Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Kronos

versão On-line ISSN 2309-9585

versão impressa ISSN 0259-0190

Kronos vol.35 no.1 Cape Town Nov. 2009

ARTICLES

Land redistribution politics in the Eastern Cape midlands: the case of the Lukhanji municipality, 1995-2006

Luvuyo Wotshela

Geography Department, University of Fort Hare

ABSTRACT

Since its initiation, South Africa's post-apartheid land reform programme has generated extensive analysis and critique that in turn has yielded a body of scholarship. Discussion revolves around the official policy of the programme, the challenges associated with its implementation and its reception at local levels. It cannot be overstated that much of the discourse on the formulation of the programme itself commenced in the dying years of apartheid, through a series of workshops, policy conferences, research projects and publications. Prompted by glaring disparities in the country's social and living conditions and primarily by entrenched imbalanced landownership, contemporary land reform dialogue has a well-built backdrop. What, however, is our understanding of local community politics that played perceptible roles in triggering land redistribution and facilitating patterns of settlement? This article gives some insight into a veiled history of interplay between community mobilisation politics, governance and official land reform policy in the Lukhanji municipality of the Eastern Cape during South Africa's transitional years of 1995 to 2006. After outlining how land redistribution was initially driven by forces operating outside government action, the article proceeds to illustrate the frailty of the government land redistribution accomplishment. Moreover, it demonstrates the complex nature of a rural setting that has arisen from community-facilitated and incipient government land redistribution achievements in the area.

Introduction

In recent times, South Africa's Eastern Cape has offered an opportunity for those writing on rural transformation to discuss community dynamics and local politics in relation to national government programmes. One of these, the land reform programme, has been, for many, a popular subject since the inception of democracy well over a decade ago. The land redistribution programme has been pervasive in shaping some Eastern Cape post-apartheid municipalities and, in that process, has impacted on what was previously a homeland 'tribal authority land base'. Statistics alone do not necessarily reflect the nature of the dynamics and nuances associated with this change. It is, however, worth noting that between the years 1995 and 2006, some 222 000 hectares of land were redistributed in 914 different transfers within the Eastern Cape Province.1 Not much of these portions of land were redistributed to chieftaincies, a marked contrast to the tribalisation pattern pursued by the previous apartheid government.

Perhaps this is unsurprising, given the limited role of chiefly authority following the inauguration of the new government in 1994. It was only when the 2003 Traditional Leadership and Governance Framework Act constitutionally established the role of chiefs within local, provincial and national government structures that their authority assumed official status in the country. Between 1995 and 2003 chiefs largely held ex-officio positions, with non-executive powers, within local government configurations.2 The impact of the 2003 Act is yet to be assessed or quantified at local levels, but it is safe to say that chiefly and populist politics did not just disappear in the rural areas of the Eastern Cape. Five out of six district municipalities created since the year 2000 include territories previously linked to the apartheid tribal authority system. These constitute the eastern and northern parts of the province made up of land and settlements of the former homelands Ciskei and Transkei. In part, the present municipal dispensation allows for the extension of the socio-political dynamics of these former homelands onto newly redistributed lands.3

Generally, South Africa's post-1994 land reform policy revolves around three key programmes. The first of these is the restitution of land rights - a legislative process established by means of the 1994 Restitution of Land Rights Act. This provides the opportunity for individuals or communities who were dispossessed of their properties or forcibly removed from land during and after the year 1913, to claim forms of compensation. Secondly, the redistribution of land, driven by essentials of equity, was aimed at providing the disadvantaged and poor people with access to land for residential and productive purposes. The application of a land redistribution policy has been modified over the years (see below). At the outset, the ANC-led government's Reconstruction and Development Programme (RDP) aimed at transferring 30% of commercial agricultural land to black ownership by the end of 1999. Obviously this was an ambitious intention and was not likely to be achievable within a short-term period for an array of reasons, ranging from land and capital availability and bureaucratic bottlenecks to attitudes and commitments of commercial landowners. There was also a third programme, which seeks to reform tenure security. This aimed to address and formalise different forms of landholding systems, which hitherto were either informal, communal or carried lesser rights.4

Literature on these land reform programmes has constituted the linchpin of post-apartheid literature on aspects relating to democracy, redistribution of resources as well as on political and social change. Indeed, in recent years land reform has not only been the subject of agriculture, residential planning and the natural environment, but it also delves into the many discourses of human rights elements. Largely, the cross-disciplinary nature of discussions and writings generated weaves through the humanities, the social and natural sciences. Importantly, from their earliest conceptions in the early to mid-1990s, each of the post-apartheid land reform programmes also began to generate and attract an array of research and interests. Restitution research mainly looked at challenges related to unravelling historical rights and the verification of claims in the context of the complexities of demographic change and mobile 'communities'. Land redistribution studies focused then - and still focus now - on white commercial farming, its monopoly over landownership, and its need to transform. More specifically on this subject, the property clause that protects ownership rights has been seen as the main stumbling block against a faster-paced land redistribution programme.5 Meanwhile, tenure reform research has looked deeply into groups that are frequently vulnerable to evictions and those whose rights to land are insecure, particularly within communal settings.

