Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Kronos

versão On-line ISSN 2309-9585

versão impressa ISSN 0259-0190

Kronos vol.40 no.1 Cape Town Nov. 2014

INTRODUCTION

Uma Dhupelia-Mesthrie

University of the Western Cape

In 1915 Baba Bapoo, a store assistant in Cape Town, was thrown into a state of great mental and emotional stress when he lost his permit en route to India. This was the only document that could guarantee his re-admission to South Africa. He wrote to a friend to apply for a replacement indicating, 'Since I have made the lost [sic] my heart has turned into madness.' He managed to secure a fresh permit as his application was on record in the Cape Town Immigration Department.1 Osman Vazir was less fortunate - he left for India rather suddenly, in the process omitting to secure a permit. Later, he wrote an impassioned plea from India to the Immigration Department in Cape Town citing all the documents in his possession which proved he had been in South Africa: 'I have got a register of Transvaal, a pass of Free State, a certificate from Gas Co., a receipt for a pass which was received by me in 1907, a card from Somerset Hospital ...' He, however, did not have the right paper needed to re-enter Cape Town. His plea to be allowed in 'with both hands joined, as one to the Almighty and a father' was in vain.2 In the late 1930s, Walter Sisulu was arrested and taken to the Hillbrow police station in Johannesburg because there was 'something wrong with my pass book. After paying a fine he was released.3 The position of African males in South Africa's urban spaces was aptly summed up by a migrant labourer in Peter Abrahams' novel: 'Man's life is controlled by pieces of paper.'4

The above accounts are narratives of the tyranny of paper regimes set up to control movement - whether for travel outside the country or for internal mobility. Colonial states were adept at creating different vocabularies for the documents they devised and imposed on people: passes for Africans, and permits, certificates of identity or registration certificates for others. The lawyer Mohandas Gandhi, for instance, understood that the registration certificate required of Asians in the Transvaal in 1907 was no different from the pass.5 Likewise, the troubled Osman Vazir referred to his permit of 1907 as a pass. At their heart these documents all had similar intent -control and restriction of movement - yet they have acquired separate histories.

This issue focuses on several paper regimes in South Africa, control over mobility being an important but not only consideration of the state. The theme for the issue was, firstly, inspired by James Scott's 1998 monograph Seeing Like a State. Scott introduced an evocative word to describe the imperative behind the workings of the state: 'legibility'. The central goal of the modern state, he argued, was 'to make society legible'; the motivation 'appropriation, control and manipulation'. To know its citizens, the state standardised people's surnames, developed registers for births, deaths, marriages and property, conducted censuses, and surveyed and mapped lands. The paper knowledge this produced represented 'state simplifications'. 'They did not successfully represent the actual activity of the society they depicted, nor were they intended to, they represented only that slice of it that interested the official observer.' Knowledge could be used to tax citizens or to draft them into military service; but Scott did concede that the state's goals could also be in the interest of its citizens. The overall impression, though, is of a controlling state 'manipulating society'.6 In his more recent book on these 'projects of rule, he shifts focus to 'state-evading people'.7 Scott provides the inspiration to examine the paper projects of states in southern Africa from colonial times through to the current democratic era and the responses of those affected by such systems.

It has, however, been 16 years since the release of Seeing Like a State, and the newly published book edited by Keith Breckenridge and Simon Szreter questions Scott's assumptions about the all-knowing state. The editors argue that the 'will to know' has been overstated by Scott for a state need not always be driven by this overwhelming desire to know. Further, they assert, in a direct challenge to the influence of Foucault, that knowledge and power are not intrinsically linked.8 Breckenridge provocatively titles his own chapter on the state's reluctance to pursue African civil registration in rural South Africa as 'No Will to Know'.9 The importance of the Breckenridge and Szreter volume is its firm placing of the subject of registration as a field of academic enquiry. In particular, they urge that attention be paid to the 'the actual workings of registration'. They define registration very broadly as 'the act of producing a written record' commonly involving the production of lists from a broader body of writing,10 while Ravindran Gopinath, in the same volume, defines it as 'the act of listing someone or something by an institution that commands authority and legitimacy'.11 The volume is significant in the attention it gives to pre-modern and non-western forms of registration, thus directly challenging Foucault's genealogy of the 'documentary state' which points to enlightenment Europe.12

