Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Kronos

versão On-line ISSN 2309-9585

versão impressa ISSN 0259-0190

Kronos vol.41 no.1 Cape Town Nov. 2015

ARTICLES

Designing knowledge in postcolonial Africa: A South African abroad

Daniel Magaziner

Department of History, Yale University

ABSTRACT

In 1958 the young artist Selby Mvusi left South Africa to study in the United States. Over the next decade Mvusi travelled the byways of the international art history and African Studies communities presenting papers, arguing against convention and plotting a new path for postcolonial African creativity. This article considers Mvusi's trajectory from teacher to painter to instructor and theorist of industrial design. Mvusi rejected both conventional art historical trends that condemned African modernism and the conservatism that inhered under the guise of national culture across the continent. He sought instead to reinterpret 'tradition' as an open and flexible chain of connection to the past, which extended into an unknown future; Mvusi saw industrial design as the best way forward for African creativity. The article concludes by examining his role in the founding of the University of Nairobi industrial design programme in the mid-1960s.

Keywords: Selby Mvusi, Pan-Africanism, postcolonialism, intellectual history, design, art, education

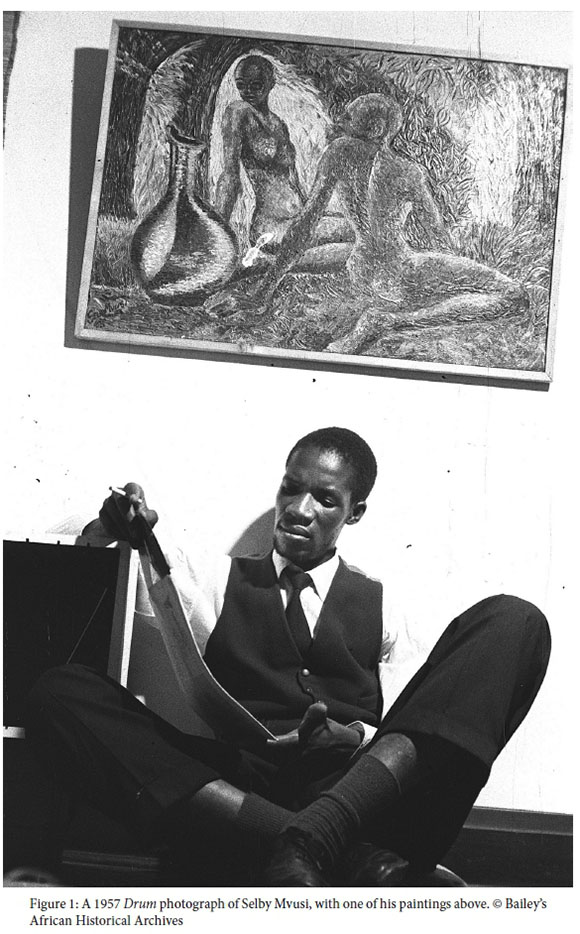

In August 1962, the Rhodesian National Gallery hosted what organisers optimistically declared to be the First International Congress of African Culture.1 It was essentially an art history conference. Experts on African art and culture from around the world descended on Salisbury to delight in the recently constructed gallery; to hear papers on tribalism, architecture, ritual and other subjects; to consider how Western artists and others had responded to 'ancient' African production; and to view what was billed as the largest exhibition of traditional African sculpture ever staged on the continent. Selby Mvusi was not particularly enthusiastic about tradition, but he made the trip from Kumasi nonetheless.2 Mvusi was the first African to lecture in art at the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology. He was 33 years old and four years into his exile from South Africa. Born in Natal in 1929, Mvusi was a Fort Hare graduate; he held a specialist art and crafts teachers training certificate from the South African government's art school at Indaleni; and he had taught art to African high school students in both South Africa and Southern Rhodesia. Mvusi 'spoke seriously about the possibility of serious art development in South Africa involving blacks,' the South African painter and teacher Bill Ainslie later recalled, 'he was [way] ahead in terms of thinking.'3 Mvusi's own art career indicated what was possible. He began to take informal art classes with Durban's Bantu Indian Coloured Artists (BICA) collective in the mid-1950s, while teaching art at the city's Loram High School. It was soon evident that was he was an exceptionally talented sculptor and painter. Within a few short years, he had begun to push in new directions; he was the first black South African painter to experiment with non-figurative abstraction while still in the country. Reviews noted his shrewd mind and fiercely, unapologeti-cally innovative temperament.4 In 1958 Mvusi earned a fellowship to study art education in the United States. Other than a three-day visit in 1961, he would never return to South Africa.5

This brief biography hints at the fascinating man that Selby Mvusi was. He himself rarely reflected on where he came from and what he had achieved; he claimed that he wanted to probe forward, not look back. At Salisbury, for example, he spoke about contemporary African art and artists. He insisted that there were already too many studies focused on man's past and too few 'on his out-reaching into the future'. Such assertions made the art historians at the congress uncomfortable. One eminent scholar advised him to reflect on the lessons of the ancient pieces exhibited in the gallery to coincide with the meeting. Mvusi brushed off the suggestion, claiming that there was little point in 'basking in the sun of the established'. It was far better to 'go on creating' rather than dwell on what had already been done.6

From Mvusi's perspective, the pieces gathered in the gallery were a legacy, an inheritance from time past, evidence of social structures that had once made sense, but no longer did. He rejected the premise that it was necessary for contemporary Africans to study and learn from the past: 'structures that men set up at any given time may characterise men, but they do not define men.' This was a shocking claim: was he not an African in the era of African independence and self-definition? What did it mean to be African if, as Mvusi insisted, 'men are free to change their structures at will?'7

What follows is a necessarily tentative study of one thinker, a South African artist who became a teacher, who then moved away from art to found Africa's first department of industrial design. It is an intellectual history of a fertile moment: immediately postcolonial Africa, when aesthetic and cultural questions were subject to much debate. Mvusi came to Salisbury from Kumasi and found in still-colonised Rhodesia debates similar to those he had left behind in Nkrumah's Ghana. Ostensibly debates about the aesthetics, merits and promise of African art, the conversations in which Mvusi immersed himself were about much more than objects. What was to be the nature of independent African society? What was the relationship between the pre-colonial African past and the postcolonial African future? What, more fundamentally, did 'Africa' mean? What did the concept conceal, what did it enable? When Mvusi stood before an audience of art historians, ethnographers, museologists and artists in Salisbury, he was speaking on matters of timely political, ethical and historical importance.8 As he passed among the new institutions and personalities that were then developing knowledge about the continent - international bodies like UNESCO and the African Studies Association, disciplines like art history and ethnography, and bureaucracies like universities and nation states - he insisted that there was much these institutions could never know about Africa, because Africa was still being made and defined.

This essay covers only the period of Mvusi's exile from South Africa, yet at the outset I must underline the very obvious point that he was a South African. He came from a country fluent in the rhetoric and practice of racial nationalism; he attended schools and taught students during a time when the idea that race equalled fate was most decisively inscribed in the bureaucracy and practices of his native land.9 He was thus uniquely sensitive to the gathering claims of African nationalism, where the term 'African' acted both to define and to limit his own identity and creativity. His writing made the connection between his South African background and his scepticism towards the received wisdom of mid-century Africanist knowledge clear (although to my knowledge he never stated this explicitly). Against romantic tales of the past, Mvusi counselled audiences that the future was what mattered; against advocates for the innate, instinctive, racial genius of African peoples, he taught his students that they needed to study, survey, trouble and think. He was an artist who, over the course of the 1960s, came to believe that art was not going to promote real progress. He was a humanist, who by 1965 was convinced that technology was the most vital factor in human society and that it was in pursuing and developing industry that Africans would best express themselves and live fully in time. He was an African who insisted that to be an African was to live openly and creatively without knowing what being an African meant.

