Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Kronos

versão On-line ISSN 2309-9585

versão impressa ISSN 0259-0190

Kronos vol.41 no.1 Cape Town Nov. 2015

ARTICLES

Thinking with birds: Mary Elizabeth Barber's advocacy for gender equality in ornithology

Tanja Hammel

Department of History, University of Basel

ABSTRACT

This article explores parts of the first South African woman ornithologist's life and work. It concerns itself with the micro-politics of Mary Elizabeth Barber's knowledge of birds from the 1860s to the mid-1880s. Her work provides insight into contemporary scientific practices, particularly the importance of cross-cultural collaboration. I foreground how she cultivated a feminist Darwinism in which birds served as corroborative evidence for female selection and how she negotiated gender equality in her ornithological work. She did so by constructing local birdlife as a space of gender equality. While male ornithologists naturalised and reinvigorated Victorian gender roles in their descriptions and depictions of birds, she debunked them and stressed the absence of gendered spheres in bird life. She emphasised the female and male birds' collaboration and gender equality that she missed in Victorian matrimony, an institution she harshly criticised. Reading her work against the background of her life story shows how her personal experiences as wife and mother as well as her observation of settler society informed her view on birds, and vice versa. Through birds she presented alternative relationships to matrimony. Her protection of insectivorous birds was at the same time an attempt to stress the need for a New Woman, an aspect that has hitherto been overlooked in studies of the transnational anti-plumage movement.

Keywords: Feminist ornithology, sexual selection, gender equality, Cape Colony, matrimony, Mary Elizabeth Barber, visual culture

'One was a military character in a scarlet and black and green uniform' with 'a proud overbearing look', while the other 'must have been in his own country a great King for he wore an imperial purple shot with gold and blue.'1 This is how the South African ornithologist Mary Elizabeth Barber (1818-1899) described two rare African birds she borrowed from the Albany Museum collection in Grahamstown, at the eastern frontier of the Cape Colony in 1868. This is a humorous anthropomorphic, anti-patriarchal and anti-chauvinist description. It is one of many instances in which she did not describe birds as objectively and apolitically as scholars for a long time assumed ornithologists to have done.2*

The French ethnologist Claude Lévi-Strauss explained human fascination with birds by the fact that they 'form a community which is independent of our own but, precisely because of this independence, appears to us like another society, homologous to that in which we live'.3 Birds serve as 'metaphorical human beings'.4 Philosophers and authors have metaphorically used caged birds to voice their concern about women's subordinate role in society. In A Vindication of the Rights of Women (1792) the English writer and philosopher Mary Wollstonecraft, for instance, objected that 'confined then in cages like the feathered race, [women] have nothing to do but to plume themselves, and talk with mock majesty from perch to perch.'5 A hundred years later, the feminist author Olive Schreiner in South Africa saw women still as constrained as Wollstonecraft described. She replied 'to those who argued that women did not want independence' with a rhetorical question that '"If the bird does like its cage and does like its sugar and will not leave it, why keep the door so very carefully shut?"'6

This article concerns itself with one particular case and explores the micro-politics of Barber's knowledge of birds. It contributes to research fields such as critical natural history studies, the social history of ornithology, the history of women in science in South Africa7 and in general, and presents the life and work of the first woman ornithologist in South Africa to appear in the history of ornithology.8 Along with scientific and private correspondence and articles in scientific journals, ornithological illustrations are of particular importance.

My contention is threefold. First, I suggest that Barber did not think about birds in a different way from her male colleagues. Gender essentialist studies - some informed by feminist and ecofeminist theory - have emphasised women's difference. Ecofeminists in the 1990s maintained that men had subordinated women and nature, and that women, with their altruism, had developed sympathy towards nature and engaged in protecting species and in popularising science. It was also claimed that women formulated 'distinctly female traditions in science and nature writing'.9 In contrast, I see women as independent subjects and equal to men, and 'femininity' not as an essence based on biological nature but expressing men's view of women as Other. My case will show that there was no difference in the work of women and men as ornithologists: everyone depended on networks, used the same practices and referred to birds to naturalise or debunk culturally constructed Victorian gender roles. I thus provide an alternative feminist reading. Second, I aim to show that Barber's ornithological work was greatly informed by her private life - an aspect often neglected in studies of naturalists' knowledge production. Third, I analyse the metaphorical use of birds in her descriptions and depictions of birds.

A Brief Introduction to Mary Elizabeth Barber

Mary Elizabeth Barber's contributions to botany, entomology, ornithology, geology and archaeology led to her reception as South Africa's 'most advanced woman of her time'.10 She was born in South Newton, Wiltshire, England, in 1818. In 1820 her parents, Miles Bowker and Anna Maria Mitford, contemplated moving to a British colony. They hoped for social betterment for their eight sons and one daughter11 and were granted land on the eastern frontier of the Cape Colony. At the Kleinemond River, about 13 kilometres east of Port Alfred, they established the farm Tharfield12 in 1822, which was Barber's home for the next 20 years. Without any formal education, she allegedly taught herself to read and write.13 According to two of her brothers, she had always been 'jolly clever' and 'a bit of a bluestocking'.14

She identified with her adopted homeland via local flora15 and began corresponding with the colonial treasurer and Irish botanist William Henry Harvey, author of The Genera of South African Plants (1838). It took almost a year before she revealed herself as a woman. In the meantime he had addressed her as 'M. Bowker Esq.'16 The reason for hiding her real gender was that she wanted to be taken seriously as a botanist and not as one of his 'lady friends' - as he called the women amateur collectors whom he had encouraged to collect for him.17 Barber was ambitious from the very beginning and aimed for a career of her own. In 1849 she was eager to become a paid botanical illustrator as 'in consequence of the Kafir wars this once wealthy family has twice been reduced to the verge of ruin'.18 She never had an official position, but through her correspondence with Harvey and Joseph Dalton Hooker, director of the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew, London, she established herself as a botanist.

From plants her interests naturally shifted to insects that fed on them. In the early 1860s she began corresponding with the entomologist Roland Trimen, who was working in the auditor-general's office in Cape Town and then transferred to the colonial secretary's office before he became Edgar Leopold Layard's successor as curator of the South African Museum in Cape Town in 1872. Over the years Barber contributed to his lepidoptera mimicry studies,19 and in 1878 became the first woman member of the newly established South African Philosophical Society. Trimen praised her 'many-sided mental powers' and 'loving true-heartedness', considering her as 'distinguished for her equanimity, cheerful self-reliance, fine sense of humour, and cool courage'.20

From her interest in butterflies and moths derived her enthusiasm for birds that fed on insects. She corresponded with the ornithologist Edgar Leopold Layard (1824-1900), director of the South African Museum. She was the first person at the Cape he acknowledged in Birds of South Africa (1867) - right after his British colleagues21 -and the only woman he quoted in his work.22 Layard succeeded in installing himself at the beginning of the history of South African ornithology. Ornithologists consider his book 'the first genuine African bird book',23 but many of his collectors have almost fallen into oblivion. By 1903, 16 articles in scientific and popular science journals had been published, as well as a collection of poems by Barber.24 No other woman at the Cape published as many scientific articles and followed and contributed to diverse disciplines. She supported Darwin's theories and defied the stereotype that nineteenth-century science became more male as it became more 'professional.

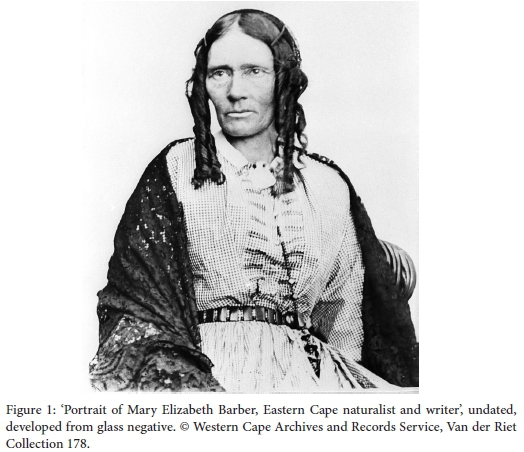

Barber was extremely self-confident. Unlike the Cape Town philologist Lucy Lloyd (1834-1914), who was 'anxious', 'insecure', 'often self-deprecating' and self-effacingly published much of her 'Bushman Work' under the name Wilhelm Bleek or L,25 Barber does not seem to have published anything anonymously or under her initials. There is no indication of self-doubt. The four photographs available show that she presented herself as hard, strict, serious, earnest, distanced and detached. She looks gaunt, emaciated and her sunken face suggests that the experiences of the Sixth, Seventh and presumably also the Eighth Frontier War, the births of her three children, and farming life in Albany had had a deep impact on her. Her hairdo, the sausage curls that framed her face on the side and the back, braided and pinned to her head possibly with a cotton cape for married women's daywear, corresponded to the Victorian ideal of beauty. Her clothes were simple. Her dress was presumably cotton without the fashionable lace decoration and collar, but with the typical Victorian lace cape.

The context of this photograph is unknown. The fact that it was not in her or her descendants' holdings suggests that it was either produced by someone who did not give her a print, or she did not find it worth keeping.

