Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Kronos

On-line version ISSN 2309-9585

Print version ISSN 0259-0190

Kronos vol.42 n.1 Cape Town Nov. 2016

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2309-9585/2016/v42a13

ARTICLES

Johnny Fingo: war as work on the Eastern Cape Frontier

Hlonipha Mokoena

WiSER (Wits Institute for Social and Economic Research), University of the Witwatersrand

ABSTRACT

'Johnny Fingo' is a character and an archetype. He appears in the memoir of British soldier Stephen Bartlett Lakeman, titled What I Saw in Kaffir-land (1880). In the text he is oblivious to pain even as he bemoans the irreparable damage to his Westley-Richards rifle. He is a leader of the 'Fingo' African levies. He can therefore be distilled into a history of the general presence of African levies on the Eastern Cape frontier. Although soldiers, Johnny Fingo and his levies are also defined by their sartorial choices, as captured in the words of Lakeman and other British officers. This article explores how the nineteenth-century South African figure of the 'African levy',[1] an irregular and underpaid soldier, foreshadows the emergence of the more enduring archetype, namely that of the 'Zulu Policeman'. Both of these characters/archetypes are bound by the fact that they were paid to fight; war was their work. This world of war work was, however, not sterile; both 'Johnny Fingo' and the 'Zulu Policeman' wore clothing (uniformed non-uniforms) which made these men swagger.

It is very curious to see the cast-off clothes of all the armies of Europe finding their way hither. The natives of South Africa prefer an old uniform coat, or tunic, to any other covering, and the effect of a short scarlet garment, when worn with bare legs, is irresistibly droll. The apparently inexhaustible supply of old-fashioned English coatees, with their worsted epaulettes, is only just coming to an end here, and is succeeded by an influx of ragged red tunics of franc-tireurs, green jackets, and much-worn Prussian grey coats. Kafirland [sic] may be looked upon as the old clothes-shop of all the fighting world, for, sooner or later, every cast-off scrap of soldier's clothing drifts towards it.[2]

How much has been concealed, how much has been defended in Aprons! Nay, rightly considered, what is your whole Military and Police Establishment, charged at uncalculated millions, but a huge scarlet-coloured, iron-fastened Apron, wherein Society works (uneasily enough); guarding itself from some soil and stithy-sparks, in this Devil's smithy … of a world?[3]

Introduction

Writing about war is propaganda. There is no neutral way of writing about the soldier's work. The human costs of war are such as to focus our attention on the horror and the tragedy. Thus, the symbolic power and desirability of the soldier's clothing - whether a uniform or not - seems like an odd object of study. The propagandist nature of narratives of war turns almost entirely on the fact that the only sources we have for knowing what it is like to be in a war zone are the accounts of the combatants themselves. As the recent historical experience of 'embedded journalists' being introduced into combat zones by the US Department of Defense during the Iraq War (2003-2011) illustrates, even the accounts of eyewitnesses may not be all that reliable. The contradiction inherent in this article is that in it I write about the clothing worn by African men who served in armies and police forces without actually writing about war or violence. In my research so far, I have found no images of Mfengu levies or Zulu policemen in action. This already signals the workings of a propagandist archive. The most 'violent' pictures I have found involve the arrest of a suspect (these are common in the history of Africa and have been written about).4 What has not been theorised, is the aesthetic appeal of these photographs. When confronted with the word 'swagger', it boggles the mind to think through what a word such as this is doing in a war zone or any zone of policing and law enforcement. It is words like these (and their visual accompaniments) that this article is chasing and attempting to historicise. I take it as a given that, as the 'silent warriors' in these accounts, African levies and policemen didn't really represent themselves; they were represented by others. However, I also take it as a given that there are limits to both compulsion and invention. Although constrained by the very fact of being enlisted and conscripted, African men seem to have displayed an inventiveness in their dress that cannot be dismissed as 'war propaganda' or mimicry of their white officers. As Carolyn Hamilton has cautioned us in relation to Zulu history in general, invention is only effective if it presents a horizon of plausibility.5 Thus, although the masculinity of Zulu men (and their Mfengu predecessors) was warped and tainted by its colonial desirability, it doesn't mean that Zulu men didn't command a self-elected presence. For colonialism's capture of Zulu masculinity to be effective for the purposes of war, it had to present these men's masculinity as being continuous with some notion of precolonial self-image or selfhood. Colonialism simply didn't have the creative power to wholly 'invent' the Zulu man or by extension the Zulu policeman without the participation of these men. This is because the very notion of 'Zuluness' was being created and contested, and could therefore not be easily enfolded into a colonising project.6 It is not surprising that the colonial archive is replete with photographs of African subjects. However, photographs of policemen constitute a category that deserves to be studied separately from other kinds of photographs. One of the justifying positions of this article is the observation that studies of colonialism and empire in South Africa have mainly focused on the state either as a receiver of revenue (through taxation mainly) or a surveillance apparatus (through practices such as pass books). Rarely is the colonial and imperial state written about as a consumer. In this article, the 'Zulu policeman' is depicted as a surrogate embodiment of the state as consumer, since the uniform that he wore was purchased by the state and its distribution regulated by the state's policing departments. This does not mean a re-definition of the state as 'ornamentalist',7 rather it requires a close analysis of the ways in which state institutions participated in the making of the Zulu policeman's image. That is, it implies an examination of the minutiae of colonial decision-making: the type of cloth that was used for the uniform, the choice of supplier or source, the design of the uniform itself and the dress codes to which policemen had to conform.