Studies of mobility and state identification practices have drawn attention to the dual nature of identity documents. Jane Caplan and John Torpey, in particular, have long raised the question of 'the emancipatory and the repressive aspects of identity documentation'. They suggest that scholars in their 'hostility to the controlling eye of the state' thus neglect how documents can be 'enabling as well as subordinating' and confer 'rights as well as police powers'.13 Recently Ilsen About, James Brown and Gail Lonergan have also reiterated the need to take a 'positive' look at documents of identity by asking what rights they confer.14 Breckenridge and Szreter make a major contribution in the stress that their volume places on the idea of registration as one that, in its recognition of subjects, confers rights. Some of these rights might be social welfare benefits, right to remain in the country, right to vote, right to property. This goes against the central preoccupation of scholars with registration as an act of control and surveillance.15 For South African scholars, these arguments pose a particular challenge given the intrusive controlling nature of the colonial and apartheid state over black people.

This issue on Paper Regimes does two things. It brings together, for the first time, a collection of articles on South Africa that deal specifically with registration. Secondly, several articles are concerned with the documents of identity that arise out of state attempts to control mobility within the country and into the country. In this way it seeks to speak to the significant issues raised by Scott, Breckenridge and Szreter, Caplan and Torpey, and About, Brown and Lonergan. Almost every article has a reference to registration. These may be the nature of opgaaf rolls (household details of people and possessions) or the estate inventories of the Dutch East India Company (VOC) and their difference from, for instance, slave registers of the later British period; the ships' lists recording the indentured passengers arriving in Natal from India; the listing of brand marks on livestock in the Cape Colony; the passenger forms of those disembarking at the Cape ports; the lack of birth and marriage registers in India in the early twentieth century and the consequences for those arriving at Cape ports; the registration of the Chinese in the Cape; the permits needed for border crossings between Mozambique and South Africa; the official lists of prisoners with deportable offences; the listing of Demetrios Tsafendas on a 'Stop List' to prevent his entry into the country; the apartheid population register which culminated in identity documents and the more adventurous Book of Life for each individual; the title deeds registry in the Cape with reference to African land purchases; and the project of the Department of Home Affairs in contemporary South Africa to record asylum seekers and, in particular, to list those from Zimbabwe.

Authors approach the paper systems in various ways. Rather than discussing the articles in this issue in chronological form, the introduction seeks to highlight these different approaches. The articles by Lance van Sittert, Karen Harris and Rosalie Kingwill are significant in that they shift attention from the Witwatersrand to practices of registration in the Cape Colony that affected animals, human beings (the Chinese) and property. Van Sittert offers a challenge to historiography in its focus on the Witwatersrand and the early years of the twentieth century, which have been identified as important in the development of the 'documentary state in modern South Africa'. The aftermath of the South African War (1899-1902), so this reading goes, saw an alliance between mining capital and the state which led to concerted documentary systems, especially that involving the registration of African labour.16 Van Sittert instead draws attention to 'documentary government' in the Cape Colony in the nineteenth century. His narrative provides links between the writing on skin on African bodies (by lashes) and the branding of animals as ways to identify livestock thieves and ownership of animals respectively. Central to his narrative is the Brand Registration Act of 1890, which introduced brand registers whereby the marks on the animals of one owner remained unique to that owner. In this way, marks on skins were transferred to paper. Just as twentieth-century systems transferred fingerprints to paper for identification, Van Sittert argues, so the marks on people and animals were transferred to paper in the nineteenth century. His article thus seeks to draw closer parallels between nineteenth-century systems and the better-known ones of the early twentieth century.

Harris's study of Chinese registration in the Cape, which lasted for almost three decades, draws attention to the reasons for registration. It was the plans to import Chinese indentured labour on the Witwatersrand which sparked off concerns in the Cape about the entry of Chinese, making it an important issue in electoral debates. The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1904 provided a blanket ban on any new Chinese entering the Cape. This exclusion had consequences for those Chinese already in the Colony, for how were they to be recognised and known by the state? Following on Szreter and Breckenridge's urgings to focus on processes of registration, Harris takes us through the paperwork of applications and forms. What emerges from her account is effective state registration of a small population group in the Colony. While she points to the demeaning nature of registration, she also considers the rights that registration conferred (the ability to secure a trading licence or employment, for instance).

