Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Kronos

On-line version ISSN 2309-9585

Print version ISSN 0259-0190

Kronos vol.34 n.1 Cape Town Nov. 2008

ARTICLES

Designing histories

Jos Thorne

Independent curator and exhibition designer

Introduction

In certain museum exhibitions strong experiences are created for viewers when they are incorporated directly in a choreographed design framework. The viewer in these circumstances becomes an active participant in the museum as a whole, participating simultaneously as a performer and a viewer, not only in his or her own experience but also contributing to the experiences of others. This transformation into a viewer/performer generates experiences of authenticity in the museum space. These experiences at once engage the viewer's physical and emotional attention. In particular, the display of the human form results in its objectification, evoking strong emotional and psychological responses from viewers, and these processes evoke complex, symbolic political and historical meanings.1

In a lengthier study I presented a cross-section of problems and challenges that arose in my own progression from architect to exhibition designer. I focused on the way that viewers become powerfully engaged with exhibits in multi-faceted ways through the choreographed spaces. These are unique and creative experiences in which viewers are able to frame their readings of the historical material on display.2 In this article I look back at some of the projects I have designed, especially at the way in which exhibition design intervenes in the representation of historical production. The first part of the article is a reflection on some of the first exhibitions that I assisted in designing and the issues that emerged in the process, particularly around authorship. It comes from a recorded conversation that I had with Leslie Witz and Ciraj Rassool in Cape Town on 30 May 2008. The second part is drawn from my lengthier study and discusses the process of designing the performative and experiential dimensions of the exhibition Digging Deeper at the District Six Museum. Part Three presents brief discussions of other exhibition design work that I have done and reflects on the intentions and meanings of these exhibitions.3 It is clear that exhibition design is less effective if it is thought of as a process that follows the written text. Here I want to suggest that exhibition design is an integral part of making historical meaning.

A language of exhibitability

Leslie Witz (LW): Jos, you have been involved in range of exhibitions since 1994. That's 14 years now. I wonder if you could tell us about the ways you have been involved and how you have been engaging with history and with historians.

Jos Thorne (JT): One could say that I have been party to a turnaround in museum making and exhibition design over these last 14 years. I have been privileged to be one among many who have been immersed in the cutting edge of post-apartheid exhibition-making in museums.

I studied and practiced architecture for fifteen years before I was introduced to exhibition design at the District Six Museum in 1994. I was brought in to assist with the administration of the Museum and this included basic accessioning of photographs that had been collected by the Museum. It was an extraordinary experience to be part of, and since then I have not looked back. Working at the District Six Museum was like discovering a world of meaning, about people and about life. I was already disillusioned with the practice of architecture since the economy had been in recession after I had graduated. Practicing architecture seemed more about building and business than about people and creativity. So the District Six Museum felt fresh, it was captivating and it was fun, and everyone was there with their energy, their motivation and their interests as well as their ideals and their attitude, and it was great.

Ciraj Rassool (CR): What happened intellectually inside of you? You say there was a disillusionment with architecture, but you never really left architecture.

JT: Yes, I guess was thinking as an architect in terms of spatial elements. At first when the curators were talking about ideas and concepts, streets and alcoves, they asked me to draw up a sketch plan. So I drew in partitions that made alcoves that could depict street perspectives and also created interior spaces. My drawing skills got me more involved in the exhibition design at the District Six Museum and I learnt to interpret the ideas of the curators into spatial solutions. I learnt that there is a design translation from concepts to spatial resolutions that represent the ideas and meanings expressed by curators and historians.

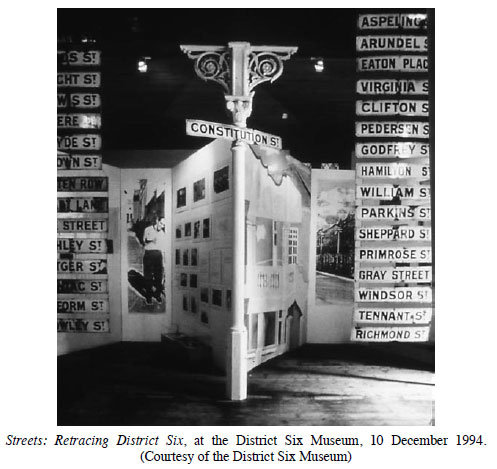

Each element of the exhibition from the very beginning was going to be about immersive participation. There was a spatial intervention and a participatory intervention. The alcoves and interior spaces, the street signs, the cloth and the map on the floor were the spatial elements. There was the ground plane, the vertical plane and the horizontal plane and each required engagement with the viewers as participants. The concept of Streets came from the actual street signs hanging from the balcony and following that the alcoves created three-dimensional 'streets'. The floor space was dominated by a large map, on which all the streets of District Six were depicted. Visitors were asked to inscribe on the map those sites in District Six that were meaningful to them.

CR: There were other things going into the making of the visual world of Streets and how it communicated, like the technique of the hand painted blown up photographs, and the technique of creating life-size realistic environments.

JT: Not quite life-size, but we were giving people cues to visualize the whole. Viewers use their own imagination with their memories to bring the exhibition to life. That is important because it involves the viewer more actively in his or her experience. If you were recreating it realistically it will be a different product, more like a theme park. The magic in the District Six Museum is created because the viewers are involved in creating their own experience.

Even though I was originally employed to help coordinate the exhibition, my work of designing exhibitions began here. It was exciting for me although I was not involved in the discussions or the concept or the intellectual processes. Those probably went over my head at the time.

