Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Kronos

On-line version ISSN 2309-9585

Print version ISSN 0259-0190

Kronos vol.45 n.1 Cape Town Nov. 2019

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2309-9585/2019/v45a2

ARTICLES

Monumental Relations: Connecting Memorials and Conversations in Rural and Urban Malanje, Angola

Aharon de Grassi

San José State University. https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4821-0878

ABSTRACT

Angola's staggering oil wealth and histories of conflict and inequality make for tempting binary narratives of power and exploitation, which, however, suffice neither for accuracy nor action. This article uses a relational geographical perspective to go beyond simple binaries by jointly analysing the central 4 February Plaza in the heart of Malanje City, and the proposed new rural memorial for the Baixa de Kassanje revolt located east of the city in Kela Municipality. Drawing on news, ethnography and historical records, I situate the 4 February Plaza in the city's broader history of settler colonialism and point to its current tensions, ironies and practical and political uses in the city's daily geography. The Kassanje memorial is relatively unknown and has languished since a first pilot model village was announced by President Agostinho Neto during a 1979 visit. I discuss plans and media coverage about building a Kassanje village project and a new memorial and monument, as well as constructing new housing and social infrastructure in the area. I also examine claims to reestablish 4 January as a national holiday for martyrs of colonial repression (including in Kassanje) and to provide military pensions to people affected by the Kassanje revolt. Analysis shows how such plans and discussion of the revolt reveal both diverse voices in conversation as well as significant changes in dominant narratives about the revolt. More generally, the Kassanje discussions points to rural geographies of nationalism (and their accompanying monuments), which entail their own specificity as well as connections with urban areas. Similarly, understanding both monuments in their provincial contexts - and likewise their connections with Luanda - can provide new perspectives to work that has focused on Luanda and larger cities.

Introduction

By examining two monuments in relation to one another and other sorts of geographies, this article illustrates how narratives around nationalism and memory in Angola are multiple, partial, contested, contradictory, reworked, co-opted and appropriated in various ways, places and times.* This provides a more precise picture of the dynamics of hegemony by showing how it is not easy for the state to appropriate memories without also opening itself up to counter claims because the state is intervening in complex, multilayered geographies, and hence the outcomes and consequences of such interventions are not entirely predictable or controllable. The analysis can thus be situated in broader discussions of space and power and, more precisely, the fundamentally spatial concept of hegemony, which analyses of Angola have invoked loosely, contradictorily and colloquially, without much regard to the voluminous literature by Antonio Gramsci and subsequent writers.1 To understand the dynamics of hegemony, one has to understand geo-histories, and not simply invoke a natural law that 'for any hegemonic tendency, there are always counter-hegemonic tendencies.2

In brief, the events discussed below include, firstly, a renovated plaza for Malanje city named for the nationalist revolt of 4 February 1961 in Luanda, announced in 2005, again in 2010, and constructed over the next few years. Secondly, a Martyrs of Colonial Repression Day was made a holiday in 1996, in 2010 new plans were announced for a village project and memorial (both in the small village of Teka dya Kinda) commemorating the January 1961 Kassanje revolt covering much of the cotton zone in the eastern lowlands of Malanje province, the Martyr's holiday was demoted in 2011 to a Day of National Celebration, a local monument was built in 2016, the MPLA (Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola) recommitted in 2017 to the new memorial project, and the cemetery was rehabilitated in 2018.

These and other events raise difficult questions about crude notions of untrammelled power: if, as some scholars suggest, the MPLA administration has sought to construct and maintain a 'master narrative' about its exclusive role in national liberation, then why did it promise a major project at the site of this other major anticolonial Kassanje revolt (the primary responsibility for which is almost never attributed to the MPLA), institute an annual national holiday on the day of the Kassanje revolt, and emphasise that revolt consistently over decades and throughout the country? Moreover, actions by the MPLA administration have been seized upon also by various people over past decades, repeatedly emphasising five key claims for Kassanje for: (1) a memorial/monument, (2) completion of the promised pilot village, (3) pensions, (4) restoration of the holiday, and (5) regional infrastructure.3 Such complex leveraging and reworkings are lost in simplistic portraits of unhindered MPLA state elite power, what Pitcher describes as 'a familiar narrative about war, dictators, inequality and the resource curse in Africa'.4

In contrast, Schubert rightly (and diplomatically) looks for more than 'hegemony imposed from above', but he does so by relying on problematic notions of 'copro-duced' hegemony, as well as 'the master narrative' and 'the system' as sorts of deus ex machina.5Schubert attributes the phrase 'master narrative' to Primoric, who more precisely only uses the term 'master fiction', citing Mbembe, who cites Wilentz, who is referring to that phrase used in Geertz's explicitly Weberian chapter from a 1977 tribute to the eccentric Chicago school anticommunist crusader Edward Shils!6 William Roseberry is actually quite critical of Geertz, emphasising 'the major inadequacy of the text as a metaphor for culture' because 'text is written; it is not writing. To see culture as an ensemble of texts or an art form is to remove culture from the process of its creation.'7 Similarly, the emphasis on 'emic/etic' stems from 1950s structural linguistics of the sort that Gramsci - a trained linguist - was critical in his emphasis on fragmentary and contradictory popular 'common sense'.

The utility of the concept of hegemony is how it points to the changing specific ways involving consent and coercion (and compromise) by which shifting contradictory elements are contingently held together - rather than an absence of contradictions and coercion.8 Hegemony, in Gramsci's words, is something 'of force and of consent ... as a dialectical relation.9 Hegemony, Stuart Hall emphasises, is 'a contradictory conjuncture' that 'has to be continually worked on and reconstructed in order to be maintained', and hence the presence of coercion and contradictions does not necessarily mean a lack of hegemony, limits to or 'cracks' in it, or some kind of 'counter-hegemony'.10

This is fundamentally at odds with a Weberian conception of power that naturalises institutional continuity in metaphysical claims about humans' organic 'instinctive habituation' based 'on magic grounds because supernatural evils are feared', which informs some efforts to explain Angola with the claim that '[o]nce established, institutions gain a life of their own and are extremely difficult to bypass'.11

To understand hegemony therefore requires precise study of contradictions in hegemonic discourses, in popular 'common sense' and the actual historical and geographical processes that produce contradictions, which are not limited to some inherent polysemy and ambivalences of 'idioms of race, class and family'.12 To understand these also requires going beyond metaphors of space as a palimpsest. So although, in Roseberry's words, a dominant order may prescribe 'forms for expressing both acceptance and discontent', that does not mean that such forms are clear and stable nor that protest and resistance only take those prescribed forms, and much less that such forms constitute a shared framework for all popular practices and meanings.13

Rather than hegemony/power intrusively projecting outward from an enclave across and upon relatively passive space, instead hegemonic reconstruction projects operate by actively producing space itself because they mobilise popular consent by promising to reconstruct the former infrastructure (itself originally built partly to redress extensive exploitation) that people still vividly remember and tangibly experience everyday through its material rubble. If we misapprehend patterns of infrastructure and conflict, then we cannot appreciate these widespread popular experiences of past integration and its still present remnants, we are less able to recognise how popular consent is mobilised, and more apt to incorrect unidirectional views of hegemony as imposed and/or purchased from the top downwards and centre outwards.

Methods

Analyses of power, nationalism and reconstruction in Angola have been limited by over-generalisations and a focus on Luanda, and not enough on in-depth fieldwork and archival research (let alone analysis informed by understanding of indigenous languages). Astonishingly, there still appear to be no in-depth studies based on long-term residence where the majority of Angolans actually live - namely, outside of the Luanda core and other major cities - except for my own work. Such analytic margin-alisation compounds the historic marginality and impoverishment of the countryside. While hundreds of academic works have mentioned the importance of Kassanje - as one of the most important sources of the slave trade, with a major sociopolitical formation, and hence a key site for African history - almost none have addressed the practices and conditions of people currently living there (aside from diamond-related studies).

