Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Kronos

versão On-line ISSN 2309-9585

versão impressa ISSN 0259-0190

Kronos vol.47 no.1 Cape Town 2021

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2309-9585/2021/v47a9

ARTICLES

Pondo Blue(s): Working through Sounding a Kind of Blue(ish) History of an Eastern Cape

Sinazo Mtshemla

National Heritage and Cultural Studies Centre, University of Fort Hare; https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4057-5637

ABSTRACT

Pondo Blues, is a song by Eric Nomvete and the Big Five, a group that came from East London to perform at the Moroka-Jabavu Stadium as part of the 1962 Cold Castle jazz festival. Although the song has acquired symbolic meaning and recognition as one of the 'classics' in South African jazz, prevailing understandings of the song have framed it as a traditional drinking song as well as a song lamenting the Mpondo revolt, where both these understandings have tied it deeply to the rural Eastern Cape. This paper tracks the sonic and social relationships of disarray, change and improvisation that come together to rehearse Pondo Blues across space and time, and atmospheres of history which move us away from iPhondo as the provincial Eastern Cape, which is tied up with the rural, the ethnic, the backward countrified folk and the local towards a more expansive and infinite sense/s of pasts and futures.

Keywords: sound, Eastern Cape, apartheid, sonic histories, multisensory histories, improvised music, creative innovation.

The four minute and sixteen seconds live recording of Pondo Blues, archived on vinyl and its subsequent copy to digital, where the analogue phonographic sound remains audible, starts with a one-minute prelude, an opening which creates a feeling of 'blue'. Blue here is heard as an expansive and infinite colour with multiple hues.1 It is slow in its tempo, easy to frame as sombre, a lament or an elegy in musical terms.2 The alto and tenor sax play together with restraint, accompanied by loud chatter, as well as the familiar hissing sound of a long-playing record. The cymbals, the piano and the bass step in after twenty seconds making an announcement of their presence. The wait seems so long. There is a small pause, where only the voices of people can be heard chattering. Then the alto and sax begin again a second opening almost like the first, but not identical. It moves slyly. The alto and tenor end off with the piano tapering off signalling an ending of something and anticipation of another movement. A precedence? Yet it does not even give us a hint about what is about to happen and how the song is going to move forward. It is discordant with the rest of the song. It does not frame the entire song as introductions are accustomed to do. It defies the introduction as a framing device that requires us to follow its predefined arrangement.

History frames events, historical events frame songs; that is the line we often take. This paper is therefore an attempt to write a history of an Eastern Cape through listening to a song. With this listening I would like to prompt a reading that takes us away, even momentarily, from singing a tune about the Eastern Cape as an ever recognisable cover. Pondo Blues, I would like to suggest, allows an imaginative working through and with the constraints that have limited our understanding of iPhondo as a neat translation of the word 'Cape', as taken to mean 'provincial', and as a narrow outlook, such as that found in a 'countrified person'.3 Pondo and iphondo/uphondo have linguistic meanings that create possibilities to take the listener down a road of meaning. iPhondo is not just or only 'Cape', 'provincial' and 'a countrified person', all of which I will return to again, but uphondo is also a horn not only of an animal but also that which resonates within itself as well as reverberates elsewhere when we blow into it.4 By bringing Pondo and Blue(s) together Nomvete was perhaps already hinting at an uneasy fit, of something farther than its literal conception. Pondo Blues, I would like to suggest, gives us a set of provocations that draw on colour (and name) not just as metaphor, not just 'the blues' or 'the mpondo', melancholic like a mood swing, but also as a swing that makes known a different sound. Prevailing understandings that have framed the song as being a 'traditional drinking song' as well as a song lamenting the Pondo revolt have thus neatly translated it, by again, tying in the Eastern Cape to the rural and to 'Red'.

Pondo Blues, I suggest, sounds the Eastern Cape as a space that need not bear the colour of Red, red which is ochre red, tribal red.5 If we listen to it, it allows us to colour the Eastern Cape differently, allowing us to think constraint and possibility in direct relation as an other Cape.

The song

Pondo Blues is a song by Eric Nomvete's Big Five that was performed at the Cold Castle Jazz Festival in 1962 at the Moroka-Jabavu Stadium in Soweto. The song remains live, with crowd noise audible, as can be heard on the record (LP) simply titled Cold Castle National Jazz Festival Moroka-Jabavu 1962. This LP recorded and issued by New Sound and Gallo respectively has become out of print, including its subsequent later pressings. What exists is a digital recording of the analogue album on various rare music websites and blogs and on YouTube.6 Here, with the original blue cover sleeve, (as well as a different independently produced sleeve7) one can listen to the performance, including the vinyl static and wear and tear, which both seems to add to its authenticity the sound of it pastness, temporally matching sonic technologies (of the phonograph) to the actual event, as well as presenting it as if live.8

The album has a selection of ten songs that were performed on the day (which includes Pondo Blues). Some of the songs included covers of Let the Good Times Roll and I've got Rhythm performed by musician and playwright Ben Masinga, A String of Pearls and This Can't Be Love performed by vocal group The Woody Woodpeckers and A Baptist Beat covered by the Jazz Giants just to name a few.9 Three out of the ten songs were performances by the Chris McGregor Septet (Chris McGregor, Sammy Maritz, Monty Weber, Christopher Columbus, Ronnie Beer, Danayi Dlova and Willy Nettie) which included the only version of When the Saints Go Marching In, the song all bands on the day had to cover to take part in the competition.10

Pondo Blues came third in the competition. The Big Five comprised Eric Nomvete as the bandleader on tenor sax, Mongezi Feza on trumpet, Shakes Mgudlwa on piano, Aubrey Simani on alto sax, Dick Khoza on drums and Dannie Sibanyoni on bass.11These musicians travelled from East London by train to participate.

According to Eric Nomvete's own account the group was not comprised of the 'usual guys' that he played with as they could not find get time off work. He says:

Dan Poho was the man organising things down at Dorkay House. When I was called up to compete, my group was in disarray. The usual guys could not get time off from work to join me.12

The disarray gives us a different sense that goes against the simplistic idea of music making, and the coming together of musicians into a group as a very organic and harmonious process. Nomvete also recalls the challenges he and his group encountered during the rehearsal stages in East London and the unorthodox methods they had to resort to in order to rehearse:

There were many wonderful groups from all over the country. We were a small-town group and lacked the facilities for rehearsals. If you used a private house, neighbours would complain about the noise. Money was also not available.13

The band therefore repurposed the train as a rehearsal space during their travelling to Johannesburg to perform. Nomvete further recalls that:

We rehearsed in the train to Johannesburg and 'Pondo' was played all the way to Bloemfontein. When we got here, we rehearsed at Dorkay House and Ndlazilwane encouraged us to continue with 'Pondo' which he liked very much.14

A migrant sound, then, following a journey already undertaken by many, forced and voluntary. Gordon Pirie has remarked that, in the 1920s and 1930s, on the migrant railway:

Boarding the enclosed cattle trucks signified a momentous plunge into an inorganic, noisy, dangerous world. The surface 'middle passage' by train was a track to underground where existence and motion were similarly tunneled. The rolling compounds were a premonition and reminder of tremors, darkness, claustrophobia, regimentation and Spartan barracks. They foretold and echoed deep captivity, and a troglodytic existence submerged in artificial light, dripping water and smoke. The railways conveyed both men and meaning.15

To be sure, a different journey in the early 1960s, even if still subject to train apartheid and one sounding a different assemblage of noise and motion, foretelling, alongside the ghosts of these men and meanings, an other cape of blue innovation and creativity, and perhaps of different undergrounds (freedom) (their own thing) (disarray?) and one I will return to. This is particularly resonant with Nomvete and the Big Five's train rehearsal experience, as it allows us to think of the railway station as intimated by Revill as a 'culturally rich and historically situated meaningful experience' and an 'imaginative resonance and creative interjection rather than simply a site of regulation and embodied routine'.16 Revill's expansion of Lefebvre's notion of rhythm is useful when thinking about the railway as a space that co-constitutes space and time as mutually dependent.17 Here we are then able practise active and reflective listening that is about social relations and reciprocities.18

More routinely, though, the musicking that Nomvete and his 'Big Five' perform in private houses and on the train conveys sonic and social relationships of disarray, replacement, change and improvisation, a coming together that rehearses Pondo Blues across space and time.

