Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Kronos

versão On-line ISSN 2309-9585

versão impressa ISSN 0259-0190

Kronos vol.41 no.1 Cape Town Nov. 2015

ARTICLES

Socwatsha kaPhaphu, James Stuart, and their conversations on the past, 1897-1922

John Wright

Archive and Public Culture Research Initiative, University of Cape Town

ABSTRACT

From 1897 to 1922, through all the phases of his career as a researcher into the histories and customs of Africans in Zululand and Natal, the colonial official James Stuart made copious notes of his ongoing conversations with Socwatsha kaPhaphu. Renderings of these notes fill 168 printed pages of volume 6 of the James Stuart Archive, published in 2014. The notes not only form a rich source of empirical historical information but also give insights into the contexts in which knowledges of the past were made and circulated in African societies in Zululand and Natal in the first two decades of the twentieth century. In addition, they reveal something of Stuart's own methods as a recorder of oral histories, and the changing conditions in which he worked. This essay examines the scope and, where possible, the sources of Socwatshas knowledge of the past, and why and when Stuart engaged in recording particular aspects of it. In doing so, the essay points up the inescapable intertwinings of accounts of the past as narrated by an African commentator and as recorded in writing by a colonial official. Scholars are now examining in detail the roles played by African knowledge makers in the making and circulating of literary knowledges of the continent in the colonial era; this essay takes a further step in this direction.

Keywords: Alfred Bryant, Colony of Natal, Colony of Zululand, Rolfes Dhlomo, interlocutor, James Stuart Archive, Natal rebellion 1906, oral histories, Socwatsha kaPhaphu, James Stuart, Zulu history

Socwatsha kaPhaphu1 comes to our knowledge today mainly through the publication of volume 6 of the James Stuart Archive in 2014.2 This volume contains renderings of the notes which James Stuart made in the period 1897 to 1922 of conversations with Socwatsha on the histories and customs of Africans in Zululand and Natal. Of the nearly two hundred interlocutors with whom Stuart conversed during this period, Socwatsha was much the most prolific. Stuart's notes of his statements fill 168 printed pages, many more than the 120 pages taken up by the statements of the next most prolific, Ndukwana kaMbengwana.3 The nature of Stuart's recording and writing projects, and the ways in which they changed over time, will emerge in the course of this essay: the salient point here is that Socwatsha was the only one of his interlocutors to whom he turned through all the phases of his career as a researcher into African history and custom.

Stuart's notes of their conversations not only form a rich source of empirical historical information, but also give insights into the contexts in which knowledges of the past were made and circulated in African societies in Zululand and Natal during what was a period of deeply disruptive political and social change. In addition, they provide insights into Stuart's own methods as a recorder of oral histories, and into the changing contexts in which he worked. This essay examines the scope and, where possible, the sources of Socwatsha's knowledge of the past, and why and when Stuart engaged in recording particular aspects of it. Like my previous article on Ndukwana,4the essay shows the inescapable intertwinings of accounts of the past as narrated by an African with specialised knowledge and as recorded in writing by a colonial official.

In the four decades since the publication of volume 1 in 1976, something of an accompanying historiography has built up round the James Stuart Archive. At one level, it consists in the brief reflexive comments published in the Introduction to volume 1 and the Prefaces to subsequent volumes on editorial method, which in some respects has changed over time. At another level, it lies in the reviews of successive volumes that have appeared in academic journals. In the 1990s scholars began to publish longer commentaries on James Stuart's project of recording oral histories, the factors which shaped those histories, Stuart's working methods, and the making of the James Stuart Archive. I drew attention to these in the Preface to volume 5 (2001). More recently, following the 'archival turn' in discourse on the history of South Africa in the eras before colonialism, pioneered largely by Carolyn Hamilton, students of Stuart's work have begun to pay greater attention to researching biographical studies of his interlocutors, and to examining the backstories of the accounts of the past which he recorded from them.5 This development reflects approaches being taken in African studies more widely, where scholars are now examining in detail the roles played by African knowledge workers in the making and circulating of literary knowledges of the continent in the colonial era.6 The present article takes a further step in this direction.

In the Introduction and Prefaces to the six volumes of the James Stuart Archive published so far, the editors have drawn attention to the broad procedures followed in ordering Stuart's notes for publication, and to the nature of the emendations they have made to his original texts in rendering them in printed form. Nothing short of photographic reproduction can hope to capture the physical details of his handwritten notes, with their crossings out, arrowed insertions, and interlinear and marginal insertions, in ink and in pencil; but beyond the minor literating processes they adopted in presenting the notes typographically, the editors have also made interventions that reshape Stuart's notes in much more substantial ways. Most readers of Socwatsha's statements as rendered in the James Stuart Archive will not have access to Stuart's originals in the Killie Campbell Africana Library in Durban unless at some stage they are made accessible in digitised form. Here I highlight the ways in which the editors have reshaped the texts that have been published under Socwatsha's name.

In the first place, for reasons briefly explained in the Preface to volume 4, the editors have omitted the praises that Stuart recorded from many of his interlocutors. In the case of Socwatsha, 23 praises of various lengths have been omitted. (In the Preface to volume 5, I indicated my intention to publish the omitted praises in a seventh volume of the James Stuart Archive; here I can report that my new co-editor Mbongiseni Buthelezi and I began work on the volume early in 2015.) Secondly, the editors have deliberately published in English the words and passages recorded by Stuart in Zulu, rather than attempting the typographically nightmarish task of rendering his notes, which he often wrote in a mixture of English and Zulu, in parallel texts. Stuart recorded most of his conversations with Socwatsha in English, or a mixture of English and Zulu, but from 1918 onwards, when he was gathering stories for inclusion in the series of Zulu school readers that he was then planning, he wrote almost exclusively in Zulu. Readers of Socwatsha's statements in the James Stuart Archive will thus encounter long passages of translation; in total they make up some 30 per cent of the 168 pages of text. These are as much the renderings of the editors as they are of Stuart and of Socwatsha.

Thirdly, in assembling Stuart's notes of Socwatsha's statements and ordering them chronologically, the editors have had to remove them from the contexts in which Stuart originally recorded them. Notes recorded in the original under Socwatsha's name appear in the James Stuart Collection in fifty or more different locations in some forty separate notebooks. As distinct 'passages', they range in length from a single sentence to more than eighty consecutive pages recorded on several consecutive days. All of them are in one way or another interleaved with notes that Stuart made of his conversations with others of his interlocutors. A simple count reveals that over the twenty-five years during which they held conversations on the past, Stuart and Socwatsha spoke together on some sixty different dates, sometimes for several days together, at other times with breaks of several years in between. Throughout, Stuart was busy making notes of his conversations with other people, and picking up points and developing queries which would have fed into his subsequent conversations with Socwatsha. Little of this emerges directly from the 'smoothed-out' printed text that faces the reader in the James Stuart Archive.

In brief, the editors' renderings of Stuart's notes of his conversations with Socwatsha constitute texts which the reader has to engage with at several different levels as sources of historical information. The point perhaps sounds trite, but over the years researchers using the James Stuart Archive have too often simply raided its pages for historical 'facts' without taking account of the range of factors that shaped the nature of the texts they encounter. The present article itself draws primarily on the edited and translated texts of Socwatsha's statements in the James Stuart Archive: its line of discussion needs to be assessed against the background of the comments made above.

Phaphu and Socwatsha: Biographical Background

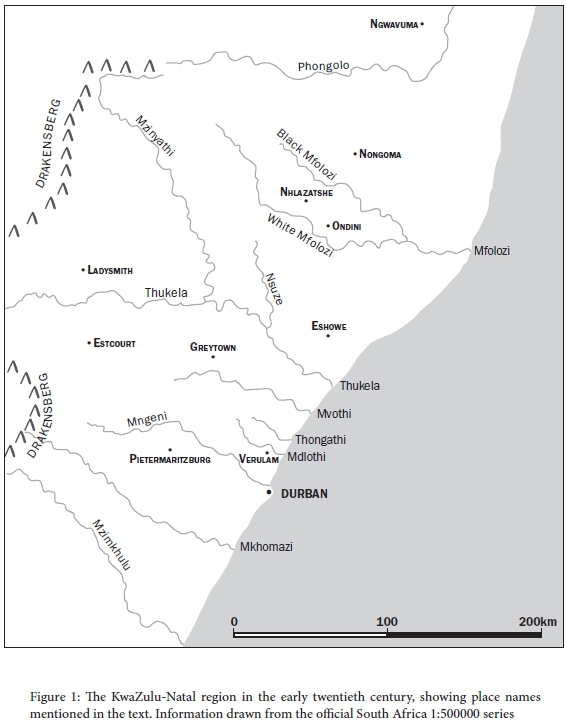

Almost all that we know about Socwatsha's life and family history comes from what he told Stuart, and more specifically from what Stuart saw fit to write down. Most of this information was recorded in passing, during conversations on other subjects, though at some points Stuart did question Socwatsha briefly about his own story. The discussion here begins with what we are told about his father, Phaphu kaSikhayana. Phaphu was of the abakwaNgongoma clan, one of a number of closely related clans collectively known as the abakwaNgcobo.7 He was related to the Ngongoma chiefly line through his father Sikhayana, who was a son in the left-hand house of the chief Mavela.8According to Stuart's reckoning, Phaphu had been born in about 1785-7.9He grew up during the reign of Bhofungana (Bhovungana), who had succeeded Mavela and who, like the chiefs of other Ngcobo clans, recognised the ritual authority of the senior Nyuswa clan but otherwise ruled autonomously.10 At that time, as for an unknown period in the past, the Ngongoma chiefs ruled over territory on the lower Nsuze River near its confluence with the Thukela.11