The word 'red', given by Simon Gush and James Cairns as the title of their 2014 documentary,8 evokes many contemporary and historical metaphors and images: the colour of blood, the promise of the sickle-and-hammer flag of the former Soviet Union, danger, warning, and so on. When read through the history of mercenaries on the Eastern Cape frontier, there is an obvious link to the fact that in Thomas Baines's painting The Loyal Fingo, the main subject wears a red 'do-rag'9 underneath his feathered hat. Ahead of him on the march is another mercenary who is also painted wearing red headgear. In the 1990s, the internecine warfare that tore apart Gauteng's East Rand townships was accompanied in news reports by the shadowy figure of the 'Zulu impi' wearing red bandanas. Thus, in that context, red became the colour of collaboration and third-force menace. Although the workers in the Mercedes-Benz manufacturing plant had other reasons for choosing red as the colour for Nelson Mandela's custom-made vehicle there is a sense in which this colour was already over-determined as a symbol of the end of the apartheid era and the start of democratic rule. When read historically, however, what emerges is an image of the mercenary and the factory worker as 'fabricators' who were using colour as one of several components that constituted the creation of an unauthorised 'uniform'. In making a red Mercedes for Mandela, the workers were deviating from the dark colours that are often used as the 'status symbol' of power and statesmanship. Similarly, when the Mfengu levies sewed their own clothes or purchased second-hand uniforms, they were deviating from the norms of military and police regulations in which colour is rank and synecdoche (where 'Redcoats' stands in for the whole British army). Thus, when positioned in relation to Simon Gush's work - the documentary and the exhibition - Johnny Fingo and the Zulu policeman represent an antecedent of uniforming, the enduring palette of which is later inadvertently referenced by the striking workers when they fabricate their own uniforms (and choose the colour of Mandela's car).

Granted, the 'Zulu policeman' is part of the colonial archive and thus similar to any other of the colonial subjects who were captured by the camera.10 The condensation of colonial subjects has served to make photographs of Zulu policemen collectors' items and the stuff of military enthusiasts. The popular imagination11 was, and continues to be, fascinated by photographs of Zulu men in uniform. These images are frequently auctioned on websites or posted on blogs by self-identified amateur military experts who routinely discuss the source, history and meaning of the photographs they post. To excavate these photographs, therefore, also means accounting for their continued monetary and nostalgic value.12 However, since a vast literature already exists on African photography and its relationship to other aspects of African history, it is important to justify the relevance of Johnny Fingo by showing how he relates to the extant body of literature.13

To be clear, the basic link between the character of Johnny Fingo and the 'Zulu policeman' is that the latter's designation exists almost solely in the photographic archive so we can never be certain if Johnny Fingo was a real person.14 Therefore, the first thing to note about Johnny Fingo and his successor, the Zulu policeman, is that they are both personae whose existence is mostly confirmed by artistic representation. The second thing to know about the 'Zulu Native Policeman' is that he is preceded in history by a rabble of levies, regiments and mercenaries. This latter history is most emblematically represented in a painting by Thomas Baines - South Africa's father of landscape painting.15 Baines (1820-1875) was born in on 27 November 1820, in King's Lynn, Norfolk, England. In 1842, he travelled steerage to Cape Town where he began to practise his art commercially. In 1848, he joined an ox trek north to the Orange River and gained his first experience of travel into the interior, sketching and painting. In 1851, he enlisted as an artist with the British army in the 'Kaffir War' (Cape Frontier War) of 1850-1853, before returning to England. The painting is titled The Loyal Fingo and it depicts African levies in motion. There are many things to be noted about this depiction, but first it is important to briefly describe who the 'Fingoes' (colonial name) or amaMfengu were. The identity of the amaMfengu is linked to the controversy over the meaning of the 'mfecane' (the social and political upheaval caused by the rise of Shaka Zulu). Like many other ethnic identities in southern Africa, the amaMfengu enter the scene of colonial conflict and encroachment as 'refugees from Shaka's wars'.16 In 1835, they supposedly signed an alliance treaty with Britain and, in exchange for land, Christian education and evangelisation, agreed to be the allies of the British against the Xhosa as the former extended the Cape Colony into the eastern Cape. Baines's painting depicts an Mfengu levy with a rifle slung over his shoulder with multiple objects of adornment and practical use on his person. For our purposes it is not the details that matter but the very arbitrary and meddled quality of his attire. Without the rifle, there is nothing particularly militaristic about his apparel - the feathers in his hat, the genet tail and horn hanging from his waist all suggest sartorial choice rather than military regulation. This painting is pleasing to the eye because of its irregular combination of rugged practicality and spectacular dandyism. From the perspective of postcolonial theory and the general criticism of colonial representation, this painting is fiction. It has become the accepted position to read such paintings as fantastical, that is, to understand them as being partly based on reality but mostly the products of the imagination of the painter who is often depicted as eager to 'exoticise' his subjects while presenting the landscape as an idyll ready to be conquered and subjugated to Western industry and cultivation. Baines fits into this stereotype of the colonial 'amateur' ethnographer. Not only did he paint and sketch scenes from his expeditions, but in 1854, via his contacts in the Royal Geographical Society (RGS), he joined an expedition to Northern Australia as artist and storekeeper. He returned once again to the Cape in 1868, this time as 'exploring superintendent and geographer'17 for the South African Goldfields Exploration Company, with prospecting sights on Matabeleland. The Loyal Fingo cannot, therefore, be read as a visual reflection of the 'liberty' - to dress as they pleased - that was enjoyed by African levies and mercenaries. Yet, for our purposes it is a starting point for a different kind of enquiry. If we accept the argument that these kinds of paintings are not an accurate depiction of reality then the question that logically follows is: what happens when the camera is introduced and colonial armies and police units are captured through the lens? In his essay, 'Little History of Photography', Walter Benjamin warns against what he terms 'the dubious project of authenticating photography in terms of painting'.18 This article is not attempting such dubiousness. Rather, it is about the colonial transition from painting to photograph that, as James Ryan argues in Picturing Empire, made photographs then and now the 'eye of history'. He goes on to state that the assumed 'exactitude of the camera' could not have emerged 'without the pictorial conventions of perspectival realism that it inherited via landscape painting'.19 In the case of the Zulu policeman, the point is not only to demonstrate this shift from painting to photography, but also to enumerate the pictorial conventions which informed the creation of this archive of photographs and which now allow us to reconstruct elements of the 'collective colonial memory'20 that continues to animate these representations.

