Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Kronos

versão On-line ISSN 2309-9585

versão impressa ISSN 0259-0190

Kronos vol.42 no.1 Cape Town Nov. 2016

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2309-9585/2016/v42a4

ARTICLES

Screwing the assembly line: queerness, art-making and Mandela's Mercedes-Benz

Elliot James

Discipline of History, University of Minnesota Morris

ABSTRACT

This article analyses the bed installation in Simon Gush's Red exhibit to draw attention to the 'sleep-in' aspect of the 1990 East London Mercedes-Benz strike. It shows how the strike narrative's emphasis on the shop workers and Nelson Mandela's flawless red Mercedes-Benz automatically insulates the strike's central sleep-in component from the topic of queer desire. By revealing Red's beds and the acts thereon as the strike narrative's 'queer limit', the article uses Gush and Emma Sulkowicz's techniques to reinvent the sleep-in as a complex space of homosociality and queer self-discovery. Doing so builds on Gush's installations and uses performance to deliberately 'pervert' the strike's collective memory and offer up strategies for queer critique in (South) African historiography.

This article asks an odd question of East London's 1990 Mercedes-Benz sleep-in strike: if we do not know for sure what the hundreds of unidentified men were doing on the beds they made, should we automatically assume that none of them were sexually intimate with each other? I intentionally raise eyebrows here to open up the varying retellings of the sleep-in strike to queer imagination. While nationalists everywhere adamantly oppose any place for queer utopias in 'usable' pasts,1 my question does not stray far from the critical issue framing the collective memory of the strike. What exactly transpired during those nine weeks in 1990, Simon Gush and James Cairns' film Red demonstrated, would determine whether or not the Mercedes-Benz employees' activities were grounds for termination. While the very presence of beds in Simon Gush's Red installation would strongly suggest that the shop stewards and workers indeed occupied the plant, the question of intent lingered on even as the different interlocutors recounted the story, especially as the strike was being called a 'sleep-in'. Still, did the Mercedes-Benz employees occupy the plant overnight, or did they not? And if they did, what were they doing?

The odd question playfully sheds a different light on the shop stewards and workers' testimonies in the film Red. In the pages that follow I show how Thembalethu Fikizolo and Mteteleni Tshete's references to heterosexual courtship and homosocial domesticity, in particular, draw our attention to the way historical actors use gender and sexuality to support truth claims. Moreover, avoiding the assumption that the Mercedes-Benz employees did nothing but sleep on their makeshift beds enables us to consider the role homosocial desire and performativity played during the sleep-in as well as in creative representations of the event like Gush's Red artwork. Scholars of 'queer' Africa have recently pioneered projects that imagine gender nonconformity in archives and origin stories. At the same time, however, through its increased attention to human subjectivity, Queer African Studies has yet to consider how looking at the social role of automobiles helps us understand gender nonconformity in history.2 This article uses beds as a focal point to bring both itineraries together.

The beds in Red, in and of themselves, raise questions about dissidence and nonconformity. Beds seen solely as objects of rest and leisure, for example, do not fit in art galleries of active onlookers and collectors, nor do they belong in workers' strikes or any of southern Africa's liberation struggles. Who fights for freedom lying down? When beds appear in South Africa's history museums, their presence in home, hostel and jail cell recreations reminds viewers of historical actors' absence. Absent also are their everyday, intimate moments (sleep, sex and so on). Instead, museums like Lwandle, KwaMuhle, and Robben Island use beds to replay how apartheid violence entered black homes, inevitably turning their bedrooms into places of abjection. The beds in museum recreations of 'unhomely' black homes collapse the bed into an amorphous struggle. Together, Red the film and the bed display wrestle with meanings of the bed in art and history museums. While Gush's installations depict beds as playful and disruptive, the beds in Red the film's testimonies ossify beds solely as sites of struggle.3

Drawing attention to beds as spaces of desire within this collection of essays shifts our attention away from an automobile in motion to objects at and of rest. Paying attention to beds importantly avoids any privileging of the automobile, in particular, and brings the cornered-off mattresses to the centre of examination. Contemplating and making sense of the beds' solitude also illuminates tangential memories. While translating my solitary analysis of beds for the collaborative nature of the 'Red Assembly' workshop, for example, I could not help but remember a friend who recently succumbed to the profound challenges of advancing queer expression outside the order of disciplinary knowledge.4 Bringing memories of my friend to bear through the loneliness of Red's beds illuminates what Matt Richardson describes as the 'queer limit'.5 I argue, art has an important role to play in the space that exceeds the political relevance of the strike for understanding histories of labour and struggle in southern Africa.

