Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Kronos

On-line version ISSN 2309-9585

Print version ISSN 0259-0190

Kronos vol.46 n.1 Cape Town Nov. 2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2309-9585/2020/v46a5

PART 1 LATENCIES

The Brown Photo Album: An Archive of Feminist Futurity*

Jordache A. Ellapen

University of Toronto; https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1060-5428

ABSTRACT

This photo-essay considers the other lives of family photographs by offering an analysis of my mother's collection of professional studio portraits and other vernacular photographs shot between the mid 1950s and late 1960s. How do we read the photo-archive of an 'Indian' woman born in 1941 to parents who were wards of the colonial state? A woman who was one generation removed from the sugar-cane plantations and coal mines where Indians were indentured as a coercive labour force? Influenced by Santu Mofokeng's project The Black Photo Album and Tina Campt's method of 'listening to' rather than 'looking at' photos, I refigure the family photo-archive to produce The Brown Photo Album, which is an experiment in seeing and being seen. In a context where the institutional visual archives of colonialism and apartheid have trained South African publics to see and thus know the Indian in very specific ways, this article redirects us away from the violence of the visual to the relationship between race, aesthetics and affect. It positions the family photo album not only as an alternative archive of the Indian experience but also as an archive through which we can begin to comprehend the Indian experience otherwise. This project probes the making of Indianness in the Natal Midlands, shifting the lens from urban centres like Durban and Johannesburg. As a work in progress, I present The Brown Photo Album as an experiment, an iteration of a project, a praxis of refiguring family photos in order to understand what this archive can reveal about our past, presents and futures.

The Brown Photo Album: An Archive of Feminist Futurity is an artistic project that refigures the photo-archive of my mother, Velliammah Ellapen (née Moodley), an Indian South African woman born in 1941. In this iteration of The Brown Photo Album, I focus on a collection of her professional studio photos shot between the mid 1950s and late 1960s in Ladysmith by Bully Narrandes, an Indian photographer who ran the now defunct Victory Studios. Since I was young, I have been drawn to my mother's performances in these photos and her attention to style and fashion. The photos directed me to her dreams and desires and offered a sense of her personhood before she became a wife and mother. In the many conversations I had with my mother, the photographs activated her memories of growing up in a large family. She was the second youngest child (the youngest daughter) out of ten siblings and recalled vividly her experiences growing up in a rural area of KwaZulu-Natal with her brothers and their families. In the early 1950s they relocated to Ladysmith, where most of her professional studio photos were shot. I began to grapple with the significance of her photo-archive and her desire to be photographed when I realised that the photos were a site of remembering. The photos became a portal into another world; she talked about the pleasures of growing up on a farm among animals and the hills and valleys of Van Reenen's Pass. The photographs also activated memories of growing up in a context defined by various forms of racial and gender-based violence within the 'home-space'. Even though her portrait photos concealed the violent social worlds that informed her positionality as an Indian woman, I realised that they could not be understood outside of the context of indentureship and its afterlives.

As a child, I recognised that my mother's photos were precious to her. They revealed a part of her that had become distant with the passage of time. Her collection includes photos of her twenty-first birthday party, a trip she took with her best friend to Cape Town on a ship in the 1960s, her participation in beauty pageants, and studio portraits where she poses either alone or with a friend, performing for the camera. What stories could these photos reveal about life in the Natal Midlands in the 1950s and 1960s? What did they reveal about my mother as a young woman before entering the institution of marriage? What did her performances in these photos conceal about her everyday life and the experiences of women in her family in the afterlife of indentureship? Together we spent many hours engaging this archive - touching, feeling, holding the photographs - as I prodded my mother to remember, to tell me more. The repetition of her stories and the sharpness of her memories, even as she grew older, demonstrated for me that being photographed was important to her. I began to understand that this was her practice of refusing the regimes of violence, regulation and death that marked the quotidian experiences of women within this community. As I became more interested in family photography, I wanted to understand what photographs meant for these colonised subjects and their descendants born into a world defined by racial hierarchies that exacerbated gender inequalities.

The Brown Photo Album is an attempt to make sense of my mother's desire to be photographed against the backdrop of indentureship and the tightening grip of apartheid-era policies. One of the objectives of this project is to engage the 'social life of the photo' by understanding how these photos are both affective and haptic objects that direct us to the importance of feeling photography as a method. To understand the social life of the photograph is to understand the photograph as 'records of choices [and] also as records of intentions'. Black feminist scholar Tina Campt writes that this

Includes the intentions of both sitters and photographers as reflected in their decision to take particular kinds of pictures. It also involves reflecting historically on what those images say about who these individuals aspired to be; how they wanted to be seen; what they sought to represent and articulate through them; and what they attempted or intended to project and portray.1

How do we read the photo-archive of an Indian woman born to parents who were wards of the colonial state? A woman one generation removed from the sugarcane plantations and coal mines where her parents were indentured? What do her photographs reveal about 'the nature of the conditions under which [she] lived'2 and about her labour of imagining freedom in a context where black, brown and blackened women's lives were severely curtailed by the violence of the apartheid state and the heteropatriarchal family? Influenced by my haptic and affective engagement with this archive, this photo-essay heeds Campt's call to 'listen to' rather than 'look at' photographs. To listen to images is to develop an approach that trains us to look 'beyond what we see and attuning our senses to the other affective frequencies through which photographs register'.3 Campt argues that listening is a 'haptic encounter that foregrounds the frequencies of images and how they move, touch, and connect us to the event of the photo'.4 As I developed a practice of listening to my mother's photo archive I recognised that this archive of the everyday was anything but quiet. This archive reveals my mother's 'creative practices of refusal' and her labour of undermining her overdetermined identity as an Indian woman of indenture origin.5 Within vernacular photographic practices, we are able to discern the 'alternative accounts' of marginalised subjects and their uses of photography as an 'everyday strategy of affirmation and a confrontational practice of visibility'.6 As I became more intimate with my mother's photos, I began to understand her desire to be photographed as a practice of refusal that allowed her to step out of the here and now of a present that positioned the Indian as a 'an alien element in the population'.7 Therefore, I approach the family photograph as a 'performative practice' rather than a documentary record.8 This approach directs us to the sitter's investment in accessing the otherwise in a context defined by various overlapping regimes of violence. It is evident to me that my mother's collection of photos attests to her understanding, as the sitter, of the importance of visuality and representation. Stuart Hall reminds us that 'it is only through the way in which we represent and imagine ourselves that we come to know how we are constituted and who we are'.9