The Loyal Fingoes

While Baines was painting Mfengu levies, a complementary war literature was taking shape as soldiers and officers wrote about their 'frontier' experiences. A different picture of the Mfengu emerges from this body of literature. To build on the supposition that the Zulu policeman as a type is a direct descendant of the African levies that were used by the Cape colonial government to fight 'frontier wars' in the nineteenth century, let us turn to Peires's description of the events that precipitated the War of Mlanjeni (1850-1853). In this description, Peires makes a passing observation about the African 'collaborators' who defected and rebelled against the British and joined the Xhosa in the fighting. He writes:

Meanwhile the 'Kaffir Police', a paramilitary body of trained collaborators, rebelled against their white officers, and the Khoi settlers of the Kat River Valley discarded their traditional alliance with the Colony to join the Xhosa in an all-out war against white domination in South Africa.21

The existence of these 'Kaffir Police' hints at the use of collaborators of all kinds. Similarly, the memoirs of white officers who fought in this war attest to the presence of African auxiliaries. Since what we are concerned with here is not the act of collaboration but the clothing of the collaborators,22 it is apt to turn to a description of the dress style of the Mfengu levies found in the war journal of William Ross King. From his description, we are given the impression that, on receiving their pay, Mfengu levies would spend time and money purchasing clothing. He paid particular attention to the varied and spectacular quality of their choices:

In town the young men get themselves up in the most extraordinary style, with smart ear-rings in their ears, and school-boys' caps stuck on the top of their heads, with red and blue velvet tassels; and you daily see them at the stores, laying out their pay in second-hand European clothes - blue coats with brass buttons, tight fitting surtouts, and fashionable pantaloons; an accompanying party of friends assisting and advising with the greatest gravity. Some showed a strong military turn, stitching broad red stripes down their trowsers [sic], or with an old Cape Corps jacket, swaggering about with a rusty sword and spurs. But in the field, this attire is laid aside, and the same fellows pass you on the line of march, at the double, with a 'Hi Charlie',23 their dirty blanket, and raw beef tied on their backs, and no other clothing than a checked cotton shirt.24

The use of the word 'swagger' points to the fact that for these Mfengu levies being dressed in European clothing - especially the 'military' styles - led to a particular sway and shifting of the body which was in direct contrast to how they walked and were attired when they were in battle. When they were doing battle, the levies also seemed to prefer European rifles, muskets and flintlocks rather than what would be expected to be their preferred 'traditional weapons'. The contrast is starkly drawn in the following two excerpts:

Just as the regiment was assembling for service in the centre of the camp, on Sunday morning, we were startled by hideous yelling and cries from the Fingoe camp, whereby the service was delayed for some time. For seeing the Commandant of the garrison galloping over, followed by other officers, one and all bolted after them to see what was going on, and found the Fingoes fighting about the division of rations. There were several hundreds of them struggling like demons, in clouds of dust, yelling out their war-cry, and challenging each other. All were perfectly naked, the blood running down the black faces and breasts of many from the blows of 'knobkerries,' or clubs, which they applied to each other's heads with such astounding force that the very report was enough to give one a headache.25

Johnny26 Fingo, in his haste to shoot these poor devils, whom we had stealthily crept upon (having seen their camp-fire a long way off), forgot to put a cap on his rifle, and as the gun only snapped fire as he pulled the trigger, some three or four feet from the head of one of the disputing marauders, he received in return a lounge [sic] from an assegai through his thigh. The rest jumped suddenly up, and an indiscriminate mêlée took place. Poor Dix received a fearful crack on the skull from a knobkerrie (he was never perfectly right afterwards); Johnny Fingo got another stab in the legs, and, what affected him still more, his beautiful 'Westley-Richards' double-barrelled rifle, which he had obtained, Heaven knows how, was irretrievably damaged.27

Johnny Fingo, as his hybrid name implies, was an Mfengu, who earlier in the text is described as the 'chief' of the levies. He functions in the second excerpt as the perfect embodiment of the African auxiliary. His singular concern for his 'Westley-Richards' despite his injuries and despite his witnessing the use of the knobkerrie on his fellow soldier, shows that, even as early in the nineteenth century as the 1850s, African levies did not as a matter of practice only use knobkerries either for fighting or even for symbolic display. Johnny Fingo saw his power and authority as resting in his rifle and, as reported by Lakeman, 'although badly wounded and unable to stand, was bemoaning his broken rifle as it lay across his knees … he repeatedly asked me as to the possibility of getting the indented barrels of his rifle rebent to their original shape.'28

If Johnny Fingo and other African levies valued their rifles so much, why are their successors, the 'Zulu policemen', photographed holding knobkerries? One possible way to answer this question is by posing another. Writing about the end of the 6th Frontier War of 1834-1835, Storey, in his book Guns, Race, and Power in Colonial South Africa, makes the following observation about Sir Harry Smith's famous address to the Xhosa chiefs:

The establishment of civilization through commercialization and also through the undermining of the chiefs became established 'native policy' of the Cape Colony. The overall policy remained in place for the remainder of the nineteenth century. Yet where did guns fit in? Were they commodities that, if exchanged and used, would tend to increase civilization? Or were they objects that would be turned against the project of civilization?29

There is also a direct answer to the question of whether guns were commodities and that is that as the nineteenth century ended and African men acquired more guns, especially from working on the Kimberley diamond fields, successive colonial governments began to impose restrictions or even ban their ownership by Africans. To fuel the present discussion concerning the amaMfengu and other 'frontier Africans' who allied with the British, it is important to begin by tracing the discourse of criminality which prompted the formation of policing and military units in the first place. To illustrate the historical importance of African collaboration in colonial wars, Elizabeth Elbourne's description of the parlous condition of even those Africans who lived on mission stations and were not easily drawn into military service, is apt:

If the rewards of colonial collaboration seemed less secure by the 1840s, despite the success of the Kat River settlement [a mission station], the costs of military service were starkly apparent. The Kat River settlers, for example, were conscripted into the colonial forces in 1835-36 and again in 1846-47. This was despite the fact that the Khoekhoe-staffed Cape Corps already made up the bulk of the troops stationed at the Cape Colony. First to be summoned and last to be released, the entire male population of Kat River between the ages of sixteen and sixty was called into service in the war of 1835-36.30

The Government's Army is Money

The Cape Colony's experience with criminality and policing the frontier should therefore be read as a precursor to the debates that take shape once Natal becomes a British colony. Another answer to Storey's question as to whether guns were commodities is found in the testimonies collected in the James Stuart Archive. Here the connection between government, the military and money is made explicit and slightly anachronistic.

Although he was intending to collect stories about the past, Stuart31 often prompted his informants to talk about their current predicaments; he labelled these 'grievances'. One of these informants, Mbovu ka Ndengezi, gave a pointed disquisition on the meaning of money and its connection to government. It is worth quoting at length:

Was it not right to keep money from natives? Money was brought by Europeans. We had none. Natives should not have been given money because they do not know its use. They should be paid in clothing and cattle. But coolies, Arabs, and Chinese understand money. Let contracts exist between them. What is wanted from us is money. After we have worked, the money we earn is taken from us in every way. Our needs are increased and we are pressed in every way. We then go out to work and wages are reduced. We have our own necessities to meet. We would be content without money. We will also work for hoes. Let pieces of paper be with Europeans…

Money causes crime, thefts etc. If there was no money with us nothing would be wanted of us. Our people cannot work; they have not been taught. The great thing wanted of us is money. Although natives cannot [work], are not used to work, they should work as far as they are able.

The Government built the country with money. Without money we would have become cannibals…

Government is expanding, every few years. The Government resembles Tshaka, for he never got tired. Its army is money.

…

'Natives will become criminals.'[italics in the original]32

The anachronistic link between the colonial government and the reign of Shaka, suggests a seamless transition from the military strategies and ambitions of the founder of the Zulu kingdom and the colonial government. However, other 'ambitions' are attributed to the state, namely, expansion and the spending of money. In Mbovu's mind these are all connected to the fact that money, like an army, marches tirelessly in the name of its commanders. These statements could be dismissed as figurative but they could also be taken seriously as pointing to the basic fact that colonial governments did spend money on both the expansion of state power and the expansion of military capacity. Moreover, Mbovu insightfully connects policing with the presence of money; he observes that without money there would be no crime and therefore no criminalisation of Africans. From his perspective, the 'Zulu Policeman' is exactly a functionary of the state because he is part of the army that is constituted with money.

This consumptive function of the state can also be discerned in the history of policing in Natal, where most of the photographs of Zulu policemen were taken. One of the most thorough sources on the establishment of policing as a profession is H.P. Holt's The Mounted Police of Natal.33 Not only does this book detail the history of Natal's first police force, it is also dedicated and prefaced by Major-General Sir J.G. Dartnell, K.C.B the founder of the policing corps. An excerpt from his preface gives us a sense of what considerations, compromises and exigencies influenced the creation of a colonial police unit. On the character and quality of colonists available for recruitment Major Dartnell writes:

I wanted to send home for men, but this the Government would not sanction, so I had to start recruiting amongst the flotsam and jetsam of the colony, and a very rough lot they proved to be, being principally old soldiers and sailors, transport riders, and social failures from home, etc.34

This corps of mounted police was established in 1873 and one of the first obstacles to overcome was the question of clothing and uniforms. And Major Dartnell writes:

The clothing was at first the same as that worn by the Frontier Armed and Mounted Police, viz., brown corduroy jacket and breeches, black leather boots coming nearly to the knee and buckled down the side, and a leather peaked cap with a white cover. It was a stinking uniform, however, which caused the men to be nicknamed 'The Snuffs',35 but anything in the shape of uniform was hard to get in the colony at the time. Afterwards, as more suitable uniform was obtained, the men began to put on a little 'side' when walking out, and the then Governor said to me one day: 'Your men swagger too much. We don't want swashbucklers.' To that I replied: 'If you knew the difficulty I have had to make them forget the name of "Snuffs" and instil a little swagger into them, you wouldn't wish to see it reduced.'

A little later on another Governor said, with reference to his orderly at Government House: 'I wish you wouldn't send a prince in disguise as my orderly, for he looks so spick and span that I am almost ashamed of my own get-up whenever I pass him.'

These two quotes point to the obvious relationship that exists between a uniform and behaviour - the 'flotsam and jetsam' of the colony is transformed into princely countenance by an appropriate and socially accepted uniform. Beyond this obvious 'functionalization'36 of the uniforms, as Roland Barthes would put it, the statement also tells us something about the pedigree of the Corps - it borrowed its uniform from the Frontier Armed and Mounted Police. In his preface, the Major-General describes how when appointed to his position he had requested permission to travel to the Cape Colony to 'learn something of police work, for they had had a mounted police force there for some few years'.37 This lineage of one colonial force copying or learning from another elucidates how notions of proper dress travelled from place to place. Or, expressed differently, Mbovu's assertions that the government's army is constituted of money are embodied in the 'swagger' that officers would adopt once they were dressed in their uniforms. Thus, the uniform can be understood as the embodiment of the government's ability to create and spend money.

