Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Kronos

On-line version ISSN 2309-9585

Print version ISSN 0259-0190

Kronos vol.41 n.1 Cape Town Nov. 2015

ARTICLES

Marriage, Science, and Secret Intelligence in the life of Rudyerd Boulton (1901-1983): An American in Africa

Nancy J. Jacobs

Department of History, Brown University

ABSTRACT

W. Rudyerd Boulton was a museum ornithologist in New York, Pittsburgh and Chicago who became a specialist in the birds of Africa, notably Angola. He participated in several expeditions to Africa and the Americas, but published little. With the onset of World War II, he joined the newly formed US intelligence and espionage agency, the Office of Strategic Services. He became head of the Secret Intelligence desk for Africa and was connected to the top-secret import of Congolese uranium for atomic bomb development. His postwar career remains largely classified, but in 1953 he was employed in a personnel office of the Central Intelligence Agency. Retired in 1958, he then moved to Southern Rhodesia, where he managed the Atlantica Foundation, an organisation of his own making, which appeared to have extensive funding of unknown origins. Boulton spent the rest of his life on his 'ecological research station', a farm outside Salisbury that he offered to American and Rhodesian scientists as a research base.

A retired CIA official who moved to Africa during decolonisation is inherently suspicious. Despite exhaustive efforts, Boultons continuing connection to Washington could not be documented. In fact, several indications - including his own managerial shortcomings - argue against the conclusion that he moved to Africa as a CIA plant. This paper provides an alternative explanation for his relocation, that it was the organic culmination of decades of self-construction effected through three marriages to accomplished women, two of whom were wealthy. Through his partnerships with Laura Craytor, Inez Cunningham Stark, and Louise Rehm, he developed into an expert on African nature, a liberal on American racial matters, and a wealthy patron of scientific work. Evidence of Boultons intelligence gathering may yet turn up, but for now the intimate politics of his life provides a better way to explain his relocation to Africa. Although American interests cannot explain his presence, his American origins mattered in that his African retirement was based on wealth, prestige and racial privilege gained in that country.

Keywords: Ornithology in Africa, decolonisation of Africa, the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), Rhodesia

'Wild Birds Call Couple to Africa: A 30-Year Dream' was the headline in the Washington Post in 1959.1 It told how Rudyerd Boulton had begun his career as a specialist in the birds of Africa and had taken several expeditions to that continent in the 1920s and 1930s. This field experience, the article reported, had qualified him for service with the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), the American intelligence agency during the Second World War. Since then, he had been 'shuffling papers' in the personnel office at the Department of Defense. Now he had taken an early retirement from the Pentagon to relocate with his wife Louise to the Rhodesias. Moving to Africa had been his dream for thirty years, he said. His hopes were to spend 'the rest of his life watching birds'. The relocation was sponsored by an organisation Rudyerd had created, the Atlantica Foundation. The article said nothing about Louise other than that she was Rudyerd's wife.2

The Boultons had equipped themselves splendidly, with a telescope, a bird blind, five cameras, a parabolic sound reflector capable of picking up bird calls from 180 metres away, a tape recorder, a four-ton truck, and a 5.5-metre air-conditioned house trailer ('caravan' in southern Africa) with a darkroom for colour as well as black and white film. The Washington Post included a photograph of the Boultons with their equipment. Another article with a photograph of Rudyerd and the parabolic sound reflector appeared in the Rhodesia Herald in May 1960 (Fig. 2). Here we learn that the equipment was not just for recreation but also for science. Boulton claimed: 'Thanks to the mobile laboratory, the whole of Southern Africa, from the Congo to the Cape, and from the Atlantic to the Indian Ocean, becomes a potential stage for scientific field work.'3 The Rhodesia Herald article introduced the Boultons to their new community. Just a few months earlier, they had settled on a farm near Salisbury, Southern Rhodesia (now Harare, Zimbabwe), which they called 'The Atlantica Ecological Research Station.4

Until decolonisation, Europeans with professional appointments in colonial administrations had generally been the authors of scientific research conducted in Africa. Imperial governments sponsored research and colonial officials used their assignments in Africa to pursue their research avocations. Lacking the sinecure of government support, American natural historians went to Africa as collectors of specimens or on museum-sponsored expeditions, but there were few of them and they did not usually stay long. By the mid-1950s, Fulbright and other American funding sources were changing the research landscape. For example, the largely US-funded College of African Wildlife Management in Mweka, Tanzania began to train National Parks personnel in the early 1960s. The creation of the Atlantica Foundation occurred during this expansion of American science in decolonising Africa. American science promoted US influence, even while operating well within colonial precedents.5

Still, something about this particular story niggles. What sort of birder needed a parabolic listening device to hear bird song? And what sort of a birdwatcher could afford such high-tech surveillance equipment? What would a civilian ornithologist with experience with the OSS do in the Pentagon? For that matter, what was the Atlantica Foundation? I talked to John Rehm, an attorney in Washington DC and Louise's nephew from her first marriage, who had helped with the couple's arrangements while they were abroad. I asked John, 'What did Rud do for the Department of Defense?' 'Well,' John said, 'Rud actually worked for what we call "The Company."' 'The Company' is, of course, the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA).6

In decolonising Africa, a hint of CIA involvement intensifies the political stakes exponentially. A CIA connection puts the Boultons' surveillance equipment, their move to Africa during decolonisation, and their intention of hosting American researchers in a different light. Field biologists count on being indulged for their use of surveillance equipment; their work provides good cover and some scientists have taken advantage of it for spying. The eminent Yale ornithologist Dillon Ripley had served in the OSS in India during the Second World War and admitted it publicly in 1950. In the insecure climate after partition, the Indian government saw fit to shut down Ripley's access to forests in border regions. In 1969 it further became known that a huge ornithological survey of the Pacific had provided information for US biological weapons research. Staff at the Smithsonian Institute had received military funding to track bird migration and collect blood samples. This news resonated globally. In India, popular opinion and the government became particularly suspicious of US connections, putting controls on Smithsonian funding of the premier ornithologist of India, Sálim Ali. Broadening our scope from field to laboratory science and turning to Central Africa, the connections between science and espionage continue: a CIA biologist was central to the plot to assassinate Patrice Lumumba, the prime minister of the Congo, in 1960. In this context, it is quite possible that Boulton's ecological research station could have been an outpost of US surveillance and espionage during the decolonisation of Africa.7

Establishing the relationship between Boulton, his Atlantica Foundation and the CIA has not been easy. Many files of the OSS are open at the US National Archives in College Park, Maryland, but those for the postwar operations of the CIA have been made public only in exceptional circumstances. I filed a request to gain access to Boulton's records under the Freedom of Information Act but was unsuccessful.

Turning beyond classified materials to the historical literature, we find nothing on Boulton. Spies and historians who have told stories about the Cold War in Central Africa have not drawn anyone's attention to him. Ken Flower, head of the Rhodesian Central Intelligence Organisation, names Irl Smith as the CIA representative until 1970 and never mentions Boulton. Larry Devlin, the CIA agent in Congo during decolonisation, gave an intriguing description of an inept older former CIA officer who joined him in the Congo. Devlin gave him the pseudonym 'Dad. I contacted Devlin, who told me Boulton was not Dad and that he had no information about him. Among spies, Flower and Devlin were exceptionally chatty and if neither of them had anything to say about Boulton's intelligence work after 1959 perhaps they were not privy to his status. Or perhaps there was nothing to say about a man who really had retired. 8

The Boultons' property now belongs to the Zimbabwe Parks and Wildlife Authority. In 2011 my search took me to his home in Harare. Today a sign on the Bulawayo Road directs traffic to the 'Boulton Atlantica Centre for Conservation Education', where the National Parks service received me graciously. His house now hosts administration and education offices. The research wing with laboratory, darkroom, and museum is mothballed, but Boulton's bequest stipulated that his library be public. It is now well maintained and receptive to visitors, but few come to use the outdated holdings. Unfortunately he left no provision to curate or store his personal papers. They had been deposited in closets apparently, with the contents of drawers turned over into separate boxes. The staff opened the closets and kindly allowed me to forage through these records of his life.

