Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Kronos

On-line version ISSN 2309-9585

Print version ISSN 0259-0190

Kronos vol.46 n.1 Cape Town Nov. 2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2309-9585/2020/v46a8

PART 2 REWORKINGS

Atlas of an Empire: Photographic Narrations and the Visual Struggle for Mozambique

Rui Assubuji

Centre for Humanities Research, University of the Western Cape; https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7279-5998

ABSTRACT

This article engages with the historiography of the Portuguese empire with reference to Mozambique. It explores the impact of visual archives on existing debates and asks what difference photographs make to our interpretation and understanding of this colonial past. Deprived of their 'historical rights' by the requirements of the Berlin treaties that insisted on 'effective occupation', the Portuguese started to employ a complex of knowledge-producing activities in which photography was crucially involved. This article examines different photographic moments before and during the 'Pacification Campaign' that assured Portugal's authority over the Gaza Empire in southern Mozambique in the 1890s, by official, commercial and missionary photographers. It identifies controversies over the small number of portraits of the Gaza king Ngungunyane that took on distinctive and disputed 'other lives' after their initial production. The realisation of how one image might be disassembled to generate others becomes an exercise - in visual terms - of rethinking colonial violence. A critical engagement with the slippages and repositionings around photographs, and the errors or disputes in various captions, allows for a better understanding of the production of both silence and particular narratives in the archives and popular history. The demonstration of these other lives matters because it stimulates awareness of what is seen, what is made visible, and addresses the desire to look beyond the image to find others in a continuous interrogation of photographic excess.

Introduction: Portraits and Silences in the Archive

Atlas often begins...in an arbitrary or problematic way ..quite unlike the beginning of a story or the promise of an argument; and as for the end, it often reveals the emergence of a new country, a new zone of knowledge to be explored.1

This study analyses photographs from different archives against a backdrop of related information that is mostly focused on the 'effective occupation' of Mozambique by the Portuguese in the late nineteenth century.2 To a great extent, the massive production of documentation on such African territories was for economic and military control. As a 'tool of empire', it was thought photography would help to map the world.3 As Shohat warns, however, if writing cultures are embedded in the ideology of power, visualising cultures documented not only the other but also assumed the ability of science to 'decipher the other'.4 Following such leads, this article uses photographs to question the history they purport to depict. Given the often unexpected findings of the existence of different moments within a single image,5 this makes photographs potential generators of a 'new genre of knowledge'.6

The notion of Atlas is used here not only as a concept to understand assemblages but as a research method, a form of image 'dissection'.7 In the process, some things stick and persist, others do not, and the image travels in a new narrative. What does it matter? It corresponds with Belting's arguments that while many images are consumed and forgotten, others endowed with meaning enter into memory, a potential site for the other lives of an image.8 Perhaps that is what matters.

This article examines different photographic moments in depictions of the 'Pacification Campaigns' that assured Portugal's authority over the south of Mozambique in the 1890s.9 Its major challenge was the Gaza Empire and its emperor, Ngungunyane. According to Aires de Órnelas,10 one of the breakaway Nguni lineages from the Zulu empire crossed the Incomati River and, subjugating peoples along the way, settled in Bilene. That was the origin of the Gaza Empire led by Manicussi, also called Sochangana. His grandson Ngungunyane came to power in 1884 and was the last emperor. He established his residence in Mussorize with influence stretching beyond the Zambezi River. In 1889 he moved to Mandlakazi (spelt Manjacaze by the Portuguese) and strengthened the empire between the Limpopo and Save rivers.

According to Gerhard Liesegang, Portugal only became a real colonial power after its conquest of Gaza, which allowed the first formal unification of Mozambique as one territory.11 Governmental, commercial and missionary institutions all narrated the end of this great African power in their distinctive ways. In the Portuguese African capital city of Lourenço Marques, for example, the photographer Louis Hily depicted the embellished Arc of Triumph celebrating the arrival of the 'Lion of Gaza', the feared and now captive chief Ngungunyane.12 By contrast, shortly before this in the Gaza capital of Mandlakazi, the Swiss missionary George Liengme had photographed people and events that were significant to the autonomous African empire.13Whether or not created for a specific photographic purpose, this article explores how the circulation of photographs of events, and the cutting, pasting and reuse of the image result in a continuous revelation that renders old pictures new.14

Elizabeth Edwards argues that photography is not a simple representation, but sets of material practices entangled with conducts of governance through complex and sometimes ambiguous demands to produce information that inflects government practices. Therefore, despite the promise of mechanical objectivity, the truth-claims of photographic evidence are not straightforward but negotiated and historically and spatially specific.15 As a contribution to this ongoing discussion, this article identifies controversies over the small number of actual portraits of the Gaza emperor that took on distinctive and disputed 'other lives' after their initial production.

One such controversy concerns the photograph said to be of Ngungunyane in front of a hut, taken at the moment of his arrest, near the burial site of his ancestors, a place called Chaimite. Different sources attribute the photograph to two completely different authors with different provenances. Another photograph of Ngungunyane seated on a chair surrounded by some of his companions going into exile (a row enclosed by armed European policemen) is said to have been taken at the prison in Lourenço Marques. A very similar photograph in a different archive, however, specifies the location as the fort of Monsanto, a prison located in Lisbon. According to Leonor P. Martins, a portrait of Ngungunyane in the ship on the way to exile was the first actual photograph published in the press, by the newspaper O Occidente in 1896.16 The dispute over photographic authorship, dates, location and subject identities associated with considerable photographic diffusion, denotes, in a sense, a visual struggle for Mozambique.17

As an amateur photographer, the Swiss missionary George Liengme is a remarkable contributor to this 'visual struggle'. Searching through his archives, it becomes possible to understand his commitment to photographic production. Residing near the king in Mandlakazi, he photographed people and important events, producing a more intimate portrait of African society at the end of the 'last Mozambique traditional empire'.18 Ngungunyane's pose seems to be more spontaneous in front of Dr Liengme's photographic camera, in comparison with other photographs (see Figure 16).

It is one of the very few photographs of Ngungunyane in the missionary's archive. One of the reasons for this paucity might be that part of his photographic production and other family belongings were left behind in their rushed departure from Mandlakazi, a few days before it was assaulted by the Portuguese forces. These items were possibly destroyed by the fire that burned down the entire African capital. Portuguese accounts report that explosions from Liengme's house during the fire proved his involvement in local politics, promoting and materially supporting the non-submission of the African potentate. Officially expelled from Portuguese territories, Liengme and his family went to the neighbouring Boer Republic of the Transvaal, where many other fleeing Africans also settled.

While the scattered nature of the photographic archives relating to the Gaza Empire is one problem when searching for images, their scarcity is another. The latter goes against the desire for pictures of the king and the annihilation of his kingdom. There is a sketch (not a photograph) depicting Mandlakazi burning as Portuguese soldiers follow the order to charge given by a mounted commandant located prominently in the foreground of the image, against a backdrop of flames.19 The caption reads, 'Occupation of Manjacase [Portuguese spelling], last military operation before Chaimite.' There are also some drawings of battles in which Portuguese soldiers hold a square formation surrounded by the charge of enemy warriors, and bodies on the ground show the unequal losses. While the disagreements over and reproductions of the few portraits of Ngungunyane proliferate, it is notable that no direct reflection of violence emerges in the photographic archives of the Portuguese territorial occupation, the 'Campaigns of Pacification'.20

In the process of examining this historical episode in Mozambique, the realisation of how one image might be disassembled to generate others becomes an exercise - in visual terms - of rethinking colonial violence.21 A critical engagement with the slippages and repositionings around photographs, and the errors or disputes in various captions, allows for a better understanding of the production of both silence and certain narratives in the archives and popular history. The demonstration of these other lives matters because it stimulates awareness of what is seen, what is made visible, and addresses the desire to look beyond the image to find others, a continuous interrogation of the chaos of excess.22

Toppling the Gaza Empire

The traffic into the African capital Mandlakazi was intense before 1894, visited by journalists, government officials and businessmen seeking to meet the king or to establish commercial relations within his empire. All with their own interests in the region, the different colonial powers considered Ngungunyane a very important ally. Liengme's diary reveals that he became a greatly desired yet elusive photographic subject. Despite Ngungunyane's prominence, there is a gulf between the desire for his image and the apparent lack of photographs of him. This article analyses some of the photographs taken by members of the Geographic and Geodesic missions in southern Mozambique, by Hily, and by Liengme.

