Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Kronos

On-line version ISSN 2309-9585

Print version ISSN 0259-0190

Kronos vol.40 n.1 Cape Town Nov. 2014

ARTICLES

False fathers and false sons: Immigration officials in Cape Town, documents and verifying minor sons from India in the first half of the Twentieth Century

Uma Dhupelia-Mesthrie

Department of History, University of the Western Cape

ABSTRACT

This article1 examines the rituals of admission to Cape Town, developed by the immigration bureaucracy at the port, for minor sons from India. It provides a context for why the entry of sons of established Indian residents became an issue. Drawing on local knowledge as well as the official archives, the article takes one into the heart of immigration encounters. Its primary focus is on systems of identification and verification of relationships and ages, the role that documents played, and what this says about state power. It points to a progression from fairly primitive methods employed in the early years to demands for certificates to be completed in India, inter-governmental cooperation, village enquiries in India, and the use of technology such as fingerprinting, photographs and x-rays. Over time the bureaucracy seemingly became more powerful. Yet individuals coming from India, where the documentation of individual identity was not a significant state priority, responded creatively. Paying attention to the documents themselves, this article argues that, despite elaborate paperwork and systems, truths about fathers and sons remained elusive. The article points to how, despite demanding documents from India, officials in Cape Town, with some justification, distrusted these papers. The very documentary systems developed to ensure state control over who would be admitted into the country undermined the state's ability to do precisely that.

The Kalusta Karjiker Educational Society is one of several Indian village societies that exist in Cape Town. Founded by Muslim Indians who originated from the Konkan areas of what is today Maharashtra, these village societies display a keen interest in the history of the pioneer immigrants. Noor Ruknuddien Parker, a local Kalusta historian, wrote an article for the society in 2010 where he referred, with some relish, to how immigrants from Kalusta subverted the immigration law of South Africa which, while prohibiting Indian immigration, allowed entry for the minor children of resident Indians.

Kaluskars devised an ingenious tactic. Many brought their brothers, sisters, nephews and nieces as their own children - the so called "parcel babies" or pseudo-adopted children. It is estimated that about 30-40% of all Kaluskars in Cape Town are of such origins.

At a recent family gathering ... that of eight Kaluskars sitting at the same table, five were of those who had either come as "parcel babies" or were descendants of these "parcel babies."2

The term 'parcel babies' is original; Chinese immigrants in South Africa and America have used the term 'paper sons and daughters' to indicate those possessing false documents.3

The practice of bringing in false children to the Cape dates back to the Immigration Acts of the Cape Colony (Act 47 of 1902 and Act 30 of 1906), which imposed literacy tests in a European language on new immigrants, thus closing off immigration from India except for wives and minor children of resident Indians exempted from the test. It continued through Union, as under the Immigration Regulation Act of 1913 all new Indian immigration was prohibited nationally except for wives and children of resident Indians. From across the Bombay Presidency (this includes current-day Gujarat and Maharashtra) there came to Cape Town false sons, Hindu and Muslim, to false fathers.

Ramjee Magan, born in Cape Town in 1922 and now one of the oldest Gujarati Hindus there, volunteered the following about his father, who had come to Cape Town from Gandevi in Surat in the early 1900s:

My father was Magan Lalla, also known as Magan Pursotham. Why? Because he came to ... South Africa as somebody else's son. Because at that time if you over 16 you can't come to South Africa. So he being 12 years old and my other uncle Chaganlal Pursotam - he was 17 - so they swopped my father in. He said Tu ja, taru taqdeer che to jaa [You go, it's your fate so go]. So my father being 12 they say you are now Magan Pursotam but his real name is ... Lalla.4

Abdulla Gangraker, born in Athlone in 1943, is well known in Cape Town as the owner of the Wembley group of companies, which includes the Wembley Roadhouse in Belgravia Road, Athlone. He related how his father Eshack left Morba in the Konkan area:

And he came in 1909 at the age of thirteen and a half years old ... my dad didn't come as Gangraker. He came with another surname. Somebody adopted him, only to bring him over from India to Cape Town as a child. So that time he brought his age down to 13 and a half [It was] not the actual age.5

This article discusses 'fathers' and 'sons'.6 What do Magan and Gangraker mean when they use the word 'adopted' or 'swopped'? How did Magan Lalla accomplish a change of surname? How was Eshack able to make adjustments to his age? Where did the documentation happen? We have significant studies of immigration legislation and policies especially for the post-Union period, yet there has been little focus on the paperwork needed for immigration.7 Andrew MacDonald has recently called for a shift to that 'moment of "collision" between migrants and the immigration bureaucracy'.8 This is in line with international literature such as that of Adam McKeown, who draws attention to 'ceremonies of admission'.9 The present article looks primarily at arrivals at one of the country's most significant ports, Cape Town, and shifts discussion from the impact of immigration on the Cape,10 towards the heart of immigration encounters. It spans the pre-Union as well as Union period, allowing one to look at the relevance of such transitions, and draws on local knowledge as well as the official archives. The arrival of false sons was not unique to the Cape; two immigration officers in Natal and the Transvaal, Harry Smith and Montford Chamney respectively, had similar challenges of verifying and disproving relations.11

What is offered here is a detailed examination of processes absent from the literature. The emphasis is on the paperwork of encounters and the role of documents in establishing identity, which contributes to the historiography on identity and recognition.12 The central question faced by an immigration officer at the port was 'Who is this person?';13 hence the need to develop 'a documentary regime of verification'.14 Fraud and state paper systems go hand in hand. Raman has aptly pointed to the 'duplicity of paper',15 while Kamal Sadiq argues: 'Documents give states power for social and political sorting and thereby order, and yet it is the documents themselves that undermine this fig leaf of order and security'.16 Ben Kafka poses two questions: 'What does paperwork do for power? What does it do to power?'17 Kafka and several new writers have argued for the need to prioritise the materiality of paper - to look not just through it for information as has been customary but to make the document itself a subject of study.18

This article draws attention to passenger forms, temporary permits for admission, short narratives of passenger interviews by immigration officials, and documents of identity attesting to relationships and ages completed in India. By drawing on archives segregated by the state, the argument is made that the Immigration Department played a role in categorising residents and there were distinct ways in which it treated those it categorised. The demand for identity papers from India led individuals who came from a system of governance that did not place the identification of individuals as a high state priority to respond creatively. The state assumed a position of power through its paperwork and it seemed all-powerful; but as documents can and do lie, the truth was not always evident. Port officials recognising the unreliability of paper relied on instinct and visual assessments to penetrate the truth of documents. Much of this article is about officials questioning paperwork completed in India, yet demanding documents nonetheless.

The Cape Colonial Immigration Department and Its Paper Systems

Table Bay has a long history as a port: regulations for entry date back to Dutch East India Company rule. The entry of slaves was regulated and a 'restrictive paper-based immigration statute' required free immigrants to prove their European citizenship, religious affiliations, personal identity, and produce character references and evidence of financial standing. New arrivals were also registered. British rule brought legislation in 1806 'to prevent the evils that arise from the improper introduction of strangers into the colony'. After letters of recommendation and documents attesting to marital status, education and work history were produced, a 'permission to remain' certificate was issued. Magistrates registered new arrivals, and shipmasters and innkeepers provided information about 'strangers'. After 1828, the police took responsibility for new arrivals requiring a 'certificate of good character' and in the 1850s a dedicated Water Police Corps was established. Shipmasters produced passenger and crew lists. Yet by the midnineteenth century, MacDonald argues, there was disarray, which he attributes to 'Victorian liberalism [which] demanded free movement on both commercial and philosophical grounds' and a desire to increase the white population. He concludes that 'law enforcement and strategic permissiveness riddled immigration controls at the port by the 1850s - they would remain in disrepair until the end of the century'.19

By the turn of the century, responsibility for access to the ports of the Cape Colony rested with the medical officer of health (MOH). In the changed circumstances produced by the South African War (1899-1902) and the booming local economy, immigrants from around the world came to Cape Town, Europeans far outnumbering others. The city of Cape Town more than doubled between 1891 and 1904 and Table Bay Harbour was expanded to cope with the large number of ships arriving. The desire to control access to the ports of the colony grew. Vivian Bickford-Smith has commented that the period of prosperity brought troubles to the ruling class, facing them with 'how to maintain material and social order'.20 One step was to pass Act 47 of 1902, which aimed 'to place certain restrictions on Immigration and to provide for the removal of prohibited immigrants'. In the words of A. J. Gregory, the MOH, it was intended 'to restrict undesirable immigration'.21 Contenders for the status of undesirable or prohibited immigrants included prostitutes, pimps, lunatics, and criminals with convictions. To secure entry into Cape ports, immigrants had to be able to write in a European language and have 'visible means of support' (regulations fixed this at £5 and later £20). Anyone 'likely to become a public charge' to the colony fell in the category of the prohibited. For the poor and illiterate to enter, they had to be European with formal contracts of engagement.22 Domiciled residents were exempted from the writing and monetary requirements, as were their wives and children who wished to enter.