Kingwill's study of title deed registration in the Cape Colony provides an understanding of how the idea of private property ownership took hold and how deeds registry offices came to be established in the early nineteenth century. Her article focuses on African freeholders in an urban space (Fingo Village) and a rural space (Rabula); and she takes us on a journey through time when land was acquired by Africans during a period in the Cape's history, from the mid-nineteenth century when there was a brief flirtation with assimilationist ideology through to a period of increasing segregation impulses when African communal landholding was shored up and governed by a separate body of law, customary law. Through deeds office searches and interviews with the descendants of the original titleholders to the freehold land acquired in the nineteenth century, Kingwill makes a significant contribution in probing the meaning that title deed registration has held for those who received it and how, contrary to the basic principles of title deed registration, African families evolved their own practices for the transfer of property over successive generations. While title deed registration was meant to provide certainty about the facts of ownership at any given time, Kingwill finds, following Scott, that registration records failed to capture that reality. Her article explains why Africans freeholders failed to register a transfer of ownership on the death of the landowner, yet nonetheless valued the original title deed.

Breckenridge, who has done seminal work on the registration of African labour and whose work is significant in its analysis of who does the registration, how it is done and the pitfalls of bureaucratic administration,17 provides an analysis here of how the Population Registration Act of 1950 was implemented over several decades of the apartheid era. While in his prior work on the reference book carried by Africans, Breckenridge focused on the Central Reference Bureau (the Bewysburo), in this article we are taken into the heart of the Bureau of Census and the civil servants tasked with capturing the identity of individuals for the census of 1951 and the subsequent process of issuing identity cards. He points to different processes for whites, on the one hand, and Coloureds and Indians on the other. While he acknowledges the success of the identity card project, the story of 'racial registration' took a completely unworkable turn in the 1960s and 1970s. Becoming more confident, the state became more adventurous and sought to replace these identity documents with the Book of Life. Population registration became the administrative concern of the Department of Interior rather than the Census Bureau. Breckenridge introduces us to the imple-menters of this system - the clerks and data processors. The Book of Life, motivated by an overwhelming desire to control, to know its population and place it under surveillance, sought to integrate several registration systems: births and deaths, driver's licences, marriages and gun licences. An overambitious project - the Book of Life was never the success that the identity card project was - most Books of Life remained empty with the requisite information never filled in or updated. It bears the consequence of state 'overreach'. His story is one of a state dreaming the impossible and lacking the means to achieve its dream of total control.

Roni Amit and Norma Kriger's article continues this focus on who implements systems, and how. They look at 'street-level bureaucracy' to understand how the asylum-seeker permit under the Refugees Act of 1998 and the Zimbabwean refugee documentation project initiated in 2010 actually work in the democratic era. Legislation could be passed, but it is the officials at the local level who determine who gets the documents, how long it takes before documents are issued, what records are kept and how these are referenced, filed and recalled. Amit and Kriger highlight the dual effects of documentation (control by the state, and rights accorded to individuals who receive documents). It is this dual effect that produces state 'ambiguity' - how to know but also how to simultaneously limit rights. They take us into the heart of processes which reflect how the quotidian practices by border officials, clerks in refugee offices and permit managers can influence a state project of knowing, which ironically results in greater numbers of undocumented individuals.

The above works thus significantly advance our knowledge of processes, meanings that people attribute to documents, and the limitations of the state. Yet this is not the only way in which we can approach a study of registration. Goolam Vahed and Thembisa Waetjen, examining the registration of indentured labourers arriving in Natal, produce instead a biography of the ships' lists. Their central concern is what happens to the ships' lists over the years, their storage, their preservation, their uses over time, their changing meaning and their changing material form. They tell a fascinating story of how the shipping lists, once housed with the Protector of Indian Immigrants, shifted in the 1960s to the Department of Indian Affairs. Here they lay neglected, the old colonial system of knowledge and control of a bonded working population that produced them now redundant. From here, the story proceeds to a cast of characters who have a mission to rescue the ships' lists, who add to the knowledge contained within them, and some who become driven to understand indenture quantitatively, and others to read it for a history from below. In these many diverse interactions, new histories are produced but the material nature of the lists also undergoes a transformation from paper to microfilm to digital form. From being an archival resource for historians, it becomes publicly accessible through CDs and online systems. In this transformation, its uses evolve and it becomes the means of producing new rights for South African citizens travelling to India with the status of Person of Indian Origin obviating the need for visas, for instance. The political context in which these transformations occur is significant - from the apartheid era of shoring up Indian identity by means of an ethnic university which sought to produce knowledge about Indians to the democratic era with its focus on roots and heritage and to a global project linking Indians in the diaspora to India.

