Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Kronos

On-line version ISSN 2309-9585

Print version ISSN 0259-0190

Kronos vol.49 n.1 Cape Town 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2309-9585/2023/v49a2

ARTICLES

Shared Reflections Offered by Listening to Johnny Mbizo Dyani's Born Under the Heat

Sinazo MtshemlaI; Ben VergheseII

INAHECS, University of Fort Hare https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4057-5637

IIDepartment of History, University of the Western Cape https://orcid.org/0009-0000-4458-400X

ABSTRACT

Originally written as a lecture-presentation for the 2021 South African Society for Research in Music (SASRIM) conference, this text shares our ongoing collaborative study of Born Under the Heat, an album by Johnny Mbizo Dyani. Our research tracks the record(ings) to mark potential pathways for thinking about networks of sociality and solidarity that underpin the production of such politicised cultural work, as well as how we listen to and/or may read it. We trace how the album, recorded in 1983, was born out of festival-gatherings in Lagos, Gaborone and Amsterdam as well as Dyani's memories/remembering of home (from Duncan Village to Dorkay House, perhaps) when exiled in Scandinavia. By reiterating literal and symbolic modes of travel which Born Under the Heat took, as an object and as a concept/project, we aim to explore multiple routes and forms archival, repatriation and restitution projects continue to find in the postapartheid present.

Keywords: anti-Apartheid, solidarity, liberation music, repatriation.

Introduction

On 18 November 1983, a Friday, Johnny Mbizo Dyani gathered an octet at a recording studio in Stockholm (Sweden). The following year this session was released as a vinyl record under the title Born Under the Heat.1 In this paper we (Sinazo and Ben) invite readers to listen closely with us to selections from the Born Under the Heat album and share in our ongoing study of Johnny Dyani's music and movements. As we will express, by way of its cover design, explicitly politicised song titles and liner notes, then subsequent placement through a process of 'repatriation' to the liberation archive at the National Heritage Cultural Studies Centre (NAHECS) at the University of Fort Hare, Born Under the Heat has afforded us endless openings for inquiries.2Since July 2020, the two of us have been in irregular conversation from where we live in East London and Cape Town respectively. A presentation for the 2021 SASRIM conference marked the first time we sat together in person to listen to Dyani's music, think with him, and offer readings/listenings. Through this act of ongoing sharing we keep/kept in mind Katherine McKittrick's writing on sharing and struggle.3Sharing is something one does with others; it is therefore important to reflect for a little bit longer on what it might mean to gather together.4 Gathering requires creating space for it to happen. This paper therefore has largely benefitted from such gathering/s of ideas, thoughts at multiple sites, and at different times. Physical gatherings were made impossible by the intensity of the COVID-19 pandemic. This led to the SASRIM conference changing its composition from in-person, where we were meant to gather at the Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University in Gqeberha, to only virtual attendance. We gathered our ideas in meetings via video calls and email exchanges; here/there we listened together, shared ideas and were later joined by two mentors who were in different time zones, one being in Johannesburg and one in York (England).5 Putting together our presentation, we were never quick to settle on one pathway, our ideas floating like the symbols on the album cover of Born Under the Heat. The flag, the hat, the footprints, the bridge floating, disconnected from their anchors; hat with no head, the bridge with no bass, feet with no shoes ... The decision made by Ben to come to East London for us to gather together physically to listen to other presentations and deliver ours allowed us even momentarily to suspend floating and to bask in the 'ambient flood of genial warmth'.6

Our research tracks the record(ings) and walks pathways for thinking about networks of sociality and solidarity that underpin Dyani's work as a 'politically committed artist'.7 Although we stray into the terrain of biography writing, this paper is not a biography of Dyani per se; rather it iterates certain aspects of his complexity and creative socio-political connections through a particular period. Born Under the Heat surfaces in a chapter of Johnny Dyani's life when he is based for the second time in Sweden.8 It is three years on since he last played with fellow Blue Notes Louis Moholo and Dudu Pukwana (each of whom are in London, England) along with Chris McGregor (relocated to Lot-et-Garonne, France).9 Mongezi Feza and Nik Moyake have passed on. Tellingly this is the period after Dyani participated at Festac '77, the Second World Black and African Festival of Arts and Culture (held in Lagos, Nigeria, in early 1977) followed by an African National Congress (ANC) organised tour in Zambia in June 1977.10 It is also after the two 1982 culture and resistance festivals, first in Gaborone (Botswana) and then in Amsterdam (Netherlands). Dyani was one of only a few people to have attended both seminal gatherings in Lagos and Gaborone.11 We read Born Under the Heat as being born directly out of these politicised border-crossing encounters and Dyani's active support for the ANC. It is an expression of his commitment to the struggle, in which he activates words voiced by Keorapetse Kgositsile in a keynote address at the Gaborone symposium.12

We speculate too that, having lived away from ekhaya for almost twenty years, Born Under the Heat was born out of Dyani's memories and distant re-membering of home.13 From the two locations touted as where he was born and raised - Duncan Village (East London) or Zeleni (outside King William's Town) - through to Dorkay House (in Johannesburg) and other sites that formed a circuit of musical conviviality that he devoted formative years to prior to his departure from South Africa with the Blue Notes when still a teenager.14

Three enduring tropes associated with cultural production from South African artists in exile surface in Born Under the Heat, through direct references made to the climate, to people and to places.15 As we track literal and symbolic modes of travel the recording took, as an object as well as a concept/project, we aim to unpack these tropes while exploring multiple routes and forms which archival, repatriation and restitution projects continue to find in the postapartheid present. We employ the tools and experience that we can collectively bring to this duet - archival work, DJ scholarship, our readings of black critical thought and historiography.16 In this paper's earlier version, we produced a pre-recorded presentation, which included visual and musical components alongside our recorded voice turning our writing into audio. This was a challenging process! Reversioning texts echoes a habit of Johnny Dyani, who would often play the same song at different moments, with different musicians playing different instruments. Song titles for what appear to be the same composition would also change.17 Much like a song being known by different titles, this paper takes into account rearrangements, repeats, resoundings, crossings, as necessary in the rewriting of this presentation turned paper.

We now pause to listen to the music of Johnny Dyani and encourage readers to also listen to the suggested playlist.

