Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Kronos

On-line version ISSN 2309-9585

Print version ISSN 0259-0190

Kronos vol.46 n.1 Cape Town Nov. 2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2309-9585/2020/v46a10

PART 2 REWORKINGS

Theorising the Image as Act: Reading the Social and Political in Images of the Rural Eastern Cape

Candice Steele

University of Fort Hare; https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6854-2904

ABSTRACT

Certain anthropological narratives of South Africa's Eastern Cape province, such as Monica Hunter's 1936 Reaction to Conquest and Philip Mayer's 1963 Townsmen or Tribesmen, persist as potent referential 'bodies of knowledge'. By laying down the coordinates of Black rural and urban experience, such studies continue to animate concepts of tradition and modernity, effectively conjuring up notions of 'the border', both literally and metaphorically. Encountering Pauline Ingle's photographic collection amidst these circuits of knowledge and ways of seeing is to recognise that it is both unusual and exceptional. It is a collection of over 4000 images that are not only located in a rural area but also covers a sustained time period, corresponding to the period of formal apartheid. The concept of the rural is amplified in the collection, positioning it as a site of development, as the 'not yet modern', in which subjects are figured both in class hierarchies and in relation to Daniel Morolong's urban photographs in and around East London in the 1950s. Employing the theory of social acts enables a re-contemplation of the subject, and a reading of the social that suggests a set of possibilities and futures beyond what currently constitutes the rural and the urban; and upturns the disciplinary optics that condition the predominating ethnographies and historiographies of the Eastern Cape.

The whole problem is born of the fact that we have come to the image with the idea of synthesis... The image is an act and not a thing.

- Jean-Paul Sartre, L'imagination

The Pauline Ingle Photographic Evaluation and Realisation Project

The Pauline Ingle Photographic Evaluation and Realisation Project (PIPER) collection comprises 4000 images, taken by amateur photographer Pauline Ingle,1 who worked as a missionary doctor in the former Transkei from 1948 to 1976.2 The collection (captioned, digitised and donated to the University of Fort Hare by her husband, Ronald Ingle) is a rare and significant archive given that so few collections cover a primarily rural context in South Africa over that time period. The photographs are located within the Transkei's broader visual economy, in which images of an essentially rural and idealised lifestyle predominate. To consider the photographs in the space of the rural is to summon a complex backdrop of constitutions and normative conceptions associated with the discourse of the rural.

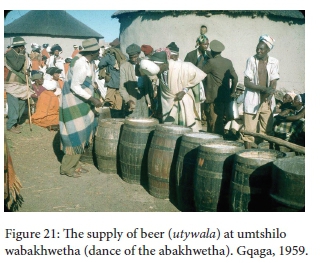

The politico-historical determinants of ethnicity as a construction in South Africa, and the attendant appropriation of the rural areas as naturalised geographical sites of ethnic and linguistic division, have made tradition and ritual a dominant trope of ethnographic encounters. Such encounters enclose cultural differences within geographical spaces, where the specificities of culture and material culture are understood to be inherent. This can be seen at work in photographs and publications by Alfred Martin Duggan-Cronin and Joan Broster3 as well as in paintings by Barbara Tyrell,4 which buttress the illusion of ethnic delineation and spatial designation, thereby configuring the rural as a placeholder for unchanging tradition.5 Their recurring images of rituals and tradition - intonjane (female initiation rites), amaqhira (traditional healers), and umtshilo wabakhwetha (male initiation rites) - become conventional signifying tropes of Xhosa culture in a discursive practice that parallels Donna Haraway's 'colonial-nostalgic-aesthetic'.6

In the genres constructed within the canon of art history, such photographs are categorised as ethnographic, and set apart from genres such as pictorialism or documentary. However, in the sense in which colonial-era and other photographs have been endowed with the negative attributes - for having aestheticised, objectified and inferiorised others as passive and lacking agency - and assumed under the epithet of ethnography, it is more challenging to readily impute Ingle's photographs in this way. Even if we accept that some of Ingle's photographs conform by presenting the rural through ritual observance and tradition, and that there might be parallels with tropes related to ritual and couched in a narrative of cultural origins as imaged by other photographers, discernible differences invite us to think about these photographs as distinctive. Of key importance is a biographical consideration: as an amateur photographer, whose primary role was that of a medical doctor, her visualisations are not those of an anthropologist on a fieldtrip, but rather of someone living in an area for a sustained period. In her curiosity to visualise and record daily life, her photographs suggest that she was not necessarily intending to mark difference or to constitute subjects in any particular way.

Unlike the approaches taken by Duggan-Cronin, Joseph Denfield, and later Leon Levson,7 under the rubric of 'native studies',8 Ingle did not stage re-enactments or restage photographs for a particular effect or to acquire knowledge. Rui Assubuji9 has argued that re-enactment or staging was a central method for anthropologist Monica Wilson, specifically in photographs she created of family life (but excluding those of ritual events) that she submitted for publication in Reaction to Conquest.10What Wilson arrived at in many of her photographic plates was a representation of the end stage of a negotiation between photographer and photographed, rather than a naturalistic event. In contrast, Ingle's main mode of photographing suggests opportunistic spontaneity, not the pursuit of contrived spectacle.

Her mode of photographing ritual events is strikingly spontaneous, and the pictures are taken as events unfold. The images are kinetic and show the natural movements, rhythms and gestures associated with the forms of the ritual as it is taking place. The photographs register that Ingle is ambulatory, walking in and among the crowd in very close proximity to her subjects. This suggests a different set of intended meanings. The photographs are not detached from the processual flow and are taken in a style that is candid and informal, unlike Broster's choreographed photographs,11in which her spectacularising aesthetic creates a palpable distancing effect. The composition and form of Ingle's photographs is neither invasive nor staged, and brings into concert the hospital, church and everyday lives of the people living in and around the mission hospital where she was based. The concatenation of these images, linking the hospital, church and the daily lives of people in a story of contiguous contemporaneity, allows for the possibility that the images of rituals can be read as being socially performative rather than as representing a temporally dislocated and idealised way of life.

Social Acts

Within Ingle's collection, a series of photographs show the renowned South African theatre director Barney Simon12 conducting drama-for-health education workshops with nurses at All Saints Hospital. The workshops were part of health-education projects with nurses at missionary hospitals in the Transkei, Winterveld and KwaZulu-Natal in the 1970s, and have been described as a response to the challenges posed by apartheid-created illiteracy.13 Ronald Ingle described how the workshops at All Saints, billed as 'awareness training', were aimed at breaking down barriers between professional nurses (with their overly didactic approach) and ordinary people, as well as to improve the nurses' understanding and sensitivity to people's circumstances.14The nurses were encouraged to 'take off their uniforms' and 'humanise' themselves, through exploring a greater awareness of themselves and others (Figures 1-4).

