Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Kronos

On-line version ISSN 2309-9585

Print version ISSN 0259-0190

Kronos vol.38 n.1 Cape Town Jan. 2012

ARTICLES

Lounge photography and the politics of township interiors: the representation of the black South African home in the Ngilima photographic collection, East Rand, 1950s

Sophie Feyder

Doctoral student, History Department, Leiden University

ABSTRACT

This article attempts to historically contextualise and interpret a selection of photographs from the collection of South African ambulant photographer Ronald Ngilima and his son Torrance. Ngilima pioneered indoor portraiture in the Benoni townships of the early 1950s, thanks to his early acquisition of artificial lighting. As a consequence, his black, Coloured and Indian clients increasingly chose to be photographed at home, in particular within the space of their lounge (sitting room), or in Ngilima's lounge-studio. In these portraits, the subject poses amidst a lavish display of objects (tea cups, ashtray, gramophone...), furniture and homemade decorations (doilies, curtains, newspaper clippings...). Though the lounge portraits represent only a fraction of the entire Ngilima collection, I approach this subset of about 170 images as evidence as to how the residents of Wattville township appropriated the uniform sub-economic houses through long-term improvement schemes, contrasting with the apartheid State's deliberate efforts to frame them as temporary tenants. More broadly, these images invite us to think of photography's role in the construction of space and of self-representations in relation to space. What is the idea of a lounge? Why did it become such a popular photographic background? How did vernacular photography help to articulate abstract notions of selfhood (such as respectability or modernity) within historically specific circumstances?1

Despite the monotony of the physical layouts, each house had its own individual sensibility, its own colour and textures, its own smell. Home was a corner of the world that families owned, even if they were perpetual renters.

Shamil Jeppie, 'Interiors, District Six, c. 1950'.2

There is an interesting moment in South African vernacular photography when, in the early 1950s, the accessibility of evolving technology enabled street photographers to photograph people at home. Instead of the plain curtain thrown over a wall, clients could opt to have their own houses as the main backdrop for their portraits. Factory worker Ronald Ngilima and his son Torrance photographed for over ten years, taking portraits of individuals and groups from the various Coloured, Indian and black communities living around Benoni (East Rand), from the early 1950s to the mid-1960s. Ronald Ngilima was not the first black photographer in this neighbourhood, but the early possession of a flash and flood lamps enabled him to initiate indoor portraiture. Over several decades, the photographic negatives grew to eventually form an incredible visual archive of about 5600 images. This article is an attempt to historically interpret a section of the Ngilima collection, reflecting on the visual representations of the black South African domestic interior in Ngilima's work. It explores how black communities living around Benoni represented themselves in relation to their neighbourhood through the medium of photography. The Ngilima photographs invite us to think about the process of making a 'home', confronting us with the subjectivities and ambivalences that this notion contains.

The emergence of this new style of photography coincided with the accelerated development of modern townships that characterised the apartheid era. Ronald recorded the first few years of the State-planned township called Wattville, built just across from Benoni Old Location between 1946 and 1954. These new 'native sub-economic houses' were quite different from those of the Old Location: they offered modern infrastructure such as electricity and individual water taps, and new rooms such as a separate bathroom and a formal sitting room, locally referred to as 'the lounge. This lounge quickly became a popular place to take a picture: the couch, the doilies, the tea set, the coffee table, etc. were some of the essential elements that anchored the subject in a modern lifestyle. The lounge, incarnating domestic modernity and elegance, came to replace the Old Location stoep (veranda) as the prime photographic site to seek respectability and public display.

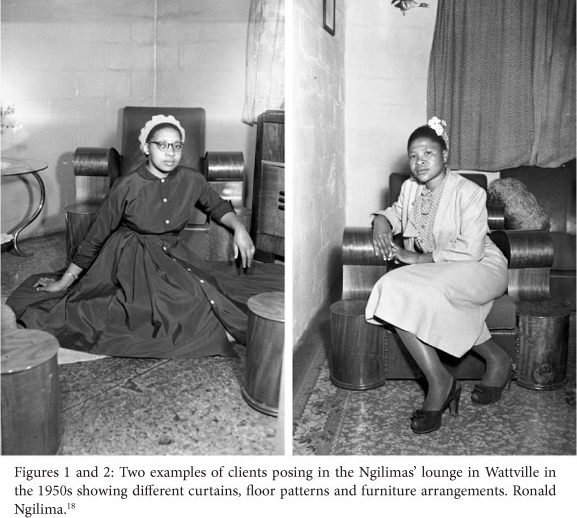

When trying to grasp the raison d'etre of these lounge portraits, one inevitably confronts the following questions. What makes a 'nice' background? How did the lounge become the favoured background for a portrait, in particular for women? What set of ideas or values became associated with the lounge, and what role did photography play in this process? Of particular interest are the series of photographs taken within the Ngilima's beautiful lounge, which was made available for shooting sessions. Clients could choose between posing against a plain curtain backdrop or using the space of Ngilima's lounge. This trend of mainly middle-aged women being framed in a domestic set-up that is not theirs further complicates the notion of 'home'. What is expected of a lounge? How did the lounge work differently from his standard flat backdrop? How was Ngilima able to transfer the qualities of his lounge onto his clients? To put it bluntly, how is it possible to visualise respectability?

The lounge photograph is not without its ambiguities. These Wattville lounge portraits omit the racial dynamics of the apartheid era: the fact that black people were denied ownership and that as tenants they had few opportunities to make substantial changes to their houses. The harsh implications of apartheid's policies in the domain of social housing, including the threat of eviction, are strikingly absent from these photographs. The new style of portraiture must be analysed within the social dynamics taking place in the area: the increasing conflict between site-holders and tenants in the Old Location, the quest to transform sterile houses into personalised homes in Wattville, the economic boom of the 1950s and an emerging consumerist culture. The shift in choice of photographic background, I argue, signifies a social adjustment to this new built environment of bare, uniform social houses. I suggest that a key to understanding lounge photography's popularity is the recognition of its capacity to reconfigure reality, to broach the unlikely ideal of becoming a homeowner.

'Unintentional' Documents: Photographic Archives and Everyday Life

For the visual historian, the Ngilima collection constitutes a unique source, very different from the textual sources found in institutional archives, or even from the images produced by contemporary black photo-journalists. While police reports and official municipal documents provide us with detailed information on black South Africans' living conditions (albeit from the skewed perspective of the State), few historical sources apart from private photographs are available to explore questions of subjectivity. How did black township communities cope with these harsh living conditions and with the stark social changes induced by urbanisation? How did they perceive themselves within the system of apartheid? What experiences led to the development of a distinct value-system in the townships, such as the emphasis on respectability? What did black urban South Africans aspire to?

Private collections of photographs are a crucial yet relatively untapped source of information for the historical study of everyday life, in particular of subjects at the margins of power structures whose own production of records (diaries, correspondence, posters, flyers, songs, etc.) would be unlikely to be preserved within traditional archives.3 Both 'everyday life' and vernacular photography are associated with similar connotations: informal, non-political, private, enmeshed with popular culture. Historians from the Alltagsgeschichte school, such as Alfred Ludtke, called for a closer study of people's behaviour, self-perceptions and actions on the modest scale of everyday life. Beyond the realm of 'small events' and of daily routines, everyday life can be defined as 'the domain in which people exercise a direct influence - through their behaviour - on their immediate circumstances'.4 Alltag historians consider the everyday as an experimental arena where people re-appropriate experiences and creatively translate them into forms of popular culture.

