Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Kronos

On-line version ISSN 2309-9585

Print version ISSN 0259-0190

Kronos vol.46 n.1 Cape Town Nov. 2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2309-9585/2020/v46a7

PART 2 REWORKINGS

From Illustration to Evidence: Centring Historical Photographs in Native Land Claims

Michael Aird

Research Fellow & Director, Anthropology Museum, School of Social Science, University of Queensland*; https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4874-7456

Can you describe your research area and where Brisbane sits in relation to your native title research?

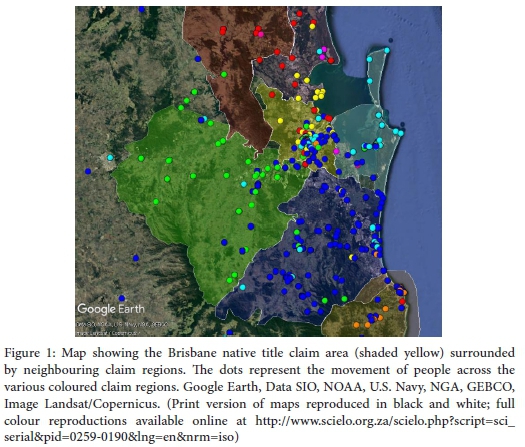

My main research area is the region surrounding Brisbane, the capital city of the State of Queensland. I particularly concentrate on the region within about 100 kilometres of the city, but at times I document individuals that may have come from 200 or 300 kilometres away, if these people had some sort of connection to Aboriginal families that lived closer to Brisbane (Figure 1).

What I am doing with my research is ignoring concepts of tribes and language groups and looking at real life events and people. I am attempting to determine their connection to their traditional country by the life choices they made. A person may have moved to Brisbane and died there, yet even though their family may have had very little money they somehow managed to take their family member back to their traditional country to be buried. This is just one example of a political or cultural tradition, or the sort of life events that I am documenting. By researching a broad range of these life events over time and over several generations, this can be used to question the accuracy or political biases of recent native title research.

Your research history intersects significantly with the broader historical context around this work. This also places you in a difficult position as a researcher, working from the margins.

I have been working with photographs since 1985 and was very fortunate to be invited to return to the University of Queensland in 2016, then soon after I was successful in securing a four-year Australian Research Council (ARC) Fellowship. It has been a wonderful opportunity to be able to bring together 35 years of research. A major outcome of this project, From Illustration to Evidence: The Potential of Photographs for Indigenous Native Title Claims in Australia, is where I contrast my interpretation of historical facts with other interpretations of history that are essentially aligned with modern native title politics.

Up until 1897 in Queensland there was not a specific legislation that controlled the lives of Aboriginal people. There was certainly mistreatment and Aboriginal people had no rights. Then in 1897 when the first legislation was introduced, the government started to be more strategic in the way it controlled Aboriginal people's lives. The government was getting organised to control what they called the Aboriginal Problem'; in America they called it the 'Black Problem'. The problem as they saw it was that Aboriginal people were multiplying. Many Aboriginal people were removed to reserves from their traditional country, sometimes great distances from where they came from.1

Aboriginal missions and reserves were once run by government or church officials. In more recent years these communities have come under the control of Aboriginal Community Councils. Many Aboriginal people still live in these communities, or are strongly connected through family networks. There are also many urban and remote Aboriginal families who have stayed in their traditional country, like my family. There are many differences in regard to life situations, with some families being disadvantaged in regard to education, employment and health outcomes, while other families may enjoy relatively good economic situations. Of course, there are issues of racism and skin colour that have influenced how people have been treated.

At times it has been the fair-skinned urban Aboriginal families who have had the freedom and economic good fortunes in life to remain in their traditional country. Some families like mine were relatively free to do what they chose and often chose to marry white people and there are many fair-skinned Aboriginal people like myself.

There were many aspects of loss of culture and merging into the European society. I am still very proud of my ancestors for the political decisions they made to stay in our traditional country and keep our families together. In modern native title politics there may be many conflicts. You may have essentially urbanised families, who on one hand have very strong connections to their traditional country, but how do they prove to a court how strong those connections are in a native title sense? When there is money involved, like if a coal mine is planned or any other sort of major infrastructure being built, there can be heated arguments and disagreements. This is not just an Aboriginal problem, it is a human nature problem. When money is involved, people argue, fight and disagree. Of course, the court and mainstream Australia expects us to be dark-skinned, to do traditional dances, speak fluent language and go out into the bush and hunt kangaroos. There are many conflicting political issues that Aboriginal people deal with.

Due to racism and various disadvantages, things didn't really start to get better until about the 1970s. A big turning point was the Racial Discrimination Act of 1975. It certainly didn't end racism and it certainly didn't end official discrimination, but from 1975 the government had to at least answer to accusations of racism and attempt to redress inequalities. So, this did create some opportunities, particularly in education. I was part of a big intake of Aboriginal students to enrol at university in 1987, but there were very small numbers of Aboriginal students before that. I graduated in 1990 from the University of Queensland, so I was among the first generation of significant numbers of Aboriginal people graduating from universities across Australia. These graduates moved into positions, like where I am now, as lecturers, curators, professional artists and historians. It was not until the 1980s when for the first time opportunities existed for Aboriginal people to knock on the door of institutions and ask for things like human remains to be returned and to start challenging the way our history was portrayed. It is a fairly recent thing for Aboriginal people to publicly assert who we are and our connection to the country.

