Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Kronos

versão On-line ISSN 2309-9585

versão impressa ISSN 0259-0190

Kronos vol.32 no.1 Cape Town 2006

ARTICLES

Confronting Horror: Emily Hobhouse and the Concentration Camp Photographs of the South African War

Michael Godby

Department of Historical Studies, University of Cape Town

In 2003 the War Museum of the Boer Republics in Bloemfontein published a selection of photographs from its holdings on the South African War of 1899-1902 under the title Suffering of War.2 Although most of the images depict the suffering of Boer subjects in the unequal war between Great Britain and the Boer States of the South African Republic (subsequently, the Transvaal) and the Orange Free State (Rebpublic), the text of the book reads as a condemnation of war in general. In this sense, Suffering of War forms the latest chapter in the evolution of the war in South African political consciousness that Albert Grundlingh has traced over the past century.3 Grundlingh shows that, despite the trauma of the war and its obvious resonance in historical memory, only nine books on it were published before 1931. As the tide of Afrikaner Nationalism rose in the 1930s and 1940s, however, many books were written to celebrate the exploits of Boer commandos and generals, on the one hand, and condemn the British treatment of the civilian population, on the other. Subsequently, as the victorious Nationalist movement sought to rally English-speaking support against a presumed common Black enemy, little attention was paid to the War as a defining moment in Afrikaner history. The occasion of the centenary of the War in the new dispensation of a liberated South Africa, however, has encouraged scholars to examine the War as it affected the entire population of the subcontinent - for which reason it is now generally referred to as the South African War rather than its traditional name of the Anglo-Boer War. However, if these changes in historical perspective have allowed the history of the War to be examined with increasing critical rigour, it has to be said that the same is not true of the photographs of the War, especially the photographs of concentration camp victims. Like other historical photographs, pictures of the South African War are routinely reproduced in altered format, with incomplete or altered caption information, and no apparent concern for their authorship, original circulation, or function. Moreover, the concentration camp photographs in particular have been made to work as propaganda, which, almost by definition, purposefully excludes the possibility of a critical reading of the images.

The concentration camp photographs of the South African War have lent themselves to polemical arguments because the first response they elicit is, of course, to side with those they represent and condemn those responsible for the conditions they depict. This partisan reading of war photography has become something of a habit in recent times because, as Susan Sontag points out, whatever its role before the mid-century, after the Vietnam War 'war photography became, normatively, a criticism of war'.4 Indeed, so persuasive are these images that they tend to make a critical response seem inappropriate, even inadequate. Their very power tends to preclude any complex reading of the images that would involve an understanding of their history and context. As Sontag puts it: 'The problem is not that people remember through photographs, but that they remember only the photographs. This remembering through photographs eclipses other forms of understanding and memory.'5

The restitution of an historical context for the concentration camp photographs of the South African War is fraught not only because of their obvious power but also because of the dreadful semantic connection between these camps and the concentration camps of the Second World War: When the British Ambassador to Berlin protested about the German use of concentration camps, Hermann Goering responded by quoting from an encyclopaedia, 'First used by the British in the South African War'.6 Although the history of these two sets of camps is very different, it is inevitable that some of the horror of the Holocaust attaches to any account of the original concentration camps, and the photographs of them. For all these reasons it has proved extremely difficult to discuss or even present these photographs with any degree of critical distance.

Concentration Camp Photographs: Private and Public Meanings

In an attempt to establish the appropriate historical context for these images, this article will draw on the letters of Emily Hobhouse, who was perhaps the most vociferous British opponent of the War. As we shall see, Hobhouse herself learned to use photographs to strengthen her arguments but her letters provide valuable evidence as to how photographs were actually made in the camps. For example, Hobhouse commented on funerary practices in the camps, in which photography played a part:

I hate mourning myself (she wrote to Leonard Hobhouse from Kimberley on 13 March 1901), but the Boers are like our Cornish folk in the importance they attach to black clothes; so I understand their feeling exactly. Cornish women would spend their last shilling on a piece of crape. So Mrs Louw's mourning will be a present from England.7

In the same letter she records having been called into Mrs Louw's tent to see her three-month old baby laid out 'with a white flower in its wee hand'. Soon after, two more of Mrs Louw's children died and were prepared for burial and Hobhouse returned to the tent:

I found all three little corpses being photographed for the absent father to see some day. Two little wee white coffins and a third wanted. I was glad to see them, for at Springfontein a young woman had to be buried in a sack and it hurt their feelings woefully.8

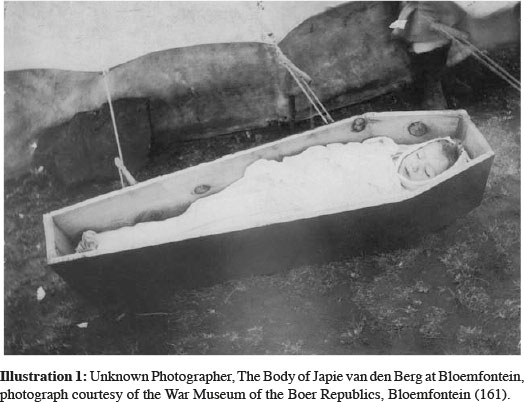

As a cosmopolitan Liberal, Hobhouse seems not to have entirely approved of the mortuary practices she was witnessing.9 But the preparation of the dead for burial, and the photographic recording of the prepared body - finally to 'secure the shadow ere the substance fade' - had been widespread in the photographic world in the second half of the nineteenth century.10 The photographs that Hobhouse saw being taken in Kimberley are not known to have survived. Her comments on this occasion could apply also to several of the photographs preserved in Bloemfontein and published in Suffering of War (Illustration 1). Significantly, when the Commission of Ladies that was appointed by the War Office to check on Hobhouse's findings visited Bloemfontein in September 1901, they referred to 'photographs shown by women in camp of their dead children' to confirm that corpses were being 'properly shrouded and coffined'.11

These reports from the time confirm that funerary photographs were intended for private circulation. In such use, as Christraud Geary has shown, the meaning of the photograph is controlled by the fact that the subject will be known to or be part of the same circle as the viewer.12 By contrast, the subject of a public image will not be known personally to the viewer and so will tend to communicate on a symbolic, rather than individual level. Moreover, under certain conditions, such as the passing of time, images that originally had private currency may acquire public significance. Thus the funerary portraits from the South African War have been used for many years to stress the appalling mortality rates in the camps when their original purpose, evidently, was to console the family of the deceased. On a different level, at a time of traumatic displacement, these photographs can also be seen as attempts to consolidate the idea of the family structure.

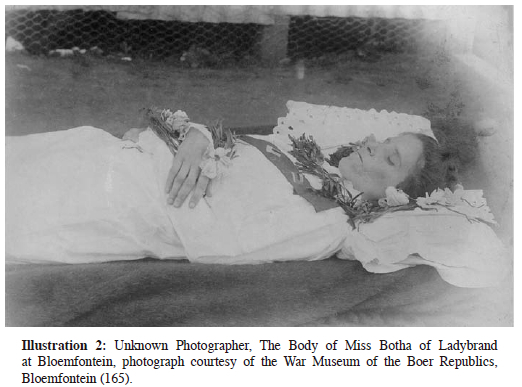

Paradoxically, the private nature of these funerary portraits might not entirely exclude an original polemical purpose. A photograph in the War Museum of the Boer Republics simply identified as 'Miss Botha of Ladybrand', who died at Bloemfontein at the age of 18, shows the body prepared for burial with flowers and, across her chest, a ribbon decorated with the Vierkleur - or four-colour flag - of the South African Republic (Illustration 2): according to the caption in Suffering of War (165), Miss Botha specifically requested that such a photograph be sent to her father who was a prisoner of war in Ceylon. In March 1901 Hobhouse reported that three girls in the Norvals Pont camp had their furniture confiscated simply for singing the Free State anthem, so this display of the flag represented a significant private statement of defiance.13

According to the War Museum, Miss Botha's photograph is unattributed but could be by any one of three photographers working at that time in Bloemfontein.14Whoever was responsible, this photograph and other funerary photographs taken in the same camp are clearly professional creations. At first sight it might seem inconceivable that a bereaved family in the appalling conditions of a concentration camp should go to the trouble, and the expense, of having a photographer visit the camp to make these funerary records. The fact that they did so suggests both a remarkable continuity in certain commercial transactions in the camps, and the immense importance to the inmates of family relationships. Other subjects that express the importance of family structures at this time, obviously, are photographs of children and family groups.

