Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Kronos

versão On-line ISSN 2309-9585

versão impressa ISSN 0259-0190

Kronos vol.32 no.1 Cape Town 2006

ARTICLES

Anthropology and Fieldwork Photography: Dorothea Bleek's Expedition to the Northern Cape and the Kalahari, July to December 1911

Andrew Bank

History Department, University of the Western Cape

This article examines a collection of 158 photographs, almost all of Bushmen subjects, taken on a fieldtrip to the Northern Cape and the Kalahari by Dorothea Bleek. They feature in a large album that is housed today in the Bleek-Lloyd Collection in the Archives and Manuscripts Department of the University of Cape Town Library.1 The album was donated to the Library by Dorothea Bleek, probably some eight months before she died.2 It contains a further 154 photographs that she took on subsequent fieldtrips - to Kakia in the Bechuanaland Protectorate (1913), Lake Chrissie in the Eastern Transvaal (1916), Sandfontein in the South West African Protectorate (1920-21) and Angola (1925). A second, much smaller album contains 24 photographs taken on a fieldtrip to Bechuanaland in December of 1919.3Of the 158 photographs in the album that date to 1911, 37 were taken in Prieska Location, 35 on farms in the Prieska District, 16 on farms in Gordonia along the Molopo River north of Upington, 60 at Kyky above Twee Rivieren on the Lower Nossop River, and 10 at a farm called Mount Temple in the Langeberg east of Upington. Those taken in Prieska Location and on the farms in the Prieska District are well known, though have yet to be subjected to close critical scrutiny. Those taken further north have never been reproduced, let alone critically analysed. The obvious starting point, then, is why some of these photographs are so familiar and others not at all. We must start with Dorothea Bleek herself and how she later chose to package her expedition portfolio.

Frames familiar and familial

Dorothea Bleek is said to have been offered an Honorary Doctorate by the University of the Witwatersrand in 1936. She was then 63, and in the previous decade had published through Cambridge University Press two well respected works of scholarship - a much praised ethnography on the Naron of the central Kalahari (1928) and A Comparative Vocabulary of Bushman Languages (1929) - these in addition to her popular edition of /Xam folktales entitled The Mantis and his Friends (1923). She also had introduced and provided annotated descriptions on the basis of visits to 60 of George Stow's rock art sites in G.W.Stow and D.F.Bleek's, Rock Paintings in South Africa, which was published in London in 1930. In addition, she had published an important article on /Xam folklore and another on /Xam grammar in prestigious international journals. She had earlier published an article on kinship terms in different Bushman languages in the journal Bantu Studies.4More immediately, the University's offer came on the back of her nine-part series published in their journal, Bantu Studies, on the 'Customs and Beliefs of the /Xam Bushmen' (1931-36) and drawn from the notebooks recorded by her father and aunt. These have recently been republished.5 Despite these very substantial and enduring achievements, she is alleged to have declined the University's offer with the words 'There can only be one Dr. Bleek.' Here she was referring to her father Wilhelm. This story is all the more plausible in the light of her friend Margaret Shaw's memory of her as 'a gently-spoken, indefatigable person', who 'worked without showmanship or personal publicity and for no other reward than the interest and satisfaction of doing something that had to be done and of honouring her father's memory.'6

It was in the light of her life's mission that I interpret the way in which Dorothea Bleek chose to package photographs from her 1911 field trip for the readers of Bantu Studies in the year in which she declined the Honorary Doctorate. She selected just 24 of the 158 photographs taken on her expedition.7 The images were drawn exclusively from the early part of her fieldtrip: her work in Prieska Location and on farms in the Prieska District. All of the photographs were posed portraits: eighteen of individuals, four of two individuals, one showing three siblings, and a group portrait.8 Four of the individuals were shown in front- and side-profile form. Her commentary in relation to the photographs is frustratingly sparse. She provided rather random blocks of text from her notebook records in relation to some of the individuals who were photographed, but presented no general information. We are told nothing about exactly why she took the photographs or what kind of camera she was using. When read together the general point was clear: 'All these Bushmen at Eyerdoppan spoke the language fluently, but knew no folklore'; 'Roman Titus did not know his own parentage'; 'Guiman ... knew no folklore, as his people had been driven about all his young days.'9 In other words, she presented the photographs as visual evidence of a fragmented community whose traditions and culture had been irrevocably lost. Following on from her 'Customs and Beliefs' series, they were confirmation of the magnitude of her father and aunt's achievement. These photographs suggested that the cultural riches of which you have just read were collected just in time - before /Xam Bushmen society was reduced to this scattered state.

A second strand running through the captions is an emphasis on physical anthropology, a discipline which had risen to prominence in South African science in the intervening years. Her notes indicate that she had measured the photographic subjects - in two cases she was forced to measure aged subjects lying down. She also assured readers that (with one 'mixed' exception) these were all 'pure' or 'real' Bushmen.10

A selection of the photographs that Dorothea Bleek took in 1911 have been recirculated in academic studies in recent years. This comes on the back of a flourish of scholarly interest in the researches of Wilhelm Bleek and Lucy Lloyd, and in the lives of their /Xam informants. The context, therefore, remains that of the family story. Following her own lead, though in much more explicit terms, the photographs that she took in the Prieska Location and District have been packaged to present visual evidence of the impoverished and fragmented state of a society that had once possessed such a rich and treasured oral tradition. In Miscast, where these images are used most fully, a number of the original photographs have been skilfully cropped and reframed to enhance the sense of fragmentation.11 The textual framing drives the message home: most of the photographs feature in a chapter entitled "Fated to Perish": The Destruction of the Cape San'. The only caption echoes Dorothea Bleek's much later claim that 'the folklore was forgotten'12 (although her notebook record suggests that this was an exaggeration). The remaining portraits in the Miscast chapter - two of individuals, and one of a mother and child - appear to have been selected for the definite sense of sadness and strain on the faces of those who are photographed.13

Even where a more active selection of photographs features - as in Jeremy Hollmann's recent book - the caption ties the photographs to the story of loss: 'Many years after she had visited Prieska . Dorothea Bleek wrote that although the language and folklore seemed to be lost, "Even at Prieska the very old started the dance of former days after a feast of meat" (Bleek 1924: ix). These photographs may have been taken at the dance she mentions.'14

The other point of emphasis in Dorothea Bleek's notes on the photographs she had reproduced in Bantu Studies - physical anthropology - has also been taken up in recent years. Four of the photographs she took at Prieska Location - including the group portrait and two individual portraits - were selected by the South African Museum curators Patricia Davison and Gerald Klinghardt to feature alongside the Museum's controversial Bushman Diorama in its final years on display. Their captions explained that several of the individuals who appeared as life-casts in the Diorama had earlier been photographed by Dorothea Bleek in 1911. Davison's important research on the history of the casting project uncovered the bit-part played by Bleek in selecting appropriate individuals from Prieska Location to be cast on site by the South African Museum's modeller, James Drury.15

In short, there has been clear continuity between the way in which Dorothea Bleek packaged her collection of the photographs for the readers of Bantu Studies and the way in which these photographs have been repackaged in more recent times, whether in published works or museum displays. This article seeks not only to examine a wider selection of photographs from her 1911 fieldtrip, but also to analyse very much more closely her motives in relation to each of the groups she was photographing. I argue that her Prieska Location series was motivated more by a desire to show community coherence than to show fragmentation. Furthermore, her hitherto unpublished Kalahari photographs were meant to record the culture of a relatively unseen 'tribe', and her photographs taken on farms, including those from the Langeberg, sought to depict the poverty of 'scattered farm hands'. I also explore how certain of her subjects resisted her attempts to photograph them and, in particular, her attempts to get them to pose naked before the camera. Before telling the story of her expedition in these terms, however, I would like to think about how we might locate her collection in somewhat broader and more comparative terms - in a way that removes them once and for all out from the long shadow cast by Wilhelm Bleek.

Widening the frame: anthropological and expeditionary photography

To begin with I think of these photographs in relation to Dorothea Bleek's contribution as 'a renowned scholar and ethnographer in her own right'.16 She was one of a cast of pioneering women researchers in the social sciences in South Africa.17 This involves thinking about the photographs and her 1911 expedition in relation to the development of ethnographic and anthropological research in the 1910s and 1920s - that is, in a way that looks forward to the scientific research of the early twentieth century rather than backward to her father and aunt's work of the 1870s. As we shall see, her portfolio represented very much more than the last record of a dying culture.

Locating Dorothea Bleek in this more collective way does raise questions about her disciplinary identity. She was, of course, trained as a linguist not as an anthropologist. She had taken diploma rather than university courses at the London School of Oriental and African Studies, and the Berlin School of Oriental Studies in the 1890s. She would neither teach Social Anthropology at a South African university nor was she deeply read in the discipline when she did her fieldwork, as was Winifred Hoernlé, for example, who had conducted research in Namaqualand in 1912 fresh from her studies in Cambridge and at the Sorbonne. I would, nevertheless, argue that Dorothea Bleek's 1911 research was 'anthropological' in a looser sense, on the grounds that she was interested in the issues that concerned anthropologists of the time and subsequently. Her fieldnotes and her photographs show that she was interested in very much more than language. Her records include extensive details about family relations and histories, an interest (albeit somewhat frustrated) in folktale and belief, in material culture and artifacts and certainly a sustained and systematic attempt to record rituals in the form of song and dance. It may be that Dorothea Bleek had no formal appointment as an anthropologist at a museum or university when she embarked on her expedition in 1911 (it was only twelve years later that she was formally appointed as an Honorary Reader in Bushman Languages at the University of Cape Town). Nevertheless, much of the information that she was collecting fell within the ambit of what contemporaries (and now modern researchers) would define as cultural or social anthropology, as this analysis of her photographs will confirm. This is apart from any of the physical anthropological data she gathered for the South African Museum.

