Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Kronos

On-line version ISSN 2309-9585

Print version ISSN 0259-0190

Kronos vol.32 n.1 Cape Town 2006

ARTICLES

Binnelandse Reise (Journeys to the Interior): Photographs from the Carnegie Commission of Investigation into the Poor White Problem, 1929/1932

Marijke Du Toit

Department of Historical Studies, University of KwaZulu-Natal

Introduction

'We wanted as far as possible to study the poor whites in their natural habitats - on the farms, in the cities, in the diggings.' This was how the authors of the Carnegie Commission of Investigation on the Poor White Question explained their decision to travel through South Africa for their research. This commission, which published its findings in 1932, has long been associated with an era of heightening efforts by Afrikaner nationalist political, cultural and philanthropic organisations to shore up the boundaries of a blanke volk through an explicit and systematic effort to racialise poverty. This was certainly the first project of South African social science that attempted to comprehensively enumerate, describe and explain the nature of 'white' poverty. In their own eyes, commissioners were at the cutting edge of modern, dispassionately scientific research. Aiming to '[find] facts and causes' so as to offer recommendations suggested 'by the study of the actual conditions',1they established their authority through 'methods of gathering data' that eschewed the approach of previous commissions - namely to hear evidence from experts and members of the public at formal 'sittings'.2

This was also the first South African commission of enquiry to present photographs as well as written text. The published report offered an answer to the question '(w)hat is a poor white' and three of the five volumes include several pages of photographs of poor whites. Psychological Report: The Poor White by R.W. Wilcocks has consecutive pages of pictures. M.E. Rothmann's Mother and Daughter of the Poor Family and E.G. Malherbe's Education and the Poor White have several photographs interleaved with text. It was Malherbe, trained in sociology at Columbia University and specialising in research on education, avid supporter of J.C. Smuts and the ideals of a white, bi-lingual South African nation, who contributed this visual evidential record. He also compiled and captioned three albums of photographs taken on his travels for the Carnegie Commission. Today, these are archived together with field notes and manuscript copies of Carnegie-related research papers.

What possibilities do these photographs offer for historical analysis and understanding? In the only extant, brief discussion of the published photographs, Michael Godby considered Malherbe's work as an early example of social documentary photography in South Africa, comparing it to photographs produced in the early 1980s for what was then pointedly styled a 'second' Carnegie Commission, one that rejected the racial focus of the first in order to examine the extent of black poverty. For Godby, the first commission made limited use of photography's rhetorical possibilities, so that a 'simple factual basis' characterised its use of photographs. Godby's analysis of the photographs was fuelled by strong normative intent: writing for a volume celebrating South Africa's new democratic order, he judged and dismissed the earlier pictures for their racism and for the photographer's limited, unsympathetic engagement with his subjects.3

Here, I explore other ways of researching and writing about Malherbe's photographs as historical documents. Malherbe shared racialised concerns about poverty with fellow liberals and ethnic Afrikaner nationalists. His studies at Victoria College had been followed by several years of work towards a PhD in Sociology in the United States of America. Did his framings of people whom he considered white and economically marginalised differ from earlier practices of picture-taking? How did Malherbe's published and unpublished pictures of men, women and their families help explain 'white' poverty? Was his photographer's eye informed by localised discourses or also by ideas from further afield, particularly the U.S.A? In order to begin answering these questions, I read the pictures together with images of poor 'white' people from different early twentieth century South African circuits of photography. I then go on to discuss how Malherbe's pictures were put to work as part of the report. I do so as part of larger effort to investigate how raced subjectivities were articulated within the South African visual economy, and how cameras were used as part of conceptualising, explaining and responding to poverty.4

In the only discussion thus far of a few pictures from Malherbe's albums, Sally Gaule was careful to justify her treatment of the pictures as documentary 'despite their impression as snapshots'.5 In fact, it is difficult to place these pictures firmly within any genre of 'social documentary' photography. Photographers in South Africa would only begin to consciously participate in a newly emerging practice of social documentary photography from the late 1930s and particularly during World War Two. Malherbe was also taking his Carnegie photographs several years before the launch of the FSA social documentary project in the United States of America. Here, I consider his picture-taking precisely as snapshots taken by as part of sociological research, by a researcher whose ideas about the study poverty were influenced by North American quantitative research methodologies and racial science.

However, I argue that while Malherbe's photography was a form of sociological note-taking, they were more directly inspired by popular pastimes of snapshooting than any academic practice. The negatives of Carnegie album photographs are still filed in their original Kodak Film Wallet or Illingfoth's Roll Film and Print Wallet ('The Fast Film catches the sunny smile').6 An amateur photographer who used a basic fixed focus camera, Malherbe took pictures for leisure and friendship, also on the Carnegie journey and for his album - an image-text that records research and also celebrates the journey into South Africa's rural interior. He pasted numerous pictures of arm blankes (poor whites) into the album, organised chronologically and according to the area visited. Large numbers of the pictures were therefore of people identified as relevant to the study. But the albums also show commissioners - interacting with research subjects, driving their car, relaxing. I argue that this visual narrative may be read as a more complex representation than is available in the published volumes of raced and class-inflected subjectivities, of the photographer and his colleagues' interaction with 'poor white' subjects, and their relationship with the colonised, white-owned spaces of platteland.

Snapshooting for social science: Malherbe's published photographs of 'poor whites' in historical perspective

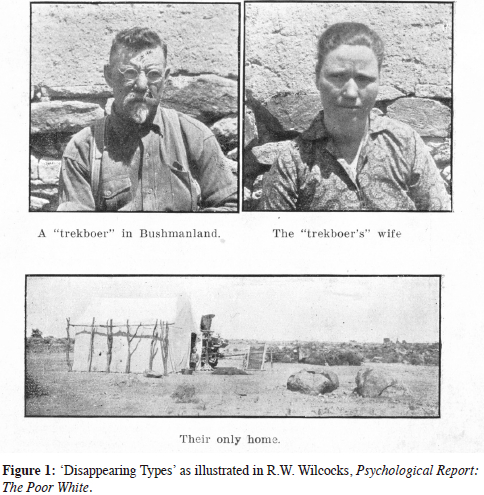

Three out of the five volumes of the Carnegie Report include photographs. Fifty-four consecutive 'Illustrations' are included towards the end of R.W. Wilcocks's Psychological Report: The Poor White. These start with pictures of 'Disappearing Types' - itinerant farmers, sharecroppers and transport riders - which all refer back to a chapter discussing their supposedly characteristic roving spirit. The first are of a 'trekboer' and his wife, shown facing the camera, in small head and shoulder portraits, above a picture of a tent and wagon, 'their only home'. A section complementing the chapter on 'Rural Housing Conditions of the Poor' presents small figures near their dwellings of stone, wood, clay and reeds. In a number of head and shoulder shots, individuals are also presented simply as 'types of womenfolk' and 'menfolk - impoverished type', with no further attempt at explanatory captions or reference to specific discussions. It is easy to see how these pictures of anonymous individuals were dismissed as unimaginative presentations of poor people. Social conditions of poverty are signified by poor housing, and portraits of 'types' are shown in a cumulative record which presents its subject matter as self-evident.