Musicking liberation and the transatlantic/ global

There is not much that has been written about the song apart from a few lines in a number of books and articles about the jazz festival. Yet, in popular imagination and in rhetorical reference and engagement it has travelled migrated acquiring symbolic meaning and recognition. It has been considered to have been a ground-breaking musical performance, situated as one of the 'classics' in South African jazz. Composer, bandleader and saxophonist Eric Nomvete was interviewed in 1981 in a Soweto newspaper about the significance of the song almost twenty years after its performance, to which he responded:

You have to be original and I think my 'Pondo Blues' set a precedent because most people began exporting our products instead of competing with others at their own work. They saw it could work out.19

He was not to be the only person to echo similar sentiments. East London born bassist Johnny Dyani in an interview in the mid-1980s also hailed Pondo Blues and the originality Nomvete and his band had brought to the Festival as the beginning of a type of awakening. Dyani noted:

So Mongezi [Feza] was invited to go there by another musician, from East London, Eric Nomvete, a tenor player, he's on one of the records. He composed that famous song that the Festival, the group won a prize, 'Pondo Blues'. Everybody was playing so-called jazz and this old man was hip enough that he had original stuff, so when he came in everyone was playing dauh, so this old man just came in with Pondo Blues, and that was it. And then everybody started being aware of their own thing, tradition, culture, whatever you call it.

Elsewhere in the interview he goes on to add that:

...But this man, what was fantastic, he did traditional Pondo blues, within. He didn't have to be changing, arranging, to be playing it and say well this is jazz. He was himself... 20

One reading of these arguments has been developed most extensively by Sazi Dlamini (although there are others)21 in relation to the politics of the festival and of histories and meanings of black jazz in South Africa. He argues that the 'internal' political dynamics of the festival itself, as a signifier of wider circuits of marketing association, influenced, to a large extent, the type of songs people performed and the naming of their compositions. He suggests that the festival and its organisers' mission was to popularise what he calls 'an Americanized feel' for the festival.22 The format for the competition was that all participating bands had to cover an American jazz standard When the Saints Go Marching In. Notwithstanding the fact that many of the competing bands such as the Jazz Dazzlers had existing popular repertoires of their own, according to Dlamini they still had to stick to the standard American jazz items.23 Gwen Ansell also noted that the album was dominated by 'beautifully but conventionally played covers' that were 'smooth-as-silk but slight archaic'.24 The exception to this Ansell wrote was a solo by Kippie Moeketsi on Kentucky Oyster (and Pondo Blues) which made the audience hold its breath. 25

More expansively, what is then significant about Pondo Blues is that it disrupted this requirement, in its refusal to perform the required standards, disarraying the expected and legislated sound and, as such, can be heard as an act of sabotage against the American-standard format that dominated the festival.

According to Dlamini, Pondo Blues was an expression of 'a locally determined musical hybridity' which had been marginalised at the festival. He had the following to say about the song:

This expression of 'triple consciousness was not abstract, nor was it subject to any harmonic manipulation realised through a mediation of advanced music literacy. The horns, like human voices, intoned wordlessly a well-known melody or symbolic performance significance, to the accompaniment of traditional drum rhythms and a piano reconstruction of the voices of the absent choir.26

Dlamini's reading of the song, suggests that Pondo Blues brought with it a tangible expression of triple consciousness by reconstructing the indigenous elements which were absent using horns, drums and the piano.27 Dlamini suggests that Pondo Blues is translating the global jazz idiom into the local. This I suggest is a move away from Nomvete's idea of exporting their own products which is a translation of the local to the global sense. What Nomvete and Dyani may be getting at, as I will expand on later, is the idea of an emergence of a South African sound that was not just a copy or a cover (another associated meaning with the cape) of the 'so-called jazz' from elsewhere. Rather than competing locally for what is the most authentic sound, they were imagining what they were doing as competing globally.

When Dyani suggests that Nomvete was doing 'traditional Pondo Blues within', he is opening up possibilities to bring the body back into conversation. This is something akin to Nyong'o's formulation of the black body 'as a musical and technical instrument that resounds at frequencies that confound its routinized, racialized instrumentation'.28 Although Dlamini's association of the song with a 'Xhosa dance pattern of umxhentso' can be one way to understand the 'within', there is also a reciprocal sense of being within the body that speaks to how black subjects transform and are transformed by sound.29 The disarrayed sense then not only speaks to the Nomvete's band's state of disorganisation but also to an inner sense of things that are embodied.

From the vantage point of that space, then, Pondo Blues opens us to a vastness, an expansive idea that not only defies the limitations and restrictions set up by the festival and its owners, but also opens us to a sounding of Blues that is not recognisable as an American product that has been imported but as a mutual exchange with no clear line of domination. It also explores the limits of bordered understandings of sound and takes flight away from Moroka-Jabavu (Soweto), from Eastern Cape (narrowly read as a Pondo drinking song) to an elsewhere.

The pause button

But what of Pondo Blues, iPhondo and Blue? There are two senses of the Eastern Cape, one taken from Eric Nomvete's description of his band as disarrayed, and also the more general articulation of the Eastern Cape as a place 'behind history' as one of disarray, constraint and breakdown.30 Counterposed to this is the other sense of the Eastern Cape as a political and social 'home of the legends'31 and a place that was ahead of its time, where everything started.32 Phyllis Ntantala eloquently gives us all these senses when she writes about the Eastern Cape as:

[T]he trailblazer in all that happened to my people and my country. Yes, indeed, this is where everything started; where great events took place the Eastern Cape, an area with a great history and heritage; a place with a legacy we should all be proud of.33

In the same breath she goes on to lambast:

But how sad! How tragic that in the New South Africa of the 21st Century, a place with such a history, is now notorious for being the most depraved, the most inefficient, corrupt, a drain on the economy of the country. What a shame!34

Ntantala's discontent with the current state of things in the Eastern Cape, may well sound like dissonance in the musical sense as meaning the discordant sounding together of two or more notes to produce a roughness, or tonal tension.35 In Pondo Blues the minute long alto and tenor sax playing together at the beginning of the recording (also aided by the hiss of the phonograph) produces tension. This opening allows us to think of sound in the form of a horn, an instrument, a sounding instrument that signals an arrival as well as something more critical, perhaps also sounding a different difference. A horn can be that of an animal as well as a musical instrument a saxophone, trumpet, trombone, and also musical instruments made from animal horns.36 When we think of a sounding together of a cow and a saxophone one is taken to Winston Mankunku's song Yakhal' Inkomo resonant with the bellowing sounds of the bull and the saxophone. A different difference sounds yet again.37

Sonic technologies such as the phonograph, as Erasmus alerts us through a reading of Patrick Feaster, rather than being seen as re-producing sounds also represents sound. As Erasmus further notes 'there is a process of reiteration in the act of recording and playback' that is not always taken into consideration.38 In order to track this difference, a further engagement with sonic technologies will be elaborated, in order to also ask about the presented sounds of Pondo Blues and the spaces of their appearances as they resonate and fold alongside these grammars of language (uPhondo/ Pondo/ iPhondo) and sonic hisses and interruptions of song/ melody/ music. Sounds which stir us to recognise situating as a problem.39

If we take wind to some of these different sonic pathways, Nomvete's Big Five is also suggestive of the horns found in some of the animals that are collectively known as the 'big five', which are the lion, elephant, rhinoceros, leopard and the cape buffalo.40 Furthermore Nomvete's saxophone, Aubrey Simani's alto saxophone and Mongezi Feza's trumpet feature prominently on the song in 'solos' and collectively.

Pondo Blues in its multiple versions, in its multiple articulations, invokes colour, sound as colour, and also sound that represents different resonances within itself and reverberations elsewhere. I would also like to suggest, though, that Pondo Blues helps us to think about a multiplicity of senses, senses that are not uniform or distinct but are in what we might call disarrayed translations, senses of an other Cape.