While there does not seem to have been a women's movement at the Cape, women's scope of action enlarged considerably from the 1860s. An English schoolteacher and governess, Beatrice Hicks, who lived in the Eastern Cape from 1894 to 1897, argued that women in the area had limited scope of action. Men far outweighed them and there were hardly any job opportunities. In The Cape As I Found It (1900) she rather exaggeratedly told her readers that the women's movement had triumphed in England but was only at the very beginning in the Cape.26 Since the 1860s, however, a rising number of women fought for their own rights and what was important to them. Lucy Lloyd, for instance, did not agree with the offer of half her predecessor's salary as curator of the Grey Collection at the South African Public Library, but nevertheless reluctantly accepted and held the position from 1875 to 1880. Lloyd passionately fought for her position among conservative intellectuals such as Sir Langham Dale and to further her 'Bushman Work'. She was powerful in the intellectual community in Cape Town, as demonstrated by her objection in the Grey Collection custodian affair and her part in the establishment of the South African Folklore Society.27 Lloyd was one of very few women with a paid position. Like Mary Glanville, the curator of the Albany Museum in Grahamstown at the time, Lloyd was unmarried, had no one to provide for her and received her position after a relative's sudden death. Most women had the status of amateur naturalists. There were a considerable number of nineteenth-century women who were botanists and botanical artists including Katharine Saunders, Arabella Roupell, Margaret Herschel and Alice Pegler, and entomologists such as Bliss White. The time had come when women had more scope of action and could actively shape science and society. Barber differed from her colleagues in that she 'on all occasions made a point of taking the part of [her] sex', as we shall see.28

The next section provides the basis for understanding Barber's ornithological work, introducing her practices and networks of collaboration that allowed her to accumulate information on birds and to become acknowledged as an ornithologist.

'A bird builds with other birds' feathers': Barber's Networks and Practices

Barber had a close relationship with the birds with whom she shared her home. She lived with a Cape starling and a vulture that she kept as pets,29 seeing them 'almost as companions'30 and later consistently called them 'our best friends'.31 But to observe birds in the wild, Barber made herself a part of the landscape. With her horse she rode to birdwatching spots and presumably wore clothes that matched her environment. She must have walked slowly and noiselessly and avoided quick and jerky motions as well as talking. She might have imitated birds' singing and concealed herself by leaning against a tree or pulling a branch down in front of her. When finding a good spot, she probably remained there for several hours. At night she wrote up her notes of the day in one of her notebooks that she later accumulated when writing her letters and papers. But Barber was not independent; in fact her African collaborators enabled her work. 'Intaka yaka ngo-boya bezinye', 'a bird builds its nest with other birds' feathers',32 as the Xhosa poem suggests, perfectly characterises how important collaboration was for Barber's ornithological work.

In Albany, she was in contact with individuals from 'the Kafir and Fingoe tribes',33particularly the 'African employees' on her relatives' farms. Her bead 'necklace' and belt in Figure 1 seem to have been produced by amaXhosa. They suggest her appreciation of beadwork and a closer contact with the local community than previously assumed.34 Some of the 'employees' looked after her children, carried her mail to and from Grahamstown and contributed to her research. In the 1860s, Barber donated stuffed birds to the Albany Museum in Grahamstown and the South African Museum in Cape Town,35 yet she does not seem to have killed or stuffed them herself. 'The boys' stuffed the birds she donated to museums. As she was eager to acknowledge her sons and nephews by name, we can assume that they were stuffed and potentially also collected and prepared by Xhosa and Mfengu collaborators.36

Barber emphasised how settlers and the amaXhosa cooperated and shared their views on birds. In one of her nature tales aimed for publication,37 Barber described how in the spring of 1854 'Gavani a tall strapping Kafir' at the farm Highlands helped 'the boys' (probably Barber's two sons and her nephews and some Xhosa boys) remove sparrow eggs and feathers from the swallows' nests shortly before the swallows returned.38 They did so because both the amaXhosa and the settlers believed that the swallow brought good luck when it built its nest on a house.39 Similarly, the amaXhosa saw starlings as mediators between humans and ancestors, and birds of good omen. Barber learned from the amaXhosa which birds they regarded as 'birds of the house' and never shot birds that took 'their abode with' her family, which allowed her to see 'all their odd ways'.40 This indicates that Barber adapted her practices to those of the amaXhosa and profited from their birding, and from their knowledge of the bird world and their skills while collecting, stuffing, preparing and transporting birds for her.

Barber's collaboration with Africans ceased in Kimberley. Women were a small minority among the 30,000 people on the diamond fields. A traveller to Dutoitspan confirms this in 1871 when remarking that he could not 'recall seeing a single white woman'.41 Olive Schreiner's protagonist Undine in her novel Undine (posthumously published in 1928) discovers in Kimberley that 'she is the victim of a perilous exclusion. Like Africans, she is barred from the white male scramble over the diamonds and the economy of mining capitalism.' Women had no 'right to labour, land and profit' and Undine learns that 'money, public autonomy and sexual power [were] reserved for white men, while her allotted fare [was] dependency and servitude'.42Barber's experiences in Kimberley seem to have been similar; she became painfully aware of women's subordinate position in settler society. She thus concentrated on advocating their rights, and stressed their equality to settler men and their superiority over Africans.

Later, she silenced or obscured African collaborators' share in her work43 as part of a tactic to keep her credibility among urban and metropolitan scientists and to stress her authority as local expert. In her travelogue on her journey to Durban via Cape Town in 1879, Barber only acknowledged her collaborators in criticising them. She misinterpreted their acts of resistance as inability to follow her orders.44 But reading between the lines we see how they enabled her research. 'Matabele boy' Kamel and Klaas from Cape Town drove the wagon, collected specimens, and cooked.45 In an article published in 1880, she distinguishes between her scientific descriptions and the amaXhosa's 'traditionary tales', between written and oral transmission. She belittled tales they had told her several times about an adjutant who followed sportsmen and robbed them of their quarry by alerting vultures and jackals to the carcases. Rather like the honey guide leading bee hunters to hives of wild bees and getting its share as a reward, however, she had to acknowledge that there could be some truth in their observations.46 She thereby showed that she was superior to European travellers who trusted their African collaborators blindly, while she as a local expert could evaluate from her own experiences whether their information was credible.

Writing herself into science, she never referred to vernacular bird names. In Layard's Birds of South Africa (1867), 13 of the 702 listed species' names probably originated in Africa among speakers of West African, Malagasy, Khoesan, Germanic, and Bantu languages. They were taken from François Le Vaillant and Layard's predecessor as curator of the South African Museum, Sir Andrew Smith. Unlike Smith, Layard hesitated to travel and instead relied on what had already been written and on his wide correspondence with ornithologists. He followed Linneaus, who explicitly banned vernacular names as 'barbarous' and used Latin or Greek binominals.47Accordingly, Barber argued that 'barbarous names' had to be 'avoided' by all means.48This made Barber and Layard's understanding of birds diverge from that of their African collaborators. The more they knew and the more self-confident they became, the less they consulted them.

Unlike Layard, whose classification depended on English and European experts, Barber relied on her local network, particularly based on her relatives.49 Her brother Bertram Egerton in his reminiscences recalls having sold stuffed birds to a Prussian apothecary - perhaps Peter Heinrich Pohlmann in Cape Town - in his youth.50 He might have allowed his sister to work with his stuffed birds or could have collected for her. She also borrowed bird skins and stuffed birds from Edwin Atherstone, curator of the ornithological department of the Albany Museum, or observed them in private and museum collections.51 In correspondence, she asked her brother Thomas Holden for 'any strange and peculiar incidents connected with the birds of this country'.52Her two sons provided her with specimens and anecdotes from their expeditions.53Her niece Mary Ellen White and presumably her oldest son Frederick Hugh helped her paint birds.54 Her relatives might also have been members of her reading society of 15 subscribers who circulated scientific articles and books she organised from England.55

To be received as an ornithologist she required recognition from an acknowledged expert. Emil Holub, a medical practitioner, explorer and naturalist born in Czechoslovakia, saw her ornithological illustrations in Kimberley and promised to 'celebrate' them 'all over Europe' and 'blow [her] trumpet at all the scientific so-cieties'.56 Back in Vienna, he gave a lecture on South African avifauna in which he praised Barber's work.57 He spoke with August von Pelzeln, custodian of the Austrian Imperial Collection of birds and mammals and president of the Ornithologischer Verein in Wien, with whom he had closely collaborated. On 10 February 1882, Holub, Trimen and Barber were elected corresponding members of one of the oldest and most prestigious and ornithological societies and were sent a diploma to confirm their membership. In their transactions, the 64-year-old Barber was first mentioned as 'Herr' (Mr) then as 'Fräulein' (Miss) from Cape Town. At that time Barber had been married for 40 years and had never resided in Cape Town, which indicates that the society knew extremely little about her. Barber does not seem to have known more about the society either, given the fact that she could not read their German transactions. She did 'begin to think more of [herself] than [she] used to' and stressed that it was 'more than any of [her] countrymen have done', although she had sent her material on birds and plants to English societies that published her papers in their transactions. This indicates that she was disappointed with her reception in England and was surprised that Austrian ornithologists did not mind 'having ladies amongst them'. She admitted often having 'thought that if [she] had been a man [she] should not have been excluded', which shows that she believed in herself and was afflicted by the exclusion of women from science.58 This is one of few passages in which she openly discussed the exclusion of women. In general, she voiced her concerns through descriptions of birds. Through them she came to accept sexual selection and developed what one might call a feminist Darwinism.