This photo-essay contributes to discussions and debates concerning Indianness in South Africa. It draws attention to the making of Indianness in the Natal Midlands rather than in the urban centres of South Africa like Durban, Johannesburg or Cape Town. The Natal Midlands, largely semi-rural, is underexplored in the literature on the Indian experience. Then, in a context where the Indian has been imagined and imaged in very specific ways by colonialism and the apartheid state, this article positions the family photograph as a counter-image to the state's official representations of the Indian. The latter reiterate the narrative of Indian progress and success, which has homogenised the Indian community and conflated the Indian experience with that of the 'passenger Indian', a class of merchants whose experience differs significantly from that of the indentured Indian. These representations, which repeat in the post-apartheid period, have largely obscured the afterlives of indentureship and reduced Indianness to a homogeneous category within the South African imaginary.10 Thus, one of the objectives of this project is to trouble the ways in which South African publics have been historically trained to see and thus know the Indian. By refiguring these photographs as The Brown Photo Album, this article engages and rethinks the entanglement between the visual regimes of colonial modernity and the racialised production of the Indian; the role of indentureship in the production of Indianness that has been obscured because of the conflation of the category 'Indian' with the trope of the passenger Indian class; and the gendered dynamics of diasporic home-making among the Indian community. As an archive of feminist futurity, The Brown Photo Album may open up the thick silences embedded within this South African-specific entanglement.

In order to situate the interventions of The Brown Photo Album as an archive of feminist futurity, I first locate the emergence of this project within the home-space, exploring my haptic and affective engagement with my family archive. I then offer an overview of the ways in which Indianness figures within the visual archives of colonialism and apartheid. I focus specifically on a composite image of identification-type photos of Indian indentured men. I then examine the 1949 state publication Meet the Indian in South Africa before moving on to the interventions by Indian South African academics like Fatima Meer and Uma Dhupelia-Mesthrie and artists like Riason Naidoo, who have used photographs mostly within a documentary tradition to offer new ways to see the Indian against the state's homogeneous representations.11 This section traces the complex ways in which Indian racial subjectivity has been both visually and discursively produced across space and time. By refiguring the portrait photo, I trouble its uses as proof or evidence and hone into its haptic and affective parameters to understand the performance of futurity within my mother's portrait studio photos. This section also turns to oral memories transmitted from my mother to me in order to contextualise her social world in the afterlife of indentureship. This work is influenced by the turn to memory work in the post-apartheid period. As Pumla Gqola writes, 'The project of memory creates new ways of seeing the past and inhabiting the future.'12 The photo-essay ends with a curated collection of my mother's studio photographs and one composite image created from her identification photos.13

Archive, Affect and the Home-Space

The studio photos that constitute The Brown Photo Album are part of a collection of family photos from an extensive archive of material. One collection belonged to my paternal grandparents and remained under my grandfather's care. He lived with us until his death in 1996. His albums contain not only family vernacular and studio photos (the oldest of which is a photo of our early ancestors who were indentured in Natal), but also newspaper clippings of significant events, memorial notices like death notices, reference letters from his days working as a chef at an elite European all-boys preparatory school in the Natal Midlands, my grandparents' wedding card, and his and my grandmother's Indian 'pass' documents, which were issued by the Protector of Indian Immigrants. My grandparents' albums lived in the bedroom I shared with my grandfather. The second collection of photos belonged to my mother. She kept albums in a cupboard under old blankets and curtains - photographs from before my parents married, their wedding album and albums dedicated to each of their three children. She also kept collections of photos in old biscuit tins and envelopes hidden among her jewellery, handbags and other keepsakes. It is unclear when she began to compile her personal photo albums, but they moved with her after she married and travelled with my father across the province from Nottingham Road to Mooi River, Felixton, Estcourt, and eventually Tongaat, where my parents settled permanently in the late 1980s.

Even though these photo-archives lived in our family home and even though my mother had had a long interest in photography, this was not evident in the home-space. I do not remember photographs adorning the walls or resting on furniture. I do not remember any of her studio portraits being visible in the home. I thought that the lack of photos was odd, especially because portrait photos of the dead seemed to occupy a central position in other Indian homes, where they were prominently displayed, exquisitely framed and regularly garlanded with fresh flowers. Often positioned in close proximity to the home's prayer space, these photos seemed to mediate the continuity between the living and the dead, repositioning the photograph in relation to the past, the present and the future. I remember family members honouring/ remembering the dead by offering food, alcohol and cigarettes, which were placed on altars amidst burning lamps and other religious deities that included photographs of deceased loved ones. In our home, we did not have any such photos and altars to the gods and the dead.

Given that my mother had collected such an extensive archive of photos throughout her lifetime, how was I to understand the lack of photographs in our home? Kept entombed within albums, could this be a reflection of the demise of her dreams, desires and aspirations as she became a wife and mother? Was this her own quiet mode of refusal against the heteropatriarchal imperatives that locked her within the home-space, a space characterised as a 'dense zone of sexual/gender/racial regulation'?14

Although family photos were largely invisible within the home-space, I recognised the ways in which they were sites of intense pleasure and displeasure; orientation, disorientation and reorientation. I also attuned myself to how these photographs were touched and felt. I remember relatives tenderly holding photographs in the palms of their hands, tracing the outline of a younger self, a mother or father who had passed on, or a friend lost to the passage of time, but whose presence was affirmed through the photographic image. I was fascinated by the excitement these photo albums generated when family members visited. The albums were an invitation to remember the 'good ol' days' and these memories always intersected with narratives of resilience, resistance and survival.15 The family photograph functioned as evidence; evidence of poverty and proof of everyday struggle and hardship. It was also proof of how much this family had succeeded since those days. The photo album was also an invitation to remember and reimagine. Lives lived on the margins were actively reconstructed and narrated into being. These family albums ignited memories and generated, even though ephemerally, a sense of community and continuity across generations. The family photo album functions as a visual genealogical map, a 'compass, for we seek from it our own historical orientation'.16

