Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Kronos

versão On-line ISSN 2309-9585

versão impressa ISSN 0259-0190

Kronos vol.35 no.1 Cape Town Nov. 2009

ARTICLES

Utopia Live: singing the Mozambican struggle for national liberation1

Paolo Israel

Centre for Humanities Research, University of the Western Cape

ABSTRACT

This article engages a historical reconstruction of the formation of Makonde revolutionary singing in the process of the Mozambican liberation struggle. The history of 'Utopia live' is here entrusted to wartime genres, marked by heteroglossia and the use of metaphor, and referring to moments when the 'space of experience' and the 'horizon of expectation' of the Struggle were still filled with uncertainty and the sense of possibility. Progressively, however, singing expressions were reorganised around socialism's nodes of meaning. Ideological tropes, elaborated by Frelimo's 'courtly' composers, were appropriated in popular singing. The relations between the 'people' and their leaders were made apparent through the organization of the performance space. The main contention of the article is that unofficiality, heteroglossia, metaphor and poetic license, although they feature in genres that have been marked out as 'popular' in academic discourse, are by no means intrinsically 'popular'. Much on the contrary, they are the first victims of populist modes of political actions, that is, of a politics grounded on a concept of 'people'.

A Hummed Agreement

Joana Makai was explaining to us the transformations of Makonde2 singing traditions, as he had experienced and understood them. June's wind was blowing chilly and dry, up from the lowlands and ravines into the northerly Mozambican town of Mueda, a place spoken of far and wide as a metonym of the Struggle for National Liberation. A thin man in his mid-seventies, endowed with a precise eloquence and a pondering mind, Makai had been a practitioner of mapiko masked dancing ever since his coming of age, and was held as an authority on matters of drumming, dancing and singing. We were sitting in the sunny yard of his Muedan house, asking questions: myself and Mali Ya Mungu, friend, field-assistant and himself a mapiko dancer and singer, who helped as an interpreter when my grasp of Shimakonde would falter. Makai told us:

Long ago (kala), it was songs a bit like this... But in the middle times (pakati-pakati) it was songs where these masters (vene), there, insulted each other. Today, it's songs where we sing what happened. And things that existed, that we see with our eyes. And no insulting, but telling things, things that existed. Like these, these [things] of today.3

Makai was proposing a fairly schematic and fairly biased periodisation, where the early-colonial (kala) was left empty ('like-this'), the late-colonial (pakati-pakati) was reduced to the genre of songs of insult and provocation between rival matrilineages, and the postcolonial (nelo, ambi) was filled with the realist singing of 'things that existed'.

Reading uncertainty on my face, Mali Ya Mungu swiftly rendered in Portuguese:

These songs of today, they sing the way Frelimo's Law is (como é a lei da Frelimo). They can sing them amongst themselves, they can sing for the fame of our Party, or of our Government....

A master of the metaphor,4 Mali has his personal philosophical obsessions - Power and Law, Fame and Shame - and a self-indulgent propensity for neologisms like cadeirar ('chairing', to take hold of a political position); kulya shilambo (to eat the Nation); estar fantasiado ('to be fantasised', the hilarious condition of having drunk too much of a local brew called 'Fantasia'); and the recurrent predicative é da Lei ('it is the Law's'). Being acquainted with Mali's philosophical disposition, I was about to ask him to rephrase his translation. Makai, however, who had a grasp of Portuguese, consented to the interpreter's eccentric rendering of his own statement with a long, affirmative humming.

Popular unofficiality?

Strands of Africanist scholarship have, in the last few decades, excavated genres of African popular orality in the search for unofficial, poetic visions of history. Not only oral forms, such as songs and praise poetry, are thought to convey 'maps of experience',5 'styles of historiography'6 or 'historiologies',7 they are sometimes considered as inherently opposing dominant power, as constitutionally counter-hegemonic. Jack Mapanje, Leroy Vail and Landeg White define the essence of African orature in terms of 'poetic licence': 'the convention that poetic expression is privileged expression, the performer being free to express opinions that would otherwise be in breach of other social conventions'.8 Similarly, Karin Barber understood African popular culture as marked by unofficiality,9 and Johannes Fabian as providing fleeting 'moments of freedom' for the oppressed.10 Mikhail Bakhtin's work on the European medieval carnivalesque11 has been influential in shaping these views of African orature and popular culture.

Researching the oral traditions of the people that live in the areas where the Mozambican Liberation Struggle was mainly fought, and where Frelimo's revolutionary project was piloted - the mythic 'liberated zones' first freed from colonial rule in the northerly province of Cabo Delgado12 - one finds a somewhat different picture. Today as in the last forty years, Makonde dances of all kinds and for all occasions - from masquerade to initiation, from funeral to divertissement - showcase songs that revolve around Frelimo's political project and its founding narrative, the Liberation Struggle. These songs are often referred to as 'revolutionary songs' (dimu dya mapindushi), or 'political songs' (dimu dya shiashya), as opposed to older genres and to more mundane, playful or amorous lyrics. Related to social practices such as State rituals and dance competitions, to a wide reconfiguration of identity, and to a dialectics of generations, contemporary Makonde revolutionary singing is a form of active memory of the Struggle - of 'imparting history' (kwimyangidya) or 'intensive reminding' (kukumbuanga). However, one would look there in vain for 'lived memories' of the Struggle, for alternatives historiologies or maps of that extraordinary experience of which the Makonde were protagonists. One finds instead a recitation of trite tropes, reproducing the silhouette of the Struggle as in the official history-myth.

This article engages a historical reconstruction of the formation of Makonde 'revolutionary singing', in the process of the liberation struggle.13 We will encounter wartime genres, marked by heteroglossia and the use of metaphor, referring to moments when the 'space of experience' and the 'horizon of expectation'14 of the Struggle were still filled with uncertainty and the sense of possibility. Progressively, singing expressions were reorganised around socialism's nodes of meaning. Ideological tropes, elaborated by Frelimo's 'courtly' composers, were appropriated in popular singing. The relations between the 'people' and their leaders were made apparent by the 'enactment of power' in the organisation of the performance space.15

My main contention is that unofficiality, heteroglossia, metaphor, and poetic licence, although they feature in genres that have been marked out as 'popular' in academic discourse, are by no means intrinsically 'popular'. On the contrary, they might well be the first victims of populist modes of political actions, that is, of a politics grounded on a concept of 'people'.16

Frelimo and the people's song

Samora Machel wrote:

This poem appeared in a booklet presenting the triumphal celebration of the First National Festival of Popular Dance in 1978 - a crucial moment (probably the zenith) of Frelimo's project of transformation of 'traditional culture' into revolutionary expressions.17 Three ideological nodes define the text: the opposition between bourgeois degenerate art and the culture of the People; the romantic depiction of the latter as rooted in the everyday of agricultural labour, in sweat and seasons, and the conception of culture as instrumental in a revolutionary fight against a political Enemy. The poem subtly obliterates the distinction between description and prescription: the songs of the socialist People (o povo), of the peasants (camponeses), are what they are because all that is otherwise does not belong to the People, but to the (bourgeois) Enemy.

The silent agreement over the history of Makonde singing between Makai and Mali Ya Mungu exposes the same 'zone of indistinction'18 between the factual and the normative. Singing now 'what happened, the things that existed and that we saw with our eyes' is one and the same with 'singing Frelimo's Law [...] for the fame of the Party'. This collapsing of experience and law, ideology and intimacy, memory and memorialisation, the State and the body, is a marking feature of all Utopian, totalitarian projects, and more generally of the modern political itself.19

In Mozambique, the Utopian indistinction was condensed in the formula of the 'New Man'.20 Five hundred years of slavery and colonialism adulterated all that was good about 'traditional' African society - so the story went - bringing about an insoluble complicity between 'obscurantism' and 'oppression': hence the necessity of making a 'clean slate' of all social institutions, working to the creation of persons and mentalities revolutionary and new.21

The ideology of the New Man was Frelimo's declination of a politics of populism.22 Ernesto Laclau argues that 'the construction of the people' is the quintessential political act, and that consequently the question of populism is at the core of politics.23 A politics of populism arises when a multiplicity of singular demands are articulated in an 'equivalential chain' through an act of naming. The name that establishes a collective political identity - Laclau draws here on the Lacanian concept of the 'nodal point' or 'quilting point' (point de capiton) - is an empty signifier. 'People', 'workers', etc. are not understandable as having a substantial meaning, but simply as the signifiers that hold together a political identity. The act of 'quilting' a political identity around 'the people' creates an irremediable fracture in society. As soon as the People are named, an Enemy arises. The creation of a political identity - quilted around the naming of a People and the emergence of a fracture defining an Enemy - is eminently libidinal: the process is invested with massive psychic energies.24 The function of charismatic leadership in populism is related to this libidinal investment: the Leader is the incarnation of the empty signifier: '[...] the symbolic unification of the group around an individuality [...] is inherent to the formation of a "people".'25

And indeed, in Frelimo ideology two symbolic figures oversee the paradoxical process of creating new men out of old ones.26 The Leader, who has already undergone the transformation, attests to its possibility. The Enemy - who embodies all that is to be erased - serves as a reminder of the need for struggle, a justification for failure, and a scapegoat.27 Both the Leader and the Enemy are defined in relation to their capacity to act.28 The Leader is an allegory of perfect agency, of transparent self-mastery. The Enemy's agency is lacking (the lazy) or ill-addressed (the weaver of subterfuge).

Launched as a slogan at the onset of Independence (1975),29 the 'New Man' was given mythical consistency through historical reference to the 'Armed Struggle of National Liberation' (Luta Armada de Libertação Nacional) fought against Portuguese colonialism (1964-1974). The Struggle provided an array of significant tropes for the work of the social imagination. The Leader embodied the qualities of the heroes who fought colonialism; the Enemy those of the cowards and traitors detected and summarily dispatched by the vigilant guerrillas. Following Rancière, Benedita Basto argues, in her study of the literary formation of the Mozambican Nation, that Utopia is a desire for adequacy between discourse and a place that can be pointed: look, there.30The 'liberated zones' (zonas libertadas) were the pointed cradle of Frelimo's Utopia, where the coincidence of discourse and place was to be achieved. Forged there by the mayhem and discipline of war and by a new mode of life based on collective production, militarised settlement and modernist education, the 'vanguards of the Revolution' - soldiers, People and pupils of the liberated zones - would stand as an example for the Nation to come. If the discourse of the New Man has long been abandoned in Mozambique, the history-myth of the Struggle has continued to live a life of its own, reproduced in a variety of expressive forms across the social spectrum: literature, photography, architecture, dance, theatre, visual arts - and song.