Bringing beds into closer view illuminates the playful creativity of work, political activity and the writing of history.6 My substituting 'Red Assembly' for 'Bed Assembly' reminds us of the sensuality of labour and demonstrates how well the different 'beds' in Red captured the oxymoronic character of work that's sexy. The Mercedes-Benz employers worried about what would happen if they got into bed with the National Union of Metalworkers of South Africa (NUMSA) or with management, for example. The shop stewards bragged about how working for Mercedes-Benz could compel women to join them in bed. While the very idea of imagining hundreds of men sleeping on beds together would mark the queer limit of remembering the sleep-in either as a strike or an ordinary third shift, the beds offer an important space to contemplate the politics of the 1990 event alongside its aesthetics.

Beds as sites of art and politics resonate beyond the geographic scope of southern Africa. Three days prior to the 18 May 2014 closing of Simon Gush's Red installation in Johannesburg, a Columbia University (in New York City) student Emma Sulkowicz published an opinion piece in Time magazine lamenting the failed indictment of a classmate who sexually assaulted her in her own dormitory bed.7 Responding to critics questioning the legitimacy of her testimony, several months later Sulkowicz made international news with the endurance performance art piece Mattress Performance or Carry That Weight. 'I will be carrying this dorm room mattress with me everywhere I go for as long as I attend the same school as my rapist,' Sulkowicz explains in a video interview, which went viral on September 2014. '[My] performance art piece utilises elements of protest.' Indeed, for her, 'the act of carrying something that is normally found in our bedroom out into the light' was a political act.8 And witnessing Sulkowicz muster up the strength to carry the mattress day after day made it much more difficult not to believe her. Still, Columbia never expelled the man.9

Gush's beds in Red pick up on the way Sulkowicz's bed used art-making to draw public attention to questions of intimacy, justice and what constitutes the historical record. Together, Mattress Performance and Red's beds reveal the potential for art-making to innovate historical inquiry through queer notions of gender and sexuality. Gush and Sulkowicz's bed aesthetics also refresh Zackie Achmat's decades-old intervention in the historiography of same-sex desire in South Africa. 'Writing the black working class into history and uncovering the mechanisms of its exploitation', Achmat contended about social history, 'have now become theoretical blockages to innovation in historical research.'10 This article interprets Achmat's analysis as a script and choreographs his critique as a performance, using Gush and Sulkowicz's technique to open up the sleep-in strike's history to questions about gender and sexuality. Like Achmat's 'Apostles of Civilised Vice', this approach 'perverts history' by revealing the beds in Red as objects and sites of desire.

I first show the factors that emerge in assembling beds for the historical, artistic and material construction of the 1990 sleep-in strike at the Mercedes-Benz plant in East London. After exploring the exhibit's materials (the film, car parts, strike uniforms and beds), I discuss how Gush's creative use of the beds in particular brings desire into the sleep-in strike story. While '''sexual desire" [is] a concept that social history singularly lacks in its array of causes and effects', as Achmat contends, the Red beds make desire unavoidable.11 The second part of the article explores how the film Red, and the subjects interviewed for the film, on the other hand, wrestle with desire to settle the tensions in the sleep-in strike's narrative. Here I move away from the bed installation and the strike's historical narrative by paying close attention to how two pauses in the film compensate for the interviewees' seemingly tangential references to homosociality. At each of these points, Gush and Cairns remove the names and words of the interviewees and substitute their voices with non-human sounds and empty frames. While both moments bring us to the queer limit of the sleep-in strike story, I argue that the pauses offer an opportunity for art-making.

The final section returns to the queer question I posed in the introduction, opens up a pause in one of the film's testimonies, and recreates my performance at the 'Red Assembly' workshop in essay form. My presentation, entitled 'Bed Assembly and the Queer Question: A Collage in Blue', followed Achmat's play on Marx's eleventh thesis on Feurbach. 'The philosophers have only interpreted the world, in various ways,' Achmat wrote, quoting Marx while adding his own spin, 'the point is to pervert it.'12 My presentation perverted the story of the sleep-in strike by imagining the legendary shop worker who first conceived of the sleep-in as a queer theorist. Reorganising the pieces and parts of the story alongside a soundtrack by Thelonious Monk illuminated the improvisational nature of sleeping-in together. Borrowing the term from a rich scholarly literature, I name this process of performance art-making 'queering'. Queering the strike reveals the sleep-in less as a march to political consciousness, and more as a moment of interrupting the march of capital and history. In other words, queering the sleep-in strike doubly perverts history and screws the assembly line.

Screwing the Assembly Line

The fragmentary nature of Simon Gush's recreation of Nelson Mandela's red Mercedes-Benz already disrupts the rationale of the assembly line. The history of the Ford Model T is the quintessence of how the assembly line expanded US imperialism's reach across the Atlantic at the turn of the twentieth century. Red's Mercedes-Benz parts (from the hood to the doors and its interior), protest uniforms, and beds showed how shop stewards and workers in East London transformed the space of the plant as well as the things therein to bring the intensification of capitalism to a halt in 1990. As Goodman Lucwaba explains in the film Red, 'the material that the people were actually using [to make the beds] came from this building [the Mercedes-Benz plant]. Those white clothes that you see them wearing in that video', Lucwaba continues, 'came from this building [too]. That was the seat assembly material.' Together, Gush and the shop stewards and workers assembled the material against the order of the day. Building Mercedes-Benzes to sell to consumers was insufficient. The Mercedes-Benz employees' labour of love was an affront to capital. Instead of delivering the perfect vehicle to the market, the shop stewards gave it away.