What do the twenty-six boxes of negatives from the Ngilima collection tell us about the Alltag of the mixed Benoni community? The Ngilima portraits are not just Ronald and Torrance's interpretation of their world but the result of a close collaboration with their clients. Satisfying their client's demands and his/her sense of aesthetic was the prime concern that guided the photographers in their work. Their photographic subjects requested to be depicted in association with what was closest to them - their living space, their relatives or friends, a particularly valued object. In this sense, the Ngilima collection can be considered as an inventory of the cherished moments, objects, places and peoples of a particular community at a particular time. Given the influence of the Ngilimas' clients over the process of image-making, these portraits are in effect records of how these people wanted to represent their lives in their own terms. The emergence of new photographic conventions and an evolving local aesthetic is further evidence of people's agency in a quickly changing environment, of their ability to respond to these changes through a medium of cultural expression that is directly under their control. Lingering in the background are also minute details that inadvertently survived the gaze of the photographer: a piece of tattered corrugated iron, unpolished shoes, bare walls, bottles of Castle beer. Such details anchor the portraits in the socio-economic world in which Ronald, Torrance and their clients were formulating their aspirations.

However, while photography captures a performance of reality, the extent to which it is a direct translation of everyday life is in dispute. Vernacular photography produces images that hover between fantasy and a latent reality, between individual authorship and collective representations. Ronald Ngilima's role as a portrait photographer was not so much to produce an accurate representation of reality as to intentionally embellish it so as to satisfy his client's fantasies. In other words, the Ngilima portraits are ambivalent documents of social imaginations. Furthermore, many aspects of everyday life are banished from the photographs. Death, labour, domestic chores, conflict, material deprivation were very much part of daily life in the Old Location yet one would not think so by looking at the pictures. These absences are themselves significant of the social role people attributed to photography.

Ngilima's photographs are in many ways 'unintentional' documents. The portraits were not taken with the purpose of objectively documenting a social and material reality, as in the tradition of photo-journalism. The Ngilima collection acquired the value of historical source through the weight of time passing and by gradually (re)-entering the public sphere of university archives.5 As with other historical sources, the historian contextualises the images according to their conditions of production and consumption. Similar to the exercise of writing a micro-history, historically reading a photograph requires 'a reconstructive linking together of the individual elements in a network of interrelations'.6

Taking photographs in the living room or dining room was by no means 'an African thing'. A close reading of private photographs from the Limburg immigrant mining community (Belgium) from the 1950s led Januarius to similar conclusions about the role of the dining room as a desired choice of photographic location.7 The strong similarities between the Ngilima lounge portraits and the Limburg dining room snapshots are evidence that the adoption of interior photography was part of a 1950s global trend. The present day popularity of parlour photography in Gambia indicates that this trend has continued in other parts of Africa up till this date.8 Within this global trend, the local context of production generated subtle photographic variations. The Limburg dining room photographs, for instance, put an emphasis on projecting strong family values, clearly illustrating the roles of each family member (the housewife, the male breadwinner). In contrast, the Ngilima lounge portraits focused on individuals or peer groups. Ngilimas' photographs were also more clearly staged, his subjects acknowledging and openly performing for the camera. Such subtle differences underline the need for researching local histories of photographic practices. Photography's interaction with the local social, political and cultural context inevitably creates different expectations of how an image should function and what role the camera should play.

Wattville, the 'Jewel of Benoni'

In 1951 the municipality of Benoni9 allocated to factory worker Ronald Majongwa Ngilima a four-roomed 'sub-economic' house located in the recently created township called Wattville. As a respectable married man with five children who had worked for several years at Dinglers Tobacco factory, Ronald Ngilima had managed to fulfil all the necessary conditions to obtain one of the 1200 recently built houses available. The Ngilima family was lucky: the waiting list for these houses was prohibitively long, not just because new accommodation in the area was so scarce compared to the growing needs of the black community, but also because these houses were supposedly a major improvement compared to the rickety, self-built, iron-and-wood constructions from the adjacent Old Location. Wattville in contrast had it all: tarred roads, large yards in a neatly set out area, 'excellent facilities' in each brick house such as a supplied coal stove, electricity and individual taps. Every house had a modern room layout where every room had a specified function, including a separate 'fully equipped' bathroom and a lounge/living room.10 In the Old Location, one had to share communal taps as well as the toilets that were still functioning under the disposable bucket system. Only the wealthiest households could afford to get electricity.

Wattville was designed to be 'the Jewel of Benoni', the 'most modern township', 'unequalled', the 'envy of the entire Reef'.11 Wattville houses were supposedly so sophisticated that many Wattville inhabitants think up to this day that they were initially meant for Coloureds, not for Blacks. Rather than a sudden change of heart, the Benoni municipality was trying to resolve the dragging and messy problem of the Old Location and its 'overflowing' black population. Already in 1934, a series of reports came out in the media denouncing the terrible living conditions in the Asiatic Bazaar and its lack of infrastructure.12 Set up in 1911, the Asiatic Bazaar quickly had grown to include a Native and a Coloured section and by the mid-1940s, these three sections known as the Old Location (or 'Etwatwa') could barely absorb the growing inflow of new migrants with most stands already packed with shacks in the backyard, and entire families squashed into each. In 1946 the local administration was faced with yet another embarrassing crisis, provoked by a massive squatter movement initiated by Harry Mabuya who encouraged families to occupy the 123 empty, unallocated sub-economic houses built in 1940 (known as Rooikamp, the oldest section of Wattville). He also established an autonomously run and self-sufficient Tent Town to deal with the shortage of housing.13 The accelerated expansion of Wattville in 1948 was initially meant to relieve the incredibly overcrowded Asiatic Bazaar of its black inhabitants and solve the squatting crisis. The difficult conditions for application14 meant that Wattville mainly attracted a certain established working class from the adjacent 'Native Location', in particular young married couples and families renting backrooms: like the Ngilimas. The acute shortage in housing had heightened the antagonism between site holders, who were continuously pushing up the rent, and their vulnerable tenants. It is no surprise that, as Thembi Mateta recalls, 'my mother danced with joy when they gave her the keys to our house in Wattville'.15

In 1962 the Bureau of Market Research16 led a major economic survey on the Benoni townships. The report noted that Wattville was an older township than Pretoria or Daveyton with a more urbanised population, numbering 18495 people. It also had a slightly different occupational structure. Wattville had a higher percentage of semi-skilled workers and a higher percentage of earners per household. Its percentage of people with teacher's or similar diplomas was higher than that of the Pretoria townships. Furthermore, Wattville had a higher percentage of female household heads than other black townships on the Reef. Interestingly, 30% of female earners in Wattville were earning R30 or more, compared to only 16% in Pretoria. The report concluded that Wattville households had relatively more money at their disposal for 'optional' spending than those of other black urban areas.

Creating a Niche Market

For Ronald Ngilima, Wattville represented new prospects for his photography business. Born in the Eastern Cape in 1910, Ronald moved to Johannesburg (now Gauteng) as a sixteen year-old, joining his elder brother at the mine compound. I still do not know how Ronald became a photographer, but oral evidence indicates that he started photographing as early as the mid-1930s, when he was in his mid-twenties and still living in Modder B. He would continue to do so until his death in 1960.

The earliest negatives in the collection date from the early 1950s, suggesting that he first started with a box camera (then known as a 'While-you-wait' camera) that did not generate negatives.17 Having lived in several different locations, Ronald managed over the years to build a vast network of clients across the Benoni municipal grounds and across the racial divide. In the Old Location in particular, Ronald was very popular amongst Indian and Coloured families. Unlike some of his local competitors, he managed to progressively upgrade his photographic equipment and skills, and was thus able to anticipate or adapt to the shifts in the demands in popular photography. At least as early as 1951 he began working with a foldable camera that used middle-format 5.5 x 9 mm film. He later acquired a flash and a couple of flood lamps. The new mobility that such a compact camera gave him, combined with this additional source of light, enabled him to bring portraiture indoors. Perhaps under the pressure, with new studios emerging in the Old Location, Ronald set up an informal studio in his house, consisting of a long curtain and various props: a gueridon, a basket full of flowers, doilies, a framed portrait.