Hush down your drums

In the apogee of Portuguese colonial rule (1930-1962),31 song and dance traditions in Northern Mozambique were complex and diverse. Drums - a 'drum' (ing'oma, ikoma, ngoma, etc.) being the widespread metonym for a songcum-dance32 genre - featured at the core of all aspects of social life, from the ritual, to the mundane and the political. Far from being spontaneously collective, most 'drums' functioned as groups, often under the patronage of an individual - wealthy, powerful or passionate. Drum groups chose their members, rehearsed, invented new songs and choreographies and engaged in extensive artistic competitions.33 The relationship of singular genres with occasions, generations, and gender was fairly liquid. Connected by centuries of exchanges and transformations and shaped by influences as vast as the Indian Ocean world, 'drumming' traditions fell into ethno-linguistic partitions, quite porous but stylistically connoted in a system of mutual recognition.34

The colonial State and its functionaries were not indifferent to the call of the drum, to its exotic and primitive appeal. 'Imperial spectacles' inevitably featured a region's most famous drums, dragged volens nolens to dance for the reign's glory.35 National and religious holidays as well as the visit of leaders and personalities became regular occasions for the performance of drums, the more so the closer colonialism's institutions of power.

Songs' poetic idioms played on a wide gamut of registers: codified ritual refrains, proverbial wisdom, elliptic and evocative couplets, self-celebratory exclamations (such as the songs of insult that Makai was referring to) and elaborated individual verse. All these could be summoned to articulate critical visions of history and society, of the kind that Jack Mapanje, Landeg White and Leroy Vail put under the aegis of an aesthetics of 'poetic licence'.36 The colonial master could barely listen to these voices. When it managed to, and found the content displeasing, the consequences could be dire.37

Nationalist unrest came to the northerly district of Cabo Delgado as the flood fills the lowland. In 1963, the leadership of the newly-founded Front for the Liberation of Mozambique (Frelimo) in Dar-es-Salaam judged that the Mueda plateau was to be the battlefield of a war waged against the Portuguese. Not only was it in the finest strategic position to support a guerrilla war backed from Tanzania, close as it was to the border, and covered in dense bush thickets. Mueda's people had shown a remarkable degree of 'nationalist consciousness', firstly in the dramatic episode of the 1960 revolt, then in transiting en masse from an 'ethnic-based' organisation to Frelimo.38 The Portuguese were equally worried about insurgency in the area, which they kept under close scrutiny. The first shot of the Liberation Struggle (1964) found most of the Makonde already dispersed in the bush, as the proverbial water in which the fish would thrive.

Drums are heard far and wide, and detectability through sound was one luxury that the 'people' supporting the war effort could not afford. In the branches and localities under Frelimo's control - precarious huts in remote lowlands, with the constant threat of incursions, and the creeping suspicion of treachery - all drums had to shut up and be vigilant, waiting for better times to come to raise their voices.

Expectations of something different from complete precariousness, though, were to be deluded soon, as it turned out that - despite all reassurances - the war was there to last:

New Maize in Old Rattles

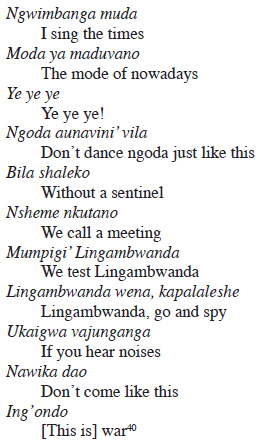

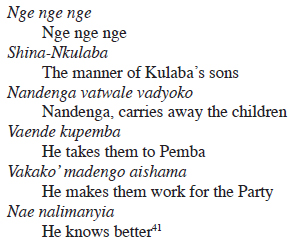

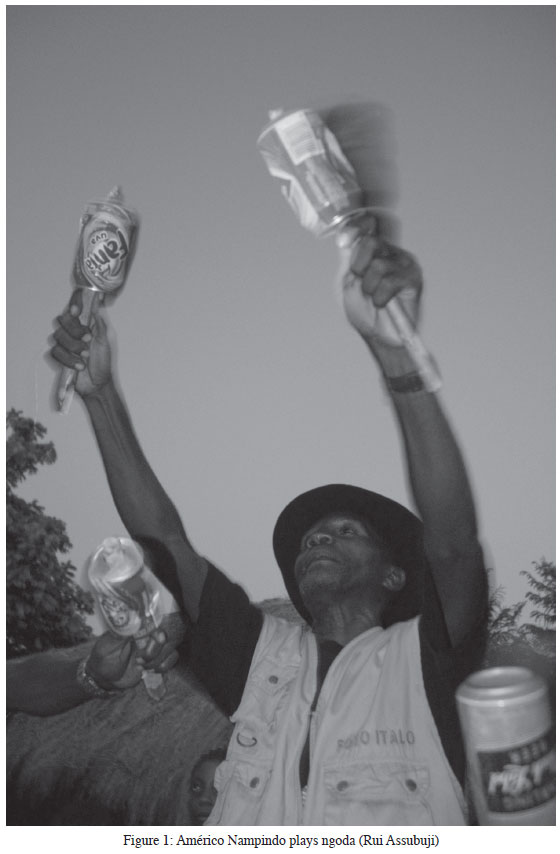

Sung to the rhythm of rattles made with used cans and filled with dried maize (ngoda, the commonest food of foot soldiers), and taking its name therefrom, ngoda was the first new drum of the war years, invented - so it is said - by the soldier Lingondo. A circular dance, it drew on the ancient and widespread drum nkala, also incorporating songs from various genres. The singing style resembled the so-called nge-nge-nge funerary singing, in which two people intone descending pentatonic scales in a sort of fugue, punctuated by euphonic syllables (nge, ndiyo).

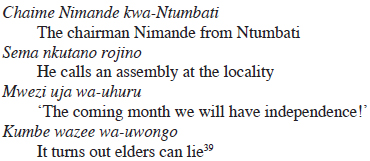

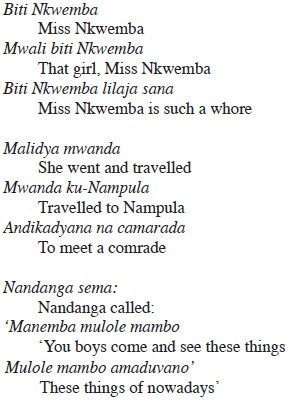

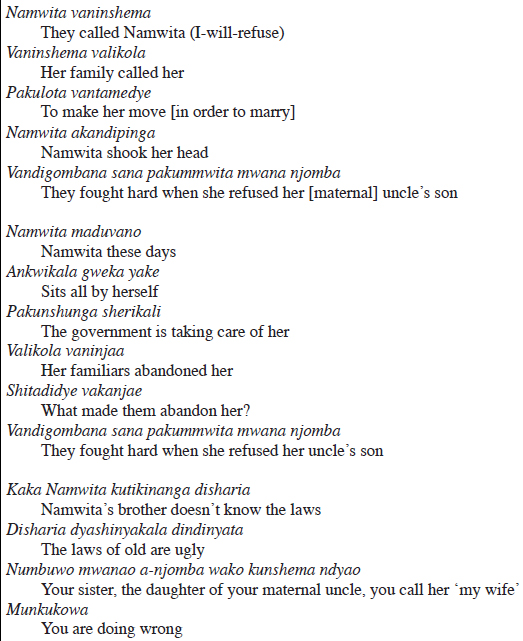

Celebrating the 'times' (muda, Kiswahili) or the 'mode' (moda, Portuguese) - the two words being made indistinguishable - of 'nowadays' (maduvano), ngoda songs fiddled with old and obscure tunes. Just one new word makes the difference:

Nandenga, the tall terrifying spirit who carries away those disoriented in the bush - a kind of Makonde bogeyman, that is - was first used as a metaphor for colonial forced cotton production. 'He makes them work the cotton (vakako' madengo ampamba)' was the first version of the song. When cotton becomes the Party, is the slippage simply incongruous or inoffensive?

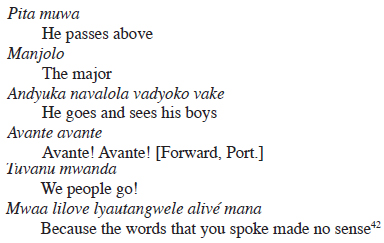

Just like Nandenga, the new characters of the transformed war landscape are fantastic apparitions on a blue sky - the Portuguese Major passes above, the guerrilla crawls below:

Amongst the small formulas (nge, njomba, mama) that embroil the main textual line, a new word slips in: the 'empty signifier' of political action: tuvenentete, we-the-People.

Anthems of Liberation

In the meantime, another new 'drum' had appeared in Mueda: likulutu, military training. Youth began to 'dance the training' (kuvina likulutu) inside the country: with wooden weapons, and obeying the cacophony of commands of trainers of various nationalities, each teaching the basic military instructors in their respective languages (Kiswahili, English, Chinese, Arabic...) Some of the guerrillas would be selected for training abroad, all transiting through Frelimo's camps in southern Tanganyika.

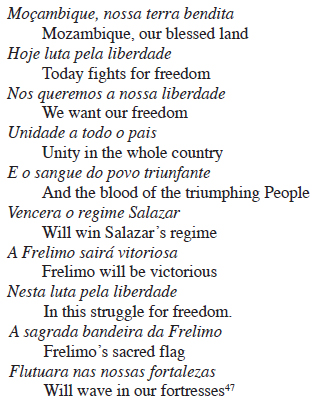

In these military spaces, musicians educated in choral singing in missions (especially the Protestant missions) put their skills to the service of the cause, composing an array of new songs for the Struggle: party anthems, marching tunes, inspirational melodies. Different to other struggle-song traditions (like the Chimurenga from Zimbabwe), local imagery and musical traditions made their way only marginally in the architecture of Frelimo anthems: in a turn of a phrase, in a peculiar rhythmic syncope, in certain melodic passages, in the structure of call and response.43 Pentatonic harmonic-melodic patterns and polyrhythm were dislodged in favour of tonal four-part harmonies and regular rhythms. The overall influence of mission imagery was considerable.