It is well documented that immigration from the East, especially from India, was one of the main targets of this legislation, as were the poor eastern European Jews arriving in large numbers.23 The literacy requirement is an example of how systems of control were shared and emulated. Among the South African colonies, Natal was a pioneer in this regard: Natal was inspired by American debates and practice, and then the Australians, New Zealanders, the Cape Colony and, later, the Transvaal were all inspired by Natal. In Jeremy Martens' observation, their 'shared history of immigration restriction ... bound together settler society on both sides of the Indian Ocean'. 24

The Act's significance lay in its transformation of the systems at the ports. 'Health concerns', which had previously governed access, were 'melded' with 'immigration concerns'.25 In 1904 an Immigration Department responsible to the Office of the Colonial Secretary was established, thus relieving the port health officers of administering the Act. The department was dominated for a decade by Clarence Wilfred Cousins, from his appointment as chief immigration officer in 1905 up to his move to the Transvaal as registrar of Asiatics and principal immigration officer.26 The 33-year-old historian and teacher turned civil servant27 played a central role in developing the paper systems of the department, which survived for decades. He came with little experience in immigration matters but read about immigration practices in other countries soon after his appointment and also drew on the advice of the Principal Immigration Officer in Natal.28 By 1915, he oversaw a department comprised of officers based at the docks (Cape Town, Port Elizabeth, East London), officers charged with paperwork in the office in Parliament Street, interpreters, detectives, and guards of the detention depot. In Cape Town, the staff numbered about a dozen (see Figure 1).29

Cousins provides an account of his own arrival in 1896 at Table Bay:

All it required in those happier times was a dissatisfaction with one's prospects in England, an interest aroused in South Africa, a readiness to adventure, the taking of Castle liner passage, a move with one's few belongings through the Cape Town customs shed, with no questions asked, no papers demanded, no money produced. It was a free and friendly country in a free world. It was a case of - "go where and do what you please" ... It was all as easy and happy as that.30

All this would change with Cousins playing a significant role. Gregory, the MOH who was the first to initiate new paper systems at the port in 1903, reflects: 'On first putting into operation an entirely new legislative departure, affecting as does this Act persons in all parts of the world, some considerable time must be allowed before details of working are evolved, administrative requirements gauged, and forms and systems of records constructed.'31

Regulations were issued to indicate the responsibilities of ship owners and shipmasters, for instance, with regard to their crew or to those prohibited. A schedule of passenger details was required: names, ages, port of origin, port of destination, nationality, occupation, and residence upon landing.32 Passengers signed one of four forms before the ship entered port, indicating under what provision of the Act they sought landing. The completed form was handed to officers and, if they were happy with the declaration, the passenger was landed. If not, questioning followed. Seamen who went ashore or sought work on other ships were issued with permits to land.33

Passengers could be asked to furnish proof of money and ability to write, while workers who claimed exemption had to have a certificate signed by the agent-general of the Colony in Britain or by an officer appointed by the British government. An example of a suitable contract was drafted. Those who claimed domicile had to prove it before leaving the Colony and procure domicile certificates. Rules were issued on how domicile should be gauged and what format the domicile certificate should take.34 This produced much paperwork including police reports to verify details and statements of biography.35

The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1904 produced yet more paperwork. It prohibited all Chinese immigration to the Cape and required the registration of the 1,380 Chinese within the Colony. Resident Chinese over the age of 18 had to secure certificates of exemption renewable annually. Those wishing to leave and reenter the Colony had to secure a Governor's certificate that indicated their right to reside in the Cape. 36

In 1906 an elaborate permit system began, devised by the Cousins administration and unique to the South African colonies. The 1906 Immigration Act exempted any 'Asiatic' who secured a permit allowing a temporary absence from the Colony. While these permits were primarily for Asians (Chinese permits were also issued under the Chinese Exclusion Act) and was required for reentry, whites were also issued with them for 'their convenience'.37 The Immigration Department thus became instrumental in racialising residents of Cape Town by creating different types of permits and filing them separately. As Jane Caplan and John Torpey have argued: 'the documentary apparatus of identification itself has driven the history of categories and collectivities'.38

Discriminatory practices prevailed from the beginning. When whites secured a domicile certificate they were not photographed and fingerprinted; yet the certificate carried a special section providing for the thumbprints and detailed physical description of Asiatics and Persons otherwise difficult to identify'.39 Melanie Yap has written about Chinese being stripped and searched for marks for registration purposes.40 There is no indication that Indians were stripped when applying for permits but facial marks, height and other distinguishable features were noted.41 While the permits issued to whites did not bear photographs and thumbprints,42 these were mandatory for Indians. Madeirans came the closest in treatment to Indians: their permits bore thumbprints although not photographs. Their illiteracy and darker complexions contributed to their ambiguous status and their suitability as immigrants was questioned.43 Processing applications for permits became one of the major occupations of clerks in the Immigration Department. Permits survived into the Union period; under the Immigrants Regulation Act of 1913 they were renamed certificates of identity. A Cape requirement thus became national in application.

Cousins refined the passenger arrival forms, creating a standard form in 1906 instead of the cumbersome choice of four forms used previously. The new form of 16 questions, which its designer described as 'a form of "inquisition,"' was designed to secure information about the passenger to establish whether they would be allowed entry or be barred. It survived unchanged for several decades. Cousins was proud that 'something like half a million completed forms, sorted in alphabetical order, and bound existed in Cape Town when I left - an interesting and valuable record of every man, woman and child who had come to South Africa through a port of the Cape Province - a veritable gallery of autographs of notabilities, ordinary folk, nondescripts and undesirables'.44 Cousins' extensive paper archive was racially segregated for whites, Indians and Chinese.45

The passenger form of 1906 was issued under the header of the shipping line that individuals travelled on. It required the name of the ship and the class the passenger travelled. In small print it carried a warning that 'any person knowingly giving false information, or making a false declaration, is liable to penalties of fine and imprisonment'. At the bottom of the form was the signature of the master of the ship or other officer certifying that he had witnessed the completion of the form and that the declaration was a true one. Among the questions the passenger had to answer were names, race (a choice of European, Hebrew, Asiatic or African was given), age, port of embarkation, port of destination, sex, nationality, whether accompanied by children under the age of 16 and their names and ages, previous period of residence, address in Cape Town, evidence of financial means, whether able to speak a European language, health and criminal record and whether prohibited previously. On the side of the passenger form there was a column for comments of the immigration officer where extra information such as documentation possessed could be noted. The immigration officer initialled and dated the form. If an individual was not passed, a prohibition notice was issued.

The passenger form provided the first encounter with immigration officials and provided some discomfort to all. When it began there was much discussion in public forums on a question relating to prostitution that offended the white respectable class and this was later removed. 46 After 1911 passenger forms completed by Indians bore their thumbprints. Under the Immigration Act of 1913 the passenger form had the Union of South Africa Immigration Department as the header instead of the shipping line but was otherwise the same.47

Cousins provides a taste of what happened when a ship arrived at Table Bay and officers boarded it after taking a tugboat from the shore:

Picture the smoking room on one of the Union Castle intermediate boats - with some 200 third class passengers, enough to give the two examining officers a busy two hours of work. The passengers come in by a regulated stream through one door, pass before one or other of the officers and out at the other door: except that here and there a doubtful case is detained for a more leisurely examination later on where there is time ... There are of course other things to look for than signatures to declarations or answers to stated questions. The experienced officer has for example to possess an instinct of all sorts of possible disqualifications which the passenger's papers will not reveal.48

One officer, in Cousins' recollection, was 'almost uncanny in his detection of defaults - material, moral and physical'. This is consistent with Robertson's findings for American immigration that what the official eye saw in taking in the passenger's body, appearance and demeanour was actually more significant than the paper they carried.49

There were others also present on ship and at the docks - interpreters who assisted passengers and officers. Indians in Cape Town encountered Abdol Cader, a businessman in Long Street and secretary of the British Indian League. The Reverend Abraham Weinberg, a rabbi of the Great Synagogue in Cape Town, often interpreted for Jewish immigrants from eastern Europe.50 Cape Town was one of the busiest of the Colony's ports. Passenger traffic in 1907 and 1908 was between 1,400 and 3,700 per month while numbers for Port Elizabeth and East London did not exceed 270. In 1908, 22,814 passengers arrived at Cape Town from ports outside the Colony, and more than double that from ports in the Colony. New immigrants numbered just 5,631, the majority being returning residents.51 Passengers had to be examined and processed rapidly before being allowed to land.

