Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Kronos

On-line version ISSN 2309-9585

Print version ISSN 0259-0190

Kronos vol.32 n.1 Cape Town 2006

ARTICLES

Constituting Community: The Contested Rural Land Claim of the Tsitsikamma 'Fingo/Mfengu' and Clarkson Moravian Mission in South Africa

Crystal Jannecke

Centre for Humanities Research, University of the Western Cape

Introduction1

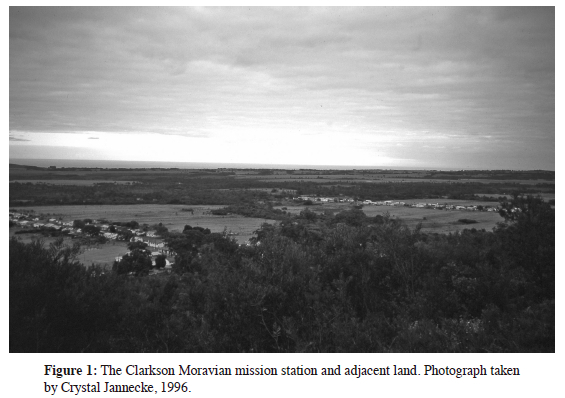

A group calling itself the Tsitsikamma 'Fingo/Mfengu' community lodged a land claim against the Moravian Church in 1991. They demanded the Church's return of the Clarkson Moravian Mission land held since the 1830s on behalf of and in trust for the 'Fingoes'. In effect, the claim recalled a land tenure arrangement set in place by British colonial authorities during the 1800s. The Clarkson land restitution case is indeed special for there is no history of forced removals from the mission land. The State is as a result not the apparent transgressor. The claiming 'Fingo/Mfengu' communities had resided on land adjacent to Clarkson prior to being dispossessed of their land by the State in 1977 and resettled at Elukhanyweni in the Keiskammahoek district of the Ciskei. The mission station residents, however, remained in possession of land in the Tsitsikamma.

Land is an important resource to access, occupy, control and own. The land of the Clarkson Moravian mission station presented opportunities for the development of low cost housing for those previously removed from the Tsitsikamma who wished to return to it. Even more significant is the use of land as a symbol of belonging, functioning discursively to justify and legitimate claims of entitlement. It is around such symbolic meanings in rural land restitution claims that members of community are mobilized, racial and ethnic identities articulated, and contemporary communities formed. This article explores how an inclusive demand for the restoration of dispossessed 'Fingo/Mfengu ancestral land' in the Tsitsikamma included the Clarkson Moravian mission land, but excluded its residing mission community. I argue that by functioning discursively as the central place of return to the Tsitsikamma, the Clarkson mission land symbolically marks the boundary against which a contemporary ethnic Tsitsikamma 'Fingo/Mfengu' community is formed. In its exclusion from sharing 'ancestral' rights in the Clarkson land, the residing mission community is constructed as the 'constitutive outside' aimed at legitimating 'Fingo/Mfengu' communal entitlement to the mission land.

I begin by contextualising the Clarkson Moravian mission land claim. I thereafter discuss representations of community in contemporary South African rural land restitution land claims. Some elements of unity in both the 'Fingo/Mfengu' and Moravian mission communal identities are briefly considered. I then examine the unfolding negotiations with a focus on representation and the articulation of an ethnic identity against a constructed constitutive outside.

Contextualising the Clarkson Moravian Mission Land Claim

The Clarkson land restitution case is significant in that the process of taking up the lodged claim preceded the laws and policies introduced after April 1994 to regulate, validate, and standardize procedures to be followed in land restitution claims. In retrospect, the Clarkson case is technically invalid in terms of the 1994 Restitution of Land Rights Act since the claim pre-dated the 1913 Natives Land Act. Furthermore, it did not involve the particular set of historic dispossessions outlined and addressed in the Restitution of Land Rights Act of 1994. The claim itself highlights the contemporary mobilization and formation of rural communities based on racial and ethnic identities drawn on, as they are, to strengthen community formations and declarations of entitlement to land.

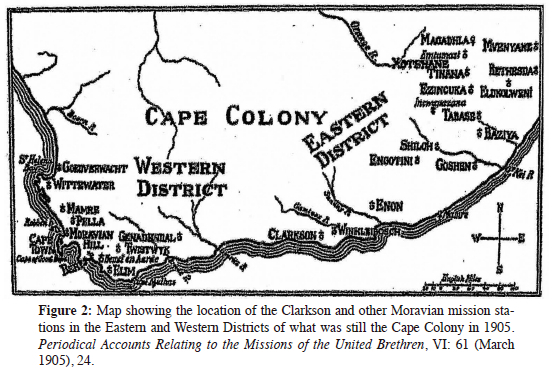

It was in 1839 that the Clarkson mission station was first established on a portion of the Koksbosch farm. British colonial authorities requested the Moravian Mission Society to pursue its missionary activities among the 'Fingo/Mfengu' residing on land alongside and adjacent to the mission station. From the outset the mission station was open to all the people designated at the time as 'Fingo' as well as those now referred to as Khoikhoi or Khoisan and freed slaves, subject to their acceptance of Moravian missionary authority. The 'Fingo' who entered the mission by accepting the missionaries' authority became members of the Clarkson Moravian mission community. By 1851 a colonial Deed of Grant was issued bequeathing the entire Koksbosch farm to the Moravian Mission Society. This farm was renamed Clarkson and the land was granted to the Moravian Mission Society which held it on behalf of and in trust for the 'Fingo' residing there. Members at the mission station grew. Participation in Moravian rituals, conformance with the mission station's spatial landscape, and compliance with the mission's order and governance set the Clarksoners apart. Those who did not remain on the mission, and were on land adjacent to it, retained the pre-designation of 'Fingo/ Mfengu'. The 'Fingo/Mfengu' who resided on the mission land became included as Moravian Clarksoners, while those on the adjacent land held on to the 'Fingo/ Mfengu' classification. During the State's apartheid era this generated difference incorporated elements of official racial and ethnic discourses. Thus when the mission residents of Clarkson were officially classified as a 'coloured' racial group during the 1950s, it was represented as having no significant connection to the official designated ethnic groups of 'Fingo/Mfengu' neighbouring the Clarksoners in the Tsitsikamma. Any apparent and celebrated connection defied the very logic of apartheid. The forced removal of the adjacent communities at Wittekleibosch, Snyklip, and Doriskraal in 1977 from the Tsitsikamma to the distant Elukhanyweni at Keiskammahoek in the Ciskei reinforced perceptions that Tsitsikamma communities with differing racial and ethnic classifications shared no historical connection. Despite this nuanced and complex relationship among the Tsitsikamma people, in the 1990s its representative organization called the Tsitsikamma Exile Association (Fingo) or TEA (Fingo) demanded that the mission land be returned to its original owners since the Moravian Church had been holding it in trust for and on behalf of the Tsitsikamma 'Fingo/Mfengu'.

Unlike their 'Fingo/Mfengu' neighbours, the Clarkson Moravian mission community was not dispossessed of land in 1977. The racial classification of the mission community in relation to the land it occupied provided the legal protection that left the Clarksoners in undisturbed occupation of the mission land. Being a Clarksoner during the time of apartheid upheaval certainly afforded individual protection, security, and perpetuity in their right of access to, and use of, the mission land. No doubt, this strengthened the Clarkson Moravian mission community's attachment to the land they occupied. For the 'Fingo/Mfengu' people the trauma of dispossession and forced resettlement elsewhere served to intensify their attachment to 'our land' in the Tsitsikamma in both material and symbolic ways. However, in retrospect it is clear that the Clarksoners' relatively privileged experience under apartheid served in some ways to delegitimise their claim to the mission land, if not in the eyes of the Clarksoners themselves, then certainly in the eyes of others including the Tsitsikamma 'Fingo/Mfengu'.

Members of the mission station remained in possession of land despite the inclusion of Clarkson and its associated Charlottenburg farm in the government's 1936 list of released areas for 'native' occupation.2 Following the State's reclassification of Clarkson as a 'coloured' mission station during the 1950s, ownership rights in land shifted away from the South African Development Land Trust to be vested in the independent local Moravian Church (Western Cape).3 However, the Clarksoners lost access to and use of the commonage land they had shared with their neighbouring 'Fingo/Mfengu' communities when dispossessed by the State.4 With restricted land use options, the cultivated gardens in Clarkson soon became fodder for cattle and other livestock. The mission station's agricultural land also remained largely inaccessible to local Clarksoners since the now independent Moravian Church (Western Cape), also known then as the Evangeliese Broederkerk in die Westelike Provinsie, had leased out portions thereof to various racially classified 'white' farmers.5 The annual rental was payable to the Provincial Board of the Moravian Church (Western Cape) and not to the Clarkson mission community. Moreover, the construction of the extended national road in the early 1980s effectively prevented the Clarksoner mission community from continued 'unlawful' use of the commonage land.6 The Clarkson Moravian mission community for the most part did not suffer the complete disruption of land dispossession and forced removals like their 'Fingo/Mfengu' neighbours. However, the dispossessions had a negative impact on them in both direct and indirect ways.

