Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Kronos

On-line version ISSN 2309-9585

Print version ISSN 0259-0190

Kronos vol.42 n.1 Cape Town Nov. 2016

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2309-9585/2016/v42a11

ARTICLES

Blood Lines: Cecil the Lion, Mandela, and art in history

Paul Vig

Department of History, University of Minnesota

ABSTRACT

This article takes three events as a cue to examine the connections between race and development in the history of hunting. First, the killing of Cecil the lion in July 2015 by Walter Palmer. Second, Nelson Mandela's hunting trip in 1991 that was reported on under the title 'Mandela Goes Green'. Thirdly, the art installation and film Red that explores the building of a red Mercedes for Nelson Mandela in 1991. Serendipitously, these three events come together in a way that enables a look at how art, technology and history can be thought differently. The workshop 'Red Assembly' in East London and the careful thought given to a retelling of the building of Mandela's red Mercedes collides with the hyper-technological online protest and commentary in response to the killing of Cecil. Their near simultaneity, each referencing Mandela in a different way, draws attention to the continuing concerns over labour and race in a post-apartheid South Africa that continues to look to Mandela as a figure of positive change. The contentious debates around the wildcat strike at the East London Mercedes-Benz factory in 1991 as well as the killing of Cecil 25 years later illuminate how claims to development and progress are caught up in globally connected flows of capital and material goods that persist in the tendency to view the figure of the black body only as labour, despite protests that point to the need for more critical thought. At the same time, these contentious debates and a reading of the installation Red through the 'Red Assembly' workshop reflect the anxieties of writing history in a post-apartheid South Africa that struggles to reinsert the human into understandings of the past without falling prey to the temptation of producing history as an uncritical act of recovery or a celebration agency.

To be uprooted awakens reason by suggesting comparison - always a good start.

Regis Debray

To re-write South African racial and capitalist modernity from within and through the sign - the real historical sign of this black/migrant worker - as opposed to seeking alternative, vernacular and multiple modernities that equally erase these working-class histories and struggles, remains a profound and on-going challenge.

Gary Minkley

Three Events

Cecil

On 1 July 2015 a white hunter from Minnesota, Walter Palmer, armed with a crossbow, shot and wounded Cecil, a lion in Zimbabwe. After that, Palmer and his hunting party tracked him for a day, shot him with a gun, skinned and beheaded him.1 News of Cecil's death hit media outlets in the last week of July. The Star Tribune reported that Palmer thought the hunt was legal;2 though, as details of the hunt emerged, potential poaching charges were laid against Palmer, Theo Bronkhorst (the professional hunter) and Honest Trymore Ndlovu (the land owner). The charges included lack of proper permits, luring Cecil out of Hwange National Park, and attempts to destroy Cecil's tracking collar.3 Trackers found Cecil's carcass, partly eaten and decaying in the veld, days later.4 During August Cecil-related articles, posts, comments and responses proliferated across social media, primarily on Facebook. These reactions on social media multiplied at a global level, demanding bans on trophy hunting, with threats up to and including death levelled at Palmer, Bronkhorst and Ndlovu. Conversely, there were just as many responses in support of big game hunting in Africa and its claims of supporting conservation and social development.

Mandela's Hunt

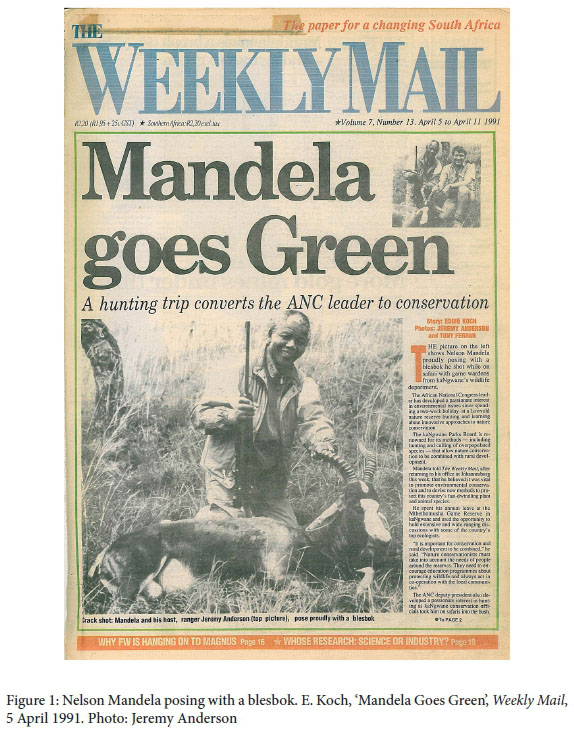

The conservative columnist Andre Walker, responding to Cecil in defence of trophy hunting in Africa,5 returned to another article, this one from 5 April 1991 in the Weekly Mail, titled 'Mandela Goes Green'.6 In that article Eddie Koch reported on Nelson Mandela's hunting trip at Mthethomusha Game Reserve, overseen by the kaNgwane Parks Board in partnership with the Mpakeni community where revenue from hunting is split between kaNgwane Parks and Mpakeni for development projects. Mandela's two-week safari included the hunting of an impala and a blesbok, as well as several meetings with farm owners and park board members to discuss and encourage the linking of conservation and local community development.7 The standard photo of the hunter and his kill, in this case Mandela with his rifle and blesbok, accompanied the article. Citing both Mandela and the park board members, the article noted how hunting was seen as crucial to the anticipated new South Africa for its role in linking rural development and social upliftment through wildlife management and culling, as well as for its contribution to conservation and anti-poaching efforts.8

Red

Red 9 is an art installation by Simon Gush (with collaborators James Cairns and Mokotjo Mohulo) inspired by the production of a red Mercedes-Benz for Nelson Mandela after his release from prison in 1990. The red car was built by the autoworkers at the Mercedes factory in East London, on their own donated time. Later that year, those same workers also held a nine-week wildcat strike protesting against the centralised bargaining negotiations. Gush's work displayed a disassembled (and reimagined, reassembled) replica of the red Mercedes, and of the makeshift beds from the factory during the strike, and the worker's uniforms. Red the artwork was accompanied by the black and white film Red10 that juxtaposed various narratives of the making of the red Mercedes and the strikes alongside still images of the Mercedes-Benz factory and East London. It presented the dismembered components of a replica red Mercedes as Mandela's car, alongside representations of uniforms, fabric and materials from the factory where the vehicle was assembled. At the end of August 2015, 'Red Assembly' brought Gush's work back to East London in a two-day workshop with Gush and Cairns centred on discussion and contemplation of the relationships between cinematic representation, narrative, sound(track), history, factory, assembly and landscape.

Serendipity and History

Sometimes things come together to 'uproot', as Debray says,11 and prompt important comparisons. I spent the month of August 2015 in the Waterberg district of Limpopo, roughly a day's drive from Antoinette farm,12 next to Hwange National Park in Zimbabwe, where Cecil was killed. During those weeks I was working to build a network of game farm owners, professional hunters and hunting farm employees for future research in the area. Cecil was the hot topic of conversation and, being a white American from Minnesota myself, everyone I encountered wanted to discuss the events. In the Waterberg, where private hunting farms dominate much of the landscape, the primary concern after Cecil's death was the potential economic fallout for the hunting industry. Any actions taken by countries or companies in response to protestors calling for bans on lion hunting, big game hunting, and the transport of hunting trophies could have dramatic consequences for the viability of farms in the area.13

On the heels of the killing of Cecil and my time in the Waterberg, I attended the 'Red Assembly' workshop, convened importantly in East London. Much like the Waterberg, East London and the Eastern Cape are sites on the margins of South Africa with histories of long-contested labour in the factories as well as over wildlife conservation in Southern and South Africa. While terms like 'margin', 'frontier' and 'border' carry their own weight, 'Red Assembly' here marked a poignant spatial connection between such contested histories and the reactions to Cecil's death, despite his killing taking place in south-eastern Zimbabwe. In the Waterberg I had been viewing old black and white photographs of hunts on farms in the bushveld from the early twentieth century. I was present during a few hunts and saw the blood on the veld, and on the workshop floor where the animals were field dressed. These images came flooding back as I made my way through the Red installation, as I watched the film again, as presentations and conversations throughout the workshop proceeded. This prompted a number of what perhaps otherwise might seem like unrelated connections: between a red Mercedes-Benz and a lion (as trophies), between a wild 'cat' strike on a factory floor and online protests over the killing of the wild cat Cecil (protest politics, politics of protest), between the red blood on the shop floor and the lion's red blood on the veld (blood/violence), between Mandela-and-the-car and Mandela-and-the-hunt (politics).

