Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Kronos

On-line version ISSN 2309-9585

Print version ISSN 0259-0190

Kronos vol.30 n.1 Cape Town 2004

REVIEW ARTICLES

Wild Coast: shipwreck and captivity narratives from the Eastern Cape

Nigel Penn

University of Cape Town

The Caliban Shore: The Fate of the Grosvenor Castaways. By STEPHEN TAYLOR. London: Faber & Faber, 2004. xvi + 297 pp. ISBN 0-571-22330-3 and Guillaume Chenu De Chalezac, The 'French Boy': The Narrative of his Experiences as a Huguenot Refugee, as a Castaway among the Xhosa, his Rescue with the Stavenisse Survivors by the Centaurus, his Service at the Cape and Return to Europe, 1686-9. Edited by RANDOLPH VIGNE. Cape Town: Van Riebeeck Society, Second Series No. 22, 1993 for 1991. xxvi + 174 pp. ISBN 0630-17524-9.

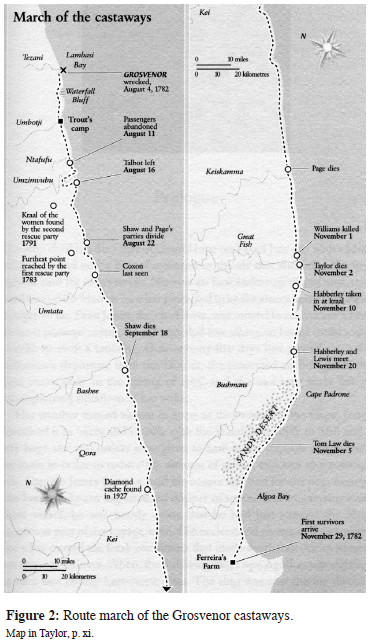

In the early hours of the morning of 4 August 1782 the East Indiaman Grosvenor ran aground on the Pondoland coast. Ninety-one seamen and thirty-four passengers (whose numbers included women and children) made it, through pounding surf, to the shore alive. One hundred and eighteen days later, after a 400 mile walk, six survivors reached the safety of Dutch settlement in the vicinity of Algoa Bay. Eventually, out of the 140 men, women and children who had sailed with the Grosvenor from Trincomalee, a mere thirteen ever reached home.

Shipwrecks were fairly common events on the south-east African coastline, thanks to navigational difficulties in calculating longitude, rough seas and foul weather. In 1755, for instance, the East Indiaman Dodington struck Bird Island in Algoa Bay with the loss of 247 lives, whilst in 1815 the Indiaman Arniston ran aground near Cape Agulhas drowning 366 of the 372 aboard. What made the Grosvenor disaster so significant, however, and arguably the most famous shipwreck to take place in southern African waters, was the knowledge that amongst the castaways there were white women who neither perished in the wreck nor returned to Britain. They were, instead, absorbed within the African societies of the Wild Coast, a fate which seemed, to English commentators at the time, worse than death. One of the first English newspapers to report on the wreck of the Grosvenor, The Morning Chronicle and London Advertiser, expressed its concerns thus:

The situation of the female passengers who were on board the Grosvenor Indiaman, must be the most dreadful that imagination can form, or humanity feel for. The ship was lost upon the coast of the Caffres, a country inhabited by the most barbarous and monstrous of the human species. By these Hottentots, they were dragged up into the interior parts of the country, for the purpose of the vilest brutish prostitution, and had the misfortune to see those friends, who were their fellow passengers, sacrificed in their defence.1

Three days later the same newspaper announced that 'a female correspondent, not being able to support the idea of the fate, which it is said, befell the unhappy ladies of the Grosvenor, would esteem it benevolent, if anyone in possession of authentic information would give it to the world through the channel of the Morning Chronicle'2

It was not only the British public which took the liveliest interest in the story of the Grosvenofs female castaways. The Dutch government at the Cape mounted a number of expeditions to rescue the English women, despite being at war with Britain at the time. The misfortunes of the Grosvenor women, real or imagined, also reached a wider European audience, thanks largely to the work of the French traveler, Francois le Vaillant, who wrote in his travels that: 'The idea of these miserable people haunted me everywhere; and I could not help reflecting on the melancholy situation of the poor women, condemned to drag out their existence amidst the torment and horror of despair.'3

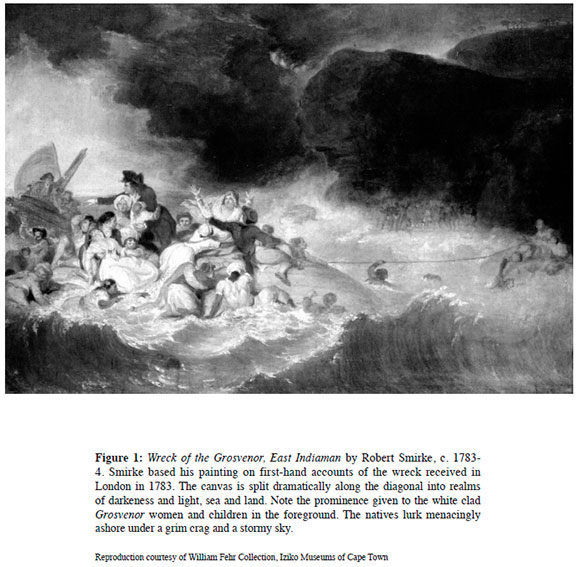

Le Vaillant's Travels, translated into English in 1790, preceded, by one year, the publication of George Carter's A Narrative of the Loss of the Grosvenor East Indiaman. This latter volume was an account based on the story of a survivor of the wreck, John Hynes. The two volumes were published together in 1802 by a Glasgow publisher4 - an indication that the British public's interest in what was, by then, a new British possession, was closely linked to the Grosvenor disaster. A spate of literary and artistic works inspired by the wreck followed le Vaillant's and Carter's narratives. Paintings by Robert Smirke (1784), George Morland (1790) and Carter himself (1791) envisaged the helpless survivors struggling through raging surf to the waiting blacks on the shore. Concerts and theatrical productions gave London audiences the chance to see dramatic representations of the plight of the Grosvenor castaways on stage. Literary works, ranging from Charles Dibdin's Hannah Hewit; or the Female Crusoe (1792), to Charles Dickens's essay The Long Voyage (1853) tapped into the Grosvenor story and it is not too much to state, as Ian Glenn does in an important article, that 'South African literature in English begins with the wreck of the Grosvenor.'5 In support of this contention he lists a number of nineteenth century novels about South Africa (including The Mission, by Captain Marryat) which 'used as a premise a ship-wreck, with or without female captivity' and discusses the extraordinary verse drama version of W.C. Scully, The Wreck of the Grosvenor (1886), which is replete with echoes of Shakespeare's The Tempest. The Grosvenor was causing literary ripples in the South African novel as late as the second half of the twentieth century where, in Sheila Fugard's The Castaways (1972), a white woman has to decide whether to make her home in Africa, amongst Africans, or return to Europe.

If the fate of the Grosvenor castaways was capable of exciting so much interest that it launched a national literature, it is somewhat surprising that the events in question have not received more modern scrutiny than they have. This is not to dismiss the heroic salvage efforts of Percival R. Kirby who, as a retired professor of music, devoted his autumnal years to publishing and editing journals and reports concerning the wreck, and who synthesized the labours of his research into his The True Story of the Grosvenor in I960.6 All who write about the Grosvenor are indebted to Kirby but, since his death in 1970, there has, until now, been very little scholarly, analytical or creative work on the subject by South African academics, writers or artists.

