Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Kronos

On-line version ISSN 2309-9585

Print version ISSN 0259-0190

Kronos vol.31 n.1 Cape Town 2005

ARTICLES

Seeing the Cedarberg: Alpinism and Inventions of the Agterberg in the White Urban Middle Class Imagination c.1890-c.1950

Lance Van Sittert

Department of Historical Studies, University of Cape Town

Alpinism in Africa

Recent scholarship has convincingly argued for the 'alpine' as a frame of reference for apprehending otherwise incomprehensible African environments and the special place of snow-covered mountains in the European imperial imagination in Africa as sites of pilgrimage and transcendence.1 This scholarship, like that on travel writing of which it is a subset, however, is almost entirely based on the writings of itinerant European sojourners and pays very little attention to settler landscape texts.2 That the latter are substantially different, constituting 'small traditions' mapped onto the specific geographies of each local constituency's landscape and politics, is the burden of this paper in its discussion of three settler traditions of narrating the mountain landscape of the Cedarberg over the period from circa 1890 to 1950.

The first, colonial alpinism, most closely approximates the generic 'imperial' type apprehending the Cedarberg through the borrowed eyes of English alpinism but measuring its resident black and white peasantries not for their traditional authenticity, but for 'progress' towards modernity. The second and third are 'indigenous' or 'indigenised' settler traditions, here called Anglo alpinism and Afrikaner alpinism, the former seeking in the Cedarberg a pre-modern refuge from progress and the latter to reconcile itself to the cost of modernity on the pre-modern Dutch backveld.

(Re)Discovering the Cedarberg

The discovery of the Cedarberg by the Cape Town middle class was contingent upon two fundamental revolutions, the one ideological and the other practical. Romanticism provided the former, transforming the way the European bourgeoisie, first at home and then in the diaspora, viewed mountains.3 The Alps were the single most important site in Europe for the collective re-imagining of mountain landscapes and the alpine aesthetic was extensively exported to the African colonies.4 The combustion engine furnished the concomitant practical revolution, the automobile transforming the bourgeois vacation by individualising the annihilation of distance by time and so vastly expanding the recreational hinterland available to the urban bourgeoisie. The interwar 'discovery' of the Cedarberg by the Cape Town middle class was a local manifestation of these two intersecting global revolutions in bourgeois perception and travel.

Alpinism was formally constituted at the Cape in 1890 with the formation of a Mountain Club in Cape Town in imitation of the British Alpine Club and actively promoted through the Club's journal, colloquially referred to as the 'Annual' by members.5 The majority of the membership, however, harboured only parochial ambitions to secure middle class access to the 'G[rand] O[ld] M[ountain]' - Table Mountain - during a period accelerated enclosure of private and public land in the colony.6 A minority, seeking to actively embody the virile Rhodesian imperialism of their day, looked beyond the GOM and deemed 'every peak from here to the Pyramids' within the ambit of the Club. 7 They launched the first mountaineering expedition to the Cedarberg in the winter of 1896.

The party of three mountaineers, two members of the newly formed Cape Town Mountain Club and a visiting member of the English Alpine Club embarked on the round trip by rail, wagon and foot, relying on a network of anglo(phile) 'gentlemen' in the towns en route to provided intelligence, transport and accommodation and the presumption of similar services from Dutch farmers in the intervening countryside.8 Travelling first by rail to Ceres Road station (Wolseley), then by wagon via the Gydo (Mitchell's) Pass and Cold Bokkeveld into the Cedarberg, they spent two days climbing and then walked the twenty-five miles from the Rhenish mission station at Wupperthal to Clanwilliam from where a cart returned them via the Piekeniers (Grey's) Pass and Porterville to the railway at Piquetberg Road and so back to Cape Town. They had been away fully fifteen days.

The expedition was written up in the form of a diary by one of their number, the forty-three year old Secretary of the Standard Bank, George Thomas Amphlett, not for the Club Annual, but the Cape Illustrated Magazine, a publication that better reflected the confident new imperialism that informed the excursion.9 In the process Amphlett created a template for writing the region which his many imitators after 1918 adapted and employed for half a century down to the 1950s.10 Amphlett translated the English Alpine Journal's 'mountain writing' genre into the colonial context to produce a Cape colonial alpinism which retained the metropolitan variant's preoccupation with pre-industrial peasantries and wilderness, but as affronts rather than antidotes to modernity.11

In its partisan advocacy of progress and forensic eye for backwardness, colonial alpinism drew firstly on the long tradition of metropolitan scientific travel writing on the Cape going back to the late eighteenth century.12 The other narrative tradition with which Amphlett hybridised English alpinism was a more parochially colonial one, intimately familiar to him, the bank manager's report. All Standard Bank branch managers were required to submit an annual report on the state of the economy in their region and, as a bank employee, Amphlett would have written and read these as a matter of course over many years of his professional life.13 When he came to travel through the backveld in 1896 it was with a banker's practiced eye for industry and opportunity that he surveyed the landscape; noting oil and saltpetre exploration and the potential for export apple production in the Cold Bokkeveld; applauding the labours of missionaries and foresters in founding a tannery, school and plantation in the Cedarberg and decrying the Dutch gentry's failure to either grasp opportunities or manifest any industry in their pursuit.

Although by far the greater part of their time was spent travelling to and from the Cedarberg, Amphlett placed the two days spent climbing Tafelberg and Sneeuwkop squarely at the centre of his narrative. In doing so he emphasised three themes which together came to constitute the core discourse of colonial alpinism and its later national variants: navigation, natives (both white and black) and nature (or landscape).

The pioneering party presumed upon the local population not only for its transport, labour and supplies, but also for information about the best routes to and up the Cedarberg. Local knowledge tested in the field was repeatedly found to be inferior to middle class 'mountain instinct' and quickly rendered redundant by the new hybrid knowledge contained in Amphlett's written account.14Henceforth, the middle class abroad, whatever its reliance on the local population for its creature comforts, would be self-sufficient in its knowledge about the topography. That the party carried aneroid barometers to accurately measure the heights of the main peaks underscored this process of overwriting local with scientific knowledge of the landscape.

Amphlett's account treated the Dutch population not as allies, but objects of anthropological curiosity, in short, natives who were to be scored on the same test of modernity as the blacks and to the same end; to confirm their primitive, backward otherness. The Dutch repeatedly failed the acid test of industry, even in those rare instances when they embraced the market. Nor did they redeem themselves as pre-industrial patriarchs more often refusing than extended the hospitality traditionally granted travellers of substance abroad in the countryside. His treatment of the other kind of backveld natives - the black, or in the Cedarberg case bastaard or coloured, labouring class - was equally ambiguous, their provision of both hard manual labour and intelligence confusing in the customary master-servant relationship.

Amphlett's belief in imperialism's civilising mission, however, required proof of its success in the form of natives transformed into Englishmen. While he attested to many aggregate examples from the party's visits to various mission outposts, the most striking individual example, and the narrative's most arresting figure, was the half-caste mountaineer 'Villoen'.15 A bastaard mission station inhabitant, he farmed at the foot of Tafelberg on his own account in a settlement (Ezelsbank) otherwise occupied largely by women whose men were out working for white landholders.16 He put the party up in his house, in the room usually reserved for the missionary, and accompanied them on their climb of Tafelberg which 'he had himself several times previously unsuccessfully attempted'.17When they abandoned the climb on account of the weather and discovered one of their number missing, Villoen was instructed to remain, and on no account come down without the "young baas"'. Shortly after arriving back at the farm the missing mountaineer returned to announce that he and Villoen had by 'mutual assistance' '"taken" the virgin peak'.18 Amphlett reported that 'there were no bounds to the enthusiasm of Villoen, whom we heard recounting his adventures by the kitchen fire, to the wonderment of the rest of the settlement'.19 The success of the middle class mountaineer and the missionaries' prodigy provided a vignette vindication of a progressive colonialism that raised up the native as full partner of the Englishmen in the toil and triumph of beaconing the mountaintop.

The only natural feature that Amphlett commented in an otherwise thoroughly inhabited landscape were the mountain summits and in particular that of the Tafelberg. This was not only the 'reputed unclimable piece de resistance', but also the namesake and in appearance striking facsimile of Cape Town's GOM.20 The sense of familiarity was reinforced by the cedar tree, which doubled for the silver tree on Table Mountain, in symbolising, through its beleaguered endemism, the uniqueness of the locale.21 While Table Mountain had been irreparably 'vulgarised' and feminised, the Cedarberg Tafelberg was the GOM restored to a prelapsian state of nature and fit target for manly endeavour.22 That it 'commanded' the GOM in its 'range of vision' seemed only appropriate to the montaine imperialists of the Amphlett party who, looking south, reported 'Last, but not least, Table Mountain, our own Tafelberg, loomed up in the opposite direction at the extremity of a long gap in the mountains, as if the latter had specially opened ranks to do it honour'. 23

Amphlett's fulsome account failed to spur the Cape Town middle class to the feats of montaine imperialism he advocated. Rhodes' bungled coup attempt against the South African Republic at the end of 1895 had already made the Cape backveld an inhospitable environment to English travellers (as Amphlett's own hostile reception by Dutch farmers attested) and the South African War put it off limits to all except military personnel.24 Indeed it was only a quarter century later that the Cedarberg became part of the urban bourgeoisie's recreational hinterland, but when it did, the by then deceased Amphlett's account provided the colonially ground race-tinted alpine lens through which the mountains were (re)seen, guiding interwar mountaineers paths and shaping their perceptions just as it had once guided and moulded his own.