The borderland15 of education and status signalled by Ronald Ingle implies a class differentiation, made possible by the existence of the hospital and the church. The workshop photographs, through their representation of social categories, ostensibly and apparently amplify the dichotomy between tradition and modernity, as constituted by modernity's discourse.16 But it is the expression of theatrical acts made visible in the imagery that I wish to apprehend here as an apt metaphor for invoking the animating potential of the image as read through Jean-Paul Sartre's assertion that the 'image is an act'.17 Harnessing this to Hannah Arendt's notion of social acts as both 'governing' and 'beginning', Gary Minkley proposes that when social acts break given orders, practices and habitus, they register as both a rupture in what is taken as given and as a projection into another way of being able to read things.18 Social acts also inspire readings that do not follow a linear or coherent narrative - particularly, in the case of Ingle's images, along a modernist trajectory - but offer the possibility of reading a number of competing, convivial, conforming or non-conforming narratives at work.

First, an opening at the borderland of gender. Even if partially accepting that a certain corporeal habitus19 can be discerned in Ingle's images of women at work, arguably reproducing a series of continuities in narratives of the rural and reinforcing the notion that tradition is the backdrop against which gender divisions are played out, I wish to employ a subaltern sensibility here - a subtler appreciation of Brechtian gestus,20 in line with the evocation of social acts.

Kim Miller has convincingly posed a number of provocations against dominant representations of economically disadvantaged women, questioning whether visual culture can represent women as simultaneously poor and empowered - as able to address the realities of economic deprivation while also celebrating their ability to survive them.21 Following Miller's arguments (as read through the work of the Philani Project, a women's art co-operative in Crossroads, Cape Town), the depiction of women as 'nurturers and nourishers' in the face of difficult circumstances and limited resources can be read as an empowering physicalisation of the strength and dignity of food preparation. Such seemingly simple acts contribute to individual and community survival and reference the considerable agency that exists on the margins.22Figures 5-7 are highly suggestive of Miller's arguments.

Where colonial or ethnographic photographs essentialise and symbolically collectivise,23 Ingle appears to reach for a humanising and personalising aesthetic, implicative of a Western art sensibility and its concerns with anthroposcopy, which attempt to render the individuality and distinctiveness of a person accessible and knowable through portraiture. While this knowability may be a romanticised fiction,24it is still helpful to think of the ways in which portraits that focus on the dynamism and agency of individuals, highlight idiosyncratic details of self-presentation in terms of facial expression and individualist materialism. These contrast with and disrupt the conventions of the formal colonial portrait, in which rigid posture, impersonal detachment and an inferiorised gaze, which, when used for surveillance, form an integral part of an ethnographic image economy.25

Because of its association with, and investment in, concepts of individuality and the revelation of subjectivity, portraiture has largely been understood in traditional scholarship as a modern artistic genre.26 The same holds for photographic portraits, especially in African contexts where the portrait is widely assumed to be a modernising medium for representation. In the post-liberation era,27 for example, honorific and aspirant studio portraits signalling the production of self-determining urban subjectivities are a recurring theme. Given that the portrait is thought to be synonymous with the modern subject and its implications of the urban, portraits in the Ingle collection that reference tradition raise important questions around whether the portrait necessarily constitutes only a modern sense of individuality. This, in turn, raises a further set of questions around how to understand constructions of rural individuality, beyond the limits of an objectified other.

One possibility is to think about Simon Schama's suggestion that identity (and subjectivity) might be more openly revealed when subjects are caught in medias res.28Certainly one of the ways in which Ingle was photographing was in the processual flow, when not all subjects have time to 'compose' themselves for a photograph. Elizabeth Edwards has suggested the term 'presence' as illuminating the experience and points of view of both the photographer and the photographed, and as a moment of intersecting affect despite the asymmetry of the prevailing relations.29 Edwards also offers presence as an alternative to the concept of agency, which reaches beyond the curtailment of the subject of a gaze displaying intentionality, and introduces the possibility of reading emotion and embodiment and the experience of being 'a someone'. In this sense, 'presence within the trace of a photograph is profoundly subjective and profoundly personal, a reclaiming of a moment'.30 In essence, Edwards' argument is for affective evidence, as against what she terms the 'unproblematised evidence' that has so far shaped the making of disciplinary knowledge, particularly in anthropology.

In Figure 8, a smiling woman appears to be walking away from the Outpatient Department at All Saints Hospital. She carries two neatly swaddled geese on her head, restraining them for their onward journey and future purpose. Her body and one goose cast a shadow on the wall, reminiscent of shadow puppetry's dramatic storytelling, and revealing the woman's inventiveness and resourcefulness. In the same way as Chinese shadow plays incorporate the traditional and contemporary in their dramatisations and function to illuminate the past, present and future, we can imagine this woman as positioned in a liminal space, in which the future holds different possibilities. In terms of representation, she subscribes to neither a reading of universal humanity nor of simple tradition; that is, the image need not be read as perpetuating the stereotype of poor and marginal peasant women fading into ever-increasing poverty and overly reliant on the migrant labour system.

Similarly, Figure 9, which shows members of the Mothers' Union after a meeting, is reminiscent of the pictorial style of photography used by Joseph Denfield on his expeditions in Basutoland.31 While Ingle's photograph can be read as documentary in its intentions, a lyrical aesthetic is at work in the way in which the hilly and mountainous landscape forms an expansive backdrop to the women, who are placed in the right-hand corner of the photograph. The determined strides of the women evoke a sense of movement across the photograph, suggestive of facing the future with undaunted purpose and resolution.