After some time, he offered an additional option by making his whole lounge accessible to his clients as some kind of extended, 'three-dimensional' studio. Clients were given the choice as to how to arrange the various elements in the lounge. In order to maintain the lounge's appeal and to give it an air of novelty, the Ngilimas were constantly changing the curtains, wallpaper and carpet, and the orientation of the furniture (see Figures 1 and 2). Ronald also started taking portraits of people sitting inside their own homes. Until then, indoor photography was confined to posh white-owned professional studios in town. Now, for the first time, clients could be photographed in the environment of their own homes, or a similar substitute. I would argue that indoor portraiture gave Ronald an advantage over his colleagues, enabling him to construct a niche market of clients who wanted to be photographed at home. In other words, the environment of the township had become 'photographable',19 an acceptable background for a dignified portrait.

Most people simply hired Ronald's services on the spur of the moment, as he was cycling past their house on one of his regular tours. Others came to his studio more thoroughly prepared with a very good notion of what photograph they wanted. Christmas time was a busy period where people would come to be photographed in their new clothes. Even the most spontaneous shooting sessions involved some level of decision-making: what background, whom to include in the picture, what pose, etc. Studying the Ngilima collection as a whole, one is confronted with a cross between a large diversity of outcomes and clear patterns in the photographer's work. Married couples, for instance, were often photographed sitting side by side, hugged by a horizontal frame, following the conventions of the traditional airbrushed portraits.20 Young men seemed to prefer Ronald's curtain backdrop and within this set-up came up with the most innovative and diverse range of poses. While Ronald would readily provide his clients with advice and guidance, he was also open to their ideas. Hence the collection includes surprising photographs, like those depicting scenes of staged violence (young men pretending to stone or stab each other), or those in which women in bras and underwear hold alluring poses. The diverse demographic of Ronald's clients meant that his subjects were seeking to project different things in the construction oftheir self-image: motherhood, gangsterism, respectability, cutting-edge fashion, piousness, sexiness, bodybuilding aesthetics, modern love, family life, etc.

Unlike many ambulant photographers who relied on professional photo labs, Ngilima had somehow acquired darkroom skills and an enlarger. Towards the mid-1950s, he installed a darkroom in his bathroom. During my fieldwork I was able to dig up several original prints kept in various private households in Benoni. Most of them are only of modest size, barely larger than the actual negative. A self-portrait taken in his darkroom displays larger-sized envelopes of photographic paper which suggest that he was able to make larger-sized prints. According to his daughter Do-reen, he was also occasionally commissioned to make a wooden frame for an enlarged picture. The family portrait that still hangs in their living room bears witness to these skills. Most of his clients, however, preferred the smallest size, small enough to insert in a wallet or a purse, facilitating the circulation of the image amongst networks of friends, lovers and family members.

After Ronald died abruptly in Wattville in 1960,21 his son Torrance took over the business for a few years, expanding it to include parties, beauty pageants and other social events. Born in 1940, Torrance was part of that generation of black people who were born and raised in the townships. His young age meant that he was able to capture something of the black urban youth culture from the 1960s that he himself participated in. Hence his style was different from his father's, more inspired by the photojournalism from the magazines that he grew up with.

Out of the 5600 images in the collection about 170 photographs depict people posing in their lounge or in the Ngilimas' lounge-studio. Although they represent only a fraction of the collection, the numbers are significant enough to consider it as the expression of a social phenomenon. My initial fieldwork has allowed me to establish that a large majority of indoor portraits were taken in Wattville.22 Furthermore, most indoor portraits were taken in the lounge, with only a minority taken in the hallway, bedroom or kitchen.23 It is clear that the rise of indoor photography in Wattville is linked to Ronald's acquisition of the flash and his own moving into the place in 1952. But that alone does not explain why so few Old Location inhabitants benefitted from his flash and asked to be photographed inside their homes. They continued to be photographed on the stoep (veranda) or against a corrugated iron sidewall, despite the availability of the technology.

I argue that the link between the emergence of indoor portraiture in the early 1950s and the accelerated development of townships like Wattville goes beyond a mere chronological coincidence. Spigel suggests that there was a connection between the rise of mass-produced suburbia and the rise of television in post-war United States, both spaces mutually reinforcing each other as social practices and cultural fantasies. 'Media and suburbs are sites where meanings are produced and created; they are spaces (whether material and electronic) in which people make sense of their social relationships to each other, their communities, their nation and the world at large'.24 In the case of the Ngilima indoor portraits, the experience of a new built environment (social housing) clearly had an impact on the local practice of photography (media). But unlike television, popular photography was a medium that Wattville inhabitants controlled and fashioned to their taste. I argue that lounge photography would not just be an expression of Wattville residents' attempts to make sense of their new surroundings and to make it their own, but also part and parcel of this very process.

Expressing Social Distinctions

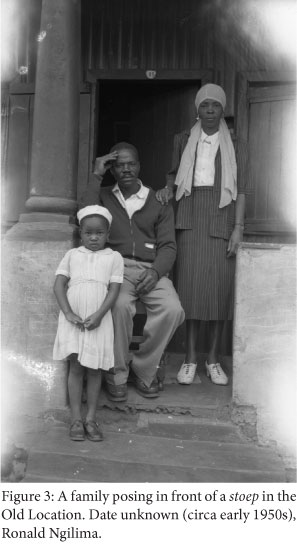

In Appadurai's words, the backdrop contains important clues that help us 'place' the photograph in its geographical and historical context.25 As mentioned above, most of Ronald's clients chose their background quite consciously, selecting one that would show them off in the most positive way. Comparing Ngilima's photos taken in Wat-tville to his photographs taken in the Old Location enables us to understand how spatial and photographic practices mutually influenced one another. The significance of the choice in backdrops emerges when considering the meanings attributed to various sites, meanings that are the product of a history of architecture, of people appropriating their living spaces, and of local housing politics. In the Old Location, for instance, most of the houses were privately built.26 Having a stoep suggested one had the economic means to invest in this additional structure, giving the impression of being a site holder. The division between site holders and tenants was one of the strongest factors of social distinction within the black community of Etwatwa, where differences in revenue were generally minimal.27

Figure 3 depicts three subjects, probably parents and their child, standing next to the column of their stoep. Their clothing indicates a certain level of prosperity: the little girl is wearing her 'Sunday best, a matching beret and shoes; the woman is wearing a two-piece suit and accessories such as a watch and some jewellery. The doek covering her hair and her left hand resting on her husband's shoulder suggest that she is a married woman. The column implies long-term investment and stability, as well as a certain economic well-being. The address number appearing above the door also indicates that they are properly registered with the local authorities and have the appropriate permits to live in the urban area. The combination of clothing and material environment hence gives the impression that this is a well-established, law-abiding and respectable urban family. Unfortunately, this family has not yet been identified and it is impossible to state whether they really stayed there and whether they were owners or simply tenants. According to Joyce Mhlanga Ndlazilwane, people would often choose a particularly beautiful house with a nice stoep or front gate simply to have a pleasing background for their picture.28 Through the services of a photographer and the magic of framing, subjects could potentially transcend the site holder/ tenant divide.

In Wattville, people found alternative ways to express social distinction. Unlike the Old Location where differences in wealth translated in an array of various housing conditions, the progressive expansion of Wattville produced rows and rows of identical houses. As the municipality initially refused to sell the council houses, all the inhabitants were reduced to the status of temporary tenants. In Crankshaw's terms, 'housing provision by the State had produced a homogenised urban landscape where workers and the middle class lived in identical houses'.29 Getting a council house came with a long set of rules and regulations, one of them stating that tenants were not allowed to alter the original foundations of the house, nor to make any ex- tensions. Only marginal improvements could be made, for instance putting down a layer of cement on one side of the house or building steps leading towards the front door. Building a fancy entrance wall or an elaborate stoep was not allowed, though applying polish on the windowsills was. As a consequence, members of the household could only really make domestic improvements or alterations to the garden and the inside of the house, usually to the new lounge.

