Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Kronos

versão On-line ISSN 2309-9585

versão impressa ISSN 0259-0190

Kronos vol.49 no.1 Cape Town 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2309-9585/2023/v49a9

ARTICLES

Public Culture, Sociality, and Listening to Jazz: Aural Memorialisation in the Time of COVID

Brett Pyper

University of the Witwatersrand. https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5615-6392

ABSTRACT

Taking its cue from two instances of hyper-local jazz sociability along one street in Mamelodi, five years apart, the focus of this article is on three instances of public memorialisation and, through them, on how listening can be socialised and enculturated. It is an exploration both of how sociality is co-constituted through listening, and of how listening is socially constructed, attending to how people become members of aural collectives in distinctive ways. It foregrounds how mostly working-class people living under conditions seldom of their own making continue, in the avowedly postapartheid context, at least partially to remake their worlds sonically, foregrounding the public cultures that they thereby aurally co-create as a notable cultural expression in and of themselves. Methodologically, it considers how recourse to non-elite aesthetics, viewed as repertoires of living, offer alternatives to the claims of both ethnographies and social histories 'from below' to present 'the word' of the community' in an authoritative sense.

Keywords: Jazz, listening, sociality, social history, ethnography.

Introduction: A jazz funeral for Bra Reggie

Friday the 25th of September 2020 was a taut spring day in Gauteng, the highveld province around Johannesburg long named for its subterranean riches. In a city long held to be emblematic of environmentally destructive resource extraction, a socially extractive1 migrant labour system, brutal social segregation, exploitative racial capitalism, post-industrial anomie and, especially in the post-apartheid period, xenophobia, Johannesburg has also, despite itself, witnessed deeply humane, countervailing struggles for redistribution, anti-materialist satyagraha, anti or arguably non-racial struggle, Pan-Africanism, justice, sustainability, hospitality and sociality. Historians and anthropologists have long argued that these factors have been central to this city's vital musicality and its broader creativity. Informing and informed by the enduring, if fractured, artistic energies of Jo'burg and its surrounds,2 today referred to as the Gauteng City Region, jazz has played an extraordinary historical and enduring role in the humanisation of these places. It is within such practices that the jazz listening sessions foregrounded in this article are sounded, though this city has its share of extractive musical histories to account for to be sure, being one of the oldest centres of the commercial recording industry in Africa. These counter-histories resonate beyond the inner city to and from the segregated peripheries of Johannesburg's surrounds. One such township, 65 km to the north-east, features prominently in this telling: Mamelodi outside the bureaucratic capital of Pretoria/Tshwane. I'm deliberate in locating Mamelodi within the cultural sphere of Johannesburg rather than its immediate municipal address because this helps to foreground the layered interaction of what I will call vernacular cosmopolitan practices in communities defined by the essentialised notions of race and ethnicity that apartheid inscribed onto the landscape, often through the forced removal of entire communities. As I elaborate be-low, Johannesburg's cosmopolitanism is not always of its own making, but has drawn multiple cultural and musical syncretisms into its orbit, even while many cultural confluences have also emerged within its terrain.

On a clear day, one can see the Thaba Mogale from Johannesburg (a mountain range rendered in Afrikaans as Magaliesberg) against which Mamelodi nestles further east, behind the horizon. It is often overlooked that Marabastad, to the immediate west of Pretoria's city centre, served as one of the incubators of the proto-cosmopolitan, internally variegated urban African cultures later associated with Johannesburg's townships and 'slumyards', decades before the emergence of its storied jazz scenes.3 As one of the sites to which Marabastad's black inhabitants were forcibly removed in the 1960s, Mamelodi has come to pride itself on avowedly being the only township in South Africa with its own unique style of jazz, malombo. Indeed, if it isn't apocryphal that its very name is to be heard as Ma-Melodi, Mother of Melody, Mamelodi seems to have been destined to make musical history. To centre Mamelodi in this account is, then, to make the point that the city region around Johannesburg remains a rich site in which to listen to for aural (and audio-visual)4 histories. As a major centre of African cultural production and diffusion, it is also a space of layered, scarcely told, vernacular sonic and musical practices of reception. This is, then, an account of what Paul Gilroy has called, referring to the circulation of gramophone records, the 'ties of affiliation and affect'5 that music can engender in relation to where people find themselves as well as how cultural practices and sensibilities can circulate.

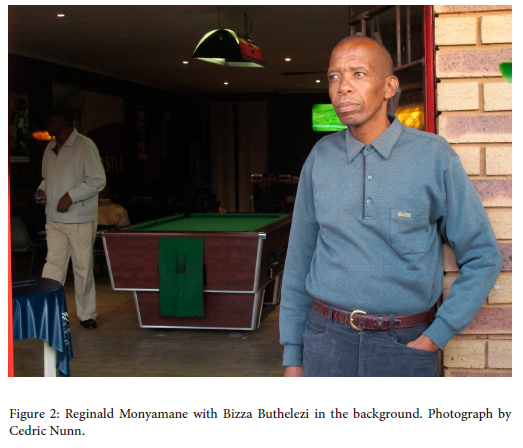

On that particular September spring morning, I got up early to try to clear some work that might prevent me from attending a funeral where I needed to pay my respects. Six months into the Covid-19 pandemic, proscriptions on public gathering under lockdown regulations had until recently resulted in what even successive states of emergency under apartheid hadn't: halting Gauteng's vibrant grassroots jazz gatherings, among whose proponents I'd been conducting research for over 15 years. But having come through the first wave of infections in July, some restrictions on assembling had just been lifted, aided by the arrival of the milder spring weather. And so it was fortunate that the untimely passing of Reginald Monyamane, one of the most beloved jazz dancers in Mamelodi, still in the prime of his life, took place at a time at which he could, befittingly, be sent off with a jazz funeral.