In the late 1810s the chiefdoms of the middle Thukela valley became caught up in the political and social upheavals generated by conflict between the Ndwandwe kingdom under Zwide kaLanga and the expanding Zulu chiefdom under Shaka kaSenzangakhona.12 Several of the Ngcobo chiefs were put to death by Shaka, among them Mafongosi, who had succeeded his father Bhofungana as ruler of the Ngongoma chiefdom. Most of their people ended up placing themselves under the authority of a neighbouring chief, Zihlandlo kaGcwabe of the abakwaMkhize or abaseMbo, whom Shaka allowed to rule with a degree of autonomy in the southwestern marchlands of his growing kingdom.13 Among them was Phaphu, who was stationed at uBhadane (oBhadaneni), an establishment consisting of men of all ages that was set up by Shaka near the Thukela a few kilometres downstream from the Ngongoma region.14 Some years later Phaphu was allowed by Shaka to put on the headring and marry; his eldest son was, by Stuart's calculation, born in 1824 or 1825, when Phaphu would have been close to forty years of age.15

After the assassination of Shaka in 1828, his successor Dingane kept a close watch on the former king's political favourites for signs of wavering loyalty. In about 1832 or 1833 he found an excuse for killing Zihlandlo of the Mkhize and driving out his subjects.16 By Socwatsha's account to Stuart, Phaphu was involved in the fighting against the force sent by Dingane,17 but then seems to have joined the flight of Zihlandlo's people southwards across the Thukela. Most of them settled under members of the Mkhize chiefly house beyond the reach of direct Zulu rule in the region between the middle Mngeni and the middle Mkhomazi Rivers.18 Presumably Phaphu was among them. He later left to settle closer to the coastlands in the oZwathini area at the sources of the Thongathi and Mdlothi Rivers.

Like other peoples in the mid-Thukela valley in the time of Shaka and Dingane, the Ngcobo had come to be regarded in the eyes of their Zulu overlords as belonging to the despised category of amalala.19 Recent research has shown that the abakwa-Zulu applied this designation, in its sense of something like 'menials', collectively to the peoples of their kingdom's southern peripheries. They were largely kept out of public affairs in the core of the kingdom, and were forced to pay heavy tribute in cattle and labour.20 The desire to escape Zulu oppression may well have been a factor in the decision made by Phaphu and other Ngongoma to seek a new life in the region south of the Thukela.

In 1837-8, a few years after the flight of Zihlandlo's people, several thousand Boer trekkers and their retainers from the Cape pushed across the Drakensberg and sought to establish themselves in the territory south of the Thukela River claimed by Dingane. In the war that followed, Phaphu was one of the local inhabitants who sided with the Boers and took part in fighting against Dingane's forces.21 He joined a cattle raiding expedition into the Zulu kingdom mounted by British traders who were operating from Port Natal, and managed to escape when the party was heavily defeated by a Zulu army near the mouth of the Thukela in April 1838. At some point he entered the service of the Boers as a herdsman and hunter, and in August 1838 helped to defend a Boer encampment near what later became the town of Estcourt against a major Zulu attack.

Phaphu lived through the period that saw the defeat of the Zulu by the Boers in 1838, the overthrow of Dingane and the accession of Mpande in 1840, the annexation of the Thukela-Mzimkhulu territories as the British colony of Natal in 1843, and the setting up of a functioning colonial administration in 1845-6. If he had not already done so, he established himself with other Ngongoma people, some of whom had broken away from Mpande,22 in the oZwathini area. Here, in about 1852, when Phaphu was in his late sixties, his youngest son Socwatsha was born.23 Who his mother was is not recorded.

We know virtually nothing of the first thirty years of Socwatsha's life. He later told Stuart that he had grown up and married at oZwathini,24 a region which from the late 1840s fell into the Inanda Location, one of half a dozen African reserves set up at that time by the colonial government. He also mentioned that in 1873 he was in Durban;25 this may indicate that, like many young African men in the colony, he was working as a migrant labourer. It was not until the aftermath of the British invasion and overthrow of the Zulu kingdom in 1879 that he emerges more clearly onto the stage of recorded history. He detailed the circumstances in a conversation recorded by Stuart many years later.26 It appears that in the early 1880s Socwatsha's elder brother Godloza, who also lived at oZwathini, was advised by the induna at the Verulam magistracy, one Ncaphayi kaMkhobosi Ndlovu ('a very able induna', according to Stuart) to go and become a policeman for the British in Zululand so as to acquire land to live on. 'Do you see that your umuzi [homestead] will die out if you stay there at oZwatini?' Ncaphayi said. One suspects that he was referring to the potential effects of the land shortages which by this time were being experienced by many homesteads in the reserves.27 Godloza went and joined the service of Melmoth Osborn, the recently established British resident in Zululand, who had his headquarters at Nhlazatshe (northwest of modern-day Ulundi). From there, Godloza sent for Socwatsha to come and join him, which he did, arriving in Zululand in January 1883, just at the time of the restoration of the former Zulu king Cetshwayo to part of his old kingdom. He became a policeman and messenger under Osborn who, from the beginning of 1883, was resident commissioner in the Zululand Reserve, based at Eshowe.28

At some stage Socwatsha and his brother were able to acquire land under official auspices in the old Ngongoma country near the Nsuze River and to re-establish their homesteads, first, it seems near the graves of their ancestral chiefs, and then lower down the river near its confluence with the Thukela.29 They came under the authority of Osborn's head induna, Yamela kaPhangandawo, who, with Osborn's backing, was building up his own chieftaincy in the Eshowe area.30 On the latter's death they were placed under the authority of Ndube kaQhethuka Magwaza, an officially recognised chief in the region.31

Like others of Osborn's staff, Socwatsha would have observed at close quarters the effects of the often violent political changes taking place in Zululand in the 1880s. He arrived at Eshowe in the midst of a fierce conflict between Zulu royalists, or uSuthu, and rival groups which had coalesced into the uMandlakazi faction under Zibhebhu kaMaphitha. The latter had the often overt support of Osborn and other colonial officials, whose purpose was to destroy the still considerable authority of the Zulu royal house. In July 1883 a Mandlakazi force annihilated much of the uSuthu leadership in a surprise attack on Cetshwayo's homestead at oNdini. Cetshwayo himself escaped to Eshowe, where he died in February 1884. Soon afterwards the surviving uSuthu leaders, under Cetshwayo's son Dinuzulu, turned for help to Boers from the South African Republic, and with their assistance defeated the Mandlakazi and drove Zibhebhu into exile. The price paid by the uSuthu was to have to cede a large portion of the old Zulu kingdom to the Boers, who proceeded to set up in it a new statelet which they called the New Republic. In 1888 it was incorporated into the South African Republic. Meanwhile in 1887 Britain had annexed what was left of the kingdom as the colony of Zululand. Heavy-handed administration provoked a rebellion by uSuthu supporters under Dinuzulu in 1888; subsequently he and other uSuthu leaders were found guilty of treason and exiled to St. Helena.32

Socwatsha, James Stuart and Stuart's Idea

Upon the annexation of Zululand, Melmoth Osborn became resident commissioner and chief magistrate of the colony. The following year James Stuart, then just 20 years old, began his career in native administration when he was appointed as clerk and interpreter to the magistrate in Eshowe, Charles Saunders.33 A few months later, in February 1889, he was appointed to a similar post in Osborn's office. From the same month dates his first recorded encounter with Socwatsha, though no doubt the two men had come to know each other soon after Stuart's arrival the previous year. It is significant that at this meeting Stuart recorded four pages of Osborn's praises as given by Socwatsha. Though coming from utterly different backgrounds, they had been brought into conversation by a certain shared interest in local cultural issues. At this time Stuart was just 21 years old and, though he cannot be said to have yet begun to develop an informed interest in the African past, the seeds of his later work are already discernible.