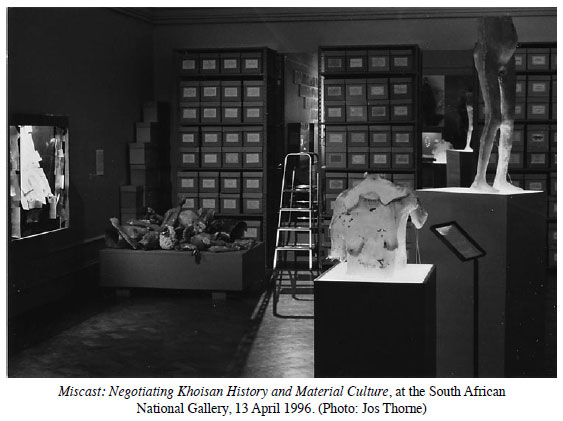

After Streets I worked as assistant to Pippa Skotnes on her exhibition Miscast: Negotiating the Presence of the Bushmen. This was an exhibition and a book produced in 1996. Working on Miscast was a thorough introduction to the world of history, museums, exhibitions and books. I had never done anything like it before. I was research assistant and started by going to libraries and archives, transcribing from publications. I discovered a whole new world that I had not engaged with before and that was the San, the Bushmen. This captivated me completely as it has so many people. I moved into Pippa's office and we worked there.

CR: It would not be unreasonable to say that the whole process of the making of that exhibition and the book, and the life of the exhibition and the book constitute probably the landmark moments in the politics of museum transformation in South Africa. There was an amassing of all the possible information you could amass in this field for the purposes of placing it in a designed environment in an exhibition and for the purposes of placing it in a book with its own concept of what the book was. And you were not just an observer and a listener but a participant.

JT: I was all eyes and ears in that period. It was all too new and too academic and intellectual and there were these powers playing themselves out. And I could see that the whole field was complicated and complex. I had emotional responses to the subject, I was interested and I was learning a lot but I still didn't say very much at that time. But in the exhibition I did participate more meaningfully because I knew design and I wasn't afraid. I did not even know to be afraid of ideas.

The material I was looking at was compelling. When you get into the storerooms of the museum, or the archive or the library, you get to see stuff the public normally doesn't see, that I now know you only get to see as a museum insider. It was an empowering experience. It put such powerful images and ideas into my head. So the ideas that came out were strong. I think design-wise Miscast was driven by the artefacts. Essentially an exhibition of storerooms, the exhibits were made up of objects usually unseen by the public. For example body casts made in translucent fibreglass (used by scientists to make the models of Bushmen on display in the South African Museum) powerfully emanated the spirit of their owners. These were presented as sculptures on lit pedestals and deeply affected the viewers. Other exhibits included a timeline made from boxes on metal shelving, there was a monument of bricks with a crown of guns, and a floor printed with newspapers, which became a major talking point about the exhibition. Each element was substantial on its own and all together they were overpowering. I remember designing the monument in the centre. It could not have been a weaker thing because it had to be strong enough to anchor the whole room. It had to face up to everything else.

Reflecting on it now, even though it was hard looking at what came out of the storerooms, it was an explosion. The exhibition demanded reckoning. And it changed everything about representation and the politics of identity at that time. In retrospect some things might have been done differently but I don't think we could have calmed that energy. Once the casts were out of the cupboard, it was impossible to put them back and forget about them. It was just impossible.

I now knew that this was the kind of work that I wanted to do and I have since been lucky enough to work on many excellent projects. After Miscast I worked on a few small projects - book designs and some small exhibits.

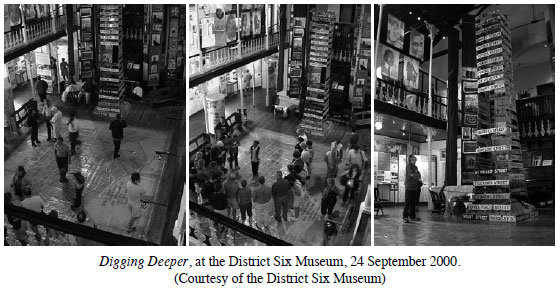

In 1999 I returned to the District Six Museum for the exhibition Digging Deeper. I had heard that the District Six Museum was reworking its exhibitions as part of its renovation. I wanted to be involved but was too shy to approach the Museum. Eventually the Museum came to me. Sandra Prosalendis asked me join the Digging Deeper team. I was to be co-ordinator with Tina Smith and Peggy Delport as curators. Only after it became evident how much design work I was doing was it decided that the three of us were co-curators. In fact everyone was part of the curatorial team, including trustees and the staff of the Museum.

CR: If there was ever an exhibition that was made through committee work and multiple layerings of knowledge in different forms it's Digging Deeper. But that alone does not make an exhibition. Ultimately someone has to take those decisions and all of those ideas and turn it all into an exhibition that does justice to all of those things and to the politics that precede it.

JT: Now I knew I could be that person, I was a designer. At the District Six Museum I was an outsider who worked from the inside. I didn't have my own agenda within the Museum. I think that was my strength. I tried to integrate as many ideas that were being bandied about.

CR: You are not saying you 'didn't have an agenda' because you didn't have the idea. For you, that is part of the exhibitionary strategy of being able to connect with the energy of the idea.