His papers in Harare include some unused CIA stationery with a 1953 print run, but beyond that the closets did not give up Boulton's secrets. Better evidence came in 2013, when declassified documents confirmed his employment with the CIA in 1953. It is now established that a one-time CIA employee moved to southern Africa during decolonisation. This is noteworthy: the CIA was active in the DRC immediately at the time of independence in 1960 and also in South Africa, where it played a role in the arrest of Nelson Mandela in 1962. Because its operations in decolonising Africa are still mysterious and a good lead is worth tracking, I have pieced together what I could about Boulton. The first step was to learn about him, his work, his politics, and his relationships before retirement. Whether or not Washington decided it needed a man in decolonising Africa, Boulton the man had been orienting himself toward scientific outreach in Africa for decades, with the help of his wives.9

The Three Lives and Three Wives of Wolfrid Rudyerd Boulton

Wolfrid Rudyerd Boulton was born in western Pennsylvania, in the city of Beaver, in 1901. He became an associate of the American Ornithologists' Union when he was still a boy. In 1913 the magazine Home Progress published a letter from him about his ornithological researches. It included a postscript from his mother Cora Marie, praising his conscientious and accurate work, and that of his brother too. The only hedge to her bragging was one that others who knew Rud later in life would understand: he and his brother were 'a little slow always about writing their answers promptly, for, in reading up for them, they reach familiar and favorite bits, and ramble on.' He attended Amherst College in Massachusetts, but received his Bachelor of Science degree from the University of Pittsburgh in 1924.10

Boulton had three careers. The first was from the early 1920s until 1942 as a museum ornithologist specialising in Africa. He did not publish much as a professional scientist, but his expeditions became known. His second career began in 1942, when he left ornithology and joined the newly created US intelligence agency, the OSS. After the war he remained in Washington with the CIA. Retiring (overtly, at least) from government work in 1958, he took up his last career, as director of the Atlantica Foundation, which was most active in the early 1960s. As it diminished and as he aged, he stayed in Africa and died in liberated Zimbabwe in 1983.11

An attractive, generous man with an inquisitive spirit (see Fig. 3), Rud also had three marriages, closely corresponding to his three careers. His wives were all accomplished women and two had the added resource of wealth. In 1925 he married the ethnomusicologist Laura Craytor, from whom he separated in late 1938. He married the Chicago heiress, poet, arts patron, and self-proclaimed psychic Inez Cunningham Stark in 1942. She died in 1958 and in 1959 he married again, to Louise Rehm, a wealthy widow from Washington DC. In Salisbury, Louise took up volunteer work, travel, and managing the foundation. She died there in 1974. Fortunately his wives left a deeper impression on the historical record than he did. Boulton's propensity toward marriage multiplied what we know about him.

These women are more than mere sources for a man's career as a spy and scientist. Each of them led lives of purpose and, in pursuing their avocations, they fostered Rud's development. The Washington Post article credits Rud with the establishment of the Atlantica Foundation, but his wives established Rud. For more than thirty years preceding his move to Africa, he was practically handed off between them. If we want to make sense of Boulton's move to Rhodesia, the intimate politics of his life turn out to be as important as those of the Cold War and African decolonisation; he was a product of these partnerships as much as he was a scientist or an intelligence specialist. Whatever assistance or encouragement he received from the CIA in 1959, his African retirement was an organic culmination of his decades with Laura, Inez, and Louise.

This is a history of the macro-politics of mid-twentieth century relations between Africa and the US on one hand, and the micro-politics of a handful of well-off white Americans' work and relationships on the other. The conduits that draw together these different scales are the Boultons' race, their wealth, and the prestige offered the American elite in the mid-twentieth century. A straightforward Yankee disposition helped them navigate past social hierarchies, if they so chose. American capitalism bequeathed them comfortable lives with foreign travel, exquisite things, fine food, and plenty of hired help. Their culture of capitalism included philanthropy and the Boultons took part in this practice, both as recipients and patrons. From positions of privilege and affability, they actively engaged the world, turning up in places where people of their kind were exceptional: colonial Africa, the South Side of Chicago, white-minority-ruled Rhodesia, and independent Zimbabwe. They were relatively liberal about the removal of racial barriers, but not inclined to criticise structural impediments or cultural hegemony.

But even this small and tightly connected group was not homogeneous; wealth and whiteness can be only broad explanations for their dispositions. Variations in the orientations of Rud, Laura, Inez, and Louise were significant, as was Rud's trajectory through changing times. Their evolving responses to American civil rights, Central African multiracialism, southern African white minority rule, and African nationalism - always against the background of fluctuating wealth - create the critical contingencies in this history. Drawing attention to their actions is not to suggest that the developments explored here can be explained as the outcome of personal conviction and choices. A history of intimate politics is not the same as one of individualist agency. What follows here is not a story of Rudyerd Boulton's achievements, or a feminist retelling of a man's accomplishments. My point is that the affordances bestowed on all the Boultons allowed them a unique range of self-constructions and social positions, in both the US and in Africa. Under these circumstances it was possible to do unexpected things. One could explain the Boultons' presence in Rhodesia as an expression of American interests in political and scientific domination, but the route to those outcomes was through micro-political paths.

My investigation into Boulton's life began with the hopes of uncovering a CIA plant, but this history revealed a different lesson, that through the inspiration and support of his wives, and many special benefits, a mediocre scientist and paper-shuffling bureaucrat could devise a personal project so grand that it could be taken for a US government initiative.12

Ornithological Expeditions and Laura Craytor Boulton

The ornithology department of the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) in New York hired Rud as an assistant to the ornithology department by 1924. Around that time he began courting Laura Craytor, an Ohio girl and a graduate of Dennison University, who was working as a research assistant in genetics at the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory on Long Island. In her free time Laura sang in choirs. They married in 1925 and agonised about being apart when he made his first trip to Africa as the ornithologist on the AMNH Vernay Angola Expedition. In 1926 Rud found permanent employment as assistant curator of birds at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History, and so the couple moved to Pittsburgh.13

Rud's experience qualified him to lead collecting expeditions. In 1929 the Carnegie Museum gave him permission to participate in another AMNH venture, to Nyasaland, Uganda and Kenya, financed by Sarah Lavanburg Straus of the family that owned Macy's department store. Mrs Straus (a 68-year-old widow) and her grandson accompanied him. Laura also came along, bringing along her own collecting equipment; for her, this was wax cylinders for recording music rather than a shotgun to kill specimens. The Boultons also used the equipment to make the first-ever recordings of Afro-tropical bird calls. The benefactors departed from Kenya, and Rud and Laura continued their travels to Cape Town on an expedition for the Carnegie Museum. They returned to Africa again for the Carnegie Museum Pulitzer Angola Expedition of 1931. On that trip, which included its sponsor the publisher Ralph Pulitzer, Rud named a species for Laura, Phylloscopus laurae, known in English as Laura's (or Mrs Boulton's) woodland warbler. Neither Laura nor Rud came from money, but through museums they connected with wealthy patrons. It must have been tremendous fun for a young adventurous couple.14

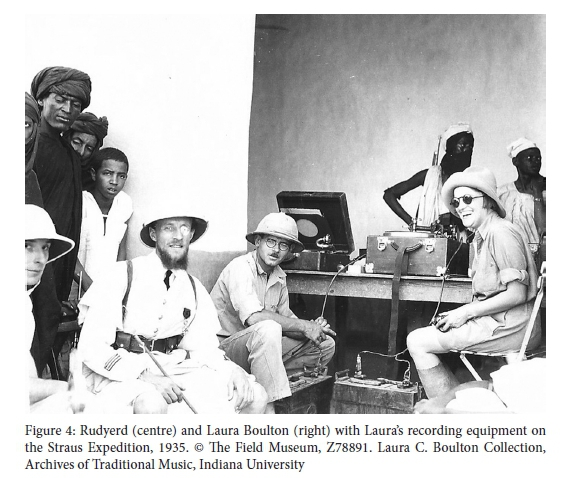

In 1931 Rud found a better position, as curator of birds at the Field Museum in Chicago, and the couple moved again. Rud wrote a book, an illustrated explanation of bird migration for children, Traveling with the Birds. Laura registered as a graduate student at the University of Chicago. Until then, her musical research had been a personal pursuit while she accompanied her husband, but now the Carnegie Corporation funded the purchase of better recording equipment and in 1934 Sarah Straus underwrote another expedition, the first to provide explicit support for Laura's musical research. Aged 74, Mrs Straus again joined the party, which travelled 12,900 kilometres from Dakar through the Sahel to Nigeria and Cameroon. Photographs from the 1934 Straus Expedition convey a companionable marriage with the adventure and status available to white travellers in Africa (Fig. 4). On this trip Rud again collected bird specimens, but Laura's work had become equal to his. She contracted an agent and tried the lecture circuit.15

Laura claimed expertise on Africa; what did that continent mean to her? The early chapters of her 1969 memoir The Music Hunter recount her movement through Africa. She describes landscapes and wildlife (birds figure prominently), and provides historical background. The book was a travelogue more than a discussion of society and culture. Africans come across as subjects of kings and members of tribes who had rituals, musical instruments and an innate artistic sense. She admired the 'forceful, free melodic outlines and rhythmic complexities' of the music she recorded. Rule by Europe did not attracted comment.16

