Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Kronos

versão On-line ISSN 2309-9585

versão impressa ISSN 0259-0190

Kronos vol.45 no.1 Cape Town Nov. 2019

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2309-9585/2019/v45a7

PHOTO ESSAY

Angola 1992 – Hope in the Face of Anguish

Paul Weinberg

Centre for South African Art and Visual Culture, University of Johannesburg

If we want to turn Africa into a new Europe and America into a new Europe, then let us leave the destiny of our countries to Europeans. They will know how to do it better than the most gifted among us. But if we want humanity to advance a step farther, if we want to bring it up to a different level than that which Europe has shown it, then we must invent and we must make discoveries...For Europe, for ourselves and for humanity, comrades, we must work out new concepts, and try to set afoot a new man. (Franz Fanon)1

So, by the end of the thirty years war for southern African liberation it was clear that we, in the region and beyond, had won a significant victory. And yet it was also a pyrrhic one: difficult, in short, to know whether to cheer or to cry.. (John Saul)2

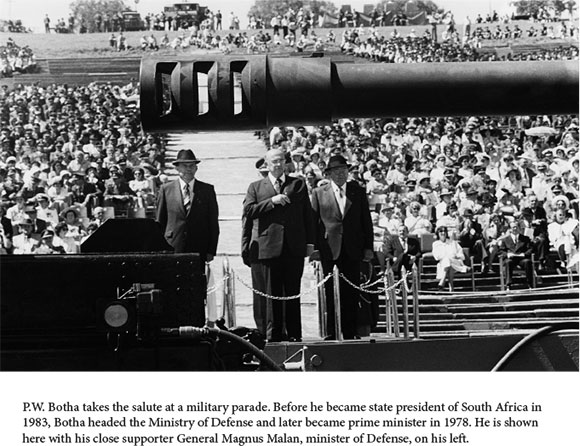

In 1980 I photographed P. W. Botha, then President of South Africa taking a salute during a military parade at the hallowed shrine of white supremacy, the Voortrekker Monument. It was a symbol of the times and went on to be used numerously by the alternate press and anti-apartheid movements within and outside the country. I was not on any assignment, but my own. Six years earlier, I had been conscripted as a young white South African at the age of seventeen years and two months into the South African Infantry. I spent my last three months of that year on the Namibian/ Angolan border. But I was lucky. I was fortunate to see no action, but at the same time, deeply aware of how us young conscriptees had been coerced to do the dirty work and be the cannon fodder for apartheid's war in southern Africa, and integrally part of its war machine internally. A year later, 1975, with the demise of the Portuguese government, its control of its former colonies and the rise to power of the liberation forces within them, I would have been part of the invasion into Angola, an invasion that turned the tide on southern African politics. P. W. Botha, not long before he became President, initiated in 1979, as Minister of Defense, what he saw as the 'Total Onslaught'. His rationale was loud and clear as he drummed up a war psychosis, 'The resolution of the conflict in the times in which we now live demands inter-dependent and co-coordinated action in all fields: military, psychological, economic, political, sociological, technological, diplomatic, ideological, cultural, etcetera. We are today involved in a war whether we like it or not. It is therefore essential that a total national strategy (is) formulated at the highest level.' More popularly understood as 'Swart en Rooi Gevaar' (Black and Red Peril), they were short-cut references to the apartheid government's determination to cling onto white minority rule, deny its black inhabitants the right to vote, participate in a democratic process and more pertinently in this context, to declare war on the left and anti-apartheid forces which he and the ruling National Party, conveniently collapsed into 'communist'. Caught in a time of the Cold War, P. W. Botha's strategy had the backing of the CIA, USA and the conservative elements throughout the world. In reality South Africa was a military state, its bordering frontline countries part of a military zone, and I was fighting back with my camera. It was a time of 'us' or 'them', the 'struggle' for liberation and a state of deep polarisation. Militarisation was a personal theme of mine. I became a conscientious objector after my military service and handed in my rifle. I was a war resistor on the inside and a photojournalist on the outside. I travelled to places far and wide as well as the frontline states.

