Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Kronos

On-line version ISSN 2309-9585

Print version ISSN 0259-0190

Kronos vol.34 n.1 Cape Town Nov. 2008

ARTICLES

Prompting reflections: an account of the Sunday Times heritage project from the perspective of an insider historian

Cynthia Kros

Wits School of Arts, University of the Witwatersrand

Introduction

The article that follows is about a memorial project: the Sunday Times Heritage Project to be precise.1 It is not quintessentially about memorials, although while writing it I have taken a detour to reflect on how certain memorials have tempted me beyond the boundaries of a narrow academic precinct. These memorials exhibit every sign of becoming the kind of unstable memorials that feature in James Young's biography, capable of 'generating' an unpredictable range of meanings in dialogue with their visitors.2 Perhaps I should register less surprise that the article has taken such a turn since I embarked on it in order to raise further questions about the historian's responsibility out in the world, already complicated by Ciraj Rassool's observations of academics interacting with other participants in the making of the District Six Museum.3 Commenting on the challenges that are directed at the academy's procedures and 'hierarchy' on independent sites of 'engagement', Rassool concludes teasingly that the outcome is a 'productive ambivalence about academic forms of knowledge appropriation'.4

Recently, by contrast, Christopher Saunders has warned historians to be on the lookout for sloppy or cavalier heritage practitioners. Although he offers a slight subsequent modification, his essential concern is to advocate that: 'It is the duty of historians to judge heritage critically, and to point to its inadequacies and failings.'5 Saunders attributes the newer exhibitions created in the District Six Museum to the intervention of academic historians responding to critiques centred on the original Museum's partial and romanticised depictions of life in the old District.6 He is less impressed by the intervention of the academic historian in the scripting of the Apartheid Museum, pointing to the glaring omission of Helen Suzman in its portrayal of opposition and resistance. On the whole, however, Saunders draws a very clear dichotomy between the partial and self-interested use of the past practised by those in the heritage camp, and the academic historian's more holistic and 'critical' (read dispassionate) engagement with it.

Saunders, I would argue, is attempting to reassert what he sees as the dissipating authority of the academic historian beset by history's declining prestige within the academy and opportunistic raiders of the past on the outside. Rassool, on the other hand, appears to welcome what he characterises as practices and forms of knowledge that are potentially subversive of those venerated by the academic hierarchy, whose rigorous observance, in turn, keeps the hierarchy incontestably intact. It will shortly become clear that I lean towards Rassool's approach without quite being able to forfeit some of the historian's privileges.

How far to go?

It has been some years now since Keith Jenkins took E.H. Carr's philosophy of history by the scruff of its neck and forced it to the logical conclusions that Carr himself had not been quite able to stomach.7 Back in the 1960s, through his famous set of lectures on the nature of history, Carr made a significant impact on the profession through his incisive, but ultimately - as Jenkins would argue - pusillanimous demonstration that 'facts' have very little autonomous existence beyond the historian. Jenkins maintains that Carr was not able to follow his argument through by accepting that the past is essentially inaccessible to historians and available only through the selective remnants of evidence that have survived. Even if Carr - through his disclosure that the middle class white male historian's perspective is as partial as any other - did introduce qualifications limiting the impact of his central argument, several well-known practising historians have acknowledged their debt to him for allowing them to find their own voices and routes into areas of history that would previously have been ruled out of bounds.8 The kind of indignant responses with which Jenkins's work three decades later was greeted by some established historians who reiterated their professional immunity from bias, suggested that his ruder exposure of the historian's positionality was experienced by these critics as a cruel blow. Jenkins shows that the claim to objectivity, particularly through his deft demolition of the 'middle point' argument, is always untenable but also that it what it attempts to do is to render the historian's version impervious to the observation that his history proceeds from a perspective usually entrenched in dominant gender, class and race ideology.

Saunders's concern about historical accuracy is not entirely misplaced. One would not want the women of 1956 converging on the Union Buildings to protest against the extension of passes to African women to be composing songs against Vorster rather than Strijdom, as may have happened in the project that is the subject of the paper that follows.9 It also proved illuminating to know why, in another instance, the government could not tolerate the continued presence of the Israelites at Ntabelanga, which led to the fatal standoff with police recalled as the 'Bulhoek Massacre'. Historians are trained to be particular about periodisation and the importance of contextualisation, as Saunders suggests. Equipped with even these two prerequisites of their craft they are able to read more into the archive in a productive sense than the untrained investigator, especially under the kind of time pressure that the relentlessly journalistic deadlines of the Sunday Times project imposed. But, of course, periodisation itself is not a neutral exercise and neither is contextualisation.

While working on the project I was led to wonder about the different ways in which scholars from different disciplines might characterise the segregationist or apartheid city which formed the backdrop for the events and people commemorated by many of the memorials. My curiosity was especially piqued after reading Lilian Ngoyi's letters in the light of literary scholar Daymond's evocation of the 'Shadow City' to which Ngoyi was consigned, and which cast its deformed shadows on almost every pale blue page of her letters.10 We might argue confidently that understanding what it meant to be banned in one's personal capacity in the 1960s and '70's would give historians an advantage over other kinds of researchers and writers when they come across the poignant letters of Lilian Ngoyi written within the confines of what she tirelessly reiterated as her 'tiny matchbox' house. Similarly the researcher might understand the kind of township Orlando was then and how it reflected the government's vision for Africans in urban areas, and would know something about the general historical experiences she had traversed from her impoverished childhood through her time in Solly Sachs' Garment Workers' Union. On the basis of this kind of background knowledge historians might be able to make reasonable surmises about what certain abbreviated phrases meant, or what aspects of the Soweto Uprising it was possible for Ngoyi to have glimpsed from the yard of her house which made their searing way into her letters, or which European tour she was recalling years later for her correspondent and its significance in the context of African National Congress (ANC) politics in the 1950s.

Clearly, however, as Daymond's paper illustrates, we would be losing something if we closed off other ways of seeing Ngoyi's battle to break out of the confines of the phantom city into the 'real' one. This last is not only a reference to the 'white' city from which she was effectively barred, but also to a full political and social life whose extinction she perpetually lamented. Increasingly urban scholars summon the city as 'social fact' rather than 'physical form' as Body-Gendrot and Beauregard observe.11 They also describe an increasing tendency on the part of their colleagues to 'wander across disciplines in search of compelling explanations and even (to) entertain multiple interpretations'. They continue thus: 'Ambiguity and complexity take the place of grand theory's traditional infatuation with the formal, the unequivocal and the parsimonious'.12 Bickford-Smith begins an argument for 'cross-disciplinary' studies to strengthen 'urban historiography', although, it may turn out that 'ambiguity' and 'complexity' are not lacking in the best of the historical urban studies.13 There does seem, though to be a case for even more 'wandering' across disciplinary boundaries and shaking off the empiricist dust.14

It would be an interesting experiment to see what different kinds of professional researchers or the relatives and friends who knew Ngoyi could find in what must first be understood as the extremely limited space of Ngoyi's dearly budgeted aerogrammes. Would the constant references to the fortunes of the garden of her matchbox house be read as reflecting obsessive preoccupation with the mundane produced by a decade and a half of virtual house arrest or as a minute point of colour and relief? Might the garden be deciphered as code? Over the course of the letters to Belinda Allan, the correspondent from Amnesty International assigned to Ngoyi's case, it becomes a claustrophobic metaphor for domestic imprisonment. But it has many emblematic overtones. In its moments of neglect and decay, as Ngoyi more or less tell us, it embodies perceived maternal failure.15 In its best seasons it might be a subtle declaration of the dependence of the South African liberation struggle on continued support from abroad since it was grown from seeds sent by Allan. Accompanying Ngoyi's warm declarations of intimacy with the Allan family were the endless necessary statements of financial need and tactful requests for more money since Ngoyi was living in abject poverty because of the limitations imposed on her by the punitive South African state. Ngoyi with her talent for words and her famous inclination for metaphor could not have been unaware of how much the paragraph on the state of her garden that was almost an invariable element of every letter she wrote to Allan was capable of communicating to a sensitive correspondent. Of course there is also the point suggested by Daymond that the very act of growing a garden in the township, which with every facet of its existence tried to drive out acts of individual creativity, was a miracle. Ngoyi's perpetual mentioning of her garden was an act of resistance, perhaps intended to gall the censor or alternatively to elude him.16

