Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

HTS Theological Studies

On-line version ISSN 2072-8050

Print version ISSN 0259-9422

Herv. teol. stud. vol.67 n.1 Pretoria Jan. 2011

AGVA FESTSCHRIFT

'Praise beyond Words': Psalm 150 as grand finale of the crescendo in the Psalter

Dirk J. Human

Department Old Testament Studies, University of Pretoria, South Africa

ABSTRACT

Without doubt the final hymn of the Psalter can be described as the climax, or grand finale, of the Israelite faiths most known hymnbook. In this psalm, sound and action are blended into a picture of ecstatic joy. The whole universe is called upon to magnify Yah(weh), the God of Israel. The text poses various exegetical challenges. In the past, Psalm 150 was traditionally analysed as a single text; but with the advent of the canonical and redaction-historical approaches to the interpretation of the Book of Psalms, Psalm 150 can be interpreted as part of the final Hallel (Pss 146–150), or Book V (Pss 107–150) of the Psalter. This view opens up new possibilities for reading the psalm in broader contexts and its broader literary context(s) illuminate its theological significance. This article is an attempt at reflecting on the psalms context(s), structure, Gattung and dates of origin, tradition-historical relations to the Pentateuch, Psalms and other Old Testament texts. Ultimately some reflections on the psalms theological significance will be suggested.

Introduction

Careful reflection on the faith experiences described in the Psalter results in a diverse kaleidoscope of vastly different portrayals – at once so real, and yet sometimes so deterring. There are cries and tears of lament, anger and vengeance; prayers for relief; trust that creates hope; the exuberant joy of praise and thanksgiving; wise reflection and many more – all portrayals of faith experiences built around the acting and felt absence or presence of the Israelite God, Yahweh.

Chaos, pain and destruction often threaten to dampen the existence and meaning of life. Praise and joy appear less often in the first part of the book. In Psalms 90-150 (Books IV-V) hymnic forms, hymns and hymnal pieces increase (Spieckermann 2003:142). Ultimately, these songs of praise cannot be suppressed and the different hymn collections (Pss 113-118; 135-136) culminate in the final Hallel (Pss 146-150) – the crescendo or fortissimo of the most famous Israelite hymnbook.

Psalm 150 appears to be the grand finale of this crescendo. Its content and atmosphere portray a language of pure praise. Is this text a denial of the previously described pain, doubt, anger, disbelief, or experiences of hopelessness? Does the psalm offer a realistic faith experience for individuals and faith communities? Or is the ritual act of praise a blind tool to manipulate the divine power towards outcomes of deliverance, healing, upliftment of distress, bringing about hope, or other positive incentives?

Psalm 150 poses various exegetical challenges. In the past the psalm was traditionally analysed as a single text; but with the advent of canonical and redactional-historical approaches to the interpretation of the psalms, Psalm 150 can be interpreted as part of the final Hallel (Pss 146-150), Book V (Pss 107-150), or the Psalter as a whole. This view opens up new possibilities for reading the psalm in multiple contexts. Not only the psalms possible historical context(s), but also its possible cultic and literary contexts could illuminate its theological significance.

This article is an attempt at reflecting on the psalms context(s), structure, Gattung and date(s) of origin, tradition-historical relations to the Pentateuch, Psalms and other Old Testament texts. Ultimately some reflections on its theological significance will be suggested.

Context in the Psalter

Composition and theology of Book V (Pss 107-150)

As final text of the Hebrew Psalter, Psalm 150 forms an integral part of Book V (Pss 107-150). Several scholars have contributed to the contemplation on the composition and theological perspectives of Book V (Pss 107-150).1 But despite a variety of possibilities a few theological characteristics prevail. The books language, composition, theological trends and open-endedness outline its own characteristic profile.

With the final doxology (Pss 146-150), the Egyptian Hallel (113-118), the hymnic twin psalms (111-112; 135-136) and numerous Hallelujah exclamations, Book V portrays a strong hymnic character (Koch 1998:251-258). The liturgical collections 113-118 and 120-134, bound by Psalm 119, underscore how the central part of Book V is liturgically orientated to the annual festivals Peah (113–118), abūot (119) and Sūkkot (120-134). Hereby the salvation-historical stations of the Egyptian exodus, the Torah at Sinai and the arrival in Jerusalem at Zion are theologically commemorated.

With an inclusion Book V is framed by hymnic praise and wisdom perspectives (107:42-43; 145:19-21): Yahwehs universal reign and providence for all creation are hailed. A challenge follows this praising of the gracious and loving Yahweh: the wise should react with insight to Yahweh and his deeds. The final Hallel (Pss 146-150) is a crescendo that perpetuates the theme of praising Yahweh - first by the individual (146), then the community (147) and ultimately the whole creation (Pss 148, 150; cf. Kratz 1996:26). In addition to the outside frame, an inside frame puts the emphasis on David (Pss 108-110; 111-112 and 138-144).2 This king David tends to be the persecuted servant3 of Yahweh, the universal king. This king David probably belongs to a re-interpretative category that reflects on Yahwehs people as his obedient servant, namely the (afflicted) individual, the community and the whole creation. In a concluding wisdom perspective this people of Yahweh is blessed (Pss 144:15). Without doubt the theology of Book V is embedded in a universal awareness.

Theologically Books IV and V compensate for the shattered hope caused by the Babylonian exile by focusing on Gods reign over all powers of destruction and on the importance of righteous conduct in the present age (Gillingham 2008:210). Book V as literary unit offers a meditative pilgrimage through Israelite history; where the afflicted servant of Yahweh travels from a position of distress in the exile, through the (second) exodus, guided by careful instruction of the Sinai Torah on the way to Zion. At Zion Yahweh is actively present as universal king, waiting to bless the god-fearing pilgrim who praises him in the company of the whole creation as his wise servant.4

The Psalter as a whole

The Psalter consists of a literary and theological framework of larger and smaller collections of which individual psalms can be related and from where they could be interpreted. The redactional division of the whole into five books (Pss 1-41; 42-72; 73–89; 90-106; 107-150) is well-known. This five-part division attributes a Pentateuch or Torah character to the Psalter, which is affirmed by the introitus Psalm 1 (Kraz 1996:13-28). From its overture the Book of Psalms can thus be read, sung, or meditated as Torah-obedience or Torah-worship.

Prior to Books IV-V, Psalms 2-89 form the first three Books of the Psalter. Psalm 2 introduces the enthronement of Yahwehs earthly king and his royal function; whilst Psalm 89 describes the downfall of this Jerusalem king. From the rise to the fall of this earthly monarch, Books I-III theologically express the history of the different faith experiences of this Israelite epoch – stumbling between exuberant joy and grievous lament. When the earthly king fails, Yahwehs portrayal as king is accentuated. Therefore the theological trend of Books IV-V emphasises the kingship of Yahweh with its consequences for the Israelite faith. Psalm 150 is not untouched by, or disconnected from, the theological portrayals of these Books.

The final Hallel (Pss 146-150)

Psalm 150 is the fifth and final psalm of the final Hallel. This doxology is not only bound by the inclusion framework - the Hallelujah calls in all five psalms - but on a redactional level as well the psalm as a whole forms the final or fifth doxology at the end of Book V (see Pss 41:14; 72:18-20; 89:53; 106:48; 150). This final collections summonses to praise Yahweh are therefore not only moulded into a five-part Torah character, but it conceptualises a Hermeneutics of Praise5 for the Book of Psalms as a whole.

As literary composition these five Hallelujah psalms form a unit.6 Through the composition technique of concatenatio keywords (Stichworte) and motifs (Leitmotive) are utilised to effectuate mutual binding. These five psalms not only show a progressive dynamic, where every psalm is part of a logical sequence,7 but the collection similarly exhibits a concentric structure.8 These literary and thematic features underscore the artistic character and cohesion of the units composition. Thematically, hymnic and creation terminology form important building stones in this Hallels conceptualised Hermeneutics of Praise.

Psalm 150 shares motifs, keywords, and themes with all five psalms from 145-149. Psalm 145 has a double function: it serves as final psalm of Book V (Pss 107-145), but also as a bridge between Book V and the final Hallel.9 Psalm 145:21b (let all his creatures praise his holy name for ever) resounds in 150:6 (let everything that has breath praise Yah) to emphasise the universal character of the praise to the king God, El, or Yah(weh). Reference to his mighty deeds (wyt_roWbg>) is found in 145:4, 11-12 and 150:2, whilst the motif of Gods greatness is described in 145:3 and 150:2.