Bra Reggie had featured prominently in my PhD dissertation as a close associate of my teacher and friend, Bra Bizza Buthelezi. Despite some practitioners tracing the existence of so-called jazz stokvels or appreciation societies back to the days of wind up gramophones, the enduring fecundity and reach of these forms of grassroots jazz-related communal self-organising remain surprisingly overlooked and unheard as a significant aspect of South Africa's jazz heritage. Arguably a practice that preserved what remained of the celebrated mid-20th century jazz cultures associated with places like Sophiatown, Marabastad, District Six and many others, all forcibly removed under apartheid for the cultural 'mixing' they signalled, my research has documented an efflorescence of jazz appreciation activity in and beyond Mamelodi since the political transition of the 1990s that remains largely beneath the radar of South Africa's formal jazz industry.6 In this context, the socio-musical scene described here merits being viewed as a subculture in relation to more mainstream manifestations of public culture in post-apartheid South Africa.7 Like Bra Bizza, whose expertise as a veteran jazz DJ is widely recognised in this scene, adding a musical and social dimension to his working life as a shop steward in the transnational motor company from which he retired some years ago, Bra Reggie had also done factory work in an ancillary subsector of the motor industry. Though he was unemployed for most of the time that I knew him, his stature as an expressive dancer at the weekly and monthly jazz appreciation sessions he frequented had made him an obvious person to talk with about the meaning of this socio-musical practice.

In response to my asking what he admired in other diggers, exponents of the distinctive form of solo improvised dance cultivated among community-based jazz appreciation societies, Reggie was clear that he looked for something 'unique' and 'artistic':

When I go there [to the dancefloor], I think, I want to do something beautiful. Before I go, I listen to get the rhythm … when I go there, I'm listening very, very carefully. And I tell myself I'm going to satisfy this audience. And I go there with a beautiful mind. I say 'I'm going to do art for these guys'.8

Reggie's overtly aesthetic account of his practice referenced a non-elite, often precarious working-class social context that strikes me as a quintessential example of what an esteemed colleague, also recently departed, characterised as 'repertoires of living in and beyond the shadows of apartheid'. For Bhekizizwe Peterson, a literary scholar, filmmaker and former cultural activist with a lifelong concern with public culture, apartheid as a system of government in South Africa entailed not only specific economic and socio-political policies but, notably, de facto cultural policies that extended into the most fundamental elements of everyday life.9 Apartheid, Peterson also reminded us, was larger than South Africa and had become shorthand for referring to different kinds of discrimination, segregation and exploitation across the world,10 and could thus be used in the plural. Within that global context, Peterson's argument for the significance of the kind of aesthetic that I argue is articulated in the spaces in which Reggie moved was pointed:

One central aesthetic response to the demands of life and 'apartheids' is an abiding reliance on the complexities and politics of the quotidian ... The everyday longings for basic necessities and also for joy, love, beauty, community and democracy present some of the most politically affective and effective occasions that call into question the dominant ideas and networks of the state and other powerful national and international forces. Artists and citizens - through recourse to texts, modes and repertoires of living - have proffered alternative narratives, senses of self, memories and hopes for the future.11

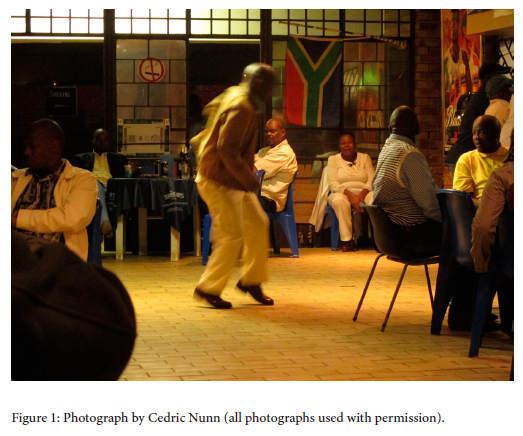

An apt example of the kinds of repertoires with which Peterson was concerned, there was a graceful abstraction to Reggie's dancing, often tinged with a dreaminess that comes through in a portrait the documentary photographer Cedric Nunn took when he accompanied me to a jazz listening session at Papa's Tavern in 2015,12 just down the block from Reggie's home in Madevu Street in the S&S section of Mamelodi East.

Reggie's stature among jazz appreciators was recognised with the greatest unspoken honour afforded diggers at the sessions he frequented: when he took to the floor, other dancers seldom stood by to follow him, and I often witnessed him being given unlimited time to unfurl his solos. Contemplatively gliding over the musical pulse while articulating his own subtle counter-rhythms, Reggie was afforded as much space and time as he needed to bring what he called a beautiful mind into kinetic expression. This despite the baldly utilitarian spaces provided by hard-floored municipal community halls under fluorescent lights, voluble local taverns, or cramped spaces in the repurposed yards of friends. Redefining such spaces as places to 'do art', but simultaneously as an integral expression of social relatedness, is in many ways what this article and the broader project of which it is a part are about. This art, point edly, embodies an aesthetic that doesn't look away from suffering and injustice, but looks from and through it.

In another photograph, Bra Lazba, an old friend on Mamelodi's jazz appreciation scene who had enlisted me to document the anniversary of his beloved Madleke Jazz Club back in December of 2005, stood in front of the tavern for his portrait, the last rays of autumn sunlight brushing his face.