The big thing that happened was spearheaded by Eddie Mabo, a man from the Torres Strait, in the far north of the state; he led a successful native title claim in 1992.2 This set the parameters of national native title legislation. Because of that you then have a rush of Aboriginal people all across the country asserting their tribe or tribal identity. Prior to that, when I grew up, it was not common for urban Aboriginal people to talk about what tribe you belonged to; instead, people mentioned family names and the place or community that they were connected to. There was a whole element of Aboriginal culture being kept low-key. My mother's generation at times may have been ashamed of being Aboriginal, ashamed of having dark skin.

It was only with the educational benefits and modern politics, and things changing in the 1970s, when for the first time a new generation of non-Aboriginal academics emerged who were radical in their thinking and wanted to work with Aboriginal people. I first started working at the University of Queensland in 1985 for one of those academics, Dr Peter Lauer, Director of the UQ Anthropology Museum.3 He employed me as a trainee to document archaeological sites. This was at the forefront of new opportunities opening up to young Aboriginal people like myself. In some ways, things are getting better for Aboriginal people, particularly with opportunities within cultural and educational institutions, but I am also fearful of the broader picture where the government and mainstream society wants simplistic and politically safe versions of Aboriginal history.

Going back in my career, in 1993 I curated the travelling exhibition and book titled Portraits of Our Elders.4It was my first major research project after finishing my Bachelor of Arts in anthropology in 1990. In the process of doing this research I went to our State Library and found a series of about 35 copy photographs. Each image had been copied from other images, but no information was provided as to when and where these images were taken or where the original photographs may be. Each of these copy prints had just two pieces of information attached: one bit of information was the title Aborigines - unknown location' and the only other information was the Library's copy negative number. Nothing else was attached to any of these photos as far as documentation. I made copies of these photos at the time and hoped that one day I could attach more information.

In 2010 I was part of an Australian Research Council project working with Jane Lydon, who is now based at the University of Western Australia in Perth. I was her researcher for Queensland on the Aboriginal Visual Histories research project.5 I had the great opportunity of being able to research whatever I wanted. It was this series of photos that were my base interest. I had been sitting on these photos for years and I wanted to know one basic question: were they taken in Brisbane, or not? They are in the Queensland State Library in Brisbane, so you could assume there is a chance they may be from the local area, but they may not be.

Why I became interested in the 1860s and 1870s photos was because I was asking questions about their lives and wondering what it would have been like for them to be living in an urbanised area like Brisbane, as opposed to those Aborigines that were living in more regional areas. I started to assume that maybe they were doing OK in life in general. Not owning property, not becoming rich, but the main thing was that they were surviving in their country. I think this is the most important political decision Aboriginal people could have made at that time.

It emerged that a few different photographers stood out, so my aim was to attach the name of a photographer to each of these photos. I started researching the photographers that were working around Brisbane in the 1860s and 1870s. After six months of solid research, I managed to attach names to many of them and I have kept researching and I am still attaching more names. Out of the original set of around 35 photos I can now attach the name Daniel Marquis to six of them. He was a very prolific photographer of Aboriginal people in Brisbane between 1866 and until he died in 1879. John Watson was another early photographer and I have identified four photos by him out of this group of unidentified photos. Other photographers of these images included William Knight, Chris Roggenkamp, Heinrick Muller and Edward Forster. I also managed to determine which images were taken in Brisbane and which ones were taken in other parts of south-east Queensland.

These photographers arrived in the region in the 1860s. I am fortunate when looking at the colonial history of my research area that Europeans only started living in the area as a convict settlement in the 1820s, and free settlement was not significantly established until about the 1850s. So it is quite a recent history, and almost the entire colonial history has been documented by photography. So, if you look at a person that was photographed in the 1860s and say they are around 50 years old, that person would have been living in the area prior to Europeans arriving.

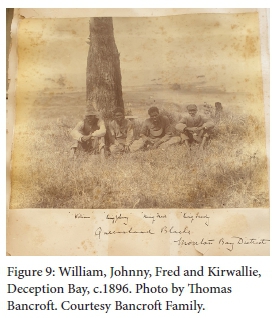

We know that photographs are used in the native title legal process. But they are essentially attached to documents and are very rarely - even when looking at countries like Canada that has a similar legal and native title system - they very rarely feature in the judge's findings or comments. They are essentially just 'illustrations'. That is why Joanna Sassoon, David Trigger and I chose the title 'From Illustration to Evidence'6 for our co-authored publication, which looked at a specific set of photographs taken by Thomas Bancroft in the late 1800s, and these photographs provide significant historical information, while also raising questions that may not be investigated by native title researchers.7

My research methodology asks lots of questions. I have to state that politically and professionally I have no standing in the native title industry. Lawyers, anthropologists, historians and other professionals working in the native title area have largely ignored my research to date. My published works are rarely referenced in native title research reports. It goes back to the fact that the courts listen to 'expert witnesses'. This raises the question of what you have to do to be an expert witness. I think it would be very difficult for me to be accepted as a native title 'expert' because I am Aboriginal and I am therefore considered 'politically biased'. Although I am doing my very best to portray history without bias.

I have spent most of my career working outside of the academy and I only have a Bachelor's degree. I do not research or write the same way somebody with a PhD would. Yet, here I am in a sense criticising the research methods of native title experts. As a purely theoretical exercise I am saying that my methods should be considered, alongside their methods. So, I can see my research methods being ignored; in fact, if I pushed my criticism too far, I think I would be actively denigrated and criticised. I am treading carefully. With the article that I wrote with Joanna Sassoon and David Trigger we had to be sure that every word is accurate because we are criticising other people's research.

Are you finding invented identities that need to be countered by research?