The lounge called for an entirely new range of furniture and objects, in particular couches and armchairs, explicitly conceived for the sitting area. As Leslie J. Bank writes of the domestic interiors of the black township Duncan Village, built near East London in the 1940s, 'The dark-wood dressers, tables and cabinets that had been popular in the old location were cleared out to make way for a flood of new products now on the market that were specifically designed for small houses.'30 According to Mia Brandel-Syrier, writing about the emergent black middle class in Johannesburg townships of the 1960s, this accumulation of objects stemmed from the rapid expansion of new housing estates. 'Houses needed curtains and carpets, dining-room suites and kitchen schemes; new tea sets required doilies and display cabinets required "objects d'art"; house-proud hostesses needed tea and polishes; generous hosts needed cigarettes, and children's parties sweets and cold drinks.'31

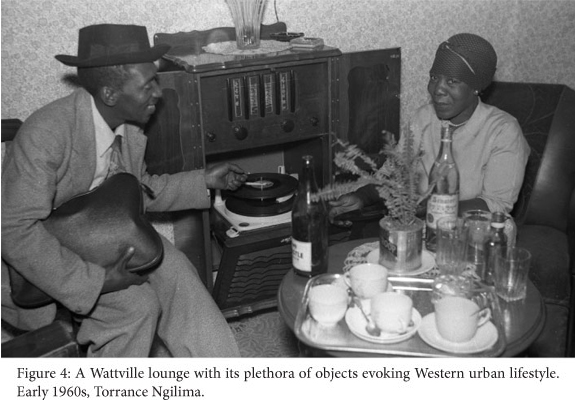

This enthusiasm to furnish the sitting area also coincided with the post-war economic boom, in which black households were suddenly flooded with a range of new products and commodities, in particular beauty creams and cosmetics.32 It contributed to the feeling that whilst the suburban dream was still reserved for a white elite, black people could also get a share of the profits of the economic boom.33 In Figure 4, for instance, a man and a woman are depicted sitting comfortably on either side of the gramophone or radio set that occupies the central part of the portrait. The woman sits in an armchair, holding a record and smiling at the camera. The man is holding a pouch in one arm and pretending to put on a record with the other hand. On the coffee table, one sees teacups, saucers, spoons, a sugar bowl, a tray, glasses, open bottles of alcohol, a plant in an improvised vase on a saucer, doilies and ashtrays. There is a cable poking out from behind the gramophone, a sign that the house had electricity. Cables and plugs were often included in the picture instead of being hidden away. Wattvillers were proud of the fact that they had electricity in their houses. As one interviewee put it, 'at night Wattville was shining while the Old Location remained plunged in the dark'.34

Representing Lifestyles

In comparison, the Old Location's dense population and the general lack of space meant that the rooms were necessarily multi-purpose: eating meals, taking baths, studying, children sleeping, etc. all had to take place in the same room. Amongst the tenants staying in the backrooms in particular, few could afford the luxury of having a whole room solely dedicated to receiving guests.35 For contemporary readers of the Ngilima photographs, the stoep and front door shots evoke the type of street life that characterised places like the Old Location. According to Leslie Bank's study of an East London location in the 1950s, the stoep was an intermediate space between the private and the public that enabled women to complete their domestic chores while keeping an eye on the children and on the street life.36 It was a way of asserting one's presence in the public domain, with the possibility of calling out to each other and catching up on the gossip. It would also be the space where music bands could rehearse, or where the young ones could dance to the gramophone.37 In short, the stoep played a central role in organising social interaction within the vibrant location.

It is doubtful that Old Location residents chose external facades as backdrops because they wanted to emphasise this aspect of their lives. The comparison is useful, however, to pinpoint the changes in social dynamics that the new township implied. For the sake of reducing building costs, state architects did not include a stoep in their plans for Wattville houses. Instead, they provided each house with an individual tap, bathroom and lounge. This new division of space and individualisation of services meant that women could stay indoors to do their chores. Another rule in Wat-tville was that inhabitants were not allowed to erect shacks in their backyard. Hence the kind of communal life that took place in the courtyards of the location evolved towards a household economy based on the model of the nuclear family.38 The vision behind the new architecture of the modern township was to develop 'new Non-European men' and to impose a more individualistic way of life that would eventually substitute the tribal unit with the family as the basic cultural unit.39

The photographed lounge seems to sum up the social changes that accompanied the introduction of social housing and to embody this drive for an individualistic lifestyle. According to Appadurai, the studio backdrop, no matter how realistic it strives to be, is only a representation of an actual site. Because the backdrop is fragmentary, it is inevitably metaphoric, alluding not to a particular location but to a type of location, loaded with cultural references and icons.40 Though the lounges in the Ngilima photographs are 'real' insofar that they refer to actual existing locations, I also read them as the expression of the desire to engage with modernity and embrace this 'new age' of mass consumption. The lounge contained a plethora of domestic items that were meant to define the essence of urban lifestyle, in particular tokens of modern technology. The radio, the gramophone, the radiogram and the vinyl record were amongst the most popular props to pose with for both young and old.

Visualising one's enthusiasm for such objects and fashion 'from overseas' affirmed one's dedication to cosmopolitanism, a claim the National Party government and many white South Africans were reluctant to acknowledge. In their eyes, Africans' exposure to city life and the consequential distancing from traditional values were responsible for their moral collapse and fall into criminality (alcoholism, prostitution, gambling, gangsterism). The first issues of The African Drum,41 reporting on 'African' tribal life and 'African' traditional customs, are representative of a larger enterprise by a patronising white class to retribalise African identities.42 To deny the emergence of black urban culture was to underline the temporary nature of the African presence in urban space and their inevitable return to the homelands. While rejecting this imposed association with tribalism and rural identity, black South Africans' engagements with modernity were constructed not just in opposition to tradition, but also in their own positive terms, in their embracing of consumption and a new material culture, in this disposition to be 'enchanted by the production and circulation of novelty, innovation and new fashions' and in their 'enjoyment of and attachment to new things.43

The Lounge as 'a Sensual Space'

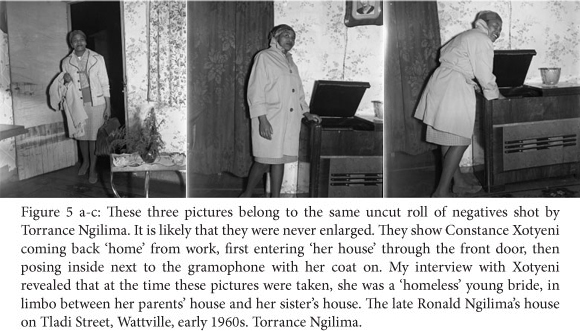

In his analysis of 'parlour photography' in Gambia, Buckley argues that the concept of the parlour is not fixed to a single room. The parlour (the Gambian term for sitting-room) has a 'transferrable disposition' that can be applied to other rooms in the house, including the bedroom, so long as they display a similarly luxurious use of the space. A similar 'transferrable disposition' can be found in the short series of photographs taken in Ngilima's lounge-studio. The series of pictures 5a-c depicts Constance Xotyeni, the Ngilima's next-door neighbour, pretending to be coming back 'home' from work and relaxing to some music in 'her' house. Through the magic of photography, the aura of the lounge holds even without the photographic subject owning such a space. In other words, the lounge-studio is no more 'real' than a painted backdrop, yet it has more of an effect on the viewer. What makes the idea of the lounge so visually convincing?