Feminist Darwinism and Birds

Birds play a vital role in the acceptance of natural selection. To Darwin birds were 'the most aesthetic of all animals, excepting of course man'.59 Having learned taxidermy in Edinburgh between February and April 1826 from a freed slave from the Demerara region of Guyana, South America,60 he collected and prepared birds on his voyage on the HMS Beagle. The 12 Galápagos finches that were classified as those of a single genus in 1837 attracted particular attention.61 They were an essential milestone and corroborative evidence for his theory of natural selection. His co-founder of natural selection, Alfred Russell Wallace, had a passion for the birds of paradise, whom he was seeking in his eight-year travels through the Malay Archipelago.62 As an Anglican, Barber had been in inner turmoil for a few years while corresponding with the Irish botanist William Henry Harvey, who was a public opponent of evolutionary theory for years.63 Natural selection challenged the idea of divine providence and the special place of humanity. Barber stated that she was 'a believer' in 'the laws of natural selection' for the first time when corresponding with Layard about helmeted guinea fowls.64 She converted to the theory and combined creation with evolution, such as in the description of the fertilisation of the pistol bush in which she saw 'wonderful evidence of a divine guardianship, a protecting Power, which cares and provides for all'.65Birds were even more important in discussions about sexual selection. The feathers in a peacock's tail made Darwin 'sick',66 as he could not explain its appearance with natural selection. Deep reflections and bird rearing made him come up with the theory of sexual selection first mentioned in 1858 and briefly hinted at in On the Origin of Species (1859).67 He argued that secondary sexual characteristics of male animals such as the peacock's tail had evolved due to female mating preference. Barber was puzzled that the wild guinea fowls had white wing feathers that helped wildcats, owls, hawks, and sportsmen to spot them.68 This could only be a case of sexual selection, in which she was inclined to believe before the publication of Darwin's detailed explanation in The Descent of Man and Selection in Relation to Sex (1871).69

Birds were also important in scientists' denial of natural and sexual selection. The English ornithologist John Gould, for instance, created a (bird) world in which neither natural nor sexual selection was at work. Despite his classification of the Galápagos finches for Darwin, he firmly believed in the fixity of species. He feared that, if it were not for 'the constancy of species', 'ornithology would no longer be a science'.70 He stressed the 'wisdom, power, and the beneficence of [the] Creator'.71While he 'shied away from theoretical controversy', Gould's 'sympathies clearly lay with those among the conservative elite like Richard Owen, who rejected scientific naturalism and its sociopolitical implications'.72

For many of Darwin's male colleagues 'mate choice ... was too extreme an involvement of women in the realm of sexual and/or power relations'.73 While Darwin argued that males evolved 'adaptive weapons of offense and defence for male/male combat' and females developed 'an "aesthetic" sense for choosing between males',74they accepted the adaptive principle in males but they did not agree with female choice.75 Alfred Russell Wallace remained convinced that females would choose 'the most vigorous and energetic',76 not the most beautiful. He felt threatened by the possibility of female intelligence and argued that the ornaments and colours of birds and insects had developed 'in the action of "natural selection", which theory will, I venture to think, be relieved from an abnormal excrescence, and gain additional vitality by the adoption of my view of the subject'.77 Wallace might have been concerned that his theory would be disparaged if sexual selection was widely accepted.

In 1878 Barber harshly attacked Wallace, advocating her own recognition and against men's underestimation of women more generally. She took issue with Wallace's chauvinistic attitude. In a letter to Trimen she wrote:

Did you see a long article in Macmillans Magazine by A.R. Wallace, in which he mentioned the changes in colour which take place in the pupa of Papilio nireus which I sent a description of to Mr Darwin? Then he goes on to say 'these remarkable changes would perhaps not have been credited, had it not been for the previous observations of Mr Wood.' This is rather flattering to one is it not! I was amused.78

Wallace's overlooking Barber's achievements79 as well as giving false credit to the English entomologist John Obadiah Westwood infuriated her - even more so, since she had, in vain, sent specimens to Westwood in the hope that he would publish her 1868 paper on a stone grasshopper's mimicry.80 Additionally, one of her and her brother James Henry Bowker's articles was given to Layard before he left for England but ended up being published under 'Mr Layland',81 which made Barber sensitive to plagiarism and misquotation of her work and motivated her to attack Wallace. These experiences are an example of what Pierre Bourdieu meant when he described science as a 'serious competition' and used metaphors of war to describe the processes within the academic field.82

Barber defended female choice based on males' phenotypes and provided corroborative evidence from Cape fauna, particularly birds.83 After the compulsory peacock example, she showed how male sunbirds and Cape canaries displayed their plumage to females during their 'love meetings' in the 'pairing season. These gatherings cease and the singing considerably diminishes after mates have been chosen. Colour in birds has two functions: it is either indicative or protective. The former helps polygamous males not to lose their female harems, as in the black and yellow finch (commonly called the 'artillery bird') or the long-tailed black finch that loses its long tail feathers in winter. Examples of birds with protective colour are the ostrich, the sunbirds, the wood pigeons and the loeries that perfectly match their environment, particularly the foliage of their favourite plants they subsist on. Female birds that do 'not care for beauty', such as the female domestic fowl, choose 'the strongest and most victorious fighting bird ... no matter what his colours may be'.84 To support her advocacy for women she showed that female birds were autonomous and self-determined; when males displayed their feathers, it happened that females uttered a shrill note as if to say 'I have had enough of this sort of thing' and flew away.85

Barber's accepting female selection for its potential to liberate women needs to be seen in the context of contemporary discourse. Darwin was ambivalent in his description of sexual selection and offered passages to argue for and against gendered spheres. Men could easily replace their explanation from Genesis with that of science and argue for the maintenance of the established gender hierarchy. Darwin's basic assumption was that males played an active role in making a conquest of the females and in rivalry with other males, while the females were passive in copulation and caregivers in rearing the offspring. He thus contrasted males' 'vigour and superior intelligence' with females' 'passive materialism'.86 Darwin argued that there was 'greater intellectual vigour and power of invention in man' as 'the most able men will have succeeded best in defending and providing for themselves, their wives and offspring.'87 He was convinced that the male 'has been the more modified' and has 'stronger passion than the females'. Darwin based his concept of gender differences on his notion of women's 'maternal instincts', their 'greater tenderness and less selfishness'.88 Many men of science such as Francis Galton, Darwin's cousin, the anthropologist known for his studies in eugenics, and the botanist Alphonse de Candolle echoed Darwin's misogynist stance.89

But women found evidence for the opposite. Kimberly Hamlin shows how women in Gilded Age America, particularly after the Fourteenth (1866) and Fifteen Amendments (1870), 'which granted emancipated male slaves, but not women, the right to vote', used natural and sexual selection to advocate for women's rights.90 As Clémence Royer in her French translation had used On the Origin of Species to argue for gender equality, Antoinette Brown Blackwell, the first woman Protestant minister in the US, published the first feminist critique of evolutionary theory in The Sexes Throughout Nature (1875), where she showed how Darwin and Spencer's observations were determined by their belief in male superiority, and argued for a 'Science of Feminine Humanity' that should not only take the experience of women into account but see them as superior to that of 'the wisest men'.91 It is in this transnational context that Barber developed her stance.

Avifauna as a Space for Gender Equality

Avifauna was simultaneously a physical space and mental concept, homologous to and metaphorical of, but in many ways diametrically opposite to, Cape colonial settler society. To construct avifauna as a space of gender equality Barber created what W.J.T. Mitchell, a scholar and theorist of media, visual art, and literature a century later, called an 'imagetext'.92 She combined image and text that augmented one another. Barber could not publish her ornithological illustrations that were thus separately archived, but I reconstruct her intended 'imagetext' and undertake comparative, intervisual and intertextual analysis.

Barber accentuated how male birds shared responsibilities in rearing the young. Ostriches, for instance, perfectly collaborated: the female protected the nest with the eggs and the young during the day and the male took over at night, which explains their brown and black plumage respectively.93 According to Barber, every male sun-bird, Cape canary, yellow finch and red sparrow, in the 'arduous duties' of 'nest building and rearing the young', 'takes his full share, assisting his mate in various ways'. 'The male sunbird takes the young female under his entire care, and the female the young male'.94 She also highlighted instances when female birds executed tasks that humans would consider as belonging to the male persona. The female Cape bristle-necked thrush, for instance, protected her mate and uttered a sound to let him 'know danger is near'.95

In her description of the buff-streaked chat she condemned the males' paternalistic characteristics. She ridiculed his chirping as a means to annoy or amuse his mate. She observed him while 'fond of placing himself on some high projecting rock, and of making himself conspicuous by chirping away in a cheerful voice'. He was 'also fond of opening and shutting his wings, "bowing and scraping,"' and thought 'no end of himself.96 She thereby disapproved of male impertinence, challenged the conceptions of gender personae and scorned the male's behaviour to be chosen by the powerful female. She stressed the power the female bird had over the male.

