Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Kronos

On-line version ISSN 2309-9585

Print version ISSN 0259-0190

Kronos vol.32 n.1 Cape Town 2006

ARTICLES

Tales of Urban Restitution, Black River, Rondebosch

Uma Dhupelia-Mesthrie

History Department, University of the Western Cape

Three men and a claim

The madressa in Lady May Street in Rondebosch East was abuzz with activity on the evening of 19 June 1996. About fifty people - only five women amongst them myself - took our seats in the small hall. People came mainly from the Cape Flats but also from other parts of Cape Town: Garlandale, Athlone, Rylands, Crawford, Crest Haven, Lotus River, Grassy Park, Belgravia Estate, Lansdowne, Manenberg, Plumstead, Penlyn Estate, Heideveld, Diep River, Bonteheuwel, Kensington, Bridgetown, Woodstock, Surrey Estate, Rondebosch East, Rondebosch, Rosebank, Wynberg, Beacon Valley, Mitchells Plain, Hout Bay, Belthorn Estate, Welcome Estate, Penlyn Estate, Silvertown, Kenwyn, Hanover Park, Kuils River. There was even one visitor from Harare.1 These individuals had a common history - they and their families had once lived in an area in Cape Town known as Black River/Swart Rivier. I was informed about the meeting by a few individuals whom I had interviewed a year earlier for a paper I wrote on the application of the Group Areas Act to Black River.2

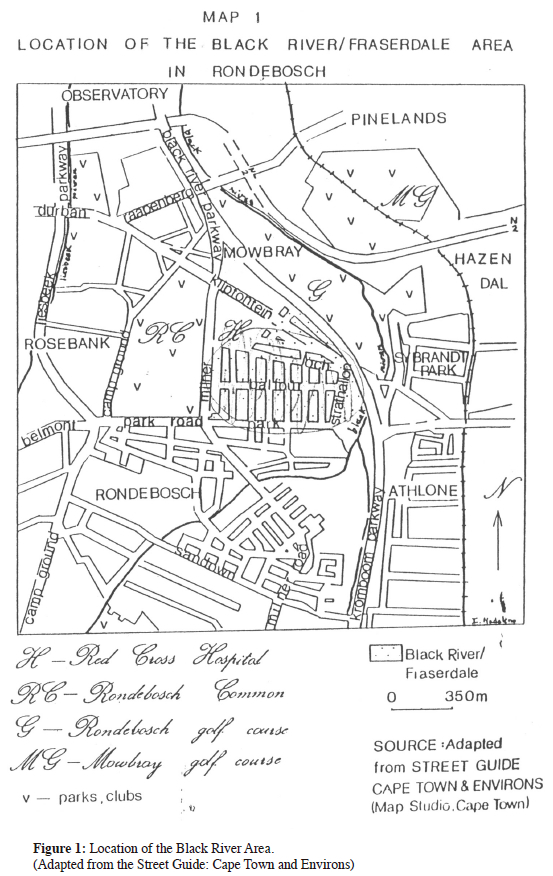

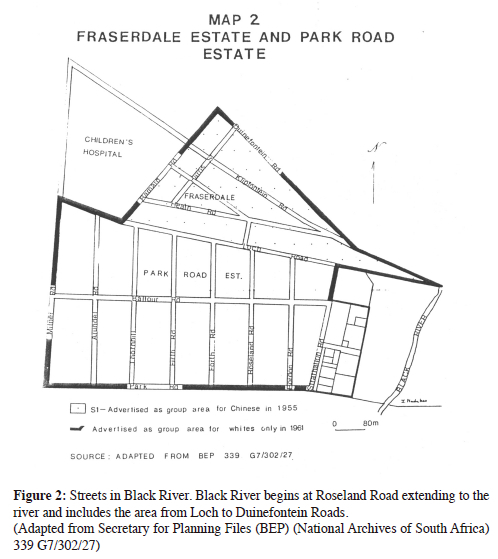

I had developed a fascination about the area Black River mainly because in my trawl through the Group Areas Board's files it had turned up under the name Fraserdale. I had had difficulty placing it until I saw a map which pointed to one of Cape Town's famous suburbs, Rondebosch. Black River lay just across the Rondebosch Common near the Red Cross Hospital (see Figure 1 for location). I discovered it was made up of two parts: firstly, what was in early days known as Fraserdale Estate stretching from Loch Road to Klipfontein and Duinefontein Roads (with the Rondebosch Golf Course outside its north and north eastern boundaries) and secondly, part of Park Road Estate - from Roseland Road down to Strathallan Road (see Figure 2). About 300 families classified coloured, Malay and Indian totalling just under 2,000 individuals lived here in 1966 when it was proclaimed a white group area. Most were forced to leave in the period 1967 to 1971 with the last two families leaving as late as 1979.

Black River, my research uncovered, was occupied by many middle class families (teachers, shopkeepers and petty entrepreneurs); a number of artisans (painters, plumbers, plasterers, bricklayers, carpenters and tailors); dressmakers, nurses, garment workers, cooks, washerwomen, shop assistants, cleaners, street sweepers, postmen, gardeners, messengers, drivers. While their addresses would indicate that they lived in Rondebosch, they saw themselves as a distinct community - Black River. As one resident explains:

Nobody ever said that 'Oh are you from Rondebosch?' Because then ... you'd have to specify now which area of Rondebosch you know, because Rondebosch ... when they spoke of Rondebosch - they automatically thought well the white people stay in Rondebosch ... No if you say Black River then they know exactly which little community you come from.3

The name derived from the then flowing Black River below Strathallan Road. A church had been established here as early as 1865 which indicates some early settlement but Black River residents date the pioneer residents as having moved into the area in the 1920s. Initially the Black River area would have referred to Fraserdale Estate and the vicinity of Strathallan Road and below. As movement of coloured and Malay families spread into the then undeveloped Park Road Estate so did the name, Black River, extend its boundaries. Traces of the Black River community, unlike that of District Six, have been erased from Cape Town's memory and geography with the forced removals. All we have is Rondebosch, a Black River Parkway, and a canalised river that fails to evoke the past. Most of the cottages and terraced homes in Fraserdale Estate were destroyed and a freeway swallowed up the area below Strathallan Road. The rest of the homes in Park Road Estate remain. The face of Klipfontein Road has changed - new businesses have been established and the Red Cross Hospital expanded its boundaries - just a small patch of vacant land remains. It is that forgotten, buried history that I had been interested in retrieving.4