This article focuses primarily on the land redistribution programme. It offers an examination of current rural dynamics and the politics of land redistribution within the Lukhanji Municipality in the Eastern Cape.6 In addition to providing a brief background on the formation of this municipality, I introduce three key elements of the process of land redistribution in that area. Firstly, I argue that the forces and elements that initially drove the land redistribution process had a strong historical momentum from the apartheid resistance movement of the late 1980s and early 1990s. It cannot be over emphasised that South Africa's land reform programme emerged from that sustained civil mobilisation process during this period. Groups and individuals who had mobilised and coordinated the resistance campaign had formed a home-grown civil movement. Even though this grew unevenly in different parts of the country, and especially in the Eastern Cape, it effectively crippled homeland administration.7 In the course of democratisation in the early 1990s, its members invaded portions of state land, irrigation schemes, municipal commonages and rural village pastureland. It was their local political activity that provided the impetus for the initial phase of land redistribution rather than any government-led action.8

Secondly, the article examines how a shift in government policy towards land redistribution affected the Lukhanji Municipality. From 1995 to 1999, at a time when certain groups were still invading land, the Department of Land Affairs (DLA) made Settlement Land Acquisition Grants available. These consisted of a R16 000 grant per household for purchasing land directly, either from willing private sellers or from the state. Purchasing households had to constitute themselves into legal entities known popularly as trusts. At first only poor households with a monthly income of less than R1 500 qualified for these grants. Because their amounts were so small, as far as the first cases of private land transfer were considered, the tendency was to amalgamate multiple grants to make single land purchases in Lukhanji. Following a ministerial change within the DLA, the Land Redistribution for Agricultural Development Act was promulgated in 1999. This offered larger grants (ranging from R20 000 to R100 000), calculated on the basis of each individual purchaser's existing resources or own contribution to the purchased land. These grants became the norm, especially from 2002 onwards.9 This article looks at the dynamics associated with that policy shift within the Lukhanji Municipality.

Thirdly, linked to the above two issues, I illustrate how the DLA's facilitation of land redistribution became highly influenced by groups who had acquired key power positions. Because land redistribution was (and is still) essentially a market-driven process, based on a willing-seller, willing-buyer principle, it offered particular opportunities for influential groups or individuals that were in stronger positions to organise themselves into purchasing entities ahead of others. Again, this is significant in illustrating how official policy was driven and facilitated by 'community' dynamics and politics operating at a local level. Within Lukhanji, prominent local civil associations, community land committees, the public service sectors and even remnants of the Ciskei homeland tribal authority network brokered and facilitated land transfers. These were groups whose positions gave them early access to information enabling them to activate land purchase negotiations and family support schemes to their own advantage.

The Lukhanji Municipality

The Lukhanji local municipality, occupying 4 231 square kilometres, is centrally positioned within the Chris Hani District Municipality, which, in turn, is located in the innermost precinct of the Eastern Cape Province (see Figure 1). Established in the aftermath of the 2000 local government elections and headquartered in Queenstown, Lukhanji is a classic case of a municipality that reintegrated areas of former 'white South Africa' with pieces of the former Ciskei and Transkei. That reintegration was a reversal of a more than two decades long territorial segregation process. This process had been under way since 1975 when, firstly, Kaiser Matanzima's Transkei accepted 'independence' to become the first apartheid homeland in 1976. In granting Transkei 'independence' at the time, the National Party government also embarked on the process of delineating the boundaries of Lennox Sebe's Ciskei. Western Queenstown farmland, therefore, was carved up for the consolidation of one of the new seven Ciskei magisterial districts, this being Hewu in the very northern part of this fledgling Ciskei homeland.

Almost all of the other new Ciskei magisterial districts - Keiskammahoek, Middledrift, Mdantsane, Peddie, Victoria East (or Alice) and Zwelitsha - received many displaced families from various parts of South Africa in the process of this homeland consolidation. Hewu district itself became widely known for receiving the majority of displaced people from Glen Grey and Herschel, who dissociated themselves from Transkei's acceptance of 'independence'. The fate of the dispossessed, relocated to some of the most dramatic of apartheid's transit camps and aptly reflected in the Surplus People's Project Reports, constituted one of the major foci of 1980s writings on popular struggles.10 The impact of their relocation on Hewu was startling.

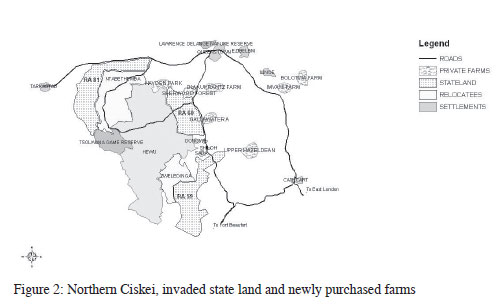

Hitherto, Hewu had been home for African landowning families associated with the nineteenth-century Moravian and Methodist mission settlements of Shiloh, Oxkraal and Kamastone, which were primarily rural. From the early 1960s, coinciding with the notorious National Party government's betterment programme or rural re-villagisation, Hewu had been constantly replanned. The sudden emergence of Sada, a residency established to accommodate victims of farm removals on Shiloh's agricultural land from 1964, had opened the inmigration floodgates. As the pace of removals stepped up with Hewu's absorption of Glen Grey and Herschel relocatees in the next decade, the district had become a crucial northern Ciskei region, facilitating population redistribution and settlement expansion. Its resources were remapped and replanned as many of the relocatees were squeezed into newly formed 'tribal authority' -aligned villages in this district's central and further northern parts. Around its administrative town of Whittlesea housing and public works proliferated. An urban zone, Dongwe or Ekuphumleni (Whittlesea North), consolidated Sada, absorbed those who did not receive rural land as well as the class of civil servants that had been emerging from the early 1980s. Further north-east of this burgeoning Hewu and Whittlesea settlement, the newly hatched Transkei homeland had also absorbed the southeastern Queenstown townships of Ilinge (formed similarly to and simultaneously with Sada) and Ezibeleni (or Queensdale), as well as the outlying rural areas that stretched eastwards to Lady Frere, which had previously formed parts of the Glen Grey district (Figures 1 and 2).11