Mvusi's journey to Kumasi, Salisbury and beyond began in Durban in 1957, when he received news that he had won a fellowship to the United States. Sponsored by the Cabot Trust, this was money intended 'to help gifted individuals at important moments in their careers.'10 Although he was beginning to earn a reputation as a visual artist, Mvusi had been recommended to the trust because he was an accomplished art teacher and in 1958 he moved to State College, Pennsylvania to do a Masters of Education in Art at Pennsylvania State University (PSU). His adviser was Viktor Lowenfeld, a globally renowned theorist and practitioner of art education, who had turned PSU into the premier centre for the study of the relationship between visual culture and pedagogy.11 Jack Grossert, the South African government's organiser of arts and crafts - himself a pedagogical theorist of some repute - recommended Mvusi for PSU. Grossert was a great admirer of both men; he had incorporated many of Lowenfeld's techniques into the curriculum of the apartheid government's own art teacher training school at Indaleni, which is where Grossert first met Selby Mvusi.12

In State College, for the first time Mvusi had unfettered access to oil paints, brushes and easels, tools that most Western artists took for granted but which had been in scarce supply both at Indaleni and among the non-European population in Durban. But even amidst this abundance, he made it clear that his true passion was in art education. Mvusi shared with Lowenfeld and Grossert two convictions: first, that every student - every person - no matter their level of talent, would benefit from the opportunity to create with their hands; second, again like Lowenfeld and Grossert, Mvusi was deeply suspicious of the cult of 'the artist', which held that creative genius was an individual attribute. As Mvusi saw it, artists were nothing without society; it was society that inspired them, society that conditioned their work and that made it legible. If 'artists are made by the social environment in which they participate', it was vital that the social environment be conducive to art. He himself came from a community where access to the visual arts was far from assured; not surprisingly, at PSU he considered the relationship between art and economics in essays on subjects like 'the role of art education in underdeveloped countries'.13

Notwithstanding his self-identification as an art educator, it was his reputation as an artist that brought him into contact with the nascent field of Africanist art history. In 1959, Mvusi exhibited 15 paintings at the second African Studies Association meeting in Boston, where he had recently moved to augment his training with an MFA from Boston University.

These were largely non-figurative works that he had completed while in the United States. In a flier that accompanied the exhibition, he reflected on the paintings in light of a poem that he had written while studying at PSU. Mvusi published numerous versions of this poem over the course of the next few years, yet its initial inclusion at the ASA conference is the most revealing, since both the poem and the exhibition departed dramatically from the script on African art.14 Mvusi's poem, 'The Nightwatchman from Zululand', began with the story of a 'man with a glorious past of bravery and conquest'. So far, so consistent: at the ASA, conference goers had the option of hearing a panel on the history of African art, chaired by Roy Sieber of the University of Iowa. Today considered the 'founder of African art history in the United States', Sieber was a specialist in the 'traditional' art of Northern Nigeria. He wrote extensively on objects' then-diminishing role in rituals of authority in that region. Such salvage ethnography was fairly common in early Africanist art history, and by sharing the story of a 'lion long tamed', scion of 'warriors long dead', Mvusi's poem seemed sympathetic to the scholarship.15 Yet as the poem proceeded - and as Mvusi's flier explained what he meant - it became increasingly clear that Mvusi was bemoaning not the passing of the glorious age but the Nightwatchman's frustrating inability to find new glory in the present. 'The Nightwatchman accepts just being, he wrote, 'he never starts to become.' This critique was subtle, but critical: at the ASA and in other forums, the rise and ruin of Africa's glorious past was the oft-told tale. Instead of dwelling on the past, Mvusi wanted to start something new.16

The ASA exhibition announced Mvusi's presence in the US and he was soon in demand as an expert on African art. Later that fall he met Evelyn Brown, the assistant director of the New York City-based Harmon Foundation, an organisation with an abiding interest in African American modernism of all types.17 Over the course of the 1950s the Harmon Foundation had begun to turn its focus to Africa by publicising the pioneering efforts of the Nigerian painter Ben Enwonwu, among others.18 In 1960 the foundation published a pamphlet by Forrester B. Washington, an African American art aficionado and lecturer at the Atlanta School of Social Work, which was one of the very first attempts to identify and seriously consider contemporary African artists. The foundation was frustrated that it had found so few artists from South Africa, and its representatives were delighted to meet Mvusi.19

Mvusi shared their enthusiasm. At the ASA and elsewhere, he had been frustrated to learn that 'the contemporary African artist is hardly ever mentioned' by so-called experts in African art. Although he appreciated scholars' efforts, he was worried that his fellow African artists might be 'buried [in the] august brilliance of the arts of past African cultures'. As 'The Nightwatchman' told, Mvusi felt that too many African artists were concerned with what once had been. He appreciated the glories of Ife and Benin, but he worried that both contemporary African artists and the art historians who ignored them were missing the point: Ife and Benin had been glorious because their artists had risen to the challenges of their time and place. For artists in Mvusi's own day to obsess over the achievements then was to risk losing 'their individuality and relevant expression concerning the now'. 'Art serves life', Mvusi wrote to Evelyn Brown a few days into the 1960s; its analysis therefore needed to begin with living.20

When he wrote those words in mid-January 1960 he did not know how complicated his life was to become. Mvusi was on a student visa and he was expected to return to South Africa once he completed his degrees. Sharpeville changed his plans. His wife was with him in the US, but they had left their children behind with her family in the Eastern Cape. He worried about them as violence increased with the State of Emergency. Mvusi was a Youth Leaguer at Fort Hare before stepping away from organised politics during the 1950s. He was not in imminent danger back in South Africa, yet he hardly relished the prospect of returning to what was increasingly a police state.21 In the summer of 1960 his connections with the Harmon Foundation and Forrester Washington helped him to secure a position lecturing art at Clark College, a historically black school in Atlanta, Georgia. As South Africa raged, he threw himself into the work of fighting against art history's contention that the only worthy African art came from the past.22

While preparing for Clark, Mvusi stepped away from the politics of African art history to pose fundamental questions about the nature of art, anywhere, at any time. Mvusi plotted the origins of art in the dialogue between creators, their communities, and their historical context. He suggested that the arts (here not limiting himself to visual arts) were an almost natural byproduct of human life. 'The Arts concern themselves ... with living in the world in which we are', he told his students. The arts were people 'responding to the abundant experiences which life offers'. Without time and place - 'the world in which we are' - there was no art. Mvusi restated the point: 'every artist belongs to his own age.' Read with Mvusi's correspondence and 'The Nightwatchman', it is clear that the last point was yet another warning not to obsess over the achievements of the African past, because such achievements yielded insights only into those times, not his and his students' own. He did not make this explicit, only limited himself a sardonic remark about American neoclassical architecture's tendency to ape Greece, 'that immutable hallmark of refinement', rather than find its own footing. But the point was clear: artists created in their time because they had something to say about their time.23

This was not a simple task, but it was a necessary one. At the ASA Mvusi had insisted that the Nightwatchman's passivity in the face of change was a predicament shared 'with modern man in general'.24 Change was unsettling and people naturally turned to traditions in search of 'something unchanging, something re-assuring, something constant in the flux of change'. In the midst of the turbulent postwar world, lives were becoming more technological and less obviously human. It was easy to understand why people uneasy with their present held tight to the achievements of their past. But with the dawn of the machine age, 'it becomes clear to us that we have to fight to keep ourselves human.' It was from this tension that art emerged. 'New materials, new processes, new relationships, demand from us new action.' The present was a challenge to be faced.25

As 1961 dawned in Atlanta, Mvusi was forced to follow his own advice by seeking a new course of action. He needed to get his children out of South Africa, which meant that he had to leave the US and find work back on the continent. He animated his old southern African networks and secured a position to teach art at the Goromonzi High School just outside Salisbury, in white-ruled, but still relatively sedate, Southern Rhodesia. In January 1961 he made a flying visit to the Eastern Cape to collect his children; he was feted by the local community and, he recollected, trailed everywhere he went by the Security Branch. Three days later, the family was in Southern Rhodesia and he was settling in to teach.26

He was not long away from the United States. Boston connections led him to an invitation to address a meeting of the US committee on UNESCO, held at Boston University in October 1961. There Mvusi sat on panels alongside the experts on African art history with whom he wanted to disagree.27 He found it quite easy to do so. In Boston he shared the dais with William Fagg, the deputy keeper of the Department of Ethnography in the British Museum, a collection and an institution long associated with the declensionist story of African art history.28 In Fagg's opinion, whereas once Africa had produced objects of evident brilliance, now there was only rubbish, born of the African's too hasty exposure to Western art. Missteps like the 'acceptance of European oil paints' had led Africans down the path of 'surface enhancement by color', which simply was not African. Fagg agreed with another panelist that in 1961, African art was in a state of 'confusion, if not chaos.'29