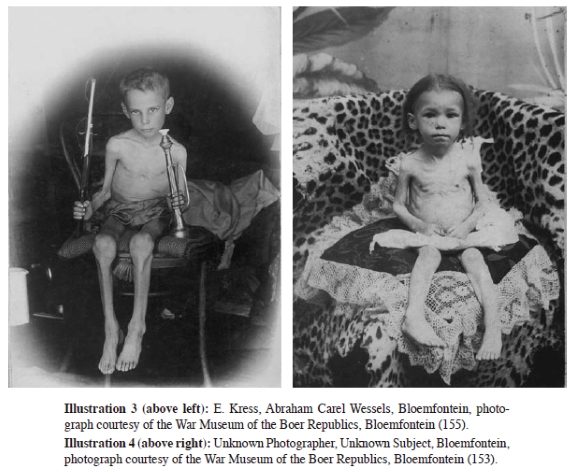

Two photographs preserved in the War Museum at Bloemfontein of the young Abraham Carel Wessels may be considered in this light (Illustration 3). The decision to photograph the boy in both full-face and profile views was obviously made to best show the emaciated state of his body. But the elaborate lighting and stylish vignetting of these photographs indicate that they were made by a professional photographer, who can now be identified as E. Kress from Bloemfontein, and they were surely commissioned by the boy's family: they were donated by the family to the War Museum in the 1950s.15 In other words, the photographs were taken for private rather than propaganda purposes. Perhaps the family feared that the boy would soon die and they had the photographs taken in anticipation. In the event he survived at least to a healthy middle age. But they certainly were concerned to record his courage. In the context of a concentration camp of women and children whose menfolk were either away on commando or in prisoner of war camps, the boy's toy gun and trumpet surely signal, albeit privately, a determination to support the continuation of the war. Many commentators noted that the camps provided immense moral support for the commandos, a support, moreover, that hardened as the suffering in the camps increased.16 The implicit defiance of these images seems almost to illustrate Emily Hobhouse's words at the unveiling of the Women's Monument in Bloemfontein in 1913:

Daily in that camp, as later in others, I moved from tent to tent, witness of untold sufferings, yet marvelling ever at the lofty spirit which animated the Childhood as well as the Motherhood of your land. So quickly does suffering educate, that even children of quite tender years shared the spirit of the struggle, and sick, hungry, naked or dying prayed ever for 'no surrender'.17

This must be the meaning also of the extraordinary photograph of the emaciated little girl seated on a lace cushion and leopard-skin (Illustration 4).18 These studio props and the painted backdrop determine that whatever polemical purpose it may have served subsequently, the photograph was commissioned by a family that took their beloved daughter, almost certainly out of the camp and into the town to a professional establishment in order to have this formal portrait made. This photograph, in other words, is also essentially a private record of kinship, suffering and determination.