These links, despite a certain sense of happenstance and seemingly making somewhat playful connections, in fact mark a more serious coming together of contingency and conjuncture, of flows of global cultural, material, financial and epistemological capital, as well of questions about the nature of the relational to history. Similarities between the Waterberg and East London expose the farm and factory as sites of global industry, drawn together not just by media and art, but also by the movement of people, goods and services. In the case of Cecil, social media technology collapses various sites - the hunting farm and the various protester locations - into the screen and the newsfeed. This is an intensifying connection of information and events, yet it is also evidence of a simultaneously physical disjuncture from engaging person to person, markedly different from the door-to-door engagement discussed by workers in the film when negotiating the strike and debating collective bargaining. So, there is at once a continuity of global technological production sites and a shift in the ability and nature of a worker or observer to protest and discuss an event. The complex responses in the public sphere to the violence regarding the hunting of animals and the associated threats to hunt down the alleged 'poachers' serve as an unnerving reminder that the hunting of animals and the hunting of humans are not as clearly separated from one another as we may want to think.

Hunting has a long history of association as an elite sport. From a US or European perspective, this goes back to royal and landed classes, whose control of land and wealth afforded the luxury of hunting for sport while simultaneously excluding various indigenous people in the colonies from the spoils of the land and forest. In Africa, many social histories have outlined precolonial hunting practices, where often those who hunt hold a particular elevated status. The long history of hunting that covers the twentieth century in southern Africa is an entanglement of encounters between European colonial hunting and African hunting, one marked principally as rural. With the emerging efficiency of big game hunting as a global industry, game farms in South Africa have become sites of production for game and hunts. A historical look at the operation of these farms points to the continued elite status of the farm owners and hunters, most of whom in South Africa remain white while the labour on the farms are still primarily black. This inequality along racial lines remains sharp within a region like the Waterberg, despite the globally connected hunting industry that can constrain and shape localities such as the Waterberg irrespective of racial differences.14 Small numerical shifts in ownership along racial lines are beginning to take place, though the increase in black ownership of private game farms is confined to a wealthy elite class. As finance capital on these farms increases and accumulates, the gap between rich farm owners and hunters on the one hand, and the farm labourers (white and black) on the other, becomes more pronounced, as does the attending racialisation of the game farm landscape.

The epigraph from Gary Minkley above15 comes from a piece commenting on the contributions of Martin Legassick's work to South African history. Minkley quotes Legassick from 1974,

the structures of South Africa sustain a situation in which it is whites (though not all whites) who are the accumulators of capital, the wealthy, and the powerful, while the majority of blacks (though not all blacks) are the unemployed, the ultra-exploited, the poor and the powerless. The existence of, or potential of percentage reform is less relevant than analyzing the conditions for redressing the situation.16

While Legassick's call for analysing the conditions for redress were taken up in the mode of social history, Minkley's epigraph emphasises that the urgent historical questions of the post-apartheid are not found in alternative social histories but through a critical interrogation of the historical sign of the black migrant worker. Here the 'migrant worker' is marked as urban and industrial. A counter (but not binary) historical sign is that of the rural farm worker. Overwhelmingly black, living on or near the farms they work at, these labourers are the operators of the hunting farm, obscured by the keywords - development, community engagement, sustainability, conservation, preservation - of a global hunting industry that continues to find profit and pastime in a 'wild' African landscape. In the online responses to the killing of Cecil, attention was paid only to Palmer (international hunter), Bronkhorst (professional hunting guide) and Ndlovu (farm owner). Ndlovu, as a black farm owner, signals two important points. Firstly, Ndlovu is Zimbabwean and land ownership and land reform in Zimbabwe has its own set of concerns and provocations that cannot be addressed here. However, it must be noted that Ndlovu seemingly acquired Antoinette Farm through the Fast Track Land Resettlement Programme via his political connections as an elite member of ZANU-PF.17 Secondly, his name - Honest Trymore Ndlovu (elephant) - is revealing in that it marks the social and political dynamics of the desire for a trusted, disciplined neoliberal black African.18 These dynamics are closely tied to the wealth and power needed to access the ownership circles of game farming. Additionally, it is important to note how race is a factor in land ownership, for Ndlovu gets erased in the social media debates around hunting, race and Cecil.19 Until recently the production of the hunting farm and its labour has remained unexplored. When alluded to, this labour and production has often been limited to a discussion of race through the broad keywords and categories above. What Cecil/Red/Mandela enables is a look at the continuity, and the continued urgency, of the interplay between race and class, as well as how their interaction intensified with a simultaneous distancing and distraction with the rise of social media as a primary medium for transmission of ideas about the world.

As Qadri Ismail argues, we need to question the desire for information from history, because history emerges problematically as a discipline through categories of modernity that we are conscripted into - a colonial ordering of notions of time, space, past, race, gender, class.20 Yet Ismail's critique of history does not call for the discipline to be disposed of; indeed, he suggests that history is 'not just unavoidable, but necessary'.21 This need for history (and more of it) comes with a caution, an insistence that alternative histories, additions of new categories of 'history from below' along the lines suggested by Minkley, are insufficient.22 A proliferation like this of historical work falls back into an identity politics that leaves the categories of historical production unexamined and thus likely to repeat the work of such politics. These histories, according to John Mowitt, become merely 'a liberalism content to sacrifice emancipation to recognition ... utterly unwilling to think through the anxiety that attends its organizing concept.'23 Emancipation here is not another alternative history but a practice of exposing the seams along which history is produced, its modes of production.24

The coming together of Cecil/Red/Mandela enables a reflexive look at the production and retrieval of information through the 'old' ways of photography, film and narrative, as well as the 'new' ways of social media and information technology. In both we see claims to authoritative knowing about events - in this case, those of Cecil/Red/Mandela - claims that remain valid in the eyes of those making them. This acknowledgement of the validity of claims is productive for thinking history differently, as Ismail argues via Shahid Amin, because it 'refuses, that is, to be judgmental, to homogenize; he respects the specificity, the heterogeneity, the singularity of these accounts.'25 The assertion of validity of opposing opinions, something not seen in the vitriol produced in the aftermath of Cecil, is the work that Red does by leaving the viewer undecided, both in the film and the surrounding artwork, about the ultimate consequences of the red Mercedes and the wildcat strike. It practises a critique of history through answering the call for a more critical history. Cecil/Red/Mandela follows this critique by exposing the underlying structures of global economies that are obscured and go unexamined in a digital world of protest that, while calling attention to various sites of concern around the world, struggles to go deeper than naming and shaming.

In particular, Cecil/Red/Mandela raises questions about how race is structured and contested in the modern technologies of art, hunting and social media, as well as how historians, artists, hunters, farmers and labourers come together, become assembled, in a history of hunting. This rethinking remains urgently necessary in a new South Africa where the violence of imperialism and the systems of apartheid continue to operate, in many cases more efficiently in the production of cars and lions, if less obviously, under an African National Congress (ANC) government that still looks to the idea(l) of Mandela for continued social and political change.