For his part, Socwatsha, then aged about 36, had for years previously been an absorber of information about the past, and very possibly an active enquirer into it as well. We know that from his father Phaphu he had heard detailed anecdotes about the scattering of the Ngcobo people by Shaka in the late 1810s, and about his subsequent experiences when he lived among the Mkhize.34 As we have seen, Phaphu was in his late sixties when Socwatsha was born, and though, according to the latter, he had lived to a great age,35 Socwatsha must have heard these stories when he was still a young man, and have carried them with him. By the same token, he carried with him into later life an anecdote about Shaka which he had heard in his youth from Magudwini kaNala,36 and another about Theophilus Shepstone's settling a succession dispute among the abakwaNgcolosi when Socwatsha was still a youth herding cat-tle.37 More precisely dated is Socwatsha's account of Shepstone's visit to the Zulu kingdom in 1873 which he had heard about in Durban from one Pheni kaDubuyana soon afterwards.38 Similarly, he could recount years later a detailed eyewitness account of the assassination of Shaka which he had heard from Matingwana (Mantingwana) kaNdingiyana before the latter's death in about 1888.39 A passing statement made by Socwatsha to Stuart in 1921 suggests that historical matters were not infrequently a subject for discussion among the Zululand police in the 1880s.40 And we can imagine that Socwatsha would frequently have had conversations with Ndukwana kaMbeng-wana, another member of Osborn's staff with a deep interest in the past. Fourteen or fifteen years older than Socwatsha, he belonged to a section of the abakwaMthethwa people, and quite unlike Socwatsha, had grown up in the Zulu kingdom, and had been a frequent visitor to the courts of Mpande and Cetshwayo. He later became one of the most important of Stuart's interlocutors.41 In Eshowe, then, even if he was not fully aware of it to begin with, Stuart was in the company of men who shared his growing interest in African history and custom.

By the late 1890s this interest, in Stuart's case, was maturing into a conscious research project. Carolyn Hamilton and the present author have discussed its development elsewhere,42 and it will not be described in detail here. Suffice it to say that as his experience of native administration widened, Stuart became more and more concerned that Africans in Zululand and Natal (the two colonies became one when Zululand was annexed to Natal at the end of 1897) were being misgoverned. The root of the problem, in his opinion, was that, in their policies of seeking to establish tighter and tighter control over the colony's African population, successive Natal governments were departing further and further from the established system of ruling Africans through their own chiefs according to traditional tribal laws and customs. As Stuart saw it, this system had been developed from the late 1840s primarily by Theophilus Shepstone in his capacities first as diplomatic agent to the native tribes and then as secretary for native affairs in Natal, and had proved remarkably successful. But by the 1890s, after the departure of Shepstone from the scene, ignorance and neglect of the native system of government was leading to misrule.

All of which is not to say that Stuart did not share many of the racist opinions of his colonial contemporaries. He was a firm believer in the maintenance and propagation of white 'civilisation', but, in his view, this civilisation was being endangered by oppressive colonial rule of Africans. The answer to the problem, in Stuart's view, was for a qualified official, such as himself, to be tasked with researching the history and customs of Natal's African peoples, particularly the method of governance that had been developed by Shaka, and for the knowledge thus acquired to be used to inform native policy and also white colonial opinion. Pending the possible appointment of such an official, he would set himself to this business.

One of the first moves Stuart made in his project was to obtain a list of the Zulu king Mpande's amabutho or age-regiments from Socwatsha.43 This he did in January 1897, when he was magistrate at Ngwavuma in the far north of Zululand, though he does not indicate in his notes where their conversation actually took place. Nor does he indicate what Socwatsha's position was at this time - whether or not he was still in the colonial service, and whether or not he was still based in Zululand. Over the next two years Stuart was active in recording information on history and custom from fifteen or so individuals at Ngwavuma and in Swaziland, where he was acting British consul from October 1898 to April 1899.44 From 1899 to 1901, after moving from Zululand, Stuart was posted for short spells as acting magistrate in a number of centres in Natal south of the Thukela. He continued to make notes of discussions with various interlocutors, including a record of a single conversation with Socwatsha.45Most of these notes ran to no more than a few pages, but towards the end of 1900, when he was acting magistrate in Ladysmith for a period of several months, Stuart was for the first time able to record much more extended discussions, on the one hand with Ndukwana kaMbengwana, whom he had known since his time in Eshowe, and on the other with a group of local amakholwa (Christian) notables.46

In March 1901 Stuart was appointed assistant magistrate in Durban, the colony's largest town, and here, after a period of settling into what proved to be a more stable posting, he was able to begin work in greater earnest on what he was now calling his Idea. One of his first steps in this regard, in December 1901, was to send a messenger, in the person of the 64-year-old Dlozi kaLanga, one of Stuart's family retainers and also one of his interlocutors, to ask Socwatsha to travel to Durban over the New Year period to discuss history and custom with him. At this time Socwatsha was living in the homestead he had built on the land he had acquired at the Nsuze. As Stuart recorded his purpose, My object in getting Socwatsha is to have someone I know and who thoroughly understands Zululand and its principal people, who is moreover smart and would understand the object of my inquiry and take interest in it; he moreover could supply good information as to biography of various Zulu heads.47

Dlozi left on his mission on 12 December. On the 27th of the month he arrived back at Stuart's residence with Socwatsha, after the two them had walked the sixty or so kilometres from the Nsuze to Tugela railway station near the mouth of the Thukela River and then taken the train to Durban.48 Over the next nine days Stuart and Socwatsha held lengthy conversations on a variety of topics relating mainly to the origins, histories and customs of the 'tribes' north of the Thukela River, with a focus on the rule of the Zulu kings.49

The two men seem to have worked largely from two lists of questions drawn up by Stuart and recorded in his notes,50 with Socwatsha giving relatively brief answers and Stuart making relatively brief notes on each. One gets the impression that at this stage Stuart was still feeling his way into the history of the Zulu kingdom, probing a number of different topics in no great depth: the origins of various 'tribes'; the differences between 'Nguni', 'Ntungwa' and 'Lala' peoples; the history of Dingiswayo of the Mthethwa; the early history of the Zulu royal house; the izinduna, praise-singers, diviners and envoys of the kings; the sons and daughters of Mpande; the choice of Mbuyazi as Mpande's successor. He also enquired into Socwatsha's ancestry, and the origins and history of the Ngcobo people. The only extended anecdote related by Socwatsha related to the overthrow and death of Dingane. He also spent time giving Stuart a comprehensive list of the 'tribes' of Zululand in 1879, and in reciting praises of Zwide, Dingiswayo, Mzilikazi, Shaka, Cetshwayo, Maphitha, the Qwabe chief Phakathwayo, and the Ngongoma chiefs Mashisa, Mavela, Bhofungana and Mafongosi. On another note altogether, he and Stuart discussed at some length the grievances of Africans in Natal over the way in which they were being ruled by the colonial government. Present through almost all these conversations, occasionally adding his own comments and once or twice disagreeing with Socwatsha, though with what effect Stuart does not record, was Ndukwana.

In the middle of 1902 Stuart was able to begin more systematic work on his project. Over the next three years or so, he had conversations on the past with some sixty different people, including, on three different occasions, Socwatsha. The main focus of his enquiries at this stage was on the lives and reigns of the Zulu kings, particularly Shaka and Dingane, though he also recorded valuable information on the times of Mpande and Cetshwayo. In his notes, the statements made by his interlocutors again appear mostly as short comments and anecdotes: the main exceptions were extended narratives of Shaka's birth, youth, and death which Stuart elicited from several interlocutors, of differing backgrounds, who had detailed (and differing) knowledge of this subject. With several of his interlocutors, he returned to one of his abiding fields of interest - the government of Africans in the colony. From Socwatsha he recorded anecdotes on Shaka and Dingane, an account of the role of cattle in African society, and another of the practice of scarification among the Ngcobo.51

Socwatsha as a Narrator of the Past

From Stuart's notes of these early conversations we can get an impression of the forces that had shaped Socwatsha's particular position as a narrator of, and commentator on, past events, and also of the ways in which he put his knowledge of the past into conversations with Stuart. In no sense can he be seen simply as a purveyor of 'tribal traditions'; rather, he was a compiler of anecdotes and stories about the past, and a reciter of praises of historical figures, in ways that were shaped not only by anecdotes and stories and praises that he had heard from others but also by his own experiences and perspectives. Nor does the fact that nearly all the conversations he held with Stuart were about the history and customs of people who lived north of the Thukela River in what European colonists called Zululand make him a 'Zulu tribal historian'; it is more useful to see him in a broader sense as an informed commentator on, among things, the history of the Zulu kingdom. Far from being an insider among the Zulu and those clans related to or closely associated with it, he was, through his membership of the Ngcobo clan, very much an outsider. As we have seen, the Ngcobo were among those clans which, as amalala, had been categorised by the Zulu in the time of Shaka and Dingane as despised inferiors. We cannot be sure how far these resonances still existed among the societies of colonial Natal eighty years later, but the identification of the Ngcobo as amalala was still significant enough in Socwatsha's mind for him to mention it several times to Stuart in their early conversations and again as late as 1921.52 So was the fact that his father Phaphu had been an isancuthe,53 a person who had not had his ears pierced, a characteristic which would have led him to face ridicule from Zulu people.54 As a child, Socwatsha himself had had the little finger of his left hand scarified according to Ngcobo custom.55

