Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Kronos

versão On-line ISSN 2309-9585

versão impressa ISSN 0259-0190

Kronos vol.41 no.1 Cape Town Nov. 2015

ARTICLES

'Facts about Ourselves': Negotiating sexual knowledge in early twentieth-century South Africa

S.E. Duff

Wits Institute for Social and Economic Research, University of the Witwatersrand

ABSTRACT

The focus of this article is on the introduction of sex education to middle-class white children in South Africa during the 1920s and 1930s. It argues that 'Facts about Ourselves for Growing Girls and Boys', a pamphlet put out by the Johannesburg Public Health Department in 1934, opens a window onto the ways in which sexual knowledge was mobilised to teach white, middle-class children correct forms of heterosexuality, as well as to assert and patrol boundaries between these children and African adults, particularly men. Until relatively recently, the field of the history of sexuality has been dominated by efforts to retrieve the histories of marginalised groups. This risks implying that heterosexuality is not historically contingent - that it is fixed, unchanging, and not inflected by race, class and gender. An analysis of 'Facts about Ourselves' and the mobilisation of sexual knowledge becomes, then, a means of tracing the history of the construction of 'normal' sexuality and so historicising heterosexuality.

Keywords: Sex education, childhood, youth, race, Red Cross, advice manuals, Johannesburg, eugenics

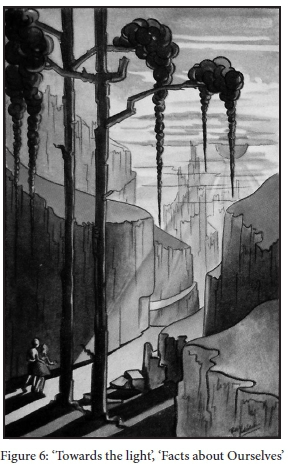

In 1934, the Red Cross and the Johannesburg Public Health Department published a slim illustrated pamphlet titled 'Facts about Ourselves for Growing Boys and Girls'.1Written by R.P.H. West, a school teacher, its purpose was, as the caption for its first illustration noted, to lead readers 'into the light' of knowledge. In the foreword, the city's medical officer of health Dr A.J. Milne explained that the 'natural reticence' and 'comparative ignorance' of parents had resulted in widespread youthful unfamiliarity with 'the facts pertaining to human reproduction.'2 The pamphlet was a simple and 'authoritative' guide intended to provide clear and unambiguous knowledge about sex and sexual reproduction to young white readers between the ages of ten and twelve years, as well as to parents who could use the text to instruct their children.3

But 'Facts about Ourselves' intended far more than simply conveying information about sexual reproduction. As Milne added, sex education 'is not only of considerable importance to the future welfare of the country, but is one which has a very direct bearing on the solution of our Poor White Problem.'4 With its references to separate bedrooms for siblings, servants, and trips to the 'bioscope' (cinema), the manual was intended for middle-class white children. Its final illustration, captioned 'Radiant Health', depicts nicely dressed, healthy children with buckets and spades at the beach, invoking a particularly middle-class ideal of childhood seaside holidays.5 Its purpose was to demonstrate to these readers that the future security and prosperity of South Africa rested in strong, stable nuclear families presided over by monogamous, heterosexual, married parents. Moreover, in devoting several pages to the sexual threat posed to white girls by black men, the manual made clear to young white South Africans that any future presided over by the country's black population was to be avoided at all costs.

Historians of southern Africa have produced a rich body of work on sex and sexuality in the region, demonstrating convincingly how sex education manuals and other interventions - ranging from mothers' prayer unions and hostels for girls, to organisations like the Purity League and the Pathfinders and Wayfarers - were aimed at controlling the apparently dangerous sexuality of urban African youth during the 1920s and 1930s. Urbanisation and the influence of Christian missionaries meant that processes of sexual socialisation in many African societies were undergoing considerable change. New ways of marking the passage from childhood to youth and to adulthood had to be found. Natasha Erlank has shown, too, how texts like the Church of England's 'God, Love, and Marriage' presented young African readers with an understanding of sexuality as a positive force, essential to the making of happy families, but only as long as it occurred within sober, faithful heterosexual marriage.6But, thus far, little attention has been devoted to the teaching of sex education to children who were not African, and beyond the period before the Second World War.7Indeed, despite the existence of a complex body of work on histories of sex education in the West,8 little seems to have been written on the Global South.9 In keeping with the scholarship on the subject, I define sex education broadly, including topics such as human reproduction, adolescence and puberty, relationships, contraception and sexually transmitted diseases.

Debates over the introduction of formal sex education in South African schools during and after the conclusion of the First World War paralleled similar developments abroad. Most pressingly, post-1919 concerns about an apparent increase in rates of syphilis infection globally drove national sex education campaigns. At the same time, sex education spoke to eugenicist interest in improving the national stock. If taught to youth at school, sex education could become an important tool in improving the physical and moral health of the nation. Authors agreed that sex education was a means of channelling youth sexuality into monogamous, heterosexual marriage.10 Connected to this, sex education was held up as an important means of controlling apparently dangerous youth sexuality during a period of major social, political and economic change. This confluence of factors - efforts to reduce rates of syphilis infection, attempts to shore up the health of the nation, and concern about the social sexualisation of youth - during the early twentieth century produced the circumstances in which an increasing number of public health specialists, medical professionals, social reformers and educationalists began to advocate the introduction of formal sex education in schools. Although these classes tended only to be rolled out later in the century - in South Africa, a subject called 'guidance' was added to the curricula of schools for whites in 1967, and black schools in 1981 - between the wars there was widespread discussion about the nature and content of formal sex education, and a large number of sex education manuals were produced.11

Before 1939, when the influential educationalist E.G. Malherbe initiated discussions about including sex education in school curricula, formal sex education for white children was provided on a fairly ad hoc basis, depending on the interests of teachers and parents.12 Janie Malherbe, a journalist and the wife of E.G. Malherbe, observed that advice for young brides in early twentieth-century South Africa was difficult to come by.13 There is, though, evidence to suggest that some information about 'sex hygiene' was made available to white youth. For instance, in 1913 the Woman's Outlook (the official publication of the South African women's suffrage movement) recommended to its readers the British publication The Three Gifts of Life by Nellie M Smith: 'an excellent little book on hygiene designed to help girls to a right understanding of the facts and phenomena of life.'14 It is also likely that the well-travelled, well-read and multilingual colonial upper class encountered and bought for circulation among friends at home, the guides to married life, often written for young brides,15 which became popular abroad during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.16 But 'Facts about Ourselves' was among the first sex education manuals written specifically for South African children, to be distributed among as many of them as possible. Copies were distributed among the members of the Transvaal Teachers' Association and the province's public health authorities.17 As in the United States, Britain and parts of Western Europe, sex education for children was the logical outcome of the provision of sex education for adults during and after the post-First World War syphilis pandemic.18 For instance, in 1924, in the eighth annual report of the Transvaal Council for Combating Venereal Disease, Dr J.A. Mitchell, chief medical officer of the Union of South Africa, called for the greater availability of sex education for children at school. 'Children were not fools,' he remarked. It was 'quite practicable' to teach them enough to understand the dangers of contracting sexually transmitted diseases (STDs), for instance: 'there was no time for false modesty.'19 The Red Cross, the co-publisher of 'Facts about Ourselves', was the successor to a range of smaller bodies that had worked against the spread of sexually transmitted disease since the 1910s.20 In 1937 it established a National Committee for Health Education, which, alongside the Union's Department of Public Health and in collaboration with the New Education Fellowship, disseminated information to adults and children on a range of subjects, including sex education and information (in the form of public information films, lectures and leaflets) on STDs.21