The complexities of urban Aboriginal society are at times quite different from remote parts of Australia. In urban areas, there has been a lot of movement of people, loss of culture and, at times, invention of culture. In fact, I am at times very critical of some people who to some degree have invented tribal identities. I am critical that well-orchestrated publicity campaigns by certain politically motivated individuals are potentially influencing the way native title research is undertaken, while also influencing what should be strict legal processes.

I am often asked the question, 'Who is the most important Aboriginal person in the community?' And I answer, 'Well that is obvious, it is the person that has had their picture in the local newspaper the most times.' This confuses people, they think I am joking, but I am not. Because it is whoever has run the best publicity campaign telling everybody that they are the most important traditional owner. That is what I feel my research is really questioning. Are we being tricked by well-orchestrated publicity campaigns? Some have been run since the early 1990s by some very clever, financially motivated individuals. They are reaping the benefits of maintaining those publicity campaigns.

We had the Commonwealth Games in my hometown in 2018; there was a degree of invention and branding of 'traditional language' and a branding of who was the most important Aboriginal on the Gold Coast. There are of course elements of traditional language that have survived. While there are not extensive language recordings from the claim area that I am from, in neighbouring areas there have been some very extensive language recordings done. The older generations, particularly people that I spent time with 20 or more years ago, that have since passed away, may not have spoken fluent language but they knew the basic principles of how the language was said. They knew a few words and they knew exactly how to pronounce them properly. But what I am seeing now is the corporatisation of language, the branding of language and it being used for publicity campaigns. I am looking forward to the Year of Indigenous Languages being over at the end of 2019 because there have been inventions of language. It is sometimes not an accurate portrayal of history.

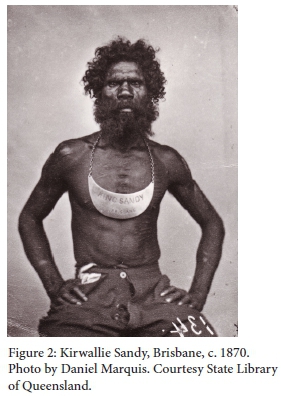

Kirwallie Sandy (Figure 2) is a good example of somebody who wore a breastplate saying he was a king. But in Aboriginal society there were no kings and there were no chiefs. We were imposed with the colonial legacy of the English invading Australia and expecting to find tribes with kings or chiefs. To this day we are still fighting against that legacy. Someone like Kirwallie was such a good-looking, strong, confident man. You can imagine people today wanting to be descended from him. So there are elements of invention at times, of people wanting to be connected to individuals in early photographs.

Many of the Aboriginal people in early photographs are considered apical ancestors in terms of the native title process. We use the term 'apical ancestor' to describe an Aboriginal person that goes back as far as European records go, or essentially to people that were alive when Europeans first arrived. To be a member of a native title claim group, proof of descent from an apical ancestor is required. But descent is not the only criterion considered by the court process. Proof of connection to country and cultural knowledge, as well as demonstrated proof that traditional cultural practices have been maintained since the time of European settlement, are just some examples of what the native title legal process expects to see demonstrated.

One of the old people I have come across is Billy Andrews (Figure 3), who was photographed with a top-hat on and breastplate and he looks stunning, and naturally people would want to be descended from him, but my research indicates that he does not have any descendants. Yet he is still listed on a native title claim as an apical with wrongly attributed descendants.

Can you describe your research methodology?

The research methodology that I am using in one sense ignores references to tribal boundaries, to clan groups and language boundaries. In 2012, I curated an exhibition in the State Library, focusing on the work of anthropologist Norman Tindale, whose work still carries great authority when it comes to native title claims. It was a fortunate opportunity for me to get to know Tindale's work. He is famous for producing a set of maps of tribal areas all over Australia. Many more tribal maps have been produced by other researchers; some are based on Tindale's work, but virtually all of these maps are disputed by some. Instead, I just focus on 'people' and significant events in their lives. Then I place those life events as dots on Google Earth (see Figure 1). I achieve this by combining decades of historical and genealogical research and extracting the locations of life events of individuals, then placing these on an Excel spreadsheet that is then converted to dots on Google Earth.

I research official records and lots of obscure sources. Facebook is one of my research tools, as people are continually sharing information about their family history. Sometimes there can be heated discussions with individuals trying to assert themselves publicly for native title political reasons. Other times people get angry with something somebody else says and contradictory debates follow. Many Aboriginal people are very enthusiastic amateur historians. It is amazing the effort some people put into researching their history and sharing documents within families. I am finding both accurate and wrong versions of connections to country and apical ancestors posted on Facebook. These inaccuracies are not intentional, and attempting to correct them can be very controversial within families. These wrong versions of history are very useful, because I document these statements and contrast this with my research and question why I may think something is wrong. It is very useful to know why people believe they are connected to an apical ancestor, even if what they believe is wrong.

I am continually searching for bits of information and each time I find a photo of interest, I copy it. It is a democratic way of doing research as whenever I find a photo of an old person that interests me, I am then forced to do some sort of biography of them and figure out who their parents are and who their descendants are and where they lived and died. Or I might just add their photo to my research documents and leave a blank about them, and this reminds me that I need to keep searching until I can find out more about them and where they fit in from a native title perspective. Especially if somebody is in the media and publicly asserting themselves as an important traditional owner of the region, well then I feel compelled to do a biography of them and figure out where they fit in and what apical ancestors they are descended from.

I did my best to try and show how the dots change over time. For example, I can show the dots for one person, then add their children, then grandchildren and I can demonstrate how the dots spread over time. Where a person is born and where they die, where their children are born, where they get buried. These are very significant life events. If a person gets arrested and gets sent to prison, where they get sent to prison may not be in their traditional country, and they most likely do not go there by choice, but that location will be included in my research as it helps to demonstrate broad patterns of movement over time.