In a memorialising project that is principally based on individuals, deliberately cast on a small, human level as is the Sunday Times one, it is important to accumulate telling detail in an attempt to expose the texture of the subject's life. A considered analysis of Ngoyi's literary deployment of her garden (and the other tropes in her letters) brings out her canny way with prose; her ability to chronicle the minutiae as well as the horrific ruptures of life under house arrest in Soweto and her perpetual low-level anguish. It may be that we have caught Lilian Ngoyi at the wrong angle. Her friends and relatives, including her adoptive daughter, are reportedly pleased by the way the Sunday Times has chosen to honour her, but still they may not read her letters in the same way we have.17 The point, I think, is to extend the available archive and to encourage many different readings of it. I have visualised them stretching out as the hinterland of the memorials that are, by and large, themselves abstract rather than literal, and suggestive rather than dogmatic.18 It is useful in this light to ask how the historian's interpretation might broaden or alternatively check the metaphorical flowering of Ngoyi's garden. It is hard to be absolutely categorical in one's answers.

Professional authority?

Working as one of the historians on the Sunday Times project has certainly sharpened this author's awareness of how easy it is to reach for the generic narrative and to fall back on the axiomatic authority of the academic historian. Of course there is no such beast as 'the historian'. I should really qualify that description by saying of myself that I am a historian trained in a largely social history tradition who, by the time I was engaged in this project, was about to leave an academic history department for the heritage programme in the School of Arts. By the 'generic narrative' I mean principally the one constructed by the 'revisionist' school, and by 'axiomatic authority' I mean that confidence to believe that I was right which is derived from having a fluent and largely uncontested historical narrative to hand. I would argue, as I have suggested above, that sometimes it is useful and even necessary to be able to check grossly inaccurate statements, for example those concerning who was in power when. I have also begun to suggest above, I do not endorse Saunders's call for absolute vigilance and an unchecked exercise of professional authority over other kinds of understanding and reflection. I particularly want to argue that what Alex King called, in a different context, the 'lack of resolution in the meaning' of some of the memorials that were created by the artists, opened the way for a multiplicity of interpretations that might not meet with Saunders's approval.19 This is what I take to be a variation on Rassool's 'productive ambivalence', although he is referring to epistemological issues more closely connected with debates about memory and oral testimony than I am in this case (see above).

Some of Saunders's insistence on the prescriptive role of historians in heritage projects no doubt has its origins in his general pessimism induced by what he sees as the tendency of history to drift off course in the latter days, and his sense that historians, particularly certain kinds of historians, are being dismissed as irrelevant.20 When the historical establishment gets together it tends to lament its perceived fall from favour. About half of the authors in the collection edited by Stolten in which Saunders's chapters appear occupy professorial positions and a healthy proportion is at the level of senior lecturer or above. These historians grumble about how they and their fellows have either been distracted or disqualified from providing the staple narrative for the new nation. They blame an inhospitable political and economic climate for sidelining or trivialising, or even obliterating, their discipline. Sometimes they contradict themselves, bemoaning the lack of new recruits on the one hand, and warning against the dangers of fragmentation and dilution by allowing too many voices to speak out, on the other.21 Catherine Burns in the same collection strikes a refreshingly different note. She points, albeit in a somewhat unflattering metaphor, to the almost incessant but frequently unobtrusive activities of particular historians who rarely find themselves idle or barred from what she sketches as an arachnid micro-economy connected by silken threads to wider networks.22 She has these historians momentarily appearing and then disappearing back into the crevices of their rock face, like scuttling spiders. The implication is that they are not only well adapted to a fairly furtive existence, but surely also that they are adept at spinning stories and creating webs. I am not sure how far Burns intends us to take the metaphor, but it is richly suggestive. I am trying, for the duration of this paper, to constitute myself as one of Burns' spiders, and to reflect on what happens on my scuttling expeditions between the exposed site of the Sunday Times project which I am shortly to describe, and my refuge in the rock face.

The Sunday Times Heritage Project

Academic training in the sardonic school of social history may give the commentary that follows a hard edge, which does some injustice to the originality and power of the vision behind the project, which has produced some very fine and inspiring memorials, as I will endeavour to show. A further caveat is that I was only one member of a fairly large and disparate team of people who rarely met face to face.23 My job on the project was to collate archival material (certainly not restricted to the Sunday Times) suitable for History teachers in the Further Education and Training phase for the Sunday Times heritage web-site that appears now, unfortunately with some errors which I hasten to disclaim, under the link 'In the Classroom'.24 The Sunday Times team worked in conjunction with the South African History Archive (SAHA) directed by Piers Pigou currently based at Wits University for the archival aspects of the project.

The Sunday Times introduces what was apparently its editor's idea on the occasion of the newspaper's centenary in 2006 of sponsoring a series of 'public story memorials to some of the remarkable people and events that made our news century'. 'We wanted to show that today's news is tomorrow's history', he maintained. Most historians would have no trouble in identifying the number of constructions, including that of the concept 'century' in the first sentence. The second, in its representation of painless transmutation from news into history, is slightly provoking. The introduction continues: 'We wanted to tell stories that would inspire us to think in fresh, imaginative ways about our past, shared and separate, painful and proud'. It is clear that these stories would have a mission, mostly dedicated to capturing the imperatives of the post-1994 narrative in alliterative couplets - 'shared and separate' and 'painful and proud'.25 But this compressed introduction probably does not do justice to the project as it unfolded.

An overview of the project declares that: 'We wanted to add a valuable stitch to the fabric of our streets and communities', and continues, '[o]ur national story "trail" starts in Johannesburg, where the Sunday Times began in 1906. 10 artists were commissioned to interpret 10 remarkable moments in our past that have helped to make us who we are now'. The idea of the fabric (probably Charlotte Bauer's who was the Director of the project) assumes that it is already largely stitched together.26 There are no troubling irruptions in the fabric - although, in fact, elsewhere she does ponder over some of the instances where consensus among numerous 'stakeholders' proved to be limited, and she owns to a journalistic impatience with the long haul required to follow through with the requisite processes of consultation and obtaining permission from the relevant authorities.27 The idea of the national story 'trail' is presented here as a journey of discovery to full nationhood, no doubt drawing on the hegemonic post -'94 discourse. We later learn that the aim of the project is: 'To inspire us to think about our diverse past in new, imaginative ways', and ' [t]o unlock memory - collective, local personal - and give it a home in the present through public "story art" which stirs curiosity, emotion and pride in a burgeoning national identity'. All the repositories of memory are enumerated here as if they were able to exist independently of one another, a notion of which Halbwachs in his famous analysis of 'collective memory' firmly disabused us a long time ago.28 'We believe these 'story sites' will add a valuable stitch to the fabric of their immediate surroundings and communities, animating the past in ways we can make sense of now', it continues.29