This family archive maps out the intersections between 'governmental power and the psychic and emotional lives' of my marginalised family.17 The everyday lived experiences of my family are indexed through identification documents - the Indian pass document, which also functioned as a marriage certificate and a record of the birth and death of children, ID photos and cards - and other objects, including photos. Alongside the imprint of the state, the family photo-archive allows us to access the family's labour of creating a better life as well as their dreams and desires. Their performative practices of self-fashioning, respectability and normativity disrupt the state's figuring of them as temporary, abject and disposable. The album can be read as a site through which the family imagines itself as stable and coherent. For displaced, diasporic and migrant communities, stability and legibility are imagined through the heteronormativity that attaches to essentialist racial/ethnic parameters. The large number of wedding and family portraits in the albums of this precarious community reflect the intense desire for stability and (reproductive) futurity and reveal the labour undertaken to create kin and community against colonial and apartheid-era policies. The family photo album is a generative site to think through the dynamics of migration and settlement within the broader colonial logics of race-making and nationalism. These albums represent the labour undertaken by the indentured and their descendants to create home and 'convey a sense of place' in Natal, a former British colony.18

When the family archive came under my care, my method of touching, feeling and refiguring the collection connected me to my grandparents' and parents' affective and haptic relationship to these materials as they collected, touched, felt and assembled them. The sensual nature of the archive is transmitted across generations and across time and space. I wondered how my desire to refigure the archive intersected with and departed from my parents' and grandparents' desires to assemble it. The affective and haptic nature of family photos/albums and the networks of desires they generate between sitter and photographer, image and viewer, and artist and curator, direct us to the 'other lives' of photographic images.

My affective and haptic relationship to my family archive resulted in an ongoing photographic project titled Queering the Archive: Brown Bodies in Ecstasy, which emerged as a response to the invisibility of brown erotics, desires and pleasures within South African publics.19 The issue of Indian visibility and legibility in South Africa is further compounded by stereotypes and anxieties over the Indian that reproduced the narrative of the Indian as exploitative, alien to the country and an impediment to black African progress. Such discourses obscure the indenture experience and its afterlives. Growing up in the shadows of the sublime beauty of the sugar-cane fields, with the ghosts of indenture all around, my artistic practice is a form of 'disidentification' against homogeneous notions of the Indian that are recycled in South African publics.20

Stereotypes of Indians as exploitative merchants and alien 'others' continue to render them ethnically and culturally un-African. The very category 'Indian', produced within the crucible of imperial power and the apartheid state, was a form of racialisation designed to strategically position the Indian as a buffer population between whites/Europeans and black Africans. These anxieties have a long history in South Africa that can be traced back to the 1860s when indentured workers, imagined as a temporary labour force, were first transported across the Indian Ocean to the British colony of Natal. In subsequent years, the apartheid state also mobilised its propaganda machinery to emphasise Indian progress, reiterating the official positionality of the Indian as exploitative, opportunistic and a threat to both European economic interests and black African self-determination. The processes of racialisation homogenised the Indian, and the different migration streams and experiences, for instance, between indenture labour migration and passenger Indian migration, were largely conflated. The hegemonic narrative of the Indian emphasises a linear and progressive movement away from the unfreedoms of the plantations and mines to a community that has accumulated wealth and prosperity and achieved upward social mobility at the expense of the black African population. Such narratives have largely invisibilised the afterlife of Indian indentureship and the relationship between the production of the Indian and imperial coercive labour regimes of the late nineteenth century.

Given this context, one of the issues that my artistic work grapples with is how to tell a story of African Indianness, deeply embedded within the history and the afterlife of indentureship. Scholar/artist Sharlene Khan captures this complexity in her project When the Moon Waxes Red: 'How to speak and not be a "type," "representative," "indicative," "archetypal"? How to tell a story of an Indian when you are not a Gupta, a Mahatma, a middle-class intellectual?'21 Even though my family, like many others, never acknowledged the traumas of indentureship and its lasting effects on community and kin, it was difficult to escape this history in rural KwaZulu-Natal, where the multiple contours of Indianness become visible. To refigure, according to the Merriam-Webster dictionary, 'is to give new meaning. My project of refiguring is a praxis of disruption invested in queering narratives and archives in order to disrupt the heteronormative structures through which formations of family, community, nation and race/ethnicity become legible. It is an experiment in using the queer Indian positionality to examine the intersections of race, memory, sexuality, archive and affect.22

The Brown Photo Album is part of this larger project of queering the family archive. As I work with my mother's archive, I grapple with what it means to engage this archive as a queer son. Whereas in Queering the Archive I am interested in brown queer desires, The Brown Photo Album is an experiment in accessing the desires of an Indian woman of indenture origin. Futurity shapes the contours of these imbricated projects; in Queering the Archive, by digitally layering family photographs, archival documents and digital photographs, the project mobilises queer erotics to 'open up affective circuits' between the past, present and future, while creating 'lines of relationality between queer bodies of color'.23The Brown Photo Album refigures studio portraits to create a metaphorical album that directs the viewer's gaze to the repetition of performances in order to understand this repetition as a 'grammar of futurity'. To situate this project as an intervention into how the Indian figures within the visual regimes of South Africa, the next section offers a brief overview of the many ways in which the photograph of the Indian has been mobilised since the colonial era and the introduction of the indentured labour force.

Visual Production of the Indian South African: A Brief Survey

One of the earliest photographic images of Indian indentured men, and probably the most circulated in South Africa, is a composite image of a series of classic identification-style photos consisting of 12 men standing in front of a camera and holding their indenture numbers across their bare chests (see Figure 1). The photographs were probably taken in Durban once these men disembarked. As constitutive of the colonial archives, photos such as these would have appeared on identification cards that the indentured workers were required to have in their possession.24 This composite image gives us access to the colonial relationship between indentured workers and the disciplinary regimes of British colonial India which were designed to police the native populations.25 The photograph was one technique of control mobilised by the colonial authorities to criminalise itinerant and vagrant groups that troubled British sensibilities of a proper social order. Criminalisation of such groups was part of a larger imperial imperative of settling, categorising and stabilising the Indian population. Radikha Singh writes that 'the process of categorization reconstructed caste and community with more rigid demarcations.26 Through such practices of categorisation, the excess populations of Indian society were rendered hypervisible. By the 1840s there was a significant shift to directing these excess populations into serving the economic needs of the empire. As the need for Indian labour grew, this population had to be governed and controlled. The techniques of governance used to police, categorise and surveille the larger population were used to manage the importation of indentured labourers to overseas colonial territories. By this time, the slippage between the indentured worker and the convict was well established. Such colonial archives utilised the identification photograph so that publics, described as 'too gullible or tolerant', 'would know them for what they "really" were'.27

