Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Kronos

versión On-line ISSN 2309-9585

versión impresa ISSN 0259-0190

Kronos vol.38 no.1 Cape Town ene. 2012

ARTICLES

Picturing the beloved country: Margaret Bourke-White, Life Magazine, and South Africa, 1949-1950

John Edwin Mason

History Department, University of Virginia

ABSTRACT

In 1949 and 1950, the pioneering female photojournalist Margaret Bourke-White spent five months in southern Africa, producing four photo-essays for Life, one of America's most widely read magazines. Two of the essays, which dealt with South Africa in particular, were Americans' visual introduction to apartheid. The first essay depicted the dedication of the Voortrekker Monument and naively reproduced Afrikaner nationalist ideologies. Appearing several months later, the more substantial of the two essays was a surprisingly vigorous condemnation of racial oppression and labour exploitation at the beginning of the apartheid era. While it remains one of the most compelling photo-essays ever to appear in Life, the decision that Bourke-White and her editors made to avoid showing or mentioning black activism undermined its analysis. The close ties between labour unions, black political groups, and the Communist Party of South Africa made the subject taboo in the strongly anti-communist political climate of post-war America.1

Somewhere high above Senegal, aboard a New York-bound airliner, Margaret Bourke-White typed a letter to a friend. Only hours earlier she had completed a lengthy Life magazine assignment in southern Africa, and as she wrote, her pent-up emotions erupted in a white-hot fury.

'I don't know where to begin about South Africa,' she said. 'I'll have to get further away and sort out my impressions. But it's left me very angry ...' As she continued, her words began to tumble over each other in their rush toward the page.

... the complete assumption of white superiority and the total focusing of a whole country around the scheme of keeping cheap black labour cheap, and segregated, and uneducated, and without freedom of movement, and watched, and hunted, and denied opportunity. And all thru such a mist of fulsome phrases, whether it's the vote, whether it's a clean house, whether it's a chance to go to school - the patronizing cover-all phrase 'he's not developed enough for it.'2

A day later - 15 April 1950 - she was more reflective, but still incensed by the injustice she had seen during her five months in southern Africa. Writing now from somewhere 'Between Lisbon and the Azores,' she directed her anger at white South Africans. By the end of her stay, she wrote

... it was hard for me to be even polite to people any more. In the beginning I had to be, for it was a very hard and diplomatic job I had to do .

I was often reminded ... [of] the danger that the well-intentioned, ineffective 'liberal' can do. ... I met many people whose instincts were pretty correct, and yet who deep down fell into the white supremacy habit of mind, and by their seeming liberalism did much more harm than good ...3

The woman who wrote these words was neither black nor a campaigner for racial justice. She was one of most famous photographers - one of the most famous women - in the world. Bourke-White's work as a photojournalist, especially in the United States during the Great Depression and in combat during World War II, catapulted her to the top of her profession and into the public imagination. As her biographer, Vicki Goldberg, writes, her 'name, face, and photographs were known to millions', Hollywood based movies on her life, and women everywhere regarded her as their ideal. She was 'a true American heroine, larger than life - perhaps larger than Life.'4

Goldberg's last claim is an exaggeration. Life towered above any mere mortal. It was 'perhaps the most popular magazine in American publishing history' and was nearing the peak of its reach and influence at the time Bourke-White was working in southern Africa.5 In the 1950s, fully '21% of the American population over 10 years of age - 22.5 million people' saw each issue.6 Most of those millions were precisely the sort of white middle- and upper middle-class readers that the magazine's advertisers wanted most to reach. Life and its sister publications, Time and Fortune, made their founder and owner, Henry Luce, a force to be reckoned with in American politics.7

Bourke-White's African assignment was by no means the product of an eccentric editor's whim. Luce, who had coined the phrase 'The American Century' in a 1941 Life essay, believed that his magazines had a duty to educate Americans about the world they were destined to lead.8 Life routinely published stories on Asia, Africa, and Latin America, as well as places more familiar to its readers. Bourke-White published four photo-essays in the magazine as a result of her work in southern Africa. The two most substantial were most Americans' visual introduction to apartheid, the system of racial oppression and exploitation that would soon become infamous around the world. (The others concerned the neighbouring British colony of Bechuanaland.) The second and longer of the South African essays, 'South Africa and Its Problem',9 is a compelling analysis and explicit condemnation of racial injustice at the dawn of the apartheid era. The photos that Bourke-White made and the text that she influenced have lost none of their power more than sixty years after their publication. Although unjustifiably neglected, it remains one of the most significant stories that Life ever published.

While 'South Africa and Its Problem' was the culmination of Bourke-White's research and photography in the country, 'South Africa Enshrines Pioneer Heroes' was the beginning.10 Published in January 1950, about six weeks after she arrived in the county, it could hardly have been more different from the later essay. Bourke-White's photos of the dedication of the Voortrekker Monument and the text that accompanied them showed no trace of the anger and insight that she expressed so forcefully at the end of her stay in the country. Although visually appealing, the essay failed to address the very questions that gave 'South Africa and Its Problem' its power.

Bourke-White had been in the South Africa for only a short time when, in mid-December 1949, fate dropped the Voortrekker Monument dedication into her lap.11 It was the greatest peacetime spectacle that the country had ever seen: four days of pageants, concerts, and speeches in a dramatic setting; a crowd of 250000 people in attendance, many dressed in quaint nineteenth-century costumes; perfect weather for photography. Bourke-White would have been forgiven if she had thought that the ceremonies, which fit Life like the proverbial glove, had been staged just for her.

More than a mere spectacle, the dedication was also a highly charged political event, bringing together the most prominent winners and losers of the previous year's bitterly fought parliamentary elections. Following a ten-year period of what Albert Grundlingh calls 'feverish Afrikaner nationalism',12 the victorious National Party ousted the United Party from power by appealing to its constituents' accumulated fears and grievances and by promising to uplift the Afrikaner people.13 It immediately set to work planning and implementing apartheid, which was designed to preserve white rule and Afrikaner culture forever by deepening and reinforcing racial segregation.

The National Party's 1948 victory put it in a position to impose its understanding of the meaning of the Voortrekker Monument and Afrikaner history on the dedication ceremonies. To a large extent, it succeeded. From the time of its dedication until the National Party lost power in the 1994 elections, the monument has been seen primarily - although not exclusively - as a symbol of triumphant Afrikaner nationalism.14

The monument memorialises two turning points in the colonial conquest of southern Africa: the execution of a party of Voortrekkers, led by Piet Retief, at the command of Dingane, king of the Zulu, in early 1838; and the devastating, retaliatory defeat of a Zulu army by another party Voortrekkers, at the end of the year. The Voortrekkers' victory opened large tracts of land in what became the British colony (and later the South African province) of Natal to white settlement. It was also a milestone on the road to the subjugation of the Zulu kingdom by the colonial state. This heritage of white supremacy was something that the pre-war government, which financed the monument's construction, believed that both English-speaking whites and Afrikaners could embrace. Building the monument, however, was 'a protracted affair spanning 18 years from its initial planning in 1931 to its completion in 1949.15 By the time of the dedication ceremonies, the political landscape had shifted and so had the generally accepted meaning of the monument.

It would be unfair, of course, to expect Bourke-White to have grasped the history and politics that surrounded the monument. She had never been the country before, and she did not speak Afrikaans, the language in which virtually all of the proceedings were conducted. She was on much firmer ground, however, when it came to photojournalism. She knew how to make pictures that would grab the attention of Life's readers and tell them a whopping good story.