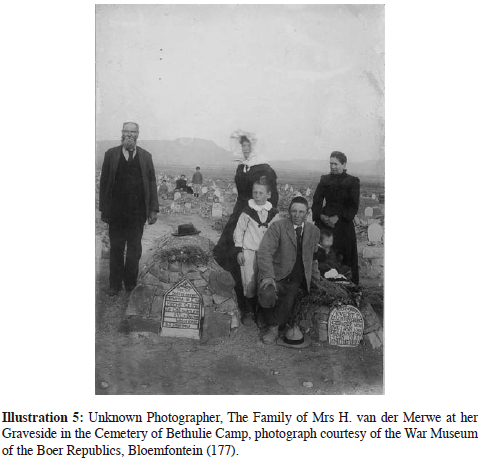

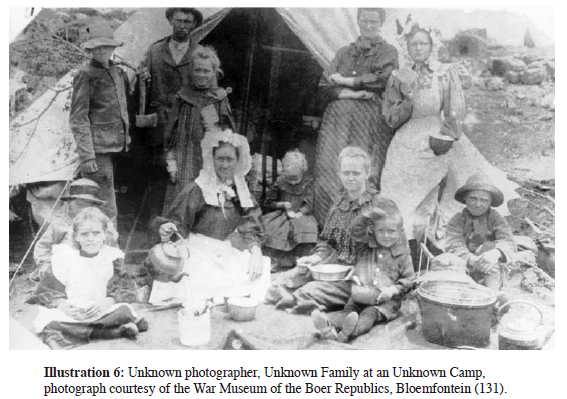

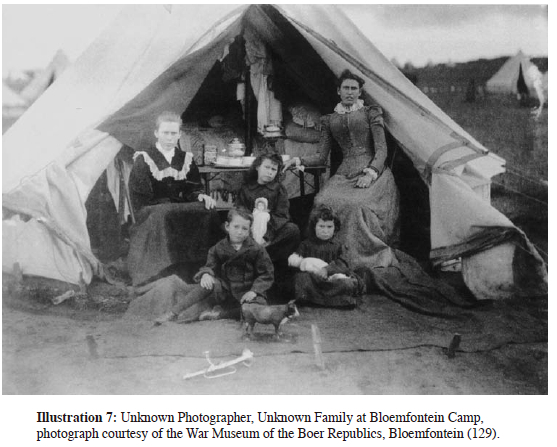

The many photographs from the camps of actual family groups are more difficult to interpret, mainly because too little is known of their commissioning circumstances. One distinct form of family photograph at this time is the group at the graveside of a deceased relative (Illustration 5). This type of photograph obviously combines the ideas of preserving the memory of a loved one with the importance of the family structure. Many other family photographs portray groups outside their tent ostentatiously displaying their possessions and, often, apparently enjoying tea (Illustrations 6 and 7).

These pictures are sometimes interpreted as British propaganda images designed to reassure a critical world that conditions in the camps were acceptable.19 But this view, of course, presupposes that the photographs were initiated by the British authorities and that the inmates meekly complied with their wishes. It seems more likely that the photographs were commissioned by the families themselves with the purpose of reassuring their absent menfolk. British officials, incidentally, commented that the Boers were inordinately fond of their families. The patently awkward poses and gestures would reflect the people's lack of familiarity with the photographic process and their readiness to obey the instructions of the professional they had hired. Moreover, on the example of the photographs of the young Wessels, it might be possible to attribute symbolic significance to objects such as trumpets that are prominently placed in the foreground of some pictures. If indeed these photographs were made to reassure absent husbands and fathers of the welfare of their families, it is probably significant that chief amongst the artifacts made by prisoners of war were elaborately embellished picture frames. Like any other photograph, however, once these family groups had been removed from their original private circulation, they could be used for very different purposes.

Lizzie van Zyl

This article has been concerned to reconstruct the original private circulation of important photographs of the concentration camps of the South African War and to distinguish this function from the propaganda purpose for which many were later appropriated. But photographs were taken during the war for immediate propaganda purposes, both in the camps and, even, on the battlefield.20 The cause of the war was fiercely disputed in England and elsewhere and photographs, amongst other graphic media, were used on both sides of the argument. On the one side, British officials occasionally had photographs taken of different aspects of the camps - for example, the lay-out of the camp, the hospital, groups of school-children, etc. - that they would attach to reports to their headquarters in South Africa or London to reassure their superiors that the camps were being conducted well:21these photographs are generally amateur productions that seem to have been reserved for closed circulation in government offices. But, on the other side, campaigners against the war were concerned to reach as wide a readership as possible, and they seem deliberately to have sought out the most powerful images in order to convince the public of the horrific conditions in the camps and so the urgent need to bring the war to an end.

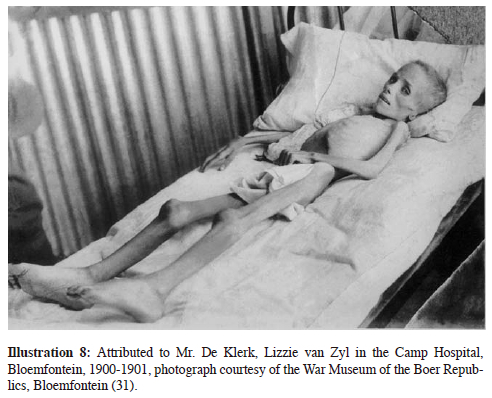

As the war dragged on and conditions in the camps deteriorated, one photograph in particular came to represent the humanitarian disaster of the British refugee policy - and this image was contested as fiercely as the cause of the war itself (Illustration 8). The significance of the photograph of Lizzie van Zyl turns largely on the date it was made in relation to the time in November 1900 when Lizzie and her family were confined in Bloemfontein camp. The closer these dates, the more likely it is that she entered the camp in the emaciated state that is shown in the photograph, while the further apart, the more fully her condition could be blamed on the British authorities. As to the commissioning circumstances of the image, comparison with the images of Abraham Wessels (Illustration 3) and the little girl on the leopard skin (Illustration 4) suggests strongly that it was not made as a portrait for Lizzie's mother who, anyway, is recorded to have been too poor to afford the luxury of a photograph. On the contrary, the hospital setting, indicated by the corrugated iron wall in the background, and the awkward view of the child's body suggest that the photograph was originally intended for purposes of evidence in a public, rather than private sphere. In fact, in 1902, Arthur Conan Doyle maintained that the photograph was taken in support of criminal proceedings against Mrs van Zyl for neglect of her child.22 But this argument was soon exposed as a vain effort to limit the damage the photograph was doing in the growing propaganda campaign against the war.