Two central points of concern emerge from a critical look at Cecil/Red/Mandela. One is the eliding of the racial formations that continue to determine the politics of hunting in Africa in global and national discussions. The other is a move toward protecting the privileges of international hunting of big game at the local level through renewed claims to the development practices and goals that govern discussions about private game farming in South Africa, and that organise land, labor, investment and social development programmes. Both the practices of hunting and responses to events like Cecil's killing call attention to the production of hunting as a practice of wilderness, ecology and wildlife conservation, a discourse and strategy that is marked by distractions from a necessary politics of change.

Art, Technology and the Hunt

If art challenges perception by inviting a different type of reading, and post-apartheid predicaments and disappointments demand a careful reconsideration of the possibilities of change and the weight of history, then what might such a reading of Cecil/Red/Mandela enable? Nelson Mandela - as the recipient of the gift of the red Mercedes and as the symbolic representative, the sign, of the transformation of hunting and conservation - is the figure that makes the link between Red and hunting. Such a reading invites careful attention to the interplay between serendipity and contingency, between event and meaning making, and between claims to transformation and post-apartheid realities.

Red invites viewers to contemplate and juxtapose, on the one hand through cinematic representation, narrative, sound(track), history, factory, assembly and landscape. On the other, Red also presents the dismembered components of a replica red Mercedes as Mandela's Mercedes, alongside representations of uniforms, fabric and materials from the factory where the vehicle was assembled. With my time on Waterberg game farms fresh in my mind, the car doors hanging on the gallery walls seemed displayed as trophies. The bonnet presented on the gallery entrance floor was reminiscent of a lion skin rug in the entrance of a game lodge. The carcass of the car's body outside on a rack hung as a carcass of a trophy animal hangs in the shop for skinning and field dressing.26 Here Gush's work transforms the red Mercedes into a sign, one that makes the viewer question the car, its production, its dismemberment, its history, the space it inhabited and the journey that brought it there. This disturbs the comfortable and safe narrative of every other ordinary Mercedes-Benz driving down the streets of East London, or lined up on the docks in the film awaiting shipment across the seas. In a way, Cecil's death and the response to it made similar demands of lion hunting for those who encountered it.

The juxtaposition of the dismembered, yet 'assembled', red Mercedes with a black and white film titled Red emphasises the importance of the colour red as a symbol of the blood spilt in the fight for liberation. While the colour red was initially chosen to contrast the black cars driven by politicians of the apartheid regime, red came to signify blood in the retelling of the making of the car. In the opening minutes of the film Thembalethu Fikizolo recalls the actual blood on the shop floor during the strike. Later in the film it is noted that Mandela, receiving the car from Philip Groom on behalf of the workers and the community, recalled the blood spilled in the struggle. These exchanges are part of the interview with Groom voiced over black and white still shots of the stadium where the presentation and speech took place. It is, in Red, an empty stadium landscape, though images of full stadium rallies quickly come to mind accentuating the emptiness, with resonances of the disappointments of the present as the time after apartheid, and of past promises and possibilities. Likewise, images of Palmer posing with Cecil placed alongside Mandela and his blesbok, and alongside 'empty' unpeopled scenes of the veld on hunting lodge websites, accentuate the continued violence and blood spilt in creating and maintaining wild Africa. These classic images move beyond just the hunter, his gun and the dead animal. They expose the link between aesthetics and development, an 'aesthetics of development', that is found in the production and marketing of the game farm.27 The materiality of taxidermy in the hunting trophy points to the materiality of the logics of production that lead to the animal being displayed on a wall, sometimes within the lodge on the very farm it was killed on.

Mandela-and-the-hunt and Mandela-and-the-car

In 1991, within a year of receiving the red Mercedes from the factory workers in East London, Mandela went hunting. A large photograph - a black and white photograph, like those in the film Red - accompanied the 'Mandela goes Green' story in the Weekly Mail and is reminiscent of colonial hunting images.28 It places Mandela in the literal and figurative position of the 'great white hunter'.29

Mandela noted that rural people had, in the past, frequently been dispossessed of their land so that conservation areas could be created. Many saw reserves and the game wardens who run them as an integral part of apartheid's oppressive institutions.30

The field vest, a 'hunter's uniform', frames Mandela in such a way that black South Africans can see themselves in his position, in a future where they hold more social, economic and political control, benefiting from a purportedly transformed conservation economy that would right the wrongs of colonialism and apartheid.

Simultaneously, white farm owners saw in Mandela's hunt a validation of their claims to conservation practices through hunting, land management and wildlife economy. The use of the word 'converts' to describe the conceptual action of Mandela turning to conservation through his hunting experience adds an evangelical tone to the politics of conservation. This emphasises the importance of a particular type of conservation, with hunting as a key element, rooted in western colonial understandings of conservation. It also suggests a spiritual return to primeval wild Africa - a romantic aesthetic that seems immortal in its continuous rebirth.31 Further, the claims of (desire for) access to the privilege of hunting are similar to the claims of (desire for) access to a luxury vehicle like Mercedes, previously only accessible by whites. This privilege, embedded in a history of whites excluding Africans from the hunt and the land (except as labour), and the necessary creation of the category of 'poachers' to enforce that exclusion, is not unlike the creation of 'terrorists' to render freedom fighters like Mandela as outside politics and therefore illegitimate. The image of Mandela and his kill, perhaps unwittingly foreshadows the continued white ownership and control of conservation practices, perpetuated partly by the ANC's promoting of liberal policies of economics and development. This continuation of controlled access for black South Africans to hunting only as labourers remains despite the figure of Mandela implying a dramatic shift, a true transformation, in access to the hunting industry along racial lines.32

The content of the article reaffirms this reading of the photograph, noting that Mandela encouraged the linking of conservation and local community development, citing 'fast-dwindling plant and animal species' and adding fuel to the degradation argument that underpins much of the conservation narrative in southern Africa.33 The kaNgwane Parks Board saw hunting as crucial to rural development and social upliftment through wildlife management and culling. Mthethomusha Game Reserve, where Mandela's hunt took place, through its partnership with Mpakeni, splits its revenue from hunting between kaNgwane Parks and development projects for the Mpakeni community.34 It is important to note the article's emphasis on decreased poaching in reserves associated with community support for hunting. This implies that black Africans are poachers until they can be educated about the proper way to use the economic value of wildlife - through managed big game hunting. By implication, Mandela the formerly imprisoned ANC 'terrorist' was being normalised, domesticated to the modes of hunting conservation.

Mandela was perceived as properly 'trained'. A remark about Mandela's 'perfect hunter's shot' placed particular emphasis on his marksmanship.35 Such a comment reinforces the need for proficiency in the technologies and practices of hunting in order for a hunt to be carried out properly. The technical skills of tracking and marksmanship, along with ecological land management and understanding of liberal development economics and military security protocol, are essential if hunting, as conservation, is to continue to be successful in the new South Africa to come that the Koch article emphasised. Again, the farm is a site for the operations of a global hunting industry. These proficiencies now ostensibly replace race, and perhaps are marked more visibly by class, as that which differentiates, disassembles and excludes. The article claims that 'Mandela's new enthusiasm for green issues puts the ANC in the forefront of efforts to include environmental rehabilitation and protection in the building of a new South Africa.' This places Mandela and the ANC (the new South Africa of the early 1990s) in the position of deferring racial politics and transformation in favour of promoting hunting and the technologies of hunting, rooted in apartheid and colonial governance, as agents of social, environmental and economic change. Again, to quote the article at length,

John Hanks, chief executive of the Southern African Nature Foundation, said it was vital that new governments in South Africa place environmental issues on the top of their agendas. 'I was delighted to hear of Mr. Mandela's commitment to humanising conservation and of his support for the principle of consulting local people in the development of conservation projects,' said Hanks.