Like all of Life's photographers, Bourke-White understood that readers flipped through the magazine, absorbing it in bits and pieces, rather than reading it straight through like a book. Photographers also knew that a riot of images, from the extremely serious to the utterly frivolous, competed for the reader's attention. Large and small, photos of celebrities and politicians, cute kids and sleek new cars, athletes, soldiers, soup, and television sets dominated the magazine, overwhelming the text and occupying most of the space on almost every page.16 Photographs were the magazine's primary carriers of information, the medium through which Life told its stories and advertisers sold their goods.17 A successful photo was both legible and dramatic, capable of cutting through the clutter, catching the reader's eye, and making its meaning plain.

In 'South Africa Enshrines Pioneer Heroes', Bourke-White's ability to stop readers in their tracks and to tell them a gripping tale is readily apparent. Her seventeen black and white photos, spread over seven uninterrupted pages, translated the Voor-trekker Monument's dedication ceremonies into an idiom that was both compelling and readily accessible to her American readers. At the same time, however, the photos uncritically reproduced the heroic myths of colonial conquest and Afrikaner nationalism.18

All photos, including Bourke-White's, are susceptible to multiple readings. That insight is not simply the conventional wisdom of photo criticism; it is a reality with which photojournalists have always had to cope. A key to Bourke-White's success at Life was her ability to make photos which resisted, to a large degree, the photograph's inherently elusive nature. She created images in which the message was, in Goldberg's words, 'instantly telegraphed'. This was, in part, a product of her gift for finding symbolic individuals or events with which she could create a 'dramatic simplification' of her subject.19

Although Bourke-White meticulously directed many of her photos,20 neither she nor Life's editors were interested in drawing attention to 'the constructed nature of photographs'. The authority with which her images and, in fact, all of Life's photoessays spoke, depended on the widely held belief that photographs 'transparently represent the real', to use Chris Vials' phrase.21 Seeing was believing, Life asserted; a picture was worth a thousand words. Yet words were also important parts of every Life story. A photo's caption and the essay's text were additional ways in which editors attempted to contain the ambiguity of the image and impose a preferred meaning. While Life's photographers and editors sometimes found themselves at odds, there is no evidence that there was any tension between Bourke-White and the men who wrote and edited her South African essays.

When readers turned the page to Bourke-White's essay on the Voortrekker Monument dedication, they saw precisely the sort of dramatic, symbolic flourish that Goldberg describes. A large image of two flag-bearers mounted on white horses occupied the upper two-thirds of the page.22 The strong graphic design placed the horsemen in the centre foreground, trotting directly at the viewer and evoking a sense of valour and chivalry. These associations were underscored by the bold headline beneath the image - 'South Africa Enshrines Pioneer Heroes'. While alternative readings of the photograph were certainly possible, anyone who attempted to make one would have had to fight through visual and literary rhetoric that insisted on the preferred meaning - heroism, sacrifice ('enshrine'), and an implied analogy with American pioneers who, in the language of the day, 'conquered the West'.

The essay's interior photos reinforce the messages of the opening page.23 A night photo of a torchlight ceremony might have stuck a discordant note, echoing Nazi rallies at Nuremburg only a decade earlier, had it not been for the caption's reassurance that the 'Voortrekker Girls' holding the torches were merely the equivalent of American Girl Scouts.24 An image of black women bending over cooking pots, preparing a meal for whites, depicts but does not critique the implied racial hierarchy - a hierarchy with which Americans would have been familiar. A photo showing young people gathered around a stand that is selling 'American hamburgers' and Coca-Cola (according to its clearly legible signs) made the Americanization of the dedication ceremonies explicit and drove home the point that the participants were, in essence, little different from the white middle-class audience that Life photographers and editors always kept in mind.

The essay's closing pages brought together Bourke-White's embrace of colonial and Afrikaner nationalist mythology and the desire that she likely shared with her editors to Americanise the ceremonies.25 The most important of the photos occupied an entire page. Printed in heavy tones, but with a burst of light placed almost exactly in the middle, it was an image, the caption told the readers, of 'the tomb of a pioneer hero, Piet Retief'. On the facing page, a smaller photo depicted an interior bas-relief and showed Retief at the moment that he lost his life to a Zulu soldier - 'a native', according to Life - who treacherously attacked him from behind. The essay ended, then, with solemn images of savagery and sacrifice. Retief died at the hands of a 'savage', but, as in the United States, white civilization ultimately triumphed, a victory to which the monument itself bore witness.

Strictly speaking, Bourke-White and her editors were wrong about the dark structure on which the sun's rays came to rest. It was, and is, a cenotaph, not a tomb. But they correctly recognised that it was the monument's centrepiece, the symbolic tomb of Retief and the other Voortrekkers who were killed at Dingane's command. The fact that a shaft of sunlight struck the cenotaph so precisely was no accident. As Life's text informed readers, the effect was the result of the architect's 'half-mystical, half-mechanical scheme' to glorify 'the pioneer Boers'. A lens in the monument's roof 'is so placed that the sun's rays are shafted deep into the monument at 12 noon on Dec. 16', the day that Retief's death had been vindicated by the Voortrekker's victory over the Zulu.26

The essay's photos and text told a unified story: heroism and sacrifice, in the past; a self-confident and unified people, in the present; blacks securely in their places, whether as savages or servants; a history that resonated strongly with America's. It was a story that was almost entirely congruent with the political mythology of Afrikaner nationalism.

Neither Bourke-White nor her editors at Life could have fully grasped the complex dynamics of South African politics at play at the monument's dedication. Unable to speak Afrikaans, the language in which the ceremonies were conducted, it appears that she had to rely on fellow journalists, officials connected to the dedication ceremony, and, perhaps, her photographic assistant to explain the event and its meaning to her.27 In addition, there is no evidence that either Bourke-White or her editors considered the essay to be serious investigative journalism. But these factors do not completely explain the essay's political naivete. After all, South Africa and the injustices endured by blacks weren't unknown quantities in the United States.

As James Campbell and others have shown, South Africans and Americans, both black and white, have shared a mutual fascination with each other for nearly two hundred years. '[T]the shared fact of white supremacy', Campbell writes, 'has produced some extraordinary parallels ... while providing a foundation for a host of transatlantic encounters In fact, an American missionary, the Rev. Daniel Lindley, accompanied the Voortrekkers on their journey into the interior.28

A number of factors intensified American interest in South Africa in the years immediately preceding Bourke-White's visit. During World War II, American exports to the country soared and remained high for several years after its end. Direct investment followed suit.29 Bourke-White might not have been aware of business trends, but she could not have avoided the excitement surrounding the publication of Alan Paton's Cry, the Beloved Country, his now classic novel about racial injustice in South Africa. Published in the United States to much acclaim, in 1948, it became an instant best-seller and, within months, had been transformed into a Broadway play.30

The 1948 parliamentary elections drew further attention to South Africa. Time magazine, Life's sister publication within the Luce empire, covered the elections extensively - and with horror. It lamented the defeat of Jan Christian Smuts, 'the wise, venerable, oak-solid Prime Minister of the Union of South Africa' and deplored the success of Prime Minister Daniel Malan's 'Nazi-aping Nationalist government'. When the National Party 'came to power last spring', Time wrote in December 1948, 'it promptly launched an anti-Negro, anti-Semitic propaganda campaign of which Goebbels himself would have been proud.'31