Emily Hobhouse discussed her involvement with the photograph and its subject once it had been widely published, both in correspondence with the London press and in her book The Brunt of the War.23 From these accounts it is clear that she was not responsible for having the photograph made, nor for its first use in the public sphere. Hobhouse had given Lizzie the doll that appears in the photograph and she records that she collected the photograph out of fondness for the child. However, she appears to have sent the picture to her family in England, who were actively campaigning against the war, in late January or February 1901, with other 'cases' 'which might appeal to the conscience of the country to let these innocent people go free'.24 Significantly, the Committee of the Distress Fund for South African Women and Children in London did not use the photograph, perhaps out of respect for its subject, perhaps because of the equivocal nature of its evidence. With the passing of time, however, especially after Lizzie's death probably in May 1901, the private significance of the photograph was eclipsed by its symbolic potential. On 27 June, the New Age: Weekly Review of Politics, Literature and Art, that was sympathetic to Hobhouse's cause, published the photograph as a generic statement on the suffering of war. But the floodgates really opened in January 1902 when the pro-Government press published the image in the form of a line drawing together with a caption derived from Hobhouse's annotation on the original photograph to the effect that 'the food does not suit them and the great heat of the tents'.25 The point of the publication, evidently, was to discredit Hobhouse, who by this time was the most vociferous critic of the war, for appearing to use propaganda in her campaign.

In her response to the Westminster Gazette on 27 January 1902, Hobhouse was at pains both to distance herself from any propaganda use of the photograph and to debunk the explanation of Lizzie's condition in the photograph as being the result of her mother's neglect.26 As early as March 1902, however, these subtleties became irrelevant as, on the one side, continental campaigners against the war bombarded British politicians and others with reproductions of the photograph; and, on the other, Joseph Chamberlain, the Colonial Secretary, declared bluntly to the House of Commons that the photograph showed Lizzie at the time she entered the camp.27 Later that year, Hobhouse herself decided to use the photograph in The Brunt of the War, but was prevented from doing so by her publishers as it was 'too painful for reproduction'.28 As she commented in a footnote: 'This raises the question how far it is right to shrink from a typical reproduction, however distressing, of suffering which others have to endure, and which has been brought about by a sequence of events for which we are partly responsible.'

Emily Hobhouse and Visual Imagery

Emily Hobhouse began to acquire photographs during her time in the camps from a mixture of motives, from affection for the subject, in the case of Lizzie van Zyl, and to 'appeal to the conscience' of England in terms of her general campaign. She was certainly sensitive to visual form and often given to striking visual imagery. For example, she described her reaction to a group of refugees at Springfontein Railway Station on 1 May 1901 (that she later persuaded Anton von Wouw to use as his main sculptural group on the Women's Monument in Bloemfontein): 'their condition beggars description: the picture photographed on my mind can never fade.'29 She was intuitively aware also of the rhetorical value of the visual image. In her Report of a Visit to the Camps (1901), Hobhouse wrote: 'If only the English people would try to exercise a little imagination - picture the whole miserable scene. Entire villages and districts rooted up and dumped in a strange, bare place.'30 But, as her own publishers' refusal to use the photograph of Lizzie van Zyl makes clear, there were constraints in the use of polemical material; and Hobhouse, of course, had no experience of this sort.