The Clarkson mission land formed part of a larger demand for the restoration of land rights in the Tsitsikamma. Separate from the Clarkson land claim was the demand for the return of Tsitsikamma land dispossessed by the apartheid state in 1977. The Moravian Church and state directed land claims, while pursued separately, overlapped in unfolding processes of community formation. In terms of the state directed land claim, the Tsistikamma 'Fingo/Mfengu' community demanded the return of 'ancestral land' which its members had resided on since 1837. Groups designated as 'Fingo' by British colonial authorities received land grants for services rendered to the colony during the 1835 Eastern Cape frontier war. Land allocations regularly positioned the designated 'Fingo' as intermediaries on the Eastern Cape frontier as well as locations of labour from which to supply the demands of colonists. The escort of groups of 'Fingo/Mfengu' by British colonial officials to the Tsitsikamma in 1837 was in response to requests made by some colonial farmers from the wider Uitenhage district for a suitable supply of 'Fingo' labourers.7 These groups of colonial designated 'Fingo' were settled at Palmiet River, Wittekleibosch, Snyklip, Doriskraal and at Koksbosch (later renamed Clarkson). In this land claim, the state returned about 8000 hectares of land on 25 March 1994, one month before South Africa's first national democratic election.8 However this prime agricultural dairy farm land was immediately leased back to its previous officially classified 'white' farm owners who had purchased the dispossessed land from the State during the 1980s. The inaccessibility of this state-restored land to ordinary Tsitsikamma 'Fingo/Mfengu' community members shifted the focus of consultation with the Moravian Church. The focal point in negotiations with the Church began to alter from calls for cooperation and support from the Church to defining Clarkson as the place of return for the 'Fingo/Mfengu' to the Tsitsikamma.

Representations of Community in Contemporary Rural Land Restitution Claims

There is much written on land restitution in South Africa and its associated poli-cies.9 I am interested in exploring the problematic of community and the articulation of identity in restitution processes, more particularly of the Clarkson Moravian mission land. In general, perceptions of community have largely taken for granted the condition of belonging in which individuals come to see themselves as members of a collectivity.10 A key difficulty in the current South African land reform process relates to the conception of community within government policy and implementation programmes. NGO workers and government officials regularly take community to be a unified, organic and harmonious unit.11 Often this unified community presents itself as comprising of members with a shared set of interests and goals.12 Deborah James, in her South African case study of the Doornkop farm, points out that populist ideas of 'the people' and 'the community' underestimate the importance of engaging with manifestations of power among groups targeted for development initiatives after having had their rights in land restored.13 Stuart Hall notes that whether at local or national levels community continues to be represented as unified with their communal identities expressed as being 'one people'. The assumption here is that this is rooted in some organic unity such as that of ethnicity,14 which commonly refers to a shared set of cultural features like language, religion, custom, traditions, and feelings for place.15

Once we no longer take racial and ethnic categories for granted as fixed entities, the objective of investigation shifts to interpreting critically the dynamic changing history and politics surrounding communities contesting claims of entitlement to land. Such an interpretation takes into consideration the discursive symbols used to legitimate the power exercised to justify and validate the historical accuracy of the land claimed. Henry Bernstein reflected on the way in which community has re-emerged in the contemporary South African land restitution process in which numerous contemporary rival groups are claiming a prior or superior right to the same portion of land. He argues that such re-emerging contemporary communities are both powerful and contradictory, having their public collectivities imposed, recognized, as well as owned with ethnicity being a common factor in many contested land restitution claims.16 Communities, however, are seldom unified under any one set of descriptions. According to Stuart Hall, a range of differentiated cultural features can be utilised as symbolic markers to set discursively constituted ethnic communities apart.17 The social identity of communities should not be read through an essentialist or primordial approach, but rather as discursive objects constructed in or through difference and constantly destabilised by what it leaves out.18 In general, contemporary land restitution claims regularly include categories of racial and ethnic differentiation. Appropriated from prior dominant colonial and apartheid discourses, these designations appear in processes of community identification, as in the case of the labeled 'coloured' mission residents of Clarkson as against the ethnic designated Tsitsikamma 'Fingo/Mfengu'. Yet these are not to be taken at face value, more so when drawn upon to 'hail subjects into place' in discursive community formations linked to contested land claims.19

The construction of community is thus about creating conditions of belonging so that individuals come to see themselves as members of a collectivity. The problematic of representation in contemporary community formations in South Africa linked to land claims arises when colonial and/or apartheid constructions of racial or ethnic classification are used and reformulated into contemporary land restoration narratives.20 In such community formations culture functions as a source of meaning, a focus of identification, and a system of representation. It is through selected memories of the past, the desire to live together, to belong, and to perpetuate a communal heritage that a community's social identity is imagined and discursively constituted.21 Benedict Anderson relies on the distinction between local, concrete, face-to-face communities and the more abstract, mass, anonymous collectivities in his seminal work on the nation as an 'imagined community'. Anderson argues that the difference between nations and local communities lies in the different ways in which their communal identities are imagined and constructed.22

An underlying theoretical issue is whether to consider the ideological function of representational strategies used in constructions of communal identities. This depends on the specific conceptualisation of ideology. The theoretical literature can be characterised in terms of a distinction between a critical concept of ideology, derived from the Marxist tradition, and a neutral concept of ideology, associated with American social and behavioural science.23 In John Thompson's critical conceptualisation of ideological discourse, meaning is mobilised to serve and sustain the interests of domination of the ruling class.24 In this account, the use of much the same representational strategies serving the purposes of individual and collective emancipation would not be ideological, since it is not aimed at establishing and maintaining ruling class domination.25 In this regard, the ethnic Tsitsikamma 'Fingo/Mfengu' discourse of the 1990s would count as non-ideological. In applying these concepts, it is helpful to use a critical interpretation to non-ideological as well as ideological discourses with an accompanying awareness that these form part of a 'single field of inquiry'.26

A similar complication relates to the politics of exclusion as the inevitable counterpart in processes of identification in community formations.27 As a process of articulation, identification operates across difference and entails the discursive work of marking and binding symbolic boundaries that involve recognition, connection, and association. Constructed in this way, identification following Stuart Hall creates an allegiance or an association, establishing a marked symbolic boundary and a natural closure of solidarity.28 The binding and connectedness of the contemporary Tsitsikamma 'Fingo/Mfengu' community, produced through such a process of identification was naturalised and commonly perceived as constituting a unity that comprised of an inclusive sameness with no internal differentiation. Yet this communal unity with its internal homogeneity, which the process of identification treats as foundational, was actually a constructed and naturalised form of closure against which the Clarkson mission community was marked as the 'constitutive outside'. Identification requires this symbolic boundary in relation not only to what is included, but also in relation to what is left outside.29 The discrepancies between the discursive unity of communal identity, as against the differentiated nature of the actual collectivity and what it excludes, certainly have important political and social consequences.

Elements of Unity when Considering Communal Identity

The Clarkson Moravian mission community was utilised as a symbolic marker against which to recognise and associate with a constructed contemporary ethnic Tsitsikamma 'Fingo/Mfengu' identity. A brief reflection on the story around which an inclusive sameness was constructed is useful. Tsitsikamma 'Fingo/Mfengu' demands for land restoration regularly referred to a history that pre-dated the Mfec-ane.30 The early 1990s demand for the return of 'ancestral land' represented the Tsitsikamma 'Fingo/Mfengu' as having a longstanding relation with the Tsitsikamma land, including Clarkson. Such primordial perceptions linking community with land strengthened, following their forced relocation from the Tsitsikamma. Yet their historical relation to the land remains as recent as that of the Clarksoners, and dates back to the 1830s. The actual origins and functions of the 'Fingo/Mfengu' as an intermediary group is a matter of considerable debate within South African historiography. Some historians present the common and fairly well-known view on the origins of the 'Fingo' as named in the colonial record.31 More recently other scholars began re-examining and casting doubt on this established story. In so doing they presented a alternative account of the 'Fingo' within the Cape Colony.32 What this revised account suggests is that the position of those classified as 'Fingo' was significantly different to that of any other pre-colonial community residing beyond the Eastern Cape frontier. The reconstructed story in the 1990s Tsitsikamma and Clarkson land claims utilized elements of the more common 'Fingo' narrative to justify and legitimate historical rights in land. The power exercised through such discursive constructions contributed towards deligitimising the Moravian mission community's contestation of historical rights to the Clarkson land. Omitted in the claim for the return of 'Fingo/Mfengu ancestral land' was the history of selective 'Fingo' headmen, appointed by colonial officials, who received Tsitsikamma land grants from British colonial authorities for services rendered during the 1835 Frontier War. This omission produced a notion of 'ancestral' land in the case of the Tsitsikamma 'Fingo/Mfengu' as predating colonialism, yet their settlement in the Tsitsikamma by colonial officials only occurred in 1837.33