Queenstown, now truncated and segregated, was left sandwiched between Hewu, which took shape in the northern Ciskei, and the north-western Transkei. Its new periphery remained largely rural, with white commercial farms and farflung farm-workers' homes and an overgrown nineteenth-century Methodist Mission settlement, Lesseyton, on its western outskirts. Whilst Queenstown continued to serve and administer these outlying areas, it also became a typical 'homeland-border consumer town' which carried this identity well beyond the de-establishment of Transkei and Ciskei in the post-1994 period. As expected, the re-integration of these previously politically divided settlements was tricky, even though political and administrative processes combined to plot their path forward. In particular, in the 1995 local government elections - in which the membership of Transitional Local Councils (TLCs) was decided through proportional representation - Queenstown and Whittlesea, as well as their outlying areas, fell decisively under the control of the African National Congress (ANC). The transitional local governments, during their brief existence from 1995 to 1999, focused on amalgamating the administrations of these dense urban settlements around Queenstown and Whittlesea. Queenstown TLC amalgamated the administration of the town with its previously segregated but politically highly mobilised townships of Mlungisi and New Rest, as well as with the former northwestern Transkei settlements of Ilinge and Ezibeleni. Whittlesea TLC joined the administration of Whittlesea Village, Shiloh, and the townships of Dongwe and Sada.12 Essentially, the process of re-integrating the three previously segregated zones of the former homelands of Ciskei and Transkei around formerly 'white Queenstown' was in motion.

Whilst this process was at work, the thorny issue of traditional authority, or chieftaincy, continued to confront elected local authorities. As indicated, there was no clarity regarding functions and authority of chiefs prior to the application of the 2003 Act. Suffice it to say, the ANC-led government was indecisive as to how traditional authority would sit within the evolving democratic establishments. It had amended a 1993 Transitional Local Government Act to clarify the role of local authorities in rural areas on the eve of the 1995 local government elections. The amendment provided a district council model that established a two-level structure, comprising demarcated district councils at a sub-regional level and various options for structures at village level. Adopting the TLC model, local authorities at rural level were also transitional, referred to as Transitional Rural Councils (TRCs), and were, in time, expected to evolve into fully democratic structures. Embracing the reconciliatory tone of Nelson Mandela's government, the TRC model allowed white farmers to participate in rural governance and was, similarly, made palatable to chiefs or 'traditional authorities' by offering them 'ex-officio positions'.13

Given that civic associations, and the liberation movement in general, had challenged chieftaincy and the apartheid tribal-authority system during the 1980s and early 1990s, this was a remarkable compromise. Clearly the ANC-led government did not want to take chances in respect of its winning any of the rural constituencies within its ranks and may have been well aware of the persistence of the patronage network that chieftaincy had produced over the years. In most of the outlying rural areas of Whittlesea, which included Hewu and parts of Glen Grey where apartheid chieftaincy had been entrenched by homeland leaders Sebe and Matanzima, TRC configurations emerged. The authority of these councils extended to Queenstown farms, farm-worker settlements and Lesseyton, which as indicated had grown into an enormous settlement on the western periphery of Queenstown by 1995. Critically, these TRCs fell within the Stormberg District Council framework, a remnant of the rural white area's divisional council administrative system that stretched from Middelburg in the west to Elliot in the east.14

The ANC government's move to replace transitional authorities with fullyfledged local government establishments was swift enough, as reflected in its promulgation of the 1998 Municipal Demarcation Act.15 This legislation supplanted apartheid spatial demarcations and integrated TLCs and TRCs to rationalise municipal boundaries. The first fully democratic elections of municipal councils, to serve a five-year term of office within the newly demarcated municipalities, were held in December 2000.16 Demarcation in the Eastern Cape largely retained the 1995 sub-regional district councils, but these were reconfigured and renamed as district municipalities, with their respective directors and departmental staff. Under this arrangement, the Eastern Cape Province was divided into six district municipalities and thirty-eight local municipalities. Stormberg, around Queenstown, was renamed Chris Hani District Municipality and it expanded on the re-integration process that was already in motion around this town and its outlying area. The Chris Hani District Municipality integrated the white farming districts west, north, and east of Queenstown with much of the northern Ciskei and parts of the north-western Transkei. In its innermost part, a new Lukhanji Municipality integrated the Queenstown TLC and TRC, Whittlesea TLC, Hewu TRC, and parts of Cathcart and Glen Grey TRCs into a single local municipality (Figure 1).17

Not unexpectedly, the main concentration of Lukhanji's nearly 300 000 people was, by the year 2006, in the area in and around Queenstown, which encompassed Mlungisi, Happy Rest, Ezibeleni and Ilinge in the south. During this period, Lukhanji Municipality also administered some 120 semi-rural villages as well as the dense urban area around Whittlesea, where over 100 000 people lived. The new municipality had its offices in Queenstown housing five main directorates: Community Services, Technical Services, Administration and Human Resources, Financial Services, and Estates and Land Affairs. The municipality had added extension offices for auxiliary services in Whittlesea and Ezibeleni to cater for a growing demand.18 Crucially, both of these areas had been subjected to the invasion and occupation of land for much of the decade preceding the formation of the municipality. Equally important, dynamics associated with the redistribution of land in the course of invasions manifested themselves in post-apartheid municipal configurations. The following section looks back at this important historical phase.

Invasions, occupations and land redistribution, 1991-1995

The decade from the early 1990s within the Eastern Cape was characterised by land invasions and the expansion of Ciskei and Transkei settlements, as well as neighbouring townships, onto portions of state land and open commonages. Similar invasions of commonage lands and public facilities (like golf courses) were sporadic in a number of towns such as Jeffrey's Bay, Humansdorp, Port Elizabeth, Grahamstown and Cradock in the western parts of the province. Redistribution of these portions of land was not facilitated by the government or its agencies, but by community leaders. Decisive moments came with the formation of community residents' and civic associations that agitated for the democratisation of local governance. The period and intensity of this activity varied from place to place but, generally, had climaxed by the early 1990s.19 These protest actions confronted the apartheid-created black local authorities in urban areas and the tribal authorities within homelands with immense challenges.