The campaign against the Gaza Empire in 1894-5 is considered the beginning of the policy of 'effective occupation' undertaken by Portugal in its colonial territories after the Berlin Conference of 1884-5. In southern Mozambique, Ngungunyane's empire was the most significant challenge to the Portuguese authority. Due to colonial competition with Great Britain, there was already a degree of instability around the growing settlement at the city port of Lourenço Marques, surrounded by untrustworthy local chiefdoms of Capela, Maputo, Matola and Inhaka, themselves also increasingly pressured by the Nguni-ised Gaza warriors.23

While the British had competing designs on the port city, Gaza represented the major impediment to absolute colonial ownership of the region. According to Quintinha and Toscano, the Portuguese were in East Africa longer than the establishment of Gaza (also referred to as the Vátua-Nguni), therefore to annihilate the African power was an unquestionable political necessity for their control over the territory.24 In their turn, the 'Vátua gave the name of Camfuma to the city of Lourenço Marques'.25 The control of the bay's commercial routes was strategic for Gaza to access firearms, forbidden to them through the British port of Natal and the Transvaal Boer Republic.26

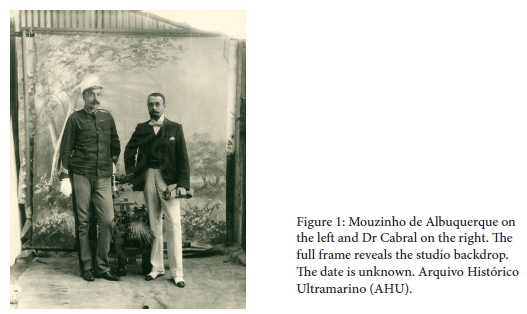

The end of the Gaza campaign in 1894-5 expanded Portuguese authority in the region between the Maputo and Save rivers, bringing to Lourenço Marques a period of prosperity. However, different information attached to several photographs of the campaign present narrative disputes and lead us in multiple historical directions. Let us start with the work of Louis Hily, a professional photographer, founder of a photographic company considered to be a 'remarkable presence in town'.27 Invited by the Portuguese authorities, he arrived in 1889 and, by 1894, was running his commercial studio in the busiest part of the city. A friendly relationship with the Royal Commissioner Mouzinho de Albuquerque certainly facilitated his official photographic work.28 The photograph of Albuquerque together with Dr Baltazar Cabral (Figure 1) is probably from his studio.29

Probably the only professional in town, Hily was apparently the official photographer during the campaign against the Gaza Empire in 1895. The photograph in Figure 2 shows that despite being a prisoner, Ngungunyane seems to benefit from special treatment because he is not seated on the floor and still holds his symbolic props.30 His seven wives (Namatuco, Fussi, Patihina, Muzamussi, Maxaxa, Xesipe and Dabondi) are kneeling; queens did not directly sit on the floor, according to custom. They are similarly dressed, with pieces of cloth draped over their shoulders and bangles on their arms. The other figures in the photograph are the uncle of Ngungunyane, Molungo, standing behind him, and on the right, Ngungunyane's son, Godide. All the Africans in the picture went into exile in Portugal. There, because polygamous relations were not allowed, the authorities deported the women to St. Tomé while the men were sent to the Azores.31

Enclosing the rows of prisoners in Figure 2, two armed police guards provide a visual reassurance that Ngungunyane has been arrested. The image bears the stamp of Foto Hily Lda on the bottom right side of the frame, indicating the photographer.33The photograph is archived under the theme 'Several aspects related to Mouzinho de Albuquerque, in Lourenço Marques'. In his book Mouzinho de Albuquerque, Paulo Fernandes published the same image with the caption 'Na prisão em Lourenço Marques, acompanhado pelas mulheres capturadas pelas forças portuguesas' (in the prison of Lourenço Marques, accompanied by his wives, captured by Portuguese forces).34

A photographic collector published a similar image without Hily's signature stamp (Figure 3) on her blog and attached the information: 'Forte of Monsanto, Lisbon 1896. Standing: Zixaxa and Godide (son of Gungunhana). Gungunhana is seated, and his seven wives before they embarked to the Azores.'35 The same photograph features in the catalogue of the exhibition Gungunhana em exílio.36The caption states that it was taken at a prison in Lisbon. At first glance, it seems that Figures 2 and 3 are the same, but visual evidence indicates that at least two photographs were taken on the occasion. Compared with the image in Figure 2, the point of view in Figure 3 moved slightly to the left. Either the camera changed position, or two cameras placed side by side were used.

In this reading, the existence of two similar photographs of the same occasion underlines the significance ascribed to the subject. But there are fundamental contradictions in relation to the location where the photograph was taken: was it Lourenço Marques or Lisbon? If the latter, it means that Hily accompanied the delegation to Europe. This research has no evidence, however, of Hily's photographic activity in Europe. It is likely that the photographs in Figures 2 and 3 were taken in Lourenço Marques: given the bars in the window on the wall behind, there is very little doubt that the photographs were taken outside the prison. The zinc sheet leaning against the wall towards the back recalls the fire that almost destroyed the town in 1875, and the changes in construction afterwards.37

The city of Lourenço Marques had an Arc of Triumph built to receive Mouzinho de Albuquerque and the captured African aristocracy in December 1895. For a short period, the prisoners were exhibited to the local public, then moved to the city prison to wait for extradition to Portugal.38 On 13 March 1896, the ship transporting them from Africa arrived in the festive European capital Lisbon, receiving high government attention and exceptional press coverage. From the harbour, crowds accompanied the exiled Africans to the zoo, the site of their public exhibition. Days later, the prisoners were jailed in the city prison, Forte de Monsanto. These eventful days agitated the city's quotidian life.39 Curiosity and sympathy disrupted the routines of the penitentiary establishment and its surroundings, which played some part in determining the transfer of prisoners to the Azores islands.40

The discrepancy in photographic ascription between Lourenço Marques and Lisbon shows slippages and repositionings, pointing to the way images can take on other lives that have less to do with the actuality of the photographic occasion. As a prisoner in both places, does Ngungunyane remain kingly? What does it matter that he and his entourage 'appear' in Lisbon through the wrong caption (Figure 3)? The people in the picture are once more displaced. Some even lost their original identity to assume others, such as 'Zixaxa' instead of 'Mulungo'. Is that evidence of the violence of the colonial process? Another photograph taken on the day of their religious baptism with new European attire and Portuguese names might be one of the best illustrations of this.

According to various sources, the defeat of Ngungunyane was well received among many of his peoples. Internationally, with the end of Gaza, Portugal affirmed its position as a colonial empire. For the nation itself, the demise of the African enemy promoted national pride and created the greatest Portuguese hero, Mouzinho de Albuquerque.41

Multiple Constructions of Ngungunyane

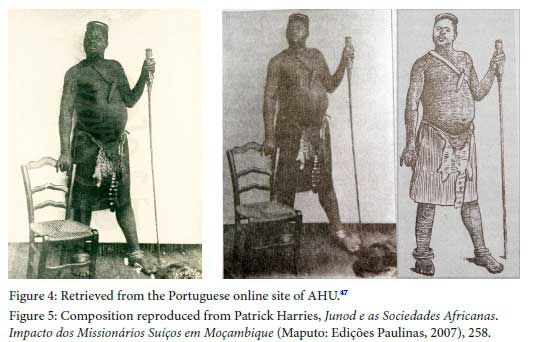

Figure 4 shows another image that has been replicated and appropriated. Different sources credit the same photograph to different photographers and subjects. The photograph features in the monograph Mouzinho de Albuquerque.42The publication acknowledges the Arquivo Histórico Ultramarino. The caption reads, 'King at the moment of his arrest in Chaimite', which is the burial site of his father, the former king Muzila.43 The photograph also features without credits or captions in a Portuguese novel.44 In both publications, the pages of illustrations are unnumbered.