Psalms 146 and 150 are not only bound by the hymnic inclusion Hallelujah; the motives nephesh (146:1; life) and neshamah (150:6; breath) also form an inclusion that frames this collection. This inclusion indicates a progression from the individual life who praises God (Ps 146), to every living being in the universe who should praise him (Ps 150).

In both Psalms 147:7 and 150:3 God is to be praised with the stringed instrument, the lyre (rAN*kiw). The notion of musical instruments in 149:9 (rAN kiw @t oB. lAx+mb.) concurs with the instruments in 150:3-4, namely the lyre (rAN*kiw), tambourine and dancing (lAx+mW @to b). Psalms 149:6 and 150:1a similarly share the reference to the divine name El.

Resemblances and shared motifs in form and structure between Psalms 148 and 150 are also evident. Psalm 148 is even called the twin brother of Psalm 150 (Mathys 2000:339-343).10 Both psalms call for the universal praise of Yah(weh), although Psalm 148 has a more elaborate list of who should praise Yahweh from heaven and earth. Its extended lists of addressees (148:1-6, 7-12), as well as its focus on Israel (148:14), are more particular in its descriptions than the call to all living beings in the cosmos to praise Yah (150:6). Psalm 150 is therefore more allusive in its universal call for praise than Psalm 148; the psalm rather uses the short forms of the divine names (El and Yah) and tends to be a universal correction on the particularities of Psalm 148 (Mathys 2000:343).

From its relationship to Book V (Pss 107-145) and the final Hallel (Pss 146-150), one may conclude that Psalm 150 was intentionally composed in view of its position as fifth psalm of the final Hallel.11 The presence of liturgical elements, cultic forms and musical instruments effect binding with the other psalms of the final Hallel. Its concise and summarising character allows for single psalms and other collections in the Psalter to identify with this text.

The movement from particular to indefinite universal descriptions and from Israel or Jerusalem or Zion- language to universal cosmic depictions in Psalm 150 indicates this psalms universal openness and open-endedness,12 categories from where the whole Psalter can be interpreted and a stance from where the reader or meditator of the Psalter could respond from his or her own Sitz(e) imLeben

Psalm 150 – Praise Beyond Words

Introduction

Psalm 150 is mostly portrayed as a hymn or final praise song13. Together with the four psalms of the final Hallel (Pss 146-150) it builds the doxological climax of the Psalm book. A close reading of the text reveals that the tenfold imperative summons for praise (vv. 1b-6), together with the imperative Hallelujah framework (vv. 1a, 6b), only reflect a constituent part of the usual Old Testament hymn.14 Neither specific reasons nor motivation for praise, introduced by the particle ki, appear in the psalm. Nobody is praising El or Yah(weh) directly. Only calls for praise occur. More accurate depictions are therefore given by other scholars when they are depicting the psalm as:

a series of calls to praise (Briggs & Briggs 1907:544; Allen 1983:323)

a doxology (Kissane 1954:336; Van der Ploeg 1974:507)

een lofzegging (De Liagre Bőhl 1968:226)

an introduction to a hymn (Seidel 1989:166)

hymnische and liturgische Aufrufe (Seybold 1996:547-548).

Crsemann (1969:80-81) has tried to resolve this problem through his depiction of the psalm as an imperative hymn (imperativischer Hymnus). According to his explanation the imperative form has lost its original function and has assumed a rhetorical form, which expresses the function to proclaim Gods praise.

The psalms language can indeed be linked to the Israelite cult and its worshipping community. According to form and content the calls for praise (vv. 1-6), liturgical forms (vv. 3, 5), references to the sanctuary (v. 1b), or cultic musical instruments (vv. 3-5) allude to the relation with the Israelite cult. But, the question remains as to whether the summons for praise was meant to elicit cultic rituals. Did the psalm originate to function in a specific cultic setting, as some suggest?15 Or not? The psalms indefinite descriptions, summarising character, open-endedness and appearance of both cultic and non-cultic musical instruments (vv. 3-5) cast doubt on its liturgical use. The psalm was therefore probably an intentional literary composition meant to serve as the climatic doxology of the final Hallel.16

Text and translation

The Masoretic text of Psalm 150 is well preserved and transmitted. Only two minor text variants seem to qualify for text-critical consideration. In verse 2aβ a few Hebrew manuscripts and the Syrian Peshitta suggest that the text should read bro B. (for his...) instead of bro B. (according to his...).17 Also in verse 4aα a few Hebrew manuscripts add the preposition B. before the noun lAx+m to read lAx+mB.W (and with dancing) of and dancing. These text critical suggestions have been made to follow the structure of the psalm where parallelisms in verses 1b-5 exhibit the preposition B. after the imperative Hallelu or Halleluhu. Psalm 149:4 also renders a reading with the preposition lAx+mB. (with dancing).

These suggested emendations have no significant impact on the theological interpretation of the psalm, and might only be applied for literary and artificial purposes. Argumentation for the alteration of the text therefore has no convincing firm grounds.

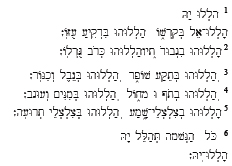

A possible translation of the Hebrew text reads as follows:

1 Praise the LORD (Yah).

Praise God (El) in his sanctuary; praise him in his mighty firmament

2 Praise him for his mighty deeds; praise him according to his surpassing greatness.

3 Praise him with the sounding of the sjofar; praise him with harp and lyre,

4 praise him with tambourine and dancing; praise him with strings and flute,

5 praise him with the clash of cymbals; praise him with resounding cymbals.

6 Let everything that breathes praise the LORD (Yah). Praise the LORD (Yah).

Composition and structure

The literary composition of Psalm 150 displays an artistic and distinct structure. Its brevity is striking, even more so when considering its theological impact on the final Hallel, on the Psalter as a whole and on the theology of the Israelite faith. Yahweh, the Israelite God, is characteristically described with the depictions El and Yah.

The psalm is framed by the imperative and the divine name (Hy" -Wll.h;(), Praise Yah (vv. 1a, 6b). This inclusion, which the psalm shares with Psalms 146-149, serves as the theological programme that builds the Psalters climax with an open call to universal praise.

Verses 1b-6a are further characterised by the tenfold appearance of the imperative verb form Wll.h;( or WhWl l.h. In 6b the jussive of the verb ll.h is used. As object of praise the name of God, El, appears in the first hemi-stichon of verse 1b; where after reference to him is constantly made by means of the suffix third person singular. Except for verse 2b the imperative is always followed by the preposition B (9 times).

The inner structure of verses 1b-6a is demarcated into three parts, namely 1b-2, 3-5 and 6. Verses 1b-2 are characterised by the appearance of parallelismus membrorum in every stichon; whilst verses 3-5 are stylistically bound by word pairs, repetition and sound imitation or onomatopoeia (v. 5). Rhyme (vv. 1b-2), alliteration of the a and sounds (vv. 1b-2), assonance (s sound in verse 1; sl sound in verse 5; sm sound in verses 5-6) and merism (1b) are also figures of style used by the poet. Syntactically the imperatives followed by the preposition B. effectuate further cohesion in verses 3-5.

In contrast to verses 1b-5, verse 6 introduces a reversed syntax. Instead of commencing with the expected Hebrew verb form the verse starts with the noun hm'v'N>h; lKo followed by the jussive form of ll.h (... This hemi-stichon expresses a final wish to praise Yah(weh).

Thematically the psalm expresses a series of calls to hail the Israelite king God El.18 Verse 1b states who should be praised and where this God El should be hailed. Verse 2 reveals why the addressees should praise Yah, whilst verses 3-5 describe how Yah should be praised. Finally, a wish for the universal praise of Yah(weh) is uttered (v. 6a). Schematically, the content pursues the following structure:

1a Call to praise Yah

1b Where shall El be praised

2 Why is God to be praised

3-5 How is God to be praised

6a Who is to praise Yah

6b Call to praise Yah

Detail analysis

Psalm 150 is a summons to praise. It consists of a series of calls to praise the Israelite High-God, Yahweh, with means that exceed conventional boundaries.

Hymnic frame (vv. 1a, 6b)

Like all psalms of the final Hallel, Psalm 150 is framed by the typical imperative Wll.h; and the divine name Hy (Praise Yah). The imperative of the verb ll.h appears 12 times. Theologically, these calls to praise Yah have a hymnic function: they proclaim Gods praise.