Sounding Duncan Village

Monica Hunter described 1930s East London as a place where:

Young people gather in private houses, particularly on Fridays and Saturday evenings, for 'parties', but at these European fox-trots are more often performed than the old Bantu dances. About the street one more often hears rag-time hummed than an old Bantu song.41

By the late 1950s, Leslie Bank in his study of the old East Bank Location (including Duncan Village) argued that older residents remembered the activities that appealed to them as young people which included: sport, music (especially jazz), fashion, entertainment (foreign films and magazines), politics and the quest to define new identities and a truly unique urban style' which he names as cosmopolitanism.42

Eric Nomvete features in the creation of this local scene that Bank writes about, through a number of bands that he had established such as the Havana Swingsters (a 15-piece big band), the Foundation Follies, the African Quavers, local musicals and other fundraising initiatives for the community of Duncan Village.43 Bank further usefully notes, that these top local bands such as Bright Fives, African Quavers, the Bowery Boys, Havana Hotshots and others, were creating an air of expectation and exhilaration for the community.44

Pauw also provides some further resonance to these sound and music atmospheres in Duncan Village in the 1960s. In one scene he describes the morning sounds in Duncan village where 'you hear some penny-whistles, a radiogram blaring out a monotonous concertina tune in a shop around the corner, and a woman in a beer-brewer yard humming the tune of a hymn'.45 Pauw also notes other sound producing activities such as gambling, casual conversations, occasions and ceremonies such as initiations of boys, ritual slaughtering and funerals, and Guy Fawkes parades.46

The 1960s however also saw the administration of mass forced removals in East London as in other places across South Africa. Here people were moved from Duncan Village to either villages outside the city or to Mdantsane, a newly built homeland township 25 km outside the city. Johnny Dyani, who also lived in Duncan Village before he left South Africa in 1964, recalled in an interview the sounds of East London that were punctuated by social and political gatherings and visits but almost routinely accompanied by constant police interference.

One scene, where Dyani describes in great detail the tensions that were in the atmosphere, is a day the Blue Notes were stopped by police while travelling on a local tour.47 According to Dyani this tension got exacerbated when the police officers asked McGregor, 'So are these your boys?', referring to all the other black band mates. Dyani recalls McGregor's face going pale, his eyes widening and leaving him breathing 'huh huhm huh huhm'.48 He also recalled other responses such as Nick Moyake and Dudu Pukwana answering for McGregor by responding to police with a statement 'I'm not nobody's boy'49 and urging McGregor to say something. Dyani also remembered Maxine, Chris McGregor's partner's attempts to neutralise the interaction with the police by getting them to 'cooperate' by not speaking back and reminding them that:

You guys, you must realise we going to go to Europe and your passports will be taken... We are saying, 'Who cares!?50

Dyani reveals his disdain for McGregor's threats when he says:

They have this thing that your passport...like little boys, you know, your candy will be taken off; you won't go and play again, some shit like this you know?51

This comment of Dyani's reveals the cracks and the fragility of the multiracialism within the Blue Notes.

In another part of the interview Dyani also recalls an event where police came to his home to 'collect him' at two in the morning for no real reason but to intimidate him. His mother had to go to the station to hear what was going on. In these encounters Dyani is suggesting that his mother's interaction with the young white officers can be understood within the context of what he calls the 'marabi thing', a tradition, a way of asserting yourself in the world. He says:

That's what I'm saying now when I say that the marabi thing, you see...my mother's talking in this tradition. So we, or the young officers, or the young black people of this generation they are in the same level of the white man complex: we have to prove to him. There's nothing to prove to him, you know, fuck him.... Fuck the boer. Just tell him. So my mother was talking in terms of this marabi kind of thing. So in other words she was trying to say to him, 'We know you all the way, we seen you develop, see you this and we saw you when you were a kid, babysitting, nanny.' In other words, she was putting him, boom!52

Boom! What Dyani calls 'this marabi tradition' is much more than Kaganoff's reading, which is about 'getting the better of the oppressor as a means of surviving within racism'. Rather it is a sonic tradition a way of talking, relating and responding and presenting that is beyond racial logics, beyond the 'white man complex' and beyond transatlantic cosmopolitanism. Marabi soundings of a different iPhondo. 53

What comes close to Dyani's narration is Nancy Rose Hunt's idea of a state of nervousness that surrounds the space and the moment altering spatialities and temporalities of sound. What, Hunt says, is found in colonies as nervous states is a 'a kind of energy, taut and excitable' a nervous national mood. Nervousness she argues yields disorderly, jittery states which register on multiple levels.54 Trouble, unease and restlessness.55 This is the early 1960s in South Africa and in Duncan Village.

The sounds of bannings and exile, new sounds, finding their ways into more contained spaces. Dyani recalls, 'we were giving all kinds of lifts to the guys who were in the underground'.56 There were oftentimes issues of space where Maxine McGregor would say that there was 'no space' and they would respond with there is 'a lot of space'. Space then becomes something that can be manoeuvred or made to fit new imperatives. Just as on the train, in the home.

Perhaps, as importantly, this hints at a new and different sonic connection for Pondo Blues. The imagined undergroundness of the railway translates into the underground movements of anti-apartheid activists, many of whom Dyani and his bandmates gave lifts to in their tour kombi, often unbeknownst to Chris and Maxine McGregor. The train and the kombi, rehearsing sonics of silence and improvisation simultaneously hidden and phrasing a rehearsal, a Pondo Blues.

Similarly, East London's locations have been described as 'horribly cramped and claustrophobic'57, where Nomvete's music and rehearsal became noise for neighbours and residents. Rehearsals are noisy and disarrayed events in their nature. The constrained space, ironically though, had also created another kind of 'cultural vibrancy and intensity' that made people want to get some air, and opened up the urge for festivals, fairs, contests and other outdoor activities and events.58 In 1962 these were closing down in forced removals, the sound of bulldozers and trucks, destroyed homes and houses. And a new sound: the sound of sabotage boom! Disarray.

People's senses were heightened by all that was going on, including sensitivity to explosions. Between 1961 and 1963 there were over 193 listed acts of sabotage that formed part of the Rivonia Trial Second Indictment. The indictment lists these events according to object, place of commission of act, date, time and description of act.59There are a number of sabotage acts that are listed to have happened in East London and Port Elizabeth. For instance, in the month of July in 1962 about three months before the Festival, an act listed as a throwing of a petrol bomb was performed at a 'Bantu Dwelling 404 Mtyeku Street Duncan Village'.60 Again in September 1962 the same report listed that 'the Bantu Administration Offices in Duncan Village' were left with an 'inflammable bottle bomb'.61

The acts of sabotage as well as the act of rehearsing both involve working with what one has. Although these acts of sabotage are in a political terrain, they are also replicated in the act of rehearsing music that which is named 'improvisation' in jazz terms.62 There is much to be said about what these acts of sabotage both in a political sense as well as in a music rehearsal sense meant for Eric Nomvete and his band. The improvisation in Pondo Blues does not begin at the compositional level nor can it be located during the performance at Jabavu-Moroka stadium. When Nomvete and his band use private houses to rehearse they have to be mindful of the noise they are creating for their neighbours. They have to find ways around these limitations.

What I am getting at is that the complaining neighbours are unwilling listeners who form a large part of the sounding of Pondo Blues. In constrained spaces of the Location in East London and on the train, the rehearsal could not be 'too loud'. If the boom of sabotage resonates, when one listens to the Pondo Blues recording, this connection presents a different timbre. It is one that has a soft, light and gentle touch of the instruments as they are played. The drums are lightly beaten, producing a cool, calm feeling, perhaps a quietening, following Nancy Hunt's idea of the effect of violence where restlessness and unease are oftentimes quietened in various ways. This may be what Amiri Baraka in Blues People was referring to when he spoke of the 'cool style' of the 1950s.63 The term 'cool', he argues:

[I]n its original context meant a specific reaction to the world, a specific relationship to one's environment. It defined an attitude that actually existed. To be cool was, in its most accessible meaning, to be calm, even unimpressed, by what horror the world might daily propose.64

He sees this response of calmness as one that is necessary in an irrational, violent racist world. To be cool is therefore nonparticipation.65 This quiet, cool feel of Pondo Blues is therefore thinking of improvisation as operating within two poles that of sabotage read as noise, as explosion, as well as the gentle intimate aspects of musicking. These two poles are not necessarily in opposition; they are like the railway track where they often converge and are reciprocal. This quiet play can also, in the recording be heard alongside the noise coming from the audience attending the festival. One can hear screams, shouts, whistles and clapping, forming part of the Pondo Blues recording which significantly transforms how we experience it. We are able to also witness Martin Mhlaba and Ndikho Xaba's description of the mood when the band started playing. Mhlaba said: 'When Pondo played everyone went mad!'66 Going mad is reflective of a nervous condition as Hunt suggests and most closely aligned in thought by Berlant's thinking around the openness to things and thoughts that are in motion what she calls the performance of thinking and intuitive recalibration as signs of troubled knowing where people are 'living in a historical present that they sense as distended'.67 In Pondo Blues then both the cool, calm, unimpressed way that Baraka is alluding to and the 'madness' experienced are registered as interconnected sonic histories.