In the northern Ciskei area, community-driven land redistribution revolved around dissident groups, most of whom were remnants of Glen Grey and Herschel relocatees. They had not received land allocations because they dissociated themselves from the tribal authorities designated for them in the course of their resettlement during the mid-1970s. Over the years, their ideological stance drew sympathy from civil and non-government organisations. One of these included the influential Border Rural Committee (BRC) which had advocatedcommunity land rights and also mobilised against removals from the late 1970s onwards. Its influence on the two remnant groups of relocatees was immense, resulting in the formation of two militant residents' association groups by the late 1980s: the Thornhill Residents' Association, named after the transit camp that initially accommodated Herschel relocatees, and the Zweledinga (meaning 'Promised Land') Residents' Association, named after the resettlement site of Glen Grey relocatees. Simultaneously, landless families within the old Hewu rural villages and those without housing in the Whittlesea urban settlements of Sada and Dongwe had united to form the Hewu Land Committee (HLC), agitating for their residential and land needs. The dynamics surrounding formation of these organised associations and committees, all with deep histories which vary from case to case, are complex.20

The dying years of apartheid rule coincided with the breakdown of the tribal authority system. During this period, the residents' associations of Thornhill and Zweledinga and the Hewu Land Committee all launched themselves into key power positions. In the ensuing years they took control of most tribal resources, such as agricultural lands and irrigation schemes. It should be emphasised that the Thornhill and Zweledinga Residents' Associations believed they were owed land from the 1970s relocation process by the South African government. Thus they responded by invading the state land neighbouring northern Ciskei from 1992 onwards. They were joined by followers of the Hewu Land Committee as well as by many other groups and individuals, so that by 1997 some 25 000 hectares of previously unallocated state land had fallen into the possession of significant numbers of households from the former northern Ciskei. Portions of this constituted about 15 000 hectares of farmland further south-west of Queenstown known as Released Area 60 (RA60). Others constituted another 10 000 hectares of released farms (RAs 59 and 81), which was meant for the further consolidation of resettlement areas for Glen Grey and Herschel relocatees (Figure 2). All these portions suddenly, in the space of three years from 1993 to 1996, became a zone of new residential sites for well over 5 000 households. RA60 was the main target area and, in the course of its invasion, old farm boundaries disappeared, fences that impinged on newly-opened footpaths were cut, and remaining ones were moved to corral new residential sites.21

Significantly, newly fenced residential sites resulting from invasions were big enough to accommodate houses. These varied from makeshift to elaborate; they also included vegetable or crop gardens and, occasionally, kraals, fowl-runs and pigsties. Paradoxically, though resulting from informal occupations, their layout pattern replicated apartheid betterment-type villages, in the sense that residential zones were centrally organised and surrounded by open land, used for grazing, burial purposes and other public and social facilities.22 Perhaps this was, and is, indicative of the depth of knowledge and ideas of land use practice that betterment planning bred in its legacy of nearly five decades. A point has to be made that many of the land invaders were successive generations to those who had been documented for resisting rehabilitation and betterment schemes in different rural areas of South Africa during the mid-twentieth century.23 Essentially, successive generations had grown within betterment villages and had been 'normalised' to prevailing standard land use practices. Unsurprisingly, they extended such practices onto land they themselves had secured, even without official government intervention.

Even so, the haphazard manner of land invasion in RA60 meant that households varied significantly in size, social capital and wealth. The new villages effectively accommodated people with different needs, ranging from individuals and groups who only required residential sites with basic services, to those who pursued agricultural options, especially stock farming. The rapid increase in population density on some portions of this state land also precipitated government investment in basic services and social infrastructure. Indeed the governments of Mandela and of Mbeki, made a social commitment to provide for the basic needs of residents in informal settlements - a commitment which prompted some writers to view land-related needs as one of many elements of human rights.24 Overall, invasion and settlement of this and other neighbouring state lands amounted to an expansion of the former Ciskei's boundaries onto land that had previously been held by the South African government.25

A similar process was taking place in the very close proximity of Queenstown and its outlying townships of Mlungisi, New Rest and Ezibeleni, throughout the 1980s until the formation of the Queenstown TLC during the mid-1990s. As in the neighbouring northern Ciskei, militant residents' or civic associations mobilised groups that bore land- or service-related grievances.26 Land and residential needs were escalating, as was clearly illustrated by the proliferation of backyard tenancy in the Mlungisi and Ezibeleni settlements. Ezibeleni particularly accommodated a small number of livestock owners who held informal grazing rights on the commonage portion whilst it was still under Transkei's jurisdiction. However, as the Transkei government's control dwindled and resistance to the black local authority within Queenstown swelled, Ezibeleni and Mlungisi civic associations expanded their profiles and popularity by encouraging invasions of the Queenstown and Ezibeleni commonage portions from 1993 onwards.27

After 1994 some 7 000 hectares of Ezibeleni and Queenstown commonage land was placed under the jurisdiction of the Queenstown TLC. In its earliest formation, this TLC had foreseen the mounting pressure on open commonage land. As a result, it had proclaimed 1 300 hectares as a nature reserve (the Lawrence de Lange Reserve) on the northern mountainous area of the commonage land. Another 3 000 hectare portion of this commonage had been divided into sixteen grazing camps that were leased out to private farmers.28 Despite this the unauthorised occupation of remaining portions continued unabated, notwithstanding the fact that some leading members of the mobilising civic associations had by now joined Queenstown TLC as either officials or councillors. Throughout the mid-to-late 1990s and up to the early 2000s, the informal settlement continued to expand onto portions of the commonage, alongside Mlungisi in the west, and near Ezibeleni further east. Recipients of new residential land included numerous ex-farmworkers from the neighbouring farm districts and small towns of Dordrecht, Hofmeyr, Tarkastad and Sterkstroom. They also included household members from the neighbouring areas of the former Ciskei and Transkei. Their entry mechanism into these newer settlements was via peer groups, friendship associations, family relations or other social networks, or via political connections through local committees that were largely remnants of civic associations.29

Queenstown's proximity to major roads and rail routes - which linked the town to other parts of the province as well as to the major workplaces of many migrants, such as Cape Town, Kimberley, Welkom and Johannesburg - contributed significantly to its attraction as a place to settle. Its easy accessibility as well as the existence of a wide range of basic services became important pull factors. More importantly, residential expansion in Queenstown and the neighbouring Whittlesea area in the form of continuing occupation of commonage and state land indicated the close connection between local politics, social dynamics and the proliferation of informal settlement.30 It also illustrated salient features that linked the countryside and urban settlements in parts of the Eastern Cape. The complex pre-existing settlement patterns and socio-political dynamics that had evolved prior to 1995 were to continue to play a crucial role once the government became directly involved in driving the land distribution process. The focus of the article now shifts to these.