Narratives of Arrivals of Young Males

This section discusses the encounters of youth of different races with immigration officials. What follows are accounts of arrivals drawn from the passenger forms and immigration files of three young males: one Greek, one Indian, one English.

John Faros arrived from Port Said in April 1909. His father Domestrios, a fruiterer, had been in the Cape for seven years while his wife lived in Greece with five children. John's answers on the passenger form indicate that he did not have money on him but that his father would bring it to the docks. He could write Greek. His answer that he was 18 years old conflicted somewhat with his father's intimation to the immigration authorities a year earlier that he was 15 years and nine months old; ages were of significance since 16 marked the end of minority status. The immigration officer noted in the comments section: 'never in colony before. Friend of father in Durban wired him to bring money on board ship. Father states permit issued 10 mos ago & sent to boy who has lost it. Writing is good. He was officially landed on 26 April; if asked about his age or proof of age, these were not noted. His passenger form was filed in a brown folder that held his father's earlier application for a permit for him.52

In September 1909 Woolf Shure arrived in Cape Town on a ship that had set out from Southampton. His form indicated he was 12 years old, he could write in English and he was going to join his uncle. The immigration officer noted: 'Parent in London. No money. Born in England. Going to uncle who is known as a respectable man. Uncle met the boy and took him off to his home.' Woolf's entry was unproblematic and he went to stay with his uncle in Wynberg.53

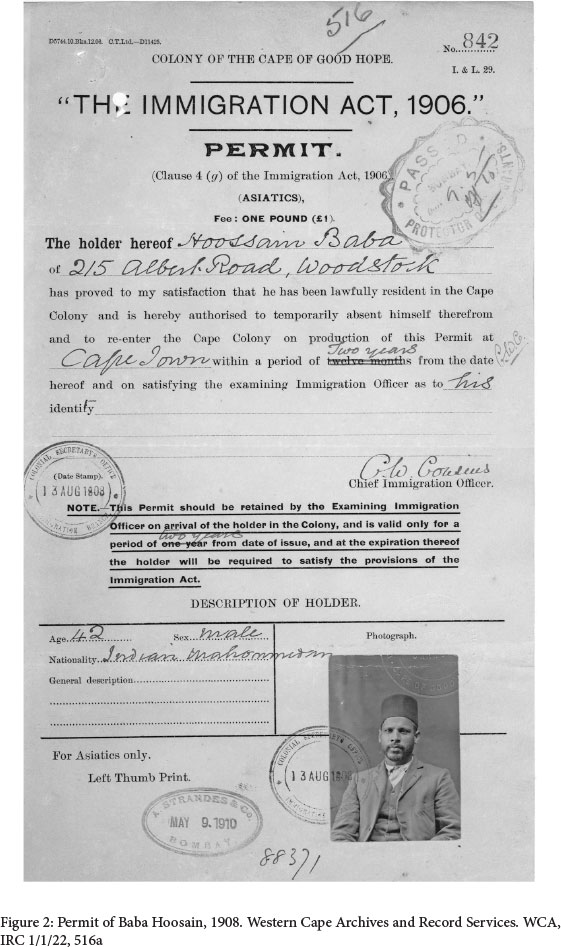

Ibrahim Hoosain, aged ten, and Mahomed Hoosain, aged 15, came to Cape Town in June 1910 accompanied by their father, Baba Hoosain, a general dealer of Woodstock.54 Two years previously, Hoosain had established his own identity and rights with the Immigration Department before setting out for India with a permit (see Figure 2).55

He had then indicated that he had two sons in India. His passenger form provided the names and ages of his two sons accompanying him. At the first port of call, which was East London, the immigration officer noted: 'Certs attached. For further investigation in Capetown.' In Cape Town it was noted that Dr Roscoe, the port medical officer, was 'of opinion Mohamed is over 16'. The immigration officer Willem van Rheede van Oudtshoorn noted: 'Father passed. Boys must wait.' (See Figure 3.)

These certificates that Baba Hoosain had been required to complete for each son in India had been devised by the Cape Immigration Department in 1908. They were a 'form of certificate' that was required to be presented to the deputy commissioner, magistrate or collector of the district in India with the stipulation that 'no signature of any subordinate official will be accepted.' The certificate carried a qualification, that it 'will be accepted as prima facie evidence of the facts stated, but does not in itself confer any right on the holder to enter the Cape Colony.' Mahomed Hoosain's form was completed by the chief kazi of Bombay (a justice of the peace and an honorary magistrate) in May 1910, rather than the stipulated officer of the district. He certified that he had seen the boy and was 'satisfied' that he was the son of Hoosain, and that he was 'not more than fifteen'. The boy's thumbprints were affixed to the form, as was the kazi's seal and signature (see Figure 4).

What followed was a separate questioning of all three males about names, ages, and family members. Where these corresponded, the immigration officer placed ticks. This was later typed and differences in statements were noted. Mahomed indicated that his mother had no siblings; the younger boy indicated that his mother had one brother; Hoosain indicated that his wife had a brother and a sister. While both boys identified their father's brother by the name of Bawa, Mahomed indicated that Bawa had no children, Ibrahim indicated that he had one son, while Hoosain said his brother had several children. The role of the interpreter is absent from this record; all we have are the English notes.

Despite these discrepancies, the chief immigration officer accepted Hoosain's statement that these were his sons and approved the landing of the younger boy but called for medical opinion on Mahomed's age. E. N. Thornton, the additional MOH who had once served as a medical officer in the Punjab, examined Mahomed on 21 June 1910 and concluded he was over 16, providing little elaboration as to how he had reached his decision. Mahomed then went for x-rays on 7 July, taken by Geo Robertson, the government bacteriologist, who concluded he was over 16 on these grounds: '(1) The upper epiphysis of the ulna is united to the shaft of the bone; (2) That the lower epiphyses of the humerus have blended and are united to the shaft of the bone.'

Mahomed had, in the interim, been thumbprinted and issued with a temporary permit that kept him out of the detention depot, which by some accounts was not a good place to be.56 While he awaited a decision, he reported monthly to the Immigration Office. Three months after he first arrived, Mahomed was deported. The immigration officer at Cape Town telegraphed the East London officer that the ship, the Burgermeister, carried the deportee Mahomed. This was a precaution to prevent an escape at a neighbouring port, for there had been daring escapes before57 where youths disappeared in the world of the undocumented and reinvented themselves.

The above three accounts are revealing. Both Domestrios and Hoosain had left a wife and children in Greece and India respectively and both sought to introduce sons. There were few questions asked of John Faros; it did not seem to matter whether he was 15 or 18, for John could write in a European language and had a father to receive him. There were no elaborate testimonies to prove his relationship to Domestrios and the immigration officer did not note what identity documents he produced to indicate that he was the son. The records of white passengers arriving to join family do indicate that entry was dependent on 'satisfying the Examining Immigration Officer as to ... identity'.58 In one case it was specifically written that the wife of a resident and their children aged six and 18 who all resided in Kelem in the province of Kovno in Russia could enter 'on production of documentary evidence of age.59 Yet the records of such passengers do not reveal how identities were established. These people most likely carried birth and marriage certificates. In America, immigration officials were faced with numerous cases of Jewish immigrants falsifying their relationship histories60 but the Cape archives do not reveal official concerns. In contrast, the Indian files burst with details on the verification of personal relationships and ages.