In addition, as one born and brought up among those of the Ngongoma and other Ngcobo people who had fled across the Thukela and settled in what later became the colony of Natal, Socwatsha was very much a man of esilungwini, the white people's country. As he put it jokingly to Stuart, 'Nga klez esakeni le mpupu',56 ('I klezad from a bag of maize meal'). To kleza was literally to drink milk direct from a cow's udder; figuratively it meant to pass beyond the stage of boyhood by being enrolled in an ibutho or age-regiment. What Socwatsha was saying here was that he had never undergone this life-shaping experience because he lived in Natal, where he had grown up eating maize meal. He and other sources make clear that the colony's African inhabitants were still to some extent despised as amakhafula, or people 'spat out, by people living north of the Thukela.57 The former, for their part, continued to harbour ill-feelings towards the Zulu for having killed their chiefs and driven them out, though according to Socwatsha, speaking to Stuart in 1901, among younger people these feelings were dying away as they began to look to Cetshwayo's son and heir, Dinuzulu, for leadership against a common colonial oppression.58 A distinguishing feature of Africans south of the Thukela, Socwatsha said, was that they had led the way in breaking with old customs, with the implication that the people of the old Zulu kingdom were more conservative.59 In this regard, it is worth noting Socwatsha's statement, made to Stuart in the course of one of their early conversations, that he himself no longer turned to diviners for assistance in explaining unexpected events as he had lost faith in them.60 There is, though, no indication in Stuart's notes that Socwatsha ever became an ikholwa, or Christian convert, at a time when amakholwa were widely seen as cultural innovators;61 in this sense he seems to have remained a traditionalist all his life. According to the testimony of Nsuze kaMfelafuthi, Socwatsha always wore izincweba, or small bags of protective medicine.62

In seeking to widen our understanding of Socwatsha's perspectives on the past, we need to consider the implications of a statement that he made to Stuart but which unfortunately is not elaborated on in the latter's notes, to the effect that 'We went and konza'd [gave allegiance] to Mbuyazi'.63 The context was a conversation about the dispute over the succession to the Zulu kingship between two of Mpande's sons, Cetshwayo and Mbuyazi, which had culminated in the defeat and death of the latter in a fierce battle at Ndondakusuka near the mouth of the Thukela in 1856. Other sources record that before the battle Mbuyazi had crossed over to the Natal side of the river to seek assistance from the colonial government;64 Socwatsha may be indicating that on this occasion leaders of the Ngongoma and Ngcobo groups at oZwathini, sixty kilometres from the Thukela, had gone to assure him of their allegiance. If this is the case, they were making a move which then, and subsequently, would have set these groups against the house of Cetshwayo. It is notable, too, that Socwatsha was able to recite to Stuart the praises of Mbuyazi's mother, Monase kaNtungwa of the abakwaNxumalo people.65 Carolyn Hamilton has discussed how major political events in the Zulu kingdom, including the civil war of 1856, were important factors inside and outside the kingdom in shaping particular lineages of historical memory;66if Socwatsha was an 'Mbuyazi man', it may have made him yet more of an outsider in his commentaries on the histories of the Zulu kings.

This may have been why he took up stories, commonly told among Shaka's opponents, about Shaka as a madman (uhlanya) who cut open a pregnant woman and killed his own mother.67 And why, according to Socwatsha's own account, he and others of Osborn's police seem to have sympathised with Zibhebhu in his struggle against the uSuthu.68 It may also help explain why he did not know some of the finer points of the history of the Zulu royal house, like the name of the induna of Senzangakhona, Shaka's father, or that Nyakamubi was the name of one of Shaka's imizi (homesteads) and not that of one of his sisters.69 In the same vein we can note that according to Stuart early on in their conversations, Socwatsha was not 'satisfactory' in reciting the praises of the Zulu kings.70 By Socwatsha's own account his brother Godloza was the imbongi in the family.71

At the level of individual experience, we can imagine that the fact that Socwatsha lived the first thirty years of his life in the colony of Natal gave him a different outlook on the future, and therefore on the past, from what he would have had if he had been born and brought up in the Zulu kingdom. He would have grown up expecting a future in which he spent much of his time working for wages in the employ of white people rather than serving in one of the Zulu kings' amabutho. He would have learnt at first hand about white people's laws and the (changing) ways of colonial officialdom. He would have learnt something of life in the colony's slowly growing towns. He and the community he belonged to would have escaped the devastating effects of the British invasion of the Zulu kingdom in 1879, and of the fierce civil wars which followed. And the fact that, as a policeman, he was a 'Government man' rather than a resister, at a time when resistance to white rule among Africans in Natal was growing, would have placed him in a particular relationship with Stuart, the colonial official. These points will become clearer as we discuss their ongoing conversations with each other.

New Lines of Discussion

The historical enquiry that both Socwatsha and Stuart, in their different ways, were involved in came to a sudden stop with the rapid growth of political tensions in Natal late in 1905 and outbreaks of rebellion against the government early in 1906.72Socwatsha was living at his home in Chief Ndube's ward on the lower Nsuze when, in April 1906, rebel forces led by Chief Bhambatha kaMancinza Zondi moved through the area and proceeded to set up a base in the Nkandla forest nearby. Large numbers of Ndube's adherents made off to join the rebels, partly out of sympathy with their cause and partly to avoid losing their livestock to rebel raids. Socwatsha, who was one of Ndube's close advisers, seems to have played an important role in keeping lines of communication open between the chief and the colonial authorities, and in persuading Ndube not to go over to the rebels.73 At the end of April Ndube fled for safety to the magistracy at Eshowe. There is no indication as to whether Socwatsha was one of the men who went with him or whether he preferred to remain at home and see out the rebellion. In the event, early in June Bhambatha's force was trapped in the Nkandla forest by colonial troops, and the chief and many of his men killed.

For his part, Stuart joined the colonial forces at the outbreak of the rebellion in his capacity as a captain in the Natal Field Artillery. Because of his knowledge of the colony's African people and their language, he was almost at once seconded as an intelligence officer to the staff of one of the column commanders.74 In this capacity he was closely involved in operations against the rebels in the Greytown-Nkandla area, and then, in the final stages of the rebellion in July, in the lower Mvothi-lower Thukela region. As will be discussed below, Stuart later wrote a detailed account of military operations during the rebellion, but he makes virtually no mention of his own experiences. In the aftermath of the rebellion he held official office first as a member of the court martial that tried numbers of the rebels who had been with Bhambatha,75 and then as secretary to the Native Affairs Commission which was set up by the Natal government in September 1906 to enquire into the causes of the rebellion and to decide whether changes in native policy were needed.76 In December 1907, still in his capacity as intelligence officer, he was involved in the arrest of Dinuzulu near Nongoma in Zululand on charges of treason.77 With him in Zululand was Socwatsha.78 It is likely that the latter was now also employed, presumably on Stuart's recommendation, in the colonial intelligence service, which had been greatly expanded during the rebellion.79 Where he was based is not recorded.

After the rebellion Stuart began to make brief notes on conversations he engaged in with a number of individuals on its causes. One of the factors impelling him to take up this new line of research was his acceptance towards the end of 1906 of a request from the Natal government to write a history of the rebellion.80 In the course of 1907 he also resumed his work of recording conversations with various interlocutors on the political history of the Zulu kingdom. At this time his official duties were taking him between Durban, Pietermaritzburg and Zululand, and he had little opportunity of engaging in, and recording, extended discussions. Over the next two years or so, the notes he made seem to have been based much more on chance conversations, and were generally much briefer, than had been the case in the period 1902-5 when he began developing his research project. His recording work was once again interrupted for an extended period when, in July 1909, he was promoted to the post of assistant secretary for native affairs and was transferred to Pietermaritzburg. He was able to take up his research again in February 1910, but by this time he would probably have known that his post was due to be abolished at the end of May when Natal became a province of the new Union of South Africa, and its Native Affairs Department was incorporated into a national Native Affairs Department. The last of Stuart's conversations in this period of his career dates to June 1910; at this point he was transferred to a post in Pretoria and his researching and writing work for a while came to an end.