Ironically, the South African War, while it closed the Cedarberg to mountaineering, also improved the region's transport infrastructure. The railway, which had been stalled at Malmesbury since 1877, now moved rapidly northwards to Eendekuil in 1902 and Klaver at the start of the First World War.25 With the railway came the provision of a bus service linking sidings with neighbouring towns. That from Graafwater siding to the town of Clanwilliam, 24 miles away, commenced in 1911 and this, together with the establishment of a forestry station in the Jan Dissels Valley at Algeria in 1896, shifted the centre of gravity in the region decisively to the west, making Clanwilliam the new 'natural approach' to the Cedarberg.26

As a result of the transport revolution's reorientation of traffic to the western approaches of the Cedarberg the forest station at Algeria became the preferred 'base of operations right in the heart of the mountains' and the resident forester the provider of transport, accommodation, labour and guiding to mountaineers.27 The foresters' construction of roads, fire belts and huts also opened up the Cedarberg, as it had earlier done Table Mountain, for middle class recre-ation.28 'These paths ... save the climber much expenditure of energy and enable him to gain the upper levels of the mountains with a minimum of effort'.29 The foresters further cleared fire belts which made for 'pleasant and easy' access to the mountain summits by middle class mountaineers (as did local 'Buchu farmers' practice of annually firing the slopes).30 Lastly the construction of forestry department huts at outlying points from Algeria and establishment of satellite stations also enabled middle class mountaineers to climb over a wide area by moving their base camp every few days.

The coincidence of state railway building and forestry alone, however, was insufficient to trigger an urban middle class rush on the Cedarberg. This required a revolution not only in public works, but also private transport, provided by the automobile. Automobile ownership only took off in Cape Town during the interwar decades, more than quadrupling from 7,000 in the mid-1920s to 30,000 on the eve of the Second World War.31 The poor state of Cape roads severely restricted the reach of the automobile outside of Cape Town and quickly destroyed vehicles that ventured too far from the city.32 Despite this, the automobile redefined urban bourgeois leisure time in the interwar period opening up a vast new recreational hinterland and making the 'the country trip' one of its regular features.33

'Motorneering has rendered possible that joy of joys the unplanned trip. Prior to the adoption of the motor car as a means of transport, weeks of careful planning and much correspondence were necessary if the most was to be made of the usual short holiday. Trains run only at certain intervals and have a habit of depositing the mountaineer miles from his intended base, thus rendering necessary the services of the local cartage contractor and arrangements to be at a place on a certain date at a certain time as well as a rigid adherence to a carefully thought-out climbing time-table. The car has changed all this. The jumping off place is now the home town and all that is necessary is an acquaintance with the general geography of the region to be visited, together with a certain amount of driving and mechanical aptitude'.34

The motor car thus brought the Cedarberg within the ordinary ambit of the Cape Town Mountain Club. 'When we went there in the "old days,"' reminisced one in 1936, 'it took us just about twenty-four hours to get to Algeria Forest Station - and that only as the result of elaborate and careful pre-arrangement. There was the all-night train journey to Graafwater; transport to be found for the 24 miles to Clanwilliam; further transport to Kriedouw; and then a trek with pack donkeys for 10 miles, over a mountain pass 3,000 feet high, before the base could be reached. Now one can breakfast comfortably at home, hop into one's car with almost unlimited food and equipment and arrive at Algeria by lunch time'.35 The Mountain Club organised its first 'motorneering' meet in 1931 and the 'mixed motoring and mountaineering expedition' and the associated 'motorneer' or 'motor-mountaineer' became a staple of Club activity and literature.36 The car, unlike the train, allowed travellers to determine their own route and, by doubling as accommodation in a pinch, encouraged them to try those less travelled.37

Utilising the new means of public and private transport available to them and with Amphlett as their guide, the Cape Town middle class began to explore the Cedarberg in growing numbers after 1918. They came, however, not as Rhodesian imperialists, but as citizens of both a newly independent white nation state and rapidly industrialising city in search not of affirmations of imperialism and progress, but rather their antidote, an inclusive white nationalism and a pre-modern countryside in which the old social order of race and rank with its mutual obligations of paternalism and deference still pertained. Alpinism in this context yielded a new Anglo national variant of the Cedarberg as pre-industrial paradise.

Anglo National Alpinism

The quarter century hiatus in Anglo middle class exploration of the Cedarberg returned it to the realm of myth from which the earlier montaine imperialists of the Amphlett party had sought to redeem it a quarter century earlier and required its '[re]discovery' anew after World War One.38

Thus the first of the new post-war generation of Cedarberg explorers reported in 1922 that;

In Cape mountaineering circles, the Cedar Mountains might, until quite recently, almost have been described as semi-mythical. Little or nothing was known of them from a climbing point of view, and although we came across several people in Cape Town who had been to Clanwilliam, none of them could give us any information about the mountains. One even went so far as to express doubt as to whether we should find anything to climb'.39

By then two of the 1896 party were dead and the sole survivour retired from active climbing and the Mountain Club. Amphlett's Cape Illustrated Magazine account filled the lacuna in contemporary intelligence and firmed resolve to (re)discover the Cedarberg.40 Its status as the sole 'literature' on the topic, however, was soon usurped by the new generation's fulsome accounts of their own exploits published in the Mountain Club's Annual. While the Amphlett report's intelligence value was brief and it was soon eclipsed and forgotten, it had a much more enduring impact on the narrative form of the new generation's 'literature', which employed its diary format and mixed climbing accounts with social observation of the landscape and inhabitants.41

A significant number of mountaineers kept climbing diaries, which read, in their attenuated prose and preoccupation with daily logistics, like military officers' battlefield diaries from which they were in all probability descended.42 These private diaries provided the narrative framework and raw material for the expedition narrative written for the Annual or popular press and circulation among a more or less wider audience. Although only a very small number of climbing diaries kept by the more literary of the fraternity ever attained this exalted status, these often drew on the unpublished diaries of other expedition or Club members. The diaries, together with expeditions' increasing use of photography, functioned as mnemonics, each entry or image cuing a wealth of memories associated with the day or view recorded. In retrieving these memories they passed through the received filter of mountain romanticism which gilded their spare prose with the set of stock images of navigation, natives and nature derived from colonial alpinism. If the colonial and new national alpinism shared themes in common, the emphasis and attributions placed on them were significantly different.

The Annual accounts all actively promoted the Cedarberg as 'virgin ground' for 'Peak-bagging' 'untrodden summits'. 43 This was the old Rhodesian imperialist impulse retrofitted to a new nationalist context. Rhodesian Cape to Cairo imperialism's successive setbacks from the Jameson Raid, South African War and Union had forced its Anglo urban middle class supporters to retire to their Froudian island redoubt on the Cape Peninsula by the eve of the First World War.44 The Great War, however, tested and proved the new imperial nationalism espoused by the moderate Afrikaner generals, Botha and Smuts, and the Anglo urban bourgeoisie quickly rallied to its standard, ninety one members of the Mountain Club enlisting and nine dying in its active service.45 The war both won the Cape Town patriciate to the new nation state and reinvigorated its old imperialist impulses, the latter's quickening being further fired by Smuts' post-war donning of the Rhodesian mantel and promotion of a 'Greater South Africa'.46

The other wartime development spurring the Cape Town Anglo middle class' post-war exodus to the Cedarberg was the city's radical transformation by hothouse import substitution industrialisation.47 The old colonial mercantile class order was unable to contain or control the social forces unleashed by accelerated urbanisation and proletarianisation and found itself confronted at the war's end by an increasingly organised and militant urban proletariat disparaging of its paternalism and disinclined to deference. With threats and alarms of class war reverberating around them, the Cape Town patriciate sought in the Cedarberg, to adapt David Bunn's apt phrase, an 'enclaved paternalism' where the customary pre-industrial class order and due deference to race and rank still obtained, allowing the bourgeoisie to recoup its energy and sense of self.48 Not surprisingly, the Cape Town middle class sought to secure the same 'national park' status for the Cedarberg as that accorded the lowveld playground of the Randlords in 1926, but with markedly less success.49

Given that the underlying impulses to Cedarberg 'discovery' were provided by imperial and class war, it is perhaps not surprising that the all pervasive mixed-metaphor employed by the urban middle class in its narration was that of hunting-cum-military campaigning.50 Mountaineers launched a series of 'attacks' to 'subdue' and 'capture' their 'victims' from 'camps' on the plain, seeking out weaknesses in their 'defences' and occasionally being forced to retire 'defeated'.51 Success conferred ownership - 'our peak' - and 'command' over the surrounding countryside and was commemorated by the construction of a beacon or 'stone man', in imitation of the old astronomer surveyors, containing a 'record tin' in which were deposited 'our names inscribed in a piece of paper wrapped in cardboard'.52 In the case of 'virgin peaks' ownership also conferred the right of naming, subject to confirmation by the club's 'Peak Naming Sub-Committee', with members substituting the Cedarberg's 'unpronouncable local names' with ones 'simpler and more suitable for Club members' purposes'.53

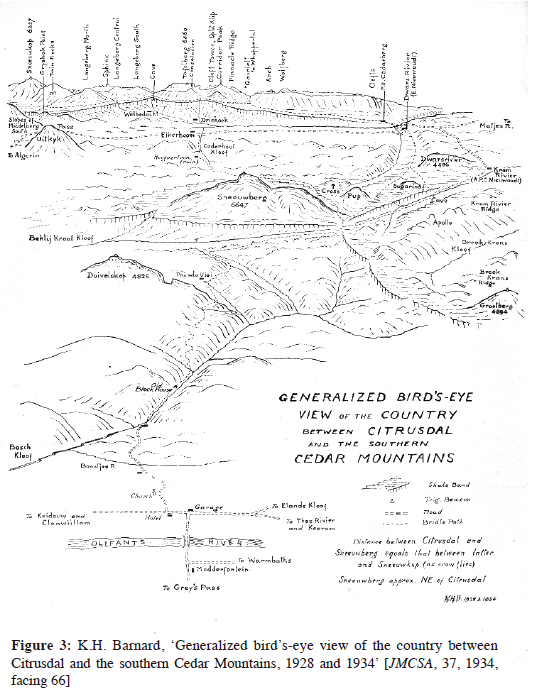

For all that they liked to style themselves as intrepid and self-sufficient explorers, the interwar mountaineering middle class were initially as dependent as the Amphlett party on 'local information' to navigate the mountains.54 As in the past, the humiliation of being 'put ... wise to ... features of the countryside' by locals, was tempered by the frequent errors revealed in such 'intelligence' by subsequent experience. 55 It also spurred the Club's 'mapping' of the Cedarberg.56 This was initially the primary function of the increasing number of expedition accounts published in the Annual and the cartographic representations that accompanied them were in a very real sense meaningless without the associated diary account to orientate the reader in the maps. The latter employed their own esoteric scale, orientation and topographic conventions and made no reference to one another. This did not matter so much while the Algeria forest station remained the sole gateway to the mountains, but once the number of alternative entry routes began to rise and the climbing area expand, as it did dramatically in the 1930s, the balance quickly shifted away from the diary account to the map and the Annual's Cedarberg 'literature' gradually disappeared" to be replaced by the standardised map.57

