Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Kronos

On-line version ISSN 2309-9585

Print version ISSN 0259-0190

Kronos vol.32 n.1 Cape Town 2006

ARTICLES

Eventless History at the End of Apartheid: The Making of the 1988 Dias Festival

Leslie Witz

History Department, University of the Western Cape

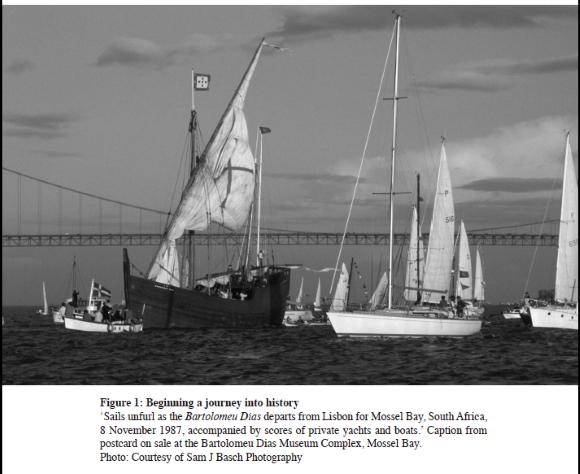

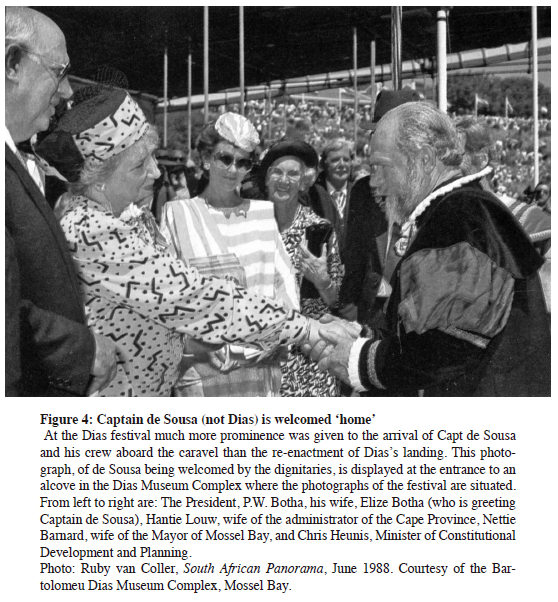

To commemorate the quincentenary of the rounding of the Cape of Good Hope by the Portuguese captain, Bartolomeu Dias, the South African government, headed by an executive state president (which in effect made him commander-in-chief of the Defence Force), PW Botha, sponsored a festival at a series of coastal venues in February1988. The highlight of the festival was the construction of a caravel that sailed from Lisbon in November 1987, stopped en-route at Madeira, and arrived at Mossel Bay, the presumed sight of Dias' landing in 1488, precisely on time for the pageantry of 3 February 1988. PW Botha went aboard the SAS Protea of the South African Navy and welcomed the vessel while it was still at sea. Surrounded by a navy flotilla, the caravel then made its way into Munro Bay in a scene that South African Panorama, an official publication of the National Party's Bureau for Information, described as 'moving and unforgettable', taking 'spectators five centuries into the past'.1

This festival was conceived of and planned in very different set of circumstances than had prevailed when the National Party first came to power some forty years earlier. Then the government had sponsored and organised a set of commemorative events around another figure of European founding and settlement, the first commander of the Dutch East India Company's revictualling station at the Cape Jan van Riebeeck. A major imperative of the apartheid state in its early years was 'establishing a sense of legitimacy among people who racially designated themselves as white, and were in the process of becoming classified as such'.2 One way it sought to do this was to mobilise around a notion of an inclusive white identity and history. The coincidence of the 300th anniversary of Jan van Riebeeck's landing in 1952 provided the National Party government with the opportunity to construct a history and identity of whites as whites. Confident assertions of whiteness and a history containing selected personalities and events of European settlement were key features of creating a racialised South African national citizenry.

Thirty-six years after Jan van Riebeeck landed, and it was time for Portuguese seafarer Dias to step ashore to commemorate his arrival 500 years previously, the National Party was still in power, but it was proclaiming that it was reforming apartheid. Although Dias' arrival was one that could, without doubt, contain all the elements necessary to script a performance of 'white founding' and settlement, the Dias festival could not assert the primacy of South Africa as a white settler nation. The emphasis in 1988 was on apartheid South Africa as being constituted by a 'rich diversity of cultures' that emanated from the contact and interaction 'between Eastern, western and African cultures in this part of the world'.3 In this framework Dias's voyage was not represented as one of national discovery. Instead the land was depicted as already 'inhabited' ('bewoon') prior to his arrival4 and the festival organisers asserted that Dias' significance reached far beyond national significance, claiming that what was being commemorated was the 'wonderful discovery' of the sea route to India, a breakthrough that was ranked 'as equal to modern space travel'.5

However, finding groups that would represent indigeneity and be on hand to welcome Europe to Africa in 1988 with expressions of appreciation was easier said than done. In the pageantry of the 1952 Jan van Riebeeck Tercentenary Festival, when it was absolutely necessary for the historical drama to include people who would be recognised as other than 'white', the organisers were able to call upon individuals or groups of people who had a long history of association with government structures.6 The organizers of Dias 1988 found it immensely difficult to locate participants, contain tensions and contradictions and unearth appropriate history for a festival that asserted its multiculturalism within the bounds of (but attempting to be apart from) the apartheid state. Whereas in 1952 events of history were constructed by festival organizers, negotiated between different European narratives and authorized by historians at universities for public display, in February 1988 denial, suppression and substitution were the basis of the commemorative activities on the beach at Mossel Bay. This article tracks these processes of historical production as the Dias festival was made into eventless history.

A society at war

In the early 1950s, at the time of the Van Riebeeck Festival, there were some, rather ad-hoc, intonations of fashioning subjects of the apartheid state by splitting 'the majority into compartmentalized minorities'.7 This was set in place only in the 1960s as grand apartheid was implemented in a much more formalized manner. Separate nationalized identities were created and sustained for those who were considered subjects of apartheid rule and outside the bounds of the South African nation. By the late 1970s and early 1980s, in the face of ever increasing resistance to the state and its structures, efforts were made to reform and reconstitute apartheid. Repressive mechanisms were set in place accompanied by attempts to bring different groupings of people into the system through carefully selected and appointed 'black' representatives.

The most elaborate of these attempts to re-engineer apartheid took place in 1983 when a revised South African constitution was implemented. Making use of racial categories that were derived from the 1950 Population Registration Act, the constitution created separate franchises for people who were considered to be part of South Africa's 'population groups': 'the White persons, the Coloured persons' and 'the Indians'. In what was called a tricameral parliament, a 'House of Assembly' would make decisions on 'white own affairs', a 'House of Representatives' on 'coloured own affairs' and a House of Delegates on 'Indian own affairs'. Own affairs were defined as: 'Matters which specially or differentially affect a population group in relation to the maintenance of its identity and the upholding and furtherance of its way of life, culture, traditions and customs.' Social welfare, education, arts and culture, health and housing were all specified as 'own affairs'. When there was a matter of uncertainty, the President, who was given sweeping executive powers in the revised constitution, could decide what was a general or own affair. A grouping called a 'President's Council', consisting of representatives from the three Houses and twenty of the President's nominees, was set up to advise the President, particularly on whether an issue was a 'general' or 'own' affair.8

The most telling part of the constitution was that people who constituted the largest proportion of the country's inhabitants, who were the referred to as the 'Black population', were considered as subjects of the President's 'control and administration'. For this 'Black Population' political representation was to be in ethnically designated, rurally based 'homelands' and through local authorities in urban areas. These social and political reforms, the apartheid state envisaged, would be the basis for the emergence of leaders who would cooperate with its structures as well as have community support and thus ensure the maintenance of white minority rule.9

In response to these limited reforms to the structures of apartheid there was sustained, organised and widespread popular rebellion throughout South Africa from the mid-1980s. The government, in turn, declared a State of Emergency, set in place a series of measures to remove community leaders (through assassination or imprisonment) and made attempts to silence the opposition press. As part of the state's counter-revolutionary strategy Joint Management Centres with militarytype structures were established to effect control in local areas. These were complemented by a series of what has been termed 'soft war' social reform measures: abandoning influx control, providing more housing and infrastructure and attempting to co-opt locally based populist leaders.10 This strategy has been effectively described as '"taking out" revolutionaries and "counter-organising" communities so that they become bulwarks against popular pressure'.11 Although this approach had managed to effect control in the townships, and brought to a halt many local rebellions, support for popular organisations continued to remain in place and the state conducted its affairs primarily as a military operation. It would not be inappropriate to describe South Africa, at the beginning of 1988, as a society at war.12

At the same time the South African government was also involved in a series of wars beyond its boundaries. For almost thirteen years, the South African Defence Force (SADF) had been at war with the Angolan government and with the anti-colonial liberation forces in Namibia. Both wars had intensified in the late 1980s. At the end of 1987 the SADF laid siege to Cuito Cuanavale, a town that was being used as an airforce and radar base by Angolan government forces in its campaign against the South African supported National Union for the Total Independence of Angola (UNITA). It seems that the objective behind the siege of Cuito Cuanavale was for the South Africans to give UNITA a much more secure position in southern Angola.13 In Namibia there were 'countless small-scale clashes' taking place between the People's Liberation Army of Namibia and South African armed forces and their surrogates.14