That was not how Mvusi saw things. Where others saw chaos, he saw untapped creative possibilities; instead of confusion, he saw only change. Given the continent's centuries-long experience of slavery and colonialism, he read history to show that the African's 'most pressing concern was not so much that [his] symbolism shall remain exclusively African, but rather that it shall serve his survival through the years of change.' The art that historians hailed as tradition had once served a purpose; now, new needs demanded new art. Perhaps thinking about Fagg's critique of artists' use of 'Western' mediums like oil paints, Mvusi castigated 'purists [who] have lamented this eclecticism of African cultures. They have interpreted [this] as representing a ... dissipation of otherwise purely African culture.' He had no time for that. To lament past purity was to 'condemn Africa's inventiveness and her innovations'. He was well aware of the ways in which contemporary culture, especially the art world, fetishised the new, the cutting edge, the avant garde. He called Africanist art historians' bluff: to write and lecture in the way that they did was to 'indict novelty itself'.30

This was a rare moment in the annals of Africanist art history: an artist sat alongside the scholars and told them just how wrong they were. In 1961, 'the African can no longer go back to where he has been. He is to go forward.' Speaking to experts on West African art, Mvusi rejected too great a focus on aesthetic achievements: 'the mandate is not of art, but of humanity.' In the past, artists had created to propitiate their spirits, as only people in their time and place knew how. The past mattered because it showed how previous generations of creators had articulated their humanity, as Mvusi wanted his own to do. Tradition did not decline, it changed, just as today's African is his history, he is his culture.' The past did not define the future; people's active living built it. 'It is ... only by standing up to the challenge of our time that we truly extend and revitalise the values and ideals of our forebears. In this are we honoured in their eyes; through this do we honour their efforts.' Of the collective subject 'The African, he claimed to know only that 'his journey is his native land.' In 1961, as talk of political and cultural independence swirled, Mvusi disabled the conventional narrative of African art and African identity; he disabled geography, he disabled the power of history and tradition over the present.31 What remained was a grammar for creating. Once, Africans had made things to propitiate their spirits and serve their needs. Now, 'we too have our spirits to propitiate.'32

After the conference closed, Mvusi returned to Rhodesia. He would not remain there very long. At the UNESCO meeting he had argued that African 'nationalism was a creative force', not only a political moment.33 From Ghanaian conference attendees he learned that there was a position in art education at the College of Science and Technology in Kumasi. Mvusi believed in the creative potential of African nationalism; he was consumed with questions of the now and the future, the propitiation of the African spirit in times of change. In late 1961, he and his family left Southern Rhodesia for Kumasi.34

It was an uneasy fit from the outset.35 Mvusi arrived in Kumasi to find that postcolonial and pan-Africanist Ghana was not the free land he wanted it to be. Mvusi's writings reveal a man who rejected any efforts to racialise social identities; by the early 1960s, he had moved in the direction of a pan-Africanism that accepted all comers regardless of race, provided that they demonstrated their allegiance to the continent and its future. In Ghana he found many other South Africans, both 'so called "black" South Africans and "white" South African'. His scare quotes indicated his rejection of such categorisation - yet in Ghana, the 'whites' were paid the same as European expatriates and African American returnees, far more than continental blacks like Mvusi. Having stated their opposition to apartheid by coming to Ghana, Mvusi reasoned that his lighter-skinned compatriots ought to have rejected the pay differentials. Most had not. Mvusi reported that he arrived in the midst of 'mass exodus of "black" South Africans' from the country, but he decided to stick it out because he wanted to show Ghanaians that '"black" South Africans were not expatriate to Africa and had to forego privilege in order to contribute to the over-all effort at [Africa's] reconstruction.'36

What was rechristened the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (KNUST) in 1962 was a worthy venue for his efforts. Once a teacher training institution, it had evolved into a decidedly future-oriented, modernist institution. Aside from the sciences, it featured independent Africa's first town planning and architecture school, as well as an art department. Mvusi was the first African art lecturer at the university. He 'conducted regular seminars, set up exhibitions and [with his students] produced works that can . stand to standards attained anywhere in the world.'37 He craved the approval and acknowledgement that the international conferences granted and applied for funds to return to Southern Rhodesia in August 1962, to attend the Salisbury conference at the National Gallery. The university rejected his application on the grounds that, since he was not Ghanaian, he could not adequately represent the nation and the university. This smarted, but Mvusi persevered and managed to have his way paid by the conference organisers themselves.38

The conference had two underlying purposes: first, to exhibit and examine African traditional art, and second, to consider the impact of African art and culture on the twentieth century beyond the continent. This was not exactly novel, but the record suggests that the attendees were enthused to be talking about such things while actually on the continent. The conference was organised and funded by a British-ruled, white supremacist state, yet in the interests of 'African culture' organisers had invited people expressing a variety of viewpoints. Frank McEwen, the European-born director of the gallery, opened the proceedings in the name of 'our great African culture', then turned the stage over to the director of the Institute for African Studies at the University of Ife, S.O. Biobaku.39

The latter drew on the rhetoric of African nationalism in his remarks. He recalled the legacy of 'negritude', associated especially with francophone Africa. 'Dancing ecstatically, drumming skilfully, telling tales rich with meaning', negritude writers 'saw Negro Africans . expressing something richer and deeper than riveters erecting skyscrapers or designers of machinery bent over their drawing boards. They were expressing their own inner genius.'40 Selby Mvusi was a silent member of the audience during Biobaku's address, yet it is easy to imagine that such talk gave him pause. Biobaku's negritude was as exclusive as art history's 'Africa'; there were certain things - oil paints in the latter, 'riveters and designers' in the former - that were not and could not be African. Biobaku's assertion found plenty of company in Salisbury. William Fagg, Mvusi's interlocutor from the UNESCO conference, sounded a similar note. He was responsible for staging the exhibition of African art and he had chosen only works representing 'ancient' African achievement. 'I suggest that we should look at this exhibition as something purely and fundamentally African', since 'everything there . is something stemming from African traditions.'41 Fagg was speaking in general terms about 'Africa', while exhibiting work only from the continent's Western and Equatorial regions. This would have irked Mvusi, who in 1961 had complained to Bill Ainslie that southern and East African expression was being held back by 'bowing before the gods of Benin'.42 Fagg saw things differently: he suggested that 'his' works be viewed as the 'standard, by which we can . test other work' that claimed the mantle of African art.43

This was the conference's disconnect. On the one hand, it was dedicated to the preservation and exhibition of classical African culture, while on the other to explore how that culture had influenced the modern world, where riveters and designers predominated. The latter purpose brought Alfred Barr, one of the founders of the Museum of Modern Art, to the conference - although he apparently felt that one of his colleagues from the Museum of Primitive Art in New York City would have been a more suitable invitee. Mvusi was enthused that Barr had made the trip, but soon grew cynical.44 Barr and other contemporary art world luminaries sat silently through most of the papers, he reported, the majority of which echoed negritude and preservationist thinking and 'were dominantly ethnological'. Those interested in contemporary art were happy to reflect on how Africa had influenced twentieth-century trends, but they left the question of contemporary African artists to the art historians, ethnologists and others who expressed nothing but distaste for the subject.45

Indeed, at Salisbury the ethnologists' primary concern was how to prevent African artistry from deteriorating under pressure from tourism and industrialisation, which combined to produce what McEwen called 'airport art'. He spoke glowingly of the work of organisations like the Rhodes-Livingstone Institute's African craft village in Northern Rhodesia. The institute employed 16 craftsmen to produce objects in a 'traditional village' setting - although they could not live in the village, since Rhodesian racial policy required African employees to live in the locations. That was regrettable, but, as the venture's director explained, 'the arrangement does have one great advantage: we are able to keep the Village looking fairly authentic. If the craftsmen lived on the site we could not hope to persuade them to forego European clothing, blankets, bicycles and enamel cooking utensils in favour of the skins, backcloths and clay pots used by their fathers.' The craft village was a living museum, a reminder that while 'African[s] in present day Rhodesia are concerned with modernising', they ought not to forget what was traditionally African. The craft village's authorities carefully policed their craftsmen to ensure that they 'stick with the traditional'; if any began to innovate, 'we try not to encourage them too much.' Warned that 'if a great artist arises in the Craft Village [the Institute] will not succeed in suppressing him', the craft village's director assured the crowd that he would 'certainly do my best'.46