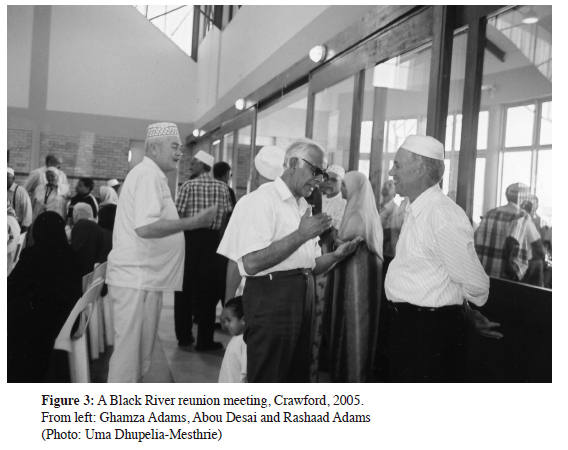

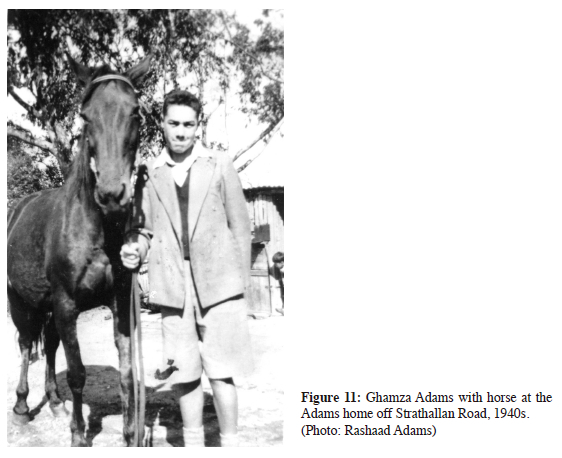

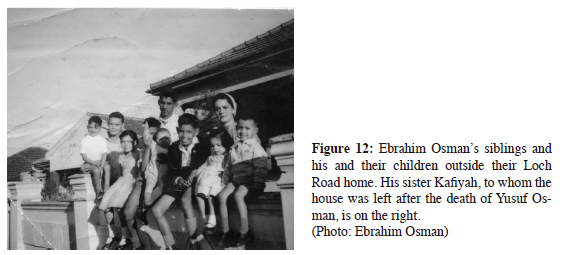

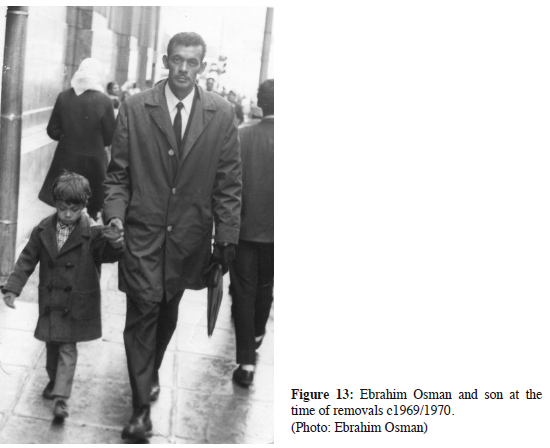

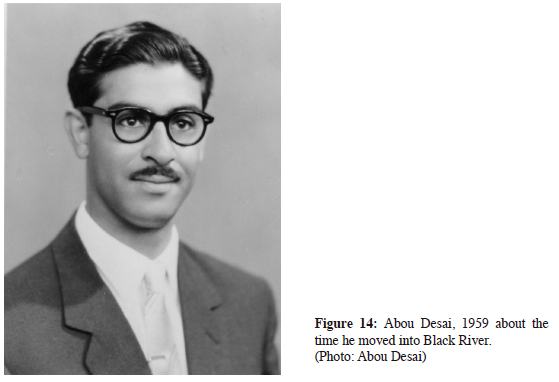

The meeting of former residents in 1996 had been convened to discuss the possibilities of restitution as laid out in law by the then two year old Restitution of Land Rights Act. A member of the Commission for the Restitution of Land Rights, or Land Claims Commission as it is popularly known, was at hand to make a brief presentation and to answer questions. Three men - all in their sixties - had a leading role both in the events leading up to the meeting and at the meeting: Ghamza Adams (b.1930), Ebrahim Osman (b.1933) and Abou Desai (b.1931).

Ghamza is the eldest son of Ebrahim and Hajira Adams, a family undisputedly regarded by former residents as amongst the oldest families of Black River. Ebrahim and his brother Mogamet Sallie ran a tailor's shop on Klipfontein Road and they, together with a third brother Abdullah Adam, an Imam at the mosque in Mowbray, set up home in the 1920s on a substantial piece of land just off Strathallan Road. As the families expanded and children like Ghamza were born, Ebrahim Adams bought land in Roseland Road and built a house 'Mouhiba' in the 1950s. Ebrahim Osman, son of Joseph (Yusef) and Gadija dates his connection with Black River through his maternal grandfather, S.Harris, who owned many properties in Black River. His own father was a builder and built a home at 62 Loch Road in 1932. As with Ghamza, Black River is his place of birth. Abou Desai, a teacher, was a relatively latecomer to Black River. He had lived in Observatory and bought a home called 'Two Ways' in Roseland Road in 1957.

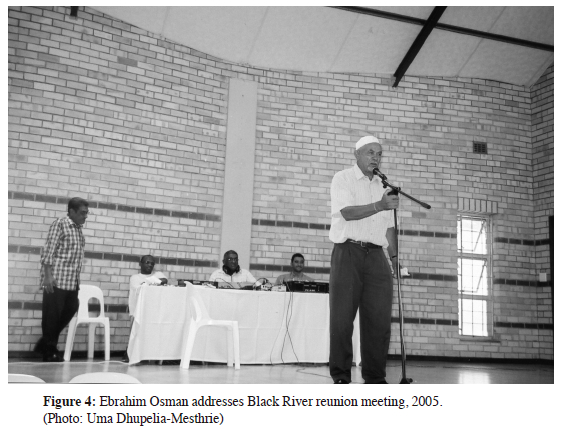

The inspiration to call a restitution meeting of all Black River residents came from Ghamza and Ebrahim. They drew Desai in because he was known for his organisation and penchant for keeping records of everything. Needless to say, as the professional amongst the three (Ghamza was a tailor and Ebrahim a builder), his skills were also valued. Ebrahim Osman describes why he felt it necessary to call all the former residents of Black River to consider applying for restitution:

The idea was because we felt, you know, that we actually started life, we started knowing ourselves in Black River. Right. We were a very close knitted community. We were a big family and that whole thing was shattered you know through the group areas ... You know we could take it ... but what about our mothers and fathers that was still alive. How did they take it, you know, because they spent most of their time there alright. So we decided ... that we're going to do something about this and that's where we came together.5

Ghamza had already lodged his claim for his family home in October 1995. His file number, A28, reflects that he was among the earliest claimants at the Cape Town office. He took a leadership role in deciding that all the residents must apply and personally went to people telling them about the meeting and handing out forms.6 Ghamza's and Ebrahim's role represent the generosity of spirit and the concern that Black River residents have for each other. Desai sees himself as completing his duties which he had assumed in the 1960s as the secretary of the Black River Ratepayers' and Residents' Association. Then they fought for the people to safeguard their homes - now they would have to work for restitution.7

Looking back at my notes of that meeting ten years back, I am struck by the importance of the questions that people asked and how wrong some of the answers turned out to be. How serious was this business of claims? Was there enough money set aside for compensation? How much money did the Commission actually have and did this include the staff's salaries? What would happen to the process if the general elections in 1999 brought into power a new government? What compensation would be paid? Would it be determined by the current market value? What were the priorities in processing claims? How long would the process take? Where in relation to District Six would the Black River case fall? If land was vacant in Black River, could they get this back?

Behind all these questions was a central concern: if people were to invest time in a process to lodge claims, they wanted to be reassured that the outcome would be of significance. They were told that by 2000 all claims would have to be settled (they were obliged to start responding to claims within months not years), that there was a choice of restitution (financial, restoration, alternative land, consideration for quick access to housing). In particular, if land was in private hands then they would have to negotiate, but if it was government or council land it would be easier. A formula had not yet been devised as to how compensation would be calculated and hopefully, while District Six would be a priority, they would process claims alphabetically. Much useful information was provided at the meeting about how to access the relevant information required on a claim form.

In two papers I wrote subsequent to that meeting, I reflected on the fact that academic interest on the land restitution process was lacking in comparison to that on the Truth and Reconciliation Commission.8 I compared the discourse of the two commissions highlighting the common vocabulary of reconciliation, healing and justice. Critics such as Mayson and Levin9 had at that stage pointed to the slowness of land restitution and its focus on negotiated settlement, the emphases on the legal process to the detriment of rural communities, the limits to justice given the sanctification of private property rights and the cut off date for claiming dispossession, namely 1913. In their book Brown et al also provided a pessimistic account of the process given bureaucratic wrangles and conflicts between the Commission and the Department of Land Affairs. Appropriately sub-titled A Long Way Home it also pointed to the lack of attention to development issues.10 I argued, however, that the inadequacies of the Land Claims Commission had led to people taking the lead themselves - calling meetings, holding reunions, guiding people. Reunions were a strategy of the people which substituted for the public hearings of the TRC, and they were an important means of coming to terms with the past. Within families, old and young were drawn together in an effort to piece together the family history. Yet there was also the potential for family conflict.

