Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Kronos

On-line version ISSN 2309-9585

Print version ISSN 0259-0190

Kronos vol.40 n.1 Cape Town Nov. 2014

ARTICLES

Papering over the cracks: An ethnography of land title in the Eastern Cape

Rosalie Kingwill

Plaas, University of the Western Cape

ABSTRACT

The article addresses the dualistic legal paradigm prevalent in South Africa's approach to recognising rights in land. The system of title is characterised by precise and quantifiable mathematical formulae formalised through paper records that convey proprietary powers to registered owners. This view is contrasted with the characteristics of land tenure among African families with freehold title in the Eastern Cape who trace their relationship to their land to forebears who acquired title in the nineteenth century. The findings show that relationships reminiscent of 'customary' concepts of the family are not extinguished when title is issued. The land is viewed as family property held by unilineal descent groups symbolised by the family name. This conception diverges considerably from the formal, legal notion of land title as embodied in common law, and from rules of inheritance in official customary law. African freeholders' source of legitimation of successive rights in land is not the 'law' but locally understood norms framed within identifiable parameters that sanction socially acceptable practices. The conclusion raises broader questions about the paradigm that informs South African law reform in a range of tenure contexts, suggesting that current policies are poorly aligned with the social realities on the ground.

The result of our system of registration [in South Africa] is that in the Deeds Office and in the Surveyor-General's Department one has a complete picture of the land of this country in miniature, notifying one of the ownership of, and of real rights in, every piece of land in the Republic. - Wille's Principles of South African Law1

Registering is just a formality. Underneath the formality, the family works out its own arrangements. The land will never get sold. That's the convention. There is no way one of them could sell. - Bongani Makuzeni2

We don't do it according to the law, we just do it alone. - Mandla Makuzeni3

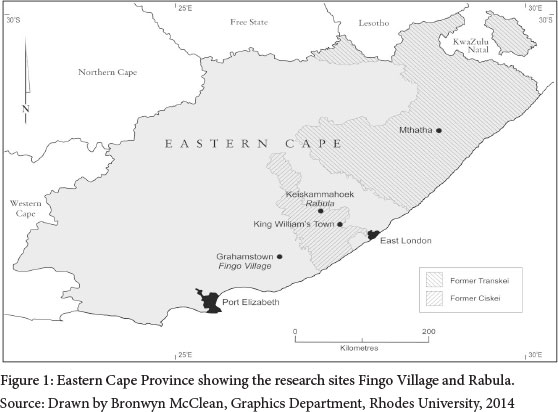

This article4 examines the outcomes of the imposition of European paper systems of registration of freehold land ownership on African ideas and practices about land access and control. The evidence is drawn from two African freehold settlements with long-held title in the Eastern Cape, one in an urban setting and the other in a rural one. These sites were among a handful of others where freehold tenure survived the turbulent journey towards racially segregated systems of land access and control, albeit in an adapted form. European concepts did not replace African social systems and ideas about property, but nevertheless affected the parameters within which these values were expressed.

We trace the evolution and construction of the formal system of title, in the shadows of which African freeholders adapted an alternative normative approach drawing on 'customary' concepts of family and ownership. The findings raise questions about the reach of legal regimes that attempt to legislate social change from above, and how tensions are generated by practices that resist them from below. The disjunc-ture between the two levels is revealed in contrasting perspectives between African and western ideas of holding and transmitting land, which turn on different modes of framing social and kinship relationships. These differences result in contrasting interpretations of the significance of the paper title. The monopolistic devices used by the state to transform tenure relationships have not obliterated African ideas. The dynamic was never a simple one-way relationship over which Africans had no control. African ideas have made an impact on private ownership and paper systems in curious ways.

African social systems do not readily yield to naming on title deeds and formal subdivision, or to the rules of the market.5 A variety of paper systems across the tenure landscape compete with locally recognised property arrangements that hinge on social relationships and networks. The divergent approaches raise questions about law reform that attempts to redress historic imbalances in land ownership.

Historical Context of Freehold Title

The legal technicalities of land title in South Africa are among the most exacting on the globe. The accretion of both Dutch and English law at the Cape resulted in a unique hybrid of Roman, Germanic and English legal principles concerning 'ownership' of land. Thrown into this mix was the colonial and later apartheid imperative of 'non-ownership' of African land to emphasise white hegemony. The comparatively large European settler population in colonial South Africa commanded an unusually high degree of legal, physical, spatial and governance distinctions between white and black land tenure. The result was a cadastral system of land surveying dependent on precise mathematical formulations of property boundaries, reinforced by physical boundaries such as fencing, backed by fencing laws and a unique system of registration of deeds. The latter in turn revolved around European concepts of what constituted the social unit of the family for the purposes of recognising legitimate owners and their rights to succession and inheritance, which completed the picture of property regulation, conventionally depicted as the 'formal system'.6

A window opened during the mid-nineteenth century for the brief and tentative appearance of assimilationist land policies within the precincts of the Cape Colony, the area which, before its boundaries were extended to the east to incorporate what later became the Ciskei, Border and Transkei, is referred to by historians as the 'old Cape'.7 The desire among early colonial officialdom to 'individualise' land holding among Africans was fanned by the fanaticism of Sir George Grey, governor of the Cape from 1854 to 1861, who arrived fresh from governing New Zealand with new ideas about subjugating indigenous people to western political ideas, including land ownership. He was convinced of the superiority of European culture and fervently believed that western law, if applied systematically, would extinguish African systems of authority and land use.8

For the influential day-to-day administrators it was enough to grant land to incorporated Africans under a modified version of the Dutch quitrent system.9 Quitrent tenure was adapted to African use by surveying land into diminutive plots laid out in village grids10 with separate arable, residential and grazing allotments. The new spatial and administrative measures were designed to limit the authority of chiefs and facilitate individual identification and taxation through paper titles linked to surveyed land parcels. This spatial model, without title, was later adapted to 'communal' tenure arrangements under magistrates and headmen. Compact village layouts comprising compressed, undersized and segmented plots ran counter to traditional patterns of socio-spatial land use, where (as we understand it) Africans along the eastern seaboard exploited the land around their homestead as an integrated unit for residential, arable and pastoral uses. Ecological constraints were accommodated by transhumance patterns or cattle posts. Homesteads were linked through neighbourhood ties formerly characterised by extended kinship and clanship networks.11

Sir George Grey went further. He introduced special measures whereby Africans could purchase land in freehold, a system only beginning to be applied to European landholdings in a systematic fashion at that time. Unlike the grant system, freehold held the promise of access to larger extents of land with less official surveillance.12 Grey's freehold did not restrict sizes; conversely a minimum size of 8 (later 4) ha was stipulated.13

Land surveying was undergoing phenomenal transformation in the direction of precision and sophistication, tapping into global scientific advancements in the field of spatial measurement through astronomy.14 The heady days of scientific developments in the west overlapped with some tenets of Cape liberalism, which imagined that the global appeal of western values associated with 'civilisation' would replace customary norms and values. The availability of new instruments and techniques for spatial measurement at the Cape15 resulted in the systematic division of much of the Xhosa-occupied territory into farms for European settlement schemes as well as chopping up incorporated African settlements into small village plots. The theodolite, an instrument that could measure large areas of space by means of angles in the horizontal and vertical planes (a method known as triangulation) revolutionised the scale and precision of surveying.16 After 1857 theodolites were compulsory in the Cape for recording numerical data to replace graphical data on survey diagrams.17 The dynamism of these developments resulted in the growth of what was to become a robust and influential private land surveying industry in South Africa, adding to the professionalism of South Africa's property system.

