Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Kronos

On-line version ISSN 2309-9585

Print version ISSN 0259-0190

Kronos vol.32 n.1 Cape Town 2006

ARTICLES

'Some Sort of Mania': Otto Hartung Spohr and the Making of the Bleek Collection

Jill Weintroub

Centre for African Studies, University of Cape Town

This article1 tells the life story of Otto Härtung Spohr, one-time librarian and bibliographer at the University of Cape Town (UCT) Libraries, whose particular interest in Wilhelm Bleek had a profound influence on the making of UCT's 'Bleek Collection',2 and on the content, shape and form in which we find it today. I have pieced together my biography from correspondence and other records left in the OH Spohr Papers, a collection bequeathed to UCT Libraries' Manuscripts and Archives Department Spohr's wife, Charlotte, after his death in October 1980.3 The Spohr collection apparently remains in much the same form as it was when first presented to UCT twenty-six years ago. It is stored in 13 boxes, although Box 1 appears to be missing, and remains uncatalogued.4

The particular story of Otto Spohr, however, needs first to be situated within the more general context of the making of the Bleek Collection, and its development over time into the seemingly continuous, authoritative archive that we find today.5 Since 1997 the Bleek Collection has carried the appellation 'Memory of the World', a UNESCO-conferred accreditation indicating its status as a collection of 'fragile' documentary heritage of 'outstanding universal value', and which is 'part of the inheritance of the world'.6 The Collection was established some fifty or sixty years earlier through the donations of Dorothea Bleek, daughter of Wilhelm Heinrich Immanuel Bleek and Honorary Reader in African Languages at UCT from 1923 until her death in 1947. Her donations, comprising published and unpublished material as well as books and pamphlets dealing mainly with African languages, were made between 1936 and 1947.7 The books and pamphlets were catalogued and put into the appropriate section of the library's bookstock.8

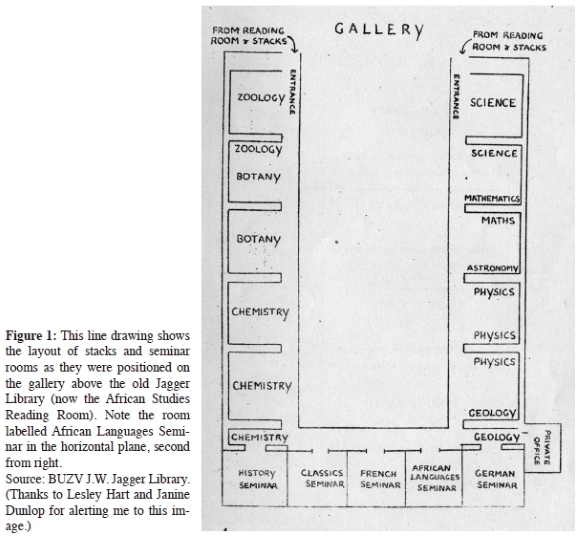

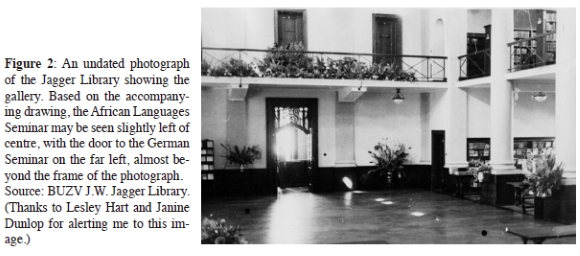

In the absence of a department dedicated to manuscripts at the time, it is likely that the non-book component of the nascent Bleek collection was stored, along with other manuscript collections, in 'cupboards, cabinets, and innumerable steel trunks throughout the Jagger Library'.9 It may be that part of the collection was housed in the 'Bleek Seminar', a classroom named in honour of Wilhelm Bleek in 1942 which was part of the School of African Life and Languages.10

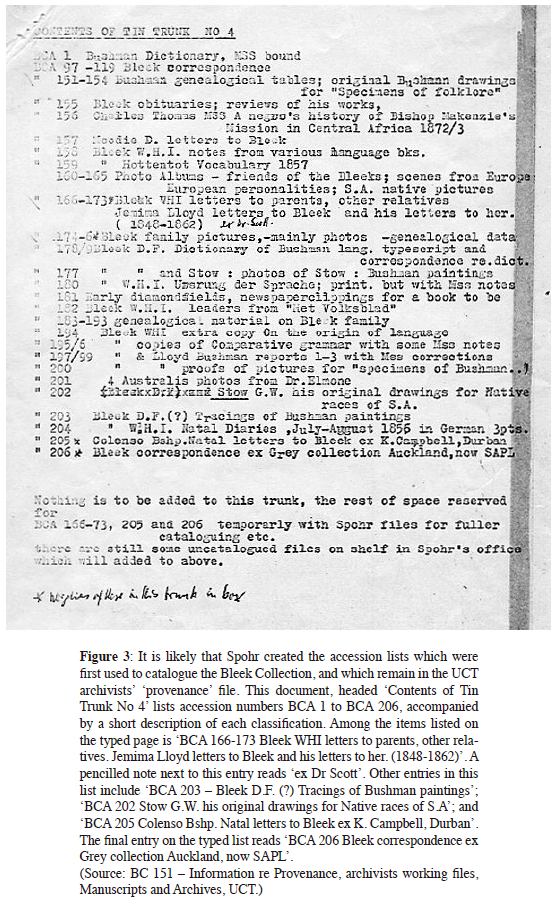

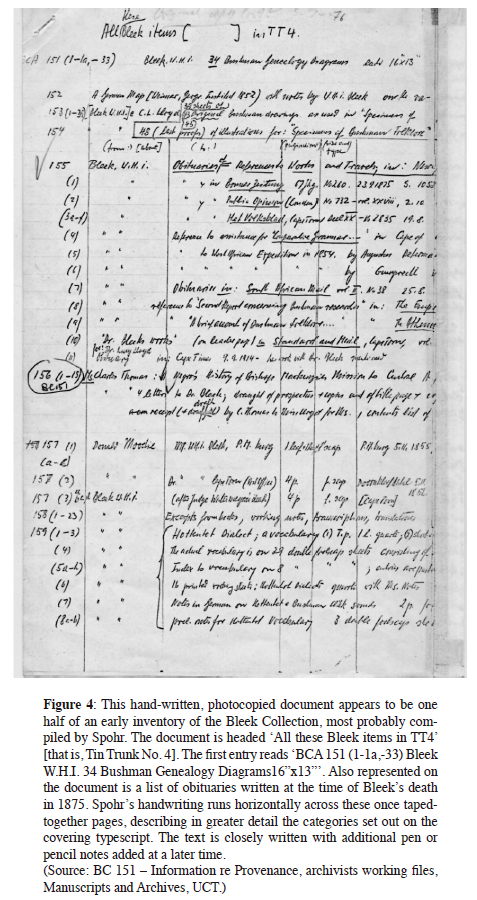

What is certain is that the Bleek Collection, despite periodic additions of material including personal correspondence and photographs, remained loosely ordered for many years. Etaine Eberhard, the librarian who worked with the collection during the 1970s and 1980s, remembered it being 'in a mess' during that time.11 Early documents of classification, probably compiled by Otto Spohr during the 1960s, remain as proof of the rudimentary nature of indexing in the 1960s.12

So the ordered index13 which researchers encounter today is a recent document, evidently compiled in 1992 to coincide with the conference on Bleek and Lloyd research which was held at UCT in September 1991.14 Both that conference and the new index to the Bleek Collection reflect how important the collection had by then become in academic circles. Yet, despite the critical importance of Otto Spohr's contributions of personal detail to the Bleek Collection, and the huge influence this has had for contemporary interpretations of Bleek-Lloyd material, his name is scarcely mentioned in the literature. In her paper on the provenance and cataloguing of the collection, delivered at the conference mentioned earlier, Etaine Eberhard, mentioned Spohr's work as a collector in the second part of a sentence.15 Elsewhere, Spohr features in footnotes citing his research related to Wilhelm Bleek's biography.16 In telling Spohr's story, then, this article seeks to give a sense of the contingent and highly personal narratives which may underlie the otherwise ordered process of archive making. In providing a particular example of a specific moment in the making of a collection, this article hopes also to illustrate the extent to which the haphazard, the spontaneous and the creative may be hidden beneath the structured documents of access which contemporary researchers encounter in the archive.