Similarly, literature on monuments in Africa focuses on historic figures, especially men, and especially in central locations in capital cities. There are also large relevant geography and African Studies literatures on monuments, including reworking and tensions of past monuments to colonial and oppressive figures (particularly relevant in the wake of the Black Lives Matter movement in the United States), as well as some also on rural dynamics (especially for Zimbabwe and Kenya), and I look forward to making analytic and comparative connections in further work; hence the present article's scope focuses on providing some foundational chronicling for Angola. While this paper does address a central monument in a provincial capital, I am focusing on a city outside the capital city, I am also examining a rural monument, and I am viewing these in relation to one another, as connected, not as isolated separate 'case studies'.

This article draws heavily from the online database of Angola's state news agency, ANGOP. For events since 2000, unless otherwise specified, the source is an ANGOP article for that date. As discussed elsewhere, this source is sometimes cursorily criticised and dismissed, but actually has much valuable information.14 Moreover, ignoring this source simply because of 'state bias' risks denigrating the labour of numerous journalists. One limitation is that it is difficult to tell which of the ANGOP stories were reproduced in actual printed newspaper or aired on the TV or radio. Newspapers and TV have been more limited outside of Luanda, but radio was more accessible, also aired in local languages and carried local stories that often did not make it into national news forums. While I have mostly focused on the state press due to the greater availability of numerous detailed accounts over the years, I have also consulted as much of the 'independent press' as I was able to access. And although I have done in-depth research in Malanje city and province, the account here needs to be complimented -and may change - with information from further fieldwork in the sites discussed.

I try to write in a way that makes clear the uncertainties, gaps, alternative interpretations and conflicting information, rather than present it as an entirely coherent authoritative narrative. A resulting challenge is that the article may get somewhat complicated and confusing, so I beg readers' patience since that is actually part of the point: to show what is lost when analysts prioritise parsimony over precision.

The arguments and material here are shaped by my own experiences. I visited Malanje and the 4 February Plaza various times from 2008 to 2016, I lived near the plaza for several months in 2009 and 2013, and I was frequently in and around the plaza for various activities (shopping, banking, meetings and such) from 2011 through 2012. My 2015 PhD dissertation included a chapter on Kassanje, which became an article that I discussed in Angola in January 2016, and that was eventually published/ uploaded in 2018. The chapter and article analysed a broader set of information and drew on newly found reports, arguing that the revolt had a political character shaped by its socio-spatial interconnections. Prior to this, I had visited the memorial in 2009, purchased in Luanda in 2011 a key book on the revolt, attended a discussion at Keswa in 2012, met briefly with the Association in 2012, and conducted research in Lisbon in 2013 and 2014.

'Cracks' or contradictions?

A simplistic 'pessimist' perspective might read into some Malanje monument issues a binary narrative of a dominant Luanda-based 'creole' MPLA elite that generally looks down on a remote rural populace and seeks to uphold a 'master narrative' about its exclusive role in national liberation. Such a perspective could cite the facts that Kassanje revolt veterans have not been allocated pensions, the holiday was demoted from an official national holiday off from work, and the new memorial itself was not only delayed for many years, but located relatively close to the city (not in the actual lowlands) and planned in a modernist style, with only a small token structure actually ever built (see Figure 1 above). Meanwhile, the government did allocate funds to build the 4 February Plaza in the centre of Malanje city, in an area that was surrounded by elite buildings and businesses, and was formerly named for a colonial official involved in repressing the Kassanje revolt. Again, I have framed this here as a one-sided, pessimist and reductionist interpretation, which will now be complicated.

The 4 February Plaza was not built seamlessly. Firstly, it had delays, with works initially announced in 2005, and then budgeted and re-announced 5 years later in 2010 and completed years thereafter. So the announcement and completion of the plaza were not clearly coordinated as ploys for the 2008 or 2012 elections (the MPLA easily carried Malanje and Kassanje in these elections anyway). In addition, while the plaza was initially planned to have a statue of Angola's first President, Agostinho Neto, this was cancelled. Moreover, the 4 February Plaza was announced as only one part of a broader effort at improving the city, including renovation of several key roundabouts, including statues of the historic leader Queen Njinga Mbandi, and the Black Antelope (Palanca Negra) that is native only to Malanje and is Angola's national symbol. The influence of top-down 'creole' impositions on the periphery is partly contradicted by the fact that these regional and rural Malanje statues were actually implemented in the heart of the city, but the statue of President Neto was not. Neto's own home for a brief time in Malanje meanwhile stands relatively obscure, with a small plaque on an unrenovated building. Moreover, these city plans for the statues were announced at the first meeting of the Social Consultation and Coordination Council, a sort of non-binding consultation forum that was a small step in a longer gradual process of decentralisation.

Moreover, the plaza itself is actually much smaller than the plans for Kassanje that Malanje's Governor first officially announced in 2010. The Kassanje project in contrast appears relatively massive - 30 houses, and a range of other facilities. In fact, it may be that part of the stumbling block with the Kassanje project was its sheer size and complexity, particularly in the face of economic difficulties by 2012 onward. Moreover, such an ambitious project for only one small village with a just few hundred people could potentially make the government susceptible to proliferating claims in other places in the Baixa and elsewhere, not least since the Association claimed to have some 40,000 members (including throughout Angola). One might counter, however, that perhaps these plans were simply a ruse, and were never sincerely intended to be implemented, functioning as a prolonged incentive for political support exactly by ongoing deferral.

The next sections first give further detail on the 4 February and 4 January projects in Malanje as background for the subsequent analysis. The third section uses a mostly chronological narrative about Kassanje and the 4 January holiday, memorial/monument and pensions in order to analyse ongoing spatialised state-society dialectics. The conclusion summarises the main claims and their significance for Angola and broader discussions.

Background, binary interpretations and beyond

The 4 February Plaza

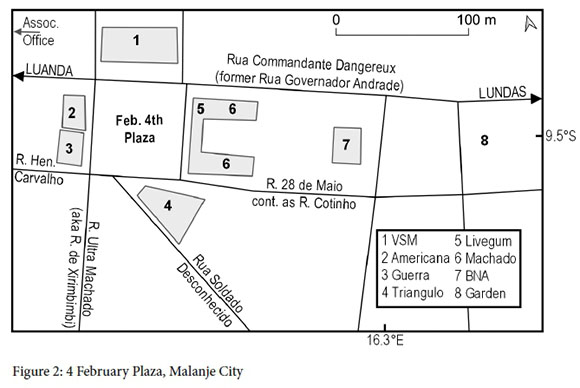

In addition to the above emphasis on complications, this section gives details how 4 February Plaza's residual elite colonial connotations can only be understood in relation to other practical and often countervailing dynamics.

The plaza is located in what is roughly a central area of the city, just after the busy commercial shops leading up from the bridge over the Malanje River and just before the central Malanje gardens, where there is also a regal national bank office. On the east side of the gardens is the imposing large two-storey building housing the MPLA provincial headquarters (formerly the headquarters of Malanje's colonial Chamber of Commerce), which was actually inaugurated by Neto in 1979 during the same visit to inaugurate the Teka project, and to which I will refer at various times in the below discussion.

The plaza consists of a mostly open square, with some garden beds with grass, shrubs and trees, and encircled with cement seating, benches, some wooden trellises, lights, plain coloured flags (red, yellow, and black), a small water pool and some walls with black plaques listing over a hundred names of nationalists that participated in the armed struggle of national liberation, as well as some passages from poems by President Neto.15

The plaza project was first announced in 2005 around the time that the main large 4 February monument was being completed around the site of the original revolt planning meetings in the Cazenga neighbourhood of Luanda (built by China Jiangsu and budgeted at $4 million). The prominent display of the catana (cutlass or machete) as one of the key symbols for the 4 February events indicates the rural in the urban in Luanda (although there are not cutlasses in the Malanje plaza) - but even this large central 4 February monument in Luanda had by 2019 become dilapidated in various ways.

