Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Kronos

versão On-line ISSN 2309-9585

versão impressa ISSN 0259-0190

Kronos vol.45 no.1 Cape Town Nov. 2019

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2309-9585/2019/v45a4

ARTICLES

Fighting over the Archive: Politics and Practice of the Art World in Angola

Suzana Sousa

ISCTE-UL https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4922-8028

If the ambivalent figure of the nation is a problem of its transitional history, its conceptual indeterminacy, its wavering between vocabularies, then what effect does it have in narratives and discourses that signify a sense of 'nationness': the Heimlich pleasures of the heart, the unheimlich terror of the space or race of the Other; the comfort of social belonging, the hidden injuries of class; the customs of taste, the powers of political affiliation; the sense of social order, the sensibility of sexuality; the blindness of bureaucracy, the strait insight of institutions; the quality of justice, the common sense of injustice; the langue of the law and the parole of the people.1

Introduction

'Culture strengthens the nation, more culture more Angola', one can read at the bottom of every document issued by the Angolan ministry of culture. The slogan enunciates the general program of the ministry: to strengthen Angolan culture as a nation-building tool. It also mimics the MPLA's 2012 slogans which read: 'MPLA - More Democracy, More Development'. As the ruling party since 1975, the MPLA (Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola) manages history and memory as political weapons, and culture and the arts are caught in the construction of 'angolanness' that results from that effort. Since 2002, the official political discourse focuses on peace and reconstruction2 emphasising the role of the government in rebuilding the country after civil war. However, not much has changed since the 1970s as regards cultural policy and infrastructures.

The context of art production in Angola is still marked by the recent political history of the country and by the ideal of nation building that reflects its fractured cultural tissue after more than three decades of war. We can find a clear construction of a canon of a shared cultural memory put in place to reinforce such ideals. However, the reproductive space of the margins makes visible the cracks as well as alternative constructions of the nation. In this paper, I use the term 'archive' as it was framed by Aleida Assmann, as elements that are part of cultural memory but are marginal3 -traces, things and stories not part of a celebrated national narrative but nonetheless part of it. By looking at the current art production in Luanda, and focusing specifically on the Fuckin'Globo exhibition project and the National Union of Visual Artists, I argue that there is a generational conflict in the local art world supported by a distinct view and engagement with the ideal of nation. In this regard, the National Union of Visual Artists (UNAP) is the gatekeeper of a political view of the arts that produced the existing nationalist construction of the arts, while Fuckin'Globo challenges such nationalist constructions by claiming spaces for critical views of both the nation and art.

Angolan Art and Politics in Context

In his first speech for independent Angola, Agostinho Neto addressed themes such as the social class structure inherited from the colonial system and the diversity of cultures within Angola's territory. Both subjects were essential for the MPLA's version of national history and its highest echelons who approached issues of race and ethnicity inside the party4 as causes of conflict. This emphasis on diversity was replaced with the um só povo, uma só nação' (one people, one nation) narrative of the MPLA, thereby highlighting a geographical perspective on the country5 encouraged a homogeneity in the Angolan territory. Issues of difference were therefore largely removed from the public discourse. Other silencing strategies were also in place such as the political appropriation of memory, the association of national identity with certain aesthetics (mostly Cokwe or Bakongo) and the construction of a national art that made visible national identity. These processes are currently still in place through a cultural policy that underlines the role of culture as the link between angolandide (Angolaness) and nation as well as its role in peace consolidation, national sovereignty and social cohesion. This can be seen, for exemple, in the recent debates regarding national holidays and the ongoing discussion between the three historical parties concerning dates for the celebration of the Liberation War. Only in 2019 did the MPLA accept 15 March as a national holiday in what was also considered a recognition of the FNLA's participation on the war against colonialism. As history was co-opted by political discourse so a fixed version of culture became a piller in the nation's construction of itself. 45 years of independence has been insufficient for the country to have such ideas contested inside of the party political landscape, though culture has been a creative ground for it whether in music with kuduro or in the new global engagement with the arts.

