Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Kronos

versión On-line ISSN 2309-9585

versión impresa ISSN 0259-0190

Kronos vol.31 no.1 Cape Town 2005

ARTICLES

The Private Performance of Events: Colonial Period Rock Art from the Swartruggens*

Simon HallI; Aron MazelII

IDepartment of Archaeology, University of Cape Town

IIInternational Centre for Cultural and Heritage Studies, University of Newcastle upon Tyne

Of the herdsmen, however, I remember nothing... I only know that they were always around somewhere...so that one accepted their constant presence without taking any further notice of them.

Karel Schoeman, This Life

Introduction

In the Western Cape there is a distinctive set of rock art imagery that is explicitly colonial in content. In general, this is the work of the descendents of Khoe pastoralists and San hunter-gatherers who, as the colonial frontier closed around them, lost their economic independence and ideological identities, merged and became fully subordinated within the labour needs of the rural farm economy. Compared to the many rock shelters occupied by the San and which preserve thousands of their precolonial fine line paintings, the colonial rock art legacy is small.1 Most rock art research has, consequently, focused on the San fine line images.

There have, however, been some important preliminary enquiries into the colonial period rock art.2 Two key questions have been asked, the first being the all-important issue of age which is no less important for this colonial period art. As with all rock art, the painting of each panel was a specific event that was tied to its own ritual context, purpose, needs and motivations. Most archaeological interpretation can never recover the singularity of this historic scale and the event remains anonymous. Most interpretations focus on the scale of normative cultural practice and changes to these over time and space which are historical only at the most general scale. The promise of colonial period rock art, however, is that specific content, forms and depicted artefacts can perhaps be tied more securely to events, given the contextual control and informing resonance provided by written and oral evidence. Rock art panels in the Western Cape with motifs that are explicitly colonial obviously date between the second half of the seventeenth century and the nineteenth century. Such a broad time span is, however, unsatisfactory because we presume that there is a sequence of rock art dating to the colonial period and if it is to make any contribution to understanding the progressive subordination of rural people, then, just as is the case for pre-colonial periods, chronological resolution for the art is critical and has to be as finely tuned as the sources allow. The first part of this paper, consequently, seeks to refine the chronology for some of the colonial art. This is done by identifying a sufficient number of attributes in the artefacts painted that suggests to us particular types, and these types are then linked to dates of manufacture and use. In the process of refining chronology in this way, the historic scale changes from a general process to a more specific event, and this in turn, provides some context to think about meaning and motivation in this art.

What the art might mean is the second question that has been asked by earlier researchers and we also pursue this question in the second part of this paper. While our chronological discussion is aimed at a quite specific set of images, the meaning question ranges more widely and loosely over different images and sites. The question as to what motivated people to depict elements of their colonial world and what meanings they sought to impart may be approached from two directions that are not mutually exclusive. The first asks how much cultural continuity is there between the precolonial painting traditions and the colonial tradition? Does cultural practice in the past help understand meaning and motivation in the colonial context? This approach is basically comparative and looks 'back' at precolonial paintings in order to search for continuity in features into the historic period, and by extension, continuity in cultural themes as well.3 The conclusion from such comparisons, however, is that there is little if any formal continuity in motifs between the fine line San tradition and the colonial art. On the current understanding of the chronology of the fine line tradition this is not surprising because it is suggested that the fine line tradition waned towards the end of the first millennium AD.4 If this chronology is correct there is a significant temporal and cultural disjuncture between past and 'present', and any symbolic touchstones from precolonial painting traditions must be sought elsewhere.

More positive is the potential continuity between a second painted tradition in the Western Cape in which handprints and finger dots are the dominant motifs.5 These seem to date predominantly from the second millennium AD. Some argue that these were done by Khoe pastoralists, while others are more cautious, and suggest only an association between these motifs and the chronological period that saw the Western Cape landscape increasingly dominated by people who were ideologically committed to pastoralism.6 The current evidence indicates that there is certainly a better case for seeing some continuity of handprints and finger dots into the colonial art and this is also discussed in the second section of this paper.7

The colonial paintings of the Western Cape do not, however, appear to be a contextual re-casting of indigenous values that 'worked' to anchor and assimilate change within a familiar set of cultural touchstones, as in the examples of San and farmer art noted above. In those cases indigenous ideologies provided a substrate to mediate, absorb, challenge and strategically manoeuvre around the demands and opportunities offered by colonial encroachment. Consequently, we emphasise a second approach to understanding meaning and motivation which is to appeal less to the traditions of the past and more to the immediate historic context and the day-to-day circumstances of the artists as marginalised and subordinated rural labourers. Within this condition, we seek to emphasise the political action, in the broadest sense, that potentially resided in the production and consumption of these images. In this regard we touch lightly upon the work of James Scott to provide one framework that may capture the rationale, or at least some of the motivation for painting.8 Central is the multiplicity of ways in which subordinates seek to undermine and subvert those that dominate them in the daily demands upon their labour. One way to view colonial period paintings, therefore, is that they form part of what Scott calls a 'hidden transcript', that comprises 'those offstage speeches, gestures, and practices that confirm, contradict, or inflect what appears in the public transcript', which is defined as a 'subordinate discourse in the presence of the dominant'.9 It seems that such a framework is entirely congruent with the promise of an archaeology practised within the material remains of the recent past. This seeks to dig within and below conventional historical horizons to expose the lives of people, such as the invisible herdsmen of Schoeman's text, whose lives in their mundane daily grind, were not necessarily privileged by written evidence.

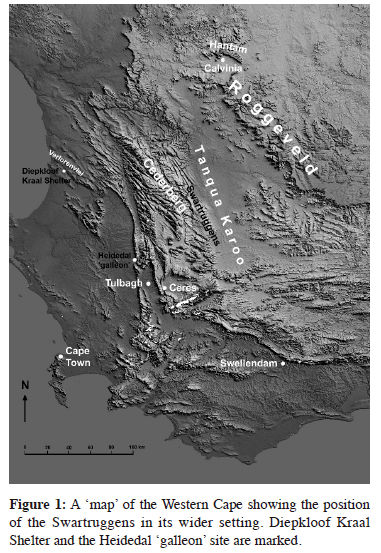

Public events

One approach to dating rock art sites within the colonial period has been to focus on their distribution on the landscape. As mentioned, rock art sites with colonial period images are relatively few in number in the Western Cape, but there are, nevertheless, sufficient sites to indicate that they are more frequently encountered in certain areas than in others. One such area is the Swartruggens and parts of the Koue Bokkeveld that lie on the eastern margins of the Cape Fold Belt (Fig. 1). The Skurwerberge range of the Cederberg lies immediately to the west of the Swartruggens and the Tanqua or Ceres Karoo to the east. It is in the Swartruggens that the main concentration of colonial period rock art sites has so far been found. While there has been little systematic survey specifically directed at finding colonial period sites, the presence of the Swartruggens cluster of sites stands out. Members of the Spatial Archaeology Research Unit and others have devoted considerable time to the documentation of fine line rock art sites in the Western Cape. Regions such as the Sandveld, Olifants River Valley and the Pakhuis Pass area of the northern Cederberg, have been intensively surveyed and thousands of fine line images have been recorded. It is, therefore, significant that few colonial period sites have been found in these areas, in contrast to the Swartruggens. Preliminary surveys have also been conducted on the Roggeveld Escarpment, further to the east of the Tanqua Karoo (Fig. 1), and although there are many precolonial sites none have yet been found that are explicitly colonial in content. Outside of the Swartruggens only isolated colonial period sites have been found. These are, for example, Diepkloof Kraal Shelter near the eastern, upper end of the Verlorenvlei and the well known Heidedal 'galleon' near Porterville (Fig. 1).10

The isolation of the Swartruggens, the relative difficulty of getting there and the structure of the habitat combined to resist and delay submission of the area to colonial encroachment. European stock farmers increasingly drew the grazing of the Swartruggens into their seasonal orbit and by 1728, some colonists had gained a foothold in the region. A final bout of Khoisan resistance was put down in 1739 and thereafter people of indigenous descent in the Swartruggens subsided in the backwash of the colonial frontier as it moved further on into the interior. Nigel Penn's work vividly portrays how the area in its relative isolation, provided a temporary refuge for escaped slaves, employees of the Dutch East India Company (VOC) who were disgruntled with their lot, and of course the rapidly collapsing remnants of the Khoisan world.11 In the second half of the eighteenth century those people of Khoisan and mixed descent had been stripped of any independent economic means, and were forced, practically as slaves, to labour on European farms. In this context overt acts of defiance continued and 'escaped' labour could still evade capture in the rugged nooks and crannies of this region.