To Lazba's right, Madevu Street extends into the middle distance, ending in a clump of trees that mark the grounds of the Balebogeng Higher Primary School. Kids were playing in the street or huddling together on the dusty grass verge that evening; pedestrians ambled or paused in conversation, a gogo (a literal or figurative grandmother) led a child by the hand. And a group in front of what appears to be a white umbrella or gazebo in the distance just about marks the spot where we would gather five years in the as yet unfathomable pandemic future for Reggie's funeral.

Arriving mid-morning on that September day, I saw that the street had been entirely taken over by the ceremony. By the time I arrived, the street was already full of parked cars alongside the usual foot traffic. Two marquee tents straddled the road, the one a sober white matching the cloth covers stretched over plastic chairs, the other striped rather festively in red and white, complementing the red carpet placed for diggers along the middle of the road between strips of green Astroturf. Chairs spilt out from under these canopies into the road itself, with passers-by witnessing the proceedings. Stalwarts of the local jazz scene and long-time close friends of Reggie, the Ngobeni family from Mathibestad, who would have driven for at least an hour-and-a-half from the north-west, had set up to perform as the Badimo ('Ancestors') Jazz Band, their live music alternating with CD selections played by local DJs.

Bizza had told me that, over the course of his long illness, Reggie had asked him that were 'something to happen', Bizza must play for him. I was touched to see that ultimate wish being fulfilled; in the couple of hours I was able to attend, Bizza, who is recognised as a veteran local jazz DJ, played tributes from, among others, Roy Campbell's Pyramids album and from Mingus Moves. Sealing the offering, he took to the floor (where the red carpet had by then been rolled up, apparently having proven less practical for dancing) to offer some footwork for his departed friend.

Taking its cue from these two instances of hyper-local jazz sociability along one street in Mamelodi, five years apart, my focus here is on how listening can be socialised and enculturated. It is an exploration both of how sociality is co-constituted through listening, and of how listening is socially constructed. I attend to how people become members of aural collectives in distinctive ways, extending beyond the mediation of spoken or written language. I foreground how mostly working-class people living under conditions seldom of their own making continue, in the avowedly postapartheid context, at least partially to remake their worlds sonically, whether using recorded music or through live musicking13 - a literal example of the repertoires of living that Peterson wrote about. And I foreground the public cultures that they thereby aurally co-create as a notable cultural expression in and of themselves, meaningfully framing and shaping the recorded and live performances they contain.

The focus of this article entails three instances of public memorialisation. It commences with Bra Reggie's funeral and moves to a concert just over a month later at the university where I am based, which led to the formation of a new collective that hosted a community concert billed in celebration of Reggie's life under pandemic conditions in December of 2020. I need to make the point upfront, though, that much as I have learned from the empathetic aspects of the participatory methodologies associated with the ethnographic disciplines as well as social history, this work does not intend to establish, and indeed renounces, representational authority. This position is hardly new; since at least the mid-1980s in anthropology and the 1990s in ethnomusicology, turns in the prevailing direction of scholarship characterised as critical, reflexive, and, to some, as post-modern have questioned the project of classic or modern ethnography and the kinds of authorship and expertise that it constructed.14 Similarly (and more pertinently, given the focus of the present journal), several leading South African proponents of public history have raised fundamental questions about the implicit claim of social histories 'from below' to present 'the word' of the community.15 in an authoritative sense. In the context of institutional imperatives to transform museums in post-apartheid South Africa, Leslie Witz has questioned the 'veneer of scientificity' underpinning the ways in which '[s]ocial history and its methodologies took root in new museums, as the conveyor of an authentic narrative and as a means to affirm communitiness'.16 Witz, citing an earlier critique by fellow UWC historian Nicky Rousseau of social history as locally practised,17 cautions historians and heritage practitioners who work with oral testimony to avoid regarding oral history, a method of course predicated on certain modes of listening, as 'a natural methodology of establishing validity' in favour of acknowledging the risks Rousseau had diagnosed of 'masking its own positionality and the extent to which it too is engaging in the construction of political subjects'.18

The implications of such questions have been profound for fields like ethnomusicology and African popular music studies, with which research of the kind reported on here tends to be associated globally. Writing as I do amidst the multiple contradictions of what has come to be referred to by some as post-postapartheid South Africa, a rhetorically doubled term connoting both continuity and rupture, I need, then, pointedly to pause and to defamiliarise the expectation that providing authoritative commentary should be my primary role. Since at least the 1980s, there have been fundamental changes in understandings of research relations, away from an earlier, often scientistic, aspiration towards objectivity in favour of more hermeneutic understandings of knowledge production.19 A related point that I wish to emphasise here is the extent to which jazz and popular music studies tended not to be studied in the field of ethnomusicology in South Africa, which was often sceptical of the status of newer forms of African music with commercial connotations in relation to its prime subject, 'traditional' African musicking. Rather, jazz studies in South Africa emerged in close dialogue with the burgeoning of social history. The first doctoral study of South African popular music was undertaken by a scholar originally from the United States, David Coplan, who, alongside his interviewees and the remarkable record left by the celebrated Drum magazine writers, extensively cited urban historiographers, contemporary social historians prominently among them, many of whom were associated with the pioneering History Workshop at Wits.20 This recourse to social history for scholars narrating the emergence of hybrid, often urban African musical practices, had become the norm by the time that Christopher Alan Waterman published his study of Nigerian Jùjú a decade later, whose subtitle is pertinently 'A Social History and Ethnography of an African Popular Music', signalling what has come to be a convention in studying musics of this type.21