Mvusi spoke on the second to last day of the conference on 'Towards a Contemporary Art in Africa'. The body of the talk was familiar from his talk to UNESCO; it was brush-clearing, assertive and prospective. 'New symbols must replace the old,' he noted, thinking perhaps of the sculptures upstairs, 'true art can never be mere incantation and repetition.' Africa's past was manifest already in actually living Africans and therefore there was no need to fret about Africa's decline. In his remarks he began to develop a new theory of significant form to connect artistic practice across time and space. Imbued with history and tradition by virtue simply of being alive, he suggested that contemporary artist structured 'that which he deems significant ... [into] a form which is open to the scrutiny of men'. Revisiting an old theme, Mvusi placed the dialogue between creator and society at the foundation of art: 'to the extent that this form is [a] significant statement on life ... it will be regarded by his fellow-men as central to social action.' The significant forms in the gallery were not only aesthetic achievements; they were significant forms because they were evidence of the dialogue between artist and society. Mvusi asserted that art history ought to recover the ethics of the past that had rendered such forms significant as he understood the term - not formal aesthetics, but embodied context - while artists ought to concern themselves with change. 'Change is [the] constant,' he read. 'The acceleration of change and the changing character of change today, should contribute not to bewilderment revulsion and resignation, but to an entrenchment of the tested belief in Africa that the journey is the native land.' Like any good academic, Mvusi had learned to recycle previous language into new papers, but the point was significant enough to repeat. The journey was the native land, full stop. White bureaucrats had found 'native' to be an extremely productive concept with which to build separate development in Mvusi's own country; as he spoke in 1962, nationalists elsewhere in Africa were adapting the language of autochthony to their own purposes. He took 'native' in a different direction, to claim that the term meant only the unfolding story of change.47

In the question period that followed his seminar, Mvusi hinted that he was also beginning to think beyond the category of 'art'. Asked about the future of artistic practice, Mvusi began to talk about technology and planning. He had been reflecting on the dynamic interplay and tension between human beings and technology since preparing to teach at Clark in 1960. In thinking about the future of art in Salisbury, he reflected that many contemporary artists were struggling to address the alienation of humanity in the age of the machine. Too many artists and others failed to realise that 'the machine, however complex, is a tool in the hand of man', just like a chisel or a brush. In his own lifetime, more and more Africans had mastered the latter; so too would they master the technologies yet to come. To be an artist took time, technical facility, practice and planning.

A voice from the audience disagreed. 'If I understood you rightly, you would regard the work of art or whatever else it may be as a conscious and deliberate act of creation by the artist. I do not think this is so.' Mvusi stood his ground. He explained that all pieces of art were significant forms because they signified their purpose in terms of the needs of their era. Art was not about mystery, but transparency. Significance was the product of reasoned thought, work and planning. 'If art has, as I believe, its origin and end in the life that man lives, then inasmuch as man is conscious of life and the livingness of life, he is conscious of art and the creation of art.' Mvusi had already unpacked the categories of Africa and Native. Now, he was looking within 'art' and found 'consciousness' inside. He offered an example of the diversity of this repackaged 'art', as he anticipated it: 'let us remember that we have to prepare for the wedding feast much as we may lose ourselves in the ecstasy of the wedding day.' Conscious and timely, design and planning were as integral to African art as tradition and emotion. Biobaku was wrong: riveters and designers were artists too.48

The conference closed the day after Mvusi spoke and he soon returned to Ghana, to find an invitation to attend an International Society for Education through Art conference in Montreal. Or rather, he found an invitation after the fact: it seems that KNUST had again decided that he was not Ghanaian enough to attend on the university's behalf. Shortly thereafter, Mvusi decided to resign. His disgust with Ghana's nationalist and racial politics made him practically foam with rage. 'At this state in Pan-African political development, at this stage in Nazi oppression of my fellow countrymen in South Africa, I bow to no man', he informed the university authorities, before decamping with his family to London.49

There was more to Mvusi's decision than his anger at Ghanaian politics indicated. At PSU in the late 1950s he had written on the education of art teachers in low-income countries; now, in 1963, he was beginning to question his dedication to art as typically understood. From London at the end of 1963, he began to think more concretely about the challenges and potentials of educating a generation of African students to face the challenges of their industrial, technologically sophisticated age. He wrote to Evelyn Brown at the Harmon Foundation and asked her for a briefing on the training of industrial designers in the US. Local British connections led him to the Brighton based International Council of Societies of Industrial Design and eventually to an invitation to present a paper at a March 1964 industrial design seminar in Bruges. Representatives from the UK, the US, Italy, West Germany, Sweden and Norway attended; Mvusi was the only attendee from the Global South.50

Mvusi's contribution to the seminar was entitled 'The Education of Industrial Designers in Low-Income Countries'. Nearly fifty pages long, the paper showed that he had used his time in London to train himself to think like a designer, at least in part by building from the theories he had begun to develop in Salisbury. Central to these was the concept of significant form. In Salisbury, Mvusi defined all successful pieces of art as significant forms in that they signified something from and to the society in which they existed. He suggested that, at its root, design was also about the creation of significant form; to conceive, plan and build an object was the 'plastic realisation' of human consciousness.51 Bought, sold, treasured, and discarded, all objects participated in social life. Things communicated. Mvusi's scholarly experiences suggested that, although art was essential, it was also obscure and subject to mystification and misinterpretation. Design, on the other hand, was always present - in both senses of the term.

As such, he assigned tremendous ethical importance to its practice. Significant forms - or 'significant statements', as he also described designed objects - were those items 'originally conceived of and made for the right reason'. To be right was to think in terms of social need. 'Society and culture are intrinsic elements of design. We do not therefore design for society or for that matter design in order to design society. We design because society and ourselves are in fact design. We do not design for living. We design to live.' Inside this repetitive, circular language was a very simple argument: human societies and human subjects are the products of conscious design and planning. Nothing just happens, everything is made, everything is planned, everything is enacted - identity, nations, epochs, the things we buy, for good and for ill. To design righteously was to embrace the current moment and to exploit it consciously to better society.52

In this paper and elsewhere, Mvusi called for the 'industrial reconstruction' of African society.53 Reconstruction was a telling term. With it, he connected his art historical analysis with his interest in industrially produced objects. Mvusi thought sculptures and other objects significant because they had once served a now-obscured social good. The industrial designers of today would do the same, only now working with 'modern science and technology', not clay and wood. He rejected as a myth any assertions that 'non-Western cultures are incompatible with modern science and technology'. There was no such thing as incompatibility, there was only a lack of training and failure consciously to adapt the material at a creator's disposal. Mvusi pronounced himself tired of those like Biobaku, who claimed that 'science and technology stood in opposition to their own in-born sense of imagination and intuition'. As he saw it, such thinkers hid underneath the blanket of race; they were comforted to think that the social integration of the past times might be replicated in the present as it once had been - through sculpture, through dance, and not through technology and industry. Mvusi thought this short-sighted. 'The rupture that the slave and colonial years effected' was real. It was 1964. Any cultural system that exists [in] the world today must . adapt science and technology to their modes of living.' In Bruges, his tone was practically apocalyptic: 'this they will have to do or die.'54

Mvusi's essay had a huge impact in the Bruges seminar. Almost immediately, excited correspondence circulated to plan a follow up seminar focusing exclusively on how to train industrial designers to do this essential work in low-income countries. Mvusi himself proposed to study how education systems in independent African and other non-industrialised countries 'relate to the socio-economic and cultural character of these countries and how industrial design education can best fit into such circumstances'.55 From Bruges he returned to London, then he began to travel: first to Cairo, then to Kampala and Nairobi. At each stop he corresponded with supporters and potential funders about the proposed seminar, as well as the prospects of industrial design in Africa. Nothing came of it immediately, but the travel allowed him to refine 'both my plastic vocabulary and my social consciousness'.56 By June he was settled in Nairobi.