The interwar urban middle class' preference for the diary over the map also reflected its romanticism, harking back to the early modern tradition of scientific travel writers on the Cape and a time when the map was still largely blank, subordinate to the text and decorative rather than scientific.58 Imagining themselves to be the 'discoverers' of the Cedarberg engaged in literally 'putting the place on the map', they deeply resented any indication that its 'virgin peaks' were already integrated into a trigonometric grid.59 They thus harboured a particular and abiding antipathy towards the national trigonometric survey established in 1918 and whose 'surveyors ...seemed to have cleaned up the district pretty thoroughly'.60 The trig survey's practice of rudely overwriting the imperial impress on the summits, by replacing the 'stone men' cairn beacons erected under British rule with the 'cement "drain pipe"' markers of national overlord-ship, particularly rankled a mountaineering middle class who revered the early astronomer surveyors as the founding fathers of their sport and imitated their 'stone men' in marking their own summit conquests. 61

Together, the trig beacon and its product the survey map gave the lie to the middle class' claim of discovery in the Cedarberg by unambiguously revealing it to be not a frontier but known space falling within the ordinary cartographic purview of a modern nation state. By shunning both and instead privileging the diary account, drawing their own rough and ready maps and feverishly beaconing routes and whatever unmarked summits they could find in the Cedarberg the mountaineering middle class maintained the fiction of its own pioneering prowess and the Cedarberg as pre-modern frontier. These were necessary fictions to enable them to imagine themselves as citizens of the new white nation state and escapees from an industrialising city to a pre-industrial rural idyll. Such wilful self-deception was not confined to matters of navigation, but also extended to encompass the natives.

The urban middle class' increasing knowledge of the lie of the land in the Cedarberg was accompanied by a concomitant growing familiarity with its inhabitants. They, like their colonial predecessors, found the Cedarberg an inhabited landscape, which, in Leipoldt's evocative phrase, was 'kruis en dwars bevoetpad deur die boegoe- en basvergaarders'.62 The traces of its inhabitants were everywhere; from the lowland farms, footpaths, caves and makeshift bridges to the high summits where the always unwelcome evidence of surveyors' beacons was as often accompanied by irritating indications of nonchalant summiting by local farmers and labourers.63 As a result, romantic epiphanies inspired by the empty landscape of summit and plain were frequently interrupted by intrusive natives. Thus a party reconnoitring the headwaters of the Oliphants River with a view to 'putting the place on the map' in the late 1930s had their pioneer fantasy rudely disturbed when

Nearing our first crest we were astounded to hear bells and on reaching this were more or less dumbfounded to see a large flock of sheep and goats complete with father and three little girls driving them out to graze - and we'd been kidding ourselves that we were alone in the wilderness. Away to the north - on a broad saddle of shale we saw a small farm with fruit trees, garden and kraal. I don't know who was most flabbergasted - the man or us, anyhow we introduced ourselves to one Engelbrecht and unearthed the fact that his demesne rejoiced in the name of Drosters Gat, that he took his flock to the Karroo every winter and that our peaks had no names other than Witzenberg. This is bar none the most out-of-the-way farm I've ever struck in my experience.64

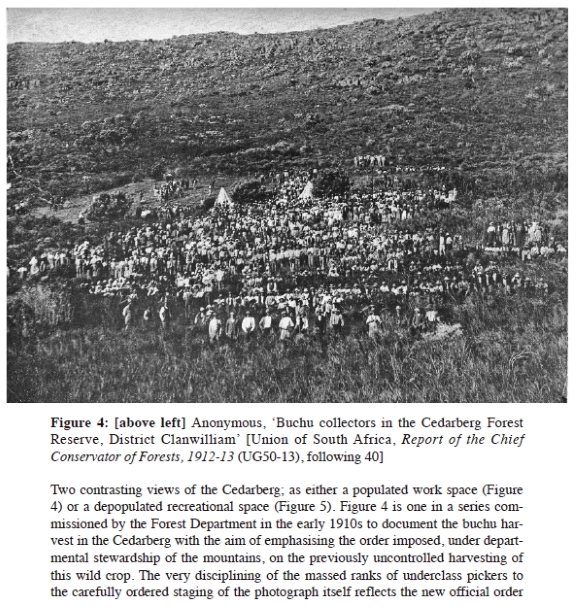

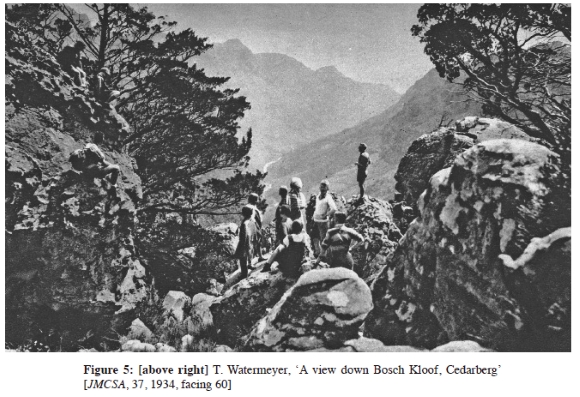

The Cedarberg forestry estate was also a major production site of indigenous cash crops and during the spring harvest, which coincided with the preferred middle class climbing season, the mountains were full of people. This was also true to a lesser extent throughout the year as farm and mission station inhabitants went about their business in the mountains. Thus a party excavating a cave at the head of the Bosch Kloof in 1928 reported that 'Citrusdal appears to be the chief "winkel" for the people on Nieuwehout's farms, and every day we saw shoppers as well as buchu-pickers using this convenient highway'.65 The striking thing about the Annual's Cedarberg literature then is the contrast between the populated landscape and its depopulated narratives. Away from the forest station and farm houses, the literature is bereft of all other human beings than the mountaineers themselves.

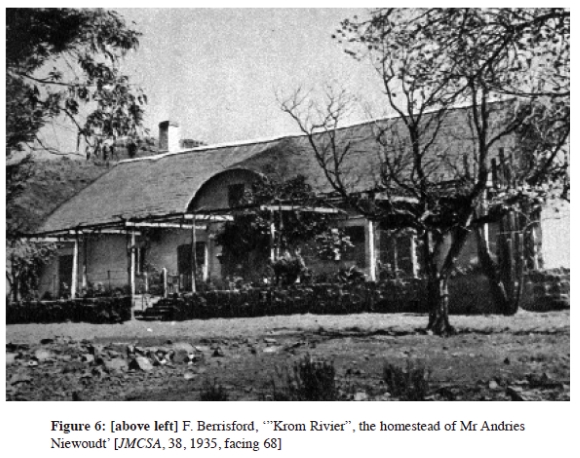

Colonial alpinism's image of the Dutch population of the Cedarberg as backward and hostile Boers scratching a living from the backveld was transformed after 1918 into one of Afrikaners as productive and prosperous farmers symbolised by 'Great tracts of land . under cultivation and . fine old homesteads built in characteristic Dutch style . surrounded with great oaks'. 66 This image had strong symbolic resonance for the Cape Town middle class, but as the artefact of ruin not the reality of functioning farm and in this, as so much else, the Cedarberg seemed to offer the pre-industrial Cape Peninsula restored to its imagined prelapsian splendour.67 The 'open-hearted hospitality' enjoyed by the interwar Anglo urban middle class abroad at these farms was also in stark contrast to that accorded the Amphlett party.68 'Permission to stop on the farm ... and . camp . on the werf under a great oak' was granted as a matter of course, but mountaineers were just as likely to be 'taken in' by farmers making 'sumptuous meals and feather beds ... the order'.69 By the late 1930s the Cedarberg's white farmers 'knew climbers and their ways' and middle class mountaineers took 'friendly farmers' foregranted as part of the experience.70

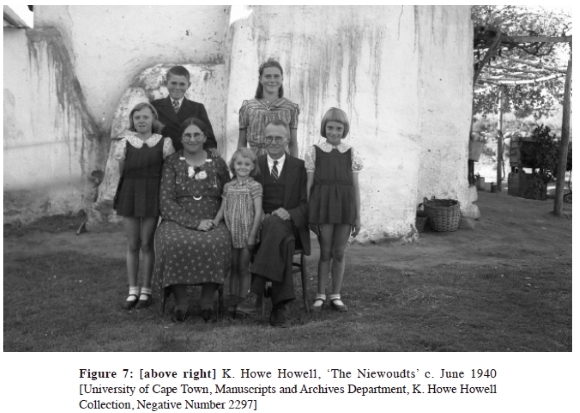

Increasing exposure to the backveld also left its mark on the Anglo urban middle class, most noticeably and superficially in the 'quickly expanding Afrikaans vocabularies' with which they peppered their accounts.71 While bilingualism was still a rarity in their ranks, the language of Anglo urban mountaineering itself was Afrikanerised with a slew of topographical terms, like 'kloof', 'bergen', 'krantz', 'riff', 'trek', 'vlakte' and 'plaat', entering the official discourse of the Annual, and thus general usage, in this period.72 Less perceptible, but more profound was the effect of fraternisation with the Afrikaans 'landed gentry'. This cultural exchange, always transacted at the farmhouse and generously lubricated with 'coffee and luscious bread and "wa-boom" honey', became a cliché of the Cedarberg experience in the 1930s.73 If colonial alpinism espoused a progressive imperialism and journeyed into the backveld in search of the native transformed into self as the ultimate proof of progress, Anglo national alpinism was a romantic rejection of progress and flight into the backveld in search of the self gone native as antidote to modernity. Under these changed circumstances, Villoen - tellingly demoted in the interwar literature to 'a coloured boy'74 - found his interwar facsimile in the Afrikaner farmer and 'boere-filosoof', 'Wit Andries' Niewoudt.75