Coplan's scholarly exposition of a world of urban African music and theatre (often not separated as distinct genres) included reviewing the antecedents of twentieth-century forms of musical sociability. This included the stokvel, a social institution dating back to the 'rotating cattle auctions' or 'stock fairs' of English settlers in the eastern Cape during the nineteenth century. In his review of social history sources, Coplan pointed out that 'Cape Africans brought the stokvel to Johannesburg, where the word came to refer to small rotating credit associations based on African principles of social and economic cooperation'. Coplan further observed that 'It is significant that a pattern of working-class social organisation in which traditional forms of reciprocity and redistribution were harmonized with the demands of the commercial economy should have taken its inspiration from European customs relating to the exchange of cattle.22

Both Coplan and Andrew Lukhele, founder-president of the National Stokvels Association of South Africa, located the historical emergence of the stokvel within a longer trajectory encompassing various adaptive modes of association and sociability created by members of black South African communities in response to colonial contact, missionisation and urbanisation. Among these diverse precedents of today's jazz stokvels were the burial societies whose origins Lukhele traces back to the Rand23 in the early 1930s.24 These and other elements came together in a highly consequential way, given my interests here, in the consolidation of the culturally hybrid urban African cultural matrix known by the term marabi, where residual and emergent modes of hybrid African urban sociability first converged with jazz by at least the second decade of the twentieth century. In the first monograph devoted to South Africa's 'jazzing' culture, Marabi Nights, Christopher Ballantine observes that marabi as a musical style was inseparably associated with 'the culture and economy of the illegal slumyard [urban ghetto] liquor dens' that accompanied urban African settlement in the context of South Africa's rapid industrial development.25 Coplan likewise locates the consolidation of stokvel organising and marabi culture among the 'rank and file' of urban Africans between the two world wars, also emphasising their imbrication with one another, as well as their cultural and economic utility.26 Offering a collective means of survival in the cash economy and deemed to embody traditional African values of communalism and cooperation, stokvels thus embody modes of association and sociability that bridge urban and rural, modern and traditional, capitalist and communitarian social roles and norms. Crucially, they lend themselves, over and above their economic rationale, to the enactment of social and cultural values, notably expressed through, and reciprocally shaped by, musical practice.

In elaborating on contemporary manifestations of the forms of musical sociability and sociality that continue to be practised on the foundations provided by these historical practices, I still stand by the argument I advanced in the abstract for my dissertation: that the significance of jazz can productively be understood from the perspective of listeners, complementing the necessary attention that has historically been afforded to the creators and performers of the music. Now with reference to Bra Reggie's funeral and the more recent collaborative experiments in public culture that have emerged from it, I describe the rich social life that has emerged around the collecting and sharing of jazz recordings by associations of listeners in this country. In these social contexts, a semi-public culture of listening (thus a subculture) has been created that is distinct from the formal jazz recording, broadcast and festival sectors, and extends across various social, cultural, linguistic and related boundaries to constitute a vibrant dimension of vernacular musical life. While collecting may be a global phenomenon, recordings can take on quite particular social lives in specific times and places, and the extension of consumer capitalism to places like South Africa does not always automatically involve the same kinds of possessive individualism that they do in other settings and might even serve as a catalyst for new forms of creativity. I argue, moreover, that what is casually referred to as 'the jazz public' is an internally variegated and often enduringly segregated constellation of scenes, several of which remain quite intimate and, indeed, beyond the view of any 'general public'. This work foregrounds how one specific dimension of jazz culture - the modes of sociability with which the music has become associated among its listening devotees and its underlying sociality - can assume decidedly local forms and resonances, becoming part of the country's jazz heritage in its own right and throwing into relief the potential breadth, range and contrasts in the ways that jazz writ large can be figured and recontextualised as it is localised around the world. I focus, then, on the significant role that jazz appreciation societies have played in creating culturally resonant grassroots social settings for this music, document the creativity with which they have done so, and consider the broader implications of their contribution to the musical elaboration of public space in contemporary South Africa.

From authoritative to aesthetic

In this context, then, I return to Bra Reggie's comments about attaining a 'beautiful mind' at jazz listening sessions. By his own account, what attaining such an expressive state meant to Reggie was first and foremost expressed in his embodied practice, what I call 'kinetic listening'.27 As I've already noted, he spoke about this in terms that were both personal creative offerings and in dialogical engagement with his audience of fellow jazz appreciators. Reggie was centring forms of knowing that reside in creative agency expressed in contexts of working-class sociability, in moving as an individual within a collective, in inhabiting music somatically, in an affective communal exchange in which one expresses shared as well as personal aesthetic exuberance.

Even as I de-emphasise the ethnographic and the documentary, I am also cautious of uncritically universalising the aesthetic. This is an especially loaded issue in the context of jazz and/or creative improvised music. I concur with Tumi Mogorosi in this respect, though he goes further than I do in rhetorically articulating a decolonial 'deaesthetic', consistently placing the 'aesthetic' under erasure.28 Recognising that the Kantian notion of the aesthetic is widely regarded as a colonising construct, as well as the contributions both of musicology in historicising the aesthetic and ethno-musicology in culturally relativising it, I argue that a distinctive jazz aesthetic was in play in Bra Reggie's dancing within the jazz subculture of which he was a part. This brings me back to Peterson's insights on the artistic in the context of the shadows of apartheid. In repertoires like the ones Reggie mastered and transmitted, Peterson discerns a 'resilience which, in itself, is significant' because cultural acts of resistance are 'further concretized and deepened by means of its expression through the aesthetic'. These are not, then, slavish internalisations of authorised Western aesthetics; they are profound articulations of struggle. They are what Peterson describes as palimpsestic practices that express 'an extraordinary will to live and love even in the most dire circumstances'.29 Moreover, for Peterson the aesthetic 'performs numerous intentions over and above its thematic preoccupations[: i]t is an archive and its modalities offer alternative modes of apprehension, knowledge and enjoyment'.30 Is there something specific, I have wondered, about music, and jazz specifically, that lends itself to understanding such processes of imaginative personal and collective self-refashioning in and beyond contemporary South Africa? This question provides an impetus to the ongoing work discussed here.