Both Ghamza Adams and Ebrahim Osman insisted in 1997 that the central reason for claiming restitution was to come to terms with 'what was done to us', especially to the elders. It was not in anticipation of financial rewards that they sought restitution. When Ghamza Adams was asked what he expected out of restitution, he could only say: 'Justice must be done.' He then went on to tell me about the Pirates Cricket Club and how it was affected as people were dispersed after removals.11 But what would be justice? Ghamza was unable at that stage to spell out the specifics of what justice would entail. Justice in the land restitution process as in the TRC, was clearly reined in by reconciliation. Derek Hanekom, the Minister of Land Affairs in South Africa's first democratic government, had made this clear when introducing the Land Rights Bill in parliament in 1994. It was a 'gigantic step in healing the wounds inflicted on our beloved country' but:

The Bill is not about taking away people's land again. It is not about confiscation and coercion. It is about justice and reconciliation. It is part of our joint attempt to rebuild our country, to reach out to one another with compassion and fairness.12

Wallace Mgoqi, the first Regional Land Claims Commissioner in the Western Cape, assured whites in the elite suburbs of Cape Town that no awards would be made that would result in 'social disruptions'.13

This article seeks to reassess the meanings of restitution for Black River residents given that now ten years have passed since that first restitution meeting. Have Ghamza Adams and other residents come to a better understanding of the justice offered by restitution and the justice they have defined for themselves? Has healing taken place? While residents may have met as a group, claims were submitted individually.14 In the end, for Black River residents, this has now become a personal family quest. The article thus tells individual stories of restitution and through these it hopes to get a nuanced understanding of the process.15

This article is also motivated by the desire to get a better understanding of urban restitution. An audit of 1999 revealed that 72% of claims were urban. In the Western Cape the percentage is much higher at 95%. Of 11,938 claims in the Western Cape a further audit in 2001 revealed that 595 are rural and 11,343 urban.16 It has been recognised that urban restitution will be limited in what it can achieve - it is only in exceptional cases that it will challenge the way in which apartheid has shaped our cities and most of the claims will be settled by financial compensation. Walker has also argued that: 'There has been a lack of attention by the state to the symbolic, cultural and psychological elements of restitution ... only minimal attention has been given to the non-material issues around memory, public recognition and identity that inform many claimants.' My article points to how important these 'non-material' issues are. Yet it also tries to respond, in a small way, to Walker's call for studies to measure the impact of financial settlements.17

A story 'from my heart'18

I said to my daughter: 'Let's go to the bank. Did you take the day off?' She says 'Yes'. We said 'Let's go to the bank'. We went to the bank. I took R10 000 from there and I blew it. I bought cake for the children and I came home and we had a celebration and all the grandchildren were sitting at the table. ... I put money under their plates. 'There's a party!' and I said 'Yes, look under your plates' and I gave them all as much money as I thought I could give them and they had a whale of time with that money.

This is Mona Dawood's account of what she did that day in 2005 when she received her restitution cheque for R40 000. Since that day most of the money has been spent - she bought generous gifts for her descendants such as fridges, a DSTV, a fan. Today, little remains of that sum. Why did she do this? Her tale is a very instructive one on the limits and failures of restitution.

Mona (b.1920) is a very sprightly woman. At eighty-six it is difficult to set up a time to interview her. On one day she is busy attending a family funeral and for three mornings of the week she teaches for ninety minutes at her daughter-in-law's play school (she has been a teacher for most of her working life). While I had not met her before, through my research I had come across a newspaper article of 1961 where a Mrs M.Dawood had defiantly told a reporter: 'They will take this house away from us only over my dead body. Here we are, here we stay.'19 But they did take her house. When I finally meet her at her home in Crawford I am struck by her appearance - this is no frail old lady. She is neatly dressed with a scarf covering her head. She wears glasses but is in good health. Among the many things that come across in this interview is that she has a strong personality, believes in a very strong work ethic, is generous in her spirit and has a very close happy family. She is proud of her two daughters and son, and speaks fondly about her six grandchildren and seven great-grandchildren. She and her family worked hard for what they have achieved and she lives very comfortably. She shows me her neat comfortable bedroom to which she can escape the bustle in the house when necessary.

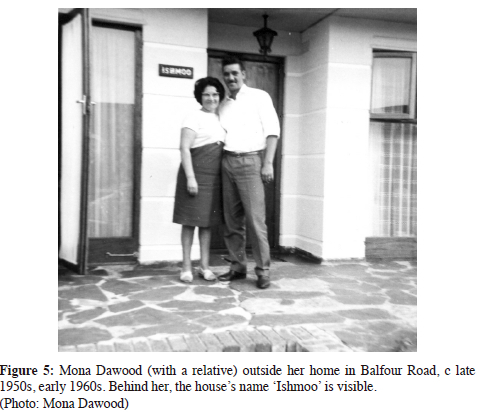

Mona and her husband, Ismail, a tailor (now deceased) lived in Balfour Road, Black River (see Figure 2). Even before she moved there, Black River was well-known to her - her maternal uncle Moegamat Noor Peters was one of the earliest residents there and she recalls many happy and regular visits to his home on Strathallan Road. She lived for a while in Vasco after her marriage, but moved to Black River after her uncle helped secure a plot and built a home for her there. It is important to note how Black River residents built their homes. Since many of them were builders they helped each other build. Rashaad Adams, Ghamza's brother, best explains this:

You know how we built there. Say for instance, now you were a Black River citizen and you bought a plot there. Now you're owner-builder. Now the people in the area is plasterers, or carpenters or brick-layers. They will all come now on a Saturday and help you build your house. This is the way our house was built and many other people.20

Everybody benefited from this system because those who had contributed their labour would ultimately themselves need help for their homes. Mona also rewarded the relative who had taken not a cent for doing her ceiling by giving him groceries and cash when he fell on hard times. How these homes were built is critical in understanding what people felt about the houses in Black River - many memories of hard work and fun at weekends and after hours are attached to each house. Each house had a name - the Dawood's was called 'Ishmoo'. The houses, especially those in the Park Road Estate area, were fairly new and designed according to the owner's special needs. Mona wanted a small kitchen for convenience and got it built as she wanted. Removals brought sadness, grief and a sense of hopelessness against the government. Mona's story of restitution unfortunately reflects a parallel experience. Mona describes what restitution has meant for her in a way that the transcription of that interview cannot convey effectively at all. Much emotion lies behind the bare words. Having interviewed many residents about their removal in the past, I am quite unprepared for the emotions evoked in me as she tells her story of restitution. 'From my heart it was sad. It was sad. Sad, sad, sad', she says.