Gush also recreated the temporality of the strike, from the production of the red Mercedes to the construction of the beds. Like the strikers, Gush and his collaborators made the sleep-in strike beds and uniforms from car upholstery materials, ostensibly from a Mercedes-Benz. As Mteteleni Tshete reminds us in the film, the strikers only began making the beds when they realised they would be staying overnight - something they had not originally planned. '[Only] after the meeting was closed then they wanted to make a place to sleep,' Tshete remembers. 'So everyone saw the materials in K site and they took the material and slept. It was a spontaneous decision,' He recalls strikers saying, 'Okay fine. We are sleeping over then. This is what will make us sleep comfortable here.'

Thus, if one followed the narrative of the strike that the film illuminates - from the decision to build the red Mercedes to the strike that ensued afterwards - and did so while scrolling the exhibit's page on the Internet from its heading to the footer, then one could envision a protesting shop worker actively stripping the seats off the red Mercedes made for Mandela and then gluing and sewing the pieces together to make beds and uniforms. The Internet version of the installation opens with the iconic Mercedes-Benz emblem adorning a red 500SE hood, and then encourages the viewer to play the film while inviting the multi-tasking observer to listen to the story of the strike ('in the strikers' own words'), and view, at the very same time, the Mercedes in pieces, with close-ups of its interior stripped of its seat upholstery. After revealing the car, the Internet version invites the viewer to look at the uniforms13 and finally the beds.14 In other words, the uniforms and beds act as backdrop to the car rather than the other way round. Each item also performs differently in the installation. While Gush made the sleep-in strike beds from the type of upholstery materials used to make the same beds and uniforms during the 1990 strike, the Red installation sets them up differently in their separate rooms. Whereas Gush hung Mokotjo Mohulo's pristine-looking strike uniforms on invisible wires, he gave the beds life by twisting them so they did not lie flat and then suspended them on wooden planks buttressed by oxidised poles. In the gallery of beds, the setting draws as much attention as the beds themselves. Moreover, while he propped up the car parts seamlessly on stands and walls, the beds were laid uncomfortably contorted on freshly cut boards.

Not only do the beds clash dramatically with all the other components, they also incorporate pieces and parts of them. Unlike the film and the uniforms, for example, the bed installation joins the Mercedes by introducing the primary colour red - the subject of the exhibit - with its rusted suspension poles. But the beds then add yellows with their undersides and blues behind chipped paint. They also replicate and mix the shades of grey from the film with different beiges from the strike uniforms both on their sheets and in the poles. Their rusty scaffolding contrasts too with the bold reds, blacks, and chromes of the car body, adding rough colour schemes to the tones in the rest of the exhibit. Thus, the beds are the one aspect of the installation that incorporates primary colours, greys and earth tones. But they also go further by piecing and mixing these colours together. While the uniforms and car parts reveal the strike in action, the beds signal the strike at rest. Finally, the beds, by their very being, echo Emma Sulkowicz's provocation of bringing a household item into the 'public sphere' and onto the politicised shop floor. Even at rest, the beds actively interrupt the site of politics at work.

The twisted beds on wooden planks and rusted poles in the exhibition direct our attention to moments of rest in the film's strike narrative. While the website made the strike seem like a seamless progression from disgruntled, politicised Mercedes-Benz shop workers making a car for Mandela to those same workers going on strike, the film Red's primary interlocutors fundamentally disagreed about one thing: what happened on those beds and between whom. While the car parts and protest uniforms tell a clear story of the strike, the beds leave open what Mteteleni Tshete meant when he kept mentioning that the sleep-in experience 'was not a good experience at all'.

Gender as Evidence and the Search for Sexuality

The story of the sleep-in strike has never been clear. The interlocutors in Gush and Cairns' film accompanying Red disagree over the exact goings-on during the sleep-in strike. Did the stewards and workers sleep in the plant? Did the Mercedes-Benz employees go home? And if some stayed, what happened on the beds? Importantly, this line of questioning makes it impossible to ever consider the shop room floor or the sleep-in strike beds as spaces of desire. This was much more than an oversight. Social history's displacement of desire, Achmat contends, was its method's 'logical conclusion'.15

The first set of narratives in the film place the strike squarely within perhaps the most logical frame of South African social history: collective action. This move was deliberate. Despite their different social locations, Philip Groom, Ian Russell and Andile Ntsonkota, for example, all frame the space of the Mercedes-Benz plant as an important site of resistance to apartheid. 'What was happening outside was happening inside,' Groom comments, suggesting that strikes were frequent everywhere in South Africa in the mid-1980s, so the sleep-in strike was certainly bound to happen. Russell mentions that the ensuing strike within the plant 'was a microcosm of everything that had gone wrong in the country', implying that workplace politics inevitably adopted racial oppositions in pitting whites against blacks as well as managers against workers and local unions versus national ones. The opening segment ends with Ntsonkota: 'We carried the baggage of the struggle into the workplace,' going on to say, 'you would use the factory as the battleground for liberation.' Together, each comment coheres to confirm the installation's retelling of what they all agree was an important event in the bottom-up history of the country. No one fought lying down.