The tenfold repetition of the imperative (vv. 1b-5) certainly has theological significance. Like in Old Testament enemy lists (Ps 83:6-8) or genealogies (Rt 4:18-22), the number ten expresses completeness.19 The number could also be seen as an allusion to the ten creation words of God (Gn 1), or to the ten words of the Decalogue (Ex 20:1-17; Dt 4:13; 5:6-21 and 10:4).20 The Torah character of the praise is hereby embedded in the psalm. Any hymnic response on the part of the cultic visitor (or meditative reader) to the summons for praise would therefore signify complete obedience to Yahweh. To praise Yahweh is thus a deed of complete Torah obedience.

Where shall El be praised (vv. 1b-2)

According to form and content, verses 1b-2 form a literary unit. Both verses, each consisting of two hemi-stichoi, are characterised by its parallelisms (pair- and end rhyme of the sound) and the imperative followed by the preposition B.21 These verses attempt to locate the El-gods praise, with the suggestion of where he should be praised (v. 1b). It further provides limited motivation on why Yah deserves praise (v. 2).

Praise God (El) in his sanctuary; praise him in his mighty firmament. 2 Praise him for his mighty deeds; praise him according to his surpassing greatness.

Yah(weh) is described as El. This divine name immediately alludes to the supreme high god of Ugarit, El – the creator and judge god of the Canaanite pantheon. A similar description of Yahweh as El, the creator and King-God, appears in Psalm 149:2, 6. By creating the firmament Yahweh has established his power as creator (Gn 1:7-8). His surpassing greatness (v. 2aβ) thus confirms his High-God status as creator who rebuked the powers of chaos.22

El should be praised in his sanctuary (Av+d>q'B ... in his temple) and in his mighty firmament (AZ*(u (:yqIr>Bi). In the context of cultic worship, the sanctuary denotes the earthly abode of Gods dwelling place, namely the Jerusalem or Zion temple, or even another sanctuary (Pss 60:8; 68:18; 108:6; Am 4:2 etc.). But, is this indeed what the text is alluding to? If his mighty firmament (v. 2aβ) is a synthetic parallelism of his sanctuary (v. 2aα), then only the heavenly or transcendent world is summoned to praise Yah (Ps 29:1; 148:1). This is clearly not the intension of verse 1a.23 If both descriptions in his sanctuary and in his mighty firmament are merisms24 to signify the earthly and heavenly abodes of Gods reign, then a more comprehensive world is summoned to praise El. The descriptions in verse 2aβ (in his mighty firmament) and verse 6 (let everything that breathes ...) transcend the intention of praising El in an earthly abode alone.

In ancient times the earthly temple was understood to be a symbolic universe, a meeting place between heaven and earth (Hartenstein 1997:11, 22, 2007:117). Not only the earthly, but also the heavenly dimensions of Gods presence and reign is, for example, described in exilic or postexilic texts like Isaiah 6:1-4 and Ezekiel 1-3 and 10 (see Ezk 1:22, 25-26; 10:1). According to Psalm 93, the temple, cult and Torah provide access to Gods world and his kingship. There the mythic spaces, such as throne and on high (heaven), as well as his house (Zion) are not separate places – they refer to an earthly space, which connects heaven and earth. Although Yahwehs throne and the temple are not identical, they are symbolically related to express the abode from where his kingship emanates.25

Therefore both the spacial term sanctuary and the cosmological depiction firmament ((:yqIr>) in Psalm 150:1 are indefinite spatial descriptions26 which allude to the entirety of Gods reigning spheres. These terms include the categories of earthly and heavenly, immanent and transcendent, but also locality beyond these descriptions.

Verse 2 declares why Yah should be praised. The two aspects of his kingship mentioned here are his mighty deeds (v. 2aα) and his surpassing greatness (v. 2aβ). Mighty deeds (Pss 106:2; 145:4, 11-12) is an indefinite and general description of Yahwehs creation and salvation deeds in the history of his people Israel.27 These mighty deeds28 are heroic, warlike deeds of deliverance through which he subdues chaotic and endangering powers of destruction. This conquering of chaotic powers confirms his infinite greatness and incomparable kingship. Therefore his surpassing greatness (v. 2bβ) gives expression to his superiority over the entire cosmos and history. This verse therefore describes both what El has done and who he is.

How is God to be praised (vv. 3-5)

Verses 3-5 catalogue the largest list of musical instruments in the whole of the Psalter.29 In view of the cultic summons to praise (vv. 1-6), the notion of the sanctuary (v. 1b) and other liturgical calls (vv. 3, 5), a first reading of the text leaves the impression of a festive liturgy for temple worship (Weiser 1962:841), where a combined temple orchestra is ready to perform its grand symphony. Second readings raise new thoughts on the ritual performance of a single combined orchestra.

This literary unit addresses the manner in which God can be praised. Every hemi-stichon is introduced by the imperative form of ll.h with third person suffix followed by the preposition B... The preposition is followed by the object or musical instrument. Eight (or nine) instruments are mentioned which represent wind, string and percussion instruments.

The text reads as follows:

3Praise him with the sounding of the sjofar; praise him with harp and lyre; 4praise him with tambourine and dancing; praise him with strings and flute, 5praise him with the clash of cymbals; praise him with resounding cymbals.

Instruments are described in word pairs, with the exception of the first and last instruments – both sjofar (v. 3) and cymbals (v. 5) break the pattern of these word pairs. The sjofar appears alone, whilst the cymbals occur twice as cymbals of listening and cymbals of a loud blast. The question remains as to whether this repetition of the cymbals indicates different kinds of instruments30, or various functions31, executed by the cymbals.

The sequence and function of the musical instruments in these verses requires reflection, especially to determine its theological significance. A first possibility allows for a combined temple orchestra as part of a temple worship service (Weiser 1962:841). In such a scenario the instruments function focuses on the comprehensive and all encompassing praise offered by voices and instruments. But the presence of profane or non-cultic instruments in the list casts doubt on such a cultic ritual act.

Another group of scholars are convinced that verses 3-5 divides the participating congregants into three groups.32 This threefold division is suggested by texts like Psalms 115:9-11, 118:2-4 and 135:19-20. The participants are, according to these psalms, confined to the Israelites, the house of Aaron (priests and Levites) and ordinary believers. But according to the instruments of Psalm 150:3-5 some scholars are convinced that the suggested groups are:

the priests who blow the sjofar (Jos 6:4, Neh 12:35, 41; 1 Chr 15:24; 16:6; 2 Chr 29:26)

the Levites who play the harp, lyre and cymbals (Neh 12:27; 1 Chr 15:16; 16:5; 25:1,6; 2 Chr 29:25)

the laity who play the rest of the instruments (Gn 4:21; Job 21:12; Ex 15:20; Jdg 11:35; 1 Sm 18:6).

A major objection against this hypothesis is that the use of the sjofar was not reserved for the priests alone and that the harp and lyre were not only played by the Levites.33 The arrangement of the instruments in verses 3-5 to fit these three mentioned categories is therefore not convincing.

A suggestion to use spatiality and the structure of the Jerusalem temple to understand the arrangement of the instruments (and the theology of Psalm 150) offers a more convincing solution.34 The linguistic structure of the text reflects an analogy with the Zion temple building. The temple is the mythological centre of the universe and the symbolic sphere of Gods abode and reign. Relevant for this analogy is the innermost part of the temple, the court of the priests and the outside court for the lay people. A spatial movement from inside to outside35 and the wider expansion of cultic musical instruments across the boundaries into the spheres of the profane, characterise the nature of the theology of this part of the psalm. Not only cultic groups, but also social groups with their musical activities outside the cult, are summoned to praise God.

The instruments enumerated in verses 3–5 include the:

sjofar36

harp37 and lyre38

tambourine39 and dancing40

strings41 and flute42

and cymbals.43

These instruments performed various functions in- and outside the cult or temple worship.

The sjofar was a signal instrument in cultic and military situations.44 It also had royal associations, as it was blown when the king or leader appeared (2 Sm 15:10; 1 Ki 1:34, 39, 41; 2 Ki 9:13). As the oldest and most used instrument in Old Testament times the sjofar was the horn of a ram or a wild bovine. From the innermost part of the temple the sjofar was blown as the signal to worshippers that God is appearing (theophany), or that they should bow down, shout in praise or pray.