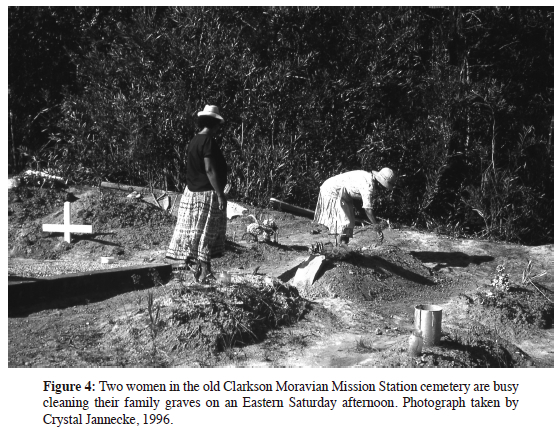

The Moravian mission at Clarkson began in 1839 and was established in response to requests by British colonial authorities for Moravian missionaries to work among the 'coloured' people, which in the Cape colonial context of the 1830s included those classified as 'Fingo/Mfengu', freed slaves, as well as designated groups of people now referred to as Khoikhoi or Khoisan. The South African Apartheid State officially classified the Clarkson mission community as 'coloured' during the 1950s. An emerging commonly taken-for-granted perception of this official racial category of people was that they had no significant long-standing history. By implication then, the Clarksoners were commonly regarded as having no historical connection to the mission land used and occupied, despite having rights in land that dated back to the establishment of the mission station in 1839. By the 1990s the Clarkson Moravian mission community had appropriated both a racialised 'coloured' and a Moravian mission identity. The community firmly followed a church calendar that annually commemorated the Unitas Fratum, and Herrnhuters with Zinzendorf as its leader. It also celebrated the establishment of the Moravian mission in South Africa by George Schmidt as well as the beginning of the Clarkson mission in the Tsitsikamma. The most noteworthy memorialized event of the Church calendar remains the Festival of 'Brotherly Love' (August 13), which marked the Herrnhuters' acceptance of a village constitution and 'Brotherly Union Compact'.34 A week later children honoured a children's festival of Christian awakening and conversion.35 A prescribed Moravian liturgy with accompanying rituals annually observes Lent and Easter. These rituals show the appropriation and reordering of elements of the Moravian missionary traditions, customs, rules and practices. Elements of remembered practices that fell outside of these Moravian conventions had been included, like the annual grave-cleaning and funeral rituals bringing to the fore customs, traditions, rules and regulations unique to Clarkson. From these emerged a Moravian mission identity tied to the place and territorial boundaries of Clarkson. The people living there had cultivated deep associations with each other over time and to the land occupied since 1839.

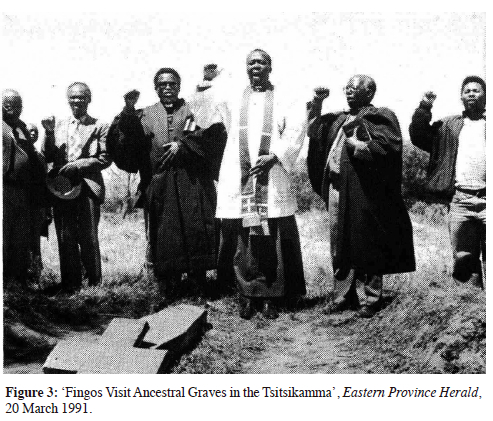

It remains significant that no intersection occurred between the grave-cleaning rituals of the Clarksoner and contemporary 'Fingo/Mfengu' communities. Separate commemorations overlooked shared familial ties between living and deceased relatives.

Negotiating a Contested Land Claim: Constructing the Constitutive Outside

Any claim of entitlement to land cannot disregard the historical land rights (albeit complex and ambiguous), and the nuanced histories of emerging communities. Yet the public demand made by the Tsitsikamma 'Fingo/Mfengu' for the 'return of our land', which included the Clarkson mission land, largely disregarded the historical political relation that the residing Moravian mission community had with land used and occupied. In taking forward the demand for the return of 'ancestral' land, the Legal Resource Centre (LRC) assisted the initial group of aged 'Fingo/ Mfengu' representatives who approached it for assistance. In applying its creative solutions and strategies the LRC facilitated the formation of an association in 1991 called the Tsitsikamma Exile Association (Fingo) or TEA (Fingo). By putting in place an organizational infrastructure, the LRC aided the 'return our land' campaign, assisted with the mobilization of members, and supported the formation of a contemporary ethnic 'Fingo/Mfengu' community around a general set of interests involving the restitution of land.

In claiming entitlement to the Clarkson land, the LRC and the TEA (Fingo) held the Moravian Church accountable as signatory to the 1990 Rustenburg Declaration. The clause underpinning these negotiations on the restoration and transformation of rights in land committed the Church to 'examine its land ownership and work for the return of all land expropriated from relocated communities to its original owners'.36 When reflecting on the Clarkson mission land, rights therein are shown to be contextual, ambiguous and nuanced. While the mission station was formally established in 1839, Moravian missionaries and colonial officials had already begun to define the mission's rights in land by 1838.

In a letter dated 14 November 1838, the colonial official, John Bell, qualified the land granted to the Moravians for mission purposes in the Tsitsikamma. The farm on which the Moravian mission station was established, called Koksbosch, was later renamed Clarkson. The Bell letter stipulated that Moravian missionaries:

... will undertake the formation of a missionary institution at Koksbosch ... amongst the Fingo settlements at Tzitzikama ... with those conditions in general, that . the missionary to be employed at the proposed institution shall be permitted to maintain the discipline of the United Brethren's Church within the same [institution], without hindrance or molestation on the part of this government, or any of its officers or servants ...

A portion of land of about 500 morgen in extent ... shall be set apart for the institution, with a view to its being granted to Superintendent of the Brethren's Mission Society in this Colony, on behalf of that Society, for the express purpose ... for the erection thereon of all necessary buildings . It shall not be in the power of the said Society to sell ... or otherwise dispose of the said land, if the Society [wishes to] relinquish the institution, the lands . shall revert to the Government . the government land adjacent to the institution shall . be reserved for the use of the Fingoes principally and for such other natives of colour as shall be duly authorised to reside in the neighbourhood of, and shall be acknowledged in connection with the institution ... The missionaries shall have the right to admit to the institution such labourers and tradesmen and their families, as the superintendent shall see fit, they being Hottentots or other natives of colour . the missionaries shall be at liberty to extend their labour to other natives of colour besides the Fingoes, or even any other colour of the neighbouring population.37

In 1837, one of the 'Fingo/Mfengu' groups brought into the Tsitsikamma by colonial authorities was settled on the Koksbosch farm. Soon colonial officials allocated a portion of this farm to the Moravian Mission Society for missionary purposes. The Bell letter stipulates that part of the Koksbosch farm be given to the Moravians and used for missionary purposes in the midst of the 'Fingoes' as well as 'other natives of colour'. The letter specifies that only a portion of the Koksbosch farm land, approximately 500 morgen (i.e. about 400 ha) in size and extent, be set aside for Moravian missionary purposes. It was on the portion of land on the Koksbosch farm set aside for missionary purposes that the Clarkson mission station was established. The remainder of the Koksbosch farm land set aside for 'Fingo' settlements - principally amounted to a dual land grant. The Tsitsikamma land grants made by colonial authorities to the 'Fingoes' had a distinct status from that granted to the Moravian Mission Society. Bell distinguished between colonial Crown Land allocated for settlement by the colonial designated 'Fingo', and land allocated to the Moravian Mission Society specifically for missionary purposes. In terms of the Bell letter the Moravian missionaries were not granted similar control over the remaining Koksbosch farm land, nor were they granted similar control over land adjacent to Koksbosch on which the other 'Fingo' communities resided. As far as the portion of land granted for missionary purposes was concerned, the Bell letter authorised Moravian missionaries to determine its use and access. These missionaries sought from the outset to ensure that access to the mission station was not restricted to the 'Fingoes' from the surrounding area. The missions rights in land allowed it to include converts from among the local designated 'Fingo', Khoikhoi/Khoisan or any other colonial designated 'natives of colour', as well as freed slaves at the Clarkson mission station. The colonial document limited the Moravian Mission Society's authority over and rights in land, stipulating that it was not to sell nor dispose of the mission land. The conditions stipulated in the Bell letter thus add to the ambiguities already prevalent in the historical claims made to the Clarkson land.