JT: There was a lot of energy there. All the people involved were curating. They all had ideas they wanted to find fruition in the Museum. It was an excellent process. The concept was fabulous. It gave us a conceptual framework that worked at multiple levels and allowed multiple curators and complexity and very different displays to work alongside each other seemingly seamlessly. Conceptually and intellectually people were thinking at a very sophisticated level and the ideas were just flowing. And there was a lot of material. So the material could direct the process as well.

LW: In the case of Miscast you represented yourself as a listener. In the District Six Museum there were committees and discussions. Were you were more deeply involved in this instance.

JT: Obviously I was in discussion with Peggy and Tina and others. In committees I didn't say much. People were talking about the exhibition intellectually and I was struggling to understand what it all meant in terms of design, I would just ask for clarity and be trying to come up with design solutions: Does this solution mean that idea? If I design this thing, does it represent that concept? I was definitely engaged and part of the team.

My intention was to incorporate everybody's expectations. Choices need to be made and I was trying to include everybody's agenda. The architectural equivalent would be to resolve a building for all its different uses, that's how I was trained to think and that's what I was trying to do. People often have divergent agendas but they are all interesting and they are all important. I must admit I didn't usually know which were more important than others. I had favourites, maybe. And sometimes I would fight tooth and nail for something I thought was right.

CR: But it came down to you quite frankly.

JT: Sometimes I could decide whether ideas were adequately resolved and ready for production or I could make something stick around for more discussion. Usually I was happy when others were happy. Sometimes it was just me who was unhappy. Then I wouldn't process it until I thought it was properly resolved.

LW: Recently the District Six Museum was praised by an historian as presenting a really historically significant exhibition and I think one of the reasons for that is that it has a lot of text. Conventionally though one of the things that people say about exhibition design is that one must minimize text because audiences don't read text. So what was the debate around this, and how did you feel around the textual nature of the exhibition?

JT: Text was a very important component of Digging Deeper. This was the first time District Six was documented into history in a significant way in a museum. Museum trustee, Irwin Combrink, came to every meeting with the idea that the texts were serious and important and had to communicate with people at different levels. No one voiced it as much as he did. We all picked up on that so we all knew that was what we had to do. It wasn't a question of 'Is it right or is it wrong?', but rather how to do it was the question. And in terms of whether texts are exhibitionary? Absolutely. I have no doubt that the exhibition needed that much text. There were so many people who need to be voiced, and it took that much text to do it. There was no cutting back on that. It would have been unfair and disloyal. It would have been a terrible mistake.

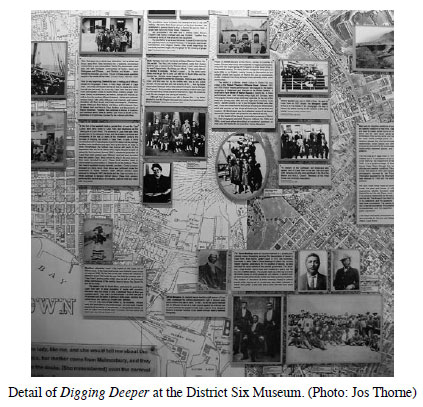

Exhibition texts are really the meat of the exhibition, where the museum augments its jurisdiction on history. In design there are several ways regarding text. The look and feel of text can both exert the authority of the museum and reveal meaning in complex and often subtle ways. For example, in many exhibitions you will find large-scale texts demanding to be read. They are obviously very important and authoritative. If large texts had sound they would be very loud. Small size texts are more like whispers, pulling the viewer in, suggesting an intimacy. By getting up close and personal, the viewer conspires with the exhibition in its history-making. In Digging Deeper many small, individualised texts make claim (amongst other things) to a multitude of 'voices' contributing to the exhibition. The exhibition texts (written by curators) and interview extracts (from interviewees but modified by curators) were give similar weight, suggesting equality between the document and everyday experience.

CR: One of the arguments that has been made most recently about those texts, particularly the quotes from the transcriptions of interviewees that they have in a sense altered what people have said and how they said it because they have almost made people more literate in a writerly sense.

LW: Yes, how the aural becomes visual.

JT: Interview extracts are powerful signifiers in exhibitions. As texts they are representational on many levels.4 In the design of Digging Deeper extracts are used throughout the exhibition. They are regarded as both image and artefact, and are placed as objects amongst others, forming relationships and reflecting new meanings. Like photographs, the text extracts represent the presence of community in affirmation and support of the exhibition and the museum.

Curators (and designers to some degree) construct and modify interviews for their own purposes. 'Cleaning up' the interview, whether on the transcript as text or as sound bite, is inevitable, a myriad of inferred meanings can be generated.

CR: One thing about Digging Deeper that shows you as designer is the relationship between the word and the image. What you did with the texts on the 'formation' and 'resistance' panels was to fix text to a spatialised geography of the city.

JT: I remember I was very excited by that idea because it was the first time I realised that history was interesting when it was related to geography. Actions that occurred in relation to place or space are what makes them interesting and real.

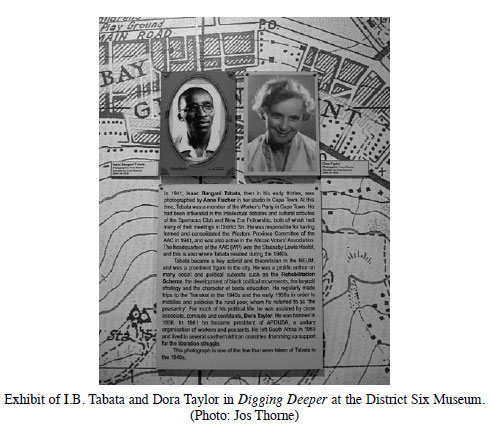

CR: And there were also decisions that you made. I may have described Dora Taylor as part of a story involving I.B. Tabata. The next thing I saw Dora Taylor and I.B. Tabata were alongside each other as if they are in an embrace. I never thought that there was a way you can represent something through placement.