[PLAY] SONG ONE: 'Winnie Mandela' (Born Under the Heat, track one)

Imaginary Home(land)s and Sisebenzela ekhaya (working for home)

In Sweden, one of Dyani's makeshift homes, it was decided to title the opening song of Born Under the Heat 'Winnie Mandela'. Short and punchy, this dramatic introduction to the record was recorded at a time when Ma Winnie was banished from her home by the Apartheid state and six years into her stay in the town now renamed after her and previously called Brandfort (in the Orange Free State).18 As far as we have learnt, Dyani never met Ma Winnie, however, writing of her unplanned encounter with the legendary matriarch in 1982, Ellen Kuzwayo noted:

in 1987 by Cadillac Records, the song goes by a different title - 'Crossroads'. In the latter version there is a different group of musicians playing together as Johnny Dyani's The Witchdoctor's Son band. Here Peter 'Shimmy' Radise and Dyani are the only two musicians playing in both albums. The inclusion of different musicians and other instruments such as the whistle and congo drums produce a crossover, and experiments with different styles and genres. 'Crossroads' invites the listeners to dance, while 'Namibia' has a more melancholic feel, produced by the trumpet and alto sax and the bass conversing. Johnny Mbizo Dyani, 'Witchdoctor's Son', Together (Cadillac Records, 1987), http://www.teatermango.se/dyanitogether/index.htm (accessed on 12 June 2022).

I was gladly surprised and impressed by her very pleasant disposition, her calmness and complete composure. Her charm, her singing laughter, her unchanging face and her ever-present dignity are those of the Winnie Nomzamo of the 1950s.19

There is an audio cassette tape found at NAHECS of an interview between an unnamed Swedish journalist and Ma Winnie Mandela about her experiences of being at Brandfort. In the recording we hear voices of other people talking and shouting in the background, which suggests a house full of people, something that defies the banishment order that sought to isolate Winnie. She speaks about the impossibility of life being banned, where she says 'life was made so difficult that it was impossible to exist'.20 She relays this impossibility of being taken to court every week because she 'violated' the banning order at every instance. 'I was charged for any type of pettiness they could think of.' Later, the journalist suggests: 'Now you have done the best of the situation I would say?' To which Winnie responds:

Well we had to prove ourselves to them, the racist regime that we were not gonna be broken by that sort of thing and wherever we are, there are our people and the struggle goes on. It doesn't matter what part of our country they dump us in, as long as there are oppressed masses of this land for whom we have sacrificed ourselves, the struggle will go on and that is how we have made this a home. People are living here, therefore the struggle goes on here too. 21

We get to hear this sense of homeliness in the audio recording through the sounds of people chattering, children laughing and playing (one even speaks into the recorder as she is engaged by the journalist to say something) - there are also chickens' squawking. Such a bustling soundscape also occurs in the fourth song of Born Under the Heat, whereby Dyani's 'Lament for Crossroads' is peppered with noises of children playing, as well farmyard animals: cows mooing, the neighs of horses and chickens clucking. Produced in Sweden, 10 000 kilometres away from South Africa, Dyani along with producer Leif Collin and recording engineer Gösta Konnebäck sonically created an image of, as the album liner notes state:

'Only the apartheid government could banish someone to a place where others live not as prisoners but as ordinary black subjects. You think to yourself - not for the first time - that racists, in addition to being cruel, are stupid. They are ineffectual because their aversion to black people, their profound inability to see black people as fully human, makes them blind to logic. They have sent a fiery, charming, intelligent woman, a leader of the ANC and a seasoned fighter, to a place full of poor and oppressed black people, and they expect this will have no politicising effect. They think Winnie Mandela will serve out her sentence in silence, and that the community around her will, like stones, remain mute and unaffected by her presence. This is not how it works. Life in Brandfort is hard but you feel a profound sense of responsibility. You are a woman who has lived an unconventional life, and you are both yourself but also Nelson's wife. You are an ambassador of sorts - an exiled dignitary living in her own home.' S. Msimang, The Resurrection of Winnie Mandela (Johannesburg & Cape Town: Jonathan Ball Publishers, 2018), 90-91.

[P]eople being moved off their land to homelands, with bicycles, chickens, horses, cows and their children; everyone crying and being chased and moved on by South African police.22

Ma Winnie too is surrounded by a hub of activity. Yet in the taped interview her voice is filled with calmness and composure as accurately reflected in Ellen Kuzwayo's description of her encounter with Winnie. Her 'singing laughter' is infectious.

There is much said about the trope of the woman who is waiting, as often represented in wives of political figures who have been incarcerated, such as Winnie Mandela. Akujobi picks this trope up in her reading of Njabulo Ndebeles The Cry for Winnie Mandela. She suggests that the helplessness and hopelessness that come with the act of waiting is projected in the author's 'slow-moving, somnolent pace of the story'.23 In contrast, Dyani's song 'Winnie Mandela' is not slow-moving but shifts the tempo, between quick and slower rhythms. It gives us another sense of a waiting, that is militant, waiting for the right time to strike rather than a patient, passive waiting. It is channelling an energising sounding. The horns produce an intensification but there is also a slow and measured response particularly in the solo moments. A calmness and complete composure? Yet with a singing laughter. Through all the pain, the struggle, the suffering, there is room for a singing laughter that Kuzwayo picks up.

Dyani departed South Africa in 1964 along with fellow members of the Blue Notes. In his lifetime, the closest he came to physically returning home was for the Gaborone festival in 1982.24 After he died in late 1986, on stage in Berlin (Germany), his body was brought home to South Africa. This posthumous physical return was a repatriation marked with ceremonies to acknowledge its significance. We shall expand on other forms of repatriation later in this text. At Dyani's funeral, a speaker (introduced as Julius) spoke about his encounters with Dyani, from them being in primary school together in East London to meeting years later when they were both in exile. Julius spoke profoundly about Dyani's broad notions of home:

When he was in Botswana he said to me, 'Homeboy, I am celebrating the fact that for the first time in more than 20 years I am back in the soil of Africa. I am in communion with my spirits.' He said 'I am having a ritual at Jonas Gwangwa's place. In other words, some kind of dinner.' He said 'please come and represent my folks because you're the only one from my part of that world.'25

Elsewhere, writing in the same year as the Botswana Culture and Resistance festival, in an essay titled 'Imaginary Homelands', Salman Rushdie speaks to shared experiences:

[E]xiles or emigrants or expatriates, are haunted by an urge to look back, even at the risk of being mutated into pillars of salt. But if we do look back [... ] we will not be capable of reclaiming precisely the thing that was lost: that we will, in short, create fictions, not actual cities or villages, but invisible ones, imaginary homelands ...26