Over the course of the next months, international connections put him in contact with organisations that could support the sort of design programme he envisioned.57By the end of 1964 it remained only to find a home. The university colleges at both Makerere and Nairobi were likely, yet neither was perfect. Nairobi had an art department run by a former colonial official named John Baynes, who seemed interested in having Mvusi around. Mvusi liked Baynes in turn; he thought that the Englishman shared his own suspicion of 'abstract aesthetics' and 'vague culturalistic assertion'. But Baynes's suspicion of the accepted truths of African art apparently did not translate into good teaching; his programme was suffering, especially in comparison with the better-established Margaret Trowell School of Fine Arts at Makerere.58

Mvusi had a rather low opinion of the Kampala scene.59 He judged the school 'in line with the expected and so Makerere is in business while this place down here [in Nairobi] is fizzling out.' The vice-chancellor of the East African university colleges wanted Mvusi in Kampala, but Mvusi did not want to go - partly because of ideology, and partly because of pride. The Margaret Trowell School was chaired by Cecil Todd, formerly professor of art at Rhodes University, the white South African university with ostensible authority over Mvusi's alma mater, Fort Hare. That institutional relationship meant nothing when it came to Mvusi's ability to 'gain admission or help when I started on the long road to where I am'. Only upon leaving South Africa and arriving in the United States was Mvusi granted 'the opportunity to stand [with a] brush and easel in a studio in an art school'. Todd had not been unduly exercised by the exclusion of black artists then and Mvusi could not stomach being under his authority now.60

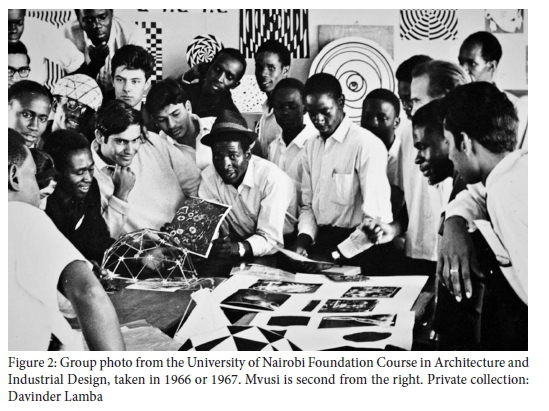

Besides, Makerere was an established art school, already set in its ways. Nairobi was failing but, like KNUST, it had an architecture school - it was training young East Africans to move forward, and it was where he wanted to be. Mvusi's patrons and supporters around the world appealed to the university authorities and helped him to secure funding for the proposed designed programme. At the end of 1964, with money guaranteed from the Rockefeller Foundation, Mvusi succeeded in being appointed to a lectureship at the University of Nairobi, in what had once been Art and which, in 1965, was renamed the Department of Architecture and Industrial Design. The programme welcomed its first design students that same year.61

As he had when preparing to teach at Clark in 1960, Mvusi again developed a series of working papers with which to begin to train his students. He focused on the ethical dimensions of industrial design: 'responsible Design action is predicated ... on conscious commitment to time now', he reflected in September 1965. The past did not matter in a practice where 'the problem to be resolved, the commitment to be recognised and the question to be answered ... is: What is Our Time?' If 'design is the realisation and the plastic resolution of time consciousness', then the objects that people used and consumed were the manifestation of the contemporary; design's ethical intervention was that by recasting and reconstructing people's aesthetic investment in time present, designers could influence society's progression into time future.62

This was bigger than Nairobi and bigger than Kenya. Since the 1930s, African intellectuals, exemplified by Leopold Senghor, had plotted a map of universal progress in which African humanism would neatly complement Western technology.63 Mvusi was concerned with Africa's contribution to universal progress as well, with a twist. In Bruges, he developed a near-messianic purpose for industrial design to complement his urgent, almost apocalyptic calls for its institutionalisation. It was true that science and technology had been harnessed first in the West, he conceded, but the West had failed to recognise technology's full potential by choosing, through colonialism, 'to build on race and not on humanity'. In the postcolonial era, it was time for technology to be adapted to the far greater cause of 'freeing peoples everywhere from the pressure of physical want'. By designing and producing to suit their needs, as they currently experienced them - poverty being paramount - African designers would liberate technology from its association with European racism. They would inaugurate a new modern age, 'when the most decisive factor in international relations will be the humanity that a people embody and not the physical power that they wield.'64

Over the course of the next two years, Mvusi expanded on the theory that African design and African industrialisation would perfect the global community. He developed an analysis of history in which the circulation of objects had been humanity's motor, for good or for ill. Rather than read the recently concluded colonial era as a struggle between nations, ideologies or identities, Mvusi saw it as an aesthetic and material contest fought through and with objects. 'During the colonial years, the manufacture of goods was in the hands of a few,' Mvusi taught. 'These manufacturers held the rest of the people ... as captive markets. This is the essence of the thinking behind colonialism.' Given the predominance of objects of European manufacture in Nairobi, Mvusi concluded that political independence had only granted Kenyans and other Africans the right to consume European goods, not to produce their own. True independence would come only when 'the African personality [is] defined industrially', in objects of African design and manufacture.65

Mvusi's mid-1960s working papers were his manifesto. Material objects of human creation were the plastic realisation of time consciousness; successful objects were significant statements. If Africans did not begin to consume thoughtfully and design accordingly, 'so long as the definition of personality is not given definite form through the instruments of present day technology, African people will remain "aliens" to the 20th century.' Out of step, out of time, without industrial design, Africans would remain victims, not masters, and 'the form of this century will continue to be defined and determined by non-African people'. Industry completed independence; African industry would complete modernity.66

In 1966, Mvusi took the argument that the African personality needed to be defined industrially to the epicentre of a rather different conception of how Africans ought to exist in 'time now'. In late March he travelled to Dakar to participate in the First World Festival of Negro Culture. Senghor's Senegal was in full flower at that time, a gathering behemoth of art and self-consciously 'African' culture. Specialists in art, dance, theatre, music and other disciplines gathered from 45 countries to attend the two-week-long colloquium that coincided with the massive, month long festival. Mvusi spoke towards the colloquium's end, by which point the mood of the meeting had been set.67 In the conference's wake, Presence Africaine published a 600-page collection of what it judged to have been the most important papers read in Dakar; Mvusi's was relegated to the second volume, published years after the fact.

The structure of the first volume is extraordinary evidence in itself. First, despite being held in an independent West African country, the colloquium replicated the form of the 1962 Salisbury conference in that it focused primarily on 'traditional' African culture and tradition's dialogue with its 'other', the modern, twentieth-century West.68 These two themes consumed around 450 of the volume's 600 pages. There, concepts familiar from the early 1960s persisted, even as African political independence stepped onto firmer footing. 'The true Africa ... still stands!' Engelbert Mveng, a Cameroonian theologian, declared, and she was found in venerable, ancient communities that had survived the scourge of European colonial modernity. In preparation for the conference, 'we have questioned' those communities 'by word of mouth and by letter . we have one ambition only - to be faithful to their voice.' Mveng's correspondence with traditional experts had convinced him that African creative activities were governed by set 'laws', and it was by following those laws -'the rock of Negritude' - that 'the peculiar genius of Africa' might be preserved. The political context, the crowd and the setting were quite different from Salisbury 1962, but the sentiments were not.69

The remaining third of the colloquium was novel. Glossed as 'The Current Situation: The Problems of Modern African Art', the organisers in Dakar broke with precedent to entertain contemporary creation, even if the framing of 'modern' as a 'problem' offered a peculiar accent to the proceedings. The Nigerian painter Ben Enwonwu demonstrated some of the intellectual calisthenics that the framing entailed. Like Mvusi, he rejected the Western convention of seeing the artist as someone distinct from society; he believed instead that, as society changed, so too should art. Here Mvusi doubtlessly agreed. Enwonwu went on to offer a clear definition of what contemporary African art ought and ought not to look like, a move Mvusi tended to avoid. For Enwonwu, contemporary African painters should neither imitate the West 'nor copy their old Art'. To his mind, this meant that Africans ought instead to embrace a realism that, according to Mveng, they had never known, and which had fallen out of favour in the West. Enwonwu critiqued Africans like Mvusi who had experimented with abstraction; nonfigurative expression was nothing more than 'modern European expression both in ideas and technique. It is not African.' In Dakar, as in Salisbury and Boston beforehand, commentator after commentator found it impossible to speak on African art without developing a total theory about what African was or was not to be. The idea that the 'journey was the native land' was a concept few shared.70