While every interlocutor describes the strike through tropes of struggle and resistance, they each tell different stories. Although he cannot remember exactly how much time he spent striking, Mteteleni Tshete is certain that the strikers arrived and left the plant as they pleased. 'We used to go out and buy food,' he reasonably explains. 'You enter and then you leave.' But Thembalethu Fikizolo denies accusations from management that the workers occupied the plant. For him, 'occupation' means civil disobedience. The real political activity took place outside the plant, he points out, not inside of it. 'No, no, we were not in the factory, we were all over the township. We were mobilising and organising people. But some were confused,' he admits. 'Old people [in particular] didn't really understand what was going on' so they stayed around. Still, Ian Russell is certain: 'If I recall correctly, it was about a thousand' occupying the plant at one stage.

Whether or not the shop stewards and workers remained in the plant, what people did there was of the utmost importance because anyone determined to be involved in the strike lost their job. And even as they denied sleeping-in, the beds in the exhibit told another story. By including beds in Red, Gush validated the strike and lamented the fact that so many lost their jobs. Still, it is reasonable to assume that some workers only showed up on the strike floor to participate in the negotiations, while others either stayed overnight or mobilised as Fikizolo says he did in the townships. But it's precisely because the strikers' very presence - that is, their 'occupation' - overnight in the plant was a point of debate in narrating the event that the beds became important during the strike and in the installation commemorating it.

This is my point about the debate over the 'occupation'. While their views clash, the interlocutors in the film gender the historical record to support their different positions. Tshete, for example, emphasises the gendered nature of automobile labour to prove that the strike was an overnight occupation on beds, and that most of the men were involved. 'Obviously we are from our houses,' Tshete explains. 'You must remember that at the time, the plant was having only males, you know. Now we have to use toilets day and night,' Tshete complains. 'And there were no cleaning staff. So it was not good.' Fikizolo, on the other hand, explains that the shop stewards and workers had much more to gain in the townships. Women admired their work and expected the stewards to keep their jobs in order to court them. 'In the area, we were known [as] well-paid employees', he remembers. 'Best dressed, beautiful cars, lots of cash to buy liquor, to entertain and socialise, you know. Girlfriends look at you,' he adds. 'The girls admire you working at Mercedes. Status.' Fikozolo understands the risks of losing that status. No status, no girlfriends.

Tshete and Fikizolo's accounts invite inquiry into other moments where gendered evidence either validate or disprove the sleep-in story's claims. Did Nelson Mandela ever use the red Mercedes-Benz, for example? Was the car a vehicle or a symbol? When the plant unveiled the red Mercedes, Mandela and Winnie Madikizela-Mandela were right there. Groom recalls, 'Winnie quipped to me, "Ah no no no no no no - this is not his car, it's my car. He can't drive. He's going to sit in the back seat."' Recalling the incident, Groom laughs and calls the situation 'one of those light moments'. Calling it a light moment depoliticises the entire sleep-in story. 'Light moments' erases the red Mercedes' symbolism. Since the car was obviously more than an ordinary Mercedes-Benz, more than an object of desire, the logical move in retelling the story would be to move on to the heavier moments.

Several other incidents interrupt the film's story. Madikizela-Mandela, for example, interrupts the sleep-in strike story's homosociality. Through recalling how Madikizela-Mandela lays claim to the red Mercedes, Groom inadvertently draws the audience's attention away from the seamless narrative linking the car to the strike. Doing so accomplishes two things. It confronts the portrayal of Madikizela-Mandela as wry and domineering, and Mandela as the model subject of South African democracy. Groom's story would also have stirred discomfort among South African liberals, recalling Madikizela-Mandela's fraught role in the struggle against apartheid. As a figure, Madikizela-Mandela mars the queer limit of the sleep-in strike story. So the film takes action to direct the audience back to the significance of the red Mercedes.

The film pauses momentarily after the Madikizela-Mandela story. The pause is important because it illustrates how tangentially the other 'light moments' in the months leading up to the strike would be portrayed. During the pause, Philip Groom's name and the text from his interview disappear, two gusts of wind blow into the microphone, and all that remain are an image of an empty football field (empty, except for one onlooker) and the murmur of indistinct voices and other daytime sounds. Just as brief as Groom's mention of Madikizela-Mandela - signalling her fraught and contradictory place within the 'struggle against apartheid' narrative - two gusts of wind blow her away from the story and bring the viewer's attention back to the story of Mandela, the Mercedes and the strike. It is as if Groom made a mistake mentioning her, dwelt too long on the light moment, focused too much on gender and dissent, and drew too much attention away from what was important - the facts of the strike. For a moment I remember the Sulkowiczian bed, and then the film moves on.