Over a relatively short space of time, freehold became the dominant tenure for white settlers, bolstered by regulations designed to stamp out the legacies of unregulated and indulgent land access by poorer whites who viewed land in terms of family entitlement.18 Following the mineral and agricultural revolution, the laws governing spatial demarcation and inheritance of land were geared towards transforming land into a capital asset to prod the development of commercial agriculture. These developments affected whites as well as blacks. Large numbers of 'poor whites' were displaced from the land as a result of the new dispensation, their 'roving' and 'pasto-ralist' tendencies frowned on as primitive and uncivilised.19 A criterion for emergent western civilised values was the switch from pastoralism to agriculture. For the white rural sector, this thinking led to policies that encouraged agrarian accumulation. For blacks, however, the same thinking was used to justify curtailment of grazing land through close village settlements and small arable plots, which simultaneously levered migrant labour to serve the emergent capitalist economy. The result of these dual racial policies was a parallel process where the dominance of freehold tenure for whites20 was matched by the increasing inaccessibility of freehold for Africans. State-backed class formation for whites was matched by brakes on class formation among blacks.21

Thus only a small handful of Africans acquired land in freehold, and many lost their titles through foreclosure over time. The laws governing inheritance of African land held by title were, moreover, later amended in line with growing emphasis on 'customary law', a process to which conservative elements in African society contrib-uted.22 For title holders there were escape routes through the common law, but the nuances were not readily understood at local or household level, and even officials had a hard time navigating through the growing labyrinth of regulation. The intricacies of land law divided vertically across race lines and horizontally along the customary/common law distinction, with marriage a key determinant of the latter. Thus, for example, the property of a deceased African married in community of property or with an ante nuptial contract (that is, by civil law or Christian rites) 'shall devolve as if he had been a European'.23

In short, the earlier legacies of title for Africans lost support as a policy choice by the Union government. Existing titles were merely to be tolerated within a growing contemporary vision by colonial officialdom in the early twentieth century that Africans were better suited to tenure in collectivities under truncated customary arrangements dubbed 'communal' tenure. These policies found justification in evidence led in government commissions that, inter alia, investigated native 'law and custom'.

The findings included a negative appraisal of African responses to title.24 The officially constructed communal tenure systems were to be regulated by administrative rather than parliamentary oversight, which meant that all matters concerning native administration were both conceptualised and enforced by the executive branch of government under the guidance of the reinvigorated Native Affairs Department.25 The Native Administration Act of 1927 created a structure of African governance by proclamation. The proclamations and their regulations were drawn up by white officials of the Native Affairs Department without recourse to the legislature, except for mere rubber-stamping.

African freehold did not escape the racial framework of 'native administration', and over time African freehold settlements were absorbed into racial land zones termed 'locations', 'homelands', 'bantustans' and 'group areas'. The increasing stress on racial difference in native land policies meant that African freehold' never functioned on a level playing field with 'white freehold', but neither was it entirely extinguished. Rather, African title was pushed into the interstices of native customary law and the common law, neither of which captured or reflected the practices adopted by African freeholders discussed below.

The Legal Implications of Registration

Legibility implies a viewer whose place is central and whose vision is synoptic. State simplifications ... are designed to provide authorities with a schematic view of their society, a view not afforded to those without authority... [A]uthorities enjoy a quasi-monopolistic picture of selected aspects of the whole society.26

The South African land titling system is known as 'deeds registration', one of its distinctions being the emphasis on registration of fresh deeds every time a land transfer is effected. The title represents a record of a publicised contract between two parties,27 so that registration is regarded as a 'specialised form of delivery'.28 The legalities lie in the registration process rather than the paper title itself.29 From 1813 the British authorities set about improving the somewhat haphazard Roman-Dutch system of registration of real rights by making survey and registration compulsory,30 thus establishing a more robust cadastral system. The first offices of the surveyor-general and deeds registry were established in Cape Town in 1828, taking over duties previously undertaken by the commissioners in the governor's office.31

Deeds systems are also known as 'negative' systems by virtue of the definition that the state does not directly guarantee title. In South Africa the state provides substantive backup in statutory form and in public provision and staffing of deeds offices, which introduces strong state ( 'positive') oversight, and is thus a home-grown hybrid system.32 The most important land administration functions are, however, carried out by professionals - land surveyors, legal conveyancers and planners. This contributes to the professional quality of South Africa's property system, where significant land management functions are in the hands of the private sector.

The mainstream property system implies one-to-one relationships between property owners and property objects, called 'things' in law.33 Property law in South Africa moved away from flexible English models in the direction of strong emphasis on singular ownership. What this means in practice is that the model cannot accommodate fragmented ownership or co-incidental rights by multiple parties in the same parcel, though such nuances are in theory tolerable in western models.34 The latter was an option that the South African legal system consciously chose to reject.35 Instead, different levels of rights are clearly distinguished and registered; for example, a right of way over someone's land has to be surveyed and registered, not simply regulated through common-law rules; and boundaries must be mathematically surveyed, as opposed to reliance on geographic or natural boundaries like hedges or rivers. Moreover, rights of inheritance where there is no will36 must be meticulously quantified according to succession rules, nominating particular individuals in the family as heirs,37 and each transfer and name must be registered. This context is relevant to the discussion that follows in that one could characterise the bundle of rights38 held by title in South Africa as a tightly bound rope of ownership.39 This model within the private ownership paradigm added a sharper edge to the interface between the western system and African systems, and increased the levels of institutional tension between African and western models when African freeholders attempted to adapt customary norms to the paper title system.

The remainder of the article examines the trajectory of title among African freeholders as a prism through which actually existing trends in tenure practices may be discerned. Legal recognition of the heritability of freehold rights is key to the processes and practices by which African freehold title survived. In contrast, the lack of legal recognition of heritability of communal tenure rights (as conceived by officialdom) is an important marker of distinction between state grants (permits) and private property rights. Heritability and succession move to centre stage for purposes of evaluating the trajectory of African freehold titles. This perspective contrasts with conventional definitions that oppose title and communal tenure with reference to a binary distinction between individual and collective rights.

Fingo Village and Rabula

The freehold land tenure systems in the two research sites, Fingo Village and Rabula, were the direct result of Sir George Grey's tenure as governor of the Cape and high commissioner of South Africa. In his latter capacity he had control of British Kaffraria, a separate colony ruled directly from Britain, covering much of what later emerged as the Ciskei 'homeland'. He was a fanatical exponent of the virtues of European civilisation and the positive impact that imperial western values could make through public works and facilities (such as roads, schools and hospitals), new political and tenure systems and the forceful suppression of African customary values.40 One facet of these ideas was modelling a means by which Africans could purchase land in freehold, albeit at inflated prices substantially higher than the prices whites paid and were prepared to pay.41 Wealthier Africans availed themselves of the opportunity with alacrity, raising the purchase price through the sale of cattle.42

Those who acquired title in Fingo Village and Rabula did so in terms of Grey's freehold option during the decade spanning the mid-1850s to mid-1860s. The first titleholders were culturally homogenous, though their geo-political contexts were somewhat different. Fingo Village is part of Grahamstown, whereas Rabula is rural, situated in Keiskammahoek district of the former Ciskei. Urbanised and rural Africans faced different challenges regarding access to resources and employment, and there was greater socio-spatial cohesion among the rural families. In addition, the villages were situated in two distinct colonial precincts. Fingo Village had been in the old Cape Colony, whereas the village of Rabula was in British Kaffraria. While the Cape followed the common law for white and black, British Kaffraria was ruled by force, edict, experiment and invention, one historian labelling it 'martial law'43 as far as the amaXhosa were concerned.

The titleholders were not regarded as Xhosa people at the time (though their spoken languages were similar), being identified as 'Fingo' by the British, an anglicisation of 'Mfengu', meaning supplicants. Most, if not all, the early titleholders in these two research sites shared the 'Fingo' label and a common history of displacement as temporary refugees among far-flung corners of Xhosa territory. The neologism 'Fingo' denotes a category of displaced people identified and so-named by the coloniser, and was not an indigenous name of an ethnic group or tribe. The historiography of the ama-Mfengu is contested44 and not pursued further save to mention that the amaMfengu entered a political relationship of strategic alliance with the British and fought alongside British soldiers against the Xhosa resisters. They responded positively to many of the opportunities on offer, such as education, the franchise and private land tenure.