In his text on popular photography, Appadurai considers only the iconic qualities of the flat surface behind the subject that function as backdrop. But the Ngilimas' lounge-studio worked differently from his curtain-backdrop and attracted different kind of clients (mostly middle-aged women). I wish to argue that the convincing effect of the lounge lay in the representation of a three-dimensional, all-enclosing space - as opposed to a flat surface.44 The effectiveness of the idea of the lounge partly stems from the person's ability to inhabit this space and invest meaning in it through a set of practices. According to a typical Western division of space, the lounge is the only room in the house exclusively reserved for non-economic activities, such as listening to music or receiving special guests. Many Wattville households were admittedly so full that they had to use the lounge as a second bedroom. But in the morning, the children would store away their bedding and the room would recover the aura of the lounge again, now being 'used' for special occasions.

For some of the Ngilimas' subjects it was not enough to simply pose with objects of modernity. Many of them also wanted to demonstrate their familiarity with such technology by actually interacting with these objects, for instance by twisting the radio's knob, pretending to put on a record, or to read a magazine. For Buckley the parlour is best understood 'as a sensual space, where persons participate in specific sensory relations with the material environment. The experience of being photographed in the parlour 'made the link between the visual and the other sensory registers, including the embodied emotion of elegance'.45

The sensory experience of the lounge had a particular resonance amongst women as it became entangled with the practice of hosting and the notion of respectability. Respectability can be defined in many ways: an unconditional respect towards law and order, being very religious and heavily involved in church life, being economically successful, or being highly educated.46 But respectability for many women was also about the art of receiving visitors, the art of making one's house look presentable, about conforming to certain etiquettes of hospitality. As the most public room of the house, the lounge is in its essence geared towards the reception of guests. The accumulation of furniture, decorative and technological objects in the lounge, is part of the process of making the room appealing to an external audience. To properly serve a single cup of tea requires: a teacup and saucer, a teapot, a sugar bowl, a milk jar, a separate plate for the scones, a tray, doilies for the tray, as well as storage devices for all these objects. The visit of special friends or relatives coming from far away was a popular opportunity for calling a photographer to record this event. The elegant surroundings and the posing for the camera generated in turn 'the experience of comportment and the sense of being well composed'.47 Hence many of these lounge portraits are a mise-en-scene of hosting rituals: female subjects pretending to pour a cup of tea, holding a tray of glasses, or sipping on a cup while holding the saucer with the other hand (Figure 6).

Such hosting etiquettes and rituals are not specific to Wattville and have certainly been practiced for many generations in the Old Location. The new council houses, however, anchored respectability and hosting in a specific material culture that revolved around the lounge. Ronald's shooting sessions created a sensual experience that participated in the configuration of the lounge as the main site for visualising respectability. The new tradition of lounge photography magnified the public quality of the lounge by bringing it under the scrutiny of the camera's ruthless gaze. To be 'photographable' or 'showable' was a mark of approval. It was evidence that the room had reached the aesthetic standards of presentation to become a photographic backdrop. These photographs would then be put in albums that would be taken out and shown to visitors. 'As an arena for display, the parlour serves as both a room to show photographs and a room in which to pose for photographs.'48 This combined acts of producing and consuming images in the same site, enhancing the notion that the lounge was a stage where people could play out their aspirations of a modern lifestyle.

Besides the practices and sensorial experiences that configured the space of the lounge, the aura of the lounge also stemmed from representations within the broader visual economy. Ngilima's photographs are visually close to the types of images of domesticity that were being circulated in mainstream magazines, including ones oriented towards a black readership. For instance, Drum articles reporting on rich and prominent black people in South Africa would typically be accompanied by a portrait of the person in question situated in richly decorated and furnished living rooms. Every issue was full of advertisements for furniture shops and kitchen sets, floor polish and gramophones. For Dorothy Driver, Drum publicised these domestic commodities with the aim of constructing consumer desires and forging an ideology of domesticity through an aggressive demarcation of separate gender spheres. Driver argues that the ideal of the housewife that Drum projected was in complete denial of the economic conditions of apartheid that drove most women to work.49 Indeed, out of the twenty-five women I have interviewed so far in Wattville, only two of them had never worked outside of the house. As stated previously, Wattville seemed to have had a particularly high proportion of working women, including a high proportion of women earning relatively high salaries (R30 per month in the 1950s). Most of my female interviewees had worked at some stage in the textile factories in Doornfon-tein, Johannesburg. A fifth of my female interviewees were teachers or nurses.

Though Driver's critical analysis of Drum magazine is very perceptive, she fails to take into consideration how women actually received these Drum images and experienced domesticity in their own lives. From Driver's feminist perspective, it would perhaps seem paradoxical that economically active women would focus much of their aspirations on domestic interiors, that is, that they would conform to this patriarchal ideology aimed at 'keeping women in their place', i.e. at home. The indoor Ngilima portraits convey a very different message as to how women creatively constructed their self-image in relation to the interior space of their home.

Domesticity as Hard Work

Belinda Bozzoli and Mmantho Nkotsoe's Women of Phokeng is a thorough historical study based on extensive interviews with twenty-two women, who represented the first generation of Tswana women to migrate to the city for work.50 The extent to which the purchase of furniture played a role in their decision to work in the city is striking. According to one of the interviewees, Naomi Setshedi,

There was a sense of freedom about staying on your own in Johannesburg, and things like furniture we had seen others bring as fruits of their work in the towns urged us to follow suit ... It was the in thing in those days, and when you perhaps visited a friend in the village who had worked in the towns, you'd find her room stocked with all the furniture and that was all the incentive you needed as encouragement to find a job.51

'Posting' home (back to Phokeng) some furniture was a source of pride and evidence of their agency as hard workers. The twenty-five female elders that I interviewed in Wattville represent a slightly younger generation, for the most part born and bred in an urban setting. Many were born in the Old Location, to parents who could already afford some furniture, at least the kitchen set and the dining table. They then moved to Wattville, either following their parents, or as young brides setting up their own homes. In both cases, there was quite some excitement about moving into houses with such modern facilities. According to Bank, black women from East London townships in the 1960s had been 'nourished on images of the modern housewife in the media for more than a decade'.52 The new council houses provided the opportunity to create modern interiors that matched the glamorous images from magazines such as Drum and Zonk!. Yet the process of settling into these new houses and 'making a home' was far from being as easy as advertisements suggested.

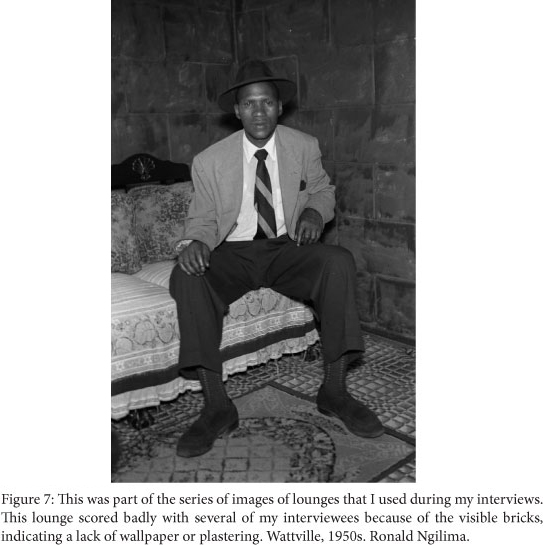

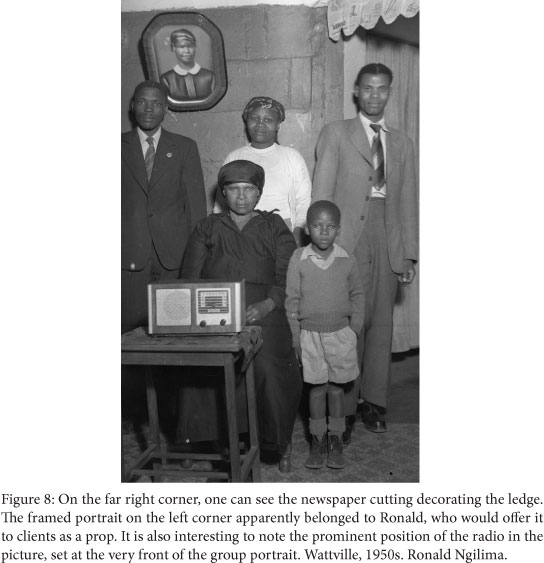

Details of this process came out clearly from the interviews I conducted in Wattville. Part of the discussion was structured around a series of twenty lounge portraits, focusing on the question of what made a nice lounge. When discussing Figure 8, Rose Mhlanga gave a rather negative judgement of what I had initially taken for a rather nice lounge. She brought my attention to elements such as unplastered walls and mid-length curtains (only covering the window instead of falling to the floor), curtains that were simply hanging on a string instead of having a proper pelmet.53 Through such detailed remarks, I came to realise quite the extent to which these lounges were the result of personal investment with appropriate attention given to the smallest of details.