The Clarkson mission station was officially registered in the name of the Moravian Missionary Society in 1841.38 In some vital respects the stipulations of the Clarkson Deed of Grant differed from those set out in the Bell letter. The Moravian Missionary Society thus held the land in trust with full power to possess the land in perpetuity, while their right to dispose of or alienate the land was with-held.39 The Deed of Grant stipulated that for the time being Clarkson was granted in freehold to the superintendent of the Moravian Missionary Society in the Cape Colony. More specifically the Clarkson land was granted 'with full power and authority to possess [the land] in perpetuity'. However the permission for the Moravians to dispose of the land or alienate the land had been crossed out. Whatever the legal status of this kind of 'freehold in trust', in practice it meant that the Moravian Missionary Society was put in a position to control the actual access to, and use of the Clarkson land. The Clarkson Title Deed of 1841 thus did not differentiate between portions of land on Koksbosch which had been set aside for missionary purposes and that set aside principally for 'Fingo' settlement, as had been specified in the Bell letter. Significantly the Deed of Grant also stipulated that the land was to be held on behalf of and in trust for the 'Fingoes' now residing at the institution of Clarkson comprising of 'a piece of ground . containing about 1038 morgen' (or 889 hectares).40 The whole of the Koksbosch farm land, 889 hectares, was now to be held on behalf of, and in trust for, the 'Fingoes'. This was quite significant for the distribution of rights in the land grant. On the one hand, the size of the Clarkson mission station had now increased considerably to encompass the whole farm. On the other hand, the extended mission land was now deemed to be held in trust for the 'Fingoes'. In terms of the Clarkson Deed of Grant the adjacent 'Fingo' land no longer comprised of the remaining portion of the Koksbosch farm. The Deed of Grant shifted the territorial boundary to now being between the Clarkson Moravian mission station and the adjacent 'Fingo/Mfengu' land, which was comprised of Snyklip, Doriskraal, and Wittekleibosch and Palmiet River.41 Particular 'Fingo/Mfengu' communities held rights in land at these respective places, while the Civil Commissioner of Uitenhage held the land in trust.42

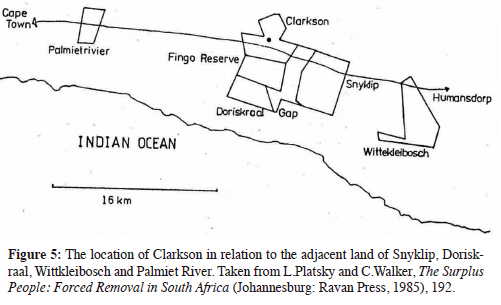

This diagram shows the location of Clarkson in relation to the adjacent land of Snyklip, Doriskraal, Wittekleibosch and Palmiet River. The Clarkson Deed of Grant thus resulted in quite a considerable shift from the 1838 Bell letter and the idea of a dual Clarkson land grant. It in effect amounted to a discrepancy or tension between the legal determinants of the Clarkson Deed of Grant and prior political historical arrangements. Rights in land were further complicated when the Moravian Mission Society handed over its assets at Clarkson to the newly established independent local provincial Moravian Church (Western Cape). The 1959 Deed of Transfer reflected the political context of racial segregation and the State's classification of Clarkson as a mission station for designated 'coloured persons'.43

The ambiguities prevalent in the Clarkson land grant and discrepancies in historical rights in land were not discussed at the initial meeting held in January 1991 between the LRC acting on behalf of the TEA (Fingo), and the Superintendent of the Moravian Church, then the Rev. Martin Wessels. They discussed the extent of support and assistance the Moravian Church could give the TEA (Fingo) and its members. In this meeting the LRC noted that the land held by the Church had been granted in trust to the Tsitsikamma 'Fingo/Mfengu' peoples.44 It requested the Church to demonstrate its support and compliance with the Rustenburg Declaration and release a portion of the mission land for the return of some 50 families to the Tsitsikamma.45 It argued that their presence in the Tsitsikamma was to be a symbolic demonstration of victory over the State, which had dispossessed the 'Fingo/Mfengu' people of their 'ancestral land'.46

The TEA (Fingo) began a successful national media campaign to strengthen its position in local negotiations with the Moravian Church. Selected elements from the Clarkson Deed of Grant highlighted that the mission station land was held in trust by the Moravian Church for the 'Fingo/Mfengu' and their descendents.47In these accounts the corresponding ambiguity of historical rights in the Clarkson land was not made public, nor investigated. As early as 1991 the TEA (Fingo) announced that 'as yet the Fingo Exile Association has not targeted the Church. Its primary aim is to recover land Fingoes occupied until the end of 1977'. Further media coverage cited the Moravians as running 'a mission at Clarkson on 2700 ha . on behalf of and in trust for the Fingoes'.48 The report continued by stating that 'the dilemma the Church faces is causing concern ... efforts are being made to find the original deed'.49 Soon hereafter an article appeared in a local newspaper stating that 'for their part the Mfengu might accept a compromise involving the return of 2700 ha of land, taken over by the Moravian Church in the late 1950s in obscure circumstances'.50 Such descriptions overlooked the independence movement within the South African Moravian Mission Society from the mid-1800s, which culminated in the establishment of an independent indigenous Moravian Church. The Moravian Church overlooked its rich history of being an emerging independent indigenous church during the colonial and apartheid era. In response, the Church affirmed its opposition to apartheid and pledged its 'financial and moral' support for the return of the Tsitsikamma 'Fingo/Mfengu'.51

Even though the Clarksoners share a historical connection with the Tstisikamma 'Fingo/Mfengu' having common deceased relatives, mutual surnames, and related social histories - they were not incorporated into contemporary descriptions of 'Fingo/Mfengu' identity. In the minutes of the first meeting held with the Moravian Church a general acknowledgement is made about 'people of colour living together':

There was a history of unity of the people living together and . it was apartheid that separated families. Hence colour was not seen as an issue. An instance that highlighted the intermix and unity of the people was the way in which people adopted each others surnames and at times changed them from Xhosa to Afrikaans and the other way around e.g. Grootboom to Mtimkulu and Ndluvu to Oliphant.52

The TEA (Fingo) tended to omit this part of the past connection between Tsitsikamma communities in its contemporary descriptions of 'Fingo/Mfengu' history. The silence regarding the people who actually lived on the contested Clarkson mission land, and who had been doing so since 1839, remains significant. Yet this omission intrinsically connected the Clarkson Moravian mission community to the very process of contemporary Tsitsikamma 'Fingo/Mfengu' ethnic identification. In a later news report titled the 'Fingoes Launch Land Battle' the mission community was rather depicted as 'at Clarkson, at the foot of the Kareedouw mountains ... the prospect of hundreds of Fingoes arriving to squat ... fills many with dismay'.53 This silence, as a strategy of dissimulation, effectively excluded the resident Clarkson Moravian mission community from being a critical participant and decision-maker in the negotiation process. Not having a shared historical past placed the Clarksoners in opposition to the contemporary constituted ethnic Tsitsikamma 'Fingo/Mfengu' community. It also created an allegiance and solidarity among those constituted social subjects (Tsitsikamma 'Fingo/Mfengu') who claimed historical entitlement to the Clarkson land. According to Stuart Hall, the process of identification requires what is left outside that is its 'constitutive outside'. This means that in order to consolidate the articulation of a unified ethnic 'Fingo/Mfengu' community, the Clarkson Moravian mission community as the constructed constitutive outside was necessary against which to constitute a contemporary ethnic 'Fingo/Mfengu' identity in relation to the restoration of land in the Tsitsikamma.

In response, local representatives of the Clarkson Moravian Mission community in the form of their Church Council and Local Council or Opsienersraad compiled a memorandum in June 1991, and presented this as a general reflection of views held by members of the resident mission community. The memorandum stated that Clarkson did not belong to the 'Fingo/Mfengu' due to the development and change that had taken place over centuries. Even when negotiations had progressed considerably, the demand amongst the Clarksoner mission residents was that 'the character of the mission station be maintained'.54 Through this call the Clarksoners exercised their power and discursively connected themselves to each Moravian mission station in South Africa and to Genadendal in particular. It also produced an association with the Herrnhut (Moravian) settlement established in Germany during the 1730s as well as to the Unitas Fratum religious community of the 1400s in Czechoslovakia. These connections extended beyond the territorial boundaries of the Tsitsikamma, connecting dispersed associations over time and place to legitimate a historical relationship with the Clarkson Moravian mission land. The plea to preserve the historical character of the mission station concealed strategies of legitimation exercising its power as a community to justify the protection of its historical rights in the mission land. The 1991 memorandum also questioned the validity and origin of the documents referred to by the LRC and TEA (Fingo), insisting that the Moravian Church held ownership of the mission land.55 Local representatives demanded proof that contemporary 'Fingo/Mfengu' members were in fact 'M'fingoes'. The memorandum also recognised that not all the returning 'Fingo/Mfengu' people were Moravians, and asserted that only those who were members of the Moravian Church be granted the right to stay at the mission station. It further noted that in the past the 'Fingo/Mfengu' in Snyklip, Doriskraal and Wittekleibosch 'had refused to live under the authority of the Church'.56The declaration pointed out that if there was to be unity then leaders must address problems of communication and obedience to the rules of the mission station. Additional concerns were expressed:

Where do we stand as Clarksoners, after all the attempts made to develop our community? We are aware that M'fingoes, especially those under the ANC influence, are not hindered in obtaining their goal. What happens to our houses, built under great difficulty and great expense if they decide to occupy and claim Clarkson with force? The Provincial Board must give guidance. The ANC has strong influence. That is why we fear intimidation.57

The Clarksoners in many ways recognized the relations of power established and sustained by the TEA (Fingo) through their links with the ANC and its growing political influence in the 1990s. Its association with the LRC also provided access to valuable skills and an international audience with available financial resources. Yet this mission community persisted in articulating their concerns and demands on security of rights in land as well as maintaining a communal identity of which the rules, regulations, order, and spatial landscape of the mission station was such an important part. At a community meeting held in June 1991, which included members of the Provincial Board, some residents voiced their concern that while they were not opposed to the inclusion of the 'Fingo/Mfengu' at Clarkson, they were concerned that they had no grazing land for their cattle. Their access to land was thus limited since the Church had leased out all the available agricultural land on the mission station to those officially classified 'white' farmers. This left the Clarkson mission residents with only use of their garden plots as grazing land for livestock. Such concerns also recalled the shared dispossessed commonage land that had been included in the Tsitsikamma 'Fingo/Mfengu' 'ancestral land' claimed back from the State, and which excluded the Clarkson mission community. There were also those who indicated that, while they were not opposed to the inclusion of the 'Fingo/Mfengu' at Clarkson, they were worried about the shrinking employment opportunities in the region.58

It was long after perceptions of entitlement to land at Clarkson had been established in the media that the first formal meeting between the TEA (Fingo) and the Moravian Church took place. This was held on 3 July 1991. Representatives to this meeting included the Moravian Church leaders, representatives from Clarkson mission community, the TEA(Fingo), as well as the Bishop B. Evans of the Anglican Church Diocese of Port Elizabeth and Rev. P. Bowen of the Anglican Church who had been a minister in the Tsitsikamma at the time of the forced removals during 1977. In the unfolding discussion the TEA (Fingo) asserted that:

...one of the main fears we have is that if we do not unite in the divisions that our country is beset with between coloured and African, apartheid practices will be further strengthened. We now have a chance to prove that these divisions could be overcome. We know that Clarkson was in the past declared a coloured group area. As a result we were divided. Sometimes it is in moments of honesty said to us that we are the Bantu ... kaffirs, with whom the so-called 'coloured' people want nothing to do. These fears are real ones ... If these fears continue then apartheid is winning, we have then become successfully divided ... The Church cannot play the role of spectator and watch the divisions growing amongst the communities instead of becoming one of the key ... players in overcoming the legacy of apartheid that we are saddled with.59

While Clarkson is correctly described as having been declared a 'coloured' racial area by the State, the people residing there are further represented as being racially antagonistic to the 'Fingo tribe'. Added to the constitutive outside then, was the racial construction of an excluded 'coloured' other. Any dissatisfaction or concern from the Clarksoners with decisions taken during the negotiations regarding the infringement of land rights, escalating unemployment in the area, and maintaining the spatial layout of the mission station was readily construed as Clarksoner 'coloured' racism.

An important agreement made at this July 1991 meeting committed participants to support the resettlement of some 50 returning 'Fingo/Mfengu' families to Clarkson. However the following fears and demands were set forth by the Moravian Church delegation:

...the need to know the timing, place of reoccupation, how and when and what type of infrastructure would be available and how an orderly return would ... take place... The Church and the Mfengu would have to abide by the rules and ordinances of the Church ... Fears that the ANC would intimidate the community was discarded.60

In this instance the Clarkson mission community were aiming to protect the possible infringement of rights in land used and occupied. The spatial layout and design of the new settlement was also to conform and blend in with the character and identity of the Clarkson mission station. In addition, the incoming 'Fingo/ Mfengu' residents were to abide by the rules, regulations, and authority of the Moravian mission station. By 1993 the first housing development, called Silver-town,61 had been completed in terms of the Less Formal Township Act No. 113 of 1991. The agreed upon 50 'Fingo/Mfengu' families moved into the newly established settlement.62 On completion, the spatial layout of Silvertown certainly reflected the design of the central Clarkson mission village.

In March 1994 the TEA (Fingo) was dissolved in anticipation of a land settlement agreement with the State and its 19 associated farmers, which was finalised in April that year. A registered legal trust replaced it, called the Tsitsikamma Development Trust (Mfengu) or TDT (Mfengu). This legal entity proceeded to take over and continue negotiations with the Moravian Church regarding the unresolved Clarkson land claim. By March 1994, the LRC described the negotiations with the Moravian Church as delicate since it now involved discussions on the transformation of Clarkson into an autonomous local authority open to all that is not only 'Fingo/Mfengu' or Moravian. It noted that as signatory to the Rustenburg Declaration, the Moravian Church leadership is determined to support this process of trans-formation,63 even though they perceived the Clarksoners as viewing the imminent return of the 'Fingo/Mfengu' to Clarkson with caution.64 The Moravian Church leadership supported a housing development initiative and the establishment of an appropriate local authority at Clarkson. However, they remained concerned about their local members and their existing rights in land when redressing apartheid inequities, since they had also been victims of the same repressive system.

Negotiations stalled during 1995 after the Moravian Church leadership refused to enter into a Land Availability Agreement with the TDT (Mfengu) aimed at transforming the rights in land at Clarkson including Silvertown. Such an agreement would have set in place a shift from communal to individual ownership of occupied and vacant residential sites to qualifying male and female applicants. Such an agreement would have ensured that all of the residing 175 families at Clarkson received (full) transfer of individual ownership per household of the residential site occupied. Individual land ownership would also have been transferred to the 50 'Fingo/Mfengu' families residing at the Silvertown settlement in Clarkson.65 The TDT (Mfengu) and LRC speedily mobilized against the Moravian Church through its media campaign describing the stalled negotiations as an 'obstacle to ending Mfengu exile'. The Moravian Church was described as 'dithering' and 'threatening to upset the resettlement programme' aimed at ending 'the Mfengu community's years of banishment'.66 Omitted was the earlier restoration of land by the state to be held in trust by the TDT (Mfengu). Since this land (about 8000 ha in size and extent) had been leased out to the very same farmers associated with the apartheid state, the 'Fingo/Mfengu' community were denied possession of the returned land even though their rights therein had been restored. This meant that the returned land at Wittekleibosch, Snyklip, Doriskraal and the Fingo Reserve, and the Gap now held in Trust by the TDT (Mfengu) was not available for agricultural and residential use. The dilemma was that its members required a place to return to in the Tsitsikamma. Yet the TDT (Mfengu)'s public outcry against the Moravian Church omitted its actual predicament regarding the return of its members to restored land in the Tsitsikamma. Nor was the outcome of an October 1995 'Fingo/Mfengu' community survey publicised, in which 388 families indicated their willingness to settle at Clarkson against the 458 families who wished to settle directly on land already returned by the State.67 The TDT (Mfengu) rather presented Clarkson as the only viable residential option in the Tsitsikamma. The 'dithering' of the Church was here largely due to its concerns that the layout of the proposed housing development would significantly reduce the size of the Clarkson mission community's residential and attached garden plots. A community meeting held in Clarkson during January 1996, at which some 'Fingo/Mfengu' representatives were also present responded in part to the LRC and TDT(Mfengu) media campaign. A Clarksoner exclaimed that 'God gave the people a place'.68 A 'Fingo/Mfengu' representative at the meeting described how thankful she was for the meeting about the Clarkson development, stating 'we want to be together. No apartheid. Sad that division is there. We must become one. I will be glad if development comes right'.69 Another Clarkson resident asserted that 'we are not against the return of the Mfengu. The reality is that they were not removed from Clarkson'.70 A 'Fingo/Mfengu' representative stated that 'I want to go and live on the [returned] land. I am not against people who want to stay here [at Clarkson]'.71 While leading decision makers in the negotiating forum created much racial antagonism, at local level a number of members of both communities were prepared to 'become one' and support the development at Clarkson, subject to the consideration of certain rights in land.

