Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Kronos

On-line version ISSN 2309-9585

Print version ISSN 0259-0190

Kronos vol.32 n.1 Cape Town 2006

ARTICLES

'The Africa I Know': Film and the Making of 'Bushmen' in Laurens van der Post's Lost World of Kalahari (1956)

Lauren Van Vuuren

Department of Historical Studies, University of Cape Town

In 1954 South African-born writer Laurens van der Post led an expedition into the Kalahari Desert to search for the remnants of what he termed the aboriginal inhabitants of Africa, the Bushmen. His journey became the subject of The Lost World of the Kalahari, one of his most famous books, and the slightly differently titled six-part television series, Lost World of Kalahari (1956), produced for the BBC. Following the release of Lost World and the accompanying book, van der Post became world famous as an 'expert' on the Bushmen. His reputation was based on a substantial literary output on Bushmen, including fiction and non-fiction books.1

Whilst a number of studies over the past twenty years have attempted to unpack Sir Laurens van der Post's influential literary invention of 'Bushmen', little has been written on the function and significance of film in the van der Post oeuvre.2 The BBC documentary film series Lost World of Kalahari, along with van der Post's voluminous literary output on Bushmen and later documentary films that rehashed the themes of Lost World, have made a significant contribution to a pervasive twentieth century conception of Bushmen as mystical pristine primitives who live in harmony with the natural environment, unmolested by a corrupt modern world. This popular and enduring vision of Bushmen still holds power today. This is despite the rigorous critique by many academic anthropologists and historians, activists, aid workers, lawyers and filmmakers, who oppose the tendency of mythical representations of 'Bushmen' that ignore the linguistic and cultural variances, the progress of historical dispossession, and the current marginalisation of Bushmen people throughout southern Africa.

This article provides a close analysis of the film Lost World of Kalahari in order to better understand this highly successful visualisation of van der Post's idealised pristine 'Bushmen'. It will be argued that such a close analysis of the film record is a necessary corollary to other writing on van der Post's Bushmen myth (those that focus on his literary output), in order to further understand the discourses that underwrote his ideas, and specifically and importantly, the power of film to reflect and communicate these ideas. I will show how van der Post's particular and conservative views on Africa were transmitted to an international television audience through his conceptualisation of the Bushmen in Lost World of Kalahari. Furthermore, I explore how van der Post underwrote his powerful 'Bushmen' mythology with a particular mode of self-mythologisation. In assessing this popular visualisation of Bushmen, the film will be considered in the context of changing discourses on Africa in the West in the 1950s, and van der Post's timeous confluence with (and stimulation of) anthropological interest in the Bushmen. In examining the construction of Lost World this article suggests the importance of being able to read the specific language of film as its 'own world of discourse' or how discourse works in film.

This analysis of van der Post's Lost World needs to be seen in the context of an increasing awareness of film as an important archive for historians and anthropologists in helping to understand the (mis)conceptions about difficult subject matter that so often popularly overawes the academic voice. The use of film as a source for historians and as a source of history-telling is highly debated and contentious within the discipline, as visual anthropology remains a contested area of anthropological studies, tending to be categorised away from the written aspects of the discipline.3 This despite the arguments of writers and filmmakers such as David McDougall, who argue for the specific language of film as its own vehicle for exploring and expressing anthropological studies, with its own discourses, modes of representation and building blocks of meaning.4 McDougall's argument is akin to arguments by historians such as Robert A. Rosenstone and Hayden White, who also argue for the specific modality of filmmaking as a way of telling history.5No less significant (though perhaps a little more generally accepted within the discipline of professional history) is the argument for utilising films as archives of the values and attitudes of the people and periods in which they were produced.6I draw on these arguments by assessing the specific language and discourse of the Lost World of Kalahari, and offering some evidence of the value of film analysis for revealing insights into the influential van der Postian myth of the Bushmen.

Clips of a Biography

Soldier, writer, philosopher, civil servant and behind-the-scenes politician Laurens van der Post (1906-1996) rose to fame in post-World War II Britain as an author and speaker. His biography has been exhaustively explored elsewhere.7 Suffice to say that upon his death his list of achievements was considerable: he had won international renown as a best-selling writer, he had been an advisor to British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, was a councillor and confidante to Prince Charles and the godfather of Prince William. He was a recognised authority on the Bushmen as well as on Swiss psychologist C.G Jung, and a patron of the environmental movement worldwide.8 At some point in the 1950s, at a time when his literary career had become well established, van der Post decided to go and 'find' the Bushmen of the Kalahari Desert. In his later years, van der Post framed his entire life and experience as connected to the Bushmen people. This 'connection' was, from the time of Lost World onwards, a mystical connection whereby van der Post might access 'the role of the animal in my own and human imagination'.9 In his deeply critical biography of van der Post, J.D.F. Jones questions van der Post's purportedly lifelong connection to the Bushmen, indicating that van der Post had shown little interest in the Bushmen on earlier expeditions to the Kalahari for the British government. These were undertaken on behalf of the Colonial Development Corporation whose function was to 'initiate, finance and operate projects for agricultural or other development in the Colonial Empire.' Both Wilmsen and Jones have argued that up until the 1955 Lost World expedition van der Post had been a great advocate of the cattle industry in the Kalahari desert, stating in a radio interview in 1954 that

As you know, the Bushmen are the Aborigines of Africa ... And one of the things that appealed to us all was that these remnants of bushmen, who now have no function and no purpose in life, . in a ranching scheme would have a natural function; something that they could understand; something to bring them back to life.10

Seeing the Bushmen as potential labourers for cattle ranches in the Kalahari was a far cry from his later advocacy of a 'Bushmen reserve' where Bushmen could practise hunting-and-gathering unimpeded by contact with the modern world.

Retrospectively, however, the Bushmen would become for van der Post a 'walking pilot scheme of how the European man could find his way back to values he had lost and needed for his own renewal'.11 As I will argue below, van der Post's description of the Bushmen as a 'pilot-scheme' was apt, but more as a pilot-scheme for his own highly subjective philosophies. With his imaginative construction of Bushmen van der Post evoked both earlier, popular literary tropes and an idealised form of primitive humanity that was warmly received in the post-war West. As Alan Barnard wrote in 1989, 'in many Western countries, the general public's knowledge and images of the hunter-gatherer way of life are directly attributable to Sir Laurens van der Post's book and films on his travels in search of the Bushmen of Southern Africa.'12

The tenacity and mendacity of the myth of 'Bushmen' as idealised pristine primitives has been much discussed by scholars over the past thirty years. Beginning in the 1970s with the rise of revisionist anthropology and historiography that sought to contextualise and refine understanding of the position of Bushmen people in southern Africa, the project of 'deconstructing' the popular and mythological image of the Bushmen has taken many forms. This has ranged from revisionist history13 to revisionist anthropology14, from the strident activism by filmmaker John Marshall in northern Namibia to a museum exhibition in Cape Town curated by the artist Pippa Skotnes in 1996. In this process, film has regularly been identified as a prime vehicle for the rehashing of crude myths about the Bushmen, as was so infamously epitomised by the international success of the Jamie Uys film The Gods Must Be Crazy (1980).15 Whilst the mythologizing of Bushmen as 'Noble Savages' or pristine primitives has a pedigree reaching at least back into the nineteenth century, this process has gained a great deal of momentum over the past fifty years, beginning in the 1950s.

Lost World of Kalahari was the first documentary film of the 1950s about Bushmen to attain a wide international audience. Furthermore, as a television documentary it utilised a medium that, particularly in the early years of its development, was not known for encouraging critical thought in its audience.16 In the pithy formulation of the historian David Herlihy where he argues in opposition to much recent history on film: 'doubt is not visual'.17 In the case of van der Post's Bushmen this is particularly apt, considering that in Lost World van der Post postulated and then presented a highly convincing, apparently 'true' image of his idealised Bushmen that left little room for doubt as to the veracity of his filmic construction.

The ratings alone suggest that Lost World of Kalahari was very influential. The BBC declared it a 'tour de force' - One of the most successful film series we have ever undertaken'.18 The entire series was rebroadcast on the BBC in 1957 and subsequently was broadcast many times all over the world. BBC ratings for the film series were said to be second only to those for the Coronation.19 Fully twenty-five years after its original broadcast, a well-known British journalist, Christopher Booker, nominated it as 'the most significant television series ever made'.20 The success of the series was matched only by that of the book The Lost World of the Kalahari. Published in the United States on 29 October 1958 and in London on 10 November, the book built on the publicity around the successful television series. Total British Empire sales climbed to 225,000 over the following four years. Importantly, reviewers in Britain linked the book to the television series.21 Although some influential publications like the Times Literary Supplement contained reviews that were less than complimentary,22 the sales figures speak for themselves: van der Post's Lost World of Kalahari in both book and series form added significantly to his reputation as a writer. At the time that the book of Lost World was enjoying such success, Venture to the Interior had achieved 400 000 sales.23

Importantly, the film also had political influence. Van der Post used the success of Lost World of Kalahari to influence legislation in Botswana. He showed the film to the committee drawing up Botswana's independent Constitution in the late 1950s, a move which influenced the decision to set aside the Central Kalahari Game Reserve in Botswana for the protection of Bushmen.24 In 1962, the film was shown to the Royal African Society in London, followed by a discussion led by van der Post.25 The film was thus a tool for van der Post's politicking, as will be discussed further below.

Lost World of Kalahari (1956): Synopsis and Analysis

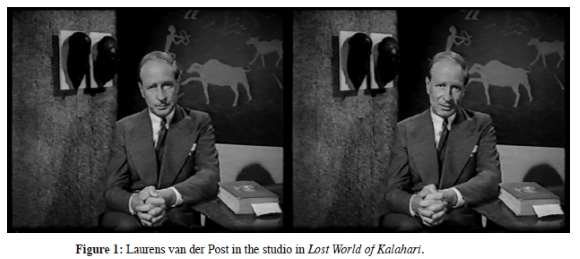

Lost World of the Kalahari consists of six episodes, each running for half an hour, shot on black and white 16mm film. The series is narrated by van der Post, from a studio replete with 'African' trifles, including a rock art wall hanging in the background and masks on the wall. Van der Post, as director of operations from his studio, lectures his audience from behind a desk, or when needs be, from in front of a large map of Africa, upon which he inscribes the route of their expedition in white chalk (Figure 1). By documentary film standards of today this might seem rather quaint, but was very much in keeping with the overtly didactic nature of much of mid-twentieth century documentary filmmaking. The perceived power of the camera to produce a 'record' of reality was commonly accepted in the 1950s, many anthropologists, for example believing that the camera held the key to storing for prosperity indigenous cultures being destroyed by advancing modernity.26 The 'lecture' format of Lost World relates to an important point on van der Post's use of film as evidence to underpin his discourses on Bushmen and Africa, and will be discussed at greater length below.

The first episode, entitled 'The Vanished People', sketches the history of the Bushmen, and the history of van der Post's involvement with them, carefully sculpting the historical context of the expedition. The second episode, entitled 'First Encounter', describes the logistics of preparing for the expedition and the stated aims and objectives of the journey. The expedition members are introduced on camera to the audience and the course of the initial journey is charted in beautifully shot montages of the landscape. Potential hunting, the passing landscape and 'neat little African villages' are documented and discussed. Warning is received of Tstetse fly in the Okavango, but after some adventures the expedition succeeds in travelling through the swamp to make first contact with the 'River' Bushmen.

'The Spirits of the Slippery Hills' is one of the most intriguing episodes. A trip to the Tsodilo Hills in northern Botswana (then Bechuanaland) is undertaken when van der Post hears of a Bushmen family living there from a passing Bushmen who wears trousers but is 'a real Bushmen nonetheless'. A local guide and his son accompany the expedition, explaining to them the spiritual resonance of the Tsodilo Hills. When an expedition member breaks the guide's ban on hunting around the sacred hills, the expedition is plagued by misfortune and technical breakdown of their equipment until van der Post makes 'peace' with the spirits of the hills. The expedition now gets closer to its goal, coming to the outskirts of the Kalahari desert, and suddenly and climactically meeting up with a 'wild, wild' Bushmen, who agrees to take the expedition back to his home in the desert.

Episode four, 'Life in the Thirstland', documents the relationships that develop between van der Post's expedition members and a small Bushmen group living at the Sipwells in the putative heart of the Kalahari. This episode contains many interesting ethnographic details of everyday life amongst the Bushmen, from preparation of food to the manufacturing of bows, arrows, poisons and jewellery. Music and games are shared with the expedition. The music of the band is recorded by the expedition's cameraman. Van der Post translates the lyrics of the songs into English in the voiceover narration.

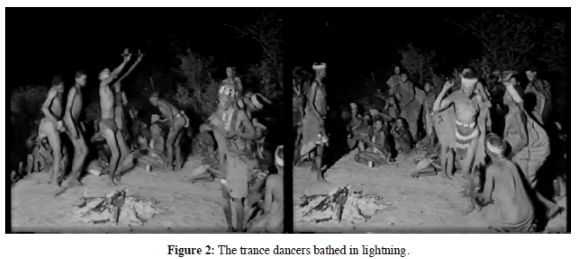

'The Great Eland', episode five, begins the build up to the climax of the series. The expedition members accompany two young Bushmen men on various hunts. The hunt for the great eland is successful. The expedition have, according to van der Post, been intimately accepted into the Bushmen community, as signified by the women coming to ask him for medical advice. It is agreed that a trance dance will be held. All the while, clouds accumulate and the promise of rain generates great excitement. Neighbouring Bushmen arrive to share in the celebration of the successful hunt. The film camera records a variety of dances and the momentum builds as thunder rumbles in the sky and lightening bathes the dancers in a white light that shows up starkly on the black and white film (Figure 2). Dancers enter trance and have to be prevented from jumping into the fire. One man swallows live coals. It begins to rain. The ecstasy dies down and the satisfied dancers return home.

The last episode, 'Rain Song', retreats from the climax of the previous episode. The desert comes alive with flowers and animal life, revelling in the rebirth brought by the rains. Amongst the Sipwell Bushmen, a love affair develops between two of the most eligible youngsters in the community, which van der Post narrates in detail. The time has come for the Bushmen to go on one of their 'great walkabouts', as van der Post describes it. It would be cruel, he declares, for the presence of the expedition to inhibit this 'natural' urge within the Bushmen. As such, he and his expedition take leave of them with great sadness, and van der Post ends the series on a rousing note, declaring that 'the only gift we can give the Bushmen is to give them a place in our hearts and imagination, and in our planning for the future'. He then muses upon the evils of 'civilising' the Bushmen. Most telling is van der Post's concluding entreaty: 'with your help they can go on remaining indefinitely'.

Thus, in Lost World van der Post provides a detailed and highly sculpted vision of an apolitical, edenic Africa free of political trouble and corruption through modernisation. The film's definitive narrative arrangement is supported and corroborated by excellently cinematographed visuals. The 'sculpting process' begins with van der Post defining the Bushmen that he seeks in Lost World as utterly unique because they are a race of 'man-children'. In the book The Lost World of the Kalahari, van der Post elucidated this further.

Perhaps this life of ours, which begins as a quest of the child for the man, and ends as a journey by the man to rediscover the child, needs a clear image of some child-man, like the Bushman, wherein the two are firmly and lovingly joined in order that our confused hearts may stay at the centre of their brief round of departure and return.27

In order that the Bushmen in the television series Lost World should fit this description, the Bushmen filmed had to be living as hunter-gatherers and not show signs of acculturation. Also they had to be utterly isolated from the rest of the world.

Thus the theme of the journey to 'discover' this place that protected Bushmen culture is a key element of the narrative structure of Lost World. It is more than a journey from one place to another. It is also a journey out of (modern) time. In the concluding paragraph of The Lost World of the Kalahari, van der Post writes that upon leaving the Sipwell Bushmen he 'drove over the crest and began the long, harsh journey back to our twentieth-century world beyond the timeless Kalahari blue'.

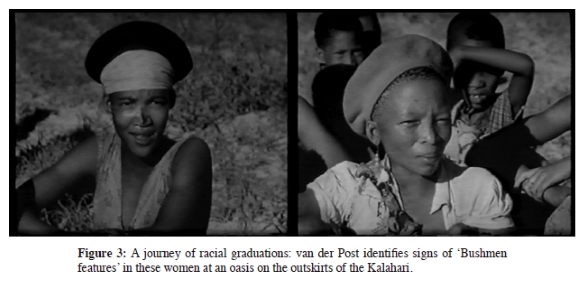

A striking element of this process of journeying out of time is van der Post's insistent emphasis on 'purity' in the Bushmen he seeks. The expedition could also be termed a journey of racial graduations. The people he meets are categorised according to their racial features, in a bid to show how unique and different 'true' Bushmen are compared to all other black and brown people in the region. Thus, people whom the expedition encounters are inspected on camera for physical characteristics that might denote Bushmen ancestry, such as 'high cheek bones' or 'apricot coloured skin'.

For example, at an oasis on the outskirts of the Kalahari van der Post and his companions meet up with a mixed-race group who survive in the arid lands by farming goats. He posits that the reason the group manages to survive at all under these circumstances is because of their 'Bushmen blood'. At this point, the camera focuses in on a group of women from this community. As narrator, van der Post points out to his audience the evidence for this 'Bushmen blood': the slanted eyes and the pointed ears of the women, their 'Mongolian' features (Figure 3). Furthermore, van der Post declares any people they meet coming out of the Kalahari as unlikely to be Bushmen, for a 'true' Bushmen survives in the desert throughout the year, regardless of the weather conditions. Further into the desert, they meet one such group of people who are inspected closely by the expedition members. Van der Post concludes that as they are on their way out of the desert and as they are wearing ragged European clothing, they cannot be 'true Bushmen kind' for they have been 'spoilt by years of contact with civilisation'. The point reiterated by van der Post repeatedly in Lost World is that for anyone to qualify as an authentic Bushman, he or she must be untouched by contact with 'civilisation'.

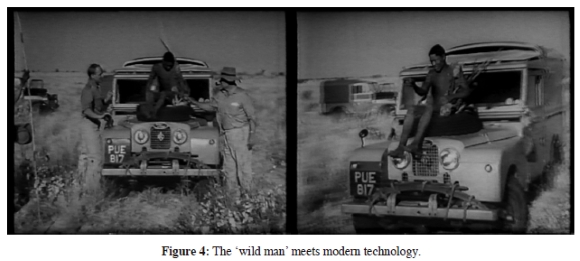

Contact with the 'true' 'veld' Bushmen is made only at the end of episode three, with Dabe the 'tame Bushmen' guide suddenly calling excitedly to van der Post: 'Master, Master! There is a wild man in the grass down there.' The expedition members close in on the 'wild man'. In his excitement, van der Post goes from describing him as a 'wild man' to a 'wild wild man' to a 'wild creature'. The semantics are revealing: van der Post invokes an image with a long history in European intellectual and cultural tradition - that of the 'wild man' who stands in opposition to the 'civilised man'. If, as Hayden White argues, the 'wild man' in the Victorian imagination constituted an 'example of what Western man might have been at one time and what he might become once more if he failed to cultivate the virtues that had allowed him to escape from nature',28 then van der Post's 'Wild Man' is an inversion of this.

In Lost World, it is the 'wild man's' very atavism that makes him important, not a menace but an example to corrupt twentieth century humanity. Van der Post's longing for the atavistic 'wild man' (whilst apparently compassionate) was out of touch with developments in racial discourse in the West after World War II, which generally sought to diminish rather than emphasise racial differences between groups of people.29 In Lost World van der Post drew attention to the 'otherness' of the Bushmen in order to show his audience the wondrous presence of the past in its idealised Bushmen form, in which innocence and simplicity has survived for the benefit of the West's spiritual (dare I say it) development. In the film, this is illustrated pointedly when the 'wild man' perches outside the Landover, on the spare wheel fastened to the bonnet, although not before the Bushman in question has displayed great bemusement and not a little fear at the presence of the menacing vehicles. It does not take long for the plucky 'Wild Man' to overcome his fear though (Figure 4). He immediately trusts van der Post (or so we are assured in the narration) and as such he is able to direct to his home. But the 'wild' Bushman is so utterly isolated, and so different from the expedition member that he does not even recognise the motorcar, that ubiquitous symbol of modernity, and prefers to sit outside of it, away from the white occupants of the vehicle and their 'tame' (sic) Bushmen guide Dabe. 30

It is also worth noting that much of this 'first contact' with the 'true veldt Bushmen' seems highly contrived. It recalls a similar scene in a much earlier film on the Bushmen made in 1925 as part of the Denver African Expedition to Namibia. There the audience is again witness to an extended sequence where purportedly 'wild' Bushmen pop unexpectedly out of the bushes in front of a conveniently running film camera, only to rush off in terror at the presence of the camera and expedition vehicles. As Robert Gordon notes the Bushmen studied by the Denver Africa Expedition were certainly not unaccustomed to a white presence.31 This motif of 'terrified Bushmen' has an even longer genealogy going back to the genre of travel writings in southern Africa, where Bushmen were regularly described as being terrified of western technology and taken to running away in fright at the sight of whites, cattle, guy ropes and wagons.32

In keeping with this idealisation of the 'past in the present', the world of the 'true' Bushmen is described by van der Post as 'lovely and natural'. As the Sipwell Bushmen (as van der Post names them) go about their daily chores, the camera rolls and van der Post again emphasises that amongst these Bushmen, 'no one seems to have heard of time'. Rather, the Bushmen work and sit about 'happily in the sun as they had sat for centuries'. Hunting and dancing are idealised. This would become something of a tradition in later documentary films on the Bush-men.33 In Lost World both are attributed not to culture or even the need to survive, but to the essential nature of the Bushmen. Van der Post actually states in the voiceover narrative that 'true Bushmen are essentially hunters.'

Van der Post as Heroic Explorer

Van der Post combines the mythical image of the Bushmen in Lost World with another fairytale: that of himself as the searcher, frontiersman and explorer who breaks ground both physically and in the realm of the human spirit. It is the combination of these two myths, presented in Lost World that constitutes van der Post's influential Bushmen myth. Arguably, neither would have been as powerful had they been presented in isolation.

In a sense the Bushmen of Lost World were more literary figures than literal ones - literary figures who illustrated van der Post's thesis about the significance of pristine Bushmen culture for the decadent West. The use of the word 'literary' is deliberate, since it is clear from close analysis that it was literary influences that most shaped the journey depicted in the film.34 Lost World is far more about the journey of van der Post than it is about Bushmen in any concrete sense. The presence of the Bushmen as spiritual phantasms drawing van der Post ever onwards provides a powerful and convincing narrative structure for the series, so that van der Post's 'quest' becomes, through six episodes, a metaphysical journey that elevates the meaning of the series to a search for 'lost humanity'.

The quest motif is a familiar literary device in colonial literature set in Africa. Two examples pertinent to Lost World are Joseph Conrad's Heart of Darkness and H.Rider Haggard's King Solomon's Mines. Whilst Conrad's complex and ambivalent examination of colonialism in Heart of Darkness is very different to Rider Haggard's wild adventure stories set in the African continent, elements of both novels find their way into Lost World in the form of recurring motifs throughout the film.35 In the opening episode van der Post describes how he wrote in his diary as a small boy: 'I have decided today that when I am grown-up I'm going into the Kalahari Desert to seek out the Bushmen.' As already noted, the validity of van der Post's claim of having grown up with a profound spiritual connection to Bushmen is questionable. In fact, as Jones notes,36 this reference to a diary entry bears more than a passing resemblance to the story told by Conrad's character Marlowe in Heart of Darkness. Marlowe describes how as a child he had gazed at maps of the world and decided that when he grew up he would go to the places marked on the map, particularly Africa, 'the biggest, the most blank, so to speak - that I had a hankering after'.37 Another connection between Lost World and Heart of Darkness is that of the journey as one into the primordial heart of Africa. In the absence of the distractions and trappings of civilisation, this journey also becomes a journey into the primal impulses of human beings. Where for Conrad the journey is dark and full of despair, for van der Post it enlightens and energises. The 'primordial' in Africa was something altogether more positive in Lost World than it was in Heart of Darkness.

In Lost World van der Post emphasises (and largely exaggerates) the unexplored and untrammelled nature of the regions he is travelling through: the Kalahari is 'one of the great mysteries of Africa', the Chobe and Okavango Swamps are 'unexplored' and the expedition is reliant upon bases set up around the perimeter of the Kalahari for stores and water supplies. The challenge of the wild and unnameable wilderness to an explorer-frontiersman sets up a central tension in the film series. In overcoming these challenges the explorer-frontiersman 'discovers' the Bushmen who exist inside a world that no other humans can comfortably inhabit and that is difficult to access at all.

In 'The Spirits of the Slippery Hills' (episode three) the confrontation between 'spirits' and the expedition members means that van der Post's conciliatory behaviour facilitates a movement through a mystical gateway. Here van der Post declares that the expedition has 'moved into quite another dimension of living' and is freed from the tribulations that had dogged them up until that point. This is reminiscent of the popular nineteenth-century novel King Solomon's Mines, in which an expedition of Europeans passes beyond a mysterious mountain range called Sheba's Breasts in an undisclosed place in Southern Africa, having faced near-death through thirst and starvation. Upon crossing the mountain, they seem to enter a world outside the temporality of colonial Africa, quite another dimension of living: the land of the prosperous, beautiful, noble Kukuanas.38 This mysterious land has remained aloof from the developments in the rest of Africa. It is a land where people live forever and both the environment and the people are beautiful and prosperous. Here the staunch British protagonists come and are met as gods from another planet. They are given access to the very centre of the realm and leave after many adventures, carrying with them wealth untold in the form of the diamonds of King Solomon's Mines. In very much the same way van der Post declares the success of the Lost World expedition to be related to the degree to which the Bushmen group trust in and engage with the expedition members: van der Post boasts towards the end of the film series that the women of the band no longer consult the 'witch doctor' but come to him for medical help.

The allusions to Rider Haggard in Lost World also occur in relation to van der Post's construction of himself as a brave explorer traversing unknown realms, a reputation on which he had been building since the publication of his successful novel Venture to the Interior in 1952. In that novel van der Post fictionalised the events of an actual expedition up Mount Mlanje in Nyasaland (now Malawi), during which a young forestry officer is killed in a flash flood. As Jones has written,

Venture to the Interior marked the beginning of Laurens's reputation as an 'explorer', which he would build on in the subsequent ten years when he turned his attention to the Kalahari Desert. His publicity invariably described his as an explorer, and he was happy to accept the description, but in truth his career, however distinguished, could never class him with the Livingstones, Spekes, Burtons, Thesigers.39

The process of self-mythologising begins in episode one when van der Post recalls how his decision to go in search of the Bushmen was inspired by a 'tall, tanned, rugged and lean' frontiersman-hunter who paid a visit to his family and recounted how he had just seen 'true' Bushmen in the Kalahari desert. Furthermore, van der Post describes one of his fellow expedition members as in Lost World as a 'sort of Afrikaner Allan Quatermain', referring to the ubiquitous hero of many of Rider Haggard's African adventure stories. In episode two, van der Post furnishes the expedition with its own historical significance, pointing out in the narrative that they were departing from Victoria Falls in Zimbabwe 'almost a hundred years to the day' after Livingstone departed from the same place. He also sets himself up as the 'civilised' Livingstone, an icon of British exploration, setting out into unknown, dark Africa to 'discover' the Bushmen and bring back his discovery to his television audience. In so doing van der Post places himself and his expedition into the category of great explorations of the past, lending significance to the expedition that it did not necessarily warrant. The repeated references to frontiersmen, adventurers and explorers in Lost World of Kalahari set the tone for van der Post's most important projection: that of himself as the brave, intrepid hunter-explorer, a motif that would have been easily recognisable to a British audience in the 1950s.40Critics regularly compared van der Post's novels to those of Rider Haggard's, so that the connection between them had already been made before the Lost World series was broadcast.41

It is interesting to note that by the 1950s King Solomon's Mines had twice been made into successful feature films. The 1937 version starred the famous African-American actor Paul Robeson in the role of Umbopa and the 1950 version starred Stewart Granger and Deborah Kerr. At the very least it can be argued that Lost World's claim to authenticity was corroborated by the fact that the van der Postian notion of Africa as the untrammelled, mysterious realm of other-worldly people had a long literary and even a filmic tradition.

The literary allusions in Lost World are also imbued with a unique theme by van der Post, who identifies himself with the Afrikaner trekboers from whom he was descended. The expedition sets off with the white members 'humming trekker tunes'. Afrikaans folk music plays on the soundtrack as the Landrovers are filmed driving off into the distance. In van der Post's search for the Bushmen, he evokes his Afrikaner heritage at two levels. At one he articulates - in the voice-over narrative - his need to search for the remnants of a people in whose massacre his Boer forefathers in South Africa had played a part, which frames the expedition as a search for redemption from history. At another level, he consistently identifies with Afrikaner culture. This is evident visually, verbally and in the soundtrack of Lost World. For example, in episode one, van der Post explains to his audience that he is 'born of an old South African pioneering family' and that his 'people have been in Africa for over three hundred years'. He reminisces about his childhood on an African farm, presciently named 'Boesmansfontein'. Throughout the film series he wears 'veldskoene' and the khaki safari suits favoured by Afrikaans farmers in South Africa. As such van der Post positions himself uniquely in relation to his goal of finding the Bushmen, for he frames himself as a white African who has a cultural and historical connection to the land he now traverses in his quest for them.

Van der Post's timing here was crucial. As Bickford-Smith has argued, until the early 1960s there was still a tendency in the west to depict Apartheid South Africa without overtly vilifying the Afrikaner government. After the horrors of the Sharpeville massacre had been screened around the world, opposition to Apartheid intensified dramatically, and certainly by the 1980s Hollywood films, for example, tended to depict all white South Africans as evil. Afrikaans white South Africans in particular, were crudely stereotyped as oafish brutes.42 Had Lost World been made a decade or more later, van der Post's pride in his Afrikaner heritage would undoubtedly have raised the ire of western audiences.

The myth of van der Post, as built upon literary and cultural foundations, comes most clearly into focus during the Tsodilo Hills adventure in episode three. J.D.F. Jones has written that the entire Tsodilo Hills episode, as represented in Lost World, shows evidence of distortion and exaggeration, not least because van der Post claims to have discovered the hills and the rock art in their shelters. In reality, the Tsodilo Hills had been known to Europeans since at least the beginning of the century.43 If indeed the entire episode is exaggerated, then it must be asked: what did van der Post hope to achieve with this?

The answer may lie in van der Post's desire to project an image of himself as mediator between Western and Bushmen culture. He certainly expressed such an idea about his self-identity in the 1990s, when he said to Jean-Marx Pottiez that 'I felt, or rather hoped, very much that I could be not a bridge in a grand sense but a sot of little rope-bridge between estranged cultures.' This was in response to Pottiez's query about van der Post being a 'footbridge between Africa, Asia, Europe and the Americas'.44 The Tsodilo Hills episode contains the only moment in Lost World of Kalahari where the power of the expedition's technology is overridden - by 'spirits'. Importantly, the spiritual resonance of the Tsodilo Hills is attributed to Bushmen cosmology. Samutchoso is not a Bushman, although he fervently believes in the power of the spirits. He informs van der Post that the Bushmen believe that it is at the Tsodilo Hills that 'the Great Spirit made the world'. In the voice-over narrative, van der Post implies that the spiritual power of the Tsodilo Hills emanates from the Bushmen rock art panel on the summit of the largest hill.

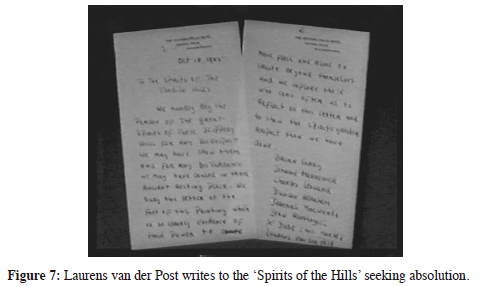

By petitioning these spirits for absolution for breaking the sacred law of the Hills, van der Post demonstrates a willingness to engage earnestly with the spiritual beliefs of the Bushmen whom he is seeking. In this way, he casts himself as the connective thread between Aboriginal Africans (Bushmen) and the West, between primitivism and technology, between spirituality and reason. The power of the film camera here should not be underestimated. By breaking down, the film camera is shown to be susceptible to the mystical power of the spirits of the Tsodilo Hills. Furthermore, the inclusion of the half-frames and jammed frames in the broadcast television series signifies that the evidence of this susceptibility is in the mechanism of the film itself. In this instance van der Post relies on the damaged frames to 'prove' the entire episode which is followed, as has been shown, by the expedition's shift to 'a new dimension of living'. For van der Post the filmmaking process was a useful means of showing his audience exactly what he was talking about: a mechanism not available to the writer of fiction, as will be discussed below.

Studying and 'Saving' the Bushmen

Lost World was made in the context of a growing scholarly and popular interest in the Bushmen that had developed in the interwar years. As Robert Gordon has shown, the interwar years saw the development of a discourse on 'saving the Bushmen'. This discourse, driven by white South Africans and heartily endorsed by the South African press, arose out of several live Bushmen exhibits organised by the prominent big-game hunter Donald Bain.45 At the 1936 Empire Exhibition in Johannesburg, Bain's Bushmen camp was the second most popular exhibit on offer. The pamphlet accompanying the exhibit described the Kalahari Bushmen on display as 'the last living remnants of a fast dying race' who were being exhibited as part of an awareness campaign aimed at getting them 'a home, a land, and the perpetuation of their race'.46 Bain sought academic support for his campaign to save the Bushmen, inviting expeditions from the Universities of Cape Town and the Witwatersrand to visit his Kalahari camp to study the Bushmen he had gathered together for the Empire Exhibit.47 Bain's efforts generated support at the highest level of South African society, with General Jan Smuts expressing his sympathy for the Bushmen - 'those living fossils'.48 Scientists in South Africa strongly supported Bain's request for the creation of a Bushmen reserve with Raymond Dart, then South Africa's foremost scientist, arguing for 'the establishment of one or more Bushmen Reserves in Southern Africa ... where the remnants of this fascinating human group of Bush peoples might be preserved for generations to come.'49Although limited in his success, Bain began a veritable trend of Bushmen exhibitions, culminating in the 1952 Jan van Riebeek festival in Cape Town, where the South West African pavilion included an exhibition of Bushmen under the supervision of the Chief Game Warden of South West Africa, P. J. Schoeman.50

Van der Post's proselytising in Lost World on the need to 'save the Bushmen' thus dovetailed with a growing conceptualisation of the Bushmen as 'a dying race' that needed to be 'saved' from becoming extinct. It is also interesting to note that the popularisation of this discourse was aided by the visual process of 'exhibition', which gave way to the tradition of documentary films.51 The Botswana born Louis Knobel produced a South African government propaganda film, Remnants of a Stone-Age People in 1953. The film, nominated at the Cannes Film Festival in the short film category, emphasised the immense primitiveness of Bushmen whose only hope of cultural survival was protected stasis: a point made strongly by shots in the film of the Bushmen Diorama at the South African National Museum in Cape Town. However, and importantly, the film displayed a compassionate tone towards its subjects, and applauded interesting elements of their culture, such as the making of arrows and the skill and endurance required for tracking and hunting.52 The timing of Lost World, then, needs to be considered in the light of this newer, idealised portrayal of the Bushmen.

The Politics of Primitivism

There is also an important political element to van der Post's mythologizing of Bushmen. Edwin Wilmsen has argued that by the 1950s 'anthropology had shown that 'tribal' peoples could no longer be thought of as developmentally primitive', and that a more informed reading public in Britain and America would question van der Post's nostalgic view of black people as 'modern exemplifications [sic] of pre-rational modes of thought'. Furthermore, argues Wilmsen, with the rise of African nationalism after World War II, black people, particularly the black working classes, could be seen as potential fomenters of rebellion. Van der Post needed, then, 'more plausible candidates for primitive exemplars than black Africans could be in the late fifties, hence Bushmen'.53 There is certainly evidence in van der Post's writings of his belief that the best thing about Africa and African society was its innocence and primitiveness. Revolutionary politics on the continent were, for van der Post, antithetical to this. For van der Post the grave danger in rapid decolonisation of Africa was the relegation of traditional African beliefs and political systems to the periphery in favour of political systems that were the children of the French Revolution. This, he declared in 1952, was the source of the 'great Illusion' that 'we are living in an age where conscious forces of reason are in control'.54 In a speech given to the Royal African Society in London in 1952 van der Post expressed his antipathy to the rapidly changing context of post-World War II Africa, insisting that

the black man needs a long sustained period of growth, of mental stability and security, of training and preparation and not this violent uprooting and transplanting overnight into social and mental soil alien to him. Given this, a hundred years or more can peacefully and gratefully go by before he will need many of the things which are now being wilfully thrust upon him.55

For him an Africa untouched by revolutionary politics was still 'in its age of innocence, still free of original sin', having 'not yet acquired an evil will of its own.'56 In Lost World this idea is epitomised by the domain of the Bushmen. As we have seen the 'wild Bushmen' sit around in the sun, behaving happily and peacefully, never having heard of time. This is Africa left to its own irrational and pre-modern devices: free and innocent of sin. 'Pristine Bushmen' were not just literary and philosophical figures for van der Post, but also a political construct: they were the evidence of what modern Africa was destroying, and what the world was losing in this process. Van der Post's idea of the 'real' Africa's innocence was timeous. As J.D.F Jones has written:

This decision [to go and find the Bushmen] is one of various examples in Laurens's life of his extraordinary gift for anticipating, and then responding to the new concerns of a new generation. When he wrote Venture to the Interior in 1952 his readers, weary of wartime drabness and insularity, were receptive to a tale of romantic and exciting adventure in the exotic location. Later he would understand the new interest in the life of C.G. Jung. Later still, he was in the vanguard of the Green movement, the concern for the 'Wilderness' and the environmental crusade. He had an uncanny instinct. But his advocacy of the Bushmen was a master stroke, echoing as it did the generation's nostalgia for a simpler, perhaps more innocent, society.57

Indeed, after World War II a change in Western images of Africa's landscape accompanied the continent's struggle for political freedom. Mitman argues that the 'dark continent' 'was rapidly transformed into a place of threatened ecological splendour - Africa and its wildlife offered respite from the anxieties faced by the generation living in the shadows of the atomic bomb'.58 This love affair with nature was facilitated by the growing popularity of television, films and literature documenting the work of people such as the Adamson's (immortalised in the film Born Free), the Denise's and the Harthoorns, who worked intimately with wildlife in Africa and documented the process of domesticating large mammals such as lions which had previously been seen as dangerous.59 Beinart argues that this process of domestication, with the emphasis on both the families of animals and the families of their human keepers 'struck a chord' with audiences during the conservative post-war decade in Britain and the United States, when stability was seen as important. Furthermore, for Western, particularly British, audiences the images of Elsa (the Adamson's' lion) and her cubs were a more comfortable vision of Africa than images of the Mau Mau in Kenya, Nkrumah in Ghana and Apartheid and the ANC in South Africa.60

Van der Post's pristine Bushmen lived in such an Africa, where the landscape, not politics, was god. They were the bearers of a unique and valuable culture that needed to be 'preserved', an idea which, as we have seen, had growing support in South Africa and amongst international scholars by the 1950s. The intrusion of other races, particularly modern black Africans, was seen as a threat to the stability and order of this old world. Van der Post was opposed to the wholesale importing of western ideas of democracy into Africa, believing, as we saw earlier, that Africa and Africans were not ready for this. In his Royal African Society speech of 1952, van der Post argued that 'Africa too has a political system of his own and in instances and vast areas I know it will serves his needs far better than any other would.'61

On the one hand, then, van der Post offered his viewers an image of Bushmen as 'wild men' or Noble Savages that had a long literary and historical tradition in the West, examples of which include literary creations such as Don Quixote, Shakespeare's Shylock, Caliban, and Othello, Swift's Yahoos, racial stereotypes from nineteenth-century 'science' and mystical figures from the romantic wildernesses of Blake, Byron, and Wordsworth.62 But what sets the film Lost World apart from this literary tradition, and gives it its own significance, is that van der Post was presenting to his television audiences an evidential portrait of his 'Africa-I-Know', one that was not suited to Western political systems or modernisation. After he is pictured driving away from the Sipwells, the film cuts to the studio, where he begins a passionate polemic on the 'process of elimination [that] is still going on in the Kalahari Desert', meaning the rapid changes occurring amongst Bushmen in South West Africa and Bechuanaland in the 1950s. Van der Post's protest reflects many of the sentiments from his 1952 speech:

We've stolen all the Bushman's best water, the black man and the yellow man and the white man. And the Bushman is still threatened. And what is more, he is administered by people who do not really care, who do not understand. Do you know that in the whole of the administration which administers that whole desert territory in your name and mine, there's not one man who speaks Bushman? There's not one man who really knows what they think, and what they feel? Do you realise that the game in the Kalahari desert is protected and the Bushman is punished, punished for hunting and killing the game, although he needs it for survival? And he who owned all that country, who was the lord of it all once, he has no such protection at all, he has no special rights of any kind.

He goes on to discuss the people he meets 'along the fringes of the desert', where there were 'signs of how this process of elimination by disintegration among the Bushmen was going on'. Here he saw

sordid, demoralised people, in the grip of the disdainful rag-and-tatters contamination of our own civilisation. I saw them work for a people who didn't understand them, didn't know their beginnings. I saw them as convicts in convicts' clothes, punished by laws they didn't make, in a language they couldn't understand. I found one oasis even, with a jail, to compel the Bushmen to live in a way which was not only not their own, but also a kind of death to them. I saw the deadly look of our own incomprehension and lack of imagination in so, so many things like these by the side of the long, long trail out and along the edge of the desert. I could not accept that this look that was imposed on those faces was the best that we could do. I could not accept that that reproach which was in those eyes should remain there forever.

The idea here is that Western civilisation in an African context is a 'contaminating' force, and that the administration of the Bushmen was being carried out by people who did not understand the reality of their subjects.

Van der Post's condemnation of the corrupt forces at work in Africa was more immediately convincing because of the film's documentary format. For the general public (to which these films were firmly aimed) the documentary film genre in the 1950s still constituted (and arguably still does constitute) one of the 'discourses of sobriety' as Bill Nichols terms it, whereby non-fiction films claim the ontological status of 'the real' for their subject matter and are seen, in Nichol's words, as 'serious' communicators of 'truth' or 'reality' along with other 'discourses of sobriety' such as science or history.63 Van der Post himself clearly believed in film as evidence that corroborated his message. In the closing moments of the film his concluding statement begins with the words: 'If what I've told you and what you've seen in these films can help you to bring back some hope to those disturbing Bushmen faces...'. Thus, the film format of Lost World was offering in evidential rather than speculative form van der Post's political and philosophical views on the Bushmen, views which formed part of a wider popular discourse about Africa.

Van der Post and the Anthropologists

It could be argued that van der Post's notion of pristine primitives was similar to that of anthropologists in the 1950s and 1960s. Studies such as the Marshall families' work on the Ju/hoansi Bushmen of Nyae Nyae in Namibia and George Silberbauer's work on the /Gwi of the central Kalahari focused on 'unacculturated Bushmen' living by hunting-and-gathering.64 It was not that the anthropologists did not know about the reality of most Bushmen in southern Africa at the time, of whom only a minority were hunter-gatherers - rather it was that the 'wild' Bushmen were considered to be worthy of study, both as a means of learning about their unique cultural practices and as a departure point for better understanding the more acculturated Bushmen minorities in the region, this being part of the then-valid project of 'salvage anthropology'.65 Alan Barnard has pointed to the affinities between van der Post's pristine Bushmen and the 'pristine' subjects of academic anthropological study, that 'widespread tendency in anthropology, including that practised by Bushmen specialists, to seek and find a purity which is not (simply) that of the Bushmen but often that of 'our dreaming selves'.66

However, these similarities were only superficial. Unlike the anthropological studies of 1950s and 1960s, van der Post's visits to the Bushmen were very brief: the time spent with the Bushmen for the making of Lost World was a mere two weeks. Furthermore, the purported isolation of van der Post's 'wild' Bushmen was an unlikely story. Van der Post's claims to 'discovering' Bushmen after a long, arduous journey out of time and through history need to be qualified. At the time in Bechuanaland (now Botswana), the inhospitable Kalahari Desert provided some protection to the remaining Bushmen bands who eked out a living by hunting and gathering in its centre.67 These people, all of whom lived in the Central Kalahari Desert, numbered around 10,022 in 1956.68 However, it appears that these bands could not have been the subject of Lost World. Van der Post's claims to have travelled to the very heart of the desert during his 1955 expedition are belied by his route map, which reveals that Lost World was filmed in the Ghanzi district. Here Van der Post would not have 'discovered' 'pristine' Bushmen in the 1950s. Ghanzi had been settled by Boer farmers since 1898 and by the middle of the twentieth century most Ghanzi Bushmen lived as impoverished and hungry squatters.69 The presence of a white farm building in the final sequences of Lost World (in the episode entitled 'The Great Eland') confirms the less than 'wild' and isolated nature of van der Post's Bushmen encounter.

What underwrote van der Post's view of the Bushmen (and Africa in general) was different to what underwrote the searching of anthropologists in the 1950s and 1960s. The vision of the anthropologists was according to van der Post,

generally associated with a renewal of the 18th century spirit of the 'noble savage' following World War II and with the "ban the bomb" movement in Britain, the civil rights and antiwar movements in the United States, the folk music revival, the rise and decline of the hippie life-style, and the emergence of a political "ecology" among the public to complement the Stewardian one among the professionals.70

These were not the values of van der Post. As we have seen, he emphatically did not embrace rapid change on the African continent that these very movements of the late 1950s and 1960s supported and gained inspiration from. As late as 1986, he adhered to the view that 'I think we should admit that in a way Africa was given a form of political government for which it was not ready and for which it is not yet prepared.'71

As argued earlier, his racial typography was out of touch with changing ideas about race after World War II as the Western world grappled with the aftermath of the Holocaust. In keeping with these changing ideas, anthropology after the war sought to de-emphasising race as a category and build understanding of other cultures through extensively debated research and writing. 72 In contrast, Van der Post's image of the 'pristine Bushmen', whilst perhaps similar to the 'pristine' focus of Bushmen researchers such as the Marshalls', George Silberbauer and Richard Lee in the 1950s and 1960s, was offered to the public as a redoubtable fact, evidence of racial essence that was entirely other to the West. And in Lost World, there does in fact appear to be a physical place and an actual people that evince the dream of a primordial, pristine Africa.

Conclusion

Lost World was followed in 1957 by American filmmaker John Marshall's study of the Ju/hoansi Bushmen of Nyae Nyae in northern Namibia, The Hunters. Whilst Marshall's film was the product of the Marshall families' amateur anthropological fieldwork and thus not a hymn to the imagined essence of Bushmen primitiveness, it did apparently reflect a similar kind of Bushmen to Lost World: hunting, gathering, singing, dancing, albeit in a far more subtle and interesting film.

The 1950s was thus a seminal time in the establishment of a pervasive Bushmen iconography that still captures the imagination today. Whilst the product of his own rather whimsical, even reactionary philosophy, van der Post's visualisation of pristine Bushmen seemed convergent with changing ideas about race, continued interest in the 'primitive' in academic anthropology, and changing ideas about Africa that obscured the reality of growing political radicalism on the continent. The mechanism of the film camera and the medium of television transplanted his imaginings about Bushmen around the world, which were further bolstered by his literary output. As one South African reviewer of van der Post's books wrote in 1955 'he may indeed have known such an Africa as he portrays here, but it had most certainly vanished long before 1948'.73 This quotation might easily be applied to Lost World. But the resonance of the television series, its ability to reflect and refract both van der Post's personal vision of Bushmen and Africa, and obliquely the tenor of the times meant that Lost World was a chimera which continued to contribute to the pervasive myth of Bushmen as pristine primitives for the rest of the twentieth century. The film was also a foreshadowing of the continued power of filmic images of Bushmen to define international perceptions about the Bushmen in the second half of the twentieth century and beyond.

* Many thanks to Andrew Bank and Vivian Bickford-Smith for their helpful comments on earlier drafts of this article.

1 These included The Heart of the Hunter in 1961, and later two substantial works of fiction with a Bushmen theme, the 1972 novel A Story Like the Wind and the 1974 A Far-Off Place. In 1975 he published The Mantis Carol, supposedly based on a true story. All four of these books were great successes internationally and remained in print for many years.

2 See A. Barnard, 'The Lost World of Laurens van der Post?', Current Anthropology, vol. 30(1), 1989, 104-14, E.N. Wilmsen, 'Primitive Politics in Sanctified Landscapes: The Ethnographic Fictions of Laurens van der Post', Journal of Southern African Studies, vol. 21(2),1995, 201-23; and E. N. Wilmsen, 'Primal Anxiety, Sanctified Landscapes: The Imagery of Primitiveness in the Ethnographic Fictions of Laurens van der Post', Visual Anthropology, vol. 15 (2002), 143-201.

3 See the lively debate on the question of film and history in The American Historical Review, vol. 93(5), 1988, 1173-1227. See also R. A. Rosenstone, Visions of the Past: The Challenge of Film to Our Idea of History (Cambridge, Mass., Harvard University Press, 1995).

4 D. MacDougall, 'Prospects of the Ethnographic Film', Film Quarterly, vol .23 (2),1969-1970, 16-30; D. MacDougall, Transcultural Cinema (New Jersey, Princeton University Press, 1993). On this debate see also for example J. Ruby, 'Is An Ethnographic Film a Filmic Ethnography?', Visual Communication, vol. 2(2),1975, 104-111.

5 See for example H. White, 'Historiography and Historiophoty', American Historical Review, vol. 93(5),1988, 1193-99.

6 See for example P. Smith, The Historian and Film (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1976).

7 See J.D.F Jones, Storyteller: The Many Lives of Laurens van der Post (London, John Murray, 2001). For a more deferential retelling see F. I. Carpenter, Laurens van der Post (New York: Twayne Publishers Inc.,1969). For a briefer summation see Barnard, 'The Lost World of Laurens van der Post?', 104-105.

8 J.D.F Jones, Storyteller, 1.

9 L. Van der Post, A Walk with a White Bushman: Conversations with Jean-Marc Pottiez (London, Chatto and Windus, 1986), 26.

10 Quoted in Wilmsen, 'Primal Anxiety, Sanctified Landscapes', 149; see also Jones, Storyteller, 214 regarding the dearth of interest in Bushmen in van der Post's earlier career as writer.

11 Van der Post, A Walk with a White Bushmen, 26.

12 Barnard, 'The Lost World of Laurens van der Post?', 104.

13 See R. J. Gordon, The Bushmen Myth: The Making of a Namibian Underclass (Boulder, Westview Press, 1992).

14 C. Schrire, 'An Enquiry into the Evolutionary Status and Apparent Identity of San Hunter-Gatherers', Human Ecology, vol. 8, 1980, 9-32; R. J. Gordon, 'The !Kung in the Kalahari Exchange: An Ethnohistorical Perspective', in C. Schrire (ed.), Past and Present in Hunter-Gatherer Studies (Orlando, Academic Press, 1984), 195-224; J. Denbow, 'Prehistoric Herders and Foragers of the Kalahari: The Evidence for 1500 Years of Interaction', in C. Schrire (ed.), Past and Present in Hunter-Gatherer Studies, 175-93; J. Parkington, 'Soaqua and Bushmen: Hunters and Robbers', in C. Schrire (ed.), Past and Present in Hunter-Gatherer Studies,151-74; J. Denbow and E. Wilmsen, 'Iron Age Pastoral Settlements in Botswana', South African Journal of Science, vol. 79, 1986, 40-8; J. Denbow, 'A New Look at the Later Prehistory of the Kalahari', Journal of African History, vol. 27(3),1986, 3-28, E. Wilmsen, Land Filled With Flies: A Political Economy of the Kalahari (Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1989).

15 Works on film representations of the Bushmen include E. N. Wilmsen, 'First People? Images and Imaginations in SA Iconography', Critical Arts,vol. 9(2), 1995, 1-27.; K. Tomaselli, A.Williams, L. Steenveld, R. Tomaselli, Myth, Race and Power: South Africans Imaged on Film and TV (Bellville: Anthropos Publishers, 1986), 77-101; K. Tomaselli, 'Myths, Racism and Opportunism: Film and TV Representations of the San', in Film as Ethnography, eds. P. Crawford & D. Turton (Manchester, Manchester University Press, 1992), 205-221. On the responsibility of film for generic depictions of Bushmen as pristine primitives see Wilmsen, 'First People?', 1-2; E.N Wilmsen, 'Knowledge as the Source of Progress: The Marshall Family Testament', Visual Anthropology, vol. 12, 1999, 229-32, 238-39, 244-46; Wilmsen, 'Primitive Politics in Sanctified Landscapes', Journal of Southern African Studies, vol. 21(2), 1995, 201-3; P. Skotnes, 'Introduction', in P. Skotnes (ed.), Miscast, 17, 20; K. Tomaselli, 'Introduction: Media Recuperations of the San', Critical Arts, vol. 9(2),1995, i; Gordon, Picturing Bushmen, 123-25; K. Tomaselli & J.P Homiak, 'Powering Popular Conceptions: The !Kung in the Marshall Family Expedition Films of the 1950s', Visual Anthropology, vol. 12, 1999, 160-61.

16 See J. MacDonald; M. Marsden; C. Geist, 'Radio and Television Studies and American Culture', American Quarterly, vol. 32(3), 1980, 301-304; and D. Singer and J. Singer, 'Developing Critical Skills and Media Literacy Amongst Children', Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, vol. 557, 1998, 165.

17 D. Herlihy, 'Am I a Camera? Other Reflections on Film and History', American Historical Review, vol. 93(5), 1988, 1189.

18 Jones, Storyteller, 225.

19 Jones, Storyteller, 225, 227.

20 Christopher Booker in The Spectator, 22 September 1984, quoted in Jones, Storyteller, 225.

21 Jones, Storyteller, 227.

22 Review from the Times Literary Supplement, 25 November 1958, quoted in Jones, Storyteller, 227.

23 Jones, Storyteller, 227.

24 Wilmsen, 'Primal Anxiety, Sanctified Landscapes', 178-80 and J. Marshall, 'Filming and Learning', in J. Ruby (ed.) The Cinema of John Marshall (Switzerland, Harwood Academic Publishers, 1993), 135-68. See also Jones, Storyteller, 238.

25 'The Royal Society Annual Report for the Year 1962', African Affairs, vol. 62(248), 1963, 190.

26 I.C. Jarvie, 'The Problem of the Ethnographic Real', Current Anthropology, vol. 24(3), 1983, 314.

27 L.van der Post, The Lost World of the Kalahari (London, Penguin, 1958), 13.

28 H. White, 'The Forms of Wildness: Archaeology of an Idea', in E. Dudley and M. Novak (eds.), The Wild Man Within: An Image in Western Thought from the Renaissance to Romanticism (Pittsburgh, University of Pittsburgh Press, 1972), 34.

29 E. Wilmsen, 'Knowledge as the Source of Progress: The Marshall Family Testament', 232-34.

30 Gordon, Picturing Bushmen, 114-16.

31 As I have argued elsewhere, it is possible that these contrived meeting sequences in films such as The Bushmen and Lost World of Kalahari were included for entertainment value, based on a long adventure and travel writing tradition, although for van der Post there is the added benefit of emphasising the other-worldliness of his Bushmen. See L. van Vuuren, 'The Great Dance: History, Myth and Identity in Documentary Film Representations of the Bushmen (PhD Thesis, University of Cape Town, 2006), 44-46

32 Examples of such idealisation (in subtly varied ideological incarnations) occur in films as disparate in origin and construction as the National Geographic film Bushmen of the Kalahari (1974), the South African documentary People of the Great Sandface (1984) directed by Paul John Myburgh and the internationally renowned South African documentary film The Great Dance (2000) directed by Craig and Damon Foster.

33 Alan Barnard identifies other literary precedents for van der Post's Bushmen adventures, including the writings of William Plomer, Roy Campbell, Olive Schreiner, Alan Paton, Herman Charles Bosman, Rider Haggard and William Burroughs. See Barnard, 'The Lost World of Laurens van der Post?', 107-108.

34 Also relevant is Sir Arthur Conan Doyle's The Lost World. Whether conscious or not, van der Post's choice of words certainly creates an indelible link between the novel and his film. In Conan Doyle's antebellum 'boys' book', the aptly-named Professor Challenger leads an expedition to discover the Amazonian lost world of the dinosaurs - to discover, as it were, 'living fossils'. The adventure-story atmosphere and the theme of a journey taken backwards through time to encounter a form of prehistoric - or ahistoric - life are shared by both Lost Worlds.

35 Jones, Storyteller, 213.

36 J. Conrad, Heart of Darkness, ed. R. Kimbrough (New York, Norton, 1972), 21-2.

37 H. Rider Haggard, King Solomon's Mines (London, Cassel, 1887).

38 Jones, Storyteller, 175.

39 L. Stiebel, Imagining Africa: Landscape in H. Rider Haggard's African Romances (London, Greenwood Press, 2001), xi-xii, 126-28.

40 Jones, Storyteller, 198-200.

41 V. Bickford-Smith, 'Screening Saints and Sinners: The Construction of Filmic and Video Images of Black and White South Africans in Western Popular Culture during the Late Apartheid Era,' Kronos: Journal of Cape History, no. 27, 2001, 183-200.

42 Jones, Storyteller, 220-23.

43 Van der Post, Walk with a White Bushman, 124

44 Gordon, The Bushmen Myth, 149.

45 R. Gordon, 'Saving the Last South African Bushmen: A Spectacular Failure?', Critical Arts, vol. 9(2), 1995, 29.

46 Gordon, The Bushmen Myth, 149.

47 Gordon, 'Saving the Last South African Bushmen', 32.

48 Gordon, 'Saving the Last South African Bushmen', 32.

49 R. Gordon, C. Rassool and L. Witz, 'Fashioning the Bushmen in Van Riebeeck's Cape Town, 1952 and 1993', in P. Skotnes (ed.), Miscast, 259-61.

50 Lauren van Vuuren, 'The Great Dance: Myth, History and Identity in Documentary Film Representations of the Bushmen', 224-239.

51 The only copy of this film that I've come across is a 16mm print at the Cape Town Provincial Library.

52 Wilmsen usefully points to a shift in van der Post's fiction between the late 1940s and late 1950s from a focus on black African characters, particularly Zulus, in his novels to Bushmen characters. Wilmsen, 'Primitive Politics in Sanctified Landscapes', 206. There are also interesting parallels with Wilhelm Bleek, the 18th century German linguist who transcribed !Xam Bushmen folklore, here. Bank argues that Bleek's emphasis on the rich imaginative life of 'Hottentots' and Bushmen was often cast in contrast to his dismissive view of the prosaic imaginations of Bantu-speakers addicted to ancestor worship. In many ways his views of Black Africans were not dissimilar from those of his friend and patron, Governor George Grey. See Andrew Bank, Bushmen in a Victorian World (Cape Town, Double Storey, 2006), 28-29.

53 L. van der Post, 'The Africa I Know', African Affairs, vol. 51(204), 1952, 217.

54 Van der Post, 'The Africa I know', 220.

55 Van der Post, The Africa I know', 221.

56 Jones, Storyteller, 214-15.

57 G. Mitman, Reel Nature: America's Romance with Wildlife on Film (Cambridge, Mass.,Harvard University Press, 1999), 190-91.

58 W. Beinart, 'The Re-Naturing of African Animals: Film and Literature in the 1950s and 1960s', Kronos: Journal of Cape History, no. 28, 2002, 213, 220.

59 Beinart, 'The Re-Naturing of African Animals', 220.

60 Van der Post, 'The Africa I know', 220.

61 M. Leaf, 'Review of The Wild Man Within: An Image in Western Thought from the Renaissance to Romanticism', The Journal of Modern History, vol. 46(2), 1974, 342.

62 B. Nichols, Representing Reality: Issues and Concepts in Documentary (Bloomington, Indiana University Press, 1991), 4.

63 See G. Silberbauer, Hunter and Habitat in the Central Kalahari Desert (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1981) and L. Marshall, The !Kung of Nyae Nyae (Cambridge, Mass, Harvard University Press, 1976).

64 R. Hitchcock, 'Socioeconomic Change among the Basarwa in Botswana: An Ethnohistorical Analysis', Ethnohistory, vol. 34(3), 1987, 221.

65 Barnard, 'The Lost World of Laurens van der Post,' 109.

66 The G/wi Bushmen were studied by George B. Silberbauer in the late 1950s.

67 Hitchcock, 'Socioeconomic Change among the Basarwa in Botswana', 241.

68 M. Geunther, 'From "Lords of the Desert" to "Rubbish People": The Colonial and Contemporary State of the Nharo of Botswana', in P. Skotnes (ed.), Miscast, 227, 233-34.

69 Barnard, 'The Lost World of van der Post?', 109.

70 Van der Post, A Walk with a White Bushmen, 87.

71 L. Lieberman; B. Stevenson; L. Reynolds, 'Race and Anthropology: A Core Concept without Consensus', Anthropology and Education Quarterly, vol. 20(2), 1989, 68-69; R. Lee, 'Art, Science, or Politics? The Crises in Hunter-Gatherer Studies', American Anthropologist, New Series, vol. 94(1), 1992, 32.

72 The Pretoria News, 2 May 1955, quoted in Jones, Storyteller, 202.