In tracing the stories, the sonic fictions, that Dyani bestowed to us, song (and album) titles, liner notes and a small array of interviews narrate the messages he wished to communicate to listeners, along with his efforts to reclaim and share that which was lost from being away from home. When discussing the idea of working for home, Dyani was not alone in articulating such a motive. Keorapetse Kgositsile describes this motive as reflecting and articulating life itself:

To be fired with the spirit of freedom, to be determined to fight and destroy that tyranny, to usher a new chapter of life where there is peace, progress and happiness - this we see as our mission, our duty, our ultimate responsibility. 27

When Sinazo interviewed Pinise Saul at her home in Mdantsane, East London, Ma Pinise spoke about her journey to exile having left with Ipi Ntombi and how she began to work with Julian Bahula as part of the band Jabula. According to Ma Pinise, Jabula was 'near to the struggle' and that is why she wanted to be part of it. She articulated that 'bendifuna le isebenzeli'khaya, which translates into English as 'I wanted to be that one that worked for home ...' In recalling the cultural work that working for home entailed, it included the use of songs sung and the remembering of events that figured in the memory of Ma Pinise and were never recorded.28 There is a song that Ma Pinise sings with the lyrics: 'Soweto, my heart is in Soweto, my home is in Soweto, Soweto my love, Soweto my home ...'29 In a documentary film titled Jabula: A Band in Exile, band member saxophonist Mike Mathome Rose introduces the other members of Jabula while they were performing at a club in London. While the song 'Soweto' is being sung in the background by Pinise as the main vocalist and the other members, Rose starts by introducing Pinise as coming from the city Port Elizabeth, rather than East London.30 Through these moments geographical boundaries are collapsed, with Ma Pinise singing for Soweto as a home, as love, as symbolic of resistance and struggle, while also spoken about as an individual relocated as being from Port Elizabeth rather than her home of East London.

Through the different notions of home, a clear message stayed consistent. In Ma Pinise's words: 'every musician osukekhaya bonke they were working for the struggle'.31

And, Dyani: 'As a South African I don't care how great I could be; if I'm not doing it for my people, I'm zero.'32

[PLAY] SONG TWO: 'Wish You Sunshine' (Born Under the Heat, track two)

Wish(ing) You Sunshine - ligcakamele (bask in it)

The second track on Born Under the Heat is a rendition of Dyani's composition 'Wish You Sunshine'. It is the sole solo piano song on the album.33 This version is the fifth recording of the composition we have found performed and/or recorded by Dyani either solo or with different groups. The earliest dated recording features on the Song for Biko album from 1978, where the liner notes stipulate: 'Wish You Sunshine is, according to Dyani, "about my people. I'm trying to keep up my people's spirits at a time when there's been so much unrest."'34 Less than two months after the Song for Biko recording (in Copenhagen?), at the 1978 Willisau festival, Dyani vocalised his sentiment singing as he played piano: 'I wish you all sunshine, all of the time. [...] I wish you all someday you'll understand the pain my people has suffered.'35

Dyani diagnosed Apartheid 'as a disease that has bewitched South Africa'.36Imagining his role as that of a social doctor for diseases, he explained, 'I am affected by different climates, different seasons ... I play within the weather.'37 Christina Sharpe writes, 'The weather necessitates changeability and improvisation; it is the atmospheric condition of time and place; it produces new ecologies.'38 In the poetic turned literary metaphor, 'a dry white season, Mongane Wally Serote and then André Brink applied a description for the Apartheid time and place they survived.39 With 'Wish You Sunshine' and Born Under the Heat, Dyani's titles continue such utterances of the climate or weather operating as a barometer for a country or nation's mood. In as much as Dyani's idea of playing within the weather charts a listening that reflects movements, changes and continuities (be they his or those of a country or compatriots), it also speaks to the unexpected and destructive aspects of literal and figurative climates - the new ecologies Sharpe eludes to. This also speaks to Sharpe's description of weather as the 'totality of our environments', a totality that is importantly anti-black. This is what she names as an impossible possibility. Sharpe makes her own diagnosis that anti-blackness is as pervasive as climate. By recognising Apartheid as a social disease, she alludes to it being an atmospheric condition of time and place.

To play within the weather is to perhaps recognise the enormous often overpowering and overwhelming task of what it took and continues to take to deal with Apartheid. It has to involve constant change and improvisation. For Dyani the improvisation means that through the totalitarianism of the Apartheid regime there is still room not to be entirely consumed by it, for one to feel something different. When interviewed, Dyani has added that musicians, poets and teachers in South Africa were treated as leaders in society and had the responsibility to reflect the 'mood of the nation'.40

The almost ten minute-long version of 'Wish You Sunshine' on Born Under the Heat is instrumental. As well as the earlier live from Willisau recording, another version also has lyrics, recorded in March 1982 with Pinise Saul (for the BBC Radio 3 Jazz In Britain show). The addition and exclusion of lyrics reflect those changes in moods. As we listened together, Dyani's use of the sustain pedal stood out. Picturing his right foot working, other ideas of sustaining surfaced. In the album's liner notes, Dyani dedicates this particular 'Wish You Sunshine' to three pianists: Gideon Nxumalo, Pat Matshikiza, and Shakes Mgudlwa, with each compatriot receiving a movement. This act of dedication appears to be a way for Dyani to sustain memories of pianists who have influenced him.41 These elders or peers of Dyani are pianists he came into contact with prior to leaving South Africa, for instance at Dorkay House or the Cold Castle Jazz Festivals.42 In the song's multiple hues/shades, we are invited to bask in the afterglow of the good times Dyani had with three brilliant peers.