In the period from the end of 1906 to the middle of 1910, Stuart had made notes of conversations with fifty or so interlocutors. In turning to Socwatsha, on several different occasions Stuart questioned him about his knowledge of the rebellion.81 His statements that it had been caused mainly by grievances over the growing shortage of land for African occupation, high rents, and the imposition of a poll tax by the Natal government would have been familiar enough to Stuart from statements made to the Native Affairs Commission of 1906-7 by numbers of African witnesses (one of whom was Socwatsha himself). Of more interest to Stuart were Socwatsha's own experiences in the phase of the rebellion when Bhambatha took refuge in the Nkandla forest and sought to stir up support from neighbouring chiefs. The eye-witness account that he received from Socwatsha fed directly into the narrative that he later wrote in his history of the rebellion.82 A long, generalised description of warfare in the Zulu kingdom that Stuart recorded from Socwatsha verbatim in Zulu - an unusual practice for him at this stage - no doubt also informed the chapter that he wrote in his history on 'Zulu military system and connected customs'.83 In this connection we should note that Socwatsha had no first-hand knowledge of warfare in the Zulu kingdom: all his information on the subject would have been derived from other people. In a totally different field, Stuart found time to investigate at some length Socwatsha's knowledge of what he noted as 'Superstitions'.84

Stuart found that he had little useful work to do in Pretoria as acting assistant secretary for native affairs in Natal, and in the event decided to resign from the Native Affairs Department and take the pension which became due to him in June 1912.85He had long leave owing to him, which is presumably why, by the beginning of 1912, he was back in Pietermaritzburg and pursuing research into his Idea and also into two other projects. One of these was writing a biography of Theophilus Shepstone. Apparently at the request of members of the Shepstone family, he had begun actively researching and interviewing on this topic before he left for Pretoria, and continued to work on it after his return to Pietermaritzburg.86 For a while there was talk of his working on this project with the well-known writer Henry Rider Haggard, who had known the Shepstone family since his sojourn as a young man in South Africa in the 1870s, but in the end nothing came of this plan.87

At the same time Stuart resumed research work in another field of interest. This was the history of the Natal rebellion of 1906, which he had been commissioned to write by the government of Natal when the region was still a separate colony. After the formation of the Union of South Africa in 1910, the new national government had withdrawn support for the project,88 at which point Stuart had taken it up as his own concern. He spent most of the second half of 1912 working on it, using mainly colonial documentary sources but also evidence drawn from conversations with a number of interlocutors, black and white, loyalists and rebels, including Socwatsha.89At the end of the year he travelled to London to see the resulting book through publication by Macmillan. After some fraught negotiations between Stuart and the publishers, it came out the following year under the title A History of the Zulu Rebellion 1906.90

In August 1913 Stuart was back in Natal. Within a few days he interviewed Socwatsha in connection with a mission to Zululand that the latter had been sent on during Stuart's absence by Arthur Shepstone, chief native commissioner in Natal, to speak to people who could tell him about Theophilus Shepstone's visit to King Mpande in 1861. The detailed account that Socwatsha gave of the conversation that he had had with Lutholuni kaZucu at Nkandla nearly a year before is testimony to his powers of memory and of narration.91 That Socwatsha was still an agent of the Native Affairs Department, and presumably operating from time to time from Pietermaritzburg, is confirmed by the point that he was one of the men responsible for reporting to the department on the funeral of Dinuzulu at kwaNobamba in October 1913.92 In the same month Stuart also interviewed Socwatsha at length on a story about the death and burial of Shaka that he had been told at least twenty-five years before by Mantingwane kaNdinginyane, and that he had previously recounted to Stuart in 1905 and again in 1910.93 It may be that at this time Stuart was beginning to work on yet another project, one that involved collecting stories for publication in Zulu for a readership of schoolchildren. As we shall see, he did not begin active work on it until a few years later; in the meantime, with his Idea still in mind,94 he continued to hold and record conversations, mostly brief, with a variety of interlocutors on the history of the Zulu kingdom and its constituent chiefdoms.

In March 1914 Stuart met Rider Haggard, who was on a visit to South Africa, in Pietermaritzburg. Stuart introduced him to Socwatsha, from whom Haggard obtained much of the historical background that went into his novel Unfinished (published in 1917). Haggard recorded in his diary that in narrating stories Socwatsha was something of a performer.95 The following month Haggard and Stuart made a tour to Zululand, before Haggard left on his return voyage. In July of that year Stuart travelled to London to act as adviser on Zulu customs for a play based on Child of Storm, another of Haggard's novels. While he was on his voyage to Britain, war broke out in Europe. In the event, he remained in London until the end of 1915.

Socwatsha and Stuart's Zulu Readers

By the time he returned home, Stuart seems to have decided to devote his energies to his project of collecting stories about what he and others would have called the 'Zulu' past for publication in school readers. This entailed something of a change in his working method. He continued to engage in conversations about the past with numbers of interlocutors, some of them already known to him, and to record notes on a variety of topics, but in addition he held what we might call more formal interviews with those of them whom he regarded as both especially knowledgeable and as good narrators. In these there was less by way of conversation and more by way of Stuart's asking his interlocutor to tell a story in a measured way, while he recorded their narrations verbatim in Zulu. Not infrequently he might ask an interlocutor to give an extended version of an anecdote he had briefly recorded on a previous occasion.

By this stage of Stuart's career, six and more years after Union and the shift of overall control of native affairs to faraway Pretoria, he was motivated less by the hope of being able to work changes in native policy in an industrialising and urbanising South Africa than by the aim of putting into writing accounts of 'traditional' Zulu history and custom for the long-term benefit of a generation which, to its own detriment, was rapidly forgetting its own heritage. In the prefaces to the five Zulu readers which he eventually published between 1923 and 1926,96 he indicates that the idea of writing them had originally come to him at the time of the three Zulu orthography conferences held in Durban and Pietermaritzburg in 1905-7, but his writings from 1913 onwards make clear that his prime aim by this time was to write in support of the tribal system, which he regarded as the bedrock of proper governance of Africans. He had concluded his History of the Zulu Rebellion with a peroration to this end,97 and his unpublished writings contain numerous elaborations of his ideas in this field.

Particularly pertinent is a memorandum, dated 20 July 1919, entitled 'The motive for publishing my various works on the Zulu people'.98 In this Stuart inveighs against what he sees as the misguided desire of some Africans to cut themselves adrift 'from their former modes of life and therefore from all the traditions of an immeasurable past' by imitating white people. His aim, as he put it, was to provide the Zulu people 'with a fountain at which all must at all times drink in order that, mindful of a strenuous past, they become men of character and backbone, not a mongrel set of waifs and strays, blind as to their past and, therefore, blinder still as to their future ...'99 In another note, written in the same month, he expressed regret at the tendency among some Africans, mainly in 'so-called educated households', to disregard traditions and to chase after opportunities for personal profit and advancement in place of proceeding along 'fundamentally natural lines'.100

As a source on what he saw as the 'traditional' past, Stuart turned in the first instance to his long-standing interlocutor Socwatsha. In April 1916 he recorded three long anecdotes from him. One was on the marriage of the Nyuswa chief Mapholoba to a woman of the Mkhize people in the early nineteenth century and the elevation of Sihayo by Shaka to the Nyuswa chiefship.101 A second was on Theophilus Shepstone's visit to Mpande and Cetshwayo in 1861, based on an account Socwatsha had heard from Lutholuni kaZucu.102 A third was on a quarrel between Zihlandlo, ruler of the Mkhize chiefdom, with Zombane, ruler of the Bomvu chiefdom, again in the early nineteenth century.103

Stuart continued with his recording and writing work for another two months, then once again interrupted it, this time to become involved in South Africa's war effort. In the second half of 1916 he was engaged in an official drive in Zululand to recruit men for the army's Native Labour Contingent, and at the beginning of 1917 left with a detachment of the contingent, in which he held his former rank of captain, for the theatre of war in France. It was not until the end of the year that he was back in Natal, and not until April 1918 that he was able to begin his researches again. Towards the end of June he and his wife Ellen, whom he had married in Ladysmith in 1916, travelled to the homestead of Mpathesitha of the Magwaza, who had succeeded his father Ndube as chief of the ward near the Nsuze River where Socwatsha had his home. Here they lived in a tent for nearly a month, while Stuart recorded numbers of praises from knowledgeable men who came to visit him, presumably at the behest of Socwatsha.104 From the latter, Stuart obtained the praises of Ndlela kaSompisi, one of Dingane's chief izinduna, as well as Socwatsha's praises of himself and of Stuart.105 He also met Socwatsha's wife Nomvumbi, of the abakwaMbamba people, and recorded three children's tales from her.106 This is one of only two references in Stuart's notes to Socwatsha's own family, the other being a passing reference to his first wife (left unnamed) whom he had married while living at oZwathini.107

This was the last session of concentrated research that Stuart engaged in for more than two years. In the interim his mother died and Stuart was busy moving his household from Pietermaritzburg to Hilton, a small village on the heights overlooking the city. He did some spasmodic recording work after his move, but it was not until December 1920 that he was able to settle down to what turned out to be his final spell of conversing and writing. By this time, for reasons that he does not record, Stuart and his wife had fairly certainly decided to leave Natal and settle in London.108Through 1921 and the first three months of 1922 he was hard at work recording stories and descriptions of customs from some two dozen interlocutors. Much of what he recorded was by way of long accounts, written in Zulu, that he was clearly eliciting with a view to publishing them in the school readers that he now had in mind. Nearly all these accounts related to the history of the Zulu kings; outside this master narrative Stuart was now recording very little.

