Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Kronos

versión On-line ISSN 2309-9585

versión impresa ISSN 0259-0190

Kronos vol.31 no.1 Cape Town 2005

ARTICLES

Photography with a difference: Leon Levson's camera studies and photographic exhibitions of native life in South Africa, 1947-19501

Gary Minkley; Ciraj Rassool

University of Fort Hare and University of the Western Cape

Leon Levson and social documentary photography

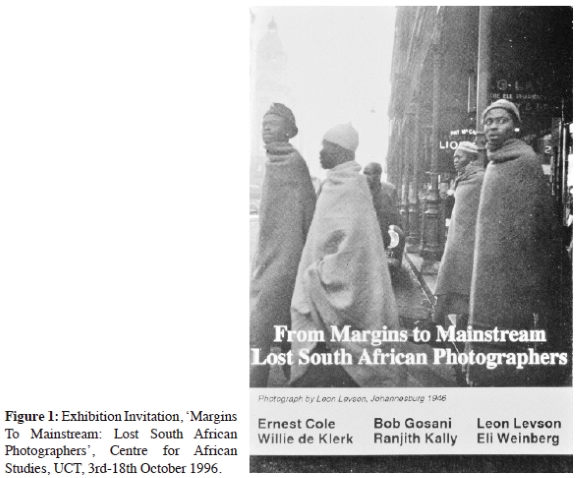

Five men are about to cross a Johannesburg street. It is 1946, although you cannot tell this from the picture. Four of the men appear young. The fifth, partly obscured by the slightly blurred man in the foreground, is older. He does not appear to be with the other four who all wear blankets and tight fitting hats on their heads. The blankets cover the men's bodies. It is only on one of the men that an outline of an arm is visible underneath. They literally fill the photograph with a sense of protective otherness in an unfamiliar urban landscape. The photograph holds movement, a motion forward, a destination. Two of the four men look sideways along the road - the other two almost pointedly not, but all four convey uneasiness in this moment of crossing - a moment that is unsettled, illicit in its capture. The fifth 'obscured' man does not appear to be clothed in a blanket. He does not wear a hat and he is bearded. He carries something on his back. Is it a bag, perhaps? At the centre of the photograph, but more in the background, he appears less hurried, and more familiar - more in place. Two of the young men are already in the road, one in mid-step off the pavement, the last still on the pavement. All around the men are the signs of the city: tall buildings, shops and glass, people, a parked motorcar whose headlight looks back at the camera like an unblinking eye. The four subjects appear poor, ill-dressed and blanketed - young men in a 'foreign place' and with little or no visible belongings.

This photograph, taken by Leon Levson in 1946, was used to frame a Mayibuye Centre exhibition held at the Centre for African Studies at the University of Cape Town from the 3rd to the 18th of October 1996.2 Entitled Margins to Mainstream: Lost South African Photographers, it featured the work of Ernest Cole, Bob Gosani, Willie de Klerk, Ranjith Kally, Eli Weinberg and Leon Levson. The Mayibuye ('Let it return') Centre for History and Culture was started at the University of the Western Cape in 1991 as a museum and archive of apartheid, with the repatriated visual collections of the International Defence and Aid Fund (IDAF) as the nucleus of its holdings. As a new institution of public culture in South Africa at the start of the 'transition to democracy', the Mayibuye Centre focused on 'all aspects of apartheid, resistance, social life and culture in South Africa' and set itself the task of helping to recover aspects of South African history 'neglected in the past' and to make these histories 'as accessible as possible'.3

This Centre for African Studies leg of the Mayibuye Centre's Margins to Mainstream exhibition was just one moment in a range of different showings for this exhibition around the country and internationally. Before it reached the Centre for African Studies, it went on show at the Standard Bank National Arts Festival in Grahamstown in 1994, and then at the Africa 95 festival of African arts in the United Kingdom. The original exhibition had been framed by a photograph of Eli Weinberg posing next to a giant image of his photograph of Albert Luthuli. The use of Weinberg and then Levson as representing 'lost photographers' was not incidental. Significantly, the Margins to Mainstream exhibition served to locate the Mayibuye Centre and its visual archive, cohered around Levson and Weinberg, at the heart of resistance social documentary photography in South Africa.4

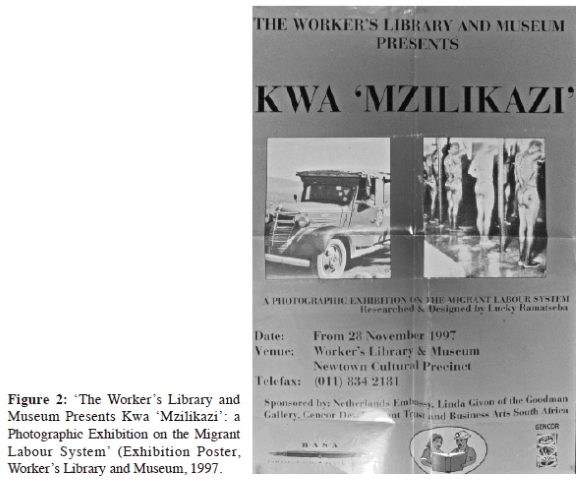

Little more than a year after the Centre for African Studies exhibition, a poster advertising an exhibition entitled Kwa 'Mzilikazi' at the Worker's Library and Museum in Johannesburg used a Leon Levson photograph to frame a photographic exhibition on the migrant labour system. The photograph is of a mine recruiting vehicle in a rural landscape and one which Levson himself labelled 'NRC Bus'. 'Indhlela Elula Eya Egoli - Kwa Teba' is inscribed on the side, although the photograph is cropped on the poster and only the first few letters are visible. On the poster, this image is counterposed to one of five naked men in a compound washroom.5

At the other end of the country, in a township outside Somerset West, a new community-based project in heritage and tourism, the Lwandle Migrant Labour Museum, used photographs in an exhibition on the history of migrant labour. Among the images displayed until 2001, most of which had been drawn from and attributed to the Mayibuye Centre, were Levson's photographs of a rural trading store, of people gathered outside a labour recruitment station and of migrant workers on the streets of Johannesburg. The latter photograph had been drawn from the same sequence as that which graced the Margins to Mainstream poster.6

On the Kwa 'Mzilikazi' poster, the photograph of the compound washroom together with the recruitment vehicle constructs a migrancy-compound-cheap labour narrative of force, control and regulation, a narrative of the 'compound as prison', and of worker resistance. The discursive spaces of The Worker's Library and Museum were also heavily reliant on Levson's images of migrancy and of social conditions on the mines to tell the workers' side of the story of the seams of gold in South African history - the story 'from below'. Equally, at the Lwandle Migrant Labour Museum, Levson's photographs were incorporated into a visual history that sought to illustrate a hidden past of migrancy, control and resistance. The photograph on the Margins to Mainstream poster is emblematic of a similar trajectory, placing Levson and his images of migrancy and the mines at the very heart of social documentary photography 'from below'. In this respect, Levson emerges as a defining photographer of black workers, a partisan photographer previously 'lost' and excluded because of his subject matter and a photographer committed to the exposure of the 'repressive' conditions on the mines and of the poverty of the migrant labour and apartheid system.

Gordon Metz, the former curator of visual collections at the Mayibuye Centre and curator of Margins to Mainstream, has argued that the South African social documentary photographer and the South African documentary tradition were defined by apartheid and the struggle against it. Here, the social documentary tradition was shaped and moulded by photographers who 'through their work and through their actions, chose to side with those who engaged, subverted and resisted colonialism and apartheid'. This tradition was therefore not neutral, but 'emphatically and un-apologetically partisan,' with a motive 'to raise awareness or consciousness to spur others into action.'7 For Metz,

[t]he photograph taken becomes an intervention and challenges a given set of power relations. Most importantly, for this to happen the photograph must enter the public domain, by way of exhibition, publication, etc. A photograph cannot become a social document if it lies forever hidden in a filing cabinet! ... Social documentary photography derives its meaning and its power in this public context.8

For Metz, the advent of democracy also significantly impacted on the social documentary photographic tradition. While 'before 1994 photography challenged the dominant power base from outside the mainstream media - from the margins of power so to speak - today these images and this tradition are part of the mainstream.' For Metz, this means their regular appearance in mainstream media and their exhibition in establishment cultural institutions. He concludes: 'the democratic project in South Africa now demands that all that was on the margins under apartheid should now find its place at the centre.'9

What is the context of Levson in this narrative from margin to mainstream? For Metz, the story of South African social documentary photography usually begins with the Drum era. This is probably because Drum magazine 'platformed and exposed the work of a number of black photographers for the very first time.' Their photographs alongside the texts of black writers were to give 'image and voice to black South Africans for the very first time in the popular press and media.' At about that time, Leon Levson's work became exposed to a wider South African audience. Another photographer, Eli Weinberg was connected more directly into 'the activist tradition.'10

For Metz, the 'roots and characteristics' 11 of the South African social documentary photographic 'tradition' in the 1940s and early 1950s had three identifiable components. It had black photographers like Gosani, Cole, and Peter Magubane capturing black image and voice. It had Eli Weinberg in the 'activist tradition' of alternative media as political resistance photographer documenting the major campaigns, events and leaders of resistance. And it had Levson, by implication, also with ties to this 'activist tradition' but in less direct and overt ways. In effect, then, Levson is placed in the social documentary tradition through apparent defining characteristics: black lives, alternative exposure, social 'resistance' connections, the characteristics which simultaneously define the emergence and characteristics of social documentary photography itself in South Africa.12 Indeed, elsewhere, Metz argues more explicitly that Levson was 'possibly the first South African social documentary photographer of note' because of having set himself the 'specific task' of 'documenting and interpreting African life'.13

Running alongside this positioning of Levson as one of the founders of the social documentary tradition in South Africa are three related processes. The first is the locality of the Levson Collection in the Mayibuye Centre and the ways that this photographic collection, together with that of Eli Weinberg and the Drum photographers, constitute the founding archive and mainspring of social documentary photography in South Africa. The second related process concerns the inclusion of the entire Leon Levson Photographic Collection within that tradition. Thirdly, the relationship between Levson's photographs and the imaging and imagining of the production of South African history in the present are significant aspects.