She was present at the Black River restitution meeting in 1996 and subsequently lodged her claim with the help of her daughter and son. As a result of her age, her claim was eventually prioritized. She remembers asking the Commission's staff whether restitution would come 'when I am ten feet under?' Mona's disappointment with restitution comes from the fact that after she had submitted her claim she saw her house advertised for sale. She and her daughters then made a painful visit to the house - she noted the small alterations that had been made such as the addition of a small pool. They told the owner of the house not to explain anything as they knew the house - this was their house. The owner was silent and uncomfortable. Following this visit and with the knowledge that the house could be bought, Mona made an urgent visit to the Commission's office. She informed the Commission that she wanted her house back and she wanted their help to achieve this. The current owners wanted R500 000. Mona makes a point to me that she did not want to be given the house. She wanted to buy it but not at that price. She observes that at the time of removals they had sold the home to a Portuguese immigrant 'for a pittance'. There was no justice in the current owners benefiting from a sale at the current price. (People in the 1960s and 1970s in the climate of forced sales disposed of their homes for between R5 000 to R12 000). She wanted the Commission to help bring the price down by some negotiations, and make a contribution towards the re-purchase. She was entirely within her rights since the law provided the option of securing the property back. She describes the reaction of the Commission's staff:

And guess what they told me? 'We can't put those people out.' I said 'I didn't tell you to put the people out. I want to buy the place but not at that price.' So they said 'No, but we can't do anything about it. We can't tell the people to lower the price for you.' So I said 'Yes but you [government] could throw us out.' Wasn't that a nasty thing to do? ... So they said 'either you can get another piece of land or you can take the money.' ... So I said ... 'I don't want another piece of land. Where you going to give me land? There's no land there. Where you going to give me land?' He said 'Then the alternative is you will have to take the money.' So cold and callous.

So Mona's sadness comes from not getting her house - her disappointment and helplessness comes from feeling that her interests were not seen to. 'I didn't want the money. I wanted my house', she stresses. 'It would have satisfied my heart. That is mine ... Ya and I got it back.' I ask her if she considered getting legal help and she draws on history - the ineffectiveness of lawyers to prevent their removal from Black River. 'Why?', she says. 'I had an experience of lawyers man.

We all contributed there in Black River. We got nothing.'21She says she 'brought the roof down' at the Commission's offices trying to get her view across but failed. So her final conclusion about the restitution process is 'They failed me. Yes. Big'. She now explains why she spent the money in the way she did. 'They didn't want to give me my heart's desire so I am giving the children their heart's desire. I don't think they have ever seen so much money before.' And from this giving, Mona gets some happiness. Her story of restitution is accompanied by a retelling of the story of removals - the hardship of finding a new home and starting all over again. In the context of the failure of restitution the one narrative has to be accompanied by the other and is retold with intensity.

A small donation22

Baboo Mohamed (b.1943) was nine years old when his father Hassan and his mother Mariam moved from Grassy Park to Black River. They took over the shop Park Estate Lucky Store on Strathallan Road and occupied the house behind it. In 1960 Hassan bought the shop and house from Hassan Mathews who owned quite a bit of property in the area. Mohamed was classified Indian but Mathews was classified Malay and a transaction could not legally take place between two different race groups.23 The Mohamed's did what many an Indian in Cape Town did at that time - they used a nominee to purchase the house. The nominee, a relative, was by their account an 'Indian through and through' but had managed to get classified Malay. So, in this way, the Mohameds secured what they thought was a safe home. Three years after Black River was proclaimed white, Hassan Mohamed died - his last years were years of great worry. Through the nominee the house was sold in 1969 but Hassan's wife and children continued to live there as tenants until 1979. They moved to Belgravia Estate for eighteen months before finding a home with much difficulty in Rylands.

Baboo, now 63 years of age, is semi-retired. He keeps busy. He runs a small lift club taking children to school and until recently offered a service to students wanting to travel to the University of the Western Cape. The constant increases in the petrol price have not made this a profitable business and he may have to reconsider what he is doing next year. He sometimes makes burglar-bars for sale. When he lived in Black River cars were his passion and he worked as a part-time panel beater and serviced cars. His sister, Fatima (b.1947), is an accountant. She had shared the house with him in Black River and still shares the house with Baboo, his sons and grandchildren in Rylands. The brother and his sisters (others are married) are very close. This closeness determines how they worked on their restitution claim. Baboo and Fatima decided that he would work on the Black River claim and Fatima would work on the extensive properties her father owned in Windermere. Just a few weeks before my interview with him, Baboo had been in to sign what the Commission calls his vouchers. This means his claim is about to be settled and he knows the amount he will receive for the two properties he claimed for on Strathallan Road. He shows me the sum but would rather not disclose the sum publicly. He need not be so wary - this is about what tenants receive all over Cape Town according to a Standard Settlement Offer. The final resolution and the sum (although not yet received) influence their tale of restitution.

While the Mohameds were owners, they have not been able to claim as owners. They have no proof that they were the owners. Baboo was reluctant to visit the nominee's family - they might claim for the properties themselves. The nominee had in fact benefited from the sale of the Black River properties. Many Indians would find that nominee holding was unreliable and full of pitfalls. Baboo accepted that he had to apply as a tenant. While Anwar Nagia of the District Six Trust had advised him to draw up an affidavit explaining the nature of their father's ownership, Baboo, who had already lodged his claim, was reluctant to pursue this route.

Fatima and Baboo, while acknowledging that the process has been very slow, are not prepared to grumble. Fatima explains her attitude:

My take is ... we lost it, na, whatever reason. The government of the day took it from us. Virtually took it from us. We never - I don't think anybody who has submitted a claim ever in their minds thought they would get it back. Right. Whichever way ... you know, it was a whole moan and groan affair going on there in the offices [the Commission's]. And you come here, you phone. ... I was one of them, OK. So they don't answer you. They say they going to phone you back and they never do. You got to make ten calls. You know. But afterwards I also gave it a thought you know. Forty years or thirty years ago my father lost what he lost you know for a pittance and here I never in my mind or nobody none of them even thought you would get come back to this where we could claim that.

She does have reason to complain but does not. After she lodged her claim for Windermere, she found a few more lots that should have been included in the claim. She was told verbally by a staff member at the Commission that it would be added to her file, but she later found that it had not been done. She has no case now - if she wants to contest the inclusion of the additional lots then she will have to take it to the Land Claims Court in Randburg. That would necessitate a lawyer and some expense so she has given up this line of action. Baboo was also not prepared to stress himself about the claims and took things as they came with patience.

And to what use will the settlement be put to? The family's closeness determines this. They will pool what they get, pay up all their debts (Baboo has to pay his son's university fees) and if anything is left over then each one will decide what to do with it. Baboo thought only fleetingly about taking land as an alternative.

I was thinking about it but then you must have excess money if you want to build. Say, you going to get the land ... then what you going to do if you haven't got money? According to their talk OK it was Black River they would have got somewhere near that vicinity. Now I'm trying to think now which is the nearest vicinity there which I don't - I can't - see any land around there you know. So I just left it. I didn't worry with that because the money is more important to me.

I ask Baboo what restitution has meant to him - does it finally lay the past to rest? I have to press him about four times over almost thirty minutes to get a definite answer. The first time I pose the question he notes that they sold each of their properties for R7 000 in 1969. He then launches into a long story which he had also told me in 1995 about how impossible it was to get a property in Rylands. Officials needed to be bribed and honest people like him without much money were unable to secure land. The second time I ask him the question he talks about the friends he had in Black River, the youth who would come into his garage and the games they would play - a life without apartheid. I did not quite hear him preface this with a soft answer that the settlement cannot really settle the past so I press him for a third time on what the settlement means. 'The answer to the question is that I miss that. I miss that. ' A fourth time I prod him further - perhaps too relentlessly. He finally says:

This means what can I now say. This is a little part of the settlement. That can't buy me ... money can't buy happiness. Peoples is gone. Living here, there and you can't go to each and every one. ... That whole community there. Whatever religion, whatever culture was one big happy family. One person gets sick, everybody's there to come and help. One person dies, everybody's there to help. That's how that community was. It was fantastic. This [he points to the letter of settlement] is just a small donation [he laughs]. ... I am grateful for that. ... I can pay whatever I can pay - finish now. Right. Whatever little bit that's left then I can get something through it and then we can just start all over again. But the memories of Black River will always remain.