This composite image reveals how indentured workers were subject to the uneven power of the colonial gaze. It emphasises the body as a site of difference and deviance. The men are rendered 'passive' through the colonial gaze, reiterating the earliest descriptions of the indentured as 'men with "bare scraggy bones" and children with "tiny and fragile" bodies'.28 The photos emphasise their emaciated bodies: protruding rib cages, taught and tense faces, the clear signs of muscle deterioration in their arms and necks, and their hollow and haunting eyes. On arrival in Natal, these men were inserted into already well-established racial and social hierarchies within the colony. The centrality of visuality to the 'workings of colonial modernity and its afterlives' has been well documented.29 In relation to nineteenth-century Southern Africa, early photographic technologies were intimately related to 'the history of exploration, colonization, knowledge production, and captivity'.30 According to historian Goolam Vahed, Indian indentured men did not fit neatly into the black-white or indigenous-settler binary formations and found themselves in a liminal position.31 This positionality was exacerbated by the restrictions on their movements, the exploitation of their bodies and labour, their exile from natal families and communities, contamination of caste structures, and the corruption of the family, placing any claim to normative gender and sexual regimes in crisis.

This composite image is the only image that survives of these photographs. Historians in South Africa have been unable to locate the originals.32 However, this image has been repositioned by South African Indian artists and scholars to take on new significance and meaning. In the book Inside Indian Indenture, the authors humanise these abject colonial subjects by naming them, thus disrupting the ways in which colonial photography objectified, depersonalised and dehumanised colonial populations.33 Artist and curator Riason Naidoo writes that 'the figures are replicated like patterned wallpaper, suggesting a continuity, an infinite number of other laborers beyond the borders of the image'.34 In South Africa, the faces of these men have come to represent the hundreds of indentured workers who were transported to Natal and a way to remember and commemorate a coercive labour system, described by Hugh Tinker as a 'new system of slavery.35 Aliyah Khan writes: 'Perhaps the majority of the vast archive of Indian indentureship is made up of numbers: numbers of people, numbered people, numbers of goods, numbers of plantations, numbers of ships and sailors, numbers and numbers of the mind-numbing bureaucratic minutiae of empire.'36 Thus, these men represent the fathers, grandfathers and great-grandfathers who were indentured and whose lives and experiences have been lost or obscured within official archives. However, it is important to note that the other lives of this image reiterate the erasure of women within the indenture system, further obscuring their will and voices.

The composite image of the indentured men appears as the first photographic image in the 1949 publication Meet the Indian in South Africa. This document serves as another site to unpack the apartheid state's official representation of the Indian and its uses of the photograph as proof of its benevolent attitude towards this population. This brochure served as the state's official response to the Asiatic Land Tenure and Representation of Indians Act (1946), which curtailed Indian land ownership in predominantly European areas. The language throughout the brochure offers a glimpse into how the Indian population was perceived by the state. Indians are referred to as 'Orientals' and their buildings are described as of 'Eastern' design; they are described as 'penetrating' European areas, and former indentured workers and their descendants are referred to as 'peasants'. The language emphasises the perception that the Indian is unassimilable into the apartheid state's imaginary of a white country. The brochure sends out a powerful message that positions the problem of racial harmony between Indians and Europeans solely as a result of the Indian not understanding their place and wanting more than they are entitled to.

The brochure emphasises that Indian progress - from indentured workers to property owners - is a result of the state's goodwill. By using family portrait photos, it establishes early on that the apartheid state cares for its subjects, especially the Indian poor and working class. The first three photos after the introduction, a series of family portraits, introduce a pair of grandparents - former indentured workers -and their grandchildren, who are taken care of by the state (the Protector of Indian Immigrants). The next photo is of an Indian woman surrounded by six little children. The caption tells us that this is a 'typical Indian mother', a descendant of indentured workers 'who spread over the coast lands of Natal and multiplied'.37 Through the family portrait photo, the state positions itself as benevolent and the Indian community as irresponsible through their uncontrollable birth rate. Thus, even though the state emphasises Indian progress, the brochure also demonstrates the ways in which the Indian is a problem. Other photos include large houses in European areas purchased by Indians. It positions these in relation to Indian places of worship, mosques, temples, churches and shops. Through the photograph, the state provides evidence that it has allowed for the development of the Indian community, their culture and traditions, within clearly defined spaces. Indian encroachment onto European-only spaces renders the Indian ungrateful, opportunistic and a problem.

The last image, a full-page family portrait photo of a nuclear Indian family, emphasises the notion of progress and development. The father wears formal pants and a jacket, holding a basket with one hand and a toddler with his other. The mother wears a sari and holds a baby and a purse. This family outing could have been a leisurely trip to the city or a shopping trip. It emphasises the linear narrative of progress from indentured labour to socially mobile and fully modernised and urbanised Indian subjects. The brochure ends with the following sentence: 'Seldom, if ever, has a people advanced so far in so short a time, from such depths of want, illiteracy, physical and spiritual degradation, to such heights of plenty, liberty and opportunity.'38Meet the Indian in South Africa and other publications like it39 offer a glimpse into '"official" portrayals of the Indian ... through the explicit use of photography'.40 Designed mostly for international audiences, these publications are evidence of the apartheid state's investment in propaganda to counter its 'negative media coverage' abroad.41 Indian progress became the official hegemonic narrative of the apartheid state. However, this official narrative threatened European economic interests and European 'social respectability', pitting Indian and black African communities against each other.42Thus, the Indian became a scapegoat to deflect attention away from the rising white supremacist nationalism taking hold of the country.