Angolan politics is particularly shaped by what Chabal designates as 'Revolutionary nationalism'6, which led to the socialist state after independence. Regarding cultural policy, one can find the same revolutionary stance associated with both nationalism and a search for a national aesthetics. Culture was a space for refiguring the nation with clear ties to MPLA party politics. Cultural policy resulted mostly from the party president Agostinho Neto's speeches exposing the link between the state and the party and its influence in all social spheres.

Until the 1990s, most official visual arts production took place inside UNAP, which was created as a political artists' association affiliated to the MPLA in 1977. It is important to note that the same happened for music and literature, the latter organisation led by Agostinho Neto himself. This resulted in a process of politicising culture and cultural history that left traces up until today. UNAP's 1985 legal statute underlined its connection to state structures as well as its goal to 'fomentar a vinculação das actividades da União Nacional de Artistas Plásticos ao processo revolucionário angolano e à luta pela construção do socialismo'7(promote the linking of the National Union of Visual Artists' activities to the Angolan revolutionary process and the struggle for the construction of socialism).

As a political organisation, UNAP set out to pursue a national aesthetics based in an Angolan visual culture that promoted themes inspired by 'tradition', however it also created forms of exclusion due to its political ideology. One of the founding fathers of the organisation, Vitor Teixeira (Viteix), elaborates on the revolutionary role of arts in the Angolan context in his PhD thesis8 where he articulates this pursuit as a political struggle. UNAP established, in a sense, a national taste by including some artists and excluding others. It promoted the presence of Angolan artists in a circuit of international arts that included CICIBA Biennial (the itinerant international biennial of bantu art), Cuba (Havana Biennial) and several Eastern European and African countries, mainly through official national delegations taking part in events such as Festac 77 or simply representing the country in state meetings. It is worth underlining that UNAP acted as a state institution regarding visual arts and crafts and lost its relevance with the end of the socialist period, as the state reinforced its own structures and began to separate cultural policy from the ruling party. This political process took place as Angolan artists started to participate in the global art world through events as the Venice Biennial in 2007 and the series of events that were part of the movement created by the Luanda Triennial that started in Luanda as early as 2003, though before that Angolan artists participated in the 1995 Johannesburg Biennial and the São Paulo Biennial. This moment was crucial for UNAP as the organisation was forced to change its statute as a consequence of the changes in the state apparatus.

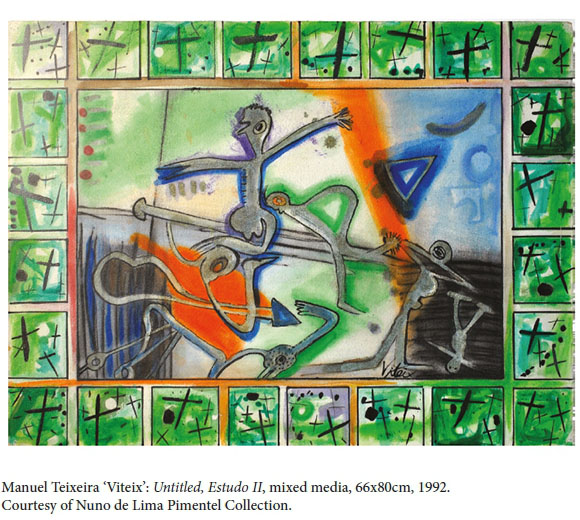

According to Delinda Collier, Angolan 'art was at the time of independence in 1975 produced in a state of emergency, shaped by a response to epistemological and physical violence. This art in fact took advantage of the crisis of signification in Angola and sought to reinstate that feedback loop interrupted by Portuguese anthropology. Thus, nationalist artists used Cokwe symbols, including those derived from sona, as visual symbols of "Angola"'.9 In his work Viteix used Cokwe symbology, influencing several younger artists. Shaped by the studies of José Redinha, he studied several Angolan cultures but his work focused mainly on Cokwe elements, used mostly in the form of frames as we can see in the images.10 Viteix simplified the lines and forms of sona drawings and removed them from context. In itself, the gesture unfolds the uses of traditional Angolan culture as a sign of a shared culture in an effort to erase regional differences and as a way to support the MPLA's construction of a hegemonic nation.