JT: You told me often about their embrace and their confidential relationship. Their closeness is also apparent from the text. If you hadn't made it clear what their relationship was, it might have happened another way. So, the exhibition design was appropriate in this case and emerged out of the research. It brought out a human side of politics. It's a good example of what we are talking about, that design represents ideas by making relationships.

CR: You were able to take projects of different kinds of scale, depth and quantity and to render ideas and concerns in an exhibitable way.

JT: I was developing a language for myself.

CR: A language of exhibitability.

JT: After my Master's, which gave me a chance to reflect on my journeys through museums and exhibitions, I formalised my role as an exhibition designer, as a professional person in this sector. My experience at the Smithsonian Institute in the United States in 2001, where I was an intern as part of the programme on the Institutions of Public Culture, made me understand the changing roles and status of the exhibition designers in the museum environment. On the one hand there was the in-house designer who worked more as an artisan in the interests of the institution. This designer wore a grey coat, had limited creative space and worried about font size and wheelchair access. On the other hand a new profession of exhibition designers had emerged. These people ran private companies were often architects and worked with more autonomy. The museum became the client.

LW: On the one hand, your work reflects this change in museums in South Africa. Museums no longer use in-house design. Some are going to design companies now as well.

CR: By the early 2000s you offered an approach to making serious exhibitions about histories and social questions that worked with design, the idea of curated exhibitions that brought together all these different elements, process-oriented exhibitions. But you were not a private design company. You offered what they offered in a way that was more academically sound and in a way that was driven by a certain commitment to a politics of knowledge.

JT: Yes, I become internal to each project. The way I see it, the designer needs to be part of a curatorial team, to be integral to the curatorial processes to become part of the museum, because the whole team needs to be party to producing meaning through design. The historians also need to know what kinds of meanings are being produced through design. An example is the case in Digging Deeper where I placed Dora Taylor alongside I.B. Tabata. I inferred that there was a relationship between them. Some members of the political movement were outraged, and so the effect of the display was very powerful. Historians, curators and designers need to be very conscious of meanings implied by aesthetics and design. An outside design company would have some of that foresight but they would not have the internal sensibilities that come with the other museum professionals. They would not know the subtle meanings they can create by the way of presenting something. That's why Digging Deeper at the District Six Museum is still much more complex than any other exhibition.

CR: Now you've had upfront involvement in projects about the South African past, about the politics of representation, with a sense of scale, and a sense of drama that had gravitas and wanted to do new things in new ways. It must have been a tremendous learning experience. You were able to give ideas an effective way to communicate in visual ways.

JT: By now I had developed a sort of methodology. I realised that my lack of knowledge about any given subject gave me neutrality or an open mind. It is important to be immersed in the material and content of an exhibition but without feeling ownership. The ability to translate meaning into exhibition form is what I care about, what I'm invested in. I know that the bottom line is that what I draw is what gets made, which makes me part author, but I know that I need to be listening rather than directing. Otherwise I can't work with the people who need to be heard.

CR: You are absolutely right. But you are placing yourself within a politics of knowledge in which you have certain concepts of authorship. However, you are not simply the renderer of an idea in spatial or visual form.

JT: I have the visual, conceptual and spatial tools and the ability to produce. I work with people who are experts in their field. I listen and I try to represent what I hear. I am the one who translates from one thing to another.

LW: But you are much more than a translator.

JT: In design there is authorship, but I try to let the process be the source of expression.

LW: In your Master's research you theorized Digging Deeper and exhibition-making around notions of performance and you saw Digging Deeper as a sort of choreography.

JT: I was thinking about what kind of agency I had and what I was trying to do. It was about how design influences how people insert themselves in the space and play out the viewer/viewed duet. If I have an agenda in exhibition design, that is going to be it.

The choreography of display

From its inception the District Six Museum has been working with a number of principles and frameworks. The conceptual framework of Digging Deeper was intended to generate an interrogating methodology that directed research projects of the museum as a whole as well as a representational framework in the exhibition. I saw my role, alongside the other curators, within these processes as dealing with spatial aspects and the participation of the viewer.5 Many exhibits were designed to relate to the viewer on a human scale and were made by hand so that the texture of materials related to the human touch. Some exhibits were to be physically moved by the viewer, like the pivoting panels, while other exhibits were to be inscribed on, like the Floor Map and the Memory Cloth. Displays were created so that viewers could move into them, through and past them, creating an awareness of themselves in relationship to the displays. The exhibition sought to engage the viewers' attention not only through their visual sense but also through multi-sensory experiences.

Conceptually speaking in the District Six Museum there is no real distinction between the Museum and the exhibition. The exhibition is the Museum in action. It is the framework through which the public interfaces with the Museum. The objectives and strategies of the Museum are manifested and generated through the workings of the exhibition framework which is specifically constructed to perform these functions. For example, the Museum's emphasis on the interpretive and expressive processes of aesthetic production, whether visual, spatial or aural, was developed through a principle of developing exhibitions through collaborations with artists, writers and performers.