An important result of the alliance was that amaMfengu received substantial grants of the land appropriated by the Crown. The general lines of settlement were small plots pegged in rural villages, which were strenuously resisted at first, made worse by their initial location in unsafe and infertile areas.45 Those who bought land were anxious to secure more and higher quality land on better terms. African claimants to land in Rabula chose freehold46 despite the extra costs of land and survey. Most properties were surveyed early in the 1860s, though purchases continued for some decades and included a small number of white buyers of German extraction. There was great variation in size, from 4 to 40 ha averaging at 16 ha. By 1906 there were 164 properties, which by then had been affected by a small number of transfers and subdivisions, mainly among the white owners.47 The white-owned properties were expropriated by the South African Development Trust during the 1950s and divided into small plots and granted under state-controlled tenure arrangements to occupiers ('squatters') living on Rabula's commonage, with a further redistribution of residential plots in the 1970s.48 Thus two systems of tenure operated in Rabula, but the freeholders considered themselves socially elevated as landowners by virtue of their status as notenga, 'those who bought'.49

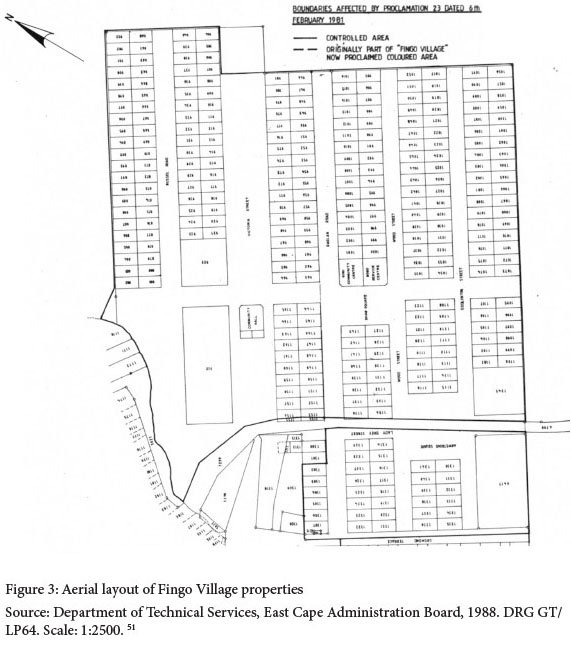

In Fingo Village 318 titles were issued following the survey in 1856. The plots were a uniform size of 1,000 sq m laid out in a grid. The beneficiaries paid for the survey but not for the land since they were the existing occupants. The titling was an early example of urban formalisation after much lobbying by municipal officials who wished to 'clean up' the informal settlement.50 The proposal was finally approved by Grey and his signature appears on their title deeds. To this day the titleholders cite their benefactor as Queen Victoria, whose insignia appears atop their title deeds. The association with a monarch would appear to lend a sovereign dignity to their title, which a connection to the controversial Grey would not.

The plots in both settlements were thus substantially larger than the conventional plot sizes for African allocation in both rural and urban settings.52

Oral testimony and documentary records traced over time reveal that from the first issue of title to the present the registration record of African freeholders diverged considerably from the legal requirements of title. The registers invariably reflected the name of an antecedent, in some cases the first titleholder, rather than the present owner, since transfers were generally not registered. This remains the trend today.53

The deviation from the legal norms was reported in various state commissions54 and regarded as sufficiently serious to warrant special administrative redress to shoehorn African title into the legal mould. The option of expropriating 'native titles' was toyed with by local council officials in Fingo Village, but rejected by the Department of Native Affairs.55 The Native Administration Act of 1927 contained special provisions to tackle the problem on many fronts, key of which was the creation of segregated deeds registries in the 'homelands', already a feature of the Transkeian system and hailed as a salutary model.56 As a result, the King William's Town deeds registry established during Grey's tenure, the early home of the Rabula records, was split between two repositories. The 'black' registers were moved to the Ciskeian administration headquarters.57

A second intervention provided for the appointment of commissioners of titles (who could be 'native commissioners' in their judicial capacity) in terms of section 8 of the Native Administration Act. Commissioners were empowered to systematically 'update' black titles by notice in the Government Gazette. Their task was to identify and record the 'true' owner of each parcel and they were also given special powers to convey the title to the identified owner, although conveyancing was normally reserved for the private profession.58 Commissioners still exercise these powers in terms of new legislation to the same effect, enacted in 1991.59 The new system allowed for administrative short cuts60 not legally tolerable in the mainstream system. It is necessary to pause here to underline the importance of keeping records up to date. As mentioned, each transfer (including inheritance without a will) results in a fresh deed, the corollary being that failure to correctly reflect the name of a transferee effectively nullifies the validity of the title. The consequences are grave indeed.

Both documentary and oral evidence supports the contention that property seldom gets registered when it changes hands from one generation to the next. Sales of property, too, tend to be informally transacted and witnessed. Private property transfers are often not conveyed by private conveyancers as required by law, and are thus only legally conveyed when commissioners adjudicate title. In Rabula, land is informally subdivided among siblings without formal surveys. These are not registered but recorded in memory through local witnessing, and easily adaptable to changing generational circumstances. Wills are almost universally avoided. The 'language' of wills is becoming more common in recent times,61 but seldom translated into action.

The lack of updated ownership records has serious consequences for the land information system that informs registration of title, since the latter comprises interlocking parts which I liken to a '3-D' cadastre. Each of these aspects must be maintained in order to uphold the coherence of the system: (a) The core unit is a discrete measured area that must be surveyed to statutory standards within an accuracy range of centimetres; (b) Registered owners have real rights which implies much autonomy over property, though users have some legal protections; (c) Registered owners have fiscal obligations - property registers are linked to records for income tax and billing for servicing; (d) Ownership is linked to rules of inheritance and succession. Transactions set off a domino effect. Like a train moving through stations, you cannot get to the destination of ownership until there has been an exchange of information at a number of stations along the way. 62

In the case of Fingo Village and Rabula, some of these interconnecting sequences have been interrupted; for example, in Fingo Village there are obstacles to recovering municipal bills from the living, because the property is owned by the dead! It is not unusual for accumulated arrears in municipal charges to reach five-digit figures, which remain recorded in property records and obstruct future transactions. Thus the entire system of registration has been thrown into disarray.

Title commissioners were appointed to update lapsed titles throughout Fingo Village and Rabula at various times. There have been three commissions in Fingo Village, the timing indicating they have followed generational cycles since the 1940s, with a fourth advertised in 2014 as forthcoming. One commission adjusted titles in Rabula during the 1950s and 1960s, 63 and some freeholders were recently warned of an impending new commission there. Almost all the title deeds I examined indicated that title commissioners and not legal conveyancers had adjudicated and adjusted titles, resulting in transfers registered in the name of a selected person. At the heart of the matter (though not seen as such) are the legal rules of succession, which were split between the two bodies of official law. The law dictated that modes of inheritance were traced according to marriage; but western and customary marriages have had different succession rules regulated through the common law or customary law, and these were the rules followed by the white title commissioners in identifying heirs. There were complex consequences. For example, for titles to be valid, each successive heir must be registered separately, each decided by the relevant rules. In cases where the heirs were deceased and never registered, they still had to be identified and registered. The procedures were time-consuming and expensive, but could be obviated by the new simplified measures.

The most widely believed reason for registers getting out of date is 'ignorance'. Freeholders' avoidance of the law is interpreted as lack of education or plain slop-piness.64 The second contributory factor is cost. Registration is an extremely costly business in South Africa, a side effect of its rigour by world standards. There is also a prevalent view that sees registration (especially first registration) as biased towards men.

In recent times the state has introduced measures to overcome these perceived causes of failure to register transfer. An example is state subsidies to cover the transfer fees of first-time purchasers. Another is registration in the name of both spouses. These changes, including recent reforms of marriage and succession law,65 have not led to notable changes among the habits of titleholders, suggesting that something more systemic is at play.

The View from Below

We must keep in mind not only the capacity of state simplifications to transform the world but also the capacity of the society to modify, subvert, block, and even overturn the categories imposed on it... [T]here will always be a shadow land-tenure system lurking beside and beneath the official account in the land-records office. We must never assume that local practice conforms with state theory.