The second announcement of the new Malanje plaza came on 4 February 2010 just at the time of the new Constitution; this timing is important and I will return to it in the next sections. The governor stated that it would cost $1.8 million and entail five months of work. It is not clear how much was actually budgeted and spent; although the 2010 budget allocated funds (170,000,000 Kwanzas, or roughly $1.7 million at that time) for Malanje's Rehabilitation and Requalification of Parks, Squares, Plazas and Small Plazas, these funds also may have been spent on other projects, and funding for the plaza may have also come from elsewhere in the budget. Within a few years the project was complete.

During the colonial period, the Malanje plaza was mostly a parking lot for the cars of white settlers. At some point, perhaps in the late 1960s or 1970s, it was renamed Rebocho Vaz Plaza, after Lieutenant Coronel Camilo Rebocho Vaz, who was an on-the-ground military leader of the repression of the 1961 revolts in the Baixa de Kassanje and northern coffee areas (and then Uije governor there 1961-66), and then the governor of Angola for the key period 1966-72. Already in 1974 during the transition to independence, someone had written to the Malanje newspaper complaining of 'the unjust name of Rebocho Vaz' and urging it to be changed (albeit to Vasco de Gama).16

The following description should be remembered when I subsequently also describe potential indications of the area's importance. While the plaza is more or less in the centre of Malanje city, it is hardly of central importance to the vast majority of the city's residents, neither practically nor symbolically. In many ways it is unremarkable - the plaza does not have a large name or plaque, the actual writing is difficult to read and one could easily pass it on the main thoroughfare without noticing. Some of the plaza's lights have stopped working and it sits across the street from a multi-storey building whose bottom floor has for years leaked water and been used for trash and homeless encampments. The headquarters of the Provincial Government is not here, but rather on the other side of the downtown. While some students may spend time waiting here, and events are occasionally held in the vacant lot across the street, it does not get much use, neither informally nor during formal state celebrations.

Such limitations to the plaza's actual current importance stand in discontinuous contrast to how the colonial toponymy around the plaza illustrates conquest, exploration and exploitation, epitomised in names such as Henriques de Carvalho (an early ethnographic explorer and governor of the neighbouring Lunda Province to the east), Gago Coutinho (an important proponent of using geography for colonisation), and Louro da Gama (president of the colonial agricultural union and municipal council). Even many of these old colonial names, however, have been changed and ignored. The city's main thoroughfare along the historic railroad terminus was previously named after the nineteenth century colonial Governor José Baptista de Andrade (who promoted the construction of the railroad and city), but was renamed after the liberation fighter Paulo da Silva Mungungu (Comandante Dangereux), who was killed during the 27 May 1977 events; the renaming is perhaps thereby an assertion of the importance of Malanje to those events, a key component that most accounts overlook.17 Likewise, the street Ultra Machado is named after the Portuguese official who finally conquered Kassanje in 1911, but in practice almost no one would know it by that name and instead people know it as Xirimbimbi Road, connoting both a longtime elite and Malanje representative in parliament (currently in fact leader of the MPLA parliamentary group, as well as briefly being a Finance Minister) - ostensibly an emblem of provincial power and pride present in the capital - but also connoting ongoing rural connections, including with the Kassanje where there are still memories of a chief (soba) Xirimbimbi who was killed confronting the Portuguese in the revolt.18

In addition to the toponymy, the built environment (and its use) around the plaza also illustrates such polysemy, as well as socio-spatial connections between the city and both the countryside and Luanda, all in multiple configurations of potential meaning.

The plaza's importance is potentially marked partly by its position in relation to its immediate surroundings. To the east of the plaza are the two incomplete twin tower buildings, among the tallest in Malanje, which prior to independence were not finished by the major diversified conglomerate Sousa Machado Group. The towers show five floors of exposed brick, together with another floor and a half of open steel rebar and cement. The unfinished towers visibly testify both to the economic growth of the late colonial settler economy, its short-sighted ambition, and the turbulence of the postcolonial transition. The enclosed parts of the towers are inhabited and sit on top of a functioning complex of some importance. The ground floor has commercial shops, a bank and the offices of the notable Lusolanda car dealership. In between the ground floor and the towers are some offices of the provincial government, such as the Department of Commerce. Also there are the offices of the influential Malanje Old Guard League, founded in 1989 (known by its Portuguese acronym LIVEGUM, for Liga da Velha Guarda de Malanje).19

To the south is the landmark Triangulo restaurant. According to the owner, the restaurant began as a site selling hot dogs and sodas. It was just a retrofitted shipping container and then expanded to be one of the most consistent and central places in the city to get a meal, notably its lunch buffet, usually of cassava flour dough (funje) and toppings, as well as rice and pasta noodles (a testament to the profound effects of war on diets). As the owner described, 'Before installing the container, that space was a big dump. It was called the city dump'. The owner, however, was also a Vice President of Liga Velha Guarda, just across the road, and is the son of the head of Chamber of Commerce of Malanje. Illustrating again connections with Kassanje, another businessperson and former head of the Chamber, Pedro Kapassa, is part of the Kassanje Association and was a vocal proponent of building the Kassanje projects.

To the north is a large multi-storey apartment building. Characteristic of the tropical modernist style of buildings in Luanda, on the bottom there is a covered walkway supported by pillars, together with commercial shops. Above that are then five floors spread across an entire city block. The building was constructed by another prominent colonial conglomerate in Malanje, Vitorino Sampaio Magalhães (VSM). VSM was a member of the colonial Commercial Association of Malanje, but was most well-known for his cassava processing plant 'Mandioqueira de Malange'. VSM also had a large rice mill, had several thousand hectares of plantations, warehouses in Luanda and a Lisbon office on Rua dos Fanqueiros just up from the Praça do Comércio. During the Baixa de Kassanje revolt, VSM was a prominent voice requesting that the state buy arms for him and other white businessmen to lower the risk of losses from attacks. This massive building was therefore an urban representation of the strength of the colonial settler economy's extraction of surplus from the countryside.

Yet, after independence, the building became known as the Che Guevara Building. And Pedro Kapassa would also jointly begin in 2011 a revived Sociedade Mandioqueira de Malanje, allying with a colleague with a trading firm who had been based for a decade in the United States. By 2013 someone had scrawled graffiti in large black spray-painted letters at the very top centre of the building, 'Black Money' (in English), arguably not simply a racial cover for continued elite exploitation, and more a testament to actually changed conditions for black Angolans in a former settler city built on exploitation of countryside labour, as well as a prideful assertion of membership in a transnational black Anglophone diaspora.

To the west are two multi-storey apartment buildings that also illustrate the depth and strength of the settler economy and its geographical connections and rural roots. One building belonged to the key colonial trading firm Casa Americana Comercial, but part of its bottom floor was trashed and leaking, used as a dump and by homeless people. Next to it was a building mostly finished by 1974 belonging to Virginio Guerra, known as a Great Malanjean (Grande Malanjino), who had a plantation in Kunda dya Baze in the Baixa. Guerra had built in that site after buying it out and demolishing the previous old building from Vasco da Silva Luciano, who in 1946 was president of the colonial Commercial Association of Malanje.

In sum, while there are past and present indications of urban and elite importance, wealth, and power in the area of the 4 February Plaza, a closer examination of details and actual popular practices and meanings does not support a simple binary narrative.