Indeterminate Futures

However indeterminate their futures might have been, Bernard Stiegler's concept of transindividuation is useful here. Stiegler posits the possibility of a future predicated on a set of processes in which personal and collective individuations transform one another over time, thus forming the basis of social transformation.32 Irit Rogoff articulates Stiegler's concept as follows:

The concept of 'transindividuation' is one that does not rest with the individuated 'I' or with the interindividuated 'We', but is the process of co-individuation within a preindividuated milieu and in which both the 'I' and the 'We' are transformed through one another. Transindividuation, then, is the basis for all social transformation.33

Similarly, the possibility of indeterminate futures resonates with Elizabeth Grosz's conceptualisation of a future unconstrained by the determinants of the past. Writing in the register of a feminist historian, Grosz deploys Luce Irigaray's temporalisation of the future anterior, articulating this as 'what will have been, what the past and present will have been in light of a future that is possible only because of them'.34 What the future anterior enables is a different and retrospective reading of the rural - a counter to the stereotypes and meanings configured and imposed by the colonial/apartheid complex, which represented this space as a site of ever-diminishing prospects yoked to gender. Such a reading gives rise to what Grosz termed the need for the specificity and particularity of writing a history that is not repeatable or generalisable, and that 'welcomes the surprise of the future'.35

Grosz's argument is that history should be about the production of conceivable futures from the vantage point of the present, where the future is unpredictable and unconstrained by the present. Similarly, in this reading, the past is not given, and can be subject to a multitude of interpretations that allow for the performativities and continuities of the rural to be apprehended, as well as for potential ruptures and new possibilities to be discerned. In this sense a degree of congruity exists between Grosz's ideas and the notion of social acts, as signalling not only a rupture in the commonplace, but also a beginning.

And yet, without diminishing the enormous contribution of subaltern studies in working with power and agency on the peripheries, and thinking with Edwards,36 who acknowledges the importance of agency as part of a politics of return, I would like to propose thinking about Ingle's images as social acts. Conceiving of each image as an act in itself enables us to unseat the reflex of looking for agency as the 'go-to' counter-hegemonic corrective in visual culture and to read for additional possibilities.

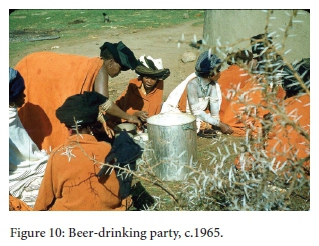

The photograph of a beer-drinking party held in the mid 1960s (Figure 10) frames a group that colloquial ethnographic parlance would describe as abantu abomvu or 'Red' women. The group seem unaware or indifferent to the photographer. Yet, there is a tangible sense of an organised and ordered sociality, a ritual of purposeful sharing and togetherness. Again, individual status and organisation are alluded to, as against ethnographic notions of implicit collective subjectivities engaged in unconstructive and mindless pursuits that have conventionally been applied to photographs denoting type.

The enduring narrative of abantu abomvu ('Red') and abantu basesikolweni ('School') identity politics, prevalent in publications such as Philip Mayer's Townsmen or Tribesmen,37has arguably given rise to many of the stereotypical visualisations of the Transkei, which continue to circulate in tourist postcards, websites and coffee-table books. Taking a cue from Archie Mafeje,38 who argued that these identities were much more fluid than Mayer and others described them, many photographs in the PIPER Collection challenge this polarisation in their characterisation of social acts.

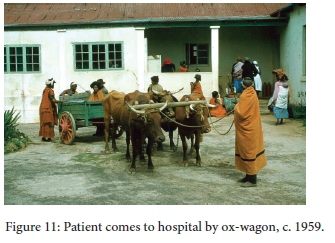

In Figure 11, for example, the arrival of a patient in an ox-wagon at the hospital, dressed in the red ochre clothing stereotypically associated with adherence to tradition and a rejection of modernity, provides both a picturesque spectacle and a fracture in the institutionalised meanings of tradition and modernity in a rural setting. As a site of modern medical intervention, the hospital itself calls into question notions of what constitutes the rural, as well as the rigid binaries imposed on the identities of those known as 'Red' and 'School'.

The meanings often attributed to 'Red' - as incorporating a distinctive set of values based on the interpretation of ancestor directives that eschew modernity and Christianity (as its instrumental mechanism) in particular - are somewhat dislocated in this photograph. These assemblages of meaning, set up as stereotypical markers of an unchanging Xhosa culture, are undercut by a 'Red' patient presumably seeking (modern) medical treatment. The presence of other people, not clothed in 'Red' attire, further disrupts any attempt to essentialise Xhosa identity; the photograph temporally resists what Lorena Rizzo termed 'inscriptions of a historical past'.39 There is a sense that the photograph was taken for its overall aesthetic sensibilities, rather than capturing some cultural fundamental. The colour contrasts formed by the red ochre against the stark white walls, the geometry of the in-spanned oxen's horns, and the green and red-spoked wagon, which provides a palanquinesque carriage for the patient, all form a strikingly evocative image set against the soberness of the hospital.

Figure 12 was created inside the hospital. It is a black and white photograph, bearing the implication of the documentary genre. Two babies are lying on a table receiving a scalp transfusion for diarrhoea, while their mothers sit alongside them, forming the central focus of the photograph. The drip-stand seems to provide an expedient visual metaphor for the boundary between the two mothers. One, as the caption tells us, is dressed in 'Western' clothes and the other in the traditional clothing associated with the 'Red' people.

Yet by applying Edward's notion of presence,40 it is clear that the two mothers are unified by their worried expressions of protective maternal responsibility. They are together exercising choice not only in accessing the services of the hospital, but also in registering their antipathy to being the subjects of an intrusive documentary gaze, albeit in different gestures - one perhaps with disdain, the other perhaps with aversion. Whatever borderland might be projected onto the relationship between tradition and modernity, it is undercut here by a broader set of affective imperatives, played out through the shared subjectivity of motherhood.

The third photograph (Figure 13), taken in the context of the dedication of a new church, further challenges the essentialised identities ascribed to 'Red' and 'School'.

People dressed in the 'Red' style intermingle with parishioners in more modern dress and members of the clergy as the dedication ceremony gets under way. The photograph seems to suggest a mutability and dynamism across and between these supposedly fixed cultural divides, and further suggests a sense of communitas, perhaps made possible by this ritual, and superseding the widely believed incommensurability of these overdetermined categories.41

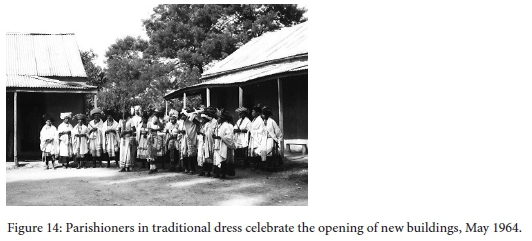

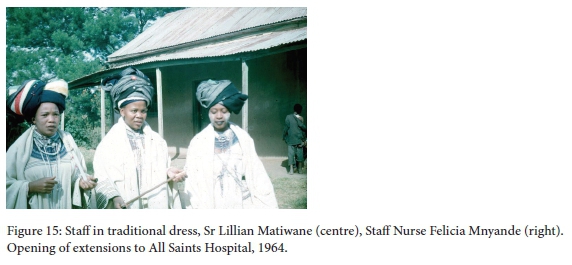

Tradition and Modernity

An interesting inversion on the theme of the borderland between tradition and modernity is the photograph of a group of people dressed in traditional clothing at an event (Figure 14). Without deploying James Hevia's 'photography complex'42 to interrogate photographic representation and its ideological underpinnings, viewers might be seduced into believing that what we see is a stereotyped rendition of some kind of traditional ritual. However, the caption reveals that the people are 'Parishioners in traditional dress celebrat[ing] the opening of new buildings, May 1964' at the hospital. Interestingly, the man to the right of centre in the photograph is Abel Somana, who according to other records in the PIPER archive was both a church warden at All Saints and a renowned imbongi (praise singer). Also, many of the parishioners in this photograph were nurses at All Saints Hospital, as imaged in other photographs from this occasion (see Figure 15).