The economic imperative of recruiting, clothing and paying policemen took on a different meaning with the large-scale urbanisation of the African population. From this perspective, these photographs could be understood to complement another kind of archive - namely, the archive of military dispatches and letters that defined why and how Zulu men were specifically recruited for military and policing service. For example, a letter from the Superintendent of Native Affairs, J. Marwick, stamped 30 November 1900, bemoans the fact that only 20 Africans are employed in policing the 'locations' of Pretoria. The letter is addressed to the Military Governor and states:

Having regard to the fact that there are - including Government labourers, about 7 000 working Natives alone in Pretoria - not to speak of the families in the Locations - I think the number of Native Police employed is not in excess of present requirements.

Native Constables - provided they be without local interests - are much more useful in policing people of their own colour than European police could be. In addition to keeping the Native population under proper control they have means of obtaining information which are not afforded to European Police.

The proposal to fix the strength of Native Police for Pretoria at 20 only should not be approved. Even in time of peace sixty, at the very least, would be required.

This letter shifts the attention away from the uniforms and dress of African policemen towards the 'function' they were meant to serve while in uniform. It clearly distinguishes the 'Native Police' from the 'European Police' by suggesting that the Native policeman has skills of investigation and interrogation that are not available to the European. Moreover, Superintendent Marwick accidentally points to one of the characteristics that was necessary for the making of the appropriate 'Native Constable': he was to 'be without local interests', meaning that he could not be from the urban location itself. He had to be from elsewhere. As the photographic archive attests, this elsewhere was Natal or Zululand.

The other function that is being defined here is that of 'proper control' - the Native policeman is not patrolling Pretoria's urban locations in order to 'keep the peace' or ensure the safety of the denizens. He is there to keep the 'population under proper control'. This placed the policeman in direct confrontation with urbanised Africans, especially the urban elite who chafed against the constant supervision and surveillance enacted by policemen. In 1911, Sol Plaatje38 published an article in the Pretoria News titled 'The Amalaita Bands: Some Criticism of the Native Police' in which he painted a different portrait of the character and behaviour of the Native Police:

For a picture of the average Zulu policeman at Johannesburg I would depict this; A creature, giant-like and large as to proportions, ferocious and forbidding of aspect, most callously brutal of action, and irredeemably ignorant. The knowledge that it is but necessary to call attention of the higher police officials to this matter to obtain remedy, and that there is no more kindly, courteous and humane gentleman anywhere than is Major Douglass, Deputy Commissioner, induces me to devote a short chapter to this subject in the sincere belief and hope that it will not be in vain.39

This caricature of the boorish and ignorant Zulu Policeman points to a literary history of these servicemen. The fact that Plaatje - a member of the nineteenth-century black elite and a man of letters - dedicated an article to the problem of urban criminal gangs (the Amalaita) and ineffectual policing by African policemen, suggests that there were many more such complaints. From Plaatje's perspective, the 'Native Police' were not actually keeping the black population under control (their key role, as defined by the 1900 letter) but were in fact negligent in their duty since they did not prevent or arrest the growth and violence of the Amalaita gangs. Still, beyond this grievance, another relationship is being defined here. Plaatje, and by implication other educated Africans, saw the Zulu policeman not as a compatriot or civil servant but as a nemesis. This antagonistic relationship between educated Africans and the ignoble Zulu policeman contradicts the swaggering image depicted by the founder of Natal's police force, since for the African elite the Zulu policeman was clumsy and incompetent, and certainly not a 'prince in disguise'. As a literary theme this antagonistic relationship offers us the opportunity to define the position of African policemen in the emerging class structure of urban South Africa. Moreover, it seems that the police force or forces also published their own journal or magazine from 1907 onwards. This publication was originally called Nongqai - the Zulu word for a 'night watchman' or security guard - and was then changed in 1979 to the Latin name Servamus (meaning 'to serve'). The fact that police officers founded their own journal, which wasn't principally concerned with policing and security issues but was, rather, a literary and 'human interest' magazine, suggests that while educated Africans had their own views and complaints about the police; the police in turn evolved their own literary response to the public's contempt.40