To some extent, 'Facts about Ourselves' is typical of the advice literature published during the 1920s and 1930s internationally. Writing about the United States, Julian B. Carter notes that the authors of these manuals were caught in a moral and epistemological bind: they desired to 'shape sexual activity' at the same time as they feared 'stimulating' it in their readers. After all, since at least the eighteenth century, much pornography had been disguised as sex education.22 Connected to this, sex education manuals for children needed to avoid obscenity legislation.23 In his note to parents, West reassures his readers that 'Facts about Ourselves' will not provide children with a 'thrill'. Its purpose is to offer sober, serious information to the 'genuine seeker after truth'.24 So how did manuals encourage some forms of sexuality while actively discouraging others?25

As Danielle Egan and Gail Hawkes observe, this complicated negotiation was underpinned by a contradictory framing of childhood sexuality which assumed an asexual child, 'while simultaneously creating various techniques to control and manage its sexuality once initiated.'26 This anxiety about the simultaneously asexual, yet potentially sexual, child was produced partly by a shift in the nature of childhood and youth during the nineteenth century. In 1904 the distinguished American psychologist G. Stanley Hall published his two-volume magnum opus Adolescence, the first study to identify a distinct stage of human development between childhood and adulthood. But while Hall may have popularised the term adolescence, his book named a phenomenon which had surfaced forty or fifty years previously. Since at least the middle of the nineteenth century, childhood and children's dependence on their parents had gradually lengthened in most industrialising societies. A confluence of factors - including the gradual lowering of the age at which puberty commenced as a result of improved nutrition, the sharper segregation of adults and children as the latter spent more of their time in school, as well as the lengthening of education and apprenticeships which caused young men and women to delay marriage - resulted in the emergence of a new age category. 27 In the English-speaking world, the terms 'girl' and 'boy' came to include young people in their teens who were on the cusp of sexual maturity, but still in fulltime education and occupying a subordinate status within households.28 Adolescence was embedded in the social and racial politics of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. As the children of parents who could afford not to rely on the wage-earning labour of their offspring, these first adolescents were overwhelmingly white and middle class.29 (The emergence of the teenager in the United States during the late 1930s was also initially a middle-class phenomenon.)30Similarly, the modernisation of childhood - the process by which childhoods became progressively more regularised and regulated - and the formation of the modern nuclear family were products of a range of forces at work over the course of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, including rising middle-class incomes, the gradual separation of the household and workplace, and reconceptualisations of love, domesticity and femininity.31

Accompanying this change was a growing concern about how to respond to childhood and adolescent sexuality. Hall, like so many nineteenth-century medical professionals, biologists, clergymen and moralists,32 was preoccupied with masturbation, believing that masturbation in adolescence foreshadowed adult moral and sexual degeneracy, and physical decline.33 Foucault argues that the nature of nuclear families and increasingly closely monitored middle-class childhoods were fundamentally informed by concern about the masturbating child. Medical anxiety about masturbation, and particularly childhood masturbation, meant that the child's body became 'the object of [parents'] permanent attention, transforming the family space into 'a space of continual surveillance'.34 Childrearing guides recommended that parents closely monitor their children's behaviour at all hours of the day.35 Although the association of youth with romantic ardour or sexual curiosity long preceded the Enlightenment,36 Foucault is useful here for exploring anxieties about sexualised and sexually curious children during this period. The powerful discourse of the innocent child - heavily influenced by Romanticism and evangelicalism - informed the child-saving movement's efforts to transform childhood into a period of play- and school-filled seclusion away from wage-earning labour and under strict adult supervision. Adolescents, suggested Hall and others, possessed a burgeoning but yet uncontrolled sexuality, something deemed to be at odds with childhood innocence and which, as a result, needed to be contained and controlled for children to grow up into morally continent adults.37

This early association of sexual danger with the category of adolescence was one of the prime motivating forces for the introduction of formal sex education during the early twentieth century. During periods of profound social change, and especially urbanisation, adults and parents worried that, as Jeffrey Moran writes about the United States in the early decades of the nineteenth century, 'traditional mechanisms of cultural transmission had broken down.'38 Adolescents were without the usual guidance and surveillance that could both contain their behaviour and teach them self-control. The emergence of the guidebook - exemplified by the success of the British author Samuel Smiles - coincided with the rapid expansion of the middle class globally during the nineteenth century.39 It is little wonder, then, that numbers of sex education manuals and other interventions designed to shape adolescents into sober, self-regulating adults multiplied during periods of urbanisation, economic instability and social uncertainty.

In other words, one of the key means of controlling, particularly, adolescent sexuality - 'an especially dense transfer point for relations of power', in Foucault's words - was through the production of knowledge.40 As Roy Porter and Lesley Hall note, sexuality is 'produced by the production of knowledge about it. They add: 'sexuality could not exist in the culture without words, images, metaphors and symbols to represent it.'41 Sex education manuals for children and youth were intended both to shape attitudes towards sex, sexuality and relationships as well as to inculcate self-control and self-mastery in adolescents. Written by medical professionals, teachers and other specialists, they created an expert narrative of what should constitute appropriate sexual behaviour - a narrative meant to supersede the knowledge passed between children, and between children and adults. While nineteenth-century manuals (including childrearing guides published by Dutch Reformed Church (DRC) ministers) appealed to readers in religious terms, from the turn of the twentieth century authors invoked medicine, biology, psychology and the reliance of the state on the moral and physical health of individuals, to convince their readers (and their readers' parents) of the truth of their claims and the need to do what the manuals demanded.42 A potent mixture of patriotism and scientific expertise gave the authors not only the power to reveal sensitive information about human reproduction - in the process assisting in the construction of a discourse on 'normal' heterosexuality - but the ability to choose what of this knowledge to conceal. Knowledge itself was dangerous and needed careful handling.43

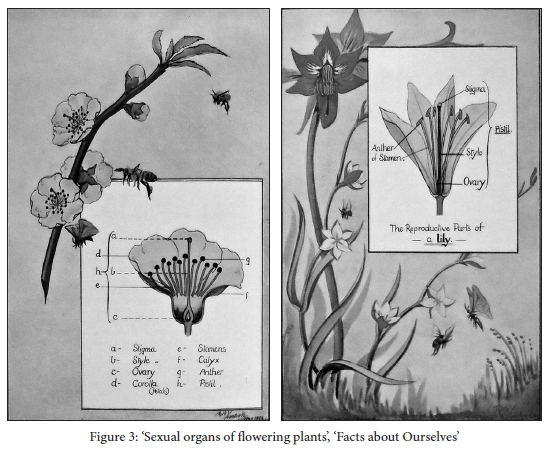

The first twentieth-century sex education manuals negotiated this question of what knowledge should be made available to youth by demonstrating to their readers the potentially deleterious effects of sex outside marriage (this included sex before marriage and sex with sex workers). It was not uncommon for these manuals to include photographs and detailed descriptions of the symptoms and physical manifestations of syphilis and gonorrhoea. This information was intended both to shock young readers out of having sex before marriage (as Carter notes, the manuals could best be described as being about the 'facts of death' rather than the 'facts of life'),44 as well as to 'call out and develop their nascent parental urges to cherish and care for children.'45 Boys were urged to control their urges and to remain pure before marriage, largely out of respect for their virginal, innocent wives. Girls were exhorted to understand that their education was in the service of transforming them into caring and intelligent mothers. However, from the mid-1920s, manuals changed, emphasising both the sanctity of marriage and the vital importance of sex and the production of healthy children to the future stability and prosperity of the nation. They were also informed by recent arguments about the significance of sex to happy, companionate marriages.46 These manuals emphasised not contagion but, rather, development: that sex was part of a (God-given) life force which animated life on earth. This was a positive story about life and new beginnings. In this interpretation the family - human or otherwise - was at the origin of all forms of life.