The harp and lyre were both stringed instruments. They often appear alone, but are sometimes mentioned together. They were used as musical accompaniment in the both the profane (Gn 4:21) and cultic spheres of life and supported the words of songs and choirs, especially hymns and thanksgiving songs (Pss 33:2; 57:9; 21:22; 81:3; 147:7; 149:3). Hereby they supported the praise of the divine. Both instruments differed in size and shape as well as in the number of strings.45 Either a plectrum of wood (or other material), or the fingers of the right hand, were used to play the strings (Oesterley 1939:591). According to the Chronistic History these stringed instruments belonged to the spheres of the Levitical professional musicians (1 Chr 15:16, 28; 16:5, 25:6; 2 Chr 9:11, 20, 28). Harp and lyre therefore belong to the adjacent part of the priestly court.

Women were associated with the tambourine and dancing.46 The tambourine, or timbrel, was a hand drum struck rhythmically with the hand. It was used as the rhythm instrument when women performed ritual dancing in a circle (Jr 31:4; Ex 15:20; Is 30:32; Pss 81:3; 149:3) to celebrate victory or to express joy. This musical activity happened outside the spheres of the sanctuary and cult (Seidel 1981:95). Whether it became part of the temple musical activities during the Second Temple period remains uncertain (1 Chr 25:5; Ezr 2:65; Neh 7:67).

The strings and flute were melody instruments. Strings (~yNI mi) appear as instrument or group of instruments in Psalm 45:9, whilst flute (bg)W()) occurs in Genesis 4:21, Job 21:12 and 30:31, most probably as wind instrument. The nature of both instruments remains unclear (Braun 2002:31). The bg)W( is usually interpreted as a flute or lute47, but because of its connection with kinnor (lyre; see Job 30:31 and 11QPs 151:2) it is also seen as a stringed instrument. These strings were probably not played by cultic musicians, whilst the flute also belonged to the profane sphere where wandering professional musicians performed music from place to place (Seidel 1981:95). Both the instruments and activities of women and folk musicians are associated with the spheres of the outer-court (or the non-cultic space outside the temple).

Finally the cymbals resound in our musical list. Either two kinds of cymbals, or two different functions performed by them, are described in verse 5.48 The text denotes them as cymbals of hearing and cymbals of a loud blast. Both the repetition and sound imitation (onomatopoeia of yl ec.l.ciB) applied by the poet create the effect of accumulative festive joy.49 The crescendo has reached a climax. By producing loud sounds participants of a worship service mediate contact with God, whilst praising and singing under the accompaniment of cymbals and other instruments (2 Chr 5:11-14).50 It is important to note that cymbals were not clearly linked to the temple cult (2 Sm 6:5), as only the late texts of the Chronistic History indicate them as cultic instruments.51 They were nonetheless related to religious ritual and the people of Israel.

From the preceding description it becomes evident that not all mentioned musical instruments (vv. 3-5) were linked to temple worship or cultic personnel. The poet therefore created an ideal and imaginative orchestra,52 a literary symbolic universe or cosmic cathedral, in analogy to the structure of the temple building. By following the temple structure in a movement from inside to outside and by using conventional musical instruments of the time, the poet alluded to worlds beyond instruments, spaces, people and categories – who are all called upon to respond in praise to God.

It is further clear that music and musical instruments not only sufficed as support or extension of the human voice, but the noisy sounds produced by these instruments and cultic participants served as medium of contact between worshippers and the divine world.53 Loud sounds in the cult established contact between god and people. Beyond these functions the power of music evokes the aesthetic beauty of sound that creates pleasant feelings of joy and hope, which exceeds the power and function of words.

Who is to praise Yah (v 6a)

The psalm culminates in the open ended wish that all life should praise Yah. With unconventional Hebrew syntax, which emphasises the subject of praise. hm'v'N>h; lK (everything that breathes), the psalm renders an indefinite universal character to this group of praising subjects. Hereby the categories of the individual and Israel/Judah as Gods people are extended to a category of life which expresses a comprehensive universal dimension:

6 Let everything that breathes praise Yah.

hm'v'N> (life or breath) alludes to Genesis 2:7, where God created human kind and blew the breath of life (Pr 20:27) into their nostrils. All human beings received this gift of vitality (Jos 10:40; Dt 20:16; Jos 11:11, 14; 1 Ki 15:29; Job 32:8; 33:4; Is 42:5). Life is not only reserved for human beings, but also given to birds and animals (Gn 7:22). All life originates from El as Creator. Verse 6 thus not only functions as a summons that all life returns this breath to the creator as a deed of praise, but the verse alludes to the dependence of all living creatures upon God. This wish, which alludes thematically to Psalm 145:21b, serves as the summarising conclusion of Psalm 148s extended list of living beings that are to praise Yah in heavens and on earth.

Relation to Psalm 1 and the Psalter

It is important to reflect for a moment on the relationship of Psalm 150 to Psalm 1 and to the rest of the Psalter, in order to discover some nuances on the concept of praise. The canonical and redaction-historical approaches to reading the psalms require a comparison of these perspectives.

Both Psalm 1 and 150 are corner psalms (Eckpsalmen); the one to introduce and the other to conclude the Psalter. In Psalm 1 the individual is addressed and the importance of the Torah is emphasised for the joyful and happy life in the community of Yahweh believers. Psalm 150 is a universal call on all that breathes to praise the same God vigorously. As fifth psalm of the final Hallel and of Book V, Psalm 150 extends ten imperative summonses for praise, a feature which attributes a Decalogue and Torah character to the psalm. Both psalms thus frame the Psalter with the theolegomenon of the Torah. Inevitably praise in Psalm 150 is coloured by this Torah character.54 In a life of faith, the Torah-obedience visualised in Psalm 1 is thus embedded in the execution of praising Yahweh (of Ps 150), whatever means this praise assumes.55 Praise in various forms is thus a way to concretise and realise Torah- obedience.56 This lyric includes obedience and is not transcending, superseding, or overcoming it.

As summation and keystone (Schluβstein) of the Psalter Psalm 150 draws all the experiences of the Psalter together into the denominator of praise. When reaching Psalm 150, the believer (reader or meditator) is fully aware of the kaleidoscope of diverse faith experiences as described throughout the Psalter. The praise of Psalm 150 therefore cannot (and does not) obliterate pain, doubt, thoughts of vengeance, misfortune and failure.57 In other words, this praise is no cancellation of Psalms 2-149. This praise carries the scars of life. In the spirit of Paul Ricoeurs idea of a second navet this praise is only a return of the stumbling believers breath to its origins, Yahweh – the Israelite God of cosmos and history and incomparable creator of the universe.

Dating of Psalm 150

To determine the origin of Psalm 150 is no easy endeavour. Scholars should be hesitant to compromise themselves on a final word about the historical, cultic, or literary settings of Psalm 150. It is true that there are no adequate indications as to its time of origin (Eaton 2003:484).

Suggestions to date the psalm vary and are sometimes vague and oblique.58 Possibilities vary from a pre-exilic59 to a post exilic period. Most scholars date the psalm in the post-exilic period60, more specifically around or after the Second Temple period61, because of the psalms position in the Psalter, the language in the text and the appearance (or absence) of some musical instruments.

This dating of between 500 and 100 BCE62 does give direction, but is still too broad. More precise settings are suggested and motivated by scholars. This include the period between 500 and 400 BCE in the time of Nehemiah,63 the period posterior to the trials of Ezra and Nehemiah,64 a setting after the time of Chronicles65 and a time period prior to the book of Daniel (166-165 BCE).66

If the final redaction of the Psalter is to be dated between 300 and 250 this should give an indication of a setting to date Psalm 150. The psalm surely belongs to the final stages of the formation of Book V and the Psalter. An awareness of allusions to Genesis 1-2 (1:7-8; 2:7; 7:22), Ezekiel 1-3 and 10 (1:22, 25-26; 10:1) and Isaiah 6 (6:1-4) can certainly motivate a post-exilic setting for Psalm 150. The symbolism of the numbers 5 and 10 attributes a Torah character to the psalm. In addition to this, the Chronicler creates the awareness of how important a role music had played in the postexilic Yehud community. The importance of Torah and music is an indication to situate our psalm after Ezra, Nehemiah and Chronicles. Furthermore, the universal trend in the psalm, its indefinite descriptions, and its summarising character all play a decisive role in a choice for a Sitz im Leben after the time of the Chronicler. The Qumran text of the psalm (11QPsª) also supports the Masoretic text reading and its variants. This confirms the close distance between these texts. In view of these arguments I would like to suggest a date between 350-250 BCE for the dating of Psalm 150.