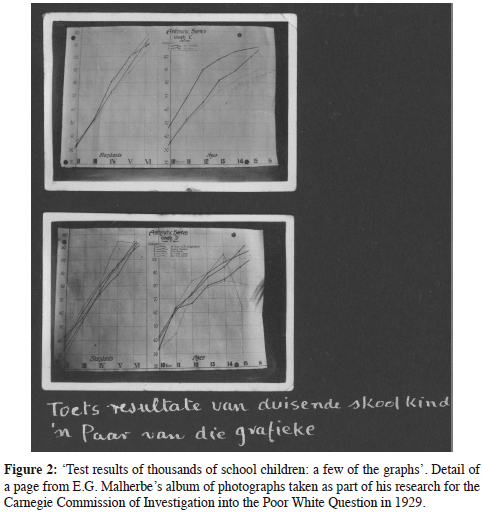

But the Commission's visual presentation of the evidence of white impoverishment - in its published form, and as compiled in the more private space of a researcher's album - is worth considering more closely, as it involved a new application of visual technology in South Africa. On one page of Malherbe's research album and together with photo's captioned as the typical farm houses of poor whites, he pasted two photographs showing not countryside scenes or people but pieces of paper inscribed with words, numbers and lines. Malherbe's particular brief as Carnegie Commission member was to determine the academic progress and intelligence quotient of school children. In this aspect of his work, he was strongly influenced by contemporary American trends in quantitative and applied research.7 The two pictures were specified as graphs showing test results of 'duisende' (thousands) of school children.8

At first glance and encountered together with his other photographs, the pictures of the graphs seem oddly anti-photographic. Blandly impenetrable as to the actual subjects of research, their indexicality seems to lack the 'here-now' - the specificity of place and time - of photographs presenting people and places that once were. But presented as they are in the small size typical of Kodak-style snapshots - hardly available for easy perusal - Malherbe's research results have their own 'insistent anteriority'.9 They comprise a confident assertion of his scientific method and confront us with the assumptions of South African social science, circa 1929. Facts about the poor were there to be sampled, abstracted and presented as typical of the whole, whether visually or via words and numbers.

It seems unlikely that Malherbe encountered the use of photography as part of research practice at Columbia, where journal publications of the time certainly included no photographs.10 Evidently however, the contemporary assumption that predicated photography - of a world 'productive of facts' that could be communicated transparently and 'free of the complex codes through which narratives are constructed' - dovetailed neatly with his efforts to help establish applied social scientific research practice in South Africa.11 How and to what purpose Commissioners mobilised photographic indexicality becomes clearer when their representations of pale-skinned, economically marginal South Africans are compared to earlier instances of 'poor whites' photographed. This comparison helps clarify the difference of their use of the camera for Malherbe's sociological research, of how they set about recording poverty, and how text and pictures were combined to specify poor whiteness.

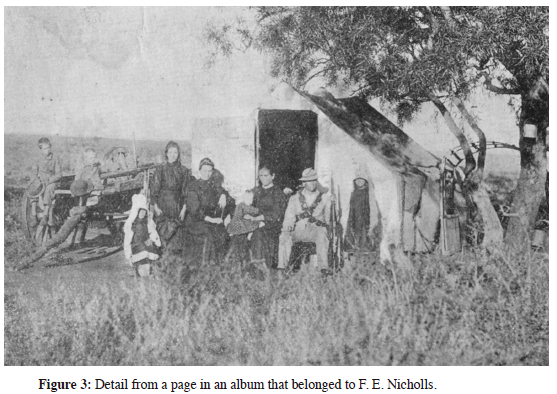

An album of clippings from English newspapers and magazines compiled during or soon after the South African War include two early examples of news photography showing Boer families displaced by war, and pictures of black families in old clothes near makeshift shelters. The latter pictures are presented as of incidental interest to readers ('Natives - Beaufort-West') and with no reference to poverty. The former, however, are probably some of the earliest pictures of persons named as 'poor white'. Dress and demeanour in the picture captioned 'Poor Whites' Home in the Christiana District' suggest that this phrase, soon to be so specifically and pejoratively applied to poor people often regarded as separate underclass yet claimed as white, here referred to families whose economic circumstances had recently been reduced by the war.12

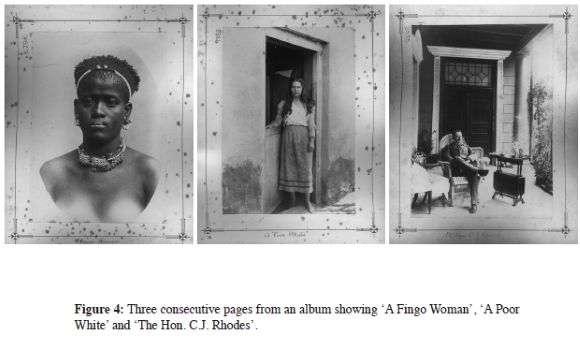

Another rare, early portrait naming poor whiteness was pasted into a post-war album. Its visual impact is partly derived from contrast - on the previous page was the picture of a 'Fingo Woman'; the next showed the figure of Cecil John Rhodes (the album, which had belonged to an English-speaking Capetonian, also featured, for example, 'A Typical Boer' and 'A Transvaal Volunteer'). As with numerous colonial photographs, the young African woman, shown against a blank background, had clearly been photographed for the pattern of beads against her skin signifying tribal identity. Next, and in dishevelled juxtaposition, a young woman stands barefoot, her loose hair uncombed, wearing a worn skirt and blouse. The plain doorway and flaking walls belong to a world remote from the amply furnished veranda upon which 'The Hon. C.J. Rhodes' enjoys leisurely comfort. It is unsurprising that the politician and icon of British imperial ambition was the only person named as a titled individual, but intriguing that while one anonymous young woman is summarily labelled 'Fingo', the other, using quotation marks, is more tentatively described as 'a "Poor White"'.13

From its launch in 1916 the Afrikaner nationalist cultural magazine Die Huisgenoot included occasional photographs of impoverished whites - never naming them explicitly as arm blank, perhaps because the phrase (employed elsewhere in the magazine, in cautionary texts imploring readers not to discriminate against poor white brethren) already had a pejorative inflection. As I have discussed elsewhere, their claim to whiteness and as fellow Afrikaners worthy of help was asserted by writing them into narratives about the heroic past of voortrekkers pitted against black savages.14

All of these pictures drew upon the camera's indexical capacity (the idea of the photograph as a chemical trace, 'a physical, material manifestation of a past reality')15 in order to convey circumstances of 'white' poverty, evincing a disinterest in the economic circumstances of black persons that would remain consistent in Malherbe's photographs. The newspaper pictures from the war showed displaced 'Boer' families with meagre shelter or as refugees on the road. The album portrait and pictures of elderly voortrekkers recorded surroundings that signalled their straightened circumstances - a corrugated iron wall, a small ill-furnished room. But none of the photographers had shared Malherbe's idea of the camera as a tool for the systematic collection of relevant facts: the latter showed a series of the economically marginal together with captions indicating relationship to land, or in front of houses that signalled straitened circumstances. The documentary impetus of turn-of-the-century news photographs and portraits were used to show curiosities of passing interest. By contrast and in an approach that resembled practices of social survey photography from Britain and elsewhere, Malherbe attempted a systematic record of conditions that precipitated 'white' poverty, in order to argue for social reform.

In fact, the many photographs of needy children that appeared in Die Huisgenoot throughout the 1910s and 1920s never showed them being poor, even when published in order to raise funds - rather, boys and girls were dressed in clothes and shown in surroundings that signified their rescued status as recipients of charitable help. Another publication, the Pact government's Social and Industrial Review, printed frequent photographs of economically marginal individuals, but the closest it came at showing whites as poor were intermittent pictures of men queuing at unemployment offices. Reports on progress on the Labour Department's settlement schemes for landless whites often showed the tiny figures of participants next to modern farm machinery, with a clear emphasis on the success of this plan for rural modernisation. These were not part of an effort to collect facts about the poor nor to 'document' signs of poverty with cameras. Instead, those who photographed poor 'white' people before Malherbe often (perhaps sometimes in collaboration with their subjects) used posture, dress and positioning in space to 'show' identity and worthiness of assistance. Performances of respectability and historical authenticity characterised Die Huisgenoof s photographs of impoverished old people. Thus an elderly woman, sitting in an empty room, leaning forwards and looking straight at the camera, held a large Bible in her hands, while accompanying text provided her voortrekker credentials.16 In a memorable picture from the Social and Industrial Review, a group of harvesters posed in a tableau of manly strength.17

The classificatory impetus of the Commissioners' social scientific approach emphasised class position and lack of economic mobility, and was careful not to suggest intrinsic difference. Even so, people shown in the Carnegie photographs were now systematically named as both poor and white. More accurately in fact, while captions to pictures in the published volumes did not often include these adjectives, the photographs were placed in books with uncompromising titles such as (in the case of Wilcocks' volume) The Poor White on the cover. The label arm blank was frequently used in captions to pictures in Malherbe's album. The Commission's explanation of how they identified their subjects combined assertion of the visibility of being 'European' with an underlying uneasiness about invisible, mixed blood. According to Wilcocks, 'anyone having an admixture of coloured or native blood' did not 'strictly fall under the concept [poor white]', and 'practically, ... all those were excluded where such admixture was recognisable by means of ordinary observation.'18 Within the volumes of the Carnegie report, pictures show race as simple matter of fact. Yet frequent verbal anchoring of a distinct underclass as both poor and white mark a shift from previous visual representation where whiteness in photographs was not previously named with such insistence.