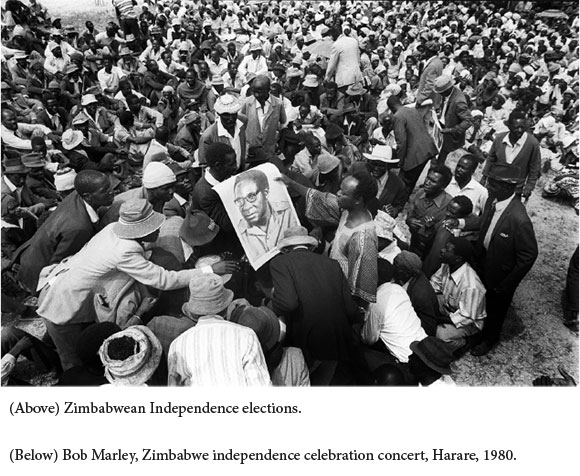

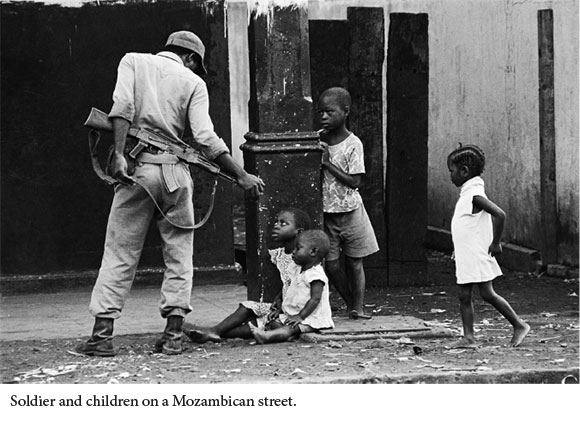

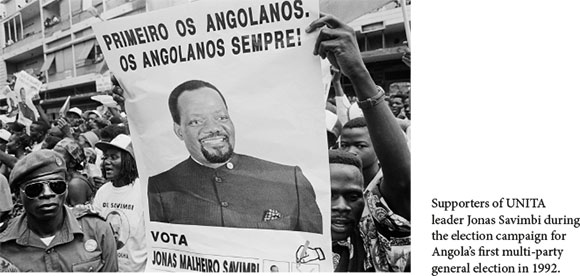

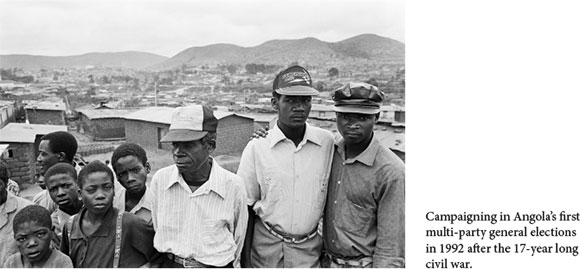

My first commissioned assignment as a young photographer, around the time I had taken the P. W. Botha photograph, was to cover the first free and fair independent elections in Zimbabwe in 1980. I brought back images of freedom fighters from ZANLA and ZIPRA in uniform, clasping AK 47's, the Zimbabwean people voting, their celebration from colonial rule, as well as the legendary Bob Marley in concert. Over the next decade or so I travelled back to Zimbabwe on a few occasions and visited other frontline states. I witnessed on a number of trips how people battled to survive in Mozambique, a country ravaged and impoverished by civil war. I returned to the border of Namibia several times with my camera to share stories of atrocities and heartache at the hands of the South African military and police, as well as courageous resistance and finally independence and peace in 1989. In 1992, I was assigned by Der Spiegel to cover Angola's first elections. Angola was very difficult to access. Most journalists and photographers from South Africa told the story from the perspective of UNITA and the South African Defense Force.