Life itself had previously published at least three photo-essays about South Africa, but neither Bourke-White nor her editors seem to have consulted them. If they had, they would have discovered that two in particular took a dim view of race relations in the country. 'South Africa: It Has Always Produced Great Warriors,, which appeared in 1943, was largely concerned with the nation's contribution to the Allied war effort. It did, however, touch on race and ethnicity. The article's text noted that '[b]lacks do all heavy labour in South Africa. ... [This] has left the white man a supervisor with leisure to brood, argue and fight'. The article was especially hard on Afrikaners, describing them as 'one of the world's freak peoples. ... Fanatically pious members of the Dutch Reformed Church, they began to expand with a Bible and a gun. ... Toward natives the Boers have an ancient hostility and an iron policy of white supremacy.'32

In 1946, only three years before Bourke-White arrived in South Africa, Life published 'Boer Farmer: South African Clings to His Forefather's Soil and Beliefs', an eight-page photo-essay about an Afrikaner farm family and the African workers it employed. As in Bourke-White's story about the Voortrekker Monument, Americans were invited to identify with South Africans, but here the association was not complimentary. 'There are many parallels between the conservative, backward Boer regions and America's own South', Life wrote. 'The Boers are ardent believers in white supremacy and their racial discrimination is so highly organised that no black may travel without a pass.' N.R. 'Nat' Farbman, a photographer on Life's staff, depicted a deeply patriarchal Afrikaner lifestyle, while representing Africans as exploited yet dignified farm workers. Life left no doubt that its sympathies were with the 'oppressed, restricted, resentful' blacks.33

The reasons behind the failure of 'South Africa Enshrines Pioneer Heroes' to address the darker meanings of the Voortrekker Monument and the dedication ceremonies are likely to remain obscure. There is no evidence that either Life or its photographer were consciously pursuing a pro-National Party political agenda. While the magazine had recently criticised race relations in South Africa, it is too much to expect ideological consistency from writers and editors who were engaged in the frantic business of producing a weekly magazine of news and entertainment that regularly sprawled over 150 or more pages. Like all popular media, the magazine was full of contradictions that, in most cases, neither readers nor writers registered con-sciously.34 Circumstances did not require 'South Africa Enshrines Pioneer Heroes' to be anything other than a visually compelling photo-essay that was sure to resonate with Life's readers.

Bourke-White's thinking must also be the subject of informed conjecture. She was politically progressive, having earned a reputation as somebody whose sympathies were on the side of the poor and the oppressed, including victims of racial discrimi-nation.35 While no diaries from the period or letters that she wrote while in South Africa seem to have survived, the chapter devoted to South Africa in her autobiography describes and condemns the country's many forms of racial injustice. It does not, however, mention the Voortrekker Monument.36 The simplest explanation for the essay's tone is probably the best: she was new to the country and saw more than she understood. And what she saw at the dedication was, according to South African journalist Piet Cillie, Afrikaners ... at their most attractive'. Writing at the time, Cillie (who Hermann Giliomee notes would later be known for his cynicism) declared that the ceremonies took English-speaking journalists by surprise. 'They did not realise that young Afrikaners could sing so well, that Afrikaner women could dress so well, that Afrikaners could perform such folk dances, and that Afrikaner history could be presented so irresistibly ...'37 New to the country and eager to engage with its people, Bourke-White may well have been seduced by the occasion.

Many times in the weeks to come, I thought of the country as a mirage; things are not what they seem. Margaret Bourke-White38

She did not stay seduced long. Letters that Bourke-White wrote immediately after leaving the South Africa, in April 1950, showed that her understanding of the country had deepened considerably in the months since she photographed the ceremonies at the Voortrekker Monument. In them she described the injustices that blacks endured as well as the 'hypocrisy and inhumanity' of whites. Writing to a friend, she said that she had managed to capture much of what she learned on film. 'I have many photographs to cover all these things. I did ... an enormous amount of maneuvering to get them, as the white So Afr's are terribly sensitive to criticism as well they might be. But I got awfully good stuff, I think.'39

Bourke-White's 'awfully good stuff' was the raw material that ultimately produced 'South Africa and Its Problem', an interpretation of South African society that put the exploitation and oppression of blacks at the heart of its analysis. Once again the existing sources say little about her day-to-day experiences in the country and do not supply the evidence necessary to fully explain the transformation in her thinking. It is clear, however, that she traveled widely within South Africa and visited South African-controlled South West Africa (now Namibia) and the British protectorate of Bechuanaland (now Botswana). She photographed gold miners at work deep underground, convict labourers being marched at gunpoint to farmers' fields, African men queuing at pass offices, African women in rural homesteads, and affluent whites enjoying a day at the beach. In addition, she met and photographed a wide range of people - cabinet ministers, business executives, labour organisers, political activists, and ordinary men and women of all colours.40 Life correspondent Robert Sherrod's description of the energy and intelligence with which she went about her work during an assignment in India sheds light on her time in South Africa. He recalled that she 'photographed, interviewed, and charmed' scores of individuals and 'knew more about India after three weeks than most reporters learn in three years. She ha[d] more energy than anybody else in India, and she work[ed] like hell in spite of the deadly heat.'41

'South Africa and Its Problem' is the work of a sophisticated photojournalist in her prime. Appearing in September 1950, five months after Bourke-White returned to the United States, it was one of the longest photo-essays that Life ever published. Its sixteen pages were uninterrupted by advertisements and contained thirty-five photographs - five in colour, the rest in black and white. (By comparison, W. Eugene Smith's 'Country Doctor', one of the most renowned of Life's photo-essays, was twelve pages long and contained twenty-eight black and white photos.42) The photos and text43 speak forcefully about the exploitation, poverty, and indignities that blacks endured, about the wealth that they created but did not enjoy, and about the political and economic foundations of white supremacy.

But a glaring omission prevents the essay from being a fully convincing portrait of mid-century South African society. By choice rather than by chance, Bourke-White and her editors avoided any reference to black political or labour activism and to the emerging urban culture of black modernity, in all its 'vitality, novelty, and precariousness', to use Paul Gready's phrase.44 Instead, the words and images depict Africans as an essentially rural, pre-modern people, trapped between a collapsing 'tribal' culture and a modern industrial society with which they could not fully cope. Change would be slow to come, the essay suggested, because blacks were incapable of helping themselves and because they had few allies among whites.

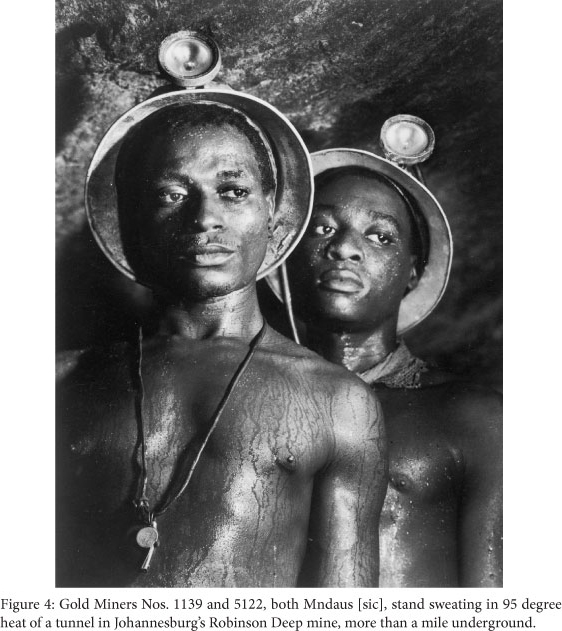

The essay opened with a powerful image that demonstrated its strengths and foreshadowed its weaknesses. A genuinely iconic photograph, it was one of Bourke-White's favourites and remains one of her best known.45 Occupying nearly three-quarters of the page, it had an almost visceral presence that would have stopped Life's readers in their tracks. Vicki Goldberg describes it well.