'More importantly, he has realised the value of ensuring that the benefits of these projects go back to local communities.' Ferrar said his meeting with Mandela had created a useful link between established conservation bodies and the ANC and hoped that it would be the first in a series of consultations between green groups and political organisations.36

'Humanising conservation' and a 'useful link between established conservation bodies and the ANC': on the one hand this language acknowledges the need for local community involvement and development, while on the other it reinforces the practices of conservation established and solidified under an apartheid regime of 'separate development' that put the land ownership and wealth of the hunting industry in the hands of whites, operated by black labour. It would be interesting to know whether the workers at Mthethomusha Game Reserve looked upon Mandela's hunt as a 'labour of love' in the same way as the factory workers in East London viewed the making of Mandela's car.

Mandela's participation in this hunt linked the heroics of the ANC, its resistance struggle (so carefully documented and yet called into question in both the film and the installation Red) and the anticipated post-apartheid, to the embedded structures of white-owned and operated national and private hunting conservation practices. What could have been a project of institutional reform, with Mandela directly addressing the legacies of apartheid and colonialism cemented in hunting, has instead become merely a project of racial numerical redress37 through the training of non-white managers and operators of game farms.38

The fact that factory workers in East London worked overtime without pay to produce the red Mercedes - not jeopardising the regular production line - is a similar form of low-cost redress rather than transformation. It did not challenge the operations of the global Mercedes-Benz system at their factory site. When the workers demanded real, not just symbolic, transformation through strikes, they were quickly called to order and ultimately dismissed. They were turned into 'poachers' of corporate time, money and resources.

The difficulty in addressing the processes that repeat this deferral of real change lay in the troubling legacies of the long history of the global networks, disciplinary and economic, that now control the hunting industry in Africa.39 The cultural aspects of hunting practices are so entrenched in colonial European and apartheid Afrikaner ritual and land use that the return to hunting 'by Africans' in an attempted process of precolonial cultural recovery is not possible.40 Rather, in a post-apartheid South Africa, the attempt is being made at racial redress in the business practices of hunting while maintaining the racial structures of power and practice that mark the economic divide in hunting. The hunting farm remains a site of global industry, dominated by highly financed and capitalised organisations and individuals, despite the beginnings of a move to racial redress. Importantly, from the perspective of international marketing, in an African hunt for international hunters41 the claim of local community benefit from a white-owned game farm offers the allure of 'authentic' African hunting experience, tied up in the 'myth of wild Africa'.42 Such perceived authenticity perpetuates racial stereotypes of the position of the black body in the landscape of wild Africa and often comes with the expectation that the business and financial ends of a hunt will still be safe, secure, trustworthy and convenient by virtue of being operated by a white South African. Racial homogeneity provides comfort in the wilds of black Africa. Mandela-the-hunter of 1991, as a black African, provided the authenticity of an 'African' hunting experience in the veld. Mandela the nonracial politician provides the assurance that hunting will still be white-operated, because the current systems of linking hunting to conservation, in the hands of white farmers, are sound and will be maintained. Clues to the disappointments of the post-apartheid, and with the ANC, can be found in the perpetuation of these technologies and practices of hunting through the production of the game farm and the training of black and white bodies.

The accumulation of knowing through 'training' in hunting practices has produced a particular normative understanding of hunting. At the same time this deflects from the racial formations that hunting practices have established and enabled - reflected in the aesthetic of the 'great white hunter'.43 The notion of training, as in habituation, repetition, routine, factory production line, returns in the figure of a green Mandela, as it does with Mandela's red Mercedes. This aesthetic is composed of a particular set of practices and work that make visible, and draw the attention of white populations (in southern Africa, Europe, and the United States) to the encounter with the African landscape. The landscape (in physical geological terms and as an artistic, especially photographic, genre) is another evocative point of connection between the work and the workers of the installation Red, the 'Red Assembly' workshop, and hunting. This landscape features in an aesthetics of hunting just as it does in the visual narrative that Gush creates. The production of this aesthetic and the relationship between its particularity and its 'ordinaryish-ness'44 is meant to speak to a public as if to say, 'Oh, I know a place like this.' This knowing, and the creation of familiarity, or ordinariness, in an arguably foreign or exotic landscape and setting, is coded 'white' and produced, factory-like, in the space of the private game farm through its images, representations, practices and discourses.

The Production of the Ordinary Technologies of a Hunt

Planning a hunt entails selecting a hunting farm, usually done by searching the Internet, perhaps after having been at a hunting expo. What is being marketed here is an 'aesthetic of development' that links hunting, conservation and development - with a particular space for the black body - for consumption by primarily white hunters. Photographs and information that emphasise the farm's ability to deliver the components of an authentic hunt populate outfitting websites. Images of an unpeopled bushveld, often at sunrise or sunset, framed around a lapa with sundowners, or game at a watering hole near the lodge, dominate homepages. Various tabs will highlight other aspects of the farm and hunt. 'Accommodation' links include images of rooms decorated with animal skins, art (taxidermy trophies, heirloom rifles, masks, photographs of hunters posing with kills) and cuisine (bobotie, pap, boerewoers, braai). Artists and cooks produce the 'local or African' art and food that adorns walls and tables, though they themselves are rarely named, nor do they feature in the images. The tabs linked to hunting services include an assortment of game to be pursued from blinds (hides usually at watering holes), tracking (capture and kill for a wounded animal like Cecil), skinning (beheading), and documenting (photography, narrative and taxidermy). Transport information covers not just help with airline recommendations and proper paperwork - for bringing weapons into the country and trophies out of it - but also getting to and from the farm, as well as around the farm itself.45 Transport on the farm uses the ubiquitous 4x4, mostly viewed as the Land Rover Defender even if other bakkie models also proliferate.46 The exhibition and (re)telling of the hunt through all these images and narratives of satisfied customers serve to market a particular African hunting safari experience.

Again, most of these images are unpeopled. Recall Mandela's comments about his concern over the removal of African communities from land to make space for reserves or private white farms. Those people return as labour to enable a hunt (critical for the hunting economy) but not as part of its aesthetic imagery or in positions of power or control. Training in the use and consumption of technologies of hunting establishes a normative history of race relations in hunting in what is marked white and what is marked black. If black Africans do enter into these images, it is as drivers behind the wheel of the Defender or positioned behind the hunter with his gun. The white farm owner enters the images alongside the white hunter, also holding a gun, or seated around the braai with the hunting party (the cooks and servers absent). This entails an act of erasure, or particular position given, to the black African body in hunting that is always already marked by, resonant with, and connected to colonial governance, the apartheid state, and their structures and archives. The parallel to the factory worker is striking: despite the anti-apartheid struggle for freedom and sovereignty, the black African body on the rural game farm, like the black African body on the (urban) shop floor, is always already modern and conscripted into systems like the factory, the assembly line, discipline and governance.47 The primarily unpeopled images of the bushveld are evocative and troubling in a similar way to how Gush troubled the images of East London, the strike and the red Mercedes through the unpeopled still shots of the factory and landscapes placed alongside the physical and audible presence of the workers' interviews in the film.

Harry Wels uses the term the 'logic of the camp' to analyse the landscapes of private game conservancies not as wilderness but as spaces marked by militarised control of inclusion and exclusion, order and disorder, and conservator and poacher.48 The practice of exclusion through the boundaries of the fence, and the insider-outsider-intruder dynamics of security, both extended from and helped to legitimate conservation and, I would add, hunting efforts. In the production of the hunting farm, the technologies of the hunt become the drivers of movement (of people, technology and animals) across the 'hard edge'49 of the fence boundary. Through the training involved, which has been ongoing since the hunting expeditions of the nineteenth century (and their narration),50 these technologies have become normalised. This is not just a training of black bodies to fit a particular role in the wilderness aesthetic of the hunt but a matter of how to keep white control in these spaces.