The film pauses again when Tshete complains about how uncomfortable the sleep-in strike was because the group of all-male shop stewards needed to spend their days and nights together with other shop workers on beds they made from car seats. 'We are used to blankets,' he reminds us. 'So people started tearing up material to make blankets for themselves. And we slept in the plant. It was not a good thing.' As he describes the uncomfortable situation, the film draws our attention to innumerable white Mercedes-Benz vans stacked to the horizon, ready for shipping to the market. Together, the tops of the vans evoke the sleep-in strike beds. The image recalls the hundreds of men cramped together in makeshift beds on the shop floor. The film pauses just as the image eclipses the sleep-in story. The pause echoes Tshete's anxiety. When his name and voice disappear, all that remains are the sounds of insects trilling at night.

Why was the mass of shop stewards and workers sleeping together on makeshift beds not a good thing? Tshete offers an explanation. 'You must remember that in the morning you will not be able to wash. You will have to wash only your face and all that, so it was not good.' Would a more comfortable cycle of washing and striking have improved the situation? The answer is moot. What is clear are the ways the sleep-in strike made the men much more aware of their bodies outside their homes and inside the automobile plant.

Scholars of queer Africa are particularly interested in such pauses because they often lay the foundation for examining discarded archival materials. Unoma Azuah's research on the Area Scatter, for example, enables people to illuminate the fluidity of gender and sexuality in precolonial Igboland.16 While chiefs accepted Area Scatter's cross-dressing, the contemporary Nigerian state vilified the same queer subjectivities. For Azuah, discovering Area Scatter in the archives proved proponents of anti-homosexuality legislation wrong: gays and cross-dressers, Azuah argues, were part and parcel of Nigerian history, and were undoubtedly 'African'.

But Area Scatter left very few traces within the archive. Performers recreated the scene Azuah found there.17 In it, Area Scatter sings, plays music and dances for the chief in drag, receiving high praise. But the Area Scatter is still no more than a trace, susceptible to disavowal by Nigeria's national and religious elite. Little more than two gusts of wind could silence Area Scatter as an agent of history.

The audiovisual choreography in Gush and Cairns' film Red gives us some tools to treat archival traces as pauses.18 Replicating their choreography might move us beyond the queer limit of the sleep-in strike story, bringing us to new ends by more creative means. Like Area Scatter's dance in Azuah's archive, pauses offer opportunities for performing. While the pause in the strike narrative for Red's interlocutors served as an impasse to getting at the truth, I want to imagine one particular pause in the story as a coda, a place to add a solo performance. This, I argue, is precisely where the moment of queering arises.

Performing the Queer Question at 'Red Assembly'

While the film Red used pauses like the two I described above to smooth the edges that interrupted the sleep-in strike story, I want to dwell on a moment in the film's narrative that made me stop and think, and then say how my mental pause turned into a performance at the 'Red Assembly' workshop. This moment was the brief mention of Comrade Monqo. Mteteleni Tshete remembers Comrade Monqo as the Mercedes-Benz worker who introduced the idea of the sleep-in strike. 'You know, this thing of "sleep-in" was a new concept at the time. It was in fact raised by one of the workers, Comrade Monqo. Who's, who passed away now.' He adds, '[Comrade Monqo] raised this issue in the meeting of the workers to say that, we got a new weapon. We didn't know what this new weapon was. And then he raised this thing of "Today, we are not going to go home, we'll be sleeping here." And we say, "Hah?! Sleeping here?!"' Tshete remembers this with a confused look on his face. 'But we agreed, okay fine if that is now the idea, then, the sleep-in… maybe that's going to put more pressure to management. So, we slept inside the plant on that particular day. Obviously we are from our houses,' he explains, 'We are used to blankets, so people started tearing up material to make blankets for themselves. And we slept in the plant. It was not a good thing,' Tshete concludes, bringing us back within the sleep-in strike story's confines.

Tshete's discomfort with the strike's homosocial domesticity pushed Comrade Monqo to the queer limit of the sleep-in strike story and called the workers' bed-making 'a spontaneous decision'. Thirty years before, in Achmat's estimate, historians like Charles van Onselen relegated Jan Note aka Nongoloza to the fringes of queer memory. In the early twentieth century Nongoloza led the Ninevites or 28s prison gang, and instructed followers to initiate new members by having sex with them. In his biography of the leader, Van Onselen characterises Nongoloza as an eccentric child whose adult homosexuality thrived in the abject setting of South Africa's prisons. Achmat famously accused Van Onselen of homophobia and of completely mistaking the roots of Nongoloza's homosexuality. 'Since Van Onselen views homosexuality in the compounds as an undesirable form of sexual expression,' Achmat explains, 'he fails to unravel the relations between power, bodies and desires that emerged within the space of the compounds.'19 Achmat then called on historians to analyse same-sex desire through affect rather than discrete historical processes.