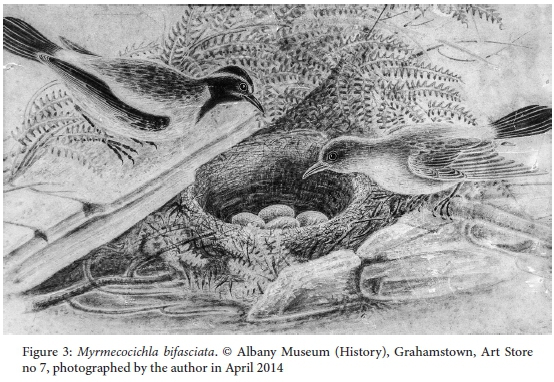

Barber was particularly interested in birds with slight sexual dimorphism. The hardly visible differences between males and females mostly consisted of the female's slightly smaller size, shorter wing, bill or crest, or slight alteration in colour. Of the 11 remaining undated ornithological watercolours97 held in the Art Store at the History Museum, Albany Museum Complex, in Grahamstown, there are three pairs with nest and eggs, two pairs with nests, three pairs, two same-sex birds (one male, one female) and one bird killing another without any reference to their sex.98 In none of them does Barber depict a dominant male, she never centralised male species, but emphasised male-female equality. Focusing on birds with slight sexual dimorphism helped her highlight equality. In five of them - exactly half of the paintings with more than one bird of the same species - she depicts only slight sexual dimorphism. She, for instance, noted that there was 'no perceptible difference between the male and female' Cape bristle-necked thrush (Phyllastrephus capensis).99

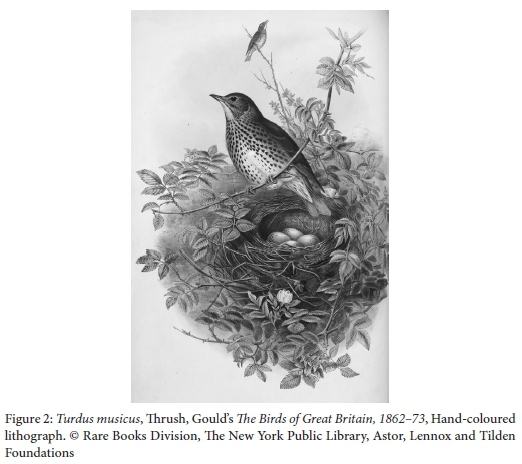

Barber's construction of avifauna as a space of gender equality needs to be seen in contemporary discourse. In the ornithologist John Gould's Birds of Great Britain, bird families were depicted and described in their nests. Nests had rarely been depicted in the plates produced by John James Audubon, the American who was the best-known ornithologist of his time and who set the standards for bird iconography. In the rare cases that birds were part of the picture, Audubon had emphasised the nest rather than the domestic scene of parent birds nurturing their offspring.100 Gould, however, visualised monogamous domesticity and familial harmony.101 He reinvigorated the separate spheres in his illustrations by frequently depicting females near their nests, incubating, protecting, feeding and hovering over their offspring, while males were standing or perching to the side. He naturalised culturally constructed gender stereotypes and family values102 that his subscribers from the conservative gentry welcomed.103

A comparison of one of Gould's and one of Barber's ornithological illustrations is revealing. Figure 2 shows a female and male redwing. The female protects their nest with its four eggs, while the male is at a distance observing them. Figure 3 is Barber's depiction of a female and male buff-streaked chat that was endemic to South Africa and lived on sour grasslands. The male and female are almost at equal height sharing child-rearing duties. This comparison shows the different family lives the two envisaged. While Gould naturalised Victorian gender roles, Barber demystified them in her depictions of birds:

Comparing Barber's illustration to her description discussed above shows that they complemented one another. While she criticised male chauvinistic behaviour in her text, she depicted equal but different birds of both sexes that share the labour of looking after their offspring in her illustration. The imagetext she created allowed her to confirm sexual selection but dismantle the Victorian gender roles that Darwin and his colleagues had projected onto the birds.

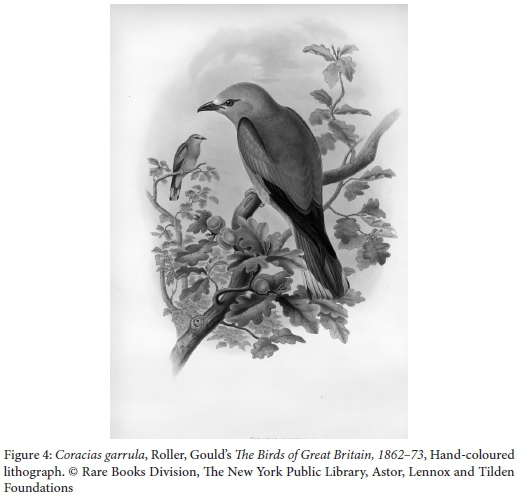

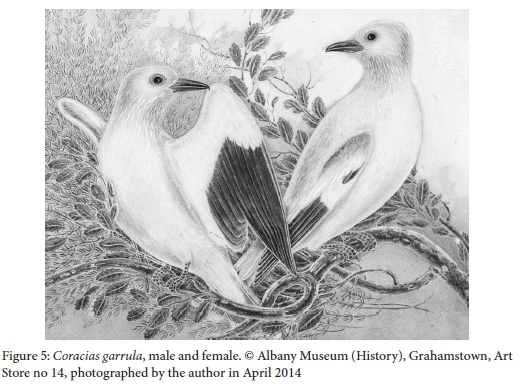

A comparison of Gould's illustration of the male and female European roller (Coracias garrulous) (Fig. 4) with Barber's (Fig. 5) is equally telling. The European roller breeds in the Western, Southern and Central Palaearctic, and winters particularly in dry, wooded, savanna or bushy plains in eastern and southern Africa, which explains its being of interest to both British and South African ornithologists. With its lack of size and weight dimorphism, and its equal colour distribution of turquoise to azure blue plumage, it is a particularly fascinating species.104 The only difference between the sexes is that the female is slightly paler. Comparing Gould and Barber's illustrations we see the relationships they had in mind among human couples. While Gould focused on the male and showed the female in the background, Barber depicted them as facing each other, at eye level, seemingly caring for, looking after one another and functioning in harmony:

Olive Schreiner later agreed with Barber and argued that in the majority of species 'the female form exceeds the male in size and often in predatory nature. Nor are parenting tasks inherently female in nature.'105

In her private life there were discrepancies with regard to gender equality issues. Unlike Hooker and Darwin,106 she did not mention her children in her scientific correspondence and formed a public persona that allowed little insight into her private life. But in a letter to her sister-in-law in 1854 she complained that she felt like 'the old woman that lived in the shoe', as her children took 'up a great deal of [her] precious time and they [had] always got so much to do. She felt that she 'often waste[d] time in talking and playing with them that [she] might employ otherwise'.107 In her unconventional description of her child-rearing activities she criticised the prevailing Aristotelian view that women were passive vessels for the foetus,108 that maternal instincts determined women's character,109 and that maternity and caregiving were women's duty and sole source of fulfilment. While 'the pioneers of the women's movement did not argue so much for the similarity of women to men' but stressed 'women's special skills in regard to children, health care, education, and domestic morality,'110Barber lamented that her husband did not participate in child rearing, which would have given her more time for her scientific pursuits. This was unconventional at a time when the ideal woman was the 'angel in the house' and was supposed to find fulfilment in her domestic sphere.

When invited to become a member of the South African Philosophical Society in 1878, Barber ironically commented that she did not 'see any reason why a lady should not in a quiet way be a member of any scientific society', thereby attacking the contemporary ideal of the 'quiet woman'. Quietness was, according to Barber, everything but 'a blessing in a woman's character'111 and the main cause why women's position in society had remained unaltered for such a long time. With irony she also referred to the common assumption that the 'happiness of our home', as Darwin put it, would not 'greatly suffer' if women were educated.112 She told her male colleagues that the Scottish mathematician and astronomer Mary Fairfax Somerville (1780-1872), the first woman member of the Royal Astronomical Society, combined career with family. Even though the public was only interested in 'her scientific abilities', as Barber assumed, they were even 'surpassed' by her 'qualities' as 'a good wife, and a kind mother'.113 She thereby stressed that women could fulfil what men expected of them but at the same time fulfil their intellectual vocation, and so should be allowed to become equal members of scientific societies.

Against Matrimony

Having argued that Barber used bird relations metaphorically, I would like to draw your attention to her using them as a simile:

Many species of birds, ... choose their mates once for all, and they live together (provided no accident occur to either sex) through the natural term of their lives, in such cases there is but little display on the part of the males of fine feathers, or singing to enchant the females; such birds pursue the even tenor of their way as do married people of the human race, displaying, however, great affection for each other, which is not always the case on the part of human beings.114

Barber compared birds' sexual relations with the behaviour and values of heterosexual human couples and emphasised monogamy, lifelong fidelity and harmony as aspects in avian rather than human relationships.