Niewoudt and his wife, Spuytjie, became 'country members' of the Mountain Club and their farm, Krom Rivier (see Figure 7), an alternative base for Cape Town mountaineers in the southern Cedarberg, where the obligatory 'boys ... and ... donkeys' could be procured as well as a guide in the form of Niewoudt himself.76

Club members and their associates had a standing invitation from the Niewoudts to 'make Krom River their headquarters when visiting the Cedarbergen' and, one member testified, 'they will find such cheery hospitality and friendship there that "Good-bye" is said with a pang of regret', while another dubbed Niewoudt 'a prince of hosts'.77

Unlike Villoen, however, Niewoudt was magus not protégé, initiating his guests into his world rather than imitating theirs. The interwar Anglo urban alpinists, seeking an escape from modernity in the Cedarberg, imagined that at Krom Rivier they re-entered a simpler and more genuine pre-modern world and for many of them Niewoudt literally 'embodied' this other world; a 'man, wat net maar uit ons Suidwestelike wereld, uit van sy nog ongeskonde Kaapse landskappe kon gekom het' .78 A font of 'geestige boerewyshede, dikwels geniepsig', Niewoudt abhorred and attacked any and all affected urban artifice in his guests.79 'Mooimaakery, toneelspel van enige sort is gou-gou deur hom gestroop. En as die aanspraak verlee en sonder sy maniertjies daar staan, kon die gesels eers werklik begin'.80 To visit Kromrivier was thus to either voluntarily shed one's modern urban self or have it ruthlessly stripped away. It was also to enter a pre-modern feudal world.

Kromrivier was inderdaad in die vroeertyd toe ek dit die eerste mal leer ken het, nog feudale betsaansboerdery. Daar was oorvloed vir almal, ook vir die baie wat kom bergklim en sommer ook kom kuier het. Maar die kontantvloei was skraal: uit die paar lande se roltwak, die bietjie vee; ook uit die skool waargeneem deur Spuytjie, Andries se geliefde lewensmaat . Hier het sy vir die bruin kinders uit die ver staanplekkies en veeposte die basiese dinge geleer. En vir haar het hulle weeksdae in die kombuis en op die werf gehelp.81

Through the Anglo-Afrikaner Niewoudt, the Cape Town Anglo middle class was inducted into both this feudal white Afrikaner society and its history. '[T]alle Engelstalige stedelinge [het] hier [by Kromrivier] hulle eerste ware kennis van die plattelandse, die nog feudale Afrikaner opgedoen .In Kromrivier se pragtige ou opstal - tot betreklik onlangs nog in die volksboustyl - het stad en land mekaar op 'n unieke wyse gevind, baie verdure bane oopgemaak'.82 Indeed, by the end of the 1930s, the prospect of '"heerlike koffee" drunk in thick-walled, thatched-roofed houses' was as much a part of the Cedarberg experience for the Cape town middle class as the mountains.83 Boasted one,

This was more than a mere climbing trip, for we came into close association with the people of the Cedarberg too. On the Wednesday, after spending a morning roaming round the farm, we set out with Andries in his new Dodge truck to visit the neighbouring farms. It was a gay ride, sitting on top of the huge sacks of wool and we enjoyed the journey over the hills to Matjiesrivier and down the valley to Vogelfontein where the old road to Ceres comes. We put down a number of oranges there and we sat in the shade of the trees with the farm people, and admired the huge red rock krantzes nearby. ... [A few days later] news of his proposed trip [to Clanwilliam] went forth into the Cedarberg and as we progressed in the rain through the hills Andries' composite dairy cart and truck became filled with a heterogeneous collection of "aias," small boys, bottles of medicine, mud, mad mountaineers and genial old lasses who served out snuff. Now and again we would pile out and drink more coffee and meet more interesting Cedarberg people 84

At Krom Rivier they imagined they actually inhabited, albeit only for a short time, their pre-industrial rural idyll and 'wandered past the water-mill and bathed in the cool river as dawn broke . the farm school children recited to us and sang their new songs, and little white-haired Colonel O'Duffy, Andries' son, showed us where the tortoise lived, near the honeysuckle'.85

The Niewoudt's also inducted the Cape Town middle class into the region's Afrikaner history, exemplified in Anglo middle class accounts of the 1930s, the centenary decade of the 'Great Trek', by the 'the old Voortrekker's road'.86 These were not the nineteenth century Johnny-come-latelys feted by the Afrikaner nationalists, but, in Leipoldt's words, the 'eerste', 'egte' or 'ware voortrekkers' of the seventeenth century, 'wat in die stikdonker duisternis van algehele onwete gevaar het'.87 Their labours rendered 'elke morg hier ... historíese grond', declared Leipoldt, and 'In vergelyking met ons egte voortrekkers . is die later trekke van 'n honderd jaar gelede amper kinderspeletjies'.88 The notion of the early Dutch East India Company governors and officials as the true 'voortrekkers' and the Cedarberg as sacred ground was guaranteed to appeal to an Anglo urban middle class audience both innately hostile to a resurgent Afrikaner nationalism and firm adherents of the Rhodesian cult of Van Riebeeck.89

Cedarberg Anglo-Afrikaner's provision of local history to cater for the growing Anglo urban middle class interest in the area marked the beginning of the region's appropriation by the 'tourist movement' and the re-inscription of its past as artifactual heritage in place of conflictual history.90 It is also tempting to read Cedarberg native C. Louis Leipoldt's Valley trilogy, written in English the 1930s, but not published, as part of this process of rewriting the region as heritage specifically for the Anglo urban middle class tourist market, with its fictionalisation of the Cedarberg's settler history, evocation of a pre-South African War golden age of Afrikaner-English co-existence and denunciation of the National Party for unscrupulously exacerbating and exploiting post-war tensions between the two races for political gain.91 The trilogy is also not incidentally steeped in nostalgia for the pre-industrial Cape backveld. Thus Maria Vantloo, a central character in The Mask, the third novel in the trilogy set in the 1930s, equally appalled at the venal materialism of her husband and crude Afrikaner nationalism of her daughter

[T]hought of the old days, comparing and contrasting them with her own time. They seemed so far away that she had difficulty in persuading herself that her own intimate recollections of them were real and not imagined ... greed, passion and sordid materialism had displaced much of what she had herself been taught to value above price. She found herself unconsciously trying to find excuses for the present; for its feverish activity; its insistence on things that did not really matter; its negation of the things that counted so much in life.92

The incipient interwar creation of a 'homespun literature' for the Anglo tourist market was rendered stillborn by the Second World War and the subsequent death of Leipoldt and triumph of Afrikaner nationalism.

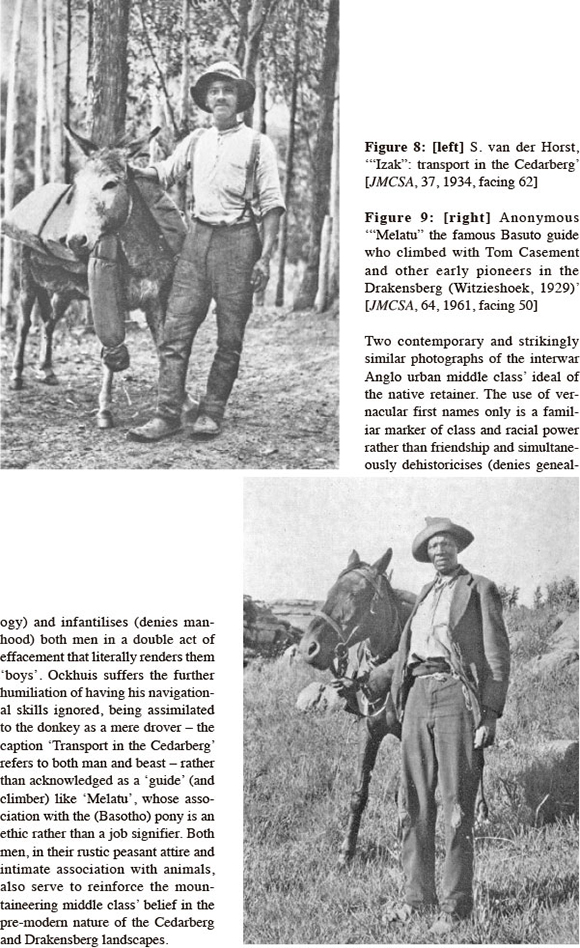

If Afrikaners were rehabilitated as civilised after 1918, the black population of the mountains was stripped of all agency and reduced to either deferential labour or heritage. The two could occasionally coincide in a double affirmation of the new national race order, such as that experienced by a party returning to 'the Bushman's "Klipgat" [cave] in Welbedacht Kloof to be greeted by our faithful porter Adam with "Wil Master koffie drink"'.93 'Boys and donkeys provided the '"swaardra"' hard labour of porterage which enabled middle class expeditions to maximise their climbing time in the Cedarberg and were a staple aside in the literature.94 While for the most part 'boys' were anonymous and interchangeable, a few attained the status of named faithful retainers and none more so than Izak/Isaak Ockhuis the only 'boy' whose named photograph ever appeared in the Annual.95