In recognizing her photographs as 'anthropological', a whole range of new questions opens up for us. How did her photographs differ from other collections of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, especially those that were recording vanishing races or cultures? One thinks here of the photographs of EH Man on the Andaman Islands from the 1870s to the 1900s, Diamond Jenness's work in Papua New Guinea in 1911-12, and Joseph Dixon's photographs of Native Americans in the early decades of the twentieth century.18 How did her collection relate to the broad transition in anthropological photography from the public to the private that Elizabeth Edwards charts?

Edwards argues that the anthropological photographs of the middle and late nineteenth century were, typically, highly public documents that were energetically circulated within an emerging, international anthropological community. These photographs, most typically the portraits of 'racial types', were conceived very much in comparative terms, and the professional circuits through which they travelled meant that they were almost always archived in relation to photographs from other parts of the world. In the early decades of the twentieth century, however, photography became less central to the production of anthropological knowledge. Social or cultural anthropologists were now interested in the deeper workings of single societies rather than surface comparisons within an evolutionary framework. As participant observation became the defining disciplinary method, so photographs were relegated to the status of 'by-product rather than process' in anthropological research. As such they increasingly became private documents, kept in the homes or offices of researchers along with fieldnotes, only to be bequeathed to research institutions in later years, usually when the anthropologist had died.19

This decline in the status of photography is one of the reasons why the analysis of early to mid-twentieth-century fieldwork photography remains such a 'surprising silence' in visual anthropology. This certainly was not because fewer photographs were being taken in the field in the 1920s and 1930s, as Wolpert notes. All the evidence suggests otherwise, with cameras becoming more portable and the reproduction of images in printed form becoming ever less expensive. The methodological focus in the new age of participant observation was, however, very much on 'the invisible': on kinship, political rule, marriage systems or religious beliefs rather than on bodies or artefacts of material culture.20

Edwards' argument for a shift from the public to the private is particularly interesting in relation to the collection of photographs that Dorothea took in 1911. They straddled these two eras of anthropology and anthropological photography: they were both public and private, coming at the end of the era of officially archived comparative anthropology (of which her father's Breakwater Prison images were part) and at the beginning of the new era of privately kept photographs that related to specific fieldwork projects, like those of her contemporary women anthropologists. While certain of the photographs, notably those following the conventions of physical anthropology, were both commissioned and archived by the South African Museum and its director Louis Peringuey, many others (including those taken in the Kalahari) were primarily envisaged in the more private sense of a record of a particular fieldtrip which could be read alongside the fieldnotes which she recorded at the time. It is in this private sense that she later arranged them in an album together with those of her other fieldtrips. As I have mentioned, it was only just before she died that she presented the album and the fieldnotes to the University of Cape Town Library.

A second way of widening the frame is to think of the collection in relation to a longer and looser tradition of expeditionary photography in southern African, the 'safari tradition' described by Robert Gordon.21 What stands out when we locate Dorothea Bleek's photography in this lineage is her focused interest in human subjects. James Chapman, the acknowledged pioneer, had a zoology book in mind at the time of his travels (1861-2), and animals feature more prominently than people in his stereographs.22 The official photographer on the Palgrave Expedition (1876), F.Hodgson, was far more interested in botanical and landscape photography than he was in people.23 William Leonard Hunt, alias G.A.Farini, was associated with Kalahari Bushmen more as a showman after he had returned to Europe than as a leader of an expedition that produced a body of ethnographic photographs.24 I have been able to identify no expeditions showing a sustained and systematic interest in photographing Kalahari Bushmen in the decades that followed. Bryden journeyed to the Northern Kalahari in 1890, but took few ethnographic photographs. Alfred Duggan Cronin created a photographic record of Bushmen in 1904-5, but these were images taken in a Kimberley compound rather than in the field.25 The 60 photographs that Dorothea Bleek took at Kyky north of Tweerivieren might in fact, then, allow her to lay claim to be among the first photographers, if not the first, to take a systematic series of images of Kalahari Bushmen!

When we think of her photographs in relation to those of the 1925-6 Denver African Expedition so richly documented by Gordon, the contrast is striking. For while both Bleek and Paul Hoefler, the Denver Expedition photographer (incidentally also in his late thirties), were both interested in human subjects, the ways in which the Bushmen were photographed could hardly be more different. As Gordon demonstrates, Hoefler consciously excised any signs of marginalization and poverty, presenting the Kalahari Bushmen in the romantic mould that became such an established trope in twentieth-century Western mythology. Gordon shows that it was the Denver African Expedition of the 1920s rather than the better-known propagandizing of Laurens van der Post in the 1950s that established the stereotype of the Bushmen as pristine primitives in happy harmony with their environment. Another obvious difference, which any casual comparative perusal of the portfolios confirms, is the quality of the photographs. Dorothea was an amateur and Hoefler a highly experienced and skilled maker of images, enjoying we might add the technological benefits of another decade and a half of improvements in a rapidly changing field.26 The 1911 expedition was Dorothea's first proper training in the use of photographic equipment in the field.27

Finally, there were significant differences in choice of subject matter. Most of the categories into which Gordon classifies the Hoefler photographs28 simply do not apply to Dorothea's collection. Almost all of her photographs fall into the first two of his categories: '"Natives" (whether Male or Female)' and 'Activities'. In her case the 'Activities' were dances. She took few photographs of 'Scenery' and none of 'Animals'. In one photograph we see 'Settler Society' in the image of a farmer, and there are very occasional but completely inadvertent traces of 'Expedition Members', as we shall see. She might have chosen to show 'Technical Gadgetry', notably her phonogram and the reported amazement at it, but consciously opted not to do so. The reasons are not difficult to fathom. Unlike the members of the Denver Expedition, she felt that there was little to celebrate in modern technology and the progress of civilization. On the contrary, it was the negative impact of modernity that explained the unfortunate state of many of those she was photographing.

This highly focused interest in human subjects in Dorothea Bleek's photographs on this fieldtrip is also striking if we compare her collection with the photographs taken by other women anthropologists.29 The most closely related in their timing are the field photographs taken by Winifred Hoernlé in Namaqualand in 1912. As is well known, Hoernlé's field photographs were tragically destroyed along with her fieldnotes and gramophone recordings of Nama music when part of the University of the Witwatersrand Library burnt down. Her field diary, however, does give one a sense of her interests, which were strikingly eclectic. Her photographic subjects included her wagon and oxen, and the passing landscape, such as mountain views, rocks in a river, a cave, a waterhole, an aloe against a stone bank. Especially in view of her university training, there are far fewer photographs of people, informants or otherwise, than one might have imagined. She mentions two photographs of aged informants, one of an unnamed ethnographic subject of 'mixed' origins, and another of a subject of 'pure' racial origin. Most interesting is the photograph that she took of 'women making mats and grinding coffee'.30Images of economic activity are strikingly absent in Dorothea Bleek's collection, while those of cultural practices are largely confined to dance.

A final comparative expedition that warrants mention, especially given the comparable regional focus, is the Witwatersrand University's expedition to Tweerivieren. The photographs taken on this expedition still await full analysis, but the preliminary findings of Rassool and Hayes suggest a very strong and invasive emphasis on physical anthropology. Dorothea Bleek herself had interviews with the Kalahari Bushmen group of 1936 at the University's Frankenwald Research Institute and later at Rosebank in Cape Town when /auni and Kung groups were taken and exhibited around South Africa by Donald Bain.31

In short, we need to widen the frame. Dorothea Bleek's photographs taken in Prieska Location and the Prieska District (of which there are over 70) certainly do document a culture in decline. Some, at least, were designed to record physical anthropology, in keeping with the wishes of the South African Museum's director Louis Peringuey. Yet there is very much more to her photographic collection than this. She was also interested in signs of community and culture, and her photographs attempt to record this, as I argue below. As such, they need to be read in relation to a range of texts that she produced in the field: in particular her field-notes, which for a few weeks in the Kalahari were turned into a field diary, and her numerous letters to Peringuey while in the field, which we might also think of as 'fieldnotes' following James Clifford's fluid and flexible conception of the term.32 In addition, the captions that she provided on the back of each of the prints, perhaps quite some time later when she compiled her album, help to anchor them in relation to the story of the expedition. Finally, as we will see, she had a journalist as a travelling companion for the Prieska leg of her tour and the report that her co-traveller produced for the readers of the Cape Times in September of 1911 is far more vivid and detailed about their experiences than anything Dorothea herself recorded. Indeed, it was only upon reading this newspaper article by her fellow-traveller that I first began to question Dorothea Bleek's retrospective constructions of what she had encountered in the field.

Photographing community: /Xam Bushmen at Prieska Location, 28 July-11 August

Dorothea Bleek boarded the train from Cape Town, probably on 26 July. Along with her general luggage, including hats for protection against the harsh Northern Cape sun, she had in tow various items related to her work in the field. Her notebooks refer to the sundry 'curios' used to loosen the tongues of potential informants: 'Boer tobacco', cloth and brightly coloured beads. She also had a tape-measure for measuring the bodily proportions of her subjects, and the South African Museum's Edison-Bell phonogram for recording the language and songs of different Bushmen groups.33 We know she had a handheld camera, but can only speculate as to the model and type. My hunch is that it had been lent to her by the Museum, as the dearth of family photographs would seem to imply that she did not have a camera for private use at home. The Museum would presumably had access to the latest technology and have provided a relatively mobile instrument, perhaps a successor to the first folding Kodak model introduced on the market in 1897.34

As noted above, Dorothea Bleek had a companion for the first leg of her expedition, a young woman named Olga Racster. We may recall that Dorothea had travelled with Helen Tongue on her earlier rock art expeditions,35 and these journeys in the company of other women set a precedent for her later fieldwork expeditions. Racster went on tour in her capacity as a Cape Times journalist. She and Dorothea probably met in London when the rock art copies produced by Helen Tongue had been on display at the Anthropological Institute. Racster stayed nearby in Fleet Street at the time.36 Her musical background may also have encouraged Dorothea to take her along, given that the recording of Bushman songs was envisaged as a very important part of the fieldtrip. The copies in the African Studies Library at UCT of Racster's Chats on Violins, published in London in 1905, and her sequel volume, Chats on Violincellos, which appeared three years later, contain dozens of absolutely glowing reviews in the contemporary English press inserted into the volumes.