It is tempting to correlate the discrete distribution of colonial rock paintings in the Swartruggens with the historical character of the area, both before and after the closure of the frontier by the mid-eighteenth century. There is much grist in this interactive mill that could have provided the spur for indigenous people to ritually repel or try and cognitively account for the inevitable inroads made by the colonial world.12 In the art that is explicitly colonial in content, however, there is nothing that would seem to express the desperation of people in the final years of their independence. In contrast, it has been suggested on the basis of certain motifs in the art, such as horse or mule drawn wagons, and the complete absence of oxen and ox wagons that this art has a later date, and the late eighteenth and even early nineteenth century has been suggested.13 We argue below, moreover, that even this chronology is too early for some of the art, which was painted well over one hundred years after the Swartruggens frontier had closed. We suggest that the discrete distribution of colonial rock art panels in this region that emphasise horses, and in particular wagons, was nevertheless driven by an identifiable historic event - but much later in date than previously assumed. This was the increasing tempo of European travel through this region to gain access to the interior to the north and north east, and in particular the massive movement of people and material across the Ceres Karoo upon the discovery of diamonds in the northern Cape in the late 1860's.

Before presenting some evidence for this, a few more comments on the distribution of colonial rock art sites can be made. As has been pointed out, what is curious about the 'puddle' of colonial rock art in the Swartruggens is the contrasting absence of colonial period art in the other areas of the Western Cape. If the art in its general purpose passes indigenous comment on the open and closing phases of the colonial frontier then why do we not find similar imagery in areas that experienced the same process but earlier in the eighteenth and seventeenth centuries?14 Why do we not see such images closer to Cape Town or across the Sandveld, in the Piketberg, which was a known refuge for disaffected people from the colony and indigenous people alike, or into the Olifants River Valley beyond the Piketberg plains? This absence really does highlight the specificity of the Swartruggens distribution.

This question assumes, however, that even in initial encounters, painting as one response to those encounters is identifiable as such because it depicted the world of the coloniser.15 An art of early contact, however, could have, and perhaps more logically, would have framed a painted response using content, symbols and metaphors that were conventionally indigenous, and consequently, an art of initial contact could very well be there but is 'invisible' because we are not seeing it in these terms.16 We might expect an earlier period of seventeenth and eighteenth century contact art in the Swartruggens as well. This possibility is only a partial response to the question as to why we do not see art with explicit colonial content elsewhere here one would still expect to see a later phase. Whatever the precise reason, it does draw further attention to the seeming discreteness of the Swartruggens art.

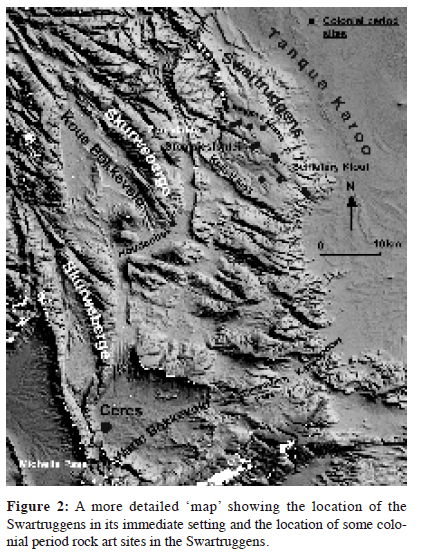

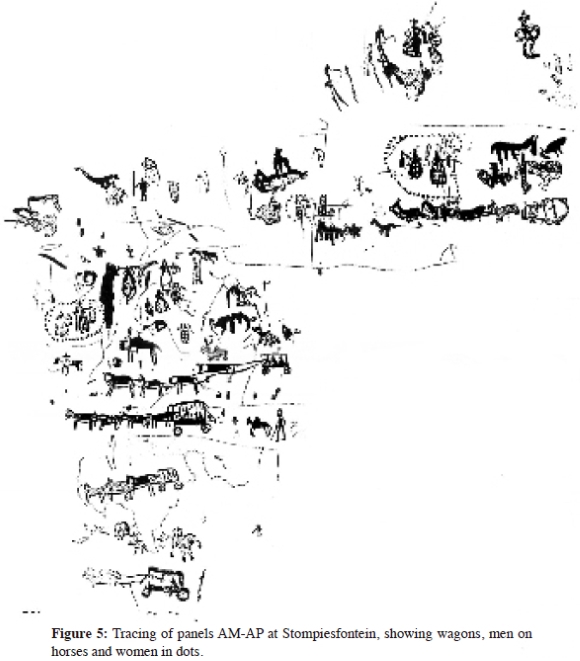

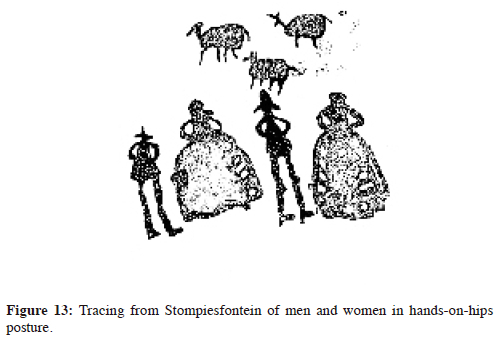

Up to this point we have avoided specific reference to the actual images. We do so now in order to develop our arguments for a later nineteenth century date for some of the colonial panels. In the Swartruggens these panels comprise a limited and repetitive set of motifs. These comprise men in European apparel, most notably wide brimmed hats and boots, and women in crinoline dresses and kappies. Some men are depicted smoking pipes and firing guns. Horses and mules are a dominating theme. Men ride them and drive them as pack animals, horses stand obediently by while men dismount and shoot guns. Horses or mules are depicted feeding at troughs, hobbled, running free, and most importantly, harnessed to pull wagons. It is this combination that is examined in detail. While horses are a common motif in rock shelter panels from the Swartruggens, horses pulling wagons are, on current evidence, limited to sites on the farms Groenfontein and Bloubosfontein (Kagga Kamma) (Fig. 2).17 One large site on Groenfontein is more commonly known as Stompiesfontein and there are several other smaller painted sites close by. It is panels from the main site that provide the basis for much of the following discussion on the chronology of this art.18

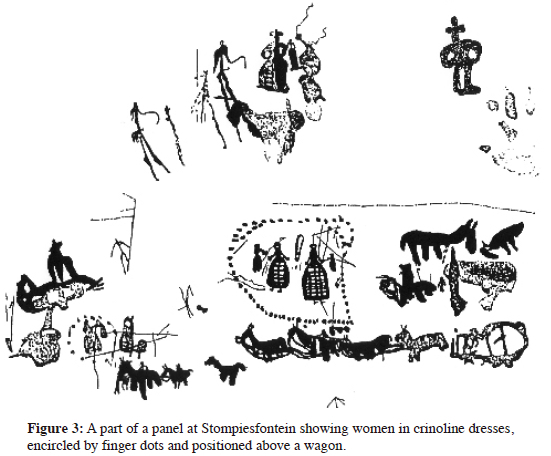

One preliminary strand of chronological evidence that places much of the Swartruggens colonial art in the nineteenth century is the female dress style. The artists have emphasised the long bell shape of the dress and a cinched, possibly tightly corseted waist (Fig. 3). Many of these dresses are patterned with vertical and horizontal stripes while the remainder have been filled completely with pigment. This shape and style suggests that these are crinoline dresses that dominated western female fashion between 1830 and 1860.19 A stiff horsehair and linen petticoat provided the desired bell shape that was increasingly exaggerated until the layers of heavy undergarments were replaced by a cage made of spring steel hoops that were bound to the desired bell shape by cotton tape. This innovation occurred in the 1850s and was replaced by a lighter crinolette in the 1870s. The grid pattern was apparently a popular fabric design during this time, although the possibility that the actual cages were painted is intriguing.20 Within the limits of the painting technique we think that the artists were specifically depicting this style of dress, and were clearly familiar with it.

Attention to this detail in the paintings may refer to the continuing and central role of outward appearance, especially clothing, as a means that materially defined people's status and rank in Cape society during the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. For instance, the authorities used legal means, such as sumptuary laws and regulations that controlled what slaves and others could wear as a means to materially and visually define order, position and status. In the Bokkeveld and Roggeveld the violent excesses of some droster gangs hinged in part, on material deprivation, and more specifically on a desire for clothing. Slaves, drovers and their women deserted their masters and for brief periods robbed and murdered and sought refuge from capture in the deep recesses available in this landscape. Upon re-capture, for example, Adam, an escaped slave from the Roggeveld, confessed that 'he had run away because he had not been given any clothes'.21 The same applied to hats, dresses and trousers as well as brandy and, the ultimate sign of power and domination, guns. The emphasis on Europeans and the accoutrements of their status in the colonial imagery may in part reflect the continued desires of people who had a long history of being made to look different and feel inferior.