Laura never completed the doctoral requirements of the University of Chicago. After 1936 she travelled, without Rud, to London, Paris and the West Indies. Their surviving correspondence conveys some stress and their hopes to overcome it. They wrote to each other with news of their friends, including Inez, who gave Laura professional introductions and personal support. It was a problem that her lecture fees could not be counted on to cover her travel costs. In late 1938 the Boultons separated and Laura moved to New York City. Laura and Rud fell out of touch, apart from the transfer of US$100 alimony every month. Of Rud and his three wives, Laura is the best remembered today. She is recognised as a founding figure in the field of ethnomusicology, an important collector of the world's musical heritage, if perhaps self-promotional and not very analytical. Laura remained single for the rest of her life and died in 1980. Her memoir made no mention of Rud or even that she had been married.17

The Intelligence Service and Inez Travers Cunningham Stark Boulton

During the Second World War, US intelligence officers and agents were well educated and often had overseas research experience. As specialists on Greece, for example, the OSS recruited archaeologists. Anthropologists provided the Agency with analyses and information gathered in India and all regions of Africa. We have seen that the ornithologist Ripley worked in South Asia. In fact the Agency used two ornithologists for its Africa work: Boulton and his friend James Chapin, the specialist in the birds of the Belgian Congo at the AMNH. Chapin took up a post in Leopoldville as the official OSS representative to the Congolese government. He reported to Boulton, who held the title of Divisional Deputy for Africa in the Secret Intelligence Division (SI). In 1943 Boulton was additionally made the 'desk man' for a joint programme between SI and the X-2 (Counter Espionage) in Africa.18

The history of the OSS in Africa has not been written. Its archives, which have been selectively declassified since 1980, reveal that the organisation monitored and took action in many places. The greatest US interest in sub-Saharan Africa was the procurement of Congolese uranium from Shinkolobwe mine in Katanga for the Manhattan project and ultimately the 6 August 1945 bombing of Hiroshima. Boulton would have been informed about its strategic importance by late 1942, when his subordinate Chapin was deployed to Leopoldville. Declassified OSS archives do not provide much detail about Congolese uranium, but it may have been possible to convey information about the element without mentioning it by name. In January 1943 Chapin wrote Boulton a two-page letter under the subject line 'Possible Sabotage to Congo Copper Carriers'. The interest in copper is puzzling. The United States and other countries in the Americas had extensive and known reserves of the metal. What could motivate Chapin to write in detail about Congolese copper production and sabotage against it? Possibly that it was from Katanga, also the site of uranium mines, and that the word 'copper' could serve as a plausible stand-in for 'uranium' in correspondence that might be intercepted.19

A biography of Boulton's subordinate on the Africa SI team, Adolph Schmidt, gives specifics of OSS activity around Congolese uranium. Schmidt had been tasked with uncovering the smuggling of industrial diamonds from Angola to Axis countries. In January 1944 he was ordered on a top-secret mission to the Belgian Congo, to monitor shipments of uranium from Katanga. He was to facilitate delivery to American freighters and make sure none of the ore was siphoned off en route. Schmidt told his biographer: 'I knew nothing about uranium except that it was a radioactive element, but what could that have to do with World War II?' Seeing two freighters lying off the port of Matadi at the mouth of the Congo River put his doubts to rest. 'Now one freighter anywhere on the west coast of Africa at that time was an event, but two freighters, one loading and the other waiting - something important was going on.' Unlike Schmidt, Boulton never went on record about his OSS experiences. He seems to have travelled overseas only once during the War, to North Africa in 1944.20

After the War the OSS was disbanded and reformed as the Strategic Services Unit (SSU), a precursor to the CIA. In February 1946 Boulton was still in the position of head of the SI Africa division. He resigned from the position of curator of birds at the Field Museum, explaining only, 'The work that I am doing and have been doing in Washington is unfinished and no one, literally, can tell when it will be... I firmly believe that the activity in which I am now engaged is the most important thing that I can do for the welfare of our country.'21

Rud married Inez in 1942 when he moved to Washington. His employment with the federal government was nearly conterminous with his marriage to her, the only one of his wives who never went to Africa but may be the key to his Atlantica vision. A poet, psychic and rail-thin socialite, Inez Travers was born in 1888 to a wealthy Chicago Catholic family. She went on tour to Europe, including Vienna, where she was reportedly analysed by Adler. In 1916 she married Howard Cunningham; the Tribune ran a sketch of the bride (Fig. 5). In Chicago the couple lived in a grand apartment building on Lake Shore Drive. Cunningham committed suicide in 1932. Inez married again in 1934, to the writer Harold Stark, and divorced a few years later.22

Inez flits through histories of bohemian pre-war Chicago as an 'eccentric society matron' (Fig. 6). She gave parties attended by painters, poets, dancers and writers. She was an American early patron of a few European modernists and was friends with leading mid-western modernist artists. She published in Poetry and was a reader for submissions.23

Inez was also a spiritualist. She wrote a pseudonymous memoir about her gifts: Beyond Doubt: A Record of Psychic Experience. (Ever the aesthete, her nom-de-plume was 'Mary Le Beau.) Communicating with a spirit guide called Trust who coached her through life, at first she used an alphabet board but later developed the skill of automatic writing. He guided her to an understanding of a higher plane, where the truths of Christianity, reincarnation and evolution intersected. The author's current husband 'Bob' was of a scientific mind but was also open to Trust's messages.24

The art of Africa and by African Americans was a specific interest for Inez. Partygoers found African sculptures in her bathroom. Several biographies of African American artists mention connections with her. In 1941 and 1942 she taught a poetry class to African Americans at the South Side Community Art Center in Chicago, an organisation funded by the Works Projects Administration. Her most famous student, Gwendolyn Brooks, the first African American Pulitzer Prize winner, began studying poetry with Inez at the age of 23. Brooks recalled Inez fondly:

She did not care to be regarded as a teacher, but as a friend who loved poetry and respected our interest in it. I can see her now, tripping in, slender, erect, and frosted with a fabulous John Fredericks hat, which was as likely to sport vegetables as fruits, flowers or feathers. Her arms would be loaded with books. Books from her own beloved library, to be freely loaned to any member of the class who wanted them. Or books especially purchased for the occasion, because of some point she wished to stress or introduce. Once she gave a Poetry subscription to every one of some fifteen members of the class. These books she would put down on the long table. She was one of those women who know how to combine friendliness with good will with easy modesty and dignified discretion.25

The two remained in contact after Inez's move east, when Inez arranged for a reading at Howard University, the country's leading historically black institution of higher learning, in Washington DC, and introduced Brooks to the publisher Harper & Brothers.26

Inez's agenda, seeking out black poets to cultivate their talents in what she thought was a universal medium, was classically liberal. There is no indication that any of the Boultons ever supported civil rights in a more pointed way, by joining the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, but Trust told Inez that her questioning of racial hierarchies led him to choose her as his channel: 'You consider women of all races and creeds your sisters. No superiority toward them, and an interest in their welfare.' Inez did not always understand what this meant in practice: in New York, when Brooks was not allowed to freshen up in Inez's room at the Barbizon Plaza Hotel in New York, Inez was led to wonder aloud to her friend if she should have refused to stay there, but she did not.27

As for Rud, further confirmation of his CIA career appears in a handful of documents released through the Freedom of Information Act. They give his title in 1953 as Executive Secretary, CIA Career Service Board. The 1959 Washington Post article is corroborated: he did work in personnel, but in 1953, at least, it was with the CIA, not the Department of Defense. In seven years he had gone from work he considered 'the most important thing that I can do for the welfare of our country' to what he referred to in the Washington Post article as 'paper shuffling'.28

He retained connections with ornithology. He remained affiliated with the Field Museum as a research associate. He sometimes wrote to colleagues there about his intention to return to the study of the birds of Angola. In later years Rud told of two further ornithological expeditions to Africa, the first to North Africa in 1952, but I have not been able to find evidence of this expedition. Inez or the CIA may have funded it. The second was to Southern Rhodesia and Angola with the Field Museum in 1957. This was his first trip to southern Africa since 1934.29

In 1957, Southern Rhodesia appeared to be firmly connected to the new Central Africa polity known as the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland, a state that both empowered the white minority and purported to be based on multiracial 'partnership'. A white American liberal might not have noticed that partnership was more a performance than a principle. The Federation's 'progressive' politics in the mid-1950s were defined by the Capricorn Africa Society, which aimed to remove the colour bar and 'all types of racial discrimination' even while seeking 'to make effective the moral, cultural and spiritual standards of civilization and to help all members of all races to attain these standards'. More to the point, the Federation gave white settlers in Southern Rhodesia access to resources and capital in Zambia and to labour from Malawi. The arrangements for a disproportionately small Africa representation in legislatures were byzantine and increasingly used to make the case that rule by a qualified minority was a legitimate form of decolonisation. (African nationalists disagreed!)30

The eradication of a colour bar and Capricorn's affirmation of universal standards would have appealed to Rud and Inez, who valued science and up-to-date poetry. Neither Inez nor Rud left any indication of their thinking in 1957, but we can speculate. The trip to Southern Rhodesia could have germinated the idea of a move to Africa. If they wanted to retire on that continent, Southern Rhodesia would have been an appealing prospect: the white-minority government of 1965 was not yet on the horizon and, compared with the bald segregation of apartheid South Africa, the violence and reprisals in Kenya and the black nationalism in Ghana, the Central African Federation could have struck wealthy white American liberals as a reasonable arrangement. Think, too, of Rud's boredom and disappointment to find himself in a personnel office. What a way to end a career that had begun with expeditions and birds! Inez's inherited wealth made a different life possible.