It is also with regards to the use of pictures as evidential components to explanations about the causes of 'white' poverty that commissioners used pictures of poorer whites in new ways. It is in the volumes where photographs are interleaved with text - those by Malherbe and by the journalist and leading figure in the Afrikaner nationalist women's philanthropic movement M.E. Rothmann - that photographs are clearly used to build arguments more centrally with words and statistics. Photographs in Malherbe's volume appear intermittently amongst detailed discussion and analysis of statistical data (tables showing, for example, 'Retardation of Boys and Girls in All Public Schools of the Union arranged according to Areas').19 A table correlating 'median ages' and average percentages of 'retarded', 'European' pupils in primary schools throughout South Africa, for example, face two pictures of 'Children on the Diamond Diggings (Lichtenburg)'. Windows to the specificity of place and time, they are anchored by and add credibility to the statistics and analysis.

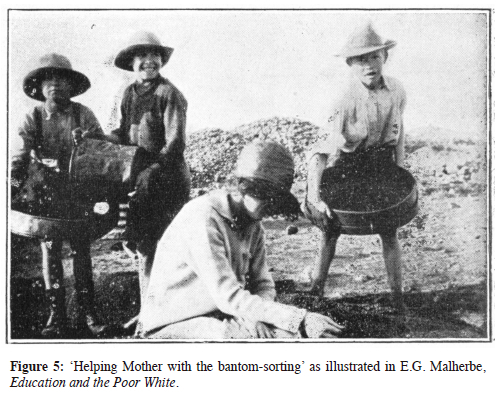

As explanations of white poverty, the photographs used by commissioners helped articulate the commission's overriding concern with the perceived breakdown of poor white men and women's ability to provide their families with (respectively) the financial stability and nurture necessary for the maintenance of social cohesion and economic well-being. A woman crouches in the foreground of the first picture, her face obscured by her hat and hair, seemingly intent on her hands rather than the three children behind her. They face the camera with lively expressions directed at the photographer as they pause, momentarily, in their allotted tasks. They are '(h)elping mother with the bantom-sorting'. Beyond them are the bare, dusty spaces of the diamond fields.

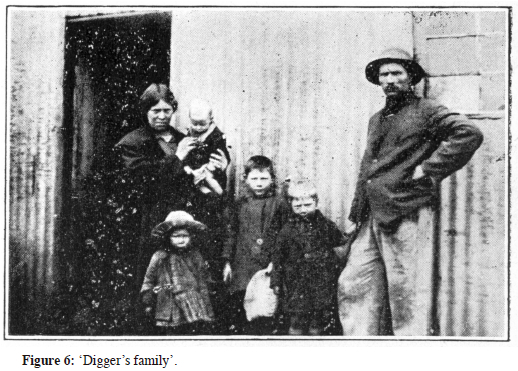

Malherbe's text discussed the various reasons why children of the poor failed to regularly attend school - hence also the caption with its suggestion of 'mother''s irresponsibility. The second picture on the page shows members of a digger's family. The mother stands near the open, dark doorway of a corrugated iron house, holding a baby and flanked by three young children. The viewer's eye is drawn to the slightly foregrounded figure of a man, hat on head, hand on his hip and striking something of an attitude for the camera. The caption: 'The father had just finished chopping up baby's chair as last bit of firewood'. Within the broad framework of the report, the photographs are factual evidence of how white poverty is compounded by parental incapacity.

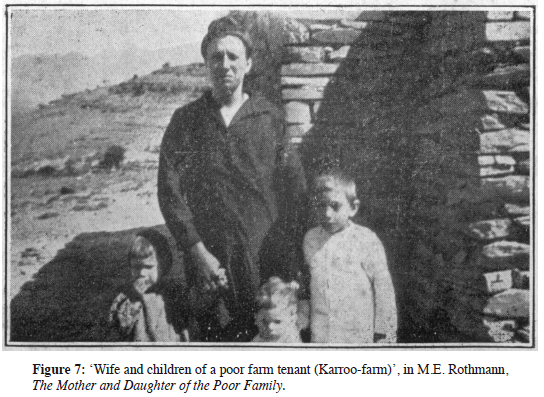

In Rothmann's volume, photographs implicitly support and gather meaning from her argument as to the contemporary inadequacy of poor white motherhood and from uneasiness about the blurring of class and racial boundaries and (expressed in carefully tempered language) uncontrolled sexuality. Poor mothers and daughters had 'a vague and confused idea of social relationships' and lacked 'social sense'.20 At worst, people made homes 'under the impulse of the sex urge'. They were 'slum-makers' in poor neighbourhoods and on 'the open veld' and lived like the 'more backwards among the coloured people'.21 Rothmann also argued that the isolation typical of itinerant farmers, sharecroppers and day labourers 'fail to preserve any necessity or advisability of intercourse with other homes or communities'. Like Malherbe, she emphasised that such parents could not plan an economically viable future for their children. The mother was 'the central figure in the home'. And yet, '(t)oday we have come to this, - that for a large number of our young girls, the potential mothers of our nation, there is no normal social or home education.' Girls placed in an appropriate institution, or whose families lived on well organised settlements were better off. Here, under the 'the powerful influences of the school and the church' they could develop into the makers of 'normal homes' with an understanding of 'inter-community relationships'.22 Rothmann discussed the arduous domestic tasks that befell women from poor families, the extent of women's work outside the homestead, the frequent lack of modern medicine or any competent help for childbirth.

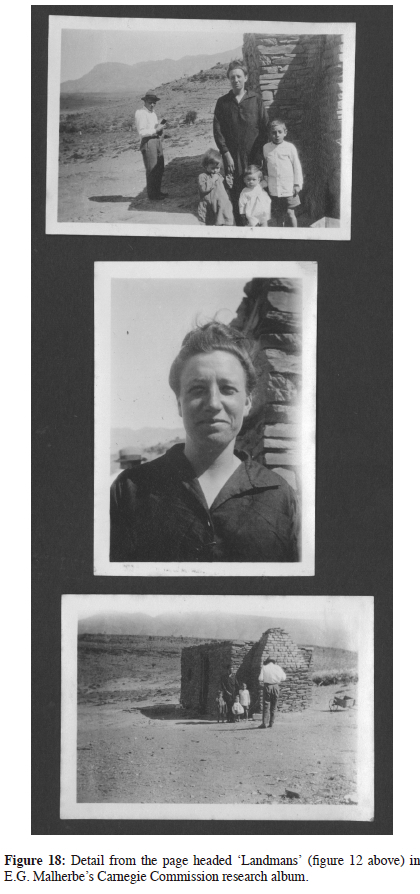

Several photographs of itinerant or poor families or of mothers and daughters illustrate this chapter. One such picture, 'Wife and children of a poor farm tenant (Karroo-farm)' shows a woman standing at the corner of a roughly built stone wall together with her three small children. Dressed in severe black, frowning into the sunlight, hers is an uncertain dignity as she faces the camera rigidly, one hand clasping the fingers of a toddler. The hard light of the semi-desert afternoon contrasts with strong shadow on skin, earth, rock. Stony veld and hills recede behind. Flanked with text discussing the destitution of 'isolated rural life', the photograph warns of the harsh results of barren surroundings upon the familial. If Rothmann's preceding chapter on poor white motherhood also involved sympathetic discussion of the difficulties of survival for poor white farmers' and sharecroppers' wives, this woman was yet presented, anonymously, as typical, and an example of the problem confronting the nation and calling for state intervention.