Pushing back against the apartheid government's representations of Indian progress, a number of Indian South African scholars have engaged photographic archives in order to disrupt official representations of the Indian. The earliest publication by sociologist and anti-apartheid activist Fatima Meer, titled Portrait of Indian South Africans (1969), mobilises photographs in a documentary style as evidence and proof of the complexities of Indian South African life, while also emphasising the universality of the human experience.43 Meer recognises that differences among 'individuals, groups, and cultures' are part of the human experience.44 She stresses that even though Indian religious customs and practices may be viewed as alien, Indians are like other people in 'their faith in the supernatural, in their regard for the institution of marriage and family, in their desire for wealth and power, in their hopes and fears and in their anxieties and aspirations.45 Her choice of photographs offers glimpses into the intimacies of everyday Indian life, from plantations to informal settlements and middle-class suburbs. Through the photograph she offers a structural critique of the apartheid state's policies that exacerbated cultural, racial/ethnic, linguistic and religious differences to justify separate development.

This important scholarly work has continued in the period after 1994. I want to draw attention to two books: From Canefields to Freedom (2000) and the exhibition catalogue The Indian in Drum in the 1950s (2008).46 The former, written and compiled by the historian Dhupelia-Mesthrie, is a pictorial history of the Indian South African from the beginnings of the indenture system to the democratic period. This book begins with the question, 'South Africans: Full Stop?' and attempts to tease out the many ways in which Indians identify in the post-apartheid period.47 It speaks to the tension between national (South African) identity and Indianness. Further clues to this contentious question are raised by Kader Asmal in the book's Foreword, in which he asserts that Indian South Africans 'are, first and foremost, South Africans.48 The photographs are curated into four sections: Indentured Workers, Free Indians and Traders; Private and Public Lives; Gandhi and After; From the Family Album. The book uses the photographic image to stake a claim to the new South African nation based on 'pacts, solidarity, and collaboration among those who suffered common oppression, been fellow marchers with the liberation forces to a new, just and democratic order'.49The Indian in Drum emerged out of Naidoo's search for evidence of the vibrant Indian community in Durban. This shapes his desire to locate visual evidence of a community he had heard so much about. Within the pages of Drum magazine, Naidoo discovers articles and photos that challenged '"official" and stereotypical depictions of the "Indian" that have been left unchallenged for so long'.50 Naidoo's catalogue is organised around the following sections: Gangland; Living Below the Bread Line; The Politics of Sport; Defying the Color Bar; The Modern Indian Woman; and Writers and Photographers. By focusing on the 1950s, Naidoo positions this photographic archive against the tightening grip of repressive apartheid state policies. The optimism captured in the photos was abruptly curtailed with the 1960 Sharpeville massacre that ushered in a period characterised by the 'brutal enforcement of racist legislation [that] was to epitomise the next thirty years'.51 Naidoo also highlights the works of Indian photographers like G.R. Naidoo and Ranjith Kally who, between the 1950s and 1970s, documented the changes taking place in the Indian community in Durban.

The publications by Meer, Dhupelia-Mesthrie and Naidoo focus on the textures of Indianness in Durban. Unlike Meer's use of the photographic image to claim a universal human condition as an affront to apartheid, Dhupelia-Mesthrie and Naidoo are more concerned with the relationship between the Indian and the new nation. These interventions remain within the documentary tradition and while they offer more complex representations of Indian South Africans, they struggle to unhinge the Indian from a normative imaginary that reinscribes the limits of race, gender, sexuality and nation. The Brown Photo Album is in conversation with these projects but shifts in its attempt to unhinge the family photo from its documentary impulses. Here, the photograph does not stand in as a form of proof or evidence. I am interested in the archive as an aesthetic site of reimagination and reconstitution.

In a context where official stereotypes of the Indian continue to permeate South African publics, I use the term 'brown' as a disidentification strategy. Brownness disrupts the category 'Indian' as it has been produced through colonialism and apartheid-era race policies, which continue to position the Indian as foreign and alien to South Africa. Brownness is a site of reorientation; it directs us to other modes of being, other histories and experiences, and other sensorial regimes, like the haptic and affect, that can trouble the visual regimes of colonial modernity that have structured and continue to structure the way in which the Indian is known to South African publics.

Look at Me ... The Brown Photo Album

In a context where the will of women - particularly black and brown women - remains largely obscured and absent within official archives, it becomes important to develop frameworks that give us access to the complex lives of these 'shadow subjects'.52 Thus, The Brown Photo Album refigures the archive in order to emphasise the performative nature of my mother's studio portraits. My method 'calls out for critical imaginings or alternative visions that suggest moments in which agency could reside'.53 The act of being photographed is a deeply embodied experience and I direct our gaze to my mother's performances as a form of embodied knowledge. I am interested in what her performances transmit across time and space. Her performances represent moments of freedom and ecstasy - deliberate acts of refusal - in a context where, as an Indian woman of indenture descent, she understood intuitively the precariousness of her life and the lives of women within her family and community. I recognise that her photos were 'not separate from the political worlds' that defined my parents' lives and that they offer a 'kind of footprint left in the sand, a trace of where the government once has been'.54 This trace is evident in her performances of futurity as an everyday practice of refusal and reconstitution. By reading her performances as a 'grammar of futurity', the other lives of these images become legible. The Brown Photo Album gives us access to the ways in which the sitter actively constructed an image of herself; this is an image of how she would have 'liked to be seen', directing us to her labour of 'self-creation' and her desire to be seen as a practice of refusal.55