We may contrast this with the attention which a similar shipwreck has received from Australian and international observers. In 1836 the Stirling Castle was wrecked off the coast of Queensland and some of the crew, together with the captain's wife, Eliza Fraser, were castaway on the Great Sandy Island (later renamed Fraser Island) and held 'captive' by Aboriginal people. As was the case with the Grosvenor shipwreck, early reports of the disaster sensationalized the fate of a white woman at the mercy of 'savages'. Mrs. Fraser survived her ordeal and was returned to civilization where her story quickly attracted public attention in the Sydney Gazette in 1836, the London Times in 1837 and an illustrated book, The Shipwreck of the Stirling Castle, written by John Curtis, in 1838. The latter work, Rod Macneil has remarked, is one of the best examples we have of a narrative that allegorizes the colonial experience in the New World, and modern commentators have been both creative and energetic in interpreting Eliza Fraser's shipwreck in this light.7

The first substantial modern history of the event was Michael Alexander's Mrs Fraser on the Fatal Shore (1971). Alexander, an historian interested in captivity narratives and reports of cannibalism, admits that his appetite for the story was whetted by the Australian artist Sidney Nolan's 'Mrs Fraser' paintings, a series executed between 1947 and 1977. The Nolan paintings also inspired Patrick White's novel, A Fringe of Leaves (1976) and South African novelist André Brink's An Instant in the Wind (1976). Eliza Fraser's story is the source of Canadian Michael Ondaatje's long poem, The Man With Seven Toes (1969) and London playwrite Gabriel Josipovici's play Dreams of Mrs Fraser (first performed in 1972). A musical libretto, 'Eliza Fraser Sings', was composed by Barbara Blackman and Peter Sculthorpe in 1978 and the film Eliza Fraser (starring Susannah York) by Tim Burstall and David Williamson was first screened in 1976. All of these, and other, creative works inspired by Eliza Fraser are incisively discussed by Kay Schaffer in her In The Wake of First Contact: The Eliza Fraser Stories.8 A recent collection of essays, edited by McNiven, Russell and Schaffer, brings fresh perspectives to the event and its representations and seeks to allow the Aboriginal side of events to emerge in contributions ranging from studies on the archaeology of Fraser Island, to the oral traditions of the Butchulla clans on the Island, to the Aboriginal artist Fiona Foley, some of whose work has been inspired by the Eliza Fraser shipwreck.9

The range and richness of the above works on the wreck of the Stirling Castle and its female passenger should alert us to the fact that, comparatively speaking, the wreck of the Grosvenor has yet to yield its bounty to modern scholarship. Where Australian academics have scrutinized the Eliza Fraser stories for evidence of race, class and gender attitudes in the era of first contact, their South African colleagues have, very largely, ignored the wealth of material buried in the Grosvenor narratives. It is, perhaps, indicative of the priorities of our own society that twentieth century South Africans were largely interested in the material cargo of the Grosvenor and that even Kirby, as Taylor remarks, 'devoted a third of his book to the hunt for the wholly mythical Grosvenor treasure - with the aim of discrediting once and for all the syndicate fraudsters who preyed on investors for much of the twentieth century.'10 How far does Taylor's book go towards revitalizing intellectual interest in the Grosvenor?

The Caliban Shore is, above all, a very readable, well structured narrative of the wreck, its causes and its consequences. Taylor is a skillful writer who has enriched his account of events with sympathetic detail. He has done a great deal of research in the Oriental and India Office Collections at the British Library as well as in various South African library collections. He also walked the route which the Grosvenor survivors took down the Wild Coast and went in search of oral traditions about white castaways in Pondoland. The end result is a book that is a delight to read and which contributes greatly to our knowledge of the Grosvenor and its ill-starred crew. It is sensitive to the beauties, and perils, of the Pondoland coastline as well as to the culture of its inhabitants. Taylor never loses track of the fact that he is narrating a gripping tale of survival and he traces the adventures of his dwindling band of survivors, some of whom stand out as complex individual characters, with storytelling mastery.11

A most interesting and original feature of Taylor's account is the information he has gathered about the Grosvenor's connection to the world of India and the English East India Company. The Grosvenor was, after all, an East Indiaman and its crew and passengers were creatures of the Anglo-Indian trading world first and only secondly (in some cases, finally) castaways in Africa. It is ironic that the governor of Madras at this time, who spitefully and fatally delayed the departure of the Grosvenor so that the ship missed the fair sailing weather season, was later to be the Cape's first British governor - Lord Macartney. On board the Grosvenor was a lawyer, Charles Newman, who had been appointed by the English East India Company to investigate charges of corruption against its officials in Madras. Macartney refused to co-operate with Newman's investigations and the latter was returning to England to charge the Governor with non-co-operation. Luckily for Macartney, Newman never got home. The most high-ranking of the Grosvenor's passengers was William Hosea, ex-Resident at the Durbar of Bengal. Taylor reveals how this immensely wealthy man was leaving India in a great hurry. He paid the enormous sum of £2 000 (approximately £240 000 in today's value) for a passage on the Grosvenor for himself, his wife Mary and their eighteen month-old daughter Frances. There is good reason to suppose that, caught up in the treacherous politics and corrupt finances of the English East India Company, he was fleeing an impending scandal. Before departure he managed to convert some of his assets into £7 300 in rough diamonds and £1 700 in gold and silver, items which came with him on the Grosvenor.

Taylor's research has also revealed correspondence and papers relating to the anxious relatives and friends of those on the Grosvenor. Such people were to be found in both England and India. One such person was Richard Blechynden of Calcutta, brother of Lydia Logie and keeper of a seventy-three volume diary in which he recorded his distress about his sister's fate. Lydia was married to the Grosvenof s first mate, Alexander Logie. She is the Grosvenor's Eliza Fraser. Flame-haired, twenty-three years old and pregnant, it was she who was reported to have been forced to live 'with one of the black Princes by whom she had several children'. Blechynden was reminded of this horrific possibility by an article in the Calcutta Gazette nine years after the wreck, a fact which attests to the abiding interest in the Grosvenor and its women amongst the British in India.

Taylor saves his discussion of the fate of the Grosvenor women until last - a piece of titillation in keeping with the best traditions of contemporary sensationalist literature. But of equal, and more general interest, is the nature of the encounter between the castaway Europeans as a whole and the African inhabitants of the Wild Coast. Greg Denning has written most poetically about the beach as a meeting place of different cultures: 'for human beings beaches divide the world between here and there, us and them, good and bad, familiar and strange ... And things come across the beach partially, without their fuller meaning ...'12 For the storm-tossed survivors who staggered through the surf up a Pondoland beach near Lambasi Bay, the first inkling they had that they were in a very different world arrived with the first appearance of people. As survivor William Habberley recorded in his journal:

By this time [a] great number of the natives assembled together on the rocks. We hailed them as well as we were able in different languages, but could not make them understand us. Some, however, answered in their way by hallooing and shouting, but did not pay us the least assistance, but actively employed themselves in getting the iron from off the different things that had driven on shore.13

The unsympathetic indifference of the Pondo at the wreck to the plight of the castaways, contrasting with the avidity with which they appropriated metal objects, did not create a comforting impression. Ignoring this inconvenient evidence, however, the artist George Morland was inspired by the Grosvenor shipwreck to paint an oil entitled African Hospitality in 1790. It depicts the disheveled Hosea family being offered comfort by an assortment of 'noble savages', an extraordinary triumph of sentimental romanticism over reality. The painting's companion piece, The Slave Trade, shows white seamen brutalizing an African family. Though some of the Grosvenor survivors would later be recipients of African hospitality, 'the paradoxical representation of beastliness in Europeans and humanity among Africans,' whilst successful in London, was not an accurate reflection of events on the Wild Coast in 1782.14 In future encounters between the survivors and the indigenous inhabitants indifference was often replaced by hostile acquisitiveness as the Europeans were stripped of their clothes and whatever other objects they had managed to salvage. It would seem, from the behaviour of the Pondo, that this was not the first time that they had acquired metal from the windfall of a shipwreck. It would also seem that they had little inclination to show kindness to the whites cast up by the sea. Why?

The perception exists that the 'natural' response of the Nguni to shipwrecked Europeans was one of kindness. This perception is, to some extent, one derived from a selective reading of sources, such as the records of the Stavenisse survivors from the 1680s (see below). In reality, the reception offered to European castaways differed according to specific circumstances and the nature of the groups and individuals involved. But violence was never very far away. 'Violence is the ultimate social control, and in circumstances where cultural divisions are so great that no other controls are possible, the use of violence is like-ly.'15 The official report of the East India Company into the Grosvenor disaster, written up by Alexander Dalrymple, noted with perception that:

In great part their calamities seem to have arisen from want of management with the natives; I cannot therefore in my own mind doubt, that many lives may yet be preserved amongst the natives, as they treated the individuals that fell singly amongst them, rather with kindness than brutality, although it was natural that so large a body of Europeans would raise apprehensions; and fear always produces hostility.16

All moments of first contact between different societies are fraught with the possibility of dangerous misunderstandings or cultural misreadings. Even long familiarity with another's culture is no guarantee that a fatal mistake might not be made. But history, as well as culture, determines the ways in which people interact with each other. We must assume that the hundred years of history between the Stavenisse and the Grosvenor had done little to predispose the Nguni inhabitants of south-east Africa to spontaneous acts of kindness towards Europeans, but it had taught them that Europeans often had valuable metal objects about them. The Pondo at the wreck site could choose how to respond to the disaster that had befallen the Grosvenor castaways and they decided to exploit the survivors rather than assist them.