It is pure Bourke-White. Shot close up from slightly below, the men become monuments crowding out of the frame ... The lighting is richly sculptural, quietly dramatic, romantic. The two faces, noble and melancholy, are circled by the miners' hats as if by metal halos; on some symbolic level these men represent the downtrodden who suffer but endure.

The photo is 'pure Bourke-White' not only in its monumentality, but also in the way that she has drained the image of as much ambiguity as possible, in large part by transforming the men into symbols. (The caption identifies them as 'Gold Miners Nos. 1139 and 5122', the identification numbers that the mine had assigned them. There is no indication in Bourke-White's papers or autobiography that she ever learned their names.) In her autobiography, she described having seen the men dancing during one of the shows that miners staged on Sundays for their own entertainment as well as for white spectators. She immediately recognised that they were examples of the 'typical person or face that will tie the picture essay together in a human way' that she was 'always looking for'. The men, that is, would embody what she wanted to say not about them as individuals but about black South Africans generally and about their country.46

The image, like all portraits, should be seen as the result of collaboration between the miners and the photographer. While Bourke-White directed the poses and, with an assistant, arranged the lighting,47 there is no reason to believe that the men were mere putty in her hands. As Edward Steichen, one of the few American photographers of the day who could rival Bourke-White in stature, is reported to have said, 'A portrait is not made in the camera but on either side of it.'48 The partnership was not, however, a partnership of equals. Bourke-White was wealthy, powerful, and white; the men were not. She selected which of two similar exposures would see the light of day; they did not.49 Nevertheless the American woman and the two South African men together imprinted photo's multiple meanings so strongly that readers would have had to make a conscious decision to resist the photo's representation of dignity, strength, and masculine beauty. At the same time, however, the miners' averted eyes would have sent the disempowering message that Goldberg captures in her phrase 'the downtrodden who suffer and endure'. Bourke-White showed the men's strength and at the same time implied their weakness. She represented them as strong but passive, as the oppressed and exploited who did not fight back. She designed the photo to serve as a metaphor for the condition of black South Africans as a whole. In doing so, she chose to get things half right.

Underneath the iconic image, a pair of headlines introduced further complications. The larger of the two announced, ambiguously, the essay's title and subject: 'South Africa and Its Problem'. Below it, a sub-headline identified South Africa as 'a black land' that was subject to 'white rule' which deprived blacks of 'human liberty'. Taken alone, the headlines seem to have positioned blacks as the country's legitimate owners and whites as interlopers, implying that the problem is 'white rule'. The size and strength of Bourke-White's photograph, hovering directly over the title, virtually insisted on an alternative reading: the men themselves and, by extension, the people that they represented were the problem. Underneath the headlines, the text made it explicit. The article, Life told its readers, is the result of Bourke-White's exploration of 'South Africa's great issue and dilemma, the black problem'.50

It should come as no surprise that Life chose to frame the issue as 'the black problem'. In the United States, the use of the phrase (and its variant 'the Negro problem') to encompass the racist institutions, ideas, laws, and customs to which blacks were subjected stretched well back into the nineteenth century. In the midtwentieth century, it was still at the heart of the American racial discourse. Gunnar Myrdal's influential study of American race relations, An American Dilemma: The Negro Problem and Modern Democracy, had been published only six years before Bourke-White's essay appeared.51 Life itself used the phrase in a 1949 article on segregation and racial discrimination in the South.52 Blacks as well as whites embraced the terminology. In 1904 Booker T. Washington edited and published a collection of essays titled The Negro Problem: A Series of Articles by Representative American Negroes of Today.53 It was a trans-Atlantic discourse. In 1920, for instance, the black South African educator D.D.T. Jabavu, who admired Washington and had visited him in the United States, published The Black Problem: Papers and Addresses on Various Native Problems.54

Despite its bi-racial pedigree, framing the issue as 'the black problem' shifted attention away from the thoughts and deeds of whites and toward black people, as if they themselves were the problem. This was something that W.E.B. DuBois put his finger on in 1903, when he famously remarked that 'being a problem is a strange experience, - peculiar even for one who has never been anything else, save perhaps in babyhood and in Europe.'55 By the 1960s, African-American activists and intellectuals were trying to redirect debates about race by publishing books such as The White Problem in America.56 To his credit, Myrdal anticipated this terminological turn by making it clear in the text of his book, if not in its title, that the problem resided 'in the heart of the [white] American', who allowed his racial prejudice to overwhelm his commitment to the democratic ideals enunciated in the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence.57

Throughout 'South Africa and Its Problem', Bourke-White's photos and Life's text reflected the tensions that were present on its first page. Africans embodied a problem that someone else would have to solve. With few exceptions, Bourke-White's photos cast them in one of two sometimes overlapping roles, as workers and as 'natives'. As workers, they were victimised and helpless. As natives, they represented a vanishing, authentic Africa, besieged and threatened by the white man's world. Nowhere were Life's readers encouraged to identify with Africans. Instead they were implicitly urged to identify with South African whites, with whom they shared a common problem. The result was a sympathetic but ultimately circumscribed analysis of South African society.

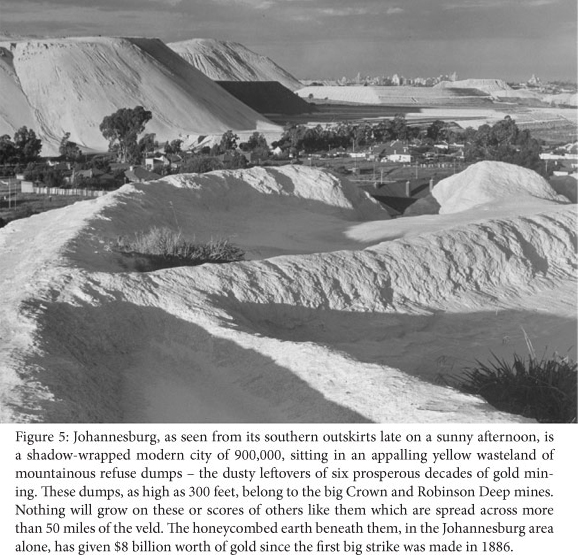

Scores of black male workers inhabited the essay's photos. (In Life's South Africa, workers were never women.) Bourke-White showed them being recruited to jobs in the gold mines, toiling underground, relaxing in overcrowded barracks, digging for diamonds, marching - as prison labourers - toward farmers' fields, and, in the case of a boy of about eleven years of age, drinking a tot of wine in a Cape vineyard. The photos emphasised exploitation, on the one hand, and degradation, on the other. A large photograph on the first double-truck spread made it clear that the wealth that the men (and boy) produced enriched whites, not blacks. Underneath a headline, 'Whites Won the Land, the Blacks Work It', mine dumps in the foreground framed the skyscrapers of downtown Johannesburg in the distance.58