In the IICT/AHU digital collections, the photograph is credited to Foto Hily Lda. The caption of the same photograph reads 'Gungunhana photographed at the hut of his arrest'. In other publications, the same photograph indicates that it is outside the house where Ngungunyane was 'hiding at the moment of his arrest'.45 In the picture, the artificial backcloth does not cover the entire frame and the lower part of a wall behind, made of bamboo canes, shows at the bottom of the image. The failure to fully remove the clustered bits of environment result in the photograph having a peculiar excess.46

According to Portuguese historiography, Mouzinho de Albuquerque charged into the fenced kraal where Ngungunyane was sheltering and, in front of his hut, ordered the Régulo Gungunhana (as the Portuguese referred to him) to come out and sit on the floor, to enforce his new condition of a matonga.48Assuming the man depicted is Ngungunyane, was the photographer present at the site when the arrest happened, or did he arrive after the action to produce the photographic session? Was he carrying the photographic backdrop all along? Was this portrait of the king thought out in advance of his arrest? This research found nothing to acknowledge the presence of the photographer during the military manoeuvres, nor are there any accounts of the taking of this photograph, which would certainly require some preparation.

Controversially, the same photograph is published in a composite of two images, and commented upon by the historian Patrick Harries. The depicted, he says, is Ntchoungi, a sub-chief of the Khosa ethnic group from near Antioka, their home-land.49 He explains that the man has an ebony snuffbox hanging on his chest, holds a staff with a sculptured head, and wears a wildcat skin around the waist, which means that he was considered a Khela - an adult man allowed to wear a circlet on his head (called ngiyana in Ronga).50 There is a European-style manufactured chair in the picture. This prop was adopted in many African milieus, reserved for the privileged, but this featured stance is possibly significant.51

Harries analysed the work of the Swiss missionary Henri Junod, whose ethnographic method did much to construct the image of a pure and authentic Thonga community. He presents a composition of two images demonstrating that based on the photograph on the left, the image on the right (for Junod's book) was made by an illustrator who carefully omits the chair in the original picture.52 For Harries, Junod knew the local importance of the chair, yet excluded it from the image he used because it conflicted with his idea of what 'constituted an authentic Khosa African chief'.53 This strongly resonates with arguments that 'the Tsonga' was an invention directly connected with the establishment of the Romande Mission identity within the European Christian milieu.54

Philosophically, in a Portuguese colonial context, the image could express the loss of Ngungunyane's kingdom. His power has been reduced to a few cultural symbols, such as the wax circlet on his head, the stick in his hand, and the meaningful foreign chair on which he is not allowed to sit. In the missionary or academic context, the intention of the image might be purely scientific or documentary, a representation of 'the other' before contamination. Yet, while a simple photographic procedure, the neutral background represents a kind of deterritorialisation: once removed from their natural environment, subjects can be inserted into varied contexts, even, as this discussion demonstrates, to validate scientific conclusions.

Other Generative Photographs

There are at least two photographs of a meeting between Mr Almeida (a Portuguese representative) and Ngungunyane in 1890. They belong to the collection of the Geographical and Geodesic expeditions for the delimitation of the borders of Lourenço Marques of 1890-1, Album Fotográfico n3 Comissão de Delimitação de Fronteira de Lourenço Marques 1890-91'.55 Three names acknowledge the authors of the photographs: Alfredo Freire de Andrade, Etelvino Mezzena, and José Antonio Mateus Serrano.56

The Portuguese used diplomacy to negotiate with different African powers. Officials were appointed as counsellors and individuals such as José Casaleiro Rodrigues, Marques Geraldes, Paiva Raposo and Vieira Braga are referred to as having produced interesting information about the Gaza Empire in particular.57 The Royal-Commissioner Antonio Ennes used 'resident ambassadors' who lived close to the king Gungunhana (their spelling) as a bridge to communication between the two empires.58 The first was Joaquim Júdice Breyner, initially an employee of the Companhia de Moçambique. Based near the mouth of the Limpopo River, he picked up on the discontent of various African chiefs with their king. Since the Portuguese needed to keep smooth relations with the latter, Breyner was instructed not to react to the complaints.

Breyner was replaced by Mr José Joaquim de Almeida, the 'most salient' among the resident counsellors to produce consistent information about the Gaza Empire.60He was not trusted by the Royal Commissioner, Ennes, because of his easy access to the Gaza king. He was assigned the mission to deliver an ultimatum to Ngungunyane demanding the handover of two rebel chiefs, Nwamantibyane Mfumu and Mahazule Mbayaya. The latter had disturbed the region near Lourenço Marques and escaped from the Portuguese territory to Gaza after the Marracuene combat in August 1894.61Protected by the African king, they later departed with him into exile and, perhaps for that reason, their identities appear mistaken in the caption of one photograph discussed earlier.62 Almeida met Ngungunyane several times, and there are two similar photographs from one occasion.

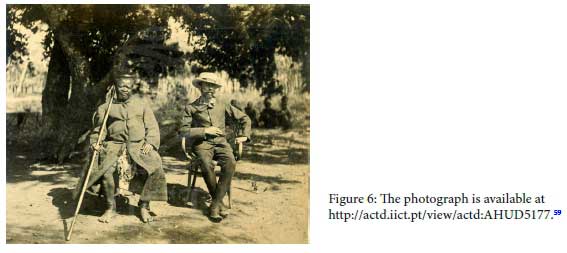

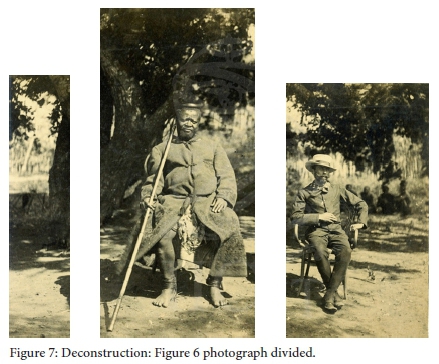

This section uses the photograph in Figure 6 for another demonstration of how to disassemble one image (Figure 7) to generate others which are applied to different contexts, eventually with different captions. In some cases, the new ones are no longer related to the original photograph, or the relation is very tenuous. The picture of Ngungunyane and Almeida sitting together on chairs facing the camera features in the monograph Moçambique by Villarinho Pereira, and the caption reads: 'Gungunhana and José Joaquim d'Almeida (Manjacase, 11.08.1890). Photo. Elvino Mezzena - IICT/AHU doc141/4022.'63

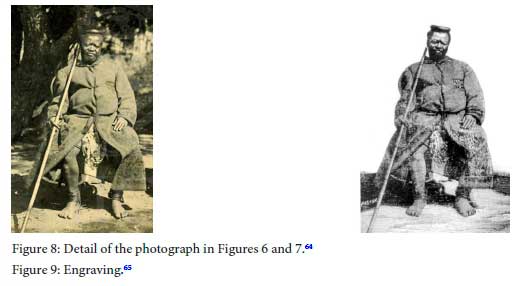

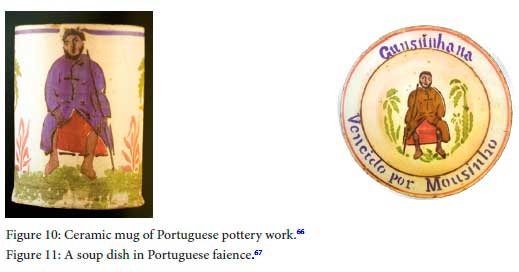

In a deconstruction process, Figure 7 reproduces the photograph in Figure 6, then divides the image into three panels, and the middle is enlarged to make an image of the king. The middle panel of Figure 7 is isolated in Figure 8 and compared with a further reproduction (the engraving in Figure 9). The relationship between the two images is evident, as it is with Figures 10, 11 and similar pictures or artifacts.