A reading of the Sunday Times project and its memorials is necessarily informed by the literature on successive 'memory booms' over the twentieth century; their origins and trajectories, from the first which sought to give meaning to a generation lost in the Great War, to a subsequent 'boom', taking off falteringly in the late 1940s, then rising to a crescendo, sometimes fortified by the politics of Zionism to bear witness to absolute evil; to others that have tried to recuperate national, or increasingly, ethnic pride through summoning a sense of the past as shared.30 It is helpful in evaluating its genre connections to hold the Sunday Times heritage project up against the critical historiography of memorialisation, as well as the literature proposing a self-conscious civil society that has flourished largely in response to Habermas' delineation of a historical 'public sphere' around forty years ago.31

The newspaper (especially this newspaper one might argue) calls forth its public through storytelling, disclosure and revelation.32 It frequently does so, on the scale of the individual, often against the backdrop of current affairs, even when the ostensible environment is domestic. In its bid for survival and uptake the newspaper story typically compels the extrusion of the private into the public. The detritus that is invariably expelled would probably exacerbate Habermas' already deeply felt pessimism about the degradation of the public sphere that he thought had occurred by the 1960s since its emergence a couple of centuries before.33 But there is every sense in the editorial pages, and even on the front pages that, for example, famously denounced the mendacious and kleptomaniacal disposition of the Health Minister last year (2007), that the Sunday Times sees itself both as 'moral witness' and as responsible for creating and sustaining a 'moral community' in the sense that Winter has explored them.34 Charlotte Bauer herself downplays the newspaper's possible claim on historical morality, noting that, although its slogan is 'The paper for the people', 'the people' who it addresses have changed significantly over the years.35 She might have been favourably surprised by the editorial written towards the end of 1968 on the occasion of the revelation of the South African government's machinations behind the exclusion of 'coloured' cricketer, Basil D'Oliveira, from the English side due to tour South Africa. The editor of the Sunday Times at that time was extremely outspoken in his condemnation of Vorster's actions and in his prediction that South Africa as a whole would pay the price for its prime minister's paranoid racism.36

Perhaps we should not get into convoluted appraisals of past editorial policy and its reception, but rather stick with present editor, Mondli Makhanya's Sunday Times and with the argument that it thinks of itself (with all due qualifications about its heterogeneity and several glaring contradictions) as a 'moral witness'. This raises a series of questions about how the newspaper conceives of its obligations to the public, the kind of vocabulary with which it seeks to address the 'nation', and the nature of the 'truth' it attempts to purvey.

As Winter has pointed out, through exploring the work and convictions of those who survived the First World War and later those of the Nazi genocide, and who later chose to bear 'witness' to their horrors in a deliberately clinical and unadorned style, 'moral witnesses' - at their most extreme those who believe that they were spared to tell an indifferent world about the cruelties that befell them - are unshakably of the opinion that the power of their stories to do good lies in their incontestable truth. These 'moral witnesses' are vehemently opposed to what they see as romanticism or fallacious morality in fictionalised or secondary accounts or even in those of their fellow survivors who seem prepared to betray their former selves who endured the real awfulness of the events for later material or political gain. 'Moral witnesses' rail against decorative language, heroic redemption or spiritual resolutions because they all appear to compromise the truth that must endlessly be told. In bearing witness against evil only the bare and unalterable truth stands the least chance of making an impression on a sceptical or uninterested audience. Of course, as Winter argues, these blinkered truth claims are deeply problematic. He encapsulates the problem as a paradox that lies in the witnesses' claim for objectivity arising out of the absolute faith they have in their subjectivity.

As the Mbeki regime in South Africa shrank, not only from the spotlight but also from public accountability, the general boast was made from certain newspaper columnists and their supporters that there are those among them who are unafraid to 'speak truth to power'. Makhanya himself uses this phrase in lamenting Director General in the Presidency, Frank Chikane's, apparent loss of integrity under the baleful influence of the president.37 Perhaps we should not forget that this is the discursive environment in which we were working. So we might ask: how much are we all bound by the idea that we should serve as 'moral witnesses' to the horrors of racial oppression and to the bravery of those individuals who resisted it, and, further, that we may be required to keep faith with those heroes of the past by speaking out against a newer regime that certainly acted in some instances with notable callousness? How does this sense of moral duty work with or against a willingness to allow for irresolution and democratic processes of making meaning? I am not sure of the answer yet. I do think that nearly all of us believed we were calling a 'moral community' into life in some way.

Swimming through history

When editor of the Sunday Times, Mondli Makhanya, talks about the stories that are all around us, portraying the newspaper plucking them from the atmosphere as it were, it is reminiscent of Hobsbawm's evocation of the past as the natural and inescapable environment through which we 'swim...as fish do in water'.38 Hobsbawm argues that all human beings are not only conscious of, but perpetually situate themselves in relation to their past if only by rejecting it.39 These ideas have resurfaced to some extent in the Desire Lines collection discussed below. The past, Hobsbawm argues, perhaps with the kind of unshakeable faith he was heir to as a Marxist historian, is a permanent dimension of human consciousness and an ineluctable component of social institutions and values.40 Hobsbawm's is a beautifully rich evocation of the past which he renders as democratically accessible in a way that contrasts quite sharply with Saunders's implicit claim on the past as the prerogative of academic historians. But Hobsbawm is as judgmental as the latter when he considers the potential the past has for mischievous manipulation by the aspirant ruling class. He makes a rough division between the 'formalised' or conscious past which people accede to or even actively seek out for various reasons, and the less conscious past that sustains social life in a much less visible, but presumably no less necessary way.41 In the first category, he indicts the 'bourgeois parvenus (who) seek pedigrees, new nations or movements (that) annex examples of past greatness and achievement to their history'.42 In South Africa we can think of several imperialist memorials or heritage projects, even now, that are seizing new territories of the past to authorise the ideas or to legitimise the political position of those whom Hobsbawm could name fearlessly as 'bourgeois parvenus'.

There is an enviable ease about the way in which Hobsbawm could chart what happened to history in the hands of the new, rising middle class, showing it congealing into rhetorical 'inspiration', 'ideology' and then, finally, 'self-justifying myth'.43 He observed that the latter becomes a 'dangerous blindfold'.44 His prescription for the historian's intervention was not achieved quite as effortlessly as the diagnosis of what happened when history fell into the wrong hands and was used to fortify the position of the new ruling class. But, essentially, he thought it was the historian's duty to remove the 'blindfolds', which he would accomplish through observing rigorous historical procedures.

The present author has inherited more than a grain of the Marxist obligation to help society understand itself better, and a great deal of respect for the work of Hobsbawm. It seems, nevertheless, so much harder for us than it was for him to see what the historian should do to contest the new state's 'annexation' of history that justifies the particular concentrations of power and certain patterns of redistribution, which favour elites over the masses in whose name they allegedly struggled. Saunders's critique (see above), except for the brief discussions of District Six and the Apartheid Museum which have been alluded to, is mostly about the manipulation of heritage by the state and state funded bodies and agencies.45 It is in this context that he establishes the necessity for the historian to act as adjudicator and to strike down inaccuracies. For him, as we have seen, the historian is able to cast a wide ranging gaze back across the past and to be more or less impartial in assessing it. But Saunders's historian appears to be apolitical and is seemingly never engaged in any contest except against the unprofessional use of history. Hobsbawm's appeal to historians is different in that it urges them to take a combative position against the ruling class and its self-perpetuating mythology in order to expose it for what it really is in the cause of social progress.

In the post-Marxist phase, and when as photographer David Goldblatt has noted, the left wing artist's search for a subject and position in post-apartheid South Africa is complicated by the disappearance of the 'clearly identifiable enemy', the task of 'speaking truth to power' is immeasurably complicated. 'There is a vastly complex social reality in which it is not easy to formulate a critical sensibility' Goldblatt writes.46 Historians who think of themselves as being on the left at work now in South Africa must own to a similar dilemma.