Nationalist ideology seeped through, in direct or subtle ways. Jorge Zaaqueu Nhassemu, one of the four major literate composers of Frelimo anthems,44 educated in Inhambane's missions, remembers composing his first political song, Frelimo avante na Guerra ('Frelimo, on with the War'), 'sitting under a shadow' at Kaporo, the border between Malawi and Tanzania, while waiting for his documents. Arriving in Dar-es-Salaam, the lyrics of the song had to be slightly changed to fit the ideological requirements of the movement. The war was not against the Portuguese, he was told, but against Salazar, and he should modify his lyrics accordingly. 'After that first time', Zaaqueu commented to me, 'I learned the lesson, and I didn't have to change any other song.'

Overall, the composition of anthems was part and parcel of the movement of literary effervescence that took place between Dar-es-Salaam and the war front, resulting in the publication of various gazettes and newspapers, such as 25 de Setembro, Os Heroicos, etc. More than direct control, it was a 'vocabulary of ready-made ideas'45 that shaped the consistency of the 'popular voice' of guerrillas. The proliferation of watchwords (nationalist, revolutionary) works to the utopian indistinction of things and names, with a certain suffocating effect: 'To the progressive construction of this dictionary corresponds a decrease in the publication of life stories (reports of combat, of fleeing, testimony of colonial experiences), of stories and poems. Actually, the majority of the poems were written during the first years of the Struggle.'46

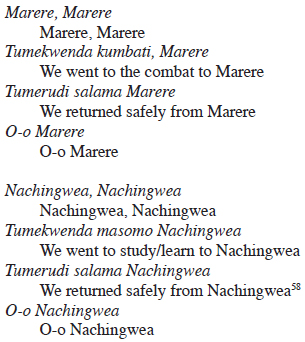

Party and military anthems, produced in a peculiar journey from the church to the camp, squarely occupy today's sound-scape of Liberation. Canções da Luta Armada de Libertação Nacional ('Songs from the War of National Liberation') is the recurring title of compilations of songs - triumphal then, nostalgic now - as well as defining the shape of an ideological programme of aural memory. From Frelimo Aina Mwisho (Frelimo is infinite) to Nelo Ni Liduva (Today is the day, mourning Josina Machel's death), from Salazar Vai Embora (Salazar go away!) to Exaltemos Mondlane (Let's exalt Mondlane): deeply inscribed in the militant's heart and soul, these melodies can be imagined as the soundtrack to the Museum of the Revolution in Maputo, accompanying, say, black-and-white clichés of Samora Machel crossing the Rovuma River in the company of the Chinese, of a youthful Mondlane watching the turbid sun as it sets over Mozambique's Liberated Zones.

Old wood for new zithers

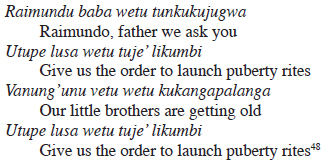

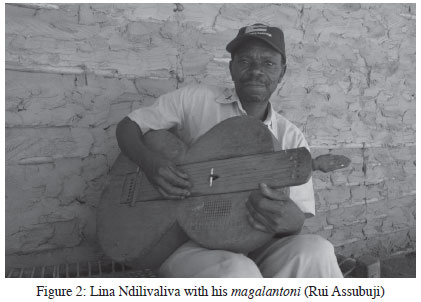

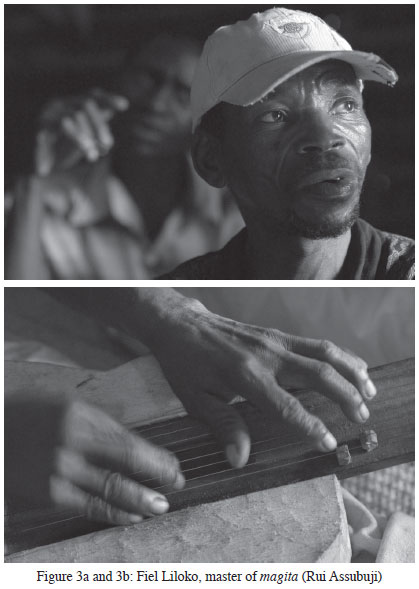

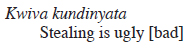

After a moment of consideration, both political and of practical opportunity, it was clear that puberty rituals were to be celebrated even in the precarious war conditions. No noisy mapiko masked dancing could mark the entrance and coming out of rituals, as it had been customary. But carving skills were put to other good uses. Adding to the traditional board-zithers ibangu49 a big resonance chamber, sculpted in the same wood that mapiko masks are made of, and one or two strings, they could be made to resemble 'real' guitars. A new fingering technique was devised in order to play on these instruments (now also called magita or magalantoni)50 the fancy rhythms from the northern coast, especially rumba, twist, and cha-cha-cha.51 Magalantoni became extremely popular in the first years of war (1964-1967), a 'must' of initiations, funeral ceremonies and all the partying permitted by the situation. Twists (matwisti) brought to athletic extremes were in the highest fashion: 'They would bend their heads backward to touch the floor... some broke their backs and died right there!' recounted magita master Samuel Mandia with a laugh.52

Despite the presence of the enemy, travelling and exchanges were as intense as ever: underground commerce, smuggling of weapons across the border, going back and forth to Tanzania for training. Displacements were not a prerogative of soldiers. 'People' when travelling had to notify the nearest Frelimo branch that could assign them to any non-strictly military task, such as the transport of war material, or delivering a message. The Magalantoni would be carried along. The fashion spread following the footsteps, creating new communities of song and new horizons of artistic fame.

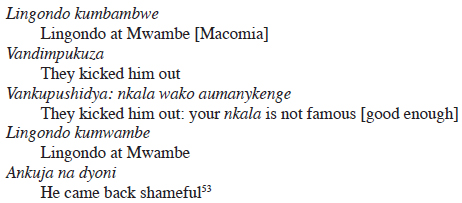

The famous Lingondo, creator of ngoda, is irreverently depicted in a matwisti as he seizes the occasion of a military displacement to exhibit his dancing prowess:

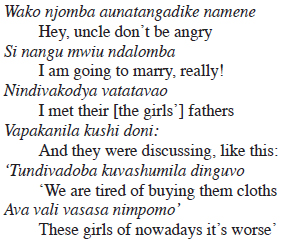

Magalantoni lyrics moved away from the obscure proverbial idioms that defined ngoda. More than any other wartime genre, they captured the war's everyday. Mixing of languages, a feature of migrant songs since late colonialism, was pervasive. The exotic word was culled, savoured and bent into the vernacular. No vocabulary of ready-made ideas here!

Instead of having the general experience of the war wrought into Frelimo's 'courtly' symbolic net, a discrete item of military life, the warehouse, the only word in Portuguese in the song, is absorbed in the vernacular, and the experience of the institution is intertwined with the soldier's ordinary:

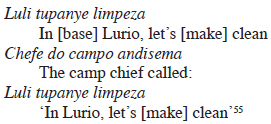

On a hypnotic and melancholic melody and a slightly syncopated rhythm, elements of daily military life revolve as if in dance. The base, the communal cleaning (limpeza, practice of the socialist life in the liberated areas), the chief, the call, the collective 'doing'. All words are foreign, but the trace of the vernacular suffuses the song - in the conjugation of a Kiswahili verb and in overall phonetic distortion - alluding to the integration of new worlds of practice and value into domains of intimacy and feeling:

Marching and miracles

As we have seen, the war was sustained by the movement of people and soldiers. Many personal stories of affiliation with Frelimo began with amazing journeys: hundreds of kilometres through thick bushes, marshes, hills and rivers, fleeing from a village and joining the guerrillas across the border. War was superimposed on the cognitive geography of Cabo Delgado, as the military partition of the province into four sectors became the common way of referring to its spaces.57 Intense movement was of course not a novelty: from ancient trade caravans to migrant labour, the history of the region was written largely by foot.

The long marches of the People carrying materials, and the complementary long marches of the leaders visiting the war zones, become the most iconic trope of the Struggle, immortalised in clichés and songs. In military anthems, displacement forebodes the encounter with death. Marching is evoked through rhythm:

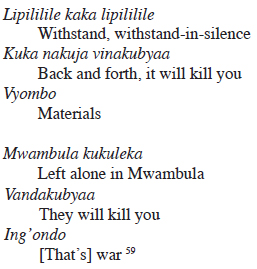

A ngoda song, on a descending pentatonic melody, conjures some of the same tropes (marching, materials, war) in the temporality of a bone-chilling vocative:

Economy, elegance and elusiveness are qualities in high esteem in Makonde orature. Things are evoked here, never said. Long marches are 'back and forth'. Materials (spelled here in the vernacular, not yet in the Portuguese 'tropified' form) and war are brought together through parallelism and assonance. The leaving behind of the foot-soldier is conjugated in an astute impersonal infinitive (kukuleka). The enemy is evoked in a slight change of a prefix in another parallelism: it is not things that kill (vi-), but people (va-). The verb kupililila (reflexive here) inscribes the suffering of War into the familiar experience of puberty rites of passage: to withstand-in-silence is what vali learn to do when faced with the painful tests of initiation. Is it so?

While the song can be understood as relating to marches and suffering, it originally referred to a woman who had many men in different places.60 The 'equipment' killing her was love rather than war-related. Men left her behind in Mwambula because of venereal diseases. Mentioning 'war' at the end of the song functioned as a reminder of the general context in which these events occurred.