'Facts about Ourselves' falls into this second group of manuals. Careful not to divulge explicit information about sexual intercourse, it devotes only three pages out of thirty-one to human reproduction. One paragraph describes in cold, clinical detail the 'sex act' ('The penis of the male has to enter the vagina of the female, and nature then causes the necessary activity whereby the germ cells leave the male and endeavour to unite with the cells of the female') and is followed by a discussion of why West's readers should learn to control the 'sex instinct.'47 Those who give in to lust are at risk of bringing shame to themselves or producing illegitimate children, and of contracting 'the most terrible diseases from which man has suffered.'48 Implicit in this warning was a fear of masturbation. Although the medical and psychiatric professions had ceased linking masturbation with disease and madness at the end of the previous century, the belief that masturbation was in some way an unclean or degenerative activity was still widespread - and present, for instance, in the widely read publications of the Scouts and Guides.49 For all his purported desire to 'make clear' knowledge about sexual reproduction, West shrouds it in religious mystery, referring frequently to God and the Bible. His discussion of the uterus, for instance, begins with a reference to the womb in hymns.50 He advises his readers against thinking or talking about sex: 'It is wise to avoid undue interest in the sex organs, and a good way to do that is by turning your thoughts elsewhere to healthy occupations and interests.'51

With regard to talk on sex matters among yourselves, you would be well advised to say too little than too much. At the same time, with a little reasonable talk with your special friends of the same sex you may be able to help one another over little difficulties. But do not pursue the subject just for the sake of talking about it ... at all times, avoid silly or unnecessary talk about so big and so sacred a subject.52

Sex, in other words, is too complex a subject to be communicated fully to young people - who should, in any case, display as little interest in the subject as possible. 'Facts about Ourselves' attempts to resolve the tension between explaining human reproduction and making available (some) knowledge about sex and sexuality by encouraging wilful ignorance in the pamphlet's readers, and also by invoking the potentially devastating consequences of too much sexual curiosity. In doing so, the manual acknowledges that it competes with other forms of sexual knowledge. Its apparently scientific underpinnings and appeals to Christianity position this knowledge as legitimate.

This question of what constituted the correct forms of sexual knowledge was foremost in the minds of moral and social reformers in the 1920s and 1930s. In South Africa, the spread of Christianity and mass urbanisation changed the processes of sexual socialisation that occurred within many African societies in the region. As research conducted by social anthropologists during the first half of the twentieth century suggests, in some southern African pre- and early-colonial African societies, sex education, broadly defined, was woven into the processes that facilitated a person's shift from childhood to youth, to adulthood.53 The onset of puberty allowed girls and boys entry into new age groups where information about relationships, sex and contraception was circulated. These rites of passage not only provided useful and necessary information about adult sexuality but also, as Glaser and Delius argue, allowed communities 'to negotiate the tricky terrain between acknowledged adolescent sexuality and the risk of pre-marital pregnancy'. Youth were allowed 'limited forms of sexual release' - such as non-penetrative thigh sex (metsha in Xhosa and hlobongo in Zulu) - but in a context where there were strong sanctions against pregnancy out of wedlock, and where peers monitored and managed relationships between unmarried men and women.54

With urbanisation, the missionaries, clergy and public health officials cast around for ways to provide sexual socialisation to a population of young men and women who had not received any form of sex education in rural households.55 Disapproving of the sharing of sexual knowledge in rural households, this group of social reformers aimed to shape and, crucially, to limit the kinds of information about sex and sexuality available to urban African youth. Ultimately, their purpose was to transform attitudes towards sex and sexuality: young men and women were to abstain from pre- or extramarital sex, and their rejection of practices such as thigh sex implied that only penetrative sex was an appropriate form of sexual release.56 Mothers' prayer unions, compounds for young African women in cities, and organisations like the Purity League and the Pathfinders and Wayfarers (versions of the Scouts and Guides for African boys and girls) were intended to socialise young Africans, teaching them the value of sexual continence.57 Like 'Facts about Ourselves', sex education manuals for African youth provided rudimentary information about puberty and considerably more discussion of what constituted respectable, sober adulthood. But unlike sex education for white children, these church-sanctioned sex education manuals, written overwhelmingly by clergy and published mainly by missionary presses, were more like those manuals produced abroad during the nineteenth century, in their appeals to their readers not to engage in premarital sex on religious grounds.58

As in the United States, for instance, sex education in South Africa was raced: African and white children received sex education from different organisations and with differing emphasis and content.59 While sex education manuals for African youth were intended primarily to shape a respectable African urban working- and middle-class, as Milne's comments drawing attention to the link between sex education and the solution of white poverty in the foreword to 'Facts about Ourselves' demonstrated, the introduction of sex education manuals for white children was linked closely to eugenicist concerns about the health and welfare of the white race. Estimates as to the number of whites living in poverty in the early 1930s varied between a quarter and a third, as suggested by the Carnegie Commission of Investigation on the Poor White Question in South Africa (1932).60 Former tenant farmers and their families who had seen their livelihoods vanish during the country's rapid industrialisation after 1910 settled in cities, living in racially mixed slums and overcrowded ramshackle housing and competing with blacks - themselves also recent arrivals from the countryside - for the same unskilled and semiskilled jobs. Like young African men and women, poor white youth were also away from the authority of parents or elders. These young people were deemed to be particularly at risk of engaging in interracial sex and contracting venereal disease. The Union was at risk of a breakdown in the stable nuclear family, warned ministers, politicians and social workers. White control over the country's politics and economic resources was thrown into question by poor whiteism.61

In some ways, efforts to provide health services, contraceptives and information to mothers about sex, pregnancy and childrearing, and state interest in maternal health and reproduction were by no means unique to South Africa during this period.62 New Zealand curbed Asian immigration and supported Truby King's mothercraft centres in an effort to grow the size of the white population.63 Depopulation and high infant mortality rates in the Belgian Congo helped to boost the colonial state's willingness to support pronatalist organisations working with African mothers.64 Survival of the nation depended on its mothers and children. Moreover, in South Africa, concerns about poor whites - particularly in rural areas - had been aired since the 1880s and 1890s,65 and there had been panics over prostitution, black peril and homosexuality in mining compounds in the late 1800s and early 1900s,66 but the solutions offered to these crises in the 1920s and 1930s differed substantially from those in the previous century. The state became interested in finding ways, often grounded in science, to improve the health and size of the white population and, through this, producing knowledge about sex and sexuality which were, as Glaser notes, 'intimately related to population growth and therefore the management of social resources'.67

In other words, providing sex education to middle-class white children was as important to the state as interventions into the sexual health and behaviour of poor white youth and women. Although, as Susanne Klausen has demonstrated, poor white women were the particular targets of work to make contraception available to assist in birth spacing to reduce the size of poor families,68 the influential synod of the Dutch Reformed Church elected not to condemn birth control at is meeting in 1932.69 Contraception was not, then, only for poor women. Since the 1910s, a growing number of calls had been made to provide sex education, particularly (but not exclusively) to white middle-class girls - the future mothers of the nation. In 1915, Woman's Outlook had suggested that girls be provided with classes in 'sex hygiene' as a means of counteracting the 'prevailing [sexual] immorality'.70 During the 1920s and 1930s, Janie Malherbe was one of several white middle-class journalists who argued in popular publications that white children needed thorough, intelligent sex education. She wrote that women could only be expected to become good mothers if they were well acquainted with information regarding sex, contraception, pregnancy and childbirth.71