A group of 125 strangers was, perhaps, too large to expect hospitality and their vulnerability was too evident to deter predation. Their helplessness was largely due to the fact that no gunpowder had been salvaged from the wreck, thus rendering their firearms useless. Even so, a united display of determination to defend the group, backed up by cutlasses and improvised weapons, might have saved more of the survivors. Unfortunately the group's cohesion was compromised by weak leadership, internal dissension and an understandable reluctance to antagonize the surrounding Africans. In retrospect, of course, it was easy to say what should have been done. At the time, however, it was not that easy for the castaways to demonstrate British superiority to the locals and the bedraggled survivors of the wreck were faced with a number of difficult decisions.

Their commander, Captain Coxon, had already revealed his negligence by allowing the Grosvenor to be shipwrecked. On shore his authority steadily diminished as he failed to take measures to protect the group from the Pondo's pillaging. Shipboard discipline swiftly unraveled. The officer most likely to have commanded respect, chief mate Alexander Logie, had become severely ill on the voyage and was too weak to stand. There were a number of badly injured men, five children and seven women, one of whom, Lydia Logie, was in an advanced state of pregnancy. The only way the group, as a whole, could survive would be if the stronger helped the weaker. This did not happen. The options were to stay put and try to build a boat from the wreckage in order to sail to the Cape Colony. Alternatively, some of the fittest members could walk either northwards to Delagoa Bay to get assistance from the Portuguese or southwards to the Cape to fetch help from the Dutch. The rest should have constructed defensible positions and waited for rescue whilst bartering food from the Pondo or scavenging for mollusks and fish.

In the end, the worst possible decision was made - the entire group would march south. It was a shorter and, possibly, easier route to Delagoa Bay in the north, but the miscalculating Coxon did not know this, believing himself to be 250 instead of 400 miles from the nearest Dutch settlement.17 As the motley group struggled southwards hundreds of Pondo threw stones at them, threatened them with assegais or beat them with sticks, stripping them of everything they had. The group soon began to fragment, the stronger loath to become encumbered with the sick and the slow. A mere two days after starting out the first man was abandoned.

Shortly after this, on the 8th of August, the castaways had an interesting encounter with a runaway slave from the colony, a Javanese man called Trout (most likely 'Traut' in Dutch) who had made a new life for himself amongst the Pondo. Trout warned the group that they had no chance of reaching the colony because of the many hardships which lay ahead. He declined all entreaties to act as a guide and hurried off to plunder the wreck. He returned the next day - after the castaways had endured another attack by the Pondo - bizarrely clothed in one of Coxon's nightgowns. He once again declined to render any assistance and advised the survivors to offer no resistance to the Pondo. Soon after Trout's departure the group was once again roughly and thoroughly pillaged by a number of Pondo warriors leaving the Europeans with the impression that: 'The Malay was a rogue as he shewed the natives where [our] pockets were.' One need not be surprised that an escaped slave would rejoice in the reversal of customary colonial relationships and contribute to the Europeans' misfortune. This is made quite explicit in W.C. Scully's verse drama, The Wreck of the Grosvenor, where Trout is presented as a vengeful Caliban who berates the whites for their cruelty whilst asserting his own independence:

My name not matters, and my state is free.

Once, as a slave, I bore the chain and lash,

A human beast of burthen I was born,

A thinking chattel. Now I wander free

Amid these savages to me more kind

Than your curs'd race.18

Taylor does not seem to have been aware of Scully's drama, nor of Glenn's remarks on it. This is unfortunate, for not only is Scully's casting of Trout as a Caliban figure a characterization that resonates with the title and themes of Taylor's book, but the escaped slave (especially a slave in appropriated garments) is also a figure who, taken symbolically, acts as an intermediary between savagery and civilization. This is a point made by André Brink when he came to rework the Eliza Fraser story in an eastern Cape setting. In An Instant in the Wind a white woman is rescued from oblivion by an escaped slave who appears in her dead husband's clothing. The historical Eliza Fraser was rescued from her captivity by an Irish convict called John Graham who had spent six years living with the Aborigines of Wide Bay. Graham managed to convince them that Eliza was the ghost of his Aboriginal wife and that she should therefore be surrendered to his care. These literary and historical comparisons do not attract Taylor's eye and he never once alludes to, nor cites, any of the literature on the Eliza Fraser shipwreck. This is a pity for it is more than likely that Carter's Narrative of the Loss of the Grosvenor was a model for Curtis's Shipwreck of the Stirling Castle and the connections between the two shipwrecks and their associated literatures cry out for investigation.

Instead, Taylor keeps his attention resolutely focused on the ordeal of the Grosvenor survivors. A decisive moment of schism came on the 11th of August, just after the Ntafufu River had been forded. At moments of disaster it was not uncommon, on the peripheries of European expansion, for fractures to occur along class lines. At first glance the division of the Grosvenor survivors into two groups seems to confirm this. The slower moving group consisted of Captain Coxon, most of the passengers and people of rank, their servants and those of the ship's crew (like petty officers, the purser, and the surgeon) who had some loyalty to the chain of command. They numbered forty-seven in all. The rest - mostly seamen and the lascars (Indian Muslim sailors of whom there were initially twenty-five on the Grosvenor) - followed second mate William Shaw, a man of ability who had been excluded from the Captain's clique on board. The justification for the split was, according to Habberley, that: 'Every person was desirous of making the best of their way, saying it was of little use to stay and perish with those they could not give any assistance to. By this we were completely separated, and never after together again.'19 Shaw's group included most of the young and the strong, but it was joined by some elderly gentlemen, like the nabobs George Taylor and John Williams, who realized that they had a better chance of survival with Shaw than with Coxon.

The southwards march of Shaw's group is an epic tale, well told by Stephen Taylor, of survival for the few and extinction for the many. The major source of information on this group is the account of one of its survivors, William Habberley. Modern day hikers of the coast will know that progress depends on fording a succession of rivers and climbing one wooded hillside after another. One may add to this the uncertain reception - then as now - likely to be extended to wayfaring strangers by the local inhabitants. Shaw and his men never knew whether to expect a gift of food or violent death. As ill luck would have it, 'the Grosvenor had not only been wrecked along the most inhospitable stretch of the coast, but also at the leanest season of the year.'20 The Africans, as a whole, did not have food to spare. Shaw's group soon split into two, one section under Shaw going inland to see whether there might be more food there. The other section, a group of twenty-four under the leadership of Thomas Page, the ship's carpenter, decided to continue on down the coast. Shaw's section soon found there was even less food to be found in the interior and returned to the beach where shellfish, dead whale meat and snake flesh provided some sustenance. The group was steadily diminished by malnourishment, exhaustion, drownings and beatings - the latter administered at the hands of the Rharabe Xhosa, a society which had recently been at war with the colonists in what would retrospectively be called the First Frontier War. Shaw died of exhaustion on the 18th of September. By the time that Williams and Taylor were stoned and beaten to death on the 31st of October, near the mouth of the Fish River, only Habberley remained of the original twenty-one.