One aim of this article, then, is to comment on the ways that social practice in South Africa has placed certain kinds of photography 'within the truth' of recent histories as History. The rhetoric of a particular photography's social documentary 'transparency' from the 1950s, or its lack of visibility and exclusion because of 'apartheid' has marked the South African photograph with a pervasive dichotomy. On the one hand photographs are read as 'a conduit and agent of ideology,' or on the other, in opposition, as the 'purveyor of empirical evidence and visual "truth"' about apartheid and resistance.14 When this scopic dichotomy of apartheid modernity is brought together with the particular realist claims made for the emergence of social documentary photography in a particular time and place - and with an alternative locality and archive, as well as a practice and purpose - entire histories emerge as 'always already there' in sight and sound, on one side or the other. It is however this history itself that needs to be made visible: of how certain photography is invested with authority and 'reality', while also showing how particular conventions and institutions confer this authority. At the same time, though, we also wish to reflect on how these meanings rely on erasures as well as an accretion of visual and signifying codes which both dramatise and disrupt the real, partly because of the public meanings and knowledges about pastness that are constituted as the real through them.

Social history and visual evidence

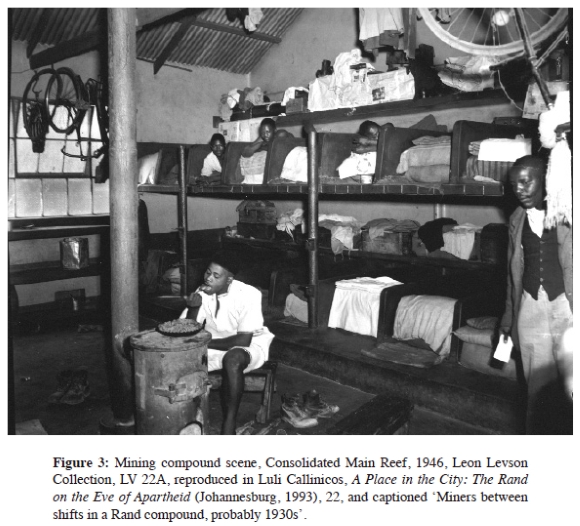

In the 1990s, the Leon Levson Photographic Collection in the Mayibuye Centre, and (with the Eli Weinberg Collection) the Mayibuye Centre itself became a central ('mainstream') archive for the retrieval of historical images of black South Africans in the 1940s and 1950s. Levson's images displayed on the discursive spaces of gallery and museum walls and on posters are one very important context. Equally important is their prominence in key social history texts, the most notable of which is Luli Callinicos's A Place in the City: The Rand on the Eve of Apartheid, Volume 3 of 'A People's History of South Africa'. Published in 1993, on the eve of democracy, it is Levson's photographs (and those of Eli Weinberg) from the Mayibuye Centre that mark this history. Inevitably there is the image of mining, a rather clean, neat and orderly compound image. Callinicos uses it to draw attention to 'crowded conditions and minimal sleeping spaces', to 'inadequate storage facilities' and a 'primitive heating system' endured by migrant workers.15

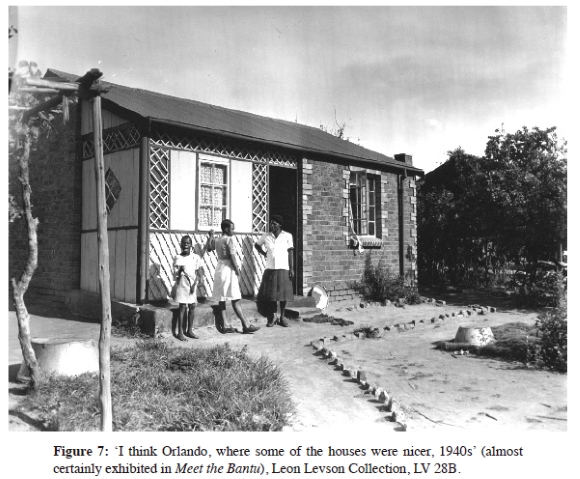

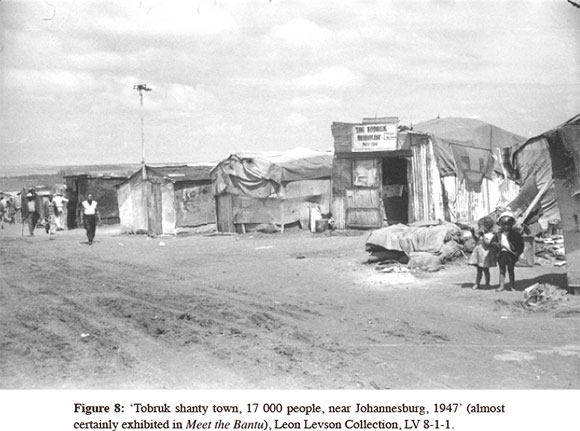

But the Levson images selected for A Place in the City are not only those of migrants and mines. There are four other broad categories or frameworks that locate Levson's photographs within social history as documentary images 'from below'. The first is 'The Decline of the Reserves' and features reserve landscapes which can be captioned with notions of the 'absence of able-bodied men', of the 'burdens' which fell on women and children, and of 'dependence' by families on the 'small pay packet' of miners. The second is that of 'mission education' in the Reserves - and the ambiguous landscapes of literacy and modernity, but also with attention drawn to issues of the 'disintegration' of 'traditional cultures', and the contribution of missionaries to the 'breakdown of the rural economy'. The third framework image is the urban landscape of the township and the squatter settlement, repetitively pictured as 'a typical township scene' or 'typical location scene'. This township/ location/squatter framework is constitutive of an environmental black urban landscape that foregrounds squalor, children, poverty and the 'slum'. The fourth group of photographs is of township life, but here depicting 'flourishing communities' and read as documenting an alternative township culture around weddings, music, hawking, recreation, etc.16

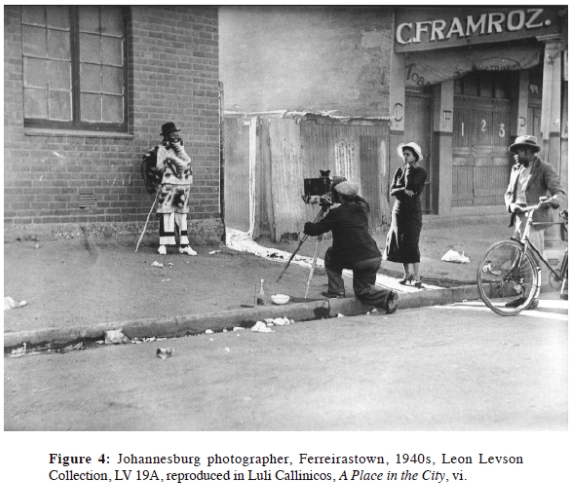

Perhaps the most important Levson image in the Callinicos book, though, is the first photograph following on from the Contents page. It is a photograph of a 'township pavement photographer' taking a photograph of a black 'client'. The man being photographed stands against a brick wall. He is smiling and is flamboyantly dressed: hat, blanket, baggy (perhaps 'houseboy') pants with geometric stripe (almost like a frame) and white unlaced shoes. In his right hand he holds a long stick and his pose is staged, held still, yet also infectious. Standing next to the photographer on the edge of the pavement - but looking elsewhere (down the street?) is a woman, hand on neck, left foot slightly raised on her heel. She wears a hat and a stylish dress - modern and below the knee. She might be aware of the other photographer, although her pose is one of impatience, disinterest, self-consciousness, perhaps of one waiting her turn? On the right of the photograph, just entering the frame, perhaps just arriving on the scene, is a man with a bicycle. He has stopped on the edge of the road and is watching the 'pavement photographer' take the photograph, or perhaps he is looking at the woman. He is dressed in hat, jacket, trousers, shoes, and the bicycle is held with a grip of ownership and of control. The photographer is half-kneeling, eye pressed to the lens, left hand about to take the photograph. The camera is on a tripod, an old box camera (unlike Levson's which was a new hand-held model). A bowl, bottle and implement, perhaps the tools of the trade, are on the ground next to him. The photographer wears a cap and is well dressed. His bent knee barely touches the edge of the pavement. There are signs of the city in the street - refuse, spill, papers. A black photographer? Maybe. On the top right of the photograph, there is another building with a sign, C.FRAMROZ. And below this the beginning of a word: TOB (TOBACCONIST?), the initials C F R frame the doorway and the shutters, which carry the numbers 1 2 3. In the central background is a roughly made building constructed of different sheetings of galvanised iron. Is the photographer C.Framroz? Maybe. But the shop appears closed. There is a doorway - a gap - between where the shack ends and building begins and sunlight is streaming through making a pathway. The woman stands in this path, illuminated, centred, as does the man with the bicycle. Are they being invited in? Or is this an exit point? Who belongs where? Who relates to whom? Where does history reside and power hide in this image?