In August 1921 and again in October, for the first time in three years, he had long and intensive working sessions with the ever-reliable Socwatsha, who had presumably been invited to Hilton for the purpose. He was now in his late sixties, and had known Stuart for some thirty-three years. It is pertinent to note that in this period of his life, as Paul la Hausse has indicated, he was also an important source of oral history for Carl Faye, a senior official in the Natal Native Affairs Department, in his revision of the Index to the Natal Tribes Register published in 1923. La Hausse describes Socwatsha as 'a long-standing employee of the Natal NAD with a reputedly vast knowledge of Zulu history.109 Many of the stories that Socwatsha told Stuart on this occasion were on topics that the latter had previously noted in brief but was now concerned to record in detail. Among them were an account of the Madlathule famine of the early years of the nineteenth century, the wars between Shaka and Zwide of the Ndwandwe, Shaka's attack on the Ngongoma people, Shaka and the death of his mother Nandi, Bhongoza's decoying of the Boers in 1838, the overthrow and death of Dingane, relations between Cetshwayo and Theophilus Shepstone, the restoration of Cetshwayo in 1883, relations between Cetshwayo and Zibhebhu, and the succession of Dinuzulu.

The final recording session that Stuart held before his departure for Britain dates to the end of March 1922. It was perhaps fitting that among his three interlocutors on this occasion was Socwatsha, who described in detail how headrings were made and sewn on.110 This is the last of him that we hear from Stuart, but it was by no means the end of his significance in Stuart's career as a writer of history. We now know that his accounts of history and custom constituted a particularly important source for Stuart when, after the latter's arrival in London, he began working with Longmans, Green on the publication of his history readers. Most of the stories published as chapters in these readers were drawn verbatim from Stuart's notes of conversations with his interlocutors, but with very few exceptions the narrators remained unnamed. Their anonymously presented accounts were absorbed as anecdotes in what would have been widely understood, not least by Stuart himself, as books on the overall subject of 'Zulu history and custom'.

Stuart made clear in the prefaces to the books that the contents had been obtained from African interlocutors, but it was not until the 1970s, with the inception of editorial work on the Stuart Archive, that their identities began to be rediscovered. So far 34 of his interlocutors have been identified; between them they narrated the stories that made up 98 of the total of 241 chapters in his readers. Among them is Socwatsha, whose narrations, many of them recorded by Stuart in August and October 1921, form 18 of these chapters. For the most part, they are stories about Shaka, Dingane and Cetshwayo, and about the Nyuswa and Ngongoma in the time of Shaka.

A study of the production and circulation of Stuart's readers, and of the influence that they might have had, is sorely needed. All that can be said here is that they were prescribed for reading in African schools in Natal and remained in print from the time of their publication until the early 1940s, when they were superseded by a new generation of textbooks.111 Overseeing their distribution to schools was the provincial Department of Native Education which, from 1920 to 1944, was headed by Daniel Malcolm.112 He had been a junior colleague of Stuart in the Natal Native Affairs Department from 1906 to 1910 and had no doubt known Socwatsha as well. A full study of the history of the readers would need to take into account the tensions and conflicts over the writing of Zulu history which, as La Hausse has indicated, were surfacing in Natal and elsewhere with the rise of Zulu ethnic nationalism after World War I.113 For her part, in her study of the use of history in the making of Zulu nationalism, Daphna Golan has argued that Stuart's readers played an important role in the shaping of a 'Zulu' consciousness in this period.114

Because they were written in Zulu, Stuart's books were largely inaccessible to the white academic historians who dominated the writing and teaching of history in South Africa's universities throughout the twentieth century. Academic historians inside and outside the country in any case showed little interest in the history of African societies until the 1960s and 1970s. But, outside the ranks of the history profession, writers like the former missionary Alfred Bryant and the journalist Rolfes Dhlomo used Stuart's readers in detail as sources for their own works and, even if unknowingly, in doing so carried the then anonymous narrations of interlocutors like Socwatsha to a much wider readership. Writing in Olden Times in Zululand and Natal (1929), Bryant cites Stuart's readers at numerous points, but not always consistently. Thus a close reading of his text, together with the texts of the readers and of Stuart's notes of his conversations with Socwatsha as published in volume 6 of the Stuart Archive, is needed to discover that of the 18 narrations given by Socwatsha and published by Stuart, Bryant used at least seven to inform the narrative and the clan histories that he published in Olden Times. Three of these were on the history of the Nyuswa and Ngongoma, three on Shaka, and one on a quarrel between the Mkhize and Bomvini chiefs. Bryant's book remained the standard work of reference on 'Zulu' history until at least the 1970s, and is still widely consulted today: through his renderings, the narrations of Socwatsha, as well as others of Stuart's interlocutors, live on in the present.

It can be established that Dhlomo, for his part, used at least two of Socwatsha's narrations as published in Stuart's readers when he was writing UShaka, his partly fictional account of the life of Shaka, published in 1937. He may well have used others in his UDingane (1936), UMpande (1938), UCetshwayo (1952) and UDinuzulu (1968): this still remains to be established. The salient point is that Dhlomo's books, especially the first two mentioned, were very widely read, both by schoolchildren and by Zulu-speaking intellectuals. UShaka remained in print until at least the 1980s.115 In contrast to their treatment in academia, Stuart's readers became well known in the Zulu-speaking world.

So much for the 'afterlife' of Socwatsha's renderings of the past. What can be said of their backstories? Stuart records the names of a dozen of Socwatsha's own interlocutors. Important among them was Socwatsha's father Phaphu, who is given as recounting stories on the history of the Ngcobo clans, on the Madlathule famine that he lived through in the very early years of the nineteenth century, and on how Bhongoza kaMefu, who was himself of the Ngongoma clan, decoyed a Boer force into an ambush in 1838. Anecdotes on the war between the Ndwandwe and Zulu in the late 1810s came from Bovu kaNomabhuqabhuqa and Makhobosi, both of whom apparently lived at oZwathini, and from Mzuzu kaNkathaza and Xawana. From Nohadu kaMazwana and Mantingwane kaNdingiyana, both of whom had been household attendants of Shaka, came stories about the Zulu king; another came from Magudwini kaNala, who had been a mature man at the time of Shaka's reign and whose own source was fairly certainly Gala kaNodade. The death of Dingane in 1840 was described by Shibela kaMakhobosi who, as a young warrior, had been present at the time and was still alive in 1901, and also by Ndube kaManqondo, chief of the region where Socwatsha lived. As already indicated, Lutholuni kaZucu gave Socwatsha an eye-witness account of Theophilus Shepstone's visit to Mpande and Cetshwayo in 1861; it was partly confirmed on a different occasion by Mhlahlo kaBhekeleni. Pheni kaDubuyana gave an eye-witness account of Shepstone's visit to Cetshwayo in 1873. As for the praises of Cetshwayo which Socwatsha declaimed to Stuart, he had heard these, he said, from Vumandaba kaNtethi, who had been an inceku and an induna under Mpande and who was killed at oNdini in 1883, from Zimu kaMadlozi, who had been a policeman at Eshowe, and from Maxeshana kaVumbi, who lived near Socwatsha at the Nsuze.

These were undoubtedly only a few of the people with whom Socwatsha conversed about the past during his lifetime. What little information Stuart records on them suggests that they can be grouped into three clusters: one consisting of people he spoke to as a young man living at oZwathini, a second consisting of fellow police and officials whom he met in Zululand in the 1880s, and a third consisting of acquaintances from the Nsuze region where he later lived. This is consistent with the fact that most of the anecdotes and stories Socwatsha related to Stuart pertained to the history of the more southerly regions of Zululand; apart from brief accounts involving relations between Cetshwayo, Zibhebhu, and Dinuzulu in the 1880s, which Socwatsha would have known about through his work as a policeman at the time, there is little relating to the history of northern Zululand.