The fate of real, authentic 'Africa' continued to concern Frank McEwen as well. By 1966 McEwen had resigned from his position at the Rhodesian National Gallery and its carving workshop. The past half-decade had convinced him that African art was in dire straits; as he saw it, traditional art was dead, ruined by urbanisation, migration and industry; 'airport' art was just sad; and Western-style art schools were foreign and inappropriate. He credited the success that he had in promoting soapstone sculpture in Rhodesia to his willingness to let artists find their own way. To his delight, without any guidance his sculptors had work that was undeniably African: bodies were distorted, heads 'bulbous', figures 'giving [the] static pose frequent in African art'. He celebrated this as evidence of an 'inborn pan-African conception, endemic in the life-blood of the continent'. Africa lives! McEwen declared, and it was wonderful. Yet he worried: as long as change continued, 'how long can Africa remain African?'71

Such talk would have made Selby Mvusi squirm. He had flown a jet plane across the continent to attend a meeting in a booming capital. He was a painter who had experimented with abstraction, a South African who had been policed because of his colour, an artist denied access to an easel because of race. All of those experiences were part of what made him African, because an African was who he was and what he wanted to be. For years he had urged audiences to let 'Africa' live. In Dakar, he tried again.

Mvusi's submission, 'Current Revolution and Future Prospects', renewed his call for industry to become be a site of African creativity, given that industry was the engine for the current age. He offered a primer on the subject: beginning in Europe in the eighteenth century, 'man' had begun to look beyond surfaces to see potential in the energy stored within matter. Although this revelation had begun in Europe, the perception of energy within matter was a universal human inheritance, as was the industrial age that resulted. Without naming them specifically, Mvusi thus manoeuvred around African and other intellectuals who argued that Western racism and violence revealed ethical bankruptcy of industrial modernity. Industry was neither bad nor good, it was what societies did with industry that mattered.72

The European experience demonstrated this. Having developed the capacity to produce, Europe then took the wrong path. Mvusi plotted a direct line between the industrial revolution in northern Europe and the advent of European exploitation of the rest of the world, as 'peoples of other lands [were] marshalled to produce ... materials in large and regular quantities' to feed Europe's machines. Europeans were so star-struck by their own achievements that they promoted anti-humanism by using race as an alibi to explain away the 'mechanistic . enslavement' of non-European peoples during the colonial era. In this, Mvusi agreed with many negritude-influenced thinkers who claimed that African humanism neatly complemented cold, European technical proficiency. Yet he did not stop there. There was nothing inherently wrong with technology, machines, industry, or the perception of energy within matter. It was only wrong that, with the advance of technical knowledge and sophistication, Europeans had neglected to consider the ethical dimensions of past 'times now'. Mvusi posed a question to his audience: 'Now that man is no longer called upon to live by the sweat of his brow, how else is he to live?' Through the conscious, engaged, plastic resolution of contemporary life, African industry would begin to respond to this fundamentally moral question.73

In Nairobi he and his colleagues were beginning to think through how precisely and technically Africa would do this. He did not get into specifics in Dakar; instead, he reached for the more probing assertion that by mastering design, Africans would effect the reconstruction of their artistic, creative and ethical worlds. Recall that Mvusi insisted that works of art were only truly great when socially significant, and only truly legible when observers knew enough about the sorts of societies that had signified artists' creations. So it was with the contemporary age. 'Modernity is not the industrial system,' Mvusi averred, 'it is personality determination and realisation effected by men through industrial processes.' People made modernity by taking the tools that they had and making conscious, deliberate use of them to better themselves. It was not enough merely to be alive; one had to live - actively, creatively, probingly. 'Life is not just existence,' Mvusi insisted, 'life is the living it is.'74

As it always had been, and must always be. Standing in the halls of African culture in postcolonial Dakar, Mvusi cautioned his audience not to get too carried away praising some unchanging Africanness: 'Africa must be aware of those carrying gifts in praise of her personality,' because Africans were still developing their selves. The past was irrelevant; its opportunities were already exploited, while the present was overflowing with potential. 'It is in our interest to activate our present personality', he told his audience, and therefore 'our first question is, what is the time now? ... It is not: "What is the African to be at this time?"' To have a stake in the twentieth century, Africa and Africans needed to be of the present: industry in time, not tradition, not race, was their heritage.75

These were the two major strands in Mvusi's thinking as he made his home in Nairobi and developed an iconoclastic vision of what 'postcolonial' ought to mean. Africans needed to be industrious, as they had been, to cultivate social welfare, as they had once done and as European industry had failed to do. He allowed himself a flight into the past. Once, there had been 'people [who] went to the tops of mountains and prayed for rain'. This rainmaking had been good and right - even if 'inquiry' since that time had 'clarified and intensified' mountains' 'rain-making role'. To go to the top of the mountain and make rain was the industry of a past 'time now'. The rain that fell was, in Mvusi's thinking, an artistic or industrial object - its water, the plastic realisation of a human need and human design. Mvusi continued: of course, people knew better in his own time, so they more effectively used what means they had. 'Today, men are lifting mountains and placing them in positions where their functioning is appropriately ordered to coincide with the functioning of other phenomena.' This was ethical industry, 'the better to "make it rain" in the interests of the general welfare.' The processes Mvusi imagined involved machines and the reshaping of landscapes on a scale far exceeding the capabilities of a single person, but these were productive, human processes nonetheless. Mvusi had travelled from a critique of art history through a critique of Europe's industrial past to arrive at a fundamentally optimistic place. He envisioned a capable community, one conscious of the needs, limits and possibilities of its own time and place. He envisioned an Africa redefined and reconstructed on its own terms, as its people lived fully and richly in their present.76Mvusi's paper fitted oddly in the volumes of cultural wisdom that emerged from the Dakar colloquium. No matter - he had work to do. He returned to Nairobi and his syllabus for the 1966 academic year. For the first time, he planned to send his design students out of the classroom and away from the studios. It was time for them to go into the city, to spend time with their contemporaries, to see how they used objects, to assess their limits and their needs.77 The construction of ethical industry was a slow process and it would begin with designers, sensitive and conscious, at work in time, observing the living of life. His mission as a teacher was 'to get the students to win back for themselves ... their sense of person ... not a lost Africanness, but rather consolidating and bringing forward to full capability and productivity the human being' that they were. That living would be what made them African, not any external characteristic or geographic accident. By learning of themselves, they would build both objects and the continent. 'Just what the form of this will be, if and when found, ... will be as much of a surprise to me as it will be to everybody else.' In his own life, 'I will know it in my very sensing of fulfilment' and he hoped that his students would as well. He hoped for his students that they would produce works of 'integrity', creations to sustain society, as once rainmakers had brought forth water from the mountains.78

As the 1967 term began, Mvusi was at last was sensing that fulfilment. The university council was considering a proposal to fund the University of Nairobi programme, something for which he longed. In June, a non-Englishman was coming to examine his students for the first time - a Swede, not an African, but in the on-going quest for independence, 'it is a revolution!'79 Mvusi had started as a painter. His obvious facility with the brush had led him to the United States, Boston, Salisbury, Kumasi and points in between; along the way, he had all but stopped painting. 'The tasks that one encounters [are] immediate and urgent enough' to provide no opportunity for meditative, personal reflection. Now, as his students began their surveys, he was thinking that it might be time to 'be washing up my brushes'. To wash his brushes would be to pause and take a breath. Mvusi had once reflected that his own life between nations proved his assertion that for Africans 'the journey is one's own native land'. By thinking about painting, Mvusi was signalling that, for him, it was now time to rest.80

Selby Mvusi died in a car crash outside Nairobi in December 1967. He was 38 years old.