The Museum regularly utilises its exhibition space to host performances of many kinds. But the way in which the exhibition space acts as a performance space is more notable on different levels when visitors, especially ex-residents, are encouraged to enact their memories and feelings about their lives in District Six by interacting with the exhibition. This often leads to impromptu performances of life in District Six. During such performances all present in the space find themselves being a part of an unfolding experience. Thus visitors, by virtue of becoming involved, are embodied as both viewer and performer.

Part of the Museum's function is to encourage public debates both within the community and with the broader public. Like Clifford's notion of emergent cultures being constantly in motion the District Six Museum acts as a 'contact zone' that bridges and transgresses many previously dissociated cultural norms and experiences.6 For example, the District Six Museum transgresses the boundaries between the displays and the audience because much of the museum actually functions in the public exhibition space. Museum staff meetings often take place in the exhibition space and are viewed by some visitors as part of the exhibition. Besides the Museum staff who engage with the visitors in a performative role, visitors also sometimes view staff going about their managerial duties, as though they were performing too, with the same interest with which they consider the exhibition and displays.

Because Digging Deeper was generated through the contribution of ex-residents the exhibitionary codes are often easily understood as they are sometimes familiar. Through their own contributions, ex-residents retain partial ownership and rights to the museum and its collection. In return the Museum invests artefacts with greater power and social meaning when they are received into the collection and displayed in the exhibition. Power relations that would be intractable in other museums and hidden in cultural codes are equalised in the District Six Museum. This is because of the participation of the community on a number of levels, and because the Museum invites viewers to participate in the exhibition. Outsider viewers, also, are often incorporated alongside the insider community. In this way the distance between the curators and their audience is considerably diminished. The intersection of its community-aligned projects and participatory processes has propelled the District Six Museum to redress many contested areas of museum practice.

My evaluation of Digging Deeper has shown other aspects of how the exhibition framework and processes were designed to engage the viewer with the exhibits. The exhibition space is foremost a memorialising space, one which engages with concepts of memory and healing and is dedicated to the rich and diverse life of what was District Six. But it is also a metaphorical space in that it represents District Six as a complex and integrated inner-city urban experience. Viewers become active participants in the recovery of the past and in reclaiming and proclaiming an identity in relation to place. 'Each day it bears witness to poignant stories hitherto untold that are inspired by this environment and celebration ... where it is people's response to District Six that provides the drama and the fabric of the museum'.7 Surrounded by the abundant fabric of the exhibition, much of which is reminiscent of the old District, the viewer/participant responds emotionally and physically with the space and exhibits by inscribing on the map where they lived and by writing on the cloth their thoughts and feelings. The viewer is viewed as he or she literally becomes an active part of the exhibition.

This is the experience of museum as theatre and the viewer as performer. Like a stage in a fabricated environment, the exhibition is much like the nineteenth-century panoramas in which the viewer was 'encouraged to make the imaginative leap into their constructs'.8 Like Ilya Kabakov's Total installation, in Digging Deeper, the viewer is a active participant in a subjective experience which Michael Ames describes as the authenticity of the viewer experience.9 The District Six Museum, however, goes further than these examples. By active participation, viewers merge, becoming part of the exhibit, momentarily and simultaneously expressing themselves as viewer and as viewed. Thus in making this personal and visual contribution to the exhibition the viewer becomes indelibly part of the exhibition fabric and is able to engage in equal and reciprocal relation with the exhibition.

The exhibition is also a journey, a process of discovery whereby the viewer moves through the exhibition spaces, creating his or her own chronology of experience. Here the curatorial objectives were to generate new public histories for District Six and Cape Town that were self-reflexive, acknowledging sources of interpretation and reference. The exhibition comprises multiple viewpoints, constructing a multiplicity of approaches that go towards a deeper understanding of its collections and resources. This creates space for persistent themes, narratives and arguments to emerge. For instance, no previous exhibition in the museum had displayed an image of a bulldozer. It was felt before that the horror of bulldozers was too recent in people's minds and would not promote emotional healing.

In Digging Deeper, however, the curatorial strategy sought deliberately to go beyond the romantic, to confront people with painful realities. This approach examines and questions existing myths and stereotypes in the context of individual and collective memory by portraying many differing points of view. This is expressed in a complex narrative arrangement of displays that take up most of the lower level of the exhibition. As they move through the exhibition as a spatial environment, sentient viewers witness the drama that is generated by the interplay of their own bodies moving through space and time. Viewers are able to perceive and construct meanings from their own memories and through their bodily response to form. By making visual and textual connections within the context of the exhibition, viewers create individual interpretations of the past.

The viewer can also be understood as self-reflexive, like a dancer or an artist who experiences the world subjectively with his or herself as the centre. As Kabakov proposes there is a whole world that revolves separately around each viewer.10 Constantly subjected to the physicality of the exhibition, and choreographed by its form the viewer moves like a dancer, engaging with space and form. The viewer plays the central role in his or her own experience, performing his or her own narrative, playing out a plot and becoming the animator of the exhibition landscape.

These aspects of the exhibition experience focus on notions of particularity, subjectivity and interiority. The exhibition's aesthetic framework and the materiality of the displays and artefacts together generate the possibilities of generating open interpretations based on the inpact of the displays on the viewer's senses. The sentient viewer responds emotionally, intellectually and spatially to the environment, interpreting the material displayed and using the medium of their own bodies to manifest expressions. Particular displays such as Nomvuyo's Room, the upstairs galleries, the Museum shop, Rod's Room, the Memorial Hall floor, sound installations and hand-made banners show the integration of form, orality, textuality and visuality.