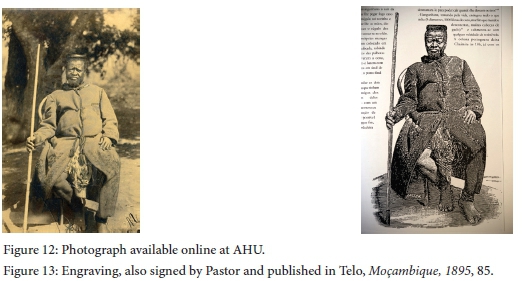

The second photograph we examine here is also available from the ACT digital archive, and features Ngungunyane seated alone, as presented in Figure 12. The similarities with his image in Figure 8 suggest that the two pictures are from the same occasion of Almeida's visit. The different positions of the stick and the king's leg indicate that at least two photographs resulted from that particular 'photographic event'.68 It is difficult to assert whether Figure 12 is a detail of a similar frame that included Mr Almeida, or if Ngungunyane was alone in the picture. What is interesting is the inscription at the bottom left of the image. Is this visible 'M' the signature of Mezzena, who is credited with this image in the monograph by Villarinho Pereira? The 'M' does not appear in the photograph in Figure 9.

Yet, in this archive, the photograph (Figure 12) has a very strange caption: 'Gungunhana, head of the porters.' My research did not find any explanation for such information. The authors credited are Alfredo Freire de Andrade, Etelvino Mezena, and José Antônio Mateus Serrano. The source is an albumen print; 13x18 cm. This image of the king sitting alone inspired several reproductions that used different mediums to apply it in varied circumstances (see Figures 13-15).

Backstage in Gaza: The Photos of Liengme

Official Portuguese depictions of the king are not the only existing photographs of Ngungunyane. The Swiss missionary George Liengme kept a diary and also took photographs during the time he lived in Moçambique and the Transvaal.70 From 1892, Liengme made several visits to Gaza before he settled in the capital Mandlakazi.

The first Portuguese representative, Mr Júdice Breyner, introduced Liengme to Ngungunyane, who authorised the missionary to establish a station. In 1893 he moved in with his wife, the nurse Berthe-Julie Ryff, and their daughter Berthlette. As Liengme's medical and missionary work evolved, a relationship developed between him and the king, who also benefited from medical assistance.

Many of Liengme's photographs feature in different publications and exhibitions.71 A folder made available to this researcher by a family member contains 17 printed black and white photographs he took, mostly in Mandlakazi.72 The negatives of these photographs can be found among his other lesser-known photographs in the Liengme Papers at the Penthes archive. These photo collections, the diary and other related material animate the discussion here. Through visual and textual narratives, Liengme takes the readers to the heart of the Gaza Empire where he lived and documented its last days between 1893 and 1895. The photographs are analysed individually or in groups here, cross-referenced with narratives in his diary, a useful backdrop to help speculate on the depicted individuals, events and the photographer himself.

Figure 16 presents a more naturalistic portrait of Ngungunyane.73 Taken against a very bright background, he seems to be standing in the middle of a path under the shade of a tree, holding a stick in one hand. He looks straight into the camera, with a relaxed, even amused expression, and the background suggests a semi-arid space dotted with scattered trees and a few people. Behind him on the left, two individuals are standing, one partly cut off by the frame of the image; the other stands holding a stick in a pose similar to the king's. Far back, other silhouettes are an allusion to the distance between the king and the common people.

There is also a line that seems to be a palisade, probably demarcating an area in the royal residential area. The glare of the excessive light from the back gives an impression almost of divinity. The subject is not extracted from his environment; he seems to be comfortable with the presence of the camera and has a natural pose. An attitude of consent emanates from his posture as well as a sense of spontaneity. The evident unpreparedness suggests a kind of photographic opportunity whereby Liengme was lucky enough to take a more intimate portrait of Ngungunyane. Even if not intentional, the slightly lower angle of the camera results in a respectful gesture.

The missionary depicts aspects and events that occurred in the last few years of the Gaza Empire. In his collection, photographs such as the one in which his wife Berthe plays the organ surrounded by local people illustrate missionary activities. Along with the musical instrument, pictures of saints and biblical scenes were a great attraction, and according to him, 'kept the locals in the religious services'. His impressions are also vividly described in his written diary.74 In the Penthes archive there are handwritten indications on the envelope that contains the photographic prints, such as 'Group of black Christians at missionary service', 'A black evangelist', 'Christian women', 'Group of blacks Occidentalised'.

There are some photographs of Liengme's medical yard and surgical interventions, such as a tooth extraction performed in an open space to the admiration of a curious audience. There are also images of his family and his travels. His most well-known photographs are the ones that depict members of the royal family, some indu-nas, different warriors and other aspects of the life within the kingdom.76 A great number of the photographs in his collection depict the royal women, either posing or in more spontaneous situations.77

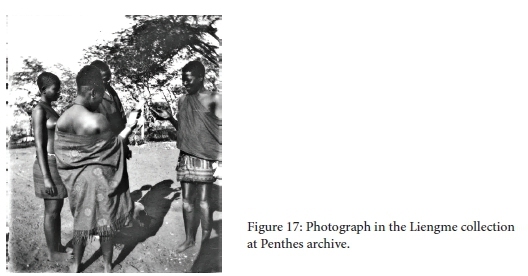

In the photograph in Figure 17, two girls and one man are holding shiny objects in their hands while another girl looks on. With her back turned against the photographer, the girl in the foreground has shoulders uncovered despite the stylish scarf hanging off her arms. Her slightly turned position reveals the bangles she wears, a sign of aristocracy. She partially covers a young man who also has a similar object in his hand. It seems that he is showing it to another girl on the side, all amused and intrigued by it. A pet dog in the image is sniffing around their feet. The outdoor photograph displays a space encircled by sparsely distributed trees. The image speaks to the following entry in the Liengme diary:

During the afternoon several of Gungunhana young girls 'Batombzane' came to visit us. That means his servants, his slaves, his concubines. They were very many. Some most probably have a better position than the slaves.78

In fact, only one of the figures in the photograph wears bangles as well as earrings. Her hair is arranged in a royal style. The other two girls could be helpmates and the man possibly Liengme's assistant. Apparently, they wanted to see the images of Jesus that were used to evangelise, to listen to hymns played with the organ, and to 'beg for little presents'. Liengme wrote:

They also wanted to see the photographs I took, and one depicting a young girl whom they know well caused exclamations, cries of surprise...I had to lend the photograph, they wanted to show it to Gungunhana.79

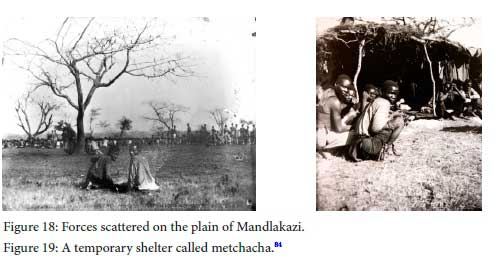

Yet, living near the king also allowed Liengme to witness particular events that marked the decline of that African state.80 The assembly of Ngungunyane's army in Mandlakazi was one such moment he attempted to portray. These are among the most published photographs taken by Liengme in Mandlakazi. He wrote:

Mandlakazi, October 1894 - the king's army is gathering. Every day troops of 50 to 100 individuals arrive in war costume. When the whole force is reunited, then the great ceremony will come...will distribute the 'war medicine' eaten to fortify their bodies, their courage enhanced to special fury that will push them to valiant combat.81

Many of these photographs have neither good definition nor well-composed frames, but they give an impression of the space and the people. This consideration recalls Feldman's arguments around saturation and blur: adapting the concept of 'saturated image', this research argues that resisting full visibility allows identification with a historical event not limited to an instant.82Figure 18 depicts the warriors in scattered camps on a surrounding plain he called Mangwaniane. Liengme wrote about visits to those camps: 'The temporary huts called metchacha, are simple shelters built with branches and grass.'83

On the plains of Mandlakazi, the presence of numerous men became problematic. There was famine and poor health conditions, and the difficulties mounted. The number of sick people increased daily at the missionary station. Many were warriors coming from the temporary shelters. Each day, early in the morning, groups gathered in front of the station 'hospital', and after a short religious service, Liengme would start with consultations.