Scott, Seeing Like a State, 49

A picture very different from the official view emerges when viewed from below. Histories of individual properties and stories of family struggles reveal the deeper meanings of title. In Rabula and Fingo Village, there is a consistency in the local iteration of what it means for families to hold title. Individual family case histories may differ substantially in detail, but a consistent and comprehensible set of basic norms emerges from the jumble of everyday life. The principles that emerge provide an alternative normative framework against which to interpret local practices, casting considerable doubt on the official interpretation of failure to register transfers. The patterning of these norms is consistent with similar findings among freeholders in Kenya and Zimbabwe.66

By tracing the processes that families have employed to transmit property over time, by unravelling documentary evidence and reconstructing it in the light of people's own narratives, and by carefully inspecting the language people use in expressing concepts of ownership, it has been possible to identify the core norms that frame the meaning of title for African families. The norms are interpreted in terms of kinship relationships which have been adapted to fit the needs of ownership.

Property is regarded as a family asset to which all family members have rights of access, held for the family in perpetuity. Individuals cannot inherit the land in their individual capacity or dispose of the land unilaterally. Families are defined in terms of affiliation calculated according to descent, in this case patrilineal descent. The structure is held together by the concept of the family custodian, a representative selected to manage the property on behalf of its members, past, current and future.

'Family property helps to keep the family together,' according to Linda Sindiso Mnyemeni of Fingo Village. In words resonant across Fingo Village, she maintained:

I will leave this property to my children because this is their home, bought by their fathers who passed away. They were born here and grew up here. We call it family property because sometimes someone is disabled or unemployed. They can come back to that home. If a son or daughter [falls on hard times] you will take them in, even my grandchildren. 67

Respondents' description of family property is framed in terms of its reach in time from antecedents and the present generation to future generations. The key point of departure is the structure of the family itself, which differs from the nuclear family as structured in western-based property systems. The following case68 in Rabula reveals the contrasting perspectives of officialdom and local families on who owns the land. There are tensions between conflicting sources of law and social norms for determining ownership as well as contrasting models of the family.

The original family property of the first titleholder, Ndawo, was subject to state scrutiny when an irrigation development was planned in Rabula that would involve a furrow passing through the Ndawo plot. In the 1950s the state (represented by the native administration) needed to create a servitude69 in its favour to clearly differentiate public from private property. To effect this, the judicial branch of the native administration went to enormous lengths to identify the current legal owner, since the title deed was still registered in the name of the original grantee Ndawo, who bought the land in the mid-nineteenth century. The title had not been updated since the first acquisition, as was common throughout Rabula. Various officials and legal experts painstakingly traced the line of descent retrospectively from the date the property was first acquired.

The descendants were tracked through two legal routes in accordance with the dual provisions of common and customary law. The distinction between them was made on the basis of whether a marriage had been concluded on the basis of civil or customary law. The divide between the two sources of law had to be recalculated with each successive generation to take into account the marriage of each heir. The complications grew exponentially. In the end, the matter got more and more entangled in legalese, with very little unanimity between the various white customary law experts who debated the matter together. The problem was eventually solved by an administrative intervention.

The family had branched into two entities when other properties were acquired in the second generation. The property concerned is known by the name of Ndawo's eldest son John, who succeeded as family head and heir to the original family property. He is referred to as utat'omkhulu (grandfather), while the first grantee is referred to as indlunkulu ('first man') or ukhokho-wokhoko ('original antecedent').

Over 20 letters and memos were exchanged between various officials in the offices of the Bantu Affairs commissioner, chief Bantu Affairs commissioner, legal division of the Department of Bantu Affairs, the Native Appeal Court and the deeds registry spanning a period of four years, with extraordinary fastidiousness and attention to detail. Marriage and baptismal records were sought, family trees were drawn up, and Alastair Kerr was consulted as the customary law expert at Rhodes University.

Simon, son of John, alone was consulted from the family. He made a sworn statement to the native commissioner of Keiskammahoek in 1959, witnessed by a female family member, in which he stated: 'As far as I am aware my father John was not regarded as the sole heir, it being understood that the children inherited jointly.' He listed the names of 40 family members, male and female, with rights to the family property.

The white officials ignored his testimony, continuing to calculate backwards through the labyrinthine structure of legal pluralism. In addition to distinctions between common or customary rules of succession (for which each marriage in each generation had to be scrutinised), a second dilemma was whether the title still belonged (in theory) to the first name registered, or to the successor(s) in title. If the former, each generation would require discrete and separate conveyancing. If the latter, the marriage and offspring of each potential heir had to be traced and correlated with the respective succession rules. There were further complications in that the law of succession changed in terms of the Native Administration Act 38 of 1927 to exclude community of property from almost all African marriages. A possible application of the old mid-nineteenth century succession laws had also to be clarified. There were further intricate legal complications concerning a great-granddaughter who had had children out of wedlock, and a grandson who took a customary wife after the death of his first wife.

These questions were never resolved, nor were they resolvable through legal calculation. The matter drew to a close when a title commissioner discovered that a commissioner had been appointed in terms of section 8 of the Native Administration Act to establish current ownership. This had no direct connection to the water scheme, but was an administrative measure to 'rectify' African title where transfers had not been registered, as discussed earlier.

In spite of Simon's statement, the commissioner identified Simon alone as the true owner by virtue, not of the common law, but 'official' customary law, the eldest deceased son having been skipped over because he had had only daughters. The commissioner awarded the property to Simon, and he was registered on the title deed. An administrative solution thus satisfied state requirements, and took the pressure off the need to identify an heir. That drew the matter to conclusion from the state side, and the file was closed.

The family, when interviewed,70 were unaware of the succession crisis. They have continued to devolve property according to family custom and trace their ownership to their great grandfather, whom they refer to as ukhokho, founder of their lineage. All agnatically related71 family members, male and female, have rights to the property under the management of an identified custodian.72 Arable land is informally subdivided among the children, and women are allocated fields if domiciled within the patrilocal residence, but these remain under family ownership. The sister of the current custodian has retained her family name, Ndawo, and given it to her three children, thus retaining her patrilineal identity. As a wife she is not entitled to claim rights to Ndawo property. Her eligibility rests on her status as a daughter of the land-holding patrilineage, reinforced by the family name and residence. In the interviews the father of her children was not mentioned, indicating that her children's rights to family property are secured through the patrilineal family name. By retaining the family name she has simultaneously secured her own and her children's access in future. She intends to assume the role of manager from her brother after his death,73 an unconventional step for women by Rabula standards.

The story shows how the family views its ownership in terms of genealogical links in an endless chain of familial relationships that cannot be reduced to individuals named on the title deed. This stands in stark contrast to the official view that regards ownership as vesting in the identified heirs reflected on the title deed. This case reveals the different processes engaged to trace ownership. The western-trained experts, even when drawing on custom, follow precise rules of enumeration in contrast to the vernacular approach, which categorises potential claimants. For the freehold villagers, descendants are traced according to social relationships identified by genealogy. Individuals are not named, and claimants not usually quantified, though Simon made an effort to list names when pressed by the officials.

The narrative also illustrates how women claim rights as daughters or sisters within the parameters of patrilineal descent. This remains an important means by which modern women claim rights, and is a logical extension of women's access to land in pre-colonial times.74 The official version of customary law under colonial rule misinterpreted this as a male prerogative.

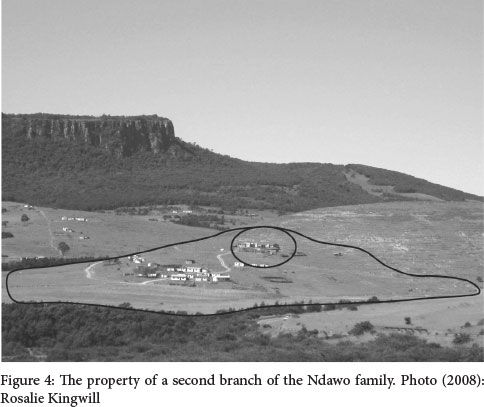

Figure 4 outlines the property of the second branch of the Ndawo family, taken from vantage point of the original property discussed in the story. The second branch has evolved into a sub-lineage of the Ndawo family descended from two younger brothers, now under Seth Ndawo. The two lineages regard themselves as 'one family', umzi omnye, for ritual and ceremonial purposes. The circle shows the main family homestead, which is modern and in some respects sumptuous by rural standards, below which are more modest homes occupied by relatives.