Wels includes a series of photos of the training for Zulu game guards.51 One in particular shows three young white boys in the background, sitting on the wall watching the scene.52 There is a double training that takes place here. One is covered by Wels when he discusses the militarising of Zulu game guards and the farm fence as border. The other is of the young white boys watching and, by inference, learning how to train Zulu men to be a particular type of body on the landscape, the game guard under supervision of white management - the proper demarcation of white and black, civilised and savage. This is a different kind of aesthetic, a darker one, that shows the murkiness behind the prettier images of hunting on the veld. The reading of this photograph draws attention to the absence of the black body in the imagery of the hunting farm website. This is not just a recognition that black bodies remain in the role of worker versus the white boys who grow up to own and manage the hunting farm; it illustrates the active role that such training programmes play in learning, and thus repeating, logics of racial interaction in hunting. International hunters arriving for safari to consume the commodity of a hunt in the veld have these logics reinforced as they participate in the hunt. There is order and control, a factory of production not unlike the Mercedes plant in East London, that brings the hunters in, moves them along through the lodge, the lapa, the trail, the hide, the aim, the shot, the tracking, photographs, skinning and processing, braaiing of the meat, accommodation, and transport home of hunter, animal, weapon and field gear. The hunting game farm is thus a site of a double consumption - aesthetic and a material - that includes particular notions of the veld, the game and the black African body.

Politics of Protest, Protest Politics

Palmer didn't just kill a lion. He killed an especially good-looking and 'beloved' lion in an ostentatious and gruesome fashion that culminated in decapitation. To make things worse, that lion had a human name. To make things worse still, that name was Cecil. It's hard to think of a more innocent name than Cecil.53

It is through the act of naming that the lion called Cecil was individuated from other trophies ordinarily hunted as big game in Africa. This act of naming entails certain aesthetics, values and desires of a romantic wild Africa, often captured through the depiction of live animals under big skies with indigenous flora or spectacular sunsets under the rubric 'nature'.54 This aesthetic persists despite continued scholarship calling for a more critical engagement (see the discussion of hunting websites above).55 Cecil was beloved of many, and known through photo safaris and conservation research. Despite this adoration of Cecil, even the most general histories of the region are still overlooked. By invoking the name Cecil as 'innocent', Klint Finley completely misses the connection to Cecil John Rhodes, whom the lion was named after.56 This despite a contemporaneous, and much reported on, #RhodesMustFall movement and ongoing struggles within the universities in South Africa in protest against colonial figureheads and inheritances. The contentious debate sparked by this hunt, when put into conversation with a red Mercedes and a green Mandela, demands a critical rethinking of the relationship between information technology and the production of hunting in Africa as one of successful conservation and rural social development - a 'training' that continues the legacies of colonialism and apartheid.

Unlike Gush's Red installation, here I can only 'assemble' Cecil through the photography, narratives and portraits circulated through the media. Yet the parallels between technological imagery (still shots in the film, black and white hunting photography, Internet and social media dissemination) and the space of production (the factory and the farm), as seemingly concerned with aesthetics of beauty (a red Mercedes and a beloved lion), in fact point to blood and violence, to war. This is clear when you walk into Red - violence of factory production, labour struggle, hunting down workers who build for Mandela instead of capitalism. This is also clear in a reading of Cecil - the death of a lion, the calls for the death of his killer, the struggles of the farm labourers on the margins of a hunting economy.

The eulogies for Cecil produced in the wake of his death read as the biography of a dead human body and not of an animal. An article in the New York Times noted how some protesters latched on to the hash tag #CatLivesMatter57 which, along with the commentary about Cecil's personality and fame, seeks to place the value of the lion's life and the mournability of its death on equal level with the killing of black people.58 The arguments criticising a response like #CatLivesMatter emphasised that there is problem with the large reaction of people to Cecil when others like Sandra Bland (apparent suicide after three days in jail for a minor traffic offence) and Samuel DuBose (shot in the head by a police officer) do not get the same attention. This shows a lack of understanding of the #BlackLivesMatter and the #RhodesMustFall movements working to centre discussions on the continuing implications of racism and inequality. The local #BlackLivesMatter protests in response to the deaths of Bland, DuBose and others are linked through a hash tag to global concerns of race. Critiques of the perpetuation of systemic, institutional racism after the civil rights movement and apartheid are separated locally but connected globally in the time and technologies of globalisation of neoliberal exchanges. Joshua Williams takes this notion of mournability further, drawing on Gay and Brokely Carmichael's twitter comments about black people needing to dress up as lions in order to be mourned.59 He critiques the endless social media 'what about this cause'-outrage that fuelled the explosion of responses to Cecil. This back and forth of critique quickly moved beyond the events surrounding Cecil and became a practice of 'outrage one-upmanship'.60 Recall the epigraph from Minkley at the start of this article that merely 'seeking alternative, vernacular and multiple modernities', merely making numerical redress in volume and scope of lives that matter, deflects from an engagement with the production of black lives as marginal, with the historical sign of the black life, and how or why those people matter.

Pro- and anti-hunting arguments both sidestep the politics of race and neither address the historical processes that underpin the assumptions of who is, or should be, driving the discussion of hunting and conservation in Africa. The critique aimed at this deferral by people like Williams deliberately calls attention to white upper-class affluence as the continued normative standard. Yet this focus on whiteness and the continued racism and inequality of hunting practices fails to grapple with the larger systems of financial capital that structure the white upper class norms. In South Africa this racial concern extends both to black frustration with the ANC government and its promises of social and economic development after 1994, and to white frustration with the 'disintegration' of South African infrastructure and governance since 1994.61 This discourse on disintegration, from a hunting perspective, (re)animates the degradation and preservation narrative in the form of racial and ethnic nationalism and calls for 'making South Africa great again' (to poach a Donald Trump slogan). For white farm owners and hunters, this results in a laagering of the wagons and a tightening of the grip on control of scarce resources - land and animals, and labour.62 In many conversations with white professional hunters and farm owners, I met the same comments about how blacks have ruined the country in only 20 years and about how great life, and business, was before 'they' took over. Pre-1994 is invoked as the so-called 'good old days'. The focus here is on infrastructure and efficiency, but what goes unsaid is that this was enabled through cheap exploited labour where whites benefited from racist policies. Additionally, this infrastructure and efficiency was tied to the global network of international big game hunting that came to the farms, these sites of hunting production, to consume and extract animals and the experience of wild Africa regardless of the cost on the ground.

The efforts at redress in South Africa over the past 22 years necessarily cut into the economic, social, legal and political comforts of whites, though not all whites. Those seeming to harbour the most animosity toward these efforts of redress are the smaller farmers and the local biltong hunters, whose middle-class ways of life are being squeezed between the rise of a black middle class and the intensified accumulation of power, capital and resources of the big farms and those with political power. The anxieties around the political and economic stresses of sustaining a livelihood in a globally connected industry of hunting (marked by wealth and class) become expressed locally along racial lines and tied to the failures of both apartheid and post-apartheid. As a result the 'logic of the camp', the laagering, intensifies. Within the white farming communities of the Waterberg, a careful accounting and narration of deaths in 'farm murders' marks the intensity of this feeling of disintegration.63 The hunting of so-called 'poachers' and heightened calls for increased militarisation and patrol are part of daily life there.64 While anti-poaching is the rallying cry in the hunting areas of South Africa, the protection of the white body and the way of life for the white game farm owner or manager is necessarily incorporated in this state of militarisation. The black body, whose entrance and exit into the space of the farm is strictly controlled, is constructed both as predator (game guards and patrols) and as prey (poachers). Differentiating the two is not always 'black and white' in the racial and definite senses. Though the blood spilt from all bodies remains red.