The government land redistribution programme and its impact on Lukhanji, 1995-2005

The political and social circumstances surrounding demands for land, as well as the crisis of the proliferation of informal settlements, raised many questions for the new South African government from 1995 onwards. These questions related to the future shape and the servicing of poor black settlements. They also related to their institutional arrangements as well as their agrarian activities and their environmental impacts. There were new fears about the direction of commercial agriculture and its relationship to settlement planning. The new Ministry of Land Affairs under Derek Hanekom confronted the challenges directly. It designed a Land Reform Pilot Programme, which was to operate as a national programme but was to be guided in each of the nine provinces by a secretariat responsible to an interdepartmental steering committee. The latter constituted representatives from government departments, TLCs and TRCs, development NGOs, and civic associations.31

From 1995 the Eastern Cape Land Reform Pilot Programme (ECLRPP) covered most of what would become the Chris Hani District Municipality. It included six magisterial districts: Queenstown, Tarkastad and Cathcart (largely white-owned farmland), Glen Grey and Cofimvaba (formerly Transkei) and Hewu (formerly Ciskei). Although this programme included at least a notional provision of land and support resources for specific identified groups and individuals, its objectives regarding the reintegration of settlements were similar to the notions behind the formation of municipalities. Essentially, as the new municipalities endeavoured, the land reform programme aimed to reintegrate the zone around Queenstown and the northern end of Border-Kei that had previously been split between Ciskei, South Africa and Transkei. That the area was also chosen because of its political sensitivity cannot be sufficiently emphasised. Its level of organisation and the existence of applied community research were equally critical. Indeed, the Border Rural Committee had mobilised some 'communities' in the northern Ciskei. As this committee gradually facilitated development in the post-1994 period, it also investigated community politics and the status of state land in the former Transkei and around white farming areas.32 Its involvement in this manner also reflected the changing role of NGOs in a democratising South Africa. Its transitional role from mobilising communities resisting apartheid state policy to facilitating reform in the post-1994 period was clearly evident.33 This was a common trend for a number of NGOs in a post-1994 transitional South Africa.

Understandably, the DLA had little choice but to recognise informal settlements which resulted from invasions of portions of state land and commonage. The surveying and upgrading of sites as well as the formalisation and registration of ownerships became the main focus of the work of this department from 1996 onwards as settlements were also placed under the administration of their respective TLCs and TRCs. Further proliferation of new informal sites could not be prevented, though. Within RA60, Ezibeleni and Queenstown commonages, some councillors attached to Hewu TRC and Queenstown TLC connived with local committees to dispense land to new arrivals in return for political advantage and other favours. Thus, despite popular challenges to the tribal authority system, the patronage building methods associated with chiefly politics did not dissipate. Councillors and local committees took an insurgent, populist position, asserting themselves as representatives of the rural and urban poor, but in the process they also created and perpetuated new patronage networks.34

Meanwhile, the uncertainty regarding control of land and authority at local level had hindered the progress of the Eastern Cape Land Reform Pilot Project at most of its designated sites. Importantly, the realisation of the existence of various competing interests within these new settlements prompted some aligned individuals to break away and pursue private land purchases. Ironically, it was again segments of the Zweledinga and Thornhill Residents' Associations that came to the forefront at the time of the first land purchases, with the assistance of the Border Rural Committee. Common interests colluded, especially since one of the executive members of the Thornhill Residents' Association, Godfrey Ngqendesha, was also an employee of the Border Rural Committee. From 1995 onwards, Ngqendesha, together with members of the Thornhill and Zweledinga associations and the Border Rural Committee, found willing sellers, who owned farms bordering on parts of the occupied RAs 59 and 60 and other state land.35 As in other parts of the country in the post-apartheid context, farmers became nervous about their land rights and their capacity to deal with informal settlements, and many had opted to sell. Similar incidents, including instances of farmers who became trapped in unviable patterns of farming, feature prominently in other writing about rural transformation, especially in parts of the Free State Province.36

Undoubtedly, the approach to land redistribution adopted by Hanekom's ministry worked in favour of the intended purchases of the Thornhill and Zweledinga Residents' Associations. His ministry opted to steer a middle course when confronted with the popular rural movements that were invading and increasing the extent of communal land. Whilst it was committed to restitution and forms of common property, it did not assign itself to extend tribal resources. Rather, it preferred that newly redistributed farms be owned by legal entities or trusts that would be offered government subsidies to purchase land on the open market. Yet the subsidy system did not authorise the DLA to designate or control the number of beneficiaries. As noted, communities organised themselves into purchasing entities. A number of factors influenced the formation of these groups, ranging from social relations to co-operative practices and to political affiliations.37

After 1995, two purchasing trusts emerged from among the initial landinvading Thornhill and Zweledinga association members, who, in the process of invasion, had accumulated some resources, in different kinds of livestock. Using the Settlement Land Acquisition Grant (SLAG) option, some 108 Thornhill Residents' Association households formed a Joe Slovo Trust to buy farm portions of Sherwood Forest and Welcome Valley, which comprised some 1 279 hectares east of RA60 on the banks of the Swart Kei River. Another 106 households from the followers of the Zweledinga Residents' Association formed a Gallawater A Trust and purchased the 1 200 hectare Gallawater A farm, which neighboured on other invaded state land south of Whittlesea (see Figures 2 and 3). Importantly, not all members of the Joe Slovo and Gallawater A Trusts moved immediately onto their farms but those who did contributed to their densification since they were each originally intended for single household ownership and occupation. Within a few years of their acquisition, major problems were experienced in the upkeep of infrastructure and in securing reinvestment. This was despite their members' generation of income from livestock sales held on the farm sites.38