In disrupting the purported irreconcilability between tradition and modernity, these photographs spark two trajectories of thought. One works against this stasis, as neatly stated by Lize von Roebbroeck:

Tradition and modernity must thus be re-imagined as a continuum rather than a break - a continuum, moreover, that is not imagined as the gradual transmutation of one into the other, but as a web of constant exchange and cross-infusion that manifests as a rich broth in which empowerment and dispossession are hardly distinguishable from one another. This continuum, if scrutinized closely enough, will eventually render tradition and modernity the same, so that the dialectic can, for once and for all, be dispensed with to make way for a nuanced and always-already complex present.43

The other requires returning with the nurses to the hospital setting, to locate a set of discursive framings that further illuminate the assemblage of the social as seen by Ingle. In thinking with the idea that photographs are acts which constitute the social, the demarcated borderland between the rural and its associations with tradition, versus the urban and its associations of modernity, can be further complicated when viewing photographs by Daniel Morolong of nurses at a hospital in the coastal town of East London, just over 200 kilometres south of All Saints Mission.

Photography of Daniel Morolong

Morolong was a photographer from East London whose images are associated with revealing everyday township life from the 1950s to the 1970s. Morolong's collection presents a vibrant sociality, constellated around music, sports and other social events, as well as major life milestones, such as graduations, weddings and funerals (see Figures 16-18).

It is possible that this is why the Morolong collection was categorised as 'vernacular photography'.44 As a growing genre, vernacular photography seemingly incorporates the condition of the commonplace - everyday subjects, taken by amateurs, outside the bounds of the fine art establishment. As Gómez points out, it is everybody's photography.45 However, from a collecting perspective, vernacular photography is still coming to terms with its own definition and trying to accommodate the wide-ranging diversity of material included - from family snapshots and travel photographs to group portraits and identification photographs. Perhaps surprisingly, it can also include iconic news pictures and commercial portraiture and product imagery. Gómez elaborates:

It designates that which is common and familiar enough to have, in effect, become a recognizable, definitive form in its own right in a particular field, an enduring, generic form of creative expression that is as much a reflection of the culture of a specific people or place as it is a defining aspect of the cultural environment of a particular people and the region they call home.46

In this vein, and circling around the connotation of vernacular in South Africa as meaning indigenous, the term 'vernacular photography' appears to have been conceptually appropriated here to refer specifically to Black photographers. Further, as South African photographer Paul Weinberg demonstrates in The Other Camera, an exhibition he curated in 2014, the term has a particular conflation with those designated as street photographers. Taking its cue from the 'standpoint of community and participatory photographers',47 the exhibition asks critical questions about representation as expressed through street photography. In pursuing his interest in how 'indigenous' photographers depict their own environment, culture and fellow citizens, as against historical and dominant afro-romantic or afro-pessimistic visual portrayals, Weinberg included a selection of images by Morolong and others in The Other Camera48The exhibition was created in a deliberate attempt to provide an 'insider perspective', and to show how Africans represent themselves in what Weinberg termed 'indigenous media'.

In situating the exhibition in the domestic realm - 'the vernacular' - we are asked to consider the photographs as set against and beyond the defining and dominating narrative of the apartheid state. However, these images are also often seen as potentially disassociated from the struggle-documentary genre of the time, with its more oppositional and confronting imagery offering a direct critique of apartheid. For Morolong and most of the other photographers featured in the exhibition,49 this meant considering alternatives to the depersonalising and repressive narratives and images associated with the apartheid state.

Weinberg's construal of 'the other', particularly in terms of Morolong's representation of township life, is about revealing social lives that apartheid, and by extension 'whiteness', wanted to deny and keep hidden.50 For him, these photographs provide an apt illustration of how residents viewed their location - in contradistinction to state-driven public perceptions - as sites of permanence and social life as against the notion of the temporary migrant and worker. It is instructive here to quote from the description of Morolong's images in the University of Cape Town's digital collection:51

Daniel Morolong's photographs tell the 'other' story of life in the black urban residential areas of the city, at a time when apartheid's political agendas were beginning to unfold. The authorities and the residents of East London's locations have always seen and understood the locations differently. To the authorities, they were overcrowded and filthy, a breeding ground for poverty, disease and crime. These conditions were seen to reflect the characters of people - somehow less than human. Racist images of people and the locations dominated public life. These photographs on [sic] show how residents saw the locations. They portray life in the locations as rich, dynamic and vibrant. In an extraordinary way they show the very ordinary nature of social life and living and therefore picture aspects of life that apartheid denied and 'whiteness' kept hidden. Despite a long list of artificial restrictions imposed by apartheid on their lives, location residents made their own definitions of what it really meant to be 'the other' in white South Africa. As such, when they remember their lives in these old locations, it is neither the poverty nor the hardship that they remember most. Rather, it is the social diversity, cultural vibrancy and sense of identity that first come to mind.

The 'somehow less than human' characterisation provides a useful point of departure for a number of problematic issues. In the choice of Morolong photographs for the exhibition, Weinberg is very intentionally marshalling the images as irrepressibly representing the human, figured as the universal individual, rational sovereign subject, who is emblematic of urbane modernity, but who perforce occupies an alternative modernity only by virtue of a restrictive politics. I contend that this framing of the human, purposefully read through a 'vernacular' genre, is a liberal construction of the human, an apologist stance attempting to counter the 'volkekunde'52 mentality insinuated in mainstream socio-politics and its attendant discourses, particularly the native question.