Today, cultural policy and the official political discourse on culture alternate between the trope of 'return' as a longing for tradition, for a moment when culture was pure and uncorrupted from external influences, and the 'New Man', which, as a metaphor, goes from being the socialist man from the single party version of MPLA to the development of culture industries according to the 2011 cultural policy.

The concept of 'return, not new in the context of anti-colonial conflict, in Angola was celebrated in Agostinho Neto's poem Havemos de Voltar. The poet promises to return to the land of ancestors, to tradition, to a free Angola, one not marked by colonialism. To return also suggests a possibility of the erasure of colonial marks as if tradition and the land itself could regenerate and erase that violent memory. The 'New Man'11 on the other hand, is a socialist marxist trope, adopted in the national anthem. The New Man was to be achieved through work, a homage to the proletariat. Fast forward to 2011, Presidential Decree 15/11 of 11 January, approves Angolan cultural policy. In this seminal document one can still see the trope of 'return' now through the discourse of promoting Angolanidade and tradition and the need to be aware of the risks of globalisation. At the same time, globalisation is a space of development, markets and growth. The document is vague in terms of concrete policy but establishes principles that its claims should guide cultural policy such as Angolanidade, tradition and the need to preserve the nation's cultural diversity, national languages and patriotic education.

Following the end of the single party system in Angola, at the end of the 1980s, UNAP as a political organisation became redundant, which led it to change its legal status in 2008. Only then did it removed the link to the MPLA as it was reclassified a 'public utility, thereby gaining it access to annual public funding. The new statute also allowed the organisation to maintain the position of partner to the Ministry of Culture for visual arts issues, although the relevance of this was more evident in practical issues than of legal consequence. However, most of the younger generation of artists, working since the early 2000s, do not relate to the work of the organisation and have been independently engaging with international and/or global languages and art circuits while at the same time engaging differently with traditional Angolan visual culture by dissociating their identities from party politics. This has resulted in a generational conflict that makes claims to a new historical framing of cultural elements as well as new critical and social spaces for artistic debate. The new art scene of Luanda12 characterised by events such as the Luanda Triennial in 2007, the international recognition of several Angolan artists and more recently by a growing art market with galleries and collectors acting globally and participating in art fairs and auctions, it is also marked by 'conflicts and discrepancies between state and popular readings of national history, memory then becomes a political space, where ideas of nationhood, political legitimacy and identity are contested'.13 Here again, there is a dual discourse of an art practice aware and participating in a global discussion of art and a political view of culture that emanates from the government, no longer from the party alone, that maintains its engagement with ideas of legitimacy and identity and of a national construction of arts and culture.

Fuckin'Globo and the new generation

This search for a new political and social meaning for Angolan art is represented in the Fuckin'Globo project. Initiated in 2015 with several subsequent iterations, Fuckin'Globo was started by a group of artists looking for a place to show their work outside of a market driven logic but also freed from language or discursive constraints. They set out to use Hotel Globo, a 1950s colonial hotel in downtown Luanda that has a longstanding connection to the city's arts scene, as a means of engaging with the city space. The hotel was the headquarters for the Luanda Triennial and also housed studio artists due to its low prices and strategic localisation. In Fuckin'Globo, the artists are fully responsible for the costs of the production and most of the art produced is ephemeral and site-specific, resulting in a statement on art and its particular process of creation. These artists are young and most of them have ties to international art circuits. They use the private space of the hotel rooms to showcase their artworks. Their work does not share a single theme but rather each is provided the freedom to decide. The artists, Kiluanji Kia Henda, Edson Chagas, Marcos Kabenda, João Ana, Elepê and Orlando Sérgio, define the project, at the time of its first edition, on their Facebook page as:

The exhibition collective 'Fuckin' Globo' brings together various multidis-ciplinary artists, that will present works in different languages such as performance, photography, sound and installation in the mythic Hotel Globo, an establishment with an unconstestable presence in the cultural life of Luanda's downtown. In this exihibition, we intend to develop an approach about the use of the body, image and sound in an era in which dialogue is substituted for the violence of high-tech equipment, and in which the rampant globalisation of conflicts has become a principal factor in cultural contamination and homogenisation.

In 'Fuckin' Globo!', the space will become inseperable from the concept of the works presented, creating an interaction and unison between the various interventions with the aim of representing a universe submerged in a screaming cacophony. In a claustrophic environment, and in the intimacy of the rooms, the works in Hotel Globo aim to function as a metaphor about the nonconformity of those who live in a planet in evident chaos and accelerated mutation. The word and image will be subjected to a process of distortion and manipulation, threatening the limits and definitions of artitistic creation in a specific geographical context.14

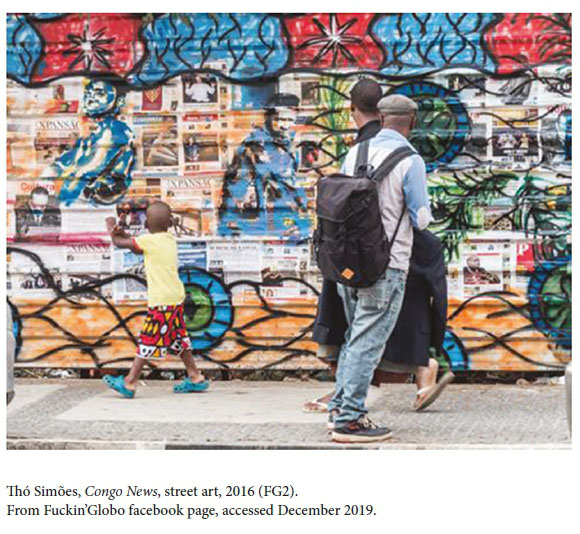

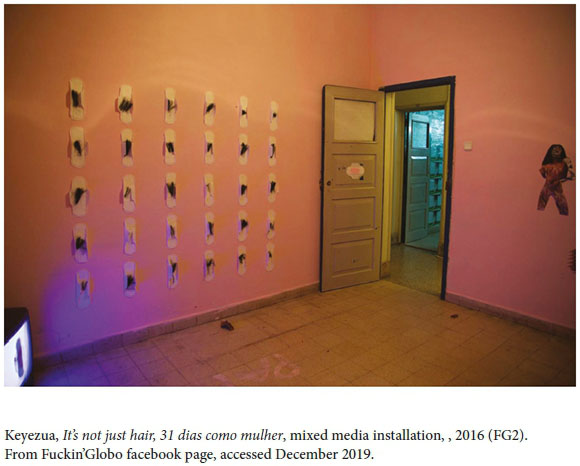

The project has grown with each edition, adding more artists and curators. For the artists this is a space of freedom and learning, with them developing new techniques and languages with more well-established artists. 22 December 2015, was the the first edition of Fuckin'Globo. The event was something like a pop-up show that lasted for only a day, and attacted the city's usual art audience. The second edition had more artists and was held for three days, from 1 to 3 July 2016. The artists were João Ana, Ery Claver, Elepê, Angel Ihosvanny, Lola Keyezua, Kiluanji Kia Henda, Thó Simões, Irina Vasconcelos and Muamby Wassaky. This second edition consolidated the ex-perimentational character of the project and embraced a bigger audience triggered by the impact of the previous edition. Thó Simões created a street art space, Congo News, a mix of collage and graffiti that engaged with the public space. Ihosvanny showed Oscilações (Oscillations), an installation piece that played with the audience's expectations of a room, disrupting it with graffiti in a wall and a television set with a video that resembled the effect of a broken television. In this same edition Keyezua challenged the audience with the installation It's not just hair, 31 days as a female, where she explored the concept of the female body and family in Angolan society. The way she did it was not particularly new in the context of feminist art, however, in the Angolan context, bringing the body to the forefront is quite radical and a clear break with public moralistic discourses on sexuality and the body shared by politics and religion. In a pink room, the work of Keyezua consisted of a wall covered with menstrual pads and fake hair and on the floor the sentence 'All women my dad likes my mom hates'. Most artists dealt to an extent with elements of contemporary Angolan society but characterised it in dystopic terms. A good example of this process was the work of Thó Simões that started in the second edition on the outside wall with Congo News, an outdoor graffiti and collage style journal, and developed in the following edition to a performative work that showed the king and queen of 'Congoland' naked and unable to communicate.