Page's party, which had stuck to the coastline, kept breaking up and reforming as groups of men decided to set their own pace rather than walk together. At their greatest moment of unity they numbered thirty-four, having been joined by ten men, non-swimmers who had been left behind at the fording of the Umtata River. Between the Bashee and the Fish River, however, cohesion vanished. As Kirby put it: 'The evidence of the survivors at this stage of the journey is so conflicting that one can hardly say more than that the whole coastline from the Bashee southwards must have been dotted with small parties of men, separated from each other by several miles, and making their way slowly in the direction of Algoa Bay while struggling desperately to find sufficient food to keep body and soul together.'21

One of the individuals amongst these struggling bands was a seven-year old Anglo-Indian boy named Tom Law, or 'Master Law'. Tom's father, also named Thomas, was a twenty-two year old gentleman of quality in Bengal who had taken an Indian woman as his lover. The unfortunate Master Law had been voyaging to school in England when the Grosvenor ran aground. Whilst the other shipwrecked children (there were six in all) had been left behind on the 11th of August, Tom clung to the man who had befriended him on the voyage, the steward, Henry Lillburne. Lillburne and his companions vowed to carry the boy with them, and they did so until the 5th of November when, in the sandy, desert dunes between Cape Padrone and Algoa Bay, Master Law expired. George Carter, who described the scene in his narrative and illustrated it in a sentimental painting, had most affecting material to deal with. Charles Dickens, himself a connoisseur of death-bed scenes involving children, was inspired by Carter's description to pay his own tribute to Lillburne in his essay 'The Long Voyage':

God knows all he does for the poor baby; how he cheerfully carries him in his arms when he himself is weak and ill; how he feeds him when he himself is gripped with want; how he folds his jacket round him, lays his little worn face with a woman's tenderness upon his sunburnt breast, soothes him in his sufferings, sings to him as he limps along, unmindful of his own parched and bleeding feet ... [He] shall be reunited in his immortal spirit - who can doubt it - with the child, where he and the poor carpenter shall be raised up with the words, 'inasmuch as ye have done it unto the least of these, ye have done it unto Me.'22

We may note that neither in Carter's painting nor Dickens's essay is young Tom portrayed as an Anglo-Indian. He becomes, instead, the 'sacred charge' (Dickens's words), whose innocent purity ennobles those who sacrifice themselves in his defence. British readers may have been critical of those men who left unprotected white women behind. There was, however, posthumous redemption for the selfless protector of Master Law in Dickens's prose. With the passing of Tom, Lillburne lost the will to live and the next day, on the 6th of November, three months since the wreck and after two days without any food or water, the steward fell down in the dunes and died.

The remainder of Lillburne's group, a mere three in number, were reduced to drinking their own urine and the contemplation of cannibalism. At this crucial moment they were joined by another small party of four stragglers who had found a spring of fresh water nearby. Thus fortified the men marched on until, on the 29th of November 1782, the surviving six encountered a servant of the farmer Christiaan Ferreira at Algoa Bay. One hundred and eighteen days after being wrecked and after having walked nearly 400 miles, the first of the Grosvenor castaways has reached safety.

Early in the new year a search party found three more survivors - one of whom was Habberley - enjoying hospitality at a Xhosa kraal near the mouth of the Bushman's River. It would seem that some Xhosa, at least, were willing to assist white men once they were obviously harmless and manageable. Habberley had earlier been expelled from another friendly Xhosa kraal when he inadvertently committed an unpardonable cultural transgression - he eased his troubled bowels in the cattle kraal. After this incident, however, he met with nothing but kindness from the Xhosa, an experience shared by the two other Grosvenor sailors at his host's kraal, the Venetian 'Bianco' Feancon and the Irishman Thomas Lewis. Soon after the Europeans were rescued eight lascars and two Indian women - the maids, or ayahs of Mary Hosea and Lydia Logie - were brought in. Nobody thought it worthwhile to record the stories of these, the last survivors of the Grosvenor, although Habberley did question the ayahs whilst recuperating in Swellendam. Unfortunately five of the lascars and one of the ayahs were to drown on their return voyage to India when, in a cruel twist of fate, the ship they were traveling in, the Nicobar, sank east of Cape Agulhas. Not one of the Europeans who made it home was over thirty. Only the youngest and fittest had survived.

What of the group who had been left behind at the Ntafufu River with Coxon? Our evidence on their fate is based on Habberley's account of his meeting with the ayahs at Swellendam after their rescue and with one of the lascars who had stayed on with Coxon for a while. According to Habberley, Coxon and most of the crew had abandoned the Hoseas and Logies, as well as Colonel and Mrs Sophia James 'and others who were unable to get forward on the same day as we had done.' This was not exemplary conduct. Those left behind included the Hosea's toddler Frances, as well as a three year old girl, Eleanor Dennis and two seven year olds, Robert Saunders and Mary Wilmot, who had been shipped off to school in England. What befell them all is uncertain. Alexander Logie was already on the point of death and his wife Lydia was heavily pregnant. The last descriptions of the Hoseas and Jameses are of people utterly dependent on their servants for their survival. It was not long, however, before their servants too abandoned them, the ayahs Betty and Hoakim eventually reaching the safety of Swellendam in the company of the lascars. None of Coxon's party made it back alive and their most likely fate was to have died of exhaustion - or to have been murdered - around the Umtata River.

As soon as news of the Grosvenor disaster reached the Cape, England and India, rumours began to circulate that there were some survivors, including women, who were being held as captives amongst the Africans. Lydia Logie, in particular, was named as the woman who had been abducted. The Dutch mounted a rescue party in December 1782 under the command of Heligert Muller.23 It was a massive undertaking, consisting of 109 Europeans and at least 170 Khoikhoi with 47 wagons and 216 horses. Coming as it did, soon after the First Frontier War, it would not be a distortion of the evidence to see this commando as a provocative demonstration of colonial strength - an armed reconnaissance into hostile territory. Schaffer makes the point that in Australia and America reports of missing white women frequently provided an excuse to mount rescue expeditions which were, in fact, little more than aggressive colonial excursions.24 The Muller commando was certainly not subtle. It did succeed in finding Habberley and his companions, but it turned back in February 1783, some fifty miles short of the wreck, convinced by local Africans that there were no more survivors.

Rumours and reports of castaways continued to reach officials at Cape Town. In October 1785 Lord Macartney, returning to Britain from Madras, called in at the Cape and discussed the Grosvenor affair with the commander of the Cape garrison, Robert Gordon. Gordon told Macartney that he believed that there was one Grosvenor lady still alive. In December Gordon was ordered on an expedition up the east coast and took the opportunity to question some Xhosa in the vicinity of the Fish River about the Grosvenor. He reported his findings to another visitor to the Cape in 1788 - Lieutenant William Bligh of H.M.S. Bounty, en route to the Pacific. Bligh recounted that: 'He said that in his travels to the Caffre country he had met with a native who described to him that there was a white woman among his countrymen, who had a child, and that she frequently embraced the child, and cried most violently.' Eighteen months later Bligh again called at the Cape, on his way back to England after the mutiny that made the Bounty famous. He again asked for news of the Grosvenor survivors and was told that a farmer had heard 'from some Kaffers that at a kraal or village in their country there were white women.'25

The farmer in question was, in fact, Jan Andries Holtshausen, ex-Heemraad of Swellendam, and a member of Muller's 1782-3 expedition. He and Muller had become convinced that they had turned back too soon in 1783 and that there were indeed Grosvenor survivors to be found. Apart from persistent rumours, there were material objects to lend support to this idea. Two silver buttons, engraved with the initials C.N., and identified as belonging to Charles Newman, had been obtained from some frontier Africans and passed firstly to the Cape governor, and secondly to the Governor-General of India. The upshot of this evidence was that Holtshausen and Muller organized, at their own expense, another search party. It is a measure of British interest in the quest that a copy of a journal kept by one of its members, Jacob van Reenen, was translated and published in England in 1792 by Edward Riou. The search party numbered a mere twelve men, motivated, so they said, 'solely in order, if possible, to discover whether any of the English women of the English ship, the Grosvenor ... were still alive, as we had heard, so that we might take these people out of their misery.' Despite these noble protestations the group spent a great deal of time hunting for ivory (one of their number, Lodewijk Prins, was killed by an enraged elephant) and probably reckoned that the expedition could be made profitable. In the end they were rewarded by the discovery of three white women in a kraal of 'bastaards' on the Umgazana River, just south of the Umgazi River, about fifty miles from the wreck site. The diarist of the expedition, Jacob van Reenen, reported that they found the so-called 'bastaards' to be:

A nation descended from whites, [and] also a few from yellow slaves and Bengalese. We also found there the three old women, who said they were sisters, wrecked there and saved; but [they] could not say of what nation they were, as they were too young at the time when the misfortune occurred to them. We offered to take the old women and their children back with us on our return, which, so it seemed to us, they were very willing for us to do.26