In The Other Camera, Weinberg draws attention to Morolong's celebration of the body in the choice of photographs for exhibition. However, the antecedent Underexposed project53 (also facilitated by Weinberg in collaboration with Duke University, which showcased 11 relatively unknown South African documentary photographers, and for which a much larger archive of Morolong's work was digitised) provides the grounds for the antidotal and justificatory reflex that locates the subjects in Morolong's photographs as universally human despite the racially coded society that they inhabit. Images such as the woman listening to a radio in a sitting room, of outings to the beach in motor cars, and snapshots at the train station are visual enablers of a liberal construction of the human that normalises the Western rational, individual subject. Invoking this coeval (alternative) modernity,54read through a cultural relativism, seems only to reinforce the 'not yet human' status ascribed to tradition, as outside of modernity, that may obtain in discursive formations of the rural.

The similarities and visual homologies in Ingle's and Morolong's photographs of nurses (Figures 19 and 20) and, ultimately, the inability to tell the difference between them, incites the question of whether a further false binary between what is constructed as the urban and the rural is at play. It also raises the question of whether the construction of the notion of an alternative modernity, through referencing the hegemony of modernity and the liberal subject, undermines an understanding of the complexity of the rural as a lived experience, because of its inability to explain or account for a humanity represented in other photographs in the Ingle collection that do not fit these categorisations.

Ingle's portraiture, for example, encompasses what might be read as ethnographic, but it also includes portraits of doctors, nurses, hospital staff, clergy and an array of people engaged in ordinary activities and special ceremonies. The documentary impulse, evident in photographs of children in the hospital, as well as the gesturing towards social definition in the portrait photographs, complicates any unified notion of what constitutes a rural photograph.

It is perhaps fitting here to reference Anitra Nettleton's argument that African modernity is based in African history as much as it is in Western modernity, but this does not mean that, to be "African", this modern identity must always be referred back to a primitivist paradigm [or 'authenticity discourse']'.55 As Minkley explains, Nettleton showed that African subjects of colonial power or apartheid 'logics' acquired a modernity that qualified them for 'civilised status':

This modernity ..was rooted in the epistemological and linguistic apparatus, if not by the ontological underpinnings of Western society as offered, first by the missionary, and later, by state educational institutions. Such modernity was opposed to the supposed 'primitiveness' of 'authentic', 'indigenous African cultures', but also, ironically, set these in place, as the space of the traditional and the indigenous.56

Notwithstanding the problems of constructing an alternative modernity,57 the nurses photographed by Ingle do provide a clue to the liberal impulse at work. In the context of a narrative of medicalisation, and following James Hevia's contention that, as an apparatus of action and intervention, photography goes beyond mere documenting by staging and fixing an ideological stance,58 we can apprehend that Ingle's photography of the hospital constitutes both a liberal documentary mode and a valorisation of the modern Western human subject.

Arguably some of Ingle's photographs share an archival resonance with other kinds of colonial and missionary photography,59 which, as Marianne Gullestad points out, exhibit similar repertoires of subject matter.60 These include not only scenes drawn from a narrative of medicalisation - medical work, training, buildings, etc. -but also the ways in which new social categories are created and made visible by the hospital and the church. The same can be appreciated in mission photographs, which document evangelical activities in and around the church and the hospital, and allude to new social hierarchies. In this sense, Ingle's photographs are stereotypical in visualising modernity through a series of liberal discourses and, in so doing, constituting the liberal subject, much like Morolong.

While accepting that Pauline Ingle was taking photographs mainly to document her own experiences for personal reminiscence, the fact that she submitted some photographs for various fundraising efforts suggests that she was conscious that certain images could be utilised to elicit support for developmental relief. The subtext to the documentary impulses in these photographs points to a conceptualisation of development in which the underlying circumstances that prevent people from living in the conditions of the modern human subject are highlighted, while at the same time the presence of the hospital and the church is seen as instrumental in addressing this problem.

If the photography complex is functioning here to assert a stereotypical liberal custodianship, founded on ideas of nurturing and improvement, it is also important to attend to other aspects of the complex, in which the participation of the camera outside the framework of White trusteeship - the hospital and church - appears to affirm the Christian ideology of the universal equality of all people before God.61 On one hand, Ingle can be read as offering a different visualisation of people in the rural areas through her humanising gestures of proximity and familiarity, and in ways that unsettle the ethnographic genre. This may be suggestive of an attempt to frame people as similar, particularly through a visual appreciation of individuality. However, this positioning of people as essentially similar, as mediated by the interventions of hospital and church, can also be read as problematic in its assumptions about the universality and normativity of the liberal subject.62

Reading Human Rights

However, if we harness the idea of equality and view it as setting a potential agenda for human rights, that in turn invites a reading of human rights in Ingle's imagery. To be concerned with rights is to recognise that self-determination, itself a political principle enshrined in the United Nations Charter of 1945, is the basis of the discourse and is descriptive of acts that are not undertaken through force or compulsion but are self-directed. Ingle's photographs of the everyday provide a reading of self-determination and autonomy, registered through images of people exercising control over their own lives, taking care of their own needs and acting in their own self-interests through the routines and repertoires that configure their social existence.63For example, in Figure 21, we might recognise a vision of freedom of assembly and the (self-determining) right to freely participate in the life of the community, rather than arrive at an anthropological reading of the sociality and structure of a beer-drinking party, in which the impulse to mark out social categories and hierarchies might be foremost. The blanket intruding into the left-hand corner of the photograph echoes earlier arguments about the snapshot nature of Ingle's photography and further undermines any notion of an ethnographic agenda at work. However, the barrels of beer are the only signifiers of intentional arrangement as they form a line of orderly intersection across the photograph. The mishmash of different styles of apparel and the spontaneous free-flowing movement of people across the image suggest a difficulty with reading through a lens of ritual and tradition. Despite the presence of a figure dressed in what appears to be a police uniform as a signifier of state authority, the fluidity in this photograph has flattened out the lines of power, making such assemblages difficult to determine.

I therefore want to return to Ronald Ingle's characterisation of Pauline's mode of photographing, as taking 'what was going on'.64 Her interest in the quotidian and her spontaneous mode of taking photographs is suggestive of snapshots, rather than highly staged or stylised image-making. Everyday snapshots are evocative of a family photograph album, characterised by the intimate and familiar. Following Laura Wexler's provocation of using the 'state of the album' as a means of reflecting on the meaning of state power, Wexler posits the 'state of the album' as 'a double entendre: it signifies both the album's condition and the image of the state that the album reflects or projects'. She proposes the use of family photograph albums as records that conserve and reflect the meanings of state power, but also contends that family albums are contingent upon and secured by the 'optics of governmentality'.65