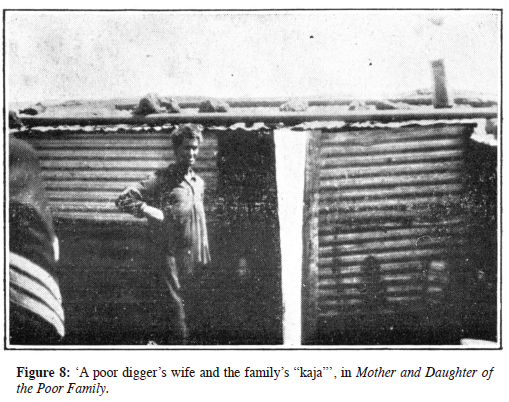

Overleaf, another photograph presented a more disturbing aspect of this problem. It shows a woman in front of a corrugated iron shack half turning towards the camera, her posture awkward, her face indistinct. In the dark doorway behind her the face of a child is just visible. The shack dominates the picture which also has what seems to be the shoulder of an anonymous (possibly uniformed) observer at the edge of the frame. In an adjacent photograph the same or similar structures are shown, dilapidated dwellings on an open stretch of land. The captions: 'A poor digger's wife and the family's "kaja"';'A "kaja" and a hut made of sacking on the diggings'.23 Read together with Rothmann's written text - including vivid descriptions of untidy and dirty young women on the diggings who seem to combine their idle days with prostitution, the picture absorbs middle-class white (for Rothmann, Afrikaner nationalist) anxieties of racial degeneration. Here, adjacent to text urging the importance of good education for daughters of the volk, surveilled by anonymous officialdom, is shown a slum-maker. Her progeny is hidden at the shadowy threshold of an impermanent dwelling referred to as a 'kaja', South African whites' colloquialism for black servants quarters or shack.24

'Hulle hou eenvoudig baie van mekaar' (they simply like each other a lot): Eugenicist explorations of poor whiteness in Malherbe's research album

As part of a well publicized report, Malherbe and Rothmann's arguments are important for our understanding of public discourse on race and poverty in the 1930s. As a text that remained in the realm of pre-publication research and study, the relationship of Malherbe's research album to the public discursive context of its time is more elusive. However, considered as a thinking space for the researcher's own perusal, or as research material organised as part of analysis towards public findings, investigation of this image-text help elucidate Malherbe's own ideas about whiteness and poverty.

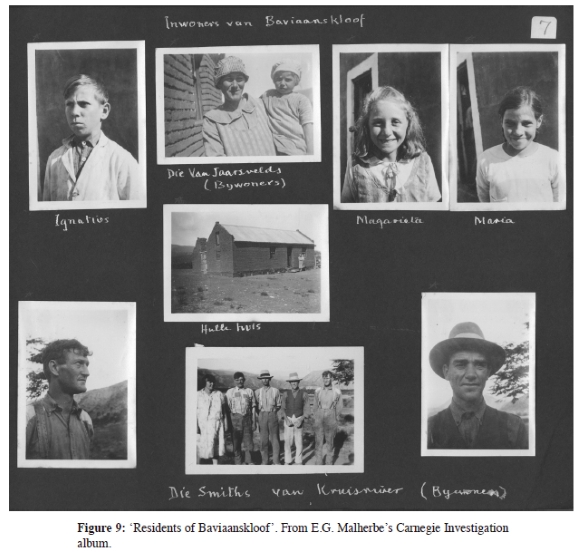

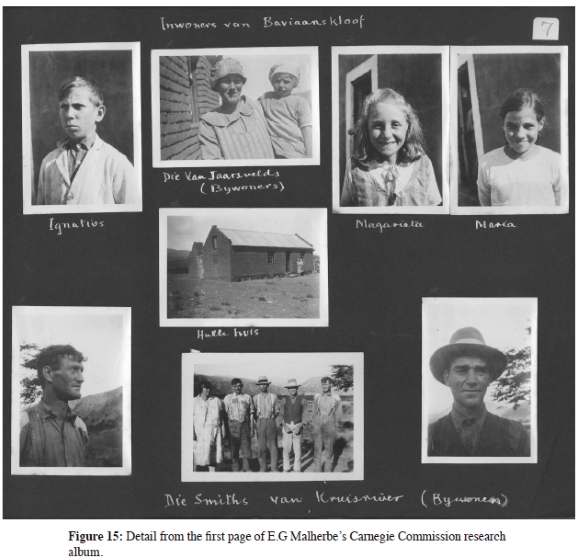

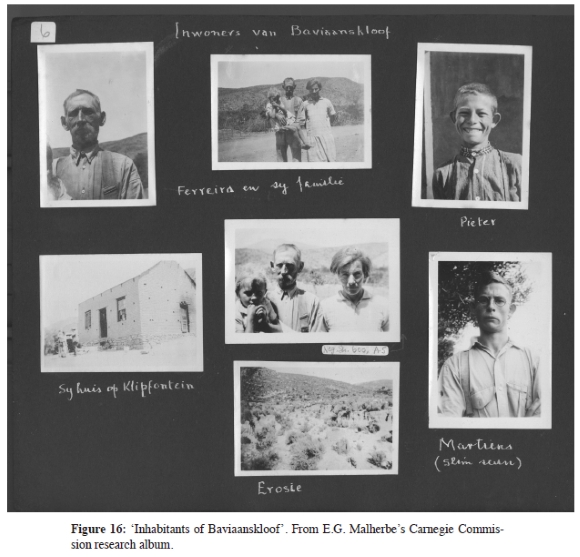

A number of pages from Malherbe' s research albums include pictures that deal with the material manifestations of poverty (for Malherbe, this often meant showing 'typical' dwellings) and that present different people classified as belonging to various economic 'types' on farms where they work as, for example sharecroppers or itinerant labourers. The three albums contain pictures from the Commission's travels through different parts of South Africa and are arranged into sections of a few pages each with pictures taken on research excursions to specific districts or towns, possibly in chronological order. As is evident from the title pages specifying an 'Armblanke ondersoek. Armblanke tipes en wonings' (Poor white investigation. Poor white types and dwellings), they were intended as a photographic record 'showing' poor whites and their living conditions, and indeed present selections of people named as 'bywoner' (sharecropper), 'trekboer' (itinerant farmer) or simply 'armblank'. An early set of pictures showing the 'Inwoners van [residents of] Baviaanskloof', a relatively remote Cape farming area, confirms Malherbe's use of the camera to methodically record the subjects of their study and the process of white, rural impoverishment. Two centrally placed pictures captioned 'Ferreira en sy familie' (Fereira and his family) show a man holding his toddler in his arms and standing with his wife. In a fashion typical of his snapshot portraiture throughout the album, Malherbe took three pictures while they stood for his attention. The first is taken from a distance so that figures and landscape are in almost equal focus with a fence and hills clearly visible. For the second he moved closer to focus on their faces; he also framed a portrait of Ferreira on his own. Another picture shows their small stone house (close attention reveals a commissioner, probably in conversation with the family). Surrounding the group portraits are also individual snapshots of young children, identified by their first names. Fereirra was probably a small farmer, for across the page Malherbe's subjects are identified specifically as bywoners. His family's ambivalent future is suggested by an over-exposed close-up of veld, captioned as 'erosie' (erosion), and the more positive adjacent portrait of 'Martiens - slim seun (clever boy)'.25