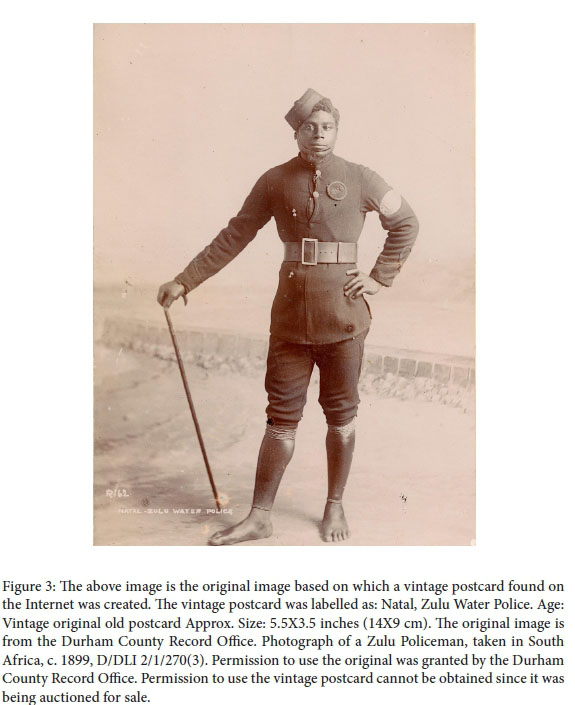

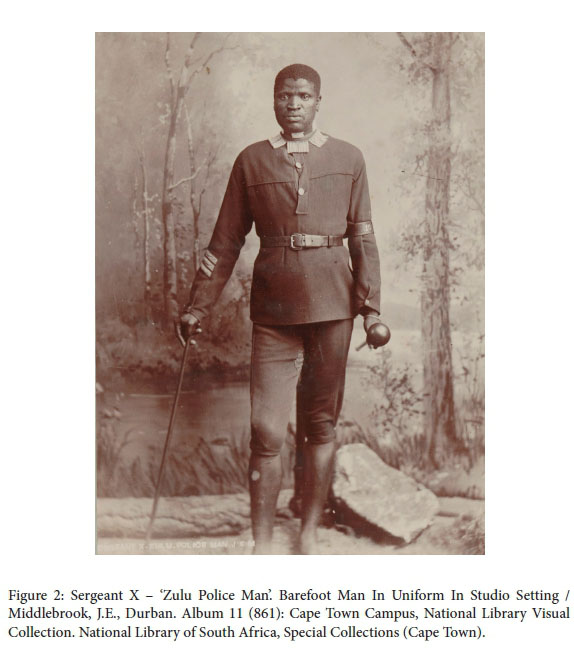

Although the gap that exists between the official version of what a policeman should have been and the African elite's contempt for Zulu policemen cannot be bridged, there are nonetheless reasons to think the photographer's camera offers us a third and alternative perspective. To illustrate the point about the different ways in which value was attached to photographs of Zulu policemen, two photographs will suffice as examples. The first photograph comes from a family album housed in the National Library of South Africa archives in Cape Town. The catalogue entry and description attached reads: '"Sgt X, Zulu Police Man" - Barefoot Man In Uniform In Studio Setting / Middlebrook, JE, Durban'. The fact that this is a studio photograph and was possibly taken with the consent and willingness of the subject does not diminish the fact that he is still anonymous and part of another person or family's photographic archive. By contrast, a second photograph exemplifies the commercialisation of the 'Zulu Policeman' as an exotic imperial subject. This photograph, which was being auctioned on a website, is mostly described by its dimensions: 'Age: Vintage original old postcard Approx. Size: 5.5 X 3.5 inches (14 X 9 cm)'. The most noticeable aspect of the photograph is the tint or archival hue which has turned what might otherwise have been just another photograph of an African man in uniform into a product that can be sold today as 'vintage'. These portraits of 'Zulu Native Policemen' confirm the physical stature of these men attesting to why members of the African elite were often so resentful of their presence and their seemingly arbitrary power. Even the literature on the history of dress and clothing in South Africa is biased towards the African elite since it often reinforces the idea that only the 'educated' wore Western clothing. Two concepts - 'status' and 'respectability' - form the foundation of Robert Ross's book Status and Respectability in the Cape Colony, 1750-1870: A Tragedy of Manners.41 Although it is a wide-ranging book covering the Dutch and British periods of rule at the Cape, Ross mostly tracks the ascendancy of mission-inspired notions of gentility and social and moral rectitude. He rarely touches upon the sartorial and moral codes of those who were not aspiring for incorporation into colonial society. The necessity to study the dress styles and choices of the 'underclasses' is, as already noted, eloquently justified in the work of Roland Barthes.42 However, Barthes offers his statements as a critique of the histories of dress in Europe and America. The histories of dress in Africa and other parts of the non-Western world are not necessarily included in his argument. The accepted assumption is that southern Africa's indigenous people wore, purchased and made Western-style clothes as part of the process of Westernisation and embourgeoisment.43 Johnny Fingo and the Zulu Policeman do not necessarily challenge this scholarly assumption; instead, they demonstrate that the use of the term embourgeoisment presupposes a single process or trajectory by which Africans acquired clothing and does not account for the sometimes innovative, creative, expressive and transgressive ways in which Africans clothed themselves.

Conclusion

In reading Johnny Fingo and the Zulu Policeman through the Red installation, it may be useful to focus on the 'uniform' as an assemblage with unique resonances in South Africa. As Mary Barker's epigraph on the 'cast-off clothes of all the armies of Europe' cues us, there was a popular cultural uptake of military uniforms that cannot be explained simply by reference to a specific war. More importantly, even in the realm of the sacred, the uniforms chosen by churches such as Isaiah Shembe's Nazarites exhibit strong military and colonial metaphor and imaging. As Papini notes, it is not just loss or victory that prompts an appropriation of military uniforms and insignia; it is the 'theatre of war' that supplies the images.44 In the case of the striking workers at the Mercedes-Benz plant, the construction of strike uniforms may be said to belong to this long line of 'uniformication' that has animated collective identities and quotidian activities alike. So whether it is 'Societies' (collective banking associations) or women's Umanyano (mothers' church unions), there exists a wealth of such fabricated identities. The tendency is to read such uniforms as forms of resistance. However, in the case of Johnny Fingo and the Zulu Policeman a concept such as resistance may not be sufficient to encapsulate the layered and contradictory valences of dress, attire, accessory and ammunition. The assumption tends to be that, because of their association with the colonial state's repressive tools, these policemen and mercenaries were either coerced or duped. The possibility that they were aware of their unsavoury function and therefore dressed accordingly, is not generally considered. In the same way that the striking workers who created the uniforms could be said to have been expressing the 'excess' they saw daily at the factory - that is, the availability of unused material - Johnny Fingo and the Zulu Policeman may symbolically represent the excesses of the colonial state. For one, when Mfengu levies used their pay to purchase decommissioned uniforms, they were at once signalling their 'equality' with their white officers, while at the same time mimicking or mocking the hierarchical command structure of the military. They were therefore resisting their subalternity (since they were not commonly recognised as 'soldiers'), while at the same time demonstrating their capacity to 'play the part' they were denied.