The two women journeyed to De Aar and then down the branch line to Prieska, arriving on 27 or 28 July. Dorothea had been to Prieska the previous year, primarily on a mission to test out some of the vocabulary in Specimens of Bushman Folklore as a favour to her aunt.37 They stayed at the Van Zijl's house on Church Square in the centre of this small Karoo town.

The 'native location' was situated on the slopes of a hill away from the town centre. Racster evocatively set the scene for her newspaper readers. This was a place where 'queer scraps ... perch in every sort of rickety madness. There are rush-huts and tin-huts and rag-huts. Huts with definite form, huts with no form at all; places like dog-kennels, and wonderful erections made out of the ubiquitous paraffin tin. It is an untrimmed growth, furnishing a study in contrasts.' Up in one corner, she continued, 'a bunch of over twenty Bushmen and their families' were 'living in low huts made of a frame of branches and covered with sacks and rags', along with many other 'natives' including Koranas, Griquas and 'an endless variety of Kafirs'.38 The location may have had as many as four or five hundred residents. Cape Colony Today recorded that the town had a 'coloured' population of 732, some 150 more than its 'white' population.39 A small minority would have been accommodated in the white part of town as live-in domestic workers or servants.

I imagine Dorothea Bleek introducing Olga Racster to the informants she had interviewed the previous year: Janicke Achterdam, Klaas Bosman and Rachel Streep. She recorded detailed genealogies of their family histories in her notebook. Here we learn that Janicke (or Hokan) lived with her husband, Jan, and two daughters, !auken (Lea) and !yau-!kauken (Lies). A third daughter, !orrika-!kwi, and her husband may also have stayed with them. Janicke also had four sons: !kau (Dawid), /kunn-kossi (Jainki), ʘsi (Klein Jan) and hu-o (Klaas), who stayed with their masters in the white part of town. Klaas Bosman (or Kobutu) also lived with his wife - her name was !yarri (Kaiki). They had three sons with them - !gari /a (Piet), Bakkis, Stuurman, as well as their daughter Katje, her three children, her husband Thomas Bammus and his brother.40 Rachel Streep was the only informant with some connection to the work done by Lucy Lloyd in earlier years. Rachel had spent a short time in Cape Town in 1884 along with her mother, Micki Streep (or /Ogen-an) who had been photographed for Lucy Lloyd. The image of her holding a digging-stick appeared in gold-embossed form on the cover of Specimens of Bushman Folklore, as well as in the form of a plate in the book itself. Rachel stayed with her husband Guiman.

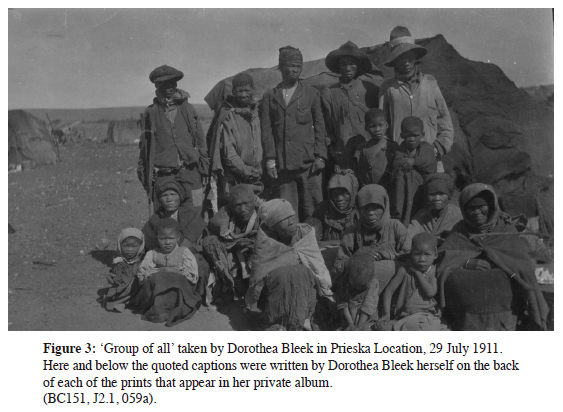

Dorothea began her photographic work the very next day. Her notebook entries for 29 July begin with /Xam words for various items - woodpipe, pipe stem, hat, skin kaross, goura (a musical instrument). She then recorded a list of photographic subjects:

1. Klaas Bosman, Guiman and self

2. Klaas Bosman & wife

3. Klaas Bosman & wife, 'Oud Katje'

4. Klaas Bosman & three sons, Piet, Barkis & Stuurman Bosman

5. T.Bammus & wife & three children (2 girls and a boy)

6. Kaiki with Lena & Jacomini

7. Klaas side face

8. Guiman side face

9. Group of all.

From this list we can glean some sense of what Bleek was trying to do, contrary to what she later conveyed to the readers of Bantu Studies. Only the last two items listed here featured in the 1936 selection taken in Prieska Location. As we know, the other images she selected were typically of individuals, often in side-profile form.

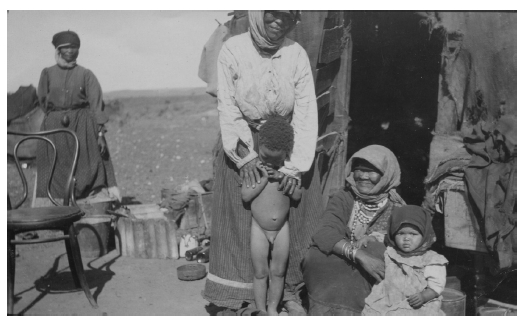

The list suggests that her immediate concern was to create a record of the families in this /Xam community whose genealogical histories she had been recording. Accordingly, most of the photographs (those numbered 2 to 6) were family portraits, showing either a husband and wife, or parents and children. There are another half a dozen family photographs in her album with captions like '/kham couple', /kham family', '/kham Bushman family', '/kham grandmother and granddaughter', and in most cases she adds the names of the individuals.

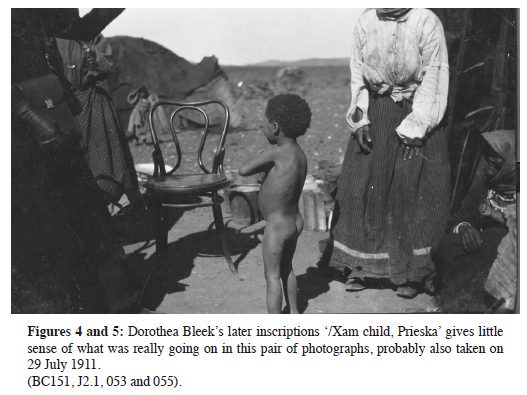

These two photographs were probably taken that afternoon, as the creeping shadows might suggest. They show a family scene, albeit imperfectly captured, with the heads of three of the figures cut off in the photograph reproduced above. This one was evidently taken first. The /Xam child in the centre is almost certainly the granddaughter of Janicke, the women with beads around her neck and a cloth over her head on the right-hand fringe of the photograph. The small hand of another child, a girl in a dress, is just visible beneath her beads. The woman further back is probably Lea or Lies (Janicke's daughter), and the mother of the children. In the background centre we are given a glimpse of household items, notably the wooden chair, but also a bucket and a piece of corrugated iron. Most interesting, though, is the figure dressed in black making a chance appearance on the left-hand side of the frame. Here I am reminded of Elizabeth Edwards' reflections about the links between photography and 'theatricality':

First, is the intensity of presentational form - the fragment of experience, reality, happening (whatever you want to call it) contained through framing, and second, the heightened sense of sign worlds that results from that intensity ... As singular events are presented as discrete displays, they are forced into visibility, focusing attention, giving separate prominence to the unnoticed and, more important, creating energy at the edge ...41

I read this energy in the outstretched arm of a figure that can only be that of Olga Racster. Her hand gesture is attracting the attention of Janicke and Lea or Lies (whose face is not quite visible). Racster's black gloves, black leather bag and long black dress seem strangely out of place in this setting. The 'random inclusiveness' of the photograph thus allows us to reinterpret an image captioned '/Xam child, Prieska'42 as a scene of interaction between a /Xam family - the real subject of the photograph - and a gesturing white journalist in the act of researching their lives for a newspaper article. There is, incidentally, no surviving print of the photograph of 'Klaas Bosman, Guiman and self' (number 1 on Bleek's inventory).

The second of these photographs is clearly a staged image. Here Bleek has taken time to compose and frame. Racster is cut out, the little girl next to Janicke included, as is the head of Lea or Lies. There are numerous other instances on the expedition of Bleek improving on a photograph taken in the midst of movement, including that reproduced below where Olga Racster makes her only other appearance in the album in the background of a drum-and-dance routine.

We must, however, first mention Janicke's performances on 31 July. The notebook gives the words of these songs, as far as Bleek was able to capture them. They do not make for very convincing reading. Bleek later wrote that 'I have always felt very helpless face to face with native music and songs.'43 Olga Racster's description of one of the songs, 'horses dragging the cart' gives a vivid sense of Janicke's performance.

She was carefully dressed for her call, her face entirely covered with some rich brown pigment, her fingers adorned with rings that looked extremely fetching on her small brown hands. She had bangles on her arms; beads round her neck, her buchu powder box hung at her side, and her clothes were neatly patched.

Up till then she had said, like the others, she could not sing. She was 'too cold' and 'too hungry' and her heart was too sore for the old days. Boer tobacco, however, had a salutary effect, and in the end she squatted with her back against the wall, humming on interchangeable vowels. She explained that her song was the song of one riding on a horse, and to make the whole more expressive she tapped out the sounds of galloping hoofs upon her knees, while she turned her head from side to side, scanning the country. For simple imagery nothing could have been better done. Her voice began softly, then gradually increased in volume so as to bring the horse and the rider from the distance. Then again it faded away when he had passed.44