This quote needs to be seen in the context of Barber's own marriage, a seemingly pragmatic arrangement. On 19 December 1842 she married the analytical chemist Frederick William Barber in what was then called St. George's Church, Grahamstown.115He had arrived in 1839 and was working at the farm Bloemhof near Graaff Reinet as an overseer, superintending the flocks of four to five thousand sheep with their Khoekhoe and Mfengu shepherds. The two probably met at her younger sister Anna Maria's wedding to John Frederick Korsten Atherstone on 5 September 1842. Frederick was there as he was one of the groom's cousins. If so, they married three months after introduction.116 Family rumour has it that he had asked her to join him on the farm and get married there, to which her mother had replied that if she 'was not worth fetching he could leave her where she was.117 Frederick described his wife as a tomboy who would 'rather climb the trackless mountain "all unseen" than figure a quadrille in a heated room ... a plain, simple-minded ... slight and rather tall ... well informed ... girl'.118 A few years after marriage she admitted having spent few 'unhappy hour[s]' in her marriage, but she did not elaborate on what exactly she meant.119 She was a pragmatist arguing that it was one's own fault if one was not happy, 'for the blue sky bends over all'.120

In later years, she hardly saw her husband and by 1879 their relationship had become strained.121 He was away during the Seventh and Eighth Frontier Wars. Renting out the farm Lammermoor on the Zwart Kei River near Queenstown due to financial difficulties, they moved to Highlands, near Grahamstown, where he accomplished little in farming and left his family in 1870, hoping to be more successful in diamond digging. In 1871 he took the family to Kimberley. Unsuccessful at digging, he speculated in a ginger ale factory that consumed his remaining capital. A fire destroyed their belongings in 1878.122 He left the Colony for England to visit his brother Alfred. Alfred, a photographer with his own studio, lived in Totterdown in the outskirts of Bristol. Frederick lived with him, his housekeeper and a lodger, a young widow Elizabeth Blaney. Shortly after his arrival he seems to have fallen in love with her.123 Although he was in London, he failed to bring a botanical illustration to Kew Gardens that his wife had asked him to deliver in person, showing that he had other priorities.124 In 1884 his brother died. The housekeeper took over a house in Stoke View, Fishponds, and Elizabeth Blaney and Frederick moved in with her. Frederick seems to have contemplated divorcing his wife, as he wrote to a friend: 'The French have lately made divorce easily obtainable if after being married 20 years, and the wife is 45, they both desire it. An excellent law in my opinion and one highly calculated to increase the amount of happiness in the world.' He certainly had no wish to return to Kimberley, which he 'dislike[d]... excessively', and was neither 'homesick' nor had any 'craving' to see his family.125 Mary Elizabeth and her sons arrived in England in April 1889, travelled with him through England and Europe and brought him back to the Cape.

There was no reconciliation between the two. He spent the last years of his life away from her. In 1890 Frederick and their son Fred were in Johannesburg 'for some time' and wrote that 'they may be coming down in a month or two' but were 'rather unsettled'.126 Frederick settled down on his own in Grahamstown while Mary stayed with her brother James Henry in Malvern. Frederick died in Grahamstown in 1892.127Even though he and his cousin surgeon and naturalist William Guybone Atherstone are said to have introduced photography to the Cape,128 and he had helped his brother Alfred in his studio in Bristol, there is no photograph of the couple or later family.

These experiences and her observations of other married couples made her question the institution of matrimony in general. To her penfriend, her niece Amenia Barber in England, she wrote that her 22-year-old daughter was 'not yet inclined to sell her liberty', that she had 'set' her 'rather against' matrimony. Announcing that Edwin Atherstone, an ornithologist and half-brother of her husband's cousin William Guybon, had married, she could not resist commenting wryly: 'the fatal knot was tied, from which there is no escape!' She firmly believed in the English satirical magazine Punch's 'Advice to people about to marry - don't.'129 According to Olive Schreiner, women were entirely dependent financially on men as long as they could not work and earn their living; they were their husbands' sex parasites.130 Schreiner was for 'a true marriage' that was 'the most holy, the most organic, the most important sacrament of life' if 'independent of monetary considerations' and argued that 'the woman should be absolutely and entirely monetarily INDEPENDENT OF THE MAN.'131 Barber's concerns with the constraints of women in marriage were detached from economics. As she was against matrimony in general, not only 'untrue marriage', she seems to have taken a more radical stance.

Alternatives to Matrimony

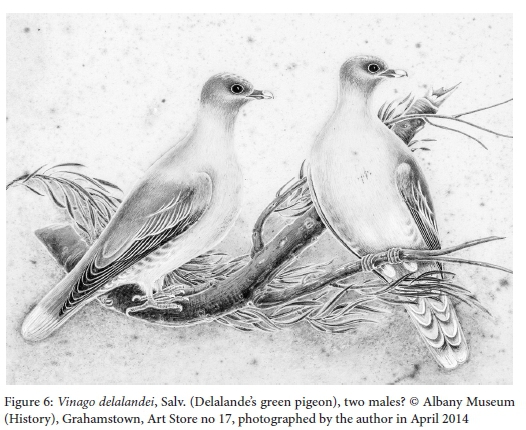

In her bird illustrations of the species Delalande's green pigeon (Vinago delalandei, Salv.) and the South African hoopoe (Upupa africana, Bechst.),132 Barber even took one step further, showing an open-mindedness to alternative relationships:

These illustrations might depict two additional bird species with slight sexual dimorphism. In the case of green pigeons (Fig. 6), ornithologists see the sexes as alike. Selmar Schönland, the botanist and director of the Albany Museum, in 1904 determined them as two males.133 The hoopoes (Fig. 7) might be a female and a male, but as they are rather pale below and have barring on the back, which is typical of the female, it is more likely that Barber depicted two females despite the slightly different postures.134 While Barber's definite depictions of males and females contain nests and show the birds as facing one another, these two watercolours show neither of the two characteristics.

Barber might have reacted to the contemporary pathologising of homosexuality, which was illegal at that time and led to trials like that of the author Oscar Wilde in 1895. This aspect, Barber's criticism of matrimony and her negative comments about men135 and what was perceived as masculine facial features in Figure 1, led people I conversed with to speculations about her being a lesbian. Others suggested she was transgender, probably associating her with James Miranda Stuart Barry, who was born Margaret Ann Bulkley and became a military surgeon in the British Army at the Cape. There is no evidence for either of these assumptions.

The ambiguity of her illustrations leaves viewers with four interpretations that are meaningful to the space of difference between sexes. First, Barber might have again emphasised the slightness of the difference. Second, she might have quietly presented alternative sexual relationships for humans that she would hardly have been able to do in another context. Third, she might also have challenged the heterosexual structuring of bourgeois gender regimes that the English writer and modernist Virginia Woolf later criticised when attacking the idea of only two genders in her essay, A Room of One's Own (1929). Fourth, these might not be depictions of sexual but platonic relationships and an attempt to emphasise friendship over matrimony.

Friendship was important to Barber, and friendship and collaboration among different species of birds is a crucial aspect of her nature tales.136 Particularly in the years when 'Mr Barber [her husband] [was] still in England with the sick brother'137- a rather distanced phrasing that suggests her frustration with the situation - friendship was vital to her. Her children lived their own lives and as a woman she could not live on her own, she had to stay with relatives. She did not want to be a burden to anyone and frequently changed hosts, which resulted in her 'scarcely ever' having 'been a week or fortnight in one place'. At one point she describes herself as 'a vagabond upon the face of the earth.138 With no sign of her husband's return, she 'scarcely' knew what would become of' her.139 In this period she longed to see her penfriends such as Trimen and her niece Amenia.

Pleading for Birds and Women's Rights

Contributing to science did not suffice; Barber took part in settlers' discussion about the timely protection of insectivorous birds in Albany in 1886. Human-induced threatening and extinction of birds had been discussed since 1833, when the dodo was mentioned in the Penny Magazine and became an 'extinction icon'.140 Barber took up these arguments and knew about the efforts to protect birds and get rid of harmful insects in other parts of the British Empire.141 Concerned about threats to the reproduction of the mocking bird, guinea fowl and partridge since the 1870s,142 Barber wrote a paper 'on the protection of birds' that she sent to Trimen for advice. He commented and returned it in the winter of 1885.143

In 1886 the Albany Museum curator Mary Glanville, who was interested in economic entomology, opened a discussion with her paper 'Our Foes and Friends among the Birds' read to the Natural History Society and published in the Grahams Town Journal.144 Glanville blamed those who shot birds particularly for ladies' bonnets and encouraged farmers to prohibit boys from killing birds in their orchards.145She had perhaps been inspired by a book by the Anglo-Australian writer and illustrator Louisa Anne Meredith, Tasmanian Friends and Foes (1880), in which Meredith as an early member of the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals blamed women for the 'war for extermination against the whole bird creation. Millions on millions of lovely, harmless, - ay, more than harmless, useful - happy lives are sacrificed every year to gratify the depraved fancies of vain, idle women.' While Meredith in her fiction used a male character to argue that women 'if they cared to realize our ideal of the sex, would be too humane and gentle to endure the thought that a single sparrow should be destroyed for their pleasure',146 Glanville used no such strand of argumentation.