Why did Callinicos choose this photograph, and give it such prominence as a key signifier of people's history and 'a place in the city'? Is it because it reflects the discovery of an image of 'pristine quality of unpublished social history' or because of the 'many messages to be found in a photograph,' both of which are suggested by Callinicos in the Acknowledgements.17 Stated more fully, Callinicos suggests that

[a]s important as the words are the images of the past. I have, especially since the unbanning of newspapers and documents, uncovered and collected hundreds of photographs. Rare, forgotten, grainy and blurred, many are, heartbreakingly, almost unreproducible. Side by side with these finds, I had, at the suggestion of David Goldblatt, also discovered a rich collection of beautiful, clear, first-generation prints.... The problem was how to combine the old and fuzzy, but historically valuable with the pristine quality of unpublished social history.18

The Levson photograph, though, is uncaptioned, unacknowledged. Its use lies in its discovery, in its historic value as a piece of visual evidence of 'people's history' or social history, in its image as a document of social life and culture. But its use also resides in a collection and an archive. In this respect, the relationships between social history and a social documentary photographic tradition, which places Levson within the Mayibuye Centre and within that realist trajectory, also places Levson's work within the trajectory of that social realist historiography. Levson's photographs come to stand for black experience. They do not necessarily require caption or explanation, and are viewed not with the suspicion of ideology, but with the trust of objectivity and reality across lines of subject, location and event. In a real sense they are amenable to any caption or explanation within the framework of social history. It is not surprising that this very photograph also became the signature image of the Mayibuye Centre, where it graced its annual festive season postcards for a number of years. Levson's photographs (and his archive) are also seen to be somehow intrinsically oppositional.

Photographs of the reserves, of squatter camps, of migrancy and the mines, of street life and location culture, where the central and often only subjects are black people, confer this explanation and this meaning. His photographs are seen to cross the lines of power and to take sides confirming and affirming the explanations of written social history. Here Levson's photographs are the real and the real of social history is resistance.

And Levson? Why did he take the photograph?

Artist, field photographer and social documentist

Leon Levson was born in Lithuania in 1883. Apprenticed to a photographer in Kovno when thirteen, Levson came to South Africa with his parents in 1902, arriving on the day of the funeral of Cecil Rhodes. He initially worked in the Duffus Brothers photographic studios in Cape Town and moved to Johannesburg in 1908, while continuing to work for Jack Duffus in their Johannesburg studio. He later took over the Duffus studio in Pritchard Street. These premises were later rebuilt and 'Levson's window of photographs in Hepworth's Buildings continued to be an attractive landmark for the best part of 50 years.'19

Originally trained in wet plate portrait photography, Levson established a reputation in South Africa as a 'fine, sensitive and original portraitist; the renowned, the notorious and the obscure found their way to him.'20 In 1914, he photographed General Louis Botha on the first occasion the Boer leader put on a British Army uniform, and thereafter became his official photographer, while also visiting and photographing Botha on his farm. After the First World War, Levson visited America, and then later and throughout his life, spent periods of time in the United Kingdom and in Europe. On these journeys Levson's engagements with both the mechanics and techniques of photographic reproduction involved visits to Kodak, spending time in film studios and meeting and studying the work of leading photographers, especially of art photographers like Steiglits and Steichen. At the same time, Levson's interest and fascination with art intensified. His studio premises housed art exhibitions of contemporary South African, English and European artists, which included Edward Wolfe, Irma Stern, Dorothy Kay, Pierneef, and from time to time, he painted landscapes, still lives and urban scenes himself. This passion fuelled an on-going tension and self-reflexive debate around the status, meaning, and content of his photography in relation to art. In the late 1920s and early 1930s Levson also became involved in photographing for the theatre or stage photography and produced many display photographs of plays produced in Johannesburg.

However, it was a commission by Imperial Airways in the late 1920s to undertake one of the first flights on the Sunderland flying boats, and to take publicity pictures that led him to begin to realise 'the possibilities of photography away from the studio.'21 During World War Two, Levson took his camera 'into the factories' and he produced an exhibition called South Africa's War Effort, which was commissioned by the Energy Supply Commission (Escom) as war effort propaganda. Described as being made up of 'large pictures emphasizing the visual magnificence and intricacy of pattern in modern industrial produc-tion,'22 the photographs were seen to provide '[b]y their carefully selected composition and emphasis on essential character ... a keen grasp of subject matter.'23One report went further to suggest: 'Mr Levson does not show us interiors of vast machine shops peopled by a hundred workers, but chooses for his expression individuals intent on the job whether it be at the melting pot or the sewing machine.'24 Displayed, along with some portrait photographs and Levson's own paintings, under the heading of Pictures of South Africa's War Effort and Portraits of Some of Our Prominent Men, the exhibition was held at the Argus Galleries in Cape Town, starting on 11 September 1943 and at the Gainsborough Galleries in Johannesburg, starting on 14 December 1943. Portraits included those of Smuts, Reitz, Van der Bijl and other of the country's 'political and industrial leaders.'25 The inside cover of the brochure for the exhibition contained a 'delightful South African landscape' with the caption 'The Land We Are Fighting For' and which was seen to contrast to the scenes of mechanical toil.26

There are many comments on this exhibition, but two further descriptions are important. The first reflects the public emergence of Levson as field art photographer: 'the pictures are not merely a fine pictorial record of South Africa's busy war industry and general expansion. They are magnificent pictures, many of them spontaneous shots that yet have the composition and design of carefully posed and lighted work. They are not only brilliant technically, but works of art.'27 The second, though, is perhaps more important, reflecting Levson's emergence as social documentist:

Mr Levson was given by the authorities all facilities to make this record, and every factory and every workshop working for the war effort was carefully studied and its characteristic features recorded. In years to come when South Africans want to know what their country did in these crucial years of warfare, no books and no documents will speak more eloquently than Mr Levson's collection of photographs.28

This was followed in November 1945 with a self-exhibition, held in his studio, entitled Monoprints. Here Levson argued that

photographic portraiture is in its nature documentary and, as such, it must faithfully record life in all its realism. But in order that a portrait may make a wider appeal than to those immediately interested in the subject, it must have a decorative value .... I am holding this exhibition of Monoprints along with some of my usual work, which I hope may show in what degree vitality and decorative quality can be attained through the medium of photography, and which may also awaken fresh interest in the craft of the photographic portraitist.29

The portraits displayed included Smuts, Bishop Clayton, Dean Palmer, Van der Bijl, W.R. Thorne, and the artist Jean Welz and sculptor Lippy Lipschitz. Importantly this exhibition included a separate section called 'Monday in Cape Town', a series of photographs of 'washing day in the Malay quarter, beginning at cockcrow and ending at sundown.'30 Increasingly, Levson himself began to claim a documentary and realist space for his photography and this feature finds its most expressive and constitutive moment in his journeys after World War Two.

These exhibitions and their images set the stage for Levson's subsequent work in three important respects. Firstly they placed Levson himself within the combined contexts of 'field' photography and social documentary. Described in 1943 as 'essentially a realist,'31 Levson's work extended and helped constitute an emerging public discourse about photography in South Africa at this time. In essence, this implied that the mechanical print moved out of the studio and into a field of documentary as a defining photographic lexicon. 'Documentary they are', declared art critic Prebble Rayner of Levson's work, 'and that is as it should be, for that is the first province of the camera.'32

Secondly, the photographs (industrial, military and portrait) began to image South African modernity, through picturing and joining the political and the industrial, leader and citizen, state and nation, 'men, women and machinery at war' in the dramatisation of 'power and heat.'33 The dense catalogue of pictures of 'Precision Grinding', 'Forging at the Mint', 'Machining Howitzer Barrel', 'Woman's Job - 1943' and many others all told more than a story of a land assisting the war effort, but also - to draw on one exhibition's title - a 'land we are fighting for'. This was a land of the industrial modern, the city and the 'tamed' nature of the countryside. It is not incidental that - as far as we can tell - the photographs on display were of white people, 'civilian' men and women, English and Afrikaans, at work, combined with the 'possessive individualism' of political and industrial leadership. In this respect every portrait implicitly '[took] its place within a social and moral hierarchy'34 and enabled the imagining of the South African modern in a field of vision that both included white distinction and erased black difference.