Nigel Worden's essay is in one sense a major lamentation of the fact that slaves were not registered on arrival in the Cape Colony in the Dutch period, unlike the later arrivals of indentured labourers to Natal or the Chinese indentured to the Witwatersrand. While Vahed and Waetjen point to the uses of registration for historians and an interested public, Worden asks how, in the absence of such registration and information, do historians seek to uncover histories of slaves? Worden takes us into the archives of the VOC preserved in the Cape and provides an analysis of what documents of the VOC empire survived through time, who preserved them, what their interests were, how these records have been archived and catalogued and, given the minimal documentation of slaves, how historians have read these archives to produce histories from below. He points to the power of the archives in shaping knowledge, how archival limits are overcome by historians and how, within them, are contained the possibilities of an alternative archive. The democratic era has also seen how the archive can be made more accessible through various online and digitising projects. The digitising of archival collections also involves the politics of heritage management. Worden further points to how slaves understood the power of paper - seeking to destroy documents and simultaneously brandish them during the slave rebellion of 1808. Both Worden's and Vahed and Waetjen's articles thus contribute to a growing body of literature on the lives of archives, historians and their creative engagement with the paper trails, and their value to communities who seek an understanding of their roots.18

Harris's article on Chinese registration, already referred to above, also points to how data recorded for surveillance and control becomes a resource for historians who can gain a better understanding of the Chinese population in the Cape. In Kingwill's article, we have a reference to the mobility of registers over time. Once held in the King William's Town deeds office, the Rabula land titles, 'the black registers', were moved to the Ciskei 'homeland' in the apartheid era. South African archival collections and systems of registration bear all the hallmarks of segregation. These lead to segregated histories, and the challenge for the historian is to overcome the way in which these segregated archival collections produce knowledge that reinforces segregation. It is no longer enough for the historian to read the archive for a social history of its segregated subjects; the historian needs to break the walls and boundaries of these very archives.19

In my own article I attempt to engage with two archival collections, one dealing with white immigrants and the other Indian immigrants - both originating in the Immigration Department in Cape Town but segregated by its initiators, who ascribed racial identities to passengers. These segregated archival collections reveal differences in immigration practices and paper systems. While all passengers filled out a common passenger form on arrival at Cape ports, the Indian immigration series is distinctly different from its white counterpart in terms of the fingerprinting and consistent photographing of Indians, and its paperwork is dominated by questions of how to identify the sons of resident Indians. In the absence of birth certificates and marriage certificates in India, how were Indians to prove their identities? How was the bureaucracy to know who the minor arriving at the Cape actually was? My article draws attention to immigration encounters and paper systems developed to verify the identity of sons of resident Indians. We are taken into the heart of the bureaucratic workings of the Immigration Department, the prejudices of the officials, their distrust of documents originating from India and the certificates and forms that resident Indians were required to have completed in India and locally. The story is one of the limits of paper, a fact that the bureaucracy recognised itself. While there is the underlying thread of the overbearing state common to all studies of South African mobility, my article shifts focus to the creativity of Indians in producing fraudulent paper either by inventing biographical narratives or by engaging in the artistic re-crafting of official paper. The paper systems bear all the hallmarks of power and surveillance, yet the community histories and oral histories reflect a sense of one-upmanship in those who were meant to be controlled and contained. This article makes a start towards breaking archival walls, but there is still room for a much more integrated history of immigration paperwork probing both the similarities and differences in how those categorised and separated by the state were treated and administered. There may well be many similarities between Chinese and the Indian, who are also segregated in separate archival series.

Andrew MacDonald succeeds in crumbling the archival walls in a much more sustained way. He targets the crucial border between Mozambique and South Africa at Komatipoort - one that gained in significance as the South African ports became more efficient after 1915 at keeping unwanted immigrants out. The subjects of his attention are Asians, poor Europeans and tropical Africans all needing the temporary permit to cross into South Africa from southern Mozambique. Drawing on multiple archives, his article provides a narrative of how permits became a valuable commodity that drew people of all races and from different geographical areas into a common project of beating the 'paper walls' at the border. MacDonald also looks at those tasked with ensuring that the paper requirements were met: constables, inspectors, border policemen, immigration officers and a range of individuals - 'native pickets', headmen, conductors, game reserve officials, informers, secret agents - who were to keep an eye out for illegal travellers.