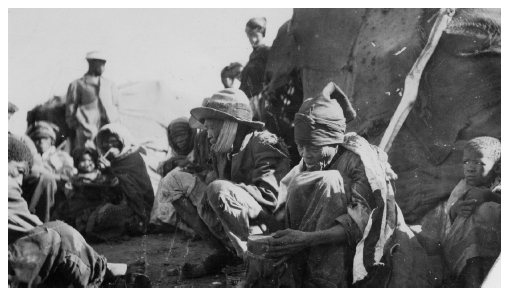

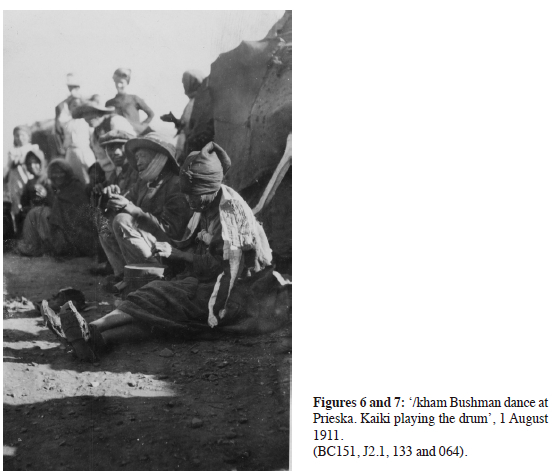

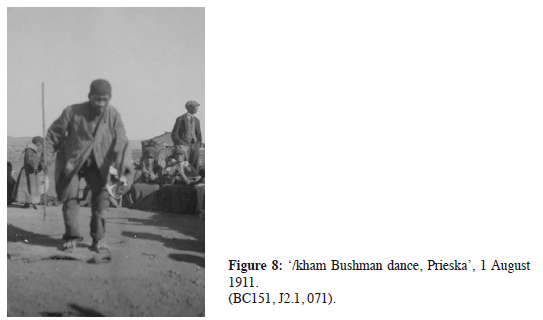

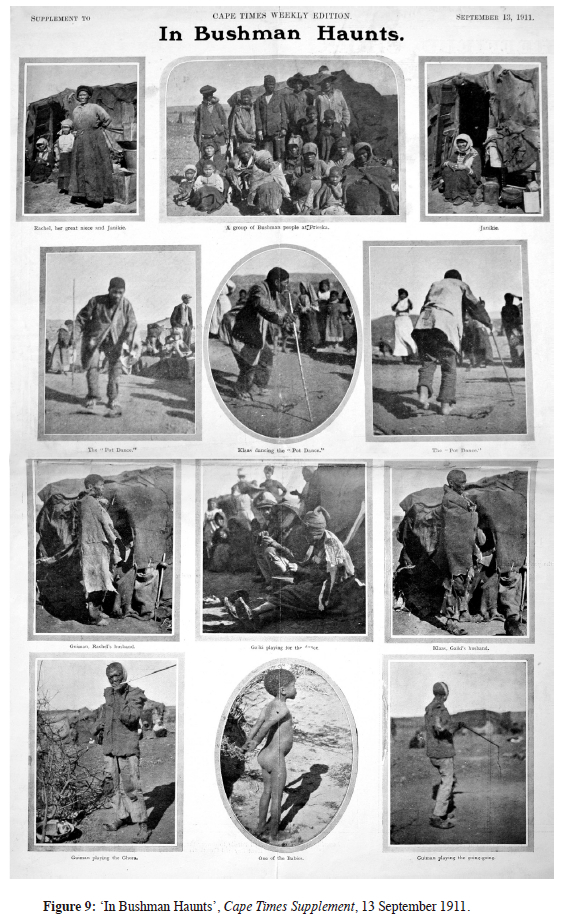

We can now return to the 'pot dance' ceremony which Bleek photographed on 1 August. In her notebook, Bleek recorded a series of words and sentences in /Xam which translated as 'the men dance, the women clap hands, play the !goura, dancing rattles tied onto instep, seeds of wild pumpkin.' Again Racster's article in the Cape Times gets us closer to the action:

When we arrived at the location on the particular afternoon, Old Guiman was sunning himself outside his hut, playing the ghora [goura]; others unpinned their front doors to see us ... Guiman had made the instrument himself, and presently he came into a ring of natives, who had been gathering round, with the quill pressed to his lips, making sounds much like those produced by a fiddle. Mostly he played a fundamental note, a fourth above and its octave below, and filled in the distance between with humming. The tone carried a long distance, but it was particularly sweet and attractive.45

Bleek took two photographs of Guiman playing his goura. The first showed him tuning the instrument, the second was of him playing in the way described above. This was just the curtain-raiser. As Guiman's performance drew to a close, a large audience gathered around him. A drum was brought out from one of the huts by Kaiki. She 'sniffed the air as she squatted down amongst the audience, placing the drum before her.'46 This is the moment captured in the first of the photographs above: Kaiki in front of her drum with Klaas on the left hand side of the frame and an assorted audience sitting around before the scene had been staged.

The second photograph has been much more carefully framed. It has more depth of field to provide more focused attention on Kaiki whose legs are now outstretched and her right hand in a blur as it comes down towards the drum. The figure in the far background, a woman with her hair in a bun, is none other than Olga Racster probably donning the same black dress that she had on a few days before. In the second photograph Racster and the rest of the audience have been arranged in a less haphazard way. This suggests that the event might not have been quite as spontaneous as Racster would have her newspaper readers believe. Her readers were likely to be more impressed, however, by an account of a free-flowing, centuries-old ritual than by one of a stage-managed re-enactment at a price of a 'duk' (headscarf) and Boer tobacco.

This is one of twelve photographs of Klaas's 'pot dance' which, as its name suggests, was associated with a feast. The photographs show him dancing on a goatskin that he had placed on the ground. Once again Olga Racster provided a vivid description:

The translation of the word 'dance' in Bushman means 'to tread', and literally this was the chief characteristic of Klaas's performance. He stood almost in one place on the goatskin, treading and shuffling each foot, each movement setting the pumpkin seeds rattling in the springboks' ears. As he danced the clappers round him brought their hands together with more force ... Time after time this was repeated until Kaiki began to weary of playing the drum ...47

Racster probably left for Cape Town the following morning. On 6 August Bleek wrote to Peringuey from Prieska: 'No doubt Miss Racster has seen you by now, & told you of our luck. I hope the photos taken will develop well; I will send you copies when I get them & have marked them properly with names etc.'48 A week or two later she would have had the photographs developed either in Kenhardt or Upington, and then posted copies to Peringuey and Racster. The Cape Times reproduced this selection in a large spread that featured alongside Racster's article 'Bushman Hunting: A Trip to Bushman Haunts' on 13 September. It admirably captures the sense of liveliness and activity that her written report conveys and stands in marked contrast with the static impression created by the posed portraits in say Bantu Studies or even Miscast.

Bleek spent a few more days collecting gramophone recordings in Prieska Location. The purple cylindrical boxes in which she stored the records remained in storage in the South African Museum until recently. The inscriptions on white labels on the lids of these boxes reveal what the records contained: 'Janiki, parts of body', 'Janicki, her relations with their names' and a 'song to fiddle accompaniment', 'Klaas Bosman. Names of races, members of family and animals', 'Kaiki, sentences', 'Guiman. Song of longing for his children', 'Guiman describes how to get to places where his children are & journey to the Cape'. These wax cylinder recordings have recently been retrieved and converted into compact disc form, although the inability of the gramophone to record click sounds (as Bleek noted at the time) does compromise the quality of the reproductions. Dorothea reported to Peringuey that the gramophone was an object of fascination:

The gramophone is working nicely now. I have got records of several songs & some conversation. The reproduction is good or bad according to the clearness & loudness with which the speeches are made. Some do much better than others. The Bushmen are delighted at the correct reproduction of their language by the machine, & would go on talking into it all day if encouraged to do so.49

It is interesting to note that she made no attempt to exploit the photographic potential of the encounters with modern technology, as so many other ethnographers did. The most famous images of native encounters with modern technology is probably that of Emil Torday's clockwork elephant performing its manoeuvres on a table in front of a large crowd of Africans with Torday himself standing alongside.50 One also thinks here of the Native Commissioner Cocky Hahn's photograph of the Ovambo encounter with a gramophone taken in the 1930s.51

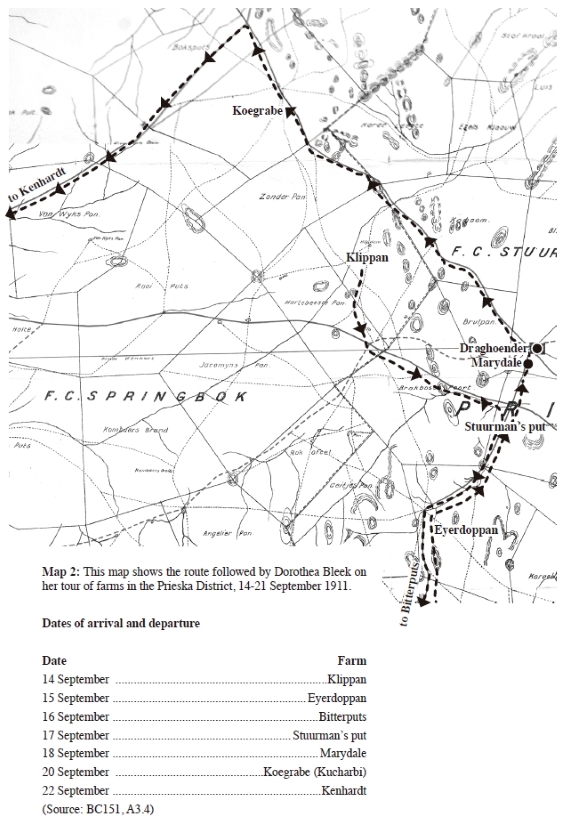

Resistance to being photographed: Prieska District, 14-21 September

Dorothea Bleek left Prieska on 12 or 13 August. Now she was travelling by wagon. She makes no mention of travelling companions, although it is possible that she took an interpreter or guide. She would certainly have needed to employ a wagon-driver. Although she took no photographs of her wagon on this expedition, images from her fieldtrip two years later suggest that it was quite sizeable. The five Tswana men seated in the foreground there appear rather small in relation to the wagon behind them.52 She had spent some weeks preparing for this second leg of her expedition: perhaps gathering supplies, more probably enquiring where the Bushman farm labourers were to be found. Her notebook indicates that she had begun preliminary inquiries at Prieska Location: a few of the farm labourers she photographed or interviewed were related to members of the Prieska Location community.