I treat people with back pain and rheumatism in groups. ... I give them a small pot of turpentine mixed with alcohol infused with camphor. . This medicine stinks, burns and smells. These are the three qualities indigenous people appreciate when it comes to medicine. . A medicine that is easy to take or swallow or has no nasty taste is not a medicine. I make sure the medicine complies with their ideas and this actually makes my task easier.85

Such descriptions made apparent the nonexistence of organised logistics to maintain the soldiers until the time of combat. The army massed men from different backgrounds, an aspect visually remarked by Liengme.86 It is also relevant because it displays alliances and disassociations, exposing divisions within the kingdom. Ngungunyane complained about the absence of family members and accused them of treason.87 Wheeler argues that from the 1890s, the Gaza Empire was in a state of decay, manifested through old tensions mostly based on ethnic and regional identification that had been suppressed but obviously not erased.88 According to Wheeler, this was 'altogether the history of the empire from its foundation'.89

The Benguyo ceremony. Mandlakazi in October 1894

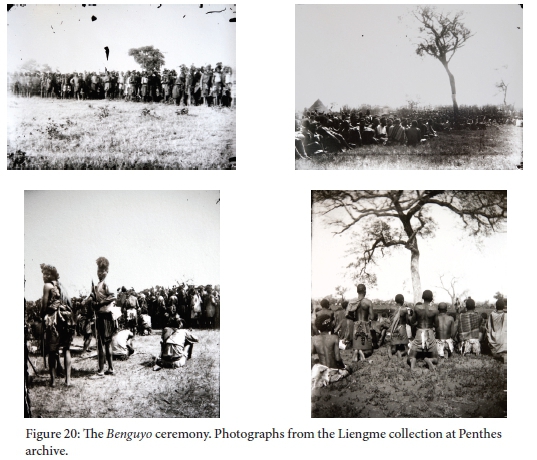

In the following set of images organised as a contact sheet (Figure 20), some photographs give a visual impression of the ceremony called Benguyo in which war medicine is distributed by the king and taken by the warriors.90 In his diary, Liengme wrote:

This morning the whole army that is camping in the vicinity was ordered to come to Mandlakazi. This resembles a revue passing in front of the king. Gungunhana was sitting on his ordinary chair surrounded by some of his main chiefs. I went to greet them, chatted for a moment with him and asked permission to take some photos. He received me warmly and gave me the permission to go ahead...91

The king arrived at the site of the ceremony, and the men encircled one of the army chiefs covered with plumage, carrying a shield and assegai in the left hand and a stick of ebony in the right. He made a vow before the king. The whole army made the same vow: 'Your army, here it is. It has arrived. We are ready to leave. Give the names of those who must be killed...' Meanwhile, wrote Liengme, warriors came out of their ranks, about 15,000 men dancing or rather performing prodigious leaps. Many had still not yet arrived. The king promised them something after the dances. The missionary considered what was happening to be 'indescribable'. In the entry of Monday 5 November, he confesses:

I really want to attend the ceremony. It was a unique occasion. The immense Mandlakazi plain, called Shibandla, was encircled by warriors, some were sitting; some were standing. The warriors were in their ranks, so close to one another that it was difficult to move through this tightly packed crowd. There were at least 50 000 men. If all warrior subjects responded on his call there would probably be at least 500 000 men. The natural healers and the young men formed a guard of honour in the center, which is a place reserved for them.92

The Benguyo ceremony happened from October to November in 1894. Ngungunyane distributed the famous war medicine to the warriors gathered at the Mandlakazi plain. Then the force was dispersed and departed to raid, but the hunting group stayed. The king joined the latter group and led the hunt. In an entry in his diary from 9 November, Liengme reported that the king returned the same day with antelope, baboons, badgers, rabbits, and other animals. 'Nothing escapes,' observed Liengme, 'in such clubbing expeditions, they kill everything. The indigenous people highly value the skins of Apes.'93 In general, the skin of small game indicated high rank, worn in both ceremonies and battle.

Hedges suggests a close correlation between warfare and hunting and explains the collaborative tactics employed in encounters with dangerous game.94 According to Junod, it was a collective activity since most African hunters only possessed simple and inadequate weapons that made it impossible for a single man to hunt big animals.95 These kinds of activities were part of the initial steps in a warrior's formation. The young unmarried men placed at the formation fringes were the first to enter into contact with the seized animal. Mature men occupied a more protected section in the centre of a semi-circle formation. According to Hedges, they used a throwing lance, possibly poisoned, for moving animals, and a shorter assegai for the close-quarter stabbing of animals, or men, and used axes as well.96 Hunting was part of a mixed economy for most of the southern Mozambique peoples, 'disproportionally emphasized' in periods of political and economic displacement.

For the Gaza Empire, this was a period of growing tension and danger. Portuguese forces were surrounding them and war became inevitable. Liengme arrived before the war and left days before the burning of Mandlakazi. His archive contains many formal and informal photographs of the royal family, queens, princes and princesses, the queen's village, other members of the aristocracy, indunas, wizards, as well as a slave woman with a child.97 It seems the queens may have bombarded Ngungunyane with enthusiasm and shared photographs. The king accepts the camera naturally and allows Liengme to use it. His photographs, however, are mostly characterised by opportunity and blurriness. That informality, in a sense, inserts him into the mundane of the local. In general, the act of photographing seems to be more a playful moment, which is in contrast to Hily's compositional care that creates a sense of distance by detaching the subjects from their daily life into the photographic event.

Ngungunyane probably did not realise that photography had already arrested him in Mandlakazi in 1894, in the portrait with the Portuguese counsellor where both are turned straight towards the camera, and not in conversation with each other. Seated next to each other, under the sun, Ngungunyane wears the mantle offered by the king of Portugal (see Figure 6). An acknowledged astute negotiator, this was probably a diplomatic gesture. But it did not prevent his final arrest in Chaimite, an event registered in a controversial photograph. Photographs and other images of arrested and exiled Africans are not scarce in colonial depictions, and while they may not reference it directly, they express something of the violence of the process.98

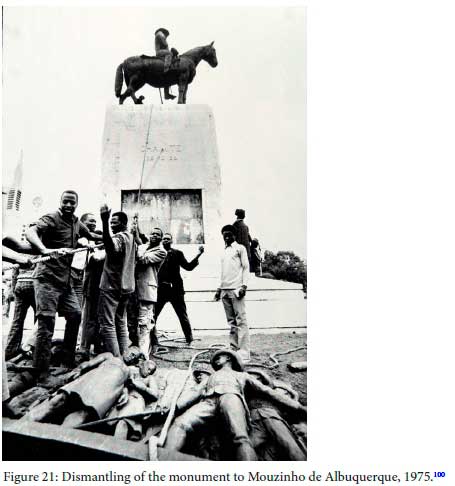

A well-known photograph of Mouzinho de Albuquerque provided the model for an equestrian statue that became part of the monument dedicated to this great Portuguese hero, erected in the principal square of the city of Lourenço Marques that was named after him. Its pompous inauguration in December 1940 marked the rise of the fascist regime in Portugal. In an interesting photographic ellipsis, the photojournalist Ricardo Rangel recorded the dismantling of this monument in 1975 (Figure 21).99 At the very same location, now called Independence Square, a monumental statue of Samora Machel was erected in 2013 to replace Mouzinho de Albuquerque with a Mozambican hero.