There is evidence to suggest that mothercraft - a subject which focused on the care of babies and young children and household management, and occasionally provided some sex education - was taught in both English- and Afrikaans-medium schools, particularly those attracting mainly middle-class pupils. The Girl Guides and other organisations visited the Mothercraft Training Centre in Cape Town to receive instruction on pregnancy and the care of infants.72 Some branches of the Afrikaanse Christelike Vrouevereeniging (Afrikaans Christian Women's Society) encouraged members to provide their children, particularly their daughters, with suitable reading.73 This emphasis on providing young women with information and training stemmed from the view that it was science, particularly medical science, that would improve the quality of white South Africans' health. As mothers needed to place themselves and their babies in the care of trained medical professionals, so parents and teachers needed to turn to experts for help with sex education for white children.74 In 1937 the South African National Council for Child Welfare argued that 'whilst the duty of parents is to give sex teaching ... the teacher and parent are often ignorant of the best method of approach'. As a result of this, 'the Council is of the opinion that to enable sex teaching to be given satisfactorily, physiology should be included in the school curriculum and sex teaching given in the course of general lessons by experts who can advise parents desiring such advice.'75

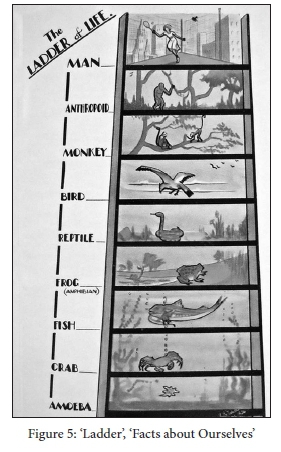

'Facts about Ourselves' was the product of the Red Cross's interest in disseminating accurate, scientific sex education written by an expert. The scientific theory that underpinned this - and other - manuals was the recapitulation doctrine, which had been popular among biologists and psychologists interested in human and child development since the end of the nineteenth century. The doctrine posited that the 'individual child's development constituted a compressed process of reliving all the earlier stages of ancestral evolution.'76 In other words, as humans had evolved from early hominids to Homo sapiens sapiens, so children relived this evolution in their own growth into adulthood. Indeed, Hall used the idea to explain the position of adolescence in growing up. As Carter observes, for authors of sex education manuals the doctrine offered a simultaneously evasive and expansive understanding of sex education. It positioned children's development within the broader context of human evolution and also allowed authors to focus on the reproductive systems of other life forms.77 These are the manuals that taught children, quite literally, about the 'birds and the bees'. 'Facts about Ourselves' devotes more space to the sexual reproduction of chickens and flowering plants than it does humans. Demonstrating its debt to the recapitulation doctrine, the pamphlet opens with a discussion of life as a 'great long ladder' at the top of which is 'Man' and at the bottom 'is a tiny atom or speck of life called an amoeba'.78 Mammals are superior to all forms of life because they care for their young, and human beings are closest of all to God because they are self-conscious and able to control their instincts.79 These instincts are crucial to self-preservation and, equally important, to 'our desire to preserve our race' which is, argues West, 'just as strong as our desire to preserve ourselves.' West explains:

The chief way in which this type of instinct works is in connection with children. All of us, as we get older, wish to have children of our own ... Nature has put into us this great desire to be the parents of children in order that the race to which we belong may continue in strength and in increasing numbers . To have children and to do well for them better the race to which you belong, and it is your duty to help your race to progress.80

However, these instincts needed to be carefully controlled, as West's urging of his readers not to think about sex or their sex organs suggested. The sex instinct was vital for the preservation of the race, but giving in to this instinct (having sex before or outside of marriage, for instance) had very serious consequences too. In Adolescence, Hall's preoccupation with the rearing of white middle-class adolescent boys stemmed largely from his concern that they learn to control their carnal urges. For Hall, the purpose of adolescence was to teach self-control, or mastery of the emotions and physical instincts. Masturbation was to be discouraged at all costs.81West's argument that young readers should 'turn their thoughts' from sex was an implicit warning against masturbation. The Scouts and Guides were also taught about the dangers of masturbation, and the Pathfinders and Wayfarers were encouraged to learn cleanliness, purity and self-control. The last of these characteristics was linked strongly to the management of sexual urges. Intense debate over the need to keep African Pathfinders and Wayfarers strictly segregated from white Scouts and Guides was grounded in the view that African youth had greater difficulty remaining sexually continent.82

In its use of the recapitulation doctrine to explain children's development from childhood into puberty and adolescence, and their position in relation to all other forms of life on earth, the pamphlet also invokes a cluster of ideas about racial hierarchies. The doctrine held that race was embedded in biology. On West's long ladder, although humans may have occupied the top run, readers were left in no doubt that Europeans were at the very pinnacle of that ladder. Africans were slightly lower. West explained to his readers:

In South Africa we have a huge population of natives. They outnumber the Europeans by, roughly, four to one. Many great thinkers tell us that we are two thousand years older than our natives . In other words, we, as Europeans, have the great advantage of two thousand years of civilisation behind us, with all that it means in knowledge, self-control, and care for others . Their instincts are exactly the same as ours, but it is not reasonable or just to expect that they will have the same control over the working of them.83

West's warning against the sexual danger posed by African men was strongly influenced by anxieties about black peril during the early twentieth century.84 Noting that South Africa has a 'huge population of natives' who 'outnumber Europeans by, roughly, four to one', West explains here that Europeans are culturally and socially more evolved than Africans. He pays particular attention to the policing of relationships between whites girls and African men:

The girls are perhaps asleep or else only partly awake, and their bodies carelessly covered by the bedclothes. The temptation to the native may be far more severe than is ever realised, and any wrong-doing on his part would be very terrible to a girl, while the law visits upon him a very dreadful punishment. Cases of assault have occurred on many occasions, and it is our bounden duty to avoid even the possibility of such a thing. No native should be allowed in a bedroom whilst a girl is in it, whether she is in bed or not.85

Girls should dress 'sensibly, nicely, and comfortably' when near African men, being sure not to wear clothing that would draw attention to their bodies. Boys should 'remember that they have a higher standard of civilisation to uphold' and should speak 'sensibly' to Africans.86

This warning against male African sexuality was linked, too, to concerns about the position of white children and youth in a country with a largely black population. The modernisation of childhood - discussed above - occurred differently in colonies. In South Africa, middle-class white and, to some extent, black middle-class childhoods lengthened from the late 1860s onwards. Discourses about 'girlhood' and 'boyhood' circulated within local publications, and DRC ministers, in particular, produced a slew of childrearing guides for middle-class parents anxious to raise their children to become sober Christians.87 But, as Ann Laura Stoler suggests, children in colonial settings became 'the sign and embodiment of what needed fixing in ... colonial society'.88 Multiracial children were evidence of relationships, usually illicit, between Europeans and servile indigenous populations.89 Living in warm climates was believed to stimulate sexual development earlier, and settler children were seen as peculiarly vulnerable to exploitation by sexualised others, usually domestic servants.90 The presence of the offspring of interracial sex alongside white children gave 'force to the urgency for a more clearly defined bourgeois order based on white endogamy, attentive parenting, Dutch-language training, and surveillance of servants that might shore it up.'91 Although Europeans in India and some southeast Asian colonies sent their children 'home' for their education,92 in South Africa whites followed a similar pattern to other settler colonies in that their children tended to go to local schools and - after 1873 - universities, rather than being sent abroad. Here, from the 1870s onwards, DRC ministers and a growing number of child welfare organisations were preoccupied with bringing impoverished white children into this modernisation.93

'Facts about Ourselves' is shot through with eugenicist claims. Part of the appeal of eugenics to South African - and other - public health specialists and social reformers was its close association with modernity, and with a modernising project. By arguing that morally, psychologically and physically stronger citizens could be bred and raised through a range of interventions, and by designating who should (and should not) produce children, eugenics could assist in ensuring the future prosperity of the nation. This is not to claim, though, that the pamphlet was part of a broader eugenicist project. Saul Dubow has shown convincingly that eugenics had 'limited utility' in South Africa.94 Although eugenic discourses circulated within the Union, and powerful individuals were committed eugenicists, eugenics had narrow institutional purchase. Many deeply religious Afrikaner nationalist politicians were suspicious of the link between eugenics and Darwinism; eugenics competed with several other, popular race theories in the Union; and the position of poor whites complicated eugenics' white supremacist claims.95 However, acknowledging the presence of eugenic thought in 'Facts about Ourselves' helps to draw attention, firstly, to its interest in the future and, secondly, to its definition of what constituted appropriate sexual behaviour.