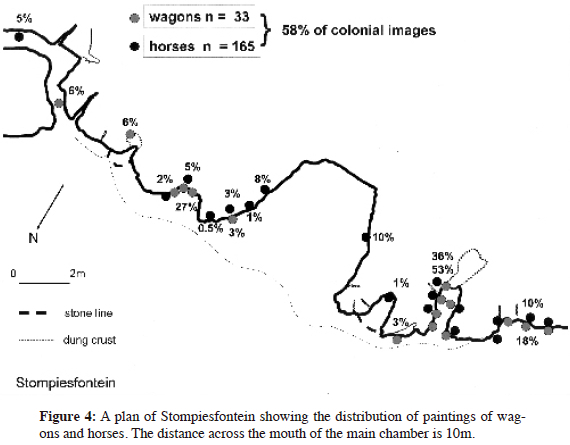

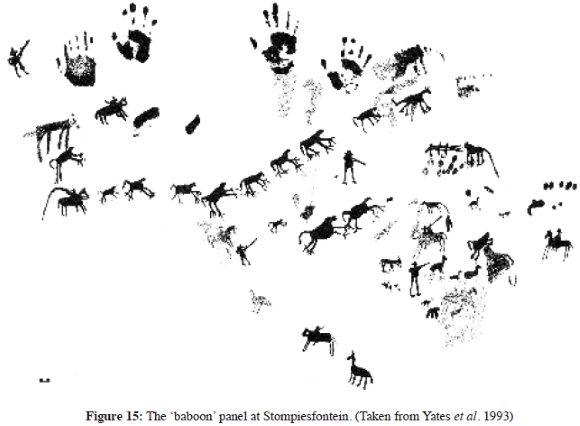

The main strand in the chronological cable, however, focuses upon the depictions of horses or mules, the necessary road infrastructure that horse and mule drawn wagons required and the design of the wagons. Horses and horse pulled wagons dominate the Stompiesfontein colonial art and even more so at Bloubosfontein. The artists have in most cases given single minded attention to them, and other domesticates such as sheep, cattle or oxen, or indeed wild bovids are ignored.22 One of the only other identifiable animals at Stompiesfontein is the baboon. There are about 340 individual colonial images at Stompiefontein of which 33 are paintings of wagons and about 165 of horses. This is well over half of the total (Fig. 4). A significant percentage of these motifs have been placed around and within a number of alcoves on the western side of the main shelter. This distribution is returned to below.

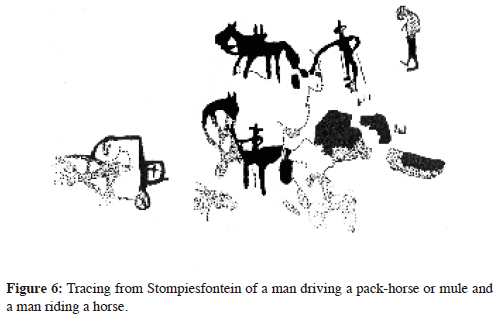

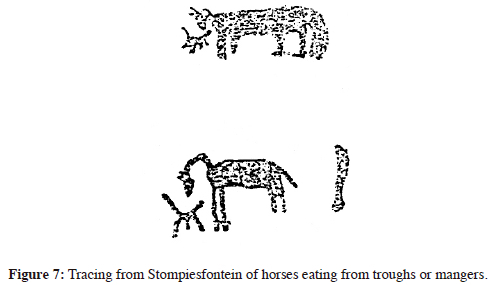

The horses and wagons stand out in the Stompiesfontein gallery (Fig. 5). All the wagons are depicted in profile and are pulled by four, three or two horses that in reality would translate into teams of either eight, six or four horses. Teams of eight and six horses are most prevalent. The traces, harnesses and reins are carefully depicted and in some cases lines have been drawn below the horses' hooves that presumably were intended to represent the road.23 Invariably, the male driver or drivers of these wagons are clearly identified, because they wear wide brimmed hats and some wield long whips that urge the horse team on. In all cases the artist has shown the interior of the wagons and it is clear that these wagons were all transporting people, both men and women, and also perhaps children. Intermingled with the wagons are men driving pack horses or pack mules. The artists have taken care to show the pack and without exception a man walks behind the animal driving it with either a stick or whip that is invariably held in the right hand. Some men ride on horseback and other horses roam free (Figs 3 & 6). In other panels, horses or donkeys are shown eating from mangers (Fig. 7). A repeated feature in the wagon panels is the inclusion of women who are always positioned above the wagons and some are encircled by finger dots (Figs 3 & 5).

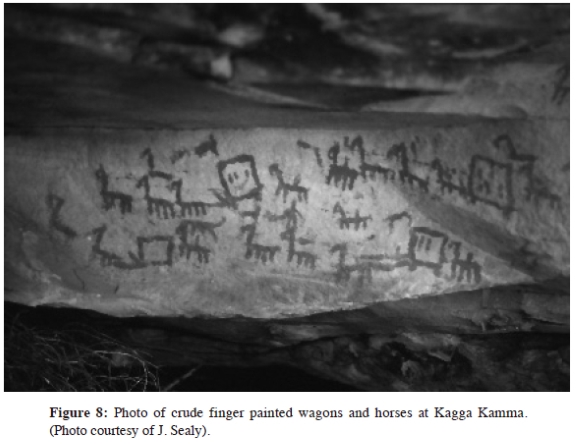

All the colonial motifs in these panels compositionally respect each other. There seem to be few superimpositions and their overall layout encourages the view that the colonial images in these panels cohere in an integrated 'scene' and were collectively painted in a single painting episode, or perhaps several, but over a short time period. Panels at Kagga Kamma significantly focus on wagons and horses and are devoid of the busy 'scenes' and varied imagery of the Stompiesfontein panels (Fig. 8). These images are also true finger paintings and the horses are schematic 'combs' with necks, and the wagons are painted as simple boxes and, unlike the spoked wheels at Stompiesfontein, the wagon wheels are red blobs.

The detail provided in the Stompiesfontein wagon images, and to a lesser degree at Kagga Kamma, encourages us to describe these wagon 'scenes' as depicting a formal transport system rather than the expedient and more casual travel associated with day-to-day life in a rural area (Fig.5). As noted previously, the use of horse drawn transport has been identified as a later development that suggests an early nineteenth century date for this art.24 In other contexts and well into the nineteenth century, the ox wagon was normally depicted.25 We now discuss the development of the 'formal' Cape transport system through the nineteenth century and the dates at which critical infrastructure was developed, which became necessary for higher speed horse and mule drawn wagons and carriages.

The development of a better road system in the Cape in the nineteenth century was first directed at the route from Cape Town, into the southern Cape and on towards Grahamstown and the Eastern Cape frontier. Rapid and efficient transport of mail was necessary to facilitate military command and commercial transaction. Access to the Overberg, and the route east, opened to horse drawn transport in the 1820s and especially with the opening of Sir Lowry's Pass in 1830.26 Prior to this the route first went northwards into the Tulbagh basin and then eastwards through the Roode Zand Kloof and then onwards to Swellendam (see Fig. 1). The horse-drawn post cart significantly reduced travel time, but with the addition of passenger facilities it also required timetables and schedules. Speed and scheduling demanded a higher level of organisation at outspans that were placed at regular intervals in order to provide fresh teams for the next relay.

The Warm Bokkeveld (Ceres Basin), Koue Bokkeveld and Ceres and Tanqua Karoo remained marginal to these early improvements in the Cape road system. The imperatives that drove the road and transport system eastwards did not exist for the north-eastward route into the interior. It was only with the opening of Michell's Pass in 1848 and the establishment of Ceres a year later that the Koue Bokkeveld became more accessible to horse-drawn wagons and coaches.27 There was, however, no specific drawcard that encouraged large scale travel from Ceres, over the difficult Theronsberg pass through the Karoopoort and across the Ceres Karoo towards the Roggeveld and the deep interior (Fig. 2). The relatively retarded pace of road development in the direction of the Koue Bokkeveld and Swartruggens, though circumstantial evidence, makes us doubt that the Stompiesfontein and Kagga Kamma wagon paintings reflect events before 1850.

This suggestion assumes that the Swartruggens artists did not themselves travel closer to Cape Town and the southern Cape, and so never experienced the development of the Cape horse drawn transport system first hand and outside of their own geographic context. This assumption is supported by the form of the wagons depicted in these paintings which differs from some of the long distance vehicles used on these other routes; the post carts and mail coaches in particular. There is sufficient detail in the wagon paintings, despite the limitations of the painting technique, to show that the Swartruggens artists did not simply paint a generic horse-drawn wagon. On the contrary, a comparison between the paintings and wagons suggest that the artists emphasised a specific type.