As it happened, the three white women never did return with the rescue expedition, despite being 'deeply moved, when we arrived, to see people of their race, and likewise when we left them.' The women insisted that they would only leave if they could take their entire progeny with them, 'which amounted to fully four hundred'. This the travellers 'prudently refused'.27

In later years, as the colony expanded and missionaries collected African oral traditions from the region, more became known about this extraordinary tribe of castaways. They were known as the amaTshomane. Their chief was called Sango and his wife, the matriarch of the clan, was named Gquma, meaning 'Roar of the Sea'. Her original name was Bess. She was probably English and had been cast up from a shipwreck, aged about seven, around 1750. She was one of the 'old women' encountered by the Holtshausen party, but as to who her 'sisters' were - apart from the fact that neither of them was Lydia Logie - little definite can be said. Taylor speculates that Lydia Logie may well have been taken in by the amaTshomane, but that she may have died before the arrival of the rescue mission over eight years later. There is also a good chance that Lydia's child (unborn at the time of the shipwreck) and the other children, including the girls Mary Wilmot and Eleanor Dennis, would have been absorbed by the amaTshomane. As acculturated adolescents they would have preferred staying with their new families - they might also have been hidden - rather than going off with a strange group of frontier Boers. The grounds for such speculations are various traditions, amongst descendants of the amaTshomane, that whites 'came out of the ship as if a whole nation'. That some were murdered, but that 'the female, as well as some female children were spared'. Ultimately, however, as Taylor is forced to conclude, 'the story of the Grosvenor women is beyond the test of history. It has acquired the quality of legend.'28

This chimerical quality is wholly in keeping with the genre of captivity narratives. As Jim Davidson explains, in a discussion of the White Woman of Gippsland (another Australian example of a shipwrecked white woman held 'captive' by Aborigines), white women - and to some extent white children - represented not only the finest and purest aspects of colonial civilization, they also represented its most vulnerable aspect: 'the Achilles' heel of colonialism':

hostages to fortune, to the success of the whole enterprise. The idealized woman . presented the sharpest contrast to the so-called savagery colonial menfolk were intent on subduing. So the elusive White Woman was always presented as a captive (never as somebody rescued), subject to a fate worse than death - doubly inflaming to men who were themselves often far from the comforts of wives and girlfriends.29

The determination of colonial men to rescue white women frequently took an aggressive turn. (At least fifty Aborigines were killed in the futile search for the White Woman of Gippsland). But this aggression should not mask the fact that, fundamentally, captivity narratives spoke to barely suppressed anxieties close to the heart of the imperial project.

This is the central argument of Linda Colley's fascinating book, Captives: Britain, Empire and the World, 1600-1850.30 Colley's is the only comparative work on captivity narratives which Taylor cites and he quotes with approval her pithy aphorism: 'Briton's could be slaves - and were.' Colley reminds us that, at its margins, the British Empire was far from being all-powerful. In reality, Britain was a small island with a small population and finite resources stretched to breaking point in the pursuit of global, maritime trading supremacy. Tens of thousands of men, women and children were taken captive by foreign societies and, as vulnerable individuals, they suddenly came to exemplify the limits of imperial power whilst, at the same time, personifying the very idea of 'Britishness'. The narratives produced by, or about, such victims and their ordeals were the best sellers of their day. Quite apart from the exotic adventures recounted within them, they raised issues close to the heart of the national, or imperial project. At what moment did the individual lose his or her cultural identity as a civilized, Christian, Briton and become a barbarized 'other'? At what point was the individual Briton lost to Britain? It is hardly coincidental that many of these captivity narratives, obsessed as they are with questions of identity, should today be considered the ur-texts of various colonial/national identities. We have already seen how central the Eliza Fraser story is to issues of Australian national identity. In North America too captivity narratives are regarded as the first American literary form and, as such, one of the foundation stones of the American character. Richard Slotkin declares them to be 'the starting point of an American mythology.'31

It is significant that American captivity narratives are also a genre dominated by women's experiences.32 Captivity narratives involving women were assured of an avid readership as they combined titillation with terror. Interest in the Grosvenor story was primarily fueled by speculation about the unspeakable degradations thought to have been inflicted upon British women - nubile, flame-haired Lydia in particular. Taylor states that what made the Grosvenor story remarkable is that for the first time gentlewomen were visible as victims of an unmistakably 'other' sexual predator. Given the great numbers of captives taken this may be a rather bold statement.33 But he is doubtless correct when he quotes an unnamed, unsourced writer as saying that the genre pandered to 'that White male desire at once to relish and deplore, vicariously share and publicly condemn, the rape of White female innocence.'

There was, however, more than a sexual frisson involved in the prospect of female innocence imperiled. Like Eliza Fraser, Lydia Logie came to represent, in the narratives constructed about her, the civilized virtues of the Empire itself. In the words of her bereaved brother, she was 'a delicate young female, tenderly brought up & of such exquisite sensibility that she might be said to be alive at every pore.' If she could be shown to have kept her civility, her morality, then Western civilization itself could be shown to have triumphed over savagery. Mrs Fraser did survive and accounts of her captivity were obliged to stress the ways in which she somehow managed to preserve her identity despite being beset by barbarism. Thus it was reported that she had kept her loins covered with vines (Patrick White's Fringe of Leaves) in whose foliage she also concealed - symbol of conjugal fidelity - her wedding ring. But Mrs Logie did not survive and it became important to imagine an early, unsullied grave for her or to construct posthumous evidence of her virtues. Brother Blechynden tried to console himself with the thought that 'where a woman is big with child she cannot have been forced', and that she could not have lived for long with the accumulated evils which surrounded her. Agonizingly he knew, however, that he could not be sure.

Once it became known that there were indeed descendants of white women living on the Wild Coast, it became necessary to invest them with superior qualities. The first Wesleyan missionaries in Butterworth, on hearing that 'there is now residing a Caffre with a numerous family who is descended from one of the unhappy sufferers of the Grosvenor East Indiaman wrecked about 50 years ago', made haste to accede to the man's request to send him a missionary, seeing this as confirmation of a divine purpose to propagate the gospel. The group in question was Gquma's kraal and, in the end, they proved, disappointingly, to be no more receptive to Christianity than any other Nguni. Kirby did, however, record a tradition that female descendants of Gquma were still being sought out as chiefly brides in 1881 on the grounds that they were 'regarded as wise and friendly to the white people'.

All of this attention to white women detracts from the fact that there were also some white men who survived the Grosvenor disaster and who were absorbed into Pondo society. After encountering Gquma's kraal in 1790 the rescue party continued on its way to the wreck site at Lambasi. Before reaching the bay, however, they were informed by the Africans that there was an Englishman from the Grosvenor who was still alive and living in the vicinity. The Dutch searchers found this individual, on the banks of the Umzimvubu River, on the 8th of November. For some reason, Taylor does not refer to this interesting encounter. The Englishman (whom Van Reenen calls 'the so-called Englishman') spoke Dutch and claimed to be a freeman who had sailed with the English from Mallaca. He offered to take the rescue party to the wreck and told them that all of the English were dead, some having been killed by the Africans and the others having starved. In the event, the so-called Englishman slipped away and did not take the group to the wreck. He did, however, divulge to Van Reenen's 'Bastaard-Hottentot' servant, Moses, that he knew Van Reenen's father in the Cape and that he himself had a wife and children in the colony. From this, Van Reenen concluded that the 'Englishman' was a runaway slave and from this, Graham Botha, who edited Van Reenen's journal in 1927 concluded, reasonably, that he must have been none other than Trout, the unhelpful Caliban who the Grosvenor castaways had met near the same spot in 1780.34 Why Taylor does not mention the reappearance of Trout is a mystery for the probable Malay and bogus Englishman is an important figure in the Grosvenor story, one who links the world of runaways to the world of castaways and draws attention to the porous nature of the colonial frontier. There is also the intriguing mention, in Habberley's journal, that Mrs. Logie's maid, Betty, 'had been living with a Malay who had left the Dutch, and all of the Lascars were found residing with such kind of people, who supported themselves on shell-fish, the natives not suffering them to reside near them.'35Taylor does not seem to have spotted this detail but it contains the answer as to why the Lascars had a much better survival rate that the Europeans. We can be sure that if anyone knew the fate of Mrs. Logie it would have been Trout and it is an interesting question as to why he was posing as an Englishman at all.