West remarks to his young readers, '"Progress" should ever be our watchword.'96'Facts about Ourselves' presents one solution to the poor white problem by imagining a bright, orderly and modern future for the Union, where middle-class authority goes absolutely unquestioned. The manual's orientation to the future is particularly evident in its illustrations. Importantly, it links this future to a strongly South African landscape. Its opening illustration of a young boy and girl walking steadily towards a sunrise is evocative of the landscapes painted by the popular artist J.H. Pierneef (1886-1957). Captioned 'toward the light', it echoes West's interest in mobilising his readers in the interests of the Union's future prosperity and stability.

In the depiction of West's ladder of life, the top illustration is of white, tennis-playing girls in a stylised, apparently urban landscape. This orderly and peaceful vision of the Union, either present or future, contrasted sharply with the everyday lives of most residents of Johannesburg, whose Department of Public Health was one of the publishers of the pamphlet. City authorities were preoccupied with the apparently deleterious social, moral, and public health implications of Johannesburg's mushrooming slums during the 1920s and 1930s. Particularly in the inner city, limited availability of formal housing close to the city centre meant that thousands of newly arrived migrants - largely African, but also white - crowded into slum yards, which were cleared only during the middle decades of the century.97 'Facts about Ourselves' imagines a future free not only of slums but also of the social and, more particularly, sexual threats embodied by those slums, including black peril, and miscegenation too. Unsupervised poor white women in the cities were also considered a threat to the moral order.98 Part of the purpose of 'Facts about Ourselves' is to define what constitutes decent behaviour for white, middle-class children and adults. When they grow up, these young readers should, West argues, marry and produce children within the bounds of monogamous, heterosexual marriage. Appropriate future husbands and wives (sexual partners, in other words) are to be drawn from the readers' own class. This is partly the solution of the poor white problem: ensuring that middle-class whites marry and produce children, pushing back the demographic threat of an apparently ever-increasing population of poor whites. In its emphasis on progress and furthering the health of the race, 'Facts about Ourselves' urges its readers to consider their choices and behaviour to be absolutely integral to the attainment of a stable and prosperous future.

In common with the majority of early-twentieth-century sex education manuals for youth, 'Facts about Ourselves' defines sexual intercourse as penetrative sex between a heterosexual, married couple, and only for the purpose of producing children. Its condemnation of masturbation (and by elision, of all other kinds of sexual behaviour) was, as mentioned above, largely in response to heavily raced concerns about encouraging adolescent self-control, but it was also produced by the need to encourage readers to 'help [their] race to progress'.99 While interracial sex would put the Union's future seriously in jeopardy, the manual's argument is that other forms of sex - sex which did not necessarily lead to pregnancy - would destabilise it too. This narrowing definition of what should constitute sex occurred beyond the sex education manuals for white youth. Catherine Burns suggests that as a result of the influence of Christianity and the waning influence of initiation rites, mid-century urban African youth also began to abandon thigh sex and other behaviours in favour of penetrative sex.100 In the case of sex education manuals, through the mobilisation of expert knowledge, references to God, and warnings against predatory African men, sexual intercourse was recast as an act whose purpose was strongly linked to the maintenance of order and stability in the Union. Similarly, desire - acknowledged as crucial to causing adults to be sexually attracted to one another - was put wholly in the service of the 'race' and, by implication, the Union.

Sex education for white, middle-class children during the early decades of the twentieth century was partly the product of a modernising South African state. As African youth became the audience for pamphlets designed to provide new forms of sexual socialisation in the absence of forms of initiation which had fallen away during urbanisation and as a result of conversion to Christianity, so young white men and women needed to be drawn into the modernising project. Youth were mobilised in aid of a future, prosperous Union firmly under white rule. This was done through the careful management of knowledge. 'Facts about Ourselves' provides white youth with a little information about sexual reproduction - not enough to 'thrill' readers into sexual experimentation, but enough to ensure they would take seriously the implications of sexual relationships - and considerably more about managing their relationships with Africans and, implicitly, their poor white peers. A key strategy in this manual was the encouragement of wilful ignorance. Aware that the pamphlet competed with other demotic forms of knowledge about sex and sexuality, West could only urge and shame readers into turning their thoughts away from sex as well as from talk about sex. Importantly, this knowledge was positioned within a wider scientific discourse about evolution, as well as appeals to readers' patriotism and concern for the future of South Africa, not to mention their piety. West produced a powerful and authoritative narrative by linking this sexual knowledge to science, the nation, and God.

1 Earlier versions of this article were presented at the History of Sexuality Seminar at the Institute of Historical Research at the University of London, the Department of English Seminar at Stellenbosch University, the Wits Interdisciplinary Seminar in the Humanities at the University of the Witwatersrand, and the Northeastern Workshop on Southern Africa in Burlington, Vermont. In particular, I would like to thank John Tosh, Lesley Hall, Megan Jones, Daniel Roux, Catherine Burns, Joshua Walker, Nafisa Essop Sheik, Keith Breckenridge, Christopher J. Lee, Dan Magaziner, Denni Duff, Cynthia Kros and the anonymous reviewers.

2 Wits Historical Papers (WHP), South African Institute of Race Relations Collection (SAIRR), AD 843 RJ/NA 18.4, A.J. Milne, 'Foreword' in R.P.H. West, 'Facts about Ourselves for Growing Boys and Girls' (Johannesburg: Public Health Department of the City of Johannesburg and the South African Red Cross Society (Transvaal), 1934), 3.

3 Ibid, Milne, 'Foreword', 3.

4 Ibid.

5 Karen Jochelson, The Colour of Disease: Syphilis and Racism in South Africa, 1880-1940 (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2001), 87-92, 148-50; [ Links ] Alan Jeeves, 'The State, the Cinema, and Health Propaganda for Africans in Pre-Apartheid South Africa, 1932-1948', South African Historical Journal, 48, 1, 2003, 109-29. [ Links ]

6 Most of this scholarship will be cited in this article, but the work of Alan Jeeves, Susanne Klausen, Clive Glaser, Peter Delius, Marc Epprecht, Natasha Erlank, Deborah Gaitskell, Rebecca Hodes, Catherine Burns, Mark Hunter and Benedict Carton is particularly useful. For a general overview of historical, ethnographic and anthropological work, see Natasha Erlank, 'Sexuality in South Africa and South African Academic Writing', South African Review of Sociology, 39, 1, 2008, 156-74. [ Links ]

7 A notable exception in this regard is the work been done in Rhodes University's Critical Studies in Sexualities and Reproductions Research Programme. See Catriona Macleod, 'Danger and Disease in Sex Education: The Saturation of "Adolescence" with Colonialist Assumptions', Journal of Health Management, 11, 2, 2009, 375-89. [ Links ]