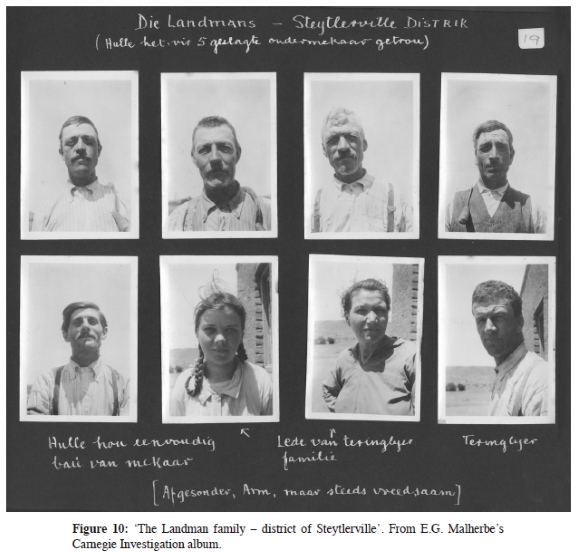

One sequence of pictures from the first album, however, is also strongly concerned with questions of race, poverty and family. These three pages of photographs, which appear towards the middle of the first album, offer opportunities for discovering more about Malherbe's intent with presentations of the familial, not least because his archival papers include associated research notes. The first of three pages devoted to one extended family show eight men and women - an overall title to the page identify them as the 'Landman' family from the district of Steytlerville. Most faced the camera squarely and all looked directly at the lens. Strong sun casts deep shadows on eyes and faces, accentuating the markings of time and climate. All are framed as head and shoulder portraits. There is a striking similarity of camera angle and posture, bleached out sky and lack of background detail - although three of the photographs show part of the same building and open veld behind them. The small prints are the same size and shape, placed in line and evenly spaced. Below the family surname Malherbe has added, in parenthesis, 'Hulle het vir 5 geslagte ondermekaar getrou' (For 5 generations they married amongst each other). One man is identified as 'Teringlyer' (TB sufferer) and arrows in ink point to two female 'Lede van teringlyer familie' (Members of TB sufferer family). Below, also bracketed, is another comment: 'Afgesonder, Arm maar steeds vreedsaam' (Isolated, Poor but still at peace.) Also, 'Hulle hou eenvouding baie van mekaar' (They simply like each other a lot).26

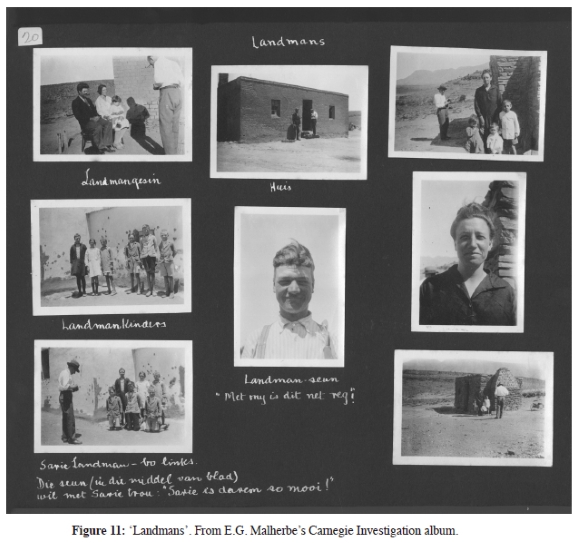

Turn the page and another eight snapshots under the heading 'Landmans' present themselves. Several of the small prints show, according to Malherbe's inscriptions, a 'Landmangesin' (Landman family) and 'Landmankinders' (Landman children) posing next to their home - a group of children also feature in a photograph usefully captioned 'Huis' (House). Two head and shoulders portraits, somewhat similar to those on the previous page, feature centre and right. But here the smiling face of a 'Landman-seun' proclaims '"Met my is dit net reg!"' ('with me things are just fine!'). Presumably Malherbe quoted him as comment on this extended family's innocently problematic, bemusing acceptance of familial intermarriage, for the same boy is recorded as having declared that he wants to marry 'Sarie Landman', a small figure in an adjacent group photograph of children in front of their school. '"Sarie is darem so mooi!"' ('Isn't Sarie just pretty!').

What are we to make of Malherbe's comments about the Landmans, their great liking for each other, their isolation and peaceable nature? That a researcher of 'poor whites' should articulate an interest in eugenics through a composite portrait arranged to emphasise family resemblance is not very surprising. In fact, soon after the conclusion of the Carnegie Commission's journeys, Malherbe (newly appointed as head of the South African Education Bureau) would frequently speak on such topics as the problem 'unbalanced fertility' and of 'quality vs. quantity' (poor people were on average less intelligent; poor, therefore less intelligent people had larger families), the relative power of social and hereditary factors on intelligence, and the merits and possibilities for birth control and of sterilising 'certified' individuals.27 His field of reference included eugenicist research from the United States, specifically Goddard's writing on the 'Kallikak' family, which claimed the persistence of congenital feeble-mindedness through generations and which also included some photographs of family members.28 However, Malherbe's jokey tone differs from the brief descriptive captions to photographs in the published volumes of the Carnegie report and contrasts to the carefully dispassionate tone of the published Carnegie volumes. The comments seem flippant, and placed as they are in parenthesis, they read almost as asides. They prompt questions as to the nature and purpose of Malherbe's juxtaposition of word and image and draw attention to the particularity of the space of album - a space with a certain assumption of privacy and shared conversation.

A foray into Malherbe's own field notebooks and associated typescript pages provide some insight and intrigue as to the dynamics of Malherbe's research on this family and the place of the photographic in his investigation. His eugenicist interest is certainly confirmed upon perusal of his research report about the Landmans, which comprise a detailed genealogy mapping out marriages between members of the extended family. They also contain more flippant remarks about the Landmans - but by members of the clan. As one informant, 'Ou Tant (Old Aunt) Johanna Landman' (neé Landman) told Malherbe: 'Hulle trou met mekaar soos Israeliete, Tot hulle soos 'n stasie aanmekaar sit. Hulle bly so een gedermte - aanmekaar' ('They marry with each other like Israelites. Until they stick together like a station. They stay together like one intestine'). But while he clearly appreciated this remark, Malherbe seems to have found little evidence that intermarriage had resulted in diminished intelligence. He rather concluded his research by emphasising social reasons for relative economic decline and that the pattern of marriage was motivated by a desire to hold on to land. For Malherbe, the 'jolly ineffectiveness' that characterised the Landmans was typical of rural dwellers unable to realize that they could no longer live the isolated and undemanding lives of their forebears. Somewhat less 'scientifically' and perhaps commenting obliquely on an apparent lack of threat to the Landman family's racial identity, he also speculated that this 'charming' and good-looking family - pale skins, the men well built, the girls with lively brown eyes - had 'an affinity of likableness about them which caused cousins to fall in love with cousins'.29

Reisalbum: snapshooting middle-class selves while researching the poor white familial

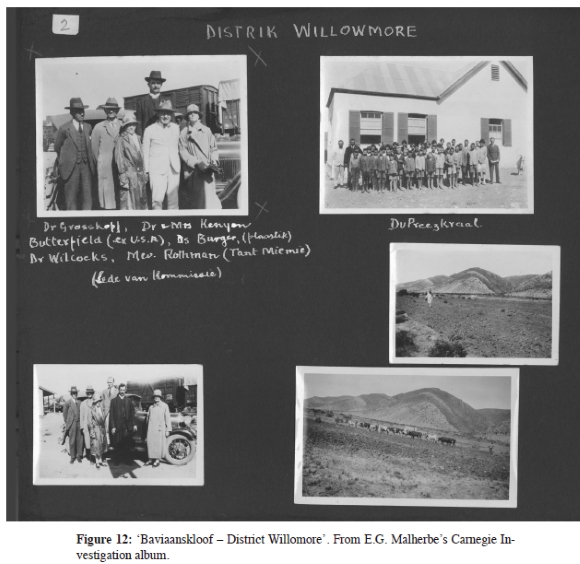

But a number of photographs from the album are suggestive of the imbrication of his social documentary mode with other aspects of popular, amateur picture-taking and of a more complex dynamic between Malherbe and his subjects. In fact, on the first page documenting this part of their research, poor whites take second place to male commissioners' pride - their touring car, one of two 1928 Fords presented to them for their travels by the Carnegie Foundation. Read from left to right, the first of ten pictures shows high mountains towering against the sky, grass and tall shrub, a stony country road. In the foreground, a stream. Behind, the focal point - a man with legs widely placed, one hand confidently, even theatrically on his hip, the other arm stretched to touch the roof of his car. The next two pictures show more familiar subjects: a head-and-shoulder shot of a man with hat and breeches and a family group standing at their doorway. But what compels the viewer is the car. Seven out of ten pictures show the car, always against the vista of mountain pass. Most enigmatically, a photograph in which the road is shown curving into the high, fading distance of bush and mountains foregrounds a slice of car at the edge of the frame. Upon more careful perusal, another pattern of repetition becomes apparent. Four pictures actually comprise the same two prints and have been pasted onto the page to create a strong measure of symmetry. Placed between such insistent and triumphant images of travel, the snapshots of people appear as if passing glimpses that are yet replete with detail - of a man with the hint of a quizzical smile on his lips, of a woman framed in her dark doorway, standing with husband and her daughters.