Doubly demeaned by being infantilised ('boy') and dehistoricised ('Izak' with no surname) Ockhuis, the descendant of an old mission station family, played his stock walk-on part of the trusty native retainer in the middle class drama of exploration with aplomb over several decades.96

The protracted dispossession of the Cedarberg's black inhabitants had, by the 1920s, converted the mountains into white public and private land, to which the native returned, if not as servile and deferential labour, then as the romanticised artefact and absence of heritage.97

'The camp we discovered consisted of a fine cave that had formerly been occupied by Bushmen, and on the walls were many of the typical paintings with which this interesting and unfortunately almost extinct race adorned their shelters. The decorations were in an excellent state of preservation, and, although the cave had apparently been used in more recent times by local coloured woodcutters, we congratulated ourselves on having come across a hitherto practically unknown haunt of the old occupiers of the country. The height at which the place is situated (just under 5,000 feet) suggests the theory that it was one of the last strongholds of the Bushmen when they were driven from t he lower levels by the inroads of the Hottentot races'.98

The 'Bushmen' presence was everywhere in the Cedarberg and although in this account their 'extinction' is attributed to the 'Hottentots', the Anglo urban middle class' increasing fraternisation with local Afrikaner gentry revealed other markers on the landscape of settler complicity in the Bushmen's demise.99 Thus a party walking from Kromrivier to Zanddrift in the mid-1930s with Andries Niewoudt as guide, after being shown several caves with Bushmen paintings, was unexpectedly initiated into another aspect of the local history inscribed on the landscape.

Continuing on our way towards Matjies River we reached the head of a well-defined ravine some two hundred yards long called "Moordhoek". The story goes that many years ago a shepherd was murdered here by three Bushmen. His master, an ancestor of Niewoudt's, came upon the Bushmen gorged on the meat of stolen sheep, and promptly shot them. The matter was amicably settled with the local Field Cornet on the grounds of self-defence.100

This was certainly not the only such example of settler violence against the indigenes revealed to the Anglo middle class on vacation in the Cedarberg. Leipoldt, for one, revelled in the savagery of the early Cedarberg 'voortrekkers' and interwar visitors to the Cedarberg would soon have been familiarised with the cruelties and crimes of 'Missies Ankus', Coenraad Fiet, Etienne Barbier and Antjie Somers.101

The translation of the violence of colonial land seizure and settlement into folklore for the urban bourgeois market required that it be given an appropriate moral coding for a class who worshipped the rule of law as a shibboleth. Hence the bushmen murdered by Niewoudt's ancestor were themselves thieves and murderers who got their just reward, albeit not through due process. What is unclear is who bore the burden of moral rationalisation, Niewoudt or his translators. The terse clipped account of the Moordhoek atrocity above suggests it was the latter. Another of Niewoudt's eager urban disciples, W.A. de Klerk, went to even more improbable lengths with the same or a similar event related to him by the magus, having the region's settlers menaced not by bushmen, but ''n klomp woeste seelui wat glo weens seerowery daarheen verban sou gewees het' in alliance with Coenraad Fiet.102The ur-Niewoudt retaliates with an 'antiseerowersoorlog', offering ''n uitgegroeide bees as belonging vir "'n paar ore"' and ending up with ''n heel halsnoer van ore'.103 When the oral tradition is so badly scrambled, even in a work of fiction, it is hard to escape the suspicion that the endemic 'unjust' violence of conquest was not being deliberately effaced from the record.104

For all its growing interest in cultural tourism, the interwar mountaineering middle class' primary interest in the Cedarberg remained its imagined romantic natural beauty exemplified by its mountain summits. The classic romantic vantage point of the summit prospect at sunset was the one, which in the Cedarberg was deemed most capable of yielding 'a scene almost supernatural in its perfection' and the prospect par excellence initially remained that from Tafelberg. 'Those who have stood where we stood need no reminder of the glories of the view; to those who have not stood no words can conjure up the scene' and pilgrims to its prospect 'feasted our eyes, and perchance our souls' in the classic romantic tradition.105 The eyes of beholders, however, had always to be 'torn away' to avoid the danger of being overtaken on the summit by the oncoming darkness.106

The Cedarberg summit prospect also enabled the mountaineers to locate themselves in the wider national space using the old imperial sight line of Table Mountain. Thus a 1922 summit party on Middelberg-North peak echoed Amphlett in reporting the view:

All of us have seen and raved over glorious summit prospects previously, but this one somehow, was different from all the others, and indescribably beautiful. The Atlantic Ocean, thirty miles away to the west, was a sea of molten gold, and the intervening hills and lowlands were shaded off into every conceivable shade of indigo purple and grey. Away to the North, from massive peaks in the foreground, stretched range upon range of mountains, their Western fronts aglow with crimsons and reds from the horizontal rays of the setting sun, and on the East heavily shadowed in purple. Even the black cliffs of Krakaduw Heights, a massive peak in the main range, radiated colour, and snow patches on the higher Sneeuwkop were tinted the most delicate rose. The deep valleys were filled with transparent shadow and the isolated Sneeuwberg, our antagonist of two days before, was a silhouette against the South-Western sky, black but edged with gold where the sun tipped the ridges. But despite the wondrous colouring and scenery of the nearer mountains, our gaze was riveted on a small break in the ranges to the South, a gap left seemingly for the purpose, where a dim grey outline, faintly set off by the more pinkish grey of the horizon, revealed itself as our Table Mountain, 120 miles away. This was the first sight of it we had had from the Cedar Mountains, and that the tantalising haze that was so prevalent on our earlier ascents should clear just sufficiently for us to obtain one glimpse, seemed a fitting finale to our climbing on the expedition'.107

That Table Mountain was a common sight from peaks in the surrounding folded was irrelevant, it was the Cedarberg-Table Mountain sight line that mattered.108

By the 1930s, however, the growing urban mountaineering traffic through Algeria, encouraged and guided by the 'pioneers' own fulsome accounts in the Annual, began to 'vulgarise' the Cedarberg and so diminish its attraction. Complained one pioneer in the mid-1930s, without a hint of irony, 'Scores of parties have visited the main central portions of the Cedarberg range and the peaks from Krakadouw to the Tafelberg have been almost "trampled flat" by climbers. The southern portions, right down to Elands Kloof, are rapidly succumbing to the same fate, judging by the number of people who go there these days'.109 The increasingly heavy traffic on 'the usual Cedarberg routine round to the Tafelberg and surrounding area' necessitated a continuous search for 'virgin fields' within the range to recapture the quintessential Cedarberg experience - 'Piled masses of rock, pretty, grass-covered flats, splendid peaks in every direction, all combined to create that feeling of utter well-being and contentment that comes to one only when the ensemble is composed of exactly the right ingredients and mixed in exactly the right proportions', only to be written up for the Annual and reproduce the original effect of despoliation within a season or two.110

With the opening up of new entry routes into the mountains, new areas, summits and sights (particularly Great Krakadow in the north and the Wolfberg Cracks and Arches in the south) slowly supplanted Tafelberg in the literature. Novelty rather than summit prospect were increasingly in vogue. The Wolfberg Arch was hailed as 'Truly a Hall of the Mountain King' that 'were it only in a finer setting ... would be one of the sights of South Africa', while Great Karakadow condensed all 'the Cedarbergen have to offer of strangeness and beauty' culminating in a summit of which it was claimed 'No demon in the world of mythology ever devised more involved and thwarting labyrinths than these'.111 By the late 1930s prospect and novelty were themselves increasingly eclipsed by a romantic mysticism as the area of ' terra incognita' shrank.112 Thus a writer on his fifth visit in 1936 confidently claimed, 'Such are the charms of the Cedarbergen . that even if every inch of its numerous summits had been covered the real devotee of the range, intoxicated with the incense-like scent of the Cedar-woods, would return again and again to its insistent appeal'.113

The religious overtones were intentional. Interwar neo-romanticism deemed mountains the abode of a pantheistic essence, dubbed the 'Spirit of the Mountains', whose most famous local evocation was by Smuts in his dedication of the Mountain Club war memorial at Maclear's Beacon on Table Mountain in February 1923.114 Following the final vulgarisation of Table Mountain in 1929 with the opening of a cableway, it was only natural that the 'Spirit of the Mountains', like its middle class devotees, should finally abandon the GOM for the unspoilt summits of the Boland. For the 'true mountaineer', rather than the '"two-or-three-beacon-a-day"' 'peak-bagger', the act of visiting the summit beacons was also one of religious devotion.115

A vivid memory is associated with three and a half hours spent on a high summit on a calm, silent, perfect day. The summit beacon is a special place with a special atmosphere, and to understand that atmosphere we must be still and take time to receive what the mountains have to give us. There, in a special way, our beings become saturated with what has so often been described as the Spirit of the Mountains, which is in reality the Spirit of their Creator.116

'But when once one has received the spirit of the mountains life takes on a fullness, a charm and a sweetness unknown before. This spirit comes gradually and fills one with an unspeakable joy, not only when among the mountains, but at all times'.117 For this reason too the 'beacon records' deposited by summit pilgrims were 'sacred and should be handled with the utmost care' and the national trig survey's replacement of the original 'picturesque, symmetrical and weatherworn cairns' with the 'ugly, white-washed, concrete, cylindrical beacon with its superimposed black iron wings' was an act of desecration in which 'valuable and interesting records have disappeared'.118

Such mysticism reached its interwar apogee in W.A. (Bill) de Klerk's short story, Die Kruis van die Seders, the first Afrikaans prose to be carried by the Annual in a half century of publication, which transposed Smut's 'spirit of the mountain' from the old Table Mountain to the new. The story opens with de Klerk and two companions on the final day of a week long expedition in the Cedarberg discovering a small farm somewhere west of Algeria.