The essay was interrupted by four pages of colour photographs that, at first glance, seemed to have little to do with the gritty black and white photography and hard-edged political and economic analysis that came before and after. Within these pages, the essay's narrative of racial oppression and labour exploitation disappeared. Instead, the photos offered readers a glimpse of what seemed to be an authentic Africa, virtually untouched by white civilization. Unlike the black and white photos, in which African women were rarely present, women dominated these pages. They were the only subjects in four out of the five photos, suggesting that Bourke-White saw them as the keepers of a fading tradition. For instance, three Thembu women - a 'Great Wife' and two 'subordinate wives', the caption told readers - were seen applying make-up made from clay while wearing blankets that Bourke-White and Life's readers would probably have assumed were 'traditional' garb. In another photo, a young Thembu man, wearing ear-rings and bracelets and draped in a blanket, poses for the camera while lying on the floor. These images descend from the genre of 'native types' that had originally been produced to serve the agendas colonial administrations and western ethnographers by cataloging evidence of ethnic particularities and racial characteristics. They soon entered the realms of commercialism, art, and photojournalism. Circulating as collectable postcards, as well as in books, magazines, and newspapers, native studies allowed Europeans to marvel at their new colonial subjects.59

'Native types' were instrumental in the invention of 'the native', which, as Christopher Joon-Hai Lee has pointed out, was a 'central organizing principal in colonial societies'. The fundamental distinction was between 'native and non-native', between those who were a part of the political community and those who were not.60 The category of 'native' was essentially a racial one (whites born in the colonies were never 'natives'), but the idea had a cultural component as well. It suggested that natives were outside of history, as colonisers conceptualised it. Most importantly, they did not progress. They were trapped not so much in the past as in an unchanging tribal present. One could imagine an anthropology of native peoples, but not a history. Natives were exotic and colourful, and as workers they were certainly useful, they could never be truly at home in the modern world.

Yet Bourke-White's photos at least hinted at another possibility - that Africans could have histories and embrace modernity. The Thembu man in the blanket was, in fact, a miner, the caption told readers, awaiting a medical examination in Johannesburg. In other photos, Herero women were depicted wearing costume jewelry, as well as dresses that represented distinctly historical 'traditions'. The jewelry was store-bought and the dresses were fashioned after those that had been worn by the wives of nineteenth-century German missionaries who proselytised the Herero. A black and white image showed Herero women and children seated in a courtyard in front of shanties in a Windhoek 'Native location'. One of the women was posed as if using a sewing machine, a symbol of modernity.61

Neither these colour photographs nor the accompanying text further explored the possibility of an African history and an emerging African modernism. In some ways the photos foreclosed them. With the exception of the photograph of the Windhoek location, Bourke-White posed her subjects against neutral backgrounds and framed them so tightly that there was virtually nothing else to see. Removed from any meaningful context, readers could only know the women and the Thembu miner by their 'traditional dress' and their dark skins. They were thus, as a caption insisted, 'natives'.62 Bourke-White did treat these subjects with respect. Her photos of the Herero women were particularly imposing, conveying 'a look of proud elegance', as one of the captions put it.63 Ultimately, however, she represented her subjects as people from a world that was separate and distinct from the modern industrial society that Life's readers shared with white South Africans.64

In many of the essay's black and white photos, men were depicted simultaneously as workers and 'natives'. Gold miners, for instance, were seen labouring underground, on the one hand, and performing 'a violent tribal dance' above ground, on the other. A photo of mining recruits identified them as 'tribesmen' and showed them, in an office setting, wearing blankets rather than western clothing. Another photo showed one of the 'Amalaita Fights', which, according to the caption, were held under police supervision every Sunday afternoon in Pretoria for 'recreation-starved Natives'.65

In Bourke-White's photos, there were few signs that blacks are truly of, rather than temporarily in, the modern world. One photograph did show neatly dressed African men, wearing sport coats and fedoras, crowding into a pass office.66 They would not have looked out of place in Detroit. The photo hinted at the existence of a cosmopolitan black urban culture, but it was only a hint.

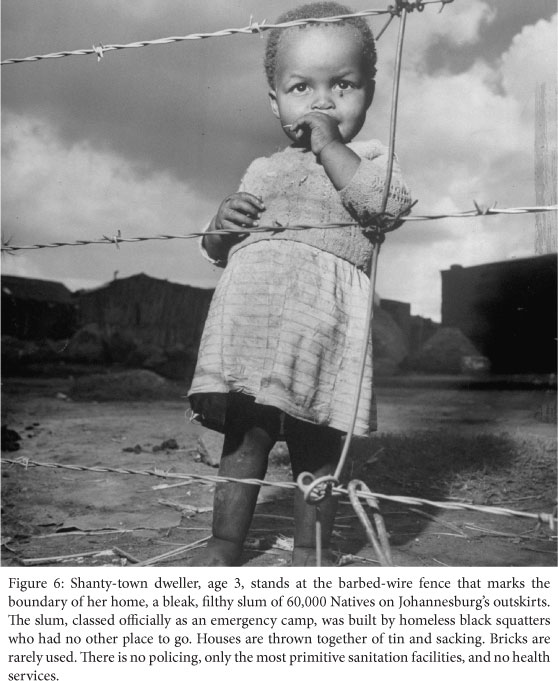

The final large photograph in the essay offered Africans a role besides worker and native - that of helpless victim.67 Unapologetically sentimental and almost transparently manipulative, it hammered home its meanings. Bourke-White photographed her subject, a three-year-old girl, in a squatter camp on the outskirts of Johannesburg. In the pages of the magazine, she was monumental. Photographed from an extremely low camera position, the three-quarter-page image made her seem to tower over anyone looking at the page. A wire fence separated the child from the photographer and from readers as well, suggesting that she was to be pitied, but not identified with. She wore no shoes, and the ground surrounding her was littered with trash. A blemish on her left lower eyelid looked like a tear. She was an innocent - a pure victim - who could not help herself. This manifestly symbolic photograph was the essay's last image of a black person.

Bourke-White's photos repeatedly underscored the distinction between the poverty and impotence of the black community and the wealth and power of the white community. The second double-truck contained a group portrait of Prime Minister D.F. Malan's cabinet that emphasised the men's status and self-confidence. A photo of interior minister T.E. Donges showed him playing cricket in the luxurious surroundings of Cape Town's Newlands Cricket Grounds. Margaret Ballinger, who represented Africans in Parliament because, by law, they could not represent themselves, was seen talking to some of her constituents. (Ironically, most of her supposed constituents actually seem to be Coloured stevedores.) Policemen appear in three photos, conducting a raid on illegal beer brewers, escorting prison labourers to work, and watching over the 'Amalaita' fights.68

In tone and in substance, the essay's text could hardly have been more distinct from that of the Voortrekker Monument story. It was unequivocal in its condemnation of Malan, the National Party, and its policy of apartheid. Using emotionally loaded language it called Malan 'the high priest of apartheid' and claimed that he 'hoped for Nazi victory in World War II'. Apartheid, the National Party's 'new doctrine of segregation' was, it said, the result of 'an unabashed outbreak of racialism and nationalism [among] South African champions of white supremacy'. It was also a misguided attempt to solve 'the black problem'. Colonial conquest had deprived Africans of most of their ancestral land, making it impossible for the vast majority to support their families from farming. In addition the government required them to use 'the white man's money to pay the white man's taxes'. As a result, whites had forced Africans to 'work for the whites to live, and the whites must always live dependent on the black millions swarming among them.' Blacks and whites were trapped in a rough and unequal embrace.69

Neither Bourke-White's photos nor Life's text offered a solution for the South African problem. Whether as workers, 'natives', or victims, Africans had no means of challenging white supremacy. South Africa's handful of 'educated and intelligent blacks' had 'no voice because they have neither a vote nor more than token representation'. Only whites had the power to end racial injustice, Life said, but they either would not or could not act. While some whites, 'both Afrikaner and English', abhorred 'the government's policies on moral grounds', they were immobilised, fretting just as much about 'a counter black nationalism, which may explode in [a] terrible racial war' as about racial injustice.70