It is the way in which Malherbe's album combines photographs easily identified as those of the social scientist studying poor whites with other contemporary genres of snapshot photography that offer possibilities for exploring whiteness beyond the class-specific focus of many individual pictures. The numerous snapshots of the car crossing mountain passes as well as of the commissioners picnicking or swimming in rivers - placed as they are in the more private and personal space of album and combined into a single narrative with images of 'arm blankes' - involve smooth transitions between using the camera for social science and as adventurous traveller. As examples of amateur landscape photography, they are also suggestive of the commissioners' relationship with countryside and certain of its inhabitants beyond the impetus to show, scientifically, environmental degradation or generational decline.

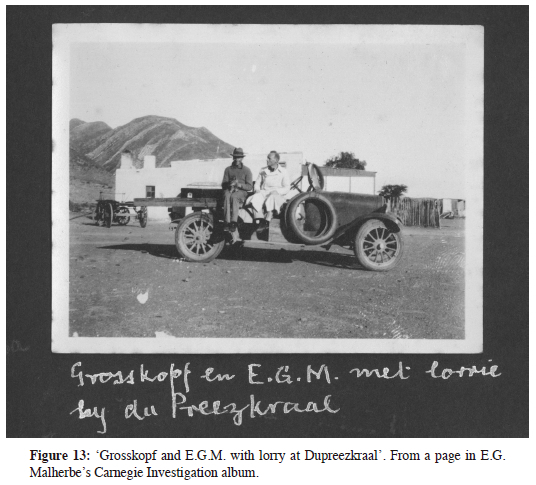

Die Huisgenoot of the late 1920s (to which Malherbe subscribed)30 featured a regular page showing the prowess of various touring cars at crossing mountains or racing trains. The magazine also published articles on 'binnelandse reise' (domestic, lit. inland travel) promoting holidays in South Africa, particularly to motorists. Considered in the context of 'Afrikaner' culture, photographs featuring men and their car, traversing the wilder spaces of the countryside, may be read as participating in a discourse of grond and platteland that claimed ownership whilst also romanticising the relationship of modern, middle-class men with land.31 Even as Carnegie commissioners identified many poor whites as problematically rural and the rural economy as an object for social scientific study, Afrikaner nationalist cultural labours involved the construction of grond as Afrikaans and belonging to the Afrikaner, and an often romanticised relationship of recently urbanised Afrikaner intellectuals with rural landscapes. In one picture on the first page of Malherbe's album (shown above), he and his colleague, the economist Grosskopf, pose sitting on a farm vehicle, with the latter holding a baby baboon or werfbobbejaan on his lap. Other photographs show, for example, the researchers picnicking in the veld or swimming in rivers.32

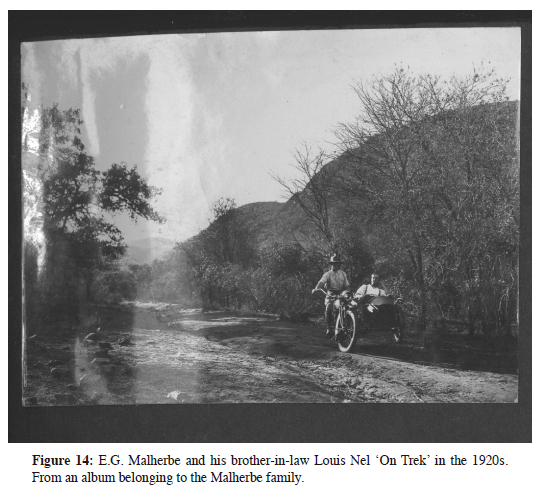

Parallels also exist between Malherbe's research albums and his family Kodak snapshot albums from the 1920s, where holiday pictures proliferate, including posturings with motor-cars as well as long sequences of landscape snapshots from an album compiled by his wife Janie - probably taken by his brother-in law, they show Malherbe and the former (as captions put it) 'on trek'. The latter was a government-employed geologist who used a motorcycle or car and an ox-wagon, presumably for his equipment.33

While these photographs of professional men combining work and leisure in the countryside comprise a more consciously aesthetic framing of landscape, both albums present the platteland as wide, empty spaces traversed by white modernity. The sequence of travel pictures from the family album include only one tiny snapshot of black workers (probably the drivers of the ox-wagon). Malherbe's landscape and travel photographs sometimes include, occasionally and often without apparent intent, the small figures of black sharecroppers or farm labourers.

But the difference of Malherbe's social scientific touring is also evident from comparison with an earlier binnelandse reis, also involving encounters with itinerant white farmers. An article on Namaqualand (a region important to Malherbe and Rothmann's Carnegie research) from 1920 represents a new genre of writing that blended modern vaderlandse travel with motifs of trek. 'Afrikaners' were told that by traveling through their 'eie land en onder [hul] eie mense' (own land and amongst their own people), they would find unparalelled enjoyment and happiness. The 'woeste eentonigheid' (wild monotony) of barren plains - territory of vaderland (fatherland) - spoke to Afrikaners in their language. Moreover, tourists would derive special pleasure from meeting fellow Afrikaners. Whether they were rich farmers or poor trekboers, the same 'wereldberoemde gasvryheid' (world-renowned hospitality) would be encountered. Photographs celebrated the semi-desert landscape and the pleasures of touring. Portraits also featured the likes of a trekboer family encountered by the travellers: poor, generous, versed in Afrikaans folklore and intent on cleanliness. In their photograph, the car's imposing fender flanks the trekkers and their tent in front of which the visitors are seated. On the right, children perch on top of a wagon, again providing a balance of old and new.34

While a similar pleasure at traversing the countryside is evident from Malherbe's album, neither this nor his published photographs make any particular effort to present rural poor - at least culturally - as 'Afrikaners'. Rothmann's research notes - not her published report - include at least one detailed personal history (and a snapshot portrait) of a respectably poor Afrikaner woman's voortrekker past - Malherbe, of course, did not espouse ethnic nationalism. That Malherbe did associate poor white with Afrikaans is evident from the way in which he only switches to English captioning right at the end of one section of the first album, where he also labels as 'poor whites' people of 'English' and 'German' descent. But while his photographs include pictures of people whose mode of dress and age made them ideal for presentation as aged voortrekkers - as had been done in Die Huisgenoot of the 1910s - these pictures were not chosen for the published volumes, nor are they provided with a cultural framing in the albums.