Although this article is concerned with Johnny Fingo, he is not an exception. There are multiple Johnny Fingoes whose visually documented presence could be dated as preceding the unification of South Africa as a country in 1910, and who could form part of a larger study of the material culture of South Africa. A focus on material culture opens up many possibilities notwithstanding an awareness that the history of photography, especially in the colonised world, is a well traversed area of study on its own. As James Ryan observes, in his book Picturing Empire: Photography and the Visualization of the British Empire, 'Britain's Empire, like much in the Victorian age, had the atmosphere and aesthetic charge of a grand spectacle'.45 By drawing such a link between the political, economic and expansionist ambitions of Empire with the problems of aesthetics and 'taste', Ryan makes it clear that the visual material produced during colonial times is as much a part of imperial history as it is African history. This article is an attempt to situate the 'Fingo' levies and photographs of Zulu policemen within the larger archive of imperial photography. It offers a nuanced exposition of how the 'grand spectacle' of the painting and photographs discussed was achieved through the convergence of state expenditure and the recording presence of the camera and/or the artist. However, unlike photographs of 'respectable' Africans - the Griqua Wedding Party on the cover of Robert Ross's Status and Respectability in the Cape Colony, 1750-1870, for example - the Zulu policeman (and his predecessors) is a figure of ambivalence rather than one that embodies the triumph of the civilising mission.

1 In the Oxford Essential Dictionary of the US Military, four definitions of the word 'levy' are provided. 'Levy' v. -ies, -ied, archaic enlist (someone) for military service; begin to wage (war); n. pl. -ies, an act of enlisting troops; (usually levies) a body of troops that have been enlisted: lightly armed local levies. 'levy.' In The Oxford Essential Dictionary of the US Military: Oxford University Press, 2001. http://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780199891580.001.0001/acref-9780199891580-e-4554, last accessed 9 November 2016.

2 M. Barker, A Year's Housekeeping in South Africa (London: Macmillan, 1877), 67. [ Links ]

3 T. Carlyle, Sartor Resartus (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1987), 34. [ Links ]

4 C. M. Geary, Images from Bamum: German Colonial Photography at the Court of King Njoya, Cameroon, West Africa, 1902-1915 (Washington, DC and London: Published for the National Museum of African Art by the Smithsonian Institution Press, 1988); [ Links ] E. Haney, Photography and Africa (London: Reaktion Books, 2010). [ Links ]

5 C. Hamilton, Terrific Majesty: The Powers of Shaka Zulu and the Limits of Historical Invention (Cape Town: David Philip, 1998). [ Links ]

6 M. R. Mahoney, The Other Zulus: The Spread of Zulu Ethnicity in Colonial South Africa (Durham & London: Duke University Press, 2012). [ Links ]

7 D. Cannadine, Ornamentalism: How the British Saw Their Empire (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002). [ Links ]

8 Simon Gush in collaboration with James Cairns, Red (film), 2014.

9 The Oxford English Dictionary describes a 'do-rag' in the following terms: 'Among African-Americans: a scarf or cloth worn on the head to protect a processed hairstyle; (more generally) any close-fitting cloth worn on the head' ('do-rag, n.'. OED Online. September 2016. Oxford University Press. http://www.oed.com/view/Entry/249907?redirectedFrom=do+rag, last accessed 10 November 2016). The concept of a 'do-rag' however precedes usage by African Americans since the Ethiopian Emperor Menelik II (1844-1913) was often photographed wearing a white cloth underneath a wide-brimmed hat.

10 W. Hartmann, J. Silvester and P. Hayes (eds), The Colonising Camera: Photographs in the Making of Namibian History (Cape Town & Athens: University of Cape Town Press & Ohio University Press, 1998); [ Links ] M. Stevenson and M. Graham-Stewart, Surviving the Lens: Photographic Studies of South and East African People, 1870-1920 (Vlaeberg, South Africa: Fernwood Press, 2001). [ Links ]

11 Historically, the 'Zulu' were 'late' ethnographic subjects. It was only in 1879 that the British Journal of Photography published its praise of the photographs of Zulu king Cetshwayo kaMpande as being superior to the illustrations that had sufficed up to that point. Editorial. 'Photographs of Cetewayo', The British Journal of Photography XXVI, 1017, 1879), 526-26. Additionally, a storekeeper was summoned and subpoenaed by the Lord Mayor of London for displaying photographs of Zulus, and the transcript of the trial testifies to the relative 'novelty' value of such photographs. Editorial. 'Photography in Court', The British Journal of Photography, XXVI, 1017, 1879, 521-23.; Editorial. 'The Lord Mayor And Mr. Alderman Nottage', The British Journal of Photography, XXVI, 1017, 1879, 538.

12 C. M. Geary, 'Old Pictures, New Approaches: Researching Historical Photographs', African Arts, 24, 4, 1991, 38. [ Links ]

13 P. S. Landau and D. D. Kaspin, eds., Images and Empires: Visuality in Colonial and Postcolonial Africa (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002); [ Links ] T. Barringer, G. Quilley, and D. Fordham, eds., Art and the British Empire (Manchester and New York: Manchester University Press, 2009); [ Links ] J. R. Ryan, Picturing Empire: Photography and the Visualization of the British Empire (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1997); [ Links ] Stevenson and Graham-Stewart, Surviving the Lens : Photographic Studies of South and East African People, 1870-1920; O. Enwezor, ed. The Short Century: Independence and Liberation Movements in Africa, 1945-1994 (New York and London: Prestel, 2001); [ Links ] O. Enwezor, ed. In/sight: African Photographers, 1940 to the Present (New York: Guggenheim Museum, 1996). [ Links ]

14 Even as late as the First World War, the African men who were recruited for the South African Native Labour Contingent (SANLC) were spoken about as 'Zulu'. See B. P. Willan, 'The South African Native Labour Contingent, 1916-1918,' The Journal of African History 19, 1, 1978, 64. [ Links ]

15 M. Godby, 'Ideas of "home" in South African landscape paintings by Thomas Bowler and Thomas Baines', Art and the British Empire, (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2007), 84-96. [ Links ]

16 A. Webster, 'Unmasking the Fingo: The War of 1835 Revisited', in C. Hamilton, The Mfecane Aftermath: Reconstructive Debates in Southern African History (Johannesburg & Pietermaritzburg: Witwatersrand University Press & University of Natal Press, 1995), 241-276. [ Links ]

17 J. Stone, 'Baines, Thomas', in D. Buisseret (ed), The Oxford Companion to World Exploration (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007), <http://www.oxfordreference.com/views/ENTRY.html?subview=Main&entry=t230.e0058>, last accessed 29 November 2016.