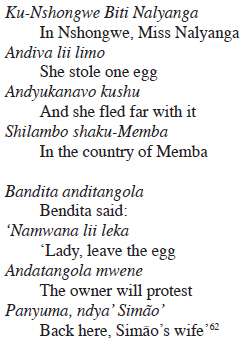

War and travelling opened up possibilities for the encounter with 'the miraculous' - in Shimakonde a common metaphor for sexual promiscuity.61 This magita song articulates the link quite explicitly:

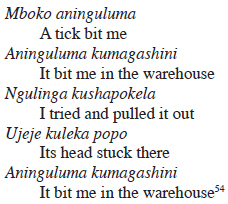

Marching went together with hunger. The restricted areas of war harvested little. Many survived off wild tubers, fruits, whatever. 'We were living of potatoes' (tushindanama mandumbwe), reminds a latter song. Hunger and walking are approached here with satire rather than lament:

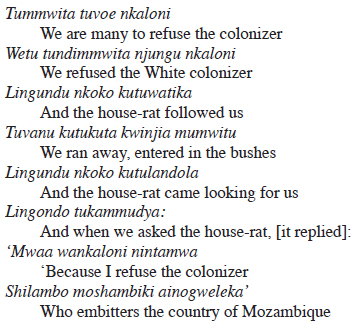

Animals also had their part in travelling. In a remote hunting field, far from all human settlements, a mysterious house-rat appears. What is it doing there? Pointing out an old witch does not seem to dispel the eeriness of the miracle (makango):

The house-rat, though, might have its own motives to follow the guerrillas deep down in the bushes, as in this widespread ngoda song:

Two Coats

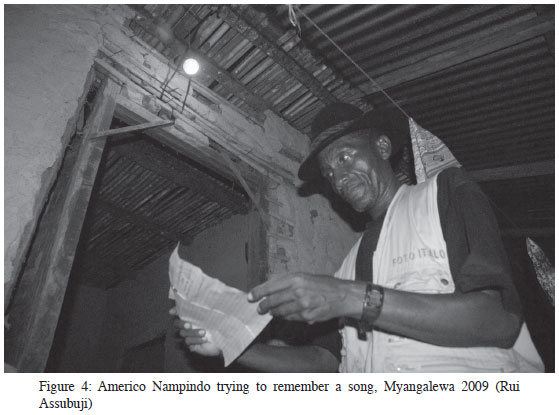

'As you know. We come back from the military base and we put on a different coat (likoti).' Americo Nampindo replied with this metaphor to my question on whether he had sung both ngoda and military anthems during the war.63

The 'coats' he referred to are the soldier's (mashudado) and the People's (venentete, povo). The two groups were involved in different activities and occupied different spaces, being subjected to differing degrees to the apparatuses of the socialist State-to-be. People carried materials64 and lived on the outskirts of the military. Soldiers were shaped by the training and education provided in camps and bases.

A partition between the two groups' cultures was put in place, which cut through the organisation of the performance space and practices of education. Soldier's anthems were performed in spaces and situations connoted with officialdom: marches, flag-raising and generally in the camps and bases. People's songs - such as ngoda or magita - were danced 'out there', in the branches and localities, in moments of informal gathering. When celebrating a recurrence, they were invited to step on the podium to represent the essence of the People under the gaze of the Leader.

Songs differed in content and form between the two groups. The heteroglossia so characteristic of migrant songs was forbidden in soldiers' songs. African languages were accepted and encouraged, but not the confusing and polysemic intermingling of languages and forms. Being 'correct' did apply to grammar, as well as to the political line.

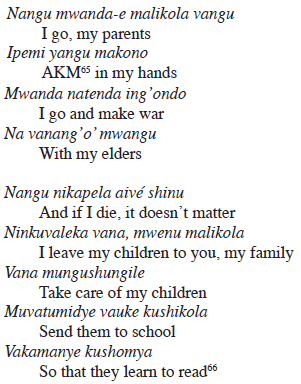

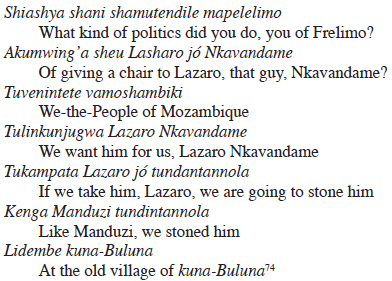

Songs could, of course, move from one space to the other. The farewell addressed to the beloved or the family was a common magita theme:

The same kind of song, stripped of all sentiment, articulated around one or two founding tropes (the People, Liberation), and rearranged by a soldier to a more martial tone, could become a semi-official anthem:

Nampindo's metaphor of the coat expresses an idea of subjectivity as an articulation of surface, which appears both in common sense, and in contemporaries theories of the subject which - taking inspiration from the philosophy of Nietzsche - refuse the idea of 'depth' or 'inwardness'.68

The question is not just one of academic blabber. A film documentary produced in South Africa, just before the 1994 elections and ominously titled 'What they sing', stirred up paranoia around the lyrics of Liberation Struggle songs.69 Calling attention to the exhortations to violence in three or four MK tunes, the anonymous voice comments: they sing 'from the depths of their hearts'.

Songs do offer easy ways into imagining collective subjects. A crowd sings a song. Is it expressing the crowd's inner essence, channelling its feelings? Is a song a minimal common denominator that fuses all the singing voices into a collective Voice? Is this not what anthropologists (and historians) presuppose when they read songs in order to construct cultures? Are songs a window into interiority? Are they really sung from the depth of one's heart? Or is song something more fleeting, an effect of surface? Do songs create a fleeting fusion between the coat and the nameless nakedness that hides behind, the illusion of depth and identity? When songs rekindle memories, do they shape the present on past emotions? Does the feeling that one pours into the songs of others testify to the human capacity for empathy and identification?

Songs articulate in a special way the ineffable with text; individuality with community; the singularity of experience with historical longue durée; memory with stimmung. The point of Nampindo's metaphor is that we do not mistake the coat for the self. And that we look at songs more as mirrors than as windows.

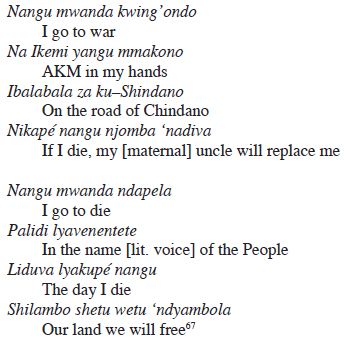

Let a song itself remind us of how easily one takes a coat for an essence. Tellingly, it is a song that was excerpted from the learning space of initiation rituals, a secret made public in uncertain times of war:

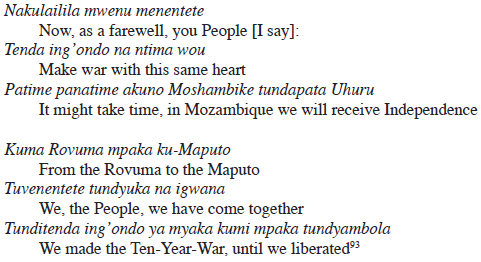

Heroism and betrayal

The year of 1968 brought crisis and upheaval in the heart of Frelimo. The facts are well known: a student revolt at the Frelimo School in Dar-es-Salaam, the assassination of Eduardo Mondlane, the death of various main guerrillas, and an internal struggle for power between two factions, leading to the crowning of Samora Machel as leader of the movement in 1970.

The interpretations of the 1968-9 crisis diverge along either side of the political divide. The open letter written by Frelimo vice-president Uria Simango (Gloomy situation in Frelimo) synthesised the core of Frelimo's moral crisis as one of summary executions. Frelimo's power clique disposed of political adversaries by stirring up crowds in the war zones, who would eagerly stone to death anyone who was pointed to as a traitor or a counter-revolutionary. Frelimo dismissed the letter as the voice of counter-revolution itself, expelled Simango and many others from the movement, and managed to crush the dissension. The crisis was then described as a fight between a conservative and a revolutionary line. For the losers, and those that would later take inspiration from them (Renamo), it was one between pluralism and totalitarianism.

It was only after this tormented transition that Frelimo openly embraced Leninism. The violent inscription of Utopia on the People living in the liberated zones also began during the crisis, and after the expulsion of Lázaro Nkavandame, former provincial governor of Cabo Delgado. As one interviewee said to historian Yusuf Adam, 'after 1968, we all became like soldiers'.71

One who is familiar with the moral geography of Makonde plateau knows the names and locations of the abandoned villages (madembe) where popular executions were carried out. They stand near to each Frelimo base, branch or settlement, as a reminder of a political process 'quilted' around the ritual killing of the Enemy.72

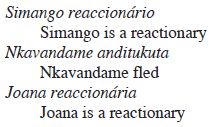

Of Frelimo Aina Mwisho, the great Frelimo anthem in Shimakonde, most party militants remember only the title line, meaning: 'Frelimo is endless'. The song, recorded by the Women's Detachment Choir, however, goes on:

The list of reactionaries continues, mentioning 18 names in the space of 3'48".

From this official version, a verse was cut that indexes the practical usages of the song:

To the rhythm of this secret verse, counter-revolutionaries and reactionaries were flogged or stoned during and after the Struggle.73

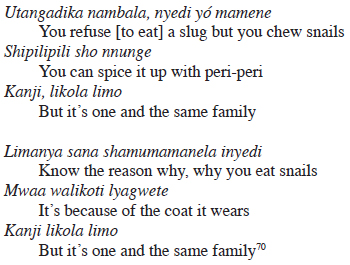

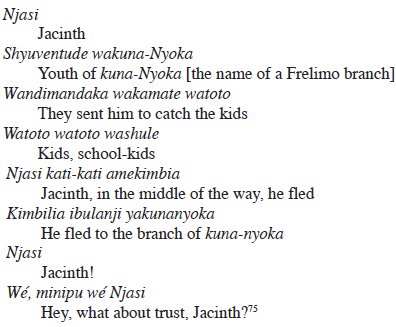

It is not with shame, but with self-confident pride, that Makonde contemporary political singing recalls these acts of popular lynching against counterrevolutionaries. A source of embarrassment for today's politicians, the abundance of these songs is like the symptom that refuses to be repressed:

When wearing 'the other coat', and certainly before 1968, people were more tolerant of small acts of treason:

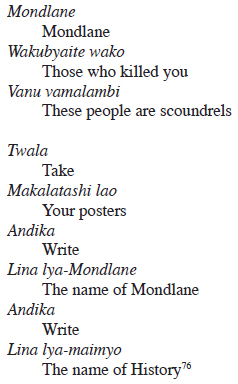

The mythology of Heroes (vanshambelo) was also reinforced after the 1969 crisis, with the many deaths of major guerrillas and of course of Eduardo Chivambo:

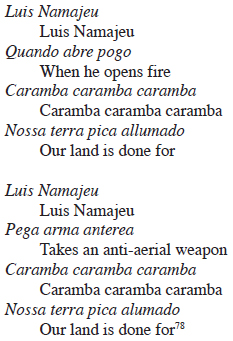

With the other coat on, the People celebrated heroism in verses less iconic and more ironic. The anti-aerial gun was the key weapon of the war in its second phase, when the Portuguese dropped bombs (sometimes napalm) from aeroplanes and helicopters. Luis Namajeu's deeds are told in a grotesquely vernacularised Portuguese:77

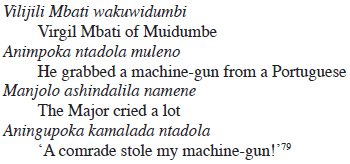

Virgilio Mbati's more modest heroism, somewhat like Jacob Zuma's, has to do with grabbing a machine gun:

Culture, a weapon of combat

Song and dance were not much on the minds of Frelimo leaders during the first years of the war. There were more urgent matters to be attended to: military organisation, setting up an educational and health network in the liberated zones, and internal conflict. After the radicalisation of 1969, culture came on the agenda, with frank Leninist connotations. A series of cultural seminars was organised between 1969 and 1973 with the objective of elaborating political directives.