In a letter from Bloemfontein dated 25 February 1901, Hobhouse gave a unique, and tantalizing, description of how she collected photographs in the field:

I am sending some camp photographs. There is a photographer there, amongst other professions. The people are rigged out in 'their only clothes' and have bundles of bush which they go to cut on the kopje in the morning. Of the Geldenhuys family the mother and two children have since had typhoid and two of the other children a horrid affection of the eyes to which many have been subject.31

The photographer she refers to here is likely to be the same Mr. de Klerk to whom elsewhere she attributes the photograph of Lizzie van Zyl but who is now clearly identified as a camp inmate himself.32 Although her text is not entirely clear at this point, Hobhouse seems to be describing a single photograph which appears to have been a group portrait of the Geldenhuys and another family. In fact, the unusual detail of the 'bundles of bush' might allow one to identify this photograph with Illustration 6, although Hobhouse is not known to have used this image herself, nor is there any documentation attached to the photograph in the War Museum.33 Be that as it may, this account suggests that Hobhouse collected copies of existing photographs, in this case apparently a commissioned group portrait, rather than commissioning them herself. But her determination to correct the overly positive image of the photograph by supplying an account of the typhoid and 'horrid affection of the eyes' since suffered by members of the Geldenhuys family foreshadows the difficulties she experienced in having her illustrations in The Brunt of the War communicate as she wanted them to.

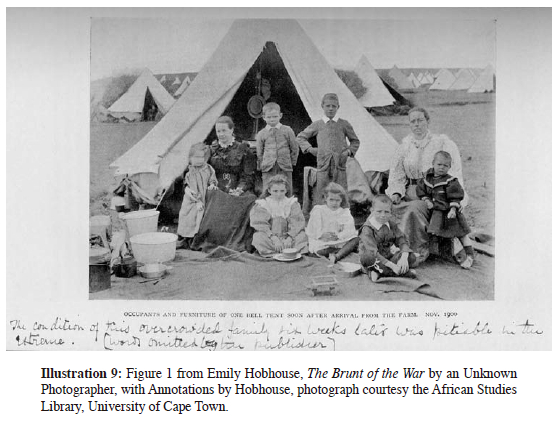

There are nine photographs reproduced in The Brunt of the War. Of these, four illustrations - Figure 2: 'Camp Huts. 1901', Figure 7: 'School Children at Irene. Nov. 1901', Figure 8: 'Cooking in Camp. 1901', and Figure 9: 'A Camp Garden bordered with milk tins' - evidently depict everyday life in the camps. The people who took these photographs are not identified. Perhaps some might have been commissioned portraits, perhaps by camp inmates, like de Klerk at Bloemfontein; but they look more like official records taken perhaps for charitable organizations, perhaps even by British officials. Either way, there is no indication as to how they came into the possession of Emily Hobhouse and her publishers. The information provided by the captions is little enough but the reference to the camp 'Irene' and the date 'November 1901' is sufficient to show that the photograph of the school children, at least, was not collected in the field by Hobhouse herself who did not visit that camp and was back in England at that date. On the contrary, indications are that the illustrations for The Brunt of the War were put together from a very small pool from rather disparate sources. Thus, on stylistic grounds, it is possible to identify two of the illustrations as commissioned portraits and, presumably because she knew more about their subjects, Hobhouse appears to have attached greater significance to them. The portrait of Johanna van Warmelo (Figure 5) has the caption 'One of the devoted band of Pretoria volunteer nurses'. But in her own copy of the book that survives in the library of the University of Cape Town, Hobhouse added to the caption 'a dangerous element in camp from Report of Lady Commissioners (words omitted by publisher)'. She also annotated the printed caption of her Figure 1 (Illustration 9), which appears to be a group portrait (like Illustrations 6 and 7) commissioned by a family to reassure absent menfolk of their well-being. Obviously because the photograph could not make the point that Hobhouse wanted, she annotated the original caption that read 'Occupants and furniture of one bell tent soon after arrival from farm. Nov. 1900' with the words 'The condition of this overcrowded family six weeks later was pitiable in the extreme (Words omitted by publisher)'. While this annotation is reminiscent of her comment in her letters on the photograph of the Geldenhuys family, in supplementing the information of her Figure 1, Hobhouse was no doubt mindful that Lizzie van Zyl's family had also entered a camp in November 1900 and that the dispute over her image turned effectively on the rate of her deterioration in the weeks that followed.