Their domestic enterprise is all the more remarkable when considering the initial state the houses were in. All of my interviewees underlined the bareness of Wattville houses when they first moved in. In an attempt to keep construction costs as low as possible, the construction company left all finishing touches to the future tenants. These included putting in a ceiling, cementing the floors, putting doors into the rooms, plastering the bare walls, etc. Such improvements were too costly to be done in one go and were addressed progressively. Doors, for instance, were quite expensive: photographs taken in the hallway leading towards the bedrooms depict hung curtains used as a temporary substitute. Some decorations could be done cheaply, for instance by cutting out newspapers in various shapes and patterns so as to decorate the ledge figuring above the hallway. Old newspapers were also used to make Christmas garlands or as a cheaper substitute for wallpaper. Bare brick walls would be partly covered by free picture calendars bearing the name of local shops. Advertisements displaying pin-up girls and framed religious pictures were another popular form of decoration. Framed photographs covered the walls of the lounge, firmly anchoring the impersonal house within the personal narrative of family history. Wedding pictures in particular added an aura of formality and stability to the room, as if to resist against the inherent instability that characterised the lives of so many black families. Displaying photographs was so important that Ronald would go around on his trade tours with some of his own frames, offering them to clients who did not own any (Figure 8).

To what extent was the lounge a feminised space? It seems as if men more than women favoured the front door, or the house gate as a backdrop for their portrait. This is perhaps an attempt to portray oneself as the male provider, the guardian of the house, or to distinguish themselves from the space of domestic interiors, loaded with notions of femininity. This said, there were almost as many men as women posing in their own lounges. I did, however, notice that it was only women who posed in Ronald's lounge-studio, while young men generally preferred to pose against the backdrop curtain. Improving the lounge was not exclusively a feminine activity. Unlike the Tswana women from Phokeng, most Wattville women expected their husbands to purchase the larger pieces of furniture. But if the husband would buy the glass cabinet, the wife would use her salary to buy smaller things like crockery and tea sets, objects that further personalised the room and actually made use of the glass cabinet. Often the husband gave his salary to his wife for savings, in which case the wife would partake in the decision-making process. The lounge was not exclusively feminine. It was, nevertheless, a space for which women would make plans, save, imagine and slowly work towards the completion of these plans.

De Certeau's notion of 'tactics' is useful to understand the importance of these domestic activities. Institutions such as the municipality have the power and the resources to execute certain strategies that have a big impact on people's lives (for instance the removal of 'black spots'). The 'weak' resort to cunning tricks carried out in everyday life in order to navigate as best they can the systems that they infiltrate. De Certeau compares ordinary consumers to snowy waves of the sea that 'drift over an imposed terrain, ... slipping in among the rocks and defiles of an established order'.54 In this light, consumption ceases to be a passive activity. The consumer is an 'unrecognised producer', operating within the space organised by the colonizer/occupier but in an autonomous way. Women in Wattville were perhaps unable to challenge or disobey the numerous regulations regarding the municipal houses. State architects designed the sub-economic house so as to include a sitting room. Many women complied with the design but with convictions and objectives that were foreign to the architects' intentions. Small manoeuvres such as decorating, furniture shopping, and general homemaking enabled them to assert their own personalities and sense of self-worth. The insertion of their own goals and desires into this imposed situation is what De Certeau calls 'an art of manipulating and enjoying'.

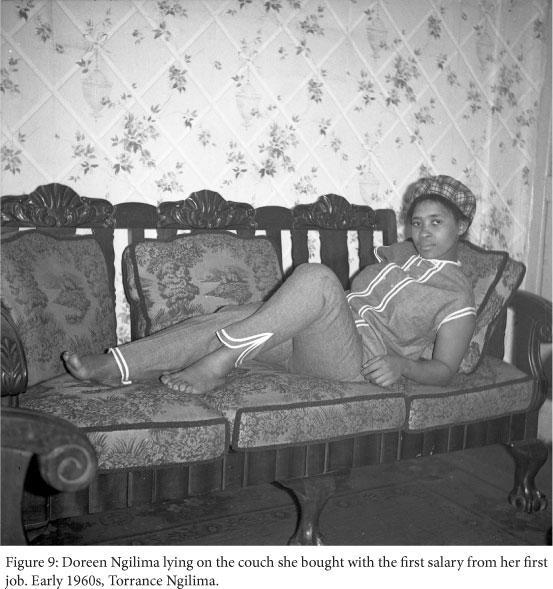

Figure 9 is a rather sexy portrait of Doreen Ngilima, Ronald's second daughter. This portrait was taken after he died and she had started working to sustain the rest of the family. The couch on which she is lying was bought with the first salary of her first job and is still in the house up to this day. Rather than projecting submissiveness or obedience, this portrait oozes with the self-assertion and pride of a woman not just able to maintain herself but also to improve the family house.

Creating Permanence

These strategies of home improvement are all the more remarkable, given that they took place long before Wattville families got extended leases and title deeds for their properties. The Benoni municipality initially refused to grant ownership over council houses, as another way of reminding Blacks that their presence in town was temporary and conditional on their ability to find work.55 In 1954 the Non-European Affairs Committee of Benoni approved the introduction of such a scheme only after an official report proved that 'granting temporary leasehold rights to blacks did not provide any permanent form of tenure and was thus not contradictory to the policy of separate development'.56 In other words, thirty-year lease plans did not alter the fact that families could easily be evicted, for being late on payment or for losing one's job and hence losing the right to reside in an urban area. Women were particularly vulnerable to evictions in cases where their husbands had died and had left them as widows without any sons. As Nomathemba Ngilima stressed,

Those days were terrible. If you didn't pay rent on time, within a week they were coming to kick you out. Every month, we saw families being publicly humiliated with their belongings piled in the street. We lived in fear of eviction.57

It was only in the mid-1980s that families were given 99-year leases and only after 1994 did they become full owners of their houses. The lounge photographs thus seem to completely omit the racist dimension of living in apartheid South Africa in the 1950s.58 As the first black township built in Benoni, Wattville was under the tight surveillance and control of the local municipality. Inspectors would come around to make sure residents would maintain their houses 'properly' and not build any extensions.