It is critical to emphasise that these DLA land transfers were carried out without any farmers' support programme. As a result, despite ongoing livestock sales, both the Joe Slovo and Gallawater A trusts failed as self-supporting agricultural ventures. Occasionally members leased tractors for ploughing from their neighbouring white farmers. This, however, did not help much and by 2002 cultivation had almost stopped on both farms. Their water-supply systems had collapsed, the fencing-in of animals was neglected, and much of the building infrastructure had become derelict. By now the new Lukhanji Municipality had absorbed these farms and the Hewu TRC villages, including newer settlements that had sprung up on occupied state land. Although the municipality took over some land administration functions, particularly re-fencing of grazing lands within villages, it did not try to provide a farmers' support programme to either of the trust-owned farms.39

For the next batch of three SLAG redistributed farms, the DLA took note of the lessons learned from the experiences of the Gallawater A and Joe Slovo trusts. The following three SLAG redistributed farms - Hayden Park, Upper Hayzeldean and Imvani, which were set up in 2001-2 - carried fewer trust members. Indeed, Hayden Park north of Hewu, which remained the biggest single transferred farm in Queenstown (1 781 hectares), was given to a trust membership of only 51 households. The number of members was also reduced considerably on Upper Hayzeldean farm (744 hectares) east of Whittelesa, where 27 households formed the Masizame Common Property Association (CPA), and at Imvani farm (1 471 hectares) south of Queenstown, where another 33 households constituted the Imvani Trust (see Figures 2 and 3). In spite of reduced numbers, redistribution of Hayden Park and Upper Hayzeldean farms was still politically motivated and driven essentially by the Hewu Land Committee, playing much the same role that the Zweledinga and Thornhill associations did in the formation of the Joe Slovo and Gallawater A trusts. Hewu Land Committee's leadership facilitated the purchases, and the beneficiaries were largely its adherents. They included members of the original Hewu households or their descendants. By embarking on these new agricultural land purchases these families were, in effect, acknowledging the declining production or agricultural options within their original sites, even though paradoxically they themselves were from lineages of landowning families.40

Thoko Didiza replaced Derek Hanekom as Minister of the DLA in 1999. Her tenure was immediately accompanied by policy change, as SLAG was replaced by the LRAD system from 2001. The latter, which envisaged building more of an emerging class of commercial farmers, was aligned to the Growth Employment and Redistribution (Gear) macroeconomic strategy that the ANC government had adopted during the latter part of Mandela's presidency. It was a clear shift from the policy of giving poor households access to new land for residential and productive purposes.

This policy shift was also reflected in the Lukhanji Municipality as the pattern of redistribution changed from 2003 onwards. The norm became the transfer of smaller portions to fewer individuals - who consisted of those who already possessed resources or potentially had capital to pursue agricultural activities. In the period between 2003 and 2006, fifteen portions of a total of 9 351 hectares, interspersed throughout various parts of the municipality, were transferred to only 24 households (see Figure 4). One of the bigger purchases was the second Imvani Trust (1 292 hectares) from which only eight households benefited. It was a classic case of the affluent benefiting - illustrated by the few members of the previously congested Imvani SLAG scheme (33 households) moving on to acquire a larger purchase. Significantly, unlike the earlier SLAG, most of the LRAD schemes involved a farmers' support programme in the form of brokering subsidiary funds for farming equipment, such as tractors, irrigation and dairy equipment. Since 2003, the Department of Agriculture has offered some form of extension service to most LRAD farms within Lukhanji - a turnaround of the policy adopted towards SLAG beneficiaries.41

A brief conclusion - what rural dynamic?

The literature on rural transformation in South Africa has generally emphasised the gradual decline in reliance on production or agriculture within the former reserves or homelands. The Lukhanji Municipality is no exception to such a generalisation. Hewu, one of the oldest rural areas of this municipality, had by 2005 still the semblance of agriculture, evidenced by livestock figures of almost 100 000 cattle, sheep and goats. That very same figure, though, indicated that only six per cent of stock-owning households had herds of ten or more animals - a staggering measure of livestock ownership concentration. Not surprisingly, earnings from employment, supplemented by state welfare payments and the informal sector, remain key sources of livelihood in this area.42

Is the land redistribution programme making a difference? The LRAD option is not meant to provide poor households locked within reserves with additional options on viable agricultural land. Rather, it envisages taking individual households, or members who have potential agricultural ventures, out of former homelands or communal villages onto new agricultural land. Such an option is more available within municipalities that had absorbed the formerly 'white magisterial districts' with large commercial farm units. It is less, or not even, available to municipalities that have been primarily constituted within the heart of the former homelands of Ciskei and, more especially, the Transkei. A preliminary perusal of land redistribution patterns between 1995 and 2005 does indicate that almost no land, or a very low percentage thereof, was redistributed within the municipalities of the latter category, including the district municipalities of O.R. Tambo and Alfred Nzo. By contrast within the same period, the district municipalities of Chris Hani (where Lukhanji is located), Ukhahlamba and Cacadu led land redistribution in the province. These municipalities incorporated commercial farms around and diagonally north of Queenstown to the Free State and Lesotho borders, farms in the old Albany, Karoo, Sundays and Gamtoos River valleys.43 There is, indeed, ample land on the market in this area.