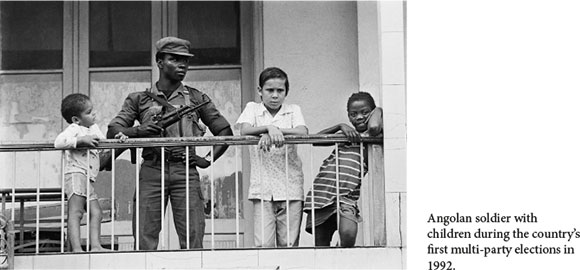

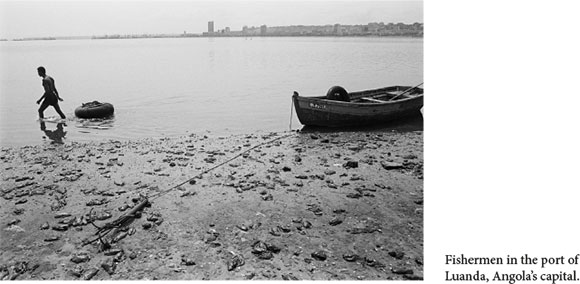

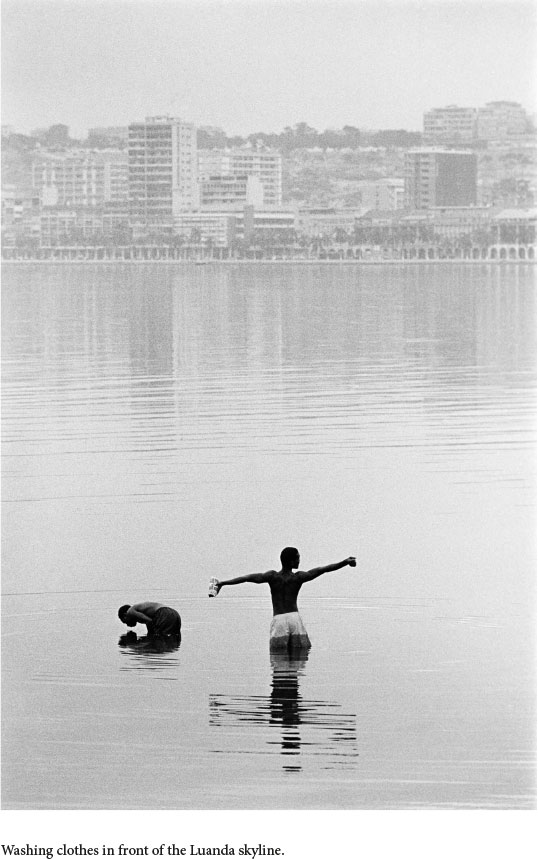

My distinct first impressions of Luanda then, was of a city traumatised by war. It was disturbing how people would defecate in front of you, wash in potholes in the road where water had gathered after rains and how everyone seemed in constant search of basic survival needs. I remember while eating lunch at a café restaurant, a naked woman screaming in the street in a delirious state of despair. It was clearly a city desperate for peace and shaken to the core by the devastation of a protracted civil war.