[PLAY] SONG THREE: 'Portrait of Tete Mbambisa' (Born Under the Heat, track three)

Sites for sociality and black diasporic musicking43

Growing up together in the Eastern Cape, Tete Mbambisa and Saul were childhood friends/associates of Dyani; together they contributed to a circuit of cultural production countering the Apartheid system prior to departure overseas.44 Once away from home, Dyani befriended and collaborated with a range of artists/cultural workers/activists. One of whom is the painter Harvey Cropper. Cropper relocated from New York (USA) to Scandinavia in the 1960s along with fellow US-born black artists, Sam Middleton and Clifford Jackson. First in Bornholm (Denmark) and in Stockholm, Cropper became an elder artist for Dyani as well as Lefifi Tladi to spend time and study with. Dyani, Tladi and Cropper's paths converged in Lagos at Festac '77, with Cropper heading a group of black artists from (or based in) Sweden, and Dyani invited separately by the ANC.45 Through encounters with Thabo Mbeki, Lindiwe Mabuza, Keorapetse Kgositsile and comrades, Festac appears to be the site where Dyani was recruited by the ANC to represent the liberation movement as a cultural worker/ambassador.46 Picturing these interdisciplinary (or anti-disciplinary?) artists intermingling, influencing each other and collaborating at festivals and places across the world evokes Laura Harris' writing on the 'aesthetic sociality of blackness' as well as Fred Moten and Stefano Harney on (black) study.47 This speaks to what Tor Sellström describes as 'an explosion of anti-Apartheid initiatives and activities' within the Nordic countries in the mid-1980s.48 This explosion saw the increasing involvement of the broader Swedish anti-Apartheid movement, and the growing consensus between the state and civil society which saw the intensification of solidarity campaigns that also included those within the cultural sphere.49 Paying attention to cultural forms of solidarity created during Apartheid Bethlehem, Dalamba and Phalafala allow for a critique of the idea of South Africa's isolationism and instead brings to the foreground South African writers as people who were also in 'dialogue with internationalist trajectories emerging out of the political ferment of decolonization'.50 Bhekizizwe Peterson also insightfully writes how foundational writers and scholars in exile, such as Es'kia Mphahlele and Noni Jabavu:

[W]ere enmeshed in the discrete but interlinked spheres of culture, history and politics and cognisant of the limits and possibilities of national, continental, Third World and international networks and solidarities in the struggles against racial capitalism and imperialism.51

We motivate that there is much scholarship/study to continue to disseminate that illuminates the internationalist tracks of southern African musicians and artists. If we look at the Born Under the Heat album art we see an artwork by Harvey Cropper.52

In an interview with Lars Rasmussen, Cropper reveals the painting is titled 'Johnny's Hat', then further narrates:

[T]hat hat, the straw hat, that's the hat he [Dyani] bought during the FESTAC in Nigeria. I was doing a series of hats, and that's the one I painted of his, and they used it for the album cover, even though it was not painted for the album. I don't know where that painting is now. Maybe Gilbert [Matthews] has it or maybe I have it.53

In the painting, the hat floats over the bridge of a double bass which, detached from the rest of the instrument, stands above a black, green and gold/yellow flag. The flag, laid out like a beach towel, is recognisable as being the colours of the ANC. Footprints creep in from the left of the frame. The hat that appears in the painting/ album cover resembles the one worn by Dyani on the album titled Mbizo.

Released in 1982 on the SteepleChase label, Mbizo was recorded in February 1981 at the Third Eye Centre in Glasgow (Scotland). The photo of Dyani wearing his hat was made by Nils Winther who ran SteepleChase records from Copenhagen, the Danish capital city, in the 1970s to 1980s. Winther regularly recorded concerts at the club Jazzhus Montmartre.54 The Montmartre club is a recurring site of significance for Dyani and fellow South African musicians. It was there where the Blue Notes had a Copenhagen residency in 1965 and the experience is described in a letter by Chris McGregor to his wife/partner:

Maxine, you would love the club. No failure here, sometimes there's a queue outside at 3am! It's a little tourist-ridden (recommended off-beat attraction in all the guide-books) but this atmosphere is so much more preferable than that other thing we know so well. The surprising paradox is here as Dollar [Brand] said - the people are noisy but they listen and are appreciative -they enjoy getting right into the music.55

Further along the Baltic Sea coastline in Stockholm, another live music venue provided a site for sociality and black study - the Fasching Club, which hosted Dyani on numerous occasions. One memorable performance took place in October 1980 with Dyani's regular bandmates Gilbert Matthews drumming and Ed Epstein playing alto saxophone. They were joined by Bheki Mseleku on piano. Lefifi Tladi recounts that night:

[O]ne important event at Fasching [...] I remember it was so terrible, because I started crying like ten devils chasing one Christian, and Gilbert was there, and Johnny was trying to cool it, and I wished this could be happening in Africa, because it was elating - whew! I never cried that much in my entire life.56

According to Leif Collin, Born Under the Heat was planned to initially be a record of Dyani with Swedish musicians. However the actual session came about, of the band of eight musicians, only three were Swedes: Ulf Adâker (trumpet), Krister Andersson (tenor sax) and Thomas Östergren (electric bass).57 In a photo taken by Collin at the AV-Elektronik studio, we see four South African musicians together: drummer Gilbert Matthews, the elder saxophonist Peter Shimi Radise, Mosa (Jonas) Gwangwa, trombone in hand, and Dyani. These four bandmates were on stage together almost a year earlier as part of the Anti-Apartheid Riot Squad. There in Amsterdam, a follow up culture and resistance festival to the Gaborone gathering, Hugh Masekela introduced everyone in the super-group, welcoming Peter Shimi Radise to solo by saying he was: 'somebody myself and Jonas were likely to see when we were still learning in the 1940s and 50s. One of our great teachers from Sophiatown.58

Whereas Radise and Matthews had become based in Sweden, Jonas Gwangwa had not. The 'South African dance troupe' that Leif Collin mentions as the reason Gwangwa is in Sweden is in fact the Amandla Cultural Ensemble, the ANC's Cultural Unit commonly referred to as simply Amandla. Documents found at NAHECS corroborate this. A programme for Amandla's 1983 itinerary in Stockholm signed (and typed?) by Lindiwe Mabuza does not mention Born Under the Heat directly, however, it outlines that the week of the recording was a busy one, including a gala at Kulturhuset on 18 November and three concerts over the weekend.59 It also emphasises how this was a period when there was a fundraising drive for the Solomon Mahlangu Freedom College (SOMAFCO), a school in Morogoro (Tanzania) built on land given by President Nyerere on behalf of the Tanzanian government and people. Students from SOMAFCO attended Festac '77 as well as the 1982 Gaborone and Amsterdam festivals where we believe Dyani met with comrades. Ma Lindiwe attests to a connection Dyani built with these students. She recalls that:

Already at FESTAC I was drawn to Johnny who had a quite soft demeanour, a warm personality, kind, considerate and generous. His spirit immediately drew him to the young students from SOMAFCO and I know that he formed a strong bond with one of them, giving most of his clothes when they parted at the end of FESTAC.60

We therefore presume these events to have been on Dyani's mind when he titled the first song of side B, 'The Boys From SOMAFCO'. The legacies of SOMAFCO merit close discussion, analysis that would include processing Edwin T. Smith's research, listening to an untold number of students from SOMAFCO trained to be archivists (and hired in other key education roles post-1994), as well as to Terry Bell's reflections of the ill treatment that young people suffered.61 However, this is work for another paper. For now we return to Dyani's music and move to questions of what it means to return home.