Another thing to consider when tracking movements is that people may have been working on boats. For example, Kirwallie Sandy went to the Mary River about 300 kilometres to the north of Brisbane, because a non-Aboriginal man had interests in finding timber, so Kirwallie and another Aboriginal man were asked to join them for security in case they came across not so friendly Aboriginal people. So, I look at it, that he agreed to go on that trip knowing that he was going so far north, maybe he agreed to travel that distance because he felt comfortable and possibly knew people up there. To my knowledge he only crossed to the southern side of the Brisbane River once, but he covered a considerable distance to the north.8 I am not saying that by me placing a dot on Google Earth 300 kilometres to the north of where he normally lived, indicates a traditional connection, but it supports the points I am making as far as the importance of tracking movements and looking for patterns that may or may not align with current native title claim research.

Looking at photographs involves detective work of matching up patterns in carpet, skirting boards, curtains and directions of light and whatever features I can find that have helped me identify many of these photographs. Out of the group of unidentified photos I began researching from the State Library, there are still two photos where I cannot name the photographer. These two photos may well have been taken in the Brisbane region, so I will keep studying painted backdrops in early photographs until I can match up this backdrop to a photographic studio.

What surprised me is that the bulk of the images were taken by Edward Forster in Maryborough, on the extreme northern end of my research area. We need to look at this woman wearing a possum-skin cloak made up of multiple possums (Figure 4). The tradition of Aboriginal people making and wearing these cloaks was a very strong tradition in the south of Australia, in Victoria, where it is much colder than Queensland. It was a tradition in Victoria that was well documented by photography and there are many photos of men and women wearing these cloaks. Yet in Queensland there are written records of these cloaks existing, but Queensland is not as cold as Victoria, so there is only one photo of a person wearing a possum-skin cloak in Queensland. It is potentially the most northerly example of this cultural practice being documented by photography. For some time, I was convinced this photo may have been taken in Victoria. Then in 2014 a private collector, Marcel Safier, sent me a copy of an image that on the reverse was stamped with the details of the photographer Edward Forster of Maryborough. This image featured another woman wearing a government-issue blanket, in a similar style to the way the possum-skin cloaks were worn. I studied these two images and noted that the two women are standing on the same patterned carpet and the skirting board matched. I could then confirm that these two women are in the same studio (Figure 5).

I am writing a book chapter at the moment, where I am looking at objects and linking them to issues of native title politics. There was a particular style of bag with a diagonal pattern through it that was made in the broader Brisbane region. This style of bag appears in various collections around the world. The problem is that most of the bags came into the institutions with very little information. Some of them were attributed as coming from Stradbroke Island. What has happened since then is that bags that look like these have had the location of Stradbroke Island attached, even if they originally had a more general location attached such as Brisbane region or Moreton Bay. So the name of one island is being attached, and that may not be accurate. I am now getting critical that this name may be getting attached as part of a branding exercise. Aspects of culture being claimed by one group. As if only one group of people made that bag and other nearby groups did not. What I am now finding is that that style of bag was made within about a 200-kilometre radius from Stradbroke Island. I am writing to correct this aspect of history and state that this bag comes from other places.

In the 2012 exhibition you curated, the subjects of these photographs were incarcerated. We similarly see an 'incarceration' of image, as the photograph becomes fixed in Tindale's discourse.

For the exhibition I did in the State Library in 2012, I spent 12 months focusing on the work of Norman Tindale.9 For one year I talked to people about this man, and I think in general many Aboriginal people dislike him while many non-Aboriginal experts in native title respect him, because they use his work. In many native title court cases there are debates as to who the traditional owners are of a particular region; the judge will ask, 'What did Norman Tindale have to say?' To quote the linguist Petter Naessan,

The Board of Anthropological Research and Tindale were caught up in a notion of blood purity, genetic purity and cultural purity. My impression is that a lot of the material that they recorded and a lot of the stuff that was published became the yardstick to measure contemporary Aboriginal culture. For instance in native title cases, people's memories, people's knowledge of sites and so forth are held up in a court room, held up against what Tindale wrote. He has become the yardstick; the legacy of Tindale overshadows them.10

Naessan has worked with Aboriginal people who feel quite angry that Norman Tindale's opinion about their country overrides their opinion of the location and boundaries of their country. His handwritten genealogies are an important aspect of his work that gets used in native title cases.

In the 2012 exhibition I worked with a friend and artist, Vernon Ah Kee. He grew up with a connection to these photos because his grandmother would keep small copies of three of these photos in her purse, when he was a young teenager in north Queensland. She had a photo of her husband, Vernon's grandfather. The other two photos were of her parents, Vernon's great-grandparents. They were photographed in 1938 when Norman Tindale did a scientific tour of the east coast of Australia, which took him 18 months. He spent six months in Queensland, so that was the focus of my exhibition. I used photos from seven different communities and how people today connected with them.

Vernon's connection to these photos is incredible. He first got copies of these photos from the State Library of Queensland, then a decade or so later he visited the South Australian Museum, where the originals are held, and got high-quality digital scans from the original negatives, which he then turned into works of art. Two to three metre works. They are stunning, the way he has revisited these photos (Figure 6).