Rud quit his government position in April 1958 and Inez died in August. Her library went to Howard University. She left her wealth to Rud. Should any not be used in his lifetime, she asked it be bequeathed to 'a suitable organization for research in the field of parapsychology'. Her most interesting legacy may have been as a guiding light for an educational outreach programme in Africa. This would be appropriate for a woman who believed she could communicate with the recently departed.31

The Atlántica Foundation and Sarah Louise Super Rehm Boulton

In February 1959 Rud photographed Louise Rehm, looking relaxed and happy (Fig. 7). They married in April. Like Rud, Louise was recently widowed; her husband, Lane Rehm, an OSS veteran and a friend of Rud's, had also passed away in 1958, a month before Inez's death.32

Of all the principals in this story, Louise left the faintest paper trail. Her nephew by marriage, John, told me she had not been to college and she had been a lead buyer at a major department store. Friends in Zimbabwe recalled her as bright and cheerful, but reserved and even delicate. She is remembered as a 'fantastic' cook. Her letters from Rhodesia are written in a light and chatty tone. What I have learned about Louise's early life came from tracking down her first husband. Lane Rehm had had a previous marriage that ended in 1926. That same year he married Sarah Louise Super, who had been born in 1897 in Pennsylvania.33

Lane worked in finance, for the major investment firm Brown Brothers Harriman. He did well enough for himself - even after the 1929 Wall Street crash - to retire in his forties and dedicate himself to painting. Wealthy and disinterested in acquiring more money, he was considered incorruptible and so when the Second World War began he was deemed qualified to supervise OSS finances. Their home became a retreat for OSS personnel; Louise's cooking was appreciated. In 1948 the Rehms were in Paris, where Lane worked for the US embassy; Louise was said to have attended the Cordon Bleu culinary school there. In the 1950s they were living in a fine house on R Street in the Georgetown section of Washington DC.34

Just a few months after they were married, Rudyerd and Louise Boulton legally established the Atlantica Foundation. This was a non-profit, tax-exempt corporation empowered to work and acquire property anywhere in the world.

Atlantica's mission statement was ambitious. Science, fine arts and parapsychology are all in its brief and it claimed worldwide scope (Africa is not mentioned):

• To establish, conduct, maintain and support scientific, literary and educational institutions;

• To aid, carry on, conduct and foster, in any part of the world, education investigation, research and publication in the fields of the arts, sciences and humanities, including but not limited to ecology, zoogeography, systematics, and parapsychology;

• To stimulate, teach, train, aid, guide, counsel and advise scientists and/ or artists in research, creation, performance and/or publication in the various branches of the natural, physical and social sciences and in the liberal, useful, graphic, applied and fine arts;

• To conduct lectures, exhibitions, public meetings, conferences experiments and studies intended directly or indirectly, in whole or in part, to advance the arts, sciences and humanities;

• To make collections of natural or man-made objects, specimens, books, pictures, sculpture, instruments, or other artifacts of the animal, vegetable or mineral kingdoms which may enhance, or contribute to, the development of the arts, sciences and humanities.35

Its educational outreach is reminiscent of Inez's teaching with the South Side community arts center.36

By February 1960 the Boultons were on a farm on Saffron Walden Road near Lake McIlwaine (now Lake Chivero), about 25 kilometres from Salisbury, a property with rock paintings and iron age smelters. They expanded and renovated the house on mid-century modernist lines (Fig. 8). A guest at Atlantica recalled:

Manicured lawns, flowering bushes, and well-tended flower beds greeted us as we followed the curving drive up to a rambling stone building with a residence wing, a living wing, and a laboratory wing. Books, reprints of scientific and art research papers, magazines, and art lined every passageway and crowded every room. Had we arrived at the public library or the Museum of Modern Art?37

It would have seemed a good life to the Boultons. Politically palatable and paying good dividends on whiteness, Southern Rhodesia offered a critical mass of upper-middle-class residents who cared about art and birds. Again, Louise gave parties, with fancy cooking. Her early letters show her joining in Rhodesian society without critiquing it. She shared anecdotes about learning Fanagolo and about the 'garden boy' doing the work while she stood nearby 'supervising'.38

The meltdown in the Congo in mid-1960 prompted Atlantica trustees to express concern about the Boultons' situation. Rud responded uncharacteristically by putting his political opinions on paper: he said government action had precipitated an 'anti-white feeling'; Africans were justified in protesting. Still, he believed that order must be restored in the shortest possible time. Like many others in southern Africa and the United States, he criticised the lack of democracy and upheld the legitimacy of the order imposed by it. At any rate, by 1960 African nationalist opposition had made multiracialism and the Federation moot.39

On their arrival the Boultons took on a range of projects in support of the arts, education, scientific research and conservation. Both the Rehms and the Boultons had collected fine art and they used these items to introduce themselves and Atlantica to the white community in Salisbury. In December 1960 the Rhodes National Gallery put on an exhibition of their collection, which included several paintings by African American artists, many from Howard University.40

The Boultons also supported education. Atlantica provided equipment for science classrooms for Nyatsime College, a private secondary school near Harare. They also paid fees for individual students. Louise became the organiser for Books for Africa, a scheme to provide new, donated textbooks from American publishers to African schools. By 1964 she and volunteers had distributed 20,000 books to more than 100 schools and libraries and had offered introductory courses in library science at Ranche House College, a private tertiary institution in Harare. Books for Africa was a programme of the African American Institute (AAI), a non-profit body in New York City founded in 1953 with the goal of fostering good relations between the US and citizens of new African nations. The chairman of the AAI board was Harold Hochschild, who was also chair of AMC, a corporation with major holdings in Zambian copper. It later emerged that the CIA was financing the AAI.41

The Boultons were well connected with the American community in Salisbury, including the consulate. These relationships suggest another possible continuation of a CIA connection. Elizabeth ('Bicky') Tatum volunteered with Louise at Books for Africa and the AAI. Her husband Lyle worked as a peace activist with the American Friends Service Committee from 1960 through 1964. Through his work, Lyle was friendly with the political leaders Joshua Nkomo, Robert Mugabe and others. When the Boultons and Tatums visited, Lyle and Rud had long conversations about Southern Rhodesia's prospects, speaking freely as companionable fellow Americans. Although Boulton was not closely connected to African nationalists, he would have been able to follow them through Tatum. Whether he channelled what he learned to Washington, we do not know.42

Science and conservation occupied Rud. With the establishment of Fulbright Fellowships after the Second World War, American scientists were initiating research on African wildlife and he seems to have had this model of visiting scientists in mind. A handful of American and Rhodesian researchers did make Atlantica their operations base. In 1962-1963, Rud also threw himself into efforts to protect what is now Lochinvar National Park in Zambia. However, Rud did not foster scientific specialization for talented underrepresented individuals, as Inez might have done. Angelo Lambiris could recall only one black student spending time at Atlantica.43

And with their mobile laboratory, the Boultons travelled. In 1961 they covered a good 9000 kilometres on two road trips, to the Kalahari and Tanzania. Trips continued in 1962 and 1963, when Louise reported Rud gone for two months, 'photographing whatever they see to photograph, and digging up other things as well'. Rud always took his listening equipment on his travels. Lambiris, who began his specialisation in herpetology at Atlantica, recalled that the parabolic reflector was a one-of-a-kind retrofit of a meteorological device, with a microphone rather than an antenna. The tape recorder was a top-of-the line Nagra. Rud made recordings of bird calls which are now held in libraries and museums in the US and South Africa. He also had, Lambiris recalls, a Second World War-era prismatic compass, used in surveying, and was an excellent mapmaker. Of all Atlantica's activities, Boulton's travel through Rhodesia and other territories is the most suggestive of a CIA connection.44