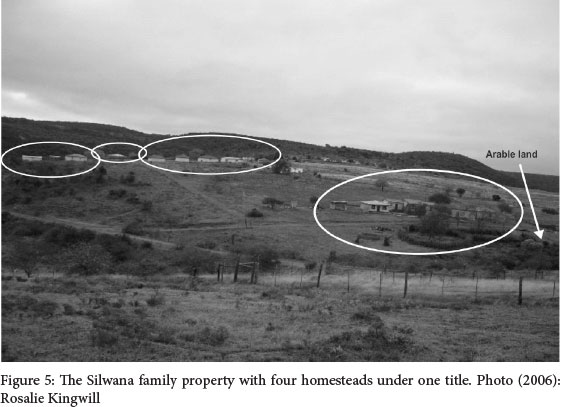

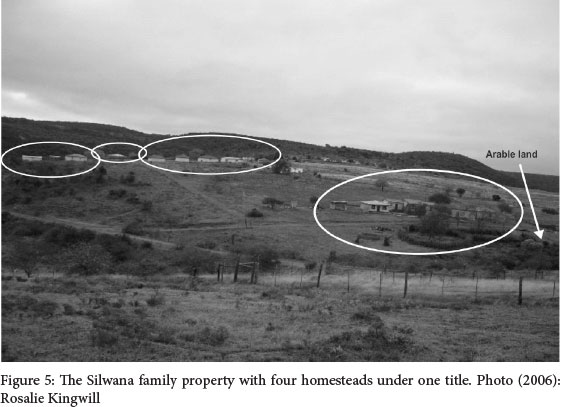

There are diverse configurations of family property. Figure 5 shows four family homesteads under one title.

The Rabula story suggests three areas where vernacular norms diverge from western law. The first is how the rights of individual family members are conceptualised. The second is the how the social unit that holds land (the 'family') is conceived. The third lies in the modes of distributing and transmitting property by succession and inheritance. These norms are further illustrated in the following case, where the tensions result from market demand for strategically located urban land, which threatens family-held property.

In Fingo Village, male kinsmen have come to realise their power to alienate family property by claiming rights of ownership using common-law rules. Common law is in theory gender-blind, but some men imagine they have superior powers fuelled by particular notions of masculinity in relation to control of property. Though outdated and discredited by constitutional principles of gender equity, these ideas continue to be prevalent. Gender struggles are waged on many fronts in all land tenure contexts.75 Title commissioners generally applied legal rules of succession, which in the case of civil law marriages resulted in females being registered, for example, as intestate successors to their husbands' estates. There are cases where it seems men were selected by virtue of their gender.76

In a case in Fingo Village, the family property had been registered in the name of a common grandfather, Jack. Bills continued to be made out in Jack's name, even after his death. The occupants comprised one of Jack's daughters, his grandchildren and great-grandchildren, who maintained close contact with other relatives who lived and worked elsewhere. There were also tenants living on the property, whose rent provided a crucially important source of income to complement their otherwise modest livelihoods.

The resident family assumed that the property was still registered in their forefather's name. This made them feel complacent and secure, as it was regarded as definite evidence that the property was owned by them. Registration in the name of an antecedent was not seen as evidence of insecure title, but rather it served, in terms of the norms and conventions of family property, to confer rights on all Jack's children and grandchildren.

The family was unaware that their cousin, who had his own house elsewhere, had succeeded in selling and transferring the property to the brother of a prominent lawyer in town for a nominal sum. Their illusions of security were shattered one day when a lorry pulled up alongside the house with building materials. The family was given three months to pack up and go. When the family members refused to vacate their home, the new owner delivered a lawyer's letter 'warning us if we continue to [resist] we will be arrested.'77 The evicted family members were scattered around Grahamstown's townships. I located one branch in circumstances of extreme poverty and tenure insecurity seven years later. The case still rankles in their minds and their bitterness is directed at the 'drunkard' cousin who, they maintain, needed the money to pay off his debts to a local moneylender. They interpreted his actions in terms of masculinity and power, that he thought he could do as he liked with the property as he was the mdoda (man). 'He felt he had the authority to sell the property because of his manhood powers . the way we were kicked out was merciless.'

In another eviction case, a three-generational family managed to retain their rights to the family property by sheer chance. The occupants were aware that a male heir was trying to evict them. He issued a summons through lawyers to his resident relatives, categorised as 'tenants', to remove themselves from the property. He was the only son of the person previously recorded as the owner on the title deed, and thus legally entitled to be the registered owner through intestate succession. As in the first case, he planned to sell the property, allegedly to offset debt. The family firmly believed the law to be on their side, which it is not. They thus sought assistance from legal aid bodies (and myself), whose interventions merely helped to stall the process. The case was never settled until his sudden and unexpected death put an end to his threats, at which point the management of the property reverted to the family's mode of appointing custodians to look after the property, but with no right to sell it. The previous custodian was a woman, as was her successor when the incident occurred.

The penchant by men to manipulate law and custom has heightened awareness by occupier-owners of their vulnerability to the proprietary powers of registered family members. A new pattern is emerging indicating a tightening up of mechanisms to protect family property.78 In increasing cases in Fingo Village women are being appointed as custodians. This feminising of the role of managers is overtly referred to as a form of insurance to protect family property, which includes the role of caring for vulnerable family members. Many resident family members are taking pro-active steps when they are forced to register someone, including strategies to prevent their brothers from being registered or from being named as managers of the family properties.79

A corollary of this theme came to the fore when a descendant tried to reverse the donation of the family property by a deceased relative to non-family. The complainant, Mrs Mpepo, claimed that he had no right (meaning customary right) to cede the property, which in her understanding was reserved for the family in perpetuity. She went to extraordinary lengths to research the history of her former family home, which had been ceded by the ailing owner to long-term occupiers from the former Ciskei who are believed to have taken care of him. When they left Grahamstown they sold to the neighbour, going through all the necessary legal steps of transfer into her name. Mpepo sought administrative intervention from a number of authorities, as well as legal aid institutions, to return the property to its 'rightful owners'. Her own testimony to me contradicts the consistent claim people make that family properties will 'never be sold'. She herself wanted to sell the property to invest in her own house elsewhere, which needed repairs. She was not successful in reversing the sale, the title having been legally conveyed to the present owner.80

'African Freehold': The Normative Thread

The law cannot produce a person to represent the home - Winston Mabusela81

I have traced the norms using Moore's concept of a 'semi-autonomous social field' in preference to 'local' as an analytic lens, since, as Moore argues, state law and local custom intertwine and compete at various levels and in diverse fields of society. The sub-state realm is neither fully independent of, nor fully integrated into, the state legal system.82 Moreover, African freehold cannot be conceptualised in terms of a specified place, corporation or organisation. The actors are affiliated to families that are spatially stretched across diverse social and economic landscapes. The concept of the family is a modern adaptation of lineages, which are not bound or corporate structures. It is misleading therefore to speak of the shadow process in terms of a binary distinction between state and local institutions.

The norms that come to the fore in the stories above represent replicated and patterned responses which are durable, but not first principles. As I have tried to show, the norms are malleable and adjustable to a variety of situations, and are sometimes revealed as much in their observance as in their breaking. Some aspects appear to be changing, while others seem resilient and resistant to change. Moore has theorised that

the maintenance of relationships of social exchange between social units depends heavily on the existence of replicated units with like normative orders. This may act as a brake on significant normative changes within individual subunits since innovations might cut off important relationships. The commitment to maintaining connections among units might account for some of the putative stability of 'customary law'. 83

Multiple family members are eligible for rights of access, but no one person has powers to own or dispose of the property individually. The concept of custodianship has emerged to protect properties from the very powers of alienation created in law. Among western families it is the opposite: the property belongs to identified individuals with power of alienation or 'dominion'. In both research sites family members own properties elsewhere, which become subject to new contingencies and take on characteristics of family property, but the first purchasers are free to sell. Thus we see that the norm of non-marketability is not a primal rule, but a contingency. Despite the oft-quoted phrase I heard repeatedly, that 'land will never be sold', I never heard it be said that in actual fact 'land is never sold.' The principles must always be combined with context and circumstance. The histories reveal that every decision is relational and contingent, and that norms act as a set of guidelines against which changes are measured.