Culture, that is, had to become a weapon of combat, part and parcel of Frelimo's educational system.80

The 'problem' posed by traditional African expression was understood, firstly, as one of form versus content and, secondly, as one of tribalism. From the formal point of view, singing and dancing were not only unharmful, but could be used to further military unity: 'In song and dance we solved various problems. When we sing or dance, gestures and words are uniformed. This is the question of discipline.'81 If the content of traditional dance had been irremediably corrupted by colonial capitalism, regeneration was, in due course, in the revolutionary process. The normative and the descriptive are collapsed in the Utopian indistinction: what culture must be is what it is already becoming:

At night in the liberated areas the people of the villages gather by the fire and sing and dance in complete freedom, as in the time before the arrival of the Portuguese. The old people tell the children about the crimes the Portuguese practised against the people, when they occupied that territory. They tell them about episodes in the liberation struggle, the courage of our guerrillas.82

The binaries imposed by revolutionary commitment and the doctrine of the Enemy translates into a literary project of elimination of the 'metaphorical residue' in art and literature. Thus, in a programmatic Frelimo text on poetry, Craveirinha's poem 'Eu sou carvão' ('I am coal') becomes true (in a materialistic dialectical sense) only when the figural language is converted into reality by warfare: 'the words become true in a literal sense: the African has become the fire which is burning his former master. There is no metaphorical residue left between the fire of poetry and the fire of the grenades and mortars used against the enemy.'83

The acceptance of each morsel of 'cultural practice' into the Nation was conditioned to the negation of its particularistic character:

Today a new culture is being developed based on traditional forms with a new content dictated by our new reality. [...] Culture plays an important role in the reinforcement of national unity. The dances which are performed today in the liberated regions are no longer dances of Cabo Delgado, or Tete or Niassa. The militants from other regions there bring their way of living, their dances, their songs, and from this a new culture, national in its form and revolutionary in content, is born.84

The 'liberated regions' function here as a fantasy-screen alluding to popular spontaneity. Actually, the experiment of fusing together various 'popular dances' to build a national identity was planned and piloted in Frelimo's military bases, and especially at the central training camp in Tanzania, Nachingwea. The new regenerated dances (with revolutionary content and open ethnic participation) were showcased in the famous 'concerts' that were held at Nachingwea every Saturday afternoon; or on national holidays at the bases in Mozambique, where under certain precautions, drums could be struck at their full power. 'Popular dances' were thus inscribed into ceremonials of power, inspired by fascist-Leninist spectacles,85 and not very different from their colonial counterparts. Their spatial and temporal organisation represented the new political order: the Leader's speech, the military parade, and on the podium the People's culture.

Choirs and guitar groups were the favoured musical expressions of soldiers, presented on Nachingwea's stage side by side with 'popular dances'. Partly drawing from the experience of the magalantoni, that many soldiers had sung when wearing 'the other coat', guitar groups were musically influenced by Tanzanian and Congolese styles (rumba and jazz). In their youth, influential Frelimo leaders took part in these guitars bands.

The lyrics, however, were written 'respecting the watchwords of the party. We were doing propaganda and political work, presenting the correct revolutionary line.'

'And you didn't sing love songs?'

'Ah, that thing of nakupenda nakupenda (I love you), that was there... there with the People. They sang it. We sang serious, revolutionary songs.'86

Nakupenda

'Love poems without an explicit revolutionary content are condemnable,' one of Frelimo's first documents on culture bluntly stated.87

But people - as I came to know - sang about love, at least when they had the right coat on.

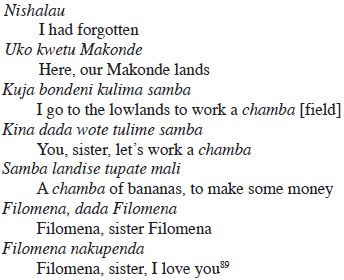

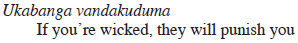

Distance and death rhyme with desire, as we all know. All wars have had their tunes of desperate affection. Leaving home exposes one to loss, forgetfulness, betrayal:

The influence of foreign urban music and its languages was important in the upsurge of this wartime sentimentalism. Not by chance, desire was spelled in (vernacularised) Kiswahili:

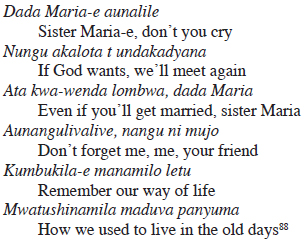

Not only is the soldier worried about leaving behind a wife to the seductions of his friends. War sucks up the better years of one's life, those blessed with fecundity. The lack of means does not enable one to satisfy the desires of modern girls:

Love invaded wartime songs, not only because of distance and fashion. Frelimo aimed at the radical transformation of gender and power relationships. The law of socialism had to substitute for custom. Affection was an angle to discuss these new forms of 'moral subjectivation':90 the shaping of a relationship between an individual and the Law, the interiorisation of a norm into one's daily practice.

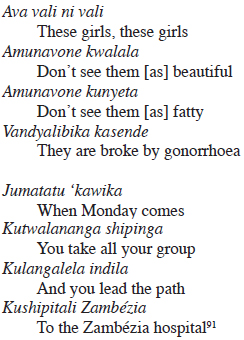

The war brought changes in gender relations that had little to do with socialism's intended effects. When moral subjectivation goes all wrong, when appearances betray the eye and the heart, when the weekly routine starts with the wrong foot, the exotic names of socialism's institutions turn into sites of shame and exposure:

Was Frelimo's prohibition of love songs just expressing the critique of bourgeois subjectivity (a pointless exercise in rural Mozambique, one must note)? Or was it suggesting that real true passions were to be devoted solely to the cause of the People: love the Leader and hate the Enemy?

Ariaga and teleology

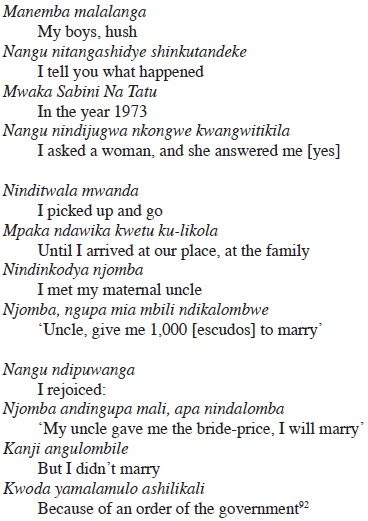

The Struggle had two major, long lasting ideological legacies. One, as we have seen, is the idea of 'the People'. The second was a concept of teleology. Based on a secularisation of Judeo-Christian time, a teleological reading of history is at the core of what we call modernity. It is also a central concept of revolution, where victory and socialism are synonymous and inevitable. This concept of history as a meaningful and progressive order was absent from Makonde singing (and cosmology) before 1960.

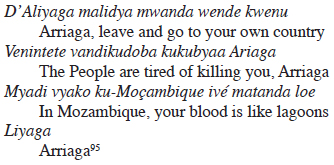

The dramatic events of 1971 provided a tangible ground for a vision of victorious teleology. In that year, the Portuguese struck back at Frelimo with an operation that was intended to wipe out the military bases of the movement, and bring all 'natives' back under control. Code-named 'Gordian Knot' (Nó Górdio), the operation set out to 'comb the bushes' with might and violence, accompanied by propaganda falling from the skies and filling the ether.94 General Kaulza de Arriaga, who had learnt his lessons in Vietnam, was in command. Gordian Knot brought sufferings and disruption. Chains of command were broken. Bases abandoned. Guerrilla groups hit independently, with the only objective of surviving and bringing losses to the enemy. Lament and menace seemed the appropriate voice:

Gordian Knot turned out to be a disaster. The expenditure on the operation was huge. Frelimo resisted. Arriaga went back with his tail between his legs. This defeat of the colonial army was the first major readable sign of a historical teleology, and the symbolic matrix of all successes to come. The inevitable victory of the future resembles the victory already harvested in the past:

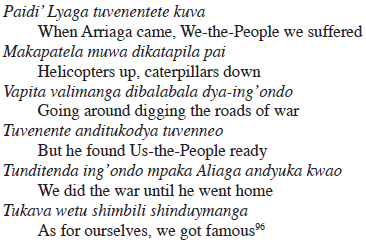

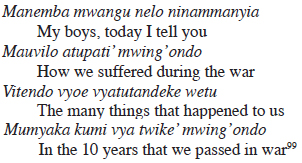

War was no longer the setting for topical singing. Struggle became the subject matter of historically oriented compositions, called 'songs of reminding' (dimu dya kwimyangidya). The verb 'kwimya' means (something like) 'to tell a story in order to remember it'. Its durative-causative form 'kwimyangidya'97 thus means: 'to remind (intensively, repeatedly) a history that should be remembered'. Maimyo, a noun derived from kwimya, is usually simply translated as 'history', but conveys the same notion of 'history to be reminded'. 'History' (maimyo), that is, celebrating/reminding the deeds of the Struggle, was to constitute the new thematic core of Makonde political singing.