In a sense all the people, the 1,200 or so people that I looked at from seven communities, were victims. They were all incarcerated on Aboriginal settlements, incarcerated on government-controlled settlements, and they did not have the power to say 'no' to their photos being taken. They had to do what they were told. They handed over their genealogical knowledge to Tindale, and all types of other personal information. These genealogies have become central to many native title claims. You have people picking out bits that suit their purposes. A simple handwritten note that Tindale documented in 1938, now you have people ending up 'in' or 'out' of a claim based on a simple scrappy note. I spent 12 months studying Tindale and the six months of work he did in Queensland in 1938. I found his genealogies from this period of his research very superficial. They were based on whatever he was told during his brief interaction with the people at each community he visited. I am critical of Norman Tindale's genealogical research conducted over a period of around six months in 1938, in contrast to my research that has been conducted over a 30-plus-year period.

Looking at these small two-inch proof prints, this is what Vernon and I based the exhibition on. You can see photos of Vernon's great-grandmother with one of about five cards, documenting aspects of her life, including her entire life history of menstrual cycles. I think the staff of the South Australian Museum were a bit ashamed of the way Tindale attached a scientific number to each of these people. But we made a big issue of these numbers. In fact, all the large feature photos are in numerical order; we made a feature of 36 of the 1,200 photos and many of the other photos we put up as smaller images. The exhibition was quite moving. It struck me, I was getting to know these people and their descendants.

In your 2014 exhibition, how was the image read? People are not 'incarcerated subjects'. Did you undo assumptions about the relationship between photographer and subject and turn this into a way of questioning connections to country and belonging?

In 2014 I did the exhibition 'Captured: Early Brisbane Photographers and Their Aboriginal Subjects' in the Museum of Brisbane.11 I revisited the research I did in 2010 and I just concentrated on four of the photographers, John Watson, William Knight, Thomas Bevan and Daniel Marquis, as they were photographing Aboriginal people in Brisbane in the 1860s. I ignored photographers that came to Brisbane in the 1870s and later. By just using the photos from four photographers I had enough images to do this exhibition.

By looking at the volume of photographs of Aboriginal people that were taken in Brisbane in the 1860s and 1870s it has convinced me that large numbers of Aboriginal people were living in or visiting this emerging city around that time. In modern native title politics it is thought that few Aboriginal people lived in Brisbane in the decades soon after colonisation. The large number of people I am looking at in photographs proves that many Aboriginal people came and went from Brisbane. So this raises a big question: if these people are in Brisbane getting photographed - it can be proven by the images that they are in Brisbane; we also know that the majority of the photographs were taken in three city streets - how far have they travelled? Are they from Brisbane itself, or how far have they come from to get there?

The following quote by Thomas Welsby was a guiding factor in developing the exhibition:

To me the Aboriginals of my early youth were no more than the people of the day, their numbers were in hundreds in our towns, their ways and living nothing to dwell upon. Today, to my children, they are a wonder and a mystery.12

Thomas Welsby was a well-known amateur historian and he had close links with Aboriginal people. In this quote, Welsby reflects on his time as a teenager when he got a job in Brisbane in a bank in the 1870s. Here, he is talking about Aboriginal people as 'people'. This guides my research, even though it sounds ridiculously simple, but rather than thinking of Aboriginals as mysterious people that lived a long time ago, I think of them as just being people. I think about human nature.

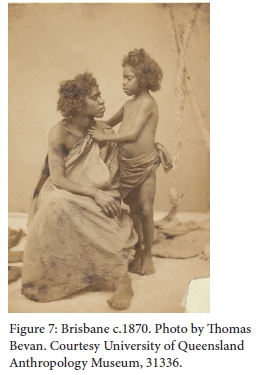

Some people who saw this exhibition were a bit disturbed by how uncomfortable the subjects looked. But if you think about the photographic technology of the 1860s and 1870s where there were exposure times of possibly 60 seconds, many of these people would have had their heads screwed into clamps to keep them still. If you look at this photo of a mother and daughter (Figure 7), the girl has one leg going straight up and down; it is likely there would be a metal pole going up behind that leg and it would support the clamp that is attached to her head. The photographers were very good at hiding the clamps. When considering how hard it is for a child to stay perfectly still for extended periods, it is telling that these people in this photo agreed to participate in this process of having their photo taken.

In the book that Jane Lydon edited I talked about my basic methodologies of research to attach names to photos.13 After bringing these photos together in the 'Captured' exhibition, I really started to look at these photos in a new light. I started to challenge what some people thought of these images about the sitters not looking comfortable, and remembering back to the head clamps and people having to stay still for at least maybe 60 seconds. Well, nobody looked comfortable in photographs from that era.

I think about what the photographer may have done to coerce these people into participating. These people would have come from the traditional lifestyles that they had been living. I am sure they would have demanded some form of payment. I see them as being smart and negotiating something, knowing that the photographer is going to sell these images and make money. If the photographer was going to make money from their images, I am sure they would have wanted things like tobacco or clay-pipes or something else as payment. So I see people that have entered into an agreement, not victims.

The big question that my research is trying to ask is, if these people are willingly involved in this process, then what sort of relationship did they have with the photographers? I imagine them walking down the street in Brisbane and possibly the photographers knew them by name and maybe they said 'would you like to come inside and have your photograph taken' and they agreed. But how does that relate to their lives in general? My question is, if I am looking at people who look willing to be there and look strong and confident, what story does that tell about their life in general? Also, what story is told when looking at photos of people who look sad and defeated? I ask, what does that mean about their connection to the country? Have they been forced off their traditional lands, are they dispossessed?

The photographs presented at the 'Other Lives' workshop at UWC relate to legal notices, and changing politics with claims. The way in which you employ them casts critical aspersion on legal assumptions and adopts the approach of treating 'people as people'.