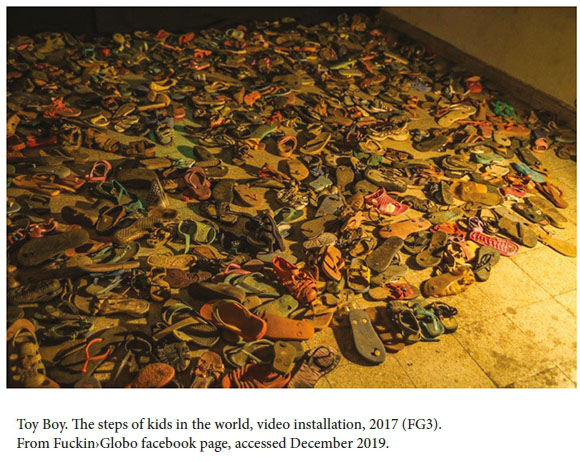

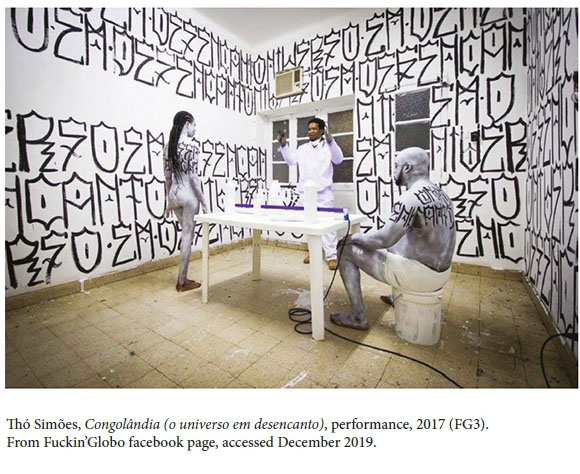

Fucking'Globo III increased the number of artists, this time including João Ana, Ery Claver, Elepê, Lola Keyezua, Kiluanji Kia Henda, Thó Simões, Irina Vasconcelos, Muamby Wassky, Edson Chagas, Toy Boy, Alekssandre Fortunato, the Verkron collective, Gretel Marin and Daniela Vieitas. These were mostly emergent artists, which consolidated the project as also a learning and mentoring platform. Between 26 and 30 January 2017, the tight corridors of Hotel Globo were crowded and the exercise of going to the bedrooms and looking for the artists almost mimicked Luanda's typical traffic jams. Kiluanji Kia Henda and Orlando Sergio's piece showed a performance and installation work in Room 109 The Grave of the Unknown Zungueira addressing a recent event at the time, the killing of a zungueira15while trying to escape a city enforcer. The artwork consisted of an installation piece that recreated the goods carried by female street vendors in Luanda and a performance by Orlando Sérgio reciting Angolan poetry which referenced the zungueira as an iconic figure of the city. The observer was immersed in the red light of the room, the smell of mangoes and fire from candles burning; the plastic boxes became a gravestone to the unknown zungueira. The Untitled installation of Toy Boy did not allow the audience to enter the room - it was only possible to peek from the door. The numerous thoroughly used small-sized shoes gained a disturbing character when put all together and on top of each other, referencing the slippers known in Luanda by sambapito, which are widely available and are sold for very cheap prices, but also to the growing number of kids in the streets. With Congolândia - The Disenchanted Universe, Thó Simões continued the Congoland dystopia, this time with a silent King and Queen that commanded their subjects through an interpreter. The performative piece engaged with popular ideas in Luanda about the Congo as a space lacking governance and rule which added a critical layer to the silent king and his use of an interpreter regarding current national politics where the lack of communication between the president and the population was a common discussion on the local press. Although not planned as such, Fuckin'Globo became a space for social and political critique, a space where art could engage openly with public issues outside of the common tropes of Angolan society. Struggling for a space for thinking and freedom these artists define a conflict in the Angolan art world between the post-independence artists, most of them supporters of nationalist and politicised discourse of Angolan art, connected to UNAP, and a post-war generation of artists. The occupation of the old colonial hotel and the embrace of Luanda's decadent downtown seemed also to be a reaction to the lack of cultural infrastructure in the city. This critique was accentuated by the ephemerality of