When Johnny Dyani speaks about Pondo Blues bringing out a sense of awareness of 'our own thing, tradition, culture, whatever you call it', he is locating Nomvete within what he terms 'the fowl run', a concept that I think with in more detail else-where.68 But what is important for feeling a different history is that the 'fowl run' registers a sound that is so-called free jazz. 'Fowl run' is Mra Ngcukana's sense of what one would call universal, an awareness of the world, the black family in the world of music. 'Fowl run' was an attempt to move away from understanding freedom in narrow conceptions of liberation and tradition, feeling at an improvised sense within the confines of apartheid but moving beyond the binaries of modern versus tradition. These binaries as Bank argues are not useful because, as he shows in a study of a rural community, identities and gendered power relations are always shifting and negotiated. Therefore Bank makes the case that notions of tradition are not fixed; rather people work within, around and transcend these dichotomies.69

The colours they bring70

Katherine McKittrick puts colour and imagination in relation to each other. Thinking with colour, as McKittrick does, allows us to think about imagination as 'experiential and representational'.71 McKittrick draws similarities between colour and imagination in, that like colour, imagination is difficult to explain with clarity. She proposes that:

For this reason, I understand the work of imagination as both quiet and agentive (our inner imaginative thoughts are enunciated imperfectly: they outline the conditions for change, they invite us to do).72

With the quiet feel of the instruments playing on Pondo Blues, we are invited to listen, even if without clarity, and listen not only with our ears. If we were to imaginatively play with the colour blue that is evoked in Pondo Blues, what kind of hues of blue play out synaeasthetically?73

The tenor saxophone is said to be one instrument that is capable of producing an exceptionally wide variety of tone colour, therefore making it easier to differentiate tenor saxophonists by tone colour alone. Martin Mhlanga recalled that after Nomvete and the Big Five's performance of Pondo Blues at the festival, Nomvete's mouthpiece was grabbed from his saxophone, his handkerchief was also snatched and some buttons holding his trouser braces were ripped off to the extent that police had to escort him off the stage.74

A mouthpiece, it is argued, is one part of the instrument which determines tone colour. It is further suggested by Gidley that each instrument generates its own spectrum of frequencies which contribute to the uniqueness of its sound.75 Tone colour, also known as timbre, can also be understood as 'the personal characteristic of an individual player's style.'76 That is why, as Gidley suggests, saxophonists for instance can spend a long time looking for a mouthpiece.77

Looking for a mouthpiece the relational process of finding a sound and communication resonates with the field of oral history and particularly alternative and marginal voices as archives and registers of history from below.78 To be a mouthpiece means to speak for, on behalf of the voiceless.

Pondo Blues here, is often assumed to be a mouthpiece for The Mpondo revolt of 1960. It forms part of the commonly held understanding as articulated by Dlamini, Ansell, Rasmussen and others.79 The Mpondo revolt was part of a culmination of protests in what Kepe and Ntsebeza regard as a movement from passive to violent rural resistance that has various dimensions, explanations, forms of struggle and subsequent influence.80 According to Kepe and Ntsebeza, the tragic outcome of the Mpondo revolt happened on 6 June 1960 when apartheid security forces massacred, injured and arrested many people who had gathered on Ngquza Hill in the Eastern Pondoland. 81

The festival at Moroka-Jabavu stadium happened therefore just after two years since the events at Ngquza Hill as well as other massacres that occurred in Sharpeville and Langa. It is then little wonder that Pondo Blues was highly suggestive as a title, and linked the song to the revolt in Mpondoland, and given the outcome of the revolt, to a further different reading of blue as resonant of the blues as melancholic, of sadness, but also anger.

Sazi Dlamini in his thesis quotes musician Ndikho Xaba who was present at the festival recalling that:

When Eric Nomvete, who was from East London, came on with his group, it was such an electrifying moment when he played 'Ndinovalo, ndi-nomingi'.. .Beer bottles started flying all over the place.. .because he invoked the spirit of the black man.. .this is what we want to do! There is no need for us to go anywhere else but to look into ourselves.82

Dlamini goes on to elaborate that Xaba argued that the melody of Pondo Blues 'rekindled a simmering outrage following the brutal massacre of the Pondo by the South African army, their articulation of a black and blue colour, felt in the plural, in collective bruising.83

Jean-Luc Nancy's take on listening that deals extensively with timbre and resonance offers a further connection:

I would say that timbre is communication of the incommunicable: provided it is understood that the incommunicable is nothing other, in a perfectly logical way, than communication itself, that thing by which a subject makes an echo of self, of the other, it's all one it's all one in the plural. 84

Communication he adds is 'an unfolding, a dance, a resonance'.85 What then is the significance of Nomvete's mouthpiece being snatched from his saxophone in light of what he was communicating in Pondo Blues? Can we not then also suggest that he was communicating the incommunicable and the audience responded by echoing Pondo Blues? Furthermore taking from Sylvia Wynter's Black Metamorphosis, McKittrick argues that sound 'allows us to think about how loving and sharing and hearing and listening and grooving to black music is a rebellious political act that is entwined with neurological pleasure and the melodic pronouncement of black life'.86It is Pondo Blues that prompts disruption a revolt at the festival that, seemingly then, draws the blue bruised connection between the song and the Pondo Revolt.87But it does not end there.

Sounding Pondo Blues

In an attempt to expand on existing understandings, senses and provocations that a listening to Pondo Blues brings, researcher and writer Max Annas brought together to East London University of Fort Hare campus five men, mostly musicians, to listen to the song and 'to try to understand what is sounded like and what it meant for all of them individually and for SA [South Africa] politically'.88 They imaginatively speculated about what meanings the song carried and still carries in South Africa's collective imagination.

Annas asked a few questions to facilitate the discussion. One question he asked, which speaks to the question of timbre in its multiple resonances, was:

The notes of the album by Julian Beinart who says er... blah four bar theme with a strong folk flavour. And one is called by Gwen Ansell and she is saying something like er.the song with Xhosa chords. So what I want to ask you is are they imagining the Xhosa element in Pondo Blues or is there one? Is this jazz with an added folk flavour theme or smell?89

What Julian Beinart wrote on the sleeve notes of the album (from which Annas was drawing on) in more detail is that:

Veteran Nomvete, in bowtie and braces, and teenager Feza (the best trumpet at the Festival) carried the group, playing music more distinctly derivative from African music than any of the others. Especially so is Nomvete's PONDO BLUES which is built from a repeated four-bar theme with a strong folk flavour.90

Beinart is suggesting that the song is flavoured with 'folk', rather than it being 'folk', and Annas echoes that reading in his question. It is an important though nuanced distinction that the musicians pick up on when they respond to Annas's question. I quote their varied responses:

Mlungisi Gegana: 'For me there is a Xhosa feel to the song...there's a big influence of you know...'

Max: 'Can you describe that?'

Mlungisi Gegana: 'Jesus you know that...I cannot go any further than feeling the mxhentso... [lifting his arms up] ...they call it umxhentso, the Xhosa dance in the rhythm of that song... [he starts singing the part of Pondo Blues that begins at one minute and seven seconds] ...even the melody.'

Peter Makurube [background]: 'Yonkinto (everything!)'

Bheki Khoza: 'I won't even say it is the influence of Xhosa. It is Xhosa. Its very core... '

Patrick Pasha: 'His interpretation is very correct'

Mzoli Mdyaka: '... what we are trying to say with Pondo Blues it is based on umxhentso.'

In 1965 in a radio programme Africa Abroad, broadcast by the BBC and hosted by South African exiled writer Lewis Nkosi, Julian Beinart was a guest and they have a conversation about the significance of Pondo Blues.91This was after the song was played. Beinart responded to Nkosi's question about the significance of the song with the following answer:

Lewis I think there are probably three reasons, first is that it comes from the recording of the Orlando festival which in many ways was a tremendous landmark in South African music. Secondly it is played by a group from East London, Eric Nomvete and his big Five which up until that point were totally unknown in South African jazz. It is important because you find this phenomenon of people coming from out of the bush, from nowhere and contributing in a very lively way to the musical scene. This gives one tremendous optimism.the last point to most people it seems to have a very distinct African sound.92

Leaving aside for the moment Beinart's racist problematic attribution of 'coming from out of the bush', Sazi Dlamini and others however are more clear in their description of Pondo Blues being a rendition of a traditional Xhosa drinking-song.93Dlamini, using music terminology, recognises in Pondo Blues the 'remarkable exploration, through jazz sensibilities of African indigenous musical particularity', in this case 'traditional Xhosa (Pondo) vocal polyphony and harmony'.94 For Dlamini, then, Pondo Blues is Pondo.