Lastly, this 'realist' or documentary move, and the subject matter of the images and their public display had significant implications for picturing the past. These exhibitions helped to re-constitute the subjects of history and the field of History - as documented by the very subjects imaged and portrayed. History had been captured and defined as white, ruled by Smuts, Van der Bijl and Reitz and moved forward by the modern industrial forces of power and heat. These exhibitions documented a present against which subsequent exhibitions could acquire meaning and realise their subject's erasures from History into culture, nature and unwanted transition.

Meet the Bantu: camera studies of native life

Leon Levson recollected later, in 1961, that this work was followed by an exhibition of pictures of African life, in which he had long been interested and for which he had travelled extensively in collecting. This work was first shown in London, where it was opened by the Countess of Clarendon and at which the Earl of Athlone. Later it travelled to several centres in South Africa.35 Levson's wife, Freda, also made cryptic biographical notes about this shift:

On first holiday after the end of petrol rationing motored with camera through native territories and made a collection of pictures of native life, first exhibited by the Royal African Society in London, and then by the Institute of Race Relations in Johannesburg and Cape Town.36

Levson acquired a miniature camera, which 'suited the quick selection of subject and his unobtrusive methods of work outside the studio.' With this camera, wrote Freda after Levson's death in 1968, he 'wandered' around South Africa after World War Two, 'making a visual record of contemporary African life.'37 Levson travelled to the Reserves and to the 'High Commission Territories' of Basutoland, Bechuanaland and Swaziland, while also documenting 'native life' on the Witwatersrand. He literally took hundreds of 'Native photographs'. He visited Zululand from the 5th to the 20th of June 1946, Natal, Pondoland, East Griqualand and Transkei from the 21st of September to the 14th of October 1946 and Transkei, Ciskei and Herschel some time in 1946. He went to Basutoland and Bechuanaland from the 12th to the 16th of January 1947. He also photographed Johannesburg shantytowns and townships between 1945 and 1947.

These photographs gave rise to a number of interrelated exhibitions. The first was held at Foyle's Art Gallery in London under the auspices of the Royal African Society. It ran from the 30th of September to the 11th of October 1947 under the heading Meet the Bantu: A Story in Changing Cultures and was described as an 'Exhibition of African Camera Studies'.38 The cover photograph on the catalogue featured the portrait of a young woman in 'traditional dress'. In the Introduction to the exhibition Levson defined their context, meaning and significance in the following terms:

These photographs are intended as an introduction to the Bantu peoples of South Africa at this crucial time in their development, as they strive to pass from their primitive way of life into the stream of the Western world. ... The mines depend on an abundance of labour. ... These thousands of primitive folk return after their short terms of service to their far-away homes, taking a smattering of western 'civilisation' and the strange mixture of good and evil they have picked up, disseminating it over the whole sub-continent, and the importance of this influence cannot be over-rated.39

Further, Levson suggested, history had 'bequeathed' to Southern Africa 'a number of difficult problems', just as it did in other parts of the world which had 'mixed populations'.40 Levson's sense of African history is worth quoting at some length:

Under the impact of Western civilization primitive peoples are apt to lose their tribal standards and responsibilities, and at the same time to find difficulty in accepting or understanding new and unfamiliar concepts.

These photographs are an attempt to show the effect in all its incongruity of this impact upon the unsophisticated African. There is no attempt here to recall the picturesque and dying past, but rather to capture some of the kaleidoscopic, living present; to show in some measure how these gay, warm, friendly people live, in their primitive charm and dignity, in their 'civilized' ambition and crudity, in their sometimes successful westernization, and in the strangely haphazard stages in between.

You will see people from many different parts of the country, the homes they live in, and the clothes they wear; you will meet them again, their place of origin unrecognizable, in the melting-pots of the big towns, but you will find that amid all the difficulties of life in an alien environment they are the same happy-go-lucky friendly souls. The primitive African is sometimes admirable, often lovable, generally exasperating, but always intensely human in his frailty and strength.41

The exhibition itself was divided into nine 'Camera Groups.42 These included: 'The Country and the Kraal' (16 images), 'Childhood' (12), 'Initiation Dance' (5), 'Individual Studies' (27), 'Daily Life in the Kraal' (24), 'First Contacts with Western Civilization' (12); 'The Mines' (20); 'The Townships' (27); 'The Future' (40). Each 'Camera Group' had accompanying text. The associated media reviews carried headlines like 'Changing Native Culture', 'The Evolution of the Bantu', 'Characteristics of the Bantu' and, of course, 'Meet the Bantu'.43 This basic exhibition with the same broad 'Camera Groups' was shown and reshown in South Africa on at least three occasions, although the name of the exhibition was changed each time, and some of Levson's descriptions and ordering, as well as some of the images, were altered or added to. Where Are We Going? was exhibited under the auspices of the South African Institute of Race Relations (SAIRR) at the Gainsborough Galleries in Johannesburg in August 1948 and at Ashbey's Gallery in Cape Town in September 1948.44 Whither Now? was the name under which the exhibition was shown under the auspices of the Johannesburg International Club in March and April of 1950, also at the Gainsborough Galleries. And The Native Way of Life is what it became when it was shown at the Kimberley Boys High School in August 1950. At the 1950 Johannesburg International Club exhibition 'Childhood' had become 'Childhood in the Country' and 'Individual Studies' carried the heading 'Portraits of Country Folk'. In Kimberley, 'Initiation Dance' became 'Adolescents' Initiation Dance' and 'The Future' became 'The Prospect'. The South African media reported on this exhibitionary sequence and its associated lectures in articles entitled 'Studies of Native Life By Leon Levson', 'Photographic Record of Native Life' and 'Photographs of Native Life: A Camera Sermon'. In Kimberley, the exhibition carried headlines like 'Natives in Union Well Treated' and 'Native Life in Photos'.

As Levson's photographs of 'native life' journeyed through England and South Africa to be displayed in exhibitions given different names, they became the setting and backdrop for lectures and talks on a range of themes connected to the 'native question' in South Africa. The interests of the Royal African Society, under whose auspices the exhibition had been held in London, were ostensibly to 'spread knowledge and understanding' of 'political, social and economic questions' about Africa, as it entered 'a new era'. This it did by providing a library, publishing a journal, holding meetings addressed by people 'with first hand knowledge of Africa,' and 'co-operating with other Empire organisations' in spreading knowledge. Under the leadership of two former colonial officials, the Earl of Athlone and Lord Hailey,45 the Society brought together scholars and 'men (mostly) on the ground', whose background and interests were centred on colonial administration and those who were keen to extend their experience and skills to African people and societies in order to ensure their 'development'. At Foyle's in London in October 1947, the former Provincial Commissioner of Uganda, JRP Postlethwaite, CBE, spoke on 'Africa - the dream and the reality' while Maurice Webb of the Indo-European Council of Durban gave an address called 'South Africa: What Next?' And just to ensure that all possible angles of 'native studies' were covered, Dame Sybil Thorndike, DBE was asked to address an audience on 'Colour and Rhythm.'46

At the Gainsborough Galleries in Johannesburg in August 1948, where Levson's photographs fell under the ambit of the SAIRR, lunch-time talks were given by four 'leading experts' on African matters. Hugh Tracey spoke on 'African Folk Music,' Uys Krige on 'Drama in Africa' and Victor Mbobo on 'the Impact of European Influence on Bantu Culture,' while Arthur Keppel-Jones lectured on 'The Native in SA History.' The exhibition was opened by Major-General Sir Francis de Guingand, who had just been Chief of Staff to Field-Marshal Montgomery, but who before had spent 'six years in Nyasaland and Tanganyika, trekking about the country and living amongst the natives.' His business interests had taken him 'all over the southern part of the Continent' and he was able to grasp 'the essential core' of South African labour problems. De Guingand was convinced that 'only a liberal policy of education and training of the Native can bring a real advancement in Africa's prosperity.' The 'initial stage of education given to the Bantu,' he argued, 'must be weighted on the side of agriculture and manual pursuits .... An academic education with a political bias was hardly what was wanted to-day.'47

During March and April of 1950, Levson's photographs were back at the Gainsborough Galleries, this time to be exhibited under the auspices of The Johannesburg International Club, which had been formed the year before to promote 'goodwill among persons of various races.' Originally intended to be opened by the Director of Native Labour, P.G. Cauldwell, instead, the exhibition was opened by the Bishop of Johannesburg, the Right Reverend Ambrose Reeves. This time, a wider variety of academic, social and political interests, which converged on 'the native question', were expressed in the lunch hour lecture programme. Again Hugh Tracey spoke, this time on 'Bantu Recreation'. M.D.W. Jeffreys, of the Department of Bantu Studies at the University of the Witwatersrand, gave a general talk on 'Some Aspects of Bantu Life,' botanist, Eddie Roux, lectured on 'The African and the Land', while former ANC President-General, A.B. Xuma, who was also Honorary Life President of the Johannesburg Joint Council of Europeans and Africans, spoke on the 'Problems of the African in the Urban Areas.'48