Her fieldnotes indicate that she was staying on the farm Klippan north-east of Draghoender on 14 September. The next day she trekked down to Eyerdoppan. She then went further south to Bitterputs for a night before returning to Stuurman's Put and then Marydale. She reported to Peringuey from the Marydale Hotel:

I have been touring round Prieska District, following up all the Bushmen I hear of, but they are scarce. At Bitterputs, the home of my father's first Bushman, there are a row of Bushman graves. When the father of the present owner's wife settled there in 1874, he found 42 Bushmen there, who scattered mostly, but some remained in their service & died there.53

The old maps reveal that Dorothea Bleek got the wrong Bitterputs. The farm that she visited of that name was south-west of Eyerdoppan, as indicated on the map above. The Bitterputs of her 'father's first Bushman', //Kabbo, was some forty or fifty kilometers to the north-east.54 From Marydale she trekked to Koegrabe (which she recorded as Kucharbi), arriving there on 20 September before heading on to Kenhardt.

It was a week of intensive photographic activity. Most of her Bantu Studies photographs were taken on these farms. Since most of them had only had a few resident /Xam families, the photographs are all of individuals, couples or small groups. Here Bleek began to make a more concerted effort to gather the physical anthropological data that Peringuey was after. Had he possibly written to encourage her in the interim? He expressed some disappointment with the Prieska Location photographs, probably because they contained too much information about culture and community, and too little information of a physical anthropological kind.

This may have been partly because of the reluctance of the /Xam community in Prieska to offer such information. Racster reported to her readers that when Bleek tried to photograph a /Xam girl, the girl's mother 'came striding towards us shouting, "They shan't have my child, they shan't have my child". Explanations did little to pacify this angry little person, for she was obsessed with the idea that we were drawing up some contract which would make the children our servants.' When the researchers, with seeming insensitivity, suggested that she too pose for the camera, 'she continued glowering and questioning: "Pictures! What did we want pictures for?"'55

Most of the resistance related to being photographed naked rather than to the camera itself. Verbal requests and, we may assume, a fair measure of bribery in the form of tobacco and cloth, were not enough to induce most of the /Xam farm labourers to undress. Dorothea reported to Peringuey on her work at Eyerdoppan: 'I have taken a good many photos, but Dutch propriety, of which the farm hands have acquired a good deal, makes it impossible to get them without clothes.' Stuurman's Puts was in fact the only place where Dorothea Bleek succeeded in persuading /Xam subjects - two women and a man - to undress before the camera,56 but this was only because of the intervention of the farmer's wife, Mrs Snyman. Bleek seems to have tried to rationalize away her sense of discomfort: 'It is the opinion of fellow natives, & of their Dutch masters the Bushmen are afraid of. They are not themselves very particular as to the amount they are covered.'57 She conceded though that 'individuals differ' and also speculated that 'our sex made them [the men] shy'. She predicted that the museum modeller, James Drury, would not have the same problem with male subjects, especially 'if he can find a room with no other natives looking on.'

//yai, who was one of the women who were photographed naked, proved a reluctant interviewee during her subsequent work with the gramophone. It is tempting to interpret this as an act of resistance, one which Mrs Snyman had no power over. When asked to translate certain sentences into /Xam, //yai 'added remarks of her own uttered too quickly to take down. As she did not speak very clearly, it is impossible to be sure what these sentences were.'58 Another informant was more forthright in his challenge. When asked to speak more loudly into the gramophone tube, he replied: 'I speak my own language ... I cannot speak louder.'59

Was it with a sense of relief that Dorothea Bleek arrived in Kenhardt on 22 September? Here she interviewed Micki Streep or /Ogen-an, the woman who had been photographed with the digging stick by her aunt. This was one of her most productive meetings. She extracted a wealth of historical and genealogical information about the Streep family, the only living link between her research and that of her Aunt Lucy. By this time she had unfortunately run out of film, which explains why she took no photographs of Micki Streep. Two days later she received a surprise letter from Upington. Mr. Lennox (popularly known as 'Scotty Smith') invited her to travel with him and his daughter 'into the Kalahari'. She immediately wrote to Peringuey: 'I am going to do it, & pay for myself, if I get no help. I don't think an extra person would cost more than his food (it is to be a six weeks trip & start in about a fortnight) ... Of course we may miss the Bushmen, but everyone says Mr. Lennox knows most about them, & that is what we shall go for particularly.'60

Photographing 'Tribe': The /Auni at Kyky, 28 October-3 November

Dorothea Bleek was clearly very excited at the prospect of extending her knowledge of Bushman languages and culture by studying groups further to the north. This, we may add, was very much in keeping with her father's expressed desire before his death, and her aunt's years of work with Kung informants from southern Angola in the early 1880s.

The photographic record that she would produce was very different from her Prieska portfolio. In Prieska Location she was interested in documenting the social relations and rituals in a small /Xam community, one with whom she had had previous contact and with whose language she was 'to a certain extent familiar' (in Racster's words).61 At Kyky on the Lower Nossop, the most northerly destination of their expedition, she met with a group of Bushmen whose language she had as yet no knowledge. They were, according to one of her captions, '/auni Bushman v.unseen Sud Gruppe', that is, a very rarely seen tribe within what she came to classify as the Southern Group. The others in this Group were the /Xam, the //n of Gordonia and Griqualand West, the /nu //en of the Upper Nossop, the Masarwa of the southern Kalahari and the Batwa of Lake Chrissie. The Central Group consisted of the Naron of Bechuanaland and the Masarwa (Tati) of Southern Rhodesia, while the northern group consisted of three 'tribes', including the !kun of Central Angola and the Okavango regions. What motivated her here then was to create a unique visual record of one of the first encounters with this group: a record of appearances but also of cultural practices: dress, ornaments and rituals, again notably dance. She took at least 60 photographs in the space of just a few days.

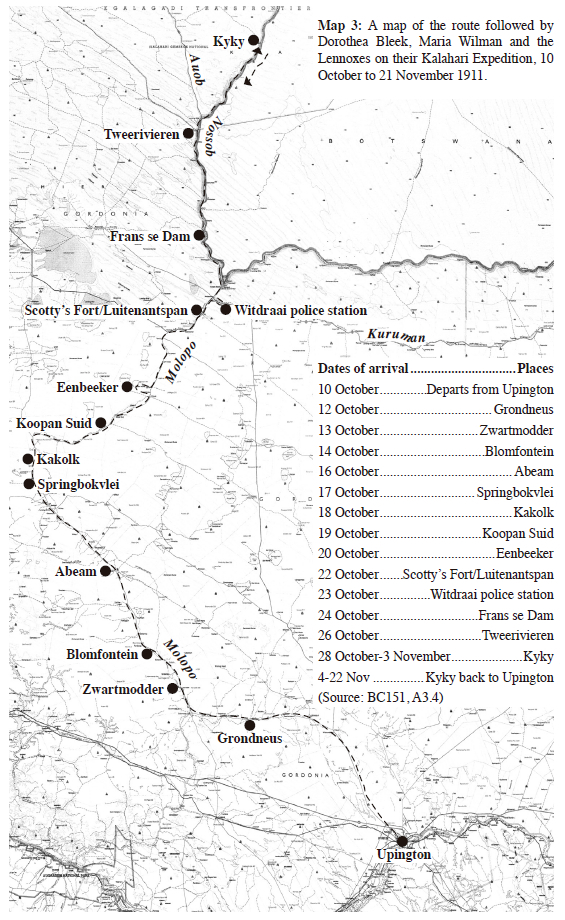

Before we get to Kyky though, we need to set the scene, firstly by tracking the progress of her expedition. As was becoming established practice, Bleek was joined by a female friend. This time it was Maria Wilman, the recently appointed Director of the McGregor Museum in Kimberley. Peringuey appears to have offered to sponsor this leg of the trip as well, as an incoming letter from Upington in the Museum inventory later records: 'Thanking for grant in aid, Miss D.F. Bleek'.62

Thus it was that on 10 October, Mr. Lennox, Hester Lennox, Miss Wilman and Dorothea Bleek set off from Upington with their two guides-cum-wagon drivers, a Korana man named Daniel and a Herero man named Koos. Their store of trading goods was plentiful. In an accounts section of Bleek's notebook,63 she lists all manner of goods for barter: sweets, tobacco, tinderboxes, pocket knives, mirrors, tumblers, cotton, needles, awls, buttons, mufflers, mats, shirts. They had the standard items for camping and a full medicine cabinet, as well as generous provisions including salmon, herrings and sardines, jam, jelly and cocoa, cheese, figs and pickles, not to mention the dates, butterscotch and caramels. Mr. Lennox took a rifle and cartridges, as well as a shovel for digging up bodies. Unrecorded are the items in Dorothea Bleek's own research kit: tape measure, camera and the Bell-Edison contraption.

Bleek turned her notebook into a diary at this stage of her tour. This gives us a much more detailed sense of the texture of daily life and, for our purposes, the very particular contexts within which she took her photographs. We can begin by tracking their progress from the sanddunes north of Upington, site of their first camp, across the farms along the dry bed of the Malopo River. It took a full two weeks for them to get to Witdraai Police Station where they filled up their water tanks and bottles, posted letters, washed clothes and baked bread. Two days later a farmer informed them that Bushmen were to be found further north at Kyky. On Saturday 28 October Dorothea made the following entry:

Got a nice piece of folklore from a Namaqua man. During morning drove on further north across dunes to the edge of Kyky. Stopped under big tree at a place called Skilpatsdraai. I walked with Hester across dunes to the place of some Bastaards who said the Bushmen were a little further to the north & they would send & fetch them.64

She mentioned in a later publication that the Bastaards living here were the 'overlords' of the /auni Bushmen and that most of them owned guns.