Paying for all this required planning. It has been impossible to reconstruct whether Atlantica and the Boultons benefited any CIA seed funding. If the Agency did contribute, it was not sufficient to cover costs. In 1960, the year Atlantica purchased the farm, Rud made a loan of US$50,000 to the Foundation and Louise mortgaged her house, but how she used her capital is not recorded. Atlantica did not pay the Boulton's interest and they did not pay rent on the house. For further expenses, rather than expend too much capital, Rud financed by borrowing 'very extensively'. He wrote to his former OSS subordinate and Atlantica board member Schmidt about the burden of keeping up with interest payments from his personal income. Schmidt was a son-in-law in the Pittsburgh Mellon family and after the War he became president of a family charitable trust. He made at least three US$1000 donations to Atlantica and pleaded with Rud to apply for Foundation support.45

Rud wrote back with promises to do so, but he cashed in on Inez's art collection instead, shipping 13 paintings to Sotheby's in London. Kandinsky's, 'Ludwigskirche in Munich' (1908) sold first for £12,000, which came to US$33,600. Rud did not inform Schmidt about the disposal of the remaining paintings, including one of Paul Klee's letter paintings (it was an upper case 'E'), a nude by Chagall, and a 1905 print by Picasso called 'Salome and Herod'. Atlantica never received Foundation support and contributions from individuals were mostly less than US$100. By no means were the Boultons impoverished: a handwritten calculation by Rud put their combined assets in 1969 at US$292,356. Adjusted for inflation, this would be around 1.9 million dollars in 2015. It is a lot of money, but Rud estimated that in ten years they had 'lent' more than a third of their wealth to Atlantica. The financing troubles suggest that Atlantica could not count on the CIA for its bankroll.46

Another challenge was Rhodesian politics. In 1963 Rud addressed the upsurge in white radicalism, which put foreign researchers off. Even after the Unilateral Declaration of Independence (UDI) in 1965, the Boultons retained faith in the political process and the security apparatus. Louise tried to soothe American friends' nerves:

Most of our friends have written and feared that Rhodesia would go the same way the Congo did. Rud and I feel there is no possibility of that happening in the country. Also there is probably no possibility of anything similar to the Kenya Mau Mau because the country is so much more open, and Rhodesia has a tremendous police force.

Matters became more difficult in 1967 when the US imposed sanctions. Rud began to consider contingency plans for the station, including dissolving the entire Atlantica Foundation or affiliating with an American museum or university. But no connections materialised. Invested in Rhodesia, the Boultons stayed and so Rud, a liberal with connections to Howard University, became ensconced in minority-ruled southern Africa. He had moved some distance from Inez.47

As UDI made the place less conducive for foreign involvement, international contacts faded. Rud cultivated the networks available to him, in the white naturalist community. The Atlantica Foundation became a supporter of the Association of Scientific Societies in Rhodesia. He served as managing editor of the Rhodesia Science News and later was president of the Rhodesia Scientific Association. The station also hosted school fieldtrips and received official permission to include 'non-Europeans'. Gradually, the Foundation receded and Rud acted more and more as an individual in Rhodesian science and environmental organisations. The newsletter ceased after 1967 and the board in the US held no meetings between August 1965 and February 1969. By the end of the 1960s, Atlantica was much less than the grandiose vision of ten years before.48

UDI, finances, and ageing all diminished what Rud could achieve, and he characteristically had trouble keeping up with tasks too. His birder friends in Rhodesia noticed his poor executive functioning. His personal retirement plan had been to write the definitive book on the birds of Angola but he never did. As his friend Alex Masterson put it in Rud's obituary:

The man was a perfectionist, but this trait so consumed his work that it smothered much of his potential out of existence. If there were three ways of tackling a problem Rud would find a fourth and more difficult way because the outcome might have been a little bit more satisfactory: if something could be said in two minutes Rud would say it in ten minutes but he would have had something to add.

Rud was, Masterson said, 'forever being sidetracked'. Lambiris described him as 'almost fanatical' about detail.49 Careening between attention deficit and hyperfocus, his impracticality shines some light on what we know of his federal career. In 1946 he was working in Secret Intelligence. By 1953 he was in the Personnel Office. Could his work habits have caused a transfer from cloak-and-dagger to paper shuffling? Would the CIA have entrusted this distractable retiree with strategic work?

Rud was loath to talk politics. He did not discuss his options as they narrowed and Rhodesia moved right. If the Central African Federation had been attractive to him as an American liberal, post-UDI Rhodesia under minority rule would have held less appeal. During my 2011 visit to Zimbabwe, I interviewed people who remembered the Boultons. I was always told that Rud was a private person who rarely discussed politics. All the same he and Louise were considered liberal on racial issues. Whatever their private politics and personal preferences, they had the legal and social status of whiteness and the further advantage of having been heirs of American capitalists. On a camping trip in 1970, Rud told Alzada Kistner and her husband Dave, an entomologist from California, stories of Ralph Pulitzer bringing a butler and Sarah Straus a maid to Africa, but Alzada felt she was on a 'safari from another era', with furniture, fine china, gourmet cuisine, classical music on the tape recorder, and pressed linens laundered daily. Four servants attended to the campers while other members of the household staff remained at home. Atlantica also kept a white woman on the payroll as a secretary. With the ability to command service and respect in a new country, Rudyerd and Louise Boulton are prime examples of the global mobility of privilege in the mid-twentieth century.50

They must have made peace with living under the minority government. Nature would have made up for problematic politics (Fig. 9). Rud was dedicated to research on the Atlantica property. Soon after his arrival, he hired a surveyor to set up permanent marker beacons over his property at intervals of 100 metres. With this grid and his prismatic compass, Atlantica was subjected to extremely close surveillance for the production of ecological intelligence. Researchers published on bats, termites, bacteria, beetles, reptiles, soil and the ecology of the nearby lake. A bush fire in 1978 destroyed most of the natural vegetation; this, for Rud, was a research opportunity and so he and Lambiris, the herpetology specialist, tracked the regeneration of plants and animals for the next two years.51

A 1968 New York Times feature portrayed Rud as a 'chipper' eccentric with a dream of raising termites as a dietary protein supplement. Termites are an established food source in Zimbabwe. Rud's grand vision for improved nutrition tapped into vernacular practices, but he did not have much luck capturing or raising termites. 'We can keep ourselves busy for untold years without going a mile from this place,' he said. 'We haven't done a stroke of work for years... It's all been fun.'52

That was actually not true. Louise suffered a degenerative cognitive condition that seems a lot like Alzheimer's disease. Kistner conveys Louise's decline into senility in an account of her 1970 visit to Atlantica. She was only sometimes lucid and Rud coped with the help of servants, including Wulalani Banda and Mendoza James, a chef in a tall white hat who had learned her recipes and ran the household.53

In 1971, Rud explained that Louise's condition served to keep them in Rhodesia:

Louise says that she is, and she appears to be, more contented in her own home here at Atlantica than anywhere else that we can think of. Her personal surroundings, furniture and possessions of a life time, her close friends and neighbors that drop in to see her from time to time, her dog, and relatively unlimited friendly and well known servants and maids all contribute to her peace of mind. I think it would be pointless to uproot her and for us to return to America where we no longer have any property or fixed home of our own.