8 Most scholarship on histories of sex education has emerged since the mid-1990s. Two major edited collections provide an overview on work currently being done in the United Kingdom, the United States, Europe and Australia: Lutz D.H. Sauerteig and Roger Davidson (eds), Shaping Sexual Knowledge: A Cultural History of Sex Education in Twentieth Century Europe (London and New York: Routledge, 2009), [ Links ] and Claudia Nelson and Michelle H. Martin (eds), Sexual Pedagogies: Sex Education in Britain, Australia, and America, 1879-2000 (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2004). [ Links ] On the UK, see Roy Porter and Lesley Hall, The Facts of Life: The Creation of Sexual Knowledge in Britain, 1650-1950 (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1995); [ Links ] James Hampshire and Jane Lewis, '"The Ravages of Permissiveness": Sex Education and the Permissive Society', Twentieth Century British History, 15, 3, 2004, 290-312; [ Links ] and Jane Pilcher, 'School Sex Education: Policy and Practice in England 1870 to 2000', Sex Education, 5, 2, May 2005, 153-70. [ Links ] On the US, see Jeffrey P. Moran, Teaching Sex: The Shaping of Adolescence in the 20th Century (Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press, 2000); [ Links ] Susan K. Freeman, Sex Goes to School: Girls and Sex Education Before the 1960s (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2008); [ Links ] Carolyn Cocca (ed), Adolescent Sexuality: A Historical Handbook and Guide (Westport: Praeger, 2006); [ Links ] Janice M. Irvine, Talk about Sex: The Battles over Sex Education in the United States (Berkeley CA: University of California Press, 2004); [ Links ] and Julian B. Carter, 'Birds, Bees, and Venereal Disease: Towards an Intellectual History of Sex Education', Journal of the History of Sexuality, 10, 2, 2001, 213-49. [ Links ] On France, Mary Lynn Stewart, '"Science Is Always Chaste": Sex Education and Sexual Initiation in France, 1880s-1930s', Journal of Contemporary History, 32, 3. July 1997, 381-94; [ Links ] and on Australia, Sally Gibson, 'The Language of the Right: Sex Education Debates in South Australia', Sex Education, 7, 3, August 2007, 239-50. [ Links ]

9 The scholarship is growing, though. See Harriet Evans, Women and Sexuality in China: Dominant Discourses of Female Sexuality and Gender since 1949 (China: Polity, [1997] 2005), 56-81; Corrie Decker, 'Biology, Islam, and the Science of Sex Education in Colonial Zanzibar', Past and Present, 222, February 2014, 215-47; and Jonathan Zimmerman, Too Hot to Handle: A Global History of Sex Education (Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press, 2015). [ Links ]

10 See Victoria Harris, 'Sex on the Margins: New Directions in the Historiography of Sexuality and Gender', Historical Journal, 53, 2010, 1085-1104. [ Links ]

11 Macleod, 'Danger and Disease in Sex Education,' 376.

12 Hazel Patricia Dunlevey, 'Janie Antonia Malherbe/Mrs E.G. Malherbe, 1897-1945' (Unpublished BA Honours thesis, University of Natal, 2003), 27. On E.G. Malherbe, see Brahm David Fleisch, 'Social Scientists as Policy Makers: E.G. Malherbe and the National Bureau for Educational and Social Research, 1929-1943', Journal of Southern African Studies, 21, 3, September 1995, 349-72, [ Links ] and Saul Dubow, 'Scientism, Social Research and the Limits of "South Africanism": The Case of Ernst Gideon Malherbe', South African Historical Journal, 44, 1, 2001, 99-142. [ Links ]

13 Dunlevey, 'Janie Antonia Malherbe/Mrs E.G. Malherbe, 1897-1945', 16-18.

14 'Suffrage Literature', Woman's Outlook, 1, 11, August 1913, 10.

15 Stewart, '"Science Is Always Chaste,'" 381. See also John S. Haller, 'From Maidenhood to Menopause: Sex Education for Women in Victorian America', Journal of Popular Culture, 6, 1, Summer 1972, 49-69. [ Links ]

16 Porter and Hall, Facts of Life, 202-15.

17 WHP, SAIRR, AD 843 RJ/NA 18.4, Milne, 'Foreword', 3.

18 On the provision of sex education to white adult men and women in response to anxieties about a perceived increase in rates of syphilis after the First World War, see Alan Jeeves, 'Public Health in the Era of South Africa's Syphilis Epidemic of the 1930s and 1940s', South African Historical Journal, 45, 1, 2001, 79-102; [ Links ] and Karen Jochelson, The Colour of Disease: Syphilis and Racism in South Africa, 1880-1940 (Basingstoke: Palgrave, 2001), 10-13, 79-86. [ Links ] However, since at least the 1880s, the treatment of syphilis in South Africa had been closely intertwined with the region's race politics - see Jochelson, Colour of Disease, 46-51, and Elizabeth van Heyningen, 'The Social Evil in the Cape Colony 1868-1902: Prostitution and the Contagious Diseases Acts' Journal of Southern African Studies, 10, 2, April 1984, 170-97. [ Links ]

19 'Sex Education: Fighting Ignorance and Disease', Child Welfare, December 1924, 8.

20 In 1927 the Red Cross absorbed the Social Hygiene Council - itself the renamed National Committee for Combating Venereal Disease, founded in 1917 - partly to take over the activities of committees campaigning against the Contagious Diseases Act in the Cape. Jochelson, Colour of Disease, 78, 85-6.

21 E.G. Malherbe chaired the South African branch of the New Education Fellowship and was involved in arranging the organisation's large and important conference in Cape Town in 1934. WHP, SAIRR, AD 843 RJ/NA 18.4, National Committee for Health Education (South African Red Cross Society), Annual Report, 1940, 3; Presidential Address, Red Cross Conference, 23 May 1938. On the New Education Fellowship, see Kevin J. Brehony, 'A New Education for a New Era: The Contribution of the Conferences of the New Education Fellowship to the Disciplinary Field of Education 1921-1938', Paedagogica Historica: International Journal of the History of Education, 40, 5-6, 2004, 733-55. [ Links ]

22 See H.G. Cocks, 'Saucy Stories: Pornography, Sexology and the Marketing of Sexual Knowledge in Britain, c. 1918-70', Social History, 29, 4, November 2004, 465-84. [ Links ]

23 So far, my research has not revealed examples of sex education manuals being confiscated by the authorities on the grounds of obscenity before 1948. On the origins of the 1931 Entertainments (Censorship) Act in South Africa, see Peter D. McDonald, The Literature Police: Apartheid Censorship and its Cultural Consequences (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009), 21-2.

24 WHP, SAIRR, AD 843 RJ/NA 18.4, West, 'Facts about Ourselves', 4.

25 Carter, 'Birds, Bees, and Venereal Disease', 216-17.

26 R. Danielle Egan and Gail L. Hawkes, 'Imperiled and Perilous: Exploring the History of Childhood Sexuality, Journal of Historical Sociology, 21, 4, December 2008, 356. [ Links ]

27 Moran, Teaching Sex, 95.

28 On the invention of girlhood and boyhood, see Jane Hunter, How Young Ladies Became Girls: The Victorian Origins of American Girlhood (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004) and Kenneth B. [ Links ] Kidd, Making American Boys: Boyology and the Feral Tale (Minneapolis MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2004). [ Links ]

29 Leonore Davidoff, Megan Doolittle, Janet Fink and Katherine Holden, The Family Story: Blood, Contract and Intimacy 1830-1960 (London and New York: Longman, 1999), 168-9. [ Links ]

30 Steven Mintz, Huckks Raft: A History of American Childhood (Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press, 2004), 251-3. [ Links ]

31 Adam Kuper, Incest and Influence: The Private Lives of Bourgeois England (Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press, 2009), 13-14. [ Links ]