The Dutch rescuers rode on to the wreck site. Just before reaching it, on the 15th of November, Holtshausen had the misfortune to fall into an elephant trap and was wounded in the left hand by a sharpened stake. He died of the infection on the 23rd of November.36 His companions decided that there were no survivors to be found around the wreck, but had they been more diligent in their investigations they might have learnt that a soldier named John Bryan and a sailor named Joshua Glover had managed to find acceptance amongst the Pondo as a blacksmith and carpenter respectively. These two men had decided soon after being shipwrecked that they had a better chance of survival amongst the blacks than amongst their own countrymen (who, it seems, regarded Glover as a lunatic to begin with). They found ways to make themselves useful to their new protectors and ended their days amongst them as members of the society. Bryan assumed the name Umbethi, married a Pondo woman, and had two children with her. They were remembered in African oral traditions and Bryan's story was eventually related to the early Natal settler, Henry Fynn, by Bryan's son. These details should remind us of the obvious fact that far more white men than white women were cast up on the south-east coast of Africa and that their experiences are also of great interest.

This is the subject of Randolf Vigne's book, Guillaume Chenu De Chalezac, 'The French Boy' . The title is actually somewhat of a misnomer for although the centrepiece of the book consists of the annotated memoirs of Chenu, Vigne offers his readers a lot more. He has collected together and edited various contemporary narratives and journals pertaining to an assortment of ill-fated voyages that spewed up castaways on the south-east African coast in the 1680s. The voyages in question were those of the English ships Good Hope (ran aground in the Bay of Natal in May 1685), Bonaventure (lost in St. Lucia Bay in December 1686) and Bauden (from which Chenu was separated in February 1687) and the Dutch ship Stavenisse (wrecked about seventy-five kilometres south-west of the Bay of Natal in February 1686). Some of the survivors of these shipwrecks linked up with each other and constructed a sea-worthy vessel, the Centaurus, from the remains of the Good Hope. This vessel was sailed, successfully, to the Cape in March 1687 with twenty survivors on board. The Cape authorities quickly bought the Centaurus from its crew and dispatched it back up the coast to try to rescue those Europeans who had been left behind. The Centaurus managed to pick up a further sixteen of the stranded sailors, one of whom was Chenu, and returned to the Cape in February 1688. Eight months later a galliot, the Noord, was sent out by the Dutch to survey the coast to Delagoa Bay and to attempt to find more of the Stavenisse survivors. Chenu was amongst the crew. A handful of Europeans were rescued. A further trip by the Noord to the Bay of Natal in 1689-90 succeeded in finding more Stavenisse survivors, but the return voyage was disastrous. The galliot ran aground east of Cape St. Francis. Eighteen men reached the shore but only four survived the walk back to the Cape.

The significance of all of these voyages, as far as most historians of southern Africa are concerned, is that the testimonies of the survivors contained the first detailed descriptions of Nguni societies to reach the Dutch. Earlier reports, collected by the Portuguese from rescued Portuguese castaways, were untranslated and unavailable to the Dutch until their publication in 1729-31 as the Historia-Tragico Maritima. Grevenbroek, secretary to the Council of Policy at the Cape, recorded the survivors' testimonies and entered their observations about the Nguni into his Gentis Hottentotten Nuncupatae Descriptio, a work which lay unpublished until 1886 but which was certainly read before that date. The influential Caput Bonae Spei Hodierum (1719) by Peter Kolb borrows from Grevenbroek's findings and we may assume that Kolb was not the only one with access to this knowledge.37

The Good Hope and Stavenisse survivors - and Chenu as well - had been obliged to live for many months in close proximity with the Nguni before their rescue, a circumstance which gave them ample opportunity to observe their society. On the whole the impressions formed of the Nguni by the European sailors were very favourable. Many individuals were treated with great kindness by the Nguni and Chenu's host shed tears to see him leave. Those sailors who stayed together as a group, in order to build the Centaurus and to benefit from each other's company, were also well treated by the Africans. The contrast with the fate of the Grosvenor castaways is dramatic. It helped that the crew of the Good Hope were equipped with trading beads and copper, enabling them to purchase food and labour from the Africans. It also helped that they were well armed and less likely, therefore, to display 'want of management with the natives'. But it may also be, as Vigne suggests, that by the time of the Grosvenor shipwreck the attitude of blacks towards whites had become adversely influenced by the experience of colonial expansion and frontier fighting.

Whatever the reasons for these favourable impressions were, one should remember that non-survivors might have had a very different story. Of the sixty Stavenisse survivors who reached shore, only thirty-four returned to the Cape. Those Europeans who, like the Grosvenor castaways, attempted to walk to the Cape, suffered the most. Chenu tried twice, before being driven back to his Xhosa hosts by hardship. Other walkers were less fortunate, either dying at the hands of hostile Africans or perishing from hunger, exhaustion and exposure. It is worth noting that Chenu came ashore in a boat launched by the Bauden with seven companions. All save Chenu were beaten to death by the Xhosa in an orgy of violence caused by one of those fatal instances of cultural misreading. The Xhosa thought that the sailors wanted to take an earthenware pot. The sailors tried to indicate that they wanted to pay for the pot. By the time Chenu regained consciousness his friends were 'dead, and almost unrecognizable from the effects of the blows they had sustained'. He was probably only spared because he was a boy, fourteen years old and able to inspire compassion.

Chenu's boyish charm had come to his assistance before. He was a Huguenot refugee from France who had joined the Bauden at Madeira when the captain signed him on as cabin boy after being 'moved by his pleas'. The captain, John Cribb, soon treated him 'with special favour among the cabin boys'. This happy relationship came to an end when Captain Cribb was killed, bravely defending his ship against a pirate attack off the Cape Verde Islands. The Bauden made its way round the Cape under the command of Richard Salway who, being unsure of the ship's position, sent a boat ashore with Chanu and his companions to ascertain where they were. Contrary winds sprang up and the eight sailors never saw the Bauden again. After his friends' murder Chenu was taken by some friendlier Xhosa to some Dutch castaways and together they attempted to walk to the Cape. After only five days their group was attacked by a large number of Africans. One of the Dutch was killed, all were soundly beaten and robbed, and the rest returned to their hosts. Not long after this Chenu and eleven others tried to walk away again, this time following an inland route. Starvation killed half of them before the rest returned. Chenu resigned himself to living with a cousin of the chief, Sotope, who, he said, 'loved me like a son'. The French boy lived thus until his rescue a year later. He eventually returned to Europe and, at the age of eighteen, wrote an account of his adventures. It was published in German in 1748, in French in 1921 and now, for the first time, in English.

Chenu's narrative is a lively, fresh, Boy's Own adventure from start to finish. His observations on Xhosa customs and society will, however, be familiar to those students of South African history who have read versions of the Grevenbroek-Stavenisse accounts. Those who have not can now read the raw material in Vigne's book. Some of the texts he has assembled have been published before in collections such as Theal's Records of south-eastern Africa and Moodie's The Record. But Vigne has performed an invaluable service in collecting all of the sources between one set of covers. His scholarship is meticulous and exhaustive. He has consulted archives, libraries and collections in America, Germany, France, Britain, the Netherlands and South Africa, a labour requiring both linguistic skills and perseverance. The material is fascinating though it has to be said that it is very difficult to navigate through the contents of the book. The introduction does not really explain how the different sections of the book relate to each other, nor does it construct a chronological, narrative overview of the interconnecting events. Most of Vigne's prodigious knowledge is contained within the footnotes and it would have been better if some of it had been more spaciously displayed in bridging commentary between the various sections. One is forced to make connections by cross-referencing information in one footnote with details in another and, at times, it is like reading a randomly shuffled sheaf of card-index notes.