The motive of heirs who sell family property is often to settle debts with local moneylenders, rather than to obtain the property for themselves. These cases result in conflict and emotional confrontations between family members. Those threatened by eviction invariably seek legal assistance and are confused to discover the law cannot help them. Cases such as these provoke legal dilemmas, since there is no 'law' that lawyers can draw from to stay these sales, and they are unfamiliar with the strength and meaning of local norms.

The deeper meanings of ownership are embedded in the composition of land holding groups. These are not finite corporate entities. Lineages are different from conventional groups in that they are designed to last in succession, with qualities of infinity. This is unlike the western model, where bilaterally related kin reconstruct the family afresh with each passing generation. This fits neatly with the quantifiable basis of western concepts of ownership, title and more latterly, proprietorship. It does not fit with the African notion of kinsmen and women who are categorised, rather than listed, as eligible. By creating an unending chain of relationships in time and space, the lineage (in this case patrilineage) exists in its own right, separate from its members, and is ironically strengthened by association with title. The closest approximation in western law is a trust or company that is separate from its members.

Descent calculated through the male line results in a highly gendered structure of the family,84 as indeed prevails in matrilineal societies too.85 This model is not based on the conjugal unit. Wives have circumscribed rights to transmit property, while sisters and daughters have full access to property as long as they retain the family name and are frequently resident. The idea that customary systems militate against women owning property requires some qualification in that research findings show that the approach readily adjusts to agnatically related women succeeding to rights to property, as daughters and sisters, and discourages any form of individual ownership, male or female. It is rather as wives that women find themselves in tense positions alongside new constitutional models of gender equity and the modern emphasis on nucleated families.

In the past the oldest adult male assumed responsibility for the entire family, seen as a polygamous household with wives of each house (even if it was only one) having roles of authority and access to fields, but little control over the family property as a whole.86 It has been no revolutionary change for the role of responsibility to evolve into a concept of custodianship without connotations of heritability, but which emphasises responsibility.

It follows that if individuals do not have powers to own or dispose of the property, there can be no inheritance by individuals. The property passes to successive generations by dint of the lineage identity, which, as mentioned, is not an 'entity' but persists in perpetuity, apart from its members. There was a concept of individual inheritance, but this applied to moveables (cattle) over which an heir, termed indlalifa and always male, could be identified. Colonial officialdom applied these rules on individual inheritance of moveables to inheritance of land by adapting African succession norms to fit with the European concept of male primogeniture.87 In so far as there was an African customary concept of male primogeniture, it was succession to a position of authority rather than to a material object.88 Freeholders explicitly avoid the term indlalifa since it matches neither the non-proprietary prescripts of African freehold nor the concept of custodianship.89

Since property requires management (particularly where servicing and billing come into play), it is the older concept of indlunkulu, head of the family, that has yielded to a concept of custodianship, usually referred to in English as 'responsible person'. The virtual abandonment of principles of heritability has led to emphasis on qualities such as responsibility, sobriety, capacity and trustworthiness, thembekileyo.90 The idea that a responsible person should have personal attributes clashes fundamentally with the idea of formal inheritance of the property through the preselection of an appointed heir or heirs with powers of alienation. Such attributes cannot be predicated on wills; nor can division of material property substitute for the role of a caretaker and property manager.

Xhosa terminology struggles to find new terms to capture the adaptive features of customary concepts. The idea of 'keeper', 'caretaker', even 'housekeeper', meaning someone who 'looks after' the property, has resulted in a widely used isiXhosa term, umgcini ekhaya (keeper of the home), adapted from the verb ugcina, to look after. The idea of 'keeping the house' nevertheless does not clash with the concept of ownership.

I am the owner; this is my property.. It is the custom that even though this is my property, I do not have the right to sell it.91

Educated people prefer to use the term imeli (representative) and some think the 'keeper' analogy likens ownership to the role of servants.92 No particular expression has replaced customary concepts, but in English 'responsible person' is the most common. A responsible person is required to act in the interests of the entire family and is validated by family consent rather than title deed. 'One person is the responsible person. That doesn't mean they can sell. Property belongs to the whole family, who decide.'93 The 'caring' metaphor resonates with the feminisation of the role in Fingo Village, and extends to caring for the potentially vulnerable, disabled or indigent members of the family. Interestingly, when the Mpepo property was ceded to non-family, the circumstances fitted some of the criteria: the (male) tenants had contributed to the household maintenance and cared for the owner despite the lack of genealogical ties, while the unsuccessful family claimant had only one card in the deck: the genealogical claim. This story illustrates that kinship based on descent, as well as status, is qualified by involvement and need. Respondents stress family contingencies. 'People are unique and we don't strictly follow the old sequence.'94

Families always have their reasons... Every family see[s] how their children grow up... A younger brother can take over... Its not always ... the firstborn. If the family agrees . the last one must take the property, so it depends on all the family.95

Peters warns against flexibility being confused with open-endedness,96 since the norms can be stretched only within observed parameters and are not 'randomly flung together'. There is 'a certain systematicity in social practices and ideology',97 but particular triggers of change may be seen as a permanent change of direction, which Moore calls 'diagnostic events'.98

Preference for an ancestor on the title rather than a living registered owner can thus be seen as neither an irrational act of negligence nor a voluntary act of subversion. Rather, it is a strategy to protect property against a living owner having too much power over the property. It has the added value of linking the present and future generations to the antecedents who spawn them.

When viewed as a whole, we see that claims to family property are a 'right to a right' within a social context, and which serve as an investment in social relationships as a means to channel important resources.99 Secondly, genealogical schema derived from principles of descent can be overridden. Rights are generated through descent, but kept active through participation and adherence to the repertoire of family norms. Jural rules can be manipulated, as with formal law, and should be seen not as deviations but as an integral aspect of how norms are adapted and play out in the struggles of everyday life.100 This interpretation departs from a widespread misapprehension that customary law is a body of rules set in ancient stone, and lends credence to the concept of 'living law.101

Conclusion

... the question of property is not so much unspeakable as conditional, depending on which relationships are involved, - J. Roitman, Fiscal Disobedience102

This article has focused on how customary norms of social relationships and land holding infuse tenure regimes that are nominally private in character. The stories illustrate the criteria that condition rights of access to, and control of, family property under African freehold arrangements. 'Property' and 'family' are conjoined through principles of perpetual succession and progression through the family line symbolised by the family name, which is in turn symbolised by the paper title itself. African freeholders view their paper titles as a fulcrum on which both property and kinship relationships balance. The name of a forebear on the title reinforces social identity through descent and underscores the centrality of the family name, which in turn perpetuates the family itself. Registration has been separated from its western-law rootedness in individual owners and heirs with proprietal powers.

Family property signifies both social identity and access to land, which together facilitate access to social and material resources. Descent and affiliation are combined with personal qualities that contribute to the family welfare, entrusted to a family representative. Taken together, these criteria represent a basis for rights that is regarded as superior to registration of an individual on a title deed.

The phenomenon is not restricted to African freehold'. Okoth-Ogendo powerfully shows how in Africa the phenomena that make up land tenure relationships are not reducible to complete power by one owner over the 'physical solum' but rather shape sets of graduating relationships between social units and units of authority, the former ensuring access, the latter regulating control. Particular economic, sociological and ecological contexts influence the shape of these relationships, which generally cannot be poured into a mould that attempts to capture one-to-one relationships between people, property and space. Western paper systems are seldom capable of reflecting these multiplex social relationships.103

A salutary change in the scholarship has seen the beginnings of reintegration of the domestic and property realms into land tenure discourses. Feminist scholarship has revisited concepts of kinship and the family in recent decades as a way of deepening our understanding of the gendered patterns of inequality in the modern world.104 Pauline Peters goes further to suggest that a focus on kinship should not imply a divorce from matters of the political economy, since, far from being mutually exclusive concepts, familial relationships form a substructure of the political economy.105 Domestic arrangements could be considered as basic building blocks of society. In the African context, law at that level is not 'atomised, egotistical, and contractual and focussed on private interests in property' as it is in a market economy.106 Instead, familial relationships exist in relation to wider, intermeshing social networks that draw from socially validated norms, all of which constitute configurations of power. In situations of uncertainty over, and confusion between, state law and customary norms, customary practices may reinforce relationships of subordination, discrimination and corruption if unsupported by coherent institutional frameworks that accord with constitutional principles and values.