In the interview with Beinart, Nkosi goes on to make the following observation about jazz in South Africa:

It would appear to me since the days of the Jazz Dazzlers, the musical scene in South Africa has become much more complex in the sense that there are various influences now at work and now there is a much readier attempt to exploit the indigenous African tradition.95

Liz Gunner understood this point as demonstrative of Lewis Nkosi's intervention of drawing jazz into debates about what re-constitutes contemporary African tradition and well as Nkosi's attempts to 'cut through notions of bounded tradition'.96

It is interesting then, that when Annas asks Mlungisi Gegana to describe the Xhosa feel that he is referring to, he struggles to find words. He can only explain it through an act of moving and shaking his stretched out arms demonstrative of uku-xhentsa (dancing). The 'Xhosa feel' Gegana refers to is a feeling that prompts one to move in tandem with the rhythm and melody sections of the song.97 According to Gegana's explanation, movement in the form of dance is the only available way of articulating the sound one hears. Expression of the sound is found more than in words, showing the limits of relying on one sense. There is no simple mouthpiece.

'Xhosa feel' may have resonances with the meaning ascribed to the term iPhondo (a countrified person) which in this case may be associated with the notion of the Xhosa as tribal, traditional, countrified etc. However, Peter Makurube's response where he defines 'the Xhosa feel' as 'everything' may suggest a move away from a unified understanding of a feel which cannot be separated out and rather suggestive of Nkosi's 'unbounded tradition' that is both less than and more than Mpondo, Xhosa, or even indigenous African. This goes against the idea of a 'distinct' sound being easily originary. Bheki Khoza, also echoing and expanding on Makurube's unified understanding, suggests that rather than viewing Pondo Blues as having Xhosa influences one should rather say that 'it is Xhosa'. 98 One can discern a complicated set of readings of the song that do not find comfort with Beinart's widely disseminated reading as found on the sleeve notes of the Cold Castle album and as designated as the 'bush'. What the interviewees are suggesting is something else; they are arguing for us to hear Pondo Blues as not representing narrow provincial understandings but an opening up of iPhondo beyond the borders of our senses.

At this point it is worthwhile to go back to colour by way of a blue note.99According to Amiri Baraka 'blues is first a feeling, a sense-Knowledge. A being, not a theory the feeling is the form and vice versa.'100 In Pondo Blues, the 'mxhentso' feeling when the musicians that were interviewed started humming that particular part of the song, there is a feeling of instant recognition or, by way of Jean-Luc Nancy, a communication, a contagion of flavour, taste and air in the body.101

A cover that is covered with blue(s)

Max Annas during the interview with the elders also attempts to enter the discussion around the association of Pondo Blues with the Mpondo uprisings. He asks:

So if you agree to the strong Xhosa feel in the music, what I would love to understand is additionally when it comes to politics, Pondo Blues..er.. what did the song carry politically? I mean what did the song say without saying it with words? What people hear when they heard Pondo Blues two years or so after the uprisings? Actually what was the song about?

Bheki Khoza's response suggests particular songs in history have had the effect of sounding the atmosphere of the time. He elaborates on this:

What is happening you know with this recording you're talking about Peter on I think I was in 1964, the record of Castle Lager you know what happens is that once those things are captured like the recording like that...take for instance Yakhalinkomo of Mankunku that song became popular long before it was recorded or from a particular recording that happened on SABC because people were singing that song... I didn't get to have my hands on that recording until I was finished high school. I've known this song from when I was young and at that particular time it didn't even have the lyrics just the sound of the title which says Yakhalinkomo which translates into 'Bellowing Bull'. You could feel it was a cry. It was a cry of the people.

Here, with this sense of a feel and a crying out, I want to turn to a cover (sample?) version of Pondo Blues found in the song Zukude on the 1983 album In the Townships by Dudu Pukwana.102 Sazi Dlamini argues that this album is a powerful 'reference point for the discussion of narratives of resistance and the construction of imagined communities by dislocated groups'. Here Pondo Blues is 'dislocated' and disjointed. Dlamini's linking of this Pukwana album as a construction of exiled identities offers another dimension. The song Zukude is about movement of a different kind. Here origins are under question. Dlamini explains that Zukude at bar 78 segues into Eric Nomvete's composition of Pondo Blues in a form of a 'searing trumpet solo by [Mongezi] Feza'. What is significant here is that Mongezi Feza, who was also part of the original line up of musicians who performed at Moroka-Jabavu, has a chance to re-arrange a piece of the song elsewhere. Pondo Blues is given a new identity that is not recognisable as a cover because its title does not offer any clues. The Pondo Blues rendition by Feza, about halfway into the song, not at the beginning, bursts out in a surprising way, almost as if an aural unconscious or, with McKittrick, the experiential agency of imagined blue sky (against the grey of Europe).

But this song has in the lyrics, a phonics. It says that: 'uRhadebe akasazi neentaka' [Radebe does not even know the birds]. Dlamini understands this as showing the itineracy of exile where one is disconnected and also one has taken flight and has become a lost bird. Here in these outbursts of the trumpet solo by Feza of a sample of Pondo Blues, a connection to Nomvete's vision of 'out-of-worldliness', that moves songs beyond locality and origin to places that are discordant with their existence, but where we are still able to make sense and know them, to listen, or feel? Or both?

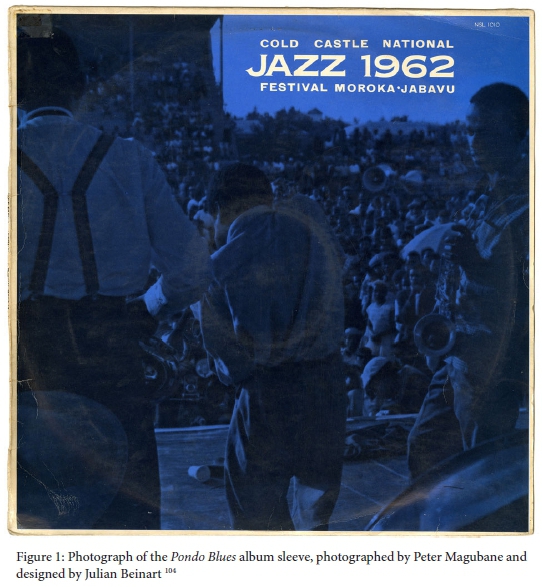

The vinyl cover sleeve of the Cold Castle Jazz Festival album, credited to Julian Beinart as designer, while the actual photograph that is used on the cover was taken by Peter Magubane.103 The people that are on the stage in the image are Eric Nomvete's Big Five even though not all members of the band appear on the cover. Most strikingly the album is coloured blue.

The shade of blue gives a new level of depth to the photograph, transforms the atmosphere. Blue, colour of sky or the ocean, gives the image of the event a wider and more expansive view to look from. What is also striking is the inverted way that we are encouraged to look from. Rather than the more customary view of looking up at the stage, where the musicians are in full view, here we see the musicians from the back, and the audience is staring at us. What of the paper cup lying on stage? A small, yet significant start of the revolt to come. Here at this moment is the before, the calm before the storm, a building of atmosphere. The audience is paying full attention, even one man can be seen from far (because we have an advantage of seeing from above), with his chin resting on his hand in a symbolic and contemplative gesture of deep thought, deep engagement.

This photograph stands in stark contrast to the narrative about the moment Eric Nomvete and his band come on stage, as the moment of great exuberance, a joyful revolt to follow. Here in this moment, the cold of the blue can be felt. When someone has their back to you, it is a gesture that suggests detachment. Here both Mongezi Feza and Eric Nomvete (as we can tell him from the braces he is wearing before the moment they get snatched from him) have their backs to us. We can also not see their instruments in full light except for Dannie Sibanyoni's sax. But Mongezi's side view of his face blowing the saxophone also gestures a moment heavy with improvisation. The way the fellow musicians are watching him play shows a deep level of connection and intimacy.

The blue transforms the audience into a wave. Their presence is overwhelming and fills up almost all the empty space. A piece of the sky shows, sky blue? In the sleeve notes Beinart comments on the warmth and the sun of that Saturday afternoon. He also comments on what he calls the peculiar mixture of relaxation and razor-edge concentration. The blue offers contrast between warm and cold, relaxation and concentration, as well as detachment and intimacy.