Essentially, the land redistribution programme has gradually extended the social boundaries of former homelands and in the process this has evolved a complex rural dynamic. This cannot be analysed easily, because it requires an understanding of social networks and mobile resources that continue to link newly acquired farms with the original villages or settlements of new land beneficiaries. The majority of new farm owners who have benefited either from SLAG or LRAD options have not necessarily moved en masse to their respective farm sites. Most remain in their original homes even though they have moved some of their agricultural resources onto these newly acquired lands. Likewise, some of their livestock is spread between home and new farm land. By acquiring new land, new farm owners have expanded production options whilst they still remain in the reckoning within their original rural and peri-urban settlements. It is difficult to predict how this situation will evolve in the near or long-term future.

Lukhanji Municipality meanwhile realised by 2005 that the LRAD option was not likely to benefit many people from communal villages. Thus, together with the Chris Hani Municipality, it gradually concentrated on broadening rural benefits within dense communal rural villages. These included the reintroduction of fences and rotational grazing as well as the revival of irrigation schemes (irrigation schemes in the past were failures, largely because they were driven by homeland officials rather than being community initiatives). Provision for basic needs remained a priority in most of these rural villages and these included provision of water, housing, sanitation, electricity and roads. Clearly what is required is input from municipal and public works as well as from other government departments. Many residents in these rural villages felt that access to land, and the associated services and benefits, were basic essentials.

There is a growing literature on the general subject of South African land reform, but such nuances as evidenced in the salient aspects related to the politics of land redistribution in Lukhanji are yet to be explored in detail. This article contributes to our understanding of how local mobilisation politics have been incisive in driving the process of land redistribution. Researching local politics that are intertwined with complex community dynamics is daunting, largely because of challenges associated with understanding the language of its articulation. Despite such challenges, however, it is clear that mobilisation from below has contributed more than official policy in speeding up the pace of land redistribution in Lukhanji. The most substantial land redistribution resulted from invasions of state land from the early to late 1990s. The SLAG programme, which focused on giving access to poor households to new land, only provided some 8 300 hectares on nine farm portions between 1995 and 2002. Importantly, the national figure was itself was ridiculously low, since less than 1per cent of the total area classified as commercial farmland was transferred during the period from 1995 to 1999.44 In Lukhanji, the land transfer trickled at an even slower pace between 2003 and 2006. Less than 10 000 hectares were transferred to even fewer people than in the previous phase. It remains to be seen if this will change in successive years.

LUVUYO WOTSHELA teaches in Environmental and Historical Studies at the University of Fort Hare. He has been researching and writing on the politics of resettlement and change in the Eastern Cape, South Africa. He is the co-author with William Beinart of Oxford University of a forthcoming book on the social history of the prickly pear in South Africa.

1 Archives of the Department of Land Affairs, Document of the Eastern Cape Land Reform Office, East London, Land Transfer in the Eastern Cape 1995-2006 (hereafter DLA, EC Land Transfer 1995 -2006).

2 L. Ntsebeza, Democracy Compromised: Chiefs and the Politics of Land in South Africa (Cape Town, HSRC Press 2006): 256-299; [ Links ] J. Peires, 'Traditional leadership in purgatory: Local government in Tsolo, Qumbu and Port St Johns, 1990-2000', African Studies, 59, 1, 2000: 97-114. [ Links ] See also Act 41 of 2003, Traditional Leadership and Governance Framework Act, Government Notice 2336 of 2003.

3 L. Wotshela, Capricious Patronage and Captive Land: The Politics of Resettlement and Change in the Eastern Cape, 1960-2004 (Pretoria: Unisa Press, forthcoming). [ Links ]

4 Restitution of Land Rights Act 22 of 1994; see also Department of Land Affairs, White Paper on South African Land Policy, Pretoria (1997B) (hereafter DLA, 1997 White Paper): 9; [ Links ] T. Marcus, K. Eales and A. Wildschut, Down to Earth: Land Demand in the New South Africa (Durban: Indicator Press, University of Natal, 1996); [ Links ] C. Walker, 'Agrarian change, gender and land reform: A South African case study', Social Policy and Development Programme Paper Number 10, United Nations Research Institute for Social Development (UNRISD), April 2002: 37-39; [ Links ] C. Murray and G. Williams, 'Land andfreedom in South Africa', Review of African Political Economy, 61: 315-324. [ Links ]; R. Hall and L. Ntsebeza, The Land Question in South Africa: The Challenge of Transformation and Redistribution (Cape Town, HSRC Press, 2007): 6-20. [ Links ]

5 Hall and Ntsebeza, Land Question: 6-20.

6 The name Lukhanji derives from one of the mountains in the Stormberg range north of Queenstown.

7 W. Beinart and R. Kingwill, 'Eastern Cape Land Reform Pilot Project', Pre-Planning Report, Land and Agriculture Policy Centre Working Paper 25, 1995: 1-20. [ Links ]

8 L. Wotshela, 'Homeland consolidation, resettlement and local politics in the Border and the Ciskei Region of the Eastern Cape, South Africa, 1960-1996'. D.Phil. thesis, Oxford University (2001): 267-322. [ Links ]

9 See the Rural Development Strategy of the Government of National Unity, Government Gazette, No. 16679, Pretoria (1995).; DLA, Draft of Land Reform Policy Framework (11 May 1995); see also the White Paper on South African Land Policy, Pretoria (1997); Department of Land Affairs and Agriculture Policy Document, Land Redistribution for Agricultural Development, version 4 (07/02): 1-10; F. Ncapayi, 'Land demand and rural struggles in Xhalanga, Eastern Cape: Who wants land and for what?' M.Phil. Mini-Dissertation, UWC (2005): 61-82. [ Links ]

10 Surplus People's Project Report (SPP), Forced Removals in South Africa (Cape Town and Pietermaritzburg, The Project, 1983), see especially volume 2, The Eastern Cape: 84-87; [ Links ] L. Platzky and C. Walker, The Surplus People: Forced Removals in South Africa (Johannesburg: Ravan Press, 1985); [ Links ] W. Cobbett and B. Nakedi, 'The flight of the Herschelites: Ethnic nationalism and land dispossession', in W. Cobbett and R. Cohen, eds., Popular Struggles in South Africa (London: James Currey, 1988. [ Links ]

11 L. Wotshela, 'Territorial manipulation in apartheid South Africa: Resettlement, tribal politics and the making of Northern Ciskei, 1975-1990', Journal of Southern African Studies, 30, 2, June 2004: 317-337; [ Links ] R. Mears, 'Historical perspective of migration and urbanization in Whittlesea, Ciskei', Development Southern Africa, 10, 4:. 497-513; [ Links ] C. de Wet et al, 'Resettlement into the Whittlesea district of the former Ciskei', South African Journal of Ethnology, 20, 3, 1997: 133-140. [ Links ]

12 Wotshela, Capricious Patronage (forthcoming).

13 L. Ntsebeza, 'Rural governance and citizenship in post-1994 South Africa' in J. Daniel, R. Southhall and J. Lutchman, eds., State of the Nation: South Africa 2004-2005 (Pretoria: Human Sciences Research Council, 2005): 65-75. [ Links ]

14 Wotshela, 'Homeland consolidation': 291-322.

15 See Municipal Demarcation Act, No. 27 of 1998, Government Notice No. 19020.

16 Ntsebeza, 'Rural governance': 65-67; C. Seethal, 'Municipal challenges in the new South Africa: Case studies from the Eastern Cape Province', Paper presented in the Conference of the South African Geography Society, Stellenbosch, South Africa September 2005: 1-10. [ Links ]

17 Archives of Lukhanji Municipality in Queenstown, Lukhanji Integrated Development Plan Document (hereafter Lukhanji, IDP): 9-11.

18 Lukhanji, IDP: 45-46.

19 Wotshela, 'Homeland consolidation': 267-308.

20 Ibid: 303-304. W. Beinart, 'Strategies of the poor and some problems of land reform in the Eastern Cape', unpublished Paper, Bristol, July (1996): 7-16. [ Links ]

21 L. Wotshela, 'Agricultural and rural livelihoods and the priorities in the Eastern Cape', Case Study Report No 3 - Northern Ciskei, Provincial Growth and Development Plan (PGDP)': 72-77. [ Links ]

22 Ibid: 72-77.

23 See, for instance, P. Delius, A Lion amongst the Cattle: Reconstruction and Resistance in the Northern Transvaal (Johannesburg: Ravan Press 1996); [ Links ] A.K. Mager, Gender and the Making of a South African Bantustan, 1945 to 1959, (Oxford: James Currey 1999); [ Links ] G. Mbeki, South Africa: The Peasants'Revolt (London: International Defence and Aid Fund, 1984). [ Links ]

24 C. Walker, 'Agrarian change': 1-39; C. Murray and G. Williams, 'Land and freedom in South Africa', Review of African Political Economy, 61, 1994: 315-324. [ Links ]

25 Wotshela, 'Homeland consolidation': 267-308.

26 Interviews with Mr. M. Bula (former executive member of Queenstown Sanco), Queenstown, 13 October 1995 and Mr. G. Xoseni (first mayor of Lukhanji), Queenstown, 4 December 2003.

27 Archives of Lukhanji Municipality, in Queenstown, Municipal Records of Black Township Mlungisi, 1981-1993.

28 Beinart and Kingwill, ECLRPP: 1-30.

29 Wotshela, Capricious Patronage (forthcoming). Interview with Mr. G. Xoseni, Queenstown, 4 December 2003.

30 Wotshela, 'Homeland consolidation': 261-295.

31 Beinart and Kingwill, 'Eastern Cape Land Reform Pilot Project': 1-30.

32 Wotshela, 'Homeland consolidation': 261-308.

33 E. Jensen, 'Creating community-based tenure systems in Thornhill and Isidenge: An examination of group schemes for land reform in South Africa' (PhD thesis, University of Wisconsin-Madison, 2002): 105-127; [ Links ] W. Nauta, 'The implications of freedom: The changing role of land sector NGOs in transforming South Africa' (PhD thesis, Vrije Universiteit, 2001): 121-127. [ Links ]

34 Wotshela, 'Homeland consolidation': 261-308.

35 Ibid: 270-308.

36 W. Beinart and C. Murray, 'Agrarian change, population movements and land reform in the Free State', Land and Agriculture Policy Centre, Working Paper No 51 (Johannesburg: The Centre, 1996): 1-45. [ Links ]

37 Wotshela, 'Rural livelihoods':72-83. Department of Land Affairs, White Paper on South African Land Policy ( Pretoria: Government Printer, 1997): 1-25. [ Links ]

38 C. de Wet, 'Report on diagnostic Evaluation Study of Slovo Welcome Trust Farms in the Whittlesea/Queenstown area of the Eastern Cape Province', Report prepared for the L&APC and DLA, 1998: 1-20. [ Links ] L. Wotshela, 'A diagnostic Evaluation of the Gallawater A Trust - Queenstown District, Report submitted to the Steering Committee of the Eastern Cape Land Reform Programme, 1997:1-25. [ Links ]

39 Wotshela, 'Rural livelihoods': 73-84.

40 DLA, EC Land Transfer 1995 -2006. Interviews with Mr. J. Tukwayo, 13 November 1994, 14 July 2003, 12 May 2006 and 15 February 2007.

41 DLA, EC Land transfer 1995-2006.

42 Wotshela, 'Rural livelihoods': 73-84.

43 DLA, EC Land transfer 1995-2006. In this Chris Hani led with 88 000 hectares, followed by Ukhahlamba at 52 430 hectares, then by Cacadu at 41 653, Amathole at 29 718. Both O.R Tambo and Alfred Ndzo Municipalities had redistributed only just under 10 000 hectares of land in total.

44 Walker, 'Agrarian change': 44-45.