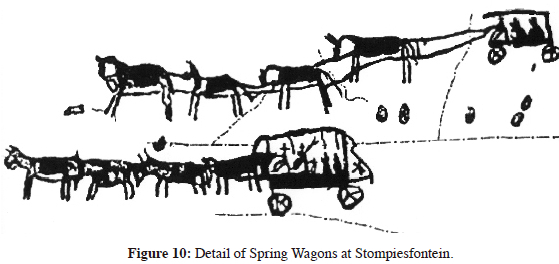

It seems that the first post carts were relatively simple vehicles. After 1852 the manufacture of mail carts was standardised in order to provide 'waterproof "wells" or boxes and to be able to carry at least two passengers'.28 Clearly the Stompiesfontein and Kagga Kamma wagons had a much greater capacity to transport more than two passengers. Rozenthal goes on to quote from The Cape Postal Guide of 1959. 'At present the mail carts employed by the various contractors differ considerably in form, fashion and build. The architectural order to which they belong as a class, is a rather nondescript one...The best idea of their appearance may be formed by imagining a cross between a costermonger's wain and a dog-cart, with all the capacity of the former and the lightness, though unhappily not the comfort of the latter'.29 Dog-carts, in the nineteenth century sense of the word were horse-drawn two-wheeled passenger vehicles in which the seats were positioned back-to-back. Both vehicles described above were open. The Stompiesfontein and Kagga Kamma paintings clearly depict larger four-wheeled wagons, and the passengers travelled under cover. The mail coaches of the second half of the nineteenth century were of an altogether different scale. The depiction by Charles Bell of a Royal Mail Coach on the road between Cape Town and Swellendam, shows a substantial vehicle drawn by eight or ten horses, and driven by a team of two men (Fig. 9). The most sophisticated coaches were the classic Concord Stage Coaches made by the firm, Abbot-Downing and Co. in New Hampshire and 59 of these were imported into South Africa.30 There are some similarities between the Concord Coach and one of the Stompiesfontein wagons, particularly the angled canvas or wooden boot cover at the rear of the wagon (Fig. 10). But the drivers and some of the passengers were on the outside of the Concord coach, something that the Stompiesfontein artists would have observed if present. In all the Stompiesfontein and Kagga Kamma wagons, the drivers are depicted on the inside of the wagons.

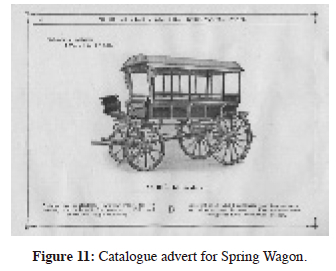

We suggest that many of the wagons depicted in the Swartruggens are of a type known as the Spring Wagon or the Spring Wagonette (Fig. 11).31 These were a South African design and were manufactured in Paarl and Wellington (Wagon Makers Valley) in great numbers in the last third of the nineteenth century. Significantly, this wagon was only fully developed from the 1870s with the discovery of diamonds in the Northern Cape and in response to the huge demand for transport from the Cape, northwards to the diamond diggings. Comparison between some of the painted wagons (Fig. 10) and the advert for "The Explorer" (Fig. 11), suggest that this is a good match. As already noted, the position of the driver is at the front, and inside the wagon and is on the same level as the passengers. Most telling is the blocky rectangular design of the wagon and in particular the straight, flat and thick, wood panelled bed of the vehicle. The artists consistently paint this feature. The wheels are clearly painted with spokes, and some back wheels are larger than the front wheels, which is correct for a Spring Wagon.32

The detail of the painted wagon in Figure 10 suggests further similarities. The artists have without exception depicted the wagons with open sides and in all cases the intention has been to show the passengers seated in orderly ranks inside. Opening the wagon sides is achieved by rolling up the cloth or canvas flaps which then provides a number of open 'windows'. The artist has painted the detail of this design and shown the dividing uprights between each 'window'. Furthermore, the artist has also included the roof overlap at the front and the back of the wagon as well as the wooden boot extension projecting from the back. This boot extension and the window frames are features depicted in several of the other Stompiesfontein wagons.

Our contention then is that most, if not all the painted horse or mule drawn wagons at Stompiesfontein and Kagga Kamma represent designs that date from the second half of the nineteenth century and more specifically, from the 1870s. If this identification is correct, then most if not all the wagon paintings are of a similar date. We can also chronologically bracket these images and suggest that they were not painted after 1885 when the railhead reached Kimberley. As trains pushed inland through Touwsrivier, Laingsberg and Beaufort West, steam superseded horse drawn transport and the Ceres route faded in importance and became the forgotten highway.33

Horses or mules are a feature in almost every panel at Stompiesfontein and at Kagga Kamma. Given that there is a sense of coherence in all of these scenes, it may be that panels without the diagnostic wagons are also of a similar date, but we have to be cautious about generalising. We also need to be circumspect about identifying the rapid and massive surge of people and material northwards to the diamond diggings in the Northern Cape from the late 1860s as the informing historical event that impacted the experience of individuals at a small and local scale within such a limited area. These paintings are between 50 and 60km to the north of a highway that originated in Ceres and nudged closest to the Swartruggens where the route either cut diagonally north eastwards across the Ceres Karoo to an outspan at Hangklip below the Roggeveld, or eastwards towards Pataties River and then onto Beaufort West (Fig. 2).34 Although the Swartruggens is marginal to this main route, it is unlikely that other routes closer to the Swartruggens did not experience a similar surge in traffic. The road northwards up the Ceres Karoo to Calvinia, for example, runs immediately at the base of the Swartruggens wagon sites less than 10km to the east (Fig. 2).

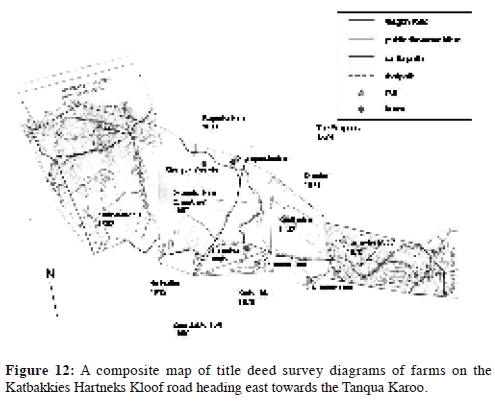

At an even smaller scale, Groenfontein and neighbouring farms were served by the main east/west route from Houdenbek at the base of the Skurwerberge, that ran across the Riet (Winkelhaaks) River, up the Katbakkies and then down the Schietery Kloof to join the Calvinia road (Fig. 2). Outspans had long been established on Hartneks Kloof at the top of the Schietery Kloof, at Kliphuis and at the base of the Katbakkies pass. The first title to Groenfontein (Stompiesfontein) was granted in 1862 and the survey diagram labels this route as 'a wagon road to the Karroo', and it ran across the farm near its southern border (Fig 12).35 The route up Katbakkies and down the relatively gentler slopes of Schietery Kloof to the Tanqua Karoo was in use well before this time and probably from precolonial times. It provided passage for the seasonal trek of livestock down to the Karoo during the winter months.36 The road shown on the Groenfontein title deed map takes a slightly different path to the current road and this old road needs to be relocated.37 Whatever route the public road took through Groenfontein, the Katbakkies ridge east of the Riet River would have presented a formidable barrier to any wagon.38

Having made a suggestion about the date of some of the colonial rock art in the Swartruggens and linked this to the unprecedented surge of diamond rush traffic around and through this region, we now consider why individuals (or a community) expressed their experience of this event by painting. We assume that the contrast between the scale of the event and the mundane rhythms of everyday life was sharp, but it would seem pointless to suggest that the painters were simply moved to record the event only as a narrative. How did the large scale event interact with personal experiences to produce a local statement in paint? What motivated the painters to depict other people, as they rushed northwards seeking wealth and fortune?

Transcribed events

We have suggested that some of the Swartruggens art dates quite late in the nineteenth century and that the diamond rush to the north was an event that provided the motivation to paint some of these panels. Despite the passage of early travellers and farmers over various forms of this 'highway' for 150 years, the scale of this event stands out. If our historical reconstruction is relevant, then this provides some context to think about how the local scale may have articulated this larger historical process. Providing such a context does not, however, lead us to meaning. The production and consumption of this art was local and the need or the motivation to paint stemmed from local social, political and economic conditions of the farm labourers, squatters, drovers and shepherds - whom we assume were among the artists. This is where the emphasis is placed in developing some ideas about meaning. As indicated in the introduction, however, we range outside the specific wagon panels discussed above because the colonial rock art sequence is probably more complex than these. Details such as personal experience, heterogeneity within subordinated communities, different events and local conditions must have continually recombined to produce different motivations and meanings.