The Sunday Times project instructed us to find stories scattered across the landscape. In fact, many of them, although certainly not all, end up connecting with the larger story of the ANC and it is surprising how easily that generic narrative which I have mentioned at the outset comes to hand. It is as if, after almost forty years of radical social history and fourteen years of formal freedom from the National Party's Afrikaner driven history, the template is effortlessly transmitted to those of us who attempt public history after having come through a particular training and set of experiences. The generic narrative, since it is one of sacrifice and the long struggle to overcome adversity through virtuous perseverance, tends to make martyrs of individuals. However, increasingly when I am choosing the stories from the archive (because I am compelled to make a choice both by the archive itself and by the temptation of finding my public) about Ingrid Jonker's despair, Bessie Head's madness or, most of all, Brenda Fassie's capricious drive to self-destruction, I hear the echoes of Holocaust survivor Leon Weliczker Wells railing against the idea of 'celebrating resistance'. He called it a 'horrible idea... I don't want to be a martyr and nobody wants to be a martyr. Only other people try to make martyrs and fighters,' he said.47

The project, perhaps because it does concentrate on individuals who were not in the forefront of the great political struggles for the most part, and on the archive of their personal effects - their letters, sketches, reported conversations, and so on - brings their voices into plaintive agreement with Weliczker Wells. I was also sometimes recalled to the microcosm of the personal archive, like Ngoyi's letters, by my fellow researchers, and encouraged to read them more carefully by a class of students who were not trained in history. My point here then is that I was sensitised to a more critical reading of the archive by colleagues and students who were not necessarily professional historians and through the process of attempting to call an attentive public into being. I was also, as I shall try to show next, stimulated by the memorials themselves, to follow avenues that I might not have had I been working as an academic historian within the parameters of a traditional research project.

The memorials

I could not possibly discuss all the memorials in the space of this article. In taking my reflections forward, I focus only on two: the Brenda Fassie memorial in Johannesburg and the Ingrid Jonker memorial in the Western Cape.48

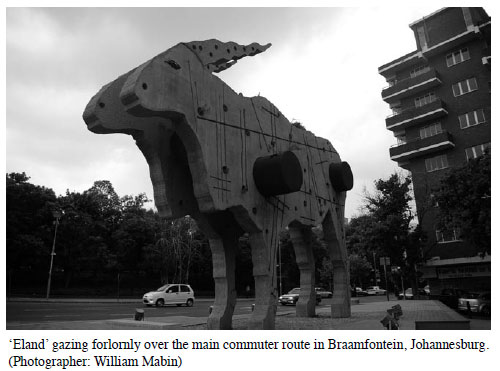

The Johannesburg memorials of the Sunday Times project have fallen within the ambit of the City's Public Art vision, as articulated by its Director of Immovable Heritage, Eric Itzkin, as part of a bigger plan addressed to 'race-based seclusions of the past' in favour of a 'new inclusive cultural and creative identity'.49 Itzkin's framing of an inclusive identity based on a 'culture' that is not ethnically particularised does seem to represent something of a novel departure point, capable of embracing metaphysical questions that elude what has become the conventional founding myth based on an abridged version of the ANC-led liberation struggle. The most striking example of this new metaphysical bent is the five and a half metre tall Eland erected last year (2007) on the corner of Bertha (the extension of Jan Smuts Avenue) and Ameshoff Streets to mark the Braamfontein Gateway into one of the City's Improvement Districts. Eland is clearly meant to call up a history that precedes the formation of the ANC by several centuries gesturing to the reverence in which this particular antelope was apparently held by the ancient hunter-gatherers of whom only the faintest traces can still be seen on Johannesburg's landscape. At its unveiling in August 2007, Chief Executive Officer of the Johannesburg Development Agency, Lael Bethlehem, remarked in her official address that Eland should prompt 'reflection on our relationship to the past, and to the interconnectedness of environmental, cultural and spiritual destinies' and that 'the Braamfontein Gateway... is a busy connector of our lateral geography of memory and the spirit'.50

Eland is supposed then to evoke grasslands long lost to the main commuter artery passing before his gaze, but which, nevertheless hold the key to what must seem to its 'forlorn' glass eyes, the senseless rush into a city often synonymous with soulless greed.51 Through our proximity to the spiritual potency exuded by Eland, perhaps we are supposed to find our way towards a better city able to rise above its crass materialistic origins. The memorials of the Sunday Times project, although deliberately created on a much smaller scale and with less rhetorical fanfare, like Eland, give the impression that they are self-consciously erected on the 'palimpsests of historical experience' to use the phrase coined by the editors of the recently published collection, Desire Lines.52

The Sunday Times memorials are nothing like the architecture of, say, the Apartheid Museum which, as Lindsay Bremner following the architects' own lead, says: 'functions as a metaphoric body, damaged by apartheid' through which the visitor is required to move, 'traversing its gaping wounds, stalking its fractured vertebrae...'.53 Through their generally economical use of the space on which they stand; the non-confrontational lines of their design even when they have been created like the Rock of Ages outside the police station in central Johannesburg to commemorate the victims of unspeakable abuse; and their most common choice of resilience and survival against the odds over tragedy and self-destruction seem to allow for participation 'in the everyday performance of urban life'.54

There is every sign, even if they have not always plainly articulated it, that many of the artists commissioned to create the memorials for the Sunday Times project understand that they are building on, even communing with, various 'underlying strata' although they probably do not recognise them as inherently unstable, as Desire Lines editors, Noëleen Murray and Nick Shepherd do.55 Stephen Maqashela, creator of the Lilian Ngoyi memorial, has woven his sewing machine made out of car parts into the deteriorating fence of her old home in Soweto, learning more about Ngoyi from her old neighbours, friends and comrades as he made the memorial; Lewis Levin, creator of the memorial to South Africa's first black advocate, Duma Nokwe, has sought to reinforce the impression that we 'live among ghosts';56 Madi Phala made the miniaturised replica of the prow of the SS Mendi sink into the earth of a neglected area of the University of Cape Town's Middle Campus where the Mendi troops were once billeted, almost as testament (we might read it fancifully) to the artist's intuition of his own demise at home, rather than in the chilly waters of a foreign sea.57 Phala, in fact, talked about the decision to make the memorial 'flat on the ground so that it became part of the environment and people could walk across and through it'.58

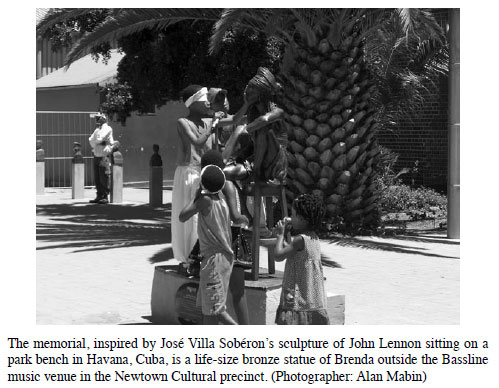

We do not know yet, except in the most obvious case of the Brenda Fassie memorial (see picture) what the passers-by think. Do they have a sense of themselves dwelling in that 'double temporality' that Lynne Meskell, one of the Desire Lines authors calls attention to, drawing on Grant Farred's description of the 'awareness of living with the past in the post-apartheid present'?59 In his evaluation of Western Cape township tours, Leslie Witz has argued that the tour bus that whizzes past some of the most important sites memorialising recent historical events, and a tourist strategy that sites museums outside of rather than within townships, negates the latter's claim on history.60 The townships become places that do not have history, indeed places that are without time. The Sunday Times project, it might be argued, draws attention to those areas in which the traces of temporality may have been effaced on the surface so that they seem, like the townships exposed on the tours Witz describes, to be timeless and disconnected from political turbulence or the routine horrors of apartheid, depending on the circumstances. For example, the Times project calls attention to the history of what might appear now respectively only as a sleepy seaside resort; a well-known public cricket ground and a small, non-descript house in Soweto that is off the increasingly well-beaten 1976 tourist route.61