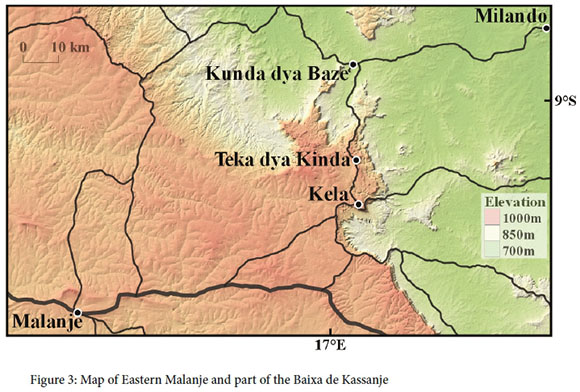

Origins of the Teka promise

Similarly with the 4 January Kassanje issues, it is crucial to recognise that there were inherent tensions from the start. On 20 August 1979, President Neto travelled to Kela, and, as reported in the Jornal de Angola, 'symbolically launched the first stone for the construction of a pilot village for peasants of that area, which should be concluded on the 10th of December of the current year'.20 After his previous days' visits elsewhere in Malanje Province (including inaugurating the new headquarters of the MPLA Provincial Committee), Neto travelled by car 122 kilometres to Kela, with people reportedly lining the roads to see the arrival (see Figure 3 below). The state newspaper, Jornal de Angola, described, 'Comrade President was in Teka-dia-Kinda (Baixa de Kassanje), where he offered a just and sincere tribute to the memory of the hundreds of compatriots interred there, who were assassinated by the colonial troops on the 6th of February 1961'. A month later however Neto passed away in Moscow due to hepatitis and pancreatic cancer. Two key things in this description are the incorrect suggestion that Teka is in the lowlands of Kassanje (in fact it is on the upper escarpment), and its accurate dating of the Teka massacre on 6 February, not 4 January.

The newspaper paraphrased how the municipal administrator of Kela, Adão Manuel Antonio, a survivor of the massacre, recalled that 'the first popular manifestation of revolt against the oppressor happened, in that area, in 1960 [prior to January!], when peasants, after having prepared their fields for cultivating cotton, stopped proceeding with their work because, as he affirmed, 'they were tired of being exploited and of enriching the pockets of the colonists'.

Antonio noted that after a public protest on 3 February 1961 in the Baixa, troops started to arrive, and then attacks (at Teka) started around 10am on the morning of the 6th - 'a date that I never will forget until the day of my death'. He noted that soon after that, there were aerial bombings. And he described, 'I did the burial of the hundreds of people that were barbarically assassinated here. Obligatorily.

The then Minister of Agriculture, Manuel Pedro Pacavira (a key MPLA figure and controversial in some circles), added that, as paraphrased by the newspaper:

... the MPLA worked in the Baixa de Kassange in a form that contributed actively to the achievement of consciousness by the peasants who courageously confronted the Portuguese colonialists . The Baixa de Kassange . served as example for other popular uprisings that occurred later, in all of Angola, which, at the moment, still pass unnoticed and only the attentive and profound study of our history, through real facts, will permit completely understanding.

He also went on to root the revolt in the great traditions of struggle of Kassanje, as a 'firm trench' (trincheira firme), including against 'puppets' and 'factionalism' (used to refer to UNITA, FNLA and others).

The pilot village would benefit a local cooperative, facilitating conditions for resuming cotton production. The sobas had a short dialogue with the President at the end of the event, presenting some of the difficulties in the municipality. The pilot village was described as similar to another one (unnamed), which was inaugurated by the President in Kwanza Norte, part of the area where the subsequent 'northern' or 'coffee' revolt had begun on 15 March (and which was a longer, larger and more brutal conflict). Various 'pilot villages' were announced, inaugurated, begun and completed, including one at Kiombe in Kwanza Norte (comuna de Kindissomo), Kimalalo in Uije, Itunda in Zaire and others.

The official Portuguese archive files support Antonio's version of events, noting that the army had left Malanje for Kunda, paused in Kela, and on 6 February sent a patrol ahead that was attacked (1 or 2 killed and 4 injured) and reported that they in turn had killed 70, injured 41 and captured 21. A large group of Angolans had gathered and were singing/chanting, and were fired upon with two machine guns and a bazooka fired in the middle of the crowd. The number killed is almost certainly only a rough estimate given the fact that the bazooka, in the report's words, 'opened in the middle of them a big clearing'.21

In the next section, I discuss how this 1979 commemoration and promise carried tensions that would reverberate decades later when 4 January was made a holiday, and after the war when calls and plans for a Kasanje memorial and pilot village were revived. In 2011, on the final Martyrs of Colonial Repression Holiday and the 50thanniversary of the assumed start of the revolt (not the exact anniversary of the massacre), state news headlines blared 'Minister [of Territorial Administration, Bornito de Sousa] visits site of future memorial to the martyrs of the Baixa de Cassanje', and quoted Malanje's Governor Boaventura Cardoso that they would build the memorial and 'social condominium' 'to honour the promise of the founder of the Angolan nation, Antônio Agostinho Neto'.

Briefly then, the tensions were threefold: (1) Martyrs of Colonial Repression Day celebrations are held not when the massacre happened in Teka (6 February), but rather are held on the day (4 January) that the concerted confrontations of the revolt started elsewhere in the Baixa; (2) Teka was not the only site of mass killings during the revolt; and (3) the fact that Teka was part of the revolt but is not actually physically in the lowlands points to broader geographies of revolt both in and beyond the lowlands.

The specificity of the place Teka and the date 6 February 1961 are extremely important because there were clear signs that the revolt that had started over a month prior was distinctly not limited to grievances about forced cotton cultivation and cotton prices. Rather, thousands of people were gathering across the Baixa (including some 3000 in the village of soba Kunda dya Baze by 1 February), arming themselves with weapons including guns, cutting off bridges and roads, destroying their tax and ID cards, attacking administrative buildings, calling the colonial government 'shit', and saying they would no longer obey the Portuguese and already had their own government. The significance of the fact that Teka is out of the Baixa is that the revolters with the proactive support of soba Teka dya Kinda were already expanding out of the Baixa and onto the plateau leading to Malanje city and the rail and road to Luanda, which would have marked a major new phase. It was at this moment that army battalions were urgently sent from Luanda, with airplane bombs dropped along the road between the Baixa and the plateau where Teka and Kela are located, clearing the way of potential ambushes and thereby allowing the Portuguese army vehicles carrying troops and weapons from Luanda to travel down to Kunda and elsewhere in the Baixa. By 8 February, there were reportedly some 10,000 people gathered at Kunda. A proper historically accurate recognition of Teka therefore would mean recasting the revolt beyond narratives of passive apolitical victims locally restricted to the lowland cotton zone.

Chronological narrative of Kassanje

After years of war and economic crises from 1979-96, the new 1996 holiday law meant that the still unfinished Kassanje projects would become intertwined with broader discussions of the significance of the Kassanje events. The challenges and tensions of the Teka project were compounded by the innate tensions in the 1996 holiday legislation, specifically between the label 'Martyrs of Colonial Repression Day' and the designation of the holiday on 4 January, which was the start of concerted conflicts in the revolt but not actually a day of the Teka massacre. The reasons for this revised law are not entirely clear (the law does not include text explaining or justifying why 4 January was added) and deserve further investigation, but some rough interpretations can be attempted.

The 1996 law adding 4 January was the most significant updating of national holiday legislation since independence in 1975. As Figure 4 below shows, there have been eight major revisions to holiday laws in independent Angola, spanning the period 1975-2018. Notably, the first law by the transitional government that included all three liberation movements did include 15 March but, after that joint administration was undermined, the MPLA government soon removed it, replacing it with holidays for the MPLA, May Day, and following President Neto's death, Hero's Day. With the transition to multi-party democracy in 1992, MPLA day was dropped.

The 1996 law was passed in September during an uneasy period of ceasefire following the Lusaka Protocol signed in October 1994, as well as economic turmoil resulting from the previous decade of war, low oil prices and some economic mismanagement. The government was attempting to garner international legitimacy, with the United Nations still hesitant to fully deploy peacekeeping troops, and meetings with the International Monetary Fund and World Bank also happening in September. The government had begun in July another set of economic reforms with the Nova Vida (New Life) program. In August, the rebelling opposition UNITA (National Union for the Total Independence of Angola) held its 3rd Extraordinary Congress at Bailundo, and there was a major blow to a compromise deal to end the conflict when Savimbi refused the post of Vice President. In this light, the national holidays for women and children can be seen as part of aligning with major international accords, while the holidays for Carnival, Day of the Dead and Easter can be seen as moving away from socialist secularism to appealing to actually existing popular cultural practices in this relatively peaceful but uncertain brief moment of precarious regime consolidation.