the artworks, interrogating the relationship of the artist with the art market, but also museological concepts such as the conservation and preservation of artworks or rather, the lack of museums in Luanda. In a city where historically the artist also took the role of producer, curator and dealer of his own work as a way to address the absence of artistic infrastructures, becoming the victim of such processes, this critique is also aimed at the artist himself as it interrogates his role as a main player in the field.

Kiluanji Kia Henda is one of those responsible for maintaining Fuckin'Globo as an influential artist from his generation with international recognition but also a permanent presence among local artists and in general in the Luanda art scene through his mentorship of younger artists, art projects and his work with a local gallery. In his particular work, Kiluanji Kia Henda revisits several historical themes ranging from the Cold War to urban space as a legacy of colonialism so as to look at the appropriation of space by everyday Angolans. He usually explores a historical base from which he elaborates new or alternative narratives. The process can take us to a utopian projection such as in Icarus 13,16 one of his most well-known and iconic works. But most of the time one can find a foundation in the present that provides a quality of inter-temporality very specific to his work. That is the case in the series Redefining the Power, where the artist photographed old colonial plinths, though stripped of their statues, that still exist in Luanda. In Redefining the Power III (from Series 75 with Miguel Prince), the artist even recuperated an old colonial postcard where one can see the plinth, the statue and Portuguese military troops. In this series, something common in Kia Henda's work, the city and its transformation are not only the background but a reflection of time and political change. A similar exercise is found in the film Concrete Affection Zopo Lady, where the city is a step-stone to reflect on the end of colonialism and the present, mainly through architecture and its decadence in Luanda. The gesture is again repeated in the series commissioned by the Sharjah Art Foundation, where the starting point are the sona drawings. Contrary to Viteix, the use of sona drawings leads Kia Henda into a design exploration that results in a physical structure. The sense of identity that arises throughout his work comes from the research and awareness of a national history and narrative at the same time as there is the freedom to perform a panoramic photography as if to allow memory to act as a bridge between a 'lived past and the imagined future',17 something that underlines the difference between Viteix and Kia Henda's approach. While the first was adopting a notion of 'return' disguised in revolutionary nationalistic terms, Kia Henda is attempting a new narrative that incorporates contemporary Angola reality and popular culture.