Maybe the most important thing about the Festival was the fact that the musicians played all day to people who enjoyed hearing good music, 4,000 fans sat on the grass, families grouped under sun umbrellas, tight-pantsed girls twisted on the grass. Musicians, organisers, judges, listeners: all were mixed together in a packed arc radiating from the bandstand. But a Festival is more than the music played there. Audience, the place, the weather, the holiday all are part of a particular feeling, a peculiar mixture of relaxation and razor-edge concentration. You feel it at Newport...and you felt it at Moroka-Jabavu.105

He continues that:

Consequently, Festival music is different from studio or club music. It is relaxed but yet competitive and tense. In having to reach further, it has to be played on a scale much larger than the music of the intimate nightclub. Festivals are shows and musicians naturally become big showmen.106

Pyper argues that festivals such as the Cold Castle Festival played a very distinctive role within contemporary public culture in South Africa and was effective in creating an alternative or oppositional public sphere to racialised capitalism and apartheid.107 Pyper notes further that music has the ability to mediate between complex and fraught relationships between modernity and tradition, indigeneity and cosmopolitanism. Through events such as the festival, lines could be crossed and new atmospheres anticipated.

In this paper I have tried to think towards a multisensory, syneasthetic (disarray of senses) expansive sense of understanding the Eastern Cape using the composition Pondo Blues. In thinking with Pondo Blues in its multiple variations and covers, I have exposed the limits of songs as covers of historical events but rather opted to think and work with the colours, multiple hues of blue/s that sound offers as a way out of the limitations that current readings of the Eastern Cape offers. Taking on Berlant's assertion that we are directed through a reading of Pondo Blues/Mpondo revolt/festival/rehearsal/acts of political sabotage not to see these as events but as historical environments that can be sensed, atmospherically, collectively.108Pondo Blues allows atmospheres of history to move us away from iPhondo as the provincial Eastern Cape which is tied up with the rural, the ethnic, the backward countrified folk and the local towards a more expansive and infinite sense/s of pasts and futures.

The financial assistance of the National Research Foundation (NRF) and the DST/ NRF SARChI Chair in Social Change at UFH towards this research is hereby acknowledged. Opinions expressed and conclusions arrived at, are those of the author and are not necessarily to be attributed to the NRF.

1 Here Katherine McKittrick is helping me to work through ideas of blueness as relational and infinite. Blueness for her is a colour that moves between softs and darks, the indescribable and bold. In her thinking with the colour blue in relation to Nina Simone's album Pastel Blue, she relates the colour blue in all its hues as something that cannot be fully described nor replicated. She argues that 'one cannot fully limit the description of blue to merely describing colour, a song, a genre, as evocation, embedded within corporate infrastructures, as image, as record, as creative text, as feel, as ...' and so goes the endless list. See K. McKittrick, 'Pastel Blue: A Promising Inaccuracy, Los Angeles Review of Books, 27, August 2020.

2 A dirge can be a song sung in commemoration of the dead or a song sung in mourning or an instrumental piece sung to express mournful sentiments. See M. Boyd, 'Dirge', Grove Music Online, https://0-doi.org.wam.seals.ac.za/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.07833 (accessed 22 June 2021).

3 Arnold Fischer's English-Xhosa dictionary has given the Xhosa word for 'province' to be iphondo. The word provincial can then have words in Xhosa which associate it to a person such as describing a person who lives away from urban areas as umntu waseluphondweni. This meaning can also be extended to describing someone's behaviour or status, for instance when it refers to a person as being countrified, or as being narrow in their outlook. Here the term umntu wasemaphandleni is used as a translation of 'provincial'. This can be an adjective or a noun. For other definitions that also describe iPhondo as 'the Cape' see A. Fischer, E. Weiss, E. Mdala and S. Tshabe, English Xhosa Dictionary (Cape Town: Oxford University Press, 1985), 489.

4 Uphondo is any horn whether that of an animal or a musical instrument. Fischer et al, English Xhosa Dictionary, 281.

5 Here the research and writings of prominent white anthropologist Phillip Mayer comes to mind, particularly with the text of P. and I. Mayer's Townsmen and Tribesmen: Conservatism and the Process of Urbanization in a South African City, as well as that of B. A. Pauw, The Second Generation: A Study of the Family among Urbanized Bantu in East London (Cape Town, London and New York: Oxford University Press, 1962). Their case studies framed the lives of black people living in East London's urban spaces as involved in a process of change that was in a continuum of rural to urban and the connotations carried in each of these understandings. The Mayers and Pauw conducted studies that focused on a perceived interplay between urban and tribal phenomena where distinct lines were drawn between 'Red' and 'School' Xhosa, where bounded 'Red' people were defined according to their appearance as people who smear red ochre on their faces and are therefore marked as rural, uneducated, tribal and other derogatory and racist associations. See, for instance, P. and I. Mayer, Townsmen or Tribesmen: Conservatism and the Process of Urbanization in A South African City, 2 ed. (Cape Town, London, New York and Toronto: Oxford University Press, David Philip and Namibia Scientific Society, 1971), vii.

6 The Pondo Blues recording is available on YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=z6jetAovKbQ. The blog flatinternational.org provides the most detailed information about the LP, which includes images of the front and back covers of the record sleeve, the liner notes, vinyl labels and other details which show important information about when the LP was recorded and issued. Simeon Allen, 'Various Artists Cold Castle National Jazz Festival 1962', flatinternational south African audio archive, 28 June 2021, https://www.flatinternational.org/template_volume.php?volume_id=119#.

7 The Cold Castle National Jazz Moroka-Jabavu 1962 album was reissued and remastered as a CD in 1991 with a different sleeve cover of an image of a four-piece band performing. There is also another LP cover with no image but written in Bold Limited Edition as well as the title Cold Castle National Festival Moroka-Jabavu 1962 with the names of the artists that featured. The date of this release is unknown. The different sleeve cover can be seen on 'Various-Cold Castle National Festival Moroka-Jabavu 196', Discogs, 28 June 2021, https://www.discogs.com/release/10320107-Various-Cold-Castle-National-Festival-Moroka-Jabavu-1962/image/SW1hZ2U6MzE5NDY2NTE=.

8 The concept of 'live' needs further elaboration and there is much scholarship that deals with what constitutes liveness and the view that the concept is fluid and 'contingent upon historical context, cultural tradition, implicated technologies..." See P. Sander, Liveness in Modern Music: Musicians, Technology and the Perception of Performance (New York, London: Routledge, 2013), 18. In the case of Pondo Blues what circulates is what Auslander calls 'mediatized' performance, those being audio or video recordings. What is at stake in the arguments made by Philip Auslander is a move away from thinking in binary terms, 'the live' as being oppositional. See also P. Auslander, Liveness: Performance in a Mediatized Culture, 2 ed. (Oxford, New York, Canada: Routledge, 2008).

9 Let the Good Times Roll is a song written by Sam Theard and Fleecie Moore. What is there to say is by Vernon Duke and E. Y. Harburg. I got Rhythm is by George Gershwin, String of Pearls is composed by Jerry Gray with lyrics by Eddie DeLangfe. A Baptist Beat is written by Hank Mobley. All these are American composers.

10 Some of the bands that were at the festival also include The Woody Woodpeckers, which had singers Victor Ndlazilwana, Bennet Majango, Johnny Tsagane and Boy Ngwenya; The Jazz Giants, which included Dudu Pukwana, Tete Mbambisa, Martin Mgijima, Early Mabuza, Nick Moyake and Elija Nkwayane; The Jazz Dazzlers, featuring musicians Mackay Davashe, Patrick Matshikiza, Saint Moikangoa, Early Mabuza, Kippie Moeketsi, Blythe Mbityana and Dennis Mpali; as well as the Jazz Ambassadors with Ephraim Cups-and-Saucers Nkanuka, Temba Matole, Lami Zokufa, Louis Moholo and Lango Davis; as well as Eric Nomvete's Big Five whose musicians have already been listed in the paper. See Simeon Allen, 'Various Artists Cold Castle National Jazz Festival 1962', flatinternational south African audio archive, June 28, 2021, https://www.flatinternational.org/template_volume.php?volume_id=119#.

11 There is some contention about the number of people who formed part of Eric Nomvete's Big Five band. When one looks at the copy of the cover sleeve, it lists six people including Nomvete as the band leader. Lars Rasmussen, in his book on Johnny Dyani, draws a different conclusion that there were five people, basing this on interviews he had with musicians and historians who were present as well as his own judgement that when he listens to Pondo Blues he cannot hear the sixth instrument. He can only hear the tenor sax, trumpet, piano, drums and bass. See L. Rasmussen, Mbizo A Book about Johnny Dyani (Copenhagen: The Booktrader, 2003), 28.

12 M. Mhlaba, 'Saxman with army-style braces sets a new trend,' Soweto News, June 23, 1981, 17

13 Ibid..

14 Mhlaba, 'Saxman with army-style braces sets a new trend', 17.

15 G. Pirie, 'Railways and labour migration to the Rand mines: Constraints and significance, Journal of Southern African Studies, 19, 4, 1993, 713-730.