Die voetpaadjie het meteens verby 'n klein sederplantasie gevoer. Nog 'n paar hondered tree verderaan het ons afgekom op 'n hartbeeshuisie, met geil tabaklande daarom, 'n paar majesteuse eikebome, en 'n ouderwetse watermeul waaroor 'n bergstroom ruisend getuimel het'.119

This pre-industrial rural idyll is presided over by the patriach Van Jaarsveld, ''n bejaarde man met spierwit baard and staalgrys oe', who over 'koffee ... [en] egte boerebeskuit', relates to the party the morality tale of 'Helgard die Noordman' and the truth about the Maltese Cross.120

Helgard, an Aryan nobleman from 'een van die Noordelande', forswears 'die sataniese lus on meester te word van die blink, geel metal', gives his wealth away to the poor and goes on a quest to find

''n plek waar daar rus an orde was, 'n plek, eg en ongekunsteld, waar die ware en enige geluk in die scone en majesteuse eenvoud om hom gevind kom word . Hy wou 'n plek vind waar die mense nog arm aan goud was, en arm aan gees. Want daar alleen het hy geweet sou hy die rykdom van hart aantref wat die enige bron van ware geluk kon wees'.121

His search ends in the Cedarberg on the slopes of the Sneeuberg when 'hy 'n stem, soos die stem van die Groot Gees van die Berge, in sy hart hoor roep ... [en] hom vertel dat sy reis op 'n end was'.122 For five years he lives in the Cedarberg at peace, but then one morning, while searching for wild honey, he discovers a deep, dark cave under the earth full of gold. Fleeing the cave into a wild storm above he trades his life to 'die Groot Gees van die Berge' in return for keeping the existence of the gold secret and thus the Cedarberg safe from despoilation. A lightning bolt instantly seals the cave and slays Helgard, but the Great Spirit of the Mountains, moved by his selfless sacrifice, lays his body gently out on a plain where 'die sederreuse ewig waghou' and builds the Maltese Cross as his gravestone.123

De Klerk's Afrikaans evocation of a Smutsian mountain mysticism in the pages of the Mountain Club Annual was the highwater mark of the brand of inclusive white imperial nationalism espoused by the General and enthusiastically subscribed to by Cape Town's interwar Anglo urban middle class. It could not survive the twin reversals of his 1948 election defeat and own death two years later. By then too De Klerk and urban Afrikaner intellectuals like him had moved far beyond sentimental nostalgia for a pre-capitalist world guarded by the Spirit of the Mountains and inhabited by paternalistic patriarchs like the fictional van Jaarsveld or the real life Niewoudt, to embrace modernity as vital to Afrikaner ethnic survival in an industrialising market economy dominated by Anglo capital.124

Afrikaner Alpinism

Following Leipoldt's death in 1947, a younger generation of Anglo Afrikaners, in particular de Klerk and his friend Marthinus (Martin) Versveld, were free to re-imagine the Cedarberg in the idiom of volkskapitalisme. They rejected the pre-war Cedarberg pastoral of both the Anglo urban middle class and older generation of Afrikaner intellectuals such as Leipoldt and I.W. van der Merwe (Boerneef) and conjured a place where custom and modernity had hybridised to produce an oxymoron - a progressive traditional society - in which the paternalism of the state had supplanted that of the Groot Gees van die Berge and the patriarchs.125 Thus Versveld, while evoking an 'outydse boerelewe onder die berge' peopled by 'die sout van die aarde', claimed that it was best apprehended as a second class passenger on the railway bus service. 126

Want die bus is 'n instelling, die redding van die sosiale lewe van die Clanwilliamwyk. Op die bus vind jy 'n deursneebeeld van die distrik ... die onderwyser, steunpilaar van die gemenskap; . kinders wat skool-toe gaan met velskoene en breerand hoede; ... 'n waardige tannie wat gaan kuier met 'n bliktrommel en 'n sak patats;

... 'n rou meisie wat agter die berge wil uit om verpleegster to word; ... volkies wat 'n ander distrik werk wil gaan soek.127

Versveld's cast, in addition to being stock pre-modern stereotypes, are all, beneath their customary costumes, dependents of the modern state; as commuters on its parastatal bus service; employee and charges of its education system and would-be employee of its health department. If Versveld was limited by the factual convention of the mountain diary format, his friend De Klerk's turn to fiction allowed for a much fuller exploration of the dilemma of development for ethnic nationalists.

De Klerk's 1953 novel, Die Uur van Verlange, set in a barely fictionalised Cedarberg/Agterberg, posed the question of development in the stock conventions of the period 'plaasroman', but with an unconventional anti-pastoral solution which rejected a return to the land and advocated instead the embrace of modernity.128 As well as his own experience, De Klerk drew liberally on Niewoudt's oral history of his family and the region. 'Ek het baie dae, baie nagte na hom sit en luister. Dit het oor jare gegaan. Met sy verlof het ek aantekeninge gemaak van sy vertellings. Kon ek dit probeer weergee - op my eier manier? Hy was eers huiwerig. Op 'n dag het hy egter toegestem. Ek het my beste gedoen en dit is my hoop dat wat hier volg die leser sal boei soos ek eerste geboei is'.129 That the unanamed source is Niewoudt, was made clear in a dedication that appeared in later editions and also by De Klerk in his 1986 obituary for Niewoudt in the Annual.130 What Niewoudt thought of his translation into fiction by de Klerk is unknown.

The novel is narrated by Conraad Beyers, the university educated son of Cedarberg patriarch Zirk Beyers (Niewoudt) and spans the years of Afrikaner nationalism's rise to power told in four acts. The first is set in 1928 when 'Con' graduates from Stellenbosch and leaves for postgraduate study in the United States, the second in the final third of the 1930s when Con returns from eight years in America and the last two in the late 1940s when he is working as an industrial engineer in the Cedarberg in the service of volkskapitalisme.

In the first act De Klerk conjures the Agterberg as a 'afgeslote wereldtjie' peopled by a stereotypical cast of benign Afrikaner 'base' and loyal Coloured 'volkies' knitted together by the all-encompassing paternalism of the older generation of Boer patriarchs and marinated in a rich folklore of 'weerstene', 'waterbase', 'sieners', 'gifmuste', 'waternooiens' and 'spoke'.131 The isolation that preserves this 'little world', however, is already everywhere breaking down, not least in the minds of the younger generation of 'base', whose education has opened their eyes to its backwardness and hardened their hearts against nostalgia. As their self-appointed leader, Herman Brink, declares, 'Selfs die Agterberg sal nie vir altyd die Agterberg bly nie! ... in hierdie tyd waarin ons leef is daar maar weining plek vir sentiment'.132

Een ding is seker en dit is dat die ou manier van te werk gaan nie meer gaan deug nie. Klein plasies met lappies grond hier en daar -en 'n mark wat moeilik is on te bereik ... ons [sal] in die algemeen meer doeltreffend moet wees - in ons eie belang.133

The depression serves as the dues ex machina that finally breaks the back of the Agterberg's dilapidated and declining pre-modern agrarian economy, forcing the older generation off the land and allowing the young Turks to consolidate landholdings and modernise production, as narrated in the novel's second act. Brink's farm, 'Verland', epitomises the new 'kapitalistiese omvorming van die land'.134

Op agtien myl van die dorp het ons weggeswaai van die groot pad en op tussen Verland se pragtige uitgestrekte boorde. Die lemoen bome, wat nog hier en daar 'n gloeiende vrug getoon het, was wit in die blom. Die hele lugruim was heerlik bewierook. Op die land was trekkers. Tussen die bome het volk met meganiese pompe gespuit. 'n Groot reservoir was in aanbou ... Alles is wonderlik agtermekaar. Die hele aanleg - so groot soos hy is - is fyn versorg. Nerens is daar enige teken van rofbou of verwaarlosing of onwetenskaplikheid nie. So iets het ek laas in Amerika gesien.135

The generalisation of Verland's citrus revolution to the Agterberg follows in acts three and four, enabled by the state's damming of the Tra-Tra River for irrigation purposes on the eve of the Second World War. This touches off a postwar boom of 'gedronge, koorsagtige groei' in which a co-operative, canning factory, mine and national road come in quick succession to the Agterberg.136

Conraad Beyers, having played a key role in the crash modernisation of the Agterberg, in his capacity as an American trained industrial engineer, suffers a crisis of faith in the progress he has helped author and an 'uur van verlange' for the lost feudal world of the pre-modern Agterberg.137 Con's dark night of the soul is triggered by his reading of a thinly disguised Leipoldt in which 'Verlange skryn op elke bladsy - die verlange na 'n wereld en 'n tyd wat lank reeds verby is'.138 Leipoldt determines him; 'Ek sal gaan! Ek sal doen wat hy gese het. Ek sal gaan rus soek, genesing op die ou grond waar ek gebore en getoe is'.139 His personal crisis he believes is symptomatic of a general malaise afflicting the volk, for whom the same remedy of a return to the past and the land is indicated.

Ons mense is uitgeruk uit hul ou en hegte gemeenskap. En ek het dit help doen. Wat is hulle nou? Los atoompies wat met 'n vol buik en 'n lee siel rondloop. En elkeen is eensaam, verlore - sonder verband meer. Wie het reg op herberg? Wie waak by siektes? Wie is een met jou by geboorte en huiwelik en dood? ... Ek se jou ons moet terug ... ons moet terug na die grond!140

Con's romantic, anti-modernism, parodying that of the interwar Anglo urban middle class and its Afrikaner fellow travellers like Leipoldt, is summarily rejected by his new love, Fransie, herself a daughter of the Agterberg-cum-university educated industrial psychologist.