Overall, throughout the exhibition, a framework is developed to receive the personal artefacts of ex-residents and to insert these into the exhibition, thereby constructing a multiplicity of viewpoints. This relationship of receiving and presenting acts as a generative framework for open interpretation and visitor participation. The multi-faceted nature of memory is mediated through visual and aural aesthetics that are developed through a principle of collaborating with artists, writers and performers. Aspects of urbanity expressing District Six's connection to the rest of the city are translated into a spatial arrangement forming routes, thresholds and intersections that are transgressive without being rigid or prescriptive. The exhibition space and displays are dense and busy and stand as a microcosm of the integratedness and interconnectivity of urban living.

Furthermore, the exhibition framework allows different sequences of movement or chronologies to co-exist, merge and separate, as the viewers move through the exhibition following their individual interests or inspiration. Multiple readings of the exhibition are encouraged by freeing the viewer to engage with the exhibition, guided by their own interests and desire. From the perspective of the overall design it was important to envisage possible and probable routes through the exhibition, in order to anticipate certain sequences of experience. The whole spatial experience can be absorbed from any place. Many visual references and repetitions direct the viewer's attention across the space to other exhibits in a way that continuously shifts the viewer's perspective and encourages complex readings. In this way the viewer does not get lost, and the relative density and multi-sensory layering of experiences is balanced with an overall sense of comprehensibility of the entire space.

Exhibiting history

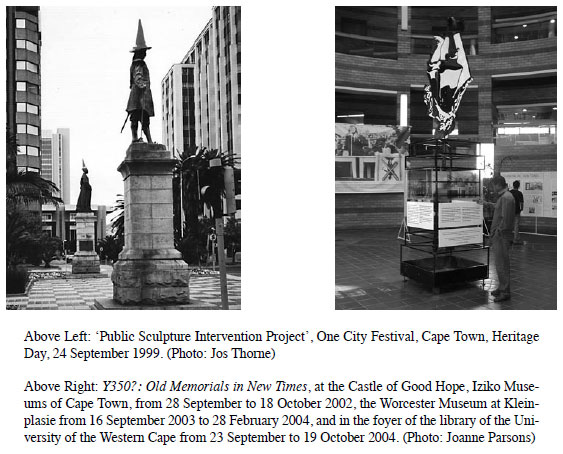

'Public Sculpture Intervention Project', One City Festival, Cape Town

This project coordinated by the Public Eye collective, invited artists to make an intervention on an existing public sculpture for one day. I had the idea to put road cones on the heads of the Jan and Maria van Riebeeck statues in Adderley Street. I had borrowed the idea which I had seen in a British magazine. Apparently it is commonplace hooligan humour which I thought was a good reference for Cape Town. The sight of the two statues with bright orange-red road cones on their heads was amusing especially with Van Riebeeck's cone sitting at a jaunty angle. It seemed like an offhand joke, a late night prank. But the cones were also a more cynical comment on the past and on historical understandings. They looked like dunce caps that ridiculed what the monument stood for. The dunce cap was a reference to an outdated British schooling system. They were also a reference to the dunce cap of self-criticism worn during the Chinese cultural revolution. In the early morning rush hour, passing pedestrians either winced in irritation or laughed with delight in a moment of historical confrontation.

Y350?: Old Memorials in New Times

Y350? was an exhibition that was produced to coincide with the 350 year celebration of the arrival of Van Riebeeck at the Cape. The City of Cape Town and the Western Cape Province were planning to stage a rather uncritical celebration of Van Riebeeck's landing in 1652. We tried to subvert the official celebration and to undermine their approaches to colonial history. Leslie Witz had uncovered that the image and meanings of Van Riebeeck that were being memorialised had some of their origins in the Jan van Riebeeck Festival held in 1952 four years after the National Party came to power. We, in turn, sought to ask difficult questions about Van Riebeeck's image. We drew upon some of the research and visual elements of the District Six Museum where a photograph of an anti-CAD protest against the Van Riebeeck Festival showed a poster of an upside-down, crossed out Van Riebeeck decorating the speakers' podium. This upside-down Van Riebeeck had also been transposed onto an appliquéd narrative banner. Now in our exhibition we set the upside-down Van Riebeeck on a mock memorial that turned in the wind. It was a subversive and ironic exhibition indicated by the question mark in the exhibition title.

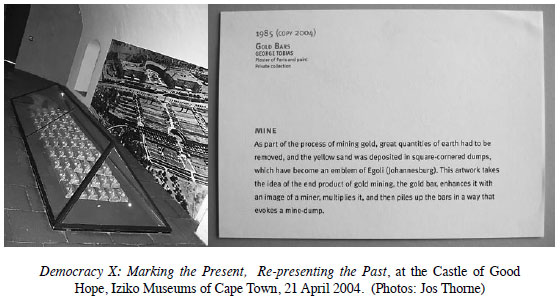

Democracy X: Marking the Present, Re-presenting the Past

Democracy X, a major exhibition commemorating ten years of democracy, was presented by Iziko Museums of Cape Town at the Castle of Good Hope in 2004. The exhibition presented a double narrative - a national history and a social history - told through the representational genre of the artwork.11The friction set up by telling a national story through the work of individual creativity was challenging for museum conventions. This convergence of fine art, social history and national history created fresh design possibilities. Although each section of the exhibition had an associated text, the exhibition chronology and narrative were carried through the extended labels of each object on display, morphing several threads and functions of the exhibition.