The Baviaanskloof sequence of pictures also suggest possibilities for more subtle analysis of the relationship between photographer and photographed - between Afrikaner researchers of white Afrikaans speakers - than do the photographs in their published form. Individual portraits of brightly smiling school children, of a relaxed-looking and simply dressed mother photographed with her child, of school groups posing with their teachers and of performances by pupils suggest a context of patronage and excitement at the arrival of important visitors. It is difficult to reconcile certain of the pictures with social scientific facticity and the hardening idea of class difference suggested by the commission's research and the pictures' use for publication. Considered individually, snapshots of young children and family groupings, with their atmosphere of informality, ease and connection between photographer and photographed, could also fit into an ordinary family album.35

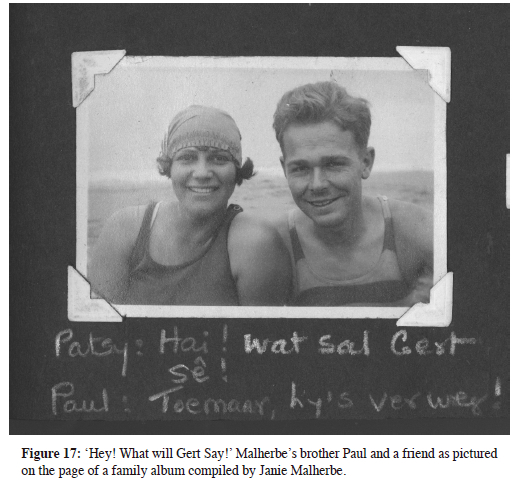

Closer attention to the characteristics of contemporary familial photographic practise clarifies some of the difference of Malherbe's Carnegie snapshooting. His own family photographs offer useful opportunities for comparison. One page of seaside holiday 'kiekies' (snapshots) from 1924 features the head and shoulders portrait of a young man and woman. Bare-armed, relaxed shoulders touching, the sea visible behind, their smiling faces seem at ease with the presence of a camera. This atmosphere of intimacy, also between photographer and subjects presents a contrast to any Carnegie pictures. The caption: '"Patsy: Hai! Wat sal Gert sê! Paul: Toemaar, hy's ver weg!"' (Patsy: Hey! What will Gert Say! Paul: Don't worry, he's far away!)36

If Malherbe was a Kodak camera man, his wife Janie was evidently the main custodian of the family snapshot albums. Her handwriting, which changed over the years, shows that they remained objects intermittently compiled, paged through and that more captions were often added much later - here, photography was certainly a 'means by which family memory' was 'continued and perpetuated'. 37 As a repository of self-representation, Malherbe's albums may have been a lasting source for memories of 'the twenties' (to quote from Janie's nostalgic captions to the earlier trek with the government geologist). Many of the holiday-like pictures of travel and camping certainly appear in his autobiography - as do pictures of poor whites.

Malherbe's research notes also refer, cryptically, to photographs, allowing for some insight into the dynamics of interaction between researcher and researched. His detailed genealogical study often included mention of 'kiekies' next to the names of family members (and, in the case of some children, the results they had achieved in his tests). The negatives of many more photographs than those placed in the album show a slightly larger but unsurprising array of framings and poses. But notes on his conversations with photographic subjects suggest that some participated in picture-taking with a measure of assertiveness. Portraits of elderly couples probably include one of Tant Hannie who (according to Malherbe) had insisted that she would not be pictured 'sonder haar ou man' (without her old man). Tant Hannie had also disconcerted the researchers by offering them coffee without sugar and telling them that the teaspoons were 'om die vliee uit te skep' (for scooping out the flies).38

More interesting is the fact of two letters from school teachers thanking Malherbe for 'die kiekies' and promising to identify the children pictured. 'Ek sal die kiekies veilig besorg' (I will safely deliver the snapshots) to the homes of 'Mnr Jan Piet Landman en Mnr Edward Landman' added one.39 We have no access to the portraits that commissioners observed in the homes of their subjects of study. However and surprisingly of photographs comprising a typology of poor whites, Malherbe's snapshots may well have augmented a collection of Landman family photographs. This incongruity of a gesture more easily associated with practices of personal and familial photography hints at the inadequacy of any neat categorisation of this album as social documentary. Malherbe's diaries of the late 1920s contain regular notes about 'kiekies' - of a wedding party, of his small son - posted to relatives and friends.40 Were those sent to the Landmans an extension of this habit? What does this suggest about this amateur photographer's interaction with his subjects?

Malherbe and his wife's numerous personal photographs from the 1910s and 1920s are some examples of how the idea of the camera as 'instrument of ... togetherness' and the snapshot as displaying family cohesion41 was absorbed by white, middle-class South Africans. Writing about the 'coded and conventional nature of family photographs' and relational construction of 'familial subjectivity', Hirsch has emphasised that 'multiple looks' circulate in their production and reading. The 'dominant ideology of the family ... superposes itself as an overlay over our more located, mutual, vulnerable individual looks.'42 If the visual interactions involved in Malherbe's Carnegie photography were sometimes structured by networks of paternalism or patronage, close attention to specific photographs in the albums show another dynamic at work. For example, the photograph printed in Rothmann's volume of the woman with her three children also appears in the sequence of Landman photographs, but uncropped, so that the figure of a man with hat, a white shirt and neat trousers is visible where he stands at a small distance from the assembled family. Discussing the importance of looking beyond the 'obvious characteristics' of a photograph', Edwards suggests the value of scrutinising not merely 'the detail of content but the whole performative qualtity of the image'.43 An urbane presence in this bare landscape, the man seems intent on a small notebook, and is sometimes pictured writing in it. It is not he who is on display. But once noticed, he seems to dominate the page. His multiple presence in adjacent snapshots create the impression of a figure (always partly intent on his hands) circling the small groups of people who stand facing him, or turned away from him, always at some distance. In some of the snapshots he is shown from the back - his stance suggests that his recording device could well be a box camera. It is difficult to discern details of his face on the small prints, but this was certainly member of the Carnegie research team, photographed in action. As framings not only of armblanke subjects but of research in progress, the photographs include the researcher investigating his subjects and confront us with the intrusiveness of the social scientific gaze.44

For Afrikaner nationalists as for many others, the construction of imagined communities across time and space included taking, looking at and writing about photographs. Malherbe - believer in the unambiguous potency of facts - used the camera as straightforward mechanism for recording appearances. Of course, photographic indexicality itself provides possibilities for the subversion and frustration of such assumptions. Sharp details reflected onto film presented individual likenesses to readers of the published report and to whoever might have perused the albums. Because his Carnegie photographs appear to share in some of the conventions of snapshot and personal photography (as his film caught 'the happy smile' or physical gestures of affection between parents and children), the photographs may have worked to engage viewers with familiar signs of the familial and to offer possibilities for imagined recognition. However, and contradictorily, the systematic, visual construction of typologies of similitude emphasised 'otherness'.

Conclusion

That a South African sociologist used the technology of still photography as part of his effort to collect 'new facts' and for a racially exclusive project that sought to explain and find solutions to 'white' poverty is, in itself, hardly surprising. But Malherbe did so at a time when applied social science was being established as a 'scientific' enterprise with relevance for state policy, and during a period of shifting ideas about how and why researchers should 'show' race and poverty through photography. The late nineteenth and early twentieth century classificatory project of photographing black 'races' involved a focus on physical bodies very different from Malherbe's own systematic classification of poor whites according to economic 'type'. Even as the Carnegie report was published, the old racial anthropology was retreating before new research practices by Schapera and other social anthropologists who now used cameras for their pictures of contemporary African cultural practice.45

I have argued that Malherbe used the camera's indexical capacity and the commonly held belief in its capacity for truth telling in ways that differed significantly from those of earlier photographers who also pictured people as white and as economically marginalised. This article has, in large part, focused on the internal logic of how Malherbe used words and images in order to explain white poverty, and has begun to look at how he did so in order to imagine whiteness. More extensive work on the albums and published photographs considered within a broader spectrum of South African social scientific research could pay more detailed attention to the relationship of these photographs to the shifting practices of photography involved in the articulation of blackness and the conceptualisation of black poverty. As one example, Hellmann used her camera to document the lives of black urban poor when she embarked upon her Rooiyard research in 1933 - with very different ideas of what visual note-taking should involve, and a very different understanding of the socio-economics of raced impoverishment.46

Understanding the intricacies of a visual economy, the ways in which photographic meanings were (are) made across space and time, also demands attention to the porousness of any seemingly specific visual genre and to the fluidity and multiplicity of contemporary conventions that may structure any one photographic project and its imagetext. Malherbe's snapshooting of poor white subjects sometimes seems to have participated in the conventions of family photography, even as pictures also suggest how the researchers drew upon networks of paternalism, their imbrication into local hierarchies and shared cultural context, and how the new conventions of socio-economic research cut across these more familiar ways of interaction. Many of the pictures of platteland travel and landscape could also be understood as expressive of the imagined identities of middle-class academics and themselves.