We start with the idea of the art as political action that comments upon the asymmetry of relations between labourer and master, but that may also refer to unequal relationships between labourers themselves, such as between shepherds, foremen, or even men who had worked as transport riders. A first step in this discussion is to ask who it was that the artists painted? Do their images focus purely on Europeans and 'masters' or were they perhaps painting themselves and also framing themselves in these scenes? Are the paintings a combination of 'us' and 'them'? How do we go about forming an opinion on this question and what evidence is there in the paintings that might clarify who it is that was depicted?

It can be assumed that the wagons and the horses were the property of Europeans. Most, if not all, of the passengers depicted in the wagons are also probably Europeans (Fig. 5). In some instances it was clearly important for the artist to distinguish between men and women, and we also think that some diminutive figures are children. The identity of many of the human figures associated with the wagons as well as those painted outside the immediate context of horses, mules and wagons can also be safely identified as European. This is because they are consistently painted in a characteristic hands-on-hips posture (Figs. 13 and 5), and even some of the passengers inside the wagons are painted in this way. This posture is a universal convention employed by contact period artists around the world in their depiction of European colonists.39 It clearly alludes to the possession of trousers and pockets for hands, but not completely, because women are also treated in this way. This convention, however, possibly shifts between an innocent and inert observation and the mockingly seditious for it potentially makes a wry comment about a posture of arrogance and people in possession of idle hands.40 This posture pervades the Stompiesfontein art, as well as the other colonial period sites in the Swartruggens and further afield, and it is Europeans who are the subject.41 Furthermore, the men driving pack horses or mules at Stompiesfontein are typically painted with a whip or stick extending from the right hand, while the other arm is akimbo on the left hip (Fig. 6). Clearly, it is also European men who drove these animals. The somewhat clumsy combination of walking and holding a stick in one hand while the other arm rests on the hip suggests that this is a statement about attitude rather than a record of a natural stance. This may also apply to men riding horses with the same posture (Fig. 6).

In contrast, there is nothing explicit in these panels to suggest that the labourer or shepherd painted him or herself into them, but in most of the well-preserved images of wagons at Stompiesfontein, the drivers are always prominently depicted, sometimes even more so than the passengers. Using other sources it is clear that men of Khoisan descent were employed in the transport industry as drivers. Charles Bell's painting of a Royal Mail Coach clearly shows this and there are ample references to their skill and expertise as drivers (Fig. 9).42 With both hands on the reins, no paintings in which the wagon driver is clear were painted with the hands-on-hips posture. In the only example at Stompiesfontein of a wagon on an incline, the whip is clearly in strenuous use as the horse team is urged uphill. While this may well express the prowess of the driver, such portrayals do not necessarily mean that they were intended as egotistical statements by men or women who worked in this transport system and wished to depict their important 'status'. We conclude that if the artists inserted themselves into some of this art their presence was not obviously or intentionally emphasised. The people, events and episodes depicted are of the Europeans' world, and the art seems to be all about 'outsiders'.

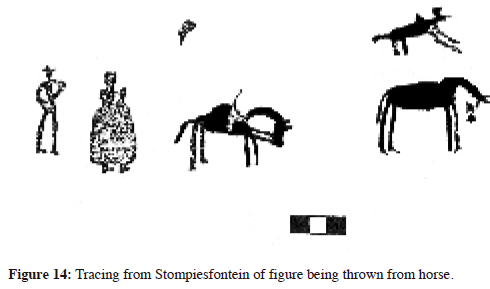

And yet, we cannot escape the considerable energy, life and detail in these panels that suggests that the artists were intimate with the contexts portrayed. This may mean that what made the larger event salient in the lives of the artists was their personal involvement with that context. Moreover, there is some quirky detail in these panels that suggest that the motivation to paint arose from actual episodes and events and were not generic depictions of a general process. Herein lies a possible key to the intent of some of these panels, for some of this detail is specific enough to suggest that the artists were expressing a muted schadenfreude. Indeed, much of the art may 'function' in this way, but because we cannot recognise specific intent in the depiction of the everyday, we have to rely on a few of those obviously quirky images to amplify this idea. This is important because it shifts the act of painting and the consumption of the images to one of purposeful comment. In the privacy of his/her own community the artist could be explicit about feelings that were necessarily suppressed in the public domain.

One such comment is possibly portrayed in Figure 14 where the trivial event of two men (the pigment in the left-hand figure has faded), being thrown from their horses is portrayed as a man and a women look on. This suggests that it was an event that the artist, presumably as a first-hand observer, took delight in recalling. That the artist was privy to this is suggested by the detail that he/she strove to provide in the images. The tense arch of the horses' necks and the tight thrum of reins in the left-hand image contrasts markedly with the generally languid manner in which horses are depicted, with drooping, loosely held reins (see Fig. 6). One can imagine that the act of painting was a humorous re-enactment that was also verbally played out both in the painting and in the consumption of the images for the benefit of others who were not direct witnesses to this event.

Other scenes also suggest humour and parody. One is suggested by the diminutive figure painted inside the boot of one of the Spring Wagons (Fig. 10). Here the figure is isolated from the rest of the passengers in the wagon and seems to hang onto the canvas flap with one extended arm. One can only speculate on what this specifically portrays, but it is sufficiently different to acknowledge that it is out of the ordinary. In another panel a man is shown hitting his head against the roof of the wagon having been jolted out of his seat, while next to him a fellow traveller is seemingly in a similar predicament, but upside down. In yet another panel an artist has painted two pairs of men and women, all in the typical hands-on-hips posture, but has perhaps mischievously juxtaposed the excessively voluminous profiles of the women, with spindly legged males. Other panels show detail that is not obviously humorous but is nevertheless distinctive, and suggests that a particular event is being recalled. In two other wagon scenes men stand behind wagons with right arms outstretched and hold some kind of extension that touches the rear of the wagon. The left arms are typically akimbo. One of these extensions is more complex and seems to reach through the rear of the wagon to connect with the outstretched arm of a passenger.

We will never be able to decode the individuality of each episode and the impacts and impressions that willed the artists to re-enact those events. We do suggest that the intention of re-interpreting them in a collective way or from a personal point of view was in order to give satisfaction, like participating in a duel but outside the line of fire. In the absence of a quirky scene, specific intent can never be re-imagined once the artist and onlookers have moved on. Consequently, the notion that the art was parody is largely theoretical, and even more so at sites like Stompiesfontein. With several panels and many images, it is not possible to even attach the larger scale historical context we have suggested above on the basis of the horses, mules and wagons.

However, if we do not work with the idea of this art as social action then each panel may be reduced to an inert and bland narrative. One specific panel at Stompiesfontein makes this point. This panel, which we feel can safely be called a scene, seems to portray a universal rural or farm theme. The central motif is a troop of what seem to be about sixteen baboons that flee in animated action as they are harried by men and horses (Fig. 15). The fingers and toes of these baboons have been painted in a splayed and exaggerated manner. Some of the men ride with guns slung over their shoulders, another wields a whip, while others are dismounted and shoot in the direction of individual baboons, one with his horse standing obediently by. There are no wagons (or women) in this panel, and there is nothing specific in the content that dates it, but there is also nothing that would preclude a date equivalent to that suggested by the Spring Wagons. At face value this panel seems to depict a generic day-to-day rural nuisance. We would suggest, however, that the effort expended in painting this scene meant that the event was of personal salience to an individual or group: it was more significant than possibly mere delight in the ire of the shooting men. In the absence of other information, however, the specific reason as to why this event was recalled will always be lost.

There are elements in this art, therefore, that suggest that painting events and looking at and talking about them were possibly private re-enactments and conducted off-stage 'outside the intimidating gaze of power'.43 In these private performances, subordinates perhaps more freely expressed their anger, envy, egos, desires and fantasies. Painting and the consumption of the images may be seen as broadly seditious although these images do not capture the apocalyptic desperation ascribed to the art of imploding San worlds, nor any sense of explicit interpersonal violence and potential revenge, that the brutal dispossession of land and resources suffered by Khoe and San people in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries might have engendered.44 If the art was intended to pass comment 'out of earshot of powerholders', we need to turn our attention away from the images to a brief consideration of the rock shelters that received them.45 Can we make any suggestions about how they were seen as place? Were these places private and off-stage?