When describing native claim boundaries I use a colour coding system in my research. The colours (see Figure 1) represent each recent claim boundary, where there is quite often disagreement about who is in and who is out of these areas. So I do not use the names of the tribes that are being used in a modern political context, as I find those names are problematic. Even the spelling of the names can cause political disputes. Instead, I talk about the 'dark blue tribe', the 'light blue tribe', the 'green tribe' and so on, just to try and simplify things. With each shaded area you now have those currently involved with native title claims attempting to demonstrate their ancestor's strong connections to these shaded areas. But their ancestors often didn't stay within the claim areas. I am tracking movements and finding fluidity that at times does not match with the politics of today. The previous claims over the Brisbane region have the Brisbane River running through the middle of the claim, and my research is showing that the river was a significant geographical boundary between people's movements, but this is not recognised in the claim boundaries that have been proposed.

A public notice advertising the details of an authorisation meeting to discuss a claim is in itself a very important historical document (see Figure 8). This may appear as nothing more than a formality, but these documents mark an incredibly important moment in time with any native title claim. Once this notice goes in a newspaper, it essentially starts what often proves to be years of political disagreements within Aboriginal family groups. This notice relates to the claim over my traditional country, the Gold Coast, Beaudesert, Beenleigh area, between Brisbane and the New South Wales border; it lists 19 apical ancestors and I am descended from three of these apicals.

I can highlight just a few of the apicals and how they are described in the public notice. For example, 'Polly Allan/Dalton' - she was never named 'Polly Dalton'; her daughter Eva married Thomas Dalton, so there is something wrong with this research. 'Kipper Tommy Andrews' had one daughter, who was known as 'Lizzie Kipper Tommy'; that was the name she used on her marriage certificate. Not 'Lizzie Kipper' as she is described in the public notice. She married a man called Dan Malay who was born in Singapore. When she died in 1915, her husband lived with my grandmother's older brother; my mother can remember Dan Malay and his vegetable garden. Then when my grandmother's brother died, Lizzie's gold ring was given to my grandmother, and the ring is still in our family today. To me she is a real person. I have a copy of her death certificate, where my great-grandmother's older brother certified the death.14 Her death certificate states that she had no children. Yet you now have her included on a claim that believes she has descendants. Her father should not be listed as an apical because there are no descendants. The same with 'Billy Andrews'; I am convinced that he had no children.

The place where the meeting was held was a very strategic move by the organisation that hosted this meeting, in a community hall that would not have been known to the majority of community members, making it difficult for many to get to. Every dot point in this advertisement has political implications. Soon after this claim was first authorised, there were nine applicants elected to represent the broader claim group. They were elected and five sided together, and the other four had different political agendas, but were powerless to influence most decisions. I stay out of these politics and I feel fortunate to be able to observe these processes. I am very happy to be watching this from a distance.

The article that I wrote with Joanna Sassoon and David Trigger15 focuses on the four men in this photograph, and focuses on this photo (Figure 9). Here you have four men sitting together and I ask the following questions: How are they related, do they like each other, and why are they sitting together? I have tracked the history of this photo. It was first published in 1979, so there is no reason for it to be ignored in native claims. Earlier this year we tracked down the original photograph that has been published many times, and is still in the hands of the granddaughter of the original photographer. So we can now see the original caption ('"William" "King Johnny" "King Fred" "King Sandy" - Queensland Blacks - Moreton Bay District'). Working with the four men in the original photos I have managed to track down 14 photos of William, 13 photos of Johnny, three photos of Fred and 17 photos and 10 artworks of Kirwallie Sandy.

Going back to this very basic question, why did four men sit on the ground and have their photo taken? What does that one moment challenge us to think about today? Kirwallie Sandy does feature in several native title research documents in the Brisbane region. But William, Johnny and Fred are ignored in native title research.

Looking at their movements over their lives, these are the places they visited (Figure 10). When looking at where Kirwallie moved, he did not go south of the Brisbane River except for in 1900 when he went to Wynnum, where his daughter was living at the time, and that is where he died.16

Oysters were plentiful, the finest growing at Hayes' Inlet, which, was also a great place for mud crabs. There were between 20 and 30 blacks, camped mostly in Bett's paddock, half way between Woody Point and Clontarf, who would occasionally go 'walkabout' and do odd jobs for the residents, but who mostly lived by fishing and oystering, the Government supplying them with boats. King Sandy was 'boss'.17

This quote describes Kirwallie controlling seafood resources in the Redcliffe region and this is where records indicate was his main place of residence, which could be described in a native title context as his core traditional country. Kirwallie and his descendants are represented by yellow dots, so as you look at the places his daughter visited, you will see a slight spread of yellow dots on a map and then down to his grandchildren an even bigger spread.

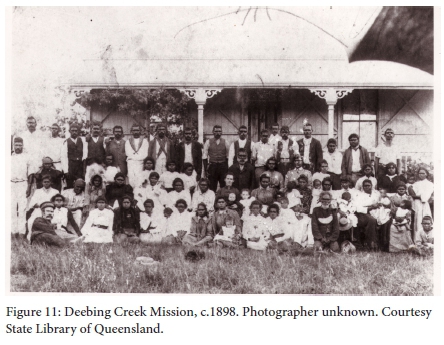

From the green claim area I have this photo of a large group at Deebing Creek Mission in around 1898. I have managed to identify several individuals in this photograph (Figure 11). Within this group is Roger Bell; he was the grandfather of Neville Bonner, who became Australia's first Indigenous Federal Politician. Roger and his family are well documented and I have managed to place numerous green dots of where he and his children moved over their lives (Figure 12). This in turn could be seen as where Roger Bell felt comfortable to be throughout his life. Due to modern politics, it has been decided by lawyers and anthropologists that his family belong to the area to the north of the green claim region. Recently his descendants were told that if they attended a native title claim authorisation meeting that was held at Ipswich in the middle of the claim area, they would be removed by security guards. That is exactly what happened; they turned up and they were excluded from the meeting. They were told that their country is to the north of the green claim area, yet look at this man's movements over his life. He was comfortable moving in this whole area, but more so to the south rather than the north.