Ons kan nie terug nie Con . Ons moet voortgaan . Ons moet bewaar wat ons bereik het maar ook bou , opnuut bou aan dit wat ons verwaarloos het. Ons moet nuwe vorme vind, 'n nuwe adel.141

The urban Afrikaner intellectuals' post-Second World War rejection and revision of interwar Anglo alpinism more closely approximated the earlier colonial variant in its cataloguing and critique of the conservatism and inefficiencies of the pre-modern Afrikaner rural economy, but with a softer empathic edge of insiders.

The Cedarberg pilgrimage thus took on a fundamentally different meaning for urban Afrikaners like Versveld and de Klerk after 1945 for whom it had always been an escape from modernity to more intimate and immediate (though no less 'imaginary' in Anderson's sense) pre-modern roots than their urban Anglo fellow travellers.142 While the latter played at being Afrikaners on their Cedarberg holidays, urban Afrikaners were Afrikaners and regular (re)immersion into rural Afrikaner society in the Cedarberg during the decades of heightened nationalist mobilisation and triumph threw the tension between tradition and modernity into stark relief. The younger generation of urban Afrikaner professionals' deference to the customary wisdom of the feudal patriarchs on these excursions was increasingly tempered by the realisation of the practical obsolescence of both for the pressing task of ethnic economic salvation. Afrikaner national alpinism in its mid-twentieth century form thus attempted the delicate oedipal balancing act of respecting the elders while at the same time ushering them politely, but firmly from the stage of history into the museum of heritage.

The Enduring Frame

Colonial alpinism, as Herman Wittenberg has argued, has had a long (and usually unrecognised or unacknowledged) reach down the twentieth century in South Africa.143 The same is true of the indigenous settler variant of the discourse that clustered around the Cedarberg. Interwar Anglo national alpinism finds its modern echo in both the journeymen writers of the 'homespun literature' tradition and the more illustrious work of Stephen Watson, while the Afrikaner nationalist variant has become bifurcated.144 The old Boland intellectual tradition of Versveld and de Klerk found exponents like M.I. Murray as late as the 1970s, while a new radical strain closer to Anglo alpinism in its universalising anti-modern romanticism won more celebrated converts in Breyten Breytenbach and Jan Rabie.145

The recycling of Cedarberg alpinism over the course of the long twentieth century points not only to the enduring ego, narcissism and alienation of successive generations of urban bourgeois intellectuals, but also to the continued centrality of key symbolic landscapes to the fashioning of settler imagined communities in southern Africa.146 The identification and evocation of such landscapes in both the national present and past continues to rely, as Wittenberg has argued, more or less (though usually less) self-consciously on the original colonial romantic trope in which they were first cast.

1 See for example P. Harries, 'Under alpine eyes: constructing landscape and society in late pre-colonial south-east Africa', Paideuma, vol. 43, 1997, 171-91; H. Wittenberg 'Ruwenzori: imperialism and desire in African alpinism' in Wilson, R. and C. von Maltzan (eds) Spaces and Crossings: Essays on Literature and Culture in Africa and Beyond (Peter Lang, Frankfurt a. M. 2001), 235-58 and H. Wittenberg, 'The sublime, imperialism and African landscape' (Ph.D thesis, University of the Western Cape, 2004)

2 See P. Merrington 'Heritage, letters and public history: Dorothea Fairbridge and Loyal Unionist cultural initiatives in South Africa, c.1890-1930' (Ph.D thesis, University of Cape Town, 2002) for a notable exception.

3 See M.H. Nicolson, Mountain Gloom and Mountain Glory: The Development of the Aesthetics of the Infinite (Cornell: Cornell University Press, 1959); D.D. Zink, 'The beauty of the Alps: a study of the Victorian mountain aesthetic', (Ph.D thesis, University of Colorado, 1962) and S. Schama, Landscape and Memory (London: Harper Collins, 1995).

4 See P.H. Hansen, 'British mountaineering, 1850-1914' (Ph.D thesis, Harvard University, 1991); 'Albert Smith, the Alpine Club and the invention of mountaineering in mid-Victorian Britain', Journal of British Studies, vol. 34, 1995, 300-24 and 'Vertical boundaries, national identities: British mountaineering on the frontiers of Europe and the empire, 1868-1914', Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History, vol. 24, 1996, 48-71.

5 See for example F.E., 'A scramble in the Uitenhage Alps', Cape Monthly Magazine, vol.36 (61), June 1873, 339-44 and A Cape Climber, 'From Table Mountain to the Alps', Cape Illustrated Magazine, vol. 9, no. 2, October 1898, 58-72 for contemporaiy Cape manifestations of alpinism and L. van Sittert, 'The bourgeois eye aloft: Table Mountain in the Anglo urban middle class imagination, c.1891-1952', Kronos, vol. 29, 2003, 161-90 for the Mountain Club.

6 See G.T. Amphlett, 'A trip to the Cedarberg', Cape Illustrated Magazine, vol. 7, no. 3, November 1896, 65 for the quote; L. van Sittert, 'Holding the line: the rural enclosure movement in the Cape Colony, c.1865-1910', Journal of African History, vol.43, 2002, 95-118 for enclosure in general and Van Sittert, 'Bourgeois eye' for the enclosure of Table Mountain.

7 See 'Annual dinner', Journal of the Mountain Club of South Africa [hereafter JMCSA], vol.5, 1899, 13.

8 Amphlett, 'Trip', 66.

9 See W.H. Wills and R.J. Barrett, The Anglo-African Who's Who and Biographical Sketchbook (London, 1905), 2-3 and G.T. Amphlett, History of the Standard Bank of South Africa Ltd. 1862-1913 (Glasgow, 1914), v-vii for Amphlett's personal and professional biography.

10 See for example D. Haarhof, The Wild South West: Frontier Myths and Metaphors in Literature set in Namibia 1760-1988 (Johannesburg: Witwatersrand University Press, 1991) and I. Hofmeyr 'Turning region into narrative: English storytelling in the Waterberg', in P. Bonner et al (eds.), Holding Their Ground: Class, Locality and Culture in Nineteenth and Twetieth Century South Africa (Johannesburg, Witwatersrand University Press and Ravan, 1989), 259-84 for writing regions in southern Africa.

11 See Hansen, 'British mountaineering' and 'Albert Smith' for the European tradition and Wittenberg, 'Sublime' for its African translation.

12 See for example M-L. Pratt, Imperial Eyes: Travel Writing and Transculturation (London: Routledge, 1992); N. Penn, 'Mapping the Cape: John Barrow and the first British occupation of the Colony, 1795-1803', Pretexts, vol. 4, 1993, 20-43; K. Parker, 'Fertile land, romantic spaces, uncivilized peoples: English travel writing about the Cape of Good Hope, 1800-1850', in B. Schwarz (ed.), The Expansion of England: Race, Ethnicity and Cultural History (London: Routledge, 1996), 198-231; W. Beinart, 'Men, science, travel and nature in the eighteenth and nineteenth-century Cape', Journal of Southern African Studies, vol. 24, 1998, 775-799 and L. Guelke, and J.K. Guelke, 'Imperial eyes on South Africa: reassessing travel narratives', Journal of Historical Geography, vol. 30, 2004, 11-31.

13 See A. Mabin and B. Conradie, The Confidence of the Whole Country: Standard Bank Reports on Economic Conditions in Southern Africa,1865-1902 (Johannesburg: Standard Bank, 1987) for a sampling.

14 Amphlett, 'Trip', 77.

15 M.C. Bilbe, 'A social history of the Wupperthal mission in South Africa, 1830 to 1965', (Ph.D thesis, University of Cambridge, 2003), for the Villoen clan's origins and status in the Cedarberg.

16 See M. Anderson, 'Elandskloof: land, labour and Dutch Reformed mission activity in the southern Cedarberg' (Honours dissertation, University of Cape Town, 1993); D. Nel, 'Land ownership and land occupancy in the Cape Colony during the nineteenth century with specific reference to the Clanwilliam district', (Honours dissertation, University of Cape Town, 1997); M.C. Bilbe, 'Wupperthal: listening to the past', (Honours/Masters thesis, University of Cape Town, 1999) and Bilbe, 'Social history' for nineteenth century black land ownership in the Cedarberg.

17 Amphlett, 'Trip', 72.

18 Amphlett, 'Trip', 72.

19 Amphlett, 'Trip', 73.

20 Amphlett, 'Trip', 71 and 65.

21 Amphlett, 'Trip', 75. See also Anonymous, 'The Clanwilliam cedar Part 1', Cape Illustrated Magazine, vol. 9, no. 7, March 1899, 243-51 and Anonymous, 'The Clanwilliam cedar Part 2', , Cape Illustrated Magazine, vol. 9, no. 8, April 1899, 318-27 for the cedar tree and L. van Sittert, 'From mere weeds and bosjes to a Cape floral kingdom: the re-imagining of indigenous flora at the Cape c.1890-1939', Kronos, vol. 28, 2002, 102-26 and Van Sittert, 'Bourgeois eye', for the silver tree.

22 Amphlett, 'Trip', 65.

23 Amphlett, 'Trip', 75.

24 See B. Nasson, Abraham Esau's War: A Black South African's War in the Cape, 1899-1902 (Cape Town and Cambridge: David Philip and Cambridge University Press, 1991); R.J. Constantine, 'The guerrilla war in the Cape Colony during the South African War of 1899-1902: a case study of the republican and rebel commando movement', (MA thesis, University of Cape Town, 1996) and M. North, 'Clanwilliam during the 1899-1902 South African War: considerations of social conditions and context as determinants of local loyalties (Department of Historical Studies Third Year project, University of Cape Town, 1997).

25 Union of South Africa, Report of the General Manager for Railways and Harbours, 1938-39 [UG45-39], Statement No. 17, 194-200.