Not all young white males secured easy entry. Sons generally did, but other males would be subjected to a writing test and have to provide evidence of financial means. The immigration papers are full of trauma that these two requirements produced. Woolf Shure escaped the gruelling questioning that many older Jewish males experienced, perhaps because of his really young age, his ability to write in English, and the subjective assessment of the officer about his uncle's status. As it turned out his stay was short: his uncle found him to be dishonest and his behaviour reprehensible. After investigation into Woolf's moral lapses, in particular the allegations of bestiality, Woolf was deported from the Colony 'as an undesirable' at the Colony's expense on the recommendation of the resident magistrate at Wynberg.

The reality was that immigration officials spent an inordinate amount of time on Indian arrivals, few as they were.61 Cousins justified the differential treatment:

It is not possible to deal with the Asiatic as with the European; the whole nature of the man is oriental, his habits are different from those of the European, and legislation that would apply easily to the European is not applicable to the Asiatic; and that is one of our difficulties with the Asiatics and Europeans - they are both dealt with under the same law, and so a great deal of discrimination is necessary in administering the law.62

The Indian, in his view, was someone not committed to the Colony: he maintained a family in India with earnings from the Cape.63 Cousins was not wrong in this understanding, for the majority of Indian males favoured circular migration with a return to India always prefigured. In the early 1900s, Indians in the Cape were predominantly male,64 with women arriving more significantly from India in the 1920s and 1930s. Cousins thus expressed the view: 'I do not think it would be a hardship, where the Asiatics are not settled here, if these minors were excluded altogether'. For a while, the minority age for whites was also administered as being 21 instead of 16.65

Mahomed's deportation at his father's cost has all the ring tones of tragedy - a young boy separated from his father and brother and humiliated by procedures to establish his age. We can guess at the anxieties the delays in confirming his landing produced. Yet six years later there was a twist to the story when Hoosain, who sought to bring out his real son, confessed that neither Mahomed nor Ibrahim were his sons. An official shortcoming here was that, while Mahomed was deported because of age, the department was unable to disprove Hoosain's insistence in 1910 that these were his 'sons'. The certificate from India was incorrect in several points of fact. All it did was record what the kazi was told was the 'truth'. The passenger form that warned of penalties in the face of untruths remained just that, a warning.

Female children of resident Indians only began to arrive in significant numbers after the 1920s, when a more settled family life began to develop. The ages of female arrivals as wives and children occasionally caused a stir in the Immigration Department if there was a suspicion the arrival was a child bride.66 The introduction of 'sons' became an issue because it was linked to the desire of shopkeepers for shop assistants. Representations were made to the authorities to allow shop assistants to come from India under a contract of indenture with assurances of their return to India.67 Many Jewish and Greek shopkeepers applied for family members (nephews, brothers, sons and daughters) to come out to help them in their businesses and, provided that they could write, these applications were granted.68 Shop owners - Jewish, Indian, Greek and Portuguese - wanted people who spoke their language, who understood the nature of their business and whom they could trust. Indian shopkeepers sought to return to India for a while and leave the business in the hands of relatives. The village and extensive family network was what was trusted. With the impossibility of meeting the colonial requirement of a literacy test in a European language and the complete post-Union ban on Indian immigration, they brought in young boys as sons.

As a consequence of the 1906 Act, which reduced the age of minors from 21 to 16, the flow did not stop but led to many trying to pass for below 16. Very young boys were also brought in and once they passed the immigration barrier they worked as shop assistants. Cousins was not off the mark in his description of these arrivals as literally 'indentured servants'.69 Shamsodien Casimali, an interpreter at the courts and Indian politician, expressed the opinion that '90 percent [of sons] are bogus ... if you allow people to come in as servants ... nobody will try to bring in bogus children.' 70

The joint family system in India also meant that many individuals took responsibility for brothers and nephews and the Cape provided an escape from the village. Indians who applied to bring in brothers or nephews were not permitted to do, no matter the reasons advanced.71 Pama Govand appealed in 1906 through attorneys to bring his 12-year-old brother since both parents had died; but the immigration officer commented, 'An old story', not believing either that the parents were dead or that the boy was a brother.72 Bhika Valli was prohibited on arrival in 1907 when he told immigration officers that he came to join his brother Moosa Valli. Within 16 days he was on a ship bound for India.73 The attorney, Alex Dichmont, appealed unsuccessfully in 1910 on behalf of Kazi Kootboodien of Observatory to allow his 14-year-old brother to come since he could not find suitable shop assistants for his two shops. He had taken financial care of the boy in India for five years and intended to 'indenture him'. Once the period of indenture was over he would send the boy back.74

We have to contrast these refusals and the attitude of immigration officials to appeals made by Jewish and other residents in the Cape. Davis Myers had no children and wished to adopt his 14-year-old nephew, who lived in Russia with his parents. The young boy arrived with little problem in 1911.75 Saki Berkowitz of Tulbagh successfully brought out his 12-year-old brother from Russia to give him an education.76

Grandsons came as well.77 These boys could all write in a European language. While white immigration was encouraged (subject to the writing test), an end to Indian immigration was sought.

Cousins admitted: 'I have consistently refused applications from Indians to bring their brothers to this country'. Yet he also pointed out that he was 'quite aware that a large proportion of the socalled sons who come here are probably only brothers or possibly stand in no relationship at all'.78 Cousins, who accused Indians of being naturally prone to lying, himself provided a clear explanation for why lies happened. There were public admissions by Indians that youths passing for sons were arriving; immigration officers knew this and thus immigration encounters of young males became about officials trying to disprove relationships and minority status - in this regard documents from India became a central issue.

Documents from India

How do you´ know you are 15 years of age? - I have my age written in a book.

Have you a birth certificate? - No.

You know that is your age because your father and mother told you? - Yes.

(Jekoomull Daroomull, shop assistant, 1908) 79

It was not unusual for young boys to tell immigration officers that they were a particular age because their father had told them so,80 or that they did not know when their birthday was. One father had this to say: 'I am not really sure how old he is. I did not keep any record of his birth. The date has not been registered anywhere.'81 Macwa Baba pleaded to immigration officials:

My wife died a year ago in India. I have only one child, a boy Ibrahim Macwa, aged fifteen years, who arrived yesterday on the SS Windhuk. I did not make any record of the boy's birth, and I do not know the date of his birth; but I believe him to be only fifteen years of age. I am speaking the truth; I have no documents but I ask the Government to take my word.82

One could attribute such statements as deliberate attempts to conceal but at the heart of it lay the issue of lack of a birth certificate or birth registration. In the absence of paper, how could relationships and ages be assessed in Cape Town?

Unlike Britain, where individual identification was captured from as early as the sixteenth century,83 Gopinath84 has noted that in pre-colonial India there was little concern with registration of individuals and this also characterised British rule. He notes 'the apparent contradiction between the colonial Indian state's encyclopaedic attempts at statistical recording and the absence of individual identity registration. The colonial government while counting and recording virtually everything from people to property to natural resources somehow did not feel the need to register individual identity.' Various provinces made attempts from the mid- to late nineteenth century to register births and deaths but these were not compulsory. Legislation in 1888 provided for the voluntary registration of births, deaths and marriages throughout the country but Gopinath observes: 'Indians neither felt the need for such registration nor understood the practice.' Registration would improve in the early twentieth century but individual identity was never a major concern of the state. In villages residents knew one another; there was no 'need for an identity register'. The state itself taxed villages not individuals and was dependent on 'group categories', an individual's membership of a caste, a race and religion yielded 'sufficient identifying attributes'. Kamal Sadiq has painted an equally poor picture of documented personal identity in current-day India and observes that celebration of birthdays is a contemporary phenomenon.85

In their encounter with the documentary state in South Africa, Indians encountered a new system requiring fixed names and fixed dates, and Hindu and Islamic calendars required translation. Immigration officers in Cape Town in 1905 asked fathers wanting to bring sons to secure documents from magistrates or even a principal of a school that certified ages and relationships.86 In the early years, especially from 1903 to 1907, the officials did not insist on documents. Cousins, not known for liberal or sympathetic views, voiced his concern in 1906 about 'the difficulties one has in disproving the statements made by Indian immigrants and also the hardship that might be caused were one to insist upon absolute evidence documentary or otherwise'.87 This was a rare admission of how emotive considerations played a role in implementing policy.