Technology and History

A sustained look at the events around Cecil reveals the production of the post-apartheid hunting industry along technological lines. Initially this can be seen through the role of high-tech violence in Cecil's death: crossbow and gun, photography of the kill, the tracking (via Cecil's collar) to the decaying carcass. Underlying this is the production of the space of the farm. This led to the equally high-tech investigations into records of Palmer, Bronkhorst and Ndlovu, as well as hunting and conservation statistics.65 Further, this moved on to the high-tech debate and protests over Cecil and what his death meant in the forum of new communication technologies - protests marked in different ways based on who was protesting. Just as Red makes us rethink the factory production of the Mercedes, so Cecil serves rethinking the usual technologies of the hunt. The narratives that grew around Cecil expose the emerging and more efficient deployment of race through hunting in the post-apartheid era tied up in a global industry of hunting and conservation: the large protest focus on #BlackLivesMatter, #CatLivesMatter and #RhodesMustFall leaves a lack of engagement with Ndlovu the black farm owner and the modes of production of the game farm.

If we take Bernard Stiegler's assertion that today's world suffers from attention deficiency and that information technology fills the void of time that coincides with the symptoms of boredom and apathy - a malaise that is 'the crux of a much more general blockage of thought - and much more than thought'66 - we must, then, think carefully about the (re)presentation of racial assumptions embedded in narratives that get consumed, internalised and repeated but not critically investigated. In a world of democratised imagery and art via the platforms of social media, the work of Red as an installation and film demands a sustained engagement with the technologies that produce a hyper-saturation of information. The very tangible relationship to time in the experience of information through Red - where a viewer physically has to walk, stop, look and listen - marks a pause that demands a witnessing of events, one that is different to the scrolling culture of the Facebook feed via phone and computer. Yet there is something about the hyper-industrial nature of information technology that short-circuits the sustained engagement with issues like race and its continuing legacies that an event such as Cecil should demand instead of just garnering brief attention and comment.67 Perhaps it is precisely in the 'hyper' nature of information filling the void of boredom and apathy68 - always a new event trending, a new cause to devote a 'like' and a 'comment' to - that the likelihood of sustaining an attentive critique at a deep level across a broad audience is lost.

Despite Time magazine naming Cecil the most influential animal of 2016,69 there has been very little global public attention paid to Cecil and the debates around him since August and September 2015.70 Instead, what does persist is the legacy of power relations along racial lines in hunting. Internet and information technology are not a unifying way of dissolving this power divide between technology and its ability to other, or to deflect from the production of the other. But, via Stiegler, it is a language that few understand and whose presentations we are merely subject to as consumers, not active but latent participants in its exercise of power.71

The image of Mandela with his blesbok promised a future that has yet to come.72 Frustrated rural black South Africans see this continued marginalisation as a violent and exclusionary takeover of an ANC liberation struggle by global capital's hunting institutions; liberals see the relative stability of trophy hunting, though threatened by poaching and animal rights activists, as a mark of society's progress, with black South Africans now enjoying many of the rights and protections once denied them. These are roughly the two camps that comprise the global Cecil debate. They highlight the problem of the limits of 'alternatives' - better conservation, more regulation and heavier surveillance as forms of redress. We need to shift the focus from endless 'alternative, vernacular and multiple modernities', as Minkley states, to one of understanding the conditions of the current modes of production that govern hunting.73

If hunting is to rediscover the politics that the image of Mandela in 1991 seemed to promise, an event such as the death of Cecil must be approached the way Gush approached the red Mercedes. The technologies of hunting - lions, hunters, farms, workers, fences, guns, photographs, websites and all - must be disassembled and reassembled in order provide a fresh look at how life for black South African game farm workers in a white-owned and organised industry remains a production of violence, with the animals and the most marginalised people sitting at the lethal end of (or in the sites and sights of) the gun, their blood staining the veld.

1 P. Walsh and B. Stahl, 'Twin Cities Dentist Admits to Killing Beloved Lion, Thought He Was Acting Legally', Star Tribune, 29 July 2015. http://www.startribune.com/zimbabwe-2-to-appear-in-court-for-killing-cecil-the-lion/318828251/, last accessed 3 December 2016.

2 Ibid.

3 Ibid. Also see the Zimbabwe Parks and Wildlife Management Authority, 'Theo Bronchorst [sic], a professional hunter with Bushman Safaris is facing criminal charges for allegedly killing Cecil the lion', 27 July 2015, http://www.zimparks.org/index.php/mc/210-joint-press-statement-by-zimbabwe-parks-and-wildlife-management-authority-and-safari-operators-association-of-zimbabwe-on-the-illegal-hunt-of-a-collared-lion-at-antoinette-farm-hwange-district-on-1-july-2015-in-gwayi-conservancy-by-bushman-safaris-profess, last accessed 3 December 2016. Ultimately Palmer was never charged in Zimbabwe though he can only return there as a tourist and not to hunt. Bronkhorst was acquitted after months of trial postponement. Ndlovu, after being released on bail, became a witness for the State.

4 Presumably these trackers were from the Zimbabwe Parks and Wildlife Management Authority or with the Oxford research team searching for Cecil via his tracking collar. WildCRU: Wildlife Conservation Research Unit, 'Cecil the Lion', https://www.wildcru.org/cecil-home/, last accessed 3 December 2016.

5 A. Walker, 'Liberal Hypocrisy over Mandela Game Hunting', Townhall, 4 August2015, http://townhall.com/tipsheet/andrewalker/2015/08/04/liberal-hypocrisy-over-mandela-game-hunting-n2034492, last accessed 3 December 2016.

6 E. Koch, 'Mandela Goes Green', Weekly Mail, 5 April 1991, http://madiba.mg.co.za/article/1991-04-05-mandela-goes-green, last accessed 3 December 2016. Walker cited this to argue that Walter Palmer should not be vilified for killing Cecil when Nelson Mandela was lauded as a conservationist for his hunting. Still, this argument is merely a broad one of liberal versus conservative. There is no real engagement with a comparison of Mandela and Palmer when it comes to politics, nationality, animal shot, method, and purpose of hunt. But this was the article that made the connection between Cecil, hunting and Mandela.

7 Ibid.

8 Ibid.

9 S. Gush, Red, 12 April 2015, http://www.simongush.net/red-2/. The film is embedded in Gush's website. S. Gush and J. Cairns, Red, 2014, last accessed 3 December 2016.

10 Gush and Cairns, Red, 2014.

11 R. Debray, 'Socialism: A Life Cycle', New Left Review, 46, July-August 2007, 25.

12 Zimbabwe Parks and Wildlife Management Authority, 'Theo Bronchorst'. It is notable that, until now, no one seems to have made the connection between Cecil's reported beheading and the irony of the farm being called 'Antoinette'.

13 In part those concerns are being realised. Since August 2015, 40 airlines have banned the shipment of hunting trophies, and the United States Fish and Wildlife Service has listed African lions as threatened under the Endangered Species Act, which could have implications for the number of US trophy hunters travelling to South Africa. South African Predator Association, 'Is the Lion the New Rhino?', 24 May 2016, http://www.southafricanpredatorassociation.org/n7/general-news/is-the-lion-the-new-rhino?.html, last accessed 3 December 2016. I plan to follow up with my contacts about impacts in the Waterberg during future interviews.