Brenda Fassie

The first of the Sunday Times memorials to be erected was to Brenda Fassie, a life-size sculpture of the singer cast in bronze, perched on a bar stool with an empty stool next to her outside the well-known jazz venue, Bassline, in Johannesburg's 'cultural precinct', Newtown. Her creator, Angus Taylor, is evidently opposed to 'conceptual art' and settled on this realist interpretation of Fassie down to her bare feet.62 Although many of the Times memorials are centred on individuals - Bessie Head, Ingrid Jonker, Gandhi, Albert Luthuli, Lilian Ngoyi, Basil D'Oliveira, Duma Nokwe, Desmond Tutu, Cissie Gool, Nontetha Nkenkwe, Alan Paton, Athol Fugard and Fassie, this is one of the few realist ones. Perhaps it will prove to be the most successful because of Fassie's own enduring popularity and the fact that the sculpture is instantly recognisable and invites active companionship. Apparently bronze Brenda has already acquired something of the delinquent reputation of her flesh counterpart with programme directors inside the Bassline threatening to send unruly patrons to sit outside with her.

In his discussion of the State's Legacy Projects Rassool notes that: '[b]iography...was confirmed as one of the chief modes of negotiating the past in the public domain'.63 Rassool points to a strategy beyond or sometimes enfolded within or as the vehicle of the grand narrative in which South Africans are 'encouraged to consider, narrate and visualise their society and its past, as well as their own identities and individuals within it'.64 Elsewhere, Rassool talks about the opportunities that the making of the District Six Museum has had for 'exploring the interior and private spaces of people's lives'.65 Rassool would probably be the first to remark on the risks associated with such an intimate scale of exploration. In fact, as has been suggested above, biography tends to be the preferred mode of the Sunday Times project too, and some of the other individuals were, like Brenda Fassie, decidedly less than saintly, provoking some discomfort on the part of the researcher who is preparing to facilitate the release of the individual into the public commemorative sphere.

Working on the Fassie archive the researcher is sprayed with a veritable meteorite shower of media snapshots that caught her as the wild child of Black Consciousness, the screaming harridan, the pint-sized vamp, the pitiful drug addict, the brave and generous mother, the unconventional lover, and even the 'Madiba clan maiden', all with enormous talent which had the whole of Africa jiving.66 Fassie herself contributed to the bewildering array when she compared herself to the arch inventor of image, singer Madonna. Fassie, it might be argued, had one canny eye on the archive. She once commented to a reporter who was staring a little too obviously at her ravaged face:

See, I have done more than 25 videos, more than 15 albums, performed in more shows than everybody in this country today, partied harder and funkier than all, while feeding a tribe of relatives as well as throwing myself to the wolves of Jo'burg's smoky nightclub strips. Of course my skin would tell my stories. So, I don't' look like Naomi Campell. So what? Man, I will survive, oh, I'll survive!" she lets rip with an emotion-packed baritone.67

In this colourful rendition, I argued for the project that Fassie depicts herself as her own archive and demands a brutal reading. It is comforting to the researcher, as it was perhaps for the reporter, deciding on what angle to show to the public, that Fassie uncompromisingly renounced the airbrush. Not all subjects are as considerate of researchers. Even so, it was hard, when it came down to it, to resist the romanticism of the feisty Brenda Fassie of Khumalo's obituary who had her characteristically making 'such a fuss of her date with death'.68 It is more than probable that she was dying a protracted but sordid death from an overdose of crack cocaine. Khumalo does have a line though which both deflates what has become the customary glorification of '76, and offers a partial explanation for why Brenda Fassie as post-'76 text circulated so successfully, by calling up a public hungry for solace. He writes: 'She came into the public's eye at a time when Soweto, and many other townships, were reeling and weeping after the tragic brutality of 1976'.

Ingrid Jonker

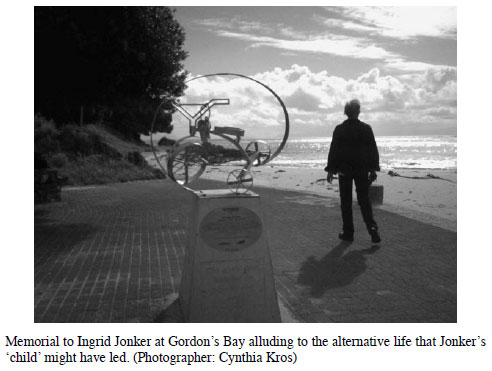

The memorial for Ingrid Jonker on the beach at Gordon's Bay in the Western Cape, is quite different from Fassie's. Its creator, artist Tyrone Appollis, is, like Jonker a poet, and he is also a musician. 'I consider political and social reconciliation to be an integral part of art, a cross-cultural dialogue, personal therapy and as communication to God,' he has written.69 Born in 1957, by far the greater proportion of Appollis' life to date was spent under apartheid. He has had his own experience of post-apartheid displacement when the memorial he created in Athlone to the infamous 'Trojan Horse Massacre' was removed and replaced in 2005 by a new memorial created by ACG Architects and the Human Rights Media Centre, in which Appollis declined to participate. The new memorial, constructed by the Cape Town City Council, cost almost R400 000, and incorporating the original wall of the site on which messages against state violence had been written. It was also a realist depiction of the police in their innocuous seeming, but deadly railway delivery truck, significantly showing the murderous security forces leaping out of the 'Trojan Horse' to shoot children with their automatic shotguns.70

In his Jonker memorial, Appollis goes for the light touch; the rhythms of his favourite musician Bob Marley's uplifting reggae rather than sombre realism and didactic reiteration. His tribute to Jonker at the rather unfashionable seaside resort of Gordon's Bay where the poet allegedly spent some of her happiest time as a child is a flat iron sculpture of a child's tricycle with flip-flops carelessly strung over the handlebars. It seems caught in the arc of its own motion as if its rider has only a moment ago tossed it aside to go to the beach. But, because the plinth is inscribed with Jonker's most famous poem - more famous because Mandela read it out and commended it in Parliament - Die Kind (The Child) which speaks of a child shot dead by police in 1960, the child's absence is also poignant and disturbing. Is he at the beach or is he dead? It is this sense of simultaneous absence and presence which the artist seems to capture so successfully, reflecting the poet's own decision at the end of the poem to resurrect the child as a giant who bestrides Africa freely without a pass. It is noteworthy that the decision was made to locate the memorial at a site where Jonker was thought to have been happy rather than at the point where she ended her life by walking into the sea at Three Anchor Bay.

As a researcher who has dipped into the archive, it is also easy to see little Ingrid at Gordon's Bay and the outskirts of the neighbouring village, traipsing sleepily after her beloved ouma, forming the image in her precocious poet's brain of the rain covered sea blossoming like a 'giant white flower in her peripheral vision'.71 Ouma, with the little girl whose prodigious talent half-scares her in tow, is on her way to preach to the Apostolies, coloured fisher-folk who will be the first audience for Ingrid's verses. Through their affectionate acceptance of her and her poetry, Ingrid will unconsciously develop a hatred of racism and a spontaneous sense of social justice which will bring her into painful conflict with her father some years later as he tries to make his way up the National Party hierarchy. As people pass by the memorial, they cross the literal lines on the paving upon which it stands, and they cross those subterranean 'desire lines' that mark deeper histories that brought people together and drove them apart.72

Mandela attributed great prescience to Jonker because of this poem. But the artist, in explaining the inspiration for his memorial, quotes a line from the poem that reads, with lyrical simplicity, 'this child just wanted to play in the sun'. Without wishing to subscribe to Jack Cope's patronising assessment of Jonker's intellectual limitations (see below) it seems safe to say that that would have been Ingrid's focal point too. Her elevation as political analyst and prophet of the new South Africa by Mandela is probably undeserved. It seems, if we read her own commentary on the poem that she, like the child, was caught in the crossfire of apartheid. To some extent, this might serve as a larger motif of Jonker's life. She wrote:

Now let me say something about my poem Die Kind about which so much as been said. Go back to the days in March, 1960, when blood flowed in this land. For me it was a time of terrible shock and dismay. Then came the awful news of the shooting of a mother and child at Nyanga. The child was killed. The mother, an African, was on her way to take her baby to a doctor.