This reorientation toward a situated understanding of the aesthetic brings me to a further key theoretical coordinate. An aspect of the work of the of leading anthropologist of sound, Steven Feld, that has compelled my attention since I first read it as a graduate student is his articulation, in the early 1980s, of the potential affordances of recourse to the aesthetic in anthropology, not least in contexts of cultural inquiry where attempts are made at achieving mutual understanding across social and conceptual fault lines:

I cannot understand how one might study aesthetic systems without a concern for aesthetic intent in the analytic posture or a concern for how others perceive the analyst's own aesthetic sensibilities. Concentrating on value-free, objective measurements of aesthetic preferences has done little to move us toward a more ethnographically informed or humanly sensitive understanding of other visual, musical, poetic, and choreographic systems. Illuminating experience (and not only function) and co-aesthetic witnessing can only be accomplished honestly if ethnographers let themselves feel and be felt as emotionally involved people who have an openly nondetached attitude about that which they seek to understand.31

I take Feld's 'co-aesthetic witnessing' to offer a powerful framing to resist the social-scientific drift of the ethnographic, as well as to Rousseau's call to recognise the agency that lies in modes of representation that exceed the frame of the documentary, and to redirect it towards the knowing that is in practising.

Colleagues familiar with Feld's work will recognise that the title of the introduction above references the third film in his DVD trilogy Jazz Cosmopolitanism in Accra, 'A Por Por Funeral for Ashirifie'.32 That trilogy provided the title for his subsequent book, Jazz Cosmopolitanism in Accra: Five Musical Years in Ghana,33 which Feld describes as an exercise in 'listening to histories of listening'.34 Feld and I share a focus on non-elite African cosmopolitanisms 'from below'. With him, I argue that our work does not orient itself to 'the American "jazz age" of F. Scott Fitzgerald and George Gershwin', but rather to 'locally critical media of cosmopolitan contact and imagination, of bodily and spiritual mobility, of pleasure and performance' in contexts that are seldom foregrounded when jazz is storied, presented and marketed.35 As with the local Ghanaian funerary practices discussed there, the distinctive jazz subculture that gathered for Reggie's send-off is characterised by a 'sense of felt and imagined intimacy36 with transatlantic sounds, constellating around the music and, importantly, including its associated modes of sociability and its underlying sociality. The consideration that South Africa, too, hosts jazz funerary traditions might invite conjectures across wider horizons, registering both a shock of recognition and the imperative not to homogenise these practices in ahistorical and essentialist ways. The particular nature of township-based mutual aid societies associated with jazz in South Africa render them both distinct and resonant with broader transatlantic (and broader global) dynamics. And so I concur with Feld when he writes:

This is not a matter of taking sides in debates about 'retentions' or the meaning of diaspora. No stretch of call-and-response imagination is necessary to connect the long black Atlantic histories of parades, community participation, mobile drum and horn ensembles, social welfare societies, dancing in the streets, and the need to celebrate life while mourning death. At the same time, there is no need to indulge in simple or unilinear origin stories; there is plenty of distinctive long and recent history in the emergence of both por por37 and New Orleans jazz funerals, no matter what commonalities they share at the surface.38

By adding Reggie's jazz funeral in Mamelodi and others like it to the global map of jazz-oriented funerary practices across and beyond the Atlantic,39 this study brings me into dialogue with Feld's work on jazz cosmopolitanism in Accra, together with the voices of his interlocutors there.40 Among many shared interests, I here emphasise one that is present in passing in his account of Nelson Ashirifie Mensah's funeral in Accra in March of 2008 which I wish to foreground as a keyword for the present study: its public character. Much of Feld's analysis of por por funerals in Accra's La district centre on the reproduction of reputation. In foregrounding its social reproduction, he invokes the notion of the public, twice: 'Whether the name [of the person being buried] is spoken or sung … it is a shout-out into the streets of public culture, the insertion of, indeed, insistence on repetition as resonance, a way to keep the memorial in public presence.'41 And indeed, Bra Reggie's funeral in Mamelodi was perhaps most poignant for publicly affirming his reputation as a Ndukuman, a jazz person, as the street in which he lived came to a standstill to envelop his grieving household with jazz sociability, underscoring the centrality of relatedness, of sociality, to the memorial practices I witnessed that day.

The process of critically revisiting my doctoral project has reaffirmed my professional arts practice as an aspect of my scholarship and, reciprocally, my scholarship as central to my arts practice. It has also led me towards a far more interdisciplinary positioning, at the intersection, inter alia, of applied ethnomusicology, public culture and critical heritage studies (each an interdisciplinary field in its own right). It has also involved a commitment to taking as much time as it takes for the relationships at the centre of this research to be ready for the kind of scrutiny that 'going public' entails. My work continues to be animated by a Feldian acoustemological emphasis on the affective dimensions of how publics are musically, sonically, and/or aurally constituted. It also engages meta-disciplinary critique in revisiting what kinds of research paradigms are appropriate, particularly in postcolonial contexts. At the same time, it has moved beyond addressing academic audiences only. As I have revised and expanded upon the exercise in ethnographic writing that I submitted for a PhD in ethnomusicology, I have returned to my initial and abiding concern with the musical construction of public culture(s) and the public construction of musical subjectivities. In the process, my research became more than a study of public culture; it came to be advanced through the collaborative co-creation of public events as an exercise in public scholarship. My understanding of this kind of work is animated by taking up the challenge posed by Ivan Karp in his reflection on public scholarship as a vocation.42 Reflecting my critical transition from presumed outsider status and the academic neutrality propounded in classical models of research, towards engaged, and thus implicated, scholarly praxis,43 I have become accountable to my research co-subjects as publics in ways that are highly consequential for advancing a deor counter-colonial project.