The stories contained in the sundry logbooks and journals deserve to rank amongst the greatest human adventures and contain some amazing feats of endurance.38 They remain, very largely, an untapped source by narrative historians and it is to be hoped that someone with story-telling skills might do to Vigne's source book what Taylor did to Kirby's on the Grosvenor. Even Taylor's treatment of the Grosvenor story, however, is not the last word on the subject and I remain of the opinion that there has been insufficient discussion concerning South African shipwreck stories. They are, after all, stories about the moment of first contact between Europeans and Africans in South Africa and are the place where myths and narratives about this event are first constructed. Why have South African scholars and writers lagged so far behind their Australian and American counterparts in addressing themselves to such stories?39

A clue to the answer might, perhaps, be provided by Andre Brink's interesting decision to retell the Eliza Fraser story as the basis for his novel, An Instant in the Wind, rather than the more obviously South African material of the wreck of the Grosvenor and Lydia Logie. Jim Davidson, who has interviewed Brink on this subject, suggests that Lydia might have been portrayed as a proto-1820 settler but 'the story would have lacked resonance, since the English have had difficulty indigenizing themselves in South Africa.'40 Brink's heroine could become one with Africa by returning to the thoroughly colonized Dutch Cape.41Eliza Fraser returned to a robust British community, poised to over-run the Australian continent. But the English woman, Lydia Logie, simply disappeared. There was no colonizing wave of English settlers into Pondoland. Nor was there a wave of Dutch settlement. Europeans in general had difficulty in indigenizing themselves here. Pondoland was only annexed to the Cape in 1894. This stretch of coastline chewed up and spat out more Europeans than it absorbed. Since it was never properly colonized it did not nurture a South African colonial identity in the same way as the American wilderness made 'Americans' or the Australian wilderness made 'Australians'. A tiny percentage of Europeans shipwrecked here between 1680 and 1782 survived. An even smaller number were assimilated into Nguni society. The Wild Coast remained wild.

Melancholy history

Shane Moran

University of KwaZulu-Natal

The Politics of Evil: Magic, State Power, and the Political Imagination in South Africa. By CLIFTON CRAIS. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002.

297pp. ISBN 0-521-53393-7.

The scholar cannot escape the obligation of criticism and evaluation. Some of his language must be direct.

In its various forms apartheid is a transfer of the responsibilities of the living world to a dream world of solved problems. It is the substitution of a wishful simplicity for a real complexity. (G.W. de Kiewiet, The Anatomy of South African Misery, 1956)

Clifton Crais's book takes up the story of subaltern resistance where his dramatic The Making of the Colonial Order: White Supremacy and Black Resistance in the Eastern Cape, 1770-1865 (1992) left off. That book reached the conclusion that the teachings of evangelical Christianity never fully conformed to the realities of colonial oppression, and the ruling classes never successfully dominated Africans in ideological terms. The Politics of Evil opens with the death of Hope, a British magistrate, in 1880 at the hands of rebellious Mpondomise. It ends with an account of the 1960 Pondoland Rebellion and the activities of Poqo. The two events are seen to mirror each other, forming a tradition of bitter and all-too-often doomed subaltern resistance that testifies to the failure of the attempt to colonize the mind of the oppressed and the failure to oust the colonizer.

'Part 1: Cultures of Conquest' tracks this attempt through the policies and practices of classification and tabulation associated with the ethnographic thrust of the settler state and the rationalities of its rule. 'Part 2: States of Emergency' moves from the millenarian prophecies of Black nationhood to the consolidation of apartheid and the simmering rebellion it both provoked and sought to stem. Crais argues that 'South Africa, and especially the Eastern Cape, offers an exemplary, if sad, history of the politics of evil in the colonial and postcolonial world' (5), a subaltern knowledge synchronized with millennial Christian beliefs that cannot be reduced to peasant discourses centred around the restoration of lost worlds: '"Subaltern" is used as a convenient shorthand, as long as we remember that the subaltern and their politics developed as part of an engagement with colonialism and, ultimately, with the problems of power and authority that transcended the colonial order itself' (11).

State formation in South Africa, at both local and national level, is seen as 'modernity gone mad' (9): 'Before the law the colonized was rendered fully cognizable, identified as subject to the state and entrapped in what Weber described as the "iron cage" of bureaucratic rationality' (86). From the 1920s onwards, South African state rationality became 'increasingly instrumental. That is, the logic of administrative practice became untethered from ethical consideration' (111). The very technical and seemingly neutral language of apartheid 'demonstrates precisely Weber's dread of the possible terrors of rationality' (9). In the colonies Weber's positive sense of the contribution of bureaucratic rationality that has destroyed structures of domination that had no rational character has no purchase. Events in the Eastern Cape and in South Africa as a whole, as well as colonialism per se, are fragments of the broader parable of the shadow of enlightenment; 'the colonial realization of the fears evinced by scholars such as Weber who warned of the dark side of rationality' (10).

I would like to pause to consider, in a preliminary fashion, three opening references to theoretical models - Weber, Adorno and Horkheimer, and Foucault - that inform the presuppositions of The Politics of Evil. Professional historians can better assess the detail of Crais's historical narrative. I do this because I want to suggest that the problems thrown up by Crais's conjunction of theorists point to some of the weaknesses of his book. The hastily collated theoretical armature is the support for the over-arching Manichean narrative of the Janus-face of modernity that is central to The Politics of Evil. It forms the coda to unravelling the often inchoate and disparate interactions and clashes that make up the trauma of South African colonialism and its wake. But, as we shall see, it leads to a failure to deliver on the promise of moving beyond the limitations of conventional historiography.

In The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism Weber argues that the material goods that should lie on the shoulders of the saint like a cloak that can be thrown aside at any moment have become an iron cage. Just as 'the spirit of religious asceticism - whether finally, who knows? - has escaped from the cage', so too has the victorious capitalism escaped the cage of 'the highest spiritual and cultural values [.] the individual generally abandons the attempt to justify it at all.'1 The iron cage is not simply bureaucratic rationality, which is itself a form of liberation, albeit a tragic one that has taken a recognisable form in the fifty years before World War I.2 Unless this dialectical interrelation of progress and retardation is kept in view, the process of rationalization is conflated with the evolution of history itself. As Walter Benjamin pointed out, the rationalization process is rather an ideal type, a fundamental form of societal structural dynamics, the appearance of which is neither limited to Western development nor synonymous with it.3

Without this refinement the problem of modernity simply becomes a tensionless but lethal farce of, at best, good (or neutral) intentions and horrific results. It hardly explains the relative economic strength of South Africa that indicates, in financial terms at least, the positive results of some portion of a murderous development planning. Crais appears to concede the need for a variegated analysis when he claims that in the three decades between 1920 and the introduction of apartheid in the 1950s, 'state rationality went from bureaucratic to instrumental, a pursuit of technical solutions based on empirical data in which decisions were largely unencumbered by ethical considerations' (103). Yet in The Politics of Evil the grand narrative of bureaucratic rationalism itself becomes another myth, sliding into a version of puritanical essentialism if reason is reduced to its instrumental form, blurring the central question of the ends to which reason is instrumentalised. As Crais says of the official colonial knowledges, the procedure is '"standardization and formalization", not complexity and nuance [.]' (83).

How credible is the hypothesis that colonial and apartheid bureaucrats took decisions untethered from ethical consideration? As a gesture of repugnance such an assertion is understandable but must be guarded against if it ironically undermines the nature of the problem. Weber is relevant here in so far as he was concerned with the vanishing of the ethical in the precise sense of the retreat of a transcendental or communal source for the legitimation of bureaucratic authority. The ethical aspect remains in the form of abstract duty and responsibility, and is attested in symbolic value and social status. Surely even the worst apartheid official did believe that his actions were ethical, that he was serving a - carefully delineated - community, stoically doing his duty, and perhaps ultimately serving some transcendental agenda. It would seem that the ideological mix of Christian nationalism within apartheid ideology secured this sense of manifest destiny.4 I would suggest that the Weberian idea of the decline of the religious can only be made to fit South Africa in a haphazard way that weakens its explanatory value.5Crais wants to shift the presence of religious belief onto the subaltern confrontation with an all-pervasive evil and the embracing of eschatologies that fall out of the purview of official surveillance. But this duality between a supposedly nominal official bureaucratic rationality and grass-roots messianism needs to be articulated in its mediations, institutions and practices rather than polemically asserted.