14 The potentially negative economic impact of bans on hunting trophy transportation resulting from reactions to Cecil's killing will have consequences for all farms in the region, however those consequences will fall unequally across racial lines, which are marked by wealth and class.

15 G. Minkley, 'Legacies of Struggle: Martin Legassick and the Re-Imagining of South African History', South African Historical Journal, 56, 1, 2006, 8.

16 Ibid, 6.

17 T. Chirimambowa, 'The Untold Story of Cecil the Lion', 23 August 2015, http://nehandaradio.com/2015/08/23/the-untold-story-of-cecil-the-lion/, last accessed 3 December 2016.

18 This positionality of the black body in hunting is discussed in more detail, via Mandela, below.

19 Ndlovu falls out of the social media narrative quite quickly as the focus of the vitriol and call for criminal charges centres more heavily on Palmer and Bronkhorst.

20 Q. Ismail, '(Not) at Home in (Hindu) India: Amin, Chakrabarty, and the Critique of History', Cultural Critique, 68, Winter 2008, 213. On conscription and its inescapability see D. Scott, Conscripts of Modernity: The Tragedy of Colonial Enlightenment (Durham: Duke University Press, 2004), 21.

21 Ismail, '(Not) at Home', 211.

22 Drawing on Helena Pohlandt-McCormick's comments from 'Red Assembly'.

23 J. Mowitt, Re-Takes: Postcoloniality and Foreign Film Languages (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2005), xxviii. Cited in Ismail, '(Not) At Home', 216.

24 On the modes of historical production, see P. Lalu, The Deaths of Hintsa: Postapartheid South Africa and the Shape of Recurring Pasts (Cape Town: HSRC Press, 2009).

25 Ismail, '(Not) at Home', 238.

26 S. Gush, 'Red, Ann Bryant Gallery, East London', photo essay (Kronos 2016, this issue).

27 See the section 'The Production of the Ordinary Technologies of a Hunt' below.

28 Koch, 'Mandela Goes Green'. Another serendipitous connection that links to technology and history arises here: a Google search of 'Mandela Goes Green' produces a first-page result for an article about how many people remember the colour chartreuse as reddish when it is in fact more like green. Further, this article appears on a website called 'Mandela Effect' that promotes theories of alternative memories and realities (thus, alternative histories?). The website began after research into the paranormal prompted by the website creator Fiona Broome's conversations about memories she and others had that Mandela had died in prison. Setting aside a debate about such memories as false versus alternative reality, such a juxtaposition of red-green as a 'Mandela effect' is productive for attempting to think differently about historical representation via Cecil/Red/Mandela. See F. Broome, 'Chartreuse: Red or Green? (and other colors)', 15 February 2015, http://mandelaeffect.com/chartreuse-red-or-green/, last accessed 3 December 2016.

29 Mandela is the hero and the hunter. He evokes the heroic work of the workers and the struggle, the manly practice of hunting, the aesthetic reading and contemplation of hunting and nature, and a reading of nature that produced and was reproduced in the physical texts and images of hunting narratives and travelogues.

30 Koch, 'Mandela Goes Green'.

31 J. Adams and T. McShane, The Myth of Wild Africa: Conservation Without Illusion (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997), 6.

32 Again, there are small shifts toward black South Africa in game farm ownership though these are by wealthy elites.

33 Koch, 'Mandela Goes Green'.

34 Ibid.

35 Ibid.

36 Ibid.

37 On the continuing challenges of thinking historically about race and social transformation, see S. Pillay, 'Translating "South Africa": Race, Colonialism and Challenges of Critical Thought after Apartheid' in H. Jacklin and P. Vale (eds), Re-Imagining the Social in South Africa: Critique, Theory and Post-Apartheid Society (Durban: University of KwaZulu-Natal Press, 2009), 235-67.

38 An example of this need for proper training is the South African Wildlife College (SAWC), initially conceived of in 1992 and opened in 1997. Coincidentally, in 2006, Mercedes-Benz sponsored the new automotive workshop for the college. See South African Wildlife College, http://www.wildlifecollege.org.za/index.php?id=246, last accessed 3 December 2016. Predating SAWC, Lapalala Wilderness School, http://www.lwschool.org/history/ last accessed 3 December 2016, was started by Clive Walker in the Waterberg in 1985. He remains a central figure of conservation in the region.

39 The conceptual grounds of the 'Red Assembly' workshop marked this as 'the concern over the failure or limitations of the transition, the hardening fronts of nationalism, the depredations of late capitalism, and the prickly assertion of disciplinary boundaries and disagreement' where 'questions - even those as fundamental as those of race, class and gender - sound different depending on the disciplinary frame within which they are posed.' H. Pohlandt-McCormick, G. Minkley, J. Mowitt and L. Witz, 'Red Assembly: East London Calling', parallax, 22, 2, 2016, 125-6.

40 Hunting practices and ideas around race, technology, preservation, fair chase, tracking and capture are inescapable from, and 'conscripted' to, conceptual and technological workings of modernity. Scott, Conscripts of Modernity, 21.

41 I am speaking here primarily about American and European hunters who were the central figures in the debates about Cecil. There are certainly large contingents of non-white big game hunters from other parts of Africa, the Middle East, the Indian subcontinent, and China who come to South Africa to hunt.

42 Adams and McShane, Myth of Wild Africa, xi-xix.

43 I am reading 'aesthetic' here through Susan Buck-Morss's analysis of Walter Benjamin. She argues that aesthetics need to be understood as a 'synaesthetic system', described as an experience of sense, thought, memory and time. This is what Terry Eagleton refers to as 'a discourse of the body'. S. Buck-Morss, 'Aesthetics and Anaesthetics: Walter Benjamin's Artwork Essay Reconsidered', October, 62, 1992, 6 and 13. On the relationship between art and aesthetics - and, I would add, history - I find Robert McGregor's notion of aesthetic theory useful. He describes Aesthetic theory as one that incorporates 'all the essential concepts: aesthetic object, attitude, experience, and value … [which together] … provide a framework for the discussion of the aesthetic and its relation to art.' R. McGregor, 'Art and the Aesthetic', Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, 32, 4, Summer 1974, 551.

44 This returns to how naming Cecil and the event of his shooting turn an ordinary lion into a Lion, and how an otherwise unremarkable Mercedes becomes a symbol and a labour of love when attached to Mandel. This notion of 'ordinary-ish-ness' is a combination of ideas tabled during the 'Red Assembly' workshop by Tom Wolfe, John Mowitt, and Kevin Murphy to seek how art interrupts the processes of what we know and practise without thinking, interrupting the 'ordinary' here as a routine made unthought, or unexamined, through training. See also J. Mowitt, 'Re(a)d Work', parallax, 22, 2, 2016, 139-52.

45 All these components amount to an inventory of the 'technologies' associated with the hunt, just as an exhibition catalogue presents the components and workings of what is on show.

46 Interestingly, Land Rover recently rolled the final Land Rover Defender off the assembly line. The Defender was introduced in the mid-20th century, and the 'end of an era' of the quintessential safari and utility vehicle was marked by a BBC interview with the head of the Land Rover Defender Owner's Club of South Africa. This direct connection to Red in terms of the technologies and aesthetics of the vehicle, in hunting safaris, and its production and use is an opportunity for research. Interview accessed online - BBC, 'Last Land Rover rolls off production line', 29 January 2016, http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p03h08jf, last accessed 3 December 2016.

47 Again, this is Scott's argument about modernity, where the categories and concepts that mark notions of hunting as conservation as progressive, liberal, market-driven cannot be escaped by the labourer finding work through a practice of racial numerical redress known as 'social responsibility'. This concept in itself implies an unequal power relation, where the existing structures of hunting practices are 'responsible' for training people to fill the labour roles in game farming - a recurrence of a paternalist mode of stewardship that extends into control of land and resources.