Both my work and that of MacDonald make a contribution to a growing international literature that has drawn attention to travel documents, encounters at the border to identify individuals, and the various systems of fraud at work, for fraud is an inevitable and vital part of any study of identity documents.20 Our work shifts attention from narratives of state repression to creative responses from those forced to engage with state controls. In particular, we draw attention to the border or the port as a space of performativity. MacDonald's study points to a bureaucracy struggling to stem the trade in paper and failing to effectively have the border under total control.

Jonathan Hyslop provides a study of bureaucratic workings in his study of how British and Irish immigrants who were found guilty of crimes in the 1920s were deported. While, as a social historian, he reads the content of the deportation files for the lives of the deportees, his contribution lies in analysing the process of deportation and the movement of files between officials from various sections of the administration -the offices of the police, justice, interior and the premier. Files, as he notes, are what make up a bureaucracy. He points to efficient paper systems and circulation of files. Hyslop also draws attention to the letters of appeal written from the Central Prison in Pretoria and analyses the different strategies deportees used to try to persuade the premier to stay a deportation. This makes a significant contribution to understanding the letter of appeal as a genre. There is much potential in that line of enquiry, as South Asian scholars have so effectively shown in their focus on Indian petitioning.21 Hyslop also looks to the final arbitrator, D. F. Malan, and analyses his motives for staying appeals or confirming them - thus providing insight into the concerns of the South African state.

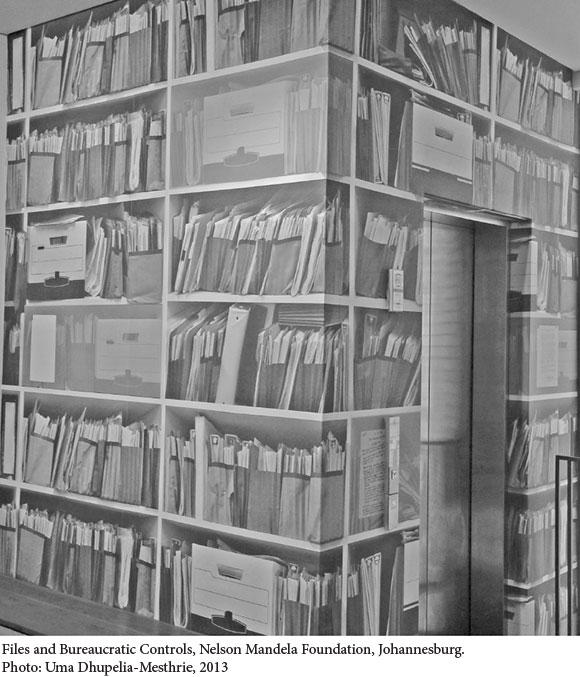

Zuleiga Adams is similarly concerned with filing systems but for a period later than Hyslop's. Her narrative is one of failed filing systems. Hendrik Verwoerd was assassinated in parliament on 6 September 1966 by a parliamentary messenger, Demetrios Tsafendas. Tsafendas had a history of crossing many international borders without the correct papers, of many deportations and a record of mental illness. Between 1935 and 1963, nine applications to enter South Africa were refused, and in 1959 he was placed on a Stop List compiled by the Department of Interior. Yet he legally entered South Africa via the Komatipoort border in 1963 after securing a temporary permit. How he secured this permit and how he subsequently secured a job as a parliamentary messenger in August 1966 points to failing paper systems. The bureaucratic machinery also failed to serve him timeously with a deportation order, which otherwise would have had a different outcome for the life of Verwoerd. How Tsafendas was able to beat a bureaucracy, which Adams notes was supposed to have achieved effective surveillance of its population by the mid-1960s, became the subject of the commission appointed by the state. Adam's article tracks the histories of Tsafendas's files, and in so doing exposes the supposed power of the state to record and remember all those it encountered. Adams and Hyslop's contributions demonstrate the significance of making files the centre of attention - their creation, circulation, storage, recall, and tracking the pace at which paper can move through the bureaucratic chain.

Several articles in this issue have taken cognisance of a newer emphasis on the materiality of paper and rendering these as objects.22 Robertson has shown how the passport should be considered as an object of study; every aspect, from the application form, to the name, the physical description, the photograph, the signature and the seal on the document itself, can be examined at length. He urges one to look at the 'structure of documents'.23 Thus in Hyslop's study, it is the signature of the premier, D. F. Malan, on this deportation order that is of significance. He seeks to answer the question as to why a prime minister of a country would take an interest in the fate of small-time criminals. He pays particular attention to annotations on documents. For Kingwill's African title holders, it is the signature of Sir George Grey, governor of the Cape, and the insignia of Queen Victoria on their title deeds that is important. In my article it is whose signature appears on the form of certificate from India that matters, as too the ability to paste on a photograph after a certificate was issued. The fingerprints on passenger forms and on prison forms for deportees surpass all other forms of identification and point to the state's ability to fix the identity of those under its survey. Harris draws attention to the structure of the various application documents that lead to receipt of an A4 page folded into four sides to make up a Chinese registration certificate. In Breckenridge's article, the code of the identity number is of significance as is the later stamping in red ink of one's race on the card. The empty pages of the Book of Life point to the failure of bureaucratic ambitions. Being but paper, the asylum permits of refugees can, as Amit and Kriger point out, be shredded by police and other officials. In addition, the permit is subject to wear and tear over time as the carrier unfolds and folds it. As the paper withers, it bears little resemblance to a document that bears rights; its status as an official document and the status of the holder likewise deteriorate.

Technological innovations run through many of the articles in the volume. Progress in astronomy led to better measurement of physical spaces and the theodolite in the nineteenth century enabled the surveying of property. The availability of cheaper paper led to widespread distribution of government gazettes in the nineteenth-century Cape Colony, thus enabling brand registration. In the early twentieth century, fingerprinting and photography became important in identifying individuals. x-rays were later used to identify the ages of individuals as they revealed the body's inner bone structure. Punch cards captured the responses of individuals to the 1951 census. An IBM computer has an almost ominous presence in the basement of a 30-storey building in Pretoria to see the Book of Life project through. Photographers grapple with how to capture long lists of paper for better archiving purposes. Paper gets transformed onto microfilms and into digital format. New computer programmes enable better accessing of stored data. The story of paperwork - its life and after life - goes hand in hand with a story of technology.

This issue does much in furthering our understanding of paperwork, the power of the state or its limitations, the inner workings of bureaucratic systems, the officials tasked with developing paper systems, creating paper and inspecting paper, and the meanings of paper for those who acquire them, but there is regrettably no focus on non-state paper systems. Edward Higgs in his review of the Breckenridge and Szreter book in this issue has argued that the link between government and commerce in registration projects in the contemporary world merits some attention. He points to how, in the commercial world, businesses have long developed programmes to identify their customers. He raises the question of 'the profit motive' in registration projects. While Higgs points to the world of commerce, Joel Cabrita has effectively provided an example of how paper systems and registration practices that evolve in the religious world may be a fruitful field of study. Her study of the Nazaretha Church points to the development of membership certificates by Isaiah Shembe for his followers and the relationship of the systems he developed to state bureaucratic practices.24 The paper systems of social, cultural, religious and economic organisations thus may be the direction in which future studies could proceed.

Many of the articles in this issue have a strong South African focus though several point to border crossings and the relationship of South Africa to its neighbours. A greater sense of paper systems in the southern African region is, however, also needed. What might be the experience of passengers landing at Delagoa Bay instead of Cape Town? What can we say about the bureaucratic practices of South Africa's neighbouring states in identifying their citizens? A comparative understanding of systems may yield greater understanding of the South African state itself and the proliferation of various systems in the region.

Jane Caplan and Edward Higgs suggest future research directions in studies of mobility and identification by urging a need to pay attention to the 'spatial nature of power' and the 'architecture of institutional settings' from which, within which and at which paper systems evolve and are practised.25 Though this issue hints at some of these spaces - the border, the immigration office, the depot where the detained are held, the prison setting from which deportees write appeal letters - there clearly remains much more that could be done. Such a focus could yield greater insights not only into manifestations of state power but also the experience of those who encountered the state in their quest to obtain documents - passes, permits, identity cards, temporary permits, residency rights, asylum permits, birth certificates, marriage certificates and death certificates, title deeds.

The issue ends with a review section which, unusually for a southern African history journal, includes reviews of books on South Asian history and paper systems elsewhere in the world. While the significance to South African scholarship of taking cognisance of the collections by Breckenridge and Szreter, and by About, Brown and Lonergan and also that of Robertson have been highlighted in this essay, the reviews of these books in this issue provide a much more comprehensive and critical appraisal of their contribution. Breckenridge, in his review of About et al, draws comparisons between English and French scholarship while Peterson, in his review of Robertson's work, provides us with useful parallels with colonial Africa. Of particular significance to this issue is Ben Kafka's book The Demon of Writing: Powers and Failures of Paperwork.26 As Jonathan Saha's review points out, the book makes an original contribution in its attention to how paperwork can be the undoing of the state's own objectives. Kafka highlights people's encounters with bureaucracy and with paper systems. While Kafka focuses on revolutionary France, his conclusions about the materiality of paper and his essay on the mistakes that appear on paperwork and the results that flow from these are of significance to all studies of paperwork. The story of a clerk who recognises the materiality of paper, soaks documents in water, and reduces them to pellets before disposing of them to save lives best illustrates a significant theme of the book.

Amongst the books on South Asia we have Bhavani Raman's Document Raj which focuses on those at the lower levels of the bureaucracy, a vital group of intermediaries who were the link between people and the colonial state. Nandini Chatterjee, in her review, applauds Raman for not opting for a social history of the Tamil scribes in the local district offices but for undertaking a significant analysis of the work of writing and language. Raman examines the body of writing produced by the scribes and shifts attention from their contents to their form, the script and the language. There is much to be learnt from her analysis of petitions - the different ways in which the state could be addressed and the emergence of a 'colonial form of petition.27 This is an important book on intermediaries, language, law and governance.

Mathew Hull explains the significance and scale of documentary government in colonial India, so that British rule came to be known as 'Kaghazi Raj' or 'Document Rule. He then goes on to examine how remnants of colonial systems survive in independent Pakistan and what new forms emerge. His work, which focuses on Islamabad in particular, draws attention to how the lives of urban citizens are governed by paper and how 'paper is also the means by which residents acquiesce to, contest or use this governance'.28 Hull examines different genres of documents, whether they are handwritten or typed, what ink is used, the size of the paper, its colour and shape, the movement of paper within the bureaucracy, how people are drawn into engagements about paper, and the language used in petitioning. As Ruchi Chaturvedi argues in her review, his 'careful attention to materiality and signs as things is ground-breaking and instructive'.

While Akhil Gupta's book is a contemporary study of the workings of the Indian bureaucracy in the state of Uttar Pradesh it is important in our conception of the state. As Suren Pillay points out, Gupta sees the state as 'an effect rather than as an agent. The book draws one to an understanding of state intentions which may be good and how, despite these intentions, it fails to deliver. Much of the book is about officials, paperwork, filing systems and their consequence for the poor on whom the state's effect can only be described as 'structural violence'. 29

This issue unveils the rich work that scholars have undertaken on paper regimes in South Africa and how this intersects with the global literature. In these pages, the reader will find many conversations about paper systems in different contexts and different times. It has much to say about the state, the bureaucratic machinery, the people who implemented paper systems, the creativity and tenacity of those who engaged with the state and the meanings of documents for those who acquire them. A document might momentarily in its loss produce 'madness' in one's heart, as Baba Bapoo, so eloquently described it, but once he received it there was calm. Thus is revealed the many contradictory emotions a document may produce.30 Paper it may be but its affective quality outweighs its materiality.31

1 See U. Dhupelia-Mesthrie, 'The Passenger Indian as Worker: Indian Immigrants in Cape Town in the Early Twentieth Century', African Studies, 68, 1, April 2009, 126-7. [ Links ]

2 Ibid, 127-8.

3 E. Sisulu, Walter and Albertina Sisulu: In Our Lifetime (Cape Town: David Philip, 2002), 49-50. [ Links ]

4 Quoted in K. Breckenridge, 'Lord Milner's Registry: The Origins of South African Exceptionalism', seminar paper, University of Kwa-Zulu Natal, 2004, 1. This was obtained at http://history.humsci.ukzn.ac.za/files/sempapers/Brecekenridge2004.pdf. The novel is Tell Freedom (London: Faber and Faber, 1981).

5 Indian Opinion, 2 February 1907.

6 J. C. Scott, Seeing Like a State: How Certain Conditions to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1998), 1-4, 76. [ Links ]

7 J. C. Scott, The Art of Not Being Governed: An Anarchist History of Upland Southeast Asia (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009), 2, 174. [ Links ]

8 S. Szreter and K. Breckenridge, 'Editors' Introduction' in K. Breckenridge and S. Szreter (eds), Registration and Recognition: Documenting the Person in World History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), 1-38. [ Links ]

9 K. Breckenridge, 'No Will to Know: The Rise and Fall of African Civil Registration in Twentieth-Century South Africa' in Breckenridge and Szreter (eds), Registration and Recognition, 357-84.

10 Szreter and Breckenridge, 'Editors' Introduction', 3-4, 7.

11 R. Gopinath, 'Identity Registration in India During and After the Raj' in Breckenridge and Szreter feds), Registration and Recognition, 299.

12 Szreter and Breckenridge, 'Editors' Introduction'. 8.

13 J. Caplan and J. Torpey, 'Introduction' in J. Caplan and J. Torpey (eds), Documenting Individual Identity: The Development of State Practices in the Modern World (Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2001), 5. [ Links ]

14 I. About, J. Brown and G. Lonergan, 'Introduction' in I. About, J. Brown and G. Lonergan (eds), Identification and Registration in Transnational Perspective: People, Places and Practices (New York and London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013), 5. [ Links ]

15 Posel's pioneering study of state plans to register customary marriages points significantly to how the state itself could be ambiguous in its motives. Control was one aspect but there was also a 'moral' imperative, a desire to bring Christian ideas to African practices. See D. Posel, 'State, Power and Gender: Conflict Over the Registration of African Customary Marriage in South Africa c.1910-1970', Journal of Historical Sociology, 8, 3, September 1995, 233.

16 Breckenridge, 'Lord Milner's Registry, 23.

17 Breckenridge, 'Lord Milner's Registry' and K. Breckenridge, 'Verwoerd's Bureau of Proof: Total Information in the Making of Apartheid', History Workshop Journal, 59, 2005, 83-106.

18 See, for instance, A Burton (ed.), Archive Stories: Facts, Fictions and the Writing of History (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2005) and the Special Archive Issue of the South African Historical Journal, [ Links ] 65, 1, March 2013 edited by Caroline Hamilton.

19 See, for instance, L. Rizzo, 'Visual Aperture: Bureaucratic Systems of Identification, Photography and Personhood in Colonial Southern Africa', History of Photography, 7, 3, August 2013, 263-82 where she draws on documents from different archives to produce a common narrative. [ Links ] While Jonathan Klaaren does this in his thesis, he is still constrained by having separate chapters for the different race groups. See J. Klaaren, 'Migrating to Citizenship: Mobility, Law, and Nationality in South Africa, 1897-1937' (Unpublished PhD thesis, Yale University, 2004). [ Links ]

20 Caplan and Torpey (eds), Documenting Individual Identity; C. Robertson, The Passport in America: The History of a Document (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010); [ Links ] I. About, Brown and Lonergan (eds), Identification and Registration.

21 See for instance, M. Hull, Government of Paper: The Materiality of Bureaucracy in Urban Pakistan (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2012), 86-101 and B. [ Links ] Raman, Document Raj: Writing and Scribes in Early Colonial South India (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2012), 161-201. [ Links ]

22 B. Kafka, 'The Demon of Writing: Paperwork, Public Safety, and the Reign of Terror', Representations, 98, Spring 2007; B. Kafka, The Demon of Writing: Powers and Failures of Paperwork (New York: Zone, 2012); [ Links ] Robertson, Passport in America; L. Rizzo, 'Visual Impersonation: Population Registration, Reference Books and Identification in the Eastern Cape, 1950s-1960s', History in Africa, 41, 2014, 221-48; I. L. Masondo, '"We Are All Coloured": An Exploration on the Impact of the South African Population Register on Processes of Seeing and Identification in South Africa'(Unpublished MA thesis, University of the Western Cape, 2013).

23 Robertson, Passport in America.

24 J. Cabrita, Text and Authority in the South African Nazaretha Church (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014). [ Links ]

25 J. Caplan and E. Higgs, 'Afterword: The Future of Identification's Past: Reflections on the Development of Historical Identification Studies' in About, Brown and Lonergan (eds), Identification and Registration, 307.

26 (Cambridge and London: Zone, 2012).

27 Raman, Document Raj, 8,14, 161ff.

28 Hull, Government of Paper, 1.

29 A. Gupta, Red Tape: Bureaucracy, Structural Violence and Poverty in India (North Carolina: Duke University, 2012). [ Links ]

30 The permit applications, for instance, which black students had to apply for during the apartheid era to study at 'white' universities, produced anger, humiliation, anxiety but also relief and even pride when they were granted. See U. Dhupelia-Mesthrie, 'Cape Indians, Apartheid and Higher Education, The Journal of Natal and Zulu History, Special Edition, The University College for Indians on Salisbury Island, 31, 1, 2013, 72.

31 I would like to thank Andrew Bank, Diana Wylie and Keith Breckenridge for reading and commenting on a draft of this essay. In the end I take responsibility for all the sins of omission.