With the state in mind, I am interested in thinking about the political context of the Transkei in the 1960s, and in Pauline Ingle's emplacement not only within the particular political terrain of liberalism but also more widely within what Fred Cooper calls the 'about of politics' in this moment of decolonisation. Cooper suggests that the 'about of politics' is how individuals and organisations get people to do things they did not think they wanted to do, and how the concepts of politics - citizenship, nation, state and sovereignty - are deployed in these political actions.66 As he points out, politics takes many forms. It is worth pausing to consider what might have been mutually intelligible as its desired form for Pauline (and Ronald) Ingle, and to think about how the 'about' of this politics might translate, literally as art, into her photographic images. Put differently, can we read these photographs as images of citizenship?67

Against the background of decolonisation, and moves towards independence on the African continent in the 1950s, as well as against the spectre of the impending 'independence' of the Transkei as a self-governing territory, Randolph Vigne characterises parts of the Transkei in 1960 - particularly the Engcobo district - as 'seething with discontent' at the Bantu Authorities System; heretofore, the area had been considered 'a political wasteland'.68

Albeit problematic in its characterisation of docility and other assumptions, Vigne's account is a useful point of departure for thinking about how the political subject becomes a citizen-subject through an underlying political discourse of the 'right to have rights' that mobilises a prospective citizen in the territory of the Transkei.69 Vigne's dossier-like approach detailed a set of activities and political modes of operation that included envoys, meetings, gatherings and addresses that instantiated the politics of citizenship, and provided a political register that countered narratives of rurality or tradition encapsulated in the notion of a 'wasteland. This political register enables the recognition of a visual register within the Ingle archive, through photographs of assembly and interaction, where a different expectation of collectivity is imagined, as against explanations of ritual and tradition.

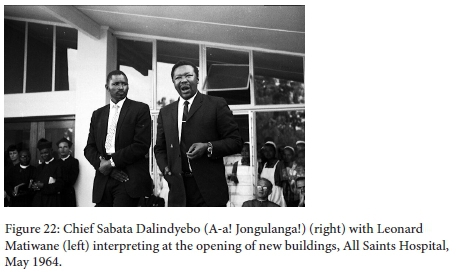

The picture of Chief Sabata Dalindyebo (Figure 22) addressing the audience at the opening of new buildings at the All Saints Hospital is a key moment where the politics of citizenry emerges in the archive. Political leaders are beginning to be seen as against other leaders at the mission station, such as priests or doctors. The appearance of the political figure has the potential to refigure these other roles as political, but also potentially to frame the discontent described by Vigne as countervailing the genres of photography that have constituted the 'wasteland'.

In embracing a reading of rights, I follow Isin and Nielsen's theorisation of acts of citizenship.70 These authors propose an engagement with the concept of citizenship that shifts it from being an institution located in an individual agent into collective or individual acts that rupture social-historical patterns, and in so doing, anticipate rejoinders from an imaginary adversary. Conceptualising acts of citizenship as simultaneously a break from an already-held status and embedded practice, and as a fundamental way of being with others, inaugurates ways of being that are political, ethical and aesthetic.

Acts of citizenship create a sense of the possible and of a citizenship that is 'yet to come'; they are acts which produce new subjects. These acts, while not necessarily ethical, make implicit a sense of a future responsibility towards others.71 This enables us to think of Ingle's photographs of rituals, for example, as making visible the ways in which rituals are setting up a template of subjectivity, a prefiguration of the 'yet to come' that incorporates a future responsibility that is unconstrained by notions of indigenous belonging or citizenship within a nationalist discourse. When subjects constitute themselves as citizens, regardless of status or substance, they instantiate themselves as those to 'whom the right to have rights is due'. As Engin F. Isin (recalling Jacques Rancière) observes, it is when one enacts 'the rights that one does not have' that one becomes a political subject.72

So, marshalling the acts of citizenship that enable a reading of these photographs as being of rights-bearing citizens disaffirms the discourse of the 'native subject' as a less-than-human set of constitutions, and posits instead a set of possibilities relating to the legibility of the human,73 and gesturing towards the 'democracy that is to come' but on its own terms. Thinking deliberately with acts of citizenship is not to deny the backdrop of spatial segregation and the construction of ethnicity as embodied in the configuration of the geographical artifice of the Bantustans. Nor is it an attempt to gloss over or diminish the ramifications of 'the bifurcated state',74 around which enduring debates concerning tradition and modernity coalesce. Rather, this approach takes these discursive contexts as given, but explores the interstices in the switchbacks between stereotypes and acts that enable a reading beyond historical subject formations, particularly as these pertain to visual subjects in a rural setting. Tracking acts of citizenship allows for a reading of acts which suggest the kinds of activities that are undertaken as citizen subjects in these societies, as against readings that posit these acts as traditional, ritualistic or culturally determined.

1 Pauline Ingle was born in Port Elizabeth in 1915 and trained as a doctor at the Royal Free Hospital School of Medicine in London. At the time, this was a training institution for women doctors only, many of whom, like Ingle, became mission doctors in the British colonies. After completing a postgraduate course in surgery, Ingle returned to South Africa in 1948. She was initially stationed at the Holy Cross Hospital in Flagstaff, and then the Clydesdale Mission in Umzimkulu before being transferred to the All Saints Hospital at Engcobo in 1953. Here she worked single-handedly as the medical superintendent until 1958, when she was joined by Dr Ronald Ingle whom she married in 1960. Although she was involved in all aspects of the hospital, she focused on obstetrics and staff health. After a childhood bout of measles which left her deaf, she took up photography and it became a lifelong hobby. Her diverse collection, using Leica M3 and M4 cameras, was created over the 28 years she spent in the former Transkei, primarily at the All Saints Hospital.

2 Financial assistance from the National Research Foundation (NRF) and the SARChI Chair in Social Change, University of Fort Hare, towards this research is hereby acknowledged. Opinions expressed and conclusions arrived at are those of the author and not necessarily attributable to the NRF or the SARChI Chair. The author is grateful to the National Heritage and Cultural Studies Centre (NAHECS), University of Fort Hare, for permission to publish Pauline Ingle's photographs. Daniel Morolong's photographs are published courtesy of the Fort Hare Institute of Social and Economic Research (FHISER).

3 M. Godby, Alfred Martin Duggan-Cronin's Photographs for The Bantu Tribes of South Africa (1928-1954): The Construction of an Ambiguous Idyll, Kronos, 36, 2010, 54-83; J. Broster, The Tembu: Their Beadwork, Songs and Dances (Cape Town: Purnell, 1976), Author's Note.