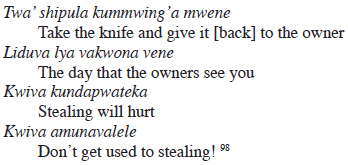

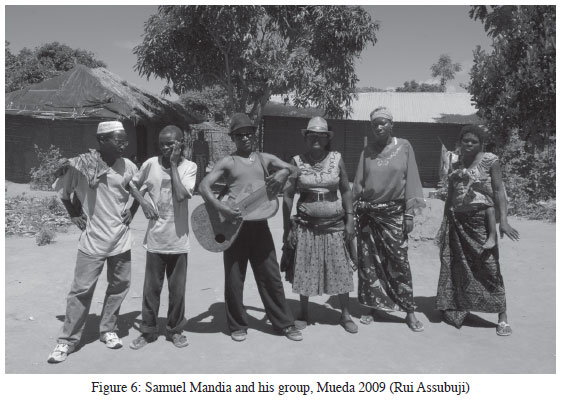

After the successful resistance to Gordian Knot, Frelimo tightened its grip over the liberated zones. The Portuguese seemed weaker, the guerrillas stronger, and the helicopters farther away. The veil of silence over drums was finally lifted. Dances came back to Makonde country with their intrinsic loudness. The two 'drums' that had protagonised the years of silence - ngoda-rattles and magitazithers - were replaced with powered versions. Ngoda was transformed into limbondo, a drummed circular dance where people dress in tatters, wear animal-fur backpacks and violently shake axes or scythes. Although some of the old songs 'transited' into the new versions, most of those that referred to the experience of the war were abandoned. Morality was a thread that passed onto limbondo:

Zithers such as magita and magalantoni were all but abandoned. Many people went on to play home-made electric guitars (also called magita). People's groups imitated the 'correct' political style of soldiers, while also continuing to sing love songs. Their 'history' sometimes sounded empty:

A few masters of the zither, such as Samuel Mandia and Fiel Liloko, continued to cultivate the instrument after 1971, and eventually after Independence. The wartime songs that they recalled for me, and that play the lion's part in this piece - good music that you, reader, are unable to listen to, and this paper, alas, was unable to sing - were already a foregone repertoire in 1974. Liloko turned then to 'songs of reminding'. Mandia devised a way to play a genre of social critique (called bwarabwà) on the zither, for which he is known today. The old wartime tunes were not requested or appreciated anymore, although one or two could occasionally be slipped in during a performance. Of all the 'drums' that resounded with renewed vigour in the liberated zones, two especially carried the flag of 'revolution', and broadcast the new idiom of political singing: mapiko masquerades (particularly of the kind practised by the generation that made the war) and the militarised dance nnonje.

Tropes of utopia

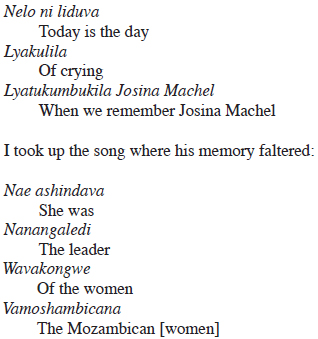

In the attempt to locate a Shimakonde speaker in the Cape Town migrant underworld, I was faced with a striking instance of the power of song. One candidate, a young man, was introduced to me. Walking and chatting around the streets of Observatory, he told me his story. He was born in Mozambique, but his family had fled the country during the civil war and took refuge in Tanzania. His linguistic competence in Shimakonde was consequently very basic. I was unable to employ him. 'Why are you looking for a Makonde, anyway?' he asked me. 'To help me translate songs. There are many words that I don't know.' 'Aah! Songs...', he said 'like', and started humming:

I took up the song where his memory faltered:

'How do you know it?' he asked me. 'This is a song that I was taught in the secrets of initiation, there in Tanzania...'

After Gordian Knot, 'cultural activities' increasingly took place in the schools, on the model of those organised in the military camps. Pupils would learn choral songs mostly, and a few selected popular dances. As Frelimo educational centres (centros pilotos) were placed in the proximity of a military base, to defend the children from possible incursions, school pupils grew up with soldiers, and were subjected to military rules, routines and ceremonials. Choral songs were taken only partly from the military repertoire: a whole range of educational songs were composed to instil revolutionary values, historical memory and political consciousness. The texts were structured around a trite recitation of ideological formulas, dates, and names of heroes and leaders.

In the final years of the war (possibly 1973), the dance makwaela became the elective cultural activity for pupils in Frelimo schools. This is a southern Mozambican variant of a region-wide modality of choral singing, makwaya (from the English 'choir'), where European four-part harmony is fused with local musical practices such as 'responsorial organisation, dense overlapping, and variation of individual parts [...], more relaxed vocal timbres, a more spontaneous approach to vocal exclamations and other sounds.'100 Its origins in migrant labour (especially from southern Mozambique to South Africa) gave it the right credentials for a revolutionary dance. Simple and rhythmical, it appeared ideal for schools and ideological work. In the years after independence makwaela become the national school-dance, and one of the major forms of transmission of the Party's slogans. Hundreds of tapes of makwaela songs were recorded in the Frelimo pilot schools in a national campaign between 1976 and 1978.

Makwaela also became the main form of dance taught to Makonde boys and girls at initiation rituals, and the one that they would present to the village at the initiates' coming-out. The slogans and formulas of the Party were considered to be the central values instilled in the men- and women-to-be:101

Pier Paolo Pasolini, elaborating on a much older construct of romantic philology, uses the metaphor of falling down (precipitare) to describe the movement of descent of aesthetic forms from courtly poetry into popular oral poetry - the verticality of the metaphor indexes relations of power.103 Pasolini shows how figures of style and consolidated literary formulas elaborated by courtly poets (especially in Sicily in the thirteenth century) were appropriated by the popular poets in the form of fragments, endowed with a certain stiffness and resilience, like foreign bodies captured in a process of mineral sedimentation. There, they would thrive and survive for centuries, protected by the courtly aura embedded in their formal composition. Similarly, ideological formulas elaborated in Frelimo's 'courtly' music, composed under direct ideological control, 'fell' or 'trickled down' into the popular dances that were enlisted in the project of the Nation, in the form of fragments, and into the texture of consolidated forms of composition. And there they stuck, as ready-made tropes of a new stereotyped vocabulary.

Domination (kutawala), servitude (utumwa), colonial taxes (ukoti), forced labour (shibalo), the lamentation (tundipata tabu), the ten years (myaka kumi) of war (ing'ondo), the carrying of military materials (materiale, Pt.), the leaders (machepi), the organisation (kupangana), understanding (igwana), unity (upamo), the long walking (kuwena shilo na mui), the blood spilled (myadi), the geographical metonym of national unity (kuma Rovuma mpaka ku-Maputo), the quasi-messianic expectation (patime panatime), the roads (ibalabala), heart/courage (ntima), the invocations to the leaders (mwenu manang'olo), perseverance (kukanyilidya), the Party (ishama), the rejoicing (kupuwa), the expelling of the colonialists (kuusha), the recitation of dates (italee) ... And of course We-the-People (tuvenentete)104, revolution (mapindushi), independence (Uhuru), and liberation (kwambola).105

Fanon arranges in a (dialectical) scale the forms of anti-colonial and nationalist literature, from the inarticulate 'lament', to the politically conscious 'protest', to the 'watchword', informed by the nationalist ideology of the Liberation Party.106 When watchwords from Frelimo courtly literature began to trickle down into Makonde orature, articulate expressions of political 'protest' disappeared therefrom. Lament itself was produced as a codified trope. Kulila kwatulila - we cry and we cry - for colonialism, oppression, the deaths of leaders (and more recently for absolute poverty, AIDS, etc.). Metaphor, irony and complexity were the victims of this process of tropification. Song production in Shimakonde - the one that Makai was describing - registers a sharp, almost quantitative decrease of rhetorical strategies such as metaphor, ellipsis and idiophones in coincidence with the peak of Frelimo's Utopian project, and in the genres that were mostly involved in the Struggle, and a sudden reappearance of these linguistic devices in subsequent genres.

From a rhythmical point of view, nationalised 'popular dances' often maintained the aspect that they had before the Revolution. Visual imagery referring to the Party was massively introduced: flags, images, tissues and masks depicting leaders, weapons such as AKM, grenades, bazookas ...107 A number of genres were most neatly identified with nationalism and the Party, and benefited from increased prestige and popularity. Other genres of dances and songs simply disappeared as they did not conform to the ideological requirements of the Party. This is the case with the 'songs of provocations' that Makai refers to as the songs of 'middle-times' (roughly, late colonialism), where dance groups of different lineages exalted and insulted each other, often resulting in violent confrontations. Far from being the predominant genre of the late-colonial Makonde song production, these songs found their raison d'être in the schismogenetic logic of precolonial Makonde segmentary society, embedded in the disruptive networks of the slave trade. When the Party explicitly prohibited them as a form of 'tribalism', they swiftly vanished, only to resurface years later as electoral songs in the times of the multi-party system.108

Revolution and popular culture

The New Man - the perfect coincidence between place and discourse, the transformation of the 'people' into the People - was an unachieved and unachieavable project. What the Liberation Struggle did achieve, with regard to Makonde drumming expressions, was to absorb them into a hierarchical ideological space, marked by a specific organisation of the performance space, and sustained by coercive forms of power.

The endeavour of 'extracting the People from the people' needs an elite who guarantees the transformation,110 produces the discourse defining what belongs to the People and what does not, and wields the means to repress or annihilate what falls in the latter group. 'Popular culture' is the result of this operation: the violent positioning of a set of cultural idioms into a hierarchical space of elite vs. people, where the former draw their legitimacy on possessing the key to what the latter is (the elites are elites because they know what the People are/will be, and because they can shape it into form, like a tree, by cutting useless branches). Frelimo's elites did not just claim the privilege of interpreting 'popular discourse', as all forms of populism (or anti-populism, for that matter) do.111 They defined the very conditions of its existence and visibility. On the podium of the 1978 Festival, as previously in Nachingwea and elevated to the dignity of symbols of the Nation by a complacent elite, were danced the 'popular expressions' that conformed to the vision of the Revolution produced by the elites themselves.

Gramsci defined 'popular culture' (folklore) as embedded in a structure of class, articulated around a 'common sense', mostly religious, and characterised by the incorporation of scientific discourse produced by the elites in the form of fragment.112 Similarly, the idiom of 'Makonde revolutionary singing' (dimu dya mapindushi) coalesced like a clastic rock around inert fragments of Frelimo's discourse of scientific socialism: watchwords, dates, events, names, actions, tropes. The temporality of teleology (the vanquished past as the matrix for the future to come) was the major compositional mode adopted from Frelimo's 'courtly' productions.

The fragments of Frelimo's 'dictionary of ready-made ideas' took such an authoritative position not simply because of coercion, but by way of a collective libidinal investment in the project of the People. This amounted, in Mueda, to taking up the name that one has been given, to assuming onto oneself the prestigious myth-history of the Struggle. We-the-people (tuvenentete) and 'the liberators' (tundyambola) are the subjects responding to this interpellation. Taking up new songs of 'reminding' (kwinyangidya) and forgetting old wartime genres was part of the response.

The absorption of Makonde singing into the hierarchical ideological space of 'popular culture'; the 'trickling down' of the formulas of socialism in the form of inert fragments, leading to the ossification of metaphor and the tropification of living memory; the investment of libidinal energies in the signifier of 'the People', and its ideological nodes, the Leader and the Enemy: these are the provisional conclusions of this study on the historical formation of the idiom of Makonde revolutionary singing.