In addition to those general considerations, there were also significant conditions specific to Kassanje. The inclusion of the Martyrs of Colonial Repression holiday on 4 January might be read as part of the government's effort to militarily recapture the Kassanje area that was at the time the major source of diamond revenue (yielding hundreds of millions of dollars per year). The alluvial diamonds from meandering rivers of the Kassanje lowlands were accessible to unofficial/artisanal miners (garimperos) and a major source of potential revenue, but were controlled by UNITA since its capture in 1992 of the Kwango valley. This contrasts with later periods when the deep kimberlite pipes of the eastern Lundas would far outpace Kassanje diamond production (however, also requiring costly machinery and hence international companies and finance), as well as the major boom in offshore oil (including deep-water) production and revenue starting a few years later around 1998. In the first quarter of 1995 the government was attempting to recapture the diamond areas in Kassanje and restart a major diamond project at Luzamba near Cafunfo with the support of the Brazilian construction conglomerate Odebrecht (which had been involved since 1982 at the Malanje Kapanda hydroelectric dam). UNITA however continued to control these areas, building up its revenue and weapons, and, as the different parties undermined the Lusaka Protocol in various ways, outright war returned in December 1998, and only by around 2000-01 would the state recapture the lucrative diamond areas of the Baixa de Kassanje.

A related issue is that of the King of Kassanje, Kambamba Njinji Kula Xingu, who was anointed in 1961 after his predecessor was killed during the revolt, reportedly moved to Luanda around 1997, and who passed away in 2006. The analysis below will discuss the king(s) further, but it should be noted that after several years living in a hotel in Luanda, on independence day 2000, the Presidential foundation FESA provided him and his family (three wives and children) with three houses in Viana (Projecto Morar) as well as a car.

Might we interpret the MPLA government's designation of the Martyrs of Colonial Repression holiday on 4 January (and perhaps also FESA's support to the king) as a strategic political move designed to elicit support from people in the Kassanje area and hence recapture a lucrative diamond area? The emphasis of the holiday as a day for martyrs - as passive victims, rather than people actively revolting - could be seen to allow an appeal to the populations of Kassanje without necessarily disrupting the MPLA narrative as the first and exclusive active agent in the national liberation struggle. However, there is a fundamental question for such an interpretation of the holiday in terms of political strategy: why choose to commemorate passive martyrs on 4 January - a date before 4 February, and a date when people were actively revolting, rather than the later date of 6 February when the massacre actually happened?

It is not entirely clear how the date 4 January was chosen to commemorate the holiday. Among published accounts available at the time, Pélissier had identified 4 January as a possible starting date, based on the 1966 first-hand account by the key figure of Rosário Neto.22 It is likely that Neto (and others) was familiar with the events of 4 January through direct connections with Malanje and people in the area, many of whom were displaced or took refuge or rear-guard bases in neighbouring Congo. Neto was actively engaged with the UPA/FNLA (Union of Angolan Peoples/ National Front for the Liberation of Angola) and so their institutionalised knowledge may have kept the date of 4 January present over the decades. Moreover, Moises Kamabaya, a key scholar of the revolt and MPLA parliamentary deputy (formerly an FNLA member), had in 1989 returned to Angola from the United States and he may have also emphasised 4 January (having done so in subsequent work).

Regardless, the tensions that were already inherent in the Teka project were thus compounded by tensions in the 1996 national holiday law and over the subsequent decades these tensions would provide leverage for proliferating claims and contestation. Rather than state efforts to consolidate regime rule resulting in unquestioning obedience and quiescence, the actual effects were to not only passively provide more points of leverage for claims and contestation, but to also actively disseminate information and foster discussions that furthered such claims and contestation.

So when government plans to build a new memorial and village project were finally announced in 2010, it was after 15 years during which people used the holiday as an occasion to make various claims, including for building a monument, for development generally in the area and for pensions for people related to the revolt.

This period also saw the government increasingly formalise, institutionalise and proliferate holiday celebrations. Although the 1996 law does not have guidelines on how to celebrate the holidays (aside from an official day off work), state news reported extensive coordinated ceremonies, particularly 'central acts', including pronouncements at various cultural centres and laying of flowers in cemeteries and at tombs for unknown soldiers. Importantly, this was not confined to Kassanje, and the national celebrations of 4 January meant that discussions of Kassanje occurred at numerous sites across Angola. Such state institutionalisation and formalisation of the holiday activities was heightened in 2005 with details on the substance of each of the holidays, then again in 2007 with general directives on practices for celebrating the holidays, and again in late 2009 with specific guidelines for the 2010 celebrations, including for 4 January.

From the very start of available online state news coverage around 2000, it is evident that these moments were appropriated by a range of people - including various advocates, critics and/or opposition politicians - for their own purposes that seem to have been at odds with MPLA's consolidation of control of state and society. There are both spatial and temporal logics to the leveraging; advocates attending a memorial in 'Area A', for example, use that occasion to argue for extending an equivalent celebration of another Area B'. And likewise with events at different times: if we are celebrating 'Event A', then the equivalent 'Event B' should also be celebrated. Moreover, these divergent views were not unfrequently reported by state journalists, including as news story headlines, again contradicting simplistic portrayals of the state media as only an entirely controlled biased agency simply maintaining MPLA regime control.

Some of the key people in such appropriation and advocacy were affiliated with an Association formally registered in May 1999 (shortly after the 1996 holiday law and as the war in Malanje was winding down) - the Association of Surviving Children of the Baixa de Cassange: The Voice of the Baixa de Cassange. In addition, other key figures speaking out in the early 2000s were affiliated with the FNLA, which was the successor of the UPA, some of whose members were actively involved in organising the Kassanje revolt (particularly Rosário Neto).

In 2000, state TV read a commemorative statement on 4 January. The next year saw the 'Central Event' in Malanje city with the participation of the Interior Minister Fernando da Piedade Dias dos Santos 'Nandó'. However, key people were able to use events in Luanda to also make claims about Kassanje. For example, at an event at the Agostinho Neto Cultural Centre, the Kassanje King invoked Neto having met with sobas regarding the independence struggle. And on 3 February state press cited FNLA's Lucas Ngonda arguing for the importance of celebrating all three revolts, as well as emphasising pensions (echoed in 2003). The following year of 2002 also saw the Central Event in Malanje, with the participation of the Minister of Industry, Joaquim David, and flowers deposited in the Malanje cemetery. Meanwhile the King spoke again in Luanda, mentioning his efforts to get the government to convert Kassanje into Angola's 19th province, with accompanying increases in funding and authority. Months later, during an inauguration in Luanda of a statue of Njinga after Independence Day, the King spoke out again, and the FNLA's Holden Roberto also used the occasion to advocate for more monuments for other kingdoms also. Weeks later, the King spoke at the 2003 4 January events in Luanda, with his spokesman José Fufuta using the occasion to once more emphasise a 19th province, and that the Baixa needed a hospital, judicial system, police and other infrastructure. Although I cannot describe here all of the 100-plus such occasions over subsequent years, these examples illustrate how from very early on the state holiday was used as an occasion by different people in various places to make claims about the importance of Kassanje and related actions such as building monuments and distributing pensions.

With such increasing discussions, there was considerable confusion and elision about the actual events in Kassanje, though all of the details need not analytically preoccupy us much here, for example, the places involved, the timing of events, the number of people killed, the grievances or the use of napalm, which I and others have discussed elsewhere.