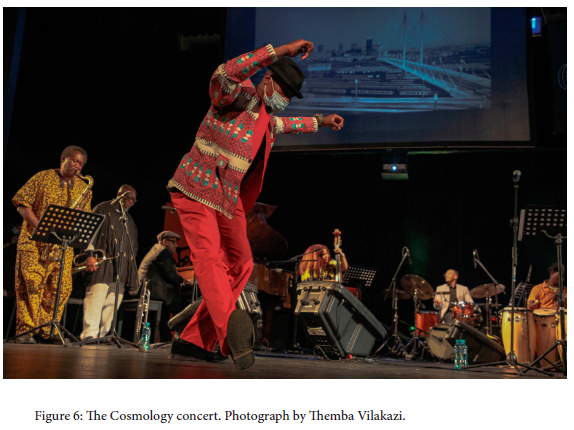

The public phase of this work is recounted in detail elsewhere44 but for my purposes here, I will briefly recount a series of developments in the closing months of 2020 that followed Bra Reggie's funeral that bring the narrative with which I opened full circle. Just five weeks after his send-off, on 30 October 2020, we hosted a concert at the Wits Theatre that followed a diga workshop and a colloquium on jazz cosmopolitanism in Africa. In the absence of public events yet being permitted under lockdown regulations, our intention was to livestream the performance online to Prof. Feld and musical interlocutors in Accra, especially the Anyaa Arts Quartet. The performance had been conceived as a musical response to some of the themes explored in the Anyaa recordings, produced during the course of the collaborations that yielded the Jazz Cosmopolitanism in Accra albums, films and monograph. Relieved of the pressure to deliver a paying audience, I was able to invite members of Mamelodi's jazz appreciation community as a socially distanced 'in-studio' audience for the online broadcast. Though unscripted, virtually from the very beginning of the performance, a steady stream of diggers left the auditorium and climbed the stairs onto the apron of the stage, between the musicians and the audience, dancing one by one by turns, as is the custom at community appreciation sessions when the mood is right.

The university setting ended up freeing certain parameters typical of more commercial jazz festivals and venues and demonstrated that alternative approaches to programming jazz were possible, accommodating publics that seldom formally interact. Such considerations were further affirmed a week after the concert when a few students and a member of the performing group45 met at Bra Bizza's house, west of Mamelodi, for a debrief with our community partners who had been in the audience. The outcome of the meeting was a decision to continue and build upon the collaborative potential that the concert had demonstrated. Mamelodi-based practitioners present wanted to have jazz appreciation culture presented in wider public settings like Wits and didn't want this to be a once-off event. Recognising that the concert had brought together not only community-based and academic jazz researchers and teachers, but also stakeholders who did not always closely collaborate within townships settings, the group decided to form a new structure to coordinate activities and advance jazz appreciation culture through and beyond the prevailing pandemic. Inspired by the way in which the colloquium and concert referenced Feld's collaborations in Accra, the members present that day decided to call this new entity the Cosmopolitan Collective.

The extended public humanities and practice-centred project that has ensued has become a unique, experimental, still developing collaboration between interconnected communities of practice from Mamelodi and its surrounds: jazz collectors, DJs, appreciators, dancers, musicians, heritage activists, music educators and researchers within and beyond township settings. Its mission has become to work together to sustain community-based jazz gatherings, expression and research, including innovating new ways of presenting jazz appreciation culture, in communities and also in more mainstream public and academic venues. These engagements have become an intensely participatory collaboration, on as well as off campus, and have involved some undergraduate students, several postgraduate researchers, colleagues from various arts and humanities disciplines at Wits as well as practitioners from around Mamelodi, many of whom have become co-organisers and co-researchers. Based on principles of reciprocity, mutuality, transparency and collaboration, overlaying the hospitality and conviviality central to the culture, the project has come to centre on intergenerational knowledge interactions within and beyond the community.

The new collective's activities started with a concert in Mamelodi the very next month, on the public holiday that marks the start of the year-end festival season in South Africa. Six local bands were presented in a community hall, at an event billed to be in memory of Bra Reggie Monyamane.

The work of the Cosmopolitan Collective in organising this concert and several others subsequently took up a question that I had posed several years previously regarding what memorialising South Africa's fallen music heroes might mean and what the most appropriate ways would be for doing so.46 Responding to civil society-led initiatives to erect statues to jazz icons (something that was deemed to be missing at the time that has subsequently been partially addressed), I had argued that those who have forged South African jazz idioms would more effectively be memorialised through the pursuit of an ongoing collective musical legacy than they could ever be in any proposed memorial statue. This argument centred on foregrounding memorialisation as a verb (like diga dancing) rather than a noun (like a statue), recognising and amplifying the capacity of places and practices of memory to be experiential, processual, ritualistic and performative. In line with that earlier position, I can imagine no more appropriate a way to celebrate and affirm the life of Bra Reggie than of being able to reanimate with music and dance a space in which he had performed at countless jazz appreciation sessions, capping 2020, a year in which both he and the venue had fallen silent.

Conclusion

Jazz listening sessions of the kind I have described briefly here provide, at least in part, a matrix in which various historical modes of sociability and struggle are imprinted. The contemporary practices which manifested at Reggie's funeral as well as the community concert to memorialise him resonate with much twentieth-century urban black South African cultural memory. It is not fanciful, I believe, to discern these social auras haunting at least some of the ways in which jazz appreciation societies have sustained vernacular jazz culture, largely below the threshold of official public culture, across the late apartheid era and into the current dispensation.