The car she was in was fired on by soldiers at a military cordon. I saw the mother as every mother in the world. I saw her as myself. I saw Simone (Jonker's own child) as the baby. I could not sleep. I thought of what the child might have been had he been allowed to live. I thought what could be reached, what could be gained by death? The child wanted no part in the circumstances in which our country is grasped... He only wanted to play in the sun at Nyanga .73

One of the problems for the researcher here is to get past the images of Jonker crafted by her close, and one would imagine, hardly disinterested friends, Jack Cope and André Brink. Cope, memorably caught in a news photograph collapsing with grief at her graveside, made the extended point not long afterwards that 'she remains elusive'.74 Is this, perhaps, the kind of 'elusive' that Appollis catches so nicely in his memorial, or does Cope mean it as a synonym for moodiness and feminine unpredictability, to which we would hesitate to subscribe?

Cope portrayed what he called Jonker's 'playful seriousness', and as a child-woman-mother who wrote brilliant poetry but was not an intellectual; who wrote like (as well as?) a man but insisted on being seen as a woman.75 Much of Cope's commentary on her is overlaid with what one might unkindly call male chauvinist prejudice of the 1960s, and one feels that in paying it any attention at all one might be betraying Jonker who wrote, after being sorely disappointed by him, that Jack Cope was a 'bitter angel untrue with a flame in your mouth'.76 However, two of his phrases are irresistible. The first seems to be in tune with (although notably without the lightness and lyrical nuance of either Appollis or Jonker) the 'continuous movement' of Appollis' memorial.77 'The reprieve,' Cope writes, 'she knew all the same to be a shadow, a dream, the unattainable vision of man's heart crying for the good, defeated forever in deed though never finally extinguished'.78 The second of Cope's observations has proved capable of encouraging all kinds of reflective associations. He asks: 'Where does this gift arise, from what natural spring welling up in the banal suburbs of Cape Town?'79

One of these associations which I felt bound to pursue is the banality of Jonker's tragedy in the sense (or perhaps senses) of 'banal' that philosopher Hannah Arendt used it. On being put in mind of this, it seemed to me that banality might offer a productive explanatory approach to apartheid, as Arendt intended it to do for the Third Reich. Cope, of course, meant 'banal' in the English sense of the word with its evaluative overtones of trite, dull and tedious. Arendt uses it in the sense of the French original which is 'common to all'.80 Thus the evil she summons is the opposite of that produced by the pathological. It is committed by ordinary people, defined as ordinary because they are acting in conformity with the norms of their society. They are not psychotic; they are not remarkable; they are indistinguishable from other members of their specific, time-bound society.81

In the early 1960s, Jonker got into a terrible and, as it happened, interminable conflict with her father, Abraham Jonker through signing a petition of protest against the new Publications and Entertainments Act which would introduce new forms of censorship into the country. Her father, who was already a Nationalist MP and who had aspirations to be appointed Chair of the new censorship body, angrily dismissed the 130 writers and 55 artists who put their names to the petition addressed to the Minister of the Interior as 'nobodies'. Ingrid Jonker hit back at him by telling a reporter from the Sunday Times that the signatories were 'among the best literary brains in the country', a statement which was published in the newspaper on 3 February 1963. She called her father's dismissal of her co-petitioners 'ridiculous' and mocked his assertion that there were 'eminent writers' who had not signed the petition. 'The two mentioned by my father, Malherbe and Boshoff, have not written anything for 20 years.'82

Later, when she asked her father to accompany her to receive a prize for one of her poetry collections, he answered her with unspeakable coldness:

Na wat jy teen my gedoen het in jou onderhoude met The Sunday Timesen ander blaaie in die afgelope jaar, is ek nie geneë om jou in n kafee of enige ander openbaar plek te ontmoet nie. As jy iets met my wil bespreek, weet jy waar ek woon. Al wat nodig is, is om my te skakel en te verneem of so n tyd geleë is. Namiddae van die naweke gaan ek gewoonlik visvang.83

In essence, he was saying - not after what you have done to me through your interviews with the Sunday Times and other papers. I don't want to meet with you in public and, if you want to discuss anything with me you know where I live and you can phone to make an appointment. His last line is very cruel: 'On weekend afternoons I usually go fishing'. Nonetheless, he signed this letter with the affectionate salutation of a father. Not long afterwards, he gate-crashed the arrangements for her funeral, forcing a Dutch Reformed ceremony on the unwilling mourners who knew it would have been against his agnostic daughter's wishes.84 Abraham Jonker is revealed in the archive as a strict father who was grudging, to say the least, in appreciating his daughter's gift. But, undoubtedly he saw himself as an upright citizen and a dutiful parent. How could he have maintained this image of himself, even after his daughter's terrible unhappiness had caused her to commit suicide? The answer might lie in Arendt's characterisation of a society that perpetrates great cruelties and injustices, yet fools even its own agents with its outward appearance of legality.85 Famously, Arendt discovered through her observation of Adolf Eichmann, the Nazi leader who escaped to South America but was kidnapped and brought to trial in Jerusalem in 1961, that his was the 'banality of evil'. Throughout his detailed account of the part he had played in the deaths of thousands of Jews, Eichmann evinced almost no remorse. Most of the pity he expressed was reserved for himself. Arendt concluded that his society, through its ideological constitution, had not allowed him and others like him to think that what they were doing was wrong, even after Hitler himself had died.

Eichmann was not simply following orders, she pointed out in her meticulous way, referring to Eichmann's own surprisingly sound understanding of Kant's categorical imperative, but the Law of the Reich which outlived and, indeed superseded its progenitor. She described the 'aura of systematic mendacity that had constituted the general, and generally accepted, atmosphere of the Third Reich' with which he had lived 'in perfect harmony'.86 In her report on the trial she observed: 'It would have been very comforting indeed to believe that Eichmann was a monster...' and, '[t]he trouble with Eichmann was precisely that were so many like him, and that the many were neither perverted nor sadistic, that they were, and still are terribly and terrifyingly normal'.87 As an Afrikaner Nationalist stalwart in his particular society, Abraham Jonker seems to have fitted the same profile of being 'terribly and terrifyingly normal'. In this case, the poignancy of the memorial that gestures towards ambiguous absence, and the archive that speaks of what Jonker herself identified as petty bigotry stimulate the historian to revisit Arendt's 'banality of evil'. Arendt uses 'banal' in other senses too, approximating more closely the English usage, for example in her scathing commentary on Eichmann's speech at the gallows. In the moments before he is to be executed he makes a very silly speech, contradicting himself, and at the last, as Arendt remarks, characteristically resorting to cliché.88

There is also banality in the sense of normality of all kinds in the Jonker story as it is left to us in the archive and as it told with playful suggestiveness by the memorial, perhaps encapsulated in the normality of a child who just wants to play in the sun. It is juxtaposed with terror, pain and premature death. There is banality too of the Arendtian sort in Jonker's father's unshakeable belief in his own virtue as a member of the ruling party whose political philosophy he unflinchingly upheld. Perhaps, one might say, there is also banality in the kind of resistance she offered, at one level no more than the rebellion of a daughter against her father's ideas of whom she should associate with and how she should behave towards him.