In some cases, Socwatsha's naming of his interlocutors allows us to extend back in time the lineages of the stories which he told Stuart and which Stuart published in his readers. To take perhaps the most revealing example: probably early in 1828 Gala kaNodade tells a story of his recent nerve-racking encounter with Shaka to Magudwini kaNala, the man who sewed on Gala's headring. In his old age, Magudwini, who then lived near oZwathini, tells the story to a young Socwatsha. In 1904, and then again at much greater length in 1921, Socwatsha relates the story to Stuart. In 1924, Stuart publishes the longer version in Zulu in uHlangakula. Bryant picks it up and puts an abbreviated anecdote, in English, into Olden Times in 1929. In 1937 Dhlomo also publishes an abbreviated account, in Zulu, in UShaka. Through these three books Gala's story goes out to the wider world. But only in 2014, with the publication of Socwatsha's story in volume 6 of the Stuart Archive, do we have the information available that allows the story's chain of transmission to be reconstructed. It may prove possible to do similar detective work on others of the stories published by Stuart; this particular case allows us to glimpse something of the particular circumstances in which Socwatsha came by his knowledge of the past, and also something of the historical processes in which the broader archive of published oral histories on Zululand and Natal was produced.

Conclusion

Though Stuart conversed with others of his interlocutors at length and on numerous different occasions, Socwatsha was the one with whom he engaged most often in discussions about the past. In the early 1900s, when Stuart was developing his Idea, Socwatsha was a major source of information on the history of the Zulu kings and on African customs and methods of governance. In the period after the rebellion of 1906 when Stuart was pursuing a number of new research topics, Socwatsha provided detailed testimony on his experiences of the rebellion and on important moments in the life of Theophilus Shepstone. And in the period 1916-22, when Stuart was gathering material for his Zulu readers, Socwatsha was one of the storytellers whose narrations he most frequently recorded. Over the years Socwatsha would have been an important influence in shaping the picture of the 'Zulu' past that Stuart built up in his mind and that informed the development of his research work, including the conversations that he held with his successive interlocutors.

At the centre of Stuart's picture was the history of the Zulu kings, whom he, like many other commentators, saw as the key figures in the exercise of 'tribal' governance. Even if Socwatsha did not have the kind of inside knowledge of the affairs of the Zulu royal house that others of Stuart's interlocutors had, he had acquired insights into African law and custom in the past that Stuart found again and again he could tap into. And in a time of rapid social and economic change, when many Africans were turning their backs on 'traditional' rural society, Socwatsha remained for him a dependable source of knowledge of the 'tribal' past.

More difficult to assess is the influence that Stuart had in shaping Socwatsha's own perspectives on the past over the long period when they worked together. Stuart did not record whether it was ever his practice to ask Socwatsha to seek out information on specific topics; it remains a possibility. But it is likely that the particular lines of questioning which Stuart pursued would have encouraged Socwatsha to see past events in new ways, and perhaps to discuss with his own interlocutors topics that otherwise might not have engaged his interest. And, at a later stage, in responding to Stuart's requests for stories to put into his readers, Socwatsha may well have gone out of his way to work up his knowledge of the past into structured narratives to a greater degree than he might otherwise have done.

From their very different backgrounds, Stuart and Socwatsha were drawn into prolonged conversation about the African past by the value which each set on maintaining 'tribal' ways in the present that they inhabited. But we should not allow their common interest in doing so to obscure the differences in their perspectives. For Stuart, knowledge of the past was a key to a better understanding of a generic tribal system, which he saw as the basis for good governance of Africans. For Socwatsha, one suspects that knowledge of a 'traditional' past served less to prop up a system that in many ways had become part of an oppressive colonial presence than to give continued validity to the moral order of the community in which he lived, and to lend meaning to his position in it as a man of substance, a 'worthy ancestor'.116

1 My thanks to Andrew Bank and three anonymous referees for particularly useful comments on an earlier draft of this essay; and to Carolyn Hamilton, holder of the NRF chair in Archive and Public Culture at the University of Cape Town, who first encouraged me to pursue research into the biographies of James Stuart's interlocutors.

2 C. Webb and J. Wright (eds), The James Stuart Archive of Recorded Oral Evidence Relating to the History of the Zulu and Neighbouring Peoples (JSA) vol 6 (Pietermaritzburg: University of KwaZulu-Natal Press, 2014), 1-207. [ Links ] Vols 1 to 5 in the series were published by the University of Natal Press, as it was then known, in 1976, 1979, 1982, 1986 and 2001.

3 JSA, vol 4, 263-406.

4 J. Wright, 'Ndukwana kaMbengwana as an Interlocutor on the History of the Zulu Kingdom, 1897-1903, History in Africa, 38, 2011, 343-68. [ Links ]

5 C. Hamilton, 'Backstory, Biography, and the Life of The James Stuart Archive', History in Africa, 38, 2011, 319-41; [ Links ] Wright, 'Ndukwana kaMbengwana'.

6 For example, N. Jacobs, 'The Intimate Politics of Ornithology in Colonial Africa', Comparative Studies in Society and History, 48, 2006, 564-603; [ Links ] A. Bank and L.J. Bank (eds), Inside African Anthropology: Monica Wilson and Her Interpreters (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013). [ Links ]

7 In this essay, the name of a clan will be given with its prefix when first mentioned, and without it when subsequently mentioned, or when used adjectively.

8 JSA, vol 6, 6, 14, 125, 134.

9 Ibid, 125, 127, 135.

10 Ibid, 6, 24.

11 Ibid, 146.

12 C. Hamilton, 'Ideology, Oral Traditions and the Struggle for Power in the Early Zulu Kingdom' (Unpublished MA thesis, University of the Witwatersrand, 1985), 370-2, 474-6; [ Links ] J. Wright, 'The Dynamics of Power and Conflict in the Thukela-Mzimkhulu Region in the Late 18th and Early 19th Centuries: A Critical Reconstruction' (Unpublished PhD thesis, University of the Witwatersrand, 1989), 180-1, 230-1. [ Links ]

13 Socwatsha in JSA, vol 6, 4, 135-8; A. Bryant, Olden Times in Zululand and Natal (London: Longmans, Green, 1929), 481-4, 487, 490-3, 496, 497; [ Links ] Hamilton, 'Ideology, Oral Traditions', 476-7; Wright, 'Dynamics of Power', 232-8.

14 JSA, vol 6, 4, 19, 24, 87, 134, 135.

15 Ibid, 135.

16 Bryant, Olden Times, 412-14.

17 JSA, vol 6, 116.

18 Bryant, Olden Times, 414-15; Mbokodo kaSikhulekile, testimony in JSA, vol 3, 7-8, 16-18.

19 Socwatsha in JSA, vol 6, 4, 7.

20 C. Hamilton and J. Wright, 'The Making of the Amalala: Ethnicity, Ideology and Relations of Subordination in a Precolonial Context', South African Historical Journal, 22, 1990, 3-23; [ Links ] C. Hamilton, 'Political Centralisation and the Making of Social Categories East of the Drakensberg in the Late Eighteenth and Early Nineteenth Centuries', Journal of Southern African Studies, 38, 2012, 291-300; [ Links ] J. Wright, 'A.T. Bryant and the "Lala,"' Journal of Southern African Studies, 38, 2012, 355-68. [ Links ]

21 JSA, vol 6, 129.

22 Bryant, Olden Times, 493.

23 For Stuart's calculations of Socwatsha's birth date and age see JSA, vol 6, 6, 11, 127, 135.

24 Ibid, 6, 49.

25 Ibid, 6, 101.

26 Ibid, 157.

27 J. Lambert, Betrayed Trust: Africans and the State in Colonial Natal (Pietermaritzburg: University of Natal Press, 1995), ch 5.

28 JSA, vol 6, 20, 36, 49, 157.

29 Ibid, 49.

30 S. Marks, Reluctant Rebellion: The 1906-8 Disturbances in Natal (Oxford: Clarendon, 1970), 316n; [ Links ] J. Guy, The View Across the River: Harriette Colenso and the Zulu Struggle Against Imperialism (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 2001), 109, 256. [ Links ]

31 JSA, vol 6, 119, 121.

32 These events are discussed in detail in J. Guy, The Destruction of the Zulu Kingdom (London: Longman, 1979); [ Links ] Guy, View Across the River; J. Laband, Rope of Sand: The Rise and Fall of the Zulu Kingdom in the Nineteenth Century (Johannesburg: Jonathan Ball, 1995). [ Links ]

33 On Stuart's early career see Wright, 'Ndukwana kaMbengwana, 352-3. A brief outline of his life appears in J. Wright, 'Stuart, James (1868-1942)', Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford: University Press, May 2006); [ Links ] online edn October 2006.