In his revisiting of his research since the late 1970s in the second edition of In Township Tonight!, David Coplan reported that whereas stokvels had, as an institution, still been vigorous in the late 1970s, their associated activity had become 'rather more diffuse, individualized and single-event oriented in recent years'.47 Yet jazz appreciation societies remain a significant feature of social life within many communities in contemporary South Africa, certainly in and around Mamelodi. When the late Reggie's friend Bra Bizza and fellow workers at factories adjacent to Mamelodi formalised their recreational jazz listening sessions during the course of the 1980s, they were drawing on what was already a long historical association between music referred to as jazz and cultural and economic practices that have characterised much working-class and associated black life throughout the process of urbanisation. They were also driving what, from their vantage point, was an efflorescence in public-facing jazz appreciation activity in the democratic era. Recognising the historicity of ways of listening offers a way, then, to position listening in relation to practices of social memory, which is to say as aural history. It therefore constitutes a distinct local opportunity to practise what Feld suggestively calls 'listening to histories of listening'.48

1 On the socially extractive nature of resource extraction around Johannesburg, see G. Trangos and K. Bobbins, 'Gold Mining Exploits and the Legacies of Johannesburg's Mining Landscapes', Scenario 05: Extraction, Fall 2015.

2 See M. Holland, 'Artists and Makers Are Doubling Down on Johannesburg', New York Times, 30 December 2022.

3 So much so, that an unresolved debate endures as to whether the bedrock of South African jazz and much of its popular music, the style of improvised neotraditional music known as marabi, as foundational an influence on subsequent musical styles as the blues have been for American popular music, had its roots in, and drew its name from, Marabastad. For classic discussions of Marabi culture (though not in Marabastad), see Eddie Koch's early work (E. Koch, '"Without Visible Means of Subsistence": Slumyard Culture in Johannesburg, 1918-1940' in B. Bozzoli (ed.) Town and Countryside in the Transvaal (Johannesburg: Ravan Press,1983) and E Koch, 'Doornfontein and its African Working Class, 1914-1935: A Study of Popular Culture in Johannesburg' (MA Dissertation, University of the Witwatersrand, 1983). Also, Christopher Ballantine's authoritative account of early South African jazz history, Marabi Nights: Jazz, 'Race' and Society in Early Apartheid South Africa (2nd edition) (Pietermaritzburg: University of KwaZulu-Natal Press, 2012, 1993). For historical studies of Marabastad, see M. Friedman, 'A History of Africans in Pretoria with special reference to Marabastad, 1902-1923' (MA dissertation, University of South Africa, 1994), J. F. C. Clarke, A Glimpse into Marabastad (Pretoria: Leopardstone Private Press, 2008) and I. Matshaya, 'Cultural Nostalgia: A Commemoration of Marabi' (MArch research report, University of Pretoria, 2019).

4 My focus in this article is less on the visual component of the audio-visual than on its sonic aspects, despite the inclusion of Cedric Nunn's resonant photographs, as explained below.

5 P. Gilroy, The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double Consciousness (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1993), 16. [ Links ]

6 B. Pyper, '"You can't listen alone": Jazz, listening and sociality in a transitioning South Africa' (PhD dissertation, New York University, 2014). [ Links ]

7 Subcultures have been a staple of Cultural Studies since Dick Hebdige's classic study Subculture: The Meaning of Style (London: Routledge, 1979). While Hebdige focused on Britain's postwar youth styles as symbolic forms of resistance, subsequent studies have applied the notion across a range of contexts and musical idioms. Within Music Studies, Mark Slobin's influential Subcultural Sounds: Micromusics of the West (Hanover & London: Wesleyan University Press, 1993) theorises the specifically musical aspects of subcultures in relation to notions of 'superculture' and 'interculture'. Another pertinent theoretical point of reference in thinking about subcultures is Michael Warner's notion of 'counterpublics', where a or the public is construed (among other things) as 'a space of discourse organized by nothing other than discourse itself ' and where a counterpublic marks itself off against a dominant one. See M. Warner, 'Publics and Counterpublics', Quarterly Journal of Speech, 88, 4, 2002, 413 & 424.

8 Pyper, 'You can't listen alone', 159.

9 B. Peterson, 'First call for papers, panels and round tables: 40th Annual Conference of the African Literature Association (ALA)', April 9-13, 2013.

10 In this respect, Peterson reinforces an irony that Rob Nixon had pointed out: the extent to which apartheid, contrary to its very essence, generated significant global solidarity between multiple struggles against racism. See M. Nixon, Homelands, Harlem and Hollywood: South African Culture and the World Beyond (New York: Routledge, 1994).

11 The sections quoted from Peterson are from the first call for papers for the 40th Annual Conference of the African Literature Association (ALA), which took place at Wits on April 9-13, 2014, and his introduction to the special issue of the Journal Of The African Literature Association, 10, 1, 2016, 1-2, that emerged from it (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/21674736.2016.1199337).

12 Cedric Nunn accompanied me to a jazz session well into the research process reported on here, after completion of my PhD but before the emergence of a new phase of collaborative research during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. I am grateful to an anonymous peer reviewer for pointing out the potential for the photographs included here to be more than illustrative, and potentially to serve as photographs to which, following Tina M. Campt's evocative injunction, one might 'listen'. See T. M. Campt, Listening to Images (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2017). I intend to pursue this in future writing.

13 Christopher Small's holistic theorisation of musicking, conceived as a verb, is presented in his book, Musicking: The Meanings of Performance and Listening (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 1998).