In order to do this, one approach is to consider how these painted places fitted into a wider network of other contemporary places in these farm contexts. For the San, rock shelters were fundamentally domestic places where the core social actions that defined identity took place. The ritual and social action within which painting and paintings were created and consumed was an indivisible part of the domestic domain and paintings were open to all.46 In contrast, the nature of place may have changed significantly in the more recent period when these shelters received handprints and finger dots. For the mid- to late nineteenth century colonial period it seems reasonable to suggest that shelters which were used for painting were not primarily living spaces and that the 'permanent' domestic dwellings of shepherds, labourers and their families were elsewhere. Shelters such as Stompiesfontein and Hartneks Kloof, however, were used as sheep kraals because the top layers in these shelters comprise relatively thick layers of livestock dung. In this role, these shelters may well have been places where some of the painters worked and whiled away time watching over sheep. A few fragments of refined earthenware and wine bottle glass on the talus slope in front of Stompiesfontein may be linked to this.

Other than the faint trace of a circular stone kraal a few hundred metres east of Stompiesfontein which is possibly of precolonial age, there are no indications of historic settlements near the site, the closest being over a kilometre away to the north east on the northern edge of the upper section of Joubertskloof.47 There is a spring and seepage here and this may be the 'Stompiesfontein' marked on the Groenfontein title deed map of 1862. There are no dwellings or structures marked on this map anywhere near the painted shelter of Stompiesfontein, the closest being towards the southern edge of Groenfontein in the vicinity of the Katbakkies/Schietery Kloof road.48 One of these structures is marked as 'F. Lentner's house', who, according to Anderson, was a Baster who owned Stompiesfontein which was a subdivision of Groenfontein.49 Lentner's house, however, is about 7km from the painted shelter of Stompiesfontein (Fig. 12).

Our conclusion is that the painted site of Stompiesfontein was not a domestic place and that the act of painting fell outside this day-to-day context. We are circumspect, however, in reading too much into this in terms of painting as a furtive and clandestine act, because this was a relatively empty landscape, and privacy for a subordinate must not have been hard to come by. Furthermore, we need to assess each colonial painted site individually and plot their positions in relation to the wider context of roads, paths, springs, farmsteads and the identifiable remains of labourers cottages or even more impermanent structures and if possible, build a chronological picture of how the colonial landscape developed through time.

We may also think of privacy less in political terms and more in a ritual sense in that sites could have been sought that provided a suitable degree of social separation from the domestic domain. At the start of this paper we set ourselves the task of furnishing a more specific historic context for some of the art and within which some preliminary ideas about the meaning and motivation of the art can be developed. We have suggested that there was considerable dislocation between precolonial and later worldviews. Consequently, we have outlined some ideas about the paintings of this later colonial period as political comment that was grounded in the contemporary realities of a subordinate position. For this reason we sought to downplay continuity. We now return to this theme and make a few observations from Stompiesfontein and other sites that may temper this view.

The position of panels within Stompiesfontein is potentially relevant here because decisions about placement may have been made with the intention of elaborating meaning. Almost 80% of the colonial images were painted in the western end of the shelter (Fig. 4 gives the percentage distribution of horses and wagons, and this pattern does not change when the rest of the colonial images are added). The number of motifs painted in the main chamber at Stompiesfontein is peculiarly low. It is in this main chamber, however, that a significant dung crust is found and the reason for the small number of images there may simply reflect that kraaling sheep pushed painting activity to the margins. This is not an entirely satisfactory explanation, however, because painters chose alcoves and recesses to paint a significant number of horses and wagons (Fig. 4). The main alcove on the western side of the main shelter, for example, is deep and dark and it must have been difficult to paint in it. This location also seriously restricts the number of people who can view the images at any one time. Other wagon panels at the western end of the shelter are much more public. Furthermore, the combination of where to paint and what motifs were appropriate in specific places may repay formal analysis at sites like Stompiesfontein. Women are consistently a part of wagon scenes associated with alcoves and recesses, but and it may be significant that there are no women in wagon panels that are on open, and exposed rock surfaces. Furthermore, on the eastern side of the main chamber, there is a small alcove that is difficult to enter, because it requires the painter and the viewer to stoop and crawl in. There are, however, two wagons painted in this alcove low down on the left hand side. In such cases the artist may have simply been perverse, but alternatively, painting in recessed locations may have been a deliberate choice because in such cases painting was a private act, or the location was essential for elaborating meaning.

A sense of within the rock, or going into the rock is obvious but it is best not to push this idea too far. Our purpose here, as stated above, is to raise the idea that shelters such as Stompiesfontein may still have been culturally secluded and private spaces, even through the surrounding land was owned and occupied. Additionally, we should also not lose sight of the possibility that seclusion from the day-to-day domestic domain was desired and required by a particular group within the community. Defining painted shelters as special places in this historical context may well have been based on continuities with precolonial ritual and social practice. In this regard, Gavin Anderson has suggested that handprints stratigraphically occur underneath, with, and on top of the colonial images.50 He goes on to argue that handprints and finger dots that co-occur with the colonial images were the work of Khoe women, and that this expressed solidarity as an oppressed group in rural areas and on farms.51 Clearly, Anderson sees continuity between the precolonial past and the historic period because he believes that Khoe women painted handprints in both periods.

Without going into the details of his complex argument, several points can be raised. The first is that the stratigraphic position of handprints in relation to colonial imagery requires more work. At Diepkloof Kraal Shelter on the Verlorenvlei, for example, handprints, without exception, pre-date colonial images, although this relationship is relative and the time elapsed between the two is unknown.52 There appears to be variability in the stratigraphic relationship between handprints and colonial images. At a regional scale, this may hint at the different rates between areas at which Khoe were culturally subdued and the nature of this process. The Swartruggens and the Koue Bokkeveld, even after the frontier had fully closed, was a marginal area and this could have encouraged greater continuity in Khoe cultural practice. As an empirical issue, it remains to be seen whether the handprint and colonial images in the Swartruggens do consistently overlap. Where handprints are contemporary with colonial images, it would be important to assess whether there is any pattern in their placement.

Anderson links handprints to Khoe women, both as painters and also as vehicles of meaning about women. Although these handprints are seemingly contemporary with colonial images, he suggests that the latter were not painted by the same people.53 Whether one accepts this specific interpretation or not, it does correctly touch on the possibility that it is dangerous to homogenise 'painters' as a singular category and that the meaning and motivation behind individual panels could vary significantly depending on who painted them. Presumably there was significant heterogeneity in the social categories of rural labour, and this in turn may also have influenced the possession of historical and cultural knowledge. Men and women, and their specific interests are an obvious distinction, as would be distinctions between men who held a different status depending on their position within a subordinate pecking order, and we have suggested above that people who worked outside of the immediate farm context may have earned a different status. Formal analysis of motif positioning on a site by site basis may open up the possibility of identifying different panel structure, such as the category of 'procession', for example, among precolonial San art.

At Stompiesfonein the placement and treatment of men and women are suggestive in this regard. In several of the larger composite panels we can identify a repeated pattern in the placement of horses, men associated with horses and men driving wagons on the one hand, and women and possibly children, on the other. Men, horses and wagons consistently cluster in the lower section of panels (Fig. 5), while women and children are, without exception, always painted above wagons, horses and men associated with horses. The lower sections of these panels are all about movement and action that is linear in motion, mostly from right to left (from the viewers position), as men ride horses, drive pack animals and drive wagons. In another large panel that has no wagons, horses populate the lower section, and many of these are shown eating from mangers. In contrast, women in the upper sections are static, painted standing and face on, and significantly, in several cases they are bound within circles of finger dots and children also seem to be included (Figs 3 & 5). Furthermore, in one of these panels, there are ten handprints, eight of which are clustered in the upper zone. In the 'baboon' panel (Fig. 15), handprints are also in a position above the main 'scene'.

This cursory analysis identifies a repeated pattern that most obviously draws a gendered boundary. Somewhat stereotypically, this boundary separates the domestic world of women from the 'out there' world of men. Furthermore, this distinction becomes increasingly complex if our discussion of these images about the depictions representing Europeans is correct. Why make this distinction if you are not painting yourself? One can amplify this obvious gender distinction and suggest that because thematically and numerically, male elements dominate these panels, men were the painters. This structure is not evident throughout the Stompiesfontein gallery, and the baboon 'scene' discussed above is a case in point (Fig. 15). We may suggest, however, that this painting is also underpinned by male themes, and again by extrapolation, men were the painters and male themes appear prevalent at Stompiesfontein. The other panels at Stompiesfontein need careful consideration as do other sites on an individual basis. This discussion pursues the idea that there is culturally driven structure in some of these panels.