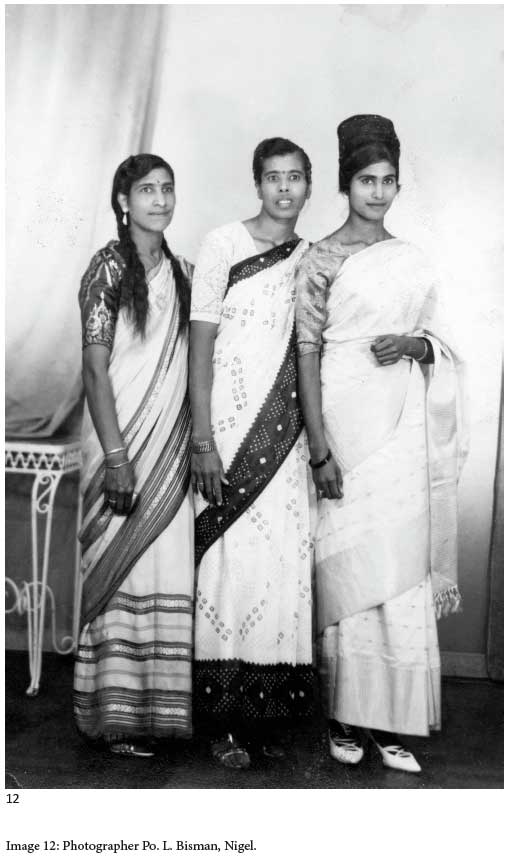

My mother's photos fascinated me because they revealed so much about her as a woman whose life's trajectory was overdetermined and curtailed because of her positionality as 'Indian' under apartheid. In these portrait photos, she wears both traditional Indian clothing and modern western clothing. She wears make-up - lipstick, black eyeliner and foundation - and she styles her hair in the beehive up-style aesthetic, indicative, for me, of the ways in which she embodied a global aesthetic of beauty. She smiles, gazing directly into the camera or slightly out of frame, appearing relaxed, playful and flirtatious. Her attention to style is explicit in the range of hairstyles - from the photo of her long hair cascading down her back to her neatly tucked up-style to the unruly hair of her identification photo when she was in her early twenties. She was also photographed with her best friend, with whom she lost contact when she married. It is evident that being photographed was a site of immense pleasure for her and these photos capture her desire to want to be seen, to be rendered visible against the apartheid state's regulation and surveillance of black and brown women. Her attention to style and aesthetics positions beauty as a method.56Saidiya Hartman writes, 'Beauty is not a luxury, rather it is a way of creating possibility in the space of enclosure, a radical act of subsistence.'57 Self-fashioning can be read as a form of resistance and refusal. Her attention to style and to the aesthetic of selfhood directs us to her 'quiet but resonant claims to personhood and subjectivity in the face of dispossession'.58 I now understand her performances as small, intimate and quotidian acts of refusal against the various overlapping regimes that rendered her, as an Indian woman, an 'impossible' subject.59

The experiences of women under indentureship are well documented. For some scholars, the indenture system offered women the opportunity to escape the rigid caste system and changing social environment in India. However, scholars like Miriam Pirbhai write that, 'The material conditions of indenture (lower wages for women) as well as the inescapable fact of gender disparity . immediately put these women in a vulnerable position, which left them open to sexual assault, concubinage, prostitution, and even uxoricide.'60 Furthermore, it is well documented that conditions on plantations in Natal were so severe that they led to one of the highest levels of suicide among indentured workers within this global system of coerced labour. Meer also writes about the sexual assault of indentured women onboard ships, their ill-treatment on plantations, women giving birth while working, and dying because of improper medical care. While the books by Meer, Dhupelia-Mesthrie and Naidoo give us access to the horrors of indentureship and its afterlives, The Brown Photo Album does something different. I am interested in how the studio portrait offers us glimpses of the labour of creating liveable lives in a context where 'the history of colonial indenture labor meets Indian patriarchy meets South African racism'.61 I am interested in how the repetition of my mother's stories resonates with the repetition of her performances of futurity in the photographs. In order to understand the impossible subject position of my mother, and others like her, I turned to oral histories and narratives. I began to understand my mother's photos as an archive of futurity when positioned against the stories of gendered violence within her family and community.

As my mother grew older, she became bolder about the ways in which she narrated her experiences of growing up in an extended family and of married life. She spoke about the women in her family with an urgency that suggested she intuitively understood her limited life expectations and trajectory from a young age; but within this context, she was determined to create a liveable life, recognising that the pain and violence of the everyday existed alongside moments of pleasure and ecstasy which are evident in her photographs. As my mother and I engaged her photo-archive - as we touched and felt the photos together - she transmitted to me her embodied experiences. She repeated a number of stories that gave me access to her memories. I understood this as an alternative form of knowledge about the afterlife of indenture-ship. Even though my mother was only about seven years old at the time, she vividly remembered the tragic death of her oldest sister, who died from untreated meningitis at the age of 29. Her sister was married to an older man who had children from a first wife, who had passed away. This man treated her sister like a servant; she had borne seven children by the time she was 29 and also worked in a garden planting and harvesting vegetables that they sold to the local community to support their family. After the birth of her seventh child, she was forced to return to the fields. She developed meningitis but her husband refused to take her to a medical doctor. My mother said he also refused to allow her to return to her father's house so that they could seek out proper medical treatment. My mother remembers the night her sister died. Her mother and older brother were indoors taking care of her, trying to get her fever to break. Even though she was delirious, she recognised that she was going to die and blamed her parents for forcing her into marrying an older man who viewed her and treated her as property; her husband's refusal to relinquish control over her life led to her untimely death. My mother remembers her sister telling her parents in Tamil that she was going to die because of them. She died that night.

She also talked about her oldest brother's wife who attempted suicide by setting her sari alight in the bathroom of their home. This incident occurred when my mother was in her mid-teens. She remembers visiting her sister-in-law - a woman for whom she had a lot of respect - in hospital as she lay dying, her body covered in burns. She talked about this family's poverty and everyday struggle for food and other basic necessities. She also did not shy away from the fact that her brother was abusive towards his wife. Her sister-in-law died in hospital leaving behind five young children, one only nine months old. My mother also talked about how she was in charge of taking care of these children even though she was only in middle school. As my mother grew older, she talked more openly about her limited options as an Indian woman. She spoke about her own unfulfilled dreams and desires; she wanted to enrol in the police force and also thought about becoming a flight attendant, but these options were not available to her. Instead, she resigned herself to fulfilling the normative role of wife, mother and grandmother.