To introduce the critique of Van Onselen in essay form, interestingly, Achmat recounts his experiences as a political prisoner in the late 1970s. '[Prison life] was governed by the rules of the "28 Gang", or "Ninevites."' The 28s treated sex like currency, he explains, and sex between men and boys was closely monitored. Nongoloza's influence was clearly still in effect. Yet even in the midst of the prison's sexual economy, Achmat took a lover. 'We transgressed many of the taboos of the 28s,' Achmat remembers.20 Their relationship was more than 'situational homosexuality'. Rather than having sex for status, they desired each other because of their bodies, wit, and skills in giving and receiving pleasure. By perverting the rules of the prison, Achmat reveals incarcerating spaces as a place where men deliberately sought out and received sexual satisfaction. 'The compound represented a new space of desire, foster[ing] a number of practices including homosexuality.'21

I thought about what Achmat describes as the relationship between 'power, bodies, and desires', especially when we centre the bed as a theatre of work and play, as opposed to an object of struggle and abjection. For the 'Red Assembly' workshop on 28 August 2014, I wanted to use Gush's twisted, uncomfortable beds as inspiration to illuminate one particular space beyond the limit of Red - its queerness. I endeavoured to give a fictional account of Comrade Monqo's intentions behind the sleep-in. The day before the presentation, however, I panicked. Trained to research and write history, I realised I was moving into the dangerous territory of art-making: I wanted to perform, not just present. Moreover, while Nongoloza left a testimony in the archive, Tshete's story offered no evidence about how Comrade Monqo forged his 'new weapon'. My anxieties about creating a piece of art out of disparate traces and fragments took hold. I took a break in the middle of the workshop, went to bed and, when I woke up, re-read my paper and started making associations between words and themes, turning the presentation into a performance.

To open the performance, I reminded the workshop of Tshete's initial disgust over the sleep-in ('Hah? Sleeping here?!'), and remarked how so few participants mentioned desire and Gush's beds. What did gender and sexuality have to do with Mandela's car? I posed as the queer question. What did gender and sexuality have to do with the strike? Won't the beds draw our attention away from understanding the car and the strike together, bringing us closer to what Matt Richardson calls 'irresolution'? Precisely because no coherent narrative in the archive could support my vision of Comrade Monqo as a queer figure, I prefaced the performance as a collage in which I took bits and pieces of the story to set the stage.

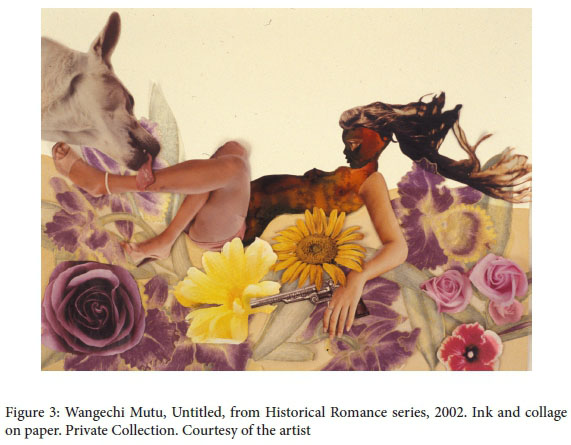

I also framed the performance around music and an image. Both were plays on the workshop's themes of art, history and the colour red, and both reflected what I hoped to accomplish by introducing performance, desire and beds. I showed Wangechi Mutu's Untitled, in Historical Romance series, for example, a 2002 collage depicting a Frankenstein-like humanoid figure reclining on a bed of flowers and enjoying a playful lick from a hound. The figure's hand rested on a revolver. I was drawn to the collage at first because it evoked the anxiety I experienced, realising I wanted to present a piece of art without ever having taken a studio art class. But as the time to perform approached, I decided I wanted to embody the figure. I relaxed, put down my arms, and prayed that the historical perversion I was to circulate before the workshop would not come back to bite me.

Stumbling over the Xhosa click, I riffed off Comrade Monqo's name in my English tongue and recalled that monks inspired the 'Red Assembly' workshop conveners to move Gush's Red installation from Johannesburg to East London. Having more familiarity with Thelonious Monk, I decided to use the 1968 album Monk's Blues as the performance's soundtrack. Like the scaffolding holding up Gush's beds, I played one of Monk's most famous compositions 'Ruby, My Dear' to bring red into the presentation. Then I introduced Monk's album and opened the set with 'Blue Monk' to change direction and lead the workshop to contemplate blue. There was a certain irony in playing 'Blue Monk' to celebrate Red. It is an upbeat composition born of a place of sadness and anger at war and racial inequality. The 1968 album could uniquely mix the reds and blues that the beds in Red illuminated. Every time I paused the performance, I played another portion of Monk's Blues. Slow, upbeat, slow, upbeat. Upbeat, slow.