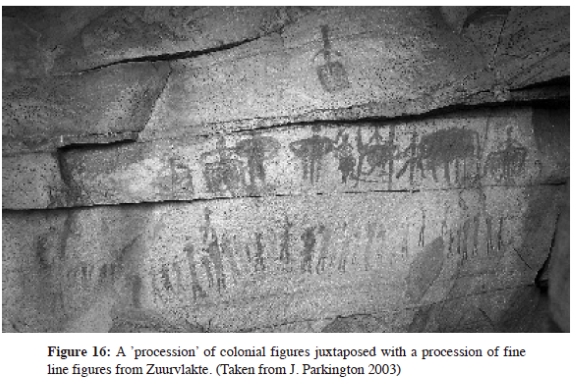

We need to be cautious, however, about placing too much emphasis on cultural structure and cultural continuity. There is, moreover, an unquestioned assumption that continuity in a form, such as a handprint, implies continuity in meaning, whatever this may have been for precolonial Khoe and San. Colonial images in the Swartruggens, for example, are invariably juxtaposed with precolonial fine line paintings (see for example Figure 5), but while colonial artists often respect the physical space these images occupy, we are not sure whether the painters intentionally juxtaposed these images to draw on and recontextualise prior meanings in their own setting.54 Colonial painters at Zuurvlakte, for example, perhaps humorously, finger painted a row of front-facing Europeans with characteristic hands-on-hips posture immediately above a procession of fine line kaross-clad figures, characteristically facing to the right (Figure 16).55 In this case the fine line panel may have been no more than a visual prompt that contributed structure to the colonial painter. Or the juxtaposition may generally have been used as a mechanism to deliberately compare and communicate ideas about past and present.

Similarly, at Diepkloof Kraal Shelter, a large colonial period hand and arm print has been superimposed over decorated handprints, but again, this may have been copying.56 Also at Diepkloof, the best known images portray five men, who have been painted evenly spaced apart across the shelter wall. They are presumed to be Europeans and they all share a common feature in the form of exaggerated and/or erect penises. Because of this common theme, it is possible that these images were painted at the same time and may have been prompted by one event, or perhaps are 'retakes' of the same event or, indeed, a single individual. It has been suggested that a contribution to understanding this feature will rely upon an indigenous ethnography that provides some inkling of prior precolonial meanings.57 But equally, portraying your master with an exaggerated penis seems like an obvious device if a subordinate wished to pass private comment on his sexual and moral character. In reality many of these colonial images may be an amalgam of a fractured cultural past that was reworked and re-entangled to give meaning to an event in the 'present'. Both 'present' circumstance and fragments of a cultural past may be important.

Conclusion

We have suggested that some of the Swartruggens colonial art dates to the second half of the nineteenth century, and that the discovery of diamonds and the rush that ensued was an event that was played out at the local level in some of the rock art. In support of this we have identified wagons in the art that date from this period, and whose development was a response to the transport needs at this time. We admit, however, that the specific linkages between this art and the transport industry based in Ceres, the transport routes, the identity of the artists, their possible work relationship to this event and to land-owners and masters, and why these sites are found in the Swartruggens is vague. We are confident, however, that the general framework we have outlined has some value within which to pursue these questions. We also need to remember that the sample of colonial painted sites is relatively small at this stage, but that systematic survey will turn up more. Furthermore, we need to understand more fully how these rural economies were structured, and how the transport industry worked in terms of its labour force. We feel that archival and archaeological research on the organisation of labour and the management of outspans would be useful in this regard.

We have also emphasised the need for interpretive frameworks that approach the paintings as an active social commentary that perhaps gave expression to the local and personal conditions of subordination within a rural economy and wider events. It is at a local scale that the wider event may intersect with the lives of people who fall outside the view of conventional texts, and who found voice by passing private comment though the art (and probably in many other ways), and in so doing wrote themselves into history. This commentary may have taken place 'offstage', and was transcribed outside the rules of subservience required in the public domain. Identifying the particularity of an event that underpinned a painted commentary is, for the most part, beyond our grasp. Furthermore, while we have suggested that it is difficult to link the dominant motifs painted in this art to prior cultural meaning, we do acknowledge that this aspect of the art cannot be ignored and that understanding the 'present' of colonially subdued Khoisan descendants must pay attention to precolonial cultural 'pasts'.

It is possible that with more directed research, variability in the content of this art will bring more focus to the question of cultural continuities. Such a future focus will ward off the danger of chronologically collapsing this genre into a single period and potentially erasing the subtleties of local sequences. Similarly, the art should also not be homogenised in terms of general dualities that deal only with subordinate or master as undifferentiated sections of the rural social landscape. Variability in the art, both through time and space, must arise from the disparate interests of groups and individuals within the general class of rural labour and their external relationships with those that controlled their labour.

* We thank Mr V. Miros for free access to Groenfontein and Paul and Jean Gray for showing us sites on Knolfontein. Tim Hart, John Parkington, Siyakha Mguni, Pieter Jolly and Antonia Malan are thanked for discussion and Shihaam Donelly for assistance. A grant from the Swan Fund is gratefully acknowledged.

1 See J Parkington and A. Manhire, The domestic context of fine line rock paintings in the Western Cape, South Africa' KRONOS 29, 2003, 30-46; R.J. Yates, A.H. Manhire and J.E. Parkington, 'Rock painting and history in the south-western Cape ' in T. Dowson and J.D. Lewis-Williams (eds), Contested images: diversity in southern African rock art research (University of the Witwatersrand Press, 1994).

2 R. Yates, A. Manhire and J. Parkington, 'Colonial era paintings in the rock art of the South-Western Cape: some preliminary observations ' The South African Archaeological Society Goodwin Series 7, 1993, 59-70; G. Anderson, The social and gender identity of gatherer-hunters and herders in the south-western Cape ' Unpublished M.Phil. thesis, University of Cape Town, 1996; G. Anderson, 'Fingers and finelines: paintings and gender identity in the South-Western Cape ' in L. Wadley (ed.) Our gendered past: archaeological studies of gender in southern Africa (Witwatersrand University Press, 1997).

3 In the KwaZulu-Natal and Eastern Cape Drakensberg, for example, studies have been able to identify and highlight both significant continuity and change in the San art through periods of interaction both with Nguni-speaking farmers and the increasingly complex cultural landscapes brought about by the colonial world. At the interpretive level, these studies show significant change in the meaning and motivation in the production and consumption of this art. Despite change, however, continuity clearly resides in the ability of researchers to identify the latent power of the shaman who progressively directs change in which group concerns are subsumed beneath the personal growth of shamans as they objectify their skill as ritual specialists and 'sell' it to the other side. Recognisable continuities also apply for the Northern Sotho colonial period art that adheres to the same conventions and rules practiced in the precolonial initiation 'Late White' art. See for example G. Blundell, G. Nqabayo's Nomansland: San rock art and the somatic past. Studies in Global Archaeology 2. Uppsala, 2004, and B. Smith and J.A. van Schalkwyk, 'The white camel of the Makgabeng' Journal of African History 43, 2002, 235-254; J.A. van Schalkwyk and B. Smith, 'Insiders and Outsiders: sources for reinterpreting a historical event' in A. Reid and P. Lane (eds) African Historical Archaeology (Kluwer Press, 2004), 325-346.

4 R.J. Yates et al., 'Rock painting and history in the south-western Cape'; Yates et al., 'Colonial era paintings...'.

5 Ibid.

6 For debates on the authorship of handprints and finger dots see W.J. van Rijssen, 'Rock art: the question of authorship' in T. Dowson and J.D. Lewis-Williams (eds), Contested images:diversity in southern African rock art research (University of the Witwatersrand Press, 1994), 159-176; G. Anderson, 'Fingers and fine lines'; A. Manhire, 'The role of handprints in the rock art of the south-western Cape' South African Archaeological Bulletin 53, 1998, 98-108; J. Parkington and A. Manhire, 'The domestic context.', 45; R. Yates et al., 'Rock paintings and history.'.

7 G. Anderson, 'The social and gender identity of gatherer-hunters and herders in the south-western Cape'; G. Anderson, 'Fingers and fine lines: paintings and gender identity in the South-Western Cape'.

8 J.C. Scott, Domination and the arts of resistance: hidden transcripts (Yale University Press, 1990).

9 Ibid., 4-5. See also M. Hall, Archaeology and the modern world: colonial transcripts in South Africa and the Chesapeake (Routledge, 2000).

10 R.T. Johnson, 'Rock paintings of ships' South African Archaeological Bulletin 15, 1960, 111-113. S.Mguni, The evaluation of the superpositioning sequence of painted images to infer relative chronology: Diepkloof Kraal Shelter as a case study' Honours project, UCT, 1997.