There is an interesting gap between what these photographs seem to suggest and the political background against which these photographs were being made. As stated before, the Ngilimas' lounge photographs resonated with the images found in lifestyle magazines. These magazines were themselves influenced by North American visual culture, which in the post-war context of the suburbia explosion were generating images idealising the identity of the middle-class homeowner.59 The Ngilima lounge portraits are a local re-appropriation of this homeowner ideology in defiance of the prevailing racist housing laws and the constant threat of eviction. When asked how the regulations made her feel about her house, Lili Mkhulisi replied with a wave of her hand and a big smile: 'Ah never mind [the rules], it was still my house!'60 I would argue that the impulse to upgrade the house was perhaps an essential way to cope with this constant threat of eviction and create a sense of permanence. Similarly, Ginsburg interpreted the improvement schemes in Sowetan houses in the 1960s and 1970s as a way for black families to collectively create a sense of permanence. 'Housing activity served to reinforce one's claim to urban residence where other forces conspired to deny it.'61 Given the indignities and insults that black people regularly experienced, adds Ginsburg, the upgraded home was like a shelter from the harshness of the apartheid environment, where residents could reconstruct a sense of self-worth and dignity through these long-term investment plans.

Conclusion: The Richness of Township Life

In present day Wattville, the Ngilima original prints are found wrapped in a blue plastic bag and buried in the bottom of a cupboard. Ronald did not produce fancy photographs for posterity, the kind that would be blown up and put in elaborate golden frames. His generation of ambulant photographers celebrated the individuals themselves without discriminating against the person on the grounds of social status or the importance of the photographic moment. The Ngilima collection is a significant indication of how photography became part of daily life in the township and how it slowly slipped from being a highly ritualised and official moment into the realm of leisure, spontaneity and fun. Photographers like Ronald and Torrance Ngilima enabled photography to reach deeper into the sphere of private life, recording the more banal things that make up daily life. Their portrayal of the everyday depicts both Wattville residents' keenness to embrace cultural and social changes (consumption) and their struggles to create a sense of permanence in their lives (home ownership, family narratives).

Read within the socio-historical context of their production, the Ngilima photographs enable us to explore some of the more subtle and complex aspects of a particular community at a particular time. For many women who experienced both the Old Location and Wattville, the move to the modern township in the early 1950s brimmed with promises of a modern lifestyle, opportunities to become an urban consumer. Yet to accept the comforts of urban living was also to accept becoming a tenant, to be subjected to increasing surveillance by the State, with the permanent threat of eviction and the loss of landlord status. This article has tried to analyse the impact of the new township architecture on social dynamics and consciousness, making the link between a local practice of photography, selfhood and architecture.

The experience of photography demanded a conscious choice of background, props and presentation of the self, resulting in a set of expectations regarding what a 'nice' background should look like. Ngilima's clients contributed to the making of a collective understanding of respectability, which became anchored in the sensual environment of the lounge. While reinforcing an ideology of social distinction, photography also provided opportunities for transcending them. The magic of photography lies in its ability to 'edit' real life and hide some of its limitations. Just as the lounge disposition could be transported to another room, it could also be transferred to a person, its idiom of elegance rubbing off through the visual juxtaposition of a body in relation to objects and space.

Photography prompts us to think about the mechanisms behind the construction of abstract and delicate concepts such as 'respectability' or 'modern lifestyle', and to explore how they are visually rendered in historically specific circumstances. The banality of the Ngilima snapshots should not divert us from the fact that creating a sense of permanence, a sense of normalcy, is actually 'hard work',62 in a context of economic and political oppression. Hence to interpret the portraits of women in the lounge only as evidence of a patriarchal ideology of domesticity would fail to grasp the years of economic and personal investments behind the making of a 'home'. Given the rich array of details visible in the backgrounds of the portraits, one can consider the Ngilima photographs taken in the early years of Wattville's official establishment as visual records of the various decorative strategies that women used to transform sterile, bare, identical houses into personalised homes.

But as Dlamini argues in his book Native Nostalgia, quoting Lewis Nkosi, 'not everything people did was a response to apartheid'.63 While it is tempting to read 'resistance' into these photographs, the pertinence of the Ngilima collection is in its reminders of the richness of township life beyond coping with apartheid. The abundance of photographs depicting birthday parties, weddings and so many other social events are clear evidence that people were not always resisting, but often just enjoying themselves. If the Ngilima pictures come across as 'ordinary', it is a sign that the Ngilimas succeeded in framing their subjects within a mainstream middle-class urban culture to which they were laying claim.

Dlamini pleads against the contemporary 'master narrative of black dispossession that which masks deep class, ethnic and gendered fissures within black communities'. Reading subtle signs of social distinction is for him a vital part of challenging the image of townships as dreary, dull and uniform. Ultimately, the Ngilima photographs (combined with the memories that are potentially inscribed in them) are the expression of people's effort to invest memories, social landmarks and differentiation in what was initially a homogeneous site. The lounge portraits also point to the remarkable ability of township dwellers to re-imagine their reality and project more positive self-images, even when their actual situation often failed to fulfil these aspirations.

1 This article was initially written for the conference 'Media Homes: Material Culture in Twentieth-Century Domestic Life', University of Amsterdam, which took place on 29 June 2012. I would like to thank the UWC History Department for giving me a chance to present an early draft of this work. Comments from David William Cohen and Patricia Hayes were of particular importance in the revision of this piece.

2 Shamil Jeppie, 'Interiors, District Six, c.1950' in Hilton Judin and Ivan Vladislavic, eds., Blank_ Architecture, Apartheid and After (Rotterdam: NAi, 1998).

3 Alf Ludtke, ed., The History of Everyday Life: Reconstructing Historical Experiences and Ways of Life (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1995), 14. See also Peter Burke, Eyewitnessing: The Uses of Images as Historical Evidence (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2006), 10; Joeri Januarius, 'Picturing the Everyday Life of Limburg Miners: Photographs as a Historical Source', Internationaal Instituut voor Sociale Geschiedenis, 53 (2008), 297.

4 Dorothee Wierling, 'The History of Everyday Life and Gender Relations: On Historical and Historiographical Relationships' in Ludtke, ed, The History of Everyday Life, 151.

5 The original negatives have recently been transferred from the Ngilima household to the Historical Papers Research Archive, William Cullen Library, University of Witwatersrand, Johannesburg. The digital version of the collection is available to the general public through the university. An ongoing project is working towards creating a local archive and making the collection accessible online as well.

6 Ludtke, ed., The History of Everyday Life, 14.

7 Januarius, 'Picturing the Everyday Life of Limburg Miners', 297. See also Januarius, 'Feeling at Home: Interiors, Domesticity and the Everyday Life of Limburg Miners in the 1950s,, Home Cultures, 6, 1 (2009), 43-70.

8 Liam Buckley, 'Photography, Elegance and the Aesthetics of Citizenship' in Elizabeth Edwards, Chris Gosden, Ruth B. Phillips, eds., Sensible Objects: Colonialism, Museums and Material Culture (Oxford: Berg, 2006).

9 Benoni is located in the East Rand, presently known as Erkuhuleni metropolitan municipality, about twenty-five kilometres east of Johannesburg.

10 Benoni City Times, 'Wattville: A Jewel of Benoni', 21 January 1949.

11 Gary Minkley, '''Corpses behind screens": Native Space in the City' in Hilton Judin and Ivan Vladislavic, eds., blank_Architecture, Apartheid and After (Rotterdam: NAi Publishers, 1998), 212.

12 The Rand Daily Mail, 17 January 1934 and 21 August 1935; The Star, 8 February 1934.

13 Philip Bonner, 'Family, Crime and Political Consciousness on the East Rand, 1939-1955', Journal of Southern African Studies, 14(3), 1988, 393-420.

14 These conditions included official marriage status, a pass which enabled the person to reside in the Benoni area, a full time job in the area which he should have been doing for several years.

15 Interview with Thembi Mateta, Soweto, 20 May 2011.

16 Christo de Coning, Income and Expenditure Patterns of Urban Bantu Households: Benoni Survey (Pretoria: Bureau of Market Research, University of South Africa, 1962).