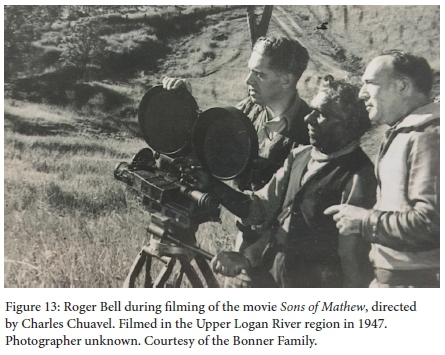

In 1949 the Australian director Charles Chauvel made the film Sons of Mathew in the Beaudesert region. Roger Bell was employed as an actor (Figure 13).

The script called for an Aboriginal stockman for the droving scenes and Chauvel secured the services of Roger Bell of Hillview. Roger was a full-blooded aborigine born on the Logan River and one of the last living men of the district to have been initiated according to tribal law. Most of his life he had been a stockman and a very good one.18

This quote is not historically accurate as Roger Bell was born north of the green claim area in the region of Esk, and this was documented on his marriage certificate and again on his death certificate. In recent years lawyers and anthropologists working on native title claims have used the information on these official documents to exclude the family of Roger Bell from the current claim over his traditional country. The fact that Bernard O'Reilly in this book can state that Roger was born on the Logan River near the New South Wales border to the south of the green claim area, indicates that later in his life he walked around this area with great comfort and confidence that portrayed an image of wherever he walked he was comfortable and he had a connection to that country. This highlights the fact that towards the end of a person's life, where others believe they were born may not be the same as where they were actually born.

It is of concern that some Aboriginal families are being excluded or included in native title claims based on one death certificate or some other written record. Documents such as death certificates often contain misinformation based on what somebody was once told, or assumptions they may have made, then this in turn is documented and becomes an accepted fact by some, when it may not be true.

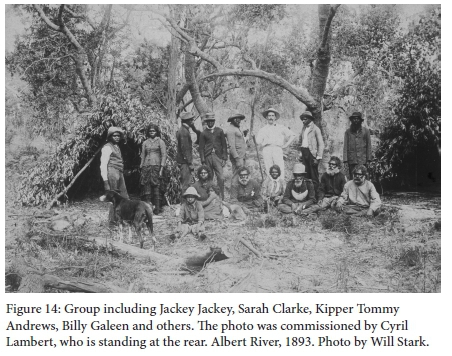

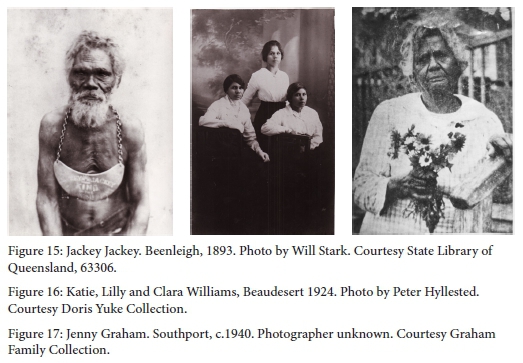

The dark blue claim area covers the region that includes my traditional country. This photo of a group from the dark blue area includes two of my ancestors (Figure 14). One of them is my great-great-great-grandfather, who was known by the name Jackey Jackey (Figure 15). His daughter, my great-great-grandmother Emily Jackey, married a man from the upper-Logan River region, William Williams, and spent the rest of her life there.

The cover of the book Portraits of Our Elders features three daughters of Emily Jackey and William Williams (Figure 16). Aboriginal people wanted to stay on their traditional country and they were prepared to work hard and conform to European work practices to remain on their country. Photography is part of this story. I have photos of all 12 siblings in my great-grandmother's family. The fact that I can find photographs of all these 12 siblings demonstrates that they had a degree of wealth and stability in their lives. For them to be able to have these photos taken, then for the descendants to look after them and share these images among families, demonstrates that stability.

Moving to my grandmother's grandmother, Sarah Clarke, she was also in the group photo on the Albert River; she had minimum movements over her life. She spent some time north of Brisbane, prior to settling on the Albert River, then she spent her later years at Southport on the Nerang River. Her daughter, my great-grandmother Jenny Graham (Figure 17), who died when my mother was a young girl, had 11 children. I have documented the movements of Sarah Clarke's descendants and represented this with dark blue dots (Figure 18). You can see the spread of the dark blue dots, that move particularly into the light blue area. But in modern politics our family is excluded from the native title claims over the light blue area. Movements like this form a big part of my research findings and are essential in understanding traditional movements of families over time and contrasting this to modern native title research and politics.

In another photograph you can see my grandmother, the baby of the family with her father, Andrew Graham, who was of Scottish and Irish descent (Figure 19.)