Her only photograph of a Bastaard, in this case interacting with an /auni Bushman boy, confirms the obvious point that a landowner in a desert is not necessarily a wealthy man. In her later publication she also commented that the /auni 'were living entirely without water "on the melon"'.65 She made one unsuccessful attempt to photograph a field scattered with melons, but was more successful in her attempts at using melons and half-melons as props in the foreground of a number of her ethnographic photographs. Her diary reveals that she tasted the tsama and found it 'very nice with sugar'.66 For a sense of the physical setting we need to turn to Maria Wilman's notebook:

Kyky. Sand hills various shades of ochre, to brick red . Veld very hot, but kameeldoorn half-covered with tender green & here & there shrubs have tender green on them, in spite of the drought. Everywhere the wacht-een-bietje is shooting, & in a few places is even in flower. The veld consists of 3-doornen & other prickly shoots, housetails & grass. Tsama has been eaten down in parts.67

Wilman indicated that they 'camped out on a flat basin surr[ounded] by dunes with hard-cracked surface'. The insect life included 'ants, red & otherwise, termites; snakes just coming out in number ... lizards, plentiful, of all sorts, geckos, very few flying insects, some flies.' There were also a variety of 'crawlers', but these did not appear at midday, 'so great is the heat of the sand'.68

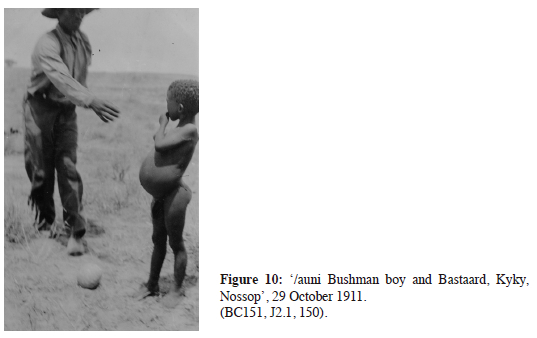

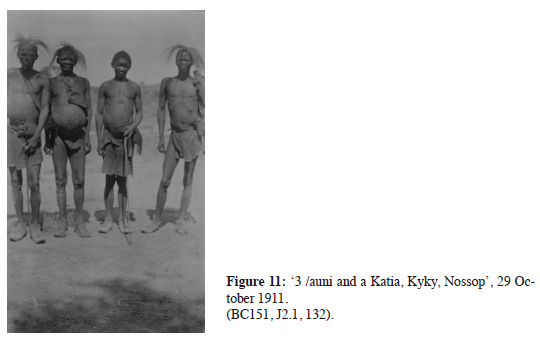

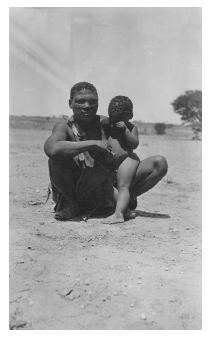

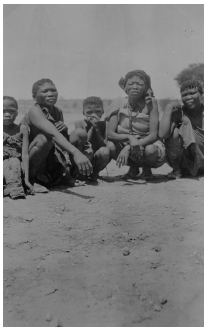

Bleek began photographing the /auni on their second day at Kyky. Her diary entry for Sunday 29 October begins: 'Spent day in the same place. In the morning the Bastaards brought 4 Bushmen, 3 of them /auni, 1 a Katia. Took down language & took one photo' (see above). The Katia, she later wrote, were 'a tribe showing more Kafir blood. Their language is merely a dialect of the /auni speech.'69 Her notebook suggests that this information was gathered by her Korana guide: 'Daniel has found out that . the Katias are descended from Bushmen who as a result of wars got possession of Kafir women and married them. The marriages took place about 3-4 generations back.'70

Her decision to include the Katia man within the frame rather than simply to photograph the three 'purer' /auni Bushmen is significant. Here, as in a number of other photographs, she sought to describe her subjects by means of visual contrast. The Katia man was there to highlight the distinctiveness of the /auni men, in terms of physique but especially attire (the /auni men are adorned with unusual head-feathers). This was also the case in the photograph of '/auni Bushman boy and Bastaard', though here the subjects have not been arranged before the camera.

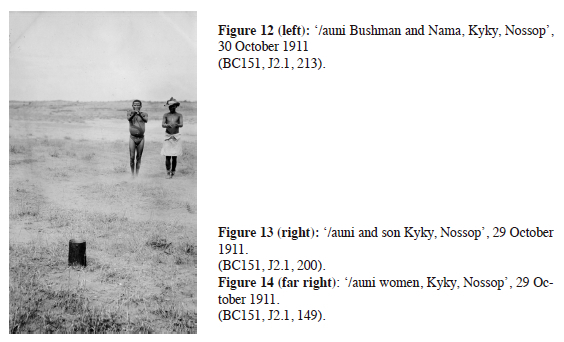

The wording of the caption, '/auni Bushman and Nama' (above), confirms that the /auni were her primary interest. The Nama man was there for comparative purposes. Unlike the photo of the /auni boy and Bastaard, this was clearly posed. The tin can in the foreground acts as a kind of orienting marker, as in a number of the other photographs taken the following day. Beyond the obvious visual contrast between a man in Western clothing wearing a hat and a man in traditional garb, what interests me here is the sense of engagement and seeming ease in front of the camera on the part of the /auni man in particular. He appears to be enjoying the experience of being photographed. This is also the case in numerous other photographs especially those taken of /auni children. In one case the children are smiling, not seemingly too self-conscious about the experience. There is little to suggest that these subjects were fearful of the camera and it is tempting to speculate, especially in the light of the story Olga Racster told of the angry /Xam woman at Prieska, that the experience of living in a more remote location further away from British soldiers and prisons encouraged a less anxious response to being photographed. The /auni on the Lower Nossop were less likely to suspect a photographer of 'drawing up some contract which would make the children our servants.' Bleek went on to record:

In the afternoon a whole troop of men & women came down - one Katia man, his daughter-in-law, the rest /auni. Took a few photos, mostly of the women.

Sun went down. Took down some words - bought a lot of curios. Paid old Salmon for bringing in the troop - a shirt ... Same to younger Bastaard for fetching them. Troop went off after dark ... Very interesting.

What I find interesting is the gendered way in which the /auni photographs were framed. There are numerous photographs of /auni men, many of /auni women, and also quite a number of groups of either men and children, or women and children. There is, however, not one photograph of an /auni man and woman together. There were presumably families among the 'troop' that Bleek photographed. Why then did she choose to separate the sexes in this way, in a way that contrasts so markedly with her Prieska Location series?

My guess is that she was wanting to accentuate the sense of a traditional culture, of a seldom seen Bushman 'tribe' who still ordered their society along established gendered lines. Her inability to communicate effectively in /auni is another important reason. She perhaps did not know exactly what the family structures were and might have found it difficult to establish given that 'interpreters were difficult to find'.71 This helps to explain why her notebook took on the format of a diary rather than a record of fieldnotes rich in words and sentences, as had been the case in Prieska. This might explain, also, why the people she photographed were not named in the captions. She had little knowledge of their language and only interacted with them for a few days. As she revealed in her private notes: 'I could not understand the /auni.'72 She simply did not get to know the people she was photographing well enough to work out their kinship relations, let alone their names. Hence the plethora of general captions: '/auni man', '/auni woman', '/auni boy' (or plural forms) as opposed say to '/kham Bushman family Prieska. Kaiki wife of Thomas Bammus with her children' or '/kham grandmother and granddaughter, Prieska. Rachel and Lena'.

Another aspect of /auni culture that drew her attention were items of material culture. Where she was interested in feathered headgear in the case of /auni men, in the case of /auni women it was the leather-and-beaded bags that drew her attention. A partial inventory of her 1911 photographs lists '/auni bags' as items 6, 7 and 8. Unfortunately none of these photographs have survived,. Dorothea probably bought or bartered such bags. The South African Museum's Ethnological Collection includes a range of consecutively numbered material artefacts collected by Dorothea Bleek. They were donated to the Museum, probably from UCT's Bleek Collection and included /auni poison sticks, /auni quivers, /auni arrows, an /auni firestick and an /auni knife.73 These may all have been collected in 1911.

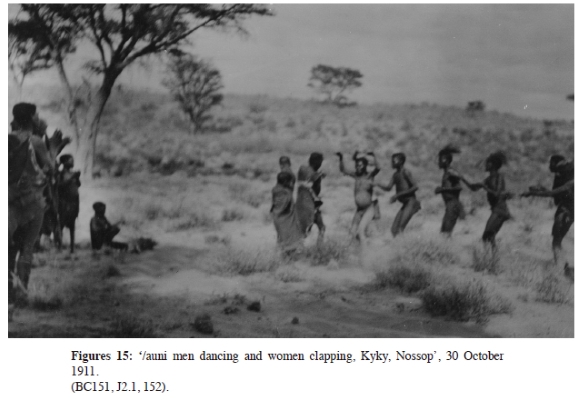

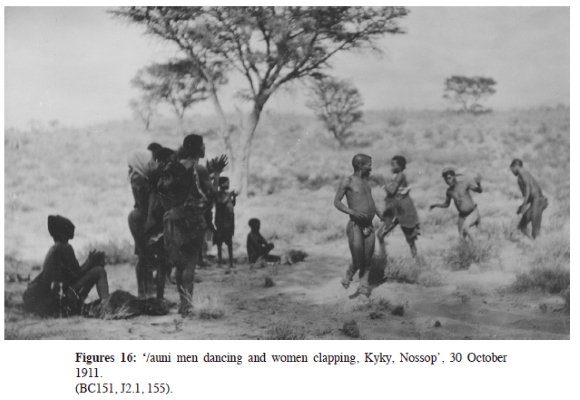

Dance was a more familiar aspect of her reconstruction of Bushman life in visual form. Her diary entry for Monday 30 October reads:

Whole troop of Bushmen came down early. Dance 2 dances & began a third.

1 dance of thirst

2 grass dance

3 lion

Took photos of them dancing, then singly. Took 3 records on phonograph.

These dances must have been one of the highlight of Dorothea's six-month trip. She took about ten or twelve photographs of the /auni dancing, although I find it very difficult to piece these together into any obvious sequence, or even to relate them in a satisfying way to her unusually detailed written account of what the dances represented. It may be that the photographs show a different dance altogether. The roles of the men and women were clearly and separately defined, as these photographs and written accounts indicate.

1. The dance of thirst:

men dance in a circle round the little bushes, trampling on one foot & then on the other. Sometimes they wave their arms about & sometimes bend. Their knees are mostly not straight. The Katia waved his bush & gesticulated much. The women danced in a line, clap their hands and sing in high, shrill voices. By & by a woman comes out with a piece of tsama & pretends to sprinkle the men as they pass out of the tsama (?) The men bend lower when sprinkled & go through contortions expressive of relief & gratitude.

