & Bryman 2004:286; Mason 2006:52).

3.Triangulation can be described as a research process that allows multiple research methods for data collection. In many different ways, it seeks to gather diverse sources by using several perspectives and a variety of sampling strategies to ensure validity (Babbie & Rubin 2007:106; Blanche & Durrheim 2002:128; Cooper & Schindler 2008:185; De Vos 1998:359; Furlong, Lovelace E.A. & K.L. Lovelace 2000:543). It was obtained in Soko's research (2010).