Theological significance

During the history of music, Psalm 150 has sufficed as motivation for several musical compositions. Benjamin Britten, Igor Stravinski, Anton Bruckner and Cezar Franck are testimonies of how this grand finale of the Psalter inspired their works (Ravasi 1998:859).

Psalm 150 unites all the voices of the Psalter by means of a series of summons to praise El, the Israelite God of cosmos and history. The psalm is therefore not to be read in isolation. As Schluβstein (keystone) of the whole Psalter it unifies all the diverse experiences of the Psalter in praise.

The creator God of Israel is to be praised universally: in heaven and on earth, transcendently and immanently, inside and outside the temple and cult, in cosmos and in history. His surpassing greatness exceeds the concepts of space and time in human understanding. Through his mighty deeds he has shown himself in cosmos and history to be incomparable King-God.

Music and musical instruments not only supply ways of praising God. It is a power that exceeds the praise offered by the singing or speaking or shouting or dancing. Music offers praise beyond words. In Psalm 150 the musical instruments do not only function as signals, accompaniment and support, rhythm and melody, or contact with the divine; they represent worlds and words beyond instruments, spaces, people and social categories. Everyone and everything that lives should praise God with whatever means: priests, cultic and non-cultic officials, men and women, individuals and communities, lay people and professionals, human beings and animals.

The power of music evokes the aesthetic beauty of sound that creates pleasant feelings of joy and hope. This hope is realised through all the varied forms of praise. And this praise is not ignorant of the sorrow and pain, doubt and hardship, failure and misfortune, or other experiences described in all other 149 psalms. All encompassing praise reckons with these experiences on the spectrum between lament and hymn. Such praise revives life and is simultaneously an expression of a Torah embedded relationship with this God of the universe.

St Augustine called Psalm 150 a Magnum opus hominis laudare Dominum (A great work of humanity to praise the Lord). This is a fitting description. Anyone searching for life could respond to this magnum opus. Hereby the vision of Psalm 1:2 for obtaining joy and life can be realised. To respond entails a wise deed.

Acknowledgement

I dedicate this article to a friend and colleague, Andries van Aarde, for his friendship and contribution to the Biblical Sciences in South Africa.

References

Allen, L.C., 1983, Psalms 101 – 150, Word Biblical Commentary, vol. 21, Word, Waco, TX. [ Links ]

Anderson, A.A., 1972, The Book of Psalms, New Century Bible Commentary, Marshall, Morgan & Scott, London/Eerdmans, Grand Rapids, MI. [ Links ]

Bakon, S., n.d., s.a. Music and the Bible, Dor le Dor 161–173. [ Links ]

Ba. Musik und musikinstrumente, 1989, in Herausgegeben von K. Gutbrod & R. Kcklich (Hrsg.), Calwer Bibellexikon, 6. Auflage, pp. 930-937, Calwer Verlag, Stuttgart. [ Links ]

Braun, J., 1999, Die Musikkultur Altisraels/Palstinas: Studien zu archologischen, schriftlichen und vergleichenden Quellen, Orbis Biblicus et Orientalis 164, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Gttingen. [ Links ]

Briggs, C.A. & Briggs, E.G. (eds.), 1907, Critical and exegetical commenatry on the Book of Psalms, vol. II, T & T Clark, Edinburgh. [ Links ]

Brueggemann, W., 1984, The Message of the Psalms: A Theological Commentary, Augsburg Publishing House, Minneapolis, MN. [ Links ]

Brueggemann, W., 1991, Bounded by obedience and praise: The Psalms as canon, Journal for the Study of the Old Testament 50, Sheffield Academic Press, Sheffield. [ Links ]

Brueggemann, W., 1995, The Psalms and the life of faith, Fortress, Minneapolis, MN. [ Links ]

Burden, J.J., 1991, Psalms 120-150, NG Kerk Uitgewers, Kaapstad. [ Links ]

Clifford, R.J., 2003, Psalms 73-150: Abingdon Old Testament Commentaries, Abingdon Press, Nashville, TN. [ Links ]

Creach, J.F.D., 1996, Yahweh as Refuge and the Editing of the Hebrew Psalter, JSOT Supplementum 217, Sheffield Academic Press, Sheffield. [ Links ]

Crsemann, F., 1969, Studien zur Formgeschichte von Hymnus und Danklied in Israel, Wissenschaftliche Monographien zum Alten und Neuen Testament 32, Neukirchener Verlag, Neukirchen. [ Links ]

Dahood, M., 1970, Psalms III. 101-150: Introduction, translation, and notes with an appendix. The grammar of the Psalter, The Anchor Bible, Doubleday & Company Incorporated, New York. [ Links ]

Deissler, A., 1964, Die Psalmen, Patmos, Dsseldorf. [ Links ]

De Liagre Bhl, F.M.Th & Gemser, B. (eds.), 1968, De Psalmen, Tekst en Uitleg, Callenbach, Nijkerk. [ Links ]

Delitzsch, F., 1949, The Psalms, transl. F. Bolton, Eerdmans, Grand Rapids, MI. [ Links ]

Duhm, B., 1899 (1922), Die Psalmen, Kurzer Handkommentar zum Alten Testament, J C B Mohr (Paul Siebeck), Freiburg. [ Links ]

Dumbrill, R.J., 2000, Musicology and Organology of the Ancient Near East, Tadema Press, London. [ Links ]

Eaton, J., 2003, The Psalms: A Historical and Spiritual Commentary with an Introduction and New Translation, T & T Clark, London/New York. [ Links ]

Falkenstein, A. & Von Soden, W. (eds.), 1953, Sumerische und Akkadische Hymnen und Gebete, Artemis Verlag, Zrich/Stuttgart. [ Links ]

Farmer, W.R., 1998, The International Bible Commentary: A catholic and ecumenical commentary for the twenty-first century, The Liturgical Press, Collegeville, PA. [ Links ]

Fohrer, G., 1993, Psalmen, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin/New York. [ Links ]

Geiger, M. & Kessler, R. (eds.), 2007, Musik, Tanz und Gott: Tonspuren durch das Alte Testament, Katholisches Bibelwerk Verlag, Stuttgart. [ Links ]

Gerstenberger, E.S., 1988, Psalms. Part I: With introduction to cultic poetry. FOTL XIV, Eerdmans, Grand Rapids, MI. [ Links ]

Gerstenberger, E.S., 2001, Psalm 150: Final Praise, in R.P. Knierim, G.M. Tucker & M.A. Sweeney (eds.), Psalms Part 2 and Lamentations, pp. 458-461, Eerdmans, Grand Rapids, MI. [ Links ]

Goldingay, J., 2008, Psalms: Volume 3. Psalms 90-150, Baker Academic Books, Grand Rapids, MI. [ Links ]

Grg, M. & Lang, B. (eds.), 1995, Neues Bibellexikon, Band II. H–N, Benziger, Zrich/Dsseldorf. [ Links ]

Goulder, M.D., 1998, The psalms of the return (Book V, Psalms 107-150), JSOT Supplementum 258, Sheffield Academic Press, Sheffield. [ Links ]

Gunkel, H., 1926, Die Psalmen, 4. Auflage, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Gttingen. [ Links ]

Hartenstein, F., 1997, Die Unzugnglichkeit Gottes im Heiligtum: Jesaja 6 und der Wohnort JHWHs in der Jerusalemer Kulttradition, Neukirchener Verlag, Neukirchen. [ Links ]

Hartenstein, F., 2007, Wach auf, Harfe und Leier, ich will wecken das Morgenrote (Psalm 57,9) – Musikinstrumente als Medien des Gotteskontaks im Alten Orient und im Alten Testament, in M. Geiger & R. Kessler (Hrsg.), Musik, Tanz und Gott: Tonspuren durch das Alte Testament, pp. 101-128, Katholisches Bibelwerk Verlag, Stuttgart. [ Links ]

Henneke, H., 1936, Das Buch der Psalmen: bersetzt und erklrt, Peter Hanstein Verlagsbuchhandlung, Bonn. [ Links ]

Hossfeld, F.L. & Zenger, E. (eds.), 2008, Psalmen 101-150: Űbersetzt und ausgelegt, Herders Theologischer Kommentar zum Alten Testament, Herder, Freiburg/Basel/Wien. [ Links ]