26 See M. Voss, 'Woodcutters, farmers and forestry officials: rethinking conservation in the Cedarberg, 1870-1930' (Honours dissertation, University of Cape Town, 2004).

27 See for example, K. Cameron, 'The Cedar Mountains of Clanwilliam', JMCSA, 25, 1922, 85-86 and 89.

28 See Van Sittert, 'Bourgeois eye', 169-75 for forest department road construction and middle class recreation on Table Mountain.

29 Cameron 'Cedar Mountains', 89.

30 S. Biesheuvel, 'Great Karakadouw: monarch of the northern Cedarbergen', JMCSA, vol. 38, 1935, 47 and D. Gordon Mills, 'New ground near Clanwilliam: Tierhoekberg and Lambertshoekberg', JMCSA, vol. 41, 1938, 61 for the quotes.

31 Union of South Africa, Department of Census and Statistics, Special Report Series, No.42, Motor Vehicle Statistics for the year 1926, Table 5, 5 and No. 142 Motor Vehicle Statistics for the year 1939, Table 4, 4.

32 See for example F. Berrisford, 'The Cold Bokkeveld: Oliphants River Dome and Elands Kloof', JMCSA, vol. 35, 1932, 54-55; S. le Roux, 'New routes on Apollo', JMCSA, vol. vol. 40, 1937, 47-49; R. Anson Cook, 'Men, women and events', JMCSA, vol. 69, 1966, 18-19 and S. Biesheuvel, 'A mountaineer's paradise revisited', JMCSA, vol. 93, 1990, 21.

33 D. Gordon Mills, 'The Cold Bokkeveld', JMCSA, vol. 29, 1926, 50 for the 'country trip'.

34 R. Hallack, 'A trip to the Cedarberg Mountains', JMCSA, vol. 31, 1928, 98.

35. K. Cameron, 'Pakhuis peaks: northern Cedar Mountains', JMCSA, vol. 39, 1936, 26. See also A.B. Berrisford, 'Elands Kloof: Middelberg Ridge', JMCSA, vol. 40, 1937, 50.

36 See R. Anson Cook, 'Early motorneering: an extract from a mountaineer's diary', JMCSA, vol. 67, 1964, 30-32; Anson Cook, 'Men', 18-19; S.H.H., 'A mountain and a motor car', JMCSA, vol. 30, 1927, 91 and 93 and E.S. Field, 'A week-end in the Cedarbergen: the Krakadouw Peaks from Bosch Kloof', JMCSA, vol. 37, 1934, 62.

37 See J. Forster, 'Capturing and losing the lie of the land: railway photography and colonial nationalism in early twentieth century South Africa', in J. Ryan and D. Schwartz (eds.), Picturing Place: Photographs in the Construction of Imaginative Geographies (London: Tauris, 2002), 141-61; 'Land of contrasts or home we have always known?: the SAR&H and the imaginary geography of white South African nationhood, 1910-1930', Journal of Southern African Studies, vol. 29, 2003, 657-80 and 'Northward, upward: stories of train travel, and the journey towards white South African nationhood, 1895-1950', Journal of Historical Geography, vol. 31, 2005, 296-315 on interwar train travel and the formation of a white national consciousness.

38 K. Cameron, 'The Cedar Mountains of Clanwilliam: a second visit', JMCSA, vol. 27, 1924, 20.

39 Cameron, 'Cedar Mountains', 84.

40 See Amphlett, History, v-vii and J. Berman, A Peak to Climb: The Story of South African Mountaineering (Cape Town: Struik, 1966), for the death and disabling of the three original Cedarberg pioneers.

41 See 'Up the Tafelberg with handkerchief and bootlace: the first ascent of the Cedarberg Tafelberg', JMCSA, vol. 63, 1960 for a reprint of Amphlett's original account which excised all but the climbing..

42 See Anson Cook, 'Motorneering', 30-32 and S.A. Craven, 'The Cedarberg in August-September 1930', JMCSA, vol. 101, 1998, 53-57 for examples of this genre.

43 See K. Cameron, 'Cedar Mountains: a second visit', 24-25 and 29 and F. Berrisford, 'Two new climbs in the Cedarbergen', JMCSA, vol. 27, 1924, 37 for the quotes and E.S Field and E.G. Pells, A Mountaineer's Paradise (Worcester: Mountain Club of South Africa, 1925) for the similar aim 'to popularise country peaking with its many joys' in the mountains of the Worcester division.

44 See Van Sittert, 'Bourgeois eye', 179-89

45 'Roll of honour', JMCSA, vol.26, 1923, frontispiece.

46 See Van Sittert, 'Bourgeois eye', 179-89. Also F. Trentmann, 'Civilisation and its discontents: English neo-romanticism and the transformation of anti-modernism in twentieth century western culture', Journal of Contemporary History, vol. 29, 1994, 583-625 and S. Moranda 'Maps, markers and bodies: hikers constructing the nation in German forests', www.nationalismproject.org/articles/Moranda/moranda.html for other interwar examples of the identification of the nation with the countryside.

47 See K. Angier, 'Patterns of protection: women industrial workers in Cape Town, 1918-1939' (Ph.D thesis, London University, 1998), 37-106.

48 See D. Bunn, D., 'Relocations: landscape theory, South African landscape practice, and the transmission of political value', Pretexts, vol. 3, 1992, 44-67 and D. Bunn, 'Comparative barbarism: game reserves, sugar plantations and the modernisation of South African landscape', in K. Darian-Smith et al (eds.), Text, Theory and Space: Land, Literature and History in South Africa and Australia (London: Routledge, 1996), 37-52.

49 See J. Carruthers, The creation of a national park, 1910 to 1926', Journal of Southern African Studies, vol. 15, 1989, 188-216 for the Kruger National Park.

50 See J.M. MacKenzie, "Chivalry, social Darwinism and ritualised killing: the hunting ethos in central Africa up to 1914', in D. Anderson and R. Grove (eds.), Conservation in Africa: People, Politics and Practice (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987), 41-61 and J.M. MacKenzie, The Empire of Nature: Hunting, Conservation and British Imperialism (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1988) for a similar slippage in the case of hunting.

51 See for example K. Cameron, 'Cedar Mountains: a second visit', 30-32 and S.T. van der Horst 'New work in the Cedarbergen: a through-trek and some new Krakadouw peaks', JMCSA, vol. 33, 1930, 58-59.

52 See R.J. Johnston, 'Some Cedarberg "peak-bagging"', JMCSA, vol. 33, 1930, 66 for ownership F. Berrisford, 'New climbs', 36-37 for beaconing.

53 A.B. Berrisford, 'New work in the Cedarbergen: north of Middelburg North', JMCSA, 33, vol. 1930, 64.

54 A.B. Berrisford, 'A new Cedarberg area: the Sandfontein district', JMCSA, vol. 38, 1935, 50.

55 F. Berrisford, 'The Upper Oliphants River: an exploration of its headwaters', JMCSA, vol. 40, 1937, 32 and D. Gordon Mills, 'The Cold Bokkeveld', JMCSA, vol. 29, 1926, 52 for quotes.

56 See JMCSA, vol. 27, 1924, facing 33; JMCSA, vol. 29, 1926, facing 52; JMCSA, vol. 31, 1928, facing 106; JMCSA, vol. 36, 1933, facing ?; JMCSA, vol. 37, 1934 facing 66; JMCSA, vol. 38, 1935, facing 56; JMCSA, vol. 39, 1936, facing 30; JMCSA, vol. 40, 1937, facing 40; JMCSA, vol.41, 1938, facing 60 for interwar Cedarberg maps in the interwar Annual.

57 See R. Taylor, 'A map of the Cedarberg', JMCSA, vo.55, 1952, 55 for the turning point.

58 See T.J. Bassett and P.W. Porter, 'From the best authorities: the Mountains of Kong in the cartography of West Africa', Journal of African History, vol. 32, 1991, 367-413 for 'decorative' and 'scientific'.

59 See Berrisford, 'Upper Oliphants', 31; Berrisford, 'New Cedarbergen area', 52 for the quotes.

60 F. Berrisford, 'North of Sandfontein: in the southern Cedarbergen', JMCSA, vol. 38, 1935, 65

61 Gordon Mills, 'New ground', 61 for the quote and Van Sittert, 'Bourgeois eye' 169-70 and 184 for the astronomers and mountaineering.

62 J.C. Kannemeyer (ed.), So Blomtuin-vol van Kleure: Leipoldt oor Clanwilliam (Cape Town: Tafelberg, 1999), 42.

63 See for example Cameron, 'Cedar Mountains', 88, 94, 96, 97, 100 and 103; Cameron, 'Cedar Mountains: a second visit', 22, 23 and 25; Gordon Mills, 'Cold Bokkeveld', 52-53; Hallack, 'Trip', 103; M.H. Hallack, 'The Cold Bokkeveld mountains', JMCSA, vol. 32, 1929, 14 and 15 and Berrisford, 'Cold Bokkeveld', 52.

64 Berrisford, 'Upper Oliphants', 35-36.

65 K.H. Barnard, 'Citrusdal to the Krom River cave', JMCSA, vol. 31, 1928, 105.

66 Gordon Mills, 'Cold Bokkeveld', 51.

67 See Van Sittert, 'Bourgeois eye', 181 for the symbolic importance of agrarian ruins on Table Mountain.

68 S.H.H., 'Mountain', 92.

69 Gordon Mills, 'Cold Bokkeveld', 51-52.

70 Berrisford, 'Upper Oliphants', 32 and Gordon Mills, 'New ground', 59.

71 H.M. Trainor, The southern Cedarbergen: donkey transport from Citrusdal', JMCSA, vol. 40, 1937, 44.

72 See S.H.H., 'Mountain', 94 and Berrisford, 'Cold Bokkeveld', 51 for examples of bilingualism so rare as to warrant comment.

73 Cameron 'Cedar Mountains', 85.