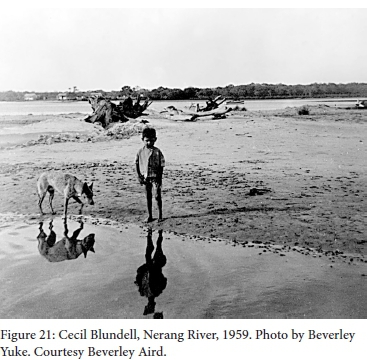

Standing at the rear of this photo is my mother's Aunt Mary. I knew her quite well as a young child; she died in 1976. I spent a lot of time in her house at Brighton Parade, Southport, and my grandmother's house, the house my mother grew up in, was next door. This was the house where my great-grandparents, Jenny and Andrew Graham, settled in the 1880s. This group photo was taken in front of Jenny and Andrew's house in about 1905 (Figure 20). Here is a photo taken across the road of the Nerang River; this photo was taken in 1959 by my mother (Figure 21), and then you see what it looks like today (Figure 22). What was once river and mangroves has been reclaimed and is now a football field and the tourist town of Surfers Paradise can be seen in the background. From that place, if you turn around and look to the west, you see a high-rise building complex on top of where my Aunty Mary's house and my great-grandparents' house used to be. The house where my family were sitting in the 1905 photo is somewhere in the middle of this high-rise building complex today (Figure 23). I am documenting movement over time and the changes to the landscape.

To go back to one of my earlier comments about looking at people 'as people', here I think of basic human nature. I think of my great-grandmother when she was a young teenage girl and she formed a relationship with my great-grandfather, who was a few years older than her. They started having children in about 1873 and we know that her first four children out of 11 were born in what is now the light blue claim area. I have thought about this: if she was a teenage girl having children, you would assume she is having children where there is family support. So now we have people saying the light blue area is not her country and instead she belongs in the dark blue area. We know that after having four children in the light blue area, she then moved to Southport in the dark blue area, because her non-Aboriginal husband got a job as a river pilot (harbour master) at Southport. This was a decision to live somewhere because of economic factors. Because she lived at Southport from the late 1870s onwards, people now believe that she was born at Southport, where photos of her were taken. There is this assumption she was born there, when in fact she was born on the Albert River, which is about 40 kilometres to the north. When she formed a relationship with my great-grandfather, he was living at Amity on the northern end of Stradbroke Island, working as a fisherman and catching dugong at a place that is now in the middle of the light blue claim area. He appears in an 1873 diary, so I know exactly where he was at that time.19

The first question people often ask me is about European influences, things like the cattle industry and men droving cattle from one place to another. The men probably had enough freedom to decide which contracts they would take droving cattle, and you can see patterns of where people chose to go, whether they went north, south, east or west. They probably agreed to go where they had familiarity, or knew people or were related to them.

It is often modern political factors that exclude some families from native title claims. I therefore think back to why people made certain movements in their lives. There is an element here of connections of people in the past staying in modern claim areas that their descendants identify with, but there are also patterns of movements into other areas. Today there are maps that show the light blue claim group publicly stating that their area covers a region that I see as an important part of my traditional country. My research documents traditional patterns of movement, while contrasting this with modern native title boundaries where politically motivated individuals have decided who is in and who is out.

* Editors: Michael Aird presented the keynote lecture at the 'Other Lives of the Image' workshop at the University of the Western Cape in October 2019. This article is an edited version of the lecture transcript, presented as a series of questions and elaborated responses that explore how the author puts photographs to work in his extended research project. The editors thank Michael Aird very sincerely for this collaboration.

1 The Queensland Government introduced the Aboriginals Protection and Restriction of Sales of Opium Act in 1897. This legislation resulted in many aspects of Aboriginal people's lives being controlled and children being separated from their families and often removed to missions and reserves far from their traditional country. Various forms of this Act were in place for over 70 years.

2 The Mabo vs Queensland decision in 1992 was followed by the Native Title Act in 1993; https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mabo_v_Queensland_(No_2).

3 I now hold the position of Director of the UQ Anthropology Museum.

4 M. Aird, Portraits of Our Elders (South Brisbane, Australia: Queensland Museum, 1993). [ Links ]

5 Aboriginal Visual Histories: Photographing Indigenous Australians 2008-2011 (DP0878567).

6 This was also the title for our ARC research project, 'From Illustration to Evidence in Native Title: The Potential of Photographs' (IN170100009).

7 M. Aird, J. Sassoon and D. Trigger, 'From Illustration to Evidence: Historical Photographs and Aboriginal Native Title Claims in South-East Queensland, Australia', Anthropology and Photography, 13, 2020, 1-27. [ Links ]

8 C.C. Petrie, Tom Petries Reminiscences of Early Queensland (Dating from 1837), Recorded by His Daughter (Brisbane: Watson and Ferguson, 1904). [ Links ]

9 Norman Bartlett Tindale, born 1900, died 1993; https://www.slq.qld.gov.au/discover/exhibitions/transforming-tindale.

10 Quote from the Transforming Tindale exhibition held at the State Library of Queensland, 2012, from an interview with Dr Petter Naessan, linguist, University of Adelaide, 9 February 2012.

11 See https://www.museumofbrisbane.com.au/whats-on/captured-early-brisbane-photographers-and-their-aboriginal-subjects/.

12 T. Welsby, The Collected Works of Thomas Welsby, Vol. 1, A.K. Thompson (ed) (Brisbane: Jacaranda, 1967), 17.

13 M. Aird, Aboriginal People and Four Early Brisbane Photographers', in J. Lydon (ed), Calling the Shots: Aboriginal Photographies (ACT, Canberra: Aboriginal Studies Press, 2014), 132-54.

14 Death certificate 1915/001901/003145.

15 Aird, Sassoon and Trigger, 'From Illustration to Evidence'.

16 Petrie, Tom Petries Reminiscences.

17 U. Parry-Okeden, 'Redcliffe in the Early Eighties: Many Memories of the First Settlers', Sunday Mail, 9 March 1930, p. 21.

18 B. O'Reilly, Over the Hills (Brisbane: W.R. Smith & Peterson, 1963), 123. [ Links ]

19 Gustavus Birch Diary 1873-1874. State Library of Queensland, M779.