Howard, D.M., 1993, A contextual reading of Psalms 90-94, in J.C. McCann (ed.), The Shape and Shaping of the Psalter, JSOT Supplementum 159, pp. 108-123, Sheffield Academic Press, Sheffield. [ Links ]

Janowski, B., 1989, Das Knigtum Gottes in den Psalmen: Bemerkungen zu einem neuen Gesamtentwurf Zeitschrift fr Theologie und Kirche 86, 389-454. [ Links ]

Kidner, D., 1975, Psalms 73-150: A commenatry on Books III-V of the Psalms, Intervarsity Press, Leicester/Downers Grove, IL. [ Links ]

Kirkpatrick, A.F., 1957, The Book of Psalms, University Press, Cambridge. [ Links ]

Kissane, E.J., 1954, The Book of Psalms: Translated from a critically revised Hebrew text. Volume II – Psalms 73-150, Browne and Nolan, Dublin. [ Links ]

Kittel, R., 1922, Die Psalmen, Kommentar zum Alten Testament, A Dichertsche Verlagsbuchhandlung, Leipzig. [ Links ]

Knierim, R.P., Tucker, G.M. & Sweeney, M.A. (eds.), 2001, Psalms Part 2 and Lamentations, Eerdmans, Grand Rapids, MI. [ Links ]

Koch, K., 1998, Der Psalter und seine Redaktionsgeschichte, in E. Zenger (Hrsg.), Der Psalter in Judentum und Christentum, n.p., Herder Verlag, Freiburg/Basel/Wien. [ Links ]

Knig, E., 1927, Die Psalmen: Eingeleitet, bersetzt und erklrt, Verlag von C Bertelsmann, Gtersloh. [ Links ]

Kraovec, J. (ed.), 1998, The interpretation of the Bible, JSOT Supplementum 289, Sheffield Academic Press, Sheffield. [ Links ]

Kraus, H.-J., 1978, Psalmen. 2. Teilband: Psalmen 60-150, Biblischer Kommentar Altes Testament XV/2, Neukirchener Verlag, Neukircken. [ Links ]

Kraz, R.G., 1992, Die Gnade des tglichen Brots. Spte Psalmen auf dem Weg zum Vaterunser, Zeitschrift fr Theologie und Kirche 89, 1-40. [ Links ]

Kraz, R.G., 1996, Die Tora Davids. Psalm 1 und die doxologische Fnfteilung des Psalters, Zeitschrift fr Theologie und Kirche 93, 13-28. [ Links ]

Larrick, G., 1990, Musical References and Song texts in the Bible, Edwin Mellen Press, Wales. [ Links ]

Leuenberger, M., 2004, Konzeptionen des Kőnigtum Gottes im Psalter: Untersuchungen zu Komposition und Redaktion der theokratischen Bcher IV-V im Psalter, ATANT 83, Theologischer Verlag, Zrich. [ Links ]

Leupold, H.C., 1969, Exposition of the Psalms, Baker Book House, Grand Rapids, MI. [ Links ]

Manders, C., Die simfinieorkes in die psalmbundel, unpublished MA Dissertation, Department of Ancent Languages, University of Pretoria. [ Links ]

Mar, L., 2001, Psalm 150: Die klimaks van die regverdige se lewensweg, Ekklesiastikos Pharos 83, 15-25. [ Links ]

Mathys, H.P., 2000, Psalm CL, Vetus Testamentum 50(1), 329-344. doi.10.1163/156853300506404 [ Links ]

Matthews, V.H., 1992, Music and musical instruments, in D.N. Freedman et al. (eds.), Anchor Bible Dictionary, vol. 4, K-N, Doubleday, New York/London. [ Links ]

Mays, J.L., 1994, Psalms: Interpretation: A Bible Commentary for Teaching and Preaching, John Knox Press, Louisville, KY. [ Links ]

McCann, J.C. (ed.) 1993, The Shape and Shaping of the Psalter, JSOT Supplementum 159, Sheffield Academic Press, Sheffield. [ Links ]

McFall, L., 2000, The evidence for a logical arrangement of the Psalter, Westminster Theological Journal 62, 223-256. [ Links ]

Mowinckel, S., 1966, Psalmenstudien Buch I-II, Verlag P Schippers N V, Amsterdam. [ Links ]

Mller, G. (ed.), 2000, Theologische Realenzyklopdie, Band 23, Studienausgabe Teil II, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin/New York. [ Links ]

Noordzij, A., 1934, De Psalmen: Opnieuw uit de grondtekst vertaald en verklaard, deel 3, Kok, Kampen. [ Links ]

Oesterley, W.O.E., 1939, The Psalms: Translated with text-critical and exegetical notes, Macmillan, London/New York. [ Links ]

Quesson, N., 1990, The Spirit of the Psalms, Paulist Press, New York. [ Links ]

Ravasi, G., 1998, Psalms 90-150, in W.R. Farmer et al. (eds.), The International Bible Commentary: A catholic and ecumenical commentary for the twenty-first century, pp. 841-859, The Liturgical Press, Collegeville, PA. [ Links ]

Schmid, B., 1995, Musikinstrumente, in M. Grg & B. Lang (Hrsg.), Neues Bibellexikon: Band II. H – N, pp. 855-858, Benziger, Zrich/Dsseldorf. [ Links ]

Schmidt, H., 1934, Die Psalmen: Handbuch zum Alten Testament I/15, J C B Mohr (Paul Siebeck), Tbingen. [ Links ]

Seidel, H., 1981, Ps. 150 und die Gottesdienstmusik in Altisrael, Nederlands Theologisch Tijdschrift 35, 89-100. [ Links ]

Seidel, H., 1983, Untersuchungen zur Auffhrungspraxis der Psalmen im altisraelitischen Gottesdienst, Vetus Testamentum 33, 503-509. doi.10.2307/1517985 [ Links ]

Seidel, H., 1989, Musik in alt Israel: Beitrge zur Erforschung des alten Testaments und des antiken Judentums 12, Peter Lang, Frankfurt. [ Links ]

Seidel, H., 2000, Die Psalmen: Handbuch zum Alten Testament I/15, J C B Mohr (Paul Siebeck), Tbingen. [ Links ]

kulj, E., 1998, Musical instruments in Psalm 150, in J. Kraovec (ed.), The interpretation of the Bible, JSOT Supplementum 289, Sheffield Academic Press, Sheffield. [ Links ]

Spieckermann, H., 2003, Hymnen im Psalter: Ihre Funktion und ihre Verfasser, in E. Zenger (ed.), Ritual und Poesie: Formen und Orte Religiser Dichtung im Alten Orient, im Judentum und im Christentum, Herders Biblische Studien, Band 36, pp. 137-162, Herder, Freiburg/Basel/Wien. [ Links ]

Stainer, J., 1914, The music of the Bible: With some account of the development of modern musical instruments from ancient types, Novello, London. [ Links ]

Terrien, S., 2003, The Psalms: Strophic structure and theological commentary, Eerdmans, Grand Rapids, MI. [ Links ]

Towner, W.S., 2003, Without our Aid He did us make: Singing the Meaning of the Psalms, in B. Strawn & N.R. Bowen (eds.), A God so Near: Essays on Old Testament Theology in honour of Patrick D Miller, pp. 17-34, Eisenbrauns, Winona Lake, IN. [ Links ]

Van der Ploeg, J.P.M., 1974, Psalmen deel II: Psalm 76–150, De Boeken van het Oude Testament, J J Romen & Zonen Uitgevers, Roermond. [ Links ]

Weber, B., 2003, Werkbuch Psalmen II: Die Psalmen 73 bis 150, Verlag W Kohlhammer, Stuttgart. [ Links ]

Weiser, A., 1962, The Psalms: A Commentary, Old Testament Library, SCM Press, London. [ Links ]

Werner, E., 1962, Musical instruments: The Interpreters Dictionary of the Bible, 4 vols, Abingdon Press, Nashville, TN/New York. [ Links ]

Whybray, N., 1996, Reading the Psalms as a book: Recent views on the composition and arrangement of the Psalter, Sheffield Academic Press, Sheffield. [ Links ]

Westemann, C., 1961/62, Zur Sammlung des Psalters, Theologia Viatorum, 278-284. [ Links ]

Wilson, G.H., 1984, Evidence of editorial divisions in the Hebrew Psalter, Westminster Theological Journal 34(3), 337-352. [ Links ]