Once this theme of banality had been established there seemed to be many instances of it in the supporting archive of the Sunday Times project - the 'banality' of Lilian Ngoyi's thin, blue airmail letters and their apparently ordinary preoccupations occasionally shot through with images of violence and an inverted morality which made it right for armed adults to kill children; the bureaucratic struggle that was waged for Duma Nokwe, the first black advocate in South Africa to have chambers in a 'European' group area and a cup of tea in the Common Room of His Majesty's; the banality of the reference book which Athol Fugard parodied in the vein of absurdist banality in Sizwe Banzi is Dead - and so on.

Conclusion

I have not quite resolved the dilemma of how we work in the 'moral witness' box constructed by the current approach of the Sunday Times to South African politics while remaining open to certain contradictory, even subversive currents that emanate from the archive. Perhaps we can do no more than remain aware of the tensions generated, and determine to resist the easy morality tale. I have not sought to test the claim made by the Sunday Times that this is not a revenue generating project. I have not begun to evaluate whether or not the publics for whom these memorials have been created are responding to them or pausing to see if they can catch a glimpse of the old, overgrown pathways with which they are supposed to intersect.

But I have tried to resist the adversarial positioning of academic history and heritage. I have tried to suggest in the course of this article that there is everything to be gained from working with other kinds of intellectuals, writers and artists - and with the local communities whose agreement had to be obtained for the construction of every memorial, although I have not touched here on this latter aspect. If academic historians set themselves up as austere authorities to check up on other members of the team in a public history or heritage project such as the one I have described they might lose the kinds of opportunities that I have tried to exemplify above to extend the archive. It is conceivable that far from enhancing the value of the project, the authoritarian historian could stifle productive readings and destroy the possibilities of people connecting consciously with the 'desire lines' that run beneath our feet.

1 List of Sunday Times Heritage Project memorials (as they appear on Sundaytimes.co.za/heritage): Desmond Tutu, Athol Fugard, Basil D'Oliveira, Bethuel Mokgosinyana, Brenda Fassie, Cissie Gool, Deaths in Detention, Duma Nokwe, Enoch Mgijima (Bulhoek), the First Trans-Africa Flight, George Pemba, Happyboy Mgxaji, Ingrid Jonker, Lilian Ngoyi, Mannenberg, Mohandas Gandhi, Nontetha Nkwenkwe, Olive Schreiner, The Race Classification Board, Raymond Dart, Raymond Mhlaba, Reverend Isaac Wauchope (Mendi), The Purple Shall Govern, Tsietsi Mashinini. Thanks to Lauren Segal for the opportunity to become involved in this project; Bronwynne Pereira for her help in locating and providing sources, and to the Wits / UJ Women's Writing Group for their invaluable comments.

2 J.E. Young, The Texture of Memory: Holocaust Memorials and Meaning (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1993), 15. [ Links ] 'Biography' is used here to highlight Young's approach as a life history of the memorials he analyses in Europe and the United States of America.

3 C. Rassool, 'Community museums, memory politics, and social transformation in South Africa: Histories, possibilities and limits' in I. Karp, C. Kratz, L Szwaja and T. Ybarra-Frausto, eds., Museum Frictions: Public Cultures/Global Transformations (North Carolina: Duke University Press, 2006), 290, 295. [ Links ]

4 C. Rassool, 'Memory and the Politics of History' in N. Murray, N. Shepherd and M. Hall, eds., Desire Lines: Space, Memory and Identity in the Post-apartheid City (London and New York: Routledge, 2007), 124. [ Links ]

5 C. Saunders, 'The transformation of heritage in the new South Africa' in H. E. Stolten, ed., History Making and Present Day Politics: The Meaning of Collective Memory in South Africa (Uppsala: Nordiska Afrikainstutet, 2007), 194. [ Links ]

6 Saunders, 'The Transformation of Heritage', 193.

7 K. Jenkins, Re-thinking History. (London: Routledge, 1991) and On "What is History?" From Carr and Elton to Rorty and White (London: Routledge, [ Links ] 1995). [ Links ]

8 See collection of papers produced to mark the fortieth anniversary of E.H. Carr's, What is History? D. Cannadine, ed., What is History Now? (Hampshire and New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2002). [ Links ]

9 This is a crass example, which comes from an extension of the Sunday Times project rather than the project itself. It is meant to make the point that one does need basic accuracy checks.

10 M.J. Daymond, 'From a Shadow City: Lilian Ngoyi's Letters, 1971 - 1980, Orlando, Soweto' in Postcolonial Cities; Africa. A2551. Lilian Ngoyi Collection, South African History Archive (SAHA).

11 S. Body-Gendrot and R.A. Beauregard, 'Imagined Cities, Engaged Citizens' in R.A. Beauregard and S. Body-Gendrot, eds., The Urban Moment: Cosmopolitan Essays on the Late Twentieth Century City (London and New Delhi: Sage Publications, 1999), 4. [ Links ]

12 Body-Gendrot and R. Beauregard, 'Imagined Cities', 3.

13 V. Bickford-Smith, 'Urban History in the New South Africa: Continuity and Innovation Since the End of Apartheid', Urban History, 35, 2 (2008), 315. [ Links ]

14 We might wander as far as fiction. Who better than Ivan Vladislavić to illustrate the city as 'social fact'? See, for example, his brilliant portrayal of the middle class getting into the skin of the city and animating it with its own paranoia and fear of public spaces in I. Vladislavić. Portrait with Keys: Joburg and What-What (Roggebaai: Umuzi, 2006), 165-6. [ Links ]

15 Letter from Lilian Ngoyi to Belinda Allan, March 1975. A2551. Lilian Ngoyi Collection, SAHA. Ngoyi writes in connection with her alcoholic daughter: 'In as much that everybody is asking why is your garden such a flop? Inwardly my first garden which is peace and family life has deteriorated because of trials of course.'

16 Daymond, 'From a Shadow City'. Some of Ngoyi's correspondence went missing - presumed confiscated.

17 H. Geldenhuys, 'Lilian Ngoyi Memorial Unveiled'. http://heritage.thetimes.co.za/memorials/gp/LilianNgoyi/article aspx?id=560909, accessed 12 November 2008. [ Links ] When I visited this memorial with a class of students in May 2008, Ngoyi's daughter appealed to our tour guide to bring something that would restore the memorial which was becoming corroded by the elements.

18 See Young, The Texture of Memory for discussion of the pros and cons of literal versus abstract memorials.

19 A. King, Memorials of the Great War in Britain: The Symbolism and Politics of Remembrance (Oxford and New York: Berg, 1998), 141, [ Links ] and see also for the shifting meanings of memorials and his citation of Pierre Nora's idea that their meaning is endlessly 'recycled', Young, The Texture of Memory, 48.

20 See Christopher Saunders's other chapter in Stolten, ed., History Making, 'Four decades of South African academic historical writing: A personal perspective', 280. [ Links ]

21 C. Bundy, 'New nation, new history? Constructing the past in post-apartheid South Africa' in Stolten, ed., History Making, 73 - 97 warns against allowing too many voices. [ Links ]

22 C. Burns, 'A Useable Past: The search for "history in chords"' in Stolten, ed., History Making, 354. [ Links ]

23 Well known journalist Charlotte Bauer was the Project Director. Lauren Segal was contracted as the educational consultant. I worked with her and with the South African History Archives (SAHA) directed by Piers Pigou and a team of mostly postgraduate student archival researchers. I worked with the Wits History Workshop on a schools aspect of the project not covered here.