In the absence of documents, the Immigration Department accepted sworn statements from the father and from people in Cape Town who knew the father and son. Jamal Sallie's father, a barber in Claremont, prepared the ground before Jamal arrived in 1907. He made a sworn declaration that his wife had died recently and that his son was fifteen and a half years old. Three individuals in Cape Town, hailing from his village Abrama, confirmed that these facts were true. On arrival, Jamal simply made a sworn statement of his biographical details and was admitted. The immigration officer did flag the question of his age: 'the boy looked older than 16. But one cannot of course declare that he is older.' The sworn statements sufficed as proof.88 While a form of certificate was devised n 1908 for completion in India, Lala came in 1909 without this because the officer was quite a distance from his home and it would have cost him about 40 rupees. After two of his father's friends, whose homes in India were but a few miles away from Lala's home, testified that they knew Lala and his father, Cousins sanctioned his entry. Almost two decades later, Lala confessed under a condonation scheme to being no relative to the said 'father'. This again proved the weakness of the department, in accepting sworn statements and being unable to disprove Lala's identity.89

The second way of verifying relationships was by checking narratives, as seen in Mahomed's and Ibrahim's case above. When Bhaga Ratanjee (fifteen and a half years old) arrived in February 1907 he stated that his father was Ratanjee Wassanjee, a barber; his mother had died six or seven years ago; he had no brothers or sisters and he lived in India with his uncle. He was admitted after his father independently stated the same details. While Cousins expressed doubts about the boy's age, his verdict was: 'Give the benefit of the doubt to the boy & pass him.' Eight years later, when Bhaga sought to go to India, the Immigration officer observed that 'the applicant made an easy entry originally . I suppose we can do nothing now. He is an old looking 24.'90

The checking of relationship narratives did exclude some 'sons'. The 17-year-old Fakir Mohamed Desai was denied entry in 1905 because he indicated that his 'father' had no other sons, while his 'father' indicated that he had two sons.91 The 15-year-old Gopal had a close shave in 1907: his father had said that he was living in India with his mother's mother Wallie, but Gopal did not know who Wallie was. But the immigration officer, Van Oudtshoorn, who had a colourful history in the department when he faced charges of corruption and facilitating the illegal entry of Indians, excused this with the comment, 'boy was probably confused. All other statements agree.'92

The interrogation of minors in Cape Town pales in comparison to the rigorous questioning of Chinese children who entered America, where officers asked specific questions about the village, house and even got children to draw diagrams. Paternity was also established in America by looking at whether the physical features of the father and children matched, and the behaviour of all the parties.93 Cape immigration records do not reveal that physical features were compared but, while the official's reading of emotive behaviour was not noted, it may have played a role.

McKeown's point that systematised immigration encounters led to a 'ritual', and Chinese entrants came pre-prepared with coaching,94 is true for the South African context too. Shaik Dawood was sent a letter by his uncle giving him a list of questions and answers.95 Hassan explained how Essack's letter from Cape Town, which enclosed his shipping passage, also told him to say his mother was dead and that he last saw his father six to eight years ago in India.96 While Cousins asked his officers to avoid set questions,97 the variety of questions that could be asked was limited. Ebrahim Norodien, a prominent merchant in Cape Town, also explained how 'fathers' and 'sons' recognised each other at the docks: they had, by prior arrangement, to display handkerchiefs of a certain colour.98

While the 1908 form of certificate led to many arriving with these forms, the holders ignored its provision of who should actually sign the document and went to officials of their choice. The paper itself could not guarantee entry. Cousins explained: 'I have reason to believe that certain of these magistrates' statement were of doubtful value to me, but it was not because the magistrates would state falsehoods but because the statements made to them would be doubtful, and very possibly the person who appeared before them is not the person who arrived here.' He particularly distrusted junior magistrates.99 His successor, E. Brande, was more explicit about the certificates having to be signed by a first-class magistrate: 'very often they are signed by a third class magistrate, who is usually a coloured official.'100

We know from confessions101 that individuals easily secured relationship certificates from magistrates. Ibrahim arrived in 1913 with a certificate testifying that he was the son of Shaik Ahmed. He was not only not Ibrahim but his own father had never left India. He explained:

I pretended to be Ibrahim . and I called myself this name when I arrived in Cape Town. I was with Shaik Ahmed when I got the document from the magistrate. My mother died some years ago when I was quite young. I was brought up by Ibrahim Abdulla's mother. My great aunt, she arranged for me to get the certificate from the magistrate and instructed me to say I was Ibrahim . and that my father was Shaik Ahmed who was in Cape Town.

He paid Ibrahim Abdulla a sum of £5 to ensure his entry into Cape Town.102 Oral histories confirm that certificates were easy to acquire in India.103 There was also a network of support in Cape Town that facilitated illegal entry for cash. In one case an agent created a certificate by making up the name of the first-class magistrate in India and placing a seal on it that was very close to the original district seal. Artistic creativity, however, did not extend to forging an extract from the village birth register.104

To ensure that the boy who appeared before the magistrate was in fact the boy who arrived in Cape Town, the Immigration Department later asked that not only thumbprints but also photographs be affixed to the certificate. This could also be subverted. Sometimes the photo would be added after the boy had seen the magistrate. Allie, who arrived in Cape Town in 1913, indicated after much questioning about his status in 1913: 'My uncle Hoosain took me to be photographed ten days before the steamer started. I have been to a magistrate in Ratnagiri about two weeks earlier.'105 The 14-year-old Cassim had his thumbprints taken when he appeared before the dewan and district manager of Janjira in 1912. His certificate established that he was the son of Shaikh Hassan. After his and his 'father's' narratives corresponded, Cousins noted: 'This seems to be a perfectly straightforward case. Let the boy land.' Three years later, however, someone who knew Cassim spilt the beans that Cassim was actually Gaffoor and was the son of Kajee. Cassim/Gaffoor was deported in 1915. Here lay the weakness for new arrivals: village networks could secure an entry but they could also lead to exposure.106 Individuals who assisted in bringing young boys had to be paid off and sometimes, many years later, there were attempts at extortion.107

Goolam was a young boy of nine when he came with a first-class magistrate's certificate and his thumbprints on it in 1909. For three years he lived peacefully in Cape Town until several people who had grievances against his 'father' (who was in fact his uncle) informed on them. The commissioner of police in Bombay was tasked by Cousins, who forwarded Goolam's photograph, with obtaining evidence of Goolam's family history from his village Furus. Goolam's real father claimed that he had handed the boy over to his brother when Goolam was five days old but the religious ceremony sanctioning the adoption could only be done when the boy was 18. Despite pleas by the uncle to allow his nephew to remain, the 12-year-old was deported after spending some time in the detention depot.108 (See Figure 6.)

After the Union of South Africa was established, the Immigration Department in Cape Town, one of three departments in the country, fell under the Department of the Interior and the principal immigration officer reported to the secretary for the Interior. The new procedure most commonly used from the post-war period onwards was for fathers to complete a D.I. (Department of Immigration) 90 form locally, and only after this was checked were magistrates in India contacted by the principal immigration officer to secure the completion of a D.I. 91 certificate (see Figure 7).

After the Cape Town agreement of 1927 was concluded between India and South Africa and Indian government assistance was offered, communication occurred via the commissioner of Asiatic affairs in Pretoria with officials in the government of the Bombay Presidency, who then communicated with district magistrates. The new routine did away with the practice of individuals choosing their own officials and thus ensured greater control. This marked a crucial change from the pre-Union practice, where officials did not communicate directly with officials in India. The thumbprints affixed to the D.I. 91 by the minor in India were checked on the minor's arrival at the South African ports.