1 Research for this article was supported by a grant from the Macmillan Center at Yale University. My thanks to archivists in Washington, Durban and Johannesburg, and above all to Elza Miles, who first introduced me to the range of Selby Mvusi's thought. My thanks as well to Jonathan Zilberg, Omar Badsha, Jon Soske, Sean Jacobs, Nancy Jacobs, Diana Jeater, Linda Mvusi, the attendees of NEWSA 2014 and two anonymous Kronos readers for their comments and suggestions. I dedicate this article to my little designer Liya (age 6) who told me this morning that wood shop was her favourite class, and to my Grandpa Henry (passed at age 100), who first taught me that designing and building matters.

2 For more on the conference, see Frank McEwen (ed), Proceedings of the First International Congress of African Culture (Salisbury, Southern Rhodesia: National Gallery of Art, 1962). See also John Russell, 'The Challenge of African Art: The Lessons of the Salisbury Conference', Apollo: The Magazine of the Arts, November 1962, 697-701. [ Links ]

3 Johannesburg Art Gallery (JAG), Neglected Tradition, Binder 8, 9611255, File 1016, Bill Ainslie, interview by Steven Sack, Johannesburg, March 1988, 1-2.

4 See, for example, G.R. Naidoo, America Wants This Gangling, Casual Artist', Drum, June 1958, 85-7. [ Links ]

5 For more on Mvusi's biography, see Elza Miles, The Current of Africa: The Art of Selby Mvusi (Johannesburg: Johannesburg Art Gallery, 1996); see also Elza Miles (ed), Selby Mvusi: To Fly with the North Bird South (Pretoria: UNISA Press, forthcoming, 2015). [ Links ] Mvusi also earns brief biographical mention in E.J. de Jager, Contemporary African Art in South Africa (Cape Town: Struik, 1973). [ Links ]

6 Selby Mvusi, 'Towards a Contemporary Art in Africa' in McEwen (ed), Proceedings, 109-12. [ Links ]

7 Ibid.

8 For more on this era and debates about culture within it, see, among others Andrew Ivaska, Cultured States: Youth, Gender and Modern Style in 1960s Dar es Salaam (Durham NC: Duke University Press, 2011), [ Links ] Jonathon Glassman, War of Words, War of Stones: Racial Thought and Violence in Colonial Zanzibar (Bloomington IN: Indiana University Press, 2011); [ Links ] James Brennan, Taifa: Making Race and Nation in Urban Tanzania (Athens OH: Ohio University Press, 2012); [ Links ] Nate Plageman, Hi-Life Saturday Night: Popular Music and Social Change in Urban Ghana (Bloomington IN: Indiana University Press, 2013); [ Links ] Michael McGovern, Unmasking the State: Making Guinea Modern (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2013); [ Links ] and Elizabeth Harney, In Senghors Shadow: Art, Politics and the Avant Garde in Senegal, 1960-1995 (Durham NC: Duke University Press, 2004). [ Links ]

9 For more on the cultural politics of South Africa during the 1950s, see my 'Two Stories about Art, Education and Beauty in South Africa', American Historical Review, 118, 5, December 2013, 1403-29. Mvusi's relationship with the BICA artists' collective exposed him directly to such thinking; see documents which detail the government's refusal to fund BICA activities because the group's multiracial composition denied inborn cultural specificities. For example, South African National Archives, Pretoria (NAP) UOD Vol 575, x8/7/25, Lily McAdam to Adult Education Committee, Durban, 6 November 1950; and Ibid, 1, Regional Inspector to Secretary of Education, Art and Science, 26 January 1951.

10 JAG, Federated Union of Black Artists (FUBA), Selby Mvusi, Folder 3, Allport to Mvusi, 2 December 1957, 1.

11 For more on Lowenfeld, see my Art of Life in South Africa, chs 3 and 5, forthcoming. Lowenfeld was an Austrian Jewish refugee from Nazi Europe; he taught first at the Hampton Institute before coming to PSU in the late 1940s. The African American muralist and draftsman John Biggers was among his students at Hampton; Mvusi and Biggers would meet in the 1960, when the former expressed his appreciation that Biggers did not overly romanticise or aestheticise 'traditional' Africa in his travel catalogue Ananse: The Web of Life in Africa (Austin TX: University of Texas, 1962). [ Links ] Lowenfeld's best-known work is Creative and Mental Growth: A Textbook on Art Education (New York: Macmillan, 1947), [ Links ] which successive art teachers at the Ndaleni Art School adapted to their syllabus.

12 Killie Campbell Archive, University of KwaZulu-Natal (KC), JW Grossert, File 2, KCM 25567, J.W. Grossert, 'Contemporary Bantu Artists', 12 January 1962, 1.

13 Library of Congress, Washington, DC (LOC), MSS51615, Box 93, Mvusi to Brown, 10 January 1960, 1.

14 For a later iteration of the poem, published when Mvusi's exile was more pronounced, and accented differently for his changed circumstances, see Selby Mvusi, 'The Nightwatchman from Zululand, Africa South: In Exile, 5, 3, April-June 1961, 123-7.

15 On Roy Sieber: http://www.dictionaryofarthistorians.org/sieberr.htm, accessed on 8 September 2014. See also Roy Sieber, Sculpture of Northern Nigeria (New York: Museum of Primitive Art, 1961); [ Links ] and Roy Sieber, Africa, Images and Realities (St. Paul MN: St. Paul Art Center, 1963). [ Links ]

16 JAG, FUBA, Selby Mvusi, Folder 5, Mvusi, 'Exhibition of Paintings by Selby Mvusi', September 1959, 1-2.

17 For the Harmon Foundation, see http://blog.library.si.edu/2013/02/african-american-art-and-the-harmon-foundatin/?utm_source=feedburner&utm_medium=feed&utm_campaign=Feed%3A+SmithsonianLibraries+%28Smithsonian+Libraries%29#.U1kVj-ZdUeb, accessed on 24 April 2014; http://artsedge.kennedy-center.org/interactives/harlem/faces/harmon_foundation.html, accessed on 24 April 2014; and Gary Reynolds and Betty White (eds), Against the Odds: African American Art from the Harmon Foundation (Newark NJ: Newark Museum, 1989). [ Links ] The Library of Congress, which holds a repository of Harmon records, has put a film of a 1930s Harmon exhibition and prize-giving on YouTube. Watch it here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rJMDnkeL00k.

18 On Onwonwu, see Sylvester Ogbechie, Ben Enwonwu: The Making of an African Modernist (Rochester NY: University of Rochester Press, 2008). [ Links ] See also Evelyn Brown (ed), Africa's Contemporary Art and Artists (New York: Harmon Foundation, 1966). [ Links ]

19 Forrester B. Washington, Contemporary Artists of Africa (New York: Harmon Foundation, 1960). [ Links ]

20 LOC, MSS51615, Box 93, Mvusi to Brown, 10 January 1960, 1, 1-2.

21 JAG, Neglected Tradition, Binder 8, 961-1255, File 1016, Bill Ainslie, interview by Steven Sack, Johannesburg, March 1988, 1-2.

22 LOC, MSS51615, 1, Mvusi to Brown, 11 August 1960.

23 JAG, FUBA, Selby Mvusi, Folder 9, Selby Mvusi, 'The Arts: An Introduction to Appreciation', 20 August 1960, 1-4.

24 JAG, FUBA, Selby Mvusi, Folder 5, Mvusi, 'Exhibition of Paintings by Selby Mvusi', September 1959, 1-2.

25 JAG, FUBA, Selby Mvusi, Folder 9, Selby Mvusi, 'The Arts: An Introduction to Appreciation', 20 August 1960, 1-4.

26 LOC, MSS51615, Folder 93, Mvusi to Brown, 28 May 1961, 1. See also, 'Back Home with His M.Ed.', World, 21 January 1961, 2.

27 LOC, MSS51615, Folder 93, Brown to Mvusi, 14 July 1961, 1.

28 For William Fagg, http://www.dictionaryofarthistorians.org/faggw.htm. Also, see his text to accompany Eliot Elisofson, The Sculpture of Africa (New York: Praeger, 1958).

29 Africa and the United States: Images and Realities: Report of the Eighth National Conference of the United States National Commission for UNESCO, October 1961, 58-60.