Barber contributed to the debate with her 'Plea for Insectivorous Birds'147 that echoed new ideas from the Audubon movement in the United States148 and was read in the Eastern Province Literary and Scientific Society in July 1886. The society used her paper to stress that the Natural History Society had similar interests, as Glanville's paper showed, and should therefore become part of the Eastern Province Literary and Scientific Society.149 Barber described how, for the plume trade, male birds in full plumage were shot in the breeding season and as they reared their young, their offspring consequently perished and the female died 'of grief', as non-gregarious birds live in pairs and 'are most affectionate and kind to each other'.150 Every bird that was killed, Barber claimed, allowed the survival of 'tens of thousands' of insects and swarms of locusts and brought deterioration to the environment. Unlike Glanville, who had accused people who shot the birds for women's fashion, Barber blamed women.

The thing I am alluding to is the mistaken fashion of wearing dead birds in hats and bonnets. This fashion leads to misery and cruelty, it has been the means of killing tens of thousands of not only valuable but beautiful and innocent birds, birds which have cheered us with their songs, and rendered our walks and rides interesting, that were at the same time our best friends, labouring on our behalf and daily rendering us most invaluable services, nevertheless amongst those whom I am proud to call my best friends, scattered over a wide extent of this country, I could enumerate many ladies of high character and standing, with warm, generous, and true hearts, who would shrink from allowing their children to do a deed of cruelty, even to the destruction of a fly, nevertheless, thoughtlessly and inadvertently, they will wear in their hats that ghastly emblem of death, a stuffed bird!151

Barber's criticism of the plume trade was a plea for a new woman, no longer only concerned with pleasing men but with the environment and its protection. After its publication in the Grahams Town Journal, the paper circulated in pamphlet form and the Educational Department of the Colony was asked to prepare 'an illustrated sheet for the use of schools, with a description of our useful birds, giving such information respecting our insectivores birds in general'.152 Thus, Barber's ideas on the protection of birds and women's rights circulated among settlers in Albany.

The emancipatory component in actions against the plume trade, a transnational movement, has hitherto been overlooked. The movement in America seems to have attracted most scholarly attention. A few months before the publication of Barber's paper, George Bird Grinnell, a conservationist and editor of the magazine Forest and Stream, had announced the foundation of the Audubon Society in February 1886. The society urged the public to oppose the killing of birds for the millinery trade and appealed to women to serve as leaders in the fight.153 In America, men such as the clergyman Henry Ward Beecher were convinced that 'only women could halt the trade by halting the demand for feathers, and GE Gordon, president of the American Humane Society, demanded that women 'be educated in the crime perpetrated by their feather-wearing sin'.154 Carolyn Merchant, an ecofeminist and historian of science, focused on American activists such as Florence Augusta Merriam Bailey, whom she described as 'conservative in their desire to uphold traditional values and middle-class life styles rooted in these same material interests.'155 She saw them as drawing on 'a trilogy of slogans - conservation of womanhood, the home, and the child'.156 It is true that there are conventionally gendered descriptions, but the stereotypical descriptions here are ironic and are only used to dismantle them. Bailey wrote that 'the timid female' was not very different from the 'lordly male' as, after being 'painfully shy' for a while, 'she was actually making a pass at a usurper.'157Bailey argued further: 'Like other ladies, the little feathered birds have to bear their husbands' names, however inappropriate. What injustice! Here an innocent creature with an olive-green back and yellowish breast has to go about all her days known as the black-throated blue warbler, just because that happens to describe the dress of her spouse!'158

This indicates that it is well worth re-evaluating the movement in America and seeing whether there were attempts like Barber's at the Cape to advocate women's rights by writing pleas for birds.

Conclusion

The article followed different strands to explore how Barber negotiated gender equality in her descriptions and depictions of birds. For the first time, this presents the life and work of the first woman ornithologist in South Africa and broadly contextualises her work and thoughts with occurrences in other parts of the globe, particularly within the British Empire.

The first focus was on her collaboration and practices, showing how essential her African collaborators were for her work and how her network spanned the British imperial context. In her ornithological work, collaboration came before racialism -but she was a woman of her time and a racist, as were many late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century feminists.159 My attempt here was to show that Barber relied and depended on her African collaborators despite her belief in their inferiority.

Birds were her 'companion species'.160 They made her as much as she made them. Birds raised her awareness of women's subordinate role in settler society and became her 'best friends' in advocating gender equality. She addressed people who believed in the human's special position in the chain of being and showed them that, since there was gender equality among birds, that should also be part of humanity if humans were superior.

Reading her ornithological work together with her life story, it is clear that Barber did not believe in 'the traditionally feminine preoccupations of romantic love, marriage and motherhood'161 and challenged the Victorian perception of 'the angel in the house'. Besides letters, she could publicly voice her concerns in her descriptions and depictions of birds, where she saw no gendered division of labour and argued for collaboration and sharing all aspects of life. Barber's insistence on shared labour in child rearing came from her constraint, intellectual frustration and resentment due to her husband's absence in the houshold. As such her conception of avifauna became a space of difference in which bird relations mirrored the relationships of human relationships but embodied what Barber missed in the institution of marriage and in the relationships of married couples she had been observing. When Barber referred to women - whose status she aimed to change - she thought of European or particularly British women at the Cape.

A year before her death, Barber used a bird metaphor in a poem in which she fought for men not to cage women like birds:

"A bird in the hand is worth two in the bush."

"Why did you scream, my little man,

As if you were half slain?"

"This bird I'm holding in my hand

Clawed me and gave me pain.

It is a very savage bird,

And this I'm bound to say,

Although I've fed it night and morn

It tears me every day."

"Let go that little angry bird,

For to this I will stand,

Birds are much better in the bush

Than they are in the hand."162

1 Private archive of the late Gareth Mitford-Barberton, Banbury (BA), M.E. Barber to Menie (Amenia Barber in England), 16 November 1868.

2 I would like to thank Madeleine Gloor, Rebekka Habermas, Priscilla Hall, Patrick Harries, Nancy Jacobs, Stefanie Luginbuehl, Lea Pfaeffli, Christine Winter, the editors and anonymous reviewers for their help in reading and commenting on earlier drafts. I also thank Alan Cohen and Laurel Kriegler for giving me access to their private archives.

3 C. Lévi-Strauss, The Savage Mind (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1966), 204. [ Links ]

4 J.G. Galaty, 'The Maasai Ornithorium: Tropic Flights of Avian Imagination in Africa', Ethnology, 37, 3, 1998, 229. [ Links ]

5 Chapter IV: Observations on the State of Degradation to Which Woman Is Reduced by Various Causes, passage 11: http://www.bartleby.com/144/4.html

6 Cited in A. McClintock, Imperial Leather: Race, Gender and Sexuality in the Colonial Contest (New York and London: Routledge, 1995), 286. [ Links ]

7 There have been many studies on women scholars in recent years, such as P. Skotnes (ed), Claim to the Country: The Archive of Lucy Lloyd and Wilhelm Bleek (Johannesburg and Cape Town: Jacana; Athens: Ohio University Press, 2007); [ Links ] A. Bank, Bushmen in a Victorian World: The Remarkable Story of the Bleek-Lloyd Collection of Bushman Folklore (Cape Town: Double Storey, 2008); [ Links ] A. Bank and L.J. Bank (eds), Inside African Anthropology: Monica Wilson and Her Interpreters (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013). [ Links ]

8 The ornithologist Roy Siegfried in his forthcoming book Levaillants Legacy: A History of South African Ornithology that Print Matters Press announces as 'a remarkable synthesis of the history of the development of the study of birds in South Africa' (http://www.printmatters.co.za) does not mention Mary Barber. Correspondence with the author, May 2015.

9 B.T. Gates, Kindred Nature: Victorian and Edwardian Women Embrace the Living World (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998), 7. [ Links ]

10 M. Gunn and L.E. Codd, 'Barber, Mrs F. W. (Née Mary Elizabeth Bowker) (1818-1899), Botanical Exploration of Southern Africa: An Illustrated History (Cape Town: Balkema for the Botanical Research Institute, 1981), 87. [ Links ]

11 National Archives, Kew (NA), CO48/41, 197, Miles Bowker to Colonial Office, 18 July 1819.

12 C. Thorpe, Tharfield: An Eastern Cape Farm (Port Alfred: Private publication, 1978), 8; [ Links ] B. van Wyk, 'Tribute to an Amateur: Mrs F.W. Barber (Née Mary Elizabeth Bowker)', Plantlife, 6, 1992, 3. [ Links ]

13 Thorpe, Tharfield, 37.

14 History Museum, Albany Museum Complex, Grahamstown (HM), SMD 57 (e), Bertram Egerton Bowker, Reminiscences, 2; A. Cohen, 'Mary Elizabeth Barber: South Africa's First Lady Natural Historian, Archives of Natural History, 27, 2000, 189. [ Links ]

15 Cory Library, Grahamstown (CL), Vol 2, MS 10560 (b), M.E. Barber, 'Wanderings in South Africa by Sea and Land c. 1879', 53; Kew Library, Arts & Archive (KLAA), Directors' Correspondence (DC), Vol 189, Letter 134, M.E. Barber to Joseph Dalton Hooker, 4 March 1888.