16 G. Revill, 'Points of departure: listening to rhythm in the sonoric spaces of the railway station, The Sociological Review, 61, S1, 2013, 52.

17 Revill, 'Points of Departure', 57.

18 Ibid..

19 Mhlaba, 'Saxman with army-style braces sets a new trend', 17.

20 A. Kaganof and J. Dyani, 'The Forest and the Zoo', in Chimurenga 15, The Curriculum is Everything (Cape Town: Kalakuta Trust, 2010), 34.

21 S. Dlamini, 'The South African Blue Notes: Bebop, Mbaqanga, Apartheid and the Exiling of a Musical Imagination' (D.Phil. thesis, University of KwaZulu-Natal, 2009); G. Ansell, Soweto Blues (New York, London: Continuum, 2005).

22 Dlamini, 'The South African Blue Notes', 158.

23 Ibid..

24 Ansell, Soweto Blues, 128.

25 Ibid..

26 Dlamini, 'The South African Blue Notes', 169.

27 What Dlamini is speaking about when he talks about triple consciousness; he is referring to an expansion of the term double-consciousness and adding a third consciousness that is located in the South African context. The three consciousnesses that are interacting are what he calls the 'participatory consciousness of indigeneity, hybridity and cultural Europeanism'. Examples in jazz music, Dlamini notes, can be discerned in the music of Victor Ndlazilwane's Jazz Ministers, Pat Matshikiza and The Soul Jazzmen where this consciousness found its full expression. See Dlamini, 'The South African Blue Notes,160.

28 Ibid..

29 T. Nyong'o, 'Afro-philo-sonic Fictions: Black Sound Studies after the Millennium' Small Axe, 18, 2, 2014, 174.

30 In the newspaper column titled Remember when by the writer Martin Mhlaba takes readers down memory lane to 1962 at the Jazz festival at Moroka-Jabavu stadium almost 20 years later. Mhlaba interviewed Eric Nomvete at a time when he was in Soweto working on the music for a play Kofifi Blues by playwright Sol Rachilo. Nomvete is quoted to have used the word 'disarray' to describe the state his group was when they were preparing for the competition, See Mhlaba, 'Saxman with army-style braces sets a new trend', 17.

31 Home of the legends is a concept coined by the Eastern Cape provincial government with the aim of memorialising 'legends' that come from the Eastern Cape and setting up the Eastern Cape as a great place because of these leaders such as Nelson Mandela, Govan Mbeki and other key figures. The idea is based on the notion that Eastern Cape 'is the world in one province' where everything can be found in abundance, beautiful landscapes, influential political, cultural figures and so on. See 'The Eastern Cape Home of the Legends, https://ecprov.gov.za/the-eastern-cape.aspx (accessed 16 June 2021). According to Webb and Ndletyana, the concept originated as an Eastern Cape branding and marketing exercise in 2012 which included the promotion of heritage sites, the installation of billboards and banners placed in prominent places throughout the Eastern Cape province. The concept of legend, as they note, initially tended to focus on male politicians but was later redefined to include not only people but places and events that set the Eastern Cape apart from the rest of South Africa. See D. A. Webb and M. Ndletyana, 'The Home of the Legends Project: The Potential and Challenges of Using Heritage Sites to Tell the Pre-colonial Stories of the Eastern Cape' in J. Bam, L. Ntsebeza and A. Zinn (eds.), Whose History Counts: Decolonising African Pre-colonial Historiography (African Sun Media, 2018), 140.

32 National Heritage and Cultural Studies Centre, University of Fort Hare, Alice, Phyllis Ntantala Jordan Papers Box 6 Folder 1, P. Ntantala, 'The Eastern Cape', 30 October 2006.

33 Ibid..

34 Ibid., 3.

35 N.d, 'Dissonance', Grove Music Online, https://0doi.org.wam.seals.ac.za/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.07833 (accessed 22 June 2021).

36 See Oxford Dictionary Online for the various definitions of horn. In jazz and traditional music any lip vibrated brass instrument is usually called a horn. See Jeremy Montagu's contribution in A. Latham (ed.), The Oxford Companion to Music (Oxford University Press, 2011).

37 Yakhal'Inkomo is a classic album and song with the same title by Winston Mankunku Ngozi released in 1968 which translates as 'the bull bellows'. One of the ways that the song has been understood to represent is that it was a motif of the pain of black people living in Apartheid South Africa. As Mankunku himself said in an interview with Salim Washington, the song was articulating that: 'We had enough, so we were complaining'. See S. Washington and W. M. Ngozi, 'Inaudible I', Chimurenga 15 The Curriculum is Everything (Cape Town: Kalakuta Trust), 110.

38 A. Erasmus, 'The Sound of War: Apartheid, Audibility, and Resonance' (D.Phil. thesis, University of the Western Cape, 2018), 34.

39 Here is a take on John Mowitt's argument about the problems of attempting to situate sound and the broader argument about how the field of sound studies needs to recognise a problem in attempting to situate and to rather try to understand 'how sounds situate situating' thereby recognising that situating is where the problem is. See J. Mowitt, Sounds: The Ambient Humanities (Oakland, California: University of California Press, 2015), 13.

40 The big five animals are considered to be the great treasures of Africa, representing greatness and danger, difficult to be hunted, yet the most hunted species that need to be protected and also to be kept free. L. Langley, 'What are Africa's Big Five? Meet the continent's most iconic wildlife', National Geographic, https://www.nationalgeographic.co.uk/animals/2019/07/what-are-africas-big-five-meet-continents-most-iconic-wildlife (accessed 10 July 2021).

41 M. Hunter, Reaction to Conquest (London: Oxford University Press, 1936), 455.

42 Bank suggests that the post-war period 'signalled a local cultural renaissance that raised cosmopolitan influences in location life to new levels'. These cosmopolitan influences were located in what Bank sees as an 'explosion of new music groups, sports clubs and dancing styles, and brought a succession of musical, sports and dance acts to the city'. Spaces such as Community halls, like the Peacock Hall, sports grounds (Rubusana Sports ground) and even verandas of people's homes were key to these cultural exchanges. Despite the claustrophobic conditions that township existence came with, these centres and halls were particularly significant because they were the only venues that catered for black people, therefore attracted people from other locations in East London such as East Bank, West Bank and North End. Bank argues that 'given the limited access location residents had to public space in the "white city", they made the most of their segregated public facilities by hosting a wide range of events that drew massive popular support'. See Bank, Home, Space, Street Styles, 75. Bank's reading of these activities as displaying cosmopolitan influences needs more thought particularly in light of Scholarship that thinks critically about the concept outside the Western universalist conception that is based on the 'global reach of modernity and the ultimate unity of humankind' as harkening back to the West. Stuart Hall, Achille Mbembe and Taiye Selasi and others have critiqued the Western-centred understandings of cosmopolitanism. That is why Mbembe and Selasi have opted for the concept of Afropolitanism to describe a different kind of conception of cosmopolitanism which imagines African identities as open-ended. The universalist perspective presents cosmopolitanism as benign but Hall suggests that there is the limited kind of cosmopolitanism driven from above which is about global corporate power, circuits of global investment and capital. There is also what he calls cosmopolitanism from below which 'is driven by movements of people across borders, where people are obliged to uproot themselves from home, place and family, living in transit camps or climbing on the back of lorries or leaky boats or the bottom of trains and airplanes, to get to somewhere else'. See P. Werbner and S. Hall, 'Cosmopolitanism, Globalisation and Diaspora' in P. Werbner (ed.), Anthropology and the New Cosmopolitanism: Rooted, Feminist and Vernacular Perspectives (Oxford, New York: Berg, 2008), 346.

43 Coplan also names Eric Nomvete's Foundation Follies as being the first professional African company to perform at the City Hall in Johannesburg in the early 1950s as having travelled to Johannesburg from East London. See D. Coplan, In Township Tonight! South Africa's Black City Music and Theatre, 2 ed. (Jacana Media: Cape Town, 2007), 210. When one therefore thinks about the movements made by Nomvete and other musicians between the bigger cities and East London and as far as Mozambique it is easy to want to understand this freedom of movement as the benign cosmopolitanism that does not take into account the inequalities and the exploitation that was also rife towards black performers.

44 Bank, Home Space, Street Styles, 55.

45 B. A. Pauw, The Second Generation: A study of the family among urbanized Bantu in East London (Oxford University Press: Cape Town, 1964), 24.