In the course of the interview he tells a story of his youth. He and his friends would gather weekly at the bottom of Strathallan Road and weave their way through each of the streets of Park Road Estate making their way to the Rondebosch Common. Then, after a run around the Common, they would weave their way back down each street until they reached Strathallan. This is a tale of belonging, a tale of what was taken away. And each time Baboo drives down Klipfontein Road near the Red Cross Hospital his wife has to ask him to 'Look in front of you. My head is turned to the left looking over.'

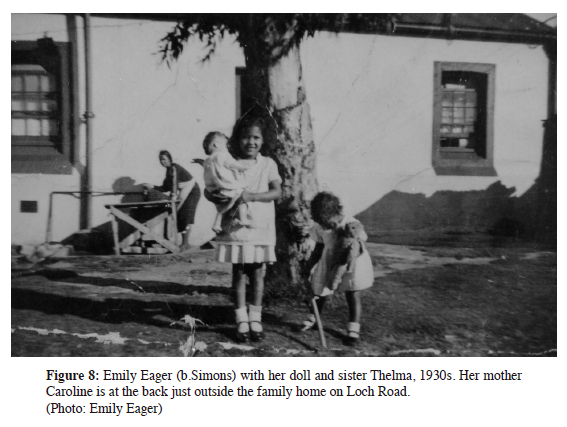

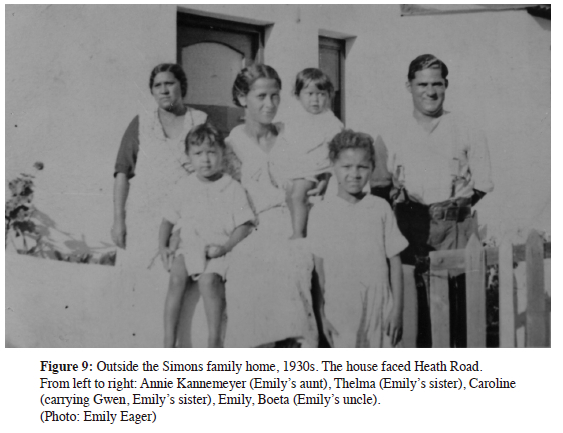

The money or the box24

Emily Eager (b. 1930) is seventy-six years old. She lives alone in Pinati but manages to get around to do some small shopping chores. Her link to Black River dates to the early years of the twentieth century when her grandfather Pete Simons, reputedly an African-American, stepped off a ship in Cape Town and never got back on. He married Emily Silberbauer at St Paul's Church in 1902 and then bought several properties in Loch Road. He eventually retained one house with four plots of adjoining land. The property stretched from Loch Road to Heath Road. He operated a horse-driven cabby service for residents of Rondebosch till his death in 1926; his wife worked as a char. Over the years, children were born and grandchildren too and soon other homes were built on the properties. Emily Eager is the daughter of William (Pete and Emily's son) and Caroline. William was a furniture polisher, Caroline worked as a char for Rondebosch families and once in her teens, Emily worked at a clothing factory. She remained in Black River after her marriage to Tommy Eager, a plasterer, whose parents had bought a home in 1928 in Loch Road. Black River was made up of many interconnected families.

When I visit Emily Eager I am struck by the very co-operative way the family has worked on their claim. Emily has direct knowledge of two claims - the one is for the Simons' property which she filled in for her deceased father and his siblings, one of whom was her aunt Annie (b.1912) who was alive at the time restitution was initiated. The other was lodged by Tommy Eager for his parents' home. Tommy has since passed away and Emily has asked his sister to take responsibility for attending to that claim. Her children will now get Tommy's share and Emily regards it as an Eager matter though she was a member of that household when they moved. While Emily herself did the research for the Simons claim, with time and with the running around required, this was getting too much and recently she has handed it over to her cousin, Jerry Kannemeyer (Annie's son), who is sixty-eight years old. They work well together sharing all their information with Emily giving advice about getting all the identity documents together in time.

The story they tell is of the long 'waiting period', faxes that were sent to the Commission but never reached the person they were intended for, poor communication, and, more seriously, lost files. The Commission lost her first file and she had to go and get affidavits to say that she had handed it in and re-research and resubmit all the information again. They know what the Eager claim will bring in - R60 000. This will be divided between the five children of the original owners. Since Tommy is deceased his share of R12 000 will be further divided between his two daughters. The Simons claim covers two erfs so it will bring in much more (R53 000 plus R68 000). It will have to be divided several times over. Pete and Emily Simons had five children all of whom are deceased and each share of R24 200 will be sub-divided amongst the next generation. Since William and Caroline had six children, Emily will get R4 033 - one-sixth of William's share. Jerry will get his mother Annie's full share since he is an only child. They had hoped, as the Commission had indicated, that the claim would be settled at the end of 2005.

Having received information about what money they will receive, they were surprised to be invited subsequently to a meeting at the Mowbray Town Hall where an inaudible presentation with inadequate technical equipment, was made by the Commission urging claimants to take land. They wondered what they were doing there. Neither of them are interested in land at their age. As Jerry says 'You got to take land where they want to give you land and you can't resell it .'25 Referring to the popular radio show of years gone when contestants were offered the money or a box with uncertain contents Emily has a good sense of humour: 'I said some day I will have to take the box - at the moment I want the money.' She laughs, yes, she is talking about 'the big box.' 'I want the money now. Because the box I will have to take eventually. I don't want the box.' She and Jerry are getting older and hope to enjoy the rewards of their claim while they can and for this reason the delay is frustrating. Emily hopes to use her share to visit her children in Canada though she realises that her share will cover just part of the fare. Jerry hopes to do some home improvements.

I find some parallels with how Emily talks about the meaning of restitution and how she once spoke about forced removals to me. In an interview about removals, she never once said how awful it was for her - instead she pointed out that she was young, could adapt easily and set up a new home. Yet that home the Simonses once had must have had deep emotional significance for her - she was born there. Now when asked about the meaning of restitution for her:

It would have meant a lot to ... our parents, I feel. It would have meant a lot. But this thing's being going on and on and the parents are all dead now. So the children's going to benefit from what the parent would have got, but I know it would have meant a lot because our parents and their parents struggled to get what they had. They went through the struggle, not us ... It would have been so nice if this had happened in their lifetime...

One can only hope that Emily's children do not have to say the same thing and that she gets her claim settled soon.

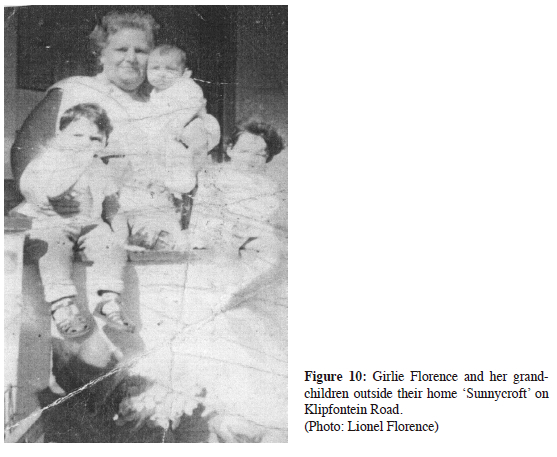

A cancelled sales agreement26

Magdalene Edith Florence was a white woman with both Dutch and Irish parentage. She had 'flaming red hair and piercing green eyes', in the words of her grandson, the internationally acclaimed musician Trevor Jones.27 Her husband, William Florence, was a driver for Garlicks, a department store in the city. He was classified coloured as were the six children. Mrs Florence, or Girlie as she was known, took the classification of her husband as the state determined. The marriage was a very tumultous one and William was peripheral in the lives of his children. Mrs Florence, three of her sons, and her married but separated daughter and her children came to live in a cottage called 'Sunnycroft' on Klipfontein Road. They first rented the place in 1952 but after five years entered into a sales agreement with the white owner ('Y'). The sale was made out in the names of three of her sons, one of them being Lionel Florence, who was but seventeen then and working for the city libraries. His father had to sign on his behalf. No property was registered in the Florence's name - 'Y' remained the owner and the family paid what they believed were payments towards final ownership. Thus they lived here till 1970 when they forced to move. In 1970 the lawyers acting for 'Y' concluded a memorandum of agreement of cancellation of sale with Lionel Florence and his sister (who reputedly had the power of attorney for the two other brothers who were in London). According to the agreement 'Y' refunded them R1350. Lionel would like it pointed out that Mrs Florence received this money. This cancelled sale made in the context of desperation at a time of forced removals is one that causes Lionel Florence much grief. In the context of restitution 'Y' has the status of owner.