Wilson, G.H., 1985, The Editing of the Hebrew Psalter, SBLDS 76, Scholars Press, Chico, CA. [ Links ]

Wilson, G.H., 1992, The shape of the book of Psalms, Interpretation 46, 129-142. [ Links ]

Wilson, G.H., 1993, Shaping the Psalter. A Consideration of editorial Linkage in the Book of Psalms, in J.C. McCann (ed.), The Shape and Shaping of the Psalter, JSOT Supplementum 159, Sheffield Academic Press, Sheffield. [ Links ]

Zenger, E., 1991, Ich will die Morgenrte wecken: Psalmenauslegungen, Herder, Freiburg. [ Links ]

Zenger, E., 1996, Komposition und Theologie des 5. Psalmbuches 107-145, Biblische Notizen 82, 97-116. [ Links ]

Zenger, E., 1997, Dass alles Fleisch den Namen seiner Heiligung segne Ps 145,21, Biblische Zeitschrift 41(1), 1-27. [ Links ]

Zenger, E. (ed.), 1998, Der Psalter in Judentum und Christentum, Herder Verlag, Freiburg/Basel/Wien. [ Links ]

Zenger, E., 1998, Der Psalter als Buch. Beobachtungen zu seiner Entstehung und Funktion, in E. Zenger (ed.), Der Psalter in Judentum und Christentum, pp. 1-58, Herder Verlag, Freiburg/Basel/Wien. [ Links ]

Zenger, E., 2008, Psalm 150, in F.L. Hossfeld & E. Zenger (Hrsg.), Psalmen 101-150: Űbersetzt und ausgelegt, Herders Theologischer Kommentar zum Alten Testament, pp. 871-885, Herder, Freiburg/Basel/Wien. [ Links ]

Correspondence to:

Correspondence to:

Dirk Human

Postal address: Faculty of Theology, Department Old Testament Studies, University of Pretoria,

Lynwood Road, Hatfield 0083, Pretoria, South Africa

Email: dirk.human@up.ac.za

Received: 26 July 2010

Accepted: 01 Sept. 2010

Published: 07 June 2011

1. Significant work has been done by Westermann (1961/62:278-284); Wilson (1984:337-352, 1985, 1992:129-142, 1993:72-82); Whybray (1996); Koch (1998:243-277); Kraz (1992:1-40, 1996:13-28); Zenger (1996:97–116, 1998:1-58); Goulder (1998) and McFall (2000:223-256).

2. Zenger (1996:114) depicts this part of the frame as eskatologisch messianisch.

3. The affliction and distress of this servant David are reflected in Psalms 140-143.

4. Wilson (1985:227-228) describes Book V as an answer to the plea of the exiles to be gathered from the diaspora. The answer given is that deliverance and life thereafter are dependent on an attitude of dependence and trust in Yahweh alone.

5. See Zenger (1997:14-20) for a full discussion of Psalms 146-150 as Hermeneutik des Psalters.

6. Zenger (1997:15-16) enumerates these features. This unity is built by the inclusion frame of the Hallelujah calls; the hymnic character of every psalm; intensive keyword and motif repetition; the creation theology in all five psalms and focus on Israel (Pss 147-149); the inclusion of 146:1 and 150:6 nephesh and hanishamah.

7. This progression is especially seen in the notion of the addressees or subjects from who praise should go out (Zenger 1997:16). They are David (Ps 146); Jerusalem or Zion and Israel or Jacob (147); heavenly beings and cosmos or earth (Ps 148); community of Hasidim (Ps 149) and everything who has breath (Ps 150). Consecutive psalms also pursue themes of the previous psalm to build the theme out. This includes: Yahwehs eternal kingship at Zion (Pss 146:10/147:12); Yahwehs special treatment of his people Israel (Ps 147:19-20/148:14/149:5); Yahwehs all encompassing reign is praised from Zion (Ps 147:12), heaven (Ps 148:1), earth (Pss 148:7), temple as symbol of cosmos (Ps 150:1).

8. In the concentric structure there are resemblances shared by Psalms 146 and 150; Psalms 147 and 149 with Psalm 148 capturing the central focus (Zenger 1997:18). All five psalms share motives of a creation theology. Psalms 146 and 150 have allusions to Genesis 1 and use the verb hll for praise; Psalms 147 and 149 share the motives: Israel, Zion, anavim, rşh, mpt and different verbs for praise; Psalm 148 has allusions to Genesis 1-2, the motive Israel, and uses the verb hll for praise. Resemblances also exist between Psalms 148 and 150.

9. See Wilson (1993:72-82) and Zenger (1996:97, 101).

10. Because of their similarities the question is raised whether both psalms have the same author, or not (Mathys 2000:340).

11. See the viewpoints of Mathys (2000:343), Leuenberger (2004), and Zenger (2008). Seidel (1981:91) argues that the psalm was created as a pure literary text because of its Situationsabstrakte Kommunikationsgeschehen. The psalm has no historical Sitz im Leben or definite cultic situation. Sein Sitz im Leben ist die Literatur. This intentional composition of the psalm as closing doxology for the final Book or Hallel is opposed by other scholars (Allen 1983:323) because of the presence of liturgical forms, cultic elements, and notion of cultic musical instruments. Anderson (1972:955) states that it is uncertain that the psalm was composed as concluding doxology to the entire Psalter. Gerstenberger (2000:458) is convinced that the psalm was not meant as literary text to be read or meditated, because of the cultic and form elements employed in the text.

12. Allen (1983:324) infers that the series of summonses, without the corresponding ground for praise, gives an open-ended effect to the psalm.

13. Most exegetes classify the psalm as a hymn (see e.g. Schmid 1934:258; Deissler 1964:572; Anderson 1972:954; Van der Ploeg 1974:507; Kraus, 1978:1149; Gerstenberger 2001:460; Clifford 2003:318; Weber 2003:384).

14. The structure of the Old Testament hymn normally consists of a call to praise, followed by the particle ki, and the reasons for praise. Ultimately the hymn concludes with a final call to praise (see Gerstenberger 1988:17; Brueggemann 1995:192).

15. Schmid (1934:258) vaguely mentions the setting of a feast without any further specification. Dahood (1970:150) only notes that the psalm has been intended originally for liturgical use, without giving any further detail of such a use. Foher (1993:72) is slightly more specific, when he mentions the possibilities of the daily service or a festival in the post-exilic period after 500 BCE.

16. See Van der Ploeg (1974:507). Seidel (1989:166) infers that the psalm was probably composed as final text of the final Hallel, but not intentionally composed as doxological conclusion of Book V (Pss 107-150).

17. The Qumran text of the psalm (11?Psª) also supports the Masoretic reading of the text.

18. In the ancient Near East, especially in Egypt and Mesopotamia, hymns and cultic music plays an important role in worship (Falkenstein & Von Soden 1953:59-130, 235-260).

19. See Weber (2003:385).

20. See Deissler (1964:572).

21. The second hemi-sti ch of verse 2 is an exception. Instead of the preposition B the text uses the preposition K..

22. Psalm 104 confirms Yahwehs greatness (Ps 104:1) because he is creator God (Ps 104:2) and the One who orders the water chaos (Ps 104:7-9). See Seybold (1996:547).

23. Against the opinions of Duhm (1922:484), Konig (1927:664), Delitzsch (1949:414), Dahood (1970:150), and Eaton (2003:485); who explain that the sanctuary refers primarily to Gods heavenly dwelling. Briggs & Briggs (1907:544) correctly notes that there is no reference in the psalm to heavenly beings or things.

24. Mare (2001:19) infers that the merism indicates die omvang en totaliteit van die lof wat aan God gebring moet word.

25. Hartenstein (1997:48).

26. Seidel (1981:91) describes the verses content as unbestimmte Ortsbestimmungen.

27. Psalm 106 depicts these deeds, inter alia, as the delivering deeds in Egypt, at the Reed sea, in the Sinai desert, at mount Sinai, at Meribah, and at times when Israel became unfaithful to Yahweh. References to his mighty deeds in Deuteronomy 3:24 alludes to the land occupation, whilst his greatness is connected in Deuteronomy 5:24 to the giving of the Decalogue, and in 9:26 and 11:2 to the deliverance from Egyptian slavery and the Reed sea, or other dangers during the desert wandering.

28. See Psalms 20:7; 54:3; 65:7; 66:7; 71:16; 79:11; and 89:14.

29. Several short lists of musical instruments appear in Psalms 33:2; 43:4; 47:6; 49:5; 57:9; 68:26;71:22; 81:3; 92:4; 98:5-6; 108:3; 137:2; 144:9; 147:7 and 149:3.