Objections to perceived land infringement is seen in the actions of some Clarkson residents who threatened and chased away a land surveyor during 1995 after he had entered and measured their houses and plots of land without prior consent.72 In response, the Moravian Church Provincial Board asserted that the town planning be addressed so that the land usage and existing lifestyle of the Clarkson mission inhabitants would not be interfered with nor reduced.73 In a memorandum to all mission station dwellers the Moravian Church Provincial Board addressed some of the Clarksoners' concerns by asserting that the proposed housing development is not to interfere with the historical character of the mission station. Nor is it to be located between the two existing streets of Clarkson. Nor is it to result in a reduction in the size of their residential and garden plots. It stated that the housing project rather be established beyond the Silvertown housing area in Clarkson. Furthermore, it declared that all persons' rights in land at Clarkson be strengthened with the possibility of these later transformed from communal ownership to individual ownership.74 In a further memorandum addressed to all 'inwoners' or residents of Clarkson, the Chairperson of the Provincial Board of the Moravian Church, Western Province, Rev. B.C.P. Lottering, attempted to appease some of the concerns of the Clarkson mission community over the possible changes that development might make to the 'historical character' of the mission station.75 The negotiations remained in a delicate balance.

An alternative source of community pressure was exerted on the negotiation process when a mass demonstration and march ('optog') was held in Clarkson on 15 March 1996. A notice of was sent to residents of Clarkson, stating:

We herewith wish to inform you of a march that will take place on Saturday 16 March 1996 at eight o'clock from Bazia Street to Church Street. Your support and participation will be highly appreciated. Come and take part as we strive for a better life for all in Clarkson.76

Clarksoners were invited to participate in a form of community action, directed against the Moravian Church central and local Clarkson leadership. The demonstration included the handing over of a memorandum to the local Moravian Church leadership. Demands included therein were, amongst others, that Clarkson be upgraded and that 'the Mfengu ... mix with the coloureds'.77 Further demands included the establishment of a town as soon as possible, the implementation of the new South African constitution at Clarkson, and that change occurs at Clarkson since it belonged to the new South Africa. In addition the memorandum rejected the rules and regulations of the local Moravian Church leadership, and demanded that the church hand over the land to its owners.78 Included was a statement that 'the garden route zone community says enough is enough, to the Moravian Church leaders who oppressed the people for so long . we the victims of apartheid policies and laws demand property rights here at Clarkson'.79 It concluded with the slogan 'the people of Clarkson shall govern'.80 The demonstration took place through the two streets of Clarkson, adding to the fear, anxiety and frustration of some residents' perceptions of possible loss of land and change of place. At the same time, the participation of a number of Clarksoners in the march revealed previously hidden local support among the mission community for change at the mission station.

The stalled negotiations recommenced, chaired by the Deputy Minister of Land Affairs, Mr. Tobie Meyer. Negotiations culminated in the conclusion of a Communal Property Association Agreement, which included the allocation of land for residential purposes, and a housing development project at Clarkson.81The agreement also involved the establishment of a Clarkson Communal Property Trust Association or CCPT on 16 August 1996.82 The CCPT now held the land for the benefit of all qualifying members and granting rights of occupation by issuing individual participation agreements.83 Since the Moravian Church Synod had not authorised the selling/alienation of any mission land a more secure alternative for holding long-term rights in land had to be found. The suitable option of a 99-year lease agreement made land available at Clarkson for returning 'Fingo/Mfengu' families.84 The Clarkson mission station was now set for significant change aptly captured by a Clarkson resident as 'presently we speak of Clarkson as a mission station and not as a town. If the development continues then the Clarkson mission station falls away and we then only talk of town planning'.85

On completion the housing development project was called Smartie Town, because each house was painted a different colour. Funds for its completion were obtained solely from the South African government's housing subsidy and neither from the TDT (Mfengu), nor from the Moravian Church. The completion of this project heralded the high point of all negotiations and contestation over access to, use and management of the mission land. Clarkson was now set to create the necessary space and place for those who wished to return to the Tsitsikamma. However, the number of returning 'Fingo/Mfengu' people who settled at Clarkson was significantly less than the approximately 575 houses built.86 Even though the CCPT allocated housing to each arriving household, appointed housing consultants had had great difficulty obtaining the necessary numbers of returning 'Fingo/Mfengu' people to take up the completed residential sites.87 A senior member of the CCPT explained that 'they decided to come and settle here and then they left'.88 There were about 300 returning 'Fingo/Mfengu' households that settled in Clarkson. Others chose to remain at their places in Keiskammahoek, East London, Karreedouw and elsewhere. A substantial number of the returning 'Fingo/Mfengu' insisted on being resettled on the restored State land, and so moved from Clarkson to small available pieces of vacant land on Snyklip, Doriskraal, Wittekleibosch, and the Fingo Reserve now called Guava Juice.89 As for the remaining 275 houses in Smartie Town some were occupied then vacated. While other houses remained vacant from the outset. When people vacated their houses they left Clarkson with no subsequent trace. The necessary administrative and legal procedures for the vacant houses to revert back to the CCPT were not followed nor completed, and so most houses remained registered on the name of the initial occupiers. Some of those who remained in Smartie Town and who were not satisfied with the location and/or condition of their allocated houses freely chose where they wished to live from the available 275 vacant houses. Many households moved around Smartie Town shifting their occupation of houses without ensuring that the CCPT kept the necessary administrative record of their change of place.90The CCPT went to surrounding farms 'trying to get neighbouring farm workers to take-up housing in Clarkson'.91 Many homeless and landless families from the old Clarkson mission station also took up accommodation at Smartie Town. The result was a sizeable residential development at Clarkson of which a large number of people had not participated in the resolution of the mission land claim.92 There is a silence within the contemporary Tsitsikamma 'Fingo/Mfengu' account regarding the empty spaces and places that became filled with people who were neither descendants' of the Clarkson mission residents, nor connected in any way to the returning Tsitsikamma 'Fingo/Mfengu' community.

In April 2002 the Moravian Church entered into a Land Availability Agreement with the Koukamma Local Municipality regarding the statutory position of Clarkson as a rural town. In terms of this agreement, the Koukamma Local Municipality now authorized all necessary steps to ensure the transformation of rights in land from communal to individual ownership. This meant the transfer of residential sites at Clarkson to persons who had entered into participation agreements with the CCPT. The garden plots that adjoined the older mission station residential plots were included in the transfer of residential sites to qualifying persons. This made the plots in the older (mission station) part of Clarkson and Silver Town substantially larger than the demarcated plots of Smartie Town. The municipality now owned and was responsible for all public spaces at Clarkson.93 The transfer from communal to individual ownership became extremely complicated when applied to Smartie Town, since many of the initial occupiers who remained official occupiers of houses in terms of the CCPT administration system, had long moved out and remained largely untraceable. A further complication was the individual cases of contested ownership among residents of mission station who had their rights in land withdrawn and their houses confiscated, after banishment from the mission station following their alleged transgression of mission station rules and regulations. The transformation of rights in land at Clarkson from communal to individual ownership is subject to the resolution of many of these complications.

Conclusion

In examining the unfolding negotiations between the Moravian Church and the TEA (Fingo), the Clarkson mission community's possession of and relation to the land occupied and used remained largely concealed. Despite sharing a historical kinship and association, both the Tsitsikamma 'Fingo/Mfengu' and Clarkson mission communities represented themselves in exclusion of the other. For the Clarkson Moravian mission community on the one hand, linkages were made with the first Moravian settlement at Genadendal as far back as the 1730s. This contemporary mission identity also articulated connections with the founding Moravian settlement at Herrnhut in Dresden Germany as well as the ancient Unitas Fratum of the 1400s at Moravia and Bohemia in Czechoslovakia. Relating these dispersed and varied associations over time and place discursively through a process of identification constituted a unity within the Clarkson mission community. This distinguished it from those who did not participate in forms of solidarity mobilized around maintaining the 'Moravian character' of the Clarkson mission station. The Tsitsikamma 'Fingo/Mfengu' community, on the other hand, made primordial linkages with communities that existed before the Mfecane carnage. Such past associations memorialized the Tsitsikamma land grants received from colonial authorities while omitting their participation in the Eastern Cape frontier wars as supporters of the British Colony. The internal communal homogeneity created by such associations and linkages excluded the neighbouring Clarkson mission community even though many 'Fingo/Mfengu' had become part of the Clarkson Moravian mission community by having accepted its doctrine, rituals, rules and regulations. Familial relations were not celebrated, nor publicized. Rather emphasized was an essentialised identity problematic in the holding of land in trust by a racial 'coloured' Moravian Church on behalf of an ethnic 'Fingo' community regrouped and brought together in the 1990s. The ambiguities surrounding the Clarkson historical land rights were not publicly engaged with in this problematic. Instead, the demand for the return of 'Fingo/Mfengu ancestral land' in the Tsitsikamma included the Clarkson land producing a symbolic boundary that excluded the residing Moravian mission community. In forming the contemporary ethnic Tsitsikamma 'Fingo/Mfengu' community entitlement to land is legitimated with the excluded Clarkson mission community constructed as the racialised constitutive 'coloured' outside. However, throughout these land claim negotiations the voice of this discursively excluded mission community resonates through decisions taken in the negotiating forum and in the transformation of Clarkson from mission station into rural town.