On the first entry on each object label carried a date of origin in large font foregrounding a historical chronology and linking all the objects in time. Next on the label was the object description, then the author/artist or the region of origin when the artist was unknown. Next came its material origin (eg. wood), then its physical dimensions and then its provenance from a collection or owner. Curatorial significance of the object and it position in the national/social history narrative was placed below the object information in a slightly larger font. All objects on display were treated non-hierarchically, resulting in equal status between artwork, artefact, document, photograph and newsclip amongst others. The labels drew from both the genres of fine art and social history. This order and status of information was designed to challenge existing exhibition stereotypes and implied new meanings and relationships.

The divergent tendency between these two genres was found in how we discussed the X in the name of the exhibition. It could have been an X without serifs that meant a cross on the ballot or an X with serifs that referred to ten years of democracy. From one perspective, the individual mark of the artist was related to the individual mark of the vote. On the other hand the exhibition commemorated ten years of democracy as a national story. In a reconciliation we designed an X that was half serif and half sans serif. So the exhibition had both multiple meanings and an original identity.

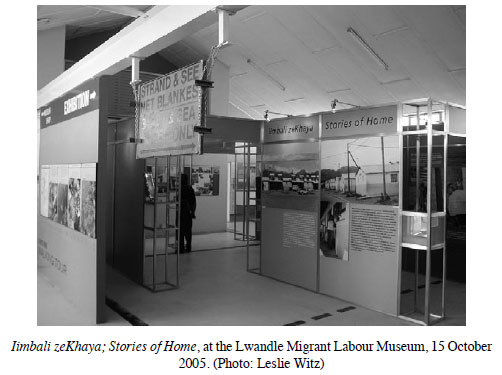

Lwandle Migrant Labour Museum

There was no museum collection to speak of in the Lwandle Migrant Labour Museum outside Somerset West near Cape Town, and creative strategies were needed to sustain community involvement. An exhibition was planned by the Museum Manager and Museum Board with a concept that explored ideas around the notion of home. A set of interviews was conducted with a group of eight prominent residents who were involved with the Museum. In making Stories of Home we had to make much out of a little and the interviews became central to the exhibition design. The exhibition became about exhibiting the interview. Interviews had been done in isiXhosa and then translated into English. We then edited them, found extracts and made them exhibitable. We translated the edited extracts into isiXhosa and the English and isiXhosa text was put on exhibition. The exhibition thus became very text heavy. Our decision was to enlarge the images so that they could balance all the text.

The interviews were not meant to represent the voice of the people as much as they sought to target community members to get involved with the Museum. The image and the quotation became very central and we blew them up very big and very loud. As a result, the interviewees became very important people. I think more generally the process of exhibiting the interview is about creating a presence of people in a museum.

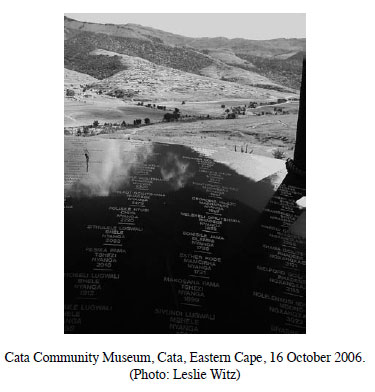

Cata Community Museum, Eastern Cape

There are two aspects to the Cata Community Museum. Firstly it documents the Cata community land restitution and development process. Here the Cata community, working with the Border Rural Committee, had secured a major land restitution and development deal which included a new community hall and a small museum space. The Museum focused on their land restitution process. The exhibition narrative covered the history of workshops, advocacy, mass action as well as the resultant plans for development. The Museum was intended to showcase land restitution and development issues and to spur on the restitution process for other communities across the Eastern Cape. This clear museum agenda comes across strongly in the display. It centres on plans and aerial images showing information about removals, evidence of meetings, demonstrations, signed contracts, and newspaper articles testifying to proceedings.

Secondly, the Museum hoped to document local social history and engage environmental interest in the promotion of heritage and tourism as part of its development plan. In a very different approach, the Museum extended its vision and took its exhibition outdoors into the landscape. A walking trail starting at the Museum building follows old footpaths along hillsides to the ruins of homesteads that were abandoned because of betterment removals. Narratives of displaced families are displayed on boards on the actual sites of removal. With the impoverished Cata village clearly in site, the ruins are visual proof of removals and dispossession. Along the trail is a constructed toposcope where visitors can view the entire Cata Valley. The toposcope directs the viewer's gaze outwards indicating where homesteads once existed, and where only ruins are now to be seen. Here the challenge to viewers is in visualising the transformed landscape before betterment. The Cata Museum and exhibition project in its building and in its inscribed landscape has been turned into an eco-museum where history is brought to life.

Slave Lodge, Iziko Museums of Cape Town

The Slave Lodge became a direct challenge around the intersecting roles of museum professionals, historians, and the role we played as designers. Conceptually, we proposed exhibition installations that were experiential. Artistic interpretations would be at the centre of the exhibits. It was hoped that these would evoke complex experiential responses to slavery and its legacy that many people still suffer under today.