Not far from this location, a public exhibition at the Fortaleza de Maputo recalls the historical colonial episode of the conquest of Gaza that can be revisited and interrogated. This article likewise deconstructs, reconstructs, compares and recontextualises photographs in an attempt to understand how images are created and utilised across history. It requires an approach that allows for different perspectives, disputes and appropriations to reflect 'other lives of the image' that enrich ongoing narratives. These and many other pictures are, to a certain extent, battlefields in a visual struggle for Mozambique.

1 G. Didi-Huberman, Atlas, or the Anxious Gay Science (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2018), 3. [ Links ]

2 The author wishes to acknowledge the DST/NRF SARChI Chair in Visual History and Theory (Unique Grant 98911) and the CHR at UWC, as well as the Gulbenkian Foundation in Portugal, for their support towards the archival doctoral research on which this article is based. The author also thanks the Arquivo Histórico Ultramarino, the Arquivo Científico Tropical (Digital Repository) and the Musée des Suisses dans le Monde in Penthes for permission to reproduce photographs.

3 D.R. Headrick, The Tools of Empire: Technology and European Imperialism in the Nineteenth Century (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1981). [ Links ]

4 E. Shohat, 'Imaging Terra Incognita: The Disciplinary Gaze of Empire', Public Culture 3, 2, Spring 1991, 42, doi:10.1215/08992363-3-2-41. [ Links ]

5 On this matter see a concept of visual dissonances in R. Assubuji, 'A Visual Struggle for Mozambique: Revisiting Narratives, Interpreting Photographs (1850-1930)' (unpublished PhD dissertation, University of the Western Cape, 2020), 202.

6 Didi-Huberman, Atlas, 11.

7 Ibid., 9.

8 H. Belting, An Anthropology of Images: Picture, Medium, Body, T. Dunlap (trans.) (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2011), 16.

9 The Berlin Conference in 1884-5 defined the rules for claiming colonial territories among European empires. Portugal saw its 'historical rights' argument dismissed by the decision in favour of territorial 'effective occupation. This preoccupation set in place the so-called Pacification Campaigns which, in Pélissier's perspective, constituted Europe's declaration of war against Africa, since 'each imperialism' had to ascertain their claims 'with arms in hand'. See, R. Pélissier Naissance Du Mozambique. Resistance Et Révoltes Anticoloniales (1854-1918), vol. 1 (Orgeval: Pélissier, France 1984), 102.

10 Ornelas explains that from the Zulu Empire, two lines broke away: the Matabele commanded by Mozilikate (Mzilikazi), who crossed the Rand and raided in the Transvaal, and the Nguni warriors commanded by Manicussi (also called Sochangana, Ngungunyane's grandfather) that devastated the Amatongas, crossed the Incomati River and settled in Bilene. The latter was the origin of the Vátua Empire, better known as the Gaza Empire. In A. de Ornelas, Colectânea das Suas Principais Obras Militares Coloniais, Vol. I (Lisboa: Agência Geral das Colonias, 1934), 337.

11 For this historian, Mozambique and Mozambican people did not exist in 1890-5, but were more accurately African states often in competition for survival among themselves. See G.J. Liesegang, Ngungunyane, a figura de Ngungunyane, Rei de Gaza 1884-1895 e o desaparecimento do seu estado (Maputo: ARPAC, 1986), 83.

12 Ngungunyane, or Gungunhana in Portuguese spelling, the last king of the Gaza Empire, is considered 'the most important monarch in modern Mozambique History. See A.K. Smith, 'The Peoples of Southern Mozambique: An Historical Survey', Journal of African History, 14, 4, 1973, 601. This article adopts the spelling used by Gerhard Liesegang, an important historian of the Gaza Empire in Mozambican historiography. Portuguese spelling is kept in quotations or to express Portuguese colonial positions.

13 This included the Benguyo ceremony in 1894.

14 For one idea of photographic event, see Assubuji, 'A Visual Struggle, chap. 5, from p. 162.

15 E. Edwards, 'Photographic Uncertainties: Between Evidence and Reassurance', History and Anthropology, 25, 2, March 2014, doi:10.1080/02757206.2014.882834 (accessed 1 February 2016).

16 I.V. Gomes, 'Leonor Pires Martins, Um Império de Papel. Imagens do Colonialismo Português na Imprensa Periódica Ilustrada (1875-1949)' (Lisboa: Edições 70), in Comunicação e Sociedade, 29, 2016, 415-9, doi: https://doi.org/10.17231/comsoc.29(2016).2429.

17 See Assubuji, 'A Visual Struggle'.

18 E. Mondlane, The Struggle for Mozambique (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1969), 27. Among other aspects, Liengme depicted the queens in their village at Mandlakazi. While some images seem a spontaneous depiction of their daily life, others are clearly organised and depict symbols of a stratified social organisation.

19 The sketch is published in Paulo Fernandes' book Mouzinho de Albuquerque. The pages with the photographs or illustrations are not numbered. The author of the sketch could not be identified in this research.

20 See R. Pélissier, Naissance du Mozambique: resistance et révoltes anticoloniales (1854-1918), Vols 1 and 2 (Orgeval: Pélissier, 1984).

21 On violence, this article draws from Didi-Huberman, Atlas; and A. Feldman's Formations of Violence: The Narrative of the Body and Political Terror in Northern Ireland (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1991) and Archives of the Insensible: Of War, Photopolitics, and Dead Memory (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2015).

22 This 'excess' is discussed by many authors from various perspectives. See Didi-Huberman, Atlas; Belting, Anthropology of Images, 16.

23 By the eighteenth century, three distinct ethnic groups, the Tsonga, Chopi, and Tonga, inhabited southern Mozambique. Most became subjected to Sochangana Manukosi who created the Gaza Empire by amalgamating these ethnic groups and clans under military rule. See Smith, 'Peoples of Southern Mozambique', 565-80; W. Rodney, 'The Year 1895 in Southern Mozambique: African Resistance to the Imposition of European Colonial Rule', Journal of the Historical Society of Nigeria, 5, 4, 1971, 509-36.

24 J. Quintinha and F. Toscano, A Derrocada do Império Vátua e Mouzinho d'Albuqerque, Vol. I third edition (Lisboa: Nunes de Carvalho, 1935), 25. This publication won the First Prize of Colonial Literature in 1930. Although considering this an important source for the history of Gaza, Gerard J. Liesegang alerts to its purposeful attempt to create colonial myths that distort the historical context. A. Rita-Ferreira Colectânea de Documentos, Notas Soltas e Ensaios Inéditos Para a História de Moçambique (Portugal: Author's Edition, 2012), 267-73 emphasises the earlier presence of emigrant descendants of Karanga people from Great Zimbabwe in the bay already in the fifteenth century. During the nineteenth century, these people at the coast had commercial contacts with the militarily stronger Nguni. The Vátua are Nguni people who expanded their domains in the area since the beginning of the nineteenth century and formed the Gaza Empire. See, J.E. Vieira Fernandes, 'Cartas da Africa: Formas de Resistencia à Ocupação de Conquista Colonial do Sul de Moçambique no Final do Século XIX'. Trabalho de Bacherelato Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul. Instituto de Filosofia e Ciências Humanas. Departamento de História (Porto Alegre, 2019), 8.

25 Camfuma (also spelled Kamfumo) means the house of the local chief Mfumo and his people. Quintinha and Toscano, A Derrocada do Império Vátua, 37.

26 See Rita-Ferreira, Colectânea de Documentos, 267-73. For a deeper study on this subject, see E. Axelson, Portugal and the Scramble for Africa (1875-1891) (Johannesburg: Wits University Press, 1967).

27 See L. Hily, 'A Primeira Casa de Fotografia de Lourenço Marques, delagoabayworldpress.com (accessed 1 September 2020).

28 Later de Albuquerque was nominated governor general of the province. That diminished his powers of decision in relation to the territory's management and dictated his resignation and return to Portugal.