Lionel Florence (b.1939) is sixty-seven year old and in a wheelchair due to one leg being amputated. When he made his claim for restitution he was able to walk and was in better health. Being so confined has not made him any less determined to pursue what he believes is his family's right and indeed his as one of the purchasers of the property. There are many questions one can ask about the sale. Could a white have sold to a coloured at that time? Inter-racial sales were not allowed except by permit. Did 'Y' dupe the Florences? The Florences believed they bought the house - at what point did they hope to get the title deed? They had paid Y's lawyers for well over thirteen years - this they believed was towards ownership of the house and not rent money. Mrs Florence was not well-educated and the family seems to have signed documents that they did not quite understand. Lionel says 'what we knew about buying of houses and the legal aspects of it left much to be desired because there was no question of transfers and the registration... It was direct payment from us, what we earned, to Y's lawyer's every month.' He signed the cancellation agreement in a hurry during a break from work and it wasn't explained to him.

Lionel has many battles to fight with his claim. His claim has been accepted as valid by the Commission, but he insists he is claiming as an owner and not as a tenant and has had to secure legal assistance from the Legal Resources Centre. Then he has also decided that he wants the land back. A quarter portion of what used to be 'Sunnycroft' in his assessment, lies as a vacant plot and is owned by the City Council. It is zoned for business. Council did buy up land along Klipfontein Road and certainly bought 'Sunnycroft' but from 'Y'. Lionel knows what 'Y' received for this property. Council does not recognise that Lionel has a valid claim in terms of restitution as the property, in any case, was needed for road construction. What Lionel wants as restitution is that portion of land that remains or land with business rights elsewhere in Cape Town to the same current value as the property in Rondebosch. He is not interested in financial compensation. He is doing this for his children and grandchildren and for his mother's memory. Lionel is passionate about his rights and what was lost - he is writing a memoir at the moment and who knows how this very complex story will work out.

A ceiling, Mandela's gift and two jokes

And what of the three men who took a leadership role? Ghamza, when interviewed again by me this year, was seventy-six years old.28 In 1999 he suffered a stroke but he began a slow period of recovery. I was expecting the worst when I went to see him because it had been impossible to see him for several days because he sleeps for long hours in the morning. When I see him at his son's home in Ottery, I am pleasantly surprised - he looks remarkably good and he still has the typical Adams sense of humour that I have got to know well. He attributes his recovery to his sports background. He was - he proudly shows me a picture - a member of the Western Province Rugby Club in 1956. Ghamza also has all his documents in a file including the plans of their home in Roseland Road. Two letters dated 2001 in the file point to him trying to get a response to his then six-year old claim from the commission. He presses them in the letters for 'a good answer', 'an amicable reply'. He received no reply to these letters. However, in 2005, his claim was settled.

Ghamza tells me how he and his siblings went to collect their cheques from the Commission's office in 2005. They received around R40 000 which was divided amongst the eight of them so that each received a cheque of about R5 000. One share of R5 000 was divided amongst the children of a deceased brother - each of his children got R800.

We went straight from the office of the Land Claim there in Strand Street. They gave us the cheque and said you can go and cash our money now by Absa Bank - Adderley Street. From there we went to the District Six Museum. So they had a corner there ... Black River was a corner. So we said to the people there 'We got our money today.' So this girl there took a photo of us. Now my one brother - I don't know if it is the first time he had R 5000 in his hand ... [he] was so excited now. 'Ya I got my money.' So they said to him open up the R 5 000 like a fan .

There was a photo of me [on display] standing with a horse ... I saw yes but it's me here.

This little story is a very moving one. The Black River exhibit in the museum that Ghamza went to see had been put up in 2005 after I had donated all the Black River photographs I had collected from residents to the museum. It formed part of the Two Rivers Project of the museum. Rashaad Adams had generously given me many of the Adams family photographs and thus Ghamza came to see himself there that day. It speaks to the importance of the District Six Museum in the lives of the once dispossessed people of Cape Town. Its reach goes well beyond the former residents of District Six and it provides validation. As exhibits go up the museum becomes symbolic of the homes and lives that people lost.

This seemed like a happy day, but I now probe Ghamza about what restitution has meant to him and has justice been done? He explains that when he first made his claim he had some hope of getting the house back but soon realised that this would be 'a long story' and his brothers advised that they should opt for the money. The sum per sibling is small. Ghamza tells how his brother cracked a joke with the Commission's staff that he was going to buy a Mercedes that day. He points out that they got R11 000 for their home in the 1960s which was little. Today, the houses in the area are going for R800 000 to R900 000. He says with no hesitation 'I think justice wasn't done'. He recalls all their years in Black River and how his family had decided to build in Roseland Road. He and his brother personally dug out the trenches to lay the foundation and with their hands pulled out rocks and stones. But Ghamza is understanding: 'You can't grumble grumble about that because at least the ANC gave us - I mean - made some of it right.' The ceiling of his son's newly constructed house now reflects the history of the Adams family's life in Black River - for that is how he used his R 5 000. We both laugh as I say 'So Black River is now in your ceiling.' But as I gather my up tape recorder and file to leave, he shows me a photograph of the Pirates Cricket Club and he points out the predominance of the Adams family in the team. Just over a month after this interview, Ghamza passed away.

Ebrahim Osman is in for a long haul with the Commission. He is now 73 years old. He and his wife have a busy day looking after two toddlers, their grandchildren. Ebrahim is a soft-spoken gentle man who is well-informed about land matters in the city, not surprising since he has been a builder all his life. Restitution has not been an easy route. His father had died in Black River before they had to move out and his mother decided that the property should go to the eldest daughter. But Ebrahim explains that women could not own property so a few years before the area was proclaimed, their home was registered in the sister's husband's name. It reflects as a deed of sale from one owner to another. He and his siblings, however, continued to live in the house until the area was proclaimed and the house sold.

In Ebrahim's mind the Osmans were the real owners of the property but he is unable to claim as owner (as he found out some time after he lodged his claim) because his brother-in-law lodged a claim for the property. He then had to claim for his siblings as tenants in the house since they all contributed a monthly sum towards the house. There was potential for conflict here, but Ebrahim is a very balanced individual. They do not have a legal leg to stand on to claim as owners and he thinks of all the young children of the family should they have quarrelled about the claim. He did receive a shock in 2004 though when the Commission informed them that their claim was not valid since the property was transferred from Yusuf Osman's name to another (the brother-in-law) before Black River was proclaimed. Ebrahim had to hire a lawyer to write a letter explaining the nature of the transfer of ownership and the fact that they were claiming as tenants. His claim has been re-instated. He would like each of the siblings to be treated as individual claimants, but this is unlikely. The settlement will have to be divided amongst six of them. Ebrahim has opted to go for land even though this will take time - he is hopeful that the Commission and City Council and other role players will identify land soon.