Rethinking art and politics in Angola

Since independence Agostinho Neto's speeches have been used as an orientation guide to Angola's cultural policies. The speech on national culture of 8 January 1979 is still celebrated as a national holiday dedicated to national culture. In this speech, given to an audience of writers of the National Writers Union, the former president questioned Angolan culture and addressed the need to differentiate it from the influences of the Portuguese culture, more noticeable among the assimilated population of the country's urban areas. In it, he dismissed the dependency of one on the other. Read in relation to his other speeches and writings, it points to an idea that there is an Angolan culture that needs to be rescued and promoted in the process of building a new Angolan nation, thereby reinforcing the 'return' ideal. This was also the period that demanded the erasure of colonial statuary and the adoption of new street names throughout the country. In Luanda, some of the statues were destroyed, others were kept hidden and today most can be found in the National Military History Museum. This is a very synthetic description for what was a violently politicised and policed process in culture which resulted in the creation of what were considered by the existing power, or the State, as national symbols. This process was supported and promoted by artists, writers and intellectuals of the MPLA. In the current moment, the socialist ideology of MPLA exists only in the party doctrinary documents and in residual control practices such as the maintenance of cultural organisations' political ties. As a consequence, UNAP acts as the gatekeeper of tradition and Angolanidade in the Angolan visual arts, accusing artists that do not abide to its rules of having been corrupted by globalisation. This is the background scenario for an arts scene that has became more and more international. In addition to the incipient local arts market that in the last three years have seen Angolan galleries show work abroad and participate in international art fairs, artists are reaching international recognition on their own through international biennials and commissions.

The recent market growth is another characteristic of a generational divide. Due to the lack of public funding, the market had to grow internationally and adopt international standards. Again, UNAP and most of its artist members stay ashore and the national identity discourse can only deepen that. The younger generation of artists, here represented by Fuckin'Globo and Kiluanji Kia Henda, seem to be better prepared for this open market and engage in a more fluid manner with concepts such as identity and tradition. While Viteix recuperated traditional Angolan symbols as a revolutionary gesture, these younger artists seem to be aware of how recent politics has framed their lives and ways to access the world. That does not mean a disconnect or a denial of tradition, but raises new questions about which tradition they choose to adopt and the role of politics in that context. Most of the works in Fuckin'Globo deal with critical and political matters. However, the project in itself is political in the sense that it addresses issues such as visual arts audiences, cultural spaces and infrastructures. For instance, by transforming the space of the hotel into a museum, even if for a few days, it inevitablely considers questions of display and preservation that, by being ephemeral, deal with it implicitly. Today the discourse on the nation and national identity, though still used by the state, results only in a control strategy more noticeable in moments such as political celebrations or the continuous political propaganda of the ruling party. The dynamic art world on the other hand is adopting its own strategies to deal with history and the past. Importantly, artists' current production is finding new spaces for discussion and thought as well as new markets. UNAP, in its close relation with the state, is missing the opportunity to assume a role as a professional artists organisation to support artists' rights in a way that reflects the current political moment in Angola where ideologies are no longer relevant but maintain a grip in reality.

Conclusion

The current political discourse in Angola concerning culture maintains a focus on the strengthening of endogenous Angolan culture. The loss of cultural values is a common motto, often used by politicians. The concepts of 'return' and of the 'New Man' have marked the boundaries of the political view regarding culture in Angola, defining a space for culture and the arts between a political tool to instill nationhood and the programatic space of tradition. In the connection between culture and politics, contrary to music, particularly urban music in Luanda,18 that took an active part in spreading nationalistic ideas during the liberation fight, visual arts were kept in a hiatus of tradition and popular art. The years after independence saw artists paint political murals such as the one at the military hospital in Luanda with socialist slogans and voicing the political ideas of the moment, as well as acting as the griots of a tradition defined by colonial researchers. The national culture discourse sounds emptied and translates into a moralising discourse, while the marks of the cultural struggle are to be seen in the erasure of colonial statues and street names. The struggle seems to be particularly alive in the cultural field where institutions, such as UNAP, try to keep themselves relevant and manage to do so with the support of the state. At the same time, a new dynamic arts field is growing and challenging the constraints of national identity.