14 The reflexive turn in anthropology, widely associated with the 1986 collection of essays in J. Clifford and G. E. Marcus (eds.), Writing Culture, The Poetics and Politics of Ethnography (Berkeley and Los Angeles, California: University of California Press, 1986), was taken up in ethnomusicology in the ensuing decade with the volume of G. F. Barz and T. J. Cooley (eds.), Shadows in the Field: New Perspectives for Fieldwork in Ethnomusicology (Oxford & New York: Oxford University Press, 1997). A second edition was published in 2008.

15 L. Witz, 'Archives, Museums and Autobiography: Reflections on Write Your Own History (with a Small Detour to the University of Bophuthatswana)', Southern Journal for Contemporary History, 44, 2, 2019, 21.

16 Witz, 'Archives, Museums and Autobiography', 22-23.

17 N. Rousseau, 'Popular History in South Africa in the 1980s: The Politics of Production' (MA dissertation, University of the Western Cape, 1994).

18 Rousseau, 'Popular History', 71-3, cited in Witz, 'Archives, Museums and Autobiography', 22.

19 I am grateful to Cory Kratz for our helpful exchanges, in discussing drafts of this material, which emphasised the need both to acknowledge the often career-long commitments of senior scholars, over the past 50 years in some instances, to critically remaking ethnography, and to the pertinence of the ways in which ongoing postcolonial contributions have added to and reoriented this work.

20 I am grateful to Leslie Witz for reminding me of the pertinence of the contribution of social historians to the emergence of studies of urban South African poplar musics. Deborah James made this point in a review of the tendency for accounts of urban South African popular musics initially either concentrating on the technical or the social aspects of music rather than considering their interaction. See D. James, 'Musical form and social history: Research perspectives on black South African music', Radical History Review, 46, 4, 7, 1990, 309-319. Social histories informing Coplan's account include texts by Eddie Koch, C. C. Saunders and Tim Couzens.

21 Waterman explicitly mentions the publication of D. Coplan, In Township Tonight! Three Centuries of South African Black City Music and Theatre (Johannesburg: Ravan Press, 1985) which was based on his PhD dissertation, as a social history and exemplar. See C. A. Waterman, Jùjú: A Social History and Ethnography of an African Popular Music (Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 1990), 6.

22 Coplan, In Township Tonight!, 123.

23 'The Rand' is colloquial shorthand for the Witwatersrand ('white waters ridge' in Afrikaans), the geological formation along which Johannesburg is located.

24 A. K. Lukhele, Stokvels in South Africa: Informal Saving Schemes by Blacks for the Black Community (Johannesburg: Amagi Books, 1990), 5. [ Links ]

25 Ballantine, Marabi Nights, 5 (emphasis added).

26 D. Coplan, In Township Tonight! Three Centuries of South African Black City Music and Theatre (2nd edition) (Johannesburg: Jacana, 2007), 125.

27 Pyper, 'You can't listen alone', 157.

28 I. Molale (Tumi Mogorosi), 'Deaesthetic: A performance of and from a space of dislocation, a critical analysis of the violent aesthetic imprisonment(s) in/of knowledge production' (MAFA dissertation, University of the Witwatersrand, 2020).

29 B. Peterson, 'Introduction' to Special Issue on 'Texts, Modes and Repertoires of Living In and Beyond the Shadows of Apartheid', Journal of the African Literature Association, 10, 1, 2016, 1.

30 Peterson, 'Introduction'.

31 S. Feld, Sound and Sentiment: Birds, Weeping, Poetics, and Song in Kaluli Expression (2nd edition) (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1990), emphasis added.

32 S. Feld, 'A Por Por Funeral for Ashirifie,' Jazz Cosmopolitanism in Accra, DVD series (2009).

33 S. Feld, Jazz Cosmopolitanism in Accra: Five Musical Years in Ghana (Durham, NC & London: Duke University Press, 2012). [ Links ]

34 Feld's discussion of Ashirifie's funeral appears in the penultimate chapter.

35 Feld, Jazz Cosmopolitanism in Accra, 47.

36 Ibid., 189.

37 The onomatopoeic term por por is the name of both the honk horn instrument and the music invented for and with it by Accra's La Drivers Union. See Feld, Jazz Cosmopolitanism in Accra, 161.

38 Ibid., 284-5, emphasis added.

39 Feld's work on funerary practices in Accra was pre-dated by his ground-breaking account of funerary practices in Papua New Guinea. See Feld 1982/1990.

40 I was fortunate to take classes with Prof. Feld towards the end of his tenure at New York University while I was a graduate student at the turn of this century.

41 Feld, Jazz Cosmopolitanism in Accra, 196.

42 I. Karp, 'Public scholarship as a vocation', Arts and Humanities in Higher Education, 11, 2012, 286.

43 S. Araújo, 'From Neutrality to Praxis: The Shifting Politics of Ethnomusicology in the Contemporary World', Musicological Annual, XLIV/1, 2008, 13-30.

44 My forthcoming book in progress revisits the research undertaken for my PhD in relation to the collaborative phase of work arising from the formation of the Cosmopolitan Collective.

45 Participants from Wits who attended apart from myself were the conveyor of our festival study group, Oladele Ayorinde, and two of its members, Christine Msibi and Simphiwe Mthembu. Simphiwe had also served as a production assistant with the listening/musicking group and was the one who initially proposed the title 'Cosmology'. Also present was percussionist and dance practitioner Thabo Rapoo.

46 B. Pyper, 'Memorialising Kippie: On Representing the Intangible in South Africa's Jazz Heritage' (Paper presented at the South African Museums Association Conference, 12 June 2006).

47 Coplan, In Township Tonight!, 123.

48 Feld, Jazz Cosmopolitanism in Accra.