I drew the workshop's attention to the two pauses in Red, the empty football field and the white Mercedes-Benz vans stacked on the horizon, and explained the rationale for the pauses. Then I deliberately departed from Gush and Cairns' audiovisual choreography in Red to further highlight their technique and went on to perform the pause that interested me most. I used Mutu and Monk to switch back and forth between colours to remind the workshop of Red's use of black and white. I played human-made music to distinguish the Monk soundtrack from Red's natural world soundscapes. Then I read Keguro Macharia's 'coming out' story and acted as if I were Comrade Monqo, the forgotten queer theorist of the Mercedes-Benz sleep-in strike. Seeing me as Macharia, as Monqo, resonated with Achmat's argument about the complexities of same-sex desire. And together, Achmat, Monqo, Monk, and Mutu importantly interrupted and opened up Tshete's testimony of the workers' improvisational, 'spontaneous' ripping up of car upholstery materials.

Only after playing a selection of Monk's Blues did I begin my role play. I wanted to bring Macharia and Monqo to the front of the stage. Macharia's words perverted the traditional coming-out story by expanding the queerness beyond sexuality, narrating a desire to know that dovetailed a desire for self-knowledge. I suggested that the homo- social weapon Comrade Monqo pioneered had long roots parallel to Macharia's, and I recited Macharia's words: 'Like many other book-reading people, my path into queerness was as much intellectual as it was libidinal.' In addition to religious texts condemning homosexuality, he remembers, 'the only other sources of information [about queerness] were my mother's 1970 psychology textbooks, which had nothing good to say about "the vice."'22 Achmat challenges Van Onselen on precisely this 'scholarly' framing of Nongoloza through 'unnatural vice'. 'Because he operates within the discourse of male homosexuality constructed by psychiatrists, missionaries and historians [as unnatural vice], Van Onselen conceals the significance of Nongoloza's statements on the sexual practices of the Ninevites.'23

By replaying Macharia's struggle to break through the association so often made between queerness and 'uncivilised vice', the performance marked the limits of Comrade Monqo's proposed method of resistance - that is, the men sleeping together on makeshift beds. Tshete remembers how the workers began stripping upholstery from K site and using the materials to make beds and blankets to 'make us sleep comfortable here'. In describing the event, Tshete also illuminates how improvisation could be one way to breach the limit Macharia faced. Tshete describes what improvisation on the shop floor felt like: 'Obviously we are from our houses, so it was not good.' But Macharia continues, journeying through queer theory's intellectual universe. 'A partial list of names [materialised]: Eve Sedgwick, John Bosworth, David Greenberg, Karla Jay, Diana Fuss, Kaja Silverman, Jonathan Dollimore, Judith Butler, Alan Bray, Alan Sinfield, Stephen Murray, Judy Grahn, George Chauncey, Jr.', Macharia explains, which again I recited, as Monqo.24

Macharia's story took listeners on the journey of Monqo, a declaredly 'African' queer scholar, who increasingly discovered their being out of place the more they witnessed the confines of queer theory and thought. '[Queer theory's partial list of names] created - or coincided with - other hungers for more familiar geographies', Macharia remembers, 'for the black and postcolonial, if not for the African.' Similarly, as he explored the relationship with his cellmate, born of desire and growing regular sexual contact, Achmat broke the 28s' rules, the prison's sexual economy. Achmat and his lover were troublemaking queers. For Macharia, 'it was the black and postcolonial [literatures and intellectual itineraries] that started making trouble.'25

Performing the coming-out story's wandering lines of flight between the black and postcolonial authors who affirmed Macharia's increasing self-knowledge, and a series of Queer Studies that negated it, revealed a Comrade Monqo who may not have been satisfied with the very same sleeping-in strike method he introduced. The film Red and the strike's struggle narrative would not have had the tools to make sense of Monqo the theorist, whose passion for queer epistemologies was as strong as it was fleeting. In the performance I never got through an entire composition of Monk's, nor was I able to play all the songs from Monk's Blues. Instead, I shuffled between songs, raised the volume and lowered it, and read over (and sometimes under) Monk's music - again, to reveal Achmat, Macharia and Monqo's self-discoveries as art-making.