Two years earlier, Roux had published a radical nationalist monograph on the history of South Africa, later described as 'a history of the black man's struggle for freedom.' In the previous year, he had published his research on land and agriculture in the reserves as a chapter in the first Handbook on Race Relations in South Africa, published for the SAIRR.49 The interests of the SAIRR lay in fostering 'good relations between the peoples of South Africa' through 'justice and fair play, courtesy, mutual respect and tolerance,' but also through 'understanding and knowledge.'50 This landmark publication had seen the expression of these interests within the academy, with a range of academics drawn together with writers from government bodies, philanthropic institutions and welfare organisations. The broad spectrum of topics, ranging from native administration, agriculture and urbanisation to education and welfare, politics and culture encompassed the academic field of Bantu Studies in all its aspects. The Director of the SAIRR, Quintin Whyte, formerly of Healdtown and Lovedale, contributed a chapter on perhaps the key aspects of all the work of the Institute, the promotion of 'inter-racial co-operation' in the furtherance of welfare and education.51The paternalist politics of the institution of Joint Councils and the SAIRR itself as their intervention on 'the native question' were expressed in Whyte's conclusion to his chapter:

[It] is certain that for many years to come the advance of the Non-European peoples will depend to a great extent upon the active collaboration and help which they will receive, not only officially from a European-dominated government, but also from a sympathetic and liberal-minded European public, on whose shoulders has so far lain the responsibility for the initiation of inter-racial co-operation.52

In a foreword to a brochure accompanying the 1950 exhibition of Levson's photographs of 'native life', Whither Now, Whyte took the opportunity to place Levson's work within the liberal framework of paternalism and trusteeship. Levson, he said, had contributed 'his high talent to the search for a happier South Africa.' Apart from 'obvious aesthetic considerations,' Levson's photographs had '[brought] home to Europeans the African as a human being with all the common attributes of humanity.' If 'Europeans would learn to respect the African as a man, with hopes and fears and aspirations ... then we would have gone a long way toward a more peaceful country.' Africans too 'must play their part' to 'create a strong united South Africa.' But 'the burden of responsibility and initiative, lies on European shoulders.'53

Around this time, Levson's photographs were also seen as an implicit critique of attempts by the government to create visual images of South Africa for international circulation. Indeed, in 1948, they were described as 'a good answer to the distortions of the Government,' which had sponsored a photographic exhibition, Meet South Africa, which toured the United Kingdom. While this exhibition had been 'an embarrassment to any thinking South African,' Levson's photographs presented 'an honest picture of the Bantu.' The fact that Levson's pictures were accompanied by a wall of 'some telling statistics' served to make the point that 'all [was] not well in the state of South Africa.'54 And in the left-wing Guardian, readers were encouraged to see Levson's exhibition, many of whose photographs were 'disturbing', but which were "an eye-opener to those who don't realise what is happening around them".55

In spite of the positioning of Levson's photographs in such critical ways, exhibitions of his work also provided opportunities for government apologists to express themselves. It is not clear how or why Levson's exhibition found its way to Kimberley, but apparently, it was exhibited under the auspices of the 'City Arts Club'.. In Kimberley, in August 1950, the exhibition site for Levson's photographs was the Kimberley Boys' High School. Having started off in London in 1947 as Meet the Bantu, a title perhaps inviting viewers to engage with images of African people, the exhibition took on more questioning names on its route through South Africa Where Are We Going? and Whither Now? perhaps more consciously invited viewers to engage with policies on native affairs, and maybe even racial attitudes. Now in Kimberley, the exhibition was called, rather descriptively, Photographs of the Native Way of Life.56 We have found no evidence of any exhibition brochure, nor any public lecture or discussion programmes for the Kimberley exhibit. The exhibition was opened by W.B. Humphries, who used the opportunity to describe how well Africans were treated in South Africa:

No administration in Africa treated its Natives better than South Africa.... The Native of South Africa was given every assistance by the European, who cared for his schools, hospitals and the means of his livelihood. The Rand gold mines had become known as the Natives' university.... It was a pity ... that some criticism from overseas distorted the true position. If people only knew how well South Africans treated the Native there would be no such criticism.57

What is clear is that Levson's 'native photographs' exhibited in galleries and schools in London, Johannesburg, Cape Town and Kimberley served as backdrop and set for policy discussions and interventions around the 'native question' by scholars, government officials and those connected to institutions that felt they expressed the interests of Africans. The exhibition goers, who constituted their audience, were expected to be white. As they viewed the sequence of photographs which began with 'The Country and the Kraal' and 'Childhood in the Country' and which ended with 'The Mines', 'The Townships' and 'The Future', they were also invited to listen in on these talks which ranged from sympathetic accounts of the conditions of African lives to views which championed the cause of Bantu Administration. Both positions, the paternalist, as represented in the interests of the SAIRR and the Johannesburg International Club, as well as the segregationist - as it was being reconfigured as apartheid's system of Bantu Administration - saw a use for their cause in Levson's images, a visual record of the observation of African people. And these two positions constituted two poles of the same discursive system, the discourse on Bantu Studies, which was also the framework of Levson's photographic endeavours.

In the midst of these exhibitions, there was an initiative to publish the photographs, along with an extended text. It was to be entitled African Pageant: A Picture of a People on the Move. Significantly, the authors were identified as Leon and Freda Levson. Freda had collaborated with Levson as his fellow-traveller on photographic trips and later as co-writer of texts for his exhibitions.58 The manuscript contained an introduction by Alan Paton, author of Cry the Beloved Country, and a historical section called 'Background in History.' Although the manuscript is not dated, there is a draft of Paton's introduction sent to Levson on 4 April 1949, and the categories of the Kimberley exhibition correspond very closely to the draft manuscript. The manuscript was submitted to Norman Berg of Macmillan, some time around 1949 or 1950. In 1976, more than fifteen years after the Levsons left South Africa for Britain, and eight years after Leon Levson's death, the unpublished manuscript was once again prepared and re-edited for possible publication.

The 1949 text told a history of the African's move 'in a comparatively short time' from 'a very primitive, pastoral, semi-nomadic way of life into the closest connection with a western industrial machine.' 'Precariously slung between these overlapping yet vastly different ways of life,' the purpose of the photographs was 'to capture and record the moment of transition, this travail of a people.'59 It also confirmed a paternalist politics and intent in the photographs' exhibition and their intended publication. This was 'an attempt to introduce men of good will to the dilemma of a simple people in the grip of forces outside of their control and generally beyond their comprehension.'60

In 1976, in the context of many South Africans and their political organisations being in exile in London, there was an attempt to re-inscribe Levson's photographs with new meaning. The result was a text of contradiction. A new preface put forward a solidarity history of South Africa, one that was sympathetic to an exiled liberation movement. This account explained the operation of apartheid in economic ways, with references to cheap labour, and which accorded Africans a sense of agency. However, contradictorily, in spite of much editing, rewriting and overwriting, the organisation and visual language of the 'camera groups', their naming and their descriptions remained firmly within the older Bantu Studies discourse, which would encourage readers to 'meet the Bantu.'61

In April 1948, another Levson exhibition took place in Johannesburg, this time in the setting of the Municipal Library. Entitled Hands at Work, it was an exhibition of 'British Industrial Photographs'. Described in the catalogue as 'recording with an individual lyricism a phase of Britain's mounting export drive' through a series of images taken in Clydebank, Merseyside and the Potteries, these 'lens-eye views' reflected Levson's counter-tour in the UK. Levson's images from the 'field' in Britain were now exhibited in South Africa shortly after Meet the Bantu had been shown in London. Sponsored by the United Kingdom Information Office, the exhibition both sought to 'show how British articles in every day use in South Africa are produced' as well as to 'show how, in pictures, South Africa's part in Britain's recovery - the export of gold, wool and fruit.'62

We were reminded here of Martha Rossler's comment that 'imperialism breeds an imperialist sensibility in all phases of cultural life.' Levson himself commented on one of his primary objectives in the exhibition: 'that he would particularly like Native workers in this country to see the exhibition', for 'it might stimulate in them not only a new appreciation of the dignity of honest labour but would show them white men cheerfully doing many manual jobs generally assigned to the Natives in this country.' It also makes one think of the unequal circuits of vision Levson occupied as he did 'his part in introducing Africa to Britain in an exhibition of Native types' and then returned 'home' with 'the spirit of Britain's national life' in the dignity, cheer and pride of labour from the imperial present and imaged presence.63

Archival meanings

Before returning to the 'native exhibitions' and the archive of these photographs more closely, we want to complete this genealogy of Levson's work through the 1950s. In 1950 Levson was commissioned by Anglo American to photograph the newly developed goldfield in the North West Orange Free State. This resulted in an exhibition, The Orange Free State Goldfield: Exhibition of Photographs, which 'illustrated' and celebrated 'the progress made in development of new mines, new towns and a large new industrial area in South Africa's new goldfield.'64 The exhibition was divided into four sections, entitled 'The Story of its Discovery and Development', 'The Native Mineworker: Advanced Ideas in Hostels and Villages', 'Welkom: Building a Model Modern Town', and 'Essential Services: Power, Water, Railways and Roads'. The exhibition was initially held at the Johannesburg Public Library in October 1950, and in January the next year, was taken to Central Hall, Westminster in London. In March 1951, the photographs were brought back to South Africa where they were displayed at the Bloemfontein Agricultural Society's Show in an exhibit sponsored by Anglo-American.