[PLAY] SONG FOUR: 'The Boys From SOMAFCO' (Born Under the Heat, track five)

Repatriation

Repatriation in its basic definition means the physical movement of people and things from a foreign place to a place of origin. When Minister of Arts and Culture, Pallo Jordan, responded enthusiastically to the African Skies project which saw to the handing over of The Dutch Anti-Apartheid Movement's collection of audio-visual materials to the National Film and Video Sound Archive.62 Jordan had expressed such a gesture as 'encapsulating the spirit of solidarity from comrades and colleagues in the Netherlands.63 Furthermore it expressed the seriousness of the issue of the restitution of cultural property.64

Dyani's Born Under the Heat is one such item that has been repatriated.65 However, unlike videos or other vinyl LPs that form part of the audiovisual collection of the ANC with provenance clearly indicated, with Born Under the Heat there is no such metadata prompting us to speculate as to how it travelled home. We suspect that vinyl copies of the album were transported with the repatriated anti-Apartheid posters and other materials in 2013 brought by the International Institute for Social History (IISH) in Amsterdam.66 The main recipients of these materials were ANC archives first deposited at Luthuli House and later transferred to NAHECS, the South African History Archives (SAHA) and the Nelson Mandela Centre of Memory.67

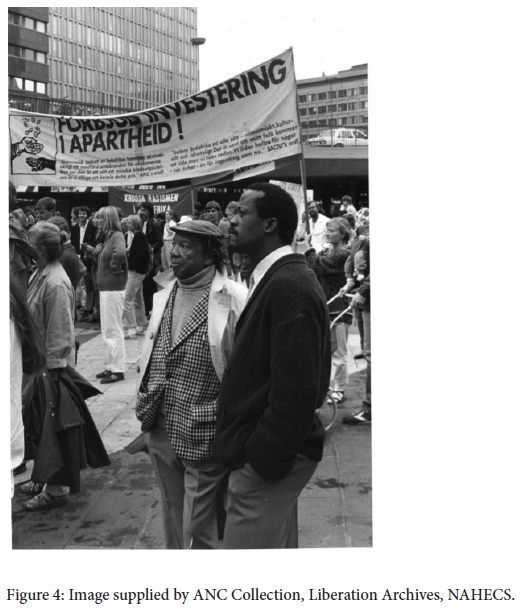

Among materials at NAHECS in the ANC Swedish Mission collection is a photographic album sent to Lindiwe Mabuza by Anne Nielsen from Tvind dated 8 November 1983. The album features photographs from different events, mostly rallies, some in colour and others in black and white. In two photographs Johnny Dyani can be recognised. In one photo we see Dyani from the vantage point of the photographer's wide shot to the right of the frame in conversation with someone. Lindiwe Mabuza appears close by. In this image the photographer does not seem to give any specific focus on any individuals; Dyani could easily be lost in the sea of people. In contrast, a second photo shows Dyani, hands in the pockets of his knitted jacket, next to an unidentified man. An anti-apartheid banner is being held behind them. This photographic aesthetic is a minor style in South African liberation archives, where portraits of individual political leaders posing are the order of the day; comrades, with all their complexities and contradictions, turned into images in the service of the struggle.

Zonke Majodina, who has written extensively about exiles, the repatriation of exiles and the dilemmas of return, focuses on the psychosocial aspects that are oftentimes neglected. She argues that there is something important that is lost when the focus of repatriation is limited only to the 'logistics' rather than human dimension.68

The experience of return as Majodina puts it becomes 'depersonalised to undifferentiated "masses" or "flows"'.69

While Majodina's study attends to the repatriation of human beings, a similar argument can also be made about records. Born Under the Heat's transitory and uncertain state can be understood to be a result of the treatment of records of less prominent status. Archives can be places of 'depersonalised' and 'undifferentiated masses and flows' but if we look closer we do find the human dimension that Majodina is alluding to. Lindiwe Mabuza writes about such a personal encounter she had with Dyani before his death:

Johnny always informed me when he was to go on tour. I knew he was due to go to Germany. He invited me to attend one or two of the shows, but I couldn't. So this day Johnny called saying it was important that we met the very next day because he had something urgent to consult me about. There was no way I couldn't find time. This was a comrade. The next day Johnny arrived at the ANC office, no.29, Gamla Brogatan, he presented two beautiful young ladies: his daughters Hassanah and Thandi. He promised that he would later introduce me to his son. That moment, I realised what a responsible parent he was, 'Sis Lindiwe,' he said, 'I just want my children to know where they belong. I am not just a black South African musician, my home is the ANC.'70

By introducing his children to Ma Lindiwe Mabuza, who was the Chief Representative of the ANC but equally an important artist and scholar herself, allows us to get to the personal side of politics. In the days following Dyani's passing, Mabuza wrote a poem in honour of her fallen comrade. Titled 'BIG BASSMAN MBIZO DYANI' the type written page begins: 'They lie still now / Those black magic hands / Only their nimble trembles / Inside our swollen heart / Vibrates .. .'71

Another poetic tribute to Dyani came from Kgositsile with the memorable stanza: 'Your bass / Johnny pins nothing down. Your bass / rides on wave or height or rock / or depth or crevice of sound / to bathe us in music .'72 Bra Willie Kgositsile's tribute 'For Johnny Dyani' was preceded in the form of a song that brings the vinyl version of Born Under the Heat to a close: 'Song for the Workers' which Dyani dedicates to his comrade-mentor-friend. In the keynote address at the Culture and Resistance Symposium that was held in Gaborone in 1982, Kgositsile is quoted saying this about the artist:

Our artists have over the years struggled along with the people, sensitized to and expressing the feelings, sufferings, hopes, failures and our struggle for national liberation. The past few years have been attempts by artists, both at home and in exile, to organize themselves into collectives, identifying themselves with the struggle and fashioning ways of making their talents functional in their communities and to the struggling masses of the people as a whole.73

What happens in life, Kgositsile adds, finds expression in artistic creativity. So the art of mobilising workers to strike and taking up arms to fight are all expressions of the same thing which is about the pursuit of freedom.