Today, fragments of Frelimo's dictionary float freely in Makonde orature, disconnected from the political process in which they were once powerfully meaningful. Although the reduction of metaphor was one of the declared aims of Frelimo's monologic populism, new and different genres keep emerging in Makonde orature, besides and beyond 'revolutionary songs'. Poetic licence still cracks up spaces between words and things; irony and the carnivalesque work out their parts. Masters of metaphor continue to be born.

PAOLO ISRAEL is a post-doctoral fellow at the Centre for Humanities Research, University of the Western Cape. He has worked and published on Makonde mapiko masquerades; rumour, withcraft and political identity in northern Mozambique; and orality and linguistic anthropology.

1 A first version of this article was presented at the workshop 'War and the Everyday', organised by Patricia Hayes and Heidi Grunebaum at the Centre for Humanities Research, University of the Western Cape, on 27 October 2008. A second version was presented at the Anthropology seminar at the University of the Witwatersrand, on the 10 September 2009. I thank Neo Muyanga, Andrew Bank, and Marie-Aude Fouere for their comments; Premesh Lalu for fostering my research in the Programme for the Study of the Humanities in Africa; Estevão Jaime Mpalume and Marcelino Ding'ano for their support in Pemba; Angelina Januário and Fidel Mbalale for help with transcriptions; Rui Assubuji for his photographs; and Jung Ran Forte for her ongoing engagement.

2 I use throughout the paper 'Makonde'not as an ethnonym, but as the name of a language (Shimakonde). So, 'Makonde songs'is a shortcut for 'songs in Shimakonde', and 'Makonde people' a shortcut for Shimakonde-speaking people - although, of course here language and identity complement themselves.

3 Joana Makai (Mueda: recorded interview, June 2003). My translation from Shimakonde. One of the anonymous reviewers of this article has asked that I mark out more explicitly my translation strategies. I will not be able to satisfy this demand in this piece, essentially for reasons of space. Some linguistic notes will provide clues for those interested in this aspect. I am also busy preparing a collection of songs in which I try and do justice to their subtleties. The transcription of the original texts in Shimakonde - carried out with all the philological rigour that I could summon - can also provide interesting clues to those who read related regional languages such as Yao, Nyanja, Swahili, Chewa, Shona.

4 'The greatest thing by far is to be a master of metaphor. It is the one thing that cannot be learnt from others; and it is also a sign of genius, since a good metaphor implies an intuitive perception of the similarity in dissimilars', Aristotle, Poetics, 1459 a 5-8, [ Links ] cited in P. Ricur, The Rule of Metaphor (London & New York, Routledge, 2003): viii. [ Links ]

5 L. Vail & L. White, Power and the Praise Poem. Southern African Voices in History (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1991): 40-83, 198-230. [ Links ]

6 D. Coplan, 'History is eaten whole: Consuming tropes in Basotho auriture', History and Theory, 32,4: 80-104, [ Links ] and In The Times of Cannibals (Johannesburg: Witwatersrand University Press, 1994). [ Links ]

7 J. Fabian, Remembering the Present : Painting and Popular History in Zaire (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1996): 269 and following. [ Links ]

8 Vail & White, Power and the Praise Poem: 319.

9 K. Barber, 'Popular arts in Africa', African Studies Review, 30, 3 (Sep 1987) and 'Introduction', [ Links ] Readings in African Popular Culture, (London: The International African Institute, 1997): 1-12. [ Links ]

10 J. Fabian, Moments of Freedom : Anthropology and Popular Culture (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1998). [ Links ]

11 M. Bakhtin, Rabelais and his World (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1984). [ Links ]

12 Once a district of the Mozambican Colony, Cabo Delgado is now the northernmost of Mozambique's twelve provinces, bordering with Tanzania on the north and with the Indian Ocean to the East, and situated at about 2,500 km from the capital, Maputo.

13 In this article I present mostly songs that were performed during the war of liberation, from a corpus of around 150 songs. I draw comparative insights from an overall corpus of over a thousand songs in Shimakonde and kiswahili. I have recorded live performances in Cabo Delgado (districts of Muidumbe, Mueda, Nangade, Macomia, Mocimboa da Praia and in the city of Pemba), and retrieved songs at the archives of Radio Moçambique, Maputo and Pemba; ARPAC (Arquivos do Património Histórico e Cultural), Maputo, Pemba, Chimoio; audio-visual archives of the Companhia Nacional de Canto e Dança, Maputo.

14 See R. Koselleck, Futures Past: On the Semantics of Historical Time (Columbia University Press, 2004). [ Links ]

15 N. wa Thiong'o, 'Enactments of power: The politics of the performance space', TDR, 41, 3 (Autumn, 1997): 11-30. [ Links ]

16 It can also be argued that the marking of certain genres as 'popular' in academic discourse is based on the same operation that defines a populist politics. This argument - that I defend elsewhere - is outside of the purview of the present article.

17 Programa do Primeiro Festival de Dança Popular (Maputo: Gabinete do Primeiro Festival de Dança Popular, 1979).

18 The expression is Giorgio Agamben's, Homo Sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare Life (California: Stanford University Press, 1998): 4 and passim. [ Links ]

19 One could argue, the other way round, that political modernity has fabricated the short-lived illusion of the separation between the private and the public, the body and the political, captured by the elusive idea of the 'civil society' - an illusion dramatically dispelled not only by totalitarianism, but by the biopolitical turn in contemporary democracies.

20 'It is not difficult to see how all radical revolutionary projects, Khmer Rouge included, rely on this same fantasy of a radical annihilation of tradition and of the creation ex nihilo of a new (sublime) Man, delivered from the corruption of previous history', S. Žižek, For They Know Not What They Do: Enjoyment As a Political Factor (London: Verso, 1991, 2008 2nd ed.): 261. [ Links ]

21 'The question is, for the comrades of Utopia, of making a blank slate of the past, of de-traditionalising colonialism and de-colonizing tradition', C. Serra, Novos Combates pela Mentalidade Sociologica (Maputo: Livrária Universitária, 1997 Futures Past): 97, [ Links ] my translation.

22 The understanding of Frelimo's politics as one of populism was the major insight of Christian Geffray's path-breaking (and misunderstood) research on the roots of the Mozambican civil war, see C. Geffray, La Cause des Armes au Mozambique: Anthropologie d'une guerre civile (Paris: Karthala, 1990), [ Links ] and also 'Fragments d'un discours du pouvoir (1975-1985)', Politique Africaine, 29 (1988): 71-85. [ Links ]

23 E. Laclau. Critique of Populist Reason (London: Verso, 2005). [ Links ]

24 Laclau, here follows Freud in postulating that 'the social bond is a libidinal one', Critique: x. He also draws on Slavoj Žižek's early work on the libidinal dynamics of totalitarianism, see The Sublime Object of Ideology (London: Verso, 1989). [ Links ]

25 Laclau, Critique: 100.

26 See 'How to extract the People from within the people', in Žižek, For They Know Not: 261-263. [ Links ]

27 For Claude Lefort the Enemy in totalitarian political systems is understood as a sickness in the 'political body'. See, 'The Image of the body and totalitarianism', in The Political Forms of Modern Society (London: Polity Press, 1986):292-306. [ Links ]

28 For agency as the core 'imaginary structure' of nationalism, see P. Lalu, The Deaths of Hintsa: Postapartheid South Africa and the Shape of Recurring Pasts (Cape Town: HSRC Press, 2008):16-18, 219-222. [ Links ]

29 The founding text is considered S. Vieira, 'O homem novo é um processo', Tempo (1978): 398, 27-38. [ Links ]

30 Basto, A Guerra das Escritas. Literatura, Nação e Teoria Pós-Colonial em Moçambique (Lisboa: Vendaval, 2006): 65. [ Links ] This is based on a reading of J. Rancière, Courts Voyages au Pays du Peuple (Paris: Seuil, 1990). [ Links ]

31 The northern parts of Mozambique were administered by chartered companies until the late 1920s. In Mozambican historiography, the end of charters and the campaign of forced cotton production (1938) promoted by Salazar are taken as watersheds of a new era of colonial domination, which extended until the formation of Frelimo in 1962. See for instance, aa. vv., História de Moçambique, vol II. Moçambique no áuge do colonialismo, 1930-1961 2 ed. (Maputo: Livraria Universitária, 1999). [ Links ]

32 The two go together. A 'drum' is called a 'drum' event when it features no drumming: for instance when singing is accompanied by rattles or other musical instruments. Often the name 'drum' refers also to initiation.

33 There is a wide literature on competitive dance in East Africa, from Terence Ranger's classic study to more recent appraisals. For an overview, see F. D. Gunderson and G F. Barz, eds, Mashindano!: Competitive Music Performance in East Africa (Dar-Es-Salaam, Mkuki na Nyota, 2000); [ Links ] and R. K. Gearheart 'Ngoma memories: A history of competitive music and dance performance on the Kenya coast' Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, University of Florida, 1998. [ Links ]

34 For instance, the Mapiko masquerades that so closely define the ethnic identity of the Makonde were widely taught to Makua people in the forties and fifties, especially in the area of the Messalo River.

35 See A. Apter, 'On imperial spectacle. The dialectics of seeing in colonial Nigeria', Comparative Studies in Society and History, 44 (Jul 2002): 564-596. [ Links ] For a philosophical exploration of the connection between power and its ceremonial apparatus, see G. Agamben, Il Regno e la Gloria: Per Una Genealogia Teologica dell'Economia e del Governo (Firenze:Neri Pozza, 2007). [ Links ]

36 Vail & White, Power and the Praise Poem: 319.

37 Thus, in 1961 Paulo Juankali from Shitunda, one of the great masters of song of Mapiko masquerades, was arrested because a sipaio could understand his complex narrative referring to the Mueda massacre and nationalist ferment.

38 For the engagement of the Makonde with Frelimo, see amongst others Y. Adam, 'Mueda, 1917-1990: Resistência, colonialismo, libertação e desenvolvimento', Arquivo, Boletim do Arquivo Histórico de Moçambique, 14 (1993): 4-102, [ Links ] and M. Cahen 'The Mueda case and Maconde political ethnicity: Some notes on a work in progress', Africana Studia, 2, (1999): 29-46. [ Links ]

39 Magita song, Samuel Mandia (Mueda: recording session, July 2008). 'This chairman really existed', recounted Samuel Mandia, laughing. 'He used to chair the branch of Ntumbati. And he would do meetings and tell us that the Portuguese would soon surrender and concede independence'.