In all these arenas of war visual images of society were key to the battles being fought. Television had become a major vehicle used by the apartheid state in the late 1980s for what Swilling and Phillips refer to as the 'legitimation of state structures'. On South African Television (SATV) resistance was presented as inherently criminal and out-of-control, in contrast to the police and army who were imaged as defenders of community interests.15 In turn, several social documentary photographers adopted a position in what they termed the 'war' against apartheid, claiming to represent the inhumanity, injustice and inequality in, and popular resistance to, the system.16 In Namibia both the liberation movements and the South African army used the camera as a 'weapon' in what Erichsen calls the '"propaganda war" that was being fought alongside the actual war'.17

Posel's analysis of the visual imagery produced on SATV has suggested that its racialised content of 'black mob violence' contradicted the official state discourse of reform. The latter, she argues, attempted to depict the political conflict in the 1980s in a terminology that was non-racial and that posited opposition to radicalism and communism as its primary concerns. In order to win legitimacy for its reform position the state had 'to override starkly racial perceptions of the country's political conflict'. Yet the state had a great deal of difficulty in recasting the racialised identities it had propagated for over 30 years. As the replacement categories of 'communist' and 'radical' constantly shifted in meaning and ambit, the racial classifications remained firmly in place and the visual depictions of violence remained cast on SATV in 'black' and 'white'.18

Planning the Dias festival

These contradictions in the discourse and visualisation of political reform were no more evident than when, in the midst of war, the South Africa government sponsored the Dias festival. To make Dias appear as both a symbol of international importance and of a multicultural nation, the participation of the apartheid government had to be actively concealed. Assertions that the Dias commemoration was 'a festival for whites' were repeatedly denied.19

In the initial planning stages of the festival, however, the limits of association were defined in racially exclusive terms. When members of the Mossel Bay Town Council, met, in 1978, together with the local Member of Parliament, Helgaard Janse van Rensburg, and the Provincial Councillor for the area, Piet Loubser (both of them members of the ruling National Party), the quincentenary was conceptualized as 'the occasion of the first stepping ashore of a white man on the South African coast'.20 To effect this the Postal Tree committee was established. The postal tree referred to a milkwood tree in Mossel Bay, believed to be over 500 years old, where the Pedro de Ataide on a ship bound for home in 1501, left a message for João da Nova, captain of a ship heading for the east. Declared a national monument in 1962, the tree had taken on a symbolic value, representing much more than a moment of white landing, but also establishing a greater sense of a European ancestry from the messages that the travellers left and received there in the course of their journeys.21

Three years later another initiative began to take shape in Cape Town, with a greater emphasis on proposing a reenactment of Dias' voyage as a symbol of Portugueseness within a domain called world history. The primary instigators were the Portuguese Ambassador, Manuel Almeida Coutinho, and the retired King George V Chair of History and former Assistant Principal of the University of Cape Town, Eric Axelson.22 Through correspondence between them and a series of meetings, ideas began to coalesce around organizing commemorative events that would link South Africa and Portugal and the possibility of reconstructing and sailing a caravel from Portugal to the Cape.23 Axelson called for the commemoration to have a 'predominantly cultural and historical nature'. His opinion was that the South African government should not be involved in planning the commemorations, and only be called in at a later stage to provide financial assistance and ensure the participation of the navy. The ambassador concurred and his advice was that only 'scholars and academics' be involved in the preliminary stages of organi-sation.24 The category of history was constantly being invoked as the antithesis of politics, 'the former being identified with objectivity and neutrality, the latter assuming notions of being tainted with partisan affiliations'.25

The starting point of the first meetings of the Steering Committee of the V Centenary Commemoration of Bartolomeu Dias, convened at the offices of the Portuguese Consul General in Cape Town in early 1983, was of 'us' being constituted as products of world history (rather than as a nationalized and racialized citizenry). Most of the representatives were either academics from universities or religious leaders. There was also an attempt to lay claim to a greater sense of multiculturalism by including a Muslim cleric and representatives from the University of the Western Cape (UWC), a university constituted under apartheid for people who were racially designated as 'coloured'. The rector of UWC, Richard van der Ross, was elected to chair the committee. In keeping with a tone of gravitas and international significance the key events for a proposed quincentenary programme were a church service, a naval event of some sort, a visit to Cape Town by a Portuguese scholar and/or dignitary and a series of lectures. A great deal of the committee's time was spent debating the pros and cons of associating with South African government initiatives which were starting to gather pace at this time. Van der Ross was very wary of such a merger as it was likely to 'disinterest many people'. He was supported by many members of the committee who wanted the celebrations to be 'undertaken as a private initiative on the part of interested individuals and communities'.26

Ironically, turning the quincentenary into a commemoration of a 'great event in world history' placed the genesis of the historic 'us' in the Portuguese nationstate. Yet there seems to have been ambivalence in Portugal in accepting this status. Although by the end of 1982 the Portuguese government had set up a group to coordinate projects among departments involved in the quincentenary, by the beginning of 1984 no committee had been formed.27 Perhaps the reluctance is explained by the use of the Portuguese voyages for the purposes of national propaganda under the Salazar and then Caetano dictatorships, from 1932 until 1974. After the revolution of 1974, the end of Portuguese empire in Guinea, Mozambique and Angola, a counter-coup in Portugal, and the assumption of a semblance of a democratic form of government under the 'watching brief' of the military, there may have been less enthusiasm for such brazen gestures of heroic nationalism in Portugal. Military rule, under the non-executive state president, General Antonio Eanes and the elected prime minister, the socialist Mario Soares, lasted until 1986. When the army ceded control, Soares was elected president and the conservative Cavaco Silva, 'an abrasive young economist' whose 'reform' strategy centered on a massive programme of 're-privatisation of the 52% of the economy nationalized after the 1974 revolution', became prime minister, heading a government that obtained an absolute majority in the general elections.28 Wanting to assert Portugal as a modern European nation that was entering the European Economic Community, in January 1987 Silva's government set up a National Board for the Celebration of the Portuguese Discoveries and proclaimed that the Portuguese explorers should become examples for 'the economic and social progress we have to carry out, in the political and institutional stability we are living, to prepare for the coming century.'29 The President of the National Board, E.H. Serra Brandão claimed it was both 'a pleasure and a duty' for Portugal to commemorate the voyages as a way 'to confront ... present problems, ... face the future,... revive national pride, and to remember the contribution we made to the improved knowledge of Man and the Universe'.30 In a moment of ardent nationalist fervour, Commander Rodrigues da Costa, another member of the National Board maintained that 'from 1480 to 1520, we were the greatest in the world, no doubt about it'. Explicitly the commemorations were seen to compensate for the end of the Portuguese imperial project. 'We have lost our empire; now we must discover ourselves,' said da Costa.31

While there was initially some ambivalence in Portugal around commemorative activities associated with Dias, there was much greater enthusiasm from the apartheid government. Eric Axelson, an Emeritus Professor of History at UCT (a designation he specifically asked the minute taker to note),32 for all his initial hesitancy about government involvement, was writing to the Minister of Foreign Affairs, RF (Pik) Botha, and the Minister of National Education, Gerrit Viljoen, urging them 'about the necessity of planning for the commemorations'.33 These suggestions were well received and by September 1983 the Minister of National Education had decided to appoint the National Steering Committee Dias.34 In effect this reduced the group that had been meeting under the auspices of the Portuguese consulate in Cape Town into a local Cape Town committee (with Axeslon and an ex-naval officer, Captain da Sousa as delegates to the national steering committee), alongside an Albany (Grahamstown), Port Elizabeth, Mossel Bay and later a Lüderitz committee. These local committees were all represented on the national structure, together with delegates from the South African Navy, the national government Departments of Education, Foreign Affairs and Nature Conservation, and the cultural affairs section of the Cape provincial government. This was to all intents and purposes, not only a government-appointed committee, but one where its interests were evidently paramount.