In addition - and this is crucially important - as discussions about Kassanje proliferated, the actual rhetoric about the holiday became more diverse with some elisions, claims and metaphors relating Kassanje explicitly to Independence rather than simply portraying it as passive peasants repressed for expressing economic grievances. In these tentative moves, a range of metaphors is used to connect Kassanje with the independence struggle. In 2001 the Uije governor said the 'uprising . served as an antechamber for the start of the liberation struggle'. In 2002 a government director in the coastal town Sumbe described 4 January as 'a cry for freedom', and, as paraphrased, 'the first steps of the Angolan people towards the conquest of independence'. A UNITA provincial secretary there also described 4 January as an antechamber of a patriotic struggle, as well as 'the opening of a path for the liberty and independence of Angola'. And the next year, Bornito de Sousa, speaking in the Baixa at Xandel in 2003, stated that the actions 'laid a stone in the conquest of national independence'. That year's government statement described 4 January as being 'of transcendent importance in the history of the national liberation struggle, since it marked the beginning of a revolt against 500 years of Portuguese colonial occupation'. The government's statement in 2004 described 4 January as when 'thousands of Angolans ... decided to revolt and cry for freedom', and the event 'germinated the independence and anticolonial movement'. And in January 2005, the FNLA described Kassanje as 'one of the first cradles of liberation of our country'. These sorts of elisions, metaphors and connections between Kassanje and independence continue annually to the present.

During the period 1999 to 2007, a great deal of important new information about the revolt itself was found, studied and published, and it may well have been familiar to key figures in national and provincial government, as well as the Association and political parties.23 The historian Aida Freudenthal carefully analysed newly declassified secret police (PIDE) reports at the Torre de Tombo archives in Lisbon and published a detailed academic journal article in 1999. In 2002 a lengthy magazine article was published, also drawing on those reports. Then, Moises Kamabaya published a book in Angola in 2003 with 10 pages on the revolt. The next year the German academic Alexander Keese published an academic article based on a large folder of files on the revolt at the Overseas Historic Archives in Lisbon. Then in May 2004, the head of the Civic Education for the Armed Forces, Egidio Sousa e Santos, himself from Malanje, completed his PhD in France on the history of the city of Malanje, with a substantial section on the revolt, partly based on discussions with key figures, which was translated into Portuguese and published in Angola in 2005. And in 2007, Kamabaya published his detailed book in Angola specifically on the revolt, mentioning Job Baltazar Diogo (father of Bornito de Sousa), as well as the father of the then Minister of Culture, Boaventura Cardoso. Sousa e Santos had also been in touch with Kamabaya and Job Baltazar Diogo.

In this context, claims began to appear calling for a monument. The first I have found is on 4 January 2004 by the FNLA, whose Political Bureau, headed by Holden Roberto, submitted a petition to the Ministry of Culture (headed at that time by Boaventura Cardoso), which, as paraphrased by the state press, asked 'that a monument be erected in memory of the peasants who were killed for defending their rights and for the liberation of Angola. The following 4 January the Bengo governor called for more historic monuments for all those who gave their lives for revolution and independence. Calls in subsequent years for a Kassanje monument are described below. It was after these calls for a Kassanje monument that the Malanje government briefly announced plans on 10 February 2005 for several monuments in the city, including renovation of the 4 February Plaza. This was also the time that the main 4 February monument in Luanda at Cazenga was being completed (construction began in September 2004), so it is possible that FNLA's call for the Kassanje monument came in reaction to plans for the Cazenga monument.

Perhaps in response to such proliferating rhetoric about the Kassanje events, by December of 2005, the Ministerial Council passed a resolution spelling out in official terms the objectives for the 2006 4 January Celebration, but in practice this appears to only have compounded the conflations.24 Predictably, the resolution on the one hand emphasised resistance actions ever since the start of colonisation and pacific peasants in the Baixa demanding better conditions for work and life, whose 'uprising ... constituted the seed from which would sprout the first action that was organised and had political-military characteristics, carried out by the heroic fighters of the 4th of February of 1961.

However, what is also highly significant is that the Resolution thereby conflated the specific date of 4 January with the commemoration of all who ever died due to colonial repression, including those who died during the officially recognised 'Independence Struggle'. While that could technically mean that 4 January was also a celebration of those who died on 4 February and thereafter, in practice because 4 January was already so tied to Kassanje in popular consciousness, it actually meant that it was difficult to differentiate among martyrs of the various revolts - hence discussing officially sanctioned Independence Struggle martyrs on the more general Martyrs of Colonial Repression commemorations each 4 January effectively gave to Kassanje itself a valence of being part of the independence struggle. For example, the resolution's own explicit objectives for celebrating 4 January were to '[r]emember the sacrifices made by the Martyrs of Colonial Repression, their determination, bravery and abnegation in the struggle against all forms of domination, oppression, and exploitation, aiming at the liberation of our people and the Independence of the Nation'. Weeks after this Resolution, that 4 January 2006, the governor of Huila would call for a monument to Kassanje.

With the minutiae of the holiday line laid out officially (but hardly clarified in practice) and the government flush with oil revenue and oil-backed loans to use for reconstruction and cultural activities, a little over a year later the Ministerial Council issued detailed instructions on the 'Organisation and Celebration of Holidays', mandating extensive planning, inter-ministerial coordination, rotating host cities, central acts, related events and literature, budgets, inaugurations, themes, lectures, interviews, and conferences.25 And again in 2009, a Ministerial Council Resolution tried to emphasise that 4 January was not specifically about Kassanje (the Resolution did not even mention Kassanje, and 2010's Central Event would be held in Uije), adding that the holiday aimed to 'valorise the memory of all the heroes who were felled by the cause for the independence and freedom of the Motherland, reinforcing patriotism and the culture of peace, tolerance, respect for common good, and unity and reconciliation between Angolans'.26

However, despite that effort, and amidst debates over the soon to be approved new constitution (3 February), it was that 4 January 2010 that Governor Cardoso of Malanje officially announced in Kela plans to finally build what is consistently called a memorial (not a 'monument') for 'the Heroes of the Baixa de Kassanje', as well as a pilot village. Moreover, he also pointed to not only the broader scope of the revolt (stating that it started in Milando rather than Teka), but also described how they had attacked colonial administrative posts (not simply cotton). Then, a month after this announcement of a new memorial and village projects, Governor Cardoso announced again the Malanje city's 4 February Plaza during the 4 February celebrations.

Understanding the calls for a monument and explaining why new plans for a 'memorial' were finally announced also requires going beyond simplistic binaries of urban/rural (and Luanda/provincial or strong/weak), as well as simplistic portraits of 'the rural' as local and denigrated. As already mentioned, the Kassanje King had been based in Luanda, as were many war refugees from the area (there is also a Baixa de Kassanje road in a neighbourhood of Luanda, Viana, which is along the road leading out from the Luanda east towards Malanje). After Cardoso was appointed Governor of Malanje in 2008, another call for a 'Historic Monument' was made the next year, on 4 January 2009 by the Governor of Uije (an important place in the 15 March revolt).

Moreover, key figures advocating for the monument from the Association had various urban connections. The Association had called for a monument on 4 January 2007 and 2008, and again during Independence Day 2009 the Association's Pedro Kapassa spoke in Luanda with ANGOP about the need for a monument. Meanwhile, in Malanje that same day, Governor Cardoso held the Provincial Independence Day celebrations in Kunda, with ANGOP paraphrasing his statement that 'the independence struggle had a contribution from the people of Kunda dia Base municipality'. FNLA had also spoken in Luanda the previous year for a Kassanje monument. Kapassa spoke out again in Luanda a month later. Kapassa himself was not only affiliated with another association for the Kaombo municipality in the Baixa, but also is a businessman with interests in fishing and timber, as well as being head of one of Malanje's major football teams since 2005, and in 2009 the President of the Malanje Commercial and Industrial Association (ACIMAL), the successor to the Portuguese association whose building is now occupied by the MPLA, and which Neto had inaugurated prior to his 1979 visit to Teka. In addition, another person who was a key director of the armed forces had personal connections to the revolt, and the Malanje Governor himself (also a former Minister of Culture), as well as the Minister of Territorial Administration (and, since 2017, Vice President), were all sons of figures important to the Kassanje mobilisation, though they have rarely spoken publicly about that. In short, rather than some abstract amorphous 'master narrative' bogeyman operating to quash the project, we can see in fact that some of the highest figures of the MPLA party also have direct connections with the history of Kassanje.