You know Una [Uma] as you say it's ten years on and a lot of things has changed and ... so I decided at that point in time that land is a better option. At least you know our President Mandela who gave us something, at least ... let's make it worth it what he's giving us. From my side I feel quite optimistic now.. .29

Abou Desai's claim should have been a fairly simple one to settle. He was the owner of the house at the time of the removals and he is the sole claimant. He is now 75 years old. He is in good health (though he has a bit of a stoop since I last interviewed him). He can still drive to the city though he parks quite far from the Commission's offices and has to walk. It is frustrating that other people's claims have been settled, but not his, and particularly that these claimants are younger than he is. He tries to work out what logic the Commission pursues in processing claims but has failed. He is D180, another claimant D179 has been settled. The way Desai tells his story of restitution is fascinating to me. I had already done an analysis of his story of removals and in an article I had concluded that he tended to tell jokes about officialdom because it was his way of maintaining his dignity in a situation which was humiliating.30 I am surprised to find that once again he tells jokes about the restitution process and finds officialdom absurd. There are at least two examples given in a relatively short interview.31

I spoke to one to one of the operatives one day and he said to me very nicely. He said 'Mr Desai, let me just explain to you how this thing works' and half way through his explaining he just burst out in laughter because the whole thing was so ridiculous and the two of us had a jolly good laugh over it. And I had said to him at the time while I have you I want to give you a change of address and he said to me 'Are you moving?' 'No, I'm not moving but you take this change of address', I said. 'Instead of .... you have this alternative address. Plot No. So and So, Vygekraal Cemetery.' (he laughs)

He has sympathy for the young staff - one of them was in grade seven when he lodged his claim and since then passed her matric and got a job at the Commission. He understands that they work under difficult constraints. They are good to him on the whole. He explains why he has been able to maintain a sense of balance through the years:

So oh its hilarious and why I've been able to survive because of the attitude of the clerks in the department. This fellow said to me 'You know, Mr Desai what'll happen is your forms will go to Pretoria. That will go into the in-tray. And then three months later somebody else's forms will come in and they will go on top of yours' (Desai laughs). He says 'And a month later somebody else's forms will come in and will go on top of that.'

Behind these stories is a lot of frustration and he admits some 'anger'. The interview ends as he has to go and fetch a grandson in one of the worst days of Cape Town's winter. The wind gusts wildly and the rain pours and he is gone.

Conclusion

The above stories are drawn from owners (although some had to claim as tenants). This is not by design but is a reflection of the fact that it is predominantly the owners in Black River who have applied for restitution. An explanation for this lies in the history of the community at the time of removals. Leadership then emerged from the owners and a strategy of the BRRA was to emphasise the middle-class property owning residents. Tenants (and there were several poor working class families especially in Fraserdale Estate and at the bottom of Strathallan Road) were a bit retiring as they too felt that the calamity was worse for the owners. A small percentage attended the BRRA meetings though they had been informed of these. One important reason too for the apathy was that many tenants along Klipfontein Road were affected not only by Group Areas but by the City Council's road widening plan. Had leadership emerged from the tenants then they would have been prominent in restitution.

All credit goes to Ghamza Adams and Ebrahim Adams they tried to publicise the restitution meeting in 1996 as widely as possible. Mervyn Hermans who grew up poor in Black River was one of the tenants who did come to the meeting. Yet he did not apply for restitution. When I recently asked him why he had not - he reflects that he did not think he stood a chance as he was only a tenant. He also was not sure whether his rented cottage was expropriated by the Council for the bridge over Klipfontein Road or not (if so he would not have been eligible to claim since expropriations for road constructions fall outside the ambit of the Commission). He thinks now that it was not affected. He has just a niggling doubt about whether he should have applied and wistfully asks me if I thought he would have stood a chance. He notes he even had proof of residence since he still has a first day stamp he once posted to his home in Loch Road. Yet Mervyn is not unduly perturbed by not applying. He makes an important point - he refers to the evening at the District Six Museum in 2005 when Black River residents came together with other families from Claremont and other places to look at the Two Rivers Project exhibition and talked about the past. He stood up and spoke about his life in Black River and signed the now famous length of cloth. 'What I said there that day made me feel better ... That was it. Keep your claim.'32 This is an example of how healing and reconciliation can take place outside government-determined parameters.

Mervyn is one of the better off former tenants. He has made a success of his life through hard work and managed to escape the harshness of Manenberg and lives fairly comfortably in Welcome Estate. He is also semi-retired and supplies various supermarkets with vegetables. Others on the Cape Flats - many former tenants of Black River went to Manenberg - have not been so fortunate. The few I know remain poor with many an unemployed family member. Although the Land Claims Commission did put an instruction guide out to ex-tenants, restitution has failed those who may have needed it the most. The process requires some level of literacy and if the lower and middle-classes have expended so much time, energy and money travelling to the commission, those on the economic margins cannot afford such luxury. Andries du Toit has made the point that one of the central goals of restitution should be poverty alleviation but that restitution carries the danger of rewarding the elites.33 Restitution in the case of Black River has indeed not been about poverty alleviation - though it has and will help an embattled lower middle class to improve their lives in the short term.

Restitution in Black River has not been about reshaping the spatial patterns of the past or about reintegration. It has been fundamentally about financial compensation. Seeking alternative land is not an option many would favour as it will delay settlement. People are also unsure where the land will be. Land complicates a settlement amongst family members and some capital is required to make that option work. In a very important and detailed study of the impact of cash compensation in Knysna and Riebeeck-Kasteel, Anna Bohlin concludes that 'money, as a relatively empty signifier, is invested with meanings in creative and open-ended ways, often becoming about "home" and "belonging"'. This is particularly in the case of Knysna where claimants who had but a marginal existence in the town have invested their money in upgrading informal homes - transforming these into solid permanent structures with improved interiors. In one case a cupboard is given meaning and history is attached to it: 'there is the money'.34 This study of Black River is by no means as comprehensive as Bohlin's but it does point to how with the division of money into such small amounts the danger is that the money will carry but a temporary and relatively insignificant meaning. 'Mandela's gift' would also have been more valued had it come sooner. For Mona Dawood, the money is a sign of the failure of restitution.

Restitution was meant to heal the nation but one consequence has been its impact on families. While some of the above tales have pointed to the very co-operative way in which family members have worked together, other families have been divided. We have seen how from just a small number of stories how land ownership was not as simple as one would assume it should have been. There are many potential sources of conflict. To avoid further disputes the Commission now issues cheques to each deserving descendant instead of making out a lump sum. Two individuals I interviewed and whom I shall not name have had a lot of suspicions about each other. They dispute who are the actual owners of the house, who contributed to the house payments, and thus who deserves a greater share in restitution. The tale is a messy one. When the one finds out that the other has claimed he/she resorts to various means to get incorporated into the claim. The one tells about the other getting illegal and fraudulent access to the file in the Commission's office. After a meeting at the Commission's office there is a breakthrough about how shares will be divided. A new cause for tension emerges, however. They disagree about whether to take alternate land or the money. One has sympathy with both of them - their animosity which restitution brought to the surface was rooted in their childhood and removals accentuated that. Both tell stories of being let down by the other at the time of removals. Divided at the time of removals, they remain divided in the restitution process and neither is in good health.

If restitution is about justice - then we have seen how claimants know now that justice cannot be done. Some have reconciled themselves to that, others not. When people applied there was, for many, a romantic engagement with the Commission - it served to acknowledge that the past had been unkind, that rights had been violated. Restitution entailed 'making a statement' about that.35 As time went on and claims had to be resolved, restitution came to be very specifically about the end result - in the urban case this is about money. The delay in processing claims and the inability of the Commission to present itself as an efficient agent has seriously lessened the impact that restitution could have had.