4 L. Pollak, 'Tyrell and the Quest for the "Unfathomable"", Art Times, April 2012. [ Links ]

5 The native subject is a conceptual site of multiple discourses, all of which signal difference. In its broadest articulation, it is mobilised to denote the 'not yet modern' subject, who personifies tradition. As against this background and in the parsing of the native subject through the attendant genre of native studies, the native subject becomes the central concern of salvage ethnography, in its objectification and aestheticisation of the native body and lifeways. I am also concerned with the concept of the native subject in the South African context, and how it has been used on one hand to valorise the construction of ethnicities under apartheid, but also to secure the visualisation of the discourse of racial segregation. As Suren Pillay asserts, 'The designation of Native was not only a descriptive one, but also a legal one: to be classified as Native was to have spatially circumscribed implications in relation to movement and particularly regarding land ownership, employment opportunities and land tenure practices.' See S. Pillay, 'Where Do You Belong? Natives, Foreigners and Apartheid South Africa', African Identities, 2, 2, 2004, 215-32.

6 D. Haraway, Primate Visions: Gender, Race and Nature in the World of Modern Science (New York: Routledge, 1989), 267. [ Links ]

7 Godby, Alfred Martin Duggan-Cronin's Photographs'; see also P. Mnyaka, 'Re-tracing Representations and Identities in Twentieth-Century South African and African Photography: Joseph Denfield, Regimes of Seeing and Alternative Visual Histories' (PhD thesis, University of Fort Hare, 2012) and G. Minkley and C. Rassool, 'Photography with a Difference: Leon Levson's Camera Studies and Photographic Exhibitions of Native Life in South Africa 1947-1950, Kronos, 31, 2005, 209.

8 The 'native type' paradigm has been a chief element of the subject matter of ethnographers and amateur photographers on the African continent since the nineteenth century, when photography began to be used for scientific, commercial and aesthetic purposes. See D. Newbury, Defiant Images: Photography and Apartheid South Africa (Pretoria: UNISA Press, 2009).

9 R. Assubuji, 'Anthropology and Fieldwork Photography: Monica Hunter Wilson's Photographs in Pondoland and BuNyakyusa, 1931-1938' (MA thesis, University of the Western Cape, 2010).

10 Reaction to Conquest is an ethnography that traverses the urban and the rural, and concerns itself with the impact of urbanisation and social change from the standpoint of the countryside in relation to East London.

11 J. Broster, Red Blanket Valley (Johannesburg: Keartland, 1967). [ Links ]

12 Barney Simon was the artistic director and co-founder of the Market Theatre. See I. Stephanou and L. Henriques, The World in an Orange (Johannesburg: Jacana, 2005).

13 R. Colman, 'The Significance of Barney Simon's Theatre-Making Methodology on How and Why I Make Theatre: An Auto-Ethnographic Practice as Research' (MA thesis, University of the Witwatersrand, 2014).

14 Interview with Ronald Ingle, Durban, November 2012.

15 Here I am following Renato Rosaldo's formulation of 'social borders' which 'frequently become salient around such lines as sexual orientation, gender, class, race, ethnicity, nationality, age, dress, politics, food, or taste'. R. Rosaldo, Culture and Truth: The Remaking of Social Analysis (Boston: Beacon Press, 1989), 208.

16 By modernity's discourse, I mean the ways in which subjects impacted by colonialism and empire are constrained by a racial paradigm that can be read only through the lens of modernity. That is, the constructs of tradition and modernity corral (native and liberal) subjects into positions that foreclose the possibility of reading the human in multiple, hybrid and creative ways.

17 J.-P. Sartre, L'imagination (1936), quoted in G. Didi-Huberman, Images in Spite of All: Four Photographs from Auschwitz, S.B. Lillis (trans.) (Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 2008), 50.

18 H. Arendt, The Human Condition (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1958), 177; G. Minkley, 'Social Acts and Projections of Change', Professorial Inaugural Lecture, Miriam Makeba Hall, University of Fort Hare, 13 May 2014.

19 E. Österlind, 'Acting out of Habits: Can Theatre of the Oppressed Promote Change? Boal's Theatre Methods in Relation to Bourdieu's Concept of Habitus', Journal of Applied Theatre and Performance, 13, 1, 2008, 73.

20 Ibid., 72. I use the term to denote how gestures or physicality can capture an attitude or particular moment.

21 Miller notes: 'There are two primary ways impoverished women are represented within the well-established iconography of poverty. One romanticizes the conditions of female poverty, trivializing the harsh and often very desperate realities of daily life. The other presents poor women as deviant victims devoid of agency or power and deserving of their circumstances' K. Miller, 'Iconographies of Gender, Poverty, and Power in Contemporary South African Visual Culture', NWSA Journal, 19, 1, 2007, 118.

22 Ibid., 129.

23 E. Edwards, 'Photographic "Types": The Pursuit of Method, Visual Anthropology, 3, 2, 1990, 241. Edwards shows how the generalising anonymity of 'the type, characteristic of ethnographic photography, subsumes individuality and is its antithesis.

24 J. Borgatti, 'Likeness or Not: Musings on Portraiture in Canonical African Art and its Implications for African Portrait Photography, in J. Peffer and E.L. Cameron (eds), Portraiture and Photography in Africa (Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 2013), 319.

25 As Appadurai put it, 'this ethnological contextualisation of "natives" is behind the imperial eye of the photographer, and whether or not the purpose of a particular photograph is scientific or official, the point of view is decidedly classificatory, taxonomic, penal and somatic'. A. Appadurai, 'The Colonial Backdrop', Afterimage, 24, 5, 1997, 4-7.

26 S. Perkinson, 'Rethinking the Origins of Portraiture', Gesta, 46, 2, 2007, 135.

27 J. Peffer, 'Introduction: The Study of Photographic Portraiture in Africa', in J. Peffer and E.L. Cameron (eds), Portraiture and Photography in Africa (Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 2013), 21.

28 Cited in C. Freeland, 'Portraits in Painting and Photography, Philosophical Studies, 135, 1, 2007, 95-109. 99 See also, S. Schama, Rembrandt's Eyes (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1999), 472.

29 E. Edwards, Anthropology and Photography: A Long History of Knowledge and Affect, Photographies, 8, 3, 2015, 235-54.

30 Ibid., 241. Edwards notes the validity of the exercise of reading agency in many recuperative attempts in the politics of return, but she also cautions against its overuse as an analytical tool and its conceptual reification, particularly in instances where people are denied agency through incarceration, but are still able to mark their lived experience through the notion of presence.

31 Mnyaka, 'Re-tracing Representations', 81-106.

32 S. Bailey, 'Work in Progress: Form as a Way of Thinking' (PhD thesis, University of Reading, 2014).

33 B. Stiegler and I. Rogoff, 'Transindividuation', e-flux journal, 14 March 2010, https://www.e-flux.com/journal/14/61314/transindividuation/ (accessed 30 November 2020).