30 JAG, FUBA, Selby Mvusi, Folder 9, Selby Mvusi, 'The Social Significance of African Art and Music', October 1961, 1-3.

31 Ibid.

32 JAG, FUBA, Selby Mvusi, Folder 9, Selby Mvusi, African Art in the United States', October 1961, 2.

33 Ibid, Selby Mvusi, 'Contemporary African Art: Images and Realities', October 1961, 3.

34 LOC, MSS51615, Folder 93, 1-2, Mvusi to Brown, 28 May 1964.

35 For an essential study of the relationship between Southern African liberation movements and Nkrumah's Ghana, see Jeffrey Ahlman, 'Road to Ghana: Nkrumah, Southern Africa, and the Eclipse of a Decolonizing Africa', Kronos: Southern African Histories, 37, 2011.

36 LOC, MSS51615, Folder 93, Mvusi to Brown, 28 May 1964, 1.

37 JAG, FUBA, Selby Mvusi, Folder 3, Kojo Fusu to Leslie Spiro, 11 October 1994, 1.

38 LOC, MSS51615, Folder 93, Mvusi to Brown, 28 May 1964, 2.

39 Frank McEwen, 'Opening Ceremony' in Frank McEwen (ed), Proceedings, 11. McEwen is a fascinating figure, who dominated the politics of art production in 1960s Rhodesia and left an important legacy in regional workshop culture. For more on McEwen, see Elizabeth Morton, 'Frank McEwen and Joram Mariga: Patron and Artist in the Rhodesian Workshop School Setting, Zimbabwe' in Sydney Kasfir and Till Forster (eds), African Art and Agency in the Workshop (Bloomington IN: Indiana University Press, 2013), 174-98. See also Jonathan Zilberg, 'Zimbabwean Stone Sculpture: The Invention of a Shona Tradition' (Unpublished PhD thesis, University of Illinois, 1996).

40 S.O. Biobaku, 'Address', in McEwen (ed), Proceedings, 13.

41 William Fagg, discussion in McEwen (ed), Proceedings, 14.

42 Cited in Bill Ainslie, 'We Are Overlooking Some of Our Most Talented Artists', Bulawayo Weekend Chronicle, 22 September 1961, n.p. (JAG, Archives, Bill Ainslie, Clippings). [ Links ]

43 The 1958 volume Sculpture of Africa made Fagg's regional bias apparent: the inside cover featured a map of the continent with the West and Equatorial Africa highlighted in brown, with notable tribes indicated. South Africa was an empty void. William Fagg and Eliot Eliofson, Sculpture of Africa (New York: Praeger, 1958). For the question of South Africa's place in 'traditional' African artistry, see J.W. Grossert, Walter Battiss, G.H. Franz and H.P. Junod (eds), The Art of Africa (Pietermaritzburg: Shuter and Shooter, 1958); and my Art of Life in South Africa, chap 3.

44 According to the art historian Jonathan Zilberg, Mvusi penned an angry letter to Barr after his passive visit to Salisbury, which I have been unable to locate.

45 LOC, MSS51615, Folder 93, Mvusi to Brown, 29 August 1962, 1.

46 Barrie Reynolds, 'The African Craft Village, Livingstone' in McEwen (ed), Proceedings, 37-40.

47 Selby Mvusi, 'Towards a Contemporary Art in Africa' in McEwen (ed), Proceedings, 109-112. For a slightly different version of the same paper, see JAG, FUBA, Selby Mvusi, Folder 9.

48 Ibid.

49 LOC, MSS51615, Folder 93, 2, Mvusi to Brown, 28 May 1964.

50 Ibid, 1-4, Mvusi to Brown, 30 March 1964; Ibid, Mvusi to Brown, 6 April 1964, 1-4.

51 San Francisco State University, San Francisco CA (SFSU), Nathan Shapira Archive, University of Nairobi File, Mvusi, 'Educating Designers Today: Prescriptive Perspective not Perspective Prescription', 16 September 1965, 1-2.

52 JAG, FUBA, Selby Mvusi, Folder 9, Mvusi, 'The Education of Industrial Designers in Low-Income Countries, March 1964, 7-8.

53 LOC, MSS51615, Folder 93, 3, Mvusi to Brown, 30 March 1964.

54 JAG, FUBA, Selby Mvusi, Folder 9, Mvusi, 'The Education of Industrial Designers', 1-3, 38.

55 LOC, MSS51615, Folder 93, 4, Mvusi to Brown, 30 March 1964.

56 LOC, MSS51615, Folder 93, Mvusi to Brown, 28 May 1964, 1.

57 See ibid, Evelyn Brown (ed), 'Selby Mvusi's Proposal on Industrial Art', 26 October 1964. These conversations were largely with the Rockefeller Foundation, which was playing an increasingly important role in channelling money to the cause of free expression and modernisation across the third world. See Frances Saunders' justly renowned study, The Cultural Cold War: The CIA and the World of Arts and Letters (New York: New, 2001), for more.

58 LOC, MSS51615, Folder 93, Mvusi to Brown, 16 July 1964, 1-3.

59 For much more on the Margaret Trowell School, see Sunanda Sanyal, 'Being Modern: Identity Debates and Makerere's Art School in the 1960s' in Gitta Salami and Monica Visona (eds), A Companion to Modern African Art (Oxford: Wiley Blackwell, 2013), 255-75.

60 LOC, MSS51615, Folder 93, Mvusi to Brown, 16 July 1964, 1-3. See also http://sifa.mak.ac.ug/history.html, accessed 9 September 2014.

61 SFSU, Nathan Shapira Archive, University of Nairobi File, Baynes to International Council Societies of Industrial Design, 20 November 1964, 1. See also SFSU, Nathan Shapira Archive, Selby Mvusi and Derek Morgan, 'Foundation Course: Year One/Term One, [December 1965?], 1-2.

62 SFSU, Nathan Shapira Archive, University of Nairobi File, Mvusi, 'Educating Designers Today', 12.

63 See Gary Wilder, The French Imperial Nation State: Négritude and Colonial Humanisms Between the Two World Wars (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005) especially Part Two. For Senghor, see Souleymane Bachir Diagne, African Art as Philosophy: Senghor, Bergson and the Idea of Negritude (Chicago: Seagull, 2012).

64 SFSU, Nathan Shapira Archive, University of Nairobi File, Mvusi, 'Educating Designers Today', 12.

65 JAG, FUBA, Selby Mvusi, Folder 9, Mvusi, 'The Things We Buy', [1965?], 3, 5, 12.

66 Ibid.

67 See Philip Scipion, 'New Developments in French-Speaking Africa', Civilisations, 16, 2, 1966, 253-66; Ousmane Hanchard, 'First World Festival of Black Arts, 1966' in Salami and Visona, Companion. Also https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YVZJwvzt8dY, accessed on 9 September 2014.

68 Zilberg argues that the 1966 meeting was consciously modelled on the Rhodesian precedent. See 'Modern Painters: Afro-German Expressionism at the Rhodes National Gallery, 1957-1963', unpublished MS in the author's possession.

69 Engelbert Mveng, 'The Function and Significance of Negro Art in the Life of the Peoples of Black Africa' in Presence Africaine (ed), Colloquium: Function and Significance of African Negro Art in the Life of the People and for the People (Paris: Presence Africaine, 1966), 17, 24.

70 Ben Enwonwu, 'The African View of Art and Some Problems Facing the African Artist' in Presence Africaine (ed), Colloquium, 418-24.

71 Frank McEwen, Modern African Painting and Sculpture' in Presence Africaine (ed), Colloquium, 427-37.

72 JAG, FUBA , Selby Mvusi, Folder 9, Selby Mvusi, 'Current Revolution and Future Prospects', March 1966, 58-61.

73 Ibid, 61, 64-5.

74 Ibid, 66.

75 Ibid, 69.

76 Ibid, 73.

77 SFSU, Nathan Shapira Archive, University of Nairobi File, Mvusi, 'Man/Environment Interaction Project', March 1967, 1-5.

78 LOC, MSS51615, Folder 93, Mvusi to Brown, 27 August 1965, 2.

79 Ibid, Mvusi to Brown, 5 January 1967, 2.

80 Ibid, Mvusi to Brown, 28 May 1964, 2; Ibid, Mvusi to Brown, 5 January 1967, 2.