In general, the political consequences and discrepancies between the discursive unity of communal identities as against the differentiated nature of the actual collectivities and what it excludes remains important especially when these are connected to historically complex and ambiguous rights in land. Extending interpretations of rights in land to include the nuanced political histories of contemporary communities that have emerged when claiming entitlement to land begins to unmask appropriated colonial and apartheid racial and ethnic constructs, rather than sustain its current primordial use in the formulation of land restitution claims and post-settlement land use initiatives.

1 This research formed part my doctoral dissertation for which I wish to thank André du Toit as academic supervisor from the University of Cape Town. I also wish to thank the Programme on the Study of the Humanities in Africa (PSHA) of the Centre for Humanities Research (CHR) at the University of the Western Cape for the award of its generous 2006 postdoctoral fellowship. I also thank Premesh Lalu, coordinator of the PSHA, and Leslie Witz, director of the CHR, for their reading of drafts and useful comments.

2 The Natives Trust Land Act No. 18, 1936.

3 The International Moravian Mission Society had already during the 1860s decided on systematically handing over its South African Mission Society to an independent local Moravian Church. An additional decision was taken to divide the South African Moravian Mission Society into a Western Cape and Eastern Cape region with the language preference of Xhosa and Dutch/Afrikaans used as criteria for the subdivision. The Western Cape region was the first to establish an independent local Moravian Church in 1960.

4 Republic of South Africa, 'First Report of the Select Committee on Bantu Affairs', House of Assembly, S.C. 9- 75, Schedule B.

5 The lease agreement was dated 8 November 1985 and backdated for occupation and use of the land to 1 June 1976. The Director of the Kareedouw Boerdery at the time was Gert Josephus van Vollenhoven. See The 'Notarial Contract', K111/85, Protokol No. 466A.

6 Interview with Chrissie Sedeku, Clarkson, 6 May 2003.

7 Cape Archive, CA LG 592. Hudson to Civil Commissioner of Uitenhage. 31 August 1837, 18 September 1837, and 27 September 1837.

8 Tsitsikamma Exile Association (Fingo) and Tsitsikamma Development Trust (Mfengu), 'Agreement of Settlement', Supreme Court of South Africa, Case no. 1306/91, Cape Town, 1994. Following this agreement the TEA (Fingo) ceased to exist. Accordingly all matters regarding land development and the outstanding land claims, including the claim lodged against the Moravian Church, were now taken up by the TDT (Mfengu).

9 Some case studies linking land, dispossession, and community formations have been done by Peter Delius, The Land Belongs to Us: the Pedi Polity, the Boers and the British in the Nineteenth Century Transvaal (Johannesburg: Ravan Press, 1983) and The Lion Amongst the Cattle: Reconstruction and Resistance in Northern Transvaal (Randburg: Ravan Press, 1996); Colin Murray, Black Mountain: Land Class and Power in the Eastern Orange Free State 1880s-1980s (Johannesburg: Witwatersrand Press, 1996); and Richard Levin and D. Weiner (eds), 'No More Tears Struggles for Land in Mapumalanga, South Africa (Trenton: Africa World Press, 1997).

10 Stuart Hall, 'The Question of Cultural Identity', 296.

11 Andries du Toit, 'The End of Restitution' in Ben Cousins (ed.), At the Crossroads: Land and Agrarian Reform in South Africa ino the 21st Century (Belville: Programme for Land and Agrarian Studies of the University of the Western Cape and the National Land Committee, 2000), 75-91.

12 Kgopotso Mogope, 'Community and Diversity' in Cousins (ed.), At the Crossroads (2000), 107-110.

13 Deborah James, 'Hills of Thorns: Custom, Knowledge and the Reclaiming of a Lost Land in the New South Africa', Development and Change 31 (2000), 629-649.

14 Hall, 'Who Needs "Identity"?', 5.

15 Hall, 'The Question of Cultural Identity', 297.

16 Henry Bernstein, 'Social Change in the South African Countryside? Land and Production, Poverty and Power', The Journal of Peasant Studies vol. 25(4), July 1998, 1-32.

17 Hall, 'The Question of Cultural Identity', 296-298.

18 Hall, 'Who Needs "Identity"?', 5.

19 Althusser was seminally concerned with the interpellation of individuals as ideological subjects. See L Althusser, 'Ideology and Ideological State Apparatus (Notes Towards and Investigation)' in L. Althusser (ed.), Lenin and Philosophy and Other essays, trans. B. Brewster (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1972).

20 See the following cases as discussed by Collin Murray, 'Land Reform in the Eastern Free State: Policy Dilemmas and Political Conflicts', in Henry Bernstein (ed.), The Agrarian Question in South Africa (London: Frank Cass, 1996), 209-219; F. Lund, 'Lessons From Riemvasmaak for the Land Reform Policies and Programmes in South Africa, vol. 2 (Programme for Land and Agrarian Studies and Farm Africa, 1998), 19-53; S. Robins, 'NGO's, "Bushman" and the Double Vision: The ≠Khomani San Land Claim and the Cultural Politics of Community and Development in the Kalahari', Journal of Southern African Studies vol. 27(4), December 2001, 833-853.

21 Hall, 'The Question of Cultural Identity', 297-298.

22 Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism (London: Verso, 1983).

23 Thompson, Studies, 91-122

24 Thompson, Studies, 130-131. See also John Thompson, Ideology and Modern Culture: Critical Social Theory in the Era of Mass Communication (Cambridge: Polity Press, 1990), 6-10.

25 André du Toit, 'On Ideology', South African Journal of Philosophy, vol. 13(3), 1994, 116.

26 Du Toit, 'On Ideology', 116.

27 Hall, 'Who Needs "Identity"?', 2.

28 Hall, 'Who Needs "Identity"?', 3-4.

29 Hall, 'Who Needs "Identity"?', 3.

30 The Mfecane refers to the supposedly self generated internal conflict, which occurred within the Northern Nguni society's south-west of Delgoa Bay after 1790. According to the received view this internal conflict intensified and culminated in the ascendancy of the Zulu nation under the rule of Shaka during the 1820s. Zulu expansionism resulted in the migration of groups of Nguni peoples into the interior fleeing the military might of Shaka. This well known account is found in J.D.Omer-Cooper, The Zulu Aftermath: A Nineteenth Century Revolution in Bantu Africa (London: Longmans, 1966). A critique of the Mfecane is found in Julian Cobbing, 'The Mfecane as Alibi: Thoughts on Dithakong and Mbolompo', Journal of African History, vol. 29, 1988, 487-519. The Mfecane debate has been taken up by J.D.Omer-Cooper, 'Debate: Has the Mfecane a Future? A Response to the Cobbing Critique', Journal of Southern African Studies, vol. 19(2), June 1993, 273-294; Carolyn Hamilton, '"The Character and Objects of Chaka": A Reconsideration of the Making of Shaka as Mfecane Motor', Journal of African History, vol. 33, 1992, 37-63; J.B. Peires, 'Debate: Paradigm deleted: the Materialist Interpretation of the Mfecane', Journal of Southern African Studies, vol. 19(2), June 1993, 295-313; and Elizabeth A. Eldredge, 'Sources of Conflict in Southern Africa, c. 1800-1830: The Mfecane Reconsidered', Journal of African History, vol. 33, 1992, 1-35.

31 See J. Ayliff and J. Whitehead, History of the Abambo Generally Known as Fingoes (Butterworth, Gazette, 1912), 1-2; R. Godlonton, A Narrative of the Irruption of the Kaffir Hordes into the Eastern Province of the Cape of Good Hope, 1834-1835 (Cape Town: Menrant and Godlonton, 1836), 140-143; Noel Mostert, Frontiers: The Epic of South Africa's Creation and the Tragedy of the Xhosa People (London: Jonathan Cape, 1992), 722; T.R.H. Davenport, South Africa: A Modern History, 4th edition (London, Macmillan, 1991), 58; R.A. Moyer, 'A History of the Mfengu of the Eastern Cape: 1815-1865' (Ph.D. dissertation, School of Oriental and African Studies, London University, 1976); L. Thompson, 'Co-operation and Conflict: The Zulu Kingdom and Natal', in M. Wilson and L Thompson (eds.), The Oxford History of South Africa: South Africa to 1870 (Cape Town: David Philip, 1982); Les Switzer, Power and Resistance in an African Society: The Ciskei Xhosa and the Making of South Africa (Pietermaritzburg: University of Natal Press, 1993), 59.