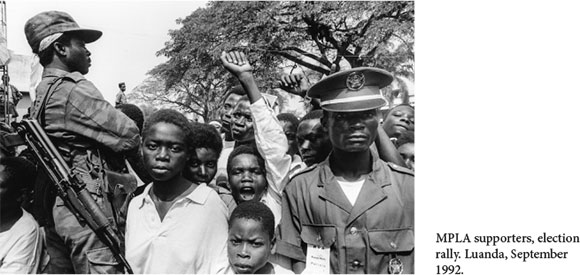

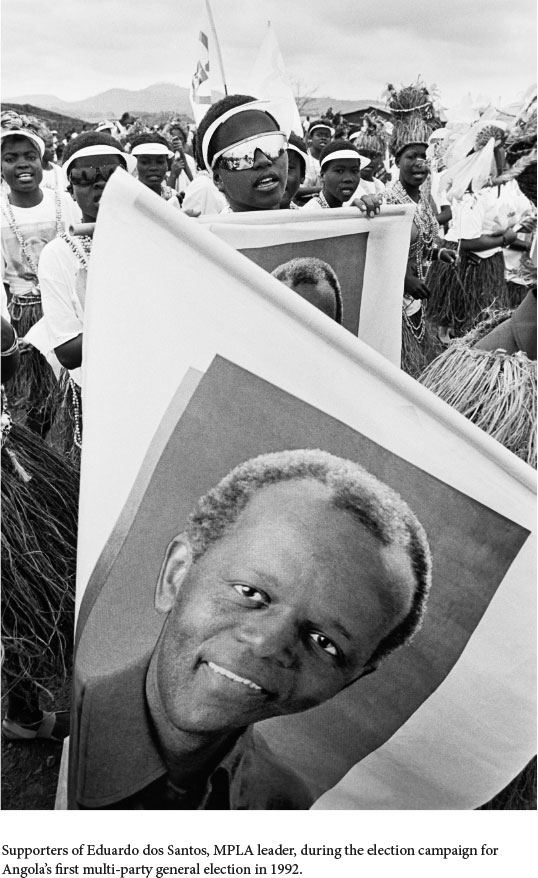

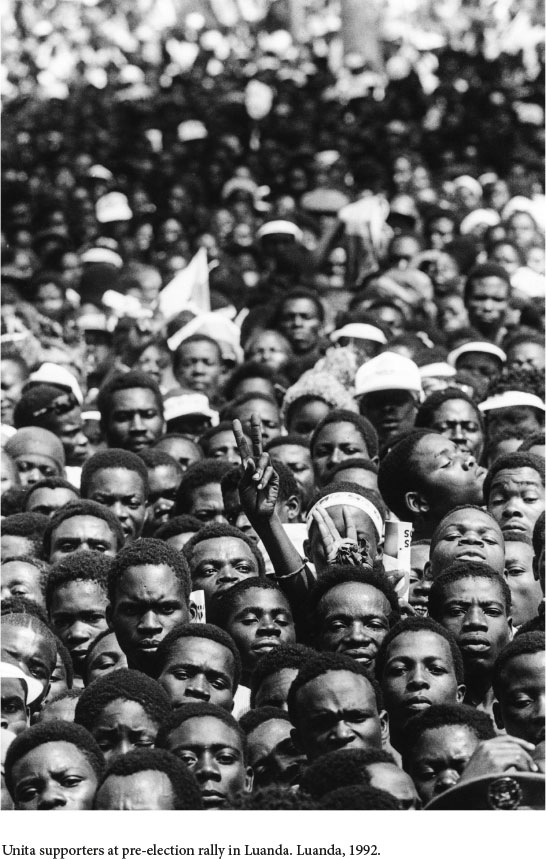

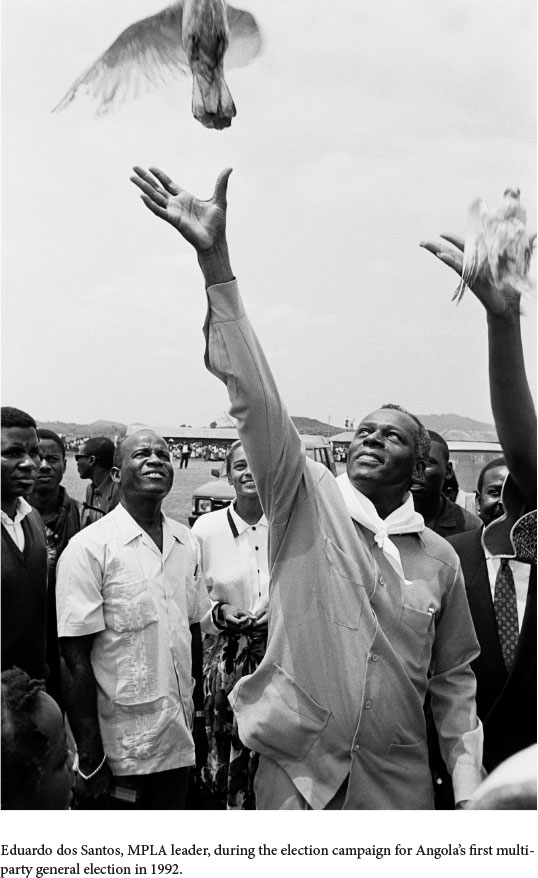

I photographed UNITA's Jonas Savimbi in Luanda at a rally, watched cautiously by gun wielding security, address a crowd of his supporters who had gathered. Savimbi's presence in the city was a rare visit for him and he waved to the small, cheering crowd in a hostile environment. The MPLA were more in abundance as bands with flags portraying large photographs of Jose Eduardo Dos Santos marched in the streets. In Kwanza Norte, Dos Santos released doves into the air in a gesture of peace and goodwill. Politicians we interviewed at the time, often quoted the old African adage, that when two elephants fight the grass suffers. The elephants being a metaphor for the MPLA and UNITA, and grass for the people on the ground.