By the time the D.I. 91 certification process was introduced, the department had secured a significant amount of biographical information about fathers from their applications for permits or certificates of identity. These provided information about the wives and their children and their ages, and consistency there was necessary. If the applicant's D.I. 90 form did not tally with details provided earlier, then the D.I. 91 request would not even be sent to India. Ariff's application in 1918 for his son Ebrahim, aged 13, failed because he had indicated that he had no children or wife in 1907; further, Ebrahim could not be 13 since his father had been in Cape Town in 1905 when he was reputedly born.109 Abbas had on three occasions said he had a son Allie, but over time he provided different names for his wife: Halima, Ayesha and Rabia. He confessed after questioning: 'I must have given three names as I forgot the name of the woman I first said was my wife'. As for Allie: 'he was the son of a friend of mine and he asked me to bring the boy to South Africa.' 110

The system of direct communication with officials in India worked better for South African officials. Suliman first indicated in 1918 that he had a daughter Fatima, aged five. Six years later he claimed he had three sons aged 11, five and three. Questions revolved around the 11-year-old son who had not been disclosed in 1918. His explanation was that 'the child was born whilst he was in South Africa & the letter informing him of the birth was not very legible & he read the word "larka" [son] as "larki" [daughter]'. He discovered he had a son when he visited India between 1918 and 1921. The D.I. 91 form was despatched to India for enquiry and the district magistrate at Kolaba was asked to clarify the identity of the first child. After checking, the magistrate reported that 'the first class Magistrate [at] Janjira found that the boys presented by the applicant were not his sons but were the sons of his relatives. The applicant has no son. He has only one daughter about 6 or 7 years old.' 111

Ismail had consistently listed Abdurahman as his son and sought to bring him to Cape Town in 1921. This, as well as Suliman's disclosure of other sons as above, could be regarded as slot filling to ensure a later arrival, a practice used by the Chinese in America.112 Ismail's plans turned awry when the D.I. 91 form was sent to India for enquiry. The magistrate, R. G. Gordon of Kolaba, found that Abdurahman was the son of Ismail's brother-in-law and that, while the latter claimed to have 'given' the boy to Ismail, the D.I. 91 certificate could not be issued just on this statement.113

The most significant change introduced by the Department of the Interior came in 1927, when it was stipulated that any minors seeking to enter the Union from India had to be accompanied by their mothers. This strategy played a significant role in reducing the number of 'false' sons. A rigorous procedure involved oral testimony from fellow villagers, who were required to verify the photograph of the applicant and provide details of his wife and children. Oral statements were converted into written transcripts, translated and despatched to South Africa with supporting documentation such as extracts from birth and marriage registers (see Figure 8).114

The D.I. 91 process allows us some insight into record keeping in India: birth and marriage registers were produced regularly through the 1920s and 1930s, pointing to greater compliance with requirements in India. The Muslim record keeper of marriages in the villages of Kadvai and Chikli, however, claimed in 1937 to have a record of marriages for the two villages dating back to 60 and 70 years, and he was heir to his father's record keeping. Indigenous record keeping practices clearly need greater attention. Yet at the same time Bawa of Ratnagiri had difficulties producing a marriage certificate since the kazi who performed his marriage was dead and there were no papers.115 As late as 1944, there was frustration with documentation from the district of Shrivardhan, Janjira State, where dates of birth were not produced from state registers but from 'the diary of the household'. The illiteracy of the village patil (official) was blamed for this.116

There was still room for falsification despite these procedures. As Dr Mahate indicates for Kalusta village: 'They had an arrangement - right - if it's a boy it will be registered in my name. And none of them were caught out ... you know the investigation will go to India and they said no this is his son. You can't dispute it. There was no DNA.'117 These are most likely the 'parcel babies' that Parker, the Kalusta village historian, has referred to. Relationships were one part of the story, ages another, and the Immigration Department became more decisive about sending away so-called minors.

Establishing Ages: The Medical Evidence

There is always trouble with the age of minors. Sometimes the minors are very tall in stature, while others are very small . If we say one of the tall ones is not yet 16, the Immigration Officer says he is 24.118

As in the cases discussed earlier involving Jamal Sallie and Bhaga Ratanjee, while the department had doubts they were unable to disprove ages and let these individuals in. Boys over 16 prepared for the immigration encounter by shaving off beards and moustaches.119 Cousins explained how he had seen a boy on arrival, and then on meeting the same 'boy' walking in Adderley Street he observed, 'his moustache and beard have grown, he seems to be quite 24 years of age.'120

We have some insight into how the immigration officer felt about his task at the Cape Town port, for Cousins kept a diary when he spent several months in 1912 as acting principal immigration officer in Durban, where issues were similar.

Twice yesterday morning I have had a most strenuous time of it. The monthly British Indian boat arrived with about fifty Indians claiming to land here. The enquiry into each claim . requires patience and persistence. I went straight on till 9.30 last night; started again at 7 o'clock this morning and kept up till tea time & am now off again. Failure to go fully into each case makes me liable to be hoaxed, and puts me at a disadvantage when the lawyers get to work. So far I seem to have "bowled out" about 10 of them. One is a youth of about 20 years bringing a Magistrate's certificate from India that he is 12 years! Fortunately for the Magistrate the thumb impressions are those of some other boy and not the one who has come. A third turns out to be an "adopted son" . A so-called father produced a boy of 10 years - but as his wife had never been here, and as he lived here for 14 years continuously and only went back to India 4 years ago, he found me unbelieving. Can you wonder? The story of yet another boy as to his home, his brothers and sisters is wholly inconsistent with his father's story. And so the thing goes on in intricate and bewildering falsehoods, making it almost impossible to get at the truth.

It may sound simple enough but you have no idea of the persistency of my questioning before I really get at any circumstances upon which to decide a claim. I feel utterly exhausted.121

Cousins was aware, while heading the Cape Town office, that if they were to counter claims to age they needed convincing evidence. In 1908 the Supreme Court of the Cape threw out the department's prohibition order against several youths. While Cousins was of the firm opinion that the boys were in their twenties, the problem for the department as stated by Cousins was that 'they could get opinions in plenty, but it is extremely difficult to get any definite disproof.' Four doctors confirmed the Immigration Department's suspicions, while seven doctors gave opinion that the boys were under 16.122

While Daya Lalloo's certificate from a second-class magistrate indicated he was 16, his father indicated that he 'thinks he is 16 - 2 months short of it.' Dr Thornton examined Daya in 1909. We do not know the nature of the examination and what Daya was subjected to. Chinese boys in America had their teeth, their genitals, the hair on their body and their physique examined. One example of such an examination report revealed: 'Applicant has 26 teeth. He is a small boy and looks young. Skin smooth and fresh. He has not passed the age of puberty. Genitals very small, I should say that this applicant is about 12 years of age, and not over 13 years of age.'123 In Cape Town there was a focus on the extent of facial hair and whether puberty was passed.124 Thornton erred on the side of leniency in Daya's case: 'I am of the opinion that he is about 16 years of age - probably somewhat over than under, but children of this caste develop more rapidly than most others and it's possible he may be of the age stated namely 15 years and 10 months.' Thus Daya's entry was sanctioned. Four years later it turned out that Daya was not the son of Lalloo and he confessed to being 21 when he entered the Colony.125

In yet another case, in April 1910, Thornton assessed Mahomed, who came with a certificate from the kazi in Bombay, as not 15 but most likely 16 or 17. His 'father' Gaffoor did not let the matter rest here and together with another person who knew the family, as well as the local Imam, appealed to the colonial secretary that the boy was a minor. They 'swore on the Koran that the boy was under16.' The colonial secretary relented and Mahomed remained and worked for many years as a shop assistant for his 'father', only confessing in 1928 that he was not his son. His story points to the kind of pressures on ministers to accept 'fathers'' assertions about their sons with the swearing on the Qur'an about their age - which, as stated, must have been the clinching moment.126

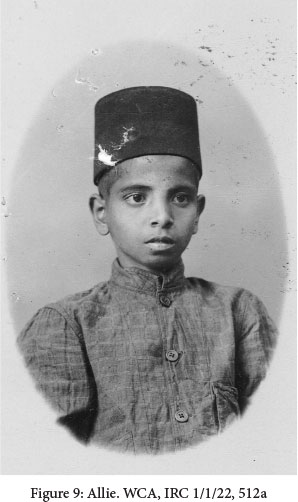

While Allie came with documentation from a magistrate in 1913 that he was 15, his certificate was distrusted.127 In Cousins' estimation, Allie was probably nine or ten; Dr J. A. Mitchell, the assistant MOH, declared the boy was 11 years old at the most. If this was so, then Allie could not be the son of Mahomed, whose immigration records revealed he had been in Cape Town between 1901 and 1908. Mahomed insisted, on questioning, that when he first came to Cape Town in 1901 Allie was either two or three years old: 'I do not know how old he was exactly. He was walking and was no longer in my arms.' Allie was kept in the detention depot but was later given a temporary permit 'for humanitarian reasons' till his 'father' could arrange for someone to accompany him back to India. After some pressure from the father's attorney Alex Dichmont, a friend of Cousins, the latter relented and asked the attorney to secure documentary evidence from India especially from the police patil with whom the father claimed to have registered his son's birth. In addition, the magistrate was to call on villagers to make statements about the family. The father's photograph and the son's photograph were to be sent to the magistrate. Dichmont, the attorney, communicated directly with the magistrate at Ratnagiri but no document was forthcoming. Allie was fingerprinted and left Cape Town as a prohibited immigrant one year after he first landed (see Figures 9 and 10).