17 The 'While-you-wait' camera used light-sensitive paper instead of film. The image would be exposed onto the paper, then developed within the camera. A positive image would be achieved by photographing the initial exposed paper. For a more extensive explanation, see Heike Behrend and Tobias Wendel, Snap Me One! Studiofotografe in Afrika (Munchen: Prestel Verlag, 1998). An alternative explanation for those 'missing negatives' could be that Ronald simply did not adopt a policy of preserving negatives until much later in his photographic career.

18 All of the photographs that feature in this article are reproduced with permission from the Ngilima family, represented by Farrell Ngilima. I am very grateful to the Ngilima family for granting me these rights.

19 Pierre Bourdieu, 'The Social Definition of Photography' in Jessica Evans and Stuart Hall, eds., Visual Culture: The Reader (London: Sage Publications, 1999), 170.

20 These airbrushed portraits are identifiable thanks to their characteristic oval wooden frames and light blue background. They became really popular in the 1940s and 1950s, in particular as post-mortem wedding portraits. For more details on this genre, see Sophie Feyder, '"Think Positive, Make Negatives": Black Popular Photography and Urban Identities in Johannesburg Townships, 1920-1960' (Unpublished M.Phil. thesis, Leiden University, 2009), chapter 2.

21 Ronald Ngilima appears explicitly only once in the National Archives (KBN 3/2/47 N1/4/3 {62/60}), under the death notice issued by the Benoni Commissioner, dating from March 1960. The file does not specify the cause of death. But according to his daughter Doreen, he was called in the middle of the night to help a 'homeboy' and was then ambushed a few metres away from his house. He died a few hours later of a head injury. No one was ever inculpated for his murder.

22 So far, I have been able to identify only 41 photos depicting African Old Location interiors, as against 193 Old Location pictures that were taken outside. In comparison, 275 pictures of Wattville were taken inside and only about 133 photographs of Wattville taken outside.

23 Out of the 275 indoor pictures, 152 were taken in the lounge. Other indoor pictures were taken in the dining room (30), hallway (67), bedroom (17) and kitchen (9).

24 Lynn Spigel, Welcome to the Dreamhouse: Popular Media and Postwar Suburbs (Durham: Duke University Press, 2001), 15.

25 Arjun Appadurai, 'The Colonial Backdrop-Photography', Afterimage, (March-April 1997), 4.

26 According to Philip Bonner, 979 out of 1179 houses were privately built in 1944. Philip Bonner, 'Eluding Capture: African Grass-Root Struggles in 1940s Benoni' in Saul Dubow and Alan Jeeves, eds., South Africa's 1940s: Worlds of Possibilities (Cape Town: Double Storey Books), 176.

27 Owen Crankshaw, 'Class, Race and Residence in Black Johannesburg, 1923-1970', Journal of Historical Society, 18, 4 (2005), 353393.

28 Interview with Joyce Mhlanga Ndlazilwane, Daveyton, 24 February 2012.

29 Crankshaw, 'Class, Race and Residence in Black Johannesburg, 1923-1970', 387.

30 Leslie J. Bank, Home Space, Street Styles: Contesting Power and Identity in a South African City (London: Pluto Press, 2011), 84.

31 Mia Brandel-Syriel, Reeftown Elite (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1971), 14.

32 Timothy Burke, Lifebuoy Men, Lux Women: Commodification, Consumption, & Cleanliness in Modern Zimbabwe (Durham & London: Duke University Press, 1996). See also Lynn Thomas, 'Skin Lighteners, Black Consumers and Jewish Entrepreneurs in South Africa' , History Workshop Journal, 73,1 (Spring 2012).

33 Bank, Home Spaces, Street Styles, 171.

34 Interview with Dumi Dlamini, Wattville, 28 April 2011.

35 Shamil Jeppie describes District Six interiors in the 1950s as follows: 'Apartments were too small to set spaces aside for special occasions, such as a hall to receive visitors or a lounge for entertaining them, and apart from the kitchen and toilet every room was usually occupied. Although the amount of space obviously depended on the size of the family, rooms served multiple purposes - lounges, for instance, would be transformed into bedrooms at bedtime.' Shamil Jeppie, 'Interiors, District Six, c.1950' in Hilton Judin and Ivan Vladislavic, eds., Blank_ Architecture, Apartheid and After, 390.

36 Bank, Home Spaces, Street Styles, 51-53.

37 Interview with Khubi Thabo, Daveyton, 17 June 2011 and Joyce Watson Mohammed, Daveyton, 15 June 2011.

38 Ellen Hellmann, Rooiyard: A Sociological Study of an Urban Slum Yard (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1948).

39 Gary Minkley, '''Corpses behind screens"', 210.

40 Arjun Appadurai, 'The Colonial Backdrop-Photography'.

41 Initially launched in 1951, The African Drum was one of the first magazines in South Africa to explicitly address a black audience. This initiative failed within a few months for lack of readership, until James Bailey took over the magazine and gave it a new direction and style, after which it popularly became known simply as Drum.

42 On the depiction of tribal identity in Drum magazine, see Darren Newbury, Defiant Images: Photography and Apartheid South Africa (Pretoria: Unisa Press, 2009), chapter 2; for a broader case study on the theme, see Cecile Badenhorst and Charles Mather, 'Tribal Recreation and Recreating Tribalism: Culture, Leisure and Social Control on South Africa's Gold Mines, 1940-1950', Journal of Southern African Studies, 23(3), September 1997, 473-489.

43 Jenny Robinson, Ordinary Cities: Between Modernity and Development (Abingdon: Routledge, 2006), 7.

44 I wish to thank Patricia Hayes for raising this point about the difference between a backdrop and 'a portrait of a space.

45 Liam Buckley, 'Photography, Elegance and the Aesthetics of Citizenship' in Elizabeth Edwards, Chris Gosden, Ruth B. Phillips, eds., Sensible Objects: Colonialism, Museums and Material Culture (Oxford: Berg, 2006), 189.

46 David Goodhew, 'Working-Class Respectability: The Example of the Western Areas of Johannesburg, 1930-55', Journal of AfricanHistory, 41, 2 (2000), 241-266.

47 Buckley, 'Photography, Elegance and the Aesthetics of Citizenship', 183.

48 Ibid., 191

49 Dorothy Driver, 'Drum Magazine (1951-9) & The Spatial Configurations of Gender' in Stephanie Newell, ed., Readings in African Popular Fiction (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2002).

50 Belinda Bozzoli and Mmantho Nkotsoe, Women of Phokeng: Consciousness, Life Strategy, and Migrancy in South Africa, 19001983 (Portsmouth: Heinemann, 1991).

51 Ibid., 91

52 Bank, Home Spaces, Street Styles, 179

53 Interview with Rose Mhlanga, Wattville, 30 March 2011.

54 Michel de Certeau, The Practice of Everyday Life (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1984), 34.

55 Pauline Morris, A History of Black Housing in South Africa (Johannesburg: South African Foundation, 1981), 49.

56 BMA, Minutes of Advisory Board, 22 May 1954. Quote from Pauline Morris, A History of Black Housing in South Africa (Johannesburg: South African Foundation, 1981), 50.

57 Group workshop at the old-age centre called Luncheon Club, Wattville, 16 May 2012.

58 The National Party's coming into power coincided with the year Wattville was officially created: 1948.

59 Lynn Spigel, Welcome to the Dreamhouse.

60 Interview with Lili Mkhulisi, Wattville, 17 May 2012.

61 Rebecca Ginsburg, '"Now I stay in a house": Renovating the Matchbox in Apartheid-era Soweto', African Studies, 55, 2 (1996), 135.

62 I use here Appadurai's expression when describing the production of locality as 'hard work. Arjun Appadurai, Modernity at Large: Cultural Dimensions of Globalization (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1996), 178.

63 Jacob Dlamini, Native Nostlagia (Johannesburg: Jacana Media, 2010), 14. [ Links ]