48 H. Wels, Securing Wilderness Landscapes in South Africa: Nick Steele, Private Wildlife Conservancies and Saving Rhinos (Leiden: Koninklijke Brill NV, 2015), 28. Wels draws the phrase 'logic of the camp' from B. Diken and C.B. Laustsen, The Culture of Exception: Sociology Facing the Camp (London & New York: Routledge, 2005).

49 Wels, Securing Wilderness Landscapes, 28.

50 Such 'training' harks back to the English-Afrikaner-European travelogues and diaries of the 19th century and to early photography and the artefacts and trophies of hunting collections. These sources established the colonial aesthetics of hunting in Africa that continue to dominate our understanding, imaginaries, enactment, discourses and so on of hunting today, just as the heroic image of struggle dominates our understanding of South Africa post-apartheid, despite the recent ruptures.

51 Ibid, 116-20.

52 Ibid, 119, Fig. 22.

53 J. Hamblin. 'My Outrage Is Better Than Your Outrage', Atlantic, 31 July 2015, http://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2015/07/outrage-rip-cecil-lion/400037/, last accessed 3 December 2016. Hamblin comments on the use of the term 'beloved' in K. Finley, 'Internet Attacks Lion Killer with Poisoned Yelp Reviews', Wired, 28 July 2015, http://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2015/07/outrage-rip-cecil-lion/400037/, last accessed 3 December 2016.

54 For examples in the Waterberg see, http://lapalala.com/gallery/, http://waterbergnatureconservancy.org.za, last accessed 3 December 2016. A Google images search for 'Waterberg hunting farms' produces a series of these images.

55 The critique is found in scholarship exemplified by Adams and McShane. An example of the persistence of this aesthetic in literature on the Waterberg is L. Rodger, Waterberg: Vintage Waterberg and Timeless Waterberg (Johannesburg: Rodger Family, 2010).

56 H. Alexander and P. Thornycroft, 'Cecil the Lion's Final Photograph', Telegraph, 28 July 2015, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/africaandindianocean/zimbabwe/11768872/Cecil-the-lions-final-photograph.html, last accessed 3 December 2016. The associations between 'Red Assembly' and Cecil the Lion as the namesake of Cecil Rhodes are intriguing - Rhodes's Cape to Cairo railway project was meant to be a 'red line' across the continent, invoking the red colour used for British colonies on maps. See L. Freeman, 'Rhodes's "All Red" Route: The Effect of the War on the Cape-to-Cairo and the Control of a Continent' in W. Page and A. Page (eds), The World's Work: A History of Our Time, 29: November 1914 to April 1915 (New York: Doubleday, Page, 1915), 327-55, https://archive.org/details/worldswork07pagegoog, last accessed 3 December 2016.

57 C. Capecchi and K. Rogers, 'Killer of Cecil the Lion Finds Out That He Is a Target Now, of Internet Vigilantism', New York Times, 29 July 2015, http://www.nytimes.com/2015/07/30/us/cecil-the-lion-walter-palmer.html, last accessed 3 December 2016.

58 R. Gay, 'Of Lions and Men: Mourning Samuel DuBose and Cecil the Lion', New York Times, 31 July 2015, http://mobile.nytimes.com/2015/08/01/opinion/of-lions-and-men-mourning-samuel-dubose-and-cecil-the-lion.html?referrer&_r=0, last accessed 3 December 2016. Additionally, a Cecil tribute gallery was started on the WildCRU website of the Oxford research team that was monitoring Cecil. This invocation of the aesthetic of Cecil for scientific research and conservation efforts is one of the many ways technology proliferates a politics of conservation that deflects from, or undermines, discussions of race, especially when combined with a hash tag like #CatLivesMatter. https://www.wildcru.org/cecil-the-lion-gallery/, last accessed 3 December 2016.

59 J. Williams, 'The Lions and the Hunters', Africa Is a Country, 3 August 2015, http://africasacountry.com/2015/08/the-lions-and-the-hunters/, last accessed 3 December 2016. This critique of black people represented as animals resonates with the recent controversy surrounding the South African political cartoonist Jonathan Shapiro ('Zapiro'). E. McKaiser, 'Artistic Criticism Isn't Censorship', Cape Times, 29 May 2016, http://www.iol.co.za/capetimes/artistic-criticism-isnt-censorship-2027697, last accessed 3 December 2016.

60 Hamblin, 'My Outrage'.

61 The sentiments of white frustration about the disintegration of South Africa (as with the rotting disintegrating corpse of Cecil that could not be retrieved, and resonating also with the disassembled red Mercedes, gutted and displayed as art) were a common theme in my discussion with hunters and farm owners from the Waterberg in the immediate aftermath of Cecil's death. Palmer made an easy scapegoat as the foreign hunter from the United States who did not follow the conventions of (white) hunting.

62 Recall Wels's 'logic of the camp' here.

63 Shortly after becoming Facebook 'friends' with a contact in South Africa, I began seeing new posts as well as suggested sites in my newsfeed-related farm murders, such as the 'Stop Farm Attacks & Murders' page, https://www.facebook.com/StopFarmAttacksMudersInSouthAfrica/, last accessed 3 December 2016. Without these connections, I would not have such 'news' in my algorithm and be exposed to it. This illustrates how people are connected, what crosses various people's newsfeeds, through which media outlets, and in relation to what other events.

64 During an informal conversation in the Marken area, a farmer detailed how he had not had much sleep that week (early August 2015) because he spent most of his nights on anti-poaching patrols. His days were spent in the veld with hunting clients. He carried a handgun on his belt. Handguns are not used to hunt animals, they are for hunting people.

65 The Oxford research group WildCRU, reporting on the aftermath of Cecil, used GPS records and large-scale online keyword tracking to detail the social media trends of the Cecil story - Cecil's digital footprints, or spoor. David W. Macdonald, Kim S. Jacobsen, Dawn Burnham, Paul J. Johnson and Andrew J. Loveridge, 'Cecil: A Moment or a Movement? Analysis of Media Coverage of the Death of a Lion, Panthera leo', Animals, 6, 26, 25 April 2016, 1-13. Additionally, the speed with which reporters accessed and published the backstories of Palmer, Bronkhorst and Ndlovu indicate the prolific availability and breadth of technological penetration into society.

66 B. Stiegler, Technics and Time, 3: Cinematic Time and the Question of Malaise, trans S. Barker (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2011), 6.

67 WildCRU, who had been monitoring Cecil as part of their conservation work, has chronicled the impact of Cecil and has worked to make 'Cecil the moment' into Cecil the Movement'. D.W. Macdonald et al, 'Cecil: A Moment or a Movement?'

68 Stiegler, Technics and Time, 6.

69 J. Stein, 'These Are Time's 100 Most Influential Animals of 2016', Time, 21 April 2016, http://time.com/4301509/most-influential-animals/, last accessed 3 December 2016.

70 The sustained engagement with Cecil remains primarily confined to those whose livelihoods are linked directly to hunting and conservation: hunters, landowners, labourers and researchers.

71 B. Stiegler, Symbolic Misery, 1: The Hyper-Industrial Epoch trans B. Norman (Malden: Polity, 2014), 59.

72 P. Lalu, 'Mandela Is Very Much with Us!', Economic & Political Weekly, 48, 26-27, 29 June 2013, http://www.epw.in/journal/2013/26-27/web-exclusives/mandela-very-much-us.html, last accessed 3 December 2016.

73 Minkley, 'Legacies of Struggle', 8. I also draw here on Helena Pohlandt-McCormick's comments from 'Red Assembly' that tragedy 'rubs the wrong way' and how perhaps we need to view tragedy as an inheritance, or, to put it slightly differently, perhaps as one of recurring training.