A researcher and an emigrant

Otto Hartung Spohr was born in Karlsruhe, Rein, on 18 November 1908. He completed his education at the Gymnasium in Heidelberg in January 1928, and that same year was admitted to the University of Heidelberg.17 At some stage during the course of his tertiary studies, Spohr also attended the University of Vienna.18Along with economics, the young Spohr studied philosophy, politics and related subjects.19 He obtained his Ph.D. in Economics from Heidelberg University in January 1932, and continued with postgraduate work in Berlin and Heidelberg.20As research assistant at the Institute for Social and Political Studies attached to the University of Heidelberg, Spohr's area of interest was the foreign trade policies of central and south Eastern Europe.21 Later, he specialised in the post-war (1914-18) industrial policy of Hungary. The Hungarian Institute at the University of Berlin later published part of his research in this project.22

Spohr's bibliography, compiled in Cape Town in honour of his 70th birthday, is testimony to a writing career spanning the years 1924 to 1978.23 His published works include articles written, edited, indexed and translated, and reflect Spohr's early interests in journalism and current affairs, as well as his involvement in student affairs.24 Spohr's interest in and aptitude for writing showed itself at an early age, and his earliest published article appeared when he was 16 years old.25 Later, his research activities from 1931 to 1934 saw him contributing articles and reviews to various German and south-eastern European economic journals.26

His life in Germany as well as his promising career as an economist appear to have been interrupted by the rise of Nazism. Perhaps it was because of the political pressure put on anti-Nazi academics, perhaps it was his blossoming romance with a German-Jewish woman that provided the impetus for the sea-change which occurred in his life at this time. Either way, the increasingly inimical political atmosphere in his homeland apparently forced Spohr's resignation from his research post at the institute attached to Heidelberg University.27 A bibliography of his work published much later refers intriguingly to 'a number of articles written by Dr Spohr after he resigned from Heidelberg University'.28 Their contents shall remain a mystery though, as years later Spohr expressly requested that they be left out of his commemorative bibliography.29 His reasons for excluding the documents must remain speculative - his personal papers yield no clues, apart from the fact that the articles were apparently 'written purely for remuneration'.30 It is unlikely, given the atmosphere in Germany at the time, that Spohr would have made his dissident political feelings public via the pages of a newspaper or journal. What is likely, however, is that Spohr supported himself through his journalism during this time, as we do know that the excluded articles were dated 1934, the year of his final departure from Germany.31 Clashing political ideologies in his professional life aside, it is also possible that Spohr's marriage in England in 1935 to the German-Jewish Charlotte played a role in prompting his departure from Germany.32 Interviewed years later, a former associate of Spohr's at UCT Library clearly remembered that Spohr's marriage to a Jewish woman was the reason for his departure from Germany in the 1930s.33 We can also be sure of Spohr's liberal political views, which, during the 1960s, he describes as being opposed to those of the South African government's.34

On this point, however, the archive again remains incomplete, as there is no specific reference in Spohr's personal papers to what must have been a traumatic time in his life. The typed curriculum vitae that he wrote years later glosses over what must have been a painful departure from the land of his birth, simply recording that he 'emigrated in 1934 to England and eventually to Cape Town'. 35 According to the obituary that appeared in the Cape Times in 1980, Spohr left Germany for England in 1935 to marry his German-Jewish wife Charlotte, and the couple arrived in Cape Town in 1936.36

A journalist and a conscript

While we do know when the newly married Otto and Charlotte arrived in Cape Town, the detail and texture of their early life together remains a subject for conjecture. The personal papers donated to UCT much later by Charlotte Spohr are also silent upon the couple's early life in Cape Town. Snippets of events and occupations do emerge, however. One is that Spohr joined the Cape Times in 1937.37It seems his experience of journalism in Germany provided the skills necessary to gain employment in his new country. One may safely assume that Spohr took to his new job with great energy and enthusiasm. He extended his writing skills and embraced photography in the course of his work as a journalist. Whether Spohr was building on a hobby or skill in photography acquired earlier in Germany, or whether it was more a matter of rising to a new career challenge with what later became his characteristic enthusiasm, cannot now be said with any certainty. What is clear is that the photographic experience Spohr acquired at this time was to have a profound influence on both his wartime and post-war careers.

While working as a journalist Spohr retained his earlier academic interest in economics and, in 1938, he addressed the Economic Society of South Africa in Cape Town, on the topic of economic reconstruction. His talk was titled 'The Economic Reconstruction of Hungary after the War'. An undated, unidentified newspaper report announcing the event and accompanied by a head and shoulders photograph of Spohr (below) described him as 'a specialist on the political and economic conditions in the Balkans' who was 'earning his living in Cape Town as a Press photographer'.38 The report paid specific attention to Spohr's refugee status, describing his relocation to Cape Town as 'another illustration of the difficulties that beset those whose consciences are not easily squared'. The Cape Times of 23 April 1938 carried a report after the event, quoting Spohr suggesting that Hungary was 'little more than a colony of great Germany'.39 It further reported Spohr's suggestion that Germany, France and Italy had, since World War I, 'expended vast sums' to prevent the Danube countries from uniting for their mutual benefit.

Spohr's career as a reporter and photographer was interrupted by World War II. Given the evidence we have of Spohr's politics, it is no surprise that he joined the Union Defence Force in 1940. His own records blandly state that he was 'on active service chiefly in the Middle East'.40 Elsewhere, he writes of serving in East and Central Africa as well.41 The Cape Times would later report that Spohr became an official photographer for the South African Defence Force during the war years. 42

Working for UCT Library

On his return to Cape Town after demobilisation, Spohr's life took a turn in another direction, one which would see him drawing on his past academic and research experiences in Germany, as well as on his more recently acquired photographic skills. It was in 1945 that he joined UCT Libraries, embarking on a new career which would see him travelling widely both within South Africa and abroad, as well as producing certain publications which remain important to contemporary researchers. Spohr threw himself wholeheartedly into his new career and, with characteristic dedication, soon achieved formal qualifications as a librarian. Starting off as a second-grade library assistant in 1945, Spohr gained his Higher Diploma in Librarianship in 1947 at which time he was made a first-grade assistant.43Spohr's own records state that he 'took the Diploma course in Librarianship in his spare time'.44 Drawing on his previous photographic experience, Spohr, working one morning a week, developed UCT Libraries' small photographic unit into a fully-fledged documentation centre, the first of its kind in southern Africa.45 He pioneered the use of document reproduction in university libraries in southern Africa, and wrote widely on the use of photography and copying techniques.46 Among his earliest writings in this area, his paper titled 'Some Technical Aspects of Micro-photography', was presented to a meeting in Stellenbosch of the Cape branch of the South African Library Association (SALA) on 6 April 1946. It was published in the journal South African Libraries (14, 2), in October 1946. Two years later his paper 'The Camera in the Library' appeared in the same journal (16, 3-4).

Just five years into his new career in libraries, the year 1951 proved to be a watershed one for Spohr. Not only would he embark on a stimulating trip abroad, but he also got the opportunity to renew contacts with friends from his student days and to re-visit his beloved south-eastern Europe for the first time in nearly 20 years.47 What began as a five-month study tour to documentation centres in the United States and Europe ended with Spohr spending several additional months in Belgrade as part of a UNESCO mission to establish a document centre in that country. Spohr's 'tour of study' to documentation centres in Europe and America was funded by the Carnegie Corporation of New York.48 He left UCT in December 1951, and, in less than five months, travelled to more than 15 different countries, and visited more than 100 libraries and institutions.49

Spohr chose to frame the trip in terms of extremes of direction, an apt way of conveying a sense of the distances he covered, and the many modes of transport he used: 'The most southern point was my 'home' library in Cape Town, the most northern the bookstall on the airport in Iceland, the most eastern library I saw in Zanzibar ... ; the most western was the library of Monmouth College in Illinois; the hottest in an excellent museum in Dares [sic] Salaam; the coldest was the news-stand in Goose Bay, Labrador; the largest the Library of Congress and one of the smallest the four-lingual ship's library of the boat that took me round East Africa through the Mediterranean to Europe.'50 This description of his travels appeared, together with his photograph, in the American Library Association Bulletin under the title 'Cape Town - Chicago - Belgrade' (below).51 The article, written from his hotel room in Belgrade, clearly reflects the sense of nostalgia Spohr felt at being back in Europe. He writes warmly of the dance, art and culture of Belgrade, as well as of the 'technical and scientific documentation' aspects of his trip as 'direly necessary in a country which strains every ounce of energy to rebuild the colossal war damage, to wipe out illiteracy, to modernize agriculture and to develop its rich industrial resources'.52

As it turned out, Spohr was able to spend a considerably longer period of time in his much loved Belgrade when, on completion of the study tour, he was invited to join a UNESCO mission aimed at providing technical assistance in documentation in Yugoslavia.53 This appointment followed Spohr's earlier visit to UNESCO's Paris headquarters where his name had been submitted as a potential team member. Although not specifically stated, his German birth, academic background and knowledge of Eastern Europe must have played a role in this selection.

That the trip was a profound emotional experience for Spohr seems safe to surmise. It was, after all, his first return visit to the country he had fled from years earlier. He wrote with nostalgia of the 'ice cold wind coming over the Rhine - my first real winter again after 18 years in South Africa'.54 In his months of travel through Europe and America, he made many new contacts in the world of librarianship and documentation services, and, in a series of chance meetings, reconnected with some old friends. One of the old friends from Spohr's 'varsity days' was now a professor in a small college town in Ohio. The two talked of their 'old days' in Berlin, Heidelberg and Budapest, and of Spohr's 'old love for the South East of Europe', an area he was soon to revisit. Also by coincidence, Spohr met a second student friend, who was now professor at MIT's School of Architecture.55 The two had parted in London 18 years previously, the professor to go 'with the Bauhaus' to the United States, Spohr to 'try his luck' in South Africa.56 That this trip was immensely stimulating professionally can be deduced by his prolific output on the topic of reproduction and documentation services.

The 1950s, then, proved to be a time of career advancement for Spohr. He took great pride in the technical strides made by UCT Libraries' photographic department, which under his direction offered the latest equipment and a high standard of document management.57 At the same time, he broadened his photographic and documentation interests to include bibliography, and began publishing in the area which was to become his speciality in the 1960s. In 1954, Spohr collaborated with Douglas Varley, then librarian at the SA Public Library, on an article published in the journal South African Libraries, entitled 'Some Proposals for the Development of National Bibliographical Services in South Africa'. The published article was based on papers read at the Conference of the South African Libraries Association held in Bloemfontein on 28 September that same year.58 Between 1946 and 1968 Spohr contributed some 70 articles on documentation and bibliography to South African and overseas library-documentation journals. And, while in charge of photographic services, he made close contacts among the academic staff at the university. Years later, Spohr remembered Professor Erik Chisholm as 'a frequent and very much liked visitor at the photographic department of the University library'.59Tellingly, he also remembered his department as being the only one 'where all the persons who wished to do so could smoke as much as they liked', although not in the interleading passages.60

Private life

The events of Spohr's personal life are much harder to piece together, and the archive is virtually silent on aspects of marriage and family. It seems reasonable to assume that Charlotte assisted Spohr in his reseach projects, providing typing and translations when necessary. There are suggestions to this effect in his correspondence, and a direct acknowledgement of her assistance in Natal Diaries.61 We have no idea, for instance, whether Charlotte accompanied Spohr abroad, nor whether she joined him during his extended stay in Belgrade while assisting UNESCO. Years later Spohr offered to write a newspaper article about a South African family's experiences in Tito's Yugoslavia, so it seems that his wife and young daughter did join him in Belgrade from 1952-53.62

Although we know that Spohr became a father, it is difficult to pinpoint exactly when this occurred. Indications are that it was early in his marriage, as, in an undated curriculum vitae prepared by Spohr to accompany his application for the position of sub-librarian of the Medical School, Makerere College, Kampala, Uganda, Spohr describes himself as married with a 19-year-old daughter then studying in London.63 It seems logical to assume that the position of sub-librarian is one that would attract a mid-career applicant. From this we can suppose that Spohr daughter was born within a year or two of his marriage to Charlotte in 1936, or perhaps just before he went to war in 1940. This would make it possible for Helen to be a young adult by the time her father begins to look for greener career pastures, perhaps during the late 1950s when greater disillusionment about his career at UCT begins to set in.

We can, on the other hand, be certain about the year, 1965, in which Spohr becomes a grandfather, as he writes proudly of this fact to his old friend and associate from the SA Public Library Douglas Varley.64 Indeed, it is through the warm correspondence between Spohr and Varley (himself the father of three daughters), that we are allowed the occasional glimpse into Spohr's private life. In a correspondence spanning the best part of 10 years, we learn about Helen crewing on a yacht sailing round the world, qualifying as a occupational therapist, and finally, settling down with a husband who works in telecommunications.65 By December 1966 Spohr's daughter, now identified as Helen Raggett, was the mother of two boys and living in the village of Witten, in Essex.66 By 1979, she had three sons and was living in the country outside Chelmsford.67

Exactly where the Spohr family lived in Cape Town is not clear either, although one may assume they lived in Rosebank, a pleasant suburb on the eastern slopes of Devil's Peak within easy reach of UCT and, coincidentally, a stone's throw from both of the Bleek family's residences at nearby Mowbray. Today Rosebank is dominated by student residences and official university administration buildings and recreation facilities, as well as a number of once impressive, now slightly faded, double-storey Victorian villas. Correspondence in Spohr's personal papers emanates from two addresses close to UCT. Certainly, the couple lived at 'Hillrise', Cecil Road, Rosebank, during the 1960s. Perhaps the house was next to or close to the Irma Stern Museum, which remains a landmark in Cecil Road. However, no obvious trace of 'Hillrise' itself remains, although there is a Hillcrest Primary School in Cecil Road. Around the corner is the Spohr's later home, 10 Wolmunster Road, Rosebank. The solid, single story Victorian, now partly hidden behind a vibracrete wall, was their home during the later 1970s until Spohr's death in 1980.68

In the end, one can only guess as to the reasons why so little personal detail is contained within Spohr's papers. What can be said with some certainty is that the 1950s, which began on such a high note for Spohr, ended rather differently, as the next section in his life shows.

Bleek mania

By 1962, Spohr had worked for UCT's Jagger Library for 17 years, and there is evidence that cracks are developing in his life. Spohr mentions a 'nasty accident', possibly a motor vehicle accident related to alcohol abuse, in the late 1950s which may have incapacitated him for several months.69 His return to work after this absence seems to have occasioned a demotion from the photographic department to an office on his own. Here, he appears to have become responsible for compiling bibliographies and catalogues, or, as Spohr himself put it, moving 'from the job of being the head of the largest library department to being all on my own in an office which was supposed to be a women's toilet, but was used to store surplus stationery'.70 Years later, Spohr would blame his superior's conversion to Catholicism for prompting his redeployment.71

So it seems that the start of serious research into Wilhelm Bleek's life marked a turning point in Spohr's own. His interest in Bleek, and in German Africana in general, appears to have flourished while he was waiting 'for the powers that be' at UCT Library to tell him 'what they have decided about my future'.72 It is at this point that a coincidence of academic research, personal interest and wider political machinations occurs - with a productive outcome for the Bleek Collection as it is now constituted. So it was that between his first research trip to Germany in 1959, and the appearance of Natal Diaries in 1965, Spohr's determined research into Wilhelm Bleek made a substantial contribution of personal correspondence, photographs and other material, to the dry collection of manuscripts, reports and philological books which Dorothea Bleek had donated to UCT Libraries years earlier.73 A bibliophile to the core, Spohr's dedication to the task of gathering material on Bleek led him to visit libraries and archives in Natal and in Germany. Moreover, Spohr's professional interest in the use of photography and copying techniques in libraries led to material from other collections being reproduced for the collection at UCT.

From the 1950s onwards Spohr's was increasingly involved in what was to become the great passion of his later life - the area of German Africana. This interest seems to have been sparked initially by Spohr's research around early librarians at the Cape.74 Initially, the object of his research was Joachim Nikolaus von Dessin, whose bequest of his personal library, initially to the Dutch Reformed Church in the eighteenth century, became the founding collection of the South African Public Library in 1818.75 Spohr's research on Von Dessin was published in the Auslandskurier of 1961, and he also contributed an article on Von Dessin to Behaim-Blatter fur die Freunde des Deutschen Buches.76 Von Dessin, the SA Public Library and German librarians led logically to Wilhelm Bleek, and in the UCT research report for the period 1959-61, Spohr is listed in the biography section as being in the process of compiling a bibliography of materials in Cape Town libraries relating to Dr W H I Bleek.77 In the same report, he is listed in the Africana section for an article on German Africana.

By 1964, Spohr describes his interest in Bleek as 'some sort of mania'.78Spohr's fascination with Bleek sprang from his admiration for Bleek's librarianship, their shared nationality, as well as a shared political liberalism. Spohr would later write an article about Bleek's leader page contributions to Het Volksblad in the mid-1860s, drawing particular attention to Bleek's liberal racial attitudes.79 In another article (written to mark the 150th anniversary of the founding of the SAPL), Spohr framed Bleek as the first 'special librarian' in South Africa.80 Elsewhere, Spohr wrote that Bleek, while librarian of the Grey Collection at the SAPL, had collected the incunabula of African languages.81 On a more prosaic level, moreover, there is ample evidence in Spohr's personal correspondence of how much he enjoyed the detective work associated with unearthing previously hidden information about historic figures such as Bleek. There was also the excitement of overseas travel. With funding from UCT and the German government, Spohr took at least two trips to Germany to research Bleek and other Germans at the Cape.82The visits, in 1959 and 1963, gave Spohr an opportunity to meet descendants of Wilhelm Bleek's family in various parts of Germany and to obtain many personal documents relating to WHI Bleek.83

On his first visit to Germany, Spohr obtained from 'the late Mr KT Bleek' in Marburg, West Germany, among other items, the familiar portrait photograph of Wilhelm Bleek that was used as the basis for the Cape artist William Schreuder's posthumous sketch.84 The widely published portrait photograph of Jemima Lloyd, taken in Bonn in 1862 to send to Wilhelm in Cape Town during their courtship, was also obtained from Mr K T Bleek,85 possibly on Spohr's second trip to Germany which took place in October and November of 1963.86

Between trips to Germany, meanwhile, the cultural and political landscape in Cape Town offered an urgent incentive for Bleek research. This impetus for an all-out search for Bleek material was initiated as part of UCT's contribution to cultural activities organised by the German Embassy in Cape Town in 1962.87 Spohr was commissioned to produce a publication on Bleek as part of this initiative.88With bibliographical research already in process, Spohr clearly tackled the chaotic Bleek collection at UCT with renewed energy. His first major find was a series of travel reports that Wilhelm Bleek had written while travelling in Natal during 1855 and 1856, and which had appeared in Germany in the magazine Petermann's Geographischen Mittheilungen. Further searching in 'the Bleek papers at Jagger' revealed part of a manuscript diary which Bleek had kept in 1855.89 On another occasion, Spohr found a packet containing 100 or so handwritten manuscript pages in German which turned out to be the diary that Bleek had kept while travelling in Natal.90 He also discovered 'some pencilled extracts from Bleek letters' which Jemima Lloyd had made. These notes dealt with Bleek's pending appointment as Grey librarian and with the publication of Bleek's A Comparative Grammar of South African Languages in 1862.91

Spohr's most rewarding discovery took place at the SAPL where he uncovered 'a great many letters which the Auckland Public Library in New Zealand had sent on exchange from their Grey Collection to the SA Public Library in 1956'.92Altogether 25 letters written by Dr Bleek between 1857 and the year of his death were found among "some 210 lots of 'African letters', most of them written to Sir George Grey by his friends and acquaintances in Africa".93 These letters are still among the most widely cited of Bleek's correspondence.94

The outcomes of this period of detective work appeared in Spohr's first publication on Bleek, Wilhelm Heinrich Immanuel Bleek: A Bio-bibliographical Sketch (Cape Town: UCT Libraries, 1962). He completed it just in time to present the first copy to the German consul in Cape Town on the opening day of the Art Weeks in June 1962.95 At that point, however, Spohr was unable to 'trace any further diaries or published letters after May 1858, the date of the last letter to Bleek's parents ... till the time of his death in 1875'. Despite the dedicated detective work described above, he had to be satisfied with 'an occasional glimpse' into Bleek's private life, since by far the greater part of the correspondence available at that time dealt with Bleek's linguistic researches and his duties as curator of the Grey collection.96Spohr documented his frustration over the separation between the personal and the professional - the lack of personal detail in favour of emphasis on Bleek's scholarly achievements.97

Thus, the bibliography was offered as a work-in-progress and in it, Spohr appealed for more information about Bleek. His appeal bore fruit, and in an article written soon afterwards for UCT Libraries' staff publication, The Jaggerite, Spohr reported important new finds.98 Dr KFM Scott (one of Bleek's granddaughters), coincidentally then at UCT's Zoology Department, responded with 'a promise of photographs and possibly some letters'. These turned out to be the now very familiar photographs of the Bleek residences in Mowbray, several family photographs, and, most important of all, the letters exchanged between Wilhelm and Jemima between April 1861 and October 1862. This extended courtship by correspondence between the two remains the basis of contemporary knowledge about the family background of the Lloyd sisters.99 A second response to the appeal published in the bibliography came from Dr Killie Campbell, who notified Spohr regarding '150 letters written by Bishop Colenso to Dr Bleek' which were in her Africana library in Durban.100 Spohr later travelled to Durban to have the letters, written between 1854 and 1872, 'filmed' for UCT's collection.101 Also around this time, Spohr unearthed Bleek's contributions to Het Volksblad in a packet of newspaper cuttings among the Bleek papers at UCT.102

In the midst of all this activity, Spohr took his second trip to Germany in October and November of 1963.103 On this occasion, he met Wilhelm Bleek, son of the Rev F. Bleek, in Mehlem near Bonn. The young Wilhelm greatly assisted Spohr with his research, both into Bleek and into other aspects of German Africana. An envelope of photographs among Spohr's papers suggests that Wilhelm contributed portraits of Dr Philipp Bleek (brother of WHI), Edith, Margarethe, of WHI's father, and the very familiar one of an older Jemima Bleek.104

A graduate of the University of Berlin West with a doctorate in Political Science, the young Wilhelm used his position to cross the Berlin Wall and obtain copies of WHI Bleek's student record at Humboldt-University.105 These were kept at the Unter den Linden branch of Berlin University, east of the Brandenburg Gate, where Spohr himself was unable to go. With the help of other Bleek family members, Spohr discovered an extensive correspondence between WHI and his parents during his student and postdoctoral years in Bonn and Berlin. He also found a batch of letters which WHI had written to his parents in 1859-1860. They were written from Pau on the south of France while Bleek was on sick leave between two periods of work at the Grey library in Cape Town. Many are scarcely decipherable, and it is testimony to Spohr's zeal, and the graphological skills of one Mrs H R Gal, secretary to various language departments at UCT, that we have access to them at all.106

It may also have been on this second trip to Germany that Spohr travelled to Jena, made contact with the director of the Ernst Haeckel Archive, and arranged to have the correspondence between Bleek and his cousin copied for the UCT collection. Back in Cape Town, he received from Clason in the Argentine two letters from Miss Anne Bleek, a descendent of Wilhelm's brother Philipp. These were lengthy letters that Wilhelm had written to Philippe in Buenos Aires in 1858.107A series of letters in German, dated 1963, 1964 and 1965, addressed to Dr Otto Spohr of the University of Cape Town library, from Anne Bleek, remain as proof of Spohr's efforts throughout the early 1960s to build as complete a picture as possible of Wilhelm Bleek's life.108 Between travels and further research in Cape Town, Spohr found time to publish a paper on Bleek's Het Volksblad leaders,109 as well as a volume in German on Bleek's letters written to his mother and brother between 1858 and 1860, titled Briefe aus Pau: W HI Bleek an die Mutter und den Bruder in Buenos Aires.110 These letters revealed that Grey was interested in exchanging 'the greater part of his Africa Collection' with the British Museum, although this never came about.111

The letters that Spohr tracked down during this period remain the basis of our knowledge about the life of Wilhelm Bleek. There are batches for every period of his life, apart from his childhood. His student years are documented in the letters written to his parents between 1848 and 1853; his travels in Natal are covered in the letters-cum-field reports that he wrote to Petermann and his parents in 1855 and 1856; his subsequent work with Governor George Grey in Cape Town (1857-59) can be traced in his letters to his parents and brother in Argentina; his year of recovery in Pau in letters home; his life and work in Cape Town in his letters to Jemima Lloyd from 1861-62. From 1863 until August of 1869 when he took /A!kunta into his home, we have his letters to Grey and to Haeckel.

German Africana

By the mid-1960s, Spohr was appeared to be settled in his new position at the library. He was corresponding widely with academics, publishers and journal editors, both within South Africa and internationally, in accordance with his abiding passion of codifying a genealogy of Africana materials, and in particular, in furthering his interest - both professional and personal - in German Africana. Like Bleek before him, in the course of his duties as librarian and archivist, Spohr compiled bibliographies, indexes and catalogues. His private papers attest to the great variety of his research interests at this time. Among early bibliographies compiled by Spohr are a guide to 'Pictorial material of Cecil J Rhodes, his Contemporaries and later South African Personalities in the C. J. Sibett Collection of the University of Cape Town Libraries' (with EO Stubbings) in 1964, and in 1967, 'Recent Indexes to Africana Books'.112 During the 1960s he was a prolific contributor to the Quarterly Bulletin of the SA Library. Like Bleek, who wrote regularly for the Cape Monthly Magazine, Spohr wrote articles on a variety of topics related to his research of the moment, and to his passion for German Africana. Some of these articles dealt with Wilhelm Bleek and his work at the SA Public Library. For instance, in vol. 19 no 2 of 1964, Spohr contributed an article entitled 'Miscellaneous Notes on Some Libraries, Book Sales and Early Authors in Cape Town in the Early 19th Century'. In a contribution to Russian Africana, Spohr published an edited version of the story of the detention of the imperial Russian sloop Diana in Simon's Bay between April 1808 and May 1809. Spohr's edited and annotated version of the manuscript written by VM Golovnin was published in 1964 by the Friends of the SA Library under the title 'Detained in Simon's Bay: The Story of the Detention of the Imperial Russian Sloop Diana, April 1808 - May 1809'.113

Spohr collaborated with the noted amateur historian Frank Bradlow on an article on Johann Georg Rathfelder, which appeared in both local and German publications.114 His early translations of the manuscripts by Ferdinand Krauss appeared in Vol. 21 numbers 1 and 2 of the Quarterly Bulletin of 1966. In the earlier number Spohr also contributed an article on Zacharias Wagner. His book on Wagner appeared the following year: Zacharias Wagner: Second Commander of the Cape (Cape Town, Amsterdam: Balkema, 1967).115 In Vol. 21 no 4 of June 1967, Spohr wrote an article entitled 'The First Danish-German Missionaries at the Cape of Good Hope, 1706'.116 Furthermore, in the Quarterly Bulletin of 1968 (Vol. 23 No 2), appeared a paper on 'Dr. Med. Friedrich Ludwig Liesching, Eminent South African medical man and pioneer of South African horticulture'.117

On the Bleek front, the appearance of Natal Diaries in 1965 marked a crowning moment. In this publication Spohr framed Bleek in the tradition of the great African explorers: 'Our new traveller becomes now a member of a long line of German scientists in Central Africa, who from Hornemann down to Barth and Vogel have worked indefatigably on the discovery of the interior of a continent'.118As well as being a record of Bleek's sojourn in Natal the book may also perhaps be read as an expression of Spohr's own nostalgic feelings about the heroic explorers of Germany's past. Moreover, its publication just three years prior to Spohr's retirement from UCT Libraries, also marked a point at which other interests increasingly fragmented his attention. It is difficult to speculate what it was that led to the huge amount of energy invested in Bleek beginning to dissipate. Perhaps Spohr needed a new challenge. Perhaps his health was beginning to fade. Either way, a sense of disquiet creeps into his correspondence around the mid 1960s. By 1966, when his old library friend Varley and family had moved from the University College of Rhodesia and Nyassaland, to Liverpool University, Spohr wished that he too could leave 'this unfortunate continent'. At the same time, he expresses his pessimism about 're-armament' and the 'present trend in German politics'.119

Outwardly, however, he continued to hold his own. In 1967, a year prior to his retirement, Spohr is described as the 'only full-time bibliographer in South Africa' by a Mr Panofsky, librarian of the African collection of Northwestern University.120 In correspondence centred around unsuccessful attempts to attend the African Bibliographical Congress in Nairobi planned for December of that year, Spohr points out that his South African passport is likely to preclude his entering Kenya. He adds that his 'political views are not identical with those of the [South African] Government'.121

From 1968 onwards: retirement and private bookselling

By the time he retired in 1968, at the age of 60, Spohr appears to have earned an international reputation as a bibliographer. 122 UCT arranged to publish a bibliography listing the 100 or so articles and some books he had by then written, as a farewell gesture on his leaving the library.123 Later, however, Spohr would write that he had been 'dismissed from [UCT Library's] service after 22 years hard work because I was drinking and smoking too much'.124 Despite this, retirement saw Spohr embracing new challenges. He immersed himself in research and writing, and established a successful book selling business, specialising in Africana.125 An invoice book among Spohr's papers suggests the Chicage-based Africana Library of Noth Western University purchased books in 1971. He would later write that this early retirement allowed him to become 'one of the leading writers in the field of Africana'.126 In 1969, he was invited to join the list of specialist collaborators who were contributing to the Standard Encyclopaedia of Southern Africa (edited by P C du Plessis, published by Nasionale Boekhandel Bpk).127 He was to contribute a biography on Victor Lebzelter.

Spohr kept in contact with former colleagues at UCT. In 1970, he collaborated with then UCT librarian GD Quinn to compile a handlist of all the hand-written documents in what was then known as the Manuscript Collection of UCT Library - the first printed catalogue of its kind.128 In 1971 Spohr was awarded a 'Senior Bursary for Post Master's Degree Study and Training in Research Overseas' from the Human Sciences Research Council. The award was made for transcribing, translating and editing a 'practically unknown fragment of a manuscript by Dr MHC Lichtenstein on the history and colonisation and civilisation in southern Africa'.129 Spohr would later remember with pride the part he played in arranging for the 'one and only exisiting xerox copy of the Lichenstein [sic] manuscript fragment' from the Berlin Library to be lodged at UCT.130 In 1972 he contributed a bibliography on Lichtenstein's life to the Dictionary of SA Biography being published by the Human Sciences Research Council.131 Spohr also translated and published in various journals, Ferdinand Krauss' manuscripts about the Natal Voortrekkers and their war with the Zulus, as well as Krauss' description of the Cape and its way of life, and a fragment about the wines of Constantia.

In Vol. 26 no 2 of the Quarterly Bulletin of December 1971, Spohr published his translation of a letter from WHI Bleek to Martin Haug under the title 'Dr Bleek writes about Sir George Grey and the Grey Collection'. In notes to this article, Spohr acknowledges his Stuttgart friend and associate the now-retired Professor E Schütz, as being the source of the letter. A copy of this letter now resides in UCT's Bleek Collection.132 In Vols 28 no 2 and 29 no 2 (December 1973 and 1974 respectively), Spohr's translations of early letters by Fr. von Wurmb and Karl von Wolzogen appeared: 'Two letters from the Promontory of the Cape Written in March 1775 by Fr. Van Wurmb' and 'The Württemberg Regiment at the Cape. Letters of Baron von Wolzogen 1788-1789 (II)'.133

As the end of the decade approached, however, Spohr's health begins to fail. By 1978 he was housebound and suffering from severe emphysema,134 and looking for a buyer for his Africana collection of about 400 books.135 He had sold most of his collection to the Unisa Library by December and his bookselling business was effectively closed.136 Wheelchair bound and reliant on secretarial services as his health precluded him from typing or even answering his door, Spohr continued doggedly with research and correspondence.137 In 1979, despite 'slowly but surely deteriorating health', he began work on an updated and expanded version of his bibliography on Wilhelm Bleek.138 This book was to contain material not included in the first two publications, as well as articles on Bleek published subsequently by Spohr. It was to be edited by Etaine Eberhard.139

Sadly, ill-health intervened. The book never saw the light of day. The seriously ill Spohr had other matters to deal with, although it is clear that his Bleek research remained a source of pride right to the end. In a letter to his daughter and wife (then in Groote Schuur Hospital recovering from an operation, and under the care of Professor Bloch), written in June of 1980, Spohr mentions his own recent sojourn in hospital 'owing to some state of confusion'. He declares that he has given up drinking, and that he had given up smoking some years earlier.140 In another letter written at roughly the same time to Etaine Eberhard, Spohr expressed the satisfaction he felt at knowing how important WHI Bleek and the Bleek Collection had become. He made a point of emphasising his own contribution: 'You are the one who knows that I started the Bleek collection and made sure that photocopies are [sic] made of all the material and deposited with the department you are in charge of now.'141

Other correspondence expresses his sense of satisfaction at the 'continuous interest in Bleek' with enquiries coming from the US and the University of Edinburgh, and one researcher from Yale University using the collection at UCT.142Elsewhere, Spohr expresses his admiration for Bleek's librarianship, describing him as a beacon of expertise in the history of the South African Public Library: 'I was surprised to hear that poor Dr Robinson seems to be ill. I hope it is not serious and that he will eventually return to the library which he loved so much, and where he proved to be a very worthy successor to Mr. Varley, who after many years of neglect put the South African Library again where it stood in good old Bleek's day.' 143 In another personal letter written at the same time, Spohr again refers to 'good old WHI Bleek'. These letters ring with the poignancy of being written within a few months of Spohr's death - he died in October 1980.

Conclusion

Though seldom mentioned in the research and interpretative writing emanating from the Bleek collection, Spohr's interventions are materially represented in the Bleek collection in the presence of his research notes, which are included in the formal index to the collection. The abstracts, notes and lists Spohr made, probably while writing his bio-bibliographical sketch of Bleek, as well as his card summaries of the courtship correspondence between Wilhelm and Jemima, are to be found in the Bleek catalogue under the category 'Miscellaneous'.144 In addition, Spohr's notes on the correspondence between Bleek and Sir George Grey are included in BC 151 under the category 'Correspondence - W H I Bleek'.145 In the management of the collection also, Spohr's presence remains traceable. It is likely that Spohr was responsible for creating the accession lists which were first used to catalogue the collection. These remain in the UCT archivists' 'provenance' file.146Thus, though his contribution is rarely acknowledged, Spohr's presence is indelibly inscribed into the collection at UCT. This inscription may be read as telling slippage and overlap between the researcher and the object of his research, slippage which is testimony to the 'porous' nature of the archive and its implication in projects of identity formation.147

Yet Spohr's role in the making of the Bleek Collection deserves to feature more prominently than a scattering of mentions in the catalogue. Without his dogged determination and enthusiastic identification with Wilhelm Bleek, as well as his ability to speak fluent German, we would know but a fraction of what we now do about the lives of not only Wilhelm Bleek but also of Jemima and Lucy Lloyd, whose dramatic family history unfolds in the courtship letters which Spohr traced to KFM Scott. Without his work all this information would have remained buried in family collections and overseas libraries. Furthermore, Spohr's knowledge of German and dedicated years of translation, along with the graphologist Mrs Gal, brought to a wider audience the revealing diary of Bleek's travels in Natal in 1855-6, one which suggests a far greater degree of continuity between his first ethnographic project amongst the Zulu and the linguistic and ethnographic project for which he is best known: his /Xam researches of 1870 to 1875. Even the two column format of recording African language text and its translation, Spohr's work on the diaries revealed, was pioneered in Zululand.

Yet thoughout his years of working on Bleek's biography, Spohr remained surprisingly incurious regarding the notebook record for which Bleek and Lucy Lloyd (whom Spohr showed previous little interest in) are today justly celebrated. In fact the notebooks appear to have got lost during the time that Spohr worked on the Bleek papers in Jagger library, most likely in one of the innumerable tin trunks or other storage facilities then used by UCT's fledgling manuscripts department. The story of their 'rediscovery' in the early 1970s is now the stuff of founding mythology.148

What the story of Spohr's life illustrates, then, is the extent to which the personal and the particular may be imbricated in the process of archive making.

In telling the story of Otto Spohr, I have explored how the personal drive and motivation of one particular individual had an irrevocable influence on what is now a readily available body of knowledge contained within a scientifically structured system of access. This detailed description of a period of activity related to the making of the Bleek Collection provides material evidence of archive making as encompassing processes which are at once formal, ordered and objective, as much as they are spontaneous, creative and even contingent upon individual experience and identity. This phase in the making of the Bleek Collection supports theorists like Ann Stoler's arguments for the archive as process rather than place, as site of knowledge production rather than one of knowledge retrieval.149

1 This article revisits and extends research conducted for my M Phil minor dissertation 'From Tin Trunk to World-Wide Memory; The making of the Bleek collection' (University of Cape Town, 2006). It has been supported by a grant made in terms of the National Research Foundation's Project on Indigenous Archaeologies in South Africa, as well as additional funding from the University of Cape Town's Research Scholarship Fund, the KW Johnstone Scholarship Fund, and the Harry Oppenheimer Institute. Sincere thanks to Andrew Bank for his patient re-reading of the many drafts of this article. I must also acknowledge the friendship and support of Professor Brenda Cooper and Dr Nick Shepherd of the Centre for African Studies, UCT, as well as all the staff at Manuscripts and Archives, especially Isaac Ntambankulu, Lesley Hart, Janine Dunlop and Yasmin Mohamed. The images in this article are reproduced with the kind permission of the Manuscripts and Archives division of UCT Libraries.

2 The name given to the collection of notebooks recorded by Bleek and Lloyd, and associated materials, has been the subject of debate and contestation for a number of years. UCT's curators Leonie Twentyman Jones and Etaine Eberhard chose the name The Bleek Collection' when they catalogued the collection early in the 1990s (The Bleek Collection, A list (Cape Town: University of Cape Town Libraries, 1992)). The name of Bleek's co-researcher, Lucy Lloyd, has been added in some contexts, and the collection has been referred to as the 'Bleek and Lloyd Collection', for instance, in the title of Janette Deacon and Thomas A Dowson's edited publication Voices from the Past: /Xam Bushmen and the Bleek and Lloyd Collection (Johannesburg: Witwatersrand University Press, 1996). However, leading the trend to pay due recognition to Lucy Lloyd's contribution to the research project has been Professor Pippa Skotnes who has sought to reverse a situation in which she perceives Lloyd to have been 'ignored or cast into the role of sister-in-law assistant' in relation to the research project (Miscast: 21). To this end, Skotnes in 1996 dedicated her installation exhibition Miscast: Negotiating Khoisan History and Material Culture, and its companion publication Miscast: Negotiating the Presence of the Bushmen (Cape Town: University of Cape Town Press, 1996), to the memory of Lucy Lloyd. Furthermore, Skotnes has set up the UCT-based research centre, the 'Lucy Lloyd Archive, Research and Exhibition Centre' (Llarec) to pay tribute to Lloyd's great contribution to the notebooks and to recognise her achievements as a scholar in her own right.

3 ASC Hooper to Charlotte Spohr, 13 October 1980, BC 687, 'Correspondence File', OH Spohr Papers.

4 There are 13 boxes of uncatalogued papers in UCT's BC 687 OH Spohr collection. Box 1 of this collection is missing, and has been since I first encountered the collection in mid-2004.

5 For a fuller discussion on the making of the Bleek collection, see J Weintroub, From Tin Trunk to World-Wide Memory; The making of the Bleek collection', especially Chapters 2 and 3.

6 Stephen Foster and Roslyn Russel, with Jan Lyall, Memory of the World, General Guidelines to Safeguard Documentary Heritage, UNESCO: General Information Programme and UNISIST, 1995: 5; for a register of sites of world memory, see http://www.unesco.org/webworld/mdm/register/index.html

7 Spohr, WHI Bleek: vii; see also Etaine Eberhard, 'Wilhelm Bleek and the Founding of Bushman Research' in Janette Deacon and Thomas A Dowson, eds., Voices from the Past: /Xam Bushmen and the Bleek and Lloyd Collection (Johannesburg: Witwatersrand University Press, 1996), 49.

8 This early fragmentation of material is now being reversed as UCT's Rare Books Librarian Tanya Barben is working on a reconstruction of Wilhelm Bleek's library (personal communication - Tanya Barben, June 2005).

9 Editorial, The Jaggerite, no 21, July 1963, BC 687, Box 12. Also personal communication, Etaine Eberhard, April 19 and May 6, 2005.

10 OH Spohr, 'Some German Contributions to the Libraiy Movement in the Cape 1761-1862', undated typescript, Box 8.

11 Personal communication, Etaine Eberhardt, April 19 and May 6, 2005.

12 BC 151 - Bleek Collection Information re Provenance, archivists' files, Manuscripts and Archives, UCT.

13 E Eberhard and L Twentyman Jones, The Bleek Collection, A List.

14 The conference, 'Bleek and Lloyd: 1870-1991', organised by Janette Deacon, John Parkington, Thomas Dowson and David Lewis-Williams, was held in Cape Town from September 9-11. See J Deacon and TA Dowson, eds., Voices from the Past - /Xam Bushmen and the Bleek and Lloyd Collection, 4 for reference to the catalogue of materials compiled by Eberhard and Twentyman Jones.

15 Etaine Eberhard, 'Wilhelm Bleek and the Founding of Bushman Research', 49.

16 See, for example, J. Deacon, 'A Tale of Two Families: Wilhelm Bleek, Lucy Lloyd and the /Xam San of the Northern Cape' in Skotnes, ed., Miscast, 94, 96; M.Szalay, 'Dia!kwain, /Han≠kass'o, !Nanni, Tamme, /Uma and Da, Wilhelm Bleek and Lucy Lloyd: Biographical Remarks and Notes on the Pictures and their Origin' in Szalay, ed., Der Mond als Schuh/ The Moon as Shoe (Zurich: Scheidegger and Spiess), 28.

17 Paul Michael Meyer, Otto Hartung Spohr - a bibliography of his writings (Cape Town: University of Cape Town, 1979): Introduction.

18 Spohr, Otto H. 21 March 1968. Typescript, BC 687, Box 7.

19 Spohr, Otto H. 21 March 1968. Typescript, BC 687, Box 7.

20 Spohr, Otto H. 21 March 1968. Typescript, BC 687, Box 7; also Meyer, Otto Hartung Spohr: Introduction.

21 Meyer, Otto Hartung Spohr, Introduction.

22 Meyer, Otto Hartung Spohr, Preface and Introduction.

23 Meyer, Introduction.

24 Meyer, Introduction.

25 Meyer, Introduction.

26 Meyer, Preface.

27 Meyer, Otto Hartung Spohr.

28 Meyer: Preface.

29 Meyer: Preface.

30 Meyer: Preface.

31 Meyer: Preface.

32 'Spohr, author and bibliographer, dies', Cape Times, 13 October 1980. Cutting in 'Correspondence file', BC 687, OH Spohr Papers.

33 Personal communication, Etaine Eberhard, April 19 and May 6, 2005.

34 OH Spohr to JD Pearson, 7 August 1967, BC 687, Box 6.

35 Spohr, Otto H. 21 March 1968. Typescript, BC 687, Box 7.

36 'Spohr, author and bibliographer, dies', Cape Times, 13 October 1980. Cutting in 'Correspondence file', BC 687, OH Spohr Papers.

37 Meyer: Preface.

38 'Balkan Expert', heading on cutting from undated, unidentified newspaper in brown paper file marked 'Press Cuttings', BC 687, Box 8.

39 'Hungary As Part of Greater Germany', cutting from Cape Times Saturday 23 April 1938. Brown paper file marked 'Press Cuttings', BC 687, Box 8.

40 Spohr, Otto H. 21 March 1968. Typescript, BC 687, Box 7.

41 Undated curriculum vitae prepared by Spohr to accompany his application for the post of sub-librarian of the Medical School, Makerere College, Kampala, BC 687, Box 6.

42 'Spohr, author and bibliographer, dies', Cape Times, 13 October 1980. Cutting in 'Correspondence file', BC 687, OH Spohr Papers.

43 Meyer: Introduction.

44 Spohr, Otto H. 21 March 1968. Typescript, BC 687, Box 7.

45 Spohr, Otto H. 21 March 1968. Typescript, BC 687, Box 7.

46 He wrote articles on this topic in 1961 and 1962. With a flourish, he records '12 years of progress, 1946 to 1961' and praises '[e]nthusiastic librarians with progressive ideas', as well as the 'pioneering spirit of the new African universities [which] has done a great deal to promote document-reproduction techniques.' 'Document reproduction services in libraries in Africa South of the Sahara' (Spohr, 1962, 131). See BC 687. O H Spohr papers. Box 3, journal articles in light green file, Manuscripts and Archives, UCT. I include this information to create a sense of the enthusiasm with which Spohr embraced his task, and to give a sense of how he uses the term 'pioneering'.

47 American Library Association Bulletin, June 1953: 241, BC 687, Box 9.

48 Otto H. Spohr, 'A South African Librarian Abroad: Some observations on reproduction methods in European and American libraries', undated typescript, BC 687, Box 9.

49 American Library Association Bulletin, June 1953: 241, BC 687, Box 9.

50 American Library Association Bulletin, June 1953: 241-42, BC 687, Box 9.

51 Amerian Library Association Bulletin, June 1953: 241. BC 687, Box 9.

52 Amerian Library Association Bulletin, June 1953: 243, BC 687, Box 9.

53 Otto H. Spohr, 'Documentation Socialised? Some observations on present day Documentation and Bibliography in Yugoslavia', undated typescript, BC 687, Box 9.

54 American Library Association Bulletin, June 1953: 242, BC 687, Box 9

55 American Library Association Bulletin, June 1953: 243, BC 687, Box 9.

56 American Library Association Bulletin, June 1953: 243, BC 687, Box 9.

57 OH Spohr to Fiona Chisholm, 10 July 1980, Box 7.

58 BC 687, Box 9.

59 OH Spohr to Fiona Chisholm, 10 July 1980, Box 7.

60 OH Spohr to Fiona Chisholm, 10 July 1980, Box 7.

61 OH Spohr, The Natal Diaries of Dr W HI Bleek (Cape Town: AA Balkema, 1955), ix.

62 OH Spohr to Fiona Chisholm, 10 July 1980, Box 7.

63 BC 687, Box 6.

64 OH Spohr to D Varley, 28 July 1965, Box 6.

65 OH Spohr to D Varley, 28 February 1964, Box 6.

66 OH Spohr to D Varley, 5 December 1966, Box 6.

67 OH Spohr to D Varley, 2 August 1979, Box 4.

68 BC 687.

69 OH Spohr to HM Raggett, 26 June 1980, Box 7; on the motor vehicle accident and alcohol abuse, personal communication, Etaine Eberhard.

70 OH Spohr to HM Raggett, 26 June 1980, Box 7; with copy to Spohr's wife, addressed as 'Mex', who was at the time in Groote Schuur Hospital recovering from surgery for cancer. BC 687, Box 7.

71 OH Spohr to HM Raggett, 26 June 1980, BC 687, Box 7.

72 Spohr to Varley, 31 May 1962, BC 687, Box 6.

73 Dorothea Bleek's contributions to UCT were made during the 1930s, and in 1947, the year before she died (See OH Spohr, WHI Bleek: Introduction).

74 In UCT's reports on research and publications for 1953-55, Spohr is listed as being busy with 'research in progress' on German librarians at the Cape.

75 For the establishment of the SA Public Library and its founding collections, see C Pama, The South African Library, Its history, collections and librarians (Cape Town: A A Balkema, 1968).

76 Issue no 3 of 1962. Copies of both magazines in BC 687, Box 12.

77 BC 687, OH Spohr papers, Box 3, cuttings in light green file. Manuscripts and Archives, UCT.

78 Spohr to Varley, 28 February 1964, Box 6, BC 687.

79 Otto H Spohr, 'Bleek's Het Volksblad leaders', Quarterly Bulletin of the SA Library, vol. 17(4), 1963, 116-126.

80 O.H. Spohr, 'The First Special Librarian in South Africa: W.H.I. Bleek at the S.A. Libraiy' in C Pama, ed., The South African Library: Its history, collections and librarians 1818-1968 (Cape Town: A A Balkema, 1968).

81 Otto H Spohr, No date. Librarians at Work - And at Leisure: Searching for Data on Dr W HI Bleek, Typescript (initialled O H S), a copy of Spohr's contribution to the staff newsletter Jaggerite, pink archivists working file, Manuscripts and Archives, UCT.

82 BC 687, Box 6. 'Introduction, acknowledgements and arrangement of material', typescript, file labelled 'More WHI Bleek My copy'; OH Spohr, The Natal Diaries of Dr W.HI. Bleek, Cape Town: AA Balkema, 1965: viii.

83 BC 687, Box 6. 'Introduction, acknowledgements and arrangement of material', typescript, file labelled 'More WHI Bleek My copy'.

84 'Introduction, acknowledgements and arrangement of material', undated typescript, Box 6.

85 Undated, untitled typescript of captions, Box 7.

86 OH Spohr to D Varley, 28 February 1964, BC 687, Box 6.

87 Spohr to Varley, 31 May 1962, BC 687, Box 6.

88 OH Spohr, Wilhelm Heinrich Immanuel Bleek - a bio-bibliographical sketch (Cape Town: University of Cape Town Libraries, 1962).

89 Otto H Spohr, No date. Librarians at Work - And at Leisure: Searching for Data on Dr W HI Bleek, Typescript (initialled O H S), a copy of Spohr's contribution to the staff newsletter Jaggerite, pink archivists working file, Manuscripts and Archives, UCT.

90 Otto H Spohr, No date. Librarians at Work - And at Leisure: Searching for Data on Dr W HI Bleek, Typescript (initialled O H S), a copy of Spohr's contribution to the staff newsletter Jaggerite, pink archivists working file, Manuscripts and Archives, UCT. These finds would later form the core of Spohr's book on Bleek, The Natal Diaries of Dr WH.I. Bleek (Cape Town: AA Balkema, 1965). 'Librarians at Work' appeared in The Jaggerite, 21, July 1963.

91 Spohr, Librarians at Work'.

92 Spohr, Librarians at Work'.

93 Spohr, Librarians at Work'.

94 Twenty of the letters are in the collection at C10.1 to C10.18.

95 Spohr, Librarians at Work'.

96 Spohr, W HI Bleek, 14.

97 Spohr, W HI Bleek, 14.

98 Spohr, Librarians at Work'.

99 See A.Bank, Bushmen in a Victorian World: The Remarkable Story of the Bleek-Lloyd Collection of Bushman Folklore (Cape Town, 2006), 42-71.

100 Spohr, 'Librarians at Work'.

101 Spohr, 'Librarians at Work'. Copies of letters from Colenso to Bleek are at BC 151, C13.1-C13.161. There is no trace of the replies sent by Bleek to Colenso.

102 Spohr, 'Librarians at Work'.

103 OH Spohr to D Varley, 28 February 1964, Box 6.

104 These photographs are contained in an A5 envelope inscribed in Spohr's handwriting with a note suggesting that the collection was donated by Dipl. Pol. Wilhelm Bleek, Ph. D.

105 'Introduction, acknowledgements and arrangement of material', undated typescript, Box 6.

106 'Introduction, acknowledgements and arrangement of material', undated typescript, Box 6. See also Spohr's acknowledgements in Natal Diaries.

107 'Introduction, acknowledgements and arrangement of material', undated typescript, Box 6.

108 BC 151, Bleek, Anne, Clason Argentine - correspondence with O H Spohr re: Bleek family, archivists' working files, Manuscripts and Archives, UCT. No translations appear to be available.

109 Otto H Spohr, 'Bleek's Het Volksblad leaders', 116-126.

110 An edited English version of this publication, entitled 'Dr Bleek at Pau', appeared in the Quarterly Bulletin of the SA Library, vol. 20 (1), 1965, 5-10.

111 Spohr, The First Special Librarian', 62-63 (note17). Bleek's letters to his mother from Paris and Pau c1858 to 1860 are at BC 151, C1.32-C1.45, marked VERY FRAGILE.

112 BC 687, Box 2.

113 BC 687, Box 3.

114 Quarterly Bulletin of the South African Library, vol. 20 (2), 1965. See also BC 687, Box 12.

115 Spohr, O H, Zacharias Wagner: second commander of the Cape (Cape Town: Amsterdam: AA Balkema, 1967). An article by Spohr on Zacharias Wagner appeared in a 1966 edition of the Institut Fur Auslandsbeziehungen Stuttgart (Zeitschrift fur Kulturaustausch). Box 12.

116 BC 687, Box 13.

117 All journals in BC 687, Box 13.

118 Spohr, Natal Diaries, 5.

119 OH Spohr to DH Varley, 5 December 1966.

120 OH Spohr to JD Pearson, 7 August 1967, BC 687, Box 6.

121 OH Spohr to JD Pearson, 7 August 1967, BC 687, Box 6.

122 AP Matthews to OH Spohr, 10 September 1968, BC 687, Box 6.

123 OH Spohr to AP Matthews, 16 September 1968, BC 687, Box 6.

124 OH Spohr to Director, Library of the University of Heidelberg, 10 July 1980, BC 687, Box 7.

125 OH Spohr to HC Willis, 31 July 1967.

126 OH Spohr to Director, Library of the University of Heidelberg, 10 July 1980, BC 687, Box 7.

127 PC du Plessis to OH Spohr, 11 November 1969, BC 687, Box 12.

128 BC 687, Box 8.

129 HSRC President to OH Spohr, 15 December 1970, BC 687, Box 7.

130 OH Spohr to Etaine Eberhard, 16 July 1980, Box 7.

131 BC 687, Box 6.

132 Copy of journal article in BC 687, Box 13.

133 BC 687, Box 13.

134 OH Spohr to JA Ledger, 7 June 1978, Box 5.

135 R Musiker to OH Spohr, 8 August 1978, Box 8.

136 OH Spohr to AA Balkema, 7 December 1978, Box 4.

137 OH Spohr to W Tyrrell-Glen, 17 July 1980, Box 7.

138 OH Spohr to BH Watts, 17 July 1980, Box 7.

139 OH Spohr to BH Watts, 17 July 1980, Box 7.

140 OH Spohr to HM Raggett, 26 June 1980, BC 687, Box 7.

141 OH Spohr to E Eberhard, 16 July 1980, BC 687, Box 7.

142 BH Watts to OH Spohr, 8 May 1979, BC 687, Box 4.

143 Spohr to W. Tyrrel-Glen, 17 July 1980, Box 7, BC 687. See also Spohr to Mini-family, 9 July 1980, Box 7.

144 BC 151, K1.1; K1.2; K1.3.

145 BC 151, C10.19.1-C10.19.26;

146 BC 151, Bleek Collection - Provenance file, archivists working files, Manuscripts and Archives, UCT.

147 Carolyn Hamilton, Verne Harris and Graeme Reid, 'Introduction' in Carolyn Hamilton et al, eds, Refiguring the Archive (Cape Town: David Philip, 2002), 9.

148 Roger L Hewitt, 'An Ethnographic Sketch of the /Xam' in Miklos Szalay, ed., The Moon as Shoe, 33-34. Compare this with the story of discovery in DW Lewis-Williams, 'Introduction', Stories That Float From Afar.

149 A L Stoler, 'Colonial Archives and the Arts of Governance: On the Content in the Form' in Carolyn Hamilton et al, eds, Refiguring the Archive (Cape Town: David Philip, 2002), 83-100.