It is against stories such as these that I approach my mother's archive of studio photos. These oral narratives - subject to the complex processes of remembering - draw out the relationship between the violence of indentureship and how it determined both 'gendered and raced identities' that would otherwise remain forgotten.62When I prodded my mother into revealing why she was so invested in being photographed, all she said was that she did not know and that when she was paid at the end of the month she visited the photo studio. She simply liked being photographed. Against these spectacular stories of everyday violence, I understand her studio photos as deliberate performances of futurity. Campt argues that 'a grammar of futurity' is a 'performance of a future that hasn't yet happened but must ... It is the power to imagine beyond current fact and to envision that which is not, but must be. It's a politics . that involves living the future now . as striving for the future you want to see, right now, in the present'.63 The affective and haptic frequencies generated by this archive of images point to my mother's desire for the otherwise; the performances of futurity can be read as lines of escape, quiet and creative practices of refusal away from the overlapping regimes of the apartheid state and the heteropatriarchal family structure. Her imaginings of freedom direct us to her active pursuits of the otherwise. These photos suggest that for my mother and other brown and black women like her, violence and precariousness stitch together the past, the present and the future. Her performances can be understood as the desire for a 'futurity realized in the present'.64In a context where the future could never be guaranteed, through photography my mother was negotiating and creating 'new possibilities for living lives that refused a regulatory regime from which [she] could not be removed'.65 These photos reflect her desire to live and imagine a future in the present, a future-present, as an everyday practice of creating and performing freedom, thus positioning this as an archive of feminist futurity. I read her performances of pleasure and desire as a form of embodied knowledge through which she enacts a 'new political vocabulary' that disrupts the colonial/apartheid state's imaginary of the racialised other.66 Honing in to the other frequencies through which photographs register, directs us to the other lives of photographic archives, particularly those that are usually considered mundane and irrelevant to broader historical, cultural and social concerns. By refiguring these photos into this metaphoric album, we are able to understand this imaging practice as a pursuit of 'freedom dreams' from the very grounding through which my mother found herself marginalised and dispossessed.67

The Brown Photo Album consists of portrait photos that were first exhibited as part of my Queering the Archive project at the Michaelis Galleries in Cape Town in 2018. In that version of the exhibition, I juxtaposed portrait photos from my family albums with the visual assemblages that constitute Queering the Archive. My intention was not only to pay homage to the men and women represented in the photos from the family album, but to also trace their desires and pleasures in being photographed onto my desire to explore brown erotics in a context where they remain largely absent. This iteration of The Brown Photo Album includes 13 studio portrait photos, three vernacular photos and one composite image titled 16854\117331, created from two of my mother's identification photos; one was taken when she was in her early twenties and the other when she was in her forties. This composite image echoes that of the indentured workers. If the composite image of the indentured workers represents the faces of the many fathers, grandfathers and great-grandfathers who were indentured in Natal, I offer this image as a representation of the forgotten dreams, desires and pleasures of the many black, brown and blackened women whose will and autonomy have been obscured and remain largely illegible within official archives. Against this backdrop - the official visual production of the Indian South African, the erasure of the afterlife of indentureship and the heteropatriarchal nature of the Indian family, exacerbated by the racial violence of the colonial and apartheid states - I invite you, the reader, to engage these images not just as evidence that this woman lived and shaped South African society but also to get a glimpse of her desires and dreams in a context where she was not supposed to have any. The portrait photos appear as they would in a photo album, without captions, descriptions or analysis, because I do not want to overdetermine their meaning or prescribe how they should be read. As a work in progress, I present this as an experiment, an iteration of a project, a praxis of refiguring family photos in order to understand what this archive can reveal about our past, presents and futures.

Velliammah Ellapen (née Moodley)

[from artist's mother's photo albums], ca. late 1950s to late 1960s.

* I would like to express my gratitude to Sharlene Khan for sourcing primary material for this article from the William Cullen Library at Wits University, Nzingha Kendal for providing comments on the photo-essay, and Jed Kuhn for reading and editing various drafts of the essay. I would like to offer my sincere thanks to the two anonymous peer reviewers, whose comments and suggestions helped shape the article. Finally, I would like to thank Patricia Hayes, Iona Gilburt and the editorial and production team for believing in the value of this project and for their guidance throughout this process.

1 T.M. Campt, Image Matters: Archive, Photography, and the African Diaspora in Europe (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2012), 6. [ Links ]

2 L. Wexler, 'The State of the Album', Photography and Culture, 10, 2, 2017, 100. [ Links ]

3 T.M. Campt, Listening to Images (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2017), 9. [ Links ]

4 Ibid.

5 Ibid., 32.

6 Ibid., 7.

7 D.F. Malan quoted in U. Dhupelia-Mesthrie, From Canefields to Freedom: A Chronicle of Indian South African Life (Cape Town: Kwela Books, 2000), 15.

8 T. Campt, 'Family Matters: Diaspora, Difference and the Visual Archive', Social Text, 27, 1, 2009, 83-114. [ Links ]

9 S. Hall, 'What Is This "Black" in Black Popular Culture?' Social Text, 20, 1-2, 1993, 111. [ Links ]

10 T.B. Hansen, Melancholia of Freedom: Social Life in an Indian Township in South Africa (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2012). [ Links ]

11 Meet the Indian in South Africa: A Pictorial Survey (Pretoria: State Information Office, 1949); F. Meer, Portrait of Indian South Africans (Durban: Avon House, 1969); Dhupelia-Mesthrie, From Canefields to Freedom; R. Naidoo, The Indian in Drum Magazine in the 1950s (Cape Town: Bell-Roberts Publishing, 2008).

12 P.D. Gqola, What Is Slavery to Me? Postcolonial/Slave Memory in Post-Apartheid South Africa (Johannesburg: Wits University Press, 2010), 10.

13 The Brown Photo Album intertextually references Santu Mofokeng's project The Black Photo Album, which is a metaphoric album constructed from disparate portrait studio photos of black Africans from 1890 to 1950. Mofokeng's album focuses on working-class and middle-class subjects and probes into the 'gaze' in order to understand the intention of the sitters and their desires to be photographed during this time period. His album emphasises the performative nature of family photography and self-fashioning and the imagination as a site of reconstitution in the context of ever-increasing colonial policies in Southern Africa. See, The Black Photo Album/Look at Me: 1890-1950 (Göttingen: Steidl, 2013).

14 G. Gopinath, Unruly Visions: The Aesthetic Practice of Queer Diaspora (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2018), 9.

15 J. Mistry, 'A Creative Overview: Race, Memory, Imagination, in J.A. Ellapen and J. Mistry (eds), 'We Remember Differently': Race, Memory, Imagination (Pretoria: Unisa Press, 2012), 49.