Du Toit has also argued that restitution is a door that leads directly to revisiting the past: 'to lodge a claim is ... to re-awaken those old ghosts and open half-healed wounds'.36 In the interviews with Black River residents there is a sense that at the time of engaging with the lodging of the process the past was recalled in a fairly happy way - their lives, homes, activities. They recreated/rediscovered family histories. More importantly, they connected to the city as they sought to lodge their claim. They narrated their loss with the understanding that it would be redressed. With the settlement, as some of these few stories reveal, the loss has become even more real. It has not resulted in what Du Toit anticipated, namely, a feeling of the 'loss of the loss'.37 In almost every interview here the restitution narrative has been accompanied by the removals narrative. In terms of how people tell stories there is a startling similarity especially in the case of Desai and Eager. Both use humour to deal with a loss and with the lowness/inefficiency of the commission. The way they told stories of removals is replicated in how they now tell stories about restitution. Baboo Mohamed will continue to look at what was Black River every time he drives along Klipfontein Road and Ghamza Adams, till the last, took out his pictures of the Pirates Cricket Club. The Commission's office in Strand Street has taken on the face of officialdom and bureaucracy and represents, for many, a new struggle.

Reconciliation appears in a very limited form in these stories of restitution. Current owners of property of the dispossessed are not challenged by the land claims process. There must have been some uneasiness in early days as claims were gazetted and owners were identified and informed that there was a claim on their property. The current owners are by no means the ones who benefited from the sales in the 1960s and 1970s. Yet one feels more could have been done and it can still be done. The dispossession of the Black River residents, while acknowledged by the District Six Museum, needs a bigger acknowledgement - by residents of Rondebosch. The silence in Rondebosch and the erasure of this community has to be addressed. There may be peace in the hearts of Black River residents,

I believe, if Rondebosch acknowledges - you were here, you helped develop this neighbourhood, your properties are now worth a fortune, you are hurt and we are sorry. How can we pay tribute to your history? The national government has done its bit with the resources at hand, but local councils and local residents have not done nearly enough. Memorialisation of this history may bring reconciliation and healing.

* I would like to dedicate this article to all the remarkable Black River people I have got to know and appreciate over the last decade and more. They are wonderful story-tellers, full of humour and are generous with their time. Every visit humbles me. All names have been used here with their express permission. It is with especial sadness that I have learnt, as this article is prepared for publication, that Ghamza Adams had died. I count myself privileged to have met him and interviewed him. This article was originally presented as a paper to the Conference on Land, Memory, Reconstruction and Justice: Perspectives on Land Restitution in South Africa, Grabouw, 13-15 September 2006.

1 Ghamza Adams Papers (privately held), Register of meeting for restitution. This seems to be a composite list of two meetings and totals eighty-five people. The first meeting preceded this one by two weeks.

2 The paper was titled 'Swallowing the gnat after the camel: the Fraserdale/Black River group areas proclamation of 1966 in Rondebosch', South African Historical Society Conference, Rhodes University, July 1995.

3 Interview Aziza Pangarker (b. Mohamed, 1944), 1 May 1995.

4 I have since written a full manuscript on this history titled 'Dispossession in Black River, Rondebosch: The Unfolding of the Group Areas Act in Cape Town' and will be revising it for publication.

5 Interview Ghamza Adams and Ebrahim Osman, 10 March 1997.

6 Interview Ghamza Adams, 23 August 2006.

7 Interview Abou Desai, 11 August 2006.

8 'The Truth and Reconciliation Commission and the Commission on Restitution of Land Rights: Some Comparative Thoughts', presented to Conference on the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, History Workshop, 11-14 June 1999; U. Mesthrie, 'Land Restitution in Cape Town: Public Displays and Private Meanings', Kronos, vol. 25, Nov. 1998, 239-58.

9 D. Mayson, 'Land restitution in the new South Africa', unpublished paper, SPP, August 1996 and R.M.Levin, 'Politics and land reform in the Northern Province: a case study of the Mojapelo land claim' in M. Lipton , F. Ellis and M. Lipton (eds), Land, labour and livelihoods in rural South Africa: vol 2 (Pietermaritzburg: Indicator Press, 1998).

10 M. Brown, J. Erasmus, R. Kingwill, C. Murray and M. Roodt, Land Restitution in South Africa: A Long Way Home (Cape Town: Idasa, 1991).

11 Interview Ghamza Adams and Ebrahim Osman, 10 March 1997.

12 Hansard, 1994, no.14, cols 3991-2, 3995.

13 The Argus, 17 February 1996.

14 It is possible that because there were many property owners at the meeting and also that a possibility of a return to the land was in fact not possible that claims were lodged individually. Ebrahim Osman however says that they did not know enough about a group claim. (Interview Osman, 8 August 2006)

15 Research is still at a preliminary stage and it hoped to obtain information from the commission about how many claims were lodged for Black River as owners and as tenants.

16 See C. Walker, 'Urban Restitution', Paper presented Pretoria, 2003, 5, 12. While Walker points to how the statistics are problematic, the weight of the urban claims is not in dispute.

17 Ibid., 10-11.

18 Interview with Mona Dawood, 16 August 2006.

19 The media covered the issue by focussing on the residents of the middle class homes. See Cape Times, 6 April 1961.

20 Interview Rashaad Adams, 2 May 1995.

21 In 1964 the residents hired L. Dison who had made his name taking on several group areas cases. They all contributed one pound each to meet his fee which was quite high. He helped them draft their memorandum and accompanied them to the hearing.

22 This story draws on an interview with Baboo Mohamed, 19 August 2006 and Fatima Mohamed, 16 August 2006. The history of their stay in Black River draws on an earlier interview I had with them on 16 November 1995.

23 From 30 March 1951 the Cape Province became a controlled area under the Group Areas Act. This was meant to freeze the status quo in terms of the racial ownership of property pending the declaration of group areas.

24 Interview with Emily Eager and Jerry Kannemeyer, 13 August 2006. The history of their stay in Black River is drawn from my earlier interview with Emily on 8 May 1995.

25 They would not be able to sell for ten years.

26 This is based on an interview with Lionel Florence, 17 August 2006 and written information he has including the cancelled deed of sale.

27 See Cape Argus, 9 April 1997 (lifestyle section).

28 Interview, 23 August 2006.

29 Interview Ebrahim Osman, 8 August 2006.

30 U. Dhupelia-Mesthrie, 'Dispossession and Memory: The Black River Community of Cape Town', Oral History, vol. 28(2), Autumn 2000, 42.

31 Interview Abou Desai, 11 August 2006.

32 Telephone conversation with Mervyn Hermans, 14 August 2006.

33 A. du Toit, 'The end of restitution: getting real about land claims' in B. Cousins (ed.), At the crossroads: land and agrarian reform in South Africa into the 21st c entury (Plaas, School of Government, UWC and NLC, 2000), 76,79.

34 A. Bohlin,'A price on the past: cash as compensation in South African land restitution', Paper to Ten Years of Democracy Conference, UNISA, 2004, 8,14.

35 Interview with Anne Ntebe, a former resident of Protea Village, 6 May 1997 quoted in Mesthrie, 'Land Restitution in Cape Town', 256.

36 Du Toit, "The end of restitution', 81. Bohlin also in a slightly different way looks at how money does not bring 'closure ' and instead succeeds in 'opening up the past ' ('A price on the past', 10).

37 Du Toit, The end of restitution', 82. He adopts this phrase from Slavoj Zizek and employs it to discuss what would happen if there was a return to the land. People may realise they 'never had what we thought we lost'.