The text closed with a passage from Alan Paton's Cry, the Beloved Country, taken from one of the most hopeless and despairing moments in the novel. Speaking from the perspective of ordinary white South Africans, Paton could see no way out of the South African dilemma:

... we fear not only the loss of our possessions, but the loss of our superiority and the loss of our whiteness ...We do not know, we do not know. We shall live from day to day, and put more locks on the doors ... And our lives will shrink, but they shall be the lives of superior beings ...71

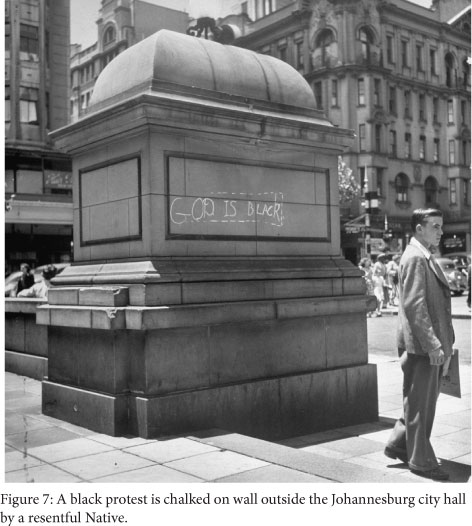

Below this passage was a tiny photograph, the last image in the essay and by far the smallest. An ornamental plinth, located outside the Johannesburg city hall, virtually filled the frame. On it, somebody had scrawled a slogan in chalk: 'God is Black'.72 Life explained the scene by saying that the words were written by 'a resentful Native'. It was a plausible explanation, but others would have held up equally well. It might have been written by a bitter native or an ironic one, a native-provocateur or a native surrealist. There was, and is, no way to know. The photo was an enigmatic outlier in an essay that elsewhere telegraphed its messages.

It is possible that the photo was an inside joke, signaling that Bourke-White and her editors knew things that they hid from their readers. There can be little doubt that they recognised that black South Africa had entered a period of tremendous political and cultural dynamism and that they withheld this knowledge from their readers. The evidence for this is in the few existing words that Bourke-White wrote while she was in the country and the many she wrote after leaving it. Her reading of the graffiti scrawled on the plinth, for instance, was significantly different from the one suggested by Life's editors in their caption. In a note to her editors, written while she was still in South Africa, she said that it was '[s]ymptomatic of the growing racial self-consciousness of the black folk of South Africa ...'73

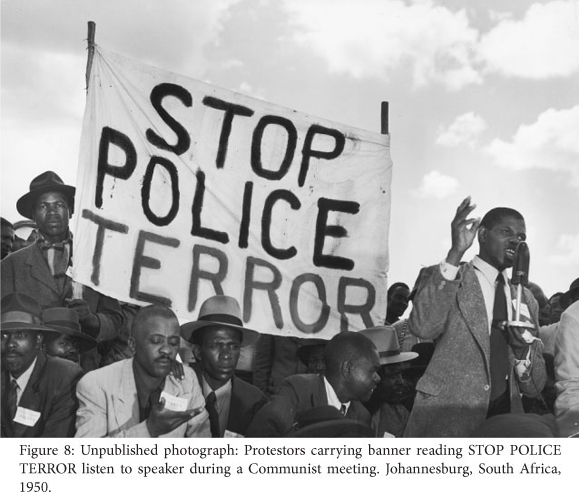

Bourke-White was aware of the changing self-consciousness because of the time that she had spent with black activists and intellectuals. In a letter that she wrote immediately after leaving South Africa, she mentioned that she had seen 'a good deal of the people who are trying hard to organise [racially mixed] unions ... Such earnest people, trying so hard, and so little equipment to do it with." (She was probably referring to the Food and Canning Workers Union mentioned below.) In the same letter, she spoke of her admiration for Africans who had managed to acquire a western education. 'Needless to say, when you meet an educated African, he is usually an extraordinary person ... I met some wonderful people who are doing a great deal despite formidable odds.'74 In her autobiography, published thirteen years after her time in South Africa, she spoke about the 'quiet heroism' of some black diamond miners whom she had met who were teaching other miners to read and write. She also described a visit to a shantytown where she saw 'a Sunday mass meeting in which the people dared to carry banners with the slogan Stop Police Terror, and fiery speakers denounced police brutality.'75 None of this knowledge appeared in 'South Africa and Its Problem'.

Bourke-White's images provided even more persuasive evidence than her words. She not only saw the mass protest meeting, she photographed it. The Getty Images archive of Bourke-White's photographs contains two photographs from that meeting. One shows a group of men seated behind a speaker and in front of a banner that reads 'Stop Police Terror'. Pinned to their jackets are badges bearing the slogan 'We Don't Want Passes'. Another photo is a portrait of a protestor, identified as Phillip Mbhele, wearing the same badge. The captions tell us that it was a 'Communist meeting'. The photographic record suggests that she spent a good deal of time at the event. Her personal archive at Syracuse University contains numerous outtakes from the same meeting.76 These photos, however, were nowhere to be seen in 'South Africa and Its Problem'.

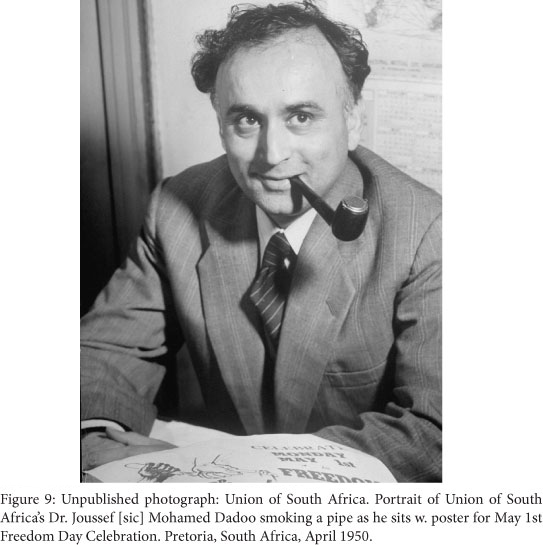

Bourke-White also met a variety of political activists. Among them was Yusuf Dadoo, the President of the Transvaal Indian Congress and a prominent member of the Communist Party of South Africa [CPSA]. In an unpublished portrait that she made of him, a poster that has been turned to face the camera could be seen on his desk. Part of it is clearly legible, and it advertised a 'Celebration, Monday, May 1st, Freedom'. The rest extended beyond the frame, but what can be seen is enough to place this photograph rather precisely within South African political history.

In March 1950, the CPSA, the Transvaal Indian Congress, the African People's Organization, and a sharply divided African National Congress [ANC], held a 'Defend Free Speech' convention to protest the banning of CPSA members, including Dadoo, and the government's introduction of the Suppression of Communist Act. The convention called for a general strike to be held on 1 May to pressure the government to back down from the banning orders and new legislation and to call for higher wages. The strike call was effective, especially in the Johannesburg region. The police turned out in large numbers as well, killing eighteen demonstrators at protests in various African townships in the Transvaal and provoking 'a wave of anger and indignation [that] spread throughout the country'. A now united ANC led the other organizations in calling for a national 'Day of Protest' on 26 June, thus giving birth to Freedom Day.77 Although Bourke-White left South Africa in mid-April, she was on hand for the planning of the May Day protests and saw firsthand the upsurge of black activism.