11 N. Penn, 'Droster gangs of the Bokkeveld and the Roggeveld, 1770-1800' South African Historical Journal 23, 1990, 15-40; N. Penn, Rogues rebels and Runaways (David Philip, 1999); N. Penn, The forgotten frontier: colonist and Khoisan on the Cape's northern frontier in the 18th century (Ohio University Press, Double Storey Books, 2005).

12 R. Yates et al., "Colonial era paintings...", 67.

13 Ibid., G. Anderson, 'Fingers and finelines.. '51

14 R. Yates et al., "Colonial era paintings...", 67.

15 As pointed out by Yates et al. this assumption, that has been implicit in the way the Heidedal 'galleon' has been seen, may be wrong.

16 In other areas of southern Africa rock art researchers have coined the term 'art of the apocalypse' to refer to a grotesque and distorted art that expresses the last futile attempts of fugitive Bushmen to resist colonial expansion. White pigment was frequently used, which probably appeals to the spirit world from which power to repel is sought. The rock art archive for the Western Cape could be revisited to explore differences in motif form and colour distinctions. Reports of white paintings from the Verlorenvlei area require close examination. See for example, S. Ouzman and J. Loubser, 'Art of the apocalypse: southern Africa's Bushmen left the agony of their end time on rock walls' Discovering Archaeology 2(5), 2000, 38-45.

17 All tracings used here are taken from the work of Gavin Anderson at Stompiesfontein. This work comprises an almost total tracing of the colonial panels from this site and this record has been verified in the field. It is from these field tracings that the summary statistics for Stompiesfontein are derived. Anderson's original field tracings are housed in the Department of Archaeology at UCT. The Stompiesfontein redrawings are adapted from G. Anderson, 'The social and gender identity of gatherer-hunters and herders in the south-western Cape'.

18 Archival research indicates that Stompiesfontein was a quit rent subdivision of Groenfontein before it was granted title in 1862, G. Anderson, 'Fingers and fine lines.. .',51.

19 'The secret history of the corset and crinoline' The Victoria and Albert Museum: http://www.fathom.com/course/21701726/.

20 In a delightful subversion of proper dress codes, Pedi women 'wore' their cages on the outside, Mandy Esterhuysen, pers. comm.

21 N. Penn, Rogues, rebels and runaways, 151.

22 We agree with Gavin Anderson, 'Fingers and finelines...'50, that most, if not all of the quadrupeds that cannot be directly identified as horses or mules because there is no associated harness, pack or manger, were also horses.

23 Many of the Stompiesfontein paintings are in fact not finger paintings and the relatively fine detail in the horse and wagon paintings indicates that the pigment was applied by some form of 'brush'.

24 R. Yates et al., 'Colonial era paintings...', 67.

25 See for example, S. Collins, 'Rock-engravings of the Danielskuil townlands' South African Archaeological Bulletin 28, 1973, 49-57, and P. Vinnicombe, People of the Eland (University of Natal Press, 1976)9, 21.

26 E.H Burrows, Overberg odyssey: people, roads and early days (Swellendam Trust, 1994)140.

27 E. Rosenthal, 'Mail coach on the veld: the history of mail coaches in South Africa' Africana Notes and News 10(3), 1953, 76-112.

28 Ibid., 81, emphasis added.

29 Ibid., 81.

30 Ibid., 89.

31 Frances Graves pers. comm. 13 October 2005. Johan van der Merwe pers. comm. 16 October 2005.

32 In most paintings of wagons, the profile convention employed by the artist means that only two wheels are shown. There is only one wagon in which the artist has shown all four wheels.

33 As far as we are aware, the description of this road as 'the forgotten highway' comes from E.E. Mossop, Old Cape Highways (Maskew Miller, n.d.).

34 The international scale and impact of this event is reflected in the almost immediate publication of guides and descriptions for travellers outlining how to prepare, what the cost was and what to expect on the journey northwards. See for example J.G. Steytler, 'The immigrants guide: the diamond fields of South Africa, with a map of the country and full particulars as to the roads, prices of necessaries, etc.' (Paul Solomon, 1870).

35 S.G. Dgm. No. 977/1862. It is of note that the first formal title deeds for many of the farms east of the Riet River were granted around the date suggested for the Stompiesfontein and Kagga Kamma wagon paintings. (Knolfontein 1862, S.G. DGM NO 979/1862; Katbakkies 1876, NO. 2357/1876; Hartneks Kloof 1870 NO. 747/1872; De Naauwte 1876, NO. 2331/1876; Zuurvlakte [No. 97] 1876, NO. 2326/1876). Whether this is significant requires further research, particularly in relation to continuity and change in the way that farm labour was organized.

36 See P. J. Van der Merwe Trek: studies oor die mobiliteit van die pioniersbevolking aan die Kaap (Nasionale Pers, 1945).

37 G. Anderson, 'Finelines and fingers...'51, claims that the remains of the Katbakkies Pass road runs in front of the Stompiesfontein shelter. This does not seem to be correct. The title deed map of 1862 shows, as mentioned above, that this road ran along the southern edge of Groenfontein. The closest road to Stompiesfontein is marked as 'Road to J. Muller and Glands Drift' and this forms a T-junction with the Katbakkies/Schietery Kloof road near the eastern border of Groenfontein. This is the road that may have run near Stompiesfontein, but it is more likely that it ran on the northern side of Joubertskloof. Stompiesfontein is located on the southern side of Joubertskloof.

38 Johan van der Merwe (pers. comm., 16 October 2005) suggests that the Spring Wagon would have found the roads and inclines of the Koue Bokkeveld north of Ceres difficult going, even with a team of eight horses. Six to eight passengers with luggage and drivers could weigh between 700 and 1000kg. The weight of the vehicle would double this figure. A hardy Boereperd could pull its own weight.

39 See for example S. Turpin, 'Rock art of the Despoblado' Archaeology Sept/Oct., 1988, 50-55, and D.S. Trigger, Whitefella comin' (Cambridge University Press, 1992).

40 See also J.A. van Schalkwyk and B. Smith, 'Insiders and Outsiders: sources for reinterpreting a historical event', 343, that deals with the North Sotho representation of the Maleboho War of 1894 with the Boers. Apart from an equal emphasis on horses in this North Sotho contact art, one section of the painting on page 343 shows three men, with hands-on-hips enclosed defensively within a stone wall redoubt. The images make a double statement about the bodily and physical facades of white men.

41 See for example R. Yates et al., 'Colonial era paintings in the rock art of the South-Western Cape' (1993) Figure 3, and S. Mguni, The evaluation of the superpositioning sequence of painted images to infer relative chronology (1997) Figure 3.

42 See for example, E. Rosenthal, 'Mail coaches on the veld', 81.

43 J.C. Scott, Domination and the arts of resistance: hidden transcripts), 18.

44 See S. Ouzman and J. Loubser, 'Art of the apocalypse'.

45 J.C. Scott, Domination..., 25.

46 See J Parkington and A. Manhire, 'The domestic context of fine line rock paintings in the Western Cape, South Africa' KRONOS 29, 2003, 30-46

47 As far as we are aware, the only archaeological inspection of a farm labourer's domicile was in the context of Gavin Anderson's research on Kagga Kamma at Jurie's Hut Site. This site backs onto sandstone boulders but there are no paintings. There are also no standing structures at this site, but a significant amount of broken glass, porcelain and refined earthenware pieces were recorded (A. Malan, unpublished report, November 1993, on file in the Department of Archaeology, UCT). It is significant that this material dates to the second half of the 19th century but not later than 1900. In light of the chronology for some of the colonial paintings suggested here, they must be contemporary with the domestic residues of farm labourers and consequently, some of the art can be tied to these contexts. Furthermore, the date of this material also falls within the 1860 and 1870 period when individuals were given title to many of these farms.

48 S.G. Dgm. No. 977/1862.

49 G. Anderson, 'Finger and finelines...' 51.

50 G. Anderson, 'Finelines and fingers...', 52.

51 See for example Nigel Penn, Rogues, rebels and runaways, 164, for a late eighteenth century narrative on droster gangs that captures the extremely marginal status of women.

52 S. Mguni, 'The evaluation of the superpositioning sequence of painted images to infer relative chronology', 43.

53 G. Anderson, 'Finelines and fingers...', 52.

54 See also R. Yates et. al., 'Colonial era paintings...'.

55 Ibid., 65.

56 S. Mguni, 'The evaluation of the superpositioning sequence of painted images to infer relative chronology', 31 ff.

57 R. Yates et. al., 'Colonial era paintings...', 66.