Dyani echoes these statements where he says that:

There's no art or music, paintings, or human beings without a tradition. Those who don't have a tradition, oh my goodness, like walking without a hat on [laughs] ... so the music I've heard, I have to keep it with me wherever I'm going, the tradition, it has to be with me whenever I'm going. So that's what's giving me my life.74

In the liner notes of Born Under the Heat Knox describes 'Song for the Workers' as a kwela piece.75 Kwela, we suggest, is a floating/loose term that draws on traditions of South African music genres. 'Song for the Workers' signals us to these longstanding traditions that are unaccounted for, but make a person. As Dyani notes about kwela (even as he is rejecting the term as commercial), it was something he was brought up on and used to play in the street with this homemade paraffin guitar. He says, 'We just went there and played because we felt good about it. Kwela means hop in! Just go ahead join! To conscientize can also be to simply encourage others to "Stand up and do something! Let's dance'?76

[PLAY] SONG FIVE: 'Song for the Workers' (Born Under the Heat, track seven)

In closing

To discerning listeners, including Lefifi Tladi, Born Under the Heat is not Dyani's most brilliant or compelling music.77 It is a markedly different sound to his avant-garde work with the Blue Notes, or Don Cherry or Abdullah Ibrahim. Nonetheless, it is a project that brings together his dynamic magnetism for musicians to co-create and agitate with - all the while illustrating him as a politically committed artist (or cultural worker). In the decades after the album's creation some copies have made it home, and spending time with them, listening and tracking the(ir) movement/s allows us to fuse transitory experiences in relation to the permanence that the archive (public or private) promises.

After Johnny Dyani's death and his body being repatriated home to East London, his brother Fikile Dyani wrote to the ANC offices in Stockholm expressing gratitude for the arrangements that were made. He then made an appeal that 'the bass instrument he [Dyani] used in his lifetime be brought home with him'.78 We look again at the depiction of the bridge of a bass in the Born Under the Heat album cover and suggest it can represent the fragmentary nature of the archive. We are also able to appreciate acts of repatriation as never being final. Music-making as knowledge production allows for our understanding of Africa, diaspora and exile to spread beyond a continent's boundaries.

Recalling the words of Edward Said, chronicling the creativity of '[e]xiles, emigres, refugees, and expatriates uprooted from their lands . „' remains an ongoing task.79 Our choice to work as a duo on this presentation, to collaborate, is a deliberate pushing back at single-authorship and to continue to try to learn from the collaboration that Dyani and comrades were committed to. We also take to heart the words of Ma Pinise of what it might mean to ukusebenzelikhaya; there is much working for home(s) still to do.80

Sonically, imaginary homelands that Dyani implies he was born in, play out through the samples of animals, children's voices and rumbling thunder heard in the songs 'Lament for Crossroads' and 'The Boys from SOMAFCO'. Track titles from the album allude to significant people and places. Crossroads serves as a placeholder name for the numerous sites of forced removals. The song 'Namibia' signals the hope of liberation movements (in this case SWAPO) reclaiming power and independent governance. As we close, we suggest listening to a song that was added to the 1996 CD reissue of Born Under the Heat, from a live performance at Lund's Museum of Art in May 1985. With this bonus track, we are reminded of Pallo Jordan's dedication to Dyani: 'he clearly understood that freedom, for the artist and in the arts, is inextricably bound up with freedom in society'.81

[PLAY] SONG SIX: 'Let My People Get Some Freedom (Born Under the Heat, CD only bonus track nine)

1 Leif Collin, who part-owned Dragon Records, the label who released the album, and is credited as co-producer of Born Under the Heat, recalled how, 'We applied to the Swedish National Council for Cultural Affairs and received financial support to go ahead with a recording with Johnny and a group of Swedish musicians. The recording [...] had been late in getting started because Johnny wanted the participation of a trombonist (Mosa Gwangwa) who was in Stockholm at that time playing with, if my memory is correct, a South African dance troupe. The recording began at 10pm and continued until 3 the next morning' L. Collin, 'Johnny Dyani: "Our Struggle Needs Support." A portrait and interview by Leif Collin' in L. Rasmussen (ed), Mbizo: A Book About Johnny Dyani. (Copenhagen: The Booktrader, 2003), 242.

2 The Born Under the Heat album is located at NAHECS, which has become alongside Mayibuye and other institutions a symbolic and physical home of liberation. This archive is considered a home more than a house for the records that were created in the course of fighting the end of the apartheid system in South Africa as liberation archives have been defined.

3 Katherine McKittrick writes: 'Sharing can be uneasy and terrifying, but our stories of black worlds and black ways of being can, in part, breach the heavy weight of dispossession and loss. Our shared stories of black worlds and black ways of being breach the heavy weight of dispossession and loss because these narratives (songs, poems, conversations, theories, debates, memories, arts, prompts, curiosities) are embedded with all sorts of liberatory clues and resistances [...]. Sharing, therefore, is not understood as an act of disclosure but instead signals collaboration and collaborative ways to enact and engender struggle.' K. McKittrick, Dear Science and Other Stories (Durham & London: Duke University Press, 2021), 7. [ Links ]

4 Johnny Dyani has an album by his band Witchdoctor's Son titled Together. The first track is also titled 'Together' and the chorus urges that: 'Everybody should everybody should be together (together)' See Johnny Mbizo Dyani 'Witchdoctor's Son', Together (London: Cadillac Records, 1986).

5 The authors would like to express our gratitude for the generosity we received in the form of intellectual inputs and advice we received from our mentors Dr Lindelwa Dalamba and Dr Jonathan Eato who were assigned to us by SASRIM.

6 Here we are taking from the definition of basking as an action that is to: '… expose oneself to or disport oneself in, an ambient flood of genial warmth ...". See https://0-www.oed.com.wam.seals.ac.za/view/Entry/15965?rskey=FlcREv&result=3#eid (accessed 5 July 2022). This is of course also taking on Dyani's title 'Wish you Sunshine' and what it might mean to bask in the sunshine at the University of Fort Hare in the East London campus where Ben and Sinazo gathered for our presentation.