There is a range of issues here around imaging modernity, industrialisation and the mines amongst others, but most significant for our discussion are the forms of 'native mineworker' representation attached through the 'tripod' of image, text and caption. Displays 48-65 of the exhibition constructed a narrative of migrant modernity that literally celebrated hostel dwellings, outdoor courtyards, and outdoor cinema. 'Natives relaxing in their own rooms in the hostel or using their leisure in various arts and crafts' and '"balloon" houses built for married Natives (resembling in shape their own kraal huts but otherwise providing facilities and amenities unknown to the kraal Native)' were two of the photographic groups of the exhibition. Also presented were clean images of nutritional services, electric lights, hot and cold water, sanitary facilities, and so on.65 By the time this exhibition went up in Bloemfontein in 1951, this section of the exhibition carried a banner slogan: 'African workers are well-housed.'66

The celebratory photographs of mineworkers, migrancy and compounds in this exhibition, stand supposedly in stark contrast to the form of representation that has been attached to Levson's earlier mining photographs, which are read as documentary images of exploitation and institutionalised racism and as showing cheap labour. The fact that the Free State Goldfield images were commissioned photographs might serve as part of the explanation. However, for us, a more significant aspect relates to the actual continuities between the sets of photographs. The similarities between the earlier individual 'mineworker' photographs and the later commissioned illustrations of 'South Africa's new goldfield' are to be found in the photographs themselves - as highly stylised and staged 'portraits of some of the infinite variety of men' who are experiencing 'the loosening of tribal organisation and to the spreading of western influences for good or ill.'67Both are sets of images rely on similar tropes, homologies and appearances: the Native in transition of custom, environment, locality, dress, practice and identity. The two sets of photographs are also linked in a vision and a visual or scopic continuity encompassing progress and development, from the images of 'uplifting humanity' in localised mine-compound moments and periods of western 'travail' and 'transition', to the imaginings of consolidating the 'tribal' within the spaces of humane mining labour modernities.

The differences between the sets of photographs are not to be found in their images, their commission, their content or their visual codes, but rather in the ways they have been archived, catalogued and represented. The association given to the first set of photographs and narratives of social documentary, resistance, and 'the real' as opposed to the 'propaganda' meanings attached to the commissioned and managed later Anglo American images make this distinction and produce different histories of meanings for the photographs. However, we suggest that highlighting the 'archival' making of these distinctions may be more important, for both establishing particular meanings as History and the real and also for denying the ideological 'native' represented or contained in the images. Because the earlier images are archived as the real of social history, they are more readily highlighted as part of a problematic iconography of social realism within this historiography itself.

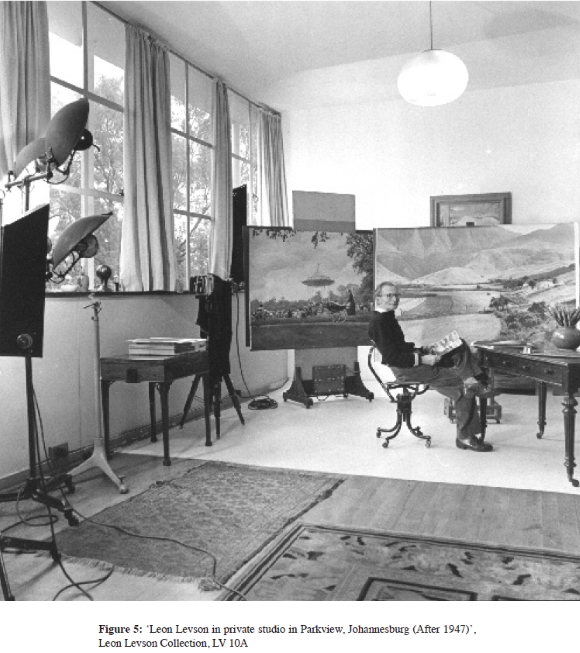

In 1954 Levson held a further exhibition, this time in the private studio of his Parkview home, entitled 60 Photographs of Italy. Eli Weinberg, writing in Jewish Affairs, described it as capturing 'the living mood of a country and its people,' while the Rand Daily Mail described it as 'views of Italy, angled with vision and humanity.'68 In the same year Levson contributed contemporary images to Copper Cavalcade: 50 Years of the Messina Copper Mine, an official commemorative publication, which sought to demonstrate the 'unswerving loyalty' of employees in an 'especially happy and contented community in which our people can live full and happy lives.'69 This apparent tension between Levson the social documentary photographer capturing humanity's 'living moods', even in Italy, and his commissioned work, here of Messina Copper Mine, further elaborate an important aspect of the correspondences of Levson's photographs. For what the images hold, albeit ambiguously - as they must - is a set of meanings and 'quotes' about History's 'Native futures' within a clean, ordered and structured ideal of the compound and the township. Here, separate, but 'not forgotten', work, leisure, skill, housing, health and education, as well as family, locality and movement are imaged through landscapes of desire and dignity. Appearances both 'distinguish' and 'join' events.70

So, as we return to the migrant photograph with which this paper began, here is Leon (and Freda) Levson's own commentary:

the trains trundle them thence to disgorge them, raw blanketed, in beads, with huge ear-ornaments and strange head-dresses, alternating between gaiety and timid apprehension, in Johannesburg, city of gold, and they walk with the long, easy stride of the veld among the sky-scrapers, old iron-balconied and fashionable shop-windows, dodging the unfamiliar traffic monsters until the mine compounds swallow them for the term of their contract.71

Encountering Levson's Natives in the photographic archive

What happens, when sitting together in a cluttered, busy and cramped space in the Mayibuye Centre, looking at the massive archive of Levson photographs? We start hesitantly, looking at select, and often multiple, copies. Later we progress to contact sheets. We find, relatively quickly, known and public photographs: the migrants, the street photographer; others less familiar and some unexpected, like a portrait of General Louis Botha taken in 1914. As we go through the photographs we try to match image to exhibition and caption. At other times we are simply struck by the image - by looking and by the possibilities in the appearances. A range of questions also begin to intrude: about the collection and its ordering (or dis-ordering), about the subjects and commonalities in the images, as well as about particular photographs, localities, individuals and photographic intent. In many respects, Levson's photographs - and his journeys - were defined by these locational contexts. Following Solomon-Godeau, we became aware that Levson's individual documentary project needed to be explored more thoroughly in order to '"speak" of agendas both open and covert, personal and institutional,' that inform its contents. This meant we needed to excavate the 'coded and buried meanings,' and identify some of the 'rhetorical and formal strategies that determined the work's production, meanings, reception and use' as well.72

We also concluded, fairly quickly, that our impressions of Levson's photographs, gleaned from the Margins to Mainstream exhibition, the Workers Library and Museum and from published images, as in the Callinicos book, were selective, taken out of context and framed with a narrative at odds with what we were seeing in the collection as a whole. Rather, a different set of impressions cohered in these early stages and they have remained with us as initial defining gestures of the Levson collection as a whole. The first was that the arrangement of the collection - its cataloguing, captions and overall organisation - first by Freda Levson, and later by Gordon Metz and others of IDAF and André Odendaal, then of UWC, when he was in London in the late 1980s and early 1990s, negotiating the 'return' of IDAF materials - serves explicitly to locate Levson within a 'resistance' framework. The first photographs archived in the collection of the Mayibuye Centre in the early 1990s were of "Sofiatown" (entry 2), followed by Luthuli (entry 3) and Gert Sibande (entry 4). That these constituted the first encounter with the collection masked the fact that they were, with one or two less notable exceptions, the only 'resistance' photographs in the entire Levson archive. More broadly, this framed a series of questions about the archive, its inclusions, exclusions and its ordering which emphasised how it was already a visual historiography.

Secondly, we were struck by the extent to which the collection had black people as its subject matter. With the exception of some urban and white farming landscapes, pictures of the photographer and associated 'friends' and the portrait of Botha, there were only one or two other photographs in the collection in which white people were present. We concluded that, in a very important sense, it was the fact that Levson photographed black people, and that the collection is made up of these images of almost exclusively black subjects, that served to define him as a social documentary and 'oppositional' photographer. This was so in spite of the overwhelming body of photographs that contradict the legibility of this connection.