In 1973 the Kistners returned and found Louise incoherent and under 24-hour care. At the end she also became blind. She died in August 1974. Her will named Rud as her only heir. He grieved deeply at her passing.54

Widowed again and in his seventies, Rud decided not to go back to America. Staying for the end of Rhodesia might seem like an insecure prospect, but for Rud it was possible because of the people in his circle - the scientists, birders and servants. Being Rud, he sought out female companionship. His peers indulged him. Others, especially younger people, found him an inspirational, luminous teacher. Alzada Kistner was 'enchanted' by his stories. Lambiris recalled: 'His knowledge of zoology and botany across the board was phenomenal... He taught magnificently, so that it was all one never-ending adventure, full of excitement and wonder'. Rolf Chenaux-Repond remembered him warmly: 'Rud was generous, supportive, enabling, humane'.55

Rud's Washington connection and the privileges of wealth and race were sufficient to raise suspicions in Rhodesia. I heard from Lambiris that the Rhodesian Central Intelligence Organisation quizzed him about Rud's career with the CIA. When I was in Zimbabwe, I heard about a mysterious account at Barclays bank in Harare held in the name of the US Audubon Society. It turned up a good decade after he died and did not have any obvious connection to Rud. But Alex Masterson, a leading birder who also had served as the Boultons' local attorney, recounted, 'Money plus America plus birds; that spelt Boulton to me.' It was speculated that this was some sort of secret slush fund. When I asked current members of BirdLife Zimbabwe who remembered him, 'Did you think he was CIA?' I was told, 'We knew, but we considered him harmless.' Maybe this is a commentary on Rud's peculiarities, maybe a statement of trust from his friends. Gossiping about the harmless spy among them could have been fun for beleaguered Rhodesians. Any CIA connection would have had a very different significance for those who struggled against minority rule and against the anti-communist policies of the US during the Cold War, but the settlement of Boulton's estate secured his favor with the Zimbabwean government.56

After Louise died, Rud turned to the question of his estate. Overtures to American researchers found none who were willing to invest in Rhodesia. In 1976 Rud returned to the US to work out arrangements for the future of Atlantica. The articles of incorporation were amended to allow the trustees to liquidate the Foundation and transfer its property to another non-profit corporation, US or foreign. By 1978 Rud had arranged to transfer Atlantica's property to the Conservation Trust of Rhodesia. I have not been able to reconstruct how the Foundation passed from being a nongovernmental organisation to being owned by National Parks, or what Rud thought about endowing the government of liberated Zimbabwe. It could be seen as poetic justice if the remnants of two medium-sized American fortunes and the culmination of four lives built on white privilege were donated to the independent government of Zimbabwe. Or, perhaps the National Parks donation was a final echo of Inez's vision carried to Africa by Rud and Louise, and was not ironic at all. The lives of these four people in their contexts underscores the fact that the global phenomena of whiteness, American interest in African decolonisation, and Cold War science were contingent and variable.57

One former employee who remembered Rud was at Atlantica when I visited in 2011. Ngazi Zebu had begun working for him in 1978, as a gardener. By proving himself good at finding birds' nests and butterflies, he was promoted to the museum where he worked with collections. He lived at Atlantica, as a companion to Rud as well as a museum employee and told me that they got along well. Zebu told me that, after independence, students from Mozambique and Zimbabwe used Atlantica's facilities. I know little more about Rud's last years. His decline was precipitous, with two strokes that confined him to a wheelchair. He died in the hospital on a morning in January 1983. Friends had visited him the previous day.58

Science, government service and white privilege had brought extraordinary opportunity to a charming American man of middling and provincial origins who had no great scientific or managerial talent. In Africa, with the help and inspiration of his wives, he created a romantic, adventurous, comfortable life. As for the surveillance equipment described in the 1959 Washington Post article: undeniably it looks like spy paraphernalia and it stands to reason it was directly related to his career in intelligence, but most likely the chain of causation in this history of knowledge production should be reversed: rather than an undercover agent using birding as a cover for his listening devices and mobile darkroom, it seems a so-so scientist and a had-been spymaster applied his CIA experience and his inherited wealth to his personal goal of acquiring outstanding birding equipment.

Knowns and Unknowns in the Politics of Knowledge Production

Working with the evidence of the past, historians have something in common with those who analyse intelligence. There are known knowns (what we know), known unknowns (areas of recognised ignorance), and unknown unknowns (unrecognised areas of ignorance). On Boulton's scientific production, the known knowns include that his personal ornithological production was meagre and that the networks that sustained individual scientists were vital. Since science is by definition public knowledge that circulates, the known unknowns about what happened in Boulton's ornithological career have a lot to do with his slim publication record.59

On his intelligence career, we know that Rudyerd Boulton was a specialist on Africa with the OSS and early CIA. We know he worked for the CIA until 1953, at least, and that he retired from a federal position in 1958. This makes it is possible that his move to Southern Rhodesia was supported by and intended to be of service to the CIA, but what he really did for them after 1959 is not just a known unknown, but a guarded secret. This unknowability cannot be an end point; questions about CIA involvement are pressing and this one demands a provisional judgement: nothing I have learned about Atlantica's operations in Rhodesia - its finances, its isolation from known intelligence networks, the ageing of its founders - justifies saying it was vital to US intervention and intelligence gathering. But it does not follow that Atlantica was therefore unconnected to the CIA. Perhaps in 1959 the Agency offered a bit of encouragement or funding to put a well-liked and bereaved colleague out to pasture. One does not retire from the CIA as one would from an actual company. Imagine if under-cover travellers in later years needed shelter: Atlantica could have provided a hide-away. Had Rud ever heard anything worth reporting, he had the ear of embassy staff, at least, and possibly former colleagues in Washington. He would have passed on what he learned. We have no specifics about what the US government learned from him and how it acted on it. Boulton's role in intelligence after 1959 remains a known unknown and parties will disagree on it. We may yet learn more.

Unknown unknowns are beyond us. Rud himself created gaps in our imagination by not telling much about his life. But some critical points that were unimagined in the 1959 Washington Post article about Rud's scientific and federal careers have become known: Louise's ability to manage a gracious home, Laura and Inez's very existence, Inez and Louise's wealth, Laura's appreciation of adventure, Inez's concern with matters of race, Rud's experience of philanthropy, and the importance of companionable marriage. If the Boultons' move to Southern Rhodesia was not at the behest of the CIA, these newly knowns are the best way to make sense of it. In that sense, Rud's life, idiosyncratic as it was, offers good lessons about the politics of knowledge production: no matter how impressive others' scientific production may have been, no matter if they really were CIA plants, a lifetime of relationships, abilities, affordances, and affections created them. Had there been a smoking gun from CIA involvement or had Rud left a legacy in counter-insurgency or disciplinary authority in Zimbabwe, it might not have been necessary to ferret out the surprising and revealing stories of his earlier life. A known known among television audiences would have remained unseen: even spies have intimate lives that matter.

1 For their generous help with research for this article, I thank Angelo Lambiris, Alex Masterson, Michael Irwin, Dorothy Wakeling, Glen Ncube, Hugh Macmillan and Livingstone Muchefa. I also thank Andrew Bank, Allison Shutt and the anonymous readers for their comments.

2 Julius Duscha, 'Wild Birds Call Couple to Africa: A 30-Year Dream,' Washington Post, 26 August 1959. I thank Mary Le Croy of the American Museum of Natural History for bringing this article to my attention.

3 'Mobile Laboratory Aids Field Science', Rhodesia Herald, 25 May 1960.

4 Move to Southern Rhodesia: Atlantica Foundation Newsletter, 1, 5 October 1959, 1-2. Atlantica newsletters can be found in a few American archives, including University of Pittsburgh Archives Service Center, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, A.W. Mellon Educational and Charitable Trust Records, 1930-1980 (Mellon Records), AIS 1980.29, Atlantica Foundation, Box 37, Folder 13.

5 Helen Tilley, Africa as a Living Laboratory: Empire, Development, and the Problem of Scientific Knowledge, 1870-1950 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2011). [ Links ] European and American ornithologists in colonial Africa: Nancy Jacobs, Birders of Africa: History of a Network (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2016 forthcoming). [ Links ] US researchers in East Africa in the 1950s and 1960s: Etienne Benson, 'Territorial Claims: Experts, Antelopes, and the Biology of Land Use in Uganda, 1955-75', Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East, 35, 2015, 137-55.

6 Telephonic interviews with John Rehm, 7 and 13 January 2006. I found John through his wife's memoir, which mentions them renting the Boultons' house when they first went to Africa. Diane Rehm, Finding My Voice (New York: Knopf, 1999), 84-5. [ Links ]

7 Naturalist spies: Brendan Borrell, 'Taxonomy: The Spy Who Loved Frogs,' Nature, 501, 2013, 150-3. [ Links ] Ornithologists and biological weapons research: Roy MacLeod, '"Strictly for the Birds": Science, the Military and the Smithsonian's Pacific Ocean Biological Survey Program, 1963-1970' in Garland E. Allen and Roy MacLeod (ed), Science, History and Social Activism: A Tribute to Everett Mendelsohn (Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic, 2001), 307-35. [ Links ] Controversy over US funding of research in India: Michael Lewis, Inventing Global Ecology: Tracking the U.S. Biodiversity Ideal in India, 1947-1997 (Athens OH: Ohio University Press, 2004), 81-108. [ Links ] The poison plot against Lumumba: Ludo de Witte, The Assassination of Lumumba (New York, 2001).