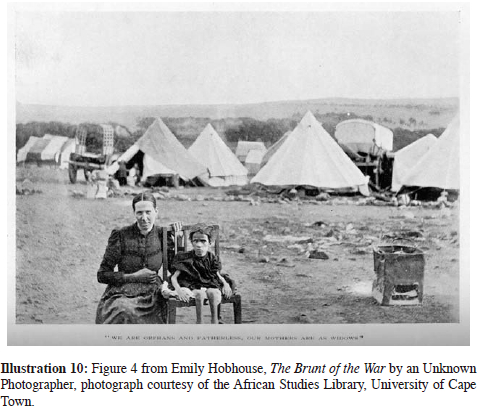

These annotations show that Hobhouse sought to use captions to concentrate and amplify the meaning of her illustrations in The Brunt of the War. Thus her Figure 3, that depicts two women and a child against a camp background, has the same mundane significance as other camp photographs until it is viewed with the caption, 'The last of seven, Wene. 1901'. This information ties the image to a particular camp (actually, Irene) at a particular time and, even, to a particular, if unidentified, family but directs the entire meaning of the illustration to the unimaginable experience of losing six out of seven children. In two other illustrations of suffering, however, Hobhouse clearly sought general, if not universal, significance in the way she phrased her captions. For her Figure 6 of an emaciated little girl seated on her mother's lap, Hobhouse provided the caption 'Feeling the brunt of the war. 1901', indicating that identity and location were completely irrelevant. For her Figure 4 (Illustration 10) that depicts another skeletal child, with tiny limbs exposed, sitting on a chair while her mother crouches close by, Hobhouse appears to have attributed epic proportions to the catastrophe by attaching the verse from Lamentations V, 3: 'We are orphans and fatherless. Our mothers are as widows.' Perhaps it was precisely because she did not know the full stories behind these images that Hobhouse was able extract such powerful general messages. In the process she appears to have discovered a truly symbolic representation of suffering in the camps in the image of the emaciated child. Doubtless the dispute over the photograph of Lizzie van Zyl helped Hobhouse get over her evident qualms in using such images for propaganda purposes. But in fact she was already aware of the rhetorical value of the form. On 31 January 1901, she had described to Lady Hobhouse in England how she confronted the officious commandant of the Bloemfontein camp with the emaciated body of a four-year old boy:

'Captain Hume,' I said, 'you shall look.' And I made him come in and shewed him the complete child-skeleton. Then at last he did say it was awful to see the children suffering so.34

Evidently, once this rhetorical space had been created, it was quickly filled by any image of extreme suffering, regardless of individual history and regardless of the photograph's original circulation. After the Peace of Vereeniging of 31st May 1902, the use of these images obviously shifted to a different cause. The photograph of Lizzie van Zyl was reproduced in the first Afrikaans edition of The Brunt of the War in 1923.35 And when Hobhouse returned to South Africa in 1903 to gather evidence for war reparations, she herself made water-colour drawings, mainly of devastated farm buildings, which were later published in War without Glamour?36

1 An earlier version of this paper was presented at the 'Representations of Pain ' conference at the University of Cork in April 2005: I am grateful to the convenors, Maria-Pia della Bella and James Elkins, for permission to reproduce it here.

2 Louis Changuion, Frik Jacobs and Paul Alberts, Suffering of War (Bloemfontein: War Museum of the Boer Republics, 2003: for Illustrations 1-8, the page number from Suffering of War is indicated in parenthesis). The War Museum probably has the largest collection of concentration camp (and war) photographs, but there are other collections in the Free State Archives, also at Bloemfontein, the Howick Museum, KwaZulu-Natal, the National Archives and the National Cultural History Museum, both in Pretoria, and in the Milner Papers, London. I am grateful to Elizabeth van Heyningen for bringing images from these collections to my attention, and for her comments on this paper.

3 Albert Grundlingh, The Anglo-Boer War in 20th-century Afrikaner Consciousness 'in Scorched Earth, edited by Fransjohan Pretorius (Cape Town: Human & Rousseau, 2001, 242-65).

4 Susan Sontag, Regarding the Pain of Others (New York: Picador, 2004, 65).

5 Ibid., 89.

6 S.B. Spies, Methods of Barbarism? Roberts and Kitchener and Civilians in the Boer Republics, January 1900-May 1902 (Cape Town: Human & Rousseau, 1977, 296). Paul Alberts compares the photographs of emaciated children directly with images from 'Hitler 's death camps ' in Suffering of War, 11.