7 P. Jordan, 'Johnny Dyani: A Portrait', Rixaka: Cultural Journal of the ANC, 4, 1988, 8.

8 Dyani first lived in Sweden from 1969-1971. Lars Rasmussen offers a detailed biography of Dyani titled 'When man and bass become one'. In this account he mentions briefly in one line that Dyani moved to Sweden in 1969. See Rasmussen, Mbizo, 18.

9 In Berlin at a concert called the Total Music Meeting 1980.

10 Rasmussen, Mbizo, 149.

11 Additional known figures include Keorapetse Kgositsile, Lindiwe Mabuza, Lefifi Tladi, Mongane Wally Serote, Jonas Gwangwa, Lucky Ranku, and Mandla Langa.

12 K. Kgositsile, 'Culture and Resistance in South Africa [Keynote address]', MEDU Art Ensemble Newsletter, 5, 1 1983, 25. [ Links ]

13 There are complications and mystery over Dyani's date and place of birth. See Rasmussen, Mbizo, 9.

14 Patricia Achieng Opondo tracked some of these aspects to where she positions Dyani like others in exile, as an artist drawing on 'memory of Africa, roots, traditions, ancestral ways'. She suggests that these articulate themselves as political statements for artists in the diaspora, and Dyani fashioned this to form part of his political, personal and musical identities. She also makes the argument that the positionality of being in exile opens artists to new contexts to experiment with different expressions that draw on their South African identities 'self-consciously styled in performance', thus offering possibilities for what Opondo calls 'reconnections'. See P. A. Opondo, 'African music in global diasporic discourse: Identity explorations of South African artists' in E. Akrofi, M. Smit and S. Thorsen (eds) Music and Identity Transformation and Negotiation (Stellenbosch: African Sun Media, 2007), 275. [ Links ]

15 The places named in song titles are 'Crossroads' and 'Namibia'.

16 Lynnée Denise points out 'four cultural practices' with which she defines DJ Scholarship as being built from: '[F]irst is chasing samples; the second is digging through the crates [for vinyl records]; the third is studying album cover art review; and the fourth is reading liner notes.' HKW (Haus der Kulturen der Welt), 'Lynnée Denise: Sampling the Archive', 2020, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cSKRIUa_CME (accessed 20 June 2020).

17 One example of this is the song titled 'Namibia' in the Born Under the Heat album. In a different album Together, released

18 Decades later, Sisonke Msimang makes the point that banishment is a metaphor for the 'collective condition of black people'. She writes, 'The conditions in which you live in this place of banishment are desolate and bare - but no more than the conditions of your neighbours, who have committed no crime and who are not serving any penal sentence. Your banishment is thus a metaphor: it speaks to the banishment of all black South Africans; your sentence is a mere reflection of the collective condition of black people. Being in Brandfort is, for you, a constant reminder of the sickness of [your] society in that [you] are virtually in prison even in [your] country. Those who are outside prison walls are simply in a bigger prison'

19 E. Kuzwayo, Call Me Woman (Johannesburg: Raven Press, 1985), 247.

20 ANC Audiovisual archive, NAHECS, Cassette tape Collection, Winnie Mandela to unnamed journalist, undated.

21 Ibid..

22 Gösta Konnebäck was also a technician for a number of anti-apartheid recordings, including: Freedom Yes! Apartheid No! by South Africa Freedom Singers and Jabula (1979), Amandla's First Tour Live album (recorded in 1980, released in 1983).

23 R. Akujobi, 'Waiting and the Legacy of Apartheid: Constructing the Family in Njabulo Ndebele's The Cry of Winnie Mandela, Matatu Journal for African Culture & Society, 48, 2016, 29. [ Links ]

24 Rasmussen, Mbizo, 23.

25 Footage of funeral service of Johnny Dyani, Mdantsane,16 November 1986.

26 S. Rushdie, 'Imaginary Homelands, London Review of Books, 4, 18, 7 October 1982.

27 Kgositsile,'Culture and Resistance in South Africa,' 26-27.

28 Here Ma Pinise speaks about the albums that they did, one which was the Jabula in Amsterdam album which was banned in South Africa. This album forms part of the music and oral history collection kept at the Mayibuye archives at the University of the Western Cape. She also recalls the work they were doing as Jabula of touring Europe as part of the efforts of raising funds for the ANC. Ma Pinise remembers an event that was organised by poet, writer and activist Dennis Brutus alongside Howard University in America, She recalls a standoff that happened between students and the police where the students did not allow the police to come inside the stadium where the festival was being held. This event Ma Pinise recalls as having been a peaceful counter to the propaganda that was pushed that 'blood would be spilt'. This also speaks to the solidarity between the black Americans and South Africans. Personal Communication between Sinazo Mtshemla and Pinise Saul, Mdantsane, East London, 2016.

29 Ibid..

30 J. B. Bussemaker, 'Jabula in Exile', 1980, 1070_159, ANC digital archive, ancarchive.org.za.

31 Ibid..

32 J. Litweller, 'He's home again', Chicago Tribune, 14 December 1986, https://www.chicagotribune.com/news/ct-xpm-1986-12-14-8604030447-story.html (accessed 14 August 2021).

33 Gilbert Matthews: 'Why he sometimes preferred the piano, it was because a lot of cats didn't hear what he was saying on the bass and then he would go to the piano. I understood him, we were from the same country, the same tribe. There were never any problems about understanding what the other one was saying, musically.', in Rasmussen, Mbizo, 119.

34 C. Sheridan, liner notes for Johnny Dyani Quartet, Song for Biko, SteepleChase Records, 1979.

35 Johnny Mbizo Dyani, African bass solo concert: Willisau Jazz Festival 1978, sing a song fighter Records, 2018.

36 G. Gehman, 'Witchdoctor's Son to work its musical magic in L.V, The Morning Call, 27 September 1986, https://www.mcaH.com/news/mc-xpm-1986-09-27-2532493-story.html (accessed 12 August 2021).

37 Ibid..

38 C. Sharpe, In the Wake: On Blackness and Being (Durham & London: Duke UP, 2016), 106. [ Links ]

39 M. W. Serote, 'For Don M - Banned' in Tsetlo (Johannesburg: A. D. Donker, 1974), 58; A. Brink, A Dry White Season (London: Star, 1980).

40 Gehman, 'Witchdoctor's Son to work its musical magic'.

41 We are yet to practice a close enough comparative listening to music from Nxumalo, Matshikiza, and Shakes Mgudlwa to suggest that Dyani makes/channels musical references to them in this version of 'Wish You Sunshine'. We welcome comments from anyone who can hear this.