While messy, the performance came together and connected the fragments that Red's beds set up for those onlookers who were interested in the various points where art-making met historical recreation. By deliberately recreating beds to tell the sleep-in strike story, Gush's artistic project illuminates Comrade Monqo as a trace, a subject of possibility. Macharia's narration depicts the queer subject as one who cannot claim personhood in varying African historical and geographic contexts. Comrade Monqo would have been a forever impossible trace if Gush had continued to remember the sleep-in strike outside the realms of performance and desire. 'If African studies is to learn anything from Foucault's History of Sexuality, it surely must be that a deeply genealogical method is needed to understand how certain figures become imbued with, and represent, the intimate anxieties of their geo-histories,' Macharia explains.26

So I began to conclude the performance by suggesting that students of the sleep-in strike look for other pauses in the story and its archive, and use them as sites of performance as opposed to ones of impasse. 'In an African studies still dominated by the importance of communitarianism and kinship, we might ask about the figures who fail to appear on genealogical trees and the figures who fail to repopulate those trees,' Macharia explains. Winding up my performance, I recited his further statement: 'Paying particular attention to how diverse communities organize their senses of self and community, confer personhood and status, we might look for those figures excluded from these designations.'27 I ended with a photograph of a friend, a queer scholar who frequently impressed upon me the unimportance of his work on gay Chicano artists. Sceptical of any positive reception a project on queer people of colour could receive in either the canons of Art History or Queer Studies, he moved between a deep passion for Lalo Ugalde, Hector Silva, Joey Terrill and Manuel Acevedo's artwork and an indifferent disdain for what people thought of it.28 Perhaps, similarly, Monqo did not want to be remembered. But as exploring the pauses in Red has shown, the trace of other unexpressed realities still gives an opportunity to imagine, and for creativity to make art.

1 For a general overview of the 'Africanness of homosexuality' debate, see M. Epprecht, Heterosexual Africa?: The History of an Idea from the Age of Exploration to the Age of Aids (Athens: Ohio University Press, 2008). [ Links ] For the most influential work on 'queer utopia', see J.E. Muñoz, Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity (New York: NYU Press, 2009). [ Links ]

2 For a general 'state-of-the-field' essay on Queer African Studies, see A. Currier and T. Migraine-Georges, 'Queer Studies / African Studies: An (Im)Possible Transaction?', GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies, 22, 2, 2016, 281-305. [ Links ] Also see C.C. Mavhunga, J. Cuvelier and K. Pype, '"Containers, Carriers, Vehicles": Three Views of Mobility from Africa', Transfers, 6, 2, Summer 2016, 43-53. [ Links ] This article is part of a larger intellectual move to meld Queer African Studies and African Mobilities Studies.

3 Thank you, Leslie Witz, for illuminating the presence of beds in South African museum historiography.

4 For more on queer studies' precarious place in US academe, see R. Ferguson, The Reorder of Things: The University and Its Pedagogy of Minority Difference (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2012). [ Links ]

5 The queer limit describes the point at which 'messy' subjects become 'the "constitutive outside" of what is understood, celebrated, and remembered' as the norm. M. Richardson, The Queer Limit of Black Memory: Black Lesbian Literature and Irresolution (Athens: Ohio University Press, 2013), 4. [ Links ]

6 There's a rich literature on 'play', but here I reference the Africanist literature on leisure. See L. Fair, Pastimes and Politics: Culture, Community, and Identity in Post-Abolition Urban Zanzibar, 1890-1945 (Athens: Ohio University Press, 2001). [ Links ]

7 E. Sulkowicz, ''My Rapist Is Still on Campus,'' Time, 15 May 2014. [ Links ]

8 S. Frost, B. Guthrie and M. Cunnane, 'Emma Sulkowicz, CC '15 [Columbia University, College class of 2015], to Mix Performance Art, Sexual Assault Protest', Columbia Daily Spectator, 2 September 2014.

9 Sulkowicz, ''My Rapist.''

10 Z. Achmat, '"Apostles of Civilised Vice": "Immoral Practices" and "Unnatural Vice" in South African Prisons and Compounds, 1890-1920', Social Dynamics: A Journal of African Studies, 19, 2, 1993, 95.

11 Ibid, 100.

12 Ibid, 95.

13 For Red (strike uniforms), see Image 5 of Gush's photo essay in this issue.

14 For Red (sleep-in strike beds), see Image 4 of Gush's photo essay in this issue and http://www.simongush.net/red-2/.

15 Ibid, 100.

16 U. Azuah, 'Resurrecting and Celebrating Area Scatter, a Cross-Dresser Who Transgressed Gender Norms in Eastern Nigeria' in Z. Matebeni (ed), Reclaiming Afrikan: Queer Perspectives on Sexual and Gender Identities (Cape Town: Modjaji Books, 2014), 23-7.

17 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=X8DYIDQh20Q.

18 Thank you, John Mowitt, for opening my senses to what, in the film, I now call 'audiovisual choreography'.

19 Achmat, 'Apostles of Civilised Vice', 98.

20 Ibid, 94.

21 Ibid, 105.

22 K. Macharia, 'Queer African Studies', Gukira blog, 24 August 2014, https://gukira.wordpress.com/2014/08/24/african-queer-studies/, accessed 9 September 2016.

23 Achmat, 'Apostles of Civilised Vice', 97.

24 Macharia, 'Queer African Studies'.

25 Ibid.

26 Ibid.

27 Ibid.

28 J. Estrada-Pérez, 'A (Re)Cartography of Desire: Imagining Decolonial Queerness and the Myth of "Mexican" Homosexuality', talk, University of Minnesota, 30 January 2015.