Finding ways to hide the South African government's role in the festival, was a matter of considerable concern in the meetings of the steering committee (which by the beginning of 1985 was turned into the National Festival Committee Dias 1988). JJ de Villiers, who represented the Department of National Education on the committee, would report on the money that the government was allocating for the commemoration and then issue a warning that 'the impression must not be created that it would be a festival organized by the Government. The National Festival Committee Dias 1988 would be subject to overall control by the minister mainly with regard to the financial implications to the Government.'35 The Dias committee wanted this scenario to be depicted in the media as the 'facts'. They were well aware that, as the international boycott of apartheid South Africa was becoming more effective in the 1980s, 'the overt involvement of the SA Government in either the organisational arrangements or fund-raising for the caravel project would prejudice international participation.'36 When Elkan Green, the Cape Town festival director, visited Portugal to make arrangements about the caravel and hold a series of meetings with several organizations, his report was kept secret in order to conceal South Africa's involvement in fund-raising. Indeed Green and the festival committee intended to keep government funding to a minimum and instead show that the project was one that emanated from 'Portuguese sources' (the inverted commas are used in the original document) in South Africa and in Portugal.37 Several fund-raising activities were held to solicit these funds but, although there was some support, it did not begin to cover the costs of the festival, in particular the caravel project. All of the R1.3 million that the government guaranteed for the caravel, and that had been held in reserve because of the 'sensitivity of the project',38 was eventually used.39 Nonetheless the cover up of South African government involvement enabled the National Board for the Celebration of Portuguese Discoveries to assert that the idea of the caravel 'came from the Portuguese Communities in South Africa and the National Commission Dias 1988' and that the caravel was built on instruction from 'representatives of the Portuguese Communities'. 40

What made it even more imperative for the committee to depict the South African government as a relatively minor player in the festival organization was the location of the National Steering Committee Dias under the 'white own affairs' Department of National Education. The problem, as the committee saw it, was not that this was a 'fact', but that it should not be a knowable fact, especially in Portugal. The imminent danger was that 'no participation by the Portuguese Government, whether of an official or unofficial nature, would be possible'.41But active suppression of evidence was impossible, particularly as there was dissatisfaction from within the Cape Town committee about the National Committee being located within a 'white' department. For the Cape Town committee this went against the intention of the festival that they asserted as having 'a universal meaning'. This universality did not go against the meanings being developed by the national committee. Indeed it was expressed in precisely the same modernizing alibis of race ('discovery', 'first contacts', and benefits accruing from 'the introduction of Western Civilization'). The Cape Town committee argued, however, that this could not be achieved if the 'descendants of all communities involved, as a result of the events of 1488', were to be excluded from the commemoration by virtue of it being organized as a 'white affair'. Richard van der Ross, the chair of the Cape Town committee, threatened to resign if this situation continued to prevail. Faced with a crisis that could jeopardise the festival, the executive of the National Committee resorted to its strategy of concealment and prevailed upon Van der Ross 'not to release the matter to the media'.42

Van der Ross's resignation did not take place as the National Committee came up with a solution that appeared to appease him: it replicated, on a much smaller scale, the structures of the tricameral parliament. The chair of the National Committee claimed 'it was never the intention that the celebration should be for Whites only'. The decision was made 'to co-opt one member each of the Coloured, Indian and Black population to the Committee'. These would primarily come through the tricameral structures, from the House of Delegates and the House of Representatives, with the 'Black' representative being nominated by the Minister of Co-operation and Development.43 This would make the National Committee similar in its racial structuring to the Cape Town Committee, where representatives from the University of the Western Cape supplied 'coloured' representation to a committee that was dominated by people who were classified, under apartheid, as white, and EA Bawa was defined as a delegate from 'the Indian community'. For the 'swartgemeenskap' [black community] the chair was directed to do research and come up with a suitable nominee.44Van der Ross was completely satisfied with this sort of arrangement and maintained that the operations of the Cape Town committee showed not the 'slightest hint of apartheid'.45

To sustain the image of the festival being dissociated from apartheid South Africa and its government and instead promote a multicultural re-formed Dias, the committee had to make sure that the obvious signs of racialised segregation be eliminated. Often designated as 'petty-apartheid' this included racially designated recreational, eating, seating, drinking and ablution facilities. While some 30-odd years previously, the newly inaugurated National Party government had sought to assure visitors to the Van Riebeeck Festival that it would provide for segregated facilities, in the case of the Dias Festival the National Committee pledged that there would not be racial restrictions to venues and events. This decision had emerged after venues at the holiday resort of Hartenbos (near Mossel Bay) had been proposed for the Dias festival.46 Hartenbos had been developed in the 1930s for Afrikaans speaking white railway workers who felt alienated from Durban, which they perceived as dominated by English-speakers.47 The Dias Committee tried to gain assurances from the ATKV around open access but no reply was forthcoming. In this space of uncertainty the Programme Committee of the festival decided that it 'couldn't risk Hartenbos as it could place festival as a whole in jeopardy if some population groups were excluded.'48 Yet, in deciding to exclude Hartenbos, the committee presented its decision upon the need to centralize venues for the festival in Mossel Bay. For the same reason the committee also maintained it was excluding D'Almeida township, which the Mossel Bay municipality proudly proclaimed as a model 'bruinwoongebied' [coloured residential area] with tarred roads, schools, recreational facilities, a clinic and a library.49

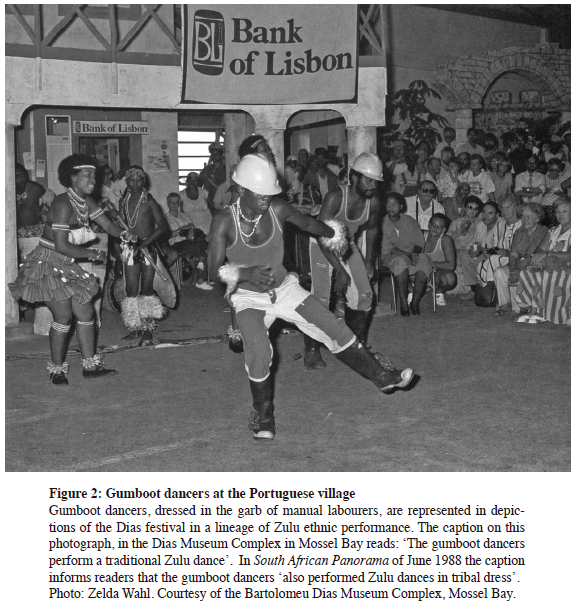

The festival program had also to contain elements that asserted late apartheid South Africa as a multicultural community. Whereas in the Van Riebeeck festival of 1952 there had been special events on specific days for people who were not registered as 'white', in 1988 the idea was that there would be separate folk dances as part of the same event. Negotiations were entered into with the Israeli Shalom Group, Italian and Indian dancers, Scottish bagpipe players, gum boots dancers, and the Malay choir board.50 They would perform as 'traditional folk dancers' at the opening ceremony of the festival, at the Van Riebeeck Stadium, on 29 January, and thereafter at a 'typical' Portuguese village being constructed in a railways goods shed at Mossel Bay Harbour using remains from old houses recently demolished.51 By inserting racialised and ethnicised groups into an international world of cultural difference, dressed up as folk, apartheid South Africa could take to Dias' stage in 1988 as the site of 'many cultures' that were initiated five centuries before.52

Apart from these stagings of folkness was to be the performances by a contingent of black policemen from the police training college in Hammanskraal.

They were penciled into the opening programme at the Van Riebeeck Stadium on 29 January, just prior to the arrival of official dignitaries, and would give a repeat show the next day alongside parachutists, drum majorettes and a dog demonstration.53 These black policemen were part of the increasing number that the South African government was training in the late 1980s. Many of these were known as kitskonstabels (instant constables) who were given quick rudimentary training to police the townships.54 But there were also a substantial number who went to Hammanskraal, a college that was set aside purely for training black policemen, where carrying out drilling exercises was a major component of the curriculum. In 1985-6 2074 'black' police were trained at Hammanskraal, 397 'coloureds' at Bishop Lavis and 288 'indians' at Wentworth. An additional 702 underwent a three week-training course in counter-insurgency at Hammanskraal in the same year. By 1987 there had been a dramatic increase in numbers enrolling and completing their training at these three colleges to 4241 (separate statistics are not available for this period).55 According to Shärf the use of black policemen were seen by the apartheid state as an effective method to counter resistance in the townships as they had more extensive and in-depth knowledge and their acts of repression might not reflect so adversely on the state.56 But it was not in acts of repression that South Africans saw the policeman from Hammanskraal on a regular basis in the late 1980s. They instead made frequent appearances on South African television screens, performing precision mass rhythmic gymnastics. The gymnastic policemen from Hammanskraal were taken out of the context of their daily policing functions and instead appeared only as performers who could be marveled at for their athleticism, precision and rhythmic abilities. The Programme Committee indeed wanted the police for the 'aanskoulikheid' [spectacle] of their 'massavertoonings' [mass displays].57 One request that the Dias Committee made though was that they did not want the new annual, relatively untrained intake at the college to come to the festival.58 Acceding to this request the group who made their way to Mossel Bay had performed together 32 times and had stayed on, after their police training was completed, especially for the festival.59 Gene Louw, the Administrator of the Cape and the chair of National Festival Committee Dias 1988, explicitly anticipated that the police gymnasts would convey an image of the festival (and by implication of late apartheid South Africa) as unreservedly a place and time for all ' rassegroepe' [racial groups].60

Eric Axelson, History and the making of the Dias festival

This image of multiculturalism being promoted by the festival committee enabled Portugal to present Bartolomeu Dias as a South African 'national hero who . transcends and symbolizes the diversity of South African society'. Writing in an introduction to a brochure consisting of selected historical extracts, produced for the National Board for the Celebration of Portuguese Discoveries, Antônio Figueiredo represented Dias and the Portuguese as 'pioneers' of 'contact' rather than colonization. This made Dias not only a 'unifying symbol of the Europeans in South Africa', but also a figure who could enable 'the transient divisions that still characterize South Africa' to be overcome as an appropriate 'inspiring symbol of the ideal of national unification, forged in the very cosmopolitan diversity of south african society'.61

There was, however, a major complication in representing Dias in 1988 as the icon of multicultural convergence within the bounds of apartheid. And that was History. There was so very little of it, both textually and visually, on which to construct the historical drama. For instance, visual images of Dias are scarce and no contemporary 'authentic portrait' exists.62 Furthermore, the History that was on hand did not fit easily into the timing and the content of the narrative of commemoration. As a result the events of history were either significantly modified or suppressed so as to align themselves with the events of the historical commemoration.