It is also worth revisiting here the question of whether controversial issues related to diamond mining in the area played any role in relation to the ongoing discussions of the holiday and monument. This is not entirely clear, but, broadly, after the war's end in 2002, informal diamond production continued but also abuses by the military and private security were reported (including in areas of elites' companies), prompting some reorganisation of the mining regulations from 2007 to 2009. Generally though, production was shifting to the deep eastern kimberlite pipes, so the Kassanje area was declining in relative importance in terms of contribution to the state budget.

Prior to the elections in August 2012, on 4 January 2012 specific plans finally were officially announced to design a memorial and model village. A major forum was held at the amphitheatre at the training college in Keswa, which I attended. In addition, an amount was also allocated in the 2012 budget, equivalent to $300,000 for a 'memorial and social neighbourhood in Teka dia Kinda'. A Malanje Provincial Government Commission on Holidays met and discussed ideas with traditional authorities and contractors.27 The project was to only be 900 square meters, with work supposed to start in 2013. São Paulo-based architects Renato Rossi Aquitetura drew up larger plans, with AXL as the builder (though it is not clear whether these were proposals or contracted plans). AXL also had as a major investor the firm Multinvest, held by Aguinaldo Jaime, a key central government director in banking, finance and investment. The plans from Rossi - who had submitted plans on a range of projects in Angola including hotels and even soccer stadiums - are rather bizarre digital graphics, having no indication of any relevance to the actual revolt and, using images plopped on top of a satellite picture of the rural bush, show an impractical massive pool and lawns, a bike path, parking lots and large half pipe covers over seating, with faceless people standing, walking and bicycling about.28 The plans for a memorial and village projects were reiterated by Governor Cardoso on 4 July, emphasising that Teka dya Kina would be a new 'rural centrality'.

Here it is important to clarify that such 'model villages' were not simply urban elite modernist visions imposed top-down on rural victims. In this case a village project of some sort is being claimed by rural people themselves (not all, of course). In addition, there is an important longer story of the rural roots of housing projects in Angola (going back at least to the 1906 hut tax, for example), which has been ignored in all the attention to urban redevelopment in Luanda.29 Resettlement has an especially important history in Kassanje, both after the 1911 conquest and also as an aspect of cotton production fostering the revolt.30

After July 2012, there were elections in August, a change of the Malanje governor in October and continued deterioration in the national economy, and there seems to have been little news about concrete plans for the memorial/monument and village projects until about 2016, and I will pick up the story from that time in the below sections.

In the meantime, the new Kassanje King (Kambamba Dianhenga Aspirante Njinji Kula Xingu), the Association and others continued regular claims for restoring the holiday, building the projects and instituting pensions. In April 2012 the Association had actually changed its name from Kassanje to 4 January, ostensibly to be able to advocate more broadly for the Martyrs of Colonial Repression Day restoration, rather than only for Kassanje. During the 4 January 2013 celebrations following the August 2012 elections, claims for reinstating the holiday were reportedly made by the Association, the FNLA, and the historian Cornélio Caley. That day the memorial was also advocated by the Association, the historian Pedro Almeida Capumba, and the Luanda Cultural Director Manuel Sebastião. And the soba of Teka reportedly hoped for the realisation of Neto's promise of a village project (as described in the previous year's plans).

In addition, claims for pensions continued. During the major 50th anniversary celebrations, there were calls for pensions by the Association, repeated in 2012. The new Malanje Governor also had some prior experience in dealing with ex-soldiers as the Minister for Assistance and Social Reinsertion from December 1992 to April 1994. In October 2012 there was a Voice of America report of possible Kassanje pension talks between the MPLA and the Ministry of Former Combatants and Motherland Veterans. Survivors born before 1930 and their descendants would be eligible, including from the Baixa de Kassanje. This was swiftly criticised by an opposition figure who argued that following that logic, pensions would have to be expanded to others as well.31 A response of sorts came from the actual Minister of Former Combatants and Motherland Veterans, Kundy Paihama, speaking on 4 January 2013 in Xa Muteba in the Baixa with a veiled warning: 'All those who falsify data with the objective of benefiting from pensions to which they do not have a right will have to account with justice. Therefore, I call on associates to denounce falsifiers.' This possible rebuke however has not reduced claims for pensions, and indeed administration of pensions has been publicly contested. Undeterred, the King spoke out again about pensions at the following 4 January 2014 celebration (repeated in 2017 and 2018).

Claims for Kassanje pensions tie into weighty national issues of budget priorities and administration. Military and police expenses include pensions and expenses on 'un-retired' staff - people in the still bloated army (and some who were transferred to police), which at great expense has kept in state employ tens of thousands of people who could potentially be destabilising if dismissed and unable to find work. Some compulsory demobilisations occurred after 2002, and from 1998 to 2017 over 71,000 soldiers have retired. As of 2019, a reported 117,000 people were already still waiting on assistance for reintegration.32 Moreover, finding a way to dismiss more of the existing military and police staff (and hence reduce the budget percentage going to security) entails modifying the military careers laws, and consequently taking on some powerful and wealthy groups that have become entrenched over the years. While the police law was amended in 2008, the changes to the military career law were proposed in 2007 but were only approved in mid-2018.33

To help cope with the bureaucratic strain from rising numbers, a Modernisation of Management Program began at the armed forces' pension fund. In March 2009, Paihama had created an inspection commission, which three months later found irregularities, ghost recipients, duplicates and bribes. There were also complaints in 2012 about lack of adjustments for inflation to pensions.34 Roughly 60 per cent of over one thousand generals were said to be going into retirement around 2013.35 A new director for military pensions was appointed in 2014. So whereas in 2012 the armed forces already reportedly lacked $100 million when there were 60,000 military pensioners (with 20,000 waiting to enrol), by 2019 there were reported 162,000 ex-soldiers receiving pensions with a further 12,000 not properly registered and tens of thousands more still waiting to enrol, and recipients were urging a more than doubling of the monthly pension payments.36

These above descriptions help to address (though not completely) the question of how the new government plans for a new memorial and village project at Teka came about. The next complicated question is why have this memorial and project not actually been built yet? These questions are in fact related, as is a third question: why was the holiday demoted in 2011? My argument is that the memorial and project have not been built yet because the actual large extent of mobilisation means that such construction could potentially itself be used for further leverage for claims whilst the government is already struggling to finance and implement a geographically complicated reconstruction program. In other words, rather than the projects not being built because the rural areas are insignificant and Kassanje is not part of a ruling party exclusivist 'master narrative', I suggest below how it may not have been built because it is potentially too large and too significant.

Why demote the holiday?

First, however, with regard to the holiday demotion, the proximate timing of both events around 2010-11 could be interpreted as the memorial and village project announcement also being used as a cover to appease peoples' discontent over the holiday demotion. Such an explanation is suspect because the projects have not even been built and the demotion has in fact prompted even more claims, including about the need to restore the holiday. But why even demote the holiday at all? The explicit reason given in the legislation itself was about the need for a balance between holiday celebrations and the requirements of reconstruction given the changed circumstances of the country (so, essentially, to not have so many days off from work).

Moreover, it is important to recognise that 4 January was only demoted from a national holiday (with time off from work) to a Day of National Celebration. It was not the case that commemoration would be eliminated altogether in favour of an MPLA monopoly, and indeed state-organised celebrations of 4 January have continued in various forums, including mandatorily in all schools.37 In addition, although Schubert emphasises 'how the history of Angolan nationalism and the liberation struggle has been monopolised' in the post-war present era, he incorrectly cites as an example 15 March being removed as a holiday with the 2011 law, when 15 March had in fact been removed 36 years prior. And indeed the 2011 law actually legally enshrined recognition of 15 March (as a Day of National Celebration), reinstating it after decades of absence, which suggests not absolute monopolisation but actually rather efforts to open up and diversify narratives.