The generational conflict that we have described in the arts makes transparent the cracked tissue of post-war Angolan society, evidencing memory as a central issue in the narration of the nation with the contemporary arts scene claiming a role in this discussion. An exemple of this is the way the Luanda Triennial adopted a discourse on the nation in several of its projects.19 Despite these differences, however, the space between UNAP and Fuckin'Globo is one of creative discussion and not necessarily of extreme positions. In these dynamics the roles of the artist and of the State are clearly in the discussion, both looking back but also engaging with future possibilities. In contrast, the global context in which the local art world of Luanda takes part establishes new boundaries and standards for both artists and governments in terms of policy and outcomes.

1 H. K. Bhabha, 'Introduction: Narrating the Nation' in H. K. Bhabha (ed), Nation and Narration (London: Routledge, 1990), 2. [ Links ]

2 J. Schubert, '2002, Year Zero: History as Anti-Politics in the "New Angola'", Journal of Southern African Studies, 41, 4, 2015, 1-18, doi: 10.1080/03057070.2015.1055548. (accessed 24 June 2017). [ Links ]

3 For more on this: A. Assmann, 'Canon and Archive' in A. Erll and A. Nünning (eds), A Companion to Cultural Memory Studies (Berlin:de Gruyter, 2010), 97-108. [ Links ]

4 F. R. C. Reis, Das Políticas de Classificação às Classificações Políticas (1950-1996). A Configuração do Campo Político Angolano: Contributo para o Estudo das Relações Raciais em Angola (Lisboa: ISCTE-IUL, 2010), <http://hdl.handle.net/10071/3265> (accessed 24 June 2017). [ Links ]

5 'De Cabinda ao Cunene e do Mar ao Leste' (From Cabinda to Cunene and from the Ocean to the East) was one of the main political mottos of MPLA emphasising the territory and its people's connection with the party.

6 P. Chabal, A History of Postcolonial Lusophone Africa (Indianopolis: Indiana University Press, 2002), 25. [ Links ]

7 Executive Decree 6/85 of 19 January, Angolan Republic Diary.

8 V. Teixeira, 'Pratique et Theorie des Arts Plastiques Angolaises (de la Tradition à une Nouvelle Expression)', (Unpublished dissertation, University Paris VIII - Saint Denis, 1983).

9 D. Collier, Art in a State of Emergency: Figuring Angolan Nationalism, 1953-2007' (Phd dissertation, Emory University, 2010), 141.

10 Detailed list of images at the end.

11 For more on this concept see D. Collier, 'A "New Man" for Africa?: Some Particularities of the Marxist Homem Novo within Angolan Cultural Policy' in J. E. P. Mooney and F. Lanza (eds), De-centering Cold War History: Local and Global Change (London and New York: Routledge, 2013), 187-207.

12 For more, N. Siegert, 'Luanda Lab - Nostalgia and Utopia in Aesthetic Practice', Critical Interventions, 8, 2, 2014, 176-200, DOI: 10.1080/19301944.2014.939534.

13 Schubert, '2002, Year Zero', 1-18.

14 In https://www.facebook.com/events/790834467687794/?acontext=%7B%22ref%22%3A%22106%22 %2C%22action_history%22%3A%22null%22%7D (Accessed 23 May 2017).

15 Female street vendor.

16 For images and details on the artwork see https://www.calvertjournal.com/features/show/5312/red-africa-icarus-13-africa-journey-sun-space-mission.

17 L. Plate and A. Smelik, Performing Memory in Art and Popular Culture (London: Routledge, 2013), 3. [ Links ]

18 For more information on this see M. Moorman, Intonations: a Social History of Music and Nation in Luanda, Angola, from 1945 to Recent Times, New African Histories Series (Ohio: Ohio University Press, 2008). [ Links ]

19 For more on this issue see Collier, 'Art in a State of Emergency'; and N. Siegert, 'The Archive as Construction Site: Collective Memory and Trauma in Contemporary Art from Angola', World Art, 6, 1, 2016, 103-123. [ Links ]