Then another woman comes out & does the same. This is to imitate the falling of the rain after the long thirst. The women dance beside the line while sprinkling the men. When the dance finishes the men all collect before the women & make a kind of fantastic bow.

2. The grass dance:

Some of the men, especially the young ones, take a tuft of grass in one hand. They dance round as before & the women clap & sing. Then one points to a girl, & she dances out into the ring towards him, makes a repellent gesture, mostly with her foot & dances back. Those youths without grass, used their arms to point & beckon with, the Katia his stick. Older men danced too, but did not call out to partners. The prettiest little girl was greatly in request & kicked dust to her admirers. Later on in the dance some of the women danced in the ring, a man behind or beside each, pretending to put his arms round her with many gesticulations. The woman dances on unheeding & the man soon turns off.

3. The lion dance (not completed)

The women sing, the men dance round as before. One youth is the lion. He leaves the line, crouches, rolls his eyes & approaches the line of women dancing in this manner. The women however were tired & left off singing. It is said - he would pretend to spring on a woman, then she lies as if dead & does not stir till the others pretend to revive her.74

The following day she recorded 'Man's song', 'Woman's song of thirst' and 'Woman's song of war with Bondelswarts'. A few days later Dorothea and her expedition headed back towards Upington, eventually only arriving back on 24 November.

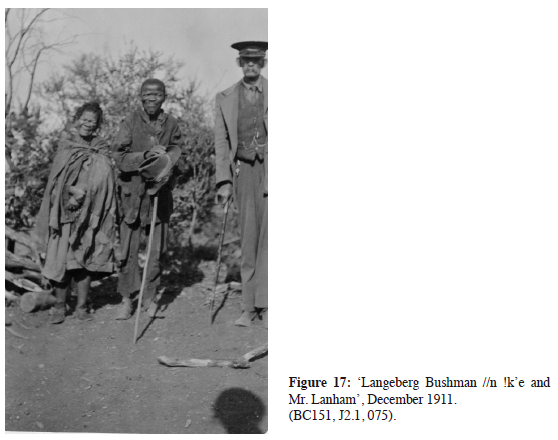

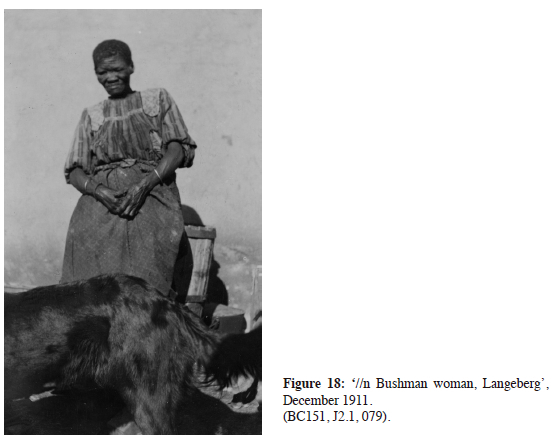

Photographing 'farm hands': //n Bushmen at Mount Temple, Langeberg, 5-19 December

The final leg of Dorothea Bleek's fieldtrip took her to the Langeberg east of Upington (see map 1 above). She later recalled: 'The language of the Bushmen of Griqualand West and Gordonia I wrote down between 1911 and 1915 during several visits paid to Mount Temple in the Langeberg, where my hospitable friends, the Lanhams, had Bushman servants.' In 1929 she reported that 'there are a fair number of these people still living, mostly as scattered farm hands'.75

Between 5 and 19 December 1911, the dates when one of her notebooks places her on Mr. Lanham's farm, Dorothea took 10 photographs. One of these is relatively well known, since Mr. Lanham himself also appears in this image. It features as a full page spread opposite the title page of Nigel Penn's article in Miscast 'Fated to Perish'. As shown above, a moustached Mr Lanham (Lankman in the Miscast caption) stands to the right dressed relatively smartly with a waistcoat and a cap reminiscent of those worn by policemen. He leans on a stick suggesting that he was a man of advanced years. The other Lanhams - his wife or his children - were not included in the frame. The photographer's head has made a chance intrusion in the frame; what one analyst describes as an 'endearing trait' on the part of ethnographic photographers. The angle of the shadow suggests that the image was captured in the late afternoon when the fierce December heat had somewhat abated. The 'farm hands' stand together, a little removed from Mr. Lanham. They may well be a couple. Their clothes are ragged and the posture of holding their hands together in front of their bodies, rather than their arms straight alongside as Mr. Lanham does, suggests perhaps a certain anxiety or sense of submissiveness.

This photograph appears along with three others on a double-page spread in Dorothea's private album. They all depict different individuals. This is very unusual, for in most pages in the album there is at least some overlap across the photographs. Very few of those photographed in Prieska Location, for example, feature in only one frame. The sense of fragmentation is enhanced by the badly blurred nature of the photograph on the far right of the spread.

A close reading of the photographic evidence suggests however, that not all 'Colonial Bushmen' (to use Dorothea Bleek's term) were equally impoverished. Poverty is of course a relative concept, as the photograph of Mr Lanham and his servants well illustrates. In terms of dress at least, our only clear index apart from living quarters, quite a number of those who appear in the background of photographs taken at Prieska Location were well dressed.

This photograph of a female 'farm hand' would encourage perhaps a more graded view of the economic circumstances of those she photographed. Here again, on the basis of dress at least, we have an image that disrupts any blanket notions about desperate impoverishment. The black dog in the foreground, perhaps belonging to Mr. Lanham, seems to have gatecrashed the photographic event. The dog and the farm wall in the background serve as symbols of the domestic environment within which this woman worked. The photographs of men on the farm are all taken in the open field. It is interesting that most of Bleek's Mount Temple photographs feature men, for her fieldnotes reveal that her rich and extensive interviews were conducted almost exclusively with three women: Sabina, Dina and Doorki. Was this woman shown above not one of her interviewees? If so, why did she not enter her name on the back of the print as she did in the case of so many of the Prieska Location photographs?

The answer may to lie in her conscious desire to construct a certain image of farm labourers as scattered and lacking community. Here she was not interested in showing family groups - there are no children featured in the photographs although the diary does suggest such a presence. Neither was she interested in signs of collective or tribal identity, whether expressed through artefacts or rituals like dances and song. She wanted to show a broken culture of scattered and nameless servants, and framed and archived her photographs accordingly.

Her last notebook entry at Mount Temple dates to 19 December. Appropriately enough she appears to have been showing her informant a copy of the front cover of the newly published book, Specimens of Bushman Folklore. Perhaps she had collected her copy in Upington in late November. Her Aunt Lucy had only finished the preface in May. Her informant did seem to understand what the gold-embossed illustration on the front cover was showing. The translated text reads: 'the old woman, she has a digging stick, digs oinkies, she puts them in the bag, her bag, the old woman's bag, she wears bracelets, a shell ornament it is, she has a Duk.'76

She returned to Upington from Mount Temple in the week before Christmas. Her correspondence with Peringuey indicates that she then journeyed to Kimberley to spend time with Maria Wilman before taking the train back home to Cape Town in January of 1912.

Conclusion

This article has sought to tell a more complete story about Dorothea Bleek's fieldtrip of 1911 than the one she told to readers of Bantu Studies in 1936 or the one that we have been told in Miscast (1996). Here the photographic record has been used to reflect back on her father and aunt's /Xam researches, and to convey a sense of the loss of a rich culture on the very verge of extinction that Wilhelm and Lucy had been able to save.

When we examine the photographs in relation to the written records produced at the time a very much more complex story emerges. Her interest in Prieska Location was to record not so much poverty, but the life of a community that she had come to know. She spent almost two weeks in Prieska Location in July and August 1911, having already spent time there on her previous fieldtrip, and became acquainted with the families and their histories. On her subsequent expedition to Kyky, north of Tweerivieren, she produced what might rate as among the first extensive visual records of a group of Kalahari Bushmen, in this instance the /auni. She was interested here in documenting 'tribe' rather than community. This was not only because she neither spoke their language, nor stayed long enough to get to know the people, but because they were 'very unseen' and she evidently felt that a photographic record of their appearance, dress, ornaments and dances would make a valuable ethnographic contribution, along with the descriptions in her field diaries. In the case of the //n Bushmen at Mount Temple, she was seemingly interested in generating an impression of poverty, though one which we should be cautious about reading at face value. For there is at least some evidence to suggest that she consciously crafted a stereotype of the impoverished 'farm hand', by excising for the most part any signs that might suggest otherwise.

In more general terms, I have tried to make a case for taking Dorothea Bleek's ethnographic (or even anthropological) work more seriously. While she tended to downplay her own contribution and see it simply as furthering the legacy of the 'one Dr. Bleek', we should give her more credit, perhaps, than she gave herself. Her photographic output from the 1911 expedition was a rather remarkable one, not least for the fact that it generated some 158 photographs of Bushmen, individually and in groups, in an era when the interests of photographers were typically very much more eclectic. Her sustained research on the /Xam, /auni and //n Bushmen as subjects of linguistic, physical anthropological and especially cultural interest, encourages the view that Dorothea Bleek deserves to be ranked as one of a pioneering generation of women scholars in southern Africa.

* I am grateful to Jenny Sandler for drawing up the maps that feature in this article and for her creative integration of the photographs and text. Thanks to Lesley Hart of the Archives and Manuscripts Department of the University of Cape Town Libraries for making available to me her own transcripts of the field-diary section of Dorothea Bleek's Kalahari notebook and for permission to reproduce the photographs from Dorothea Bleek's album. Thanks to Patricia Hayes for enthusiastic and incisive comments on an earlier draft, to Russell Martin and Tanya Barben for extensive and detailed edits on this draft. Janine Dunlop of the Archives and Manuscripts Department, Gary November of UCT African Studies Library and Cecil Kortjie of the Photographic Department of the Iziko South African Museum provided the scans at short notice. A special thanks to Gerald Klinghardt for acting as an ever patient guide on numerous trips to the South African Museum in quest of materials relating to Dorothea Bleek.