30. See Oesterley (1939:588).

31. Goldingay (2008:749).

32. Scholars who hold this opinion include Gunkel (1926:622-623), Herkenne (1936:458), Kissane (1954:336), Kirkpatrick (1957:832) and Leupold (1969:1007).

33. See Van der Ploeg (1974:508).

34. Hans Seidel (1981:97-100, 1989:166-167) has posed and developed this hypothesis.

35. See similar structures in Isa 6:1-4; Jeremiah 17:12 and Psalm 93 (Hartenstein 1997:45, 2007:119).

36. The shofar appears in Exodus 19:16, 19; 20:18; Joshua 6:4, 5, 6, 8, 9, 13, 16 20; Judges 3:27; 6:34; 7:8, 16, 18, 19, 20, 22; 1 Samuel 13:3; 2 Samuel 2:28; 6:15; 15:10; 18:16; 20:1, 22; 1 Kings 1:34, 39, 41; 2 Kings 9:13; Isaiah 18:3; 27:13; 58:1; Jeremiah 4:5, 19, 21; 6:1, 17; 42:14; 51:27; Ezekiel 33:3, 4, 5, 6; Hosea 5:8; 8:1; Joel 2:1, 15; Amos 2:2, 3:6; Zephaniah 1:16; Zachariah 9:14; Psalms 47:6; 81:4; 98:6; 150:3; Job 39:24, 25; Nehemiah 4:12, 14; 1 Chronicles 15:28; 2 Chronicles 15:14.

37. The harp appears in 1 Samuel 10:5; 2 Samuel 6:5; 1 Kings 10:12; Isaiah 5:12; 14:11; Amos 5:23; 6:5; Psalms 33:2; 57:9; 71:22; 81:3; 92:4; 108:3; 144:9; 150:3; Nehemiah 12:27; 1 Chronicles 13:8; 15:16, 20, 28; 16:5; 25:1, 6; 2 Chronicles 5:12; 9:11; 20:28; 29:25.

38. The lyre appears in Genesis 4:21; 31:27; 1 Samuel 10:5; 16:16, 23; 2 Samuel 6:5; 1 Kings 10:12; Isaiah 5:12; 16:11; 23:16; 24:8; 30:32; Ezekiel 26:13; Psalms 33:2; 43:4; 49:5; 57:9; 71:22; 81:3; 92:4; 98:5; 108:3; 137:2; 147:7; 149:3; 150:3; Job 21:12; 30:31; Nehemiah 12;27; 1 Chronicles 13:8; 15:16, 21; 15:28; 16:5; 25:1, 3, 6; 2 Chronicles 5:12; 9:11; 20:28; 29:25.

39. The tambourine appears in Genesis 31:27; Exodus 15:20; Judges 11:34; 1 Samuel 10:5; 18:6; 2 Samuel 6:5; Isaiah 5:12; 24:8; 30:32; Jeremiah 31:4; Psalms 81:3; 149:3; 150:4; Job 21:12; 1 Chronicles 13:8.

40. Dancing appears in Jeremiah 31:4, 13; Psalms 30:12; 149:3; 150:4; Lamentations 5:15.

41. Stringed instruments appear in Psalms 45:9; and 150:4.

42. The flute appears in Genesis 4:21; Psalms 150:4; 151 (11Q); Job 21:12; 30:31.

43. Cymbals appear in 2 Samuel 6:5; Psalm 150:5.

44. The shofar was blown as signal of an alarm or an attack, as warning of danger, to call warriors together, during the temple worship to signal a theophany, or when people should bow down, shout, or praise. It also announced festive occasions like New Moon, Full Moon, and New Year festivals; or when the Ark was transported to Jerusalem (2 Sm 6:15).

45. The harp was probably larger than the lyre (Sachs 1940:115-117) and had between three and ten strings (Oesterley 1939:591). The lyre had between four and eight strings (Clifford 2003:320).

46. Braun (2002:30) describes how the instrument has female and sexual symbolism and was popular in fertility rites.

47. The flute is described as an elegant instrument (Keel 1997:344) mostly used in secular activities (Anderson 1972:956).

48. Cymbals appear widely in the ancient Near East and are archaeologically well attested (Clifford 2003:320). This instrument developed over a period of time (Oesterley 1939:593). A smaller pair of cymbals might have been held vertically and struck from above and below; another type, a larger set, might have been clashed horizontally (Werner 1962:470). Different types were probably made from different material or metal (Sendrey & Norton 1964:130).

49. The term h('Wrt. is related to the cult and signify the outbreak of festive joy (Pss 42:5; 27:6; 89:16; Am 5:23), an extraordinary loud sound (Ex 32:17; Lm 2:7), which resounds far and wide (Ezr 3:13; Neh 12:43).

50. See Hartenstein (2007).

51. In the Chronistic History they are described as ~yIT;l.cim. (1 Chr 15:18; 16:5; 25:6; 2 Chr 5:12; 29:25; Ezr 3:10).

52. Mathys (2000:333-339) refers to an imaginären, idealen Gottesdienstes.

53. Hartenstein (2007:166-117) discusses this mediatory functi on of cultic music in the ancient Near East and the Old Testament. According to him the festive sounds and noises produced by cultic participants mediate contact with the god (Hartenstein 2007:123)

54. The same characteristic applies for praise in the final Hallel and in Book V.

55. Brueggemann (1991:63-92, 1995:194) describes a dialectical relationship between Psalms 1 and 150. In shaping a life of faith the Psalter sets the parameters of obedience (Ps 1) and praise (Ps 150) for the believer. Ultimately, according to Brueggemann, obedience has been overcome, transcended, and superseded in the unfettered yielding of psalm 150. He reckons that by Psalm 150 all the rigors obedience have all been put behind the praising community (Brueggemann 1995:195).

56. I hereby disagree with Brueggemann (1984:167) who describes Psalm 150 as the outcome of such a life under torah. Praise and adoration is not an outcome but a means, a way to concretise Torah in life. Brueggemanns notion that the Old Testament thus finally expects not obedience, but adoration is to my mind untanable. It is not an either or. Obedience is embedded in praise and adoration.

57. Gerstenberger (2001:460).

58. Kraus (1978:1149) notes that the psalm is wohl in späte Zeit anzusetzen. What this late time period means, is uncertain. Because it is the final psalm of the Psalter Gunkel (1926:623) attributes it to the allerletzte Zeit der Psalmendichtung in the post-exilic period. Van der Ploeg (1974:508) is convinced that the text was de laatste van allemaal in the 3rd BCE, because the text is fully preserved in 11QPsa with all its text variants.

59. Goldingay (2008:747) is a sole voice in dating the psalm pre-exilic. His motivation is the notion that the rams horn (instead of metal trumpet of the Chronicles), as well as the word for cymbals (ylec.l.c as used in 2 Sm 6:5) instead of the Chroniclers ~yIT;l.cim. (1 Chr 15:18; 16:5; 25:6; 2 Chr 5:12; 29:25; Ezr 3:10) is used in the psalm. The psalm was then later added to the final group of psalms, which were mostly postexilic.

60. See Anderson (1972:955).

61. Clifford (2003:319) uses the universal tendencies in the psalm, the poets insight into Psalm 2 and the psalms position as conclusion Psalter as reasons to opt for a dating in the Second Temple period.

62. Gerstenberger (2001:460) sets this possibility and notes that the setting was not a scribal or school office, but the assemblies of the faithful as place of liturgical activities.

63. This stance is taken by Seidel (1981:99, 1989:167), who provides the following motivations: the influence of Ezekiel on the psalm; the metal trumpet has not replaced the horn as signal instrument; Nehemiahs time offers a situation of rebuilding Jerusalem and the community. It is a time when poets and musicians claim a fresh role in the cult and society.

64. Terrien (2003:930) describes this period as a time of hope. It was a time when the rebuilding of Jerusalem, Judah and former exiles continues.

65. Allen (1983:323) uses the absence of the instruments in 150:4b as reason why the psalm should be dated after the composition of Chronicles. This argument seems to be an argumentum e silentio.

66. Oesterley (1939:588) mentions several musical instruments, which occur in the book of Daniel, but lack in Psalm 150. His conclusion is that the psalm was therefore composed prior to Daniel. Again, this argument tends to be an argumentio e silencio.