Two years later, a magistrate completed the form certifying that Allie was the son of Mahomed and was now 18 years old. This was a futile exercise, since he was no longer a minor and could not enter. If this age was correct as certified, then Allie was 15 in 1913 as originally indicated by his father. If that were so, then the story has rings of great tragedy of a boy who could not join his father. The paperwork renders the separation of truth and fiction impossible.

Doctors had differing views on the ages of the boys. Daya Ramjee of Navsari came in with a D.I. 91 in 1916 where the magistrate had established an exact date of birth, 15 July 1901 (see Figure 11). Despite this valued certificate, the Immigration Department in Cape Town questioned his minority status. Dr Abdurahman and Dr A. H. Gool examined the boy, perhaps at the request of the father. Abdurahman concluded cautiously that Daya 'may be under sixteen years of age', while Gool was more decisive that the boy was under 16. Two other doctors, Dr B. Bernstein and Dr G. W. Bamfylde Danielle confirmed the boy's minority status, though Bernstein did say, 'I am of opinion that his appearance & stature correspond with his statement, although it must be admitted that it is not by any means easy to decide on mere appearance the age of an Indian.' Dr Mitchell, Geo Robertson (the government bacteriologist) and F. C. Wilmot (the additional assistant MOH) all came to the conclusion that he was over 16, while the acting port health officer at Table Bay, P. W. J. Kriel, claimed the boy was over 17. Despite contrary evidence, Daya was prohibited and his appeal against the decision failed. Unlike in 1908, when the Supreme Court ruled in the boys' favour, the new appeal boards established in 1916 changed processes, with the burden of proof shifting to the immigrant.128

While American authorities were reluctant to use x-rays, relying on their own assessments based on appearance, teeth, jaws, and examination of breast bones and ribs,129 South African officials readily used this new technology as seen with Mahomed Hoosain in 1910. Abdulla too was subjected to x-rays when he arrived in 1938, despite having a D. I. 91 certificate that he was 15 with a precise date of birth given as 28 June 1922. It was the ship's surgeon who indicated that Abdulla 'appeared to be over 16 years of age'. On arrival in Cape Town, the government pathologist x-rayed him and ruled that he was 'under 17 years of age and possibly even under the age of 16'.130

All this indicates the extent to which immigration officials distrusted paper from India: even the D.I. 91 certificate would be questioned. They relied on their visual assessments and medical evidence. Yet doctors could not establish with absolute certainty the exact age of 16, the legal transition from minor status to adulthood. In Abdulla's case, the radiologist was also issued with a photograph to ensure that the boy whose elbows he x-rayed was in fact Abdulla, so that no deception took place. An oral interview, 'DC', reveals how some Indians manipulated the medical evidence. The interviewee's brother and another boy travelled on the same ship in the 1930s and her father, an influential leader among the Gujarati Hindus, was told that the other boy was likely to be deported because he was over age. Her father spoke to the official, who indicated they would be examining the boy's bone structure the next day. 'So he said: "Okay, do the bone test. I'll bring him tomorrow". So he took my brother there instead and the guy - to them, Indians all look alike so he tested him . He used my brother to gauge the age so the other guy could stay.'131

Conclusion

This article has focused on immigration encounters beginning with a passenger form and the array of paperwork produced to identify the minor son from India and systems of verification. In tracing the processes from the colonial period to post-Union it shows the bureaucracy tightened up and hardened. In the era prior to Union there was an acceptance that documents from India about ages and relationships were hard to come by and simple sworn statements from Indians in Cape Town were accepted as proof. Officials also documented relationship narratives for comparison. This was far from effective as individuals came prepared and fellow Indians were keen to assist by making false statements. A form of certificate was designed in 1908 for completion in India, yet distrust for the oriental world reigned high and when documents did come they were not readily accepted. There grew a greater reliance on the visual assessment by the immigration officer, which could lead to intense questioning about the truths of the document. The bureaucracy employed photographs, thumbprints, medical knowledge and new technological developments such as x-rays to assist in verification.

Andrew MacDonald has argued with some validity that, for all the border controls erected by various authorities in South Africa, there was 'chaotic incapacity' and 'strategic permissiveness'.132 This examination of immigration records does point to some 'permissiveness' despite repressive systems of paper controls. Some of the 'permissiveness' stemmed from the fact that, if challenged in the courts in the early days, substantial evidence of a false relationship and a falsely stated age had to be provided. There was more 'permissiveness' about relationships but a much harder stand on assessing ages. Yet this article argues that the post-Union saw greater efficiency, tightening of the bureaucracy and the burden of proof shifting to the immigrant. The D.I. 91 certificate and inter-governmental communications eliminated earlier practices where individuals called on officials of their choice in India.

The paperwork, rituals of admission and the stories of deportees point to state power. Yet power was constantly undermined by individuals. Despite the form of certificate of 1908 saying specifically that only a senior official from a district should sign, individuals went to officials of their choice. In one case, a fictional official and forged seal was at play. The boy who appeared before the official in India may not have been the boy who came out; the official in India was tasked with verifying relationships and ages and simply accepted what they were told. Herein lay the flaw of the documentary state in South Africa: the forced reliance on officialdom and paper practices of India. While post-Union systems tightened up, here too individuals thwarted the system by advance planning in India where children were registered under false parents to secure a later admission to South Africa. The paperwork suggests great power of the state in the 1930s and 1940s; yet, as their oral histories showed, individuals could subvert the systems.

A history of immigration paperwork reveals the elusiveness of truth about fathers and sons. Time would show up the inadequacy of immigration officials: the confessions under later condonation schemes reveal that what were considered to be sure cases of truthful statements were anything but that. Time would also be the undoing of immigrants, for their paperwork had to show a narrative consistency and when this did not happen everything unravelled. Immigration encounters and paperwork are a maze of uncertainty. For all the success of the officers in 'bowling out' some, oral histories and community-produced histories confirm that many more had a good innings. That these stories are told with relish says something about the limits of state power.

1 This research was supported by the National Research Foundation but reflects the views solely of the author.

2 N. R. Parker, 'Kalusta for Those Who Don't Know', Kalusta Karjiker Educational Society: 80 Years and Beyond, October 2010, 3-5. My thanks to Fatima Allie for providing a copy of the magazine.

3 U. Ho, Paper Sons and Daughters: Growing Up Chinese in South Africa (Johannesburg: Picador Africa, 2011), 40; [ Links ] W. R. Jorae, The Children of Chinatown: Growing Up Chinese American in San Francisco (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2009), 13. [ Links ]

4 Interview with Ramjee Magan, Cape Town, 25 January 2010.

5 Interview with Abdullah Gangraker, Cape Town, 29 March 2010. In his published memoirs he recounts that his father came as the 'adopted son' of Yunus Dawood Rawat and the exact date of entry was 9 May 1910. He does not mention the adjustment to his father's age, giving his birth year as 1896. See A. Gangraker, Wembley Echoes (Self-published, undated), 6-7.

6 While Parker refers to sisters and nieces arriving as daughters, the immigration records refer only to false 'sons' arriving.

7 See E. Bradlow, 'Immigration into the Union 1910-1948: Policies and Attitudes', vol 1 (Unpublished PhD, University of Cape Town, 1978); S. Perbedy, Selecting Immigrants: National identity and South Africa's Immigration Policies 1910-2008 (Johannesburg: Wits University Press, 2009). Kalpana Hiralal has recently drawn attention to paperwork, yet stops short of moving to verification processes. See 'Mapping Free Indian Migration to Natal through a Biographical Lens, 1880-1930', New Contree, 66, July 2013, 97-120.