16 P. Nair, 'The Family Photo: Inventing Time, Place, and Memory', PIX, Personal Paradigms issue, 2020, 28.

17 M.A. White, Archives of Intimacy and Trauma: Queer Migration Documents as Technologies of Affect', Radical History, 120, 2014, 77.

18 D. Dewan, T. Phu and J.A. Ellapen, 'Movement and the Making of Home: Family Photographs through a Transnational Lens, PIX, Personal Paradigms issue, 2020, 5.

19 See H. Ebrahim, 'Bittersweet: The Aesthetics of Intolerance and Intimacy, in cane/cain [DVD]: Supplemental Booklet (San Diego: Artless Media, 2017).

20 J.E. Munoz, Disidentifications: Queer of Color and the Performance of Politics (Minneapolis and London: University of Minnesota Press, 1999).

21 Quoted in J.A. Ellapen, 'When the Moon Waxes Red: Afro-Asian Intimacies and the Aesthetics of Indenture, Small Axe, 53, 2017, 104.

22 For more information on the project Queering the Archive, please see, J.A. Ellapen, 'Queering the Archive: Brown Bodies in Ecstasy: Visual Assemblages, and the Pleasures of Transgressive Erotics', Scholar and Feminist Online, 14, 3, 2018. http://sfonline.barnard.edu/feminist-and-queer-afro-asian-formations/queering-the-archive-brown-bodies-in-ecstasy-visual-assemblages-and-the-pleasures-of-transgressive-erotics/

23 A. Wahab, '(Re)tracing Queerness: Archiving Indentureship's "Coolie Homo/Erotic'", Visual Studies, 34, 4, 2019, 389; and A. Wahab, 'Indentureships Ghostworld: Re-Imagining the Coolie Archive', Visual Ethnography, 7, 1, 2018, 152.

24 See M. Carter, Servants, Sirdars, and Settlers: Indians in Mauritius, 1834-1874 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995) for a detailed analysis of the uses of such photos in Mauritius.

25 See C. Anderson, 'Convicts and Coolies: Rethinking Indentured Labor in the Nineteenth Century', Slavery and Abolition, 30,1, 2009, 93-109.

26 R. Singh, 'Settle, Mobilize, Verify: Identification Practices in Colonial India', Studies in History, 16, 2, 2000, 154.

27 Ibid., 162.

28 Naidoo, The Indian in Drum, 14.

29 Gopinath, Unruly Visions, 7. See also C. Pinney, 'The Parallel Histories of Photography and Anthropology', in E. Edwards (ed), Anthropology and Photography, 1860-1920 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1994) on the relationship between anthropology and photography and also P. Landau and D. Kaspin's edited collection Images and Empires: Visuality in Colonial and Postcolonial Africa (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002).

30 P. Hayes, 'Power, Secrecy, Proximity: A Short History of South Africa Photography, Kronos: Southern African Histories, 33, 2007, 141. [ Links ]

31 G. Vahed, 'Indentured Masculinity in Colonial Natal, 1860-1910', in L. Ouzgane and R. Morell (eds), African Masculinities: Men in Africa from the Late Nineteenth Century to the Present (Scottsville: Palgrave MacMillan and University of KwaZulu-Natal Press, 2005), 241-42.

32 I would like to thank one of the reviewers for drawing my attention to this.

33 A. Desai and G. Vahed, Inside Indian Indenture: A South African Story, 1860-1914 (Cape Town: HSRC Press, 2010).

34 Naidoo, The Indian in Drum, 12.

35 H. Tinker, A New System of Slavery: The Export of Indian Labour Overseas, 1830-1920 (London: Oxford University Press, 1974). [ Links ]

36 A. Khan, 'Voyages across Indenture: From Ship Sisters to Mannish Women', GLQ, 22, 2, 2016, 252.

37 Meet the Indian in South Africa, 6.

38 Ibid., 64.

39 For instance, see the 1975 publication The Indian South African (Pretoria: Department of Information).

40 Naidoo, The Indian in Drum, 12.

41 Ibid.

42 See Hansen, Melancholia of Freedom, 28.

43 Meer, Portrait.

44 Ibid., 5.

45 Ibid.

46 Dhupelia-Mesthrie, From Canefields to Freedom; Naidoo, The Indian in Drum.

47 Dhupelia-Mesthrie, From Canefields to Freedom, 9.

48 Ibid., 5.

49 Ibid.

50 Riason Naidoo, 'Restoring the Indian Experience', Mail & Guardian, 21 September 2008, http://mg.co.za/article/2008-09-21-restoring-the-indian-experience (accessed 10 April 2015).

51 Naidoo, The Indian in Drum, 8.

52 E.H. Brown and T. Phu, 'Introduction', in E.H. Brown and T. Phu (eds), Feeling Photography (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2014), 3.

53 H. Bhana-Young, Illegible Will: Coercive Spectacles of Labor in South Africa and the Diaspora (Durham: Duke University Press, 2017), 4.

54 Wexler, 'The State of the Album', 100.

55 Campt, 'Family Matters', 90.

56 C. Sharpe, 'Beauty Is a Method', e-flux journal #105, December 2019, https://www.e-flux.com/journal/105/303916/beauty-is-a-method/ (accessed 20 October 2020).

57 Quoted in ibid.

58 Campt, Listening to Images, 65.

59 G. Gopinath, Impossible Desires: Queer Diasporas and South Asian Public Cultures (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2005). [ Links ]

60 M. Pirbhai, Mythologies of Migration, Vocabularies of Indenture: Novels of the South Asian Diaspora in Africa, the Caribbean, and Asia Pacific (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2009), 8. [ Links ]

61 See When the Moon Waxes Red (2016) by Sharlene Khan. Her project deals with the gendered effects of indentureship's afterlife on women in her family and community.

62 Gqola, What Is Slavery to Me? 10.

63 Campt, Listening to Images, 17.

64 Ibid.

65 Ibid., 33.

66 Xavier Livermon's study on the political potential of 'Kwaito bodies' in post-apartheid South Africa as enacting a new political vocabulary informs my reading of the performances in these photos. See X. Livermon, Kwaito Bodies: Remastering Space and Subjectivity in Post-Apartheid South Africa (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2020).

67 K. Macharia, 'Toward Freedom, The New Inquiry, 6 March 2016, https://thenewinquiry.com/blog/toward-freedom/ (accessed 20 October 2020).