Shortly after the Kassanje holiday was demoted, claims for its restoration increasingly appeared. The demotion of the holiday on 11 February 2011 also coincided with the start of the 'Arab Spring' (with protests in Tunisia in December, the fall of the Tunisian government on 14 January, protests in Egypt on 25 January and protests starting in Libya around 15 February). In March, activists in Angola also called for protests. The ongoing dynamics over the next years of critique, protest, repression and reform in Angola would interweave with claims about the 4 January holiday, Kassanje monument, regional infrastructure and pensions, as I chronicle below.

Protests, local initiative, official party promise, rehabilitation and more ephemeral promises

The ongoing lack of construction and the holiday demotion only further increased claims. On 4 January 2015, there were plans for a protest to restore the holiday, including gathering at the 4 February Plaza in Malanje city, but it was repressed by the police. The previous month, December, counter-regime protests in Luanda had also been repressed. And in the following May, a protest by ex-military in Luanda was also repressed. In May, the trial concluded for human rights campaigner Rafael Marques (writing regarding diamonds in Kassanje), and in June so-called 'revu (revolutionary) youth activists were arrested, with charges announced in September of rebellion and attempted coup (ultimately dismissed).

In July 2016, after all these delays, state media reported that local administrators were actually taking their own initiative to build a different monument/memorial, albeit in Kunda rather than in Teka. This also came after pressure from local traditional authorities. State news variously refers to this new project in Kunda both as a memorial and a monument. The 20 square meter project was done by a local firm, Zé Pango, and included a cemetery with the remains of four sobas (Santos, Minguito, Capapa and Cabo), as well as a tomb for unknown soldiers. Days after the July announcement of this local project, the Malanje governor noted the need to construct a memorial at Teka. The local Kunda monument's completion and inauguration was announced by state media a week before Independence Day in November 2016 - another instance of national celebrations being leveraged for local initiative.

Such local initiative then subsequently had broader effects. Notably, several months later, the MPLA committed in writing to '[c]onstruct a memorial to the martyrs of the Baixa de Cassanje', as part of its detailed Governing Program for 20172022. The MPLA launched this program in February, after the 2017 4 January celebrations (in which the Malanje governor laid flowers at the cemetery in Teka), and in anticipation of elections that happened in August 2017. Perhaps in anticipation of the elections, that January, the Association and Kassanje King had made a range of claims for pensions, for restoring the holiday and for a memorial and the village project.

Then, after the elections, in January 2018 the King repeated these claims for pensions and restoring the holiday. Shortly thereafter, sometime in early 2018, work began by the Malanje Provincial Government to rehabilitate the cemetery - including working on the fencing, porch, field and other aspects - which was inaugurated on 17 September, Hero's Day, to celebrate Neto (again, leveraged for provincial initiative). This however, constituted smaller rehabilitation work by the Provincial Government, not the full-fledged construction by the national government of a new memorial promised in the MPLA's electoral Governing Program 2017-22. The rehabilitation is nonetheless important because it does not fit with an obvious simple political logic -it is an example of work that was not actually promised (the promise had been for a new project) and it happened after rather than before elections.

At the end of that year, on 13 December 2018, the Minister of Culture stated that the 2019 public investment program of the budget would include funds for a 'Baixa de Cassanje memorial' (mentioned along with memorials at Ebo and Ambuila, the Ngola cemetary and others), though I have not found a specific line in the budget for it. The next month, on 4 January, the Association and King again claimed for the monument, pensions and restoring the holiday.

Conclusion: why not build?

It is difficult to explain why the monument and project have not been built. This is partly because it is difficult generally to explain many internal state decisions, peoples' motivations generally, and counter-factuals (why something did not happen). As mentioned above, a 'pessimist' interpretation would suggest the monument was not built because elites denigrate rural areas and control challenges to MPLA master narratives about its exclusive role in national liberation. However such an approach cannot explain why a small token monument was not done (as has occurred elsewhere) - and indeed a small improvement was done - nor why the state has done other kinds of projects in the area, nor why the state consistently goes out of its way to emphasise Kassanje each January. If state celebrations are designed not to occlude entirely but rather to co-opt, then why still perpetually defer actually building a new memorial? There might be several possible reasons, including priorities, strategy and/or bureaucratic incompetence or red tape.

The next paragraphs emphasise how co-opting is not an easy, discrete, seamless act - there is no 'co-opt' switch to flip on a control board. Appreciating that also requires moving away from a view of space as flat and passive and over which the state 'broadcasts' power (an 'aerial' view), and instead viewing space as continually produced in a dynamic thicket of social relations in which any intervention has multiple reverberations, as well as having multiple potential connections and meanings that can be activated.

A Machiavellian view might explain deferral because the strategic importance of the Kassanje area had declined relatively, while the perceived threat from popular mobilisation increased. But again we are left to explain why state celebrations occur but not a constructed project. Efforts to use celebrations to co-opt Kassanje also carry the possibility of making the state more susceptible to claims because the decades of officials' statements glorifying the participants and extolling the significance of the day imply that a small gesture would not do, and might be seen as potentially trivial-ising, as disrespectful, or a state failure to fulfil its responsibility.

Some government officials have stated that the project had not been implemented due to budgetary difficulties associated with the economic downturn. For example, on 29 April 2016 the Municipal Administrator for Kela was paraphrased stating that the budget for the 'cemetery/monument' had been approved in 2015, but was delayed because of the economic-financial conjuncture, including low oil prices. Such an explanation is more plausible only for a large expensive project, so what is key are the broader potential implications and geographies of Teka.

Part of the reason for deferral may thus have to do with concerns about proliferating claims that would be seen as complicated and/or expensive. As mentioned in the introduction, the model village plans for Teka were relatively large and included 30 houses for people linked to massacres, a meeting space (jango), primary school, medical post, leisure area, plaza with a garden, water mirror, conference room and a library to consult studies on the massacre. As Governor Cardoso noted, 'it is an ambitious project that has social, cultural and recreational sides'.

While the MPLA has recently reiterated its commitment to building a memorial, it does not appear to have said anything about the pilot village since Cardoso promised in 2012 to fulfil that pledge by Neto. Yet rather than functioning to co-opt Kassanje, these actions have only continued to prompt claims.

Such state moves at controlling and co-opting the narrative are influenced by Teka's specificity and the accumulated innate tensions there. In not building a monument, and in restricting itself instead to a memorial, the MPLA state has thereby also simultaneously bound itself to the massacre site at Teka and hence also bound itself via that site to the linked Neto pledge there for a pilot village, which then potentially opens up the state/MPLA to expanded claims throughout the Baixa for such larger village projects (effectively, 'if Teka got one, we deserve one also').

To recap, Teka was the first massacre but not the start of the revolt, nor the only mass killing, and is not physically in the lowlands. As one begins to explore the actual knotty issue of some discrete 'origins' of the revolt however, one rapidly finds complex spatial and temporal concatenations that contributed to the revolt. So although hitherto the first acts against colonial agents were reported to be on 4 January, people were also reported to have taken actions in Kassanje against colonial property and livestock earlier in December, and possibly November. As Freudenthal notes, violent political anticolonial unrest in Kassanje started even months earlier, at the time of Congolese independence itself, around June 1960.38

Far beyond the few hundred people in Teka, the Kassanje Association was reported to have tens of thousands of associates (though the number varies in news reports over the years, and it is not clear how they are counted). But if projects of the scale mentioned in the Teka plans were carried out for all these tens and tens of thousands of people throughout the Baixa who were affected by the revolt or are descendants of people affected, then, aside from the complexity of regional planning, the costs would likely be in the hundreds of millions of dollars, if not billions (not to mention pensions also). Moreover, beyond even the plans for the Teka village, the 4 January celebrations have been repeatedly used to espouse claims for greater development including schools, health posts, roads and bridges, TV and radio towers, electricity, water, agricultural schemes and so on.