8 Ken Flower, Serving Secretly (Johannesburg: Galago, 1987), 70; [ Links ] Larry Devlin, Chief of Station, Congo: A Memoir of1960-67 (New York: Public Affairs, 2007), 55-6; [ Links ] Personal communication from Larry Devlin, 19 November 2007. Boulton does not appear in a history of white American relations with Rhodesia: Gerald Horne, From the Barrel of a Gun (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2001). [ Links ]

9 Documents from 1953 released in 2003: Central Intelligence Agency Career Service Board, 'Meeting Minutes, 27 July 1953, http://www.foia.CIA.gov/sites/default/files/document_conversions/1820853/1953-07-27.pdf. CIA in South Africa: David Johnston, 'C.I.A. Tie Reported in Mandela Arrest', New York Times, 10 June 1990. CIA in Congo: Stephen R. Weissman, 'What Really Happened in Congo: The CIA, the Murder of Lumumba, and the Rise of Mobutu', Foreign Affairs, 93, 4, 2014, 14-24. [ Links ]

10 Boulton's life: J.N. Talbot, 'Honorary Life Member: Rudyerd Boulton, Honeyguide, 82, 1975, 11; [ Links ] Melvin Traylor, 'In Memoriam: W. Rudyerd Boulton', Auk, 103, 1986, 420; [ Links ] Alex Masterson, 'Wilfred Rudyerd Boulton', Honeyguide, 116, December 1983, 40-1; [ Links ] A.N.B. Masterson, 'Obituary: Wolfrid Rudyerd Boulton, Bokmakierie, 35, 1983, 96; [ Links ] AOU membership: John Hall Sage, 'Thirty-Third Stated Meeting of the American Ornithologists' Union', Auk, 32, 1915, 489. [ Links ] The 1913 letters: Rudyerd Boulton, 'Letter from a Boy Member, with a Postscript from His Mother', Home Progress, December 1913, 172. Amherst: Amherst College Class of 1922', http://www3.amherst.edu/~rjyanco94/genealogy/acbiorecord/1922.html. While he was completing his degree in Pittsburgh, he was already employed as an ornithologist with the Carnegie Museum: Jerome Jackson, George Miksch Suton: Artist, Scientist, and Teacher (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2007), 32, 40-1. [ Links ]

11 One of the more important of his ornithological publications: Rudyerd Boulton, 'New Birds from Angola', Proceedings of the Biological Society of Washington, 47, 1934. [ Links ]

12 None of the Boulton marriages produced any children and none of the women had children or stepchildren from their other relationships.

13 His first expedition with the AMNH was to Panama in 1924. He provided sketches of birds for a field guide on the region: Bertha Bement Sturgis, Field Book of Birds of the Panama Canal Zone (New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1928). Records of Laura early life and her marriage to Rud: Indiana University Archives of Traditional Music, Bloomington, Indiana, Laura C. Boulton Collection, Correspondence, Series I, letters in files 24-40 and Miscellaneous Series VII F. The Vernay Angola Expedition: John Frederick Walker, A Certain Curve of Horn: The Hundred-Year Quest for the Giant Sable Antelope of Angola (New York: Atlantic Monthly, 2002, 83-9. [ Links ]

14 The 1929 Straus Expedition: 'The Straus African Expedition of 1929', Straus Historical Society, Inc., Newsletter, 5, 2004,http://www.straushistoricalsociety.org/uploads/1086189277nl.pdf. The 1931 Pulitzer Expedition: Certain Curve of Horn, 98. Laura's expedition history: Laura C. Boulton Collection, Series I, letters in files 30-34. The Boultons making the first bird recordings in Africa: Jeffrey Boswall, 'Bird Sound Publication in North America: An Update', American Birds, 9, 3, Fall 1985, 355-6.

15 Rud's book: Rudyerd Boulton, Traveling with the Birds: A Book on Bird Miggration (Chicago: M.A. Donohue, 1933). [ Links ] Laura as a graduate student from 1931 through 1935: Robert McMillan, 'Ethnology and the N.F.B.: The Laura Boulton Mysteries' Canadian Journal of Film Studies, 1, 1991, 69-70. [ Links ] The 1934 Straus West Africa Expedition: Gloria J. Gibson, Daniel B. Reed and Laura Boulton, Music and Culture of West Africa: The Straus Expedition (Bloomington: Indiana University, 2002). [ Links ] Rud also shared memories of the 1934 expedition with American visitors in 1970: Alzada Kistner, An Affair with Africa: Expeditions and Adventures across a Continent (Washington DC: Island, 1998), 124. [ Links ]

16 'Melodic outlines and rhythmic complexities': Laura Boulton, The Music Hunter: Autobiography of a Career (Garden City, New York: Doubleday, 1969), 120. [ Links ]

17 Inez appears in several letters written by Rudyerd and Laura in 1936 and 1937. The end of the marriage: Laura C. Boulton Collection, Series I, letters in files 39-40. Alimony payments continuing from Zimbabwe: Atlantica Ecological Research Station Archives, Harare, Zimbabwe, Boulton Atlantica, Unsorted personal papers of Rudyerd Boulton. Laura's character in the 1940s and a critical assessment of her early work: McMillan, 'Ethnology and the NFB'.

18 Anthropologists in the OSS: David Price, Anthropological Intelligence: The Deployment and Neglect of American Anthropology in the Second World War (Durham: Duke University Press, 2008). OSS in Greece: Susan Heuck Allen, Classical Spies: American Archeologists with the OSS in World War II Greece (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2011). [ Links ] The organisation's proclivity for recruiting academicians: Robin Winks, Cloak and Gown: Scholars in the Secret War (New York: William Morrow, 1987). Boulton's position and title in the OSS: Records of the Office of Strategic Services, 1940-1946, College Park, Maryland, Archives II Reference Section (Military), Textual Records from the Joint Chiefs of Staff. Office of Strategic Services, 226/92/46/3, 'Schedule A. Africa Division SI', 28 February 1945. Boulton in two histories of the OSS: George J. Hill, 'Intimate Relationships: Secret Affairs of Church and State in the United States and Liberia, 1925-1947, Diplomatic History, 31, 2007, 497; [ Links ] Sarah Abrevaya Stein, Saharan Jews and the Fate of French Algeria (Chicago: University of Chicago, 2014), 22. [ Links ]

19 Shinkolobwe: K.D. Nichols, The Road to Trinity (New York: William Morrow, 1987), 43-7. Copper in OSS correspondence: Records of the OSS, 226/10/50, WN 17983, J.P. Chapin to Rudyerd Boulton, 25 January 1943.

20 Schmidt's experience in Congo: Clarke M. Thomas, A Patrician of Ideas: A Biography of A.W. Schmidt (Pittsburgh: Pittsburgh History and Landmarks Foundation, 2006), 41-4. A cloak-and-dagger account of OSS work in Congo during the Second World War: Robert Laxalt, A Private War: An American Code Officer in the Belgian Congo (Reno: University of Nevada Press, 1998). [ Links ] Boulton's personnel record and travel: Records of the OSS, 226/92A/8/106.

21 Continuing in SSU as Divisional Deputy for SI Africa: Records of the OSS, 226/10/389 WN#14043, 'Memorandum' on conference between State Department Division of African Affairs and SSU, 31 January 1946. Resignation from Field Museum: Field Museum of Natural History Archives, Chicago, Illinois, Staff Historical File, K.P. Schmidt Papers, Correspondence: Boulton, Rudyerd and Inez, Rudyerd Boulton to Clifford Gregg, 18 June 1946.

22 Inez and Rud's wedding: Judith Cass, 'Boulton-Stark Wedding News Surprise Here', Chicago Daily Tribune, 10 April 1942. Inez wrote society news for Chicago Daily Tribune. Travers-Cunningham wedding announcement: 'News of Chicago Society', Chicago Daily Tribune, 2 April 1916. Catholicism and Adler: Gilbert A. Harrison, The Enthusiast: A Life of Thornton Wilder (New Haven: Ticknor & Fields, 1983), 133. [ Links ] Howard Cunningham's death: Cook County, Illinois death certificate dated 13 December 1932. The building was 1430 Lake Shore Drive. Marriage to Harold Stark: June Provines, 'Front Views and Profiles', Chicago Daily Tribune, 3 May 1934.

23 'Eccentric society matron': Gloria Wade Gayles, Conversations with Gwendolyn Brooks (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2003), 29. [ Links ] Chagall donation: Werner Haftmann and Marc Chagall, Marc Chagall (New York: H.N. Abrams, 1973), 490. Friendship with Thornton Wilder and Frank Lloyd Wright: Patrick McGilligan, Nicholas Ray: The Glorious Failure of an American Director (New York: It Books, 2011), 23, 31. Her correspondence with artists is filed in several American archives under the surnames Cunningham, Stark and Boulton.

24 The memoir: Mary Le Beau, Beyond Doubt: A Record of Psychic Experience (New York: Harper and Brothers, 1956). References to 'Bob': 8, 10, 27, and 38.