34 JSA, vol 6, 114-17.

35 Ibid, 14, 135.

36 Ibid, 140.

37 Ibid, 141.

38 Ibid, 101.

39 Ibid, 50-1, 86, 94-7.

40 Ibid, 145.

41 Wright, 'Ndukwana kaMbengwana', 346-52, 356ff.

42 C. Hamilton, Terrific Majesty: The Powers of Shaka Zulu and the Limits of Historical Invention (Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press; Cape Town: David Philip, 1998), 130-56; [ Links ] Wright, 'Ndukwana kaMbengwana', 352-6.

43 JSA, vol 6, 1.

44 Wright, 'Ndukwana kaMbengwana', 353-4.

45 JSA, vol 6, 2-5.

46 Wright, 'Ndukwana kaMbengwana', 354.

47 JSA, vol 6, 5.

48 Ibid, 6.

49 Ibid, 6-36.

50 Ibid, 10-11, 15-17.

51 Ibid, 36-51.

52 Ibid, 4, 6, 7, 18, 104, 135-6, 137, 138, 157.

53 Ibid, 19.

54 A. Bryant, The Zulu People as They Were Before the White Man Came (Pietermaritzburg: Shuter and Shooter, 1949), 112. [ Links ]

55 JSA, vol 6, 48-9.

56 Ibid, 11.

57 Socwatsha in JSA, vol 6, 5; A. Bryant, A Zulu-English Dictionary (Mariannhill: Mariannhill Mission, 1905), 286. [ Links ]

58 JSA, vol 6, 5.

59 Ibid, 36.

60 Ibid, 30.

61 See Socwatsha's own comments in JSA, vol 6, 30.

62 JSA, vol 5, 165.

63 JSA, vol 6, 31.

64 Laband, Rope of Sand, 142.

65 JSA, vol 6, 166.

66 Hamilton, Terrific Majesty, 54-69.

67 JSA, vol 6, 43, 85.

68 Ibid, 166.

69 Ibid, 10, 86.

70 Ibid, 9.

71 Ibid, 26.

72 The standard work on the rebellion is still S. Marks, Reluctant Rebellion: The 1906-1908 Disturbances in Natal (Oxford: Clarendon, 1970). [ Links ] For recent accounts see B. Carton, Blood from Your Children: The Colonial Origins of Generational Conflict in South Africa (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 2000); [ Links ] J. Guy, The Maphumulo Uprising: War, Law and Ritual in the Zulu Rebellion (Pietermaritzburg: University of KwaZulu-Natal Press, 2005); J. Guy, Remembering the Rebellion: The Zulu Uprising of 1906 (Pietermaritzburg: University of KwaZulu-Natal Press, 2006); P. Thompson, Bambatha at Mpanza: The Making of a Rebel (Pietermaritzburg [?]: private publ, 2004).

73 On these events, see the testimonies subsequently given to Stuart by Socwatsha in JSA, vol 6, 53-8; Hayiyana kaNdikila, JSA, vol 1, 162-4; and Nsuze kaMfelafuthi, JSA, vol 5, 174-5; also the account later written by Stuart in his A History of the Zulu Rebellion 1906 (London: Macmillan,1913),166-86, 228-9.

74 P. Thompson, 'Colonial Military Intelligence in the Zulu Rebellion, 1906', Scientia Militaría: South African Journal of Military Studies, 42, 2014, 25. [ Links ]

75 Marks, Reluctant Rebellion, xxi.

76 P. Forsyth, 'Natal "Native Policy" in the Aftermath of the "Bhambatha Rebellion", 1906-9' (Unpublished BA Honours dissertation, University of Natal, Pietermaritzburg, 1985). [ Links ]

77 Stuart, Zulu Rebellion, 447; C. Binns, Dinuzulu: The Death of the House of Shaka (London: Longmans, 1968), 240-3. [ Links ]

78 Killie Campbell Africana Library, Durban (KCAL), James Stuart Collection, file 8, letter from Stuart to his mother, 8 December 1907.

79 Marks, Reluctant Rebellion, 150.

80 Stuart, Zulu Rebellion, vii.

81 JSA, vol 6, 51-60; also Socwatsha's comments recorded under the testimony of Nkantolo, JSA, vol 5, 133-4.

82 JSA, vol 6, 52-60; Stuart, Zulu Rebellion, 182-8.

83 JSA, vol 6, 60-9, 73-5; Stuart, Zulu Rebellion, 67-89.

84 JSA, vol 6, 75-84.

85 KCAL, James Stuart Collection, file 8, letters from Stuart to his mother, 16 December 1910, 16 May 1911.

86 See the miscellaneous notes made by Stuart on Theophilus Shepstone's career in Appendix 3, JSA, vol 5, 388-403; Stuart's notes of conversations with Lazarus Xaba in May 1910, JSA, vol 6, 321-62; with John Shepstone, Theophilus's brother, in March-April 1912, ibid, 284-316; and with Xubhu kaLuduzo in May 1912, JSA, vol 6, 375-8.

87 KCAL, James Stuart Collection, file 54, item 17, copy of letter from Arthur Shepstone to Rider Haggard, 30 December 1911; Hamilton, Terrific Majesty, 160.

88 KCAL, James Stuart Collection, file 8, letter from Stuart to his mother, 16 May 1911.

89 Socwatsha in JSA, vol 6, 51-60, 87-91.

90 Stuart's correspondence with the publishers is to be found in the Macmillan Archives in the British Library and in Reading University Library.

91 JSA, vol 6, 91-4, also 111-14.

92 N. Cope, To Bind the Nation: Solomon kaDinuzulu and Zulu Nationalism 1913-1933 (Pietermaritzburg: University of Natal Press, 1993), 41. [ Links ]

93 JSA, vol 6, 50-1, 86, 94-7.

94 See for instance his note in KCAL, James Stuart Collection, file 63, item 2(a), 29, dated 23 May 1914.

95 S. Coan, '"When I Was Concerned with Great Men and Great Events": Sir Henry Rider Haggard in Natal', Natalia, 26, 1997, 46-54; [ Links ] Hamilton, Terrific Majesty, 160-1.

96 These were uTulasizwe (1923), uHlangakula (1924), uBaxoxele (1924), uKulumetule (1925) and uVusezakiti (1926), all published by Longmans, Green and Co.

97 Stuart, Zulu Rebellion, 527-37.

98 KCAL, James Stuart Collection, file 42, item 2, 1-3.

99 Ibid, 1. In Terrific Majesty, 141-2, Carolyn Hamilton discusses this memorandum in the context of the early development of Stuart's Idea. It was actually written in the final phase of his recording career, even if its ideological roots go back much earlier.

100 KCAL, James Stuart Collection, file 35, item x, dated 4.7.1919.

101 JSA, vol 6, 102-5.

102 Ibid, 111-14. The anecdote as related by Socwatsha was published by Stuart as an integral part of the account which he prepared for one of his readers, uKulumetule (1925), 7-14. Stuart misleadingly attributes the story to Lutholuni, whereas it was actually related by Socwatsha to Stuart on the basis of information given to him by Lutholuni. In his account of the career of Lutholuni's son, Petros Lamula, Paul la Hausse follows Stuart's attribution: see his Restless Identities: Signatures of Nationalism, Zulu Ethnicity and History in the Lives of Petros Lamula (c. 1881-1948) and Lymon Maling (1889-c. 1936) (Pietermaritzburg: University of Natal Press, 2000), 36.

103 JSA, vol 6, 114-16.

104 See the annotations by Stuart and 'E.S' (Ellen Stuart) in KCAL, James Stuart Collection, file 58, notebook 16, pp 74-6; also under Ntshelele kaGodide, JSA, vol 5, 193.

105 JSA, vol 6, 121; Stuart Collection, file 58, notebook 16, pp 73-4.

106 Ibid, pp 63-71.

107 JSA, vol 6, 123.

108 One of the reasons was possibly so that his two young sons could be educated in England: personal communication from Justin Stuart, one of James's nephews, 1984.

109 La Hausse, Restless Identities, 31, n 86.

110 JSA, vol 6, 167-8.

111 Information on the print runs of the readers can be found in the Longman Archives in the University of Reading Library. Most of the firm's correspondence files were lost when its head office in London was destroyed by bombing during World War II.

112 A. Cope, entry on Malcolm in C. Beyers (ed), Dictionary of South African Biography, vol 4 (Durban: Butterworth for Human Sciences Research Council, 1981), 340-1.

113 La Hausse, Restless Identities, 98-107. See also H. Mokoena, Magema Fuze: The Making of a Kholwa Intellectual (Pietermaritzburg: University of KwaZulu-Natal Press, 2011), [ Links ] ch 4.

114 Daphna Golan, Inventing Shaka: Using History in the Construction of Zulu Nationalism (Boulder: Lynne Rienner, 1994), 59-60.