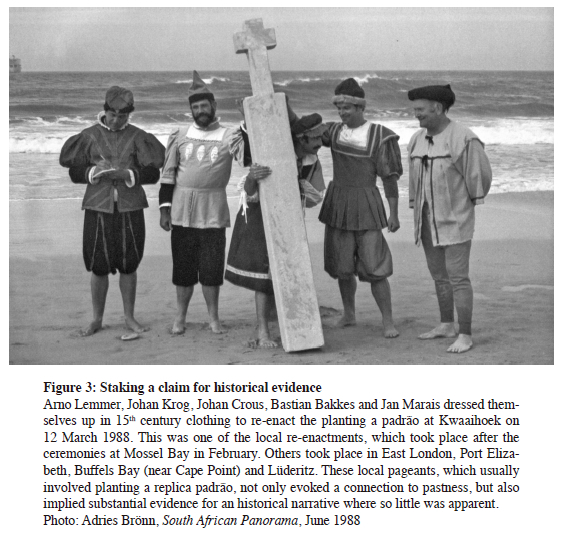

As noted above the primary historian involved in the organization of the Dias festival was Eric Axelson. Axelson was no supporter of the apartheid government and its reform strategy. In his private correspondence he expressed dissatisfaction with the 1983 constitution: 'It grants, as you probably know, a measure of parliamentary representation to 'coloureds' and Indians, but in separate houses, so further constitutionalizing apartheid. There is no provision whatsoever for any black share in the central government; and an executive president is granted extraordinary powers'.63 Yet, for Axelson, 1988 must have represented the coming together of his life's work. Since he had been a doctoral student at the University of the Witwatersrand in the 1935, and his supervisor Leo Fouché had directed him to research 'the Portuguese period in the history of southern Africa',64 this had become his burning passion. In the 1930s, while still a student, he had gone through the records at the Arquivo Nacional da Tôrre do Tombo in Portugal 'searching for documents about early Portuguese contacts with southern Africa'.65 As a research officer at the Ernest Oppenheimer Institute of Portuguese Studies at the University of the Witwatersrand in the 1950s he had turned his attention to 'white settlement and relations between the Portuguese and indigenous populations'.66 In the late 1960s and early 1970s, by which time he had already moved to the University of Cape Town, he was using his research to compose biographies of 'the early Portuguese explorers', Diogo Cão and Bartolomeu Dias.67 Not only did be publish extensive, deeply empirical work on his specific area of expertise, but his major achievement, which he constantly wrote about and gave talks on, was his discovery, at Kwaaihoek in 1938, of the 'the farthest cross' which Bartolomeu Dias had erected in 1488.68 Reconstructed and declared a national monument, the cross was placed in the entrance hall of the William Cullen Library of the University of the Witwatersrand. Raven-Hart referred to it as representing 'the earliest known European relic in Southern Africa.'69 Axelson was commended in Portugal for his research and writing 'on the early Portuguese explorers' by being made Commander of the Order of Infante Dom Henrique.70Furthermore, in 1988 the publication produced by the National Board for the Celebration of the Portuguese Discoveries maintained 'South African historiography' achieved 'its most valuable and original contribution to Portuguese studies, in the books of Eric Axelson'.71

Yet, within South African academic historiography, at the time of the Dias festival, the work of Eric Axelson hardly featured. Already in the early 1960s, at the time of his appointment to the King George V Chair of History at UCT, referees were criticizing his work as empirical and lacking analysis. One referee maintained that Axelson's works were largely '"source-books for historians"', while another maintained that Axelson '"did not see the wood for the trees"'.72In addition, Axelson's approach to the Portuguese in Africa tended to take a very celebratory tone which did not accord with a much more critical stance that was being adopted by academics and students in the wake of independence movements in Portugal's colonies in the 1960s and 1970s. An obituary published in the South African Historical Journal in 1998 maintained that while Axelson had been instrumental in introducing African history to UCT he was an 'old-fashioned, rather austere and essentially modest' historian who was largely dismissed by students and colleagues 'as an antiquarian'.73

For all his impressive archival research Axelson, since the days when he had been a postgraduate student in the 1930s, had been unable to find very much source material on Bartolomeu Dias, particularly in relation to the southern African part of his voyage in 1488. He admitted as much in his dissertation that was published in 1940 under the title South-East Africa 1488-1530:

The journal and charts drawn up by Dias have probably perished, like the vast bulk of Portugal's historical records, either in the reduction of the documents of the national archives by King Manuel, or in the 1775 earthquake, or during the civil wars of the nineteenth century, or simply by the sheer neglect that so persistently characterised the administration of the Portuguese archives. Our main information is derived from a few odd references in a log-book of the voyage of da Gama, and from names appearing on contemporary maps; by correlating these with the calendar of saints, we can be almost certain of the date on which these places were passed.74

As a result of this lack of archival sources, the part of Axelson's book dealing with Dias is littered with references to possibilities and probabilities. About thirty years later, Axelson was unable to find very much more. When called upon to write a biography of Dias, in Faber and Faber's 'Great Travellers' series, he was very reluctant to carry this out as 'insufficient source material had survived the centuries to enable an entire volume to be devoted to Dias alone'. He therefore suggested to the series editor that instead he also include the voyages of Diogo Cão, a proposal that was accepted.75

So, when called upon to compile a commemorative edited volume for the 1988 festival, Axelson had very little material available. He once again drew the attention of readers to the problem that 'no log, no journal, no chart has survived of the Dias voyage'. He accounted for lack of evidence as resulting from the veil of secrecy that the Portuguese had maintained over their voyages in order to avoid foreign competition. When there was source material available, such as from the mid-sixteenth century Portuguese chronicler João de Barros, Axelson asserted that 'several of his statements have proved to be inaccurate'. Only one of the eight chapters in the volume edited by Axelson dealt with Dias exclusively. The book was entitled Dias and his Successors.76

The problem in 1988 was not only that there was not enough material available on which to construct an historical narrative of Dias, but that which there was did not accord with the multicultural theme. One of the sources is the so-called diary of the voyage of Vasco da Gama between 1497 and 1499, apparently written by Álvaro Velho who sailed with Da Gama's fleet aboard the São Rafael, from which extracts were copied in the 16th century, these being first published in 1838.77 Contained within 'Da Gama's diary' is a description of Dias's encounters with the local population when he landed at Mossel Bay, ten years before Da Gama:

... when Bartolomeu Dias was here they fled from him and would not take anything from him that he offered them, but rather, one day, as they were taking in water at a very good watering place that is here at the edge of the sea, they defended the watering place with stones thrown from the top of the hill which is above the watering place, and Bartolomeu Dias shot a cross-bow at them and killed one of them.78

Axelson used this evidence in his book, South-East Africa 1488-1530. He maintained that 'Dias had been strictly instructed in his royal regulations to cause no harm or 'scandal' to the natives of Africa', but 'so incensed was he at the attack that he fired off a crossbow at the assailants and killed one of them'.79 By 1973 Axelson was depicting the event as a cultural misunderstanding with the 'Africans ... astonished at the Portuguese ships and the extraordinary garb of the white men', and the Portuguese in turn not understanding why 'the Hottentots began to throw stones from the low hill that overlooked the watering place.' The result was, in Axelson's words, that 'Dias, in his annoyance, snatched up a cross-bow and shot one of them dead'. Dias and his men then withdrew to their ships 'and continued their voyage'.80

Creating a multicultural pageant on the basis of this evidence would have been enormously difficult. Axelson was asked to forward 'all available historical details known about the events that occurred in Mossel Bay at the time of Dias's landing in 1488, in order to assist the Mossel Bay festival committee with the planning of the historical tableau.'81 His response has not been located and there is a strong possibility that it does not exist. The best that the South African government's Department of Information could do in its publicity for the festival was to represent the encounter as 'an unfortunate incident' that occurred because of a lack of verbal communication.82

The community newspaper in the Oudtshoorn / Mossel Bay region, Saamstaan, provided an historical interpretation of the evidence of events in 1488 to show that this was the beginning of the process of the violent dispossession of people's rights and land that was still continuing into the present.83 Similarly, in a lecture delivered in the series entitled 'Journeys of Discovery' held at the National Arts Festival Winter School in Grahamstown in mid-1988, the archaeologist, Simon Hall, characterised the moment as sowing 'the seeds of distrust ... which were to plague interactions across the prehistoric and historic frontier for years to come.'84Indeed, as early as 1940, Axelson had maintained that the person killed at Mossel Bay by Dias was 'the first victim of white aggression in South Africa'.85 In his book on Dias and Cão, published in 1973, he referred to the incident as creating a 'fatal chain of distrust'.86 Such historical evidence and interpretation could not form the basis of multicultural pageantry on the beaches of Mossel Bay in February 1988 and does not even seem to have been considered as part of the dramatic narrative. Indeed, this series of events at Mossel Bay in 1488 is not referred to in the extracts selected for the special Dias publication that was produced by the National Board of Portuguese Discoveries.

The voyage of the caravel Bartolomeu Dias

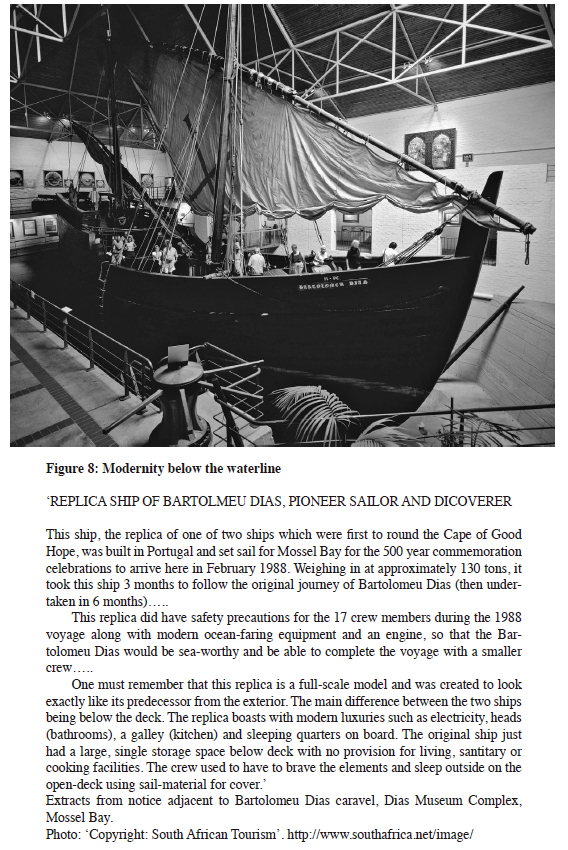

Instead of the moment of encounters at Mossel Bay, it was a reconstructed caravel and its journey from Lisbon to Mossel Bay that became the focus of the historical depictions for the festival. The caravel was intended to represent Dias's achievements and signify both a moment in world history and a meeting of cultures in southern Africa.87 But once again History made the journey of the caravel difficult to represent in 1988. The name of the ship that Dias sailed in is not known and therefore the decision was made to call the 1987/88 version Bartolomeu Dias.88 There were also no contemporary existing plans on which to base the reconstruction, the oldest available being from the early seventeenth century. 'Even the most elementary technical knowledge was not available', reported Captain de Sousa.89 Sketches of caravels on maps and paintings in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries had to be used to approximate the type of ship and the necessary specifications. Axelson, who conducted research for the Dias committee on the requirements for the caravel had to concede that 'the caravel cannot be a perfect replica, because of the ignorance of the original plans'.90 As a result, although the caravel was sturdy and secure, 'her sailing qualities were somewhat disappointing'.91

What compounded matters was that the caravel had to keep to the schedules set by the festival organisers. It could not depend upon the vagaries of the weather. The Caravel Sub-Committee of the National Dias Festival committee therefore took the decision that the caravel hull, below the water line, was to be designed according to modern technology but with appearance of an old-time caravel above the water line. Additional safety features, comforts for the crew and an auxiliary engine were to be installed. In this way the scheduled times of arrival at festival events would be kept to.92 For history to take place in 1988 modernity had to be hidden and kept below the water line.

Yet, even with the engine, and the caravel consuming on average 400 litres of petrol per day, problems began to be encountered about keeping to the festival's schedule. On 7 January 1988 the ship's captain Emilio de Sousa, received a telegram from BA van der Vyver, the deputy chair of the festival committee, expressing concern that the caravel was not going to make it in time for the festival proceedings. 'In view of the scope of the festival at Mossel Bay and attendance by State President P.W. Botha and dignitaries from South Africa and Portugal we cannot afford later arrival of vessel at its destination STOP Management committee . reluctantly resolved to request SA Navy assistance . to make vessel available to accompany and to tow Bartolomeu Dias if necessary STOP'. De Sousa replied that he was 'very much aware of ... arrival at Mossel Bay on the required date due to magnitude of festival, presence of State President, and other dignitaries', but wanted to be given the opportunity to round the Cape of Good Hope unassisted. Over the following week a series of telegrams went back and forth from the Festival Committee to the ship's captain and crew, the former very concerned that a decision had to be made soon in order to be implemented, the latter expressing confidence that they would be able to make it under their own power and 'accordingly not requiring towing'. Ultimately the caravel was allowed to continue on its way (escorted by the SAS Ukomaas until 14 January) using the wind and its engine as its sources of power. On 19 January it took on fresh supplies of fuel at Lüderitz and started the final leg of its journey around the Cape of Good Hope and onward to Mossel Bay.93

The Festival Committee did, however, instruct De Sousa to make a stopover at Simonstown once it had rounded the Cape. This was to make preparations for the caravel's appearance at the festival at Mossel Bay. Repairs and cleaning had to be done, arrangements around the caravel's part in the drama finalised and, most importantly, gasoil containers had to removed from the deck. On stage at Mossel Bay in February the caravel had to appear as an authentic replica that had sailed all the way from Lisbon. Making good time it arrived in Simonstown on 24 January. Visitors were not allowed into the naval base to see and photograph the caravel as 'she was being prepared for the last leg of the journey'.94 The following weekend she was ready to leave and on 30 January it made its way to Mossel Bay, docking for three nights at Vlees Bay en-route. Shortly after midnight on 3 February the ship reached Mossel Bay. At sunrise the navigational lights were switched off, the generator shut down and the sails unbrailed. Just before 10.00am the sails were brailed, the engine was then switched off, the anchor dropped in the bay and a small rowing boat lowered. At 11.00am the boat departed to take Captain de Sousa ashore to greet those who were waiting for him and his crew.95 It was their arrival, and that of Bartolomeu Dias as a ship (rather than as a persona), that were to be the central players in the festival's drama.

A boycott and an accident

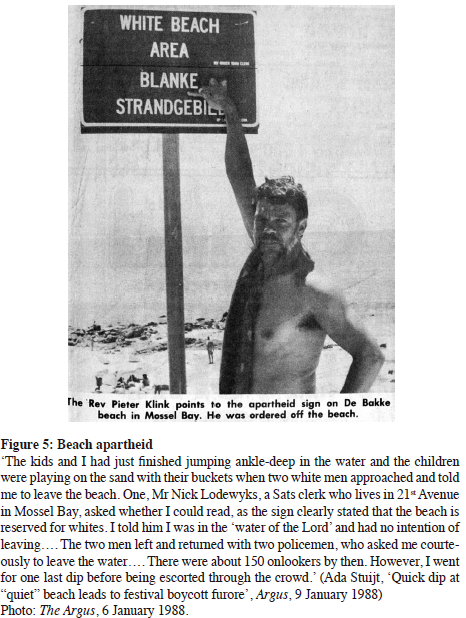

What De Sousa and his crew would have been unaware of was that, almost at the same time as they were dealing with the problem of how to arrive on time, a crisis had emerged on the very stage where they were to land. On the first weekend in January 1988 Rev Pieter Klink, a cleric from Belville South and member of the President's Council that was set up by the new constitution, was ordered off the 'whites only' De Bakke beach at Mossel Bay. Images of Klink, with his towel draped over his torso, pointing out the sign restricting access to the beach, appeared in the press. Klink claimed that Mossel Bay's 'coloured community was affronted by beach apartheid' and suggested that they boycott the Dias festival. 96

Klink's eviction from De Bakke beach was one in a series of high profile conflicts over racially segregated beaches in 1987 and 1988. The one that had received the most media attention was when Rev Allan Hendrickse, the chair of the Minister's Council in the House of Representatives had swum at the 'whites only' King's Beach in Port Elizabeth. Following a 'tongue lashing' from President PW Botha, Hendrickse apologized for his actions.97 In Durban, the Mayor, Henry Klotz, who removed the racial demarcations on the city's northern beaches, was facing a reactionary backlash from white ratepayers who claimed that there was overcrowding as blacks were 'invading' and 'taking over' the area. The ratepayers wanted the beaches 'to be returned to whites for their exclusive use'.98At Umtwalume on the Natal South coast an 'African guard' ordered Prof Brian Blankenberg from the University of Manitoba off the beach 'as it was reserved for whites'.99 In Mossel Bay itself a 'kleurlingman van Kaapstad en sy hinders' [a coloured man from Cape Town and his children] were asked to leave the tidal pool at the Point as this was designated as a 'whites only' beach. The Mossel Bay Advertiser maintained that although there were no signs to indicate this, the racial restrictions on the beach were taken as local knowledge. To ensure that no confusion would again emerge the Mossel Bay Council erected a new notice board, alongside the one prohibiting dogs on the beach, designating the tidal pool and its immediate surrounds as a 'white beach area'.100

Within the realm of politics as constituted through South Africa's re-formed constitution and the tricameral parliament, it was racially segregated facilities that were regarded as synonymous with apartheid. Thus, when The Argus commented on the beach evictions at Mossel Bay in relation to the festival, it was the restricted access to the beaches 'on the basis of skin colour' that was 'spoil[ing]' the commemoration of a 'historic voyage of discovery that led to the founding and development of South Africa'.101 There was no enquiry at all into the underlying basis for the commemorations and why they were deemed to be 'historic'. When Peter Klink, followed by twelve school principals in Mossel Bay, and then Alan Hendrickse, made a call to boycott the Dias festival, its primary aim was to make the Mossel Bay Town Council open access to all its beaches on a permanent basis. Nonetheless this boycott call was framed in the very same racialised categories as the Population Registration Act and directed specifically at 'the coloured communities'. People who were classified 'coloured' were recast as 'indigenous' subjects of oppression and exploitation. In lending support to Klink and the school principals' call for a boycott of the Dias festival, Hendrickse claimed that

We, the coloured community, have nothing to celebrate with the arrival of Dias in any case as it opened the way to the East and to our oppression. Our forefathers, the indigenous Khoi, were dispossessed of their land and rights as a result.102

Richard van der Ross of the Cape Town committee was very reluctant to support the boycott call. Although he announced that he was pulling out of the festival programme that would be held in Mossel Bay, he maintained that his decision had nothing to do with the segregated facilities in the town but arose out of his need to devote his attention to promoting the Dias festival events in Cape Town.103 He was opposed to the racial segregation on beaches, he said, but the decision to restrict access was not derived from the Dias Festival committee. Therefore, he maintained, that actions that serve 'to punish, or to have any adverse effects' should not be directed against them.104

Quite clearly from the very early planning stages of the festival, in the mid-1980s, there had been a problem of finding candidates from racialized communities designated as 'Coloured, 'Indian' and 'Black' to participate in the organizing structures of the Dias festival. KB Tabata, a circuit inspector of Education from Port Elizabeth, nominated by the Minister of Cooperation and Development, did not attend any meetings of the National Committee and resigned. His replacement from the Department of Education and Training, MAE Ndamase similarly regularly tendered his apologies. VL Pillay, a Senior Advisor on History in the Dept of Education and Culture, who was the representative of the House of Delegates, did likewise. Only C Adamson, the Director of the Eoan Group, who had been nominated by the Minister of Education in House of Representatives, appears to have been present more frequently at National Committee meetings. Meanwhile Van der Ross's attempts to secure a 'representative for the black community' on the Cape Town committee proved to be unsuccessful. With his time being occupied by 'disturbances at the University of the Western Cape' he neglected his duties on the Dias committee.105 Later the Cape Town committee reported that it had postponed the decision on the appointment of a representative from the Black community until 'the unrest within this community had abated sufficiently'.106Finally it decided to give up the search for a 'Black representative' because of 'difficulties encountered in identifying Black organizations which would be prepared to nominate representatives'.107

When Ryland Fisher, a reporter from the community newspaper South, visited Mossel Bay at the beginning of February 1988, just before the festival was about to kick off and the caravel was due to arrive, he found that 'the local coloured and African people appeared to be united in their opposition to the fes-tival'.108 Even the festival director, Edwin Tyler was now insisting that they had never had the cooperation of the 'bruingemeenskap" [coloured community].109Fisher described the scene in the town:

... the only blacks who could be seen on the beaches appeared to be municipal cleaning staff or people who had come from outside the area to take part in the festival. A Malay Choir from Cape Town and a choir from Cape Town filled the Dias Hotel in the coloured area. Though the beaches were proclaimed 'open' by the municipality, 'whites only' signs were still up.110

What Fisher also found was that the call to stay away was not merely based upon access to segregated amenities but on a rejection of the system of apartheid and the beach politics of Klink and Hendrickse. Rev Leslie Crotz of the Volkskerk and Rev Pietie Rhodes of the Anglican Church both claimed that, long before Klink and Hendrickse made their 'noise', that there had been absolutely no intention to participate in a festival that celebrated white political and 'economic power' in a country that was 'under a State of Emergency'. Klink was rebuked for his opportunism: '"What's the point of making an issue of being chased off the beach when you are still on the government's payroll."'111

Almost all newspapers reporters who were in attendance, from those who supported the festival to those who were far more cynical, concurred that one had to look 'hard and long to find a black face'. 112 Even one report that maintained that ' groot getalle bruinmense' [a large number of coloured people] attended the festival events had to concede that was ' duidelik dat die fees geboikot word' [clear that then festival was being boycotted].113

With a boycott confounding the attempts at providing a multicultural imagery for Dias, a bus crash, on the day the festival was due to open and the caravel was slowly approaching Mossel Bay, almost entirely shattered any remaining hopes the organisers might still have retained for a 'spectacle of colour'. On the Robinson Pass, 35 kilometers from Mossel Bay, one of the buses, carrying 83 of the police gymnasts from Hammanskraal, lost it brakes. It careered off the road, went over the side of the pass and crashed into a forest of pine trees. Captain JJS Zondi, Constables SP Mbokazi, MP Mogashoa, BA Gumede, MM Sukazi, HM Sebothoma, TB Ngwopa, M Gayisa, MF Seanego, ME Matsepe, MP Myende, DT Phiri and Sergeant MG Pitseng, were all killed in crash. 71 others were injured.114

In its edition of 31 January 1988 the Afrikaans-language Sunday newspaper Rapport, reported on the accident. The story by Nico van Gijsen was headlined, (across five columns) ' Wit span in verongelukte swartes se plek' [White team takes the place of blacks involved in accident]. A smaller, less prominent, supra-heading read ' Dias-fees open met gebaar van meegevoel' [Dias festival opens with gesture of sympathy]. Above the headlines were two large photographs alongside each other. The first, entitled 'Bus Ramp' [Bus Disaster], is a news-type documentary photograph in a horizontal frame (across three columns) showing a tangled wreck of a large vehicle in amongst a forest of trees. In the middle ground are a group of men, most of them dressed in camouflage type uniforms, with their backs to the camera, looking towards the bus. Two of this group are partly facing the camera. Their attention is directed towards the bodies of accident victims that appear, scattered in a clearing, in the foreground of the photograph. The photograph was captioned ' POLISIEMANNE help beseerde swart makkers nadat die bus waarin hulle op pad na die Dias-fees was, oor die rand van die Robinsonpas gestort het. Dertien konstabels is in die ongeluk dood' [POLICEMEN help injured black colleagues after their bus that was taking them to the Dias festival, crashed over the edge of the Robinson pass. Thirteen constables died in the accident]. Alongside the crash photograph was another, over one-and-a-half columns entitled ' Fees gaan voort' [Festival goes ahead]. In contrast to the first photograph this one is spatially orientated in a vertical direction and is a deliberately posed group portrait. Three women and a man, all with broad smiles, face the camera. The women are in the foreground and appear in full-body length. The head and shoulders of the man in the background are visible. He wears a white shirt with lapels and a white cap with a badge attached. Two dark-haired women frame the photograph, standing on either side of an elevated chair, dressed in a knee-length skirt and shorts respectively. Sitting on the chair, at the central focal point, is a fair-haired woman, wearing a dark top and pair of thigh length shorts. The group appears to be inside a boat. The caption read: ' Die eerste van die groep van agt meisies wat om die kroon van Mej.Dias gewydwer het, het gaan kyk hoe lyk die brug van die SAS Protea in Mosselbaai se hawe. Lt. Jaybee de Wet, navigator, was byderhand om hulle rond to wys. Die drie of die foto is (v.l.n.r.) Gaby Martin, 19 van Pretoria, Lara Field, 19, van Kaapstad en Maria Ferreira, 20, van Pretoria' [The first of a group of eight girls that are competing for the crown of Miss Dias, went to look at the bridge of the SAS Protea in the harbour at Mossel Bay. The navigator, Lt Jaybee de Wet, was at hand to show them around. The three in the photograph are (f.l.t.r.) Gaby Martin, 19 of Pretoria, Lara Field, 19, of Cape Town and Maria Ferreira, 20, of Pretoria]. Steve Eggington was credited with the photo.115

These are two very different types of photographs. One documents an event as news, a 'real event', that appears as 'tragic', 'distant' and 'exceptional'.116The other is deliberately staged as publicity heralding and anticipating the Dias festival. In referring to this type of juxtaposition Berger calls our attention to the 'cynicism of the culture which shows them'.117 Such a commentary seems entirely appropriate. A festival that explicitly sought to commemorate 'the first European ever to set foot' on southern African shores as a multicultural event118 taking precedence, in a racially stratified apartheid South Africa over the deaths of the black policemen who had made the long journey from Pretoria to Mossel Bay to participate in the proceedings. The performance of eventless history on the beach and the need to ' gaan voort' [go ahead] with the festival is presented as more important than the 'reality' of events on the pass.119 The performances of the police from Hammanskraal at the Van Riebeeck stadium in Mossel Bay were cancelled and their white colleagues were called in to replace them on the programme of festival events.

The festival goes ahead

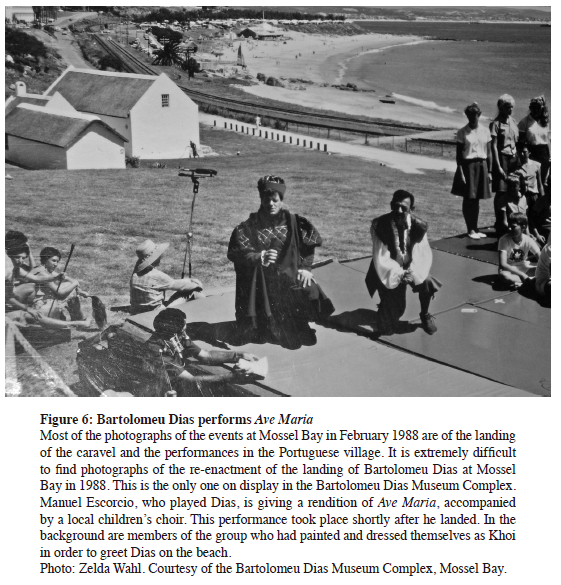

Evidence, an accident (of history?) and a boycott were making the image of a multicultural commemoration of an event in History impossible to sustain. And, in one of the ironies of the late 1980s, it was only through whites rendering themselves as black that the festival, which was constructed around a moment of European arrival (but not of discovery), could proceed. After the dramatic moment when Captain de Sousa and his crew landed, a small tableau of Dias' landing was re-enacted. Written and directed by Marie Hamman, the festival's deputy director, it contained scenes of Dias (Manuel Escorcio) accompanied by Pedro (?) and an unnamed sailor. To meet them were actors representing the indigenous inhabitants, who had gathered around a fire. As they saw Escorcio land they backed away, allowing him to proceed to a nearby spring for a drink of water and then move to a stage where he took hold of the microphone and sang Ava Maria accompanied by a youth choir. What really made spectators gasp in astonishment was that the actors who portrayed the indigenous local population were a 'group of whites' in black masks. In a most astonishing reversal 'whites' had to masquerade as 'blacks' in order to perform late apartheid's festival.

Although masked and dressed as black, these caricatures in the drama on the beach in 1988 bore very little resemblance to the stereotypical blackface minstrelsy that had taken root in the United States, and later at the Cape, in the second half of the nineteenth century.120 Nor was it what Gubar refers to as a racechange, 'an extravagant aesthetic construction that functions self-reflexively to comment on representation in general, racial representation in particular'.121 Instead this was a moment of extreme anxiety, when donning blackness was a desperate attempt by white South Africa to reassert apartheid's largely repudiated modernising claims in almost the same terms as they had been articulated in 1952: 'to preserve . civilised values established here over centuries' and be 'a beacon of civilization and Christian conviction'.122 The performance of blackness, re-presented an alibi in that 'familiar alignment of colonial subjects - Black/White. Self/Other'.123 In late apartheid South Africa whites had to perform as blacks to affirm whiteness as rightness, and blackness as backness.124

The performative mask after all could easily be removed. Soon after Dias landed, and PW Botha had made his speech, three young girls all dressed in longish white dresses stepped up to the rostrum and presented Elize Botha with a cage containing a dove. The South African television commentator, Riaan Cruywagen, identified two of the girls, with long blond hair and who most probably would have been racially classified as 'white' under apartheid, as the Chambers twins from Mossel Bay. The third, who most likely would have been classified as 'black' under apartheid, was completely ignored by the commentator. Elize Botha embraced the Chambers twins and then freed the bird. Cast into the background, the unnamed young 'black' girl was entirely disregarded as the dove soared above the Mossel Bay crowd and Elize Botha hugged and kissed the Chambers twins.125The multicultural legacy which PW Botha and Bartolomeu Dias planned 'to leave to the people of South Africa and to posterity'126 in 1988 was one that found difficulty in accommodating a national identity constructed on ideas of commonality.

Conclusion: A museum of eventless history

On the foundations of eventless history the Bartolomeu Dias Museum complex was built in Mossel Bay and opened in the year following the festival. The largest building on the campus is a Maritime Museum that celebrates and pays homage to the Dias festival of 1988. Artefacts, photographs and ephemera produced for and derived from this festival give this institution its claims to permanence and authenticity as a museum.

An extensive photographic collection, containing many of the images from the festival proceedings (taken by Ruby van Coller and reproduced in the June 1988 edition of South African Panorama) adorns the walls of one of the museum's galleries. A select group of photographs, focusing on the formal proceedings and featuring P. W. Botha, are individually mounted on a blue background, placed in a silver frame and set behind glass. Appearing further along the gallery are approximately 50 block mounted photographs, without any covering or encasement. They are placed on the walls in a scrapbook type montage. Here the commemoration is depicted as a spectacular, participatory festival event. Most of the other photographs are of public performances that took place on the beach when the caravel arrived, in the Van Riebeeck stadium in the town, and at the specially constructed Portuguese village in the harbour

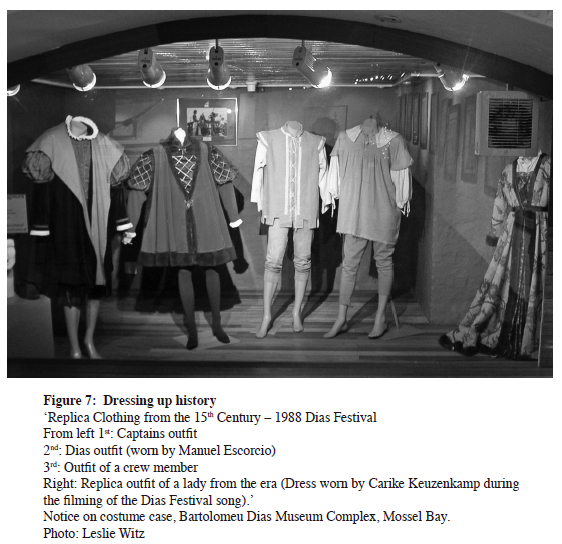

Complementing the photographs are artifacts from the festival. Commemorative coins that were struck for occasion, the costumes worn by the participants in the pageantry and a small-scale model of the caravel made of icing sugar are displayed. The uniform that was worn by Captain Emilio de Sousa is in a special display case opposite the photographic display.

Undoubtedly the highlight for visitors, and the primary reason for the museum's popularity, is the presence of the caravel that sailed from Portugal at the end of 1987. The opportunity to go on board, walk around the deck, stand beneath the masts and then to descend to view the sleeping quarters on what is presented as a full-scale model of a 15th century caravel that looks 'exactly like its predecessor' from the outside entices the visitor. Although the ship is stationary, and a notice does tell visitors that the replica differed from the original in that it had 'luxuries' for the crew, an engine and modern navigational equipment, visitors to the museum imagine themselves at sea in a 15th (and not a 20th) century historical drama.

The boycott does not feature at all in the museum, the reenactment of Dias's landing is virtually unseen in one photograph in a corner of the gallery and there is no mention of the bus accident and the death of the police gymnasts from Hammanskraal. In the Maritime Museum of the Dias Museum complex they have all been hidden from history.

Meanwhile an alcove contains an exhibition with miniature dioramas containing depictions of encounters between the early travellers from Europe and the indigenous population. Inside the alcove is what in museology is called a 'dilemma label' alerting visitors to problems with the display:

Incorrect Information

The Bartolomeu Dias Museum Complex is aware of a number of grammatical and historical errors in the text of this exhibition. The exhibition is displayed as it was donated and presented to the Museum Complex, and we therefore request that queries for information required be addressed to the staff of this Museum.

* This paper is based on research for the NRF funded Project on Public Pasts, based in the History Department at the University of the Western Cape. The financial support of the NRF towards this research is hereby acknowledged. Opinions expressed in this paper and conclusions arrived at are those of the author and are not necessarily to be attributed to the NRF. For assistance with this research I would like to thank Joanne Parsons, Sgt Coetzee, Evangelina Lindt, Lincoln Bernardo and the staff at the Dias Museum Complex, particularly Erna Marx. I also wish to thank Premesh Lalu and Andrew Bank for their extensive comments on earlier drafts of this article.

1 Berna Maree, 'Dias lands again', South African Panorama, 33, 6 (June 1988), 2.

2 Leslie Witz, Apartheid's Festival (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2003), 15.

3 'Message from Gene Louw, Chair of National Festival Committee Dias 1988', in Dias '88 National Festival Programme, Mossel Bay 29 January-6 February, 3.

4 National Festival Committee Dias 1988, Finale Verslag oor die Nasionale Dias-fees 1988, Mossel Bay (Cape Town: 1988), 3.

5 Juliette Saunders, 'Dias festival is aimed at all South Africans', Evening Post, 2 July 1987.

6 See Witz, Apartheid's Festival, chs 2 and 3.

7 Mahmood Mamdani, Citizen and Subject: Contemporary Africa and the Legacy of Late Colonialism (Cape Town: David Philip, 1996), 96.

8 Republic of South Africa Constitution Act No 110 of 1983, http://www.info.gov.za/documents/constitution/83cons.htm, accessed 6 June 2005.

9 Republic of South Africa Constitution Act No 110 of 1983; Mark Swilling and Mark Phillips, 'State power in the 1980s: from 'total strategy' to 'counter-revolutionary warfare', in Jacklyn Cock and Laurie Nathan (eds), War and Society: The Militarisation of South Africa (Cape Town: David Philip, 1989), 144-7.

10 Swilling and Phillips, 'State power', 144-46.

11 Swilling and Phillips, 'State power', 147.

12 Jacklyn Cock, 'Introduction' in Jacklyn Cock and Laurie Nathan (eds), War and Society: The Militarisation of South Africa (Cape Town: David Philip, 1989), 1.

13 Jeremy Grest, 'The South African Defence Force in Angola', in Jacklyn Cock and Laurie Nathan (eds), War and Society: The Militarisation of South Africa (Cape Town: David Philip, 1989), 129-131; Lionel Cliffe, Ray Bush, Jenny Lindsay, Brian Mokopakgosi and Balefi Tsie, The Transition to Independence in Namibia (Boulder: Lynne Rienner, 1994), 58.

14 Casper Erichsen, '"Shoot to kill": Photographic images in the Nambian Independence / Bush War', Kronos 27 (November, 2001), 163.

15 Mark Swilling and Mark Phillips, 'State power', 146. See also Deborah Posel, 'A "battlefield of perceptions": state discourses on political violence, 1985-1988', in Jacklyn Cock and Laurie Nathan (eds), War and Society: The Militarisation of South Africa (Cape Town: David Philip, 1989), 262-274.

16 Patricia Hayes, 'Vision and violence: Photographs of war in southern Angola and northern Namibia', Kronos 27 (November, 2001), 150.

17 Erichsen, 'Shoot', 182.

18 Posel, 'Battlefield of perceptions', 273-4.

19 Saunders, 'Dias festival'.

20 Mossel Bay Advertiser, 25 August 1978.

21 'Die Posboom-omgewing by Mosselbaai', Die Burger, 31 August 1985. A cultural impact assessment, carried out in 1985, reached the conclusion that the tree was not the original tree. See JNF Binneman, 'Kultuuurhistoriese impaktstudie van die Posboomomgewing te Mosselbaai: Versalg en aanbevelings' (Grahamstown and Stellenbosch: Albany Museum, 31 July 1985), 10-11.

22 For a short biography of Axelson see Patrick Harries and Christopher Saunders, 'Eric Axelson and the history of Portugal in Africa', South African Historical Journal 39 (Nov. 1998), 167-175.

23 Resume of meeting with the Portuguese Ambassador, 27 September 1982 (AJ Clement, Dental surgeon from Pt Alfred). Meeting was taped and this is Clement's resume that he passed on to Axelson. The Portuguese ambassador was a little hesitant about the costs that would be incurred on such a project and suggested 'hiring or buying cheaply a replica of the Santa Maria' that was being built for a film commemorating the voyage of Christopher Columbus. Eric Axelson papers UCT Manuscripts and Archives (hereafter EA), Box: Caravel: Minutes, Papers.

24 30 Sep 1981: Axelson to Portuguese ambassador; Resume of meeting with the Portuguese Ambassador, EA, Box: Caravel: Minutes, papers.

25 Witz, Apartheid's Festival, 110.

26 Minutes: Steering Committee of the V Centenary Commemoration of Bartholomeu Dias, 2nd , 4th and 5th meetings (19 May, 7 September and 19 October 2003), EA, Box: Caravel: Minutes; papers.

27 Senhora Dona Maria de Lordes Simões Carvalho to Axelson, 31 Jan 1983; Senhora Dona Maria de Lourdes Simões Carvalho to Axelson, 5 Feb 1984. EA, Box: Caravel: Minutes; papers.

28 David Birmingham, A Concise History of Portugal (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003), 199; Christina Hip-pley, 'Nowhere man who packs potent punch', Observer, 26 July 1987.

29 Edward Cody, 'There is a Feeling We Are Starting a New Cycle in Our History', Washington Post, 13 February 1988, p G8, http://muweb.millersville.edu/~columbus/data/art/CODY-01.ART, accessed 29 May 2005.

30 E.H. Serra Brandão, 'Message', in Antônio Figueiredo (ed), Bartolomeu Dias 1488-1988 (Lisbon: National Board for the Celebration of Portuguese Discoveries, 1988), 4-5.

31 Cody, 'There is a feeling'.

32 Minutes 2nd Meeting, National Steering Committee Dias 1988, 5 December 1983. EA, Box: Dias 1988 Steering Committee: National Committee: Management Committee.

33 Axelson to RF Botha, Min of Foreign Affairs, 9 May 1983; Eric Axelson, 'The Origin of the caravel project, and of the caravel and maritime affairs subcommittee', 31 May 1987 (typed document). EA, Box: Caravel: Minutes; papers.

34 Minutes of National Steering Committee Dias 1988, 1st meeting 15 November 1983. EA, Box: Dias 1988 Steering Committee: National Committee: Management Committee.

35 Minutes First meeting National Committee Dias 1988, 1 February 1985, held in Mossel Bay. EA, Box: Dias 1988 Steering Committee: National Committee: Management Committee.

36 Minutes 3rd Meeting National Committee Dias 1988, 20 August 1985, Cape Town. EA, Box: Dias 1988 Steering Committee: National Committee: Management Committee.

37 Memo from Elkan Green to Chairman, Bartholmeu Dias Cape Town Committee, 31 May 1985. EA, Box: Caravel: Minutes; papers.

38 Minutes Eighth Meeting, National Committee Dias 1988, Friday 5 June 1987, Cape Town. EA, Box: Dias 1988 Steering Committee: National Committee: Management Committee.

39 Dias 1988: Total expenditure: April 1985-July 1988. Annex A to the Minutes 10th meeting National Committee Dias 1988, 3 October 1988. EA, Box: Dias 1988 Steering Committee: National Committee: Management Committee.

40 J Soeiro de Brito, 'The Caravel Bartlomeu Dias', in Antônio Figueiredo (compiler), Bartolomeu Dias 1488-1988 (Lisbon: National Board for the Celebration of Portuguese Discoveries, 1988), 38. Thanks to Rajen Mesthrie for finding this reference.

41 Minutes 2nd Meeting National Festival Committee Dias 1988, 10 May 1985, Cape Town. EA, Box: Dias 1988 Steering Committee: National Committee: Management Committee.

42 Minutes of 7th Meeting Management Committee Dias 1988, 18 Feb 1985. EA, Box: Dias 1988 Steering Committee: National Committee: Management Committee.

43 Minutes 2nd Meeting National Festival Committee Dias 1988, Cape Town, 10 May 1985. EA, Box: Dias 1988 Steering Committee: National Committee: Management Committee.

44 Minutes 4th Meeting National Steering Committee Dias, 31 August 1984. EA, Box: Dias 1988 Steering Committee: National Committee: Management Committee.

45 The Citizen, 20 January 1988.

46 2nd Meeting National Festival Committee Dias 1988, 10 May 1985, Cape Town. EA, Box: Dias 1988 Steering Committee: National Committee: Management Committee.

47 Thanks to Albert Grundlingh for this information. He is presently working on a history of Hartenbos. Email correspondence, 2 January 2005. The Hartenbos Museum, which claims it is 'situated in the heartland of Afrikaans culture' was established in 1939 and sees its main aim as being to provide the public with information about 'The Great Trek' (1835-1848). 'The Aims of the Hartenbos Museum'; 'Historical Background of the Hartenbos Museum'; 'Hartenbos Museum: Historic Afrikaans culture is alive and well', information sheets and pamphlets provided by Hartenbos Museum, 2004.

48 Appendix F: Minutes Program sub-committee, 3 Oct 1985, appended to Minutes 4th Meeting National Festival Committee Dias 1988, 19 November 1985, Cape Town. EA, Box: Dias 1988 Steering Committee: National Committee: Management Committee.

49 Appendix F: Minutes Program sub-committee, 3 Oct 1985, appended to Minutes 4th Meeting National Festival Committee Dias 1988, 19 Nov 1985, Cape Town; Minutes Fifth Meeting National Festival Committee Dias 1988, 11 March 1986, Cape Town. EA, Box: Dias 1988 Steering Committee: National Committee: Management Committee; 'Mosssel Bay 1987', Municipal Brochure (Mossel Bay: 1987).

50 Annex C: Three Monthly Report by Marie Hamman, Assistant Director Dias Festival, 1-1-87 - 31-3-87, appended to Minutes 8th Meeting National Festival Committee Dias 1988, 5 June 1987, Cape Town. EA, Box: Dias 1988 Steering Committee: National Committee: Management Committee.

51 National Festival Programme Dias 1988, as revised on 31 August 1987, appended to Minutes 9th Meeting National Festival Committee Dias 1988, 16 October 1987, Cape Town. EA, Box: Dias 1988 Steering Committee: National Committee: Management Committee. 'Dias recreation an exciting project', Supplement to Cape Times, 30 January 1988.

52 Maree, 'A spectacle'. I am grateful to Ciraj Rassool for discussion on this point.

53 National Festival Programme Dias 1988, as revised on 31 August 1987, appended to Minutes 9th Meeting National Festival Committee Dias 1988, 16 October 1987, Cape Town. EA, Box: Dias 1988 Steering Committee: National Committee: Management Committee.

54 Laurie Nathan, 'Troops in the townships, 1984-1987', in Jacklyn Cock and Laurie Nathan (eds), War and Society: The Militarisation of South Africa (Cape Town: David Philip, 1989), 76.

55 For 'whites' there was a police training college in Pretoria, for 'coloureds' in Bishop Lavis and for 'indians' in Wentworth. Gavin Cawthra, Policing South Africa (Cape Town and London: David Philip and Zed, 1994), 81. Sgt Coetzee of Heritage Services in the South African Police in Pretoria collated these statistics. The statistics for 1985-6 are from Annual Report of the Commissioner of the SAP 1 July 1985 to June 1986. Those for 1987 are from the Annual Report of the Commissioner of the SAP 1 July 1986 to 31 December 1987. The increase in numbers is not the result of the lengthier reporting period as in the 6-month period 1 July 1986 to 31 December 1986 2433 police were trained at Hammanskraal, Wentworth and Bishop Lavis, and the number of 4241only refers to the calendar year of 1987. So from July 1986 to December 1987 6674 'coloured', 'indian' and 'black' police were trained.

56 W Schärf, 'Police abuse of power and victim assistance during apartheid's emergency', paper presented to the Sixth International Symposium on Victimology, Jerusalem, August 1988, cited in Nathan, 'Troops in the townships', 76-7.