The third impression we formed in looking at the images/appearances of black subjects in the photographs was that it was the exceptional image that was both used and displayed as representative of the Levson collection. In other words, it was much more the 'unusual photograph' that came to constitute and construct 'real' meanings and images of the past and which simultaneously placed Levson within both an 'oppositional' and a social history framework. And it was these unusual images that gave Levson a position as one of the founders of a social documentary photographic tradition in South Africa. At the same time, we began to articulate a suggestion that these images were only exceptional or unusual when viewed from the perspective of the very framework they helped constitute. Read differently they were much more expressive of correspondences with the majority of Levson's photographs.

The TJ motor car - stopped on the dirt road; the mission station - St Agnes, Ezenzeleni Mission, All Saints Mission, Adams, Kambula, St Cuthberts, St Matthews; the store - Port St Johns, Nqutu, Nkandla; the school - Healdtown, Fort Cox; the hospital - Charles Johnson Memorial (Nqutu), the settler farm. A man with a camera. Woman with pot; woman outside store; woman with bundle; men in blankets; man in European dress; woman in blanket with pipe; women with firewood; man with monkey puzzle hairdo. Kraal; kraal with tree; Zulu chief's kraal; young men in beads; young men in skins with sticks; old women with pipes; landscapes with kraals; abakweta dance-women and skin; the chic witch-doctor; dyeing and weaving; landscapes with huts; girl with pot; windswept landscapes with huts, woman and man on horse; huts with graves; boys and girls in white clay. The compound, the Manager's garden; the street and the reformatory; the NAD: Orlando Squatters Camp, Tobruk Squatters Camp, Sofiatown, Pimville, Orlando, Consolidated Main Reef, Malay Quarter, Shantytown. Here, man with camera accompanied by Michael Scott, by Rev Theophilus, by Father Superior, by the Mine Manager: scenes in the compound; Miner in a Hat; 'Black Cavalier'; 'Wild Willie'; 'Breeze Blocks' scenes; scenes and portraits, 'with Zulu woman newly arrived', 'Fish & cheaps', railway queues, gambling and washing, scenes and portraits, Sophiatown wedding, children striking tents at play, dancing on the mines.

These captions of the extensive photographs, the exhibitions given form and structure, and selection and focus through Meet the Bantu, and the wider organisation of the collection in field-trip categories (like Zululand, 5-20 June 1946) after an opening 'General' section, shape an apparent depth of focus and immersion in all the localities of 'the Bantu', from the Reserves, through the Protectorates, to the mines, locations and 'shantytowns.' They all generate a kind of completeness, a totality that is read as a visual encyclopaedia of 'Native Life' in the 1940s in South Africa.

This encyclopaedic visual register, seen as an inventory of native life at the time because of its scope and scale, and because of its apparent wide-ranging subject matter, seems both to reflect and to preserve this moment in time. Comments on Levson's photographs almost unfailingly refer to the ways that they seem to capture, or hold the moment of the 1940s, a moment somehow 'before' what was to follow. The apparent combination of this inventory and this marking of time serve to accentuate the associations between Levson's photographs, history's absences of inventories, images and voices for subaltern lives and his emergence and recognition as filling that gap through his photographs. In this sense Levson's visual registry has increasingly come to be seen and read as irrefutable, as evidence of the reality of black life in this period. In this way all the Levson photographs acquire a specific authenticity that is incontrovertible, as the most complete single photographic quotation of black social life available. Looking at the photographs, though, revealed a much more ambiguous reading. We were struck by the ways that the photographs often implied a fascination and a delight in the act of photographic representation itself. As Levson sought to fix and register a perceived reality into the two-dimensional space of representation, both genres for photographing natives - art photographer and portrait photographer - visibly come into play.

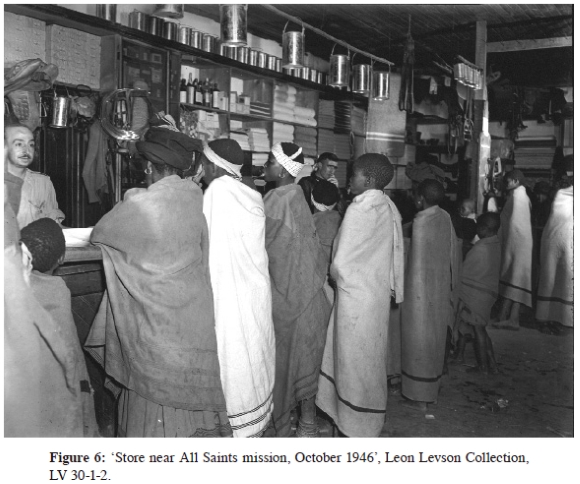

Levson sought photographically to construct the real space of the Reserves as intensely African - and as tribal.73 The mission, the store, the farm, the fence, the motorcar, the Recruitment vehicle, the queue are all intrusions onto the older surfaces of the kraal, the blanket, the initiation, the cattle, the field. While intrusive, it is in these camera spaces that different lines of vision in terms of Levson's appropriate past and future cohere. Based at mission station, store or hospital, Levson both proceeds forward from these sites into a photographic tribal past, and returns to photograph them as places of western influence and change. It is here where whites are present and it is here - on the shelves, in the doorways and on the operating tables - that the signs of 'western civilisation' are displayed.

Further afield, in portrait, in ceremony, in recline, in movement and dress, the camera frames the signs of the tribe, the country, the kraal, with pot, with pipe, with beads, with dress; making clay, mats, beer; fetching water, wood; threshing, thatching, eating, ploughing, dancing. One of the early photographs in the Meet the Bantu exhibition, 'Kraal still life' captions these lines of vision well, as the artistic delight of representation for Levson merged with the 'still life' of an ethnographic genre, with more than an echo of A.M. Duggan-Cronin.

In one respect, then, Levson the 'Reserve photographer' produced a range of images that fits loosely into an idiom that Christopher Pinney has called a 'salvage paradigm.' Pinney describes a 'salvage' paradigm as one where 'fragile' and 'disappearing' communities had to be recorded - and one that therefore has dominant scientific and curatorial imperatives and where an 'aesthetic of primitivism' is most apparent.74 While Levson moves his scope from the landscape of the kraal, through 'first contact' to 'the future', that future is one where the 'primitive charm and dignity' of the 'unsophisticated African' was by and large not figured or imaged in the church, school and state.75 The 'spatial immediacy and temporal anteriority' with the photograph being an 'illogical conjunction between the here-now and the there-then'76 establishes a set of visual meanings about the Reserves that locate a tribal past and kraal belonging to Native/Bantu identity as the most desired and real. In addition, Levson continues the tradition of 'environmental portraiture' 77 within this 'Reserve photography'. Put schematically and in summary form, the homologies between 'sitters' and pipes, beads, dress, and other background signs are drawn together to constitute signifiers of collective tribal and native identity and behaviour.

Alongside this 'Reserve photography', the 'contact zone' of the city drew Levson's camera into a form of 'reform photography'. Here in an 'alien environment', the shackyard was photographed against Orlando 'where some of the houses were nicer ... we showed how people lived if they had decent homes,'78 or where poverty, overcrowding and squalor required the presence of reformatory and the 'reform' of school, education, health, labour, and vocation. Mines and compounds feature as transitional zones - between the break-up of tribalism and the contact of cash and prestige, the 'wanderlust of youth' and the 'wonders of the life of the white man.'79 These are imaged as relatively stable, managed and liminal spaces of transition. Reform lies, not in eradication, but in the extension of the image of the commissioned compound photographs highlighted earlier. In the mining photographs tribal homologies abound - blankets, craft, eating, dress, posture, gaze, adornment, while in the shantytown photographs a more powerful homology of the 'shack' with native urban living and tribal expression in an uncontrolled environment is suggested.

But, perhaps more significant is the way that the subject matter of Levson's of 'urban photographs' almost instrumentally in and of itself constitutes its appropriate past and future, and its meaning within the discursive space of the Reserve and the tribe. In many respects the subject of the photograph - 'the Native' or 'the Bantu' - and the rhetoric of the image constituted by this given subject, conferred these meanings and histories. This was, after all, a series of photographs where the 'Individual Studies' camera group showed:

Zulu women with the red coil symbol of married status ... playing the "imVîngo", a single-string bow with gourd resonator, an instrument common to many tribes, wearing ear plugs ... and other articles typical of tribal attire. The Zulu are noted for their beadwork on snuff-boxes for necklets and waistbands. The Bechuana make fine karosses. The Basotho delight in brightly coloured blankets. The Xhosa and the Pondo of the Ciskei and Transkei also love blankets which the Xhosa dye with red ochre .... In the Transkei the women love their long-stemmed pipes made of wild olivewood and other hard-woods.80

'The Mines' group of photographs went on to picture 'the wide variety in Bantu physiognomy ... indicated in the series of individual camera studies. Though of the Negro race, there is a strong admixture of other strains, including the Hamitic in the Bantu-speaking peoples.'81 'The Townships' section imaged Natives as 'nature-viewed-through-a-temperament model'82 where

primitive imitations of European coffee-stalls and shops are often seen.... Gone is the picturesqueness of the out-door Reserve setting once the Natives are absorbed into an industrial and commercial economy.... With lack of housing goes also lack of recreation grounds, lack of schools, lack of enough wages to buy food, lack of responsibility and most other things which go to make an ordered civilised urban society. Many thousands of urban Natives live in what has been called a "moral No-man's land".83

It is these same photographs which were stamped 'with the patent of real-ism'84 at the time when exhibition-goers were invited to 'Meet the Bantu', and subsequently, as social documentary and as a vital index of social history. It is appropriate at this point to ask, as does Solomon-Godeau, whether the place of the documentary subject as it is constructed for the more powerful spectator is not always, in some sense, given. Is it not 'a double act of subjugation: first in the social world that has produced its victims and second in the regime of the image produced within and for the same system that engenders the conditions it then re-presents'?85 For it is clear to us that particular tropes are visible in Levson's photography that consist of the depiction of the subject and the subject's circumstances as a pictorial spectacle targeted for a different audience and a different 'race' and that dominant social relations are inevitably both reproduced and reinforced in the act of imagining those who do not have access to this means of representation themselves.