This article has attempted to address the social relationships that come to the fore in African property relationships through the prism of land title. The mix of imported and indigenous concepts has not resulted in a functional hybrid. The customary and western norms prevail in various layers of tension and are in some respects in competition with each other. Anomalies and contradictions abound, unseen by the state and even the titleholders themselves. The legal devices devised by the state over the course of time do not address the underlying tensions, but paper over the cracks.

Research findings reveal that comparable tendencies manifest themselves in a range of other tenure systems in South Africa, including various constructions of group or community tenure by means of title or communal tenure under traditional forms of governance.107 Neither the common law concepts of property (as discussed in the first part of this article) nor officially endorsed customary law adequately reflect the way people manage their land and property relationships. The division of South African law into a binary between these two bodies of law, as well as between formal ownership and other recognised but 'lesser' rights, impedes the diversity of land rights in South Africa from meshing into one single framework that suits both customary and western norms. Rights falling outside the legal 'ownership' paradigm are locally, but not nationally, accorded recognition in law, which cuts them off from a range of other resources such as national adjudication, dispute resolution, credit and services. Recent land reform initiatives have endorsed, rather than attempted to integrate, these parallel systems.

International scholarship suggests that there may be inherent limitations in legislating social change from above. James Scott, for example, argues, that there will 'always be a shadow system'.108 Moore notes that the reach of law is always incomplete, as is custom. In this respect, she sees local rule making and state rule making as analogous, and both are only ever able to attain 'partial order and partial control . legal systems can never become a fully coherent, consistent whole which successfully regulate all of social life.'109 Moore stresses that all social fields are marked by processes of struggle: 'The making of rules and social and symbolic order is a human industry matched only by manipulation, circumvention, remaking, replacing, and unmaking rules and symbols in which people are equally engaged.'110

State-enforced law nevertheless has some advantages over sub-state normative orders. Officially endorsed law has supportive judicial, legislative and executive institutions that provide checks and balances to protect society against abuses. 'Shadow systems' have limited access to these mechanisms, and this limitation in turn restricts the scope of prevailing norms that are considered in the formation of law. South Africa's 'super-law', the Constitution, remains accessible as the final arbiter - but its reach, too, is limited.

Evidently, then, South African law reform is inherently constrained by the extremely hierarchical structure of property law, which, far from having to be taken as a necessary 'given', evolved to meet the requirements of colonial segregationist policies. Recent attempts at legislating social change from above, without the necessary institutional support, may accentuate rather than alleviate the legal and social divisions that arose under colonial rule. The acceptance of the colonial model by the post-apartheid state effectively endorses a long political history of highly unequal land access, with the 'shadow' land tenure systems permanently subordinated to the western idea of land ownership, with its related concepts of kinship and property. To ignore systems that do not conform to the standards set by this legal hierarchy is to condemn them to the permanent shadows of society.

Chanock's metaphor of 'pathological legal pluralism' to describe South Africa's segregationist past continues to haunt the present.111 The Nigerian intellectual Claude Ake warned of the dangers of a widespread sense of alienation that comes about when people's 'social experience' is sidestepped in the rush to democratise society in a peculiarly western mould:

One of the most urgent tasks of democratization in Africa is to democratize in such a manner that law and the rule of law are relevant to social experience. By enabling and protecting, law defines the realm of freedom, prevents arbitrary power and secures order in justice, thereby contributing immensely to the sense of well-being. It is extremely alienating for people to live under a system of law which does not connect to their social experience; it gives a pervasive sense of helplessness amid a chaos of arbitrariness.112

1 G. Wille, Wille's Principles of South African Law ed. D. Hutchinson, B. van Heerden, D. Visser and C. van der Merwe (Cape Town: Juta, 8th edition, 1991), 304. [ Links ]

2 Interview with B. Makuzeni, Rabula, Keiskammahoek district, former Ciskei, 14 July 2006.

3 Interview with M. Makuzeni, Rabula, 15 May 2008.

4 This article is drawn from my dissertation 'The Map Is Not the Territory: Law and Custom in "African Freehold": A South African Case Study' (Unpublished PhD thesis, Institute for Poverty, Land and Agrarian Studies, University of the Western Cape, 2014).

5 J. Roitman, Fiscal Disobedience: An Anthropology of Economic Regulation in Central Africa (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2005) 90; [ Links ] H. Okoth-Ogendo, 'Some Issues of Theory in the Study of Tenure Relations in African Agriculture', Africa, 59, 1, 1989, 6-12. [ Links ]

6 Legal texts and scholarship tend to separate the components and view them ahistorically as 'given', as in ownership, succession, registration, conveyancing and surveying, but there are exceptions to that positivist perspective. See M. Chanock, The Making of South African Legal Culture 1902-1936 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001); [ Links ] A. J. van der Walt and D. Kleyn, 'Duplex Dominium: The History and Significance of the Concept of Divided Ownership' in D. Visser (ed.), Essays in the History of Law. (Cape Town: Juta, 1989); [ Links ] D. Visser, 'The "Absoluteness" of Ownership: The South African Common Law in Perspective' in T. W. Bennett, W. Dean, D. Hutchinson, I. Leeman and D. van Zyl Smit (eds), Land Ownership: Changing Concepts (Cape Town: Juta, 1986). [ Links ] For a historiographical approach to the cadastre, see G. Barnes, 'The South African Cadastre: An Overview of the Geodetic Network, Land Registration and Surveying Profession', Central and Eastern Europe Seminar 951, International Federation of Surveyors (FIG) and International Office for Cadastre and Land Records, 1984; and to fencing, see L. van Sittert, 'Holding the Line: The Rural Enclosure Movement in the Cape Colony, c. 1865-1910', Journal of African History, 43, 1, 2002, 95-118.

7 R. Moyer, 'A History of the Mfengu of the Eastern Cape 1815-1865' (Unpublished PhD thesis, School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, 1976), 260.

8 J. Peires, The Dead Will Arise: Nongqawuse and the Great Xhosa Cattle-Killing Movement of 1856-7 (Johannesburg and Cape Town: Jonathan Ball, 1989, 2nd edn 1989), 65-73, 337, 339. [ Links ]

9 Quitrent tenure involved state allocations on the basis of annual payment of quitrent, which ceased after a stipulated period. Under the Dutch, boundaries were often estimations, and landholding registers correspondingly poorly administered. These imprecise methods were gradually superseded by compulsory survey and registration under the British.

10 Peires, Dead Will Arise, 313; Moyer, 'History of the Mfengu of the Eastern Cape 1815-1865', 223, 234-40, 259, 360, 380, 390; A. du Toit, 'The Cape Frontier: A Study of Native Policy with Reference to the Years 1849-1866' in Archives Year Book for South African History, vol 1 (Pretoria: Government Printer, 1954), 105-108.

11 W. Hammond-Tooke, 'In Search of the Lineage: The Cape Nguni Case'. (Man, New Series, 19, 1, 1984), 77-93; [ Links ] M. Hunter, Reaction to Conquest: Effects of Contact with Europeans on the Pondo of South Africa (Cape Town: David Philip; London, Rex Collings, abridged edn 1979), 15, 65; [ Links ] Moyer, 'History of the Mfengu of the Eastern Cape 1815-1865', 360; Peires, Dead Will Arise, 414; B. Sansom, 'Traditional Economic Systems' in W. Hammond-Tooke (ed.), The Bantu-speaking Peoples of Southern Africa (London, Boston and Henley: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1974, 2nd edn 1959), 139.