16 KLAA, DC, Vol 59, Letter 7, Dr William Guybon Atherstone to Sir William Hooker, 9 January 1849.

17 See W.H. Harvey, 'Introduction', The Genera of South African Plants: Arranged According to the Natural System (Cape Town: Robertson, 1838), v. [ Links ]

18 KLAA, DC, Vol 49, Letter 7, Atherstone to Hooker, 9 January 1849.

19 A. Cohen, 'Roland Trimen and the Merope Harem', Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London, 56, 2, 2002, 205-18. [ Links ]

20 R. Trimen, 'Introduction' in M.E. Barber, The Erythrina Tree and Other Verses, published by her son F.H. Barber for private circulation (London: Rowland Ward, 1898), vii-viii. [ Links ]

21 E.L. Layard, 'Preface', Birds of South Africa: A Descriptive Catalogue... (Cape Town: Juta, 1867), vi. [ Links ]

22 E.L. Layard, 'Further Notes on South-African Ornithology', Ibis, New Series XX, XXXII, 1869, 74, 77, 365, 366, 370, 371, 373-4; Layard, Birds of South Africa, 104-105, 106, 126, 129, 141, 181, 226, 266, 314.

23 P.A.R. Hockey, W.R.J. Dean and P.G. Ryan (eds), Roberts: Birds of Southern Africa (Cape Town: Trustees of the John Voelcker Bird Book Fund, 7th edn, 2005), 10.

24 Cohen, 'Mary Elizabeth Barber', 205.

25 Bank, Bushmen in a Victorian World, 52; N. Bennun, The Broken String: The Last Words of an Extinct People (London: Viking, 2004), 141, 278.

26 F. Fourie, 'A "New Woman" in the Eastern Cape, English in Africa, 22, 2, 1995, 70-88. [ Links ]

27 See for example Bennun, Broken String, 274-7, 298-301, 305-6, 310, 319-20.

28 HM, SM 5501 (46), M.E. Barber, 'A Plea for Insectivorous Birds: A Paper by Mrs F. Barber' (Grahamstown: Richards, Slater, 1886), 12.

29 CL, Vol 1, MS 10560 (a), M.E. Barber, 'Wanderings in South Africa by Sea and Land', 19-20, 35-37.

30 KLAA, DC, Vol 189, Letter 114, M.E. Barber to J.D. Hooker, 9 May 1867, italics mine.

31 HM, SM 5501 (46), M.E. Barber, 'Plea for Insectivorous Birds', 3, 8, 9, 10, 12.

32 J. Henderson Soga, The Ama-Xosa: Life and Customs (Lovedale: Lovedale, 1931), 332.

33 Darwin Correspondence Project, Letter 5745, M.E. Barber to C.R. Darwin, after February 1867, www.darwinproject.ac.uk/entry-5745.

34 R. Shanafelt, 'How Charles Darwin Got Emotional Expression out of South Africa (and the People Who Helped Him)', Comparative Study of Society and History, 45, 4, 2003, 827. [ Links ]

35 Albany Natural History Society', Grahams Town Journal, 22 November 1867 and 27 May 1868.

36 Royal Entomological Society, St Albans (RES), Trimen Correspondence (TC), Box 17, Letter 48, M.E. Barber to R. Trimen, 7 July 1866; HM, SM 5502 (17), Minutes, William Monkhouse Bowker examined by Rev W. Impey (president), J. Ayliff, J.C. Hoole and W.R. Thomson, Thursday, 23 March [1865?]. James Henry Bowker claimed that two families, 'Bechuana refugees, from the valley of the Caledon River' worked for his father: J.H. Bowker, 'Other Days in South Africa, Transactions of the South African Philosophical Society, 1884, 69-70.

37 KLAA, DC, Vol 189, Letter 105. M.E. Barber to J.D. Hooker, 9 March [1869?], about these tales that she wished he would publish for her.

38 Alan Cohen private archive, London (CA), Nature Tales, 'The Swallows', copy of MS.

39 R. Godfrey, Bird-Lore of the Eastern Cape Province, Bantu Studies, Monograph Series no 2, (Johannesburg: Witwatersrand University Press, 1941), 73. [ Links ]

40 Layard, Birds of South Africa, 105.

41 M. Rall, Petticoat Pioneers: The History of the Pioneer Women Who Lived on the Diamond Fields in the Early Years (Kimberley: Kimberley Africana Library, 2002), 15. [ Links ]

42 McClintock, Imperial Leather, 276.

43 Her racialism goes beyond the scope of this article but is discussed at length in T. Hammel, 'Racial Difference in Mary Elizabeth Barber's Knowledge on Insects' in M. Boehi, G. Miescher and M. Ramutsindela (eds), The Politics of Nature and Science in African History (Basel: Basler Afrika Bilbiographien, forthcoming 2016). [ Links ]

44 It remained unpublished and was part of her family archive until, at the height of apartheid, it was published in an unabridged version and donated to the History Museum in Grahamstown and then given to Cory Library. M.E. Barber, 'Wanderings in South Africa: An Account of a Journey from Kimberley to Cape Town and on to Natal', Quarterly Bulletin of the South African Museum, 17, 1962, 39-53, 61-74, 103-16; and 18, 1962, 3-17, 55-68. [ Links ]

45 CL, Vol 1, MS 10560 (a), M.E. Barber, 'Wanderings', for example 1, 3, 9, 15, 25, 31, 32, 34 and 44.

46 M.E. Barber, 'Locusts and Locust Birds', Transactions of the South African Philosophical Society, 3, 1880, 201-2. [ Links ] She had written this paper for 'the general reader' and sent it to the society and 'away', presumably to England. RES, TC, Box 18, Letter 102, M.E. Barber to R. Trimen, 26 November 1877.

47 N. Jacobs, Birders of Africa: History of a Network, ch 3: 'Ornithology Comes to Southern Africa, 1700-1900' (New Haven CT: Yale University Press, forthcoming 2016), MS pp 114, 118, 121, 123, 131, 137. [ Links ]

48 RES, TC, Box 17, Letter 39, M.E. Barber to R. Trimen, 6 September 1864.

49 E.L. Layard, 'Autobiography', partial transcript of the MS at Blacker-Wood library, McGill University, Canada, p 10 of pdf: http://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Edgar_Leopold_Layard_Autobiography.

50 HM, SM 57 (e), B. Bowker, 'Reminiscence (1880), 3.

51 See for example BA, M.E. Barber to Menie (Amenia Barber in England), 16 November 1868.

52 HM, SM 5325 (10), M.E. Barber to Thomas Holden Bowker, 16 June 1862.

53 See E.C. Tabler (ed), Zambesia and Matabeleland in the Seventies: The Narrative of Frederick Hugh Barber 1875 and 1877-1878 and the Journal of Richard Frewin 1877-1878 (London: Chatto & Windus, 1960); [ Links ] I. Mitford-Barberton and V. White, Some Frontier Families: Biographical Sketches of 100 Eastern Province Families Before 1840 (Cape Town and Pretoria: Human & Rousseau, 1968), 36-7; [ Links ] M.E. Barber, 'Locusts and Locust Birds, 218.

54 BA, M.E. Barber to Amenia Barber in England, 16 November 1868; HM, SM 5325 (10), M.E. Barber to T.H. Bowker, 16 June 1862; E.L. Layard, 'VI. Further Notes on South-African Ornithology, Ibis, A Quarterly Journal of Ornithology, V (New Series), XVII, January 1869, 74, 77. [ Links ]

55 HM, SM 3525, M.E. Barber to Julia Bowker (Thomas Holden's wife), 13 May [1855?].

56 RES, TC, Box 18, Letter 115, M.E. Barber to R. Trimen, 9 April 1882.

57 E. Holub, 'Dr. Holubs Vortrag über die Vogelwelt Südafrikas', Mittheilungen des Ornithologischen Vereins in Wien: Blätter für Vogelkunde, Vogel-Schutz und -Pflege, 6, January 1882, 1, 2.

58 RES, TC, Box 18, Letter 115, M.E. Barber to R. Trimen, 9 April 1882.

59 C. Darwin, The Descent of Man and Selection in Relation to Sex, vol 2 (New York: Appleton, 1871), 37. [ Links ]

60 A. Desmond and J. Moore, Darwins Sacred Cause: Race, Slavery and the Quest for Human Origins (London: Penguin, 2010), 18-26. [ Links ]

61 J. Voss, 'Die Finken der Galápagosinseln: Darwins unsichtbarer Handwerker John Gould und die bildende Wissenschaft der Ornithologie' in J. Voss, Darwins Bilder: Ansichten der Evolutionstheorie 1837-1874 (Frankfurt: S. Fischer, 2007), 27-94.

62 For example, A.R. Wallace, 'Narrative of Search after Birds of Paradise', Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London (1862), http://people.wku.edu/charles.smith/wallace/S067.htm.