This article has begun to show the process whereby the photographic work of Leon Levson, through selection, archiving, distribution, captioning and recaptioning was appropriated into a visual history of the real conditions of social life of South Africa just before apartheid. This appropriation has been confirmed in the regular appearance of Levson's images in exhibitions, posters and publications which seek to depict the social conditions of black people in South Africa. This transfer of genre and shifts in meaning from the paradigm of 'native studies' to that of African agency occurred in the ritualised and performative settings of resistance archives. This chain of archival settings began with IDAF in exile in Britain, and its work of political solidarity and propagandist media around the South African liberation struggle. It was carried on in the institutional location of the Mayibuye Centre at UWC in Cape Town in the 1990s as part of the recovery of a lost heritage of black social history at the Centre itself and in other museums that drew on its archival meanings. From 2000, these interpretations of Levson's photographs were incorporated into the domain of national heritage. The archive of the Mayibuye Centre was formally incorporated into the Robben Island Museum, which had been created in 1997 as the first national museum of the new nation, in the setting of the island prison themed as the birthplace of reconciliation out of the 'triumph of the human spirit.'

1 This paper emerges from research conducted for the NRF-funded Visual Histoiy Project based in the Histoiy Department at the University of the Western Cape (UWC). It has benefited from comments at seminar and conference presentations in Cape Town, Atlanta and Washington and from the support of members of the UWC Robben Island Museum Mayibuye Archives Joint Working Committee. We would like to thank David Goldblatt for his encouraging comments and Graham Goddard, Audio-Visual Officer of the UWC Robben Island Mayibuye Archives (formerly known as the Mayibuye Centre for History and Culture) at UWC, for sharing his knowledge of the Leon Levson Photographic Collection. Responsibility for the arguments in this article remains ours.

2 This photograph by Leon Levson formed the basis of a 600 x 420 mm poster displayed to advertise the exhibition, and was also used for the postcard which served as an invitation to the exhibition's opening. While the title of the exhibition was advertised as Margins to Mainstream on the poster, it was also presented as From Margins to Mainstream on the invitation.

3 André Odendaal, 'Let it Return!', Museums Journal, April 1994; On Campus, Vol 3, No 19, 21-27 July, 1995; Mayibuye Centre for History and Culture, Fourth Annual Report, 1995.

4 The exhibition curator was Gordon Metz, who used to be based at the Mayibuye Centre, while Emile Maurice, then of the South African National Gallery had been seconded to the project as consultant and editor. Graham Goddard did the picture research and printing of photographs.

5 See 'The Worker's Library and Museum Presents Kwa 'Mzilikazi': a Photographic Exhibition on the Migrant Labour System' (Poster, Worker's Library and Museum, 1997). The exhibition was researched and designed by Lucky Ramatseba.

6 These observations are drawn from a visit to the Lwandle Migrant Labour Museum, 10 March 2000.

7 G Metz, 'South African Social Documentary Photography after Apartheid: The Struggle for Memory, Meaning and Power', in Bending Towards Freedom: Conditions and Contradictions in the (Post-) Apartheid Society, (Unpublished manuscript of papers presented at Umeá University, 7-8 August 1998), 2-3. This symposium was held in connection with the Exhibition, Demokratins Bilder: fotografi och bildkonst efter apartheid/Democracy's Images: photography and visual art after apartheid, which was held at BildMuseet, Umeá University, from 6 September to 8 November 1998. The exhibition has subsequently been on show at the Uppsala Konstmuseum (November 1998-January 1999) and the Borás Konstmuseum (March 1999-April 1999) in Sweden as well as at the Johannesburg Art Gallery in South Africa (November 1999-March 2000). See the Catalogue, Demokratins Bilder: fotografi och bildkonst efter apartheid/ Democracy's Images: photography and visual art after apartheid (Umeá, 1998).

8 G Metz, 'South African Social Documentary Photography', 2-3.

9 Ibid., 3-4.

10 Ibid., 4-5.

11 Ibid., 5.

12 This, of course, raises questions about social documentary photography and debates about its history as genre.

13 G Metz, 'Out of the Shadows' (text accompanying exhibition, Margins to Mainstream); "Leon Levson" (biographical text accompanying the exhibition).

14 A Solomon-Godeau, Photography at the Dock: Essays on Photographic History, Institutions, and Practices (Minneapolis, 1991), 170.

15 L Callinicos, A Place in the City: The Rand on the Eve of Apartheid, Volume 3 of 'A People's Histoiy of South Africa' (Johannesburg, 1993), 22.

16 See Luli Callinicos, A Place in the City, 101, 15, 29, 47, 33

17 L Callinicos, A Place in the City, vii.

18 L Callinicos, A Place in the City, vii. Our emphasis.

19 Leon Levson Photographic Collection, Compiled by Andre Odendaal (Mayibuye Centre Catalogues No 1, Mayibuye Centre for History and Culture, University of the Western Cape, 1994), 37. In 1990, just before the formal establishment of the Mayibuye Centre, a printout and compilation of this catalogue was brought out under the name, The Leon Levson Photographic Collection: Catalogue and Background Material. The 'Johannesburg Photographer' photograph graced the covers of both editions.

20 Leon Levson Photographic Collection, 37.

21 Freda Levson, 'Notes on Leon Levson's work for Mr Toms', Leon Levson Photographic Collection, 47.

22 Leon Levson Photographic Collection, 40-1.

23 Cape Times, 13 September 1943.

24 Cape Times, 13 September 1943.

25 Leon Levson Photographic Collection, 45, 47.

26 The Star, 15 December 1943.

27 The Argus, 13 September 1943.

28 For this unreferenced and undated newspaper report, see Leon Levson Photographic Collection, 65.

29 See Levson's exhibition statement on the invitation to the preview of Monoprints, which was held on 26 November 1945; reproduced in Leon Levson Photographic Collection, 69.

30 The Star, 28 November 1945.

31 The Argus, 13 September 1943.

32 Prebble Rayner, 'Behind the Lens', in Trek, 24 September 1943. At this time, Trek was a leading forum for radical cultural and political expression. Prebble Rayner was a regular commentator on artists, exhibitions and art institutions in the pages of Trek.

33 Cape Times, 11 September 1943; 13 September 1943.

34 Allan Sekula, 'The Body and the Archive', in Richard Bolton , ed., The Contest of Meaning: Critical Histories of Photography (Cambridge, MA, 1989), 347.

35 'Leon Levson Recollects', 10 April 1961, in Leon Levson Photographic Collection, 45.

36 Freda Levson, 'Notes on Leon Levson's work for Mr Toms', in Leon Levson Photographic Collection, 48.

37 Freda Levson, 'Leon Levson, 1883-1968', in Leon Levson Photographic Collection, p 41. Note how nomenclature and the language idioms of racial classification had changed after 1968.

38 'Meet the Bantu: A Story in Changing Cultures' (Exhibition Brochure, Foyle's Art Gallery, 1947) in Leon Levson Photographic Collection, 74.

39 'Meet the Bantu', 75.

40 Ibid.

41 'Meet the Bantu', 75-76.

42 'Meet the Bantu', 76.

43 Some of these reports are reproduced in Leon Levson Photographic Collection, 102-103.

44 Leon Levson Photographic Collection, 171-176; 181.

45 Lord Hailey, for example, had been Governor of the United Provinces in India before taking the Directorship of the African Survey initiated in 1935 with funds made available by the Carnegie Corporation of New York and the Rhodes Trust. See Lord Hailey, An African Survey: A Study of Problems Arising in Africa South of the Sahara (London, 1938).

46 'Meet the Bantu', in Leon Levson Photographic Collection, 74; 101.

47 'Where Are We Going: Camera Studies by Leon Levson' (Exhibition Brochure, Gainsborough Galleries, 1948) in Leon Levson Photographic Collection, 172; The Star, 26 July 1948; Rand Daily Mail, 4 August 1948.