32 There is a vast literature on the nineteenth-century masturbation panic. See Thomas Laqueur, Solitary Sex: A Cultural History of Masturbation (New York: Zone, 2003); [ Links ] Lesley A. Hall, 'Forbidden by God, Despised by Men: Masturbation, Medical Warnings, Moral Panic, and Manhood in Great Britain, 1850-1950', Journal of the History of Sexuality, 2, 3, [ Links ] Special Issue, Part 2: The State, Society, and the Regulation of Sexuality in Modern Europe, January 1992, 365-87; Ellen Bayuk Rosenman, 'Body Doubles: The Spermatorrhea Panic', Journal of the History of Sexuality, 12, 3, July 2003), 365-99. [ Links ]

33 For example, G. Stanley Hall, 'Education in Sex-Hygiene', Eugenics Review, 1910, 242-53.

34 Michel Foucault, Abnormal: Lectures at the Collège de France 1974-1975, Graham Burchell (trans), Valerio Marchetti and Antonella Salomoni (eds) (London: Verso, 2003), 245. See also Foucault, History of Sexuality, vol I: An Introduction, Robert Hurley (trans) (New York: Pantheon, 1978), 121-2. [ Links ]

35 Ibid, 104.

36 Moran, Teaching Sex, 17, 19.

37 On the complex position of childhood sexuality in modernity, see Danielle Egan and Gail Hawkes, Theorising the Sexual Child in Modernity (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010). [ Links ] See also Deborah Gorham, 'The "Maiden Tribute of Modern Babylon" Re-Examined: Child Prostitution and the Idea of Childhood in Late-Victorian England', Victorian Studies, 21, 3, Spring 1978, 353-79. [ Links ]

38 Moran, Teaching Sex, 12.

39 On nineteenth-century self-help manuals see Jeffrey Richards, 'Spreading the Gospel of Self-Help: G.A. Henty and Samuel Smiles', Journal of Popular Culture, 16, 2, Fall 1982, 52-65.

40 Foucault, History of Sexuality, vol I, 103.

41 Porter and Hall, Facts of Life, 8.

42 Moran, Teaching Sex, 22.

43 Lutz D.H. Sauerteig and Roger Davidson, 'Shaping the Sexual Knowledge of the Young' in Sauerteig and Davidson (eds), Shaping Sexual Knowledge, 6-10.

44 Carter, 'Birds, Bees, and Venereal Disease,' 233.

45 Ibid, 230.

46 Christina Simmons, Making Marriage Modern: Women's Sexuality from the Progressive Era to World War II (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009), 105-37. [ Links ]

47 WHP, SAIRR, AD 843 RJ/NA 18.4, West, 'Facts about Ourselves', 16.

48 Ibid, 20-1.

49 Lesley A. Hall, '"It Was Affecting the Medical Profession": The History of Masturbatory Insanity Revisited', Pedagogica Historica, 39, 6, December 2003, 685-99; [ Links ] Sam Pryke, 'The Control of Sexuality in the Early British Boy Scouts Movement', Sex Education, 5, 1, February 2005, 15-28. [ Links ]

50 WHP, SAIRR, AD 843 RJ/NA 18.4, West, 'Facts about Ourselves', 16.

51 Ibid, 26.

52 Ibid, 25.

53 Peter Delius and Clive Glaser, 'Sexual Socialisation in South Africa: A Historical Perspective', African Studies, 61, 1, 2002, 32-3; [ Links ] Catherine Burns, 'Sex Lessons from the Past?' Agenda, 29, Women and the Environment, 1996, 80-1, 87-9. See also Philip Mayer and Iona Mayer, 'Socialisation by Peers: The Youth Organisation of the Red Xhosa' in Philip Mayer (ed), Socialisation: The Approach from Social Anthropology (London: Tavistock, 1970), 175-8.

54 Delius and Glaser, 'Sexual Socialisation in South Africa, 30-1; T. Dunbar Moodie, Vivienne Ndatshe and British Sibuyi, 'Migrancy and Male Sexuality on the South African Gold Mines', Journal of Southern African Studies, 14, 2, [ Links ] Special Issue on Culture and Consciousness in Southern Africa, January 1988, 231.

55 Erlank, 'Sexuality in South Africa', 166-7; Natasha Erlank, '"Plain Clean Facts" and Initiation Schools: Christianity, Africans and "Sex Education" in South Africa, c. 1910-1940', Agenda, 62, African Feminisms, 2, 1, Sexuality in Africa, 2004, 79.

56 Peter Delius and Clive Glaser, 'Sex, Disease, and Stigma in South Africa: Historical Perspectives', African Journal of AIDS Research, 4, 1, 2005, 30-2; Clive Glaser, 'Managing the Sexuality of Urban Youth: Johannesburg, 1920s-1960s', International Journal of African Historical Studies, 38, 2, 2005, 313; Burns, 'Sex Lessons from the Past?' 89. See also Monica Wilson, 'The Wedding Cakes: A Study of Ritual Change' in Jean Sybil la Fontaine (ed), The Interpretation of Ritual: Essays in Honour of A.I. Richards (London: Tavistock, 1972), 187-202.

57 Deborah Gaitskell, '"Wailing for Purity": Prayer Unions, African Mothers, and Adolescent Daughters 1912-1940' in Shula Marks and Richard Rathbone (eds), Industrialisation and Social Change in South Africa (Harlow: Longman, 1982), 341-6; [ Links ] Deborah Gaitskell, '"Christian Compounds for Girls": Church Hostels for African Women in Johannesburg, 1907-1970', Journal of Southern African Studies, Special Issue on Urban Social History, 6, 1, October 1979, 44-69.

58 Erlank, '"Plain Clean Facts,"' 82.

59 So far, little has been written about sex education specifically for African-American children and youth in the United States. On the development of separate social hygiene programmes for black adults and youth in the south, see Moran, Teaching Sex, 114-15. On sex education and anxieties about contact between white girls and black men, see Irvine, Talk about Sex, 120-1.

60 Judith Tayler, '"Our Poor": The Politicisation of the Poor White problem, 1932-1942, Kleio, 24, 1, 1992, 45-6. [ Links ]

61 Susanne Klausen, '"For the Sake of the Race": Eugenic Discourses of Feeblemindedness and Motherhood in the South African Medical Record, 1903-1926', Journal of Southern African Studies, 23, 1, March 1997, 28. [ Links ]

62 See Anna Davin, 'Imperialism and Motherhood', History Workshop, 5, 1978, 9-65.

63 Linda Bryder, A Voice for Mothers: The Plunket Society and Infant Welfare, 1907-2000 (Auckland: Auckland University Press, 2003), 1. [ Links ]

64 Nancy Rose Hunt, '"Le Bebe en Brousse": European Women, African Birth Spacing and Colonial Intervention in Breast Feeding in the Belgian Congo, International Journal of African Historical Studies, 21, 3, 1988, 401-32. [ Links ]

65 See, for example, Hermann Giliomee, '"Wretched Folk, Ready for Any Mischief": The South African State's Battle to Incorporate Poor Whites and Militant Workers, 1890-1939', Historia, 47, 2, November 2002, 601-53.

66 Glaser, 'Managing the Sexuality of Urban Youth', 302; Van Heyningen, 'Social Evil in the Cape Colony', 170-97; Zackie Achmat, Apostles of "Civilised Vice," "Immoral Practices," and "Unnatural Vice" in South African Prisons and Compounds, 1890-1920', Social Dynamics, 19, 2, 1993, 92-110; Charles van Onselen, New Babylon, New Nineveh: Everyday Life on the Witwatersrand 1886-1914 (Johannesburg: Jonathan Ball, [1982] 2001), 109-64, 263-6.