Crais privileges Adorno and Horkheimer's thesis in the Dialectic of Enlightenment that 'the European Holocaust was a consequence of, and not a deviation from, the Enlightenment' (9). We have noted that this is part of his critique of modernity with apartheid as the exemplary 'triumph of instrumental rationality in which the ends increasingly justified the means' (10). In this context one can imagine the attraction of the dialectic of enlightenment as a vision of reified society intent on total integration, leaving no sphere independent of society. The model of rationality compatible with the society based on exchange that it sustains would seem to have a natural affinity with the classificatory and taxonomic project of colonial and apartheid administration and legislation. Still, despite the pessimistic and condemnatory tone of the Dialectic of Enlightenment, the emphasis is on the dialectical nature of this development. The idea of incorporation certainly includes the acknowledgement of ferocious and sustained violence. But the major violence is to nature, or rather to a particular conception of nature that is instrumentalised. The originality of the concept of dialectic of enlightenment is that what passes before enlightenment - the archaic union with nature - is also a form of enlightenment, and the primal unity that is lost is always projected after the fact. The mourning or melancholia that is the dialectic of enlightenment, its schizophrenic progressivism and atavism, simply does not recognise itself. Hence the Dialectic of Enlightenment can be usefully reread as a diagnosis of the structural limits and pathologies of historical narrative.6

Crais invokes Foucault to underline the realisation of 'biopower' (9) as bureaucracy and surveillance, and appeals to the idea of 'the state's will to know' (103), despite its obvious homogenisation of the factions and levels of governance and coercion. However, Foucault distinguished his own analysis of the capillary conception of power as coextensive with the social from that of Weber and Adorno for whom 'it was a question of isolating the form of rationality presented as dominant, and endowed with the status of the one-and-only reason, in order to show that is only one possible form among others.'7 Furthermore, questions regarding the usefulness of Foucault in the colonial context cannot be ignored. The criticism is that when Foucault does introduce 'race' in the last chapter of the History of Sexuality, as one term in an array of terms to be calculated, he fails to specify the ways in which 'race' interacts, say, with the idea of formal equality.8 Without such a critical stance theory can become its own charismatic voice of authority, a supposedly transparent and supra-historical panopticon from which to calculate, codify and manipulate the textual remains that make up historical knowledge. It is difficult, for example, to see the immediate usefulness of the trajectory mapped out in Discipline and Punish of the evolution of disciplinary techniques in place of spectacular and unconcealed violence to a span of South African history in which state violence has remained doggedly shameless.

These misgivings aside, let us return to the pivotal event of The Politics of Evil, the opening of chapter one, 'The death of Hope':

He held Hope in his hand. 'Go on I will follow', the Mpondomise paramount chief told the British magistrate Hamilton Hope in the early days of October 1880. And 'where you die I will die'. As Mhlontlo spoke these words of unwavering loyalty the chief's wife lay ill not too far away, slowly perishing from a long disease. Mhlontlo looked up and out to the hills cascading down from the high mountains of Lesotho from whence the clouds and rains descended and turned the wintered landscape into green pastures and waving fields of sorghum. But the skies still refused to give up their rains. (35)

Crais interprets the death of Hamilton Hope as a ritual sacrifice intended to bring rain and heal the land. Unawares, Hope has entered a realm of symbolic meaning where the recognition of his power was seen as magic that could be appropriated and turned to the benefit of the land and its people. From this 'exemplary story of encounter, conquest and culture' (40), the central role of magic and its link with power in colonial resistance can be uncovered: 'Magic's ubiquitousness defeated its centralization' (51). Or more tentatively: 'The evidence powerfully suggests, though does not unequivocally demonstrate, that magic was an important feature of the colonial encounter, including the violence of conquest itself' (67); 'it is probable that the Mpondomise believed Hope had access to magic' (69). The connection between liberation struggle and theodicy is argued 'speculatively' (122).9

The introduction of apartheid is seen as representing 'a veritable recon-quest of the region, reproducing in a new key many of the basic features of conquest' (164). This sense of repetition and foreshadowing is the central device of The Politics of Evil's attempt to capture the experience of history from below. The attempt to extrapolate 'a sense in the records', evidence that 'is tantalizing if incomplete' (173), can lead to strained interpretations. See, for example, the stress on the purifying associations of fire in the case of the Makhulu Span's violent actions against stock thieves in the 1950s: 'Makhulu Span remained thoroughly committed to the use of fire, even when it was raining. We know that many people considered fire to be an important part of the arsenal combating witchcraft. It seems reasonable to assume .' (174). Fire, 'a common feature of violence throughout the eastern Cape' (190) is not to be interpreted 'as simply an effective way of dealing with one's enemies' because 'hut burnings invariably followed, instead of preceding, murders .' (254). On this 'evidence and other data' Crais argues that 'magic and witchcraft formed an important feature of the [Pondoland] revolt, if not for everyone then probably for most' (254).

Thus the events of the early 1950s illuminate the events of 1960. And beyond this, Hope's story is echoed in that of the magistrate at Lusikisiki, J. Fenwick, who 'descended into paranoia, obsession, and delusions of bureaucratic perfection, the insanity of social engineering run amok - a crazy avatar of authoritarianism, a twentieth-century Hamilton Hope' (199). 'Fenwick, the mad master of apartheid, was Hope's successor.' (228) History becomes an interminable repetition, a neurotic typology of recurrent symptoms. This is effectively mirrored in Crais's own didactic writing style, a style that appears at times to mimic what he says of a twentieth century archive marked by '[a]stounding duplication and textual monotony ...' (p.102).

The Politics of Evil ends with bleak reflections on a post-1994 South Africa in which '[t]he state of emergency in fact continues' (224), with spiralling crime, corruption and the scourge of HIV/AIDS. Part of this is the legacy of the subaltern politics of evil that sowed passions of hatred: 'It has nurtured the horrible violence of men who celebrate brutal murder and the burning of flesh' (222). Another rests at the level of political leadership that has 'sought access to state power, not its repudiation [.] to use reason to end the nightmare of oppression' (143-4): 'Thus, while beginning a new era of state formation in the country, the ANC government is, in a quite fundamental sense, renewing a tradition of rule begun in conquest and continuing in the twentieth century with segregation and apartheid' (227). The ANC receives yet another testimonium pauperitas, the apocalypse has been deferred yet the scorching breath of its annunciation animates the trauma of abortive violence. Crais's final words prophesy a new political history that will also be 'a history of people's seemingly infinite capacity for hatred as well as their hope that the future will be different' (230). Curiously no mention is made of the carefully ministered contemporary use of Christianity in South Africa.

More interesting is Crais's comment on Renan's dry observation that the idea of a nation requires a great deal of forgetting. He notes that scholars have had far fewer problems with the state, 'its analysis requiring neither irony, nor for that matter, any other literary device' (227). Crais's own use of literary devices - montage, moving from the historical vignette to elucidation and extrapolation - raises the question of whether the pivotal examples can bare the burden of serving as synecdochal emblems for his anti-epic of South African liberation. For me the Fenwick aperçu is too slight to sustain the resonance claimed, and the Makhula Span episode remains inconclusive. But the problem of the effectiveness of The Politics of Evil rests not so much with evidentiary protocols or the poetics of Crais's history or his narrative strategies that remain within the tropic conventions of the historiographical genre. Rather an all-pervasive defeatism circulates that results from the historian-as-moralist turning away from the bitter taste of compromise and accommodation. This ressentiment signals the temporal present of the text, its own encrypted history, and it permeates the flickering narrative chronology with a freighted and distorting pessimism that reads everything in advance. The guiding conceit of the jeremiad is that the exploration of subjugated knowledges reveals that the subaltern oppressed share this sense of betrayal and outrage with the historian.10

The use of the Hope and Mhlontlo incident, and its various contested interpretations, foregrounds the double sense of history as what happened and its representation. The crucial insight, this historical truth, is chilling for it tells us that there is only defeat in victory. In this Pyrrhic history of the oppressed the barbarities of the past are seen as prefiguration of a future that is now, and which retrospectively reveals the truth of its earlier prophecy validated in its present fulfilment: the political elite will sell out the dispossessed and collaborate with the oppressor. As in the heuristic mode of Biblical interpretation as figura, as prefiguration and fulfilment, the events of the past (historia) are seen to prefigure the events of the present. The danger, or the productivity, of this procedure for historical similitude lies in the temptation to metalepsis (the substitution of effect for cause). In my opinion the lens of exemplarity delivers a history flattened into stereotypical indices rotating around a hollow present. The use of detail and fragment as references to a fatalistic totality signals an aesthetic grounded in interminable substitution without limit.