34 E. Grosz, 'Histories of a Feminist Future', Signs 25, 4, 2000, 1020.

35 Ibid., 1018.

36 Edwards, 'Anthropology and Photography.

37 P. Mayer, Townsmen or Tribesmen: Conservatism and the Process of Urbanisation in a South African City (Cape Town: Oxford University Press, 1961).

38 A. Mafeje, 'Leadership and Change: A Study of Two South African Peasant Communities' (MA thesis, University of Cape Town, 1963), 178-82.

39 L. Rizzo, 'A Glance into the Camera: Gendered Visions of Historical Photographs in Kaoko (North Western Namibia), in P. Hayes (ed), 'Visual Genders, Visual Histories', special issue, Gender and History, 17, 3, 2005, 693.

40 Edwards, 'Anthropology and Photography'.

41 V. Turner, 'Liminality and Communitas', in H. Bial (ed), The Performance Studies Reader (New York and London: Routledge, 2004), 79-87.

42 J.L. Hevia, 'The Photography Complex: Exposing Boxer-Era China (1900-1901), Making Civilization', in R.C. Morris (ed), Photographies East: The Camera and its Histories in East and Southeast Asia (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2009), 79-119.

43 L. van Roebbroeck, 'Beyond the Tradition/Modernity Dialectic, Cultural Studies, 22, 2, 2008, 228.

44 See C. McNulty, 'A Visual Past in East London: The Photography of Daniel Morolong (1950-1970)' (MA thesis, University of Fort Hare, 2013), 95; P. Weinberg, 'Introduction: Images from the Inside, in The Other Camera, exhibition catalogue, Institute for the Humanities, University of Michigan, 2014.

45 E.M. Gómez, 'Everybody's Photography', in Accidental Mysteries: Extraordinary Vernacular Photographs from the Collections of John and Teenuh Foster (Memphis: Art Museum of the University of Memphis, 2005). Exhibition catalogue.

46 Ibid.

47 Weinberg, 'Introduction: Images from the Inside'.

48 The Morolong collection of prints and digitised images is stored at the University of Fort Hare. However, the selection of Morolong's images used for The Other Camera are from the University of Cape Town's digital collection, www.digitalcollections.lib.uct.ac.za/daniel-morolong.

49 Some of the other photographers are Ronald Ngilima, Bobson Sukhdeo Mohanlall, Lucky Sipho Khoza and Lindeka Qampi.

50 Weinberg, 'Introduction: Images from the Inside'.

51 See www.digitalcollections.lib.uct.ac.za/daniel-morolong.

52 The 'volkekundiges' were a group of South African anthropologists who were active in the 1950s and who were acutely attuned to an overtly ethnological orientation understood through the notion of the volk (nation). They were influential in the complex intertwining of ethnology and display that have characterised the authority of museums and the representation of static culture in South Africa; see S. Jackson and S. Robins, 'Miscast: The Place of the Museum in Negotiating the Bushman Past and Present', Critical Arts: South-North Cultural and Media Studies, 13, 1, 1999, 69-101; and Pillay, 'Where Do You Belong?'

53 Underexposed is a photographic collection in the Islandora Repository, UCT Libraries Digital Collection, https://digitalcollections.lib.uct.ac.za/islandora/object/islandora%3A18142.

54 J. Ferguson, Global Shadows: Africa in the Neoliberal Order (Durham: Duke University Press, 2006), 176-93. [ Links ]

55 In G. Minkley, '"A Fragile Inheritor": The Post-Apartheid Memorial Complex, A.C. Jordan and the Re-imagining of Cultural Heritage in the Eastern Cape', Kronos, 34, 2008, 32.

56 Ibid.

57 W. Anderson, 'Introduction: Postcolonial Technoscience', Social Studies of Science 32, 5/6, 2002, 643-58. The proliferation of alternative modernities, while recognised as a laudable set of anticolonial/postcolonial struggles, are seemingly still constrained by the originary concept of modernity and thus, according to Dirlik, 'remain entrapped within the hegemonic assumptions of an earlier modernity'. See A. Dirlik, 'Thinking Modernity Historically: Is "Alternative Modernity" the Answer?' Asian Review of World Histories, 1, 1, 2013, 7.

58 Hevia, 'The Photography Complex', 86.

59 See N.R. Hunt, A Colonial Lexicon: Of Birth Ritual, Medicalization and Mobility in the Congo (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 1999).

60 M. Gullestad, Picturing Pity: Pitfalls and Pleasures in Cross-Cultural Communication. Image and Word in a North Cameroon Mission (New York and Oxford: Berghahn, 2007).

61 Ibid., 3.

62 The liberal subject is understood here as Foucault's founding subject of history - the individual, rational citizen-subject, cohered around the nation state. See E. Deeds Ermath, 'Beyond "The Subject": Individuality in the Discursive Condition', New Literary History, 31, 2000, 413.

63 J. Comaroff and J. Comaroff, 'Introduction, in J. Comaroff and J. Comaroff (eds), Modernity and its Malcontents: Ritual and Power in Postcolonial Africa (Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 1993), xvi.

64 Interview with Ronald Ingle, November 2012.

65 L. Wexler, 'The State of the Album', Photography and Culture, 10, 2, 2017, 100.

66 F. Cooper, Citizenship between Empire and Nation (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2014), ix.

67 As Cooper suggests, citizenship hinges on the relationships between individuals and states, and involves various and shifting forms of inclusion and therefore also exclusion.

68 R. Vigne, Liberals against Apartheid: A History of the Liberal Party in South Africa, 1953-68 (London: Macmillan, 1997), 165.

69 Ibid.; see especially the chapter titled 'Transkei Victory'.

70 E.F. Isin and G.M. Nielsen, 'Introduction: Acts of Citizenship, in E.F. Isin and G.M. Nielsen (eds), Acts of Citizenship (Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 2008).

71 Ibid., 4.

72 E.F. Isin, 'Two Regimes of Rights', paper presented at European Consortium for Political Research Workshop on Practices of Citizenship and the Politics of (In)security, Lisbon, 14-19 April 2009. [ Links ]

73 K. Howard, 'The "Right to Have Rights" 65 Years Later: Justice beyond Humanitarianism, Politics beyond Sovereignty, Global Justice: Theory, Practice, Rhetoric, 10, 1, 2017, 93. [ Links ]

74 C. Youé, 'Citizen and Subject: Contemporary Africa and the Legacy of Late Colonialism by Mahmood Mamdani: A Review', Canadian Journal of African Studies, 34, 2, 2000, 397-408. [ Links ]