25 Biographies of African American artists mentioning Inez: Joyce Aschenbrenner, Katherine Dunham: Dancing a Life (Urbana: University of Chicago, 2002), 23; [ Links ] Anne Conover, Caresse Crosby: From Black Sun to Roccasinibalda (Santa Barbara: Capra, 1989), 490; [ Links ] James Hatch, Sorrow Is the Only Faithful One (Urbana: University of Chicago, 1993), 109-10. [ Links ] A discussion of her influence on the Chicago Black Renaissance: Lubna Najar, 'The Chicago Poetry Group: African American Art and High Modernism at Midcentury', Women's Studies Quarterly, 33, 2005, 314-23. The Works Projects Administration (WPA) was a New Deal agency created under the administration of Franklin D. Roosevelt during the Great Depression. The South Side Community Art Center was founded in 1940 as part of the Federal Arts Project arm of the WPA: 'South Side Community Art Center: Seventy-Fifth Anniversary', http://www.sscartcenter.org/history.html. 'She did not care': Gwendolyn Brooks, Report from Part One (Detroit: Broadside, 1972), 66. [ Links ]

26 Howard University and Harper & Brothers: George Kent, A Life of Gwendolyn Brooks (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1990), 87-8. Brooks on Inez, see also: Gayles, Conversations with Gwendolyn Brooks, 19, 29.

27 'Women of all races': Le Beau, Beyond Doubt, 11-12. On race, see also 94, 102, 135. Colour bar at hotel: Kent, Life of Gwendolyn Brooks, 88.

28 CIA document released through Freedom of Information Act with his position in 1953: 'CIA Career Service Board Meeting Minutes.'

29 The two 1950s expeditions: Talbot, 'Honorary Life Member', 10-12. On the question of a North African Expedition in 1952, I thank Robert Dowsett, personal communication, 12 July 2015.

30 Federation: Alois Mlambo, History of Zimbabwe (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2014), 119-27. Luise White, Unpopular Sovereignty: Rhodesian Independence and African Decolonization (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2015), 37-67. On the performance of partnership: Allison Shutt, Manners Make a Nation: Racial Etiquette in Southern Rhodesia, 1910-1963 (Rochester: University of Rochester Press, 2015). Statements by the Capricorn Africa Society: The Capricorn Africa Society: Handbook for Speakers (Salisbury [Harare]: Capricorn Africa Society, 1955), D1 and D2.

31 Inez had had surgery in 1951: Field Museum, K.P. Schmidt Papers, Boulton to Schmidt, 20 August 1951. Rud's Retirement: Duscha, 'Wild Birds Call Couple to Africa'. Inez's death: 'Obituaries: Mrs. Rudyerd Boulton', Chicago Daily Tribune, 18 August 1958. Gift to Howard University: Mellon Records, Box 37, Folder 13, 'Minutes of the Second Meeting of the Board of Trustees of the Atlantica Foundation, 7 September 1959'. Inez's will: Washington, DC, Superior Court of the District of Columbia, Probate Division, Last Will and Testament of Inez Boulton, ADM 096313.

32 Lane Rehm's obituary: 'Col. Rehm, Once in OSS; Champion of Home Rule', Washington Post, 30 July 1958.

33 John Rehm's memories: Telephonic interviews with John Rehm, 7 and 13 January 2006. 'Fantastic' cook: Interview with Alex Masterson, 8 October 2011. Louise's letters to friends in the States: Mellon Records, Box 37, Folder 13. Lane Rehm's first marriage was to the writer Janet Flanner: William Murray, Janet, My Mother, and Me: A Memoir of Growing up with Janet Flanner and Natalia Danesi Murray (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2000), 39-44. Wedding of William Lane Rehm and Sarah Louise Super: https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:247G-2BH. Louise's will confirms that her family name was Super: Washington, DC, Superior Court of the District of Columbia, Probate Division, Last Will and Testament of Louise Boulton, ADM 001474.

34 Lane's retirement from banking and mention of Louise's cooking: Donald Downes, The Scarlet Thread: Adventures in Wartime Espionage (New York: British Book Centre, 1953), 84-5. Lane in OSS: Winks, Cloak and Gown, 145 and 95. Lane in Paris: Lelita Baldridge, A Lady, First: My Life in the Kennedy White House and the American Embassies of Paris and Rome (New York: Viking, 2001), 43. Louise at the Cordon Bleu in Paris: Kistner, Affair with Africa, 118.

35 Smithsonian Institution Archives, Washington DC, Alexander Wetmore Papers, Rudyerd Boulton, Box 7, Folder 6, 'Certificate of Incorporation of the Atlantica Foundation, 3 June 1959. Among the trustees were three men who had been Rud's associates in the Africa division of Secret Intelligence at the OSS: Chapin; Gibbs Baker, who was also the Boultons' attorney; and Schmidt.

36 Washington, DC, Superior Court of the District of Columbia, Probate Division, 'Last Will and Testament of Louise Boulton.

37 Kistner, Affair with Africa, 117. The Kistners were at Atlantica after the sale of paintings described below.

38 Louise entertaining: Personal communications from Angelo Lambiris, 20 July, 31 July and 5 August 2015. Louise's anecdotes about servants: Mellon Records, Box 37, Folder 13, Louise Boulton to Patty and 'Schmitty' (A.W. Schmidt), 19 February 1960.

39 Ibid, Rudyerd Boulton to A.W. Schmidt, 4 August 1960. The end of the Federation: White, Unpopular Sovereignty, 68-104.

40 The exhibition: Exhibition from the Atlantica Foundation (Salisbury [Harare]: Rhodes National Gallery, 1960), n.p. In 1962 it travelled to the King George VI Art Gallery in Port Elizabeth, South Africa. A review of the show in Port Elizabeth: Atlantica Foundation Newsletter 12, 1 October 1962.

41 'Books for Africa in Southern Rhodesia, Report' 1963-1964, 30 April 1964, and 'Nyatsime College', 15 June 1962: both in Mellon Records, Box 37, Folder 14. See also the Atlantica Foundation Newsletter, 14, 10 November 1962. Correspondence with students and staff at Nyatsime: Atlantica Ecological Research Station Archives, Harare, Zimbabwe, Boulton Atlantica, Unsorted personal papers of Rudyerd Boulton. The AAI, and CIA funding: Adam Hochschild, Half the Way Home (New York: Viking, 1986), 130-1.

42 Lyle Tatum: Personal communication from Steven Tatum, 27 May 2013. Tatum also remembers his father's contact including the US consul, Paul Geren and Hochschild, the CEO of American Metal Climax and chairman of the African American Institute, who sometimes visited from the States. Alzada Kistner described a farewell party for the US delegation at Atlantica when the consulate closed in 1970. Kistner, Affair with Africa, 120.

43 American researchers in Uganda: Benson, 'Territorial Claims'. Lochinvar: Mellon Records, Box 37, Folder 14, Rudyerd Boulton, 'The Lochinvar Project', 22 July 1962. Lambiris on the one black student at Atlantica: Personal communications from Angelo Lambiris, 20 July, 31 July, and 5 August 2015.

44 Rud's travels: Atlantica Foundation Newsletter 2, 3 November 1961 and ibid 14, 10 November 1962, and Mellon Records, Box 37, Folder 14, Louise Boulton to A.W. Schmidt, 25 July 1963. An American visitor: Lowell Schake, On the Wings of Cranes: Larry Walkinshaws Life Story (New York: Universe, 2008). The recording equipment: Personal communications from Angelo Lambiris, 20 July, 31 July, and 5 August 2015. Boulton's recordings are held at the Ditsong National Natural History Museum in Pretoria and at the Macaulay Library of the Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology. Recordings of Rud's voice in 1965 preserves him speaking in a trans-Atlantic accent, the dialect of patrician Americans in the first half of the twentieth-century: Roger [Rudyerd] Boulton, 'Thrush Nightingale and White-Throated Robin-Chat, The Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology, http://macaulaylibrary.org/.

45 The loan to Atlantica and $100 contributions: Atlantica Ecological Research Station Archives, Harare, Zimbabwe, Boulton Atlantica, Unsorted personal papers of Rudyerd Boulton, 'The Atlantica Foundation Audit of Accounts for the eight years 1 June 1961 to 31 May 1969'. Louise's mortgage: Mellon Records, Box 37, Folder 13, Louise Boulton to Gibbs L. Baker, 13 May 1960; Ibid, Folder 14, Correspondence about foundation funding: Mellon Records, Box 37, Folder 14, A.W. Schmidt to Rudyerd Boulton, 13 May 1964.