24 Sunday Times Heritage Project, http://heritage.thetimes.co.za/memorials/, accessed 12 November. 2008. [ Links ]

25 'Introduction to the heritage project', http://heritage.thetimes.co.za, accessed 12 November 2008. [ Links ]

26 C. Bauer, 'How it all began', http://heritage.thetimes.co.za/article.aspx?id=570519, accessed 12 November 2008. [ Links ]

27 Bauer, 'How it all began'.

28 For discussion of Maurice Halbwachs see P. Novick, The Holocaust and Collective Memory: The American Experience (London: Bloomsbury Publishing, 1999), 3, 5, 6, 246-7. [ Links ]

29 'Introduction to the heritage project'.

30 Principally J. Winter, Remembering War: The Great War between History and Memory in the 20th Century (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2006). [ Links ] Also Novick's Holocaust and Collective Memory.

31 J. Habermas, The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere, trans., T. Burger and F. Lawrence (Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, 1989). [ Links ] The English translation only appeared some years after the original.

32 The idea of calling publics into being comes from M.Warner, Publics and Counterpublics (Massachusetts: MIT Press, 2002). [ Links ]

33 G. Eley, 'Nations, Publics, and Political Cultures: Placing Habermas in the Nineteenth Century' in C. Calhoun ed., Habermas and the Public Sphere (Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, 1992). [ Links ]

34 Winter, RememberingWar.

35 Bauer, 'How it all began'.

36 'D'Oliveira', The Sunday Times, 22 Sept.1968.

37 'Paradoxes of the Post Colonial Public Sphere: South African Democracy at the Crossroads'. Conference held at the University of the Witwatersrand, January 2008 convened by the Public Intellectual Research Project (Carolyn Hamilton, Isabel Hofmeyr and Xolela Mangcu). Also see M. Makhanya.'This President has made many good people do bad things', The Sunday Times 11May 2008, 20. [ Links ]

38 E. Hobsbawm, On History (London: Abacus, 1997), 31. [ Links ]

39 Hobsbawm, On History, 13.

40 Hobsbawm, On History, 13

41 Hobsbawm, On History, 14-15.

42 Hobsbawm, On History, 28.

43 Hobsbawm, On History, 47.

44 Hobsbawm, On History, 47.

45 J. Wright, 'Review of History Making and Present Day Politics: The Meaning of Collective Memory in South Africa', South African Historical Journal 58, 2008, 319 - 323. [ Links ]

46 'David Goldblatt to Christine Frisinghelli' quoted in A. Buys, 'Images straddling time', Weekend Review, May 10 -11 2008, 3. [ Links ]

47 Quoted in Winter, Remembering War, 31.

48 The memorial side of the project was handled by AAW Project Management (Lesley Parks and Monna Mokoena). They commissioned the artists and liaised with them.

49 Ndaba Dlamini, 'City's public art in the spotlight', http://www.joburg.org.za/content/view/1735/193/, accessed 12 November 2008. [ Links ]

50 'Majestic Eland gazes over gateway', http://www.joburg.org.za/content/view/1496/193/ accessed 12 November 2008. [ Links ] Eland was designed by Clive van den Berg. His design was chosen from submissions made by five artists. The project was managed by Trinity Session, including advisers from the City's department of arts and culture, the Johannesburg Art Gallery, the Wits School of Arts and Sappi.

51 Lael Bethlehem observed in her speech that Eland looked slightly 'forlorn'. See 'Majestic Eland'.

52 N. Shepherd and N. Murray, 'Introduction: Space, memory and identity in the post-apartheid city' in Murray et al eds., Desire Lines, 1. [ Links ] See for similar ideas Young, The Texture of Memory.

53 L. Bremner. 'Memory, nation building and the post-apartheid city: the Apartheid Museum in Johannesburg' in N. Murray et al, eds., Desire Lines, 91. [ Links ]

54 Murray et al, eds., Desire Lines, 1.

55 Murray et al, eds., Desire Lines, 1.

56 Gillian Anstey, 'The light bulb moment: The artist's concept', http://heritage.thetimes.co.za/memorials/gp/DumaNokwe/article.aspx?id=569857, accessed 12 November 2008. [ Links ]

57 The artist was murdered soon after completing the memorial.

58 Philani Nombembe, 'A watery grave is recalled on solid ground', http://heritage.thetimes.co.za/memorials/wc/ReverendIsaacWauchope/article.aspx?id=592885, accessed 12 November 2008. [ Links ]

59 Quoted in L. Meskell, 'Living in the past: Historic futures in double time' in Murray et al eds., Desire Lines, 165. [ Links ]

60 L. Witz, 'Museums on Cape Town's township tours' in Murray et al, eds., Desire Lines, 268. [ Links ]

61 It would be interesting to write a comparative paper on the Western Cape township tours discussed by Witz and others and the highly politicised '76 route through Soweto.

62 Gillian Anstey, 'Who is Angus Taylor?', http://heritage.thetimes.co.za/memorials/GP/BrendaFassie/article.aspx?id=562002, accessed 12 November 2008. [ Links ]

63 Rassool, 'Memory and the politics of history' in Murray et al, eds., Desire Lines, 118. [ Links ]

64 Rassool, 'Memory and the politics of history', 114.

65 Rassool, 'Community museums, Memory Politics' in Karp et al, eds., Museum Frictions, 299. [ Links ]

66 The last comes from Sipho Jacobs ka Khumalo, 'The infinite love of MaBrrr', City Press 16 May 2004. [ Links ]

67 Sunday Independent 8 Nov, 1998.

68 Khumalo, 'The infinite love of MaBrrr'

69 Gillian Anstey, 'Who is Tyrone Appollis?', http://heritage.thetimes.co.za/memorials/wc/IngridJonker/article.aspx?id=588194, accessed 12 November 2008. [ Links ]

70 Margaux Bergman, 'The Trojan Horse Massacre'. http://www.athlone.co.za/heritage/history/0604200601_history.php, accessed 12 November 2008. [ Links ]

71 I. Jonker, (Originally compiled by Jack Cope.) 'n Daad van Geloof' in Versamelde Werke (Cape Town, Johannesburg and Pretoria: Human & Rousseau, 2006), 193. [ Links ]

72 Desire lines are the informal paths made by pedestrians. The authors in the collection Desire Lines edited by Murray et al say that they mean to broaden the meaning of the phrase.

73 Quoted in J. Cope, 'A Crown of Wild Olive' in Jonker, Versamelde Werke, 199. [ Links ]

74 Cope is pictured collapsing with grief in the Sunday Express 25 July 1965. Cope on Jonker as 'elusive' 'A Crown of Wild Olive', 201.

75 Cope, 'A Crown of Wild Olive', 202.

76 I. Jonker, 'This Journey (for Jack)' in Versamelde Werke, 13. [ Links ]

77 Anstey, 'Who is Tyrone Appollis?'.

78 Cope, 'Crown of Wild Olive', 203.

79 Cope, 'Crown of Wild Olive', 202.

80 See South African Concise Oxford Dictionary (Oxford, 2002) and Collins Robert French Dictionary (Glasgow, [ Links ] Paris and New York: Collins, 2004). [ Links ]

81 In other words they are not the 'ordinary' people of Social History, who despite their nomenclature, generally turn out to have been extraordinary in exemplifying particular class traits or in contributing to the making of history in ways that thwart the will of the ruling class.

82The Sunday Times, 3 February 1963.

83 Quoted in L.M. van der Merwe. Gesprekke oor Ingrid Jonker (Hermanus: Hemel en See Boeke, 2006). [ Links ]

84 M.M. Levin, 'Jonker threatened writers', Sunday Times 25 July 1965. [ Links ]

85 H. Arendt, Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil (London: Penguin Books, 1994), 276. [ Links ]

86 Arendt, Eichmann in Jerusalem, 52.

87 Arendt, Eichmann in Jerusalem, 276.

88 Arendt, Eichmann in Jerusalem, 252.