46 Pauw writes about the dice game called roqoroqo which is an onomatopoeic word for the rattling noise that the dice make. Here I am not aligning music with sound, but simply drawing on some connections that show that the sound of the city/ town and the notion of sound is much more than this, but is largely illustrative here.

47 The Blue Notes included Johnny Dyani, Nikele Moyake, Dudu Pukwana, Mongezi Feza and Chris McGregor. The naming of the band Chris McGregor's Blue Notes was seen to be problematic because it suggests that McGregor was the head of the group rather than all members having equal status.

48 Kaganof and Dyani, 'The Forest and the Zoo, 17.

49 Ibid..

50 Ibid..

51 Ibid..

52 Kaganof and Dyani, 'The Forest and the Zoo', 19.

53 Here I am drawing on LaBelle's conception of rhythm which also takes the 'acoustic and resonant spaces of reverberation, repetition, diffusion, interference and echo' as part of rhythm. As is suggested, the meanings that are created, communicated and translated through sound are associative. That is how then as Revill argues 'sound brings us into intimate contact with activities, actions and events which lie well outside the reach of other senses, round the corner, over the next hill or in an adjacent room'. See Revill, 'Points of Departure', 60.

54 N. R. Hunt, A nervous state: violence, remedies, and reverie in Colonial Congo (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2016), 5.

55 Ibid..

56 Kaganof and Dyani, 'The Forest and the Zoo, 18.

57 Unpublished untitled paper shared by Gary Minkley about the history of the East Bank Locations in East London.

58 Ibid..

59 Annexure A and B list sabotage activities from all provinces with times and dates and descriptions of the types of actions. These lists are annexures to documents filed before the Supreme Court of South Africa in 1963 as part of the Rivonia Trial. See Second Indictment: Annexure B: Particular of commission of acts, AD1844 A2.3.3, State vs Nelson Mandela and 9 Others (Rivonia Trial), Wits Historical Papers, accessed online http://www.historicalpapers.wits.ac.za/?inventory_enhanced/U/Collections&c=265691/R/AD1844-A2-3-3.

60 Ibid., 7.

61 Ibid., 9.

62 I am grateful to Ben Verghese for the intellectual input he has made in reading my work and where he makes connections 'between acts of sabotage, the act of rehearsing as potentially naming an action we associate with music called jazz which is improvising'.

63 Baraka in in his book Blues People writes about various 'styles' such as cool, swing, which have come to define black musical styles. He traces how these terms become formalised and taken out of context to be used by the commercial music industry. See L. Jones (Amiri Baraka), Blues People: Negro Music in White America (New York: Morrow Quill Paperbacks, 1963), 212.

64 Ibid., 213.

65 Ibid..

66 Mhlaba, 'Saxman with army-style braces sets a new trend', 17.

67 L. Berlant, 'Thinking about feeling historical, Emotion, Space and Society, 1, 2008,7

68 S. Mtshemla, 'Fowl runs, the cow, and liberation songs: squawking race, tradition and freedom', Unpublished paper, 2018.

69 L. Bank, 'Beyond Red and School: Gender, Tradition and Identity in the Rural Eastern Cape', Journal of Southern African Studies, 28, 3, 2002.

70 This title is taken from Port Elizabeth born trumpet player Feya Faku's album released in 2005. Feya Faku, 'The Colours they bring', CD, Archive Publications, 2005.

71 McKittrick, 'Pastel Blue', 34.

72 Ibid..

73 Neuropsychologists tell us that in the world there exist people who, when they hear a note playing, they simultaneously see a particular colour. Each different note produces a sensation of seeing a different colour. They call this condition, synaesthesia. What this condition produces is a mixing up of senses instead of them remaining separate. The work of metaphors, Beeli, Esslen and Jancke suggest, is the most common way that we can understand how synaesthesia works. It is in metaphorical understandings they are that two seemingly incongruent concepts can fit into each other. For instance, a musical tone can be described as warm or cold. In this paper therefore I am suggesting that a synaesthetic reading of Pondo Blues could open up for us 'cross-modal linkages' that are always at play but require closer listening.

74 Mhlaba, 'Saxman with army-style braces sets a new trend', 17.

75 M. C. Gridley, Jazz Styles: History and Analysis, 4 ed. (Prentice Hall: New Jersey, 1991), 388. [ Links ]

76 Ibid..

77 Ibid..

78 As Klopfer argues that in South Africa people see oral histories as the obvious basis for a new and inclusive national memory where oral history is seen as more democratic and provides alternative narratives in our understanding the past. See L. Klopfer, 'Oral History and Archives in the New South Africa: Methodological Issues, Archivaria, 52, 2001, 100-125.

79 Dlamini, 'The South African Blue Notes', 168; Rasmussen, Mbizo, 28.

80 According to Kepe and Ntsebeza the Mpondo revolt happened in the context of the declaration of a state of Emergency, and the banning of political organisations as well as massacres such as Sharpeville and Langa during the marches, which were largely located in urban areas. The Mpondo revolt was therefore significant in that it highlighted rural struggles in South Africa. T. Kepe and L. Ntsebeza, 'Introduction' in T. Kepe and L. Ntsebeza (eds.), Rural Resistance in South Africa: The Mpondo Revolts after Fifty Years (Leiden: Brill, 2011), 1.

81 The gathering on Ngquza hill was as a result of many grievances with Paramount Chief Botha Sigcau who had been installed by the NP government. His legitimacy was therefore in question. The people therefore gathered in protest against government's policies on rural administration and governance. Eleven people were killed on that day and others were badly injured. See Kepe and Ntsebeza, 'Introduction', 1.

82 Quoted in Dlamini, 'South African Blue Notes', 168.

83 Sazi Dlamini in his thesis on the Blue Notes and the exiling of the imagination references Ndikho Xaba's analysis of what Pondo Blues was about as a rekindling of a simmering outrage following the brutal massacre of the Pondo by the South African Army. See Dlamini, 'The South African Blue Notes',168. This idea of a collective bruising also speaks to ideas of collective black pain and how through sound and music we are able to respond or articulate the ungraspable. When it comes to sound and music Tavia Nyong'o argues that black sound studies demand that 'we listen to the black body as a musical and technical instrument that resound at frequencies that confound its routinized, racialized instrumentation'. T. Nyong'o, 'Afro-philo-sonic Fictions: Black Sound Studies after the Millennium, Small Axe, 18, 2, 2014, 174. McKittrick, in a similar fashion, echoes these ideas when she understands that black musical aesthetics provide subversive potentialities that becomes rebellious/ungraspable to 'the racial economy of white supremacy that denies black personhood'. K. McKittrick, 'Rebellion/ Invention/ Groove', Small Axe, 49, 9, 2016, 80.

84 J. Nancy, Listening (New York: Fordham University Press, 2007), 38. [ Links ]

85 Ibid..

86 McKittrick, 'Rebellion/ Invention/ Groove', 81.

87 Dalamba writes about the beer-sponsored music festivals during the time as violent spaces which 'were framed by strict legislation prohibiting mass gatherings by black people and were therefore closely policed'. See L. Dalamba, 'The Blue Notes: South African jazz and the limits of avant-garde solidarities in late 1960s London, Safundi, 20, 2, 2019, 222. Brett Pyper also notes the inability for these outdoor beer-sponsored festivals to be 'autonomous sites of urban black cultural expression in the face of apartheid legislation that saw musicians going into exile and the eventual demise of the Cold Castle Jazz Festival that came to an end in 1964 after a violent incident that left six men dead, See B. Pyper, 'Jazz Festivals and the Post-Apartheid Public Sphere: Historical Precedents and the Contemporary Limits of Freedom, the world of music, 5, 2016, 111.

88 Email communication with Max Annas, 12 May 2021. Max Annas was working on a project about the Blue Notes. As part of this, he video recorded various individuals who had played with individual members of the Blue Notes or who were musicians living in East London during the 1950s and 1960s. He also interviewed people who had great knowledge of the jazz music scenes of East London, Port Elizabeth, King William's Town and other towns in the Eastern Cape. Max Annas in this contemplation about the Pondo Blues song had invited saxophonist Mzoli Mdyaka who had played with Eric Nomvete as part of the African Quavers who was based in Mdantsane in East London; bassist from Queenstown Mlungisi Gegana, former jazz radio presenter, artist and historian Peter Makurube who came from Johannesburg; Patrick Pasha a jazz musician from Port Elizabeth and guitarist Bheki Khoza.

89 Andrew Mogridge, Max Annas, Bheki Khoza, Patrick Pasha, Mzoli Mdyaka, Peter Makurube, Mlungisi Gegana round table discussion, PB Tape 2 recap 2MPEG, University of Fort Hare, 2014.