The exhibition employed two concepts, 'human rights to human wrongs' and 'remembering slavery'. Images, sounds and textures were intended to engender empathetic responses to the indignity and suffering entailed by slavery and presented an opportunity to transcend this by acknowledgement, commemoration, and a sense of justice.

In the second gallery we created an impression of the interior of an 18th century slave ship. Using construction, images, props, lighting and soundscape, the exhibits invites the viewer to imagine the painful journey to the Cape. In the next space a 'column of light' made up of glowing, translucent, rotating rings of resin contain some of the 6000 names of those who lived and died at the Slave Lodge. The accompanying annotation reads:

Rotating the rings on the column acknowledges the past and provides a symbolic release from oppression. ... The rings of the column of light are inspired by tree rings, symbolizing rings of life, passing of centuries and 'holding' of memories.

Histories of suffering are never easy to represent in an exhibition. The language of art provides greater space for bold statements about personal hardship and the possibilities of redemption, forgiveness and historical reckoning. This is connected to the ongoing work of challenging slavery and oppression internationally.

Conclusion

In a paper that they presented at a symposium at the McGregor Museum in Kimberley, Gary Minkley, Ciraj Rassool and Leslie Witz commented on the processes that the museum was undergoing with its new exhibitions, Frontiers and Ancestors. These exhibitions were intended to signal transformation in the Museum, and Martin Legassick from the UWC History Department had been called in to find, verify and authorise facts 'which were then made ready for display'. Once the facts were verified, they relate, these were 'handed over to the design consultants to turn into an exhibition. The facts of history were then presented in a sequence of dioramas and tableaux making up broad sweepstrokes of the region's past'.12 Minkley, Rassool and Witz then issued a cautionary notice about the practice of separating out the work of design and that of the academic historian.

This division of labour between separate groups of experts and the attention to the separate skills required in each stage has been a common curatorial practice. Although there might be occasional meetings between the groups they operate largely independently of each other. It is time to open up questions about the continued value of such museum methods and their failure to acknowledge that exhibition designers are more than visual functionaries following the historian's script. The danger is that the codes and conventions for understanding and representing the past which have characterised museum practices throughout southern Africa for many years are taken as a fixed body of neutral knowledge. There is the distinct possibility that the agenda for a new history on the part of the museum, and to which the academic historians are contributing, will be undermined.13

Much of the work that I have done in South Africa's new museums, like Cata Community Museum, the District Six Museum and Lwandle Migrant Labour Museum, and some of its older ones, like Iziko Museums of Cape Town, indicates that their warning is most definitely one that needs to be taken heed of. Through the curation of spaces, the presentation of texts and the visualisation of individuals and events, significance is constantly being accorded and histories produced. The processes described above show how the methodologies of display are not fixed but are constantly in formation, responding continually to the changing politics and poetics of space and place. Histories in museums are not a simple visual rendering of the academic historian's text. There are always contests over histories from different communities. A variety of academic experts are constantly asserting claims to knowledge and authority. Above all, from my perspective histories in museums are conceptualised and choreographed through engaging the limits and possibilities of visualising new and different pasts.

1 J.L. Thorne, 'The choreography of display: experiential exhibitions in the context of museum practice and theory' (M.Phil diss. University of Cape Town, 2003). [ Links ]

2 Thorne, 'The choreography'.

3 Leslie Witz and Ciraj Rassool assisted me in thinking through the structure and arguments of this paper. Over the years I have worked with and learnt from some of the most original exhibition makers, artists and public scholars through a number of exhibitions. Among them are Peggy Delport, Tina Smith, Pippa Skotnes, Lalou Meltzer, Crain Soudien, Leslie Witz and Ciraj Rassool. However, I alone am responsible for the conclusions contained in these reflections.

4 For a full discussion see Chrischené Julius, this volume.

5 For an extended discussion of experiential exhibitions and performative displays, see J.L. Thorne, 'The choreography of display'.

6 J. Clifford, Routes: Travel and Translation in the Late Twentieth Century (Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1997), 12. [ Links ]

7 S. Prosalendis, J. Marot, C. Soudien, and A. Nagia, 'Punctuations: periodic impressions of a museum' in C. Rassool, and S. Prosalendis, eds., Recalling Community in Cape Town: Creating and Curating the District Six Museum (Cape Town: District Six Museum, 2001), 75-6. [ Links ]

8 T. Kamps and R. Rugoff, Small World: Dioramas in Contemporary Art (San Diego: Museum of Contemporary Art, 2000), 6. [ Links ]

9 I. Kabakov, On the "Total" Installation (Bonn: Cantz Verlag, 1995); [ Links ] M. Ames, Cannibal Tours and Glass Boxes: The Anthropology of Museums, (Vancouver: UBC Press, 1992), 158. [ Links ]

10 I. Kabakov, On the "Total" Installation, passim.

11 For an extended discussion of the curatorial considerations in Democracy X, see R. Becker, 'Marking time: The making of the Democracy X exhibition', in A.W. Oliphant, P. Delius and L. Meltzer eds., Democracy X: Marking the Present, Re-presenting the Past, (Pretoria: University of South Africa, 2004). [ Links ]

12 G. Minkley, C. Rassool and L. Witz, 'The Castle, the Gallery and the Sanatorium: Curating a South African nation in the museum', paper presented at the Workshop 'Tracking Change at the McGregor Museum', at the Auditorium, Lady Oppenheimer Hall, McGregor Museum, Kimberley, 27 March 1999, 12-13. [ Links ]

13 Minkely, Rassool and Witz, 'The Castle', 13.