67 Glaser, 'Managing the Sexuality of Urban Youth', 303.

68 Susanne Klausen, 'Women's Resistance to Eugenic Birth Control in Johannesburg, 1930-1939', South African Historical Journal, 50, 1, 2004, 152-69; [ Links ] Susanne Klausen, '"Poor Whiteism", White Maternal Mortality, and the Promotion of Public Health in South Africa: The Department of Public Health's Endorsement of Contraceptive Services, 1930-1938', South African Historical Journal, 45, 1, 2001, 53-78. [ Links ]

69 Klausen, '"Poor Whiteism,"' 59.

70 'Durban WEL, Supplement to Woman's Outlook, June 1915, 12.

71 Dunlevey, 'Janie Antonia Malherbe/Mrs E.G. Malherbe, 1897-1945', 27-8; Marijke du Toit, '"Dangerous Motherhood": Maternity Care and the Gendered Construction of Afrikaner Identity, 1904-1939' in Valerie A. Fildes, Lara Marks and Hilary Marland (eds), Women and Children First: International Maternal and Infant Welfare, 1870-1945 (London and New York: Routledge, 1992), 210-12, 215. [ Links ]

72 'Cape Town', Child Welfare, December 1925, 6-7.

73 Interview with Hester Honey, Stellenbosch, 28 August 2014. See also Elsabe Brink, 'The "Volksmoeder": A Figurine as Figurehead' in Siegfried Huigen and Albert Grundlingh (eds), Reshaping Remembrance: Critical Essays on Afrikaans Places of Memory (Amsterdam: Rozenberg, 2011), 12. [ Links ]

74 Neil Roos, 'Work Colonies and South African Historiography', Social History, 36, 1, February 2011, 63.

75 WHP, South African National Council for Child Welfare (SANCCW) Collection, AD 1960, SANCCW Council Meeting 1937, Motion Paper, 3.

76 Crista DeLuzio, Female Adolescence in American Scientific Thought, 1830-1930 (Baltimore MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2007), 95. On recapitulation doctrine, see Stephen Jay Gould, Ontogeny and Phylogeny (Cambridge MA: Belknap, 1977).

77 Carter, 'Birds, Bees, and Venereal Disease', 235.

78 WHP, SAIRR, AD 843 RJ/NA 18.4, West, 'Facts about Ourselves', 5.

79 Ibid, 6-7.

80 Ibid, 10.

81 On Hall's relative neglect of adolescent girls, see Nancy Lesko, 'Making Adolescence at the Turn of the Century: Discourse and the Exclusion of Girls', Current Issues in Comparative Education, 2, 2, 2000, 182-91; DeLuzio, Female Adolescence in American Scientific Thought, 90-132.

82 Tammy M. Proctor, '"A Separate Path": Scouting and Guiding in Interwar South Africa', Comparative Studies in Society and History, 42, 3, July 2000, 605-31; [ Links ] Glaser, 'Managing the Sexuality of Urban Youth', 314-15; Deborah Gaitskell, '"Upward All and Play the Game": The Girl Wayfarers' Association in the Transvaal, 1925-1975' in Peter Kallaway (ed), Apartheid and Education: The Education of Black South Africans (Johannesburg: Ravan, 1984), 246-353. [ Links ]

83 WHP, SAIRR, AD 843 RJ/NA 18.4, West, 'Facts about Ourselves', 26.

84 On the black peril in southern Africa, see Jock McCulloch, Black Peril, White Virtue: Sexual Crime in Southern Rhodesia, 1902-1935 (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2000); [ Links ] Henriette J. Lubbe, 'The Myth of "Black Peril": Die Burger and the 1929 Election, South African Historical Journal, 37, 1, 1997, 107-32; [ Links ] Norman Etherington, 'Natal's Black Rape Scare of the 1870s', Journal of Southern African Studies, 15, 1, October 1988, 36-53; [ Links ] Timothy Keegan, 'Gender, Degeneration and Sexual Danger: Imagining Race and Class in South Africa, ca. 1912', Journal of Southern African Studies, 27, 3, 2001, 459-77; [ Links ] Gareth Cornwell, 'George Webb Hardy's The Black Peril and the Social Meaning of "Black Peril" in Early Twentieth-Century South Africa', Journal of Southern African Studies, 22, 3, September 1996, 441-53 On anxieties about sexual assaults on white women and children, [ Links ] see David Anderson, 'Sexual Threat and Settler Society: "Black Perils" in Kenya, c. 1907-1930', Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History, 38, 1, 2010, 47-74.

85 Ibid, 26-7.

86 Ibid, 27.

87 S.E. Duff, '"Onschuldig Vermaak": The Dutch Reformed Church and Children's Leisure Time in the Nineteenth-Century Cape Colony', South African Historical Journal, 63, 4, 2011, 495-513. [ Links ]

88 Ann Laura Stoler, Race and the Education of Desire: Foucaults History of Sexuality and the Colonial Order of Things (Durham NC and London: Duke University Press, 1995), 46. [ Links ]

89 On multiracial children and empire see Owen White, Children of the French Empire: Miscegenation and Colonial Society in French West Africa, 1895-1960 (Oxford: Clarendon, 1999); [ Links ] David M. Pomfret, 'Raising Eurasia: Race, Class, and Age in British Colonies', Comparative Studies in Society and History, 51, 2, 2009, 314-43; [ Links ] and Christopher J Lee, 'Children in the Archives: Epistolary Evidence, Youth Agency, and the Social Meanings of "Coming of Age" in Interwar Nyasaland', Journal of Family History, 35, 1, January 2010, 25-47. [ Links ]

90 Stoler, Race and the Education of Desire, 178-83.

91 Ibid, 46.

92 Elizabeth Buettner, Empire Families: Britons and Late Imperial India (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004), 72-109; [ Links ] Frances Gouda, Dutch Culture Overseas: Colonial Practice in the Netherlands Indies 1900-1942 (Singapore: Equinox, 2008), 75-117; [ Links ] Ann Laura Stoler, Carnal Knowledge and Imperial Power: Race and the Intimate in Colonial Rule (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002), 112-39. [ Links ]

93 On poor whiteism in South Africa see Robert Morrell (ed), White But Poor: Essays on the History of the Poor Whites in Southern Africa, 1880-1940 (Pretoria: Unisa Press, 1992). Anxieties about white poverty within the British Empire were not limited to South Africa. See, for instance, David Arnold, 'European Orphans and Vagrants in India in the Nineteenth Century', Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History, 7, 2, 1979, 104-27. [ Links ]

94 Saul Dubow, 'Paradoxes in the Place of Race' in Alison Bashford and Philippa (eds), The Oxford Handbook of the History of Eugenics (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010), 286. [ Links ]

95 Ibid, 274-86. See also Klausen, '"For the Sake of the Race"'

96 WHP, SAIRR, AD 843 RJ/NA 18.4, West, 'Facts about Ourselves', 9.

97 Susan Parnell, 'Race, Power and Urban Control: Johannesburg's Inner City Slum-Yards, 1910-1923, Journal of Southern African Studies, 29, 3, 2003, 615-37.

98 Louise Vincent, 'Bread and Honour: White Working Class Women and Afrikaner Nationalism in the 1930s', Journal of Southern African Studies, 26, 1, 2000, 62; Elsabe Brink, 'Man-Made Women: Gender, Class and the Ideology of the Volksmoeder in Cherryl Walker (ed), Women and Gender in Southern Africa to 1945 (Cape Town: David Philip, 1990), 282-3; Keegan, 'Gender, Degeneration and Sexual Danger', 461-6, 468-74.

99 WHP, SAIRR, AD 843 RJ/NA 18.4, West, 'Facts about Ourselves', 10.

100 Burns, 'Sex Lessons from the Past?', 89-91.