29 Mouzinho de Albuquerque, the Royal Commissioner (Comissário Régio) of Mozambique (1896-7), requested the presence of Dr Cabral, with whom he had a long and close relationship. Cabral was appointed secretary-general of the province on 26 March 1896. Was the photograph taken to signal the occasion? He temporarily replaced the artillery captain, João Pereira de Eça, and acted as governor of Lourenço Marques District. A friend of all the district governors, the young man 'later returned to Europe where [as] a skilled and intelligent businessman [he] marked his position in the world of Portuguese high finance. J. Azevedo Coutinho, Memórias de um Velho Marinheiro e Soldado de África (Lisboa: Livraria Bertrand, 1945), 486. The photograph is available at https://actd.iict.pt.

30 This is in contrast to a significant moment during his capture, when Mouzinho ordered him to sit on the floor to reinforce his new position as amatonga, an ordinary person deprived of social rights.

31 In 1911, the recently Portuguese-empowered republican government decided to repatriate four of the women who were still alive to their homeland, Mozambique. M. da Conceição Vilhena, 'As Mulheres do Gungunhana, in Universidade dos Açores Arquipélago. História, 2a série, III (1999), 414, http://hdl.handle.net/10400.3Z289. Their life in exile and return to Mozambique is narrated fictionally in Ungulani Ba Ka Khosa, Gungunhana (Lisboa: Porto Editora, 2017), 97-183. This photograph is also on the cover of that title.

32 The caption in the archive reads, 'Portrait of Gungunhana and his seven wives next to military. The image was digitised from the original proof (24x30cm, PRA/PM365) in January 2007 by the Institute of Tropical Scientific Research. Retrieved from https://actd.iict.pt (accessed 28 February 2018).

33 Hily's signature can be seen in some other photographs, for example Figure 4.

34 The photographs published in P.J. Fernandes, Mouzinho de Albuquerque have no page numbers. They are inserted between pages 128 and 129.

35 Published in 'Os retratos de Gungunhana', Grandmonde.blogspot.com, 20 April 2007 (accessed 27 March 2019). The photograph is credited to the Ângela Camila Castelo-Branco and Antônio Faria collection.

36 Gungunhana in Exile. Exhibition opened at Torre de Belém in Lisbon, 1993 (my translation).

37 Previously the buildings in Lourenço Marques were built with local materials and thatched roofs. After the great fire that destroyed the village, this kind of structure was forbidden and replaced by stone houses covered with French tiles or zinc sheets. See A. Linder, Os Suíços em Moçambique (Cape Town: Arquivo Histórico de Moçambique, 2001), 27.

38 A photograph of the Arc of Triumph can be found in the AHU - Digital Repository online archive, collection: Vários Aspectos Relacionados com Mouzinho de Albuquerque, em Lourenço Marques, ID no. 5316, access no. PRA/PM361. It acknowledges the photographer, Foto Hily Lda, whose stamp is visible. The caption is: Arc of Triumph erected at the entrance of 7 of March square, to receive M. Albuquerque, in L Marques on his return from the victorious campaign and saga.' It indicates the date the photo was taken as 3-09-1897. An additional note says: Arrived in Lourenço Marques, 3 de Setembro de 1897' The information seems to be inaccurate.

39 It became fashionable for the aristocracy to visit the African prisoners, the women bringing gifts and exchanging courtesies.

40 For a discussion on the polysemy of some pictures of Ngungunyane during the colonial and post-colonial periods, see S. Correa, 'As Figuras do Gungunhana no Caleidoscopio (pós) colonial', Vista no. 5 (Dezembro), 127-48, https://doi.org/10.21814/vista.3043 (accessed May 2020).

41 He made several trips to European countries, was received by high dignitaries and offered distinctions in England, Germany and France. Promoted to Major, he was nominated Royal Commissioner and later made Governor General for Mozambique (1896-8).

42 P.J. Fernandes, Mouzinho de Albuquerque, Um Soldado ao Serviço do Império - Biografia (Lisboa: A Esfera dos Livros, 2010), 128-9. [ Links ]

43 As one of the epic moments of the 'effective occupation' campaigns, the arrest of Ngungunyane inspired a movie called Chaimite, glorifying the Portuguese army. Between its launch in 1953 until 1969 it was screened 203 times in different lusophone countries. See R.A. Matos, C.M. Gomes Morais and M. Serva Pereira (eds), 'O Cinema em Moçambique -História, Memória e Ideologia', in Encontros com Moçambique (Rio de Janeiro: Editora PUC-Rio, 2016),102-6.

44 M.R. Miranda, O Último Rei de Moçambique (Lisboa: A Esfera dos Livros, 2013). [ Links ]

45 A. Telo, Moçambique, 1895. A Campanha de Todos os Herois (Lisboa: Tribuna da Historia, 2004), 84-5. [ Links ]

46 On the indexical excess in photographic images, see D. Poole, 'An Excess of Description: Ethnography, Race, and Visual Technologies', Annual Review of Anthropology, 34, 2005, 159-79; G. Baker, 'Photography between Narrativity and Stasis: August Sander, Degeneration, and the Decay of the Portrait', October, 76, Spring 1996, 72-113.

47 From ACTD - Arquivo Científico Tropical, Digital Repository. Collection: Varios aspectos relacionados com Mouzinho de Albuquerque, em Lourenco Marques, access no. 5311. Note the signature of the photographer at the bottom right side of the print.

48 For the peoples of the south, the term matonga meant a common man, deprived of any power, or political and social privilege. See Fernandes, Mouzinho de Albuquerque, 44. In more or less the same terms, the scene was also described in A.J. Telo, Moçambique, 1895, 84-5. The execution of two relatives close to Ngungunyane is controversial in the history of Mouzinho de Albuquerque. A description of Ngungunyane's arrest is carved in a bronze plaque at the monument dedicated to Albuquerque in Lourenço Marques. For a narrative of the campaign and the moment of the African king's arrest, see also A. Ennes, A Guerra de África em 1895. Cartas inéditas e um estudo de Paiva Couceiro. Prefácio de Afonso Lopes Vieira (Lisboa: Prefácio, 2002). Ennes was the Royal-Commissioner nominated to Mozambique with a mission to secure its southern region threatened by Great Britain and the Nguni-Gaza Empire. Mouzinho de Albuquerque wrote a detailed published report. Another Portuguese official also wrote an extensive report of the moment, which, while coinciding in many aspects such as dates, diverges in details of the narrative and intention, demystifying Mouzinho's heroism. M. Vilhena in the RTP documentary Gungunhana, the Defeated, produced in 1997.

49 Khosa is also an ethnic group considered part of the Tsonga (diverse peoples inhabiting southern Mozambique and Zimbabwe). Antioka, a village of the District of Lourenço Marques, had an important missionary station. See P. Harries, Junod e as Sociedades Africanas. Impacto dos Missionários Suíços em Moçambique (Maputo: Edições Paulinas, 2007), 258. For a discussion about the Tsonga, see S.J. Ngale, 'From Tsonga to Moçambicanidade: Civil Religious Dynamics in Mozambican Nationalism' (unpublished PhD thesis, University of Cape Town, 2011).

50 Also subjected by the Nguni warriors of Sochangane, the Ronga are an entity of the southern Thonga (Tsonga) peoples, organised in large political units such as the chiefdoms of Inyaka and Tembe. See Rodney, 'The Year 1895 in Southern Mozambique, 512. See also Smith, 'Peoples of Southern Mozambique, 570-2. The wax crown has different names among the peoples of the region. For example, in Ronga it is called ngiyana and in Zulu, isicoco.

51 Harries, Junod, 257. In this reproduction, however, the photographer's signature is not visible.

52 Henri Junod was a member of the Swiss Romande Mission, and came to Mozambique in 1889. Based at the Rikatla mission station, he made detailed studies of the Bathonga peoples inhabiting the south of Mozambique. He is the author of the well-known monograph The Life of a South African Tribe, published for the first time in 1912. Thonga or Tsonga peoples, also called Landins (Portuguese), were a conglomerate of various ethnic groups and expanded from the surroundings of Delagoa Bay to Sofala. They became absorbed by the Gaza Empire.