63 See for example P.J. Bowler, 'Charles Darwin and His Dublin Critics: Samuel Haughton and William Henry Harvey', Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy, 109C, 2009, 409-20. [ Links ]

64 Layard, '519. Numida mitrata' in Birds of South Africa, 266-267.

65 M.E. Barber, 'On the Fertilization and Dissemination of Duvernoia adhatodoides', Journal of the Linnean Society (Botany), 11, (1871), 470-1. [ Links ]

66 Darwin to Asa Gray, 3 April 1860, Darwin Correspondence Project, Letter 2743.

67 C.A.R. Darwin, 'On the Tendency of Species to Form Varieties; and on the Perpetuation of Varieties and Species by Natural Means of Selection', Journal of the Linnean Society (Zoology), 3, 1858, 46-50; [ Links ] Darwin, On the Origin of Species (London: John Murray, 1st edn, 1859), 87-9. [ Links ]

68 Layard, '519. Numida mitrata', 266.

69 Darwin, Descent of Man, vol 1, part 2, Sexual Selection; vol 2, part 2, Sexual Selection Continued.

70 J. Gould, The Birds of Great Britain (London 1862-1873) vol 2, pl 66 reproduced in J. Smith, 'Charles Darwin, John Gould, and the Picturing of Natural Selection', Book Collector, 50, 2001, 57. [ Links ]

71 Quoted in J. Smith, Charles Darwin and Victorian Visual Culture (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006), 100, 103. [ Links ]

72 Smith, 'Charles Darwin, John Gould', 62.

73 P. Young, 'The Politics of Love: Sexual Selection Theory and the Role of the Female', Nexus, 9, 1991, 96-7. [ Links ]

74 Young, 'Politics of Love', 94.

75 For current scientific thinking about this topic, see for example D. Fairbairn, W. Blanckenhorn and T. Székely (eds), Sex, Size and Gender Roles: Evolutionary Studies of Sexual Size Dimorphism (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007); [ Links ] A.I. Houston, T. Székely and J.M. McNamara, 'Conflict over Parental Care', Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 20, 2005, 33-8.

76 A.R. Wallace, 'The Colours of Animals', Macmillans Magazine, 1877, 399, http://people.wku.edu/charles.smith/wallace/S272.htm.

77 Wallace, 'Colours of Animals', 408.

78 RES, TC, Box 18, Letter 101, M.E. Barber to R. Trimen, 2 November 1877.

79 M.E. Barber, 'Notes on the Peculiar Habits and Changes Which Take Place in the Larva and Pupa of Papilionireus', Transactions of the Entomological Society of London, 4, 1874, 519-21.

80 RES, TC, Box 17, Letter 69, M.E. Barber to R. Trimen, 20 November 1869. There are neither correspondence nor specimens at the Hope Entomological Collections, Life Collections, Oxford University Museum of Natural History.

81 Mr Layland, 'The Cave Cannibals of South Africa', Journal of the Ethnological Society of London, 1, 1, 1869, 76-80. RES, TC, Box 18, Letter 84, M.E. Barber to R. Trimen, 13 April 1871.

82 P. Bourdieu, Vom Gebrauch der Wissenschaft: Für eine klinische Soziologie des wissenschaftlichen Feldes (Konstanz: UVK, 1998). He calls the scientific field 'an object to battle' (Kampfgegenstand) and his own discipline, sociology, 'martial arts' (Kampfsport, 25) in which people had to 'thematically eye out' (thematisch ausstechen) opponents (28).

83 She aimed to publish the paper in England, as she believed that many in the Cape Colony had not read Wallace's paper. Four months later, she sent the paper to Roland Trimen in Cape Town, the entomologist and curator of the South African Museum and co-founder of the South African Philosophical Society. RES, TC, Box 18, Letter 102, M.E. Barber to R. Trimen, 26 November 1878.

84 M.E. Barber, 'On the Peculiar Colours of Animals in Relation to Habits of Life', Transactions of the South African Philosophical Society, 4, 1878, 29-35.

85 Ibid, 29-30.

86 Young, 'Politics of Love', 96-7.

87 Darwin, Descent of Man, vol 2, 382-3.

88 Ibid, 256.

89 See B.C. Schär, 'Evolution, Geschlecht und Rasse: Darwins Origin of Species in Clémence Royer's Übersetzung' in P. Kupper and B.C. Schär (eds), Die Naturforschenden: Auf der Suche nach Wissen über die Schweiz und die Welt, 1800-2015 (Baden: Hier und Jetzt, 2015), 78.

90 K.A. Hamlin, From Eve to Evolution: Darwin, Science, and Women's Rights in Gilded Age America (Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 2014), 46.

91 Ibid, 57, 61, 63.

92 See for example W.J.T. Mitchell, Iconology: Image, Text, Ideology (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1986), 43; W.J.T. Mitchell, Picture Theory (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1994), 5, 95. RES, TC, Box 18, Letter 109, M.E. Barber to R. Trimen, 27 November 1878.

93 M.E. Barber, 'Peculiar Colours of Animals', 34-5.

94 Ibid, 30.

95 Layard, Birds of South Africa, 105.

96 M.E. Barber to E.L. Layard, 22 June 1865, quoted ibid, 240-1.

97 As she showed some to Emil Holub in Kimberley, she must have either painted them there in the 1870s or before.

98 For a list of her ornithological illustrations see S. Schönland, 'Biography of the Late Mrs. F.W. Barber, and a List of Her Paintings in the Albany Museum, Records of the Albany Museum, 1, 2, 1904, 101-2.

99 Layard, Birds of South Africa, 105.

100 Smith, 'John Gould, Charles Darwin', 58.

101 See J. Smith, 'Gender, Royalty, and Sexuality in John Gould's Birds of Australia, Victorian Literature and Culture, 35, 2, 2007, 569-87.

102 J. Smith, 'Picturing Sexual Selection: Gender and Evolution of Ornithological Illustration in Charles Darwin's Descent of Man' in A.B. Shteir and B.V. Lightman (eds), Figuring It Out: Science, Gender, and Visual Culture (Lebanon NH: Darmouth College Press, 2006), 89. For feminist critics on the subject, see for example G. Beer, 'Descent and Sexual Selection: Women in Narrative' in her Darwins Plots: Evolutionary Narrative in Darwin, George Eliot, and Nineteenth-Century Fiction (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2nd edn, 2000), ch 7; R. Jann, 'Darwin and the Anthropologists: Sexual Selection and Its Discontents', Victorian Studies, 37, 1994, 287-306; E. Richards, 'Darwin and the Descent of Woman' in D. Oldroyd and I. Langham (eds), The Wider Domain of Evolutionary Thought (Dordrecht: Reidel, 1983), 57-111; C. Eagle Russett, Sexual Science: The Victorian Construction of Womanhood (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1989); R.B. Yeazell, Fictions of Modesty: Women and Courtship in the English Novel (Chicago: Chicago University Press 1991).

103 Smith, 'Picturing Sexual Selection', 88.

104 C.H. Fry and K. Fry, Kingfishers, Bee-Eaters & Rollers (Princeton: Princeton University Press 1999), 100-101, 298-300. They have been 'near threatened' since 2005: http://www.birdlife.org/datazone/species/factsheet/22682860.

105 McClintock, Imperial Leather, 291.

106 See for example J. Endersby, 'Sympathetic Science: Charles Darwin, Joseph Hooker and the Passions of Victorian Naturalists', Victorian Studies, 51, 2, 2009, 299-320.

107 HM, SM 5325 (2), M.E. Barber to Mrs Holden Bowker, 13 May [1854?].

108 See N.L. Paxton, George Eliot and Herbert Spencer: Feminism, Evolutionism, and the Reconstruction of Gender (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1991), 23.

109 See George Romanes, Darwin's friend, in 'Mental Differences of Men and Women', July 1887, quoted in Hamlin, From Eve to Evolution, 71.

110 M. Vicinus (ed), 'Introduction', A Widening Sphere: Changing Roles of Victorian Women (Bloomington and London: Indiana University Press, 1977), x.

111 RES, TC, Box 18, Letter 114, M.E. Barber to R. Trimen, 30 March 1882.

112 Darwin Correspondence Project, Letter 13607, Darwin to Caroline A. Kennard, 9 January 1882.

113 RES, TC, Box 18, Letter 105, M.E. Barber to R. Trimen, 11 April 1878.

114 M.E. Barber, 'Peculiar Colours of Animals', 30-1. She had written the paper in 'such a dull uninteresting old place' and asked Trimen to help with classification: RES, TC, Box 18, Letter 101, M.E. Barber to R. Trimen, 2 November 1877.

115 Marriage notice in Grahams Town Journal, 22 December 1842.

116 AC, A. Cohen, 'A Wedding and Two Wars' in MS 'In a Quiet Way', 26.

117 I. Mitford-Barberton, The Barbers of the Peak: A History of the Barber, Atherstone, and Bowker Families (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1934), 72. [ Links ]

118 HM, SMD 739, F.W. Barber to Rev Henry Barber, 3 March 1844.

119 HM, SM 5325 (18), M.E. Barber to Mary Anne Bowker, 15 November 1847.

120 RES, TC, Box 17, Letter 36.1, M.E. Barber to R. Trimen, 22 March 1864.

121 BA, Letter, Julia Eliza Bowker to her daughter Mary Layard Bokwer, 4 January 1879.

122 RES, TC, Box 18, Letter 107, M.E. Barber to R. Trimen, 17 August 1878.

123 BA, Letters, F.W. Barber to Alfred Barber, 14, 22, 25, 27 and 29 June 1879.

124 KLAA, DC, Vol 189, Letter 100, F.W. Barber to JD Hooker, 23 December 1879.

125 F.W. Barber to George Hull, quoted in Cohen, 'In a Quiet Way', 5. Underlined in original.

126 Robert Mitford Bowker to his daughter Anne Pringle, 16 February 1890, quoted in full in I. Mitford-Barberton, The Bowkers of Tharfield (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1952), 251-2. [ Links ]