42 Basil Breakey's photographs beautifully transport us to days at Dorkay House. See: B. Breakey & S. Gordon, Beyond the Blues: Township Jazz in the '60s and '70s (Cape Town & Johannesburg: David Philip, 1997). [ Links ]

43 We give thanks to an anonymous peer reviewer for the phrase 'diasporic musicking'.

44 Tete Mbambisa was a former bandmate of Dyani in The Four Yanks. Photos of Pinise Saul by Basil Breakey show her to have been at Dorkay House when Dyani and fellow Blue Notes frequented the cultural hub in 1963.

45 Festac '77 registration cards show Cropper was also joined by artists including Rudy Smith, a steelpan player and composer who having relocated from Trinidad to Sweden went on to play with Dyani, including on the album Afrika (SteepleChase, 1984).

46 Chimurenga, Festac: 2nd World Black and African Festival of Arts and Culture: Nigeria, Lagos, Kaduna, 15th January - 12th February 1977 (London: Afterall Books & Koenig Books, 2019).

47 Fred Moten: 'When I think about the way we use the term "study," I think we are committed to the idea that study is what you do with other people. It's talking and walking around with other people, working, dancing, suffering, some irreducible convergence of all three, held under the name of speculative practice. The notion of a rehearsal - being in a kind of workshop, playing in a band, in a jam session, or old men sitting on a porch, or people working together in a factory - there are these various modes of activity' (S. Harney and F. Moten, The Undercommons: Fugitive Planning and Black Study (Wivenhoe: Minor Compositions, 2013), 110.

48 It is important to think about these activities also within the context of what was happening at a political level from as early as the late 1960s where Sweden officially decided to offer humanitarian assistance to national liberation movements in Southern Africa. There were relationships between the Nordic Countries and the African Liberation Movements at both official and nongovernmental levels. They were taking a stand that was not necessarily aligned to the Cold War interventions driven only from the Soviet Union or through the American connections. On the cultural front, organisations backed by the CIA, namely the Congress for Cultural Freedom, set up various programmes to counteract what they argued as a Communism threat from the Soviet Union. This is broadly defined as Cultural Cold War.

49 T. Sellstrom, 'Culture and Popular Initiatives: From Frontline Rock to the People's Parliament' in Sweden and National Liberation in Southern Africa Volume II: Solidarity and Assistance 1970-1994 (Uppsala: Nordiska Afrikainstitutet, 2002), 757. [ Links ]

50 L. Bethlehem, L. Dalamba and U. Phalafala, 'Cultural solidarities: itineraries of anti-apartheid expressive culture -introduction to the special issue', The Journal of South African and American Studies, 20, 2, 2019, 145. [ Links ]

51 B. Peterson, 'Bhakti Shringarpure's Cold War Assemblages: Decolonisation to Digital', Social Dynamics, 57, 2021, 339.

52 Cropper gets credited as cover designer on the record's outer sleeve however the title of this artwork is not named.

53 Rasmussen, Mbizo, 113.

54 Club Montmartre also broadcast concerts on Danish radio (and possibly television), although it is unclear if, and if so where, these recordings are archived.

55 M. McGregor, Chris McGregor and the Brotherhood of Breath: my lije with a South African jazz pioneer (Grahamstown: [University Still Known as] Rhodes University, 2013), 81. [ Links ]

56 Rasmussen, Mbizo, 123.

57 Dyani: 'It is for me a matter of very great importance to get all the musicians in Sweden to join us in the struggle against the oppressors. We need their support.', Rasmussen, Mbizo, 240.

58 ANC Audiovisual archive, NAHECS,Anti-Apartheid Riot Squad 'The Cultural Voice of Resistance' in Amsterdam, December 1982.

59 Mabuza writes, 'AMANDLA will arrive in Sweden on the 8th November [1983] and leave, tentatively, on the 28-29 November. The program in Stockholm will take place on the 17th, 18th, 19th and 20th of November. The 18th is chosen to coincide with the big opening of the Africa-project at the Cultural-House.'

60 Rassmusen, Mbizo,149.

61 E. T. Smith, 'From Exile to Excellence', 2022, https://stories.camden.rutgers.edu/spring-2022-from-exile-to-excellence/index.html; T. Bell, 'Reflections of a Wayward Boy: Skeletons from exile days', 5 May 2021, https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2020-05-21-reflections-of-a-wayward-boy-skeletons-from-exile-days-in-somafco.

62 African Skies; South African Department of Arts and Culture, 'A catalogue of the Dutch Anti-Apartheid Movement Video Archive', Jstor Primary Sources, (2004).

63 Ibid..

64 Ibid..

65 As part of the digitised materials that came with the IISH collection, Born Under the Heat is not included. What is there includes Amandla-ANC Cultural Workers First Tour, Malibongwe, Jabula's Afrika Awake and Radio Freedom amongst others.

66 Because ANC archives are listed as part of the receiving institutions of these repatriated materials, we are of the impression that they made their way to NAHECS even though there is no accompanying accession register or inventory that was found.

67 For further reading on this 'archival transfer' see International Association of Labour History Institutions (IALHI), Archival transfers to South Africa', 2013, https://socialhistoryportal.org/news/articles/307383.

68 African National Congress, NAHECS, Repatriation Mission Box 6 Folder 1 item 2, Zonke Majodina, 'Prospects for Repatriation: A Psychosocial Study of South African Exiles', 1991, 4.

69 Ibid..

70 Rasmussen, Mbizo, 151.

71 L. Mabuza, 'Big Bassman M'bizo Dyani', 1 November 1986, NAHECS, Sweden Mission Box 59 Folder 253, University of Fort Hare, Alice.

72 K. Kgositsile, Homesoil in my Blood (Johannesburg: Xarra Books, 2017).

73 Kgositsile, 'Culture and Resistance in South Africa', 29.

74 Rasmussen, Mbizo, 234.

75 African National Congress Audiovisual archive, Johnny Dyani, Born Under the Heat, (Stockholm: Dragon Records, 1984).

76 Rasmussen, Mbizo, 234.

77 Rasmussen, Mbizo, 121.

78 Letter from Fikile Dyani, 4 November 1986, African National Congress Sweden Mission.

79 E. Said, 'Introduction', Reflections on exile and other essays (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2003), xiv. [ Links ]

80 Sinazo Mtshemla and Pinise Saul, East London, 22 January 2016.

81 Jordan, Rixaka, 8.