53 Harries, Junod, 257. This publication gives neither the name of the photographer nor the date on which the photograph was taken. For this discussion, see, for example, E. Shohat, 'Imaging Terra Incognita: The Disciplinary Gaze of Empire', Public Culture, 3, 2, 1991, doi:10.1215/08992363-3-2-41; E. Edwards, 'Photographic Uncertainties and between Evidence and Reassurance, History and Anthropology, 25, 2, March 2010. The original photograph can be found at the Swiss Mission Archive in Lausanne.

54 See Ngale, 'From Tsonga to Moçambicanidade', 38.

55 ACTD - Arquivo Científico Tropical, Digital Repository. Note that Lourenço Marques here is in reference not to the town but to the district, whose area combines various districts of what is today Maputo Province.

56 Mezzena and Serrano carried out accurate surveys of the banks of the Incomati River.

57 See Liesegang, Ngungunyane, 5.

58 These 'resident ambassadors' or representatives of the Portuguese Authority, also called counsellors, operated as quartermasters and resided within a close distance from the king's village, to whom they had easy access.

59 ACT (Arquivo Científico Tropical), Digital Repository. Note that the photographs of Ngungunyane and his people are inserted in a collection called 'The Border Delimitation Commission of Lourenço Marques, 1890-91'. The Gaza Empire was crucial in the definition of the south of Mozambique.

60 José Joaquim de Almeida produced a collection of documents published in 1898 called Dezoito Anos em África. The major reason for their publication was his defence against Ennes, Mouzinho and other members of the colony's administration who made accusations against him between 1895-6. The collection became an important source for that historical period. Liesegang, who has published extensively on the Gaza Empire's history, argues that Almeida was unfairly treated. See Liesegang, Ngungunyane, 5.

61 The Portuguese called Nwamantibyane Mfumu by the name Matibjana, chief of Zichacaha or Zixaxa, by which name he was also known. This is according to Ornelas, Colectânia das suas Principais Obras Militares e Coloniais, 67. These men went into exile with Ngungunyane, and never returned. Marracuene is located 30 km from Lourenço Marques and is the site of the first great battle of the campaign against the Gaza Empire.

62 See the earlier discussion on Figures 2 and 3.

63 L. Villarinho Pereira, Moçambique, Manoel Pereira (1815-1894). Fotógrafo Comissionado pelo Governo Português (Lisboa: Luísa Villarinho Pereira, 2013), 50.

64 Figure 12 is a detail of the photograph in Figure 6, cropped and enlarged in Figure 8.

65 The image features in Telo's monograph, Moçambique, 1895, 85. The publication credits the author Francisco Pastor, 1895. His name is also inscribed in the print and visible on the bottom left side of the image in Figure 13. He was an important engraver within the illustrated periodic press of Lisbon. Correa, 'As figuras do Gungunhana', 137.

66 Attributable to the manufacture of Afurada, Gaia. Polychrome decoration in part stamped, representing a landscape and figure of King. 13.8 cm. Private collection.

67 Manufacture of Coimbra, late nineteenth century. Polychrome, decoration representing king in the centre. Diameter: 21.7 cm. Private collection. Telo, Moçambique 1895, 86-7.

68 For the concept of photographic event, see Assubuji, 'Visual Struggle', 162-211.

69 A. Rocha, Moçambique, História e Cultura (Maputo: Texto Editores, 2006), 26. The caption reads 'Gungunhana, chief of Changanes of Gaza (engraving of Murdungaz)'.

70 The originals of most of Liengme's known photographs can be found with his papers in the archive attached to the Musée des Suisses dans le Monde at Penthes, Geneva, here referred as the Penthes archive.

71 Junod, for example, published several in his celebrated monographs The Life of a South African Tribe, Vol. 1 and 2. The paper further engages with some of these photographs.

72 This archive is here referred as Family folder.

73 The photograph was also published in Gungunhana em exílio. Catalogue and the exhibition at the Torre de Belém in Lisbon, 1993.

74 'Les Dernières Années du Regne du Roi, selons le Journal et les lettres du Dr. G. L. Liengme, medicin - missionaire au Mozambique (1891-1895)'. Liengme took a photograph of the Portuguese quartermaster Júdice Breyner sitting with Ngungunyane and his indunas under the tree where matters of empire were discussed. Breyner introduced Liengme to the king and facilitated his move into Mandlakazi. See Assubuji, 'A Visual Struggle', Annexure 3.

75 Photograph from 'Doctor George Liengme Papers' in the Penthes archive.

76 Indunas are chiefs, members of the local aristocracy and close to the king.

77 Several photographs taken by Liengme feature in Junod, The Life of a South African Tribe, Vol I.

78 The entry recalls a visit they received on Saturday, 1 July 1894.

79 From Liengme's diary, 'Les Dernières Années du Regne du Roi'. Transcript of 9 November, 1894, 132.

80 See Liesegang, Ngugunyane. A figura de Ngugunyane Nqumayo, Rei de Gaza 1884-1895.

81 Liengme diary, 129.

82 Feldman, Archives of the Insensible, 107.

83 Liengme diary, 130.

84 The two photographs in Figures 18 and 19 come from the Liengme papers at Penthes, Switzerland. The term 'metchacha' is referenced in the missionary's diary (see the translated file, pp. 147-8).

85 Ibid., 182-3.

86 For example, the photograph 'Swazi warrior' features in different publications such as the exhibition and catalogue Gungunhana em Exílio, already mentioned here, in Junod's The Life of a South African Tribe, Vol. I, and is on the cover of the book by Manuel Ricardo Miranda, O Ultimo Rei de Moçambique.

87 Ngungunyane's nominal mother, Impiumbekazane, was killed by warriors in 1897, accused of favouring the Portuguese. Liengme appears with her in one photograph. On the back of a printed copy is written that it was taken in Mandlakazi, 1894 (print in Family folder; the original is in Liengme collection, Penthes archive).

88 D. Wheeler, 'Gungunhana', in N.R. Bennett (ed), Leadership in Eastern Africa: Six Political Biographies (Boston: Boston University Press, 1968), 514. [ Links ]

89 Ibid.

90 War medicine was believed to give particular powers to the warriors and was taken before they departed to war.

91 Liengme diary. The identification of these photographs as referring to the Benguyo ceremony is an informed guess that comes from cross-references between texts and images.

92 Liengme diary, 131.

93 Ibid.

94 Hunting was a male specialisation and complex rituals and folklore were associated with hunting the big five. See D.W. Hedges, 'Trade and Politics in Southern Mozambique and Zululand in the Eighteenth and Early Nineteenth Centuries' (PhD thesis, SOAS, University of London, 1978), 57.

95 Junod, The Life of a South African Tribe, Vol. II, 52.

96 Hedges, 'Trade and Politics in Southern Mozambique', 74. Axes were an essential instrument; the cutting of one hamstring was enough to paralyse an elephant. Ibid., 59.

97 In his collection there are important photographs of the negotiators going to meet others and prepare for the delivery of the ultimatum. That occasion for the first time allowed the Portuguese cavalry near Mandlakazi. The second time it came, the African capital was burned.

98 See Correa, 'As figuras do Gungunhana', 129.

99 Parts of the monument are in permanent exhibition at the colonial history museum, the Fortaleza de Maputo. Mozambique achieved independence from Portugal in 1975 and became the Popular Republic of Mozambique. The country then entered a so-called civil war, officially known as the War of Sixteen Years. Its first president, Samora Machel, was killed when the presidential plane crashed in Mbuzini in 1986.

100 Photograph by Ricardo Rangel, published in Ricardo Rangel and Centre Culturel Franco-Mozambicain, Ricardo Rangel. Photographe du Mozambique (Paris: Editions Findakly, 1994), 48, with the caption 'The other destiny of the heroes.