18 W. Benjamin et al., Selected Writings: Volume 2 (Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2005), 508. [ Links ]

19 Ryan, Picturing Empire, 16-17.

20 Ibid, 12.

21 J. B. Peires, The Dead Will Arise: Nongqawuse and the Great Xhosa Cattle-Killing Movement of 1856-7 (Johannesburg; Bloomington: Ravan Press; Indiana University Press, 1989), 11-12. [ Links ]

22 Although I have read Peires's The Dead Will Arise: Nongqawuse and the Great Xhosa Cattle-Killing Movement of 1856-7, it was only after reading J. Whyle's The Book of War (Auckland Park: Jacana Media, 2012), [ Links ] that I truly apprehended the sartorial language that suffused the memoirs of the British soldiers who fought in the colonial 'frontier wars'.

23 One of the definitions of the word 'Charlie' as given by the OED is: 'The name formerly given to a night-watchman. [The origin is unknown: some have conjectured 'because Charles I in 1640 extended and improved the watch system in the metropolis'.]' ('Charley | Charlie, n.'. OED Online. September 2012. Oxford University Press. http://www.oed.com/view/Entry/30754?redirectedFrom=Charlie, last accessed 6 November 2012).

24 W. R. King, Campaigning in Kaffirland; or, Scenes and Adventures in the Kaffir War of 1851-2 (London: Saunders and Otley, 1853), 101-2.

25 Ibid., 42.

26 The OED gives the following definition of Johnny: '…slang. A policeman. Also Johnny Darby, Johnny Hop.' ('Johnny | Johnnie, n.'. OED Online. September 2012. Oxford University Press. http://www.oed.com/view/Entry/101516?redirectedFrom=Johnny, last accessed 6 November 2012).

27 S. B. Lakeman, What I Saw in Kaffir-land (Edinburgh; London: W. Blackwood and Sons, 1880), 74.

28 Ibid., 75.

29 W. K. Storey, Guns, Race, and Power in Colonial South Africa (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008), 77.

30 E. Elbourne, Blood Ground: Colonialism, Missions, and the Contest for Christianity in the Cape Colony and Britain, 1799-1853 (Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press, 2002), 308.

31 James Stuart was born in 1868 in Pietermaritzburg. In 1881, he was sent to England, for his education. He returned to Natal in 1886, and after working in the post office in Pietermaritzburg, was appointed clerk to the resident magistrate of Eshowe in the recently annexed British colony of Zululand in 1888. Stuart became a magistrate in Zululand in 1895, and subsequently at various centres in Natal. In 1909, he was appointed Assistant Secretary for Native Affairs, the second highest post in the colony's Native Affairs Department. In 1912, for reasons that are not clear, he retired at the age of 44, and returned to Natal. In 1922, for reasons that again are not clear, he left Natal and settled in London where he lived until his death in 1942. J. Wright, 'Making the James Stuart Archive', History in Africa, 23, 1996, 334.

32 C. de B. Webb and J. B. Wright, The James Stuart Archive Of Recorded Oral Evidence Relating to the History of the Zulu and Neighbouring Peoples. Volume Three, 5 vols., vol. 3 (Pietermaritzburg & Durban: University of Natal Press & Killie Campbell Africana Library, 1982), 29.

33 H. P Holt, The Mounted Police of Natal (London: Bibliolife [John Murray], 2009).

34 Ibid., viii.

35 One of the meanings of the word snuff is: 'To detect, perceive, or anticipate, by inhaling the odour of' (OED). The pun being made here is that the uniform was so smelly that the police could be snuffed from a distance.

36 In his influential and seminal book, The Language of Fashion, Roland Barthes makes the following observation about clothing: 'Outside of the leisured classes, dress is never linked to the work experienced by the wearer: the whole problem of how clothes are functionalized is ignored.' Roland Barthes, The Language of Fashion, ed. A. Stafford and M. Carter, trans. A. Stafford (Oxford & New York: Berg, 2006), 5.

37 Holt, The Mounted Police of Natal, xi-xii.

38 Solomon Plaatje (1876-1932) was a journalist, linguist, author, and early member of the African National Congress. He became a government clerk and an interpreter; and spoke several vernacular languages as well as English, Dutch, Afrikaans, and German. During the South African War (1899-1902) he worked for the British, and his vivid diary of the Siege of Mafeking, written in a school exercise book, was discovered many years after his death. He founded several newspapers that defended African rights against white rule. His book, Native Life in South Africa (1916), appealed for British help against South African government policies. In 1919, he was a member of a South African Native National Congress delegation to London that failed to get African interests discussed at the Versailles Peace Conference. Plaatje wrote poetry and translated several Shakespeare plays into Tswana. He also wrote Mhudi (1930), one of the first novels to be written by an African.

39 S. T. Plaatje, 'The Amalaita Bands: Some Criticism of the Native Police,' English in Africa, 3, 2, 1976, 59.

40 For examples of some of the articles published in Nongqai see: http://www.esaach.org.za/index.php?title=Zulu_Literature, last accessed 3 December 2016.

41 R. Ross, Status and Respectability in the Cape Colony, 1750-1870: A Tragedy of Manners (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999).

42 Barthes, The Language of Fashion, 5.

43 J. L. Comaroff and J. Comaroff, Of Revelation and Revolution: The Dialectics of Modernity on a South African Frontier, Vol. 2 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1997), 271.

44 R. Papini, 'The Nazareth Scotch: Dance Uniform as Admonitory Infrapolitics for an Eikonic Zion City in Early Union Natal.' Southern African Humanities, 14, December 2002, 90.

45 Ryan, Picturing Empire, 15.