7 Emily Hobhouse: Boer War Letters, edited by Rykie van Reenen (Cape Town: Human & Rousseau, 1984, 90).

8 Ibid., 92.

9 But she did at least understand them. In October 1901 the Australian news reporter Mrs Dickenson visited the 'so-called Refugee Camp' at Merebank with Mrs Erasmus, a camp organizer, and wrote: 'One pale, haggard woman sat at the entrance of her bell-tent, holding a child just at its last gasp, and wanted her photographed; but I told Mrs Erasmus to explain how sorry I felt for her, but that the photograph would have been such a painful one for her she would never have liked to look at it.' (Emily Hobhouse, The Brunt of the War and Where it Fell (London: Methuen, 1902, 204)). I am grateful to Elizabeth van Heyningen for this reference.

10 See Elizabeth Heyert, The Glass-House Years: Victorian Portrait Photography, 1839-1870 (London: George Prior, 1979, 46-7); and Asa Briggs, A Victorian Portrait: Victorian Life and Values as seen through the Work of Studio Photographers (London: Cassell, 1989, 192-5).

11 Report on the Concentration Camps in South Africa by the Commission of Ladies appointed by the Secretary of War (London: H. M. Stationery Office, 1902, 44).

12 Christraud Geary, Missionary Photographs: Private and Public Readings', African Arts vol. 24(4), Winter 1991.

13 Emily Hobhouse: Boer War Letters, 85.

14 Information kindly communicated by Elria Wessels, Chief Curator at the Museum in March 2005: Ms Wessels suggests the names of V. A. Fitzmaurice, Arthur Deale, and F. Armstrong of the Fane Studio.

15 Also communicated by Elria Wessels, who is a relative of the subject.

16 Hermann Giliomee, The Afrikaners: Biography of a People (Cape Town: Tafelberg, 2003, 256).

17 The speech is printed in Emily Hobhouse: Boer War Letters, 401-8.

18 Suffering of War, 153.

19 For example, Suffering of War, 127-31.

20 Susan Sontag, Regarding the Pain of Others, 64, draws attention to the photograph of British dead at the Battle of Spionkop that was circulated by the Boers in an attempt to demoralize their enemy. It was condemned as an outrage by Amateur Photographer that claimed that the image 'serves no useful purpose and appeals to the morbid side of human nature solely': see Pat Hodgson, Early War Photographs (New York: New York Graphic Society, 1974).

21 For example, Elizabeth van Heyningen has drawn my attention to the reports to the Colonial Office by Dr Kendal Franks, one of the camp inspectors, on the Bethulie Camp, which were illustrated by photographs: these reports are now in the British National Archives.

22 A. Conan Doyle, The War in South Africa: Its Cause and its Conduct, (London: Smith and Elder, 1902, 105-6).

23 Jennifer Hobhouse Balme reproduces Emily's letter to the Westminster Gazette in her compilation To Love One's Enemies: The Work and Life of Emily Hobhouse (Cobble Hill, British Columbia: The Hobhouse Trust, 1994, 441-4); and The Brunt of the War, 213-5.

24 Emily Hobhouse: Boer War Letters, 52.

25 To Love One's Enemies, 441.

26 To Love One's Enemies, 442-4.

27 Times, 5 March 1902, 7.

28 The Brunt of the War, 215, fn 2.

29 Emily Hobhouse: Boer War Letters, 111.

30 Report of a Visit to the Camps of Women and Children in the Cape and Orange River Colonies (London: Committee of the South African Distress Fund, 1901, 4).

31 Emily Hobhouse: Boer War Letters, 77.

32 In her letter to the Westminster Gazette, Hobhouse wrote that she did not know who took the photograph of Lizzie but, later, in The Brunt of the War, 215, she wrote: 'It was, I believe, taken by a Mr. De Klerk.'

33 Elria Wessels, Chief Curator of the War Museum, kindly confirmed in May 2006 that nothing is known about this photograph; she also confirmed that nothing is known of 'de Klerk' at the Museum. Nevertheless, with documentation at a premium, it is tempting to speculate that a new caption for our Illustration 6 might read: 'Attributed to "Mr. de Klerk", Group Portrait of the Geldenhuys and another Family, Bloemfontein Camp, early 1901'.

34 Emily Hobhouse: Boer War Letters, 54.

35 Emily Hobhouse, Die Smarte van die Oorlog en wie dit gely het, translated by N. J. van der Merwe, Cape Town: Nasionale Pers, 1923, opp. page 264.

36 War without Glamour: Women's War Experiences written by Themselves (Bloemfontein: Nasionale Pers, 1927). The paintings are now in the War Museum, Bloemfontein.