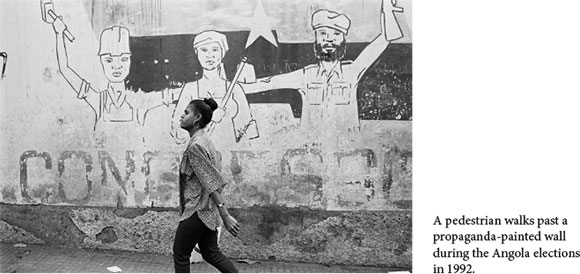

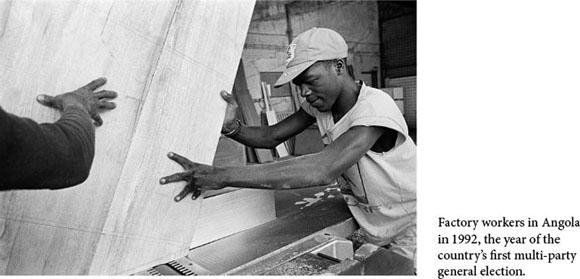

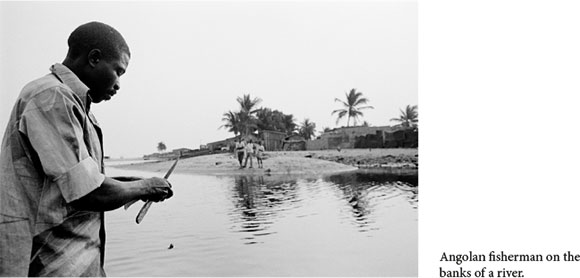

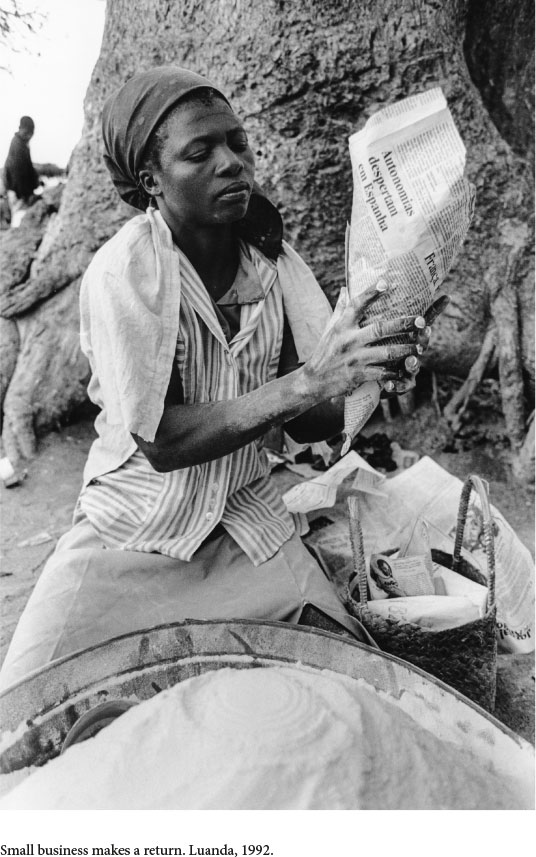

Between political events, I photographed the city. Fishermen fishing in the harbour, semblances of a return to some small-scale industry, and hawkers plying their goods on the streets. The signs of a glamourous past had long lost their sheen. The city had fallen into decay. Old faded billboards echoed this and unpainted buildings reflected a new but austere post-colonial functional architecture. On the other side of the harbour people came to the beach for ice creams on a Sunday, to relax and hang out at more up-market eating places. The large number of four by fours signified the richer classes' division from the poor who travelled everywhere by foot, bicycle or taxi. Luanda, although relatively safe and unscathed by the war, was itself a refugee city for the hundreds of thousands who had fled war-torn areas throughout the country. It was a city bursting at the seams, as a result, unsustainable and clearly struggling to cope with a hopelessly inadequate infrastructure and strained resources.

If ever there was a city crying out for peace and a political solution, it was Luanda in 1992. A palpable tension pervaded the city. Hope and anguish were etched on people's faces. The gestures of the politicians and the hopes for democracy, however, were short lived. Soon after the elections, Savimbi, not satisfied with the election result, returned to the bush and Angola endured another gruelling decade of civil war. The grass of Angola was to suffer again. The article that appeared in Der Spiegel ran a few photographs and I never thought these images from this non-moment in history would resurface. A few years ago, I scanned the 'best of' Angola for the record, my archive and for history. But somehow photography always surprises me - images resurface and come back to life in ways you never expected.

Those moments, nearly three decades ago, reflected promises of a better country, a continent and the world. Franz Fanon would have been disappointed as the African humanity he had hoped for in the opening quote were deferred, yet again. John Saul's stifled enthusiasm that the thirty years' war in southern Africa was a pyrrhic victory, are telling. The war may be over now in Angola since the death of Savimbi in 2002, but the challenges for all Angolans to genuinely benefit from a secure country once so avowedly socialist, remain. While a semblance of peace has returned and much progress has been made in de-mining the war-ridden country and bringing it back to state of normalcy, the scars like so many post-liberation states, have been laid bare. Just like these images and my memories of Luanda in 1992....

1 F. Fanon, The Wretched of the Earth (Harmondsworth, U.K.: Penguin 1967). [ Links ]

2 J. S. Saul, 'Life in a Struggle that Continues!', Review of African Political Economy, 23 November 2015, http://roape.net/2015/11/23/life-in-a-struggle-that-continues/. [ Links ]