8 See A. MacDonald, 'Colonial Trespassers in the Making of South Africa's International Borders, 1900 to c. 1950' (Unpublished PhD thesis, University of Cambridge, 2012), 44. [ Links ]

9 A. M. McKeown, Melancholy Order: Asian Migration and the Globalization of Borders (New York: Columbia University Press, 2008), 269. [ Links ]

10 See V. Bickford-Smith, 'The Impact of European and Asian Immigration on Cape Town, 1880-1910' (Unpublished paper, 1978).

11 See S. Bhana and J. B. Brain, Setting Down Roots: Indian Migrants in South Africa, 1860-1911 (Johannesburg: Wits University Press, 1990), 136, 148; [ Links ] Hiralal, 'Mapping Free Indian Migration, 109.

12 See J. Caplan and J. Torpey (eds), Documenting Individual Identity: The Development of State Practices in the Modern World (Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2001); [ Links ] K. Breckenridge and S. Szreter (eds), Registration and Recognition: Documenting the Person in World History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012). [ Links ]

13 Caplan and Torpey, 'Introduction' in Caplan and Torpey (eds), Documenting Individual Identity, 3.

14 C. Robertson, The Passport in America: The History of a Document (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010), 10. [ Links ]

15 B. Raman, Document Raj: Writing Scribes in Early Colonial South India (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2012), 17. [ Links ] MacDonald and Dhupelia-Mesthrie have paid some attention to fraud in the immigration departments in South Africa. See A. MacDonald, 'The Identity Thieves of the Indian Ocean: Forgery, Fraud and the Origins of South African Immigration Control, 1890s-1920s' in Breckenridge and Szreter (eds), Recognition and Registration, 253-76 and U. Dhupelia-Mesthrie, 'Cat and Mouse Games: The State, Indians in the Cape and the Permit System, 1900s-1920s' in I. About, J. Brown and G. Lonergan (eds), Identification and Registration in Transnational Perspective: People, Places and Practices (New York and London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013), 185-202.

16 K. Sadiq, Paper Citizens: How Illegal Immigrants Acquire Citizenship in Developing Countries (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009), 135. [ Links ]

17 B. Kafka, 'The Demon of Writing: Paperwork, Public Safety, and the Reign of Terror, Representations, 98, Spring 2007, 16.

18 See B. Kafka, The Demon of Writing: Powers and Failures of Paperwork (New York: Zone, 2012); [ Links ] M. S. Hull, Government of Paper: The Materiality of Bureaucracy in Urban Pakistan (Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press, 2012) and Robertson, [ Links ] Passport in America.

19 MacDonald, 'Colonial Trespassers', 10-19. The paragraph draws fully from this source.

20 The population of Cape Town in 1904 was 170,000. See V. Bickford-Smith, Ethnic Pride and Prejudice in Victorian Cape Town: Group Identity and Social Practice, 1876-1902 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995), 11, 130, 126, 129-30.

21 G 63-1904, Cape of Good Hope, Report on the Working of the Immigration Act of 1902 for the year 1903 (Cape Town: Cape Times and Government Printers, 1904), 8, 35-37.

22 Ibid, 29.

23 See E. Bradlow, 'The Cape Community During the Period of Responsible Government' in B. Pachai (ed.) South Africa's Indians: The Evolution of a Minority (Washington: University Press of America, 1979), 143-5; [ Links ] Bickford-Smith, 'The Impact of European and Asian Immigration', 7; U. Dhupelia-Mesthrie, 'The Passenger Indian as Worker: Indian Immigrants in Cape Town in the Early Twentieth Century', African Studies, 68, 1, April 2009, 117-18; R. Mendelsohn and M. Shain, The Jews in South Africa: An Illustrated History (Johannesburg and Cape Town: Jonathan Ball, 2008), 62-3.

24 J. Martens, 'A Transnational History of Immigration Restriction: Natal and New Zealand, 1897-99, Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History, 34, 3, September 2006, 325; also McKeown, Melancholy Order, 193-7.

25 G 63-1904, Report on the Working of the Immigration Act for 1903, 3.

26 A. B. Hofmeyr of the attorney-general's office was the first head for a short while, and E. Brande succeeded Cousins in 1915.

27 Cousins was born in 1872 on the island of Madagascar, where his father was a minister of the London Missionary Society. He was educated in England at Oxford High School and Lincoln College in Oxford, where he read for a degree specialising in modern history. He cut short his studies to work as a teacher before setting sail for Cape Town in 1896. Here he found employment in the public service, first as an inspector of prisons and then as a senior clerk in the local government and health branch in the colonial secretary's office. For his biography see the catalogue of the University of Cape Town Libraries Manuscript Division, C. W Cousins Papers (Cousins Papers) BC 1154 and his published memoirs Reflections of a Nineteenth Century Immigrant 1896-1950 (Self-published, Tzaneen, 1950) in Cousins Papers BC 1154, E4.

28 C 1-1909, Cape of Good Hope, Reports of the Select Committees on the Immigration Department: Reports and Evidence Taken by the Committees of 1907, 1908 and 1909 Sessions (Cape Town: Government Printer, 1909), 87-8.

29 I am currently writing up an account of Cousins' career as Cape Town's Chief Immigration Officer.

30 Cousins Papers BC 1154, E4, Reflections of a Nineteenth Century Immigrant, 6.

31 G 63-1904, Report on the Working of the Immigration Act for 1903, 3-16.

32 Ibid, 16-17, 44.

33 Form A, for instance, certified that they did not fall in the category of prohibited immigrant listed on the back of the form. A second form was for those claiming exemption because they were domiciled, or wives and children of domiciled persons or workers on contract. A third form was for a passenger who sought to proceed by land beyond the Colony's borders. A fourth form was for visitors who did not intend to permanently reside in the Cape. Ibid, 19, 44-7.

34 Ibid, 21-3, 48-52.

35 See U. Dhupelia-Mesthrie, 'The Form, the Permit and the Photograph: An Archive of Mobility between South Africa and India', Journal of Asian and African Studies, 46, 6, 2011, 653, 655-6. [ Links ]

36 M. Yap, Colour, Confusion and Concessions: The History of the Chinese in South Africa (Hong Kong: Hong Kong, 1996), 62-5. [ Links ]

37 For the permit system see Dhupelia-Mesthrie, 'Passenger Indian as Worker', 119-20, 126-8 and 'Cat and Mouse Games', 185202. See also Western Cape Archives and Record Services, Principal Immigration Officer (PIO) 14, 1843e, Cousins to attorneys Stoyan and Osler, 1 July 1910 on permits for whites; also PIO 4, 749e, Note by Cousins, 28 July 1911.

38 Caplan and Torpey, 'Introduction' in Caplan and Torpey (eds), Documenting Individual Identity, 3.

39 G 63-1904, Report on the Working of the Immigration Act for 1903, 51.

40 Yap, Colour, Confusion and Concessions, 65.

41 Dhupelia-Mesthrie, 'Cat and Mouse Games', 187-90. Fingerprinting on permits and certificates of identity were not demanded between 1906 and 1910 but became routine after 1911.

42 There were a few exceptions. Individuals themselves supplied photographs and these were affixed to the back, see PIO 15, 1940e. See also permit of an Italian, Vito Sardo, whose photograph but not thumbprints were affixed on the permit (PIO 19, 2266e).

43 See permit of Manuel Freitas, PIO 20, 2451e. See also C. Glaser, 'White but Illegal: Undocumented Madeirian Immigration to South Africa, 1920s-1970s', Immigrants and Minorities, 31, 1, 2013, 74-98.

44 Cousins Papers BC 1154, E5.2, Lecture given at St Andrews Guild, 1917.

45 These are now the PIO (for whites) and Interior Regional Director (IRC) series with the Indian and Chinese numbered 1/1 and 1/2 respectively.

46 See C 1-1909, Reports of the Select Committees, 1907, 1908, 1909, 96, 180.

47 One change involved the removal of Hebrew as a race.

48 Ibid. The emphasis is mine.

49 Robertson, Passport in America, 164, 168, 176.

50 See C 1-1909, Reports of the Select Committees, 1907, 1908 and 1909, 21. In 1913-15 and 1923 the Jewish Board of Deputies appointed a special liaison officer (Bradlow, 'Immigration into the Union 1910-1948', vol 1, 194-5, 207).

51 G 6-1909, Report of the Chief Immigration Officer for 1908 (Cape Town: Government Printers, 1909), 2-3.