This article began to map out how visual representations of 'poor white' shifted over time and were variously articulated in different South African discursive contexts. I have explored authorial intentionality and the arguments that Malherbe and his co-author Rothmann made about the causes of white poverty via discussion of the relationships between image and written text. I considered how conventional understandings of the photographic image and its documentary status were put to use by this photographer. But as Gilian Rose reminds us, photography, 'perhaps more than any other visual text ... persistently exceed the discursive'.47 A more complete exploration of the historicity of these pictures would consider this aspect of photographs, a comparative framework beyond pictures of poverty taken in South Africa, and the layering of meanings made possible since their production in 1929.

1 E.G. Malherbe, Education and the Poor White, Volume III, v. Here I quote from the section 'Joint Findings and Recommendations of the Commission' which is not specifically attributed to Malherbe. Indeed, it is reproduced in several volumes of the Report.

2 E.G. Malherbe, Education and the Poor White, Volume III, 8. I still have to determine whether this was indeed an innovation by Carnegie commissioners, or whether earlier South African commissions of inquiry also embarked on research 'in the field'.

3 Godby, 'The Evolution of Photography in South Africa as shown in a comparison between the Carnegie Inquiries into Poverty (1932 and 1984)' in J-E. Lundstrom and K. Pierre (eds), Democracy's Images: Photography and Visual Art After Apartheid (Uppsala, 1999), 34-36.

4 See also M. du Toit, 'Blank Verbeeld, or The Incredible Whiteness of Being: Amateur Photography and Afrikaner Nationalist Historical Narrative', Kronos, vol. 27, Nov. 2001, pp77-113 and 'The General View and Beyond: From Slum-yard to Township in Ellen Hellmann's Photographs of Women and the African Familial in the 1930s', Gender And History, vol.17(3), Nov. 2005, pp.593-626.

5 S. Gaule, 'Poor White, White Poor: Meanings in the Differences of Whiteness', History of Photography, vol. 25(4), 2001, 7.

6 E.G. Malherbe Manuscript Collection, File 845, packet D.

7 Malherbe studied at Columbia University before departments of sociology were established at South African universities. See S. Ally et al, 'The State Sponsored and Centralised Institutionalisation of an Academic Discipline: Sociology in South Africa, 1920-1970', seminar presented at Wits Institute for Economic Research on 7 April 2004, www.wiserweb.wits.ac.za. The authors identify the Carnegie Corporation-sponsored investigation as an important impetus towards the establishment of sociology at South African universities. Charles W. Coulter, one of two American sociologists to visit South Africa as part of the investigation, bolstered initiatives to establish sociology as a discipline involved in the training of social workers in South Africa. The University of Pretoria was the first to establish a department of sociology in 1931. (Alley et al, p. 5, drawing on R.B. Miller, 'Science and Society in the Early Career of H.F. Verwoerd', Journal of Southern African Studies, vol. 19 (4) 1993.

8 EG Malherbe Collection, File 844, KCM 57022, Album of photographs for the Carnegie Investigation, 1929, 22.

9 E. Edwards, Raw Histories: Photographs, Anthropology and Museums (Oxford: Berg Press, 2002), 8.

10 However, Sally Gaule notes that Malherbe already articulated his interest in the 'Poor White Problem' whilst studying in the United States during the 1920s. Moreover, the designer of the FSA's photography project Stryker's 'interest in photography is similarly traced to Columbia University in the 1920s'. She speculates that that 'links between the reform strategies of the Carnegie Commission in South Africa and the FSA in the USA may have originated at Columbia during this time'. ('Poor White, White Poor: Meanings in the Differences of Whiteness', 339)

11 D. Price, 'Surveyers and Surveyed', in L. Wells (ed), Photography: A Critical Introduction (London: Routledge 2001), 96.

12 National Library of South Africa, Cape Town, F.E. Nicholls Album, Album 9.

13 S.A. National Library, Cape Town, C. A. Nicolson Album, Album 8.

14 M. du Toit, 'Blank Verbeeld', pp 77-113.

15 M. Hirsch, Family Frames: Photography, Narrative and Postmemory (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1997), 6.

16 I discuss this and other similar photographs in Blank Verbeeld, or The Incredible Whiteness of Being: Amateur Photography and Afrikaner Nationalist Historical Narrative'.

17 Social and Industrial Review, November 1929.

18 R.W. Wilcocks, Psychological Report: The Poor White, Vol. III, 2.

19 E.G. Malherbe, Education and the Poor White, 202. Malherbe explains that by 'retardation' he means 'slow progress in scholastic work - irrespective of causes' and that lack of intelligence is only one possible cause of retardation (145).

20 Rothmann also comments that she 'had no reason to think that' fathers and sons had a more developed 'idea of social relationships', but that her study focused on women.

21 Rothmann, The Mother and Daughter of the Poor Family, 170.

22 Ibid, 198-9.

23 The details of the child's face and stripes on the uniformed shoulder are clearer in the original print as available in Malherbe's album.

24 'Kaja' is derived from 'ikhaya' the word for house or home in Nguni languages. Malherbe uses an Afrikaans-inflected spelling. In parts of South Africa white South Africans still refer to black servants' quarters as 'khayas'.

25 EG Malherbe Collection, File 844, KCM 57022, Album of photographs for the Carnegie Investigation, 1929, 6.

26 EG Malherbe Collection, File 844, KCM 57022, Album of photographs for the Carnegie Investigation, 1929,19-20.

27 E.G. Malherbe Manuscript Collection, KCM 56979 (240) File 477/4. In a presentation to the Dutch Reformed Synod where he argued for their approval of voluntary birth control (excluding abortion), Malherbe also suggested sterilisation of 'ge-sertifiseerde persone wat nie algeheel gesegregeer kan word nie' (certified persons who cannot be altogether segregated').

28 Goddard infamously altered pictures of family members in order to emphasise supposed traits of feeble-mindedness and criminality. Another prominent early twentieth century eugenicist, Arthur Estabrook, also compiled at least one photographic album of his research subjects although he decided not to use photographs in his published work because of perceived shamefulness of being identified with a eugenic study.

29 E.G. Malherbe Manuscript Collection, KCM 56979 (200) file 476/21.

30 E.G. Malherbe Manuscript collection, note in diary, 1928. KCM 56985 (33) File 568/2.

31 See A. Coetzee, 'n Hele Os vir 'n ou Broodmes: Grond en die Plaasnarratief sedert 1595 (Cape Town, 2000) for an exploration of the Afrikaans 'plaasroman' (farm novel) as point of entry into a fascinating discussion of Afrikaner identity and a discourse of grond (roughly, soil/ground/earth) within the broader context of South Africa's colonial history of land dispossession.

32 EG Malherbe Collection, File 844, KCM 57022, Album of photographs for the Carnegie Investigation, 1929, 3.

33 EG Malherbe Collection, File 392, KCM 56960, 'E.G.M. and Janie - varia with Relations and Friends', 11. The photographs appear in a section of an album of family photographs headed "A geologist (Dr L T Nel) treks".

34 Die Huisgenoot, September 1920.

35 EG Malherbe Collection, File 844, KCM 57022, Album of photographs for the Carnegie Investigation, 1929, 7.

36 EG Malherbe Collection, File 392, KCM 56960, 'E.G.M. and Janie - varia with Relations and Friends', 35.

37 M. Hirsch, Family Frames, 6-7.

38 Ibid.

39 Ibid.

40 EGM, Diary for 1928, KCM 56985 (33) File 568/2.

41 M. Hirsch, Family Frames, 7.

42 Ibid, 11.

43 E. Edwards, Raw Histories, 2.

44 EG Malherbe Collection, File 844, KCM 57022, Album of photographs for the Carnegie Investigation, 1929, 20.

45 M.du Toit, 'The General View and Beyond: From Slum-yard to Township in Ellen Hellmann's Photographs of Women and the African Familial in the 1930s', 601

46 See M.du Toit, 'The General View and Beyond: From Slum-yard to Township in Ellen Hellmann's Photographs of Women and the African Familial in the 1930s'.

47 G. Rose, 'Engendering the Slum: Photography in East London in the 1930s', Gender, Place and Culture, vol. 4, 1997, 13.