12 There were exceptions to all these models, e.g. rural freehold villages configured on similar lines to quitrent villages.

13 Du Toit, 'Cape Frontier', 276; Moyer, 'History of the Mfengu of the Eastern Cape 1815-1865', 354; Peires, Dead Will Arise, 347.

14 The developments in the science of geodesy modernised surveying from planar to geodetic surveying, which takes into account the theoretical curvature of the earth's surface.

15 The Cape was linked to global developments in geodesy when it was selected as a site for scientific research initiated to extend the baseline for measuring the world's land surface taking into account the earth's curvature. The Cape site was used to measure the southern arc of the meridian to complement other arcs, such as the meridian in the northern hemisphere and India. For a summary see http://whc.unesco.org/en/tentativelists/5461/. See J. Keay. The Great Arc: The Dramatic Tale of How India Was Mapped and Everest Was Named. (New York: Harper Collins, 2000). The direct investment by France and Britain in the Cape infrastructure contributed to the systematic development of surveying and cartography in South Africa.

16 Comprising a telescope connected to two rotating circles to measure horizontal and vertical angles. It was modernised in Britain in 1785 in the course of measuring the principal triangulation of Britain from 1783 to 1853. See J. Insley, 'From London to South Africa', South African Journal of Survey and Mapping, 24, 1997, 83-9. Smaller and lighter models evolved for easier transfer to distant and rugged terrains.

17 Barnes, 'The South African Cadastre'; A. J. van den Berg, chief surveyor-general, South African Department of Land Affairs, 'South Africa Country Report' for FIG 2003, https://www.fig.net/cadastraltemplate/countrydata/za.htm

18 A. Christopher, 'Land Policy in Southern Africa During the Nineteenth Century', Zambezia, 2, 1, 1971, 1-9. [ Links ]

19 W. Macmillan, 'The South African Agrarian Problem and Its Historical Development', lectures delivered at University College, Johannesburg (Johannesburg: University College, 1919), 33. [ Links ]

20 Quitrent tenure for whites was abolished in stages between 1934 and 1977, automatically converted to freehold. African quitrent titles were retained, though no new titles were issued after the 1920s, and in 1992 they were converted to freehold. See Kingwill, 'Map Is Not the Territory', 140.

21 P. Peters, 'The Limits of Negotiability: 'Security, Equity and Class Formation in Africa's Land Systems' in K. Juul, and C. Lund (eds), Negotiating Property in Africa (Portsmouth: Heinemann, 2002), 45; C. Bundy, The Rise and Fall of the South African Peasantry (London: Heineman, 1979). In the late colonial period, Anglophone governments in Kenya and Zimbabwe imagined they could develop the agrarian economy by converting African customary systems into freehold to foster a class of African peasant farmers with access to new agricultural methods. S. Berry, No Condition Is Permanent (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1993) 125-8; A. Cheater, 'Fighting over Property: The Articulation of Dominant and Subordinate Legal Systems Governing the Inheritance of Immovable Property among Blacks in Zimbabwe', Africa , 57, 2, 1987, 173-95; A. Haugerud, 'Land Tenure and Agrarian Change in Kenya', Africa, 59, 1, 1989, 63-4; F. Mackenzie '"A Piece of Land Never Shrinks": Reconceptualising Land Tenure in a Smallholding District, Kenya' in J. Bassett and D. Crummey (eds), Land in African Agrarian Systems (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press 1993),194-221; Kingwill, 'Map Is Not the Territory', 65; 330.

22 Chanock, Making of South African Legal Culture 1902-1936, 292.

23 Regulations for the administration and distribution of native estates framed under the provisions of subsection 10 of section 23 of the Native Administration Act 1927 (Government Gazette, 20 September 1929, notice 1664), 877; Regulations for the administration and distribution of estates of deceased blacks (Government Gazette, 6 February 1987, notice R200), 21.

24 Government Commission on Native Laws and Customs, Cape of Good Hope, 'Report and Proceedings with Appendices' (Cape of Good Hope, Blue Book 1883, G. 4); South African Native Affairs Commission 1903-5, 'Report with Annexures'; Union of South Africa, 'Report on Native Location Surveys' (UG 42-22); H. Rogers, Native Administration in the Union of South Africa (Pretoria: Union of South Africa, 2nd edn 1949); E. Brookes, The History of Native Policy in South Africa from 1830 to the Present Day, (Cape Town: Nasionale Pers, 1924).

25 See S. Dubow, 'Holding "a Just Balance Between White and Black": The Native Affairs Department in South Africa c. 1920-33', Journal of Southern African Studies, 12, 2, 1986, 217-39 and I. [ Links ] Evans, Bureaucracy and Race: Native Administration in South Africa (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997). [ Links ]

26 J. Scott, Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1998), 7. [ Links ]

27 Against which 'third parties' may also have rights, on servitudes, for example, which are also surveyed.

28 D. Carey-Miller with A. Pope, Land Title in South Africa (Cape Town: Juta, 2000), 64. [ Links ]

29 For the legal history see P. Badenhorst, J. Pienaar and H. Mostert, Silberberg and Schoeman's The Law of Property (Durban: LexisNexis Butterworths, 5th edn 2006), 204.

30 In terms of Governor Cradock's 'Cradock Proclamation'.

31 Badenhorst et al, Silberberg and Schoeman's The Law of Property, 204.

32 Ibid, 205; Carey-Miller with Pope, Land Title in South Africa, 53.

33 Wille, Wille's Principles of South African Law, 38-43.

34 See Van der Walt and Kleyn, 'Duplex Dominium'; Badenhorst et al, Silberberg and Schoeman's The Law of Property, 6.

35 By judicial precedent, see Chanock, Making of South African Legal Culture 1902-1936, 376-377. Van der Walt and Kleyn describe the direction taken as the adoption of 'a dogmatic approach'. Van der Walt and Kleyn, 'Duplex Dominium', 248.

36 At law known as 'intestate estates'.

37 C. Rautenbach, 'South African Common and Customary Law of Intestate Succession: A Question of Harmonisation, Integration or Abolition', Electronic Journal of Comparative Law, 12, 1, 2008. [ Links ]

38 The idea of a bundle of powers (or rights) was conceived by the English jurist Sir Henry Maine in the nineteenth century. H. Maine, Ancient Law (London and New York: Everyman's Library, 1861, 1917 edn), 158. [ Links ]

39 Kingwill, 'Map Is Not the Territory', 307.

40 Peires, Dead Will Arise, 69-82, 337.

41 Du Toit, 'Cape Frontier', 276; Moyer, 'History of the Mfengu of the Eastern Cape 1815-1865', 354; Peires, Dead Will Arise, 347.

42 M. E. Mills and M. Wilson, Keiskammahoek Rural Survey, vol 4: Land Tenure (Pietermaritzburg: Shooter and Shuter, 1952), 47. [ Links ]

43 T. Keegan, Colonial South Africa and the Origins of the Racial Order (Cape Town and Johannesburg: David Philip, 1996), 243. [ Links ]

44 See inter alia C. Hamilton (ed.), The Mfecane Aftermath: Reconstructive Debates in Southern African History (Johannesburg: Wits University Press; Pietermaritzburg: University of Natal Press, 1995); T. Keegan, Colonial South Africa and the Origins of the Racial Order (Cape Town: David Philip. 1996), 145, 227, 330; J. Peires, '"Fellows with big holes in their ears": The Ethnic Origins of the AmaMfengu', Quarterly Bulletin of the National Library of South Africa, 65, 3 and 4, 2011, 55. For a good summary, see also L. Switzer, Power and Resistance in an African Society: The Ciskei Xhosa and the Making of South Africa (Pietermaritzburg: University of Natal Press), 1993, 58-9.

45 R. Moyer, 'History of the Mfengu of the Eastern Cape 1815-1865', 345, 355-61, 370, 384, 393.

46 Many other groups in neighbouring villages opted for communal tenure, see Mills and Wilson, Keiskammahoek Rural Survey, vol 4, 4.

47 Statistics were compiled by quantifying information in deed records in the King William's Town deeds registry in 2007, tabulated in detail in Kingwill, 'Map Is Not the Territory'.