Bourke-White also photographed a meeting of the multi-racial executive committee of what the caption identifies as the 'Food Canners Union'.78 This is almost certainly the Food and Canning Workers Union, which made a point of finding ways around laws that forbade organizing Coloureds, whites, and Africans in a single union.79 It is also likely that these are the labour organisers that she said that she 'saw a good deal of'.

If Bourke-White and Life had carried through on her insight that there was 'a growing racial self-consciousness' among black South Africans and had included photographs and descriptions of black activism, 'South Africa and Its Problem' would have reached radically different conclusions than it did. Its assessment of labour exploitation and racial oppression might not have changed significantly, and its depiction of the power and complacency of whites might have remained the same. But its assessment of the possibility of change would have reflected some of black South Africa's optimism rather than Alan Paton's hopelessness. Life's readers would have been better prepared to understand the events of the next ten years.

Any explanation of the essay's silences about black activism that rely on racial animus can be dismissed. Bourke-White had a well-earned reputation as a woman of the left and as someone who was hostile to racial oppression. Life was generally more progressive on racial issues than most white Americans of the day, declaring as early as 1938 that racial prejudice was the 'most glaring refutation of the American fetish that all men are created free and equal'.80 Erika Doss notes, however, that Life's support for civil rights was constrained by its aversion to activism. While the magazine backed African Americans' constitutional claims, it failed 'to critically reckon with the complex historical tensions of race, gender, and class in America ...' It believed that 'the problems of inequity, poverty, racism, and alienation' could be solved by 'simply imagining a better country and better world'.81 Here, perhaps, is the beginning of the explanation for the essay's omissions. Believing that racial oppression was primarily a moral issue, it saw no need or room for black political action. As Wendy Kozol points out, even in a five-part expose of segregation, appearing in 1956, the magazine published no 'specific images of African American activism'.82

Life's distaste for black activism does not account for Bourke-White's silence on the issue. While the magazine underestimated the importance of activism, she did not, as is clear in both her photos from South Africa and her writings about it. The problem for Bourke-White, and an additional problem for Life, was not activism, in and of itself; instead it was the activists' political affiliation. Simply put, many of them were communists. In the context of the Cold War and the anti-communist witchhunts that were then a part of the American political landscape, anything tending toward a positive view of communism had become toxic to mainstream journalists and publications.

Having long been associated with the political left, Bourke-White was vulnerable to attacks that labeled her un-American and a communist sympathiser. In the early 1940s, for instance, the Federal Bureau of Investigation put her under surveillance as security risk and potential subversive. She faced condemnation from politicians in Congress as well. In 1944, the House Un-American Activities Committee accused her of being close to groups that promoted anti-American propaganda. Her problems began in earnest shortly after her assignment in South Africa. In 1951, reporters working for Randolph Hearst, Jr., one Luce's press rivals, launched a concerted campaign against her.83

In the atmosphere of the day, even as staunch an anti-communist as Luce could find himself and his magazines under attack. The 1949 revelation that Whittaker Chambers, once Time's foreign editor, had been a secret member of the American communist party put Luce under considerable pressure.84 Under these circumstances, it would have seemed prudent to both the photographer and the magazine that employed her to avoid mentioning the likes of Yusuf Dadoo, the communist party leader, the Food and Canning Workers Union, which had many communists among its organisers and leaders, and the rallies organised by the CPSA.

Bourke-White and her editors may well have believed that they were doing black South Africans a favor by maintaining their silence about political activism and union organizing, given close association of both with the communist party. The anti-communist hysteria that pervaded American culture at the time would have made it difficult for many readers to have sympathised with blacks, if some of them were communists and other communists were on their side.

On the whole, however, Bourke-White and her editors' decision to hide what they knew about black activism probably did themselves, their readers, and black South Africans a disservice. It compromised an analysis of South African society that was otherwise as moving as it was convincing. 'South Africa and Its Problem' created a flattened, one-dimensional representation of black communities by failing to reveal the cultural and political dynamism that was coming to define them. On a personal level, Bourke-White dishonoured the activists and organisers who must have taught her so much about South African society. She also sidestepped the challenge implicit in the portrait that she made of the two gold miners. Had she acknowledged the men as individuals, as well as symbols, she might have indicated to her viewers that they embodied far more than dignified suffering. In 1946, tens of thousands of miners just like them - and perhaps even they themselves - had gone out on strike, against all odds and in the face of massive state repression. The strike had failed, but it had surely been sign of things to come.

1 I am grateful for the many helpful comments that I received when presenting an earlier version of this paper to the South Eastern Regional Seminar in African Studies/South East Africanist Network and to the University of Virginia's Working Group on Racial Inequality. Anonymous readers for this journal also provided useful comments.

2 Letter, 14 April 1950, Margaret Bourke-White Papers, Special Collections Research Center, Syracuse University Library.

3 Letter, 15 April 1950, Margaret Bourke-White Papers, Special Collections Research Center, Syracuse University Library.

4 Vicki Goldberg, Margaret Bourke-White: A Biography (New York: Harper and Row, 1986), ix.

5 Alan Brinkley, The Publisher: Henry Luce and His American Century (New York: Vintage Books, 2010), 202.

6 Erika Doss, 'Introduction: Looking at Life: Rethinking America's Favorite Magazine, 1936-1972' in Erika Doss, ed., Looking at Life Magazine (Washington and London: Smithsonian, 2001), 2-3.

7 Brinkley, The Publisher.

8 Henry R. Luce, 'The American Century', Life, 17 February 1941, 61-65. Luce had created the magazine in the belief that people needed 'to see more in order to know more', as Marvin Heiferman points out. Marvin Heiferman, Photography Changes Everything (New York and Washington, D.C.: Aperture Foundation and Smithsonian Institution, 2012), 12.

9 'South Africa and Its Problem, Life, 18 September 1950, 111-126.

10 'South Africa Enshrines Pioneer Heroes', Life, 16 January 1950, 21-27.

11 Sources do not allow the exact date of her arrival in South Africa to be determined. It is unlikely to have been prior to early December 1949.

12 Albert Grundlingh, 'A Cultural Conundrum? Old Monuments and New Regimes: The Voortrekker Monument as Symbol of Afrikaner Power in a Postapartheid South Africa', Radical History Review, 81 (Fall 2001), 96.

13 Hermann Giliomee, The Afrikaners: Biography of a People (Charlottesville and Cape Town: University of Virginia Press and Tafelberg, 2003), 446.

14 Andrew Crampton, 'The Voortrekker Monument, the Birth of Apartheid, and Beyond', Political Geography, 20 (2001), 226, and Grundlingh, 'A Cultural Conundrum?', 95ff.

15 Crampton, 'The Voortrekker Monument, 224.

16 Erika Doss, 'Introduction', 7-8.

17 Theodore M. Brown, quoted in Goldberg, Bourke-White, 108.

18 On colonial and Afrikaner political mythologies, see Leonard Thompson, The Political Mythology of Apartheid (Yale University Press: New Haven and London, 1985), 144ff.

19 Goldberg, Bourke-White, 317-18.

20 The writer Erskine Caldwell, her collaborator on a number of projects and, for a time, her husband, once said that 'she was almost like a motion picture director' when she worked. (Goldberg, Bourke-White, 168.)

21 Chris Vials, 'The Popular Front in the American Century: Life Magazine, Margaret Bourke-White, and Consumer Realism, 1936-1941', American Periodicals, 16, 1 (2006), 86.

26 'Pioneer Heroes', 26.