32 H. Soga, The South-Eastern Bantu (Johannesburg: Witwatersrand University Press, 1930). D. Jabavu, 'The Fingo Slavery Myth', The South African Outlook, June 1935, 123; C. Bundy, The Rise and Fall of the South African Peasantry (London: Heinemann, 1979), 33; J. Peires, The House of Phalo: A History of the Xhosa People in the Days of their Independence (Johannesburg: Ravan Press, 1981), 225; Cobbing, 'The Mfecane as Alibi', 487-519; A. Webster, 'Unmasking the Fingo: The War of 1835 Revisited' in C. Hamilton (ed.), The Mfecane Aftermath: Reconstructive debates in Southern African History (Johannesburg: Witwatersrand University Press, 1995), 256; A. Webster, 'Land Expropriation and the Labour Extraction Under Cape Colonial Rule: The War and the Emancipation of the Fingo' (M.A. dissertation, Rhodes University, 1991), 134-144; T.J. Stapleton, Maqomo, Xhosa Resistance to Colonial Advance 1798-1893 (Johannesburg: Jonathan Ball, 1994), 90-91; Stapleton, 'Oral Evidence in a Pseudo-ethnicity: The Fingo Debate', History in Africa, vol. 22, 1995, 359-366; T.J. Stapleton, 'The Expansion of a Pseudo-Ethnicity in the Eastern Cape: Reconsidering the Fingo "Exodus" of 1865', The International Journal of African Historical Studies, vol. 29(2), 1996, 233; Alan Lester, 'Settlers, the State and Colonial Power: The Colonisation of Queen Adelaide Province, 1834-1837', Jounal of African History, vol. 39, 1998, 221-246; Alan Lester, Imperial Networks: Creating Identities in Nineteenth-Century South Africa and Britain (London: Routledge, 2001); Crystal Jannecke, 'The Fingo/Mfengu, a Case Study in Land and Identity' (B.Soc.Sci Hons, Political Studies Department, University of Cape Town, February 1997), 20-23.

33 Cape Archive LG 592, 'Hudson to the Civil Commissioner of Uitenhage', Grahamstown, 31 August 1837, 18 September 1837, and 27 September 1837.

34 The distinctive features of the Herrnhut Community are discussed in Crystal Jannecke, 'Communal Identity and Historical Claims to Land in South Africa: The Cases of the Clarkson Moravian Mission and the Tsitsikamma Mfengu' (Ph.D., Political Studies Department, University of Cape Town, September 2005), 72-84.

35 In South Africa the festivals have become known and celebrated as 'die dertiende Augustus Fees' with the children celebrating 'kinderfees' and the Christian awakening of Suzanna Kühnel.

36 South African Council of Churches, 'Rustenburg Declaration', 1990.

37 Bell, 'Letter to Reverend D. Hallbeck', Fingo Reserve Deed of Grant, Uitenhage Freehold 10 -16A, surveyed on 19/12/1848 and registered on 15/11/1851. The Title Deed of the Fingo Reserve merely certifies that the land is to be 'reserved' for the use of the 'Fingoes' 'principally' and subject to the arrangements set out in the Bell letter.

38 See the Uitenhage Freehold 9: 7 (15 December 1841).

39 Clarkson Deed of Grant, Uitenhage Freehold 9: 7 (15 December 1841).

40 Clarkson Deed of Grant, Uitenhage Freehold 9: 7.

41 Snyklip, Uitenhage Freehold 11: 3 (30 October 1858); Doriskraal, Uitenhage Freehold 11: 1 (30 October 1858); Wittekleibosch, Uitenhage Freehold 11: 4 (30 October 1858).

42 Snyklip Uitenhage Freehold 11:3 (30 October 1858). The Snyklip farm was held in trust by the Civil Commissioner for the ""tribe of Umblatze"; Doriskraal, Uitenhage Freehold 11:1 (30 October 1858). The Doriskraal farm was held in thrust by the Civil Commissioner of Uitenhage for the 'tribe of Uzweebe'; Wittekleibosch, Uitenhage Freehold 11:4 (30 October 1858). The Civil Commissioner of Uitenhage held the Wittekleibosch farm in trust for the 'tribe of Matomela'.

43 Clarkson Title Deed, T3168/1959.

44 Legal Resource Centre, 'Report of Meeting to Rev. Wessels of the Moravian Church', 16 January 1991.

45 Legal Resource Centre, 'Report of Meeting to Rev. Wessels of the Moravian Church', 16 January 1991.

46 These reasons were provided in later meeting held in July. Legal Resource Centre, 'Minutes of the Meeting held between the Moravian Church and the Tsitsikamma Exile Association', held on 3 July 1991, 10.

47 The ambiguities in the Clarkson Deed of Grant are discussed in Jannecke, 'Communal Identity and Historical Claims to Land', 150-155.

48 'Church backs Tribe's Quest to go Back Home', Sunday Times, 31 March 1991.

49 'Church backs Tribe's Quest to go Back Home', Sunday Times, 31 March 1991.

50 'Mfengu People Fight to Regain Tribal Land They Lost at Gunpoint', Cape Times, 22 April 1991.

51 'Church Backs Tribes Quest to go back Home', Sunday Times, 31 March 1991.

52 Legal Resource Centre, 'Minutes of the Meeting held between the Moravian Church and the Tsitsikamma Exile Association', held on 3 July 1991, 5.

53 'Fingoes Launch Land Battle', Sunday Times, March 1991.

54 The original Afrikaans text is 'die karakter van die Sendingstasie moet behoue bly' in Letter from Kerkraad en Opsienersraad to Rev. B.C.P. Lottering, 'Ontwikkeling te Clarkson', 30 December 1995.

55 Clarkson Moraviese Broederkerk, 'Mandaat van Kerkraad en Opsienersraadslede', 7 June 1991.

56 The original Afrikaans text is 'het geweier om onder the gesag van the Kerk te staan' in Clarkson Moraviese Broederkerk, 'Mandaat van Kerkraad en Opsienersraadslede', 7 June 1991.

57 The original Afrikaans text is ,waar staan ons as Clarksoners, na al die pogings wat aangewend is om vooruitgang van die gemeenskap te bevorder? Ons is daarvan bewus dat die M'fingoes, veral diegene onder A.N.C. invloed, vir niks stuit nie om hul doel te bereik nie. Wat word van ons huise wat met harde moeite en groot onkoste opgerig is as hulle sou besluit om Clarkson met geweld vir hulself toe te eien? Die bestuur moet in hierdie verband raad gee ... die A.N.C. het sterk invloed daarom is daar 'n vrees vir intimidasie' in Clarkson Moraviese Broederkerk, 'Mandaat van Kerkraad en Opsienersraadslede', 7 June 1991.

58 Clarkson Church Council and Opsienersraad, 'Minutes of Clarkson Community Meeting', held on 15 June 1991.

59 Legal Resource Centre, 'Minutes of the Meeting held between the Moravian Church and the Tsitsikamma Exile Association', held on 3 July 1991, 2.

60 Legal Resource Centre, 'Minutes of the Meeting held between the Moravian Church and the Tsitsikamma Exile Association', held on 3 July 1991, 5.

61 The name Silvertown was given to the settlement by both Clarksoners and incoming Mfengu residents because the corrugated iron used to build the houses shined with silver glitter on most sunny days in Clarkson.

62 'Motivating Memorandum, Application for the Designation of Land for Less Formal Settlement, December 1992; Tsitsikamma Exile Association, 'Return to Our Land', September 1991, 6.

63 'Victory ... but now for the Tensions of Coming Home', Supplement to the Mail and Guardian, 25 March 1994.

64 'Victory ... but now for the Tensions of Coming Home', Supplement to the Mail and Guardian, 25 March 1994.

65 Legal Resource Centre, 'Cape Town Report on the Mfengu Tsitsikamma Project', 3 June 1996, 5.

66 'Church is Obstacle to Ending Mefengu's Exile', Sunday Times, 19 November 1995.

67 Legal Resource Centre, 'Report on the Mfengu Titsikamma Project', 3 June 1996, 4.

68 This has been translated into English from the Afrikaans 'God het vir die mense plek gegee'. Minutes, 'Clarkson: Resettlement of the Mfengu', Clarkson, 28 January 1996, 2.

69 The original Afrikaans text is "dankbaar vir geleentheid en 50/50. ... ons will saam wees. Geen apartheid nie. Ook hartseer dat skeiding daar is. Ons moet een word. Ek sal bly wees as ons met ontwikkeling sal regkom" in Minutes, 'Clarkson: Resettlement of the Mfengu', Clarkson, 28 January 1996, 3.

70 The original Afrikaans text is "ons is nie teen the terugkeer van die Mfengu nie. Die werklikheid is dat hulle nie van Clarkson verwyder is nie" in Minutes, 'Clarkson: Resettlement of the Mfengu', Clarkson, 28 January 1996, 5.

71 The original Afrikaans text is "ek wil op die land gaan bly. Ek is nie teen mense wat hier wil bly nie" in Minutes, 'Clarkson: Resettlement of the Mfengu, Clarkson', 28 Januaiy 1996, 6.

72 Interview, Oom Matheus, Clarkson, 1996.

73 Letter from Van Rooyen to the Moravian Church (Western Cape), 'NEWHCO East Cape/Yourselves: Development of 775 Erven at Clarkson in Terms of Joint Venture Agreement', 8 November 1995.