Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Kronos

versión On-line ISSN 2309-9585

versión impresa ISSN 0259-0190

Kronos vol.38 no.1 Cape Town ene. 2012

ARTICLES

Portraits, publics and politics: Gisele Wulfsohn's photographs of HIV/AIDS, 1987-2007

Annabelle Wienand

Doctoral Student, Michaelis School of Fine Art, University of Cape Town

ABSTRACT

Contemporary South African documentary photography is often framed in relation to the history of apartheid and the resistance movement. A number of well-known South African photographers came of age in the 1980s and many of them went on to receive critical acclaim locally and abroad. In comparison, Gisele Wulfsohn (19572011) has remained relatively unknown despite her involvement in the Afrapix collective and her important contribution to HIV/AIDS awareness and education. In focusing on Wulfsohn's extended engagement with the issue of HIV/AIDS in South Africa, this article aims to highlight the distinctive nature of Wulfsohn's visualisation of the epidemic. Wulfsohn photographed the epidemic long before there was major public interest in the issue and continued to do so for twenty years. Her approach is unique in a number of ways, most notably in her use of portraiture and her documentation of subjects from varied racial, cultural and socio-economic backgrounds in South Africa. The essay tracks the development of the different projects Wulfsohn embarked on and situates her photographs of HIV/AIDS in relation to her politically informed work of the late 1980s, her personal projects and the relationships she developed with non-governmental organisations.1

Introduction

Many commentators have positioned the HIV/AIDS epidemic as the 'new struggle' in post-apartheid South Africa. This was most notable during the years before state provision of antiretroviral treatment2 in the public health care system. South Africa remains the country with the highest burden of HIV infection in the world and yet despite continuing discrepancies in access to care, recent statistics paint a much more optimistic picture.3 Over the years the South African epidemic has been assessed in historical, medical, political and social terms,4 but little has been written on its visual history, or more specifically on the role that photography has played in representing HIV/AIDS in South Africa.5 Even fewer of these accounts consider Wulfsohn's work.6

Beyond the South African context, Susan Sontag's seminal work on the way in which society ascribes meaning and metaphor to illness has contributed to the way contemporary images of HIV/AIDS are read.7 Treichler's account of the role of the media in generating local and global understandings of HIV/AIDS as a cultural phenomenon has informed my understanding of the context of media reporting and the hold stereotypes have over how disease and difference are represented.8 This article engages with Wulfsohn's work by assessing her photographs within the contexts of their publication. I also make use of interviews conducted by myself and others.9 In the course of my research Wulfsohn also shared unpublished work with me, which is included in my analysis. Other primary sources include publications where her photographs feature, including the work she did for non-governmental organisations (NGOs), magazines, newspapers and exhibitions.

News and Media: The Star, Style and Leadership, 1979-1986

Gisele Wulfsohn's childhood fascination with news reporting became a reality when she pursued photography on completion of her studies in graphic design at the Johannesburg College of Art. From 1979 to 1983 she worked at The Star, starting out as a darkroom assistant and then asking to be a photographer when a vacancy became available. When The Star responded that they did not take women photographers, Wulfsohn quickly replied, 'It's time you did' and promptly got the job.10 Wulfsohn admitted that she was not prepared for reporting on hard news at the time and wanted to pursue portraiture and what she called 'more gentle stuff' which she successfully did in her work for the 'Star Women' section and 'The Women's Page'.11

Her work at The Star was followed by three years at Style magazine. Wulfsohn's descriptions of working for Style reveal an awareness of the contradictions of photographing for a publication that focused on fashion and social events at a time when South Africa was on a political knife-edge. When asked whether her photography had been a form of personal expression or an attempt to make a social statement, Wulfsohn responded:

I think it was a bit of both. I think my photography at that time was a bit of personal expression as well as trying to make a statement. I think my photographing people in certain settings would make a statement in a political way. I guess I was doing fashion at the time, so that's personal expression. I didn't mind going and doing a fashion shoot in an Ndebele village in the middle of nowhere.12

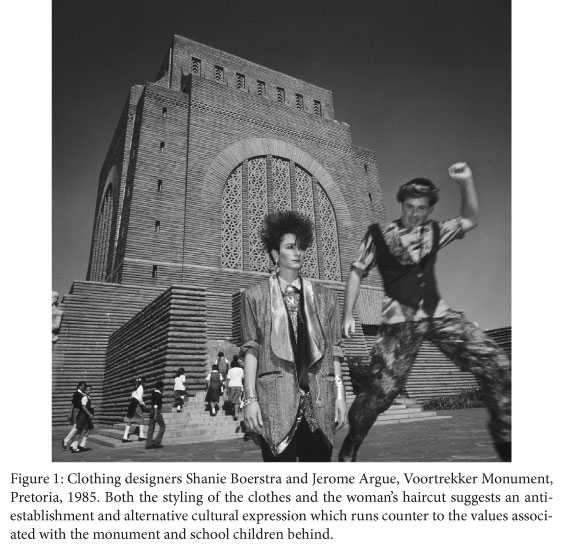

Even within the confines of a fashion magazine aimed at affluent white women, she was aware of the greater political context of what was happening in the country. Her location of fashion within the political is evident in a photograph she took during a fashion shoot she did at the Voortrekker Monument. The clothing designers in the foreground model their alternative outfits, while in the background school children tour the monument which stands for Afrikaner nationalism and right-wing conservatism (Figure 1).

In the same interview Wulfsohn talked about how while working at Style magazine, on the same day after covering a social event she would also drive through to Soweto and photograph there. She reflected that 'it was a bit of a schizoid existence adapting from one situation to the other, but somehow I did it and many others did too.'13 We might well ask how Wulfsohn arrived at the point where she was covering white Johannesburg society events and Soweto in the same day.

Afrapix and 'Going Freelance', 1987-1990

Wulfsohn reflected on two influential moments in the development of her political awareness: one was travelling in Europe in 1979 and being exposed to banned literature, the other was a gift of Ernest Cole's famous book House of Bondage in the late 1970s.14 Cole's images made Wulfsohn more intensely aware of the inequalities of the society in which she lived. This was confirmed by her meetings with other photographers involved in projects such as South Africa: The Cordoned Heart15 which documented black poverty in South Africa.16 Many of the photographers involved in The Cordoned Heart were members of Afrapix, the anti-apartheid photographic collective founded in 1982.

In 1986 Wulfsohn became the chief photographer of Leadership magazine,17 but within a year she decided to work instead as a freelance photographer. She also joined Afrapix. It was around this time that she started to document HIV/AIDS as part of a personal project. Although Afrapix dissolved in 1991, a few short years after Wulfsohn had joined, her involvement in Afrapix and the relationships that she formed there undoubtedly informed her approach to documentary photography. However, Wulfsohn's varied experience prior to going freelance and joining Afrapix follows a trajectory that reveals a growing political awareness and ultimately a desire to pursue work on issues that interested her instead of following briefs.

Like a number of other woman photographers affiliated with Afrapix, including Lesley Lawson, Wendy Schwegmann and Gille de Vlieg (see Kylie Thomas, this Special Issue), she preferred to document social issues that revealed how apartheid laws shaped the lives of black South Africans rather than focusing on township violence and clashes between protesters and police. Examples of the personal projects that Wulfsohn undertook at the time included stories on the taxi industry, adult literacy and domestic workers.18 With the domestic workers project, Wulfsohn worked with Paul Weinberg and together they had a slide show and exhibition of the work (Figure 2). It is interesting to note that Lesley Lawson also focused on women's issues and did extensive projects with women domestic workers, office cleaners and factory workers.19 Lawson later became involved in working with NGOs that were involved in HIV/AIDS education and authored training materials and books.20 One of the book projects authored by Lawson included a number of Wulfsohn's images from a range of different projects, such as Puppets for AIDS which will be discussed in greater detail later in this article.21

Afrapix was based in Khotso House in Johannesburg, which was home to a number of other anti-apartheid groups, such as the Black Sash and the South African Council of Churches. Apart from supplying the foreign press with images, Afrapix-also provided photographs to the local alternative media, trade unions and grassroots organisations. This model of working with organisations which would facilitate introductions to subjects and communities would continue to inform Wulfsohn's work in the 1990s when she remained invested in telling a particular story either for an individual or an organisation, rather than making a statement in her own right.

The End of Apartheid and the Early Days of the Epidemic, 1990-1997

One of the projects Wulfsohn started in 1990 was photographing South African women activists who had worked towards change and the establishment of a democratic South Africa. These portraits took the shape of a project called Malibongwe (Figure 3). Wulfsohn accredited the impetus behind this project to her experience at Afrapix.22 Over the years, the portraits have been exhibited in a number of different contexts, such as part of the fifty-year commemoration of the Women's March in 2006 when the exhibition Malibongwe, Let Us Praise the Women was displayed at the Apartheid Museum in Johannesburg.23 In 1994 Wulfsohn was one of four photographers commissioned by the Independent Electoral Commission to document the first democratic elections in South Africa. Through these two examples we can see how Wulfsohn's connections to Afrapix, and more generally her documentation of subjects that were used by the anti-apartheid movement, established her reputation as a socially and politically engaged photographer. And yet knowledge and appreciation of her work has remained largely confined to a specific audience in South Africa, and publications overseas which included The Lancet, Mother Jones, The Economist, Marie Claire and Der Spiegel.24

A number of documentary photographers who were members of Afrapix went on to produce HIV/AIDS related work post-1990 for NGO clients. These photographers include Lesley Lawson, Paul Weinberg, Eric Miller and Gideon Mendel. Continuing to explore social concerns was a natural trajectory for many anti-apartheid struggle photographers in post-apartheid South Africa. After all, they were no strangers to development issues, such as health, education, migrant labour and matters related to employment. During the 1980s many of the photographers had produced documentary stories on these issues as a critique of the apartheid system and the ways in which political policy was responsible for black South African poverty and under- development. These stories were made famous in the previously mentioned publication South Africa: The Cordoned Heart and the associated exhibition which travelled internationally.25

It is important to note that Wulfsohn's engagement with HIV/AIDS was not the product of her relationship with Afrapix, but the direct result of her relationship with an HIV positive cousin who lived in San Francisco.26 Motivated by her cousin's request to 'put a face to AIDS in South Africa', Wulfsohn started to document responses to the epidemic, as well as the lives of HIV positive individuals as early as 1987. At this time there was very limited public reporting about the disease in South Africa apart from The Argus newspaper article that broke the story of the first HIV infections in South Africa which were diagnosed in two white, homosexual flight attendants.27 There was also little formal response by the South African Government and the Department of Health.28 This was partly because of the prevailing misperception that HIV would remain largely within the homosexual community and among drug users, and that it would not enter the general heterosexual population and was thus not a national public health concern.29 The late 1980s saw widespread popular resistance to the apartheid state and open conflict between civilians and the police and army. Given the political turmoil in the country in the 1980s, it is hardly surprising that HIV/AIDS was not meaningfully addressed by the state.

Despite the lack of focus on HIV/AIDS during this period, Wulfsohn discovered that the Johannesburg Health Department was instrumental in establishing an HIV education play that was performed in clinics with the intention of increasing condom usage.30 The plays were performed by a group called the City Health Acting Troupe (CHAT). Her images of the performances documented the actors while they were performing in waiting rooms and in other public spaces at the Joubert Park Clinic. Wulfsohn began this work in 1987 and, based on the dates written on some of her images, continued to do so until 1990.

Based on the photographs taken of CHAT performances and events, it is evident that apart from the public health message of correct condom usage, the performances acted out situations, such as a 'disco' where props included a painted backdrop with the word 'disco' and glasses and a bottle of wine. The intended message was most likely that alcohol could put people at risk of HIV infection because people were more likely to make poor decisions and have unprotected sex while drunk. What is jarring about this image is that the context of a 'disco' and drinking wine would most likely have been foreign to the audience in the maternity clinic, who would have been more familiar with a township tavern or 'shebeen' as a social space where people drink alcohol, most likely beer. In this way we can see that early messaging around HIV/AIDS in South Africa was often not adequately researched in order to resonate with the intended audience. This is also evident in the poster stuck to the wall of the maternity clinic warning of HIV infection through needle sharing. Transmission of HIV through intravenous drug use is rare in South Africa where the main mode of transmission is unprotected heterosexual sex. And yet, despite these inconsistencies, the women appear to be enjoying the performance.

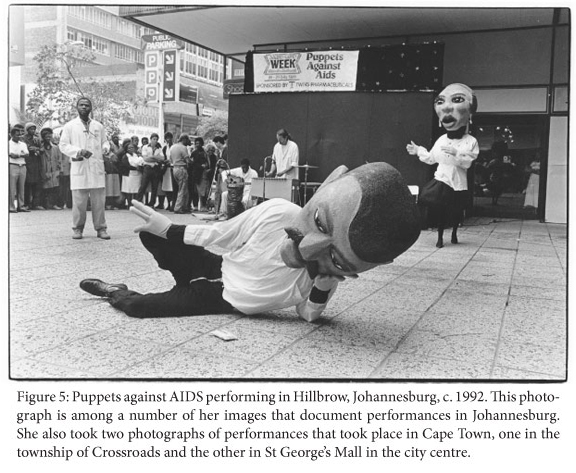

Through photographing CHAT performances, Wulfsohn also came into contact with other HIV education programs organised by NGOs, such as Puppets Against AIDS which performed widely in South African townships and other public spaces in cities with the intention of bringing HIV education messages to audiences in the form of entertainment and interactive performance.31 These performances included large papiermache puppet heads worn by actors as well as other smaller puppets and masks. The scale of the two metre tall puppets attracted crowds because of the theatrical and carnivalesque quality of the puppets. The performances took place throughout the country and included a small marimba band and question-and-answer sessions with the audience after the performances followed by condom distribution.32 Wulfsohn's images of the performances of Puppets against AIDS were widely published abroad in foreign magazines. These images are examples of the innovative public education strategies that were taking place in South Africa at a time when there was limited government or public response to the epidemic. How effective the performances were was never measured nor quantified, and so their initiatives are only properly recorded in observational accounts, including Wulfsohn's images (Figure 5).

Wulfsohn's relationship with Puppets for AIDS continued for a number of years and in 1996 she participated in a pilot program called Puppets in Prison that took place in Diepkloof Prison in Johannesburg. The intention of the pilot program was to run a series of workshops with inmates in the prison, which included making masks and puppets and developing a play that could be performed in the prison with an HIV educational message. Wulfsohn's images document these workshops and performances. They were intended to form part of the final report to the Department of Correctional Services which would help decide whether or not to extend the programme. The pilot was reportedly a great success, but the program was not rolled out to other prisons.33

Johan van Rooy: One Man's Story, 1990-1992

In 1990 Wulfsohn visited a hospice called Sacred Heart where HIV positive people in the terminal stages of AIDS were cared for by a Catholic nun. Her intention was to produce a story on the hospice, but on hearing that another photographer, Graeme Williams, was also photographing the hospice she abandoned the idea. Williams's motive for photographing work at the hospice was as a personal project that offered respite from the violence in the townships that he was documenting at the time.34 He found the care and dignity afforded those in the hospice contrasted to the meaningless of the violence he was witnessing in the faction fighting during the transition period leading up to the first democratic elections.

However, through the Sacred Heart Hospice Wulfsohn met a man called Johan van Rooy at a Christmas function. On hearing about her interest in producing a story on HIV/AIDS, Van Rooy asked Wulfsohn to photograph him. Johan van Rooy was an HIV positive man who had developed AIDS in August 1990 after knowing of his HIV positive status since 1987. At first Van Rooy requested monthly meetings so that Wulfsohn could document his declining health in a series of portraits. As their friendship developed, Wulfsohn asked if she could document other aspects of his life, to which he agreed. What emerged was an increasingly intimate record of Van Rooy's life as an HIV positive man, including medical check-ups, visits from family and ultimately his failing health.

This series was seminal in a number of ways. It appears to be the first documentation of the life of an HIV positive South African. Van Rooy was also one the first South Africans to make his status public in a period prior to the development of organisations, such as the Treatment Action Campaign (TAC), which created a platform for public disclosure as part of an activist agenda and provided support to HIV positive people. Van Rooy was keen to share his story and Wulfsohn approached a number of newspapers. She was turned down by all of them except for Die Vrye Weekblad where journalist Jacques Pauw, founder and assistant editor of the newspaper, came and interviewed Van Rooy. It is interesting to find that Van Rooy's own words were used in the final article published in April 1992, and not a story written by Pauw.35 It is significant that this was the only newspaper willing to take on the story. Die Vrye Weekblad was an anti-apartheid newspaper launched in 1988, which was forced to close down in 1994 because it was bankrupted by the legal costs of defending a report. The intention was for follow-up articles where readers could continue to read about Van Rooy's life, but this did not materialise, possibly because of the legal situation facing the newspaper.

The images that appear in Die Vrye Weekblad include portraits taken a year apart that clearly document the deterioration in Van Rooy's health, as well as an image of him talking to employees of the automobile company Mobil. The story also provides an insight into Van Rooy's everyday life with photographs of him and his dogs (Figure 6), and a nurse examining him during a medical check-up. While these images may not seem remarkable to today's audience, given the exposure to similar types of photographs throughout the 2000s in the international and local media, at the time they must have been a revelation to a South African audience that knew very little about HIV/AIDS. And yet the images are not shocking, especially if compared to stereotypical images that show the extreme physical wasting caused by AIDS that are mostly associated with reporting on AIDS in Africa.

When looking at Wulfsohn's images as they appear within Die Vrye Weekblad, they are clearly crafted to present Van Rooy in such a way that the audience would be sympathetic to him. A portrait of Van Rooy looking directly at the camera appeared on the cover of one section of the newspaper. The portrait presents him as vulnerable, almost pleading. The inclusion of the image of Van Rooy with his dogs is interesting when compared to other images of HIV positive individuals in the early days of the epidemic taken in America and elsewhere (Figure 6). It has been suggested that pets were often included in images, such as photographs of Rock Hudson, because they presented the person as non-threatening and 'normalised' them at a time when their HIV status might have seen as 'other' and 'deviant'.36

The images and text present Van Rooy as a courageous man intent on publicising his story in order to increase understanding about the disease and acknowledge its presence in society. Van Rooy is presented not only as a 'likeable' individual, but through the text which is written in the first person he also comes across as down-to-earth and honest about his experience of living with HIV. And yet there are important absences in the images and text. Van Rooy was a homosexual man who had previously been married to a woman and had two children from his marriage. His long-term partner at the time was an Indian man. These details are revealed in Wulfsohn's other images that remain in her archive but are not included in the newspaper article.

The exclusion of these facts is hardly surprising considering that Wulfsohn first photographed Van Rooy in 1991, the first year after the end of apartheid. Homosexuality was a criminal offence under apartheid law, as were sexual relations with a person of a different race. The details of Van Rooy's personal life would have shocked many conservative South Africans at the time. However, it is important to note that while Wulfsohn had photographed Van Rooy's two daughters by the time of the publication of Die Vrye Weekblad article, it was only later that she documented his lover at his side as he was dying and during the funeral service. The fact that Van Rooy was in contact with his daughters suggests a degree of civility and support from his ex-wife who is not pictured in Wulfsohn's work. Her exclusion of the daughters from the published version of the story was most likely in order to protect them from public scrutiny.

Van Rooy was infected with HIV prior to the development of effective antiretro-viral treatment. In June 1992 he became very ill and was bedridden. Prior to this Van Rooy had asked Wulfsohn to document him dying and also his funeral. Many of Wulfsohn's images of Van Rooy in the final stages of his life and also at his funeral echo images originating elsewhere, such as the famous photograph of David Kirby by Therese Frare that was controversially used by Benetton in an advertisement in 1991, as well as the images taken by Nan Goldin of her friends dying of AIDS in the late 1980s in New York.37 When asked about these images, Wulfsohn responded that she could see the similarity but cannot remember even being aware of them at the time.38

My intention in emphasising the similarities between Wulfsohn's work and images produced elsewhere is to reveal how her essay told a comparable story to that told in other parts of the world, and that in the United States HIV positive people faced similar discrimination and stigma at this stage of the epidemic. The difference is that HIV/AIDS was hardly reported on in South Africa in the early 1990s, a time when the epidemic had not yet reached the point when people were dying in large numbers. At this point there was little reporting, let alone reporting on discrimination. This would only come later with Gugu Dlamini's murder in 1998, Nkosi Johnson's exclusion from school in 2001 and other similar cases in the early 2000s.39

Wulfsohn's essay on Van Rooy may appear a simple documentary exercise in photographing the life and death of someone with HIV, but it was unique in South Africa at that time. It would be a number of years before similar images appeared in the South African media. The 1999 series of the televised show Siyayinqoba Beat it! is the earliest example of similar stories and public disclosure of HIV positive sta-tus.40 The television series included guest appearances by Faghmeda Miller, Edwin Cameron and Nkosi Johnson, who were all photographed by Wulfsohn around the same time.41 Wulfsohn's photographs of Van Rooy, together with the portraits she went on to produce for the Living Openly Project which will be discussed shortly, are historically important because they document South Africans of different races and classes. Photographic engagement with HIV/AIDS in South Africa has tended to focus on socio-economically marginalised black communities feeding the perception that HIV/AIDS is a 'black' disease and that it only affects the poor.

Other South African photographers who have documented HIV/AIDS in South Africa include Graeme Williams, Gideon Mendel, Pieter Hugo, Eric Miller, Paul Weinberg, Oupa Nkosi, Nadine Hutton, Santu Mofokeng and Fanie Jason. These photographers have produced images for very different personal reasons and the images have appeared in diverse contexts, including print and online media, foreign publications, books and galleries. While their work is all distinctive in intention and style, it is important to note that all of their stories focus on black South Africans who are infected with, and affected by, HIV/AIDS. I am certainly not suggesting that this was an explicit decision on behalf of the photographers. It is simply an observation made when looking at the history of documenting HIV/AIDS in South Africa. While black South Africans carry the highest infection burden when compared with other race groups in the country,42 Wulfsohn's images offer a broader and more complicated depiction of HIV/AIDS that is not necessarily captured by statistics. By seeking to photograph HIV positive individuals of different races, sexual orientation, class and social backgrounds, Wulfsohn's images give a more varied account and, as a body of work, fundamentally challenge stereotypes about the disease. In addition her adoption of portraiture as her primary approach to documenting people living with HIV/ AIDS served to humanise a disease that was so often reported in terms of numbers. The combination of her choice of subject and her extensive use of portraiture make Wulfsohn's contribution to representing HIV/AIDS in South Africa distinctive.

The Living Openly Project, 1990s-2000

In the mid-1990s Wulfsohn was approached to take part in the Beyond Awareness Campaign organised by the South African HIV/AIDS and STD Directorate of the Department of Health. One of the partners of the Beyond Awareness Campaign was the non-profit organisation Centre for AIDS Development, Research and Evaluation (CADRE). CADRE was responsible for researching and implementing the campaign's services, materials and projects. The main intention of the campaign was to increase active public responses and engagement with HIV/AIDS by taking projects into communities, as well as by making information more easily available. The initiatives included the promotion of a national toll-free multilingual AIDS helpline, and provision of free education and workshop materials. Wulfsohn was involved in the Media Workers Project that brought together photographers and journalists with the purpose of addressing the lack of reporting on social action around HIV/AIDS. At the time media reporting showed only the sick and dying and rarely showed any response to the epidemic by individuals, communities or organisations.43

Wulfsohn explained that 'the idea was to do so-called "positive stories". People didn't want to see death and dying of AIDS...'44 Wulfsohn identified the kinds of stories they would research and report on. Examples included photographing volunteers at Cotlands45 who would massage sick infants, families who adopted HIV positive babies, and a community initiative called the Mohau Centre46 that looked after abandoned HIV positive children. These stories were then provided free of charge to different media publications and a database of the photographs and articles was created to encourage further publication of the materials.47 Wulfsohn's images from this period are journalistic and document the details and people involved in the projects she was photographing.

The photographers and the journalists had to generate their own ideas for the different stories and it was in this way that Wulfsohn came upon the concept for the Living Openly Project. She explained that the impetus for the Living Openly Project was Constitutional Court judge Edwin Cameron's public disclosure of his HIV positive status. With Cameron's disclosure the idea came to her that there must be other people who had disclosed their status and were 'living openly' in their communities. She teamed up with journalist Susan Fox who was also working on the Beyond Awareness Campaign. Wulfsohn described how they travelled to different parts of South Africa 'in search of people' through NAPWA48 and different organisations. 'We would try and find people who were willing to go public and have their name and photographs published. And that was how the Living Openly Project came about.'49

The Living Openly Project resulted in a soft cover publication with black and white photographs and text. The book presents portraits of individuals together with their testimonies based on interview transcripts. The book was distributed for free in clinics, libraries and other public places. The design and feel of the book was intended to encourage people to pick it up and take it home to their families.50 The opening pages explain how the project came about as a response to

...discussions around media portrayals of people living with HIV/AIDS, and the understanding that so often these images were harsh and stereotyped. Where people were ill, they were portrayed in bed, emaciated and downcast. Where people were healthy, instead of their faces we saw their heads turned away, more often than not to protect their identities.51

The Living Openly images were thus made with the specific intention of countering existing sensational and negative media stereotypes, and combating the stigma associated with the disease. And yet Wulfsohn was not blind to an alternative view of the project as is evidenced by her comment,

I suppose [the] Beyond Awareness[Campaign] was propaganda, just showing positive stuff. But you know, I had this little thing that I used to say and that was, 'While life goes on, death goes on.' And you have got to balance the two, and that was my own little kind of answer. And I like that really, there are two sides to everything and people have AIDS fatigue you know.52

In this way Wulfsohn touches on two important points. Firstly, she identifies the need to balance stories of the dead and dying with survival stories, accounts that focus on the strength of individuals and positive support from family and community in a context of an onslaught of negative reports of discrimination. Closely related is the point that Wulfsohn makes about 'AIDS fatigue'. It is well documented that the public become immune to images of human misery in the media and suffer from what has become known as 'compassion fatigue'.53 By continually showing images of people dying of AIDS, Wulfsohn suggests that the public will become incapable of feeling or responding to the issue.

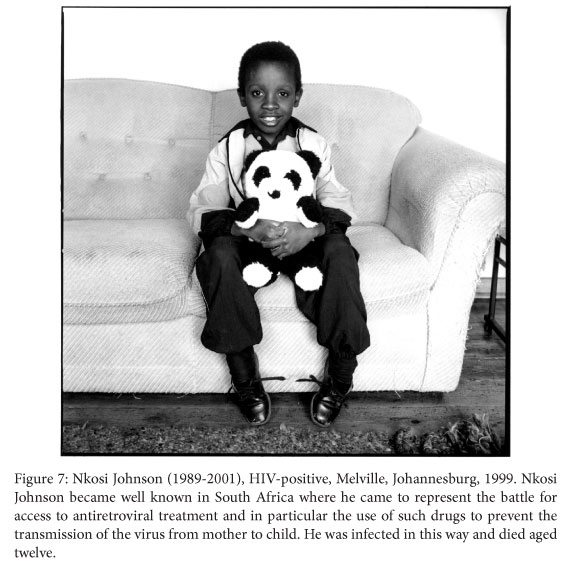

In total thirty-two people appear in the Living Openly book. They include a range of ages and are representative, if somewhat self-consciously, of South African society in terms of race, language groups, gender and sexual orientation. They include famous personalities and activists, such as Nkosi Johnson (Figure 7), Zackie Achmat and Edwin Cameron,54 as well as individuals unknown to the general public. Many of those included in the book later went on to become influential HIV/AIDS spokes-people and activists, contributing to organisations offering training and education and involved in policy making. The range of South Africans represented in Living Openly aims to resist stereotypes that have dominated the AIDS epidemic, such as seeing HIV/AIDS as a 'gay disease', or a 'black disease', or as the result of sexual promiscuity or immorality.55 By showing such a diverse selection of people living with HIV/AIDS, Living Openly is subversive of the very process of shaping and reinforcing stereotypes: there are simply too many and too various a collection of images to associate the disease with a single type.

On reading the testimonies in Living Openly, it is evident that the emphasis is on disclosure as a strategy for increasing awareness of the disease and resisting discrimination by encouraging people to acknowledge that HIV/AIDS affects people throughout the country. It is important to note that within the context of the Living Openly Project, the individuals engaged with public disclosure by making their status known to anyone who saw the book, the television show or exhibition. The testimonies directly addressed the stigma of the disease and revealed the responses the participants had when disclosing their HIV status to family and friends. While many of the testimonies record positive outcomes from disclosing, a number of them are also ambivalent because of the discrimination people had endured. The interviews were conducted in 1999 and early 2000 when antiretroviral treatment was not available in public healthcare. All the participants faced an uncertain future. Their situation is very different to that of today, when it is common knowledge that if you are diagnosed, antiretroviral treatment is available and is successful in slowing the progression of the virus and thus prolonging life.

In a pre-treatment South Africa, disclosure was arguably riskier and placed the participant in a more vulnerable position because they faced an uncertain future in terms of their health. There was potentially more fear of HIV/AIDS prior to treatment because at the time it was seen as a certain, and often lingering and painful, death. And yet studies have shown that despite the media reporting of extremely negative and violent consequences to the disclosure of HIV positive status, in a pretreatment South African context the majority of people reported receiving support from family and friends on disclosing their status.56

In evaluating Living Openly twelve years after it was first published, it is clearly framed within the idealism of the post-1994 'rainbow nation'. Also, by seeking out such a diverse range of people affected by the virus, the book could be critiqued for suggesting that HIV/AIDS affects all South Africans equally. The disparity in socioeconomic situations, as well as access to health care, meant that some South Africans were better, or less well, equipped to cope with HIV infection. This would have been particularly pronounced in the early 2000s, before there was proper access to anti-retroviral treatment in the public health care system in South Africa.

Only one testimony in Living Openly addresses these issues. Edwin Cameron talks of the personal and political motivation for his public disclosure by mentioning the murder of Gugu Dlamini who was killed by members of her community for disclosing her HIV positive status. Cameron contrasts this with his own circumstances and the support he was given by friends and colleagues when he decided to openly disclose. He also makes mention of the social and economic security he enjoyed because of his job and crucially, his access to antiretroviral therapy at a time when it was not available in the public health care system. His testimony alone alerts the reader to the differences in life circumstances between the different participants in the book. The importance of Cameron's disclosure cannot be underestimated, not only because of his high-profile position, but also because he was the first South African in public office to do so. This flew in the face of the state's AIDS denialism and bizarre claims from President Thabo Mbeki that he did not know anyone who was HIV-positive.

However, the gains of the book arguably outweigh its shortcomings, especially given the time period it was produced in. For instance, it is important that many of the testimonies adopt a 'warts and all' approach to how the subjects talk about themselves and how they have come to terms with their diagnosis. The honesty in what they say, as well as the tone and turn of phrase in the text, represents the subjects as believable people who would be familiar to the intended South African readership. For example, one of the participant testimonies reads as follows:

You eliminate the gossip factor because if they suspect you are HIV positive, they will gossip about you. You worry all the time about what everybody thinks, whereas if you talk about it, they cannot gossip because you've already told them. To keep it in, you contribute to your own death because you're so worried about what everyone will think. But there are consequences sometimes, I mean it wasn't nice losing contact with members of my family.57

The image and the text humanise the subjects by presenting them in an honest and straightforward way. In short, they are portrayed as people 'just like us' and thus the images work to resist the stereotypes that have usually divided people into 'us' and 'them' according to perceived differences, such as race, sexuality and behaviour. In contrast to earlier education campaigns about HIV/AIDS that had presented the disease as a faceless threat, Living Openly was ground-breaking in terms of not only showing South Africans with the disease, but also directly addressing discrimination and fears people had about it.

While the text provides information about the subjects and their experiences of living with HIV, the photographs perform a vital role in that they provide the viewer with an actual image of the subject. The reason this is important is because many of the misconceptions and prejudices about HIV/AIDS function visually. For example, one of the ways HIV is connected to the visual is judging whether or not a person looks like the 'kind' of person who could be at risk of HIV.58 This implies a moral judgement of the person based on how they behave or dress, or simply how they look. Alternatively, people are often judged as HIV positive if they look ill or are thin. One of the early challenges of HIV education programs was to explain the differences between HIV infection and AIDS, where the former means a person is infected with the virus while the latter means they are experiencing illnesses caused by the weakening of their immune system. A further challenge was to communicate that anyone is at risk of HIV infection, regardless of class, race, religion and sexuality. These misper-ceptions are tied to visual judgements.

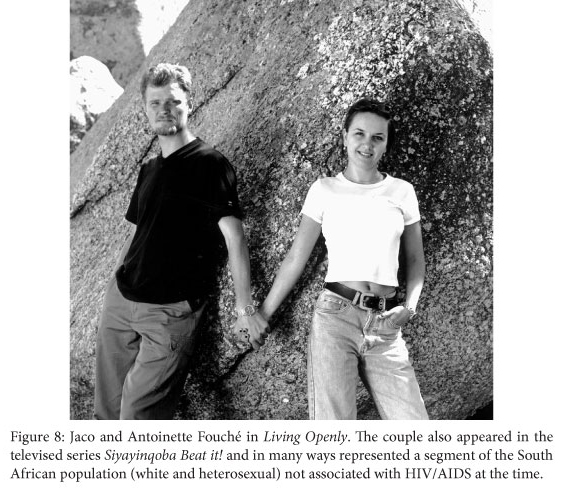

One of the intentions of the book was to show how existing stereotypes dangerously affected people's perceptions of their risk of getting HIV. For example, Jaco Fouche explains 'At the stage I was diagnosed it was thought that white people don't get HIV!59 Fouche's testimony also tackles other misconceptions about how HIV is transmitted when he talks about the concerns that people had over him working in the army kitchen and possibly cutting himself and infecting those who ate the food.60 In this way, the book engages with the misperceptions that the readership would be familiar with and provides information to counter these myths. It also reveals how these myths differed from community to community. And so while Fouche as a white South African was led to believe that HIV was a 'black disease', another black participant Adeline Mangcu explains, 'The way it was presented to us, we thought it was definitely not a black thing. We heard about gay men getting it.. .'61 In this way we can see how different groups have always blamed others for the disease.

The portrait of Jaco Fouche shows him with his wife Antoinette (Figure 8). The image shows the HIV positive couple holding hands and without the text the photograph could be read as a portrait of any young couple. They appear healthy and do not in any way suggest a lifestyle that people would associate with high risk behaviours, such as prostitution, intravenous drug use and so on. However, he does reveal that he has 'been through a lot of things' including living on the street which suggests a lifestyle that exposed him to increased risk of HIV infection.62 Importantly, the text addresses the issue of HIV infection within a relationship where Antoinette says, 'After Jaco told me he was HIV positive, I went for testing as well. We don't know if maybe I contracted it from him. I don't think so because I had other relationships before him.'63

Another important aspect of the photographs in Living Openly is that they are portraits and so the person's face and identity are revealed. This performs a very important function in depicting HIV positive people in a powerful way that counters the shame and stigma that was normally associated with images of HIV/AIDS at this time. Early representations of HIV positive people typically hid their identity and so they were photographed backlit, turned away, or from the back.64 These kinds of images communicate a very strong sense of fear and shame and the potential for violent discrimination. The difference in how the Living Openly portraits represent people is particularly well illustrated by comparing these portraits with another image taken by Wulfsohn as part of a different project on HIV positive domestic workers she did in 2004 called At Home with HIV (Figure 9).

This image was part of a series which was published in Marie Claire magazine.65 In this image the woman's head is cut out of the photograph in order to hide her identity. Wulfsohn's lasting memory of this project was of how fearful the HIV positive domestic workers were of having their identities revealed. Wulfsohn had to frame the photographs in such a way that their subjects' heads were cut out of the image. Some of the women also insisted on being photographed away from their place of employment because they feared that if someone saw the image and recognised the house, they would be able to identify them.66 And yet, the easy identification of the employer in this instance suggests that this domestic worker's primary concern was disclosure within her community. In this way we can see the extreme fear that people had over their identities being revealed, even four years after the publication of Living Openly and at a time when antiretroviral treatment was available in public clinics, although the roll-out only began in April 2004.

Apart from general misperceptions and prejudices about HIV/AIDS, Living Openly also addressed issues specific to particular groups. For example, Faghmeda Miller's story reveals the unique issues she faced when she was diagnosed because of the shame associated with HIV/AIDS in her Muslim community.67 She explains how she was unable to find a single other HIV positive Muslim to share her experiences with and how, despite the support she got from the Christian support group she attended, she longed for support from her own people. Miller went on to become a well-known activist and appeared on radio and also in the televised show Siyayinqoba Beat it!. Miller also founded the organisation Positive Muslims in 2000 which offers support groups and other services.

In evaluating Wulfsohn's contribution to challenging dominant stereotypes of HIV positive people through her photography, much of my analysis of Living Openly has focused on the text and the inclusion of different individuals and their stories within the project. These elements were an important part of her project, especially because the original concept was Wulfsohn's and that, together with Susan Fox, she found the individuals and photographed them. The conceptualisation of the project and the choice of subjects to photograph, are as important as the photographs themselves. All these elements, including the text, are mutually dependent for the meaning of the project. Wulfsohn's engagement with the greater issues surrounding the representation of people living with HIV is critical to reading her images.

Apart from appearing in the book, the Living Openly images were also exhibited at the BAT Centre68 during the International World AIDS Conference in Durban in 2000. The images were then made available by CADRE as a travelling 'pop-up' exhibition which was easy to install and transport. The exhibition was intended to travel to community halls and other places, which unlike galleries, are not equipped to hang exhibitions and images. Another way that Wulfsohn's images came to be viewed by a range of audiences was the printing of posters, which are relatively cheap to produce and easy to transport and distribute in a range of contexts. The participants from Living Openly were also part of a documentary film that was screened on national television.

Making the materials available to a broad range of South Africans was an important aspect of the project for Wulfsohn. Her response to being asked where she liked seeing her work displayed the most was:

You know, I like the idea of a booklet that goes into clinics because then someone will take it home and then other people will read it. Just going beyond the walls of a gallery for me is very important because I mean not many people go to galleries. There are a select number that do but you have got to make it accessible to the broader communities.69

And yet it must be noted that the gallery has been used in other instances to raise awareness about HIV/AIDS, most notably by Gideon Mendel who in 2002 transformed the South African National Gallery into an activist space by inviting local activists and community organisations to participate within the exhibition. The press was invited for the opening night and members of the Treatment Action Campaign were present, together with prominent HIV positive leaders such as Zackie Achmat and Edwin Cameron who addressed the crowd.70

Conversations: HIV and the Family Project, 2004-2007

When the print run of Living Openly ran out, Wulfsohn was approached by CADRE to contact the participants to update the printed version. Wulfsohn traced as many of the original participants as she could. Some had started ARVs, some had died and others had become involved in HIV/AIDS related work through their experiences of living with the disease. The period from 2000 to 2004 was critical in terms of access to antiretroviral treatment for South Africans. After years of rejecting calls for treatment to be made available, the South African government finally announced that ARVs would be made available in public health care from November 2003.

While a second imprint of Living Openly was not realised, a new project called Conversations: HIV and the Family took shape and was carried out in 2004 and 2005.71 Like the Living Openly Project, Conversations also developed training resources, including a book and photographic display of the project that is available from CADRE. The book was published in 2006 and reprinted with a revised introduction in 2007. In total twelve families took part in the project. The book is comprised of twelve sections, one on each family. The project set out to work with a broad understanding of what a family is, especially in the context of HIV/AIDS. This meant that the families include friends, care-givers, grandparents and others. In many instances, families take care of other extended family members and have also taken in children who have been abandoned or who have been orphaned. In this way the images challenge the conventional Western idea of the nuclear family and mirror the kinds of families most South Africans actually come from.72

Each section opens with a group portrait of the family. This is followed by members of the family, including the children, talking about their experiences. The text is written in the first person and is based on interviews conducted by Betsi Pendry. Other photographs of the family going about their daily lives are also included. Like Living Openly, the images in Conversations work very closely with the text and the two elements inform each other. The portraits are titled with the names of the people to help the reader match the individuals to their text. The titles also enable the viewer to work out the relationships between the different family members.

The overall concept behind the project was to share the personal experiences of South African families and how they have been affected by HIV. The book was intended to reach a wide South African audience and inspire other families to accept and talk about HIV and how it affects their lives. Like Living Openly, the selection of South Africans from different race groups, cultures, religions, sexual orientations and regions, aimed to be representative of the country.73 In a similar way to Living Openly, this publication also aimed to demonstrate that regardless of socio-economic background, HIV has an impact on all families. The limitations of this framing have been discussed earlier in terms of the very real socio-economic differences between different families which have a direct impact on the ability to cope with the impact of HIV/AIDS on a family. And yet what this book highlights is that despite financial and physical challenges, these families have responded with resilience in the face of loss and suffering. By showing such a range of different families, the authors hoped that South Africans from different backgrounds would be able to relate to at least one of the families.

Unlike the first publication, the people involved in Conversations were not all HIV positive. Although it is not made explicit, it is understood that many of the people pictured are not HIV positive, such as the Motsoeneng children who survived their parents who had died of AIDS related illnesses. In Conversations, the family is affected by the diagnosis and, at times, the death of family members, but they are not necessary infected themselves. It was during this period that public health messaging emphasised that all South Africans are affected by HIV/AIDS, even if they are not infected.

The Conversations book opens with photographs of the five-session workshop that all the families attended as part of the project. The workshop was based on social therapy methodology and used drama and other visual arts as a way of getting the participants to engage with each other and to share their experiences. The intention of the workshop was to bring different families together so that they could be part of a larger community of people who they shared experiences with, and in this way found support and comfort in knowing that they were not alone in what they were experiencing.

This project took place at a time when support groups were not well established in many parts of the country. It is interesting to note that support groups seemed to become a common feature with the provision of antiretroviral treatment in the public healthcare sector in April 2004. This project took place during the early years of antiretroviral treatment and many of the interviews reveal the lack of counselling and social support experienced by the participants.74 The new introduction to Living Openly in 2007 also clearly documents the increased access to antiretroviral treatment with a number of the participants being on treatment and also a number of the children being protected from vertical transmission.75

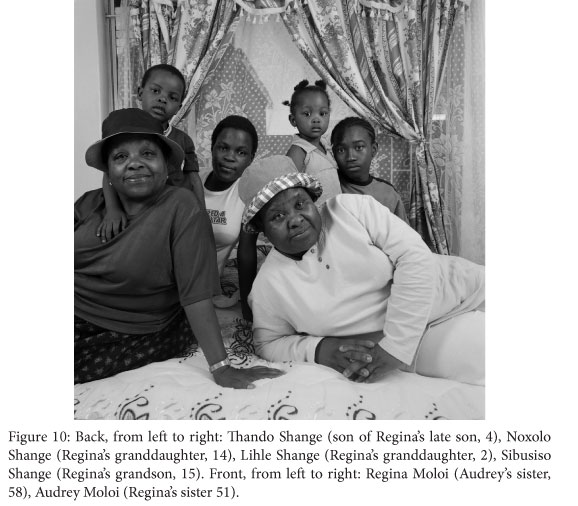

Conversations came about at a time when the social impact of the epidemic started to become apparent in South Africa. It was noted that unlike many other diseases, the effects of HIV/AIDS were not limited to those infected with the virus. This was particularly so because HIV/AIDS disproportionately affects adults who are not only breadwinners for families, but are also parents. As people started to die from AIDS related illnesses, it was the young and the old who remained behind. This resulted in grandmothers becoming responsible for the care of multiple grandchildren, as seen in the case of the Shange family (Figure 10).76

Another consequence of the epidemic was the emergence of child-headed households where children had no family to go to and so stayed together as a family once their parents had died. This social phenomenon has been documented by a number of South African photographers including Wulfsohn, Mendel and Mofokeng. It is interesting to note that there are very few child-headed household documented in South African surveys and there is the critique that these are the kind of stories sought out by journalists and photographers when this is not the norm. The vast majority of children who are orphaned are cared for by extended families.77

The story of the Mtsi family in Conversations documents how one woman started a creche which became a care centre for HIV positive and abused children.78 Seipati Mtsi and her mother and daughters care for the children at what has become known as Little Angels Life Care Centre in Orange Farm. This story shows how individuals in communities have responded to the epidemic and taken steps to provide support and care for those affected by HIV/AIDS. In this instance, one family has gone beyond caring 'for their own' and have started looking after those whom no-one else is caring for and who are without any financial or state assistance. However, since Little Angels was first reported on in the media, they have received donations and assistance from companies and individuals.

The Wippenaar family is a large extended family that shares a home in Steenberg, Cape Town.79 Jounoos Wippenaar is HIV positive and lives with his sister's family. Their stories reveal a range of opinions and responses to HIV in the family. These perceptions echo commonly held views and in the context of the book, they are challenged and brought out into the open. For example, Jounoos's niece, Soraya says 'It was a big shock when Jounoos told us he had HIV. This AIDS thing has been happening all over for a long time, but I never thought it would come to our family.'80

Christo Greyling appeared in Living Openly and in Conversations he is joined by his wife Liesl. Since he was first involved in Living Openly, he and his HIV negative wife have had a daughter and are expecting a second child. The emphasis of their story as a family is their decision to have children despite the risk involved in potentially infecting Liesl with HIV. Christo, a Christian pastor, talks frankly about how they took steps to ensure that the risks were minimised.81 In this way, their story provides information for other sero-discordant82 families who find themselves in a similar situation of wanting to have children. Christo also addresses the issue of stigma around HIV when he discusses his experiences of disclosing his status to his congregation.

There was so much stigma connected to HIV that I was asked to prove that I was infected from a blood transfusion and not from something else. I also had to prepare a press statement for the church. I realised that my congregation was able to accept me, but not 'those others'.83

Christo Greyling left the church in order to develop an AIDS education program.

The Conversations book purposely features a diverse selection of different South African families affected by HIV/AIDS. It includes families with child-headed households and those in foster care.84 There are also large extended families, such as the Mabena, Wippenaar, Mofokeng and Ngwenyama families.85 There are families from different cultures, races and parts of the country. There are single parent families, such as the Mazibuko family.86 There is the Markland/Sabbagha family where a male homosexual couple live with the one man's daughter.87 There are families where there are still challenges in accepting HIV/AIDS, such as the Abrahams family. Then there is the Greyling family with an HIV positive Afrikaans minister and his HIV negative wife.88

This wide selection results in an inclusion of nearly every challenge facing families in South Africa, including issues such as disclosure, substance abuse and HIV, sero-discordant couples, children and HIV, preventing vertical transmission from mother to child, poverty, child-headed households, abandoned children and abuse. In this way, Conversations is crafted not only as an educational tool, but also as a way of revealing the full extent of the effects of HIV/AIDS on society and the social conditions and challenges that people face regardless of HIV status. The project addresses the larger impact of HIV/AIDS on South African society and the many challenges facing the country including the wide range of socio-economic and historical challenges which existed before the epidemic, but which now feed into and exacerbate it.89

One of the critiques of NGO work around HIV/AIDS is that because of state AIDS denialism and the fight for the provision of antiretroviral treatment in public health care, treatment has been given an exaggerated importance in terms of ways of addressing the epidemic. There is a criticism of what some have termed 'ARV evangelism' where treatment is projected as the ultimate solution to the epidemic and other challenges facing individuals and communities, such as unemployment and poverty, are overlooked.

While treatment is addressed within some of the families, it does not dominate the narratives. Importantly, the Conversations book also includes stories of individuals who are not 'role models' in terms of the public health messages of 'open disclosure', condom usage and so on. For example, the stories of the Abrahams, Shange and Raphasha families address how individuals have been unable to accept their HIV positive status, or have resisted being tested, or have not told their sexual partner of their status or battle with condom usage. In this way, a very real sense of the challenges of how HIV shapes peoples' lives is addressed.

An additional concern is that NGOs and international aid organisations are seen as shining white knights 'saving' the African continent.90 This concern raises questions related to reporting on the African AIDS epidemic in the international media which emphasises a lack of action by African states and focuses on the scale of human suffering caused by the epidemic.91 It has been argued that the international media focus on portraying African experience in bleak terms.92 Some of the stories told within Conversations offer examples of individuals and communities responding to the challenges of HIV/AIDS of their own accord, such as the Mtsi family.93 These stories arguably resist the portrayal of Africans as passive victims of the epidemic and offer a counter point of view.

Wulfsohn's relationship with CADRE produced two comprehensive bodies of work, Living Openly and Conversations: HIV and the Family. While Living Openly was originally Wulfsohn's idea, her relationship with CADRE enabled her to devote time and energy to the project and in this way her tie to the NGO was beneficial. When asked if there were times if she felt her work was compromised by her relationships with NGOs, Wulfsohn responded that the nature of the relationships she had developed with NGOs always gave her freedom and that she had never been told to work in a particular way. This is in contrast to other photographers documenting HIV/ AIDS or other social issues for NGOs who have reported that in certain assignments they were very tightly controlled in terms of a specific shot list, and also encouraged to present their subjects in a particular way.94

In this way it is evident that the nature of the relationship between photographer and NGO varies between different photographers and from organisation to organisation. It must also be noted that some photographers have arguably negotiated a specific kind of agreement where they do have more control over the kinds of images that they produce. Others have simultaneously shot their own stories alongside their paid work and in this way used the travel for an NGO project to help them develop a personal project.95 It is also undeniable that given the sensitive nature of photographing HIV/AIDS, photographers needed to work with NGOs or community organisations in order to be introduced to potential subjects. This can be seen as a problematic relationship because of the possibility of the subject feeling obliged to agree to being photographed because they are receiving care or assistance from the NGO.

Photographers working with NGOs have also arguably given rise to a dominant discourse of 'good' role models, those resilient survivors who take their medication correctly, eat healthily and conduct their lives according to textbook 'good' HIV positive behaviour. The danger of these kinds of stories is that it sets people up for failure, as well as condemning those who do not meet the mark. And yet the stories that appear in the Conversations book do not fall within this category and present an honest picture of the different responses individuals may have.

Gisèle Wulfsohn was diagnosed with lung cancer in 2006 while working on the Conversations project. Despite a bleak prognosis that she would survive for only a few months, Wulfsohn lived for another five years. She passed away in December 2011. In her discussion of her illness, Wulfsohn often referred to the strength and perseverance she derived from her work with people living with HIV/AIDS. In particular, she commented on the need to be open about illness, and attributed her continued health to the acceptance of her condition and to her decision to talk openly and frankly about it.96

Conclusion

Wulfsohn documented HIV/AIDS in South Africa for close on twenty years. In this time she arguably provides the most extensive visual record of the history of HIV in South Africa. The only other photographer to have documented the epidemic for such an extended time during this time period, and with equal dedication, is Gideon Mendel. But there are some important distinctions. Wulfsohn's work on HIV/AIDS predated Mendel's by five years and was focused only on South Africa and did not include other African countries. Whereas Mendel worked primarily as a photojour-nalist for the British media and also for international aid organisations addressing mostly a European viewership, Wulfsohn's images were produced with a local South African audience in mind. An exception for Mendel was his work with the TAC which was used locally by the organisation. Wulfsohn's engagement with documenting the epidemic was also much broader than that of other photographers in terms of the diversity of racial, socio-economic and cultural demographics of the South Africans she photographed. Her work is singular in this regard and thus powerfully subverts stereotypes of AIDS as an exclusively 'black' or 'poor' disease.

Wulfsohn's documentation of Johan van Rooy was the first story of public HIV disclosure in the South African media. It was also ground-breaking in terms of its approach and the intimacy of the images which ran counter to dominant dehumanising modes of representing AIDS patients at the time. This series stands out because of the sensitivity and gentleness of the images and was a first for the South African context. It is comparable to Mendel's profoundly moving series The Ward which was produced in 1993 in Middlesex Hospital in Britain.97

Wulfsohn's portraits that appear in Living Openly and Conversations were seminal in their representation of HIV positive individuals as ordinary South Africans. Retrospectively these portraits also serve as an important record of brave men, women and children who challenged perceptions of HIV/AIDS in a bid for a better society. Many of these people are not acknowledged in other histories of the epidemic and in this way Wulfsohn's photographs offer a distinctive account. Wulfsohn's portraits can be compared to her portrayal of veteran women activists and in a sense go beyond a humanistic approach and suggest an honorific tradition.

Wulfsohn's quiet and modest approach to documenting HIV/AIDS, as well as the low profile forms of publication she favoured, such as posters and booklets distributed in clinics, meant that her work was rarely known outside of these community circles. Despite the obvious aesthetics merits of her work, Wulfsohn appeared to favour the ability of the images to fulfil a social and educational function over their visual appeal. The variety and complexity of the stories she told has resulted in a unique archive of the epidemic in South Africa. No other photographer has addressed such diverse responses to the epidemic, or such a wide selection of different individuals from across the country. Wulfsohn's dedicated and sustained engagement with one of the biggest challenges facing the country and its citizens in the post-apartheid era should be not only be remembered but also celebrated.

1 Gisele Wulfsohn died in December 2011 after living with cancer for a number of years. I would like to thank her for generously sharing her photographs and agreeing to interviews at a time when she was not well. I would also like to thank her husband Mark Turpin for his encouragement of this research. Thanks are also due to Michael Godby and Nicoli Nattrass for their comments and on-going supervision of my dissertation. I would also like to thank Paul Weinberg for sharing interviews and images that helped shape this research, as well as the anonymous reviewers who helped clarify the purpose of this article.

2 Antiretroviral treatment is used to slow the progression of HIV infection to AIDS related illness and although not a cure, it does significantly prolong life in infected individuals, reduce the risk of maternal-infant transmission, as well as sexual transmission in sero-discordant couples. (Lucia Palmisano and Stefano Vella, 'A brief history of antiretroviral therapy of HIV infection: success and challenges', HIV Therapy Today, 47, 1 (2011), 44-48; Edward Connor et al, 'Reduction of Maternal-Infant Transmission of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 with Zidovudine Treatment', New England Journal of Medicine, 331, 18 (1994), 11731180).

3 Leigh Johnson, Access to Antiretroviral Treatment in South Africa, 2004-2011', Southern African Journal of HIV Medicine, 13 (March 2012), 25.

4 There are too many references to list comprehensively, but the following are amongst the most influential in relation of this article. John Iliffe, A History of the African AIDS Epidemic (Oxford: James Currey, 2006); Shula Marks, An Epidemic Waiting to Happen? The Spread of HIV/AIDS in South Africa in Social and Historical Perspective, African Studies, 61 (2002), 13-26; Nicoli Nattrass, Mortal Combat: AIDS Denialism and the Struggle for Antiretrovirals in South Africa (Scottsville: University of Kwazulu-Natal, 2007); Olive Shisana et al., South African National HIV Prevalence, Incidence, Behaviour and Communication Survey, 2008: A Turning Tide Among Teenagers? (Cape Town: Human Sciences Research Council, 2008).

5 Michael Godby, Aesthetics and Activism: Gideon Mendel and the Politics of Photographing the HIV/AIDS Pandemic in South Africa' in Emevwo Biakolo, Joyce Mathangwane and Dan Odallo, eds., Discourse of HIV/AIDS in Africa (Gaberone: University of Botswana, 2003); Rebecca Hodes, 'Televising Treatment: The Political Struggle for Antiretrovirals on South African Television, Social History of Medicine, 23, 3 (2012), 639-659; Rebecca. Hodes, 'HIV/AIDS in South African Documentary Film, c. 19902000', Journal of Southern African Studies, 33, 1 (2007),153-171; Kylie Thomas, 'Between Life and Death: HIV and AIDS and Representation in South Africa' (Unpublished Ph.D. thesis, University of Cape Town, 2007); Kylie Thomas, 'Photographic Images, HIV/AIDS, and Shifting Subjectivities in South Africa' in Cynthia Pope, Renee White and Robert Malow, eds., HIV/ AIDS: Global Frontiers in Prevention/Intervention (New York: Routledge, 2009), 355-367.

6 Danielle de Kock, 'A Visible Epidemic: South African Photography and the Politics of Representing HIV/AIDS' (Unpublished M.A. thesis, University of Manchester, 2010).

7 Susan Sontag, Illness as Metaphor and AIDS and its Metaphors (London: Penguin, 2002 [1992]).

8 Paula Treichler, How to Have Theory in an Epidemic: Cultural Chronicles of AIDS (London: Duke University Press, 1999).

9 Paul Weinberg, Interview with Gisele Wulfsohn, Cape Town, 7 February 2007.

10 Ibid.

11 Ibid.

12 Paul Weinberg, Interview with Gisele Wulfsohn, Cape Town, 7 February 2007.

13 Ibid.

14 House of Bondage was a banned book within South Africa at the time for obvious reasons. It recorded the everyday brutality of living as a black person under apartheid law where every aspect of life was controlled. Cole's images documented the social landscape of apartheid South Africa and revealed how the political system impoverished black communities with inferior provisions for their education, health and housing.

15 Omar Badsha, ed., South Africa: The Cordoned Heart (Cape Town: The Gallery Press, 1986). The book featured documentary stories from twenty photographers. Produced as part of the Second Carnegie Commission into Poverty, it revealed the ways in which apartheid laws impoverished black South Africans.

16 Paul Weinberg, Interview with Gisele Wulfsohn, Cape Town, 7 February 2007.

17 Robyn Sassen, 'Obituary: Gisele Wulfsohn: Indomitable Spirit', Times Live, 2011.

18 Roger Lucey, dir., The Road to Then and Now (Johannesburg: e-TV Productions, 2008).

19 Barry Feinberg. dir., Images in Struggle: South African Photographers Speak (Johannesburg: International Defence and Aids Fund for Southern Africa, 1990).

20 Lesley Lawson, Side Effects: The Story of AIDS in South Africa (Cape Town: Double Storey, 2008).

21 Lesley Lawson, HIV/AIDS and Development (Johannesburg: Teaching Screens Productions, 1997).

22 Paul Weinberg, Interview with Gisele Wulfsohn, Cape Town, 7 February 2007.

23 Barbara Ludman, 'Gisèle Wulfsohn: A Self-portrait of Courage', Mail and Guardian, 6 Jan. 2012.

24 Ibid.

25 Omar Badsha, ed., South Africa: The Cordoned Heart (Cape Town: Gallery Press, 1986). [ Links ]

26 Gisèle Wulfsohn, Skype interview by author, Cape Town-Johannesburg, 4 May 2011.

27 John Iliffe, A History of the African AIDS Epidemic, 43.

28 Mary Crewe, AIDS in South Africa: The Myth and the Reality (London: Penguin Books, 1992), 61.

29 Lesley Lawson, Side Effects: The Story of AIDS in South Africa (Cape Town: Double Story, 2008), 21.

30 Interview with Gisele Wulfsohn, Cape Town-Johannesburg, 4 May 2011.

31 Interview with Gisele Wulfsohn, Cape Town-Johannesburg, 4 May 2011.

32 Gary Friedman, 'Puppet Power: AIDS in South Africa', Links (Winter 1991), 20-22.

33 Interview with Gisele Wulfsohn, Cape Town-Johannesburg, 4 May 2011.

34 Interview with Graeme Williams, Cape Town-Johannesburg, 24 November 2011.

35 Johan van Rooy, 'My Lewe met AIDS', Die Vrye Weekblad, 27 March-2 April 1992, 17-20.

36 Paula Treichler, How to have Theory in an Epidemic, 80.

37 Nan Goldin, I'll Be Your Mirror (New York and Zurich: Whitney Museum of American Art and Scalo, 1996).

38 Interview with Gisele Wulfsohn, Johannesburg, 15 July 2011.

39 Colin Almeleh, The Longlife AIDS-Advocacy Intervention: An Exploration into Public Disclosure (Cape Town: Centre for Social Science Research, 2004).

40 Rebecca Hodes, 'Televising Treatment: The Political Struggle for Antiretrovirals on South African Television', Social History of Medicine, 23, 3 (2012), 639-659.

41 Jack Lewis, dir. Siyayinqoba Beat it!. Seriesl (Johannesburg: e-TV Productions, 1999).

42 Olive Shisana et al., South African National HIV Prevalence, Incidence, Behaviour and Communication Survey, 2008: A Turning Tide Among Teenagers? (Cape Town: Human Sciences Research Council, 2008).

43 Warren Parker, South Africa's Beyond Awareness Campaign: Tools for Action. Available at: http://www.cadre.org.za/files/BAC_ Overview_AIDS_2000.pdf. Accessed 31 May 2012.

44 Interview with Gisele Wulfsohn, Cape Town-Johannesburg, 4 May 2011.

45 Cotlands is a non-profit organisation that fulfils a range of services for children who have been neglected, abused, abandoned, or who suffer from a life-threatening disease. Apart from its many other activities, Cotlands provides end-stage palliative care for children with AIDS.

46 The Mohau Centre is based in Pretoria and provides care and support to orphaned, abused, abandoned, neglected and terminally ill children and their families who are infected or affected by HIV/AIDS.

47 Interview with Gisele Wulfsohn, Cape Town-Johannesburg, 4 May 2011.

48 The National Association of People Living with HIV and AIDS (NAPWA) is a non-profit organisation that aims to support, educate and empower HIV positive people in South Africa through support groups, training and advocacy.

49 Interview with Gisele Wulfsohn, Cape Town-Johannesburg, 4 May 2011.

50 Gisele Wulfsohn & Susan Fox, Living Openly: HIV Positive South Africans Tell Their Stories (Pretoria: Department of Health, 2000).

51 Ibid., 3.

52 Interview with Gisele Wulfsohn, Cape Town-Johannesburg, 4 May 2011.

53 Susan Moeller, Compassion Fatigue: How the Media Sell Disease, Famine, War and Death (New York: Routledge, 1999).

54 Nkosi Johnson was an HIV positive boy infected through vertical transmission. He captured the public's attention as a spokesperson during the period when the South African government resisted providing antiretroviral therapy in public clinics. Zackie Achmat was one of the founding members of the Treatment Action Campaign (TAC) and served as its chairperson for many years. He rose to prominence by refusing to take antiretroviral treatment until it was available in the public health care service. Edwin Cameron is a Constitutional Court Judge who was the first person in public office to openly disclose his HIV positive status.

55 Sontag, Illness as Metaphor, 111-113; Treichler, How to have Theory in an Epidemic, 113-114.

56 Colin Almeleh, The Longlife AIDS-Advocacy Intervention.

57 Wulfsohn and Fox, Living Openly, 63.

58 Leana Uys et al.,'"Eating Plastic", "Winning the Lotto", "Joining the WWW" ..: Descriptions of HIV/AIDS in Africa', Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care, 16, 3 (2005), 11-21.

59 Wulfsohn and Fox, Living Openly, 63.

60 While it is possible for someone to be infected by coming into contact with blood, it is highly unlikely that transmission could occur through food, unless the person had cuts or sores in their mouth and there was a large quantity of blood in the food. These kinds of 'scare stories' about unusual ways HIV can be transmitted detract from the fact that in South Africa the most common mode of transmission is unprotected heterosexual sex.

61 Wulfsohn and Fox, Living Openly, 21.

62 Ibid., 63.

63 Ibid., 63.

64 Rebecca Hodes, 'HIV/AIDS in South African Documentary Film, c. 1990-2000', Journal of Southern African Studies, 33, 1 (2007), 153-171; Treichler, How to have Theory in an Epidemic, 77.

65 Interview with Gisele Wulfsohn, Cape Town-Johannesburg, 4 May 2011.

66 Interview with Gisele Wulfsohn, Cape Town-Johannesburg, 4 May 2011.

67 Wulfsohn and Fox, Living Openly, 11.

68 The BAT Centre is an arts and culture community centre in Durban with performance venues, gallery space and a visual art studio.

69 Interview with Gisele Wulfsohn, Cape Town-Johannesburg, 4 May 2011.

70 Michael Godby, 'Aesthetics and Activism: Gideon Mendel and the Politics of Photographing the HIV/AIDS Pandemic in South Africa'.

71 Gisele Wulfsohn, Betsi Pendry and Maren Bodenstein, Conversations: HIV/AIDS and the Family (2nd edition, Johannesburg: CADRE, 2007).

72 Margo Russell, 'Understanding Black Households: The Problem', Social Dynamics, 29, 2 (2003), 5-47.

73 Interview with Gisele Wulfsohn, Cape Town-Johannesburg, 4 May 2011.

74 Wulfsohn, Pendry and Bodenstein, Conversations: HIV/AIDS and the Family, 23-25.

75 Vertical transmission is when an unborn child is infected by the mother in utero, during child birth or from breast feeding.

76 Wulfsohn, Pendry and Bodenstein, Conversations: HIV/AIDS and the Family, 19-21.

77 Helen Meintjes and Rachel Bray, '"But Where are our Moral Heroes?": An Analysis of South African Press Reporting on Children affected by HIV/AIDS' (Cape Town: Centre for Social Science Research and The Children's Institute, Working Paper, 2005).

78 Wulfsohn, Pendry and Bodenstein, Conversations, 26-29.

79 Ibid., 11.

80 Ibid., 11.

81 Antiretroviral therapy can reduce the amount of HIV in the body until it is 'undetectable' in a viral load test which greatly reduces the risk of infecting an HIV-negative partner. The couple also used condoms at all times except for when the ovulation cycle was such that it was possible to fertilise an egg.

82 Sero-discordant means that one partner in the couple is HIV negative and the other is HIV positive.

83 Wulfsohn, Pendry and Bodenstein, Conversations, 15.

84 Ibid., 27, 43.

85 Ibid., 11, 51.

86 Ibid., 23.

87 Ibid., 39.

88 Ibid., 15.

89 Nattrass, Mortal Combat, 5.

90 Okwui Enwezor, Snap Judgments: New Positions in African Photography (Gottingen: Steidl, 2006), 17.

91 Treichler, How to have Theory in an Epidemic, 106.

92 Enwezor, Snap Judgments, 11.

93 Wulfsohn, Pendry and Bodenstein, Conversations, 27.

94 Interview with Pieter Hugo, Cape Town, 10 May 2012; Interview with Paul Weinberg, Cape Town, 24 February 2012.

95 Interview with Gideon Mendel, Cape Town, 2 December 2010.

96 Interview with Gisele Wulfsohn, Cape Town-Johannesburg, 4 May 2011.

97 Steve Mayes and Lyndall Stein, Positive Lives: Responses to HIV - A Photodocumentary (London: Cassel, 1999).