40 Ngoda song, Americo Nampindo's group, (Myangalewa: recording session, September 2004).

41 Ngoda song (Nampanya: recording sessions, December 2004 and April 2009).

42 Ngoda song (Namakule: recording session, January 2005).

43 For a comparative glance, see A. J. C. Pongweni. 'The Chimurenga songs of the Zimbabwean war of liberation', in K. Barber, ed., Readings in African Popular Culture (Indiana University Press, 1997): 63-72, esp. 66, [ Links ] T. Turino Nationalists, Cosmopolitans and Popular Music in Zimbabwe (Chicago University Press, 2000), [ Links ] D. Coplan and B. Jules-Rosette '"Nkosi Sikelel' iAfrika": Stories of an African anthem' in Composing Apartheid. Music for and Against Apartheid, G. Olwage ed. (Wits University Press, 2008), [ Links ] Bringman, Inge. 'Singing In the bush. MPLA songs during the war for independence in south-east Angola (1966-1975), (Köln : Rüdiger Köppe, 2001) and the motion picture Amandla!: A Revolution in Four-Part Harmony (Lions Gate Film, [ Links ] 2002). [ Links ]

44 The three others were Simão Tiburcio Lindalandolo, Calisto Mijigo and Abílio Filipe Awendila. They had passed away at the time of my fieldwork (2002 on). I interviewed Zaaqueu in February 2005 in his house in Pemba. Recordings of his songs are kept at the ARPAC in Maputo. Zaaqueu is also the author of collections of poems. Another important literate composer that I worked with in Pemba is Manuel Gondola, with whom I had the privilege of playing in a short-lived band (2002).

45 'Dicionário de ideias feitas', in Basto, A Guerra das Escritas: 176-185. [ Links ]

46 A Guerra das Escritas: 185.

47 This is Zaaqueu's. He sang it for me, but the song is well known and it appeared in booklets and collections.

48 Magita song, Samuel Mandia (Mueda: recording session, 2008). 'Raimundo' refers to Pashinuapa, an important Makonde Frelimo leader.

49 This is the local name of a musical instrument played in East Africa, especially in Tanzania (kipango), Mozambique (also bangu, bancu, iwaya, etc.) and Malawi (bangwe), that ethnomusicologists call 'board-zither'. It is made of a wooden board, on which a long wire is stretched, in such a way as to produce five, six or seven strings. It is strummed or fingered. The instrument underwent a major 'modernisation' on a regional scale already in the late 40s, when many musicians adopted playing styles inspired by guitars. See G. Kubik, 'Neo-traditional popular music in Africa since 1945', Popular Music, 1 (1981): 83-104. [ Links ] The American 'banjo' (or at least its name) could be a descendent of this instrument.

50 A Kenyan genealogy has been suggested for the latter name.

51 See the photograph in Kubick 'Neo-traditional': 88.

52 Samuel Mandia (Mueda, recording session, January 2005). During this recording session with Samuel Mandia, probably the greatest master of magita, I learned for the first time about the existence of the magita wartime genre. After playing a couple of more recent songs, he came up with one or two oldies. He then told me that they were part of a genre sung during the war, which no one would play anymore. I was later able to locate four more performers of magita songs: two that I actually pursued (in Shinda and Litembo), and two that I met by chance (in Mapate and Nshinga). Many told me that they had played the instrument, but had then forgotten everything.

53 Samuel Mandia, ibid.

54 Samuel Mandia, recording session (Mueda, July 2008).

55 Samuel Mandia, ibid.

56 Fiel Liloko (Shinda: recording session, August 2008).

57 The first sector ran from the Rovuma to the Mueda-Mocimboa road; the second until the Messalo river; the third until Montepuez; the fourth up to the Lurio River.

58 Studying is as dangerous an activity as combat. The relationship between the two - the question of students going to the front, and the politicisation of education - were harshly debated during of the 1968-9 crisis (see further).

59 Ngoda (Nampanya: recording session, December 2004).

60 So the authors explained to me during an interview (Nampanya, March 2009). I wrote the commentary to the song before that, and I believe it still stands. This testifies to the potential polysemy of the song.

61 Kulava, a miracle; kulavalava, having many lovers.

62 Samuel Mandia, ibid.

63 A. Nampindo (Myangalewa: interview, April 2009).

64 People were often defined metonymically as 'carriers of material' (vamateriali).

65 The Kalashnikov AK49.

66 Magita song, Fiel Liloko (Shinda: recording session, August 2008).

67 Magita song, Samuel Mandia (Mueda: recording session, January 2005).

68 See C. Taylor, Sources of the Self: The Making of the Modern Identity (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989): 111-199. [ Links ]

69 South Africa's political space in relation to liberation struggle songs seems to be partitioned between paranoia and nostalgia. The case of umshini wam ('bring me my machine gun'), the struggle-song deployed as an anthem by president Jacob Zuma and later by xenophobic crowds, is a case in point. Critics of Zuma have seen the song (and its subsequent usage) as a menacing symptom of latent violence. Supporters understand the song as a reference to the noble history of the Struggle. See L. Gunner, 'Jacob Zuma, the social body and the unruly power of song', African Affairs, 108 (430), 2009: 27-48. [ Links ]

70 Magita song, Fiel Liloko (Nshinda: recording session, August 2008). Incidentally, this song that I recorded and offered to the provincial station of Radio Mozambique was a (local) hit. It presented its audience with a groove - that of wartime magita - that sounded fresh because it had been forgotten.

71 Y. Adam, 'Mueda, 1917: Resistência, colonialismo, libertação e desenvolvimento', Arquivo. Boletim do Arquivo Histórico de Moçambique, 14 (1993): 51. [ Links ]

72 I have elaborated this point in my 'The war of lions: Witch-hunts, occult idioms and post-socialism in Northern Mozambique', Journal of Southern African Studies, (March 2009), 35 (1): 155-174. [ Links ]

73 It also appears that both Nkavandame and Simango were burned alive to the sound of the song, in a Frelimo re-education camp.

74 Mapiko song, Nandindi group (Mwambula: recording session, March 2005). Nkavandame had long been dead when the song was composed. Mandusi, a local sipaio, was stoned in 1974 near the village of Miteda, and thence stood as the epitomic figure of popular lynching. Kuna-Buluna was one of the madembe were people would be killed.

75 Magita song, Samuel Mandia (Mueda: recording session, January 2005).

76 Mapiko song, Omba (Mueda: live recording, June 2003).

77 The singers were of course conscious of the grotesqueness, of the vernacularisation, and of the fun. Some of them were reticent of singing these old songs in bad Portuguese - but all found them amusing.

78 Magita song, Samuel Mandia (Mueda: recording session, January 2005).

79 Magita song, Trovingi Rosario (Nshinga: recording session, August 2004).

80 I ground my reconstruction of FRELIMO's ideology and policies on education and culture on Basto, A Guerra da Escritas, C. Siliya Ensaio sobre a cultura em Moçambique (Maputo: CEGRAF 1996), [ Links ] M. B. Gomes, Educação Moçambicana. História de Um Processo. 1962-1984 (Maputo: Livraria Universitária da UEM, 1999), [ Links ] B. Mazula Educação, Cultura e Ideologia em Moçambique 1975-1985 (Porto: Afrontamento, 1995), [ Links ] on a number of Frelimo programmatic documents from 1971-1983 and on a few interviews conducted with grassroots implementers of Frelimo's cultural policies in Pemba and Muidumbe. For more detail on documents and interviews, see my doctoral dissertation, 'Masques en transformation: Les performances mapiko des Makonde (Mozambique). Historicité, création et revolution' (Paris: EHESS, 2008): 298-299, 496. [ Links ]

81 Documento final do 1º Seminário Cultural. See also Basto A Guerra: 128-129.

82 Message from the Central Committee to the Mozambican People', Mozambique Revolution, spec. no. (Sep 25, 1967): 5. [ Links ]

83 'The role of poetry in the Mozambican revolution', in Mozambique Revolution 38 (March-April 1969): 17. [ Links ] Basto analyses this text as Frelimo's foundational statement in production of a literary canon, A Guerra: 68-92. I am largely indebted to her insightful reading.

84 'Shaping the political line', Mozambique Revolution, 51 (April-June 1972): 22. [ Links ] The title of the section is 'mental scars'.

85 Mussolini and Lenin exerted a reciprocal influence in inventing the modern spectacle of mass power, constructed around the military parade, the synchronic performances of the new social organisations (fascist youth, etc.), the speech of the Leader, and the showcasing of symbols of 'popular authenticity' (peasant women, dances, etc.). See, amongst others, S. Falasca Zamponi, Fascist Spectacle: The Aesthetics of Power in Mussolini's Italy (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997). [ Links ]Spectacles of mass power had a specific fortune and vernacularisation in Africa.

86 Manuel Gondola (Pemba: interview, April 2009).

87 Documento final do 1º Seminário Cultural, reunido de 30 de Dezembro de 1971 a 21 de Janeiro de 1972 (photocopy), see also Basto, A Guerra: 130, and 'What is the Mozambican Culture', in Mozambique Revolution 50 (January-March 1972): 50. [ Links ]

88 Magita song, Fiel Liloko (Shinda: recording session, August 2008).

89 Ngoda song, Samuel Mandia (Mueda: recording session, January 2009).

90 M. Foucault L'Histoire de la Sexualité II: L'Usage des Plaisirs (Paris: Gallimard, 1984): 33-45. [ Links ]

91 Samuel Mandia, (Mueda: recording session July 2008).

92 Magita song, Fiel Liloko (Shinda: recording session, August 2009).

93 Fiel Liloko, (Shinda recording session: Moçimboa da Praia, January 2008).

94 See H. G. West, Kupilikula. Governance and the Invisible Realm in Mozambique (Chicaco: University of Chicago Press, 2005): 145-147. [ Links ]

95 Ngoda song, Americo Nampindo (Myangalewa: recording session, August 2004).

96 Magita song, Fiel Liloko (Shinda: recording session, August 2008).

97 Formed by the apposition of a durative verbal extension [-ang-] and a causative [-dya-].

98 Limbondo song, Cinco Ramos (Mapate: recording session, July 2004).

99 Magita song, Muidumbe Jazz (Mwambula: recording session, April 2009).

100 T. Turino, Nationalists, 125.