1 University of Cape Town Libraries, Archives and Manuscripts Department, J2.1 'Album containing photographs of Bushmen dancing, as well as their shelters and implements. Taken by D.F.Bleek at Van Wyksvlei, Prieska, Gordonia, Nossop, Lake Chrissie, Bechuanaland and Angola, n.d. c1920s-1930s. Descriptions on the backs of the photographs.' In 2001 Lesley Hart, the head of the Archives and Manuscripts Department, and Kate Murray, a visiting American scholar, made these photographs available for viewing on CD-Rom. Their package includes a full list of the annotations written by Dorothea Bleek on the reverse of each print.

2 Archives and Manuscripts, Bleek Collection Provenance File, D1366, 'List of items in Donation from Dr. D.F. Bleek to Jagger Iibraiy, 2nd Donation ... 296 photographs, 30 October 1947'.

3 BC151, J2.2. One of the photographs in this collection shows the linguist Mr. Lestrade in a group portrait with Chief Sebele II and his litona' at Molepolele.

4 D.F.Bleek, 'Bushman Terms of Relationships', Bantu Studies, vol. 2(2), Dec. 1924; D.F.Bleek, 'Bushman Folklore', Africa: Journal of the International Institute of African Languages and Cultures, vol. 2, 1929, 302-13, which Roger Hewitt, the leading analyst in the field, described as a 'good but brief sketch of /Xam oral literature' (R.L.Hewitt, Structure, Meaning and Ritual in the Narratives of the Southern San (Hamburg: Helmut Buske Verlag, 1986), 15); D.Bleek, 'Bushman Grammar: A Grammatical Sketch of the Language of the /xam-ka-!k'e', Zeitschrift für Eingeborenen-Sprachen, vol. 19, 1928-9, 81-98 and vol 20, 1929-30, 161-74 and reproduced in J.Hollmann, ed., Customs and Beliefs of the /Xam Bushmen, 389-420, which the linguist Tom Guldemann describes as still being 'of particular importance for the linguistic research on the language.' (T.Guldemann, 'Introduction to Bushman Grammar', 387).

5 J.C.Hollmann, ed., Customs and Beliefs of the /Xam Bushmen (Johannesburg: Witwatersrand University Press, 2005).

6 E.M.Shaw, 'Dorothea Frances Bleek' in W.J. de Kock, ed., Dictionary of South African Biography (Pretoria: National Council for Social Science Research, 1968), vol. 1, 82.

7 It is possible that a few of the 37 photographs taken in Prieska Location date to a previous fieldtrip in August of 1910, but the evidence here is contradictory.

8 D.Bleek, 'Notes on Bushman Photographs', Bantu Studies, vol. 10, 1936.

9 D.Bleek, 'Notes on Bushman Photographs', 202-3. This echoed her concluding claim in her earlier article on 'Bushman folklore': 'Not one of them knew a single story ... the folklore was dead, killed by a life of service among strangers and the breaking up of families.' (312) Her notebooks and the article written by her travel companion of the 1911 expedition, Olga Racster, in the Cape Times (13 September 1911) suggests that this was not entirely true, as is partially explained in this article.

10 D.Bleek, 'Notes on Bushman photographs', introductory comments on photographs number 9, 10, 18, 22, 24.

11 In two individual portraits, for example, Pippa Skotnes presents close-ups of just the hands of those photographed - in one case holding a hat, in another held together. The group photograph, the only visual evidence of a more collective sense of community presented by Dorothea in Bantu Studies, is now chopped in half with the two sections appearing above and below each other on the same page. (P. Skotnes, ed., Miscast: Negotiating the Presence of the Bushmen (Cape Town: UCT Press, 1996), 82, 84).

12 N.Penn, 'Fated to Perish' in Skotnes, ed., Miscast, 80-91.

13 P.Skotnes, ed., Miscast, 88, 90.

14 J.Hollmann, ed., Customs and Beliefs of the /Xam Bushmen, xxvii. The publication referred to is D.F.Bleek, The Mantis and his Friends, which was published in 1923 rather than 1924.

15 P.Davison, 'Material Culture, Context and Meaning: A Critical Investigation of Museum Practice with particular reference to the South African Museum' (D.Phil., Archaeology Department, University of Cape Town, 1991), 145-58; P.Davison, 'Human Subjects as Museum Objects: A Project to Make Life-Casts of "Bushmen" and "Hottentots", 1907-1924', Annals of the South African Museum, vol. 102(5), 1993.

16 J.Deacon, 'Foreword' to J.C.Hollmann, ed., Customs and Beliefs of the /Xam Bushmen, xiv.

17 On the generation of pioneering women researchers, see D.Gaitskell, 'Introduction', Journal of Southern African Studies, Special Issue: Women in Southern Africa, vol. 10(1), 1984, 1-4.

18 On EH Man, see E.Edwards, 'Science Visualised: E.H.Man on the Andaman Islands' in Edwards, ed., Anthropology and Photography, 108-21; on Jenness, see Edwards, Raw Histories, 84-102; on Dixon, see S.A.Krause, 'Photographing the Vanishing Race', Visual Anthropology, vol. 3, 1990, 213-33.

19 E.Edwards, Raw Histories, 27-48.

20 B.A.Wolpert, 'The Anthropologist as Photographer: The Visual Construction of Ethnographic Authority', Visual Anthropology, vol. 13(4), 2000, 322-3; see also Edwards, Raw Histories, 45-48.

21 R.J.Gordon, Picturing Bushmen: The Denver African Expedition of 1925 (Cape Town, Windhoek and Athens Ohio, 1997), 10.

22 M.Godby, 'The Interdependence of Photography and Painting on the South West Africa Expedition of James Chapman and Thomas Baines, 1861-1862', Kronos, Special Issue: Visual History, vol. 27, Nov. 2001, 33-41.

23 J.Silvester, P.Hayes and W.Hartmann, ' "This Ideal Conquest": Photography and Colonialism in Namibian Histoiy' in Hartmann, Hayes and Silvester, The Colonising Camera: Photographs in the Making of Namibian History (Cape Town and Windhoek, 2002), 11.

24 His brother Lulu, the expedition photographer, was drawn to photograph all manner of things - 'anything from a monkey to the moon' in Farini's own phrase. (G.A.Farini, Through the Kalahari Desert: A Narrative of a Journey with Gun, Camera and Notebook to Lake N'Gami and Back (London, 1886)). This is confirmed when we look at the entiy under 'photographing' in Farini's travelogue: there are just two references to 'the Natives' and a range of others including 'an explosion', 'a lion', 'Kimberley' and of course 'the Falls'.

25 A.D.Bensusan, Silver Images: History of Photography in Africa (Cape Town: Howard Timmins, 1966).

26 Quite how rapidly the technology was changing is also evident if we compare Dorothea Bleek's album of 1911 with that of 1919: the visual quality and potential range of subject matter has grown considerably in eight short years. (See BC151, J2.1, J2.2)

27 Although there are some suggestions that she had taken photographs on her 1910 expedition to Prieska and the Langeberge, the evidence here is ambiguous and uncertain.

28 R.Gordon, Picturing Bushmen, 60.

29 In an interesting recent article, Marijke du Toit argues that the photographs that Ellen Hellmann took at Doornfontein in 1933 (which appear in her 'Rooiyard' manuscript) were concerned more with space that with people. With the exception of a woman named Angela whose story she relates in her text, people walk in and out of her often low-angled frames, which create an off-centre and almost swirling sense of the spaces of the inner-yards. M. du Toit, 'The General View and Beyond: From Slumyard to Township in Ellen Hellmann's Photographs and the African Familial in the 1930's', Gender and History, Special Issue: Visual Genders, vol. 17(3), Nov. 2005, 605-618.

30 P.Carstens, G.Klinghardt and M.West, Trails in the Thirstland: The Anthropological Field Diaries of Winifred Hoernlé (Cape Town: UCT African Studies Centre, 1987), diary entries on 2, 5, 7, 11, 14, 19, 24, 29 October and 1, 5 November 1912.

31 C.Rassool and P.Hayes, 'Science and Spectacle: /Khanako's South Africa, 1936-1937' in W.Woodward, P.Hayes and G.Minkley, eds., Deep Histories: Gender and Colonialism in Southern Africa (Amsterdam: Rodopi, 2002), 129-139.

32 J.Clifford, 'Notes on (field)notes' in R.Sanjek, ed., Fieldnotes: The Makings of Anthropology (Ithaca & London: Cornell University Press, 1990), 47-70.

33 We know that is was an Edison-Bell from much later correspondence between the musicologist PR Kirby and Dorothea regarding the wax cylinder recording of music and songs collected on this field-trip. UCT, Kirby Collection, BC750, Dorothea Bleek to PR Kirby, 4 May 1936.

34 Thanks to Emil von Maltitz for this information.

35 See A.Bank, Bushmen in a Victorian World: The Remarkable Story of the Bleek-Lloyd Collection of Bushman Folklore (Cape Town: Double Storey, 2006), 3-7 for a brief account of their three expeditions between to rock art sites in the Eastern Cape and Orange River Colony between 1905 and 1907.

36 We know this from an envelope stuck in the front pages of the copy of O.Racster, Chats on Violoncellos (London: T.Werner Laurie, 1905) in the African Studies Library at UCT. The copy was donated by Jessica Grove, who co-authored with Olga a later and better known book, The Journal of Dr. James Barry (London and Cape Town, 1932). Racster had a long and illustrious career as a popular writer and her best known work is probably Curtain Up! The Story of Cape Theatre (Cape Town and Johannesburg: Juta & Co., 1951). I am grateful to Russell Martin for alerting me to Racster's literary output.

37 See A.Bank, Bushmen in a Victorian World, 383-5.

38 'Treble Violl' (Olga Racster), 'Bushman Hunting: A Trip to Bushman Haunts', Cape Times, 13 September 1911.

39 A.R.E.Burton, Cape Colony Today, 228.

40 For genealogical information about Janicke, see BC 151, A3.3, 134-7; for genealogical information about Klaas, Guiman and Rachel the fullest source is BC151, E5.1.21.