27 Letter, 15 April 1950, Margaret Bourke-White Papers.

28 James Campbell, 'The Americanization of South Africa', Seminar paper, University of the Witwatersrand, Institute for Advanced Social Research, 19 October 1998, 3-4.

29 Campbell, 'Americanization', 22-23.

30 '"Lost in the Stars", Broadway Season's First Real Hit is a Musical Play Based on the Fine Novel, "Cry, the Beloved Country'", Life, 14 November 1949, 143-149.

31 'South Africa: These Things Happen', Time, 7 June 1948; 'South Africa: How to Advance Communism, Time, 6 December 1948.

32 'South Africa: It Has Always Produced Great Warriors', Life, 3 (May 1943), 79-89.

33 'Boer Farmer: South African Clings to His Forefather's Soil and Beliefs', Life, 16 December 1946, 97-101.

34 On the ideological contradictions within the magazines of the Luce empire, see Brinkley, The Publisher, xii.

35 Goldberg, Bourke-White, 154-58.

36 Margaret Bourke-White, Portrait of Myself (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1963), 311-327. [ Links ]

37 Giliomee, The Afrikaners, 491.

38 Bourke-White, Portrait, 314.

39 Letter, 14 April 1950, Margaret Bourke-White Papers.

40 Margaret Bourke-White's photographs, both published and unpublished, from southern Africa can be viewed on the websites of Getty Images and the Life photo archive that is hosted by Google. There is considerable overlap between the two archives, but each contains images that the other does not. In addition, I have examined photographs and contact sheets from southern Africa that are housed in the Margaret Bourke-White Papers, Special Collections Research Center, Syracuse University Library.

41 Goldberg, Bourke-White, 302.

42 'Country Doctor: His Endless Work Has Its Own Rewards', Life, 20 September 1948, 115-126.

43 As with most of Life's articles, the author of the text is not credited. In this case, in common with all longer photo-essays, the photographer does receive a by-line. The notes and memoranda that Bourke-White sent to her editors from South Africa influenced the text, but she did not write it.

44 Paul Gready, 'The Sophiatown Writers of the Fifties: The Unreal Reality of Their World', Journal of Southern African Studies, 16, 1 (March 1990), 139.

45 Goldberg, Bourke-White, 317.

46 Bourke-White, Portrait, 314.

47 On the process of making the photo, see Bourke-White, Portrait of Myself, 315-316; Bourke-White mentions her photographic assistant in Letter of 15 April 1950, Margaret Bourke-White Papers.

48 Patrick Lichfield, photographer to the British Royal Family in the second half of the twentieth century, is reputed to have made a similar remark: 'Remember that the person you are photographing is 50% of the portrait and you are the other 50%. You need the model as much as he or she needs you. If they don't want to help you, it will be a very dull picture'.

49 The two exposures vary most obviously in the men's facial expressions. The images can be found in the Margaret Bourke-White Papers, Special Collections Research Center, Syracuse University Library.

50 'South Africa and Its Problem', 111.

51 Gunnar Myrdal, with the assistance of Richard Sterner and Arnold Rose, An American Dilemma: The Negro Problem and Modern Democracy (New York: Harper and Brothers, 1944).

52 'The New South: Farms, Factories and Folkways Show Exciting Changes', Life, 31 October 1949, 79-90.

53 Booker T. Washington et al., The Negro Problem: A Series of Articles by Representative American Negroes of Today (New York: James Pott & Company, 1903).

54 D.D.T. Jabavu, The Black Problem: Papers and Addresses on Various Native Problems, (Lovedale: Lovedale Institution Press, c. 1920). A common South African variation was 'Native Problem. See, for instance, H.E. Rawson, 'The Native Problem, Journal of the Royal African Society, 11, 42 (Jan. 1912), 151-172, and Jan H. Hofmeyr, 'The Approach to the Native Problem, Journal of the Royal African Society, 36, 144 (July 1937), 270-297.

55 W.E.B. DuBois, The Souls of Black Folk (Chicago: A.C. McClurg & Co, 1903), 2.

56 Editors of Ebony, The White Problem in America (New York: Lancer Books, 1966).

57 Quoted in Ralph Ellison, Shadow and Act (Reprint: New York: Quality Paperback Book Club, 1994), 304. (Originally Random House, 1964.).

58 'South Africa and Its Problem, 112-13, 119-21, 124.

59 See discussions in, for instance, Wolfram Hartmann, Jeremy Silvester, and Patricia Hayes, eds., The Colonising Camera: Photographs in the Making of Namibian History (Cape Town and Athens, Ohio: University of Cape Town Press and Ohio University Press, 1999) and Erin Haney, Photography and Africa (London: Reaktion Books, 2010).

60 Christopher Joon-Hai Lee, 'The "Native" Undefined: Colonial Categories, Anglo-African Status and the Politics of Kinship in British Central Africa, 1929-38', Journal of African History, 46, 3 (2005), 463-64.

61 'South Africa and Its Problem, 115-16, 118-19. Despite the proud expression on her face, the woman seated at the machine cannot have been sewing with it. It appears to have been a foot-powered machine that is missing its treadle. In addition, there was no cloth under the machine's foot. If it had been an electric-powered machine, it still wouldn't have worked. There is no evidence of electricity in the courtyard.

62 'South Africa and Its Problem', 115-118.

63 'South Africa and Its Problem', 115.

64 Akim D. Reinhardt points out that Americans had discourse about 'the native' in regard to Native Americans. Like African natives, they were imagined to be exotic and ahistorical. See his 'Defining the Native: Local Print Media Coverage of the NMAI', American Indian Quarterly, 29, 3&4 (Summer-Autumn, 2005), 450.

65 'South Africa and Its Problem', 119-121, 124. On the Amalaita fights, see Philip Bonner, 'African Urbanisation on the Rand between the 1930s and 1960s: Its Social Character and Political Consequences', Journal of Southern African Studies, 21, 1(March 1995), 115-129.

66 'South Africa and Its Problem', 124.

67 'South Africa and Its Problem', 125.

68 'South Africa and Its Problem', 114, 124.

69 'South Africa and Its Problem, 113-14.

70 Ibid., 125.

71 Ibid., 126.

72 Ibid., 126.

73 'MBW and gold page two', Margaret Bourke-White Papers, Special Collections Research Center, Syracuse University Library.

74 Letter, 15 April 1950, Margaret Bourke-White Papers.

75 Bourke-White, Portrait of Myself, 324, 327.

76 Syracuse University's Special Collections Research Center holds many more.

77 Tom Lodge, Black Politics in South Africa since 1945 (London and New York: Longman, 1983), 33-34; A. Lerumo (Michael Alan Harmel), Fifty Fighting Years: The Communist Party of South Africa, 1921-1971 (London: Inkululeko Publications, 1971, 2nd rev. ed., 1980), 80-86.

78 This photography can be seen in both the Getty Images archive and the Life Google archive.

79 Iris Berger, Threads of Solidarity: Women in South African Industry, 1900-1980 (Bloomington and Indianapolis and London: Indiana University Press and James Curry, 1992), 190ff.

80 Wendy Kozol, 'Gazing at Race in the Pages of Life in Looking at Life, 160-62; Alan Brinkley, The Publisher, 234.

81 Doss, 'Introduction', 12.

82 Wendy Kozol, 'Gazing at Race', 173.

83 Robert E. Snyder, 'Margaret Bourke-White and the Communist Witch Hunt, Journal of American